Transportation (sediment) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sediment transport is the movement of solid particles ( sediment), typically due to a combination of gravity acting on the sediment, and/or the movement of the

Sediment transport is the movement of solid particles ( sediment), typically due to a combination of gravity acting on the sediment, and/or the movement of the

Sediment transport is applied to solve many environmental, geotechnical, and geological problems. Measuring or quantifying sediment transport or erosion is therefore important for coastal engineering. Several sediment erosion devices have been designed in order to quantify sediment erosion (e.g., Particle Erosion Simulator (PES)). One such device, also referred to as the BEAST (Benthic Environmental Assessment Sediment Tool) has been calibrated in order to quantify rates of sediment erosion.

Movement of sediment is important in providing habitat for fish and other organisms in rivers. Therefore, managers of highly regulated rivers, which are often sediment-starved due to dams, are often advised to stage short floods to refresh the bed material and rebuild bars. This is also important, for example, in the

Sediment transport is applied to solve many environmental, geotechnical, and geological problems. Measuring or quantifying sediment transport or erosion is therefore important for coastal engineering. Several sediment erosion devices have been designed in order to quantify sediment erosion (e.g., Particle Erosion Simulator (PES)). One such device, also referred to as the BEAST (Benthic Environmental Assessment Sediment Tool) has been calibrated in order to quantify rates of sediment erosion.

Movement of sediment is important in providing habitat for fish and other organisms in rivers. Therefore, managers of highly regulated rivers, which are often sediment-starved due to dams, are often advised to stage short floods to refresh the bed material and rebuild bars. This is also important, for example, in the

The Shields diagram empirically shows how the dimensionless critical shear stress (i.e. the dimensionless shear stress required for the initiation of motion) is a function of a particular form of the particle

The Shields diagram empirically shows how the dimensionless critical shear stress (i.e. the dimensionless shear stress required for the initiation of motion) is a function of a particular form of the particle

The settling velocity (also called the "fall velocity" or " terminal velocity") is a function of the particle

The settling velocity (also called the "fall velocity" or " terminal velocity") is a function of the particle

In 1935,

In 1935,

Formulas to calculate sediment transport rate exist for sediment moving in several different parts of the flow. These formulas are often segregated into bed load,

Formulas to calculate sediment transport rate exist for sediment moving in several different parts of the flow. These formulas are often segregated into bed load,

Sediment Transport

* Moore, A

Kent State. * Wilcock, P

January 26–28, 2004, University of California at Berkeley * Southard, J. B. (2007)

* Linwood, J,

Suspended Sediment Concentration and Discharge in a West London River.

{{Geologic Principles Fluid mechanics Sedimentology Environmental engineering Hydrology Physical geography Geological processes Transport phenomena

Sediment transport is the movement of solid particles ( sediment), typically due to a combination of gravity acting on the sediment, and/or the movement of the

Sediment transport is the movement of solid particles ( sediment), typically due to a combination of gravity acting on the sediment, and/or the movement of the fluid

In physics, a fluid is a liquid, gas, or other material that continuously deforms (''flows'') under an applied shear stress, or external force. They have zero shear modulus, or, in simpler terms, are substances which cannot resist any shear ...

in which the sediment is entrained. Sediment transport occurs in natural systems where the particles are clastic

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus,Essentials of Geology, 3rd Ed, Stephen Marshak, p. G-3 chunks, and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks ...

rocks ( sand, gravel

Gravel is a loose aggregation of rock fragments. Gravel occurs naturally throughout the world as a result of sedimentary and erosive geologic processes; it is also produced in large quantities commercially as crushed stone.

Gravel is classifi ...

, boulders, etc.), mud

A MUD (; originally multi-user dungeon, with later variants multi-user dimension and multi-user domain) is a Multiplayer video game, multiplayer Time-keeping systems in games#Real-time, real-time virtual world, usually Text-based game, text-bas ...

, or clay; the fluid is air, water, or ice; and the force of gravity acts to move the particles along the sloping surface on which they are resting. Sediment transport due to fluid motion occurs in rivers, oceans, lakes, sea

The sea, connected as the world ocean or simply the ocean, is the body of salty water that covers approximately 71% of the Earth's surface. The word sea is also used to denote second-order sections of the sea, such as the Mediterranean Sea, ...

s, and other bodies of water due to currents and tides. Transport is also caused by glaciers as they flow, and on terrestrial surfaces under the influence of wind. Sediment transport due only to gravity can occur on sloping surfaces in general, including hillslopes, scarp

Scarp may refer to:

Landforms and geology

* Cliff, a significant vertical, or near vertical, rock exposure

* Escarpment, a steep slope or long rock that occurs from erosion or faulting and separates two relatively level areas of differing elevatio ...

s, cliffs, and the continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

—continental slope boundary.

Sediment transport is important in the fields of sedimentary geology

''Sedimentary Geology'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal about sediments in a geological context published by Elsevier

Elsevier () is a Dutch academic publishing company specializing in scientific, technical, and medical content. Its p ...

, geomorphology

Geomorphology (from Ancient Greek: , ', "earth"; , ', "form"; and , ', "study") is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features created by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or n ...

