Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Theodore Roosevelt III ( ), often known as Theodore Jr.Morris, Edmund (1979). ''The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt''. index.While it was President

Ted was the eldest son of President

Ted was the eldest son of President  Like all the Roosevelt children, Ted was tremendously influenced by his father. In later life, Ted recorded some of these childhood recollections in a series of newspaper articles written around the time of

Like all the Roosevelt children, Ted was tremendously influenced by his father. In later life, Ted recorded some of these childhood recollections in a series of newspaper articles written around the time of  In one article, Ted recalled his first time in Washington, "...when father was civil service commissioner I often walked to the office with him. On the way down he would talk history to me—not the dry history of dates and charters, but the history where you yourself in your imagination could assume the role of the principal actors, as every well-constructed boy wishes to do when interested. During every battle we would stop and father would draw out the full plan in the dust in the gutter with the tip of his umbrella. Long before the European war had broken over the world father would discuss with us military training and the necessity for every man being able to take his part."

In one article, Ted recalled his first time in Washington, "...when father was civil service commissioner I often walked to the office with him. On the way down he would talk history to me—not the dry history of dates and charters, but the history where you yourself in your imagination could assume the role of the principal actors, as every well-constructed boy wishes to do when interested. During every battle we would stop and father would draw out the full plan in the dust in the gutter with the tip of his umbrella. Long before the European war had broken over the world father would discuss with us military training and the necessity for every man being able to take his part."

This summer training program provided the base of a greatly expanded junior officers' corps when the United States entered World War I. During that summer, many well-heeled young men from some of the finest east coast schools, including three of the four Roosevelt sons, attended the military camp. When the United States entered the war, in April 1917, the armed forces offered commissions to the graduates of these schools based on their performance. The

This summer training program provided the base of a greatly expanded junior officers' corps when the United States entered World War I. During that summer, many well-heeled young men from some of the finest east coast schools, including three of the four Roosevelt sons, attended the military camp. When the United States entered the war, in April 1917, the armed forces offered commissions to the graduates of these schools based on their performance. The  After the United States declaration of war on Germany, when the

After the United States declaration of war on Germany, when the

After service in World War I, Roosevelt began his political career. Grinning like his father, waving a crumpled hat, and like his father, shouting "bully", he participated in every national campaign that he could, except when he was

After service in World War I, Roosevelt began his political career. Grinning like his father, waving a crumpled hat, and like his father, shouting "bully", he participated in every national campaign that he could, except when he was  At the 1924 New York state election, Roosevelt was the Republican nominee for Governor of New York. His cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) spoke out on Ted's "wretched record" as Assistant Secretary of the Navy during the oil scandals. In return, Ted said of FDR: "He's a maverick! He does not wear the brand of our family."

At the 1924 New York state election, Roosevelt was the Republican nominee for Governor of New York. His cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) spoke out on Ted's "wretched record" as Assistant Secretary of the Navy during the oil scandals. In return, Ted said of FDR: "He's a maverick! He does not wear the brand of our family."

Truman R. Clark. 1975. University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 139–142, Retrieved 19 December 2012. In 1931 he appointed Carlos E. Chardón, a mycologist, as the first Puerto Rican to be Chancellor of the

During the 1932 presidential campaign of his cousin FDR, Roosevelt said, "Franklin is such poor stuff it seems improbable that he should be elected President." When Franklin won the election and Ted was asked just how he was related to FDR, Ted quipped "fifth cousin, about to be removed."

In 1935, he returned to the United States and first became a vice president of the publishing house Doubleday, Doran & Company. He next served as an executive with American Express. He also served on the boards of numerous non-profit organizations. He was invited by

During the 1932 presidential campaign of his cousin FDR, Roosevelt said, "Franklin is such poor stuff it seems improbable that he should be elected President." When Franklin won the election and Ted was asked just how he was related to FDR, Ted quipped "fifth cousin, about to be removed."

In 1935, he returned to the United States and first became a vice president of the publishing house Doubleday, Doran & Company. He next served as an executive with American Express. He also served on the boards of numerous non-profit organizations. He was invited by

Roosevelt collaborated with and was a friend of his commander, the hard-fighting, hard-drinking Major General

Roosevelt collaborated with and was a friend of his commander, the hard-fighting, hard-drinking Major General  Roosevelt was also criticized by Lieutenant General

Roosevelt was also criticized by Lieutenant General

File:teds grave.jpg, Theodore Roosevelt Jr.'s grave marker at the American World War II cemetery in Normandy. He lies buried next to his brother, Quentin, who was killed during World War I.

File:Quentin Roosevelt headstone.jpg, Quentin Roosevelt's grave at Normandy Cemetery.

File:Gen. Omar Bradley attends the funeral of Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr.jpg, General officers including Omar Bradley and Gen. J. Lawton Collins (with goggles) attending Roosevelt's funeral. George Patton is partially visible behind Collins.

Roosevelt was originally recommended for the

Roosevelt was originally recommended for the

Generals of World War II

{{DEFAULTSORT:Roosevelt, Theodore, Jr. 1887 births 1944 deaths 20th-century American politicians American Express people American veterans' rights activists United States Army personnel of World War I American people of Dutch descent American people of English descent American people of French descent American people of Scottish descent American people of Welsh descent Bulloch family Burials in Normandy Candidates in the 1936 United States presidential election Children of presidents of the United States Children of vice presidents of the United States Governors of Puerto Rico Governors-General of the Philippine Islands Groton School alumni Harvard College alumni Republican Party members of the New York State Assembly Members of the Philadelphia Club Military personnel from New York (state) Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Organization founders People from Oyster Bay (town), New York Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Silver Star Republican Party (Puerto Rico) politicians

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

who was legally named Theodore Roosevelt Jr., the President's fame made it simpler to call his son "Junior".(September 13, 1887 – July 12, 1944) was an American government, business, and military leader. He was the eldest son of President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and First Lady Edith Roosevelt

Edith Kermit Roosevelt ( née Carow; August 6, 1861 – September 30, 1948) was the second wife of President Theodore Roosevelt and the First Lady of the United States from 1901 to 1909. She also was the Second Lady of the United States in 1901 ...

. Roosevelt is known for his World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

service, including the directing of troops at Utah Beach

Utah, commonly known as Utah Beach, was the code name for one of the five sectors of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944 (D-Day), during World War II. The westernmost of the five code-named la ...

during the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

, for which he received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

.

