Timeline of diving technology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The timeline of underwater diving technology is a chronological list of notable events in the history of the development of underwater diving equipment. With the partial exception of

* 1838: Dr. Manuel Théodore Guillaumet invented a twin-hose demand regulator. On 19 June 1838, in London, England, a Mr. William Edward Newton filed a patent (no. 7695: "Diving apparatus") for a diaphragm-actuated, twin-hose demand valve for divers. However, it is believed that Mr. Newton was merely filing a patent on behalf of Dr. Guillaumet. The illustration of the apparatus in Newton's patent application is identical to that in Guillaumet's patent application; furthermore, Mr. Newton was apparently an employee of the British Office for Patents, who applied for patents on behalf of foreign applicants. It is demonstrated in surface-demand use. During the demonstration, use duration was limited to 30 minutes because the dive was in cold water without a diving suit.

* 1860: in

* 1838: Dr. Manuel Théodore Guillaumet invented a twin-hose demand regulator. On 19 June 1838, in London, England, a Mr. William Edward Newton filed a patent (no. 7695: "Diving apparatus") for a diaphragm-actuated, twin-hose demand valve for divers. However, it is believed that Mr. Newton was merely filing a patent on behalf of Dr. Guillaumet. The illustration of the apparatus in Newton's patent application is identical to that in Guillaumet's patent application; furthermore, Mr. Newton was apparently an employee of the British Office for Patents, who applied for patents on behalf of foreign applicants. It is demonstrated in surface-demand use. During the demonstration, use duration was limited to 30 minutes because the dive was in cold water without a diving suit.

* 1860: in

* 1856

* 1856

William Thompson

and his friend Mr Kenyon take the first under water photograph using a camera sealed in a metal box. *1893: Louis Boutan makes the first under water camera becoming the first underwater photographer and produces the first clear underwater photographs. * 1900: Louis Boutan published ''La Photographie sous-marine et les progrès de la photographie'' (''The Underwater Photography and the Advances in Photography''), the first book about underwater photography.

* 1960:

* 1960:

Diving Lore

from its origins to the aqualung breakthrough.

marinebio.org

Rebreather Diving History

Best Snorkel masks

History of Cave Diving

{{Authority control Diving technology History of underwater diving sv:Dykning#Historia

breath-hold diving

Freediving, free-diving, free diving, breath-hold diving, or skin diving is a form of underwater diving that relies on breath-holding until resurfacing rather than the use of breathing apparatus such as scuba gear.

Besides the limits of breath-h ...

, the development of underwater diving capacity, scope, and popularity, has been closely linked to available technology, and the physiological constraints of the underwater environment.

Primary constraints are

* the provision of breathing gas to allow endurance beyond the limits of a single breath,

* safely decompressing from high underwater pressure to surface pressure,

* the ability to see clearly enough to effectively perform the task,

* and sufficient mobility to get to and from the workplace.

Pre-industrial

* AncientRoman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

era.: There have been many instances of men swimming or diving for combat, but they always had to hold their breath, and had no diving equipment, except sometimes a hollow plant stem used as a snorkel.

* About 500 BC: (Information originally from Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

): During a naval campaign the Greek Scyllis was taken aboard ship as prisoner by the Persian King Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of D ...

. When Scyllis learned that Xerxes was to attack a Greek flotilla, he seized a knife and jumped overboard. The Persians could not find him in the water and presumed he had drowned. Scyllis made his way among all the ships in Xerxes's fleet, cutting each ship loose from its moorings; he used a hollow reed as snorkel to remain unobserved. Then he swam nine miles (15 kilometers) to rejoin the Greeks off Cape Artemisium.

* The use of diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

s was recorded by the Greek philosopher Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

in the 4th century BC: "...they enable the divers to respire equally well by letting down a cauldron

A cauldron (or caldron) is a large pot ( kettle) for cooking or boiling over an open fire, with a lid and frequently with an arc-shaped hanger and/or integral handles or feet. There is a rich history of cauldron lore in religion, mythology, and ...

, for this does not fill with water, but retains the air, for it is forced straight down into the water."

* 1300 or earlier: Persian divers were using diving goggles

Goggles, or safety glasses, are forms of protective eyewear that usually enclose or protect the area surrounding the eye in order to prevent particulates, water or chemicals from striking the eyes. They are used in chemistry laboratories and ...

with windows made of the polished outer layer of tortoiseshell.

* 15th century: Konrad Kyeser, illustrated his manual of military technology ''Bellifortis

''Bellifortis'' ("Strong in War", "War Fortifications") is the first fully illustrated manual of military technology written by Konrad Kyeser and dating from the start of the 15th century. It summarises material from classical writers on milit ...

'' with a diving suit

A diving suit is a garment or device designed to protect a diver from the underwater environment. A diving suit may also incorporate a breathing gas supply (such as for a standard diving dress or atmospheric diving suit). but in most cases the te ...

fitted with a hose to the surface. This diving suit drawing can also be seen in the manuscript Ms.Thott.290.2º, written by Hans Talhoffer

Hans Talhoffer (Dalhover, Talhouer, Thalhoffer, Talhofer; – after 1482) was a German fencing master. His martial lineage is unknown, but his writings make it clear that he had some connection to the tradition of Johannes Liechtenauer, the ...

, which reproduces sections of ''Bellifortis''.

* 15th century: Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on ...

made the first known mention of air tanks in Italy: he wrote in his Atlantic Codex (Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

) that systems were used at that time to artificially breathe under water, but he did not explain them in detail. Some drawings, however, showed different kinds of snorkels and an air tank (to be carried on the breast) that presumably should have no external connections. Other drawings showed a complete immersion kit, with a plunger suit which included a sort of mask with a box for air. The project was so detailed that it included a urine

Urine is a liquid by-product of metabolism in humans and in many other animals. Urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the urinary bladder. Urination results in urine being excreted from the body through the urethra.

Cellul ...

collector.

* 1535: Guglielmo de Lorena and Francesco de Marchi dived on a Roman vessel sunk in Lake Nemi

Lake Nemi ( it, Lago di Nemi, la, Nemorensis Lacus, also called Diana's Mirror, la, Speculum Dianae) is a small circular volcanic lake in the Lazio region of Italy south of Rome, taking its name from Nemi, the largest town in the area, that ...

using a one-man diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

invented by de Lorena.

* 1602: Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont

Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont (1553 – March 23, 1613 AD) was a Spanish soldier, painter, astronomer, musician and inventor.

He was born in Guendulain (Navarre).

He built an air-renovated diving suit that allowed a man to remain underwat ...

built an air-renovated diving suit that allowed a man to remain underwater in the Pisuerga

The Pisuerga is a river in northern Spain, the Duero's second largest tributary. It rises in the Cantabrian Mountains in the province of Palencia, autonomous region of Castile and León.

Its traditional source is called Fuente Cobre, but it h ...

river on August 2. The diver passed an hour underwater before being ordered to return by King Philip III.

* 1616: Franz Kessler

Franz Kessler (c. 1580–1650) was a portrait painter, scholar, inventor and alchemist living in the Holy Roman Empire during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Writing

He wrote a number of books and pamphlets: a book on stoves, on making sundials ...

built an improved diving bell.

* Around 1620: Cornelis Drebbel may have made a crude rebreather

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's breathing, exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. ...

.

* 1650: Otto von Guericke built the first air pump.

* 1715:

** the ''chevalier

Chevalier may refer to:

Honours Belgium

* a rank in the Belgian Order of the Crown

* a rank in the Belgian Order of Leopold

* a rank in the Belgian Order of Leopold II

* a title in the Belgian nobility

France

* a rank in the French Legion d'h ...