, civil engineering, hydraulic engineering and environmental engineering (see applications, below). Knowledge of sediment transport is most often used to determine whether erosion or deposition will occur, the magnitude of this erosion or deposition, and the time and distance over which it will occur.

Mechanisms

Aeolian

''Aeolian'' or ''eolian'' (depending on the parsing of æ) is the term for sediment transport by wind. This process results in the formation of ripples andsand dunes

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, fl ...

. Typically, the size of the transported sediment is fine sand (<1 mm) and smaller, because air is a fluid with low density and viscosity, and can therefore not exert very much shear

Shear may refer to:

Textile production

*Animal shearing, the collection of wool from various species

**Sheep shearing

*The removal of nap during wool cloth production

Science and technology Engineering

*Shear strength (soil), the shear strength ...

on its bed.

Bedforms are generated by aeolian sediment transport in the terrestrial near-surface environment. Ripples and dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, f ...

s form as a natural self-organizing response to sediment transport.

Aeolian sediment transport is common on beaches and in the arid regions of the world, because it is in these environments that vegetation does not prevent the presence and motion of fields of sand.

Wind-blown very fine-grained dust is capable of entering the upper atmosphere and moving across the globe. Dust from the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

deposits on the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

and islands in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

, and dust from the Gobi desert

The Gobi Desert (Chinese: 戈壁 (沙漠), Mongolian: Говь (ᠭᠣᠪᠢ)) () is a large desert or brushland region in East Asia, and is the sixth largest desert in the world.

Geography

The Gobi measures from southwest to northeast an ...

has deposited on the western United States. This sediment is important to the soil budget and ecology of several islands.

Deposits of fine-grained wind-blown glacial sediment are called loess

Loess (, ; from german: Löss ) is a clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loess or similar deposits.

Loess is a periglacial or aeolian ...

.

Fluvial

In geology, physical geography, and sediment transport,fluvial

In geography and geology, fluvial processes are associated with rivers and streams and the deposits and landforms created by them. When the stream or rivers are associated with glaciers, ice sheets, or ice caps, the term glaciofluvial or fluviog ...

processes relate to flowing water in natural systems. This encompasses rivers, streams, periglacial flows, flash floods and glacial lake outburst floods. Sediment moved by water can be larger than sediment moved by air because water has both a higher density and viscosity. In typical rivers the largest carried sediment is of sand and gravel

Gravel is a loose aggregation of rock fragments. Gravel occurs naturally throughout the world as a result of sedimentary and erosive geologic processes; it is also produced in large quantities commercially as crushed stone.

Gravel is classifi ...

size, but larger floods can carry cobbles

Cobblestone is a natural building material based on cobble-sized stones, and is used for pavement roads, streets, and buildings.

Setts, also called Belgian blocks, are often casually referred to as "cobbles", although a sett is distinct fro ...

and even boulders.

Fluvial sediment transport can result in the formation of ripples and dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, f ...

s, in fractal

In mathematics, a fractal is a geometric shape containing detailed structure at arbitrarily small scales, usually having a fractal dimension strictly exceeding the topological dimension. Many fractals appear similar at various scales, as illu ...

-shaped patterns of erosion, in complex patterns of natural river systems, and in the development of floodplains.

Coastal

Coastal sediment transport takes place in near-shore environments due to the motions of waves and currents. At the mouths of rivers, coastal sediment and fluvial sediment transport processes mesh to create river deltas. Coastal sediment transport results in the formation of characteristic coastal landforms such as beaches, barrier islands, and capes.

Glacial

As glaciers move over their beds, they entrain and move material of all sizes. Glaciers can carry the largest sediment, and areas of glacial deposition often contain a large number ofglacial erratics

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

, many of which are several metres in diameter. Glaciers also pulverize rock into "glacial flour

Rock flour, or glacial flour, consists of fine-grained, silt-sized particles of rock, generated by mechanical grinding of bedrock by glacial erosion or by artificial grinding to a similar size. Because the material is very small, it becomes suspe ...

", which is so fine that it is often carried away by winds to create loess

Loess (, ; from german: Löss ) is a clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loess or similar deposits.

Loess is a periglacial or aeolian ...

deposits thousands of kilometres afield. Sediment entrained in glaciers often moves approximately along the glacial flowline

Linear scheduling method (LSM) is a graphical scheduling method focusing on continuous resource utilization in repetitive activities.

Application

LSM is used mainly in the construction industry to schedule resources in repetitive activities com ...

s, causing it to appear at the surface in the ablation zone.

Hillslope

In hillslope sediment transport, a variety of processes move regolith downslope. These include: *Soil creep

Downhill creep, also known as soil creep or commonly just creep, is a type of creep characterized by the slow, downward progression of rock and soil down a low grade slope; it can also refer to slow deformation of such materials as a result of p ...

* Tree throw

* Movement of soil by burrow

An Eastern chipmunk at the entrance of its burrow

A burrow is a hole or tunnel excavated into the ground by an animal to construct a space suitable for habitation or temporary refuge, or as a byproduct of locomotion. Burrows provide a form of sh ...

ing animals

* Slumping

Slumping is a technique in which items are made in a kiln by means of shaping glass over molds at high temperatures.