Roosevelt was educated at private academies and Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

; after his 1909 graduation from college, he began a successful career in business and investment banking. Having gained pre-World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

army experience during his attendance at a Citizens' Military Training Camp, at the start of the war he received a reserve commission as a major. He served primarily with the 1st Division, took part in several engagements including the Battle of Cantigny

The Battle of Cantigny, fought May 28, 1918 was the first major American battle and offensive of World War I. The U.S. 1st Division, the most experienced of the five American divisions then in France and in reserve for the French Army near the v ...

, and commanded the 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry as a lieutenant colonel. After the war, Roosevelt was instrumental in the forming of The American Legion

The American Legion, commonly known as the Legion, is a non-profit organization of U.S. war veterans headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. It is made up of state, U.S. territory, and overseas departments, and these are in turn made up of l ...

.

In addition to his military and business careers, Roosevelt was active in politics and government. He served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy

Assistant Secretary of the Navy (ASN) is the title given to certain civilian senior officials in the United States Department of the Navy.

From 1861 to 1954, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy was the second-highest civilian office in the Depar ...

(1921–1924), Governor of Puerto Rico (1929–1932), and Governor-General of the Philippines

The Governor-General of the Philippines (Spanish: ''Gobernador y Capitán General de Filipinas''; Filipino: ''Gobernador-Heneral ng Pilipinas/Kapitan Heneral ng Pilipinas''; Japanese: ) was the title of the government executive during the colo ...

(1932–1933). He resumed his business endeavors in the 1930s, and was Chairman of the Board of American Express Company, and vice-president of Doubleday Books

Doubleday is an American publishing company. It was founded as the Doubleday & McClure Company in 1897 and was the largest in the United States by 1947. It published the work of mostly U.S. authors under a number of imprints and distributed th ...

. Roosevelt also remained active as an Army reservist, attending annual training periods at Pine Camp

Fort Drum is a U.S. Army military reservation and a census-designated place (CDP) in Jefferson County, on the northern border of New York, United States. The population of the CDP portion of the base was 12,955 at the 2010 census. It is home t ...

, and completing the Infantry Officer Basic and Advanced Courses, the Command and General Staff College, and refresher training for senior officers. He returned to active duty for World War II with the rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

, and commanded the 26th Infantry. He soon received promotion to brigadier general as assistant division commander of the 1st Infantry Division.

After serving in the Operation Torch landings in North Africa and the Tunisia Campaign

The Tunisian campaign (also known as the Battle of Tunisia) was a series of battles that took place in Tunisia during the North African campaign of the Second World War, between Axis and Allied forces from 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. Th ...

, followed by participation in the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers ( Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It b ...

, Roosevelt was assigned as assistant division commander of the 4th Infantry Division. In this role, he led the first wave of troops ashore at Utah Beach

Utah, commonly known as Utah Beach, was the code name for one of the five sectors of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944 (D-Day), during World War II. The westernmost of the five code-named la ...

during the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

in June 1944. He died in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

of a heart attack the following month; at the time of his death, he had been recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is a military decoration awarded to ...

to recognize his heroism at Normandy. The recommendation was subsequently upgraded, and Roosevelt was a posthumous recipient of the Medal of Honor.

Childhood

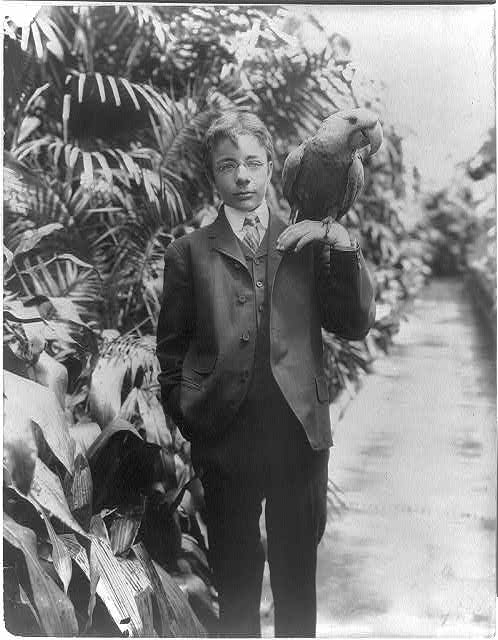

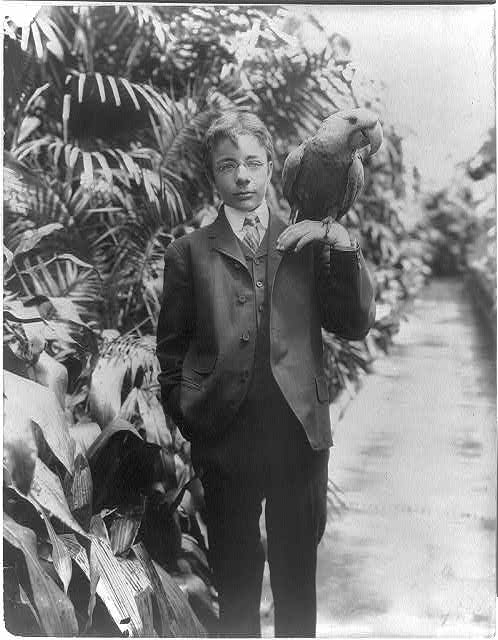

Ted was the eldest son of President

Ted was the eldest son of President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and First Lady Edith Kermit Carow. He was born at the family estate in Cove Neck

Cove Neck is a village located within the Town of Oyster Bay in Nassau County, on the North Shore of Long Island, in New York. The population was 286 at the 2010 census.

History

Cove Neck incorporated as a village in 1927.

Cove Neck is the s ...

, Oyster Bay, New York

The Town of Oyster Bay is the easternmost of the three towns which make up Nassau County, New York, United States. Part of the New York metropolitan area, it is the only town in Nassau County to extend from the North Shore to the South Shore ...

, when his father was just starting his political career. As a son of President Theodore Roosevelt, he has been referred to as "Jr", but he was actually Theodore III and one of his own sons was Theodore IV. His siblings were brothers Kermit, Archie, and Quentin

Quentin is a French male given name from the Latin first name ''Quintinus'', diminutive form of '' Quintus'', that means "the fifth".Albert Dauzat, ''Noms et prénoms de France'', Librairie Larousse 1980, édition revue et commentée par Marie-T ...

; sister Ethel

Ethel (also '' æthel'') is an Old English word meaning "noble", today often used as a feminine given name.