'' Pierre Rémy de Beauve, a French aristocrat who served as ''garde de la marine In France, under the Ancien Régime, the Gardes de la Marine (Guards of the Navy), or Gardes-Marine were young gentlemen undergoing training to be naval officers. The training program was established by Cardinal Richelieu in 1670 and lasted until A ...

'' in Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

, built one of the oldest known diving dresses. De Beauve's dress was equipped with a metal helmet and two hoses, one of them air-supplied from the surface by a bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtig ...

and the other one for evacuation of the exhaled air.

** the Englishman John Lethbridge

John Lethbridge (1675–1759) invented the first underwater diving machine in 1715. He lived in the county of Devon in South West England and reportedly had 17 children. He is the subject of the Fisherman's Friends song John in the Barrel.

John ...

, a wool merchant, invented a diving suit built like a barrel with armholes and a viewport, and successfully used it to salvage valuables from wrecks.

Industrial era

Start of modern diving

* 1772: the first diving dress using a compressed-air reservoir was successfully designed and built in 1772 by ''Sieur'' Fréminet, a Frenchman fromParis

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

. Fréminet conceived an autonomous breathing machine equipped with a helmet, two hoses for inhalation and exhalation, a suit and a reservoir, dragged by and behind the diver, although Fréminet later put it on his back. Fréminet called his invention ''machine hydrostatergatique'' and used it successfully for more than ten years in the harbours of Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

and Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

, as stated in the explanatory text of a 1784 painting.

* 1774: John Day became the first person known to have died in an underwater accident while testing a "diving chamber" in Plymouth Sound

Plymouth Sound, or locally just The Sound, is a deep inlet or sound in the English Channel near Plymouth in England.

Description

Its southwest and southeast corners are Penlee Point in Cornwall and Wembury Point in Devon, a distance of abou ...

.

* 1776: David Bushnell

David Bushnell (August 30, 1740 – 1824 or 1826), of Westbrook, Connecticut, was an American inventor, a patriot, one of the first American combat engineers, a teacher, and a medical doctor.

Bushnell invented the first submarine to be used in ...

invented the ''Turtle'', first submarine to attack another ship. It was used in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

.

* 1797: Karl Heinrich Klingert designed a full diving dress which consisted of a large metal helmet and similarly large metal belt connected by a leather jacket and pants.

* 1798: in June, F. W. Joachim, employed by Klingert, successfully completed the first practical tests of Klingert's armor.

* 1800: Captain Peter Kreeft of Germany dived several times with his helmet diving equipment to show it to King Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden.

* 1800: Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 – February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the (also known as ''Clermont''). In 1807, that steamboa ...

built a submarine, the "Nautilus

The nautilus (, ) is a pelagic marine mollusc of the cephalopod family Nautilidae. The nautilus is the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina.

It comprises six living species in ...

".

* 1825: Johan Patrik Ljungström demonstrated his diving bell built of tinned

Tinning is the process of thinly coating sheets of wrought iron or steel with tin, and the resulting product is known as tinplate. The term is also widely used for the different process of coating a metal with solder before soldering.

It is mos ...

copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

with space for a crew of 2-3 persons, equipped with compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself wit ...

and methods of communication to the surface, successfully diving down to about 16 meters with Ljungström and an assistant on board, and wrote a book on the organization of private underwater diving

*c1831: American Charles Condert built an autonomous diving suit, using a copper pipe curved in the form of a horseshoe, displacing about 50 pounds of water, and worn at the waist, as an air reservoir which fed compressed air through a manually operated valve and a hose into an airtight rubberised hip length tunic with integral hood. Air escaped from a small hole in the hood. The buoyancy of the set required about 200 pounds of weight for ballast. Condert made several dives in the East River to about 20ft, and was drowned on his last dive in 1832.

* 1837: Captain William H. Taylor demonstrated his "submarine dress" at the annual American Institute Fair

The American Institute Fair was held annually from 1829 until at least 1897 in New York City by the American Institute. The American Institute was founded in 1829 "for the encouragement of agriculture, commerce, manufactures, and the arts." The ...

at Niblo's Garden, New York City.

* 1839:

** Canadian inventors James Eliot and Alexander McAvity of Saint John, New Brunswick

Saint John is a seaport city of the Atlantic Ocean located on the Bay of Fundy in the province of New Brunswick, Canada. Saint John is the oldest incorporated city in Canada, established by royal charter on May 18, 1785, during the reign of K ...

patented an "oxygen reservoir for divers", a device carried on the diver's back containing "a quantity of condensed oxygen gas or common atmospheric air proportionate to the depth of water and adequate to the time he is intended to remain below".

** W.H.Thornthwaite of Hoxton

Hoxton is an area in the London Borough of Hackney, England. As a part of Shoreditch, it is often considered to be part of the East End – the historic core of wider East London. It was historically in the county of Middlesex until 1889. It li ...

in London patented an inflatable lifting jacket for divers.

* Around 1842: The Frenchman Joseph-Martin Cabirol (1799–1874) formed a company in Paris and started making standard diving dress

Standard diving dress, also known as hard-hat or copper hat equipment, deep sea diving suit or heavy gear, is a type of diving suit that was formerly used for all relatively deep underwater work that required more than breath-hold duration, which ...

.

* 1843: Based on lessons learned from the Royal George salvage, the first diving school was set up by the Royal Navy.

* 1845 James Buchanan Eads designed and built a diving bell and began salvaging cargo from the bottom of the Mississippi River, eventually working on the river bottom from the mouth of the river at the Gulf of Mexico to Iowa.

* 1856: Wilhelm Bauer

Wilhelm Bauer (23 December 1822 – 20 June 1875) was a German inventor and engineer who built several hand-powered submarines.

Biography

Wilhelm Bauer was born in Dillingen in the Kingdom of Bavaria. His father was a sergeant of a Bavarian ...

started the first of 133 successful dives with his second submarine '' Seeteufel''. The crew of 12 was trained to leave the submerged ship through a diving chamber (airlock).

* 1860: Giovanni Luppis

Giovanni (Ivan) Biagio Luppis Freiherr von Rammer (27 August 1813 – 11 January 1875), sometimes also known by the Croatian name of Vukić, was an officer of the Austro-Hungarian Navy who headed a commission to develop the first prototypes o ...

, a retired engineer of the Austro-Hungarian navy, demonstrated a design for a self-propelled torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

to emperor Franz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

.

* 1864: '' H.L. Hunley'' became the first submarine to sink a ship, the USS ''Housatonic'', during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

.

* 1866: ''Minenschiff'', the first self-propelled (locomotive) torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

, developed by Robert Whitehead

Robert Whitehead (3 January 1823 – 14 November 1905) was an English engineer who was most famous for developing the first effective self-propelled naval torpedo.

Early life

He was born in Bolton, England, the son of James Whitehead, ...

(to a design by Captain Luppis, Austrian Navy), was demonstrated for the imperial naval commission on 21 December.

* 1882: Brothers Alphonse and Théodore Carmagnolle of Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

, France, patented the first properly anthropomorphic design of ADS ( atmospheric diving suit). Featuring 22 rolling convolute joints that were never entirely waterproof and a helmet with 25 glass viewing ports, it weighed and was never put in service.

Rebreathers

* 1808: on 17 June, ''Sieur'' Pierre-Marie Touboulic fromBrest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

, a mechanic in Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's Imperial Navy, patented the oldest known oxygen rebreather

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's breathing, exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. ...