The slumping of a pyrometric cone is often used to measure temperature in a kiln.

Technique

Slumping glass is a highly techni ...

and landsliding

Landslides, also known as landslips, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, deep-seated slope failures, mudflows, and debris flows. Landslides occur in a variety of environments, ...

of the hillslope

These processes generally combine to give the hillslope a profile that looks like a solution to the diffusion equation

The diffusion equation is a parabolic partial differential equation. In physics, it describes the macroscopic behavior of many micro-particles in Brownian motion, resulting from the random movements and collisions of the particles (see Fick's la ...

, where the diffusivity is a parameter that relates to the ease of sediment transport on the particular hillslope. For this reason, the tops of hills generally have a parabolic concave-up profile, which grades into a convex-up profile around valleys.

As hillslopes steepen, however, they become more prone to episodic landslide

Landslides, also known as landslips, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, deep-seated grade (slope), slope failures, mudflows, and debris flows. Landslides occur in a variety of ...

s and other mass wasting events. Therefore, hillslope processes are better described by a nonlinear diffusion equation in which classic diffusion dominates for shallow slopes and erosion rates go to infinity as the hillslope reaches a critical angle of repose

The angle of repose, or critical angle of repose, of a granular material is the steepest angle of descent or dip relative to the horizontal plane to which a material can be piled without slumping. At this angle, the material on the slope fac ...

.

Debris flow

Large masses of material are moved in debris flows, hyperconcentrated mixtures of mud, clasts that range up to boulder-size, and water. Debris flows move asgranular flow

A granular material is a conglomeration of discrete solid, macroscopic particles characterized by a loss of energy whenever the particles interact (the most common example would be friction when grains collide). The constituents that compose gra ...

s down steep mountain valleys and washes. Because they transport sediment as a granular mixture, their transport mechanisms and capacities scale differently from those of fluvial systems.

Applications

Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon (, yuf-x-yav, Wi:kaʼi:la, , Southern Paiute language: Paxa’uipi, ) is a steep-sided canyon carved by the Colorado River in Arizona, United States. The Grand Canyon is long, up to wide and attains a depth of over a m ...

of the Colorado River, to rebuild shoreline habitats also used as campsites.

Sediment discharge into a reservoir formed by a dam forms a reservoir delta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), a letter of the Greek alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* D (NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta")

* Delta Air Lines, US

* Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19

Delta may also re ...

. This delta will fill the basin, and eventually, either the reservoir will need to be dredged or the dam will need to be removed. Knowledge of sediment transport can be used to properly plan to extend the life of a dam.

Geologists can use inverse solutions of transport relationships to understand flow depth, velocity, and direction, from sedimentary rocks and young deposits of alluvial materials.

Flow in culverts, over dams, and around bridge piers can cause erosion of the bed. This erosion can damage the environment and expose or unsettle the foundations of the structure. Therefore, good knowledge of the mechanics of sediment transport in a built environment are important for civil and hydraulic engineers.

When suspended sediment transport is increased due to human activities, causing environmental problems including the filling of channels, it is called siltation after the grain-size fraction dominating the process.

Initiation of motion

Stress balance

For a fluid to begin transporting sediment that is currently at rest on a surface, the boundary (or bed) shear stress exerted by the fluid must exceed the critical shear stress for the initiation of motion of grains at the bed. This basic criterion for the initiation of motion can be written as: :. This is typically represented by a comparison between a dimensionless shear stress and a dimensionless critical shear stress . The nondimensionalization is in order to compare the driving forces of particle motion (shear stress) to the resisting forces that would make it stationary (particle density and size). This dimensionless shear stress, , is called the Shields parameter and is defined as: :. And the new equation to solve becomes: :. The equations included here describe sediment transport forclastic

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus,Essentials of Geology, 3rd Ed, Stephen Marshak, p. G-3 chunks, and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks ...

, or granular sediment. They do not work for clays and muds because these types of floccular sediments do not fit the geometric simplifications in these equations, and also interact thorough electrostatic forces. The equations were also designed for fluvial

In geography and geology, fluvial processes are associated with rivers and streams and the deposits and landforms created by them. When the stream or rivers are associated with glaciers, ice sheets, or ice caps, the term glaciofluvial or fluviog ...

sediment transport of particles carried along in a liquid flow, such as that in a river, canal, or other open channel.

Only one size of particle is considered in this equation. However, river beds are often formed by a mixture of sediment of various sizes. In case of partial motion where only a part of the sediment mixture moves, the river bed becomes enriched in large gravel as the smaller sediments are washed away. The smaller sediments present under this layer of large gravel have a lower possibility of movement and total sediment transport decreases. This is called armouring effect. Other forms of armouring of sediment or decreasing rates of sediment erosion can be caused by carpets of microbial mats, under conditions of high organic loading.

Critical shear stress

The Shields diagram empirically shows how the dimensionless critical shear stress (i.e. the dimensionless shear stress required for the initiation of motion) is a function of a particular form of the particle

The Shields diagram empirically shows how the dimensionless critical shear stress (i.e. the dimensionless shear stress required for the initiation of motion) is a function of a particular form of the particle Reynolds number

In fluid mechanics, the Reynolds number () is a dimensionless quantity that helps predict fluid flow patterns in different situations by measuring the ratio between inertial and viscous forces. At low Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be domi ...