Etymology and historic usage

The word means ''æthel'' "noble".

It is frequently attested as the first element in Anglo-Saxon names, b ...

; and half-sister Alice. As an Oyster Bay Roosevelt, and through his ancestor Cornelius Van Schaack Jr., Ted was a descendant of the Schuyler family.

Like all the Roosevelt children, Ted was tremendously influenced by his father. In later life, Ted recorded some of these childhood recollections in a series of newspaper articles written around the time of

Like all the Roosevelt children, Ted was tremendously influenced by his father. In later life, Ted recorded some of these childhood recollections in a series of newspaper articles written around the time of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. One day when he was about nine, his father gave him a rifle. When Ted asked if it was real, his father loaded it and shot a bullet into the ceiling.

When Ted was a child, his father initially expected more of him than of his siblings. The burden almost caused him to suffer a nervous breakdown.

In one article, Ted recalled his first time in Washington, "...when father was civil service commissioner I often walked to the office with him. On the way down he would talk history to me—not the dry history of dates and charters, but the history where you yourself in your imagination could assume the role of the principal actors, as every well-constructed boy wishes to do when interested. During every battle we would stop and father would draw out the full plan in the dust in the gutter with the tip of his umbrella. Long before the European war had broken over the world father would discuss with us military training and the necessity for every man being able to take his part."

In one article, Ted recalled his first time in Washington, "...when father was civil service commissioner I often walked to the office with him. On the way down he would talk history to me—not the dry history of dates and charters, but the history where you yourself in your imagination could assume the role of the principal actors, as every well-constructed boy wishes to do when interested. During every battle we would stop and father would draw out the full plan in the dust in the gutter with the tip of his umbrella. Long before the European war had broken over the world father would discuss with us military training and the necessity for every man being able to take his part."

Education and early business career

The Roosevelt boys attended private schools; Ted went toThe Albany Academy

The Albany Academy is an independent college preparatory day school for boys in Albany, New York, USA, enrolling students from Preschool (age 3) to Grade 12. It was established in 1813 by a charter signed by Mayor Philip Schuyler Van Renssela ...

, and then Groton School. Before he went to college, he thought about going to military school. Although not naturally called to academics, he persisted and graduated from Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

in 1909, where, like his father, he joined the Porcellian Club

The Porcellian Club is an all-male final club at Harvard University, sometimes called the Porc or the P.C. The year of founding is usually given as 1791, when a group began meeting under the name "the Argonauts",, p. 171: source for 1791 origins ...

.

After graduating from college, Ted entered the business world. He took positions in the steel and carpet businesses before becoming branch manager of an investment bank. He had a flair for business and amassed a considerable fortune in the years leading up to World War I and on into the 1920s. The income generated by his investments positioned him well for a career in politics after the War.

World War I

All the Roosevelt sons, except Kermit, had some military training prior to World War I. With the outbreak of World War I in Europe in August 1914, American leaders had heightened concern about their nation's readiness for military engagement. Only the month before, Congress had authorized the creation of an Aviation Section in the Signal Corps. In 1915,Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Leonard Wood

Leonard Wood (October 9, 1860 – August 7, 1927) was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Military Governor of Cuba, and Governor-General of the Philipp ...

, President Roosevelt's former commanding officer during the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

, organized a summer camp at Plattsburgh, New York, to provide military training for business and professional men, at their own expense.

This summer training program provided the base of a greatly expanded junior officers' corps when the United States entered World War I. During that summer, many well-heeled young men from some of the finest east coast schools, including three of the four Roosevelt sons, attended the military camp. When the United States entered the war, in April 1917, the armed forces offered commissions to the graduates of these schools based on their performance. The

This summer training program provided the base of a greatly expanded junior officers' corps when the United States entered World War I. During that summer, many well-heeled young men from some of the finest east coast schools, including three of the four Roosevelt sons, attended the military camp. When the United States entered the war, in April 1917, the armed forces offered commissions to the graduates of these schools based on their performance. The National Defense Act of 1916

The National Defense Act of 1916, , was a United States federal law that updated the Militia Act of 1903, which related to the organization of the military, particularly the National Guard. The principal change of the act was to supersede prov ...

continued the student military training and the businessmen's summer camps. It placed them on a firmer legal basis by authorizing an Officers' Reserve Corps and a Reserve Officers' Training Corps

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC ( or )) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

Overview

While ROTC graduate officers serve in al ...

(ROTC).

After the United States declaration of war on Germany, when the

After the United States declaration of war on Germany, when the American Expeditionary Forces

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought along ...

(AEF) was organizing, Theodore Roosevelt wired Major General John "Black Jack" Pershing, the newly appointed commander of the AEF, asking if his sons could accompany him to Europe as privates. Pershing accepted, but, based on their training at Plattsburgh

Plattsburgh ( moh, Tsi ietsénhtha) is a city in, and the seat of, Clinton County, New York, United States, situated on the north-western shore of Lake Champlain. The population was 19,841 at the 2020 census. The population of the surrounding ...

, Archie was offered a commission with rank of second lieutenant, while Ted was offered a commission and the rank of major. Quentin had already been accepted into the Army Air Service

The United States Army Air Service (USAAS)Craven and Cate Vol. 1, p. 9 (also known as the ''"Air Service"'', ''"U.S. Air Service"'' and before its legislative establishment in 1920, the ''"Air Service, United States Army"'') was the aerial warf ...

. Kermit volunteered with the British in the area of present-day Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

.

With a reserve commission in the army (like Quentin and Archibald), soon after World War I started, Ted was called up. When the United States declared war on the German Empire, Ted volunteered to be one of the first soldiers to go to the Western Front. There, he was recognized as the best battalion commander in his division, according to the division commander. Roosevelt braved hostile fire and gas and led his battalion in combat. So concerned was he for his men's welfare that he purchased combat boots

Combat boots are military boots designed to be worn by soldiers during combat or combat training, as opposed to during parades and other ceremonial duties. Modern combat boots are designed to provide a combination of grip, ankle stability, an ...

for the entire battalion with his own money. He eventually commanded the 26th Regiment in the 1st Division as a lieutenant colonel. He fought in several major battles, including America's first victory at the Battle of Cantigny

The Battle of Cantigny, fought May 28, 1918 was the first major American battle and offensive of World War I. The U.S. 1st Division, the most experienced of the five American divisions then in France and in reserve for the French Army near the v ...