, but there is no evidence of any prototype having been manufactured. This early rebreather design worked with an oxygen reservoir, the oxygen being delivered progressively by the diver himself and circulating in a closed circuit through a sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate throug ...

soaked in limewater. Touboulic called his invention ''Ichtioandre'' (Greek for 'fish-man').

* 1849: Pierre-Aimable de Saint Simon Sicard (a chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe t ...

) made the first practical oxygen rebreather. It was demonstrated in London in 1854.

*1853: Professor T. Schwann designed a rebreather in Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

which he exhibited in Paris in 1878. It had a big backpack tank containing oxygen at about 13 bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

, and two scrubbers containing sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate throug ...

s soaked in caustic soda

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula NaOH. It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly caustic base and alkali ...

.

* 1876: An English merchant seaman, Henry Fleuss

Henry Albert Fleuss (13 June 1851 – 6 January 1933) was a pioneering diving engineer, and Master Diver for Siebe, Gorman & Co. of London.

Fleuss was born in Marlborough, Wiltshire in 1851.

In 1878 he was granted a patent which improved rebr ...

, developed the first workable self-contained diving rig that used compressed oxygen. This prototype of closed-circuit scuba used rope soaked in caustic potash to absorb carbon dioxide so the exhaled gas could be re-breathed.

Diving helmets improved and in common use

* 1808: Brizé-Fradin designed a small bell-like helmet connected to a low-pressure backpack air container. * 1820:Paul Lemaire d'Augerville

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

* Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

(a Parisian dentist) invented a diving apparatus with a copper backpack cylinder, a counterlung

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. Oxygen is ...

to save air, and with an inflatable life jacket connected. It was used down to 15 or 20 meters for up to an hour in salvage work. He started a successful salvage company.

* 1825: William H. James designed a self-contained diving suit with compressed air stored in an iron container worn around the waist.

* 1827: Beaudouin in France developed a diving helmet fed from an air cylinder pressurized to 80 to 100 bar. The French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

was interested, but nothing came of this.

* 1829: (1828?)

**Charles Anthony Deane

Charles Anthony Deane (1796–1848) was a pioneering diving engineer, inventor of the diving helmet.

Life

Born in Deptford, Charles and his brother John studied at the Greenwich Hospital School for Boys (the former buildings of which are now ...

and John Deane of Whitstable

Whitstable () is a town on the north coast of Kent adjoining the convergence of the Swale Estuary and the Greater Thames Estuary in southeastern England, north of Canterbury and west of Herne Bay. The 2011 Census reported a population of ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

in England designed the first diving helmet

A diving helmet is a rigid head enclosure with a breathing gas supply used in underwater diving. They are worn mainly by professional divers engaged in surface-supplied diving, though some models can be used with scuba equipment. The upper part ...

supplied with airpumped from the surface, for use with a diving suit. It is said that the idea started from a crude emergency rig-up of a fireman

A firefighter is a first responder and rescuer extensively trained in firefighting, primarily to extinguish hazardous fires that threaten life, property, and the environment as well as to rescue people and in some cases or jurisdictions also ...

's water-pump (used as an air pump) and a knight-in-armour helmet used to try to rescue horses from a burning stable. Others say that it was based on earlier work in 1823 developing a "smoke helmet". The suit was not attached to the helmet, so a diver could not bend over or invert without risk of flooding the helmet and drowning. Nevertheless, the diving system was used in salvage work, including the successful removal of cannon from the British warship HMS ''Royal George'' in 1834–35. This 108-gun fighting ship sank in 65 feet of water at Spithead anchorage in 1783.

** E.K.Gauzen, a Russian naval technician of the Kronshtadt naval base

A naval base, navy base, or military port is a military base, where warships and naval ships are docked when they have no mission at sea or need to restock. Ships may also undergo repairs. Some naval bases are temporary homes to aircraft that u ...

in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

), built a "diving machine". His invention was a metallic helmet strapped to a leather suit (an overall) with a pumped air supply. The bottom of the helmet was open, and the helmet strapped to the suit by a metal band. Gauzen's diving suit and its further modifications were used by the Russian Navy until 1880. The modified diving suit

A diving suit is a garment or device designed to protect a diver from the underwater environment. A diving suit may also incorporate a breathing gas supply (such as for a standard diving dress or atmospheric diving suit). but in most cases the te ...

of the Russian Navy, based on Gauzen's invention, was known as " three-bolt equipment".

* 1837: Following up Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on ...

's studies, and those of the astronomer Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, H ...

, Augustus Siebe developed surface supplied diving apparatus which became known as standard diving dress

Standard diving dress, also known as hard-hat or copper hat equipment, deep sea diving suit or heavy gear, is a type of diving suit that was formerly used for all relatively deep underwater work that required more than breath-hold duration, which ...