, or Reynolds number related to the particle. This allows the criterion for the initiation of motion to be rewritten in terms of a solution for a specific version of the particle Reynolds number, called .

:

This can then be solved by using the empirically derived Shields curve to find as a function of a specific form of the particle Reynolds number called the boundary Reynolds number. The mathematical solution of the equation was given by Dey

Dey (Arabic: داي), from the Turkish honorific title ''dayı'', literally meaning uncle, was the title given to the rulers of the Ottoman Algeria, Regency of Algiers (Algeria), Tripoli, Libya, Tripoli,Bertarelli (1929), p. 203. and Ottoman Tu ...

.

Particle Reynolds number

In general, a particle Reynolds number has the form: : Where is a characteristic particle velocity, is the grain diameter (a characteristic particle size), and is the kinematic viscosity, which is given by the dynamic viscosity, , divided by the fluid density, . : The specific particle Reynolds number of interest is called the boundary Reynolds number, and it is formed by replacing the velocity term in the particle Reynolds number by theshear velocity

Shear velocity, also called friction velocity, is a form by which a shear stress may be re-written in units of velocity. It is useful as a method in fluid mechanics to compare true velocities, such as the velocity of a flow in a stream, to a veloci ...

, , which is a way of rewriting shear stress in terms of velocity.

:

where is the bed shear stress (described below), and is the von Kármán constant, where

:.

The particle Reynolds number is therefore given by:

:

Bed shear stress

The boundary Reynolds number can be used with the Shields diagram to empirically solve the equation :, which solves the right-hand side of the equation :. In order to solve the left-hand side, expanded as :, the bed shear stress needs to be found, . There are several ways to solve for the bed shear stress. The simplest approach is to assume the flow is steady and uniform, using the reach-averaged depth and slope. because it is difficult to measure shear stress ''in situ'', this method is also one of the most-commonly used. The method is known as the depth-slope product.Depth-slope product

For a river undergoing approximately steady, uniform equilibrium flow, of approximately constant depth ''h'' and slope angle θ over the reach of interest, and whose width is much greater than its depth, the bed shear stress is given by some momentum considerations stating that the gravity force component in the flow direction equals exactly the friction force. For a wide channel, it yields: : For shallow slope angles, which are found in almost all natural lowland streams, thesmall-angle formula

The small-angle approximations can be used to approximate the values of the main trigonometric functions, provided that the angle in question is small and is measured in radians:

:

\begin

\sin \theta &\approx \theta \\

\cos \theta &\approx 1 - \ ...

shows that is approximately equal to , which is given by , the slope. Rewritten with this:

:

Shear velocity, velocity, and friction factor

For the steady case, by extrapolating the depth-slope product and the equation for shear velocity: : :, The depth-slope product can be rewritten as: :. is related to the mean flow velocity, , through the generalized Darcy-Weisbach friction factor, , which is equal to the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor divided by 8 (for mathematical convenience). Inserting this friction factor, :.Unsteady flow

For all flows that cannot be simplified as a single-slope infinite channel (as in the depth-slope product, above), the bed shear stress can be locally found by applying theSaint-Venant equations

The shallow-water equations (SWE) are a set of hyperbolic partial differential equations (or parabolic if viscous shear is considered) that describe the flow below a pressure surface in a fluid (sometimes, but not necessarily, a free surface). T ...

for continuity, which consider accelerations within the flow.

Example

Set-up

The criterion for the initiation of motion, established earlier, states that :. In this equation, :, and therefore :. : is a function of boundary Reynolds number, a specific type of particle Reynolds number. :. For a particular particle Reynolds number, will be an empirical constant given by the Shields Curve or by another set of empirical data (depending on whether or not the grain size is uniform). Therefore, the final equation to solve is: :.Solution

Some assumptions allow the solution of the above equation. The first assumption is that a good approximation of reach-averaged shear stress is given by the depth-slope product. The equation then can be rewritten as: :. Moving and re-combining the terms produces: : where R is thesubmerged specific gravity

Submerged specific gravity is a dimensionless measure of an object's buoyancy when immersed in a fluid. It can be expressed in terms of the equation

:\text = \frac

where \text stands for "submerged specific gravity", \rho_o is the density of the ...

of the sediment.

The second assumption is that the particle Reynolds number is high. This typically applies to particles of gravel-size or larger in a stream, and means the critical shear stress is constant. The Shields curve shows that for a bed with a uniform grain size,

:.

Later researchers have shown this value is closer to

:

for more uniformly sorted beds. Therefore the replacement

:

is used to insert both values at the end.

The equation now reads:

:

This final expression shows the product of the channel depth and slope is equal to the Shield's criterion times the submerged specific gravity of the particles times the particle diameter.

For a typical situation, such as quartz-rich sediment in water , the submerged specific gravity is equal to 1.65.

:

Plugging this into the equation above,

:.

For the Shield's criterion of . 0.06 * 1.65 = 0.099, which is well within standard margins of error of 0.1. Therefore, for a uniform bed,

:.