.

Ted was gassed and wounded at Soissons

Soissons () is a commune in the northern French department of Aisne, in the region of Hauts-de-France. Located on the river Aisne, about northeast of Paris, it is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital o ...

during the summer of 1918. In July of that year, his youngest brother Quentin was killed in combat. Ted received the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is a military decoration awarded to ...

for his actions during the war, which ended on November 11, 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

at 11:00 am. France conferred upon him the Chevalier Légion d'honneur on March 16, 1919. Before the troops came home from France, Ted was one of the founders of the soldiers' organization that developed as The American Legion. The American Legion ''Post Officers Guide'' recounts Ted's part in the organization's founding:

When the American Legion met in New York City, Roosevelt was nominated as its first national commander, but he declined, not wanting to be thought of as simply using it for political gain. In his view, acceptance under such circumstances could have discredited the nascent organization and himself and harmed his chances for a future in politics.

Ted resumed his reserve service between the wars. He attended the annual summer camps at Pine Camp

Fort Drum is a U.S. Army military reservation and a census-designated place (CDP) in Jefferson County, on the northern border of New York, United States. The population of the CDP portion of the base was 12,955 at the 2010 census. It is home t ...

and completed both the Infantry Officer's Basic and Advanced Courses, and the Command and General Staff College. By the beginning of World War II, in September 1939, he was eligible for senior commissioned service.

In 1919 he became a member of the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

The National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR or NSSAR) is an American congressionally chartered organization, founded in 1889 and headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky. A non-profit corporation, it has described its purpose ...

.

Political career

After service in World War I, Roosevelt began his political career. Grinning like his father, waving a crumpled hat, and like his father, shouting "bully", he participated in every national campaign that he could, except when he was

After service in World War I, Roosevelt began his political career. Grinning like his father, waving a crumpled hat, and like his father, shouting "bully", he participated in every national campaign that he could, except when he was Governor-General of the Philippines

The Governor-General of the Philippines (Spanish: ''Gobernador y Capitán General de Filipinas''; Filipino: ''Gobernador-Heneral ng Pilipinas/Kapitan Heneral ng Pilipinas''; Japanese: ) was the title of the government executive during the colo ...

. Elected as a member of the New York State Assembly (Nassau County, 2nd D.) in 1920 and 1921, Roosevelt was one of the few legislators who opposed the expulsion of five Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

assemblymen in 1920. Anxiety about Socialists was high at the time.

On March 10, 1921, Roosevelt was appointed by President Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

as Assistant Secretary of the Navy

Assistant Secretary of the Navy (ASN) is the title given to certain civilian senior officials in the United States Department of the Navy.

From 1861 to 1954, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy was the second-highest civilian office in the Depar ...

. He oversaw the transferring of oil leases for federal lands

Federal lands are lands in the United States owned by the federal government. Pursuant to the Property Clause of the United States Constitution ( Article 4, section 3, clause 2), Congress has the power to retain, buy, sell, and regulate federal l ...

in Wyoming and California from the Navy to the Department of Interior, and ultimately, to private corporations. Established as the Navy's petroleum reserves by President Taft, the properties consisted of three oil fields: Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3, Teapot Dome Field, Natrona County, Wyoming; and Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 1 at Elk Hills Oil Field

The Elk Hills Oil Field (formerly the Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 1) is a large oil field in western Kern County, in the Elk Hills of the San Joaquin Valley, California in the United States, about west of Bakersfield. Discovered in 1911, ...

and Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 2 Buena Vista Oil Field The Buena Vista Oil Field, formerly the Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 2 (NPR-2) is a large oil field in Kern County, San Joaquin Valley, California in the United States. Discovered in 1909, and having a cumulative production of approximately , it is ...

, both in Kern County, California

Kern County is a county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 909,235. Its county seat is Bakersfield.

Kern County comprises the Bakersfield, California, Metropolitan statistical area. The county s ...

. In 1922, Albert B. Fall

Albert Bacon Fall (November 26, 1861November 30, 1944) was a United States senator from New Mexico and the Secretary of the Interior under President Warren G. Harding, infamous for his involvement in the Teapot Dome scandal; he was the only pers ...

, U.S. Secretary of the Interior, leased the Teapot Dome Field to Harry F. Sinclair of Sinclair Consolidated Oil Company, and the field at Elk Hills, California, to Edward L. Doheny

Edward Laurence Doheny (; August 10, 1856 – September 8, 1935) was an American oil tycoon who, in 1892, drilled the first successful oil well in the Los Angeles City Oil Field. His success set off a petroleum boom in Southern California, a ...

of Pan American Petroleum & Transport Company, both without competitive bidding.

During the transfers, while Roosevelt was Assistant Secretary of the Navy, his brother Archie was vice president of the Union Petroleum Company, the export auxiliary subsidiary of the Sinclair Consolidated Oil. The leasing of government reserves without competitive bidding, plus the close personal and business relationships among the players, led to the deal being called the Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a bribery scandal involving the administration of United States President Warren G. Harding from 1921 to 1923. Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyomi ...

. The connection between the Roosevelt brothers could not be ignored.

After Sinclair sailed for Europe to avoid testifying in Congressional hearings, G. D. Wahlberg, Sinclair's private secretary, advised Archibald Roosevelt to resign to save his reputation. The Senate Committee on Public Lands held hearings over a period of six months to investigate the actions of Fall in leasing the public lands without the required competitive bidding. Although both Archibald and Ted Roosevelt were cleared of all charges by the Senate Committee on Public Lands, their images were tarnished.

At the 1924 New York state election, Roosevelt was the Republican nominee for Governor of New York. His cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) spoke out on Ted's "wretched record" as Assistant Secretary of the Navy during the oil scandals. In return, Ted said of FDR: "He's a maverick! He does not wear the brand of our family."

At the 1924 New York state election, Roosevelt was the Republican nominee for Governor of New York. His cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) spoke out on Ted's "wretched record" as Assistant Secretary of the Navy during the oil scandals. In return, Ted said of FDR: "He's a maverick! He does not wear the brand of our family." Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

, more closely related to Ted by blood but married to FDR, had been infuriated by these remarks. She dogged Ted on the New York State campaign trail in a car fitted with a ''papier-mâché

upright=1.3, Mardi Gras papier-mâché masks, Haiti

upright=1.3, Papier-mâché Catrinas, traditional figures for day of the dead celebrations in Mexico

Papier-mâché (, ; , literally "chewed paper") is a composite material consisting of p ...

