Stephen H. Long on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stephen Harriman Long (December 30, 1784 – September 4, 1864) was an American army civil engineer, explorer, and inventor. As an inventor, he is noted for his developments in the design of steam locomotives. He was also one of the most prolific explorers of the early 1800s, although his career as an explorer was relatively short-lived. He covered over 26,000 miles in five expeditions, including a scientific expedition in the

Like most engineers, Long was college-trained, interested in searching for order in the natural world, and willing to work with the modern technology of the time. Topographical engineers had basically two unique points of view that set them apart from the other pioneers — geographical and technological.

In 1818 he was appointed to organize a scientific contingent to accompany soldiers of Col. Henry Atkinson's command on the Yellowstone Expedition (sometimes called the Atkinson-Long Expedition). This was planned to explore the upper Missouri, and Long spent the autumn designing the construction of an experimental steamboat for the venture, ''

Like most engineers, Long was college-trained, interested in searching for order in the natural world, and willing to work with the modern technology of the time. Topographical engineers had basically two unique points of view that set them apart from the other pioneers — geographical and technological.

In 1818 he was appointed to organize a scientific contingent to accompany soldiers of Col. Henry Atkinson's command on the Yellowstone Expedition (sometimes called the Atkinson-Long Expedition). This was planned to explore the upper Missouri, and Long spent the autumn designing the construction of an experimental steamboat for the venture, ''

Nebraska Studies website

*

The Journal of Captain John R. Bell: official journalist for the Stephen H. Long Expedition to the Rocky Mountains

(1 folder) is housed in th

a

Stanford University Libraries

details a 1600 feet (490 m) length minimalist art sculpture 'Stephen Long', installed by

Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, a ...

area, which he famously confirmed as a "Great Desert" (leading to the term "the Great American Desert").

Biography

Long was born inHopkinton, New Hampshire

Hopkinton is a town in Merrimack County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 5,914 at the 2020 census. The town has three distinct communities: Hopkinton village, mainly a residential area in the center of the town; Contoocook, the to ...

, the son of Moses and Lucy (Harriman) Long. Long's Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

ancestors came from England during the Puritan migration to New England. He received an A.B. from Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native ...

in 1809 and an A.M. from Dartmouth in 1812. In 1814, he was commissioned a lieutenant of engineers in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

, colors =

, anniversaries = 16 June (Organization Day)

, battles =

, battles_label = Wars

, website =

, commander1 = ...

. Upon the reorganization of the Army in 1816, he was appointed a Major on 16 April and assigned to the Southern Division under Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson as a topographical engineer.

In 1817, Major Long headed a military excursion up the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

to the Falls of St. Anthony

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony ( dak, italics=no, Owámniyomni, ) located at the northeastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, is the only natural major waterfall on the Mississippi River. Throughout the mid-to-late 1 ...

near the confluence with the Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

. As a result of his recommendations, the Army established Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anth ...

to guard against Indian incursions against settlers in the Upper Mississippi Valley

The Upper Mississippi River is the portion of the Mississippi River upstream of St. Louis, Missouri, United States, at the confluence of its main tributary, the Missouri River.

History

In terms of geologic and hydrographic history, the U ...

. Long recorded his experiences of the expedition in a journal, which was first published as ''Voyage in a Six-oared Skiff to the Falls of St. Anthony'', by the Minnesota Historical Society in 1860.

In March 1819 he married Martha Hodgkiss of Philadelphia, the sister of Isabella Hodgkiss Norvell, wife of US Senator John Norvell. Soon afterwards he led the scientific contingent of the 1819 Yellowstone Expedition to explore the Missouri River. In 1820 he was appointed to lead an alternative expedition through the American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

, exploring areas acquired in the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

. The specific purpose of the voyage was to find the sources of the Platte, Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

, and Red rivers.

Later, in 1823 he led additional military expeditions into the United States borderlands with Canada, exploring the Upper Mississippi Valley, the Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

, the Red River of the North

The Red River (french: rivière Rouge or ) is a river in the north-central United States and central Canada. Originating at the confluence of the Bois de Sioux and Otter Tail rivers between the U.S. states of Minnesota and North Dakota, it fl ...

and across the southern part of Canada. During this time he determined the northern boundary at the 49th parallel at Pembina. In that same year, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

Following his official military expeditions, Major Long spent several years on detached duty as a consulting engineer with various railroads. Initially he helped to survey and build the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

. In 1826, he received his first patent for his work on railroad steam locomotives. Long received many more patents for locomotive design and worked with other Army engineers in planning and building the railroad. Long also received patents in 1830 and 1839 for pre-stressing the trusses used in wooden covered bridges.