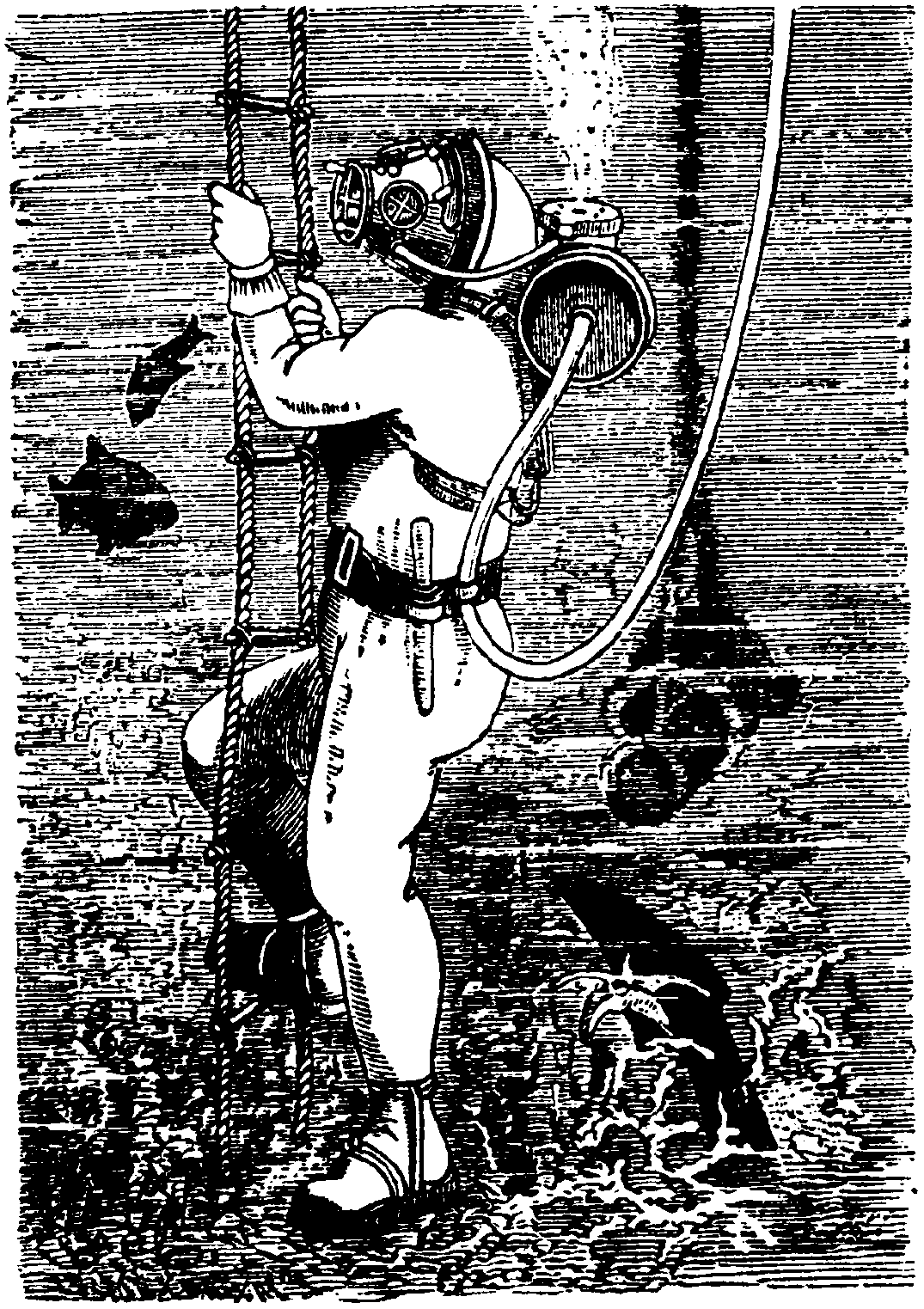

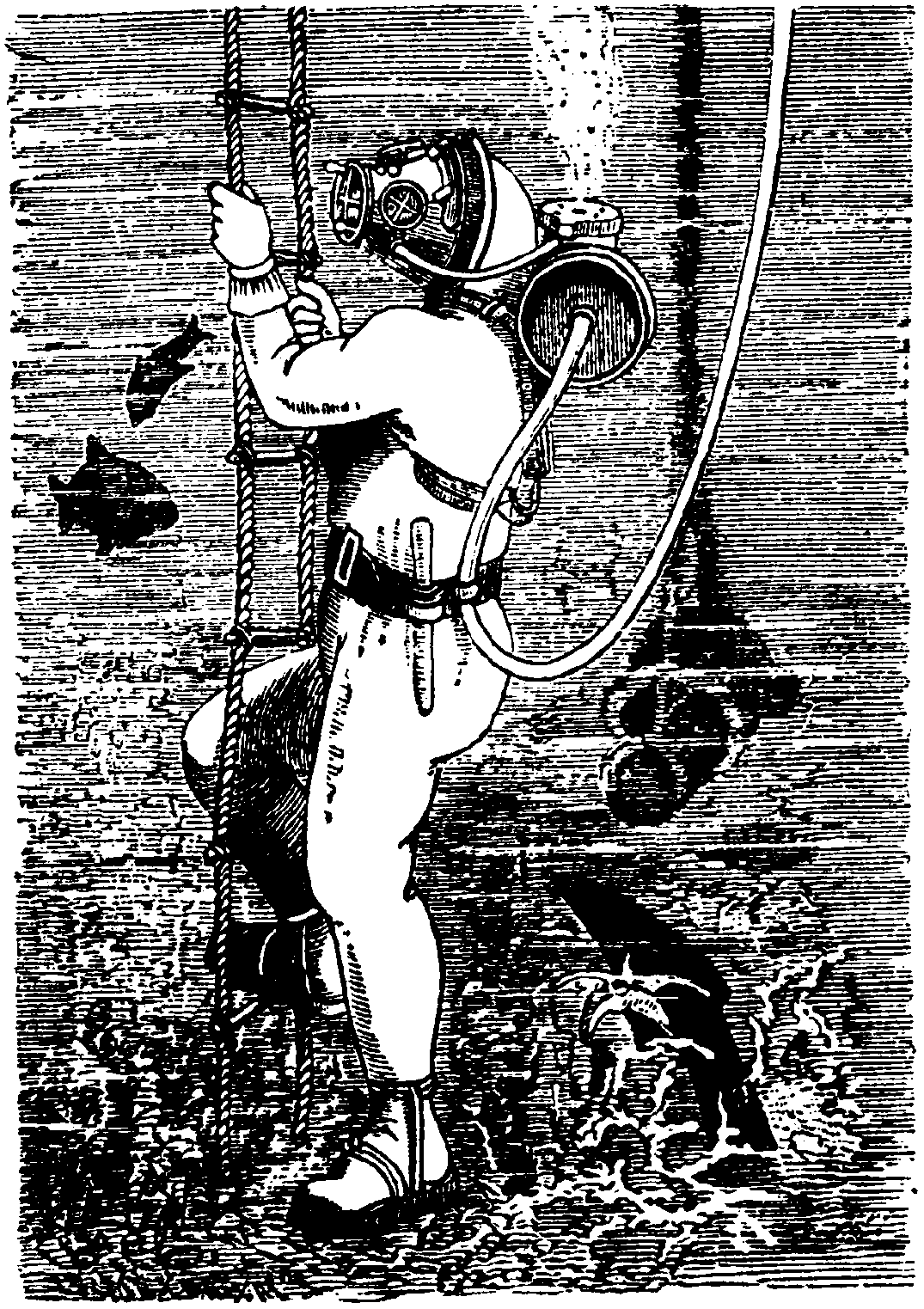

. By sealing the Deane brothers' helmet design to a waterproof suit, Augustus Siebe developed the Siebe "Closed" Dress combination diving helmet and suit, considered the foundation of modern diving dress. This was a significant evolution from previous models of "open" dress that did not allow a diver to invert. Siebe-Gorman went on to manufacture helmets continuously until 1975.

* 1840: The Royal Navy used Siebe closed dress for salvage and blasting work on the "Royal George", and subsequently the Royal Engineers standardised on this equipment.

* 1843: The Royal Navy established the first diving school.

* 1855: Joseph-Martin Cabirol patented a new model of standard diving dress, mainly issued from Siebe's designs. The suit was made out of rubberized canvas and the helmet, for the first time, included a hand-controlled tap that the diver used to evacuate his exhaled air. The exhaust valve included a non-return valve which prevented water from entering in the helmet. Until 1855 diving helmets were equipped with only three circular windows (for front, left and right sides). Cabirol's helmet introduced the later well known fourth window, situated in the upper front part of the helmet and allowing the diver to see above him. Cabirol's diving dress won the silver medal at the 1885 ''Exposition Universelle'' in Paris. This original diving dress and helmet are now preserved at the ''Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers

A music school is an educational institution specialized in the study, training, and research of music. Such an institution can also be known as a school of music, music academy, music faculty, college of music, music department (of a larger ins ...

'' in Paris.

The first diving regulators

* 1838: Dr. Manuel Théodore Guillaumet invented a twin-hose demand regulator. On 19 June 1838, in London, England, a Mr. William Edward Newton filed a patent (no. 7695: "Diving apparatus") for a diaphragm-actuated, twin-hose demand valve for divers. However, it is believed that Mr. Newton was merely filing a patent on behalf of Dr. Guillaumet. The illustration of the apparatus in Newton's patent application is identical to that in Guillaumet's patent application; furthermore, Mr. Newton was apparently an employee of the British Office for Patents, who applied for patents on behalf of foreign applicants. It is demonstrated in surface-demand use. During the demonstration, use duration was limited to 30 minutes because the dive was in cold water without a diving suit.

* 1860: in

* 1838: Dr. Manuel Théodore Guillaumet invented a twin-hose demand regulator. On 19 June 1838, in London, England, a Mr. William Edward Newton filed a patent (no. 7695: "Diving apparatus") for a diaphragm-actuated, twin-hose demand valve for divers. However, it is believed that Mr. Newton was merely filing a patent on behalf of Dr. Guillaumet. The illustration of the apparatus in Newton's patent application is identical to that in Guillaumet's patent application; furthermore, Mr. Newton was apparently an employee of the British Office for Patents, who applied for patents on behalf of foreign applicants. It is demonstrated in surface-demand use. During the demonstration, use duration was limited to 30 minutes because the dive was in cold water without a diving suit.