'' bonnet shaped like a giant teapot that was made to emit simulated steam, and countered his speeches with those of her own, calling him immature.

She would later decry these methods, admitting that they were below her dignity but saying that they had been contrived by Democratic Party "dirty tricksters." Ted's opponent, incumbent governor Alfred E. Smith, defeated him by 105,000 votes. Ted never forgave Eleanor for her stunt, though his elder half-sister Alice did, and resumed their formerly close friendship. These conflicts served to widen the split between the Oyster Bay (TR) and Hyde Park (FDR) wings of the Roosevelt family.

Governor of Puerto Rico

Along with his brother, Kermit, Roosevelt spent most of 1929 on a zoological expedition and was the first Westerner known to have shot a panda. In September 1929, PresidentHerbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

appointed Roosevelt as Governor of Puerto Rico, and he served until 1932. (Until 1947, when it became an electoral office, this was a political appointee position.) Roosevelt worked to ease the poverty of the people during the Great Depression. He attracted money to build secondary schools, raised money from American philanthropists, marketed Puerto Rico as a location for manufacturing, and made other efforts to improve the Puerto Rican economy.

He worked to create more ties to U.S. institutions for mutual benefit. For instance, he arranged for Cayetano Coll y Cuchi to be invited to Harvard Law School to lecture about Puerto Rico's legal system. He arranged for Antonio Reyes Delgado of the Puerto Rican Legislative Assembly

The Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico ( es, Asamblea Legislativa de Puerto Rico) is the state legislature (United States), territorial legislature of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, responsible for the legislative branch of the government of ...

to speak to a conference of Civil Service Commissioners in New York City. Roosevelt worked to educate Americans about the island and its people, and to promote the image of Puerto Rico in the rest of the U.S.

Roosevelt was the first American governor to study Spanish and tried to learn 20 words a day. He was fond of local Puerto Rican culture

The culture of Puerto Rico is the result of a number of international and indigenous influences, both past and present. Modern cultural manifestations showcase the island's rich history and help to create an identity which is uniquely Puerto Rica ...

and assumed many of the island's traditions. He became known as ''El Jíbaro Jivaro or Jibaro, also spelled Hivaro or Hibaro, may refer to:

* Jíbaro (Puerto Rico), mountain-dwelling peasants in Puerto Rico

* Jíbaro music, a Puerto Rican musical genre

* Jivaroan peoples

The Jivaroan peoples are the indigenous peoples ...

de La Fortaleza

La Fortaleza (lit., "The Fortress" ) is the official residence of the governor of Puerto Rico. It was built between 1533 and 1540 to defend the harbor of San Juan. The structure is also known as Palacio de Santa Catalina (Saint Catherine's Palac ...

'' ("The Hillbilly of the Governor's Mansion") by locals.''Puerto Rico and the United States, 1917–1933.''Truman R. Clark. 1975. University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 139–142, Retrieved 19 December 2012. In 1931 he appointed Carlos E. Chardón, a mycologist, as the first Puerto Rican to be Chancellor of the

University of Puerto Rico

The University of Puerto Rico ( es, Universidad de Puerto Rico, UPR) is the main public university system in the U.S. Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. It is a government-owned corporation with 11 campuses and approximately 58,000 students and 5,3 ...

.

Governor-General of the Philippines

Impressed with his work in Puerto Rico, President Hoover appointed Roosevelt asGovernor-General of the Philippines

The Governor-General of the Philippines (Spanish: ''Gobernador y Capitán General de Filipinas''; Filipino: ''Gobernador-Heneral ng Pilipinas/Kapitan Heneral ng Pilipinas''; Japanese: ) was the title of the government executive during the colo ...

in 1932. During his time in office, Roosevelt acquired the nickname "One Shot Teddy" among the Filipino population, in reference to his marksmanship during a hunt for tamaraw

The tamaraw or Mindoro dwarf buffalo (''Bubalus mindorensis'') is a small hoofed mammal belonging to the family Bovidae. It is endemic to the island of Mindoro in the Philippines, and is the only endemic Philippine bovine. It is believed, howe ...

(wild pygmy water buffalo).

In the 1932 United States presidential election

The 1932 United States presidential election was the 37th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 8, 1932. The election took place against the backdrop of the Great Depression. Incumbent Republican President Herbert Hoover w ...

, when Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

challenged Hoover for the presidency, Alice begged Ted to return from the Philippines to aid the campaign. Roosevelt announced to the press on August 22, 1932, that "Circumstances have made it necessary for me to return for a brief period to the United States..... I shall start for the Philippines again the first week in November..... While there I hope I can accomplish something."

The reaction of many in the U.S. press was so negative that within a few weeks, Governor-General Roosevelt arranged to stay in Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

throughout the campaign. U.S. Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of th ...

Patrick J. Hurley cabled Ted, "The President has reached the conclusion that you should not leave your duties for the purpose of participating in the campaign.... He believes it to be your duty to remain at your post." Roosevelt resigned as Governor-General after the election of FDR as president, as the new administration would appoint their own people. He thought that the potential for war in Europe meant another kind of opportunity for him. Using his father's language, he wrote to his wife as he sailed for North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, saying that he had done his best and his fate was now "at the knees of the gods."

Return to the U.S. mainland

Irving Berlin

Irving Berlin (born Israel Beilin; yi, ישראל ביילין; May 11, 1888 – September 22, 1989) was a Russian-American composer, songwriter and lyricist. His music forms a large part of the Great American Songbook.

Born in Imperial Russ ...

to help oversee the disbursement of royalties for Berlin's popular song, "God Bless America

"God Bless America" is an American patriotic song written by Irving Berlin during World War I in 1918 and revised by him in the run up to World War II in 1938. The later version was notably recorded by Kate Smith, becoming her signature son ...

," to charity. While living again in New York, the Roosevelts renewed old friendships with playwright Alexander Woollcott

Alexander Humphreys Woollcott (January 19, 1887 – January 23, 1943) was an American drama critic and commentator for ''The New Yorker'' magazine, a member of the Algonquin Round Table, an occasional actor and playwright, and a prominent radio ...

and comedian Harpo Marx

Arthur "Harpo" Marx (born Adolph Marx; November 23, 1888 – September 28, 1964) was an American comedian, actor, mime artist, and harpist, and the second-oldest of the Marx Brothers. In contrast to the mainly verbal comedy of his brothers Grou ...

.