For these situations, the product of the depth and slope of the flow should be 10% of the diameter of the median grain diameter.

The mixed-grain-size bed value is , which is supported by more recent research as being more broadly applicable because most natural streams have mixed grain sizes. If this value is used, and D is changed to D_50 ("50" for the 50th percentile, or the median grain size, as an appropriate value for a mixed-grain-size bed), the equation becomes:

:

Which means that the depth times the slope should be about 5% of the median grain diameter in the case of a mixed-grain-size bed.

Modes of entrainment

The sediments entrained in a flow can be transported along the bed as bed load in the form of sliding and rolling grains, or in suspension assuspended load

The suspended load of a flow of fluid, such as a river, is the portion of its sediment uplifted by the fluid's flow in the process of sediment transportation. It is kept suspended by the fluid's turbulence. The suspended load generally consists of ...

advected by the main flow. Some sediment materials may also come from the upstream reaches and be carried downstream in the form of wash load.

Rouse number

The location in the flow in which a particle is entrained is determined by the Rouse number, which is determined by the density ''ρ''s and diameter ''d'' of the sediment particle, and the density ''ρ'' and kinematic viscosity ''ν'' of the fluid, determine in which part of the flow the sediment particle will be carried. : Here, the Rouse number is given by ''P''. The term in the numerator is the (downwards) sediment the sedimentsettling velocity

Terminal velocity is the maximum velocity (speed) attainable by an object as it falls through a fluid (air is the most common example). It occurs when the sum of the drag force (''Fd'') and the buoyancy is equal to the downward force of gravit ...

''w''s, which is discussed below. The upwards velocity on the grain is given as a product of the von Kármán constant, ''κ'' = 0.4, and the shear velocity

Shear velocity, also called friction velocity, is a form by which a shear stress may be re-written in units of velocity. It is useful as a method in fluid mechanics to compare true velocities, such as the velocity of a flow in a stream, to a veloci ...

, ''u''∗.

The following table gives the approximate required Rouse numbers for transport as bed load, suspended load

The suspended load of a flow of fluid, such as a river, is the portion of its sediment uplifted by the fluid's flow in the process of sediment transportation. It is kept suspended by the fluid's turbulence. The suspended load generally consists of ...

, and wash load.

Settling velocity

Reynolds number

In fluid mechanics, the Reynolds number () is a dimensionless quantity that helps predict fluid flow patterns in different situations by measuring the ratio between inertial and viscous forces. At low Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be domi ...

. Generally, for small particles (laminar approximation), it can be calculated with Stokes' Law

In 1851, George Gabriel Stokes derived an expression, now known as Stokes' law, for the frictional force – also called drag force – exerted on spherical objects with very small Reynolds numbers in a viscous fluid. Stokes' law is derived by s ...

. For larger particles (turbulent particle Reynolds numbers), fall velocity is calculated with the turbulent drag

Drag or The Drag may refer to:

Places

* Drag, Norway, a village in Tysfjord municipality, Nordland, Norway

* ''Drág'', the Hungarian name for Dragu Commune in Sălaj County, Romania

* Drag (Austin, Texas), the portion of Guadalupe Street adj ...

law. Dietrich

Dietrich () is an ancient German name meaning "Ruler of the People.” Also "keeper of the keys" or a "lockpick" either the tool or the profession.

Given name

* Dietrich, Count of Oldenburg (c. 1398 – 1440)

* Thierry of Alsace (german: Dietr ...

(1982) compiled a large amount of published data to which he empirically fit settling velocity curves. Ferguson and Church (2006) analytically combined the expressions for Stokes flow and a turbulent drag law into a single equation that works for all sizes of sediment, and successfully tested it against the data of Dietrich. Their equation is

:.

In this equation ''ws'' is the sediment settling velocity, ''g'' is acceleration due to gravity, and ''D'' is mean sediment diameter. is the kinematic viscosity of water, which is approximately 1.0 x 10−6 m2/s for water at 20 °C.

and are constants related to the shape and smoothness of the grains.

The expression for fall velocity can be simplified so that it can be solved only in terms of ''D''. We use the sieve diameters for natural grains, , and values given above for and . From these parameters, the fall velocity is given by the expression:

:

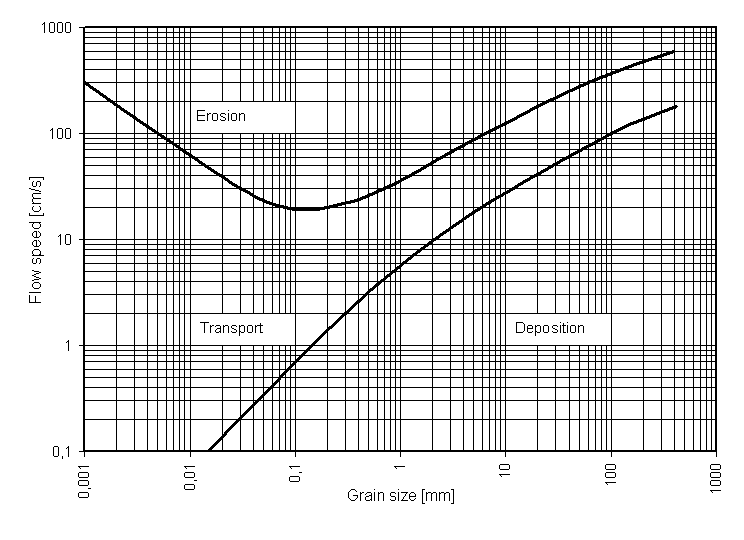

Hjulström-Sundborg Diagram

Filip Hjulström

Henning Filip Hjulström (6 October 1902 – 26 March 1982) was a Swedish geographer. Hjulström was professor of geography at Uppsala University from 1944, and in 1949, when the subject of geography was split, he became professor of Physical ...