In 1832, along with William Norris and several other business partners, he formed the American Steam Carriage Company

The Norris Locomotive Works was a steam locomotive manufacturing company based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, that produced nearly one thousand railroad engines between 1832 and 1866. It was the dominant American locomotive producer during most of ...

. The business was dissolved in 1834 due to the difficulties in placing Long's locomotive designs into production. From June to November, 1836, Long led two parties of about 15 each to conduct a survey of a route inland from the shores of the Penobscot Bay

Penobscot Bay (french: Baie de Penobscot) is an inlet of the Gulf of Maine and Atlantic Ocean in south central Maine. The bay originates from the mouth of Maine's Penobscot River, downriver from Belfast. Penobscot Bay has many working waterf ...

at Belfast, Maine

Belfast is a city in Waldo County, Maine, in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 6,938. Located at the mouth of the Passagassawakeag River estuary on Belfast Bay and Penobscot Bay. Belfast is the county seat ...

to Quebec for the proposed Belfast & Quebec Railroad which had been chartered by the State of Maine on March 6, 1836. In his report to Governor Robert P. Dunlap of Maine, Col. Long recommended a route into Quebec of 227 miles from "Belfast to the Forks of the Kennebec, and by a line of levels thence to the Canadian line." However a then provision in the Maine Constitution which prohibited public loans for purposes such as building railroads as well as the financial panic of 1837 intervened to kill the project.

Colonel Long received a leave of absence to work on the newly incorporated Western & Atlantic Railroad

The Western & Atlantic Railroad of the State of Georgia (W&A) is a railroad owned by the State of Georgia and currently leased by CSX, which CSX operates in the Southeastern United States from Atlanta, Georgia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee.

It was fo ...

in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. His yearly salary was established at $5,000, the contract was signed May 12, 1837, and he served as the chief engineer for the W&A until November 3, 1840. He arrived in north Georgia in late May and his surveying began in July and by November he had submitted an initial report which the construction followed almost exactly.

In 1838 he was appointed to a position in the newly separated U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers. Like most of their officers Major Long remained loyal to the Federal government during the Civil War, and he became Colonel of the Corps in 1861 until its merger back into the U.S. Corps of Engineers in 1863. He died in Alton, Illinois

Alton ( ) is a city on the Mississippi River in Madison County, Illinois, Madison County, Illinois, United States, about north of St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri. The population was 25,676 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. It is a p ...

in 1864.

Expeditions

Great Plains (1820)

Like most engineers, Long was college-trained, interested in searching for order in the natural world, and willing to work with the modern technology of the time. Topographical engineers had basically two unique points of view that set them apart from the other pioneers — geographical and technological.

In 1818 he was appointed to organize a scientific contingent to accompany soldiers of Col. Henry Atkinson's command on the Yellowstone Expedition (sometimes called the Atkinson-Long Expedition). This was planned to explore the upper Missouri, and Long spent the autumn designing the construction of an experimental steamboat for the venture, ''

Like most engineers, Long was college-trained, interested in searching for order in the natural world, and willing to work with the modern technology of the time. Topographical engineers had basically two unique points of view that set them apart from the other pioneers — geographical and technological.

In 1818 he was appointed to organize a scientific contingent to accompany soldiers of Col. Henry Atkinson's command on the Yellowstone Expedition (sometimes called the Atkinson-Long Expedition). This was planned to explore the upper Missouri, and Long spent the autumn designing the construction of an experimental steamboat for the venture, ''Western Engineer

The paddle steamer ''Western Engineer'' was the first steamboat on the Missouri River. It was purpose built after a design by Major Stephen Harriman Long by the Allegheny Arsenal in Pittsburgh, for the scientific party of the Yellowstone expedi ...

''. Departing from St. Louis in June 1819, it was the first steamboat to travel up the Missouri River into the Louisiana Purchase, and the first steamboat to have a stern paddle wheel. On September 17, Long's party arrived at Fort Lisa, a trading fort belonging to William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Miss ...