* 1860: in Espalion

Espalion (; oc, Espaliu) is a commune in the Aveyron department in southern France.

Population

Sights

*Château de Calmont d'Olt

*The Pont-Vieux (Old Bridge) is part of the World Heritage Sites of the Routes of Santiago de Compostela in Fr ...

(France), mining engineer Benoît Rouquayrol designed a self-contained breathing set with a backpack cylindrical air tank that supplied air through the first demand regulator to be commercialized (as of 1865, see below). Rouquayrol calls his invention ''régulateur'' ('regulator'), having conceived it to help miners avoid drowning in flooded mines.

* 1864: Benoît Rouquayrol met navy officer Auguste Denayrouze for the first time, in Espalion, and on Denayrouze's initiative, they adapted Rouquayrol's invention to diving. After having adapted it, they called their recently patented device ''appareil plongeur Rouquayrol-Denayrouze'' ('Rouquayrol-Denayrouze diving apparatus'). The diver still walked on the seabed and did not swim. The air pressure tanks made with the technology of the time could only hold 30 atmospheres, allowing dives of only 30 minutes at no more than ten meters deep; during surface-supplied configuration the tank was also used for bailout

A bailout is the provision of financial help to a corporation or country which otherwise would be on the brink of bankruptcy.

A bailout differs from the term ''bail-in'' (coined in 2010) under which the bondholders or depositors of global sys ...

in the case of a hose failure.

* 1865: on August the 28th the French Navy Minister ordered the first Rouquayrol-Denayrouze diving apparatus and large scale production started.

Gas and air cylinders appear

* Late 19th century:Industry

Industry may refer to:

Economics

* Industry (economics), a generally categorized branch of economic activity

* Industry (manufacturing), a specific branch of economic activity, typically in factories with machinery

* The wider industrial sector ...

began to be able to make high-pressure air and gas cylinders. That prompted a few inventors down the years to design open-circuit compressed air breathing sets, but they were all constant-flow, and the demand regulator did not come back until 1937.

Underwater photography

* 1856

* 1856William Thompson

and his friend Mr Kenyon take the first under water photograph using a camera sealed in a metal box. *1893: Louis Boutan makes the first under water camera becoming the first underwater photographer and produces the first clear underwater photographs. * 1900: Louis Boutan published ''La Photographie sous-marine et les progrès de la photographie'' (''The Underwater Photography and the Advances in Photography''), the first book about underwater photography.

Decompression sickness recognised as a problem

* 1841: Jacques Triger constructs the first caisson for mining work in France. First two cases of decompression sickness in caisson workers are reported by Triger in 1845, consisting of joint and extremity pains. * 1846-1855: Several cases of decompression sickness, some with fatal outcome, reported in caisson workers during bridge construction first in France, then in England. Recompression is reported to help alleviate symptoms by Pol and Wattelle in 1847, and a gradual compression and decompression is advocated by Thomas Littleton in 1855. * From 1870 to 1910 all prominent features of decompression sickness were established, but theories over the pathology ranged from cold or exhaustion causing reflex spinal cord damage; electricity caused byfriction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of ...

on compression; or organ congestion and vascular stasis caused by decompression.

* 1870: Louis Bauer, a professor of surgery from St. Lous, publishes an initial report on the outcomes of 25 paralyzed caisson workers involved in the construction of the St Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

Eads Bridge

The Eads Bridge is a combined road and railway bridge over the Mississippi River connecting the cities of St. Louis, Missouri and East St. Louis, Illinois. It is located on the St. Louis riverfront between Laclede's Landing, to the north, and ...

. The construction project eventually employed 352 compressed air workers including Dr. Alphonse Jaminet as the physician in charge. There were 30 seriously injured and 12 fatalities. Dr. Jaminet himself suffered a case of decompression sickness when he ascended to the surface in four minutes after spending almost three hours at a depth of 95 feet in a caisson, and his description of his own experience was the first such recorded. While obviously caused by the increased pressure, both Bauer and Jaminet theorize that the symptoms are caused by a hypermetabolic state caused by the increase in oxygen, with inability to remove waste products in normal pressure. Gradual compression and decompression, shorter shifts with longer intervals, and complete rest after decompression are advocated. Actual cases are treated with rest, beef tea, ice, and alcohol.

* 1872: The similarity between decompression sickness and iatrogenic

Iatrogenesis is the causation of a disease, a harmful complication, or other ill effect by any medical activity, including diagnosis, intervention, error, or negligence. "Iatrogenic", ''Merriam-Webster.com'', Merriam-Webster, Inc., accessed 27 ...

air embolism as well as the relationship between inadequate decompression and decompression sickness were noted by Hermann Friedberg. He suggested that intravascular gas was released by rapid decompression and recommended: slow compression and decompression; four-hour working shifts; limit to maximum depth 44.1 psig

The pound per square inch or, more accurately, pound-force per square inch (symbol: lbf/in2; abbreviation: psi) is a unit of pressure or of stress based on avoirdupois units. It is the pressure resulting from a force of one pound-force applied to ...

(4 ATA); using only healthy workers; and recompression treatment for severe cases.

* 1873: Dr. Andrew Smith first used the term "caisson disease" to describe 110 cases of decompression sickness as the physician in charge during construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. The project employed 600 compressed air workers. Recompression treatment was not used. The project chief engineer Washington Roebling

Washington Augustus Roebling (May 26, 1837 – July 21, 1926) was an American civil engineer who supervised the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, designed by his father John A. Roebling. He served in the Union Army during the American Civ ...

suffered from caisson disease. (He took charge after his father John Augustus Roebling died of tetanus

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is a bacterial infection caused by ''Clostridium tetani'', and is characterized by muscle spasms. In the most common type, the spasms begin in the jaw and then progress to the rest of the body. Each spasm usually ...

.) Washington's wife, Emily, helped manage the construction of the bridge after his sickness confined him to his home in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

. He battled the after-effects of the disease for the rest of his life.

According to different sources, the term "The Bends" for decompression sickness was coined by workers of either the Brooklyn or the Eads bridge, and was given because afflicted individuals characteristically arched their backs in a manner similar to a then-fashionable posture known as the Grecian Bend

The Grecian bend was a term applied first to a stooped posture which became fashionable c. 1820, named after the gracefully-inclined figures seen in the art of ancient Greece. It was also the name of a dance move introduced to polite society in Am ...

.

* 1878: Paul Bert

Paul Bert (17 October 1833 – 11 November 1886) was a French zoologist, physiologist and politician. He is sometimes given the sobriquet "Father of Aviation Medicine".

Life

Bert was born at Auxerre (Yonne). He studied law, earning a doctorate ...

published ''La Pression barométrique'', providing the first systematic understanding of the causes of DCS.

Twentieth century

* 1900: John P. Holland built the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the U.S. Navy, ''Holland'' (also called ''A-1''). ** Leonard Hill used a frog model to prove that decompression causes bubbles and that recompression resolves them. * 1903:Siebe Gorman

Siebe Gorman & Company Ltd was a British company that developed diving equipment and breathing equipment and worked on commercial diving and marine salvage projects. The company advertised itself as 'Submarine Engineers'. It was founded by Au ...

started to make a submarine escape set

An escape set (in German ''Tauchretter'' = "diving rescuer") is a breathing set that allows its wearer to survive for a time in an environment without (sufficiently) breathable air.