He was also mentioned as a potential candidate for the 1936 Republican presidential nomination, but did not mount a campaign. Had he received the 1936 Republican presidential nomination, he would have faced off against his cousin Franklin in the general election. After Alf Landon

Alfred Mossman Landon (September 9, 1887October 12, 1987) was an American oilman and politician who served as the 26th governor of Kansas from 1933 to 1937. A member of the Republican Party, he was the party's nominee in the 1936 presidential el ...

received the Republican presidential nomination, Roosevelt was also mentioned as a candidate for vice president, but that nomination went to Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, newspaper editor and publisher. He was also the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936, and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt durin ...

. Roosevelt was also mentioned as a candidate for Governor of New York in 1936, but made no effort to become an active candidate.

World War II service and death

In 1940, during World War II (although the United States had not yet entered the war and remained neutral) Roosevelt attended a military refresher course offered to many businessmen as an advanced student, and was promoted to colonel in theArmy of the United States

The Army of the United States is one of the four major service components of the United States Army (the others being the Regular Army, the United States Army Reserve and the Army National Guard of the United States), but it has been inactive si ...

.

Roosevelt's wife personally asked Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

to return him to a combat unit despite his past hospitalization. Although Marshall typically refused such political favoritism he remarked that he would make an exception "if what you wanted was a more dangerous job than what you had" and agreed. Roosevelt returned to active duty in April 1941 and was given command of the 26th Infantry Regiment

The 26th Infantry Regiment is an infantry regiment of the United States Army. Its nickname is "Blue Spaders", taken from the spade-like device on the regiment's distinctive unit insignia. The 26th Infantry Regiment is part of the U.S. Army Re ...

, part of the 1st Infantry Division, the same unit he fought with in World War I. Late in 1941, he was promoted to the one-star general officer rank of brigadier general.

North Africa

Upon his arrival inNorth Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, Roosevelt became known as a general who often visited the front lines. He had always preferred the heat of the battle to the comfort of the command post, and this attitude would culminate in his actions in France on D-Day.

Roosevelt led the 26th Infantry in an attack on Oran, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, on November 8, 1942, as part of Operation Torch, the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

' invasion of North Africa. During 1943, he was the Assistant Division Commander (ADC) of the 1st Infantry Division in the campaign in North Africa under Major General Terry Allen. He was cited for the Croix de Guerre by the military commander of French Africa

French Africa includes all the historic holdings of France on the African continent.

Françafrique

French North Africa

* Egypt (1798-1801)

* French Algeria (1830–1962)

* Protectorate of Tunisia (1881–1956)

* Protectorate in Morocco (1 ...

, General Alphonse Juin

Alphonse Pierre Juin (16 December 1888 – 27 January 1967) was a senior French Army general who became Marshal of France. A graduate of the École Spéciale Militaire class of 1912, he served in Morocco in 1914 in command of native troops. Upon ...

:

Clashes with Patton

Roosevelt collaborated with and was a friend of his commander, the hard-fighting, hard-drinking Major General

Roosevelt collaborated with and was a friend of his commander, the hard-fighting, hard-drinking Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr.

Major general (United States), Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. (April 1, 1888 – September 12, 1969) was a senior United States Army Officer (armed forces), officer who fought in both World War I and World War II. Allen was a decorated W ...

Their unorthodox approach to warfare did not escape the attention of Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

, the Seventh Army commander in Sicily, and formerly the II Corps commander. Patton disapproved of such officers who "dressed down" and were seldom seen in regulation field uniforms, and who placed little value in Patton's spit-shined ways in the field. Patton thought them both un-soldierly for it and wasted no opportunity to send derogatory reports on Allen to General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, the Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO). Roosevelt was also treated by Patton as "guilty by association" for his friendship and collaboration with the highly unorthodox Allen. When Allen was relieved of command of the 1st Division and reassigned, so was Roosevelt.

After criticizing Allen in his diary on July 31, 1943, Patton noted that he had asked permission of Eisenhower "to relieve both Allen and Roosevelt on the same terms, on the theory of rotation of command", and added, concerning Roosevelt, "there will be a kick over Teddy, but he has to go, brave but otherwise, no soldier." Later, however, upon hearing of the death of Roosevelt, Patton wrote in his diary that Roosevelt was "one of the bravest men I've ever known", and a few days later served as a pallbearer

A pallbearer is one of several participants who help carry the casket at a funeral. They may wear white gloves in order to prevent damaging the casket and to show respect to the deceased person.

Some traditions distinguish between the roles o ...

at his funeral.

Roosevelt was also criticized by Lieutenant General

Roosevelt was also criticized by Lieutenant General Omar Bradley

Omar Nelson Bradley (February 12, 1893April 8, 1981) was a senior officer of the United States Army during and after World War II, rising to the rank of General of the Army. Bradley was the first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and over ...

, the II Corps commander, who ultimately relieved both Roosevelt and Allen. In both of his autobiographies – ''A Soldier's Story (1951)'' and ''A General's Life'' – Bradley claimed that relieving the two generals was one of his most unpleasant duties of the war. Bradley felt that Allen and Roosevelt were guilty of "loving their division too much" and that their relationship with their soldiers was having a generally bad effect on the discipline of both the commanders and the men of the division.

Roosevelt was assistant commander of the 1st Infantry Division at Gela

Gela (Sicilian and ; grc, Γέλα) is a city and (municipality) in the Autonomous Region of Sicily, Italy; in terms of area and population, it is the largest municipality on the southern coast of Sicily. Gela is part of the Province of Ca ...

during the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers ( Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It b ...

, codenamed Operation Husky, commanded Allied Forces in Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

, and fought on the Italian mainland. He was the chief liaison officer to the French Expeditionary Corps There have been several French Expeditionary Corps (French ''Corps expéditionnaire'' 'français'':

* Expeditionary Corps of the Orient 'Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient'', CEO(1915), during World War I

* Expeditionary Corps of the Dardanelles 'Co ...

in Italy for General Eisenhower, and repeatedly made requests of Eisenhower for combat command.

D-Day

In February 1944, Roosevelt was assigned toEngland

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

to help lead the Normandy invasion and appointed Deputy Division Commander of the 4th Infantry Division. After several verbal requests to the division's Commanding General

The commanding officer (CO) or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually given wide latitud ...

(CG), Major General Raymond "Tubby" Barton, to go ashore on D-Day with the Division were denied, Roosevelt sent a written petition:

Barton approved Roosevelt's written request with much misgiving, stating that he did not expect Roosevelt to return alive.