created the Hjulström curve, a graph which shows the relationship between the size of sediment and the velocity required to erode (lift it), transport it, or deposit it. The graph is logarithmic Logarithmic can refer to:

* Logarithm, a transcendental function in mathematics

* Logarithmic scale, the use of the logarithmic function to describe measurements

* Logarithmic spiral,

* Logarithmic growth

* Logarithmic distribution, a discrete pr ...

.

Åke Sundborg later modified the Hjulström curve to show separate curves for the movement threshold corresponding to several water depths, as is necessary if the flow velocity rather than the boundary shear stress (as in the Shields diagram) is used for the flow strength.

This curve has no more than a historical value nowadays, although its simplicity is still attractive. Among the drawbacks of this curve are that it does not take the water depth into account and more importantly, that it does not show that sedimentation is caused by flow velocity ''deceleration'' and erosion is caused by flow ''acceleration''. The dimensionless Shields diagram is now unanimously accepted for initiation of sediment motion in rivers.

Transport rate

Formulas to calculate sediment transport rate exist for sediment moving in several different parts of the flow. These formulas are often segregated into bed load,

Formulas to calculate sediment transport rate exist for sediment moving in several different parts of the flow. These formulas are often segregated into bed load, suspended load

The suspended load of a flow of fluid, such as a river, is the portion of its sediment uplifted by the fluid's flow in the process of sediment transportation. It is kept suspended by the fluid's turbulence. The suspended load generally consists of ...

, and wash load. They may sometimes also be segregated into bed material load Three components that are included in the load of a river system are the following: dissolved load, wash load and bed material load. The bed material load is the portion of the sediment that is transported by a stream that contains material derived ...

and wash load.

Bed Load

Bed load moves by rolling, sliding, and hopping (or saltating) over the bed, and moves at a small fraction of the fluid flow velocity. Bed load is generally thought to constitute 5-10% of the total sediment load in a stream, making it less important in terms of mass balance. However, thebed material load Three components that are included in the load of a river system are the following: dissolved load, wash load and bed material load. The bed material load is the portion of the sediment that is transported by a stream that contains material derived ...

(the bed load plus the portion of the suspended load which comprises material derived from the bed) is often dominated by bed load, especially in gravel-bed rivers. This bed material load is the only part of the sediment load that actively interacts with the bed. As the bed load is an important component of that, it plays a major role in controlling the morphology of the channel.

Bed load transport rates are usually expressed as being related to excess dimensionless shear stress raised to some power. Excess dimensionless shear stress is a nondimensional measure of bed shear stress about the threshold for motion.

:,

Bed load transport rates may also be given by a ratio of bed shear stress to critical shear stress, which is equivalent in both the dimensional and nondimensional cases. This ratio is called the "transport stage" and is an important in that it shows bed shear stress as a multiple of the value of the criterion for the initiation of motion.

:

When used for sediment transport formulae, this ratio is typically raised to a power.

The majority of the published relations for bedload transport are given in dry sediment weight per unit channel width, ("breadth

Length is a measure of distance. In the International System of Quantities, length is a quantity with dimension distance. In most systems of measurement a base unit for length is chosen, from which all other units are derived. In the Interna ...

"):

:.

Due to the difficulty of estimating bed load transport rates, these equations are typically only suitable for the situations for which they were designed.

Notable bed load transport formulae

=Meyer-Peter Müller and derivatives

= The transport formula of Meyer-Peter and Müller, originally developed in 1948, was designed for well- sortedfine

Fine may refer to:

Characters

* Sylvia Fine (''The Nanny''), Fran's mother on ''The Nanny''

* Officer Fine, a character in ''Tales from the Crypt'', played by Vincent Spano

Legal terms

* Fine (penalty), money to be paid as punishment for an offe ...

gravel

Gravel is a loose aggregation of rock fragments. Gravel occurs naturally throughout the world as a result of sedimentary and erosive geologic processes; it is also produced in large quantities commercially as crushed stone.

Gravel is classifi ...

at a transport stage of about 8. The formula uses the above nondimensionalization for shear stress,

:,

and Hans Einstein's nondimensionalization for sediment volumetric discharge per unit width

:.

Their formula reads:

:.

Their experimentally determined value for is 0.047, and is the third commonly used value for this (in addition to Parker's 0.03 and Shields' 0.06).