Early escape sets were rebreathers and were typically used to ...

in England; in the years afterwards it was improved, and later was called the Davis Escape Set

The Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus (also referred to as DSEA), was an early type of oxygen rebreather invented in 1910 by Sir Robert Davis, head of Siebe Gorman and Co. Ltd., inspired by the earlier Fleuss system, and adopted by the Royal Na ...

or Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus

The Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus (also referred to as DSEA), was an early type of oxygen rebreather invented in 1910 by Sir Robert Davis, head of Siebe Gorman and Co. Ltd., inspired by the earlier Fleuss system, and adopted by the Royal Na ...

.

* from 1903 to 1907: Professor Georges Jaubert, invented Oxylithe, a mixture of peroxides of sodium (Na2O2) and potassium with a small amount of salts of copper or nickel, which produces oxygen in the presence of water.

* 1905:

** Several sources, including the 1991 US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

Dive Manual (pg 1–8), state that the MK V Deep Sea Diving Dress was designed by the Bureau of Construction & Repair in 1905, but in reality, the 1905 Navy Handbook shows British Siebe-Gorman helmets in use. Since the earliest known MK V is dated 1916, these sources are probably referring to the earlier MK I, MK II, MK III & MK IV Morse

Morse may refer to:

People

* Morse (surname)

* Morse Goodman (1917-1993), Anglican Bishop of Calgary, Canada

* Morse Robb (1902–1992), Canadian inventor and entrepreneur

Geography Antarctica

* Cape Morse, Wilkes Land

* Mount Morse, Churchi ...

and Schrader helmets.

** The first rebreather with metering valves to control the supply of oxygen was made.

* 1907: Draeger of Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the state ...

made a rebreather

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's breathing, exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. ...

called the ''U-Boot-Retter.'' (submarine rescuer).

* 1908:

** Arthur Boycott, Guybon Damant, and John Haldane published "The Prevention of Compressed-Air Illness", detailed studies on the cause and symptoms of decompression sickness, and proposed a table of decompression stop

The practice of decompression by divers comprises the planning and monitoring of the profile indicated by the algorithms or tables of the chosen decompression model, to allow asymptomatic and harmless release of excess inert gases dissolved in ...

s to avoid the effects.

** The Admiralty Deep Diving Committee adopted the Haldane tables for the Royal Navy, and published Haldane's diving tables to the general public.

* 1910: the British Robert Davis invented his own submarine rescuer rebreather, the Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus

The Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus (also referred to as DSEA), was an early type of oxygen rebreather invented in 1910 by Sir Robert Davis, head of Siebe Gorman and Co. Ltd., inspired by the earlier Fleuss system, and adopted by the Royal Na ...

, for the Royal Navy submarine crews.

* 1912:

** US Navy adopted the decompression tables published by Haldane, Boycott and Damant. Driven by Chief Gunner George Stillson, the navy set up a program to test tables and staged decompression based on the work of Haldane.

** Maurice Fernez

Maurice Fernez (30 August 1885 - 31 January 1952, Alfortville, Paris, France) was a French inventor and pioneer in the field of underwater breathing apparatus, respirators and gas masks. He was pivotal in the transition of diving from the tethered ...

introduced a simple lightweight underwater breathing apparatus as an alternative to helmet diving suits.

** Dräger started the commercialization of his rebreather in both configuration types, mouthpiece and helmet.

* 1913: The US Navy began developing the future MK V, influenced by Schrader and Morse

Morse may refer to:

People

* Morse (surname)

* Morse Goodman (1917-1993), Anglican Bishop of Calgary, Canada

* Morse Robb (1902–1992), Canadian inventor and entrepreneur

Geography Antarctica

* Cape Morse, Wilkes Land

* Mount Morse, Churchi ...

designs.

* 1914: Modern swimfins were invented by the Frenchman Louis de Corlieu, ''capitaine de corvette'' (Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding ran ...

) in the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

. In 1914 De Corlieu made a practical demonstration of his first prototype for a group of navy officers.

* 1915: The submarine was salvaged from 304 feet establishing the practical limits for air diving. Three US Navy divers, Frank W. Crilley, William F. Loughman, and Nielson, reached 304 fsw using the MK V dress.

* 1916:

** The basic design of the MK V dress was finalized by including a battery-powered telephone, but several more detail improvements were made over the next two years.

** The Draeger model DM 2 became standard equipment of the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Kaise ...

.

* 1917: The Bureau of Construction & Repair adopted the MK V helmet and dress, which remained the standard for US Navy diving until the introduction of the MK 12 in the late seventies.

* 1918: the "Ohgushi's Peerless Respirator" was first patented. Invented in 1916 by Riichi Watanabi and the blacksmith Kinzo Ohgushi, and used with either surface supplied air or a 150 bar steel scuba cylinder holding 1000 litres free air, the valve supplied air to a mask over the diver's nose and eyes and the demand valve was operated by the diver's teeth. Gas flow was proportional to bite force and duration. The breathing apparatus was used successfully for fishing and salvage work and by the military Japanese Underwater Unit until the end of the Pacific War.

* Around 1920: Hanseatischen Apparatebau-Gesellschaft made a 2-cylinder breathing apparatus with double-lever single-stage demand valve and single wide corrugated breathing tube with mouthpiece, and a "duck's beak" exhalent valve in the regulator. It was described in a mine rescue

Mine rescue or mines rescue is the specialised job of rescuing miners and others who have become trapped or injured in underground mines because of mining accidents, roof falls or floods and disasters such as explosions.

Background

Mining ...

handbook in 1930. They were successors to Ludwig von Bremen of Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

, who had the licence to make the Rouquayrol-Denayrouze apparatus in Germany.

* 1924:

** De Corlieu left the French Navy to fully devote himself to his invention.

** Experimental dives using helium-oxygen mixtures sponsored by the US Navy and Bureau of Mines.

* 1925:

**Maurice Fernez

Maurice Fernez (30 August 1885 - 31 January 1952, Alfortville, Paris, France) was a French inventor and pioneer in the field of underwater breathing apparatus, respirators and gas masks. He was pivotal in the transition of diving from the tethered ...

introduced a new model of his underwater surface-supplied apparatus at the Grand Palais. Yves le Prieur, an assistant at the exhibition, decided to meet Fernez in person and asked him to transform the equipment into a manually-controlled constant flow self-contained underwater breathing apparatus

A scuba set, originally just scuba, is any breathing apparatus that is entirely carried by an underwater diver and provides the diver with breathing gas at the ambient pressure. ''Scuba'' is an anacronym for self-contained underwater breathing ...

.

** Due to post World War I cutbacks, the US Navy found it had only 20 divers qualified to dive deeper than 90 feet when salvaging the submarine S-51.

* 1926:

** Fernez-Le Prieur self-contained underwater breathing apparatus was demonstrated to the public in Paris, and adopted by the French Navy.

** Dräger introduced a rescue breathing apparatus that the wearer could swim with. Previous devices served only for submarine escape and were designed to provide buoyancy so that the wearer was lifted to the surface without effort, the diving set had weights, which made it possible to dive for search and rescue after an accident.

*1927: US Navy School of Diving and Salvage

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

was re-established at Washington Navy Yard, and the Experimental Diving Unit brought from Pittsburgh to Washington Navy Yard.

*1928: Davis invented the Submersible Decompression Chamber (SDC) diving bell.