Roosevelt was the only general on D-Day to land by sea with the first wave of troops. At 56, he was the oldest man in the invasion, and the only one whose son also landed that day; Captain Quentin Roosevelt II

Quentin Roosevelt II (November 4, 1919 – December 21, 1948) was the fourth child and youngest son of Theodore "Ted" Roosevelt III and Eleanor Butler Alexander. He was the namesake of his uncle Quentin Roosevelt I, who was killed in acti ...

was among the first wave of soldiers at Omaha Beach.

Brigadier General Roosevelt was one of the first soldiers, along with Captain Leonard T. Schroeder Jr., off his landing craft as he led the 8th Infantry Regiment and 70th Tank Battalion

The 70th Armor Regiment is an armored (tank) unit of the United States Army. It was constituted as the 70th Tank Battalion in July 1940, an independent tank battalion intended to provide close support to infantry units. In this role, it saw acti ...

landing at Utah Beach

Utah, commonly known as Utah Beach, was the code name for one of the five sectors of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944 (D-Day), during World War II. The westernmost of the five code-named la ...

. Roosevelt was soon informed that the landing craft had drifted south of their objective, and the first wave of men was a mile off course. Walking with the aid of a cane and carrying a pistol, he personally made a reconnaissance of the area immediately to the rear of the beach to locate the causeways that were to be used for the advance inland. He returned to the point of landing and contacted the commanders of the two battalions, Lieutenant Colonels Conrad C. Simmons and Carlton O. MacNeely, and coordinated the attack on the enemy positions confronting them. Opting to fight from where they had landed rather than trying to move to their assigned positions, Roosevelt's famous words were, "We'll start the war from right here!"

These impromptu plans worked with complete success and little confusion. With artillery landing close by, each follow-on regiment was personally welcomed on the beach by a cool, calm, and collected Roosevelt, who inspired all with humor and confidence, reciting poetry and telling anecdotes of his father to steady the nerves of his men. Roosevelt pointed almost every regiment to its changed objective. Sometimes he worked under fire as a self-appointed traffic cop, untangling traffic jams of trucks and tanks all struggling to get inland and off the beach. One GI later reported that seeing the general walking around, apparently unaffected by the enemy fire, even when clods of earth fell down on him, gave him the courage to get on with the job, saying if the general is like that it cannot be that bad.

When Major General Barton, the commander of the 4th Infantry Division, came ashore, he met Roosevelt not far from the beach. He later wrote:

By modifying his division's original plan on the beach, Roosevelt enabled its troops to achieve their mission objectives by coming ashore and attacking north behind the beach toward its original objective. Years later, Omar Bradley was asked to name the single most heroic action he had ever seen in combat. He replied, "Ted Roosevelt on Utah Beach."

Following the landing, Roosevelt utilized a Jeep named "Rough Rider

The Rough Riders was a nickname given to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, one of three such regiments raised in 1898 for the Spanish–American War and the only one to see combat. The United States Army was small, understaffed, and diso ...

", which was the nickname of his father's regiment raised during the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

. Before his death, Roosevelt was appointed as Military Governor

A military government is generally any form of government that is administered by military forces, whether or not this government is legal under the laws of the jurisdiction at issue, and whether this government is formed by natives or by an occup ...

of Cherbourg.

Death

Throughout World War II, Roosevelt suffered from health problems. He had arthritis, mostly from old World War I injuries, and walked with a cane. He also had heart trouble, which he kept secret from army doctors and his superiors. On July 12, 1944, a little over one month after the landing atUtah Beach

Utah, commonly known as Utah Beach, was the code name for one of the five sectors of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944 (D-Day), during World War II. The westernmost of the five code-named la ...

, Roosevelt died of a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

in France. He was living at the time in a converted sleeping truck, captured a few days before from the Germans. He had spent part of the day in a long conversation with his son, Captain Quentin Roosevelt II

Quentin Roosevelt II (November 4, 1919 – December 21, 1948) was the fourth child and youngest son of Theodore "Ted" Roosevelt III and Eleanor Butler Alexander. He was the namesake of his uncle Quentin Roosevelt I, who was killed in acti ...

, who had also landed at Normandy on D-Day. He was stricken at about 10:00 pm, attended by medical help, and died at about midnight. He was fifty-six years old. On the day of his death, he had been selected by Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, now commanding the U.S. First Army

First Army is the oldest and longest-established field army of the United States Army. It served as a theater army, having seen service in both World War I and World War II, and supplied the US army with soldiers and equipment during the Kore ...

, for promotion to the two-star rank

An officer of two-star rank is a senior commander in many of the armed services holding a rank described by the NATO code of OF-7. The term is also used by some armed forces which are not NATO members. Typically, two-star officers hold the rank ...

of major general and command of the 90th Infantry Division 90th Division may refer to:

;Infantry

* 90th Division (1st Formation)(People's Republic of China), 1949–1950

* 90th Division (2nd Formation)(People's Republic of China), 1950–1952

* 90th Light Infantry Division (Wehrmacht)

* 90th Infantry Divi ...

. These recommendations were sent to General Eisenhower, now the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. Eisenhower approved the assignment, but Roosevelt died before the battlefield promotion.

Roosevelt was initially buried at Sainte-Mère-Église

Sainte-Mère-Église () is a commune in the northwestern French department of Manche, in Normandy. On 1 January 2016, the former communes of Beuzeville-au-Plain, Chef-du-Pont, Écoquenéauville and Foucarville were merged into Sainte-Mère-Ég ...

. Photographs show that his honorary pallbearer

A pallbearer is one of several participants who help carry the casket at a funeral. They may wear white gloves in order to prevent damaging the casket and to show respect to the deceased person.

Some traditions distinguish between the roles o ...

s were generals, including Omar N. Bradley, George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

, Raymond O. Barton, Clarence R. Huebner, Courtney Hicks Hodges, and J. Lawton Collins, the VII Corps 7th Corps, Seventh Corps, or VII Corps may refer to:

* VII Corps (Grande Armée), a corps of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VII Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army prior to and during World War I

* VII ...

commander. Later, Roosevelt was buried at the American cemetery in Normandy, initially created for the Americans killed in Normandy during the invasion. His younger brother, Second Lieutenant Quentin Roosevelt

Quentin Roosevelt I (November 19, 1897 – July 14, 1918) was the youngest son of President Theodore Roosevelt and First Lady Edith Roosevelt. Inspired by his father and siblings, he joined the United States Army Air Service where he became a pu ...