Because of its broad use, some revisions to the formula have taken place over the years that show that the coefficient on the left ("8" above) is a function of the transport stage:

:

:

The variations in the coefficient were later generalized as a function of dimensionless shear stress:

:

=Wilcock and Crowe

= In 2003,Peter Wilcock

Peter Howard Wilcock (born 18 November 1945) is an English professional golfer. He won the Italian BP Open in 1972 and represented England in the 1973 World Cup. Wilcock is remembered for scoring a hole-in-one on two successive days in the 1974 ...

and Joanna Crowe (now Joanna Curran) published a sediment transport formula that works with multiple grain sizes across the sand and gravel range. Their formula works with surface grain size distributions, as opposed to older models which use subsurface grain size distributions (and thereby implicitly infer a surface grain sorting

Sorting refers to ordering data in an increasing or decreasing manner according to some linear relationship among the data items.

# ordering: arranging items in a sequence ordered by some criterion;

# categorizing: grouping items with similar pro ...

).

Their expression is more complicated than the basic sediment transport rules (such as that of Meyer-Peter and Müller) because it takes into account multiple grain sizes: this requires consideration of reference shear stresses for each grain size, the fraction of the total sediment supply that falls into each grain size class, and a "hiding function".

The "hiding function" takes into account the fact that, while small grains are inherently more mobile than large grains, on a mixed-grain-size bed, they may be trapped in deep pockets between large grains. Likewise, a large grain on a bed of small particles will be stuck in a much smaller pocket than if it were on a bed of grains of the same size. In gravel-bed rivers, this can cause "equal mobility", in which small grains can move just as easily as large ones. As sand is added to the system, it moves away from the "equal mobility" portion of the hiding function to one in which grain size again matters.

Their model is based on the transport stage, or ratio of bed shear stress to critical shear stress for the initiation of grain motion. Because their formula works with several grain sizes simultaneously, they define the critical shear stress for each grain size class, , to be equal to a "reference shear stress", .

They express their equations in terms of a dimensionless transport parameter, (with the "" indicating nondimensionality and the "" indicating that it is a function of grain size):

:

is the volumetric bed load transport rate of size class per unit channel width . is the proportion of size class that is present on the bed.

They came up with two equations, depending on the transport stage, . For :

:

and for :

:.

This equation asymptotically reaches a constant value of as becomes large.

=Wilcock and Kenworthy

= In 2002,Peter Wilcock

Peter Howard Wilcock (born 18 November 1945) is an English professional golfer. He won the Italian BP Open in 1972 and represented England in the 1973 World Cup. Wilcock is remembered for scoring a hole-in-one on two successive days in the 1974 ...

and Kenworthy T.A. , following Peter Wilcock (1998), published a sediment bed-load transport formula that works with only two sediments fractions, i.e. sand and gravel fractions. Peter Wilcock and Kenworthy T.A. in their article recognized that a mixed-sized sediment bed-load transport model using only two fractions offers practical advantages in terms of both computational and conceptual modeling by taking into account the nonlinear effects of sand presence in gravel beds on bed-load transport rate of both fractions. In fact, in the two-fraction bed load formula appears a new ingredient with respect to that of Meyer-Peter and Müller that is the proportion of fraction on the bed surface where the subscript represents either the sand (s) or gravel (g) fraction. The proportion , as a function of sand content , physically represents the relative influence of the mechanisms controlling sand and gravel transport, associated with the change from a clast-supported to matrix-supported gravel bed. Moreover, since spans between 0 and 1, phenomena that vary with include the relative size effects producing ‘‘hiding’’ of fine grains and ‘‘exposure’’ of coarse grains.

The ‘‘hiding’’ effect takes into account the fact that, while small grains are inherently more mobile than large grains, on a mixed-grain-size bed, they may be trapped in deep pockets between large grains. Likewise, a large grain on a bed of small particles will be stuck in a much smaller pocket than if it were on a bed of grains of the same size, which the Meyer-Peter and Müller formula refers to. In gravel-bed rivers, this can cause ‘‘equal mobility", in which small grains can move just as easily as large ones. As sand is added to the system, it moves away from the ‘‘equal mobility’’ portion of the hiding function to one in which grain size again matters.

Their model is based on the transport stage,''i.e.'' , or ratio of bed shear stress to critical shear stress for the initiation of grain motion. Because their formula works with only two fractions simultaneously, they define the critical shear stress for each of the two grain size classes, , where represents either the sand (s) or gravel (g) fraction . The critical shear stress that represents the incipient motion for each of the two fractions is consistent with established values in the limit of pure sand and gravel beds and shows a sharp change with increasing sand content over the transition from a clast- to matrix-supported bed.

They express their equations in terms of a dimensionless transport parameter, (with the "" indicating nondimensionality and the ‘‘’’ indicating that it is a function of grain size):

:

is the volumetric bed load transport rate of size class per unit channel width . is the proportion of size class that is present on the bed.

They came up with two equations, depending on the transport stage, . For :

:

and for :

:.

This equation asymptotically reaches a constant value of as becomes large and the symbols have the following values:

:

:

In order to apply the above formulation, it is necessary to specify the characteristic grain sizes for the sand portion and for the gravel portion of the surface layer, the fractions and of sand and gravel, respectively in the surface layer, the submerged specific gravity of the sediment R and shear velocity associated with skin friction .