*1929: Lieutenant C.B."Swede" Momsen, a submariner and diver, developed and tested the submarine escape apparatus named the Momsen Lung

The Momsen lung was a primitive underwater rebreather used before and during World War II by American submariners as emergency escape gear. It was invented by Charles Momsen (nicknamed "Swede"). Submariners trained with this apparatus in an dee ...

.

* The 1930s:

**In France, Guy Gilpatric started swim diving with waterproof goggles, derived from the swimming goggles which were invented by Maurice Fernez

Maurice Fernez (30 August 1885 - 31 January 1952, Alfortville, Paris, France) was a French inventor and pioneer in the field of underwater breathing apparatus, respirators and gas masks. He was pivotal in the transition of diving from the tethered ...

in 1920.

**Sport spearfishing

Spearfishing is a method of fishing that involves impaling the fish with a straight pointed object such as a spear, gig or harpoon. It has been deployed in artisanal fishing throughout the world for millennia. Early civilisations were familia ...

became common in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

, and spearfishers gradually developed the diving mask

Diving most often refers to:

* Diving (sport), the sport of jumping into deep water

* Underwater diving, human activity underwater for recreational or occupational purposes

Diving or Dive may also refer to:

Sports

* Dive (American football), ...

, fins and snorkel, with Georges Beuchat

Georges Beuchat (11 February 1910 – 20 October 1991) was a French inventor, underwater diver, businessman and emblematic pioneer of underwater activities and founder of Beuchat. Throughout his lifetime, Beuchat never ceased developing produ ...

in Marseille, France, who created the speargun

A speargun is a ranged underwater fishing device designed to launch a tethered spear or harpoon to impale fish or other marine animals and targets. Spearguns are used in sport fishing and underwater target shooting. The two basic types are ''pn ...

. Italian sport spearfishers started using oxygen rebreathers

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. Oxygen is ...

. This practice came to the attention of the Italian Navy, which developed its frogman unit Decima Flottiglia MAS

The ''Decima Flottiglia MAS'' (''Decima Flottiglia Motoscafi Armati Siluranti'', also known as ''La Decima'' or Xª MAS) (Italian for "10th Assault Vehicle Flotilla") was an Italian flotilla, with commando frogman unit, of the ''Regia Marina'' ...

.

* 1933:

** In April Louis de Corlieu registered a new patent (number 767013, which in addition to two fins for the feet included two spoon-shaped fins for the hands) and called this equipment ''propulseurs de natation et de sauvetage'' (which can be translated as "swimming and rescue propulsion device").

** In San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United Stat ...

, the first sport diving club was started by Glenn Orr, Jack Prodanovich and Ben Stone, called the San Diego Bottom Scratchers. As far as it is known, it did not use breathing sets; its main aim was spearfishing

Spearfishing is a method of fishing that involves impaling the fish with a straight pointed object such as a spear, gig or harpoon. It has been deployed in artisanal fishing throughout the world for millennia. Early civilisations were familia ...

.

** More is known of Yves Le Prieur's constant-flow open-circuit breathing set. It is said that it could allow a 20-minute stay at 7 meters and 15 minutes at 15 meters. It has one cylinder feeding into a circular fullface mask

A full-face diving mask is a type of diving mask that seals the whole of the diver's face from the water and contains a mouthpiece, demand valve or constant flow gas supply that provides the diver with breathing gas. The full face mask ha ...

. Its air cylinder was often worn at an angle to get its on/off valve in reach of the diver's hand.

* 1934:

** In France, Beuchat established a scuba diving

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface air supply. The name "scuba", an acronym for " Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus", was coined by Chr ...

and spearfishing

Spearfishing is a method of fishing that involves impaling the fish with a straight pointed object such as a spear, gig or harpoon. It has been deployed in artisanal fishing throughout the world for millennia. Early civilisations were familia ...

equipment manufacturing company.

** In France a sport diving club was started, called the ''Club des Sous-l'Eau'' = "club of those ho are

Ho (or the transliterations He or Heo) may refer to:

People Language and ethnicity

* Ho people, an ethnic group of India

** Ho language, a tribal language in India

* Hani people, or Ho people, an ethnic group in China, Laos and Vietnam

* Hiri M ...

under the water". It did not use breathing sets as far as is known. Its main aim was spearfishing

Spearfishing is a method of fishing that involves impaling the fish with a straight pointed object such as a spear, gig or harpoon. It has been deployed in artisanal fishing throughout the world for millennia. Early civilisations were familia ...

. ("''Club des Sous-l'Eau''" was later realized to be a homophone

A homophone () is a word that is pronounced the same (to varying extent) as another word but differs in meaning. A ''homophone'' may also differ in spelling. The two words may be spelled the same, for example ''rose'' (flower) and ''rose'' (p ...

of "''club des soulôts''" = "club of the drunkards", and was changed to ''Club des Scaphandres et de la Vie Sous L'Eau'' = "Club of the diving apparatuses and of underwater life".)

** Otis Barton

Frederick Otis Barton Jr. (June 5, 1899 – April 15, 1992) was an American deep-sea diver, inventor and actor.

Early life and career

Born in New York, the independently wealthy Barton designed the first bathysphere and made a dive with W ...

and William Beebe

Charles William Beebe ( ; July 29, 1877 – June 4, 1962) was an American naturalist, ornithologist, marine biologist, entomologist, explorer, and author. He is remembered for the numerous expeditions he conducted for the New York Zoological ...

dived to 3028 feet using a bathysphere

The Bathysphere (Greek: , , "deep" and , , "sphere") was a unique spherical deep-sea submersible which was unpowered and lowered into the ocean on a cable, and was used to conduct a series of dives off the coast of Bermuda from 1930 to 1934. The ...

.

* 1935: The French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

adopted the Le Prieur breathing set.

** On the French Riviera, the first known sport scuba diving club Club Des Scaphandres et de la Vie Sous L'eau (The club for divers and life underwater) was started by Le Prieur & Jean Painleve. It used Le Prieur's breathing sets.

* 1937: US Navy published its revised diving tables based on the work of O.D. Yarbrough.

* 1937: The American Diving Equipment and Salvage Company

Diving most often refers to:

* Diving (sport), the sport of jumping into deep water

* Underwater diving, human activity underwater for recreational or occupational purposes

Diving or Dive may also refer to:

Sports

* Dive (American football), a ...

(now known as DESCO) developed a heavy bottom-walking-type diving suit with a self-contained mixed-gas helium and oxygen rebreather.

* 1939: After floundering for years, even producing his fins in his own flat

Flat or flats may refer to:

Architecture

* Flat (housing), an apartment in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and other Commonwealth countries

Arts and entertainment

* Flat (music), a symbol () which denotes a lower pitch

* Flat (soldier), ...

in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, De Corlieu finally started mass production of his invention in France. The same year he rented a licence to Owen P. Churchill for mass production in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

. To sell his fins in the USA Owen Churchill changed the French De Corlieu's name (''propulseurs'') to "swimfins", which is still the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

name. Churchill presented his fins to the US Navy, who decided to acquire them for its Underwater Demolition Team

Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT), or frogmen, were amphibious units created by the United States Navy during World War II with specialized non-tactical missions. They were predecessors of the navy's current SEAL teams.

Their primary WWII fun ...

(UDT).

** Hans Hass

Hans Hass (23 January 1919 – 16 June 2013) was an Austrian biologist and underwater diving pioneer. He was known mainly for being among the first scientists to popularise coral reefs, stingrays, octopuses and sharks. He pioneered the making o ...

and Hermann Stelzner of Dräger, in Germany made the M138 rebreather. It was developed from the 1912 escape set

An escape set (in German ''Tauchretter'' = "diving rescuer") is a breathing set that allows its wearer to survive for a time in an environment without (sufficiently) breathable air.