, had been killed in action as a pilot in France during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and was initially buried near where he had been shot down in that war. In 1955, his family had his body exhumed and moved to the Normandy cemetery, where he was re-interred beside his brother. Ted also has a cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty tomb or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although the vast majority of cenot ...

near the grave of his parents at Youngs Memorial Cemetery

Youngs Memorial Cemetery is a small cemetery in the village of Oyster Bay Cove, New York in the United States of America. It is located approximately one and a half miles south of Sagamore Hill National Historic Site. The cemetery was chartered ...

in Oyster Bay, while Quentin's original gravestone was moved to Sagamore Hill.

Medal of Honor

Roosevelt was originally recommended for the

Roosevelt was originally recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is a military decoration awarded to ...

by General Barton. The recommendation was upgraded at higher headquarters to the Medal of Honor, which was approved, and which Roosevelt was posthumously awarded on 21 September 1944.

Family

On June 20, 1910, Roosevelt married Eleanor Butler Alexander (1888–1960), daughter of Henry Addison Alexander and Grace Green. Ted and Eleanor had four children:Grace

Grace may refer to:

Places United States

* Grace, Idaho, a city

* Grace (CTA station), Chicago Transit Authority's Howard Line, Illinois

* Little Goose Creek (Kentucky), location of Grace post office

* Grace, Carroll County, Missouri, an uninco ...

(1911–1994), Theodore

Theodore may refer to:

Places

* Theodore, Alabama, United States

* Theodore, Australian Capital Territory

* Theodore, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Banana, Australia

* Theodore, Saskatchewan, Canada

* Theodore Reservoir, a lake in Sask ...

(1914–2001), Cornelius (1915–1991), and Quentin

Quentin is a French male given name from the Latin first name ''Quintinus'', diminutive form of '' Quintus'', that means "the fifth".Albert Dauzat, ''Noms et prénoms de France'', Librairie Larousse 1980, édition revue et commentée par Marie-T ...

(1919–1948).

Military awards

General Roosevelt's military awards include:Civilian honors

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. is honored in thescientific names

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

of two species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of Caribbean lizards: ''Anolis roosevelti

''Anolis roosevelti'', also known commonly as the Virgin Islands giant anole, Roosevelt's giant anole or the Culebra giant anole, is an extremely rare or possibly extinct species of lizard of the genus ''Anolis'' in the family Dactyloidae. The ...

'' and ''Sphaerodactylus roosevelti

''Sphaerodactylus roosevelti'', also known commonly as Roosevelt's beige sphaero or Roosevelt's least gecko, is a small species of lizard in the family Sphaerodactylidae. The species is endemic to Puerto Rico.

Etymology

The specific name, ''ro ...

''. Both species were named and described in 1931 by American herpetologist

Herpetology (from Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is the branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians ( gymnophiona)) and rep ...

Chapman Grant

Chapman Grant (March 27, 1887 – January 5, 1983) was an American herpetologist, historian, and publisher. He was the last living grandson of United States President Ulysses S. Grant.

He was married and had two children, one of whom survived him ...

, a grandson of U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

.Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). ''The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. . ("Roosevelt", p. 226).

Representation in other media

* Roosevelt's actions on D-Day are portrayed in '' The Longest Day'', a 1962 film in which he was played by actorHenry Fonda

Henry Jaynes Fonda (May 16, 1905 – August 12, 1982) was an American actor. He had a career that spanned five decades on Broadway and in Hollywood. He cultivated an everyman screen image in several films considered to be classics.

Born and ra ...

. The movie is based on the 1959 book of the same name by Cornelius Ryan

Cornelius Ryan (5 June 1920 – 23 November 1974) was an Irish-American journalist and author known mainly for writing popular military history. He was especially known for his histories of World War II events: '' The Longest Day: 6 June 1944 D- ...

.

* Roosevelt's life, political views, and actions are documented in the 2014 miniseries ''The Roosevelts'', directed by Ken Burns.

See also

*List of governors of Puerto Rico

:

This list of governors of Puerto Rico includes all persons who have held that post, either under Spanish or American rule. The governor of Puerto Rico is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. The position was first establ ...

* List of Medal of Honor recipients for World War II

* List of members of the American Legion

This table provides a list of notable members of The American Legion.

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

R

S

T

U

V

W

Y

Z

References

External links

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:American Legion, List O ...

Notes

References

Further reading

: * Atkinson, Rick (2003). ''An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942–1943''. Macmillan. * Baldwin, Hanson W. (July 14, 1944). "Theodore Roosevelt, 56, Dies on Normandy Battlefield; Succumbs to a Heart Attack Soon After Visit from Son". ''The New York Times''. * * Jeffers, H. Paul (2002). ''The Life of a War Hero''. * Roosevelt, Eleanor Butler (1959). ''Day Before Yesterday: The Reminiscences of Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.'' * Walker, Robert W. (2004). ''The Namesake: The Biography of Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.'' * Zumbaugh, David M. (2014). ''A Concise Biography of Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.''External links

* * * * * * *Generals of World War II

{{DEFAULTSORT:Roosevelt, Theodore, Jr. 1887 births 1944 deaths 20th-century American politicians American Express people American veterans' rights activists United States Army personnel of World War I American people of Dutch descent American people of English descent American people of French descent American people of Scottish descent American people of Welsh descent Bulloch family Burials in Normandy Candidates in the 1936 United States presidential election Children of presidents of the United States Children of vice presidents of the United States Governors of Puerto Rico Governors-General of the Philippine Islands Groton School alumni Harvard College alumni Republican Party members of the New York State Assembly Members of the Philadelphia Club Military personnel from New York (state) Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Organization founders People from Oyster Bay (town), New York Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Silver Star Republican Party (Puerto Rico) politicians

Theodore

Theodore may refer to:

Places

* Theodore, Alabama, United States

* Theodore, Australian Capital Territory

* Theodore, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Banana, Australia

* Theodore, Saskatchewan, Canada

* Theodore Reservoir, a lake in Sask ...

Schuyler family

Sons of the American Revolution

The Albany Academy alumni

United States Army generals

United States Army Medal of Honor recipients

United States Assistant Secretaries of the Navy

United States Army generals of World War II

Battle of Normandy recipients of the Medal of Honor

United States Army Infantry Branch personnel