= Kuhnle ''et al.''

= For the case in which sand fraction is transported by the current over and through an immobile gravel bed, Kuhnle ''et al.''(2013), following the theoretical analysis done by Pellachini (2011), provides a new relationship for the bed load transport of the sand fraction when gravel particles remain at rest. It is worth mentioning that Kuhnle ''et al.'' (2013) applied the Wilcock and Kenworthy (2002) formula to their experimental data and found out that predicted bed load rates of sand fraction were about 10 times greater than measured and approached 1 as the sand elevation became near the top of the gravel layer. They, also, hypothesized that the mismatch between predicted and measured sand bed load rates is due to the fact that the bed shear stress used for the Wilcock and Kenworthy (2002) formula was larger than that available for transport within the gravel bed because of the sheltering effect of the gravel particles. To overcome this mismatch, following Pellachini (2011), they assumed that the variability of the bed shear stress available for the sand to be transported by the current would be some function of the so-called "Roughness Geometry Function" (RGF), which represents the gravel bed elevations distribution. Therefore, the sand bed load formula follows as: : where : the subscript refers to the sand fraction, s represents the ratio where is the sand fraction density, is the RGF as a function of the sand level within the gravel bed, is the bed shear stress available for sand transport and is the critical shear stress for incipient motion of the sand fraction, which was calculated graphically using the updated Shields-type relation of Miller ''et al.''(1977).Suspended load

Suspended load is carried in the lower to middle parts of the flow, and moves at a large fraction of the mean flow velocity in the stream. A common characterization of suspended sediment concentration in a flow is given by the Rouse Profile. This characterization works for the situation in which sediment concentration at one particular elevation above the bed can be quantified. It is given by the expression: : Here, is the elevation above the bed, is the concentration of suspended sediment at that elevation, is the flow depth, is the Rouse number, and relates the eddy viscosity for momentum to the eddy diffusivity for sediment, which is approximately equal to one. : Experimental work has shown that ranges from 0.93 to 1.10 for sands and silts. The Rouse profile characterizes sediment concentrations because the Rouse number includes both turbulent mixing and settling under the weight of the particles. Turbulent mixing results in the net motion of particles from regions of high concentrations to low concentrations. Because particles settle downward, for all cases where the particles are not neutrally buoyant or sufficiently light that this settling velocity is negligible, there is a net negative concentration gradient as one goes upward in the flow. The Rouse Profile therefore gives the concentration profile that provides a balance between turbulent mixing (net upwards) of sediment and the downwards settling velocity of each particle.Bed material load

Bed material load comprises the bed load and the portion of the suspended load that is sourced from the bed. Three common bed material transport relations are the "Ackers-White", "Engelund-Hansen", "Yang" formulae. The first is for sand togranule

A granule is a large particle or grain. It can refer to:

* Granule (cell biology), any of several submicroscopic structures, some with explicable origins, others noted only as cell type-specific features of unknown function

** Azurophilic granul ...

-size gravel, and the second and third are for sand though Yang later expanded his formula to include fine gravel. That all of these formulae cover the sand-size range and two of them are exclusively for sand is that the sediment in sand-bed rivers is commonly moved simultaneously as bed and suspended load.

Engelund-Hansen

The bed material load formula of Engelund and Hansen is the only one to not include some kind of critical value for the initiation of sediment transport. It reads: : where is the Einstein nondimensionalization for sediment volumetric discharge per unit width, is a friction factor, and is the Shields stress. The Engelund-Hansen formula is one of the few sediment transport formulae in which a threshold "critical shear stress" is absent.Wash load

Wash load is carried within the water column as part of the flow, and therefore moves with the mean velocity of main stream. Wash load concentrations are approximately uniform in the water column. This is described by the endmember case in which the Rouse number is equal to 0 (i.e. the settling velocity is far less than the turbulent mixing velocity), which leads to a prediction of a perfectly uniform vertical concentration profile of material.Total load

Some authors have attempted formulations for the total sediment load carried in water. These formulas are designed largely for sand, as (depending on flow conditions) sand often can be carried as both bed load and suspended load in the same stream or shoreface.Bed Load Sediment Mitigation at Intake Structures

Riverside intake structures used in water supply, canal diversions, and water cooling can experience entrainment of bed load (sand-size) sediments. These entrained sediments produce multiple deleterious effects such as reduction or blockage of intake capacity, feedwaterpump

A pump is a device that moves fluids (liquids or gases), or sometimes slurries, by mechanical action, typically converted from electrical energy into hydraulic energy. Pumps can be classified into three major groups according to the method they u ...

impeller damage or vibration, and result in sediment deposition in downstream pipelines and canals. Structures that modify local near-field secondary currents are useful to mitigate these effects and limit or prevent bed load sediment entry.

See also

* * * *References

External links

* Liu, Z. (2001)Sediment Transport

* Moore, A

Kent State. * Wilcock, P

January 26–28, 2004, University of California at Berkeley * Southard, J. B. (2007)

* Linwood, J,

Suspended Sediment Concentration and Discharge in a West London River.

{{Geologic Principles Fluid mechanics Sedimentology Environmental engineering Hydrology Physical geography Geological processes Transport phenomena