Early escape sets were rebreathers and were typically used to ...

, a type of rebreather used to exit sunken submarines. The M138 sets were oxygen rebreathers with a 150 bar, 0.6 liter tank and appeared in many of his movie

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmosphere ...

s and books.

* 1941: The Italian Navy's Decima Flottiglia MAS

The ''Decima Flottiglia MAS'' (''Decima Flottiglia Motoscafi Armati Siluranti'', also known as ''La Decima'' or Xª MAS) (Italian for "10th Assault Vehicle Flotilla") was an Italian flotilla, with commando frogman unit, of the ''Regia Marina'' ...

using oxygen rebreathers

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. Oxygen is ...

and manned torpedo

Human torpedoes or manned torpedoes are a type of diver propulsion vehicle on which the diver rides, generally in a seated position behind a fairing. They were used as secret naval weapons in World War II. The basic concept is still in use.

...

es, attacked the British fleet in Alexandria harbor.

* 1944: American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

UDT and British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

COPP frogmen

A frogman is someone who is trained in scuba diving or swimming underwater in a tactical capacity that includes military, and in some European countries, police work. Such personnel are also known by the more formal names of combat diver, comb ...

(COPP: Combined Operations Pilotage Parties

Combined Operations Headquarters was a department of the British War Office set up during Second World War to harass the Germans on the European continent by means of raids carried out by use of combined naval and army forces.

History

The comm ...

) used the "Churchill fins" during all prior underwater demining

Demining or mine clearance is the process of removing land mines from an area. In military operations, the object is to rapidly clear a path through a minefield, and this is often done with devices such as mine plows and blast waves. By cont ...

s, allowing this way in 1944 the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

. During years after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

had ended, De Corlieu spent time and efforts struggling with civil procedure

Civil procedure is the body of law that sets out the rules and standards that courts follow when adjudicating civil lawsuits (as opposed to procedures in criminal law matters). These rules govern how a lawsuit or case may be commenced; what kin ...

s for patent infringement.

The demand regulator reappears

* 1934: René Commeinhes, fromAlsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

, invented a breathing set working with a demand valve and designed to allow firefighters to breathe safely in smoke-filled environments.

* 1937: Georges Commeinhes Georges may refer to:

Places

*Georges River, New South Wales, Australia

*Georges Quay (Dublin)

*Georges Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Other uses

*Georges (name)

* ''Georges'' (novel), a novel by Alexandre Dumas

* "Georges" (song), a 1977 ...

, son of René, adapted his father's invention to diving and developed a two-cylinder open-circuit apparatus with demand regulator. The regulator was a big rectangular box between the cylinders. Some were made, but WWII

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

interrupted development.

World War II

* 1939:Georges Commeinhes Georges may refer to:

Places

*Georges River, New South Wales, Australia

*Georges Quay (Dublin)

*Georges Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Other uses

*Georges (name)

* ''Georges'' (novel), a novel by Alexandre Dumas

* "Georges" (song), a 1977 ...

offered his breathing set to the French Navy, which could not continue developing uses for it because of WWII

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

* 1940-1944: Christian J. Lambertsen of the United States designed a rebreather

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's breathing, exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. ...

'Breathing apparatus' for the U.S. military.

* 1942: Georges Commeinhes patented a better version of his scuba set, now called the GC42 ("G" for Georges, "C" for Commeinhes and "42" for 1942). Some are made by the Commeinhes' company.

* 1942: with no relation with the Commeinhes family, Émile Gagnan

Émile Gagnan (1900 – 1984) was a French engineer and, in 1943, co-inventor with French Navy diver Jacques-Yves Cousteau of the Aqua-Lung, the diving regulator (a.k.a. demand-valve) used for the first Scuba equipment. The demand-valve, or re ...

, an engineer employed by the Air Liquide

Air Liquide S.A. (; ; literally "liquid air"), is a French multinational company which supplies industrial gases and services to various industries including medical, chemical and electronic manufacturers. Founded in 1902, after Linde it is ...

company, obtained a Rouquayrol-Denayrouze apparatus (property of the Bernard Piel company in 1942) in Paris. He miniaturized and adapted it to gas generator

A gas generator is a device for generating gas. A gas generator may create gas by a chemical reaction or from a solid or liquid source, when storing a pressurized gas is undesirable or impractical.

The term often refers to a device that uses a ...

s, since the Germans occupy France and confiscated the French fuel for war purposes. Gagnan's boss and owner of the Air Liquide company, Henri Melchior, decided to introduce Gagnan to Jacques-Yves Cousteau

Jacques-Yves Cousteau, (, also , ; 11 June 191025 June 1997) was a French naval officer, oceanographer, filmmaker and author. He co-invented the first successful Aqua-Lung, open-circuit SCUBA ( self-contained underwater breathing apparatus). T ...

, his son-in-law

Son-in-Law (22 April 1911 – 15 May 1941) was a British Thoroughbred racehorse and an influential sire, especially for sport horses.

The National Horseracing Museum says Son-in-Law is "probably the best and most distinguished stayer this co ...

, because he knows that Cousteau is looking for an efficient and automatic demand regulator. They met in Paris in December 1942 and adapted Gagnan's regulator to a diving cylinder.

* 1943: after fixing some technical problems, Cousteau and Gagnan patented the first modern demand regulator.

** Air Liquide built two more aqualungs: these three are owned by Cousteau but also at the disposal of his first two diving companions Frédéric Dumas

Frédéric Dumas (14 January 1913 – 26 July 1991) was a French writer. He was part of a team of three, with Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Philippe Tailliez, who had a passion for diving, and developed the diving regulator with the aid of the enginee ...

and Taillez. They use them to shoot the film ''Épaves'' (''Shipwrecks''), the first underwater film shot using scuba sets.

** In July Commeinhes reached 53 metres (about 174 feet) using his GC42 breathing set off the coast of Marseille.

** In October, and not knowing about Commeinhes's exploit, Dumas dived with a Cousteau-Gagnan prototype and reached 62 metres (about 200 feet) off Les Goudes, not far from Marseille. He experienced what is now called nitrogen narcosis

Narcosis while diving (also known as nitrogen narcosis, inert gas narcosis, raptures of the deep, Martini effect) is a reversible alteration in consciousness that occurs while diving at depth. It is caused by the anesthetic effect of certain g ...

.

* 1944: Commeinhes died in the liberation of Strasbourg in Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

. His invention was overtaken by Cousteau's invention.

* Various nations use frogmen

A frogman is someone who is trained in scuba diving or swimming underwater in a tactical capacity that includes military, and in some European countries, police work. Such personnel are also known by the more formal names of combat diver, comb ...

equipped with rebreather

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's breathing, exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. ...

s for war actions: see Human torpedo.

* Hans Hass

Hans Hass (23 January 1919 – 16 June 2013) was an Austrian biologist and underwater diving pioneer. He was known mainly for being among the first scientists to popularise coral reefs, stingrays, octopuses and sharks. He pioneered the making o ...

later said that during WWII

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

the German diving gear firm Dräger offered him an open-circuit scuba set

A scuba set, originally just scuba, is any breathing apparatus that is entirely carried by an underwater diver and provides the diver with breathing gas at the ambient pressure. ''Scuba'' is an anacronym for self-contained underwater breathin ...

with a demand regulator. It may have been a separate invention, or it may have been copied from a captured Commeinhes-type set.