's Missouri Fur Company. It was about five miles south of Council Bluffs

Council Bluffs is a city in and the county seat of Pottawattamie County, Iowa, United States. The city is the most populous in Southwest Iowa, and is the third largest and a primary city of the Omaha-Council Bluffs Metropolitan Area. It is loc ...

, Iowa. Long's group built their winter quarters nearby and called it "Engineer Cantonment

Engineer Cantonment is an archaeological site in Washington County, in the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States. Located in the floodplain of the Missouri River near present-day Omaha, Nebraska, it was the temporary winter camp of ...

."

Within a month, Long returned to the east coast, and by the following May, his orders had changed. The Yellowstone Expedition had become a costly failure and so instead of exploring the Missouri River, President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

decided to have Long lead an expedition up the Platte River

The Platte River () is a major river in the State of Nebraska. It is about long; measured to its farthest source via its tributary, the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which itsel ...

to the Rocky mountains and back along the border with the Spanish colonies. Exploring that border was vital, since John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

had just concluded the treaty with Spain, which drew a new U.S. border to the Pacific.

Major Long was the leader of the first scientific exploration up the Platte, which planned to study the geography and natural resources of the area. His party of 19 men included landscape painter Samuel Seymour, naturalist painter Titian Peale

Titian Ramsay Peale (November 2, 1799 – March 13, 1885) was an American artist, naturalist, and explorer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a scientific illustrator whose paintings and drawings of wildlife are known for their beauty an ...

, zoologist Thomas Say

Thomas Say (June 27, 1787 – October 10, 1834) was an American entomologist, conchologist, and herpetologist. His studies of insects and shells, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Georgia, the R ...

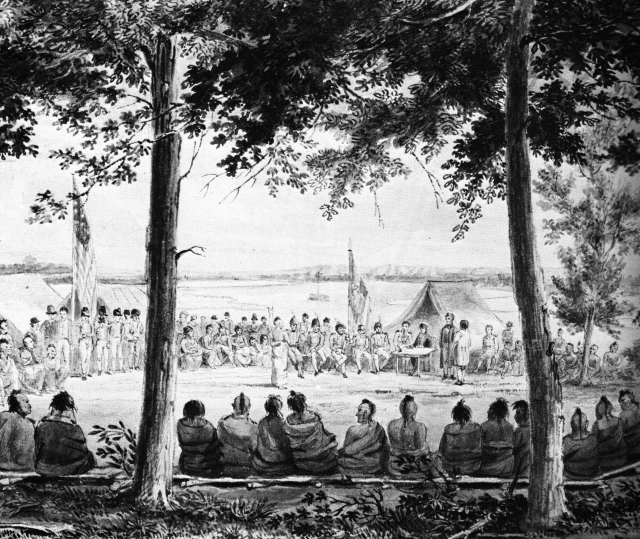

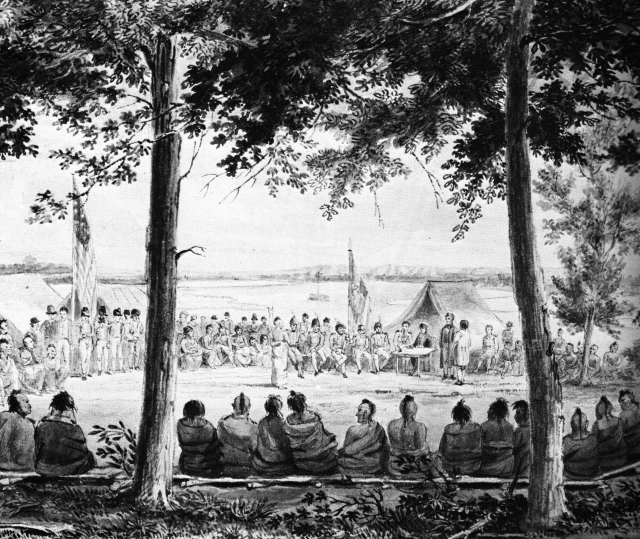

and Edwin James, a physician knowledgeable in both geology and botany. James led the first recorded ascent of Pikes Peak during this expedition. On June 6, 1820, they traveled up the north bank of the Platte and met Pawnee and Otoe Indians. On October 14, 1820, 400 Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest c ...

assembled at a meeting with Long, where Chief Big Elk

Big Elk, also known as ''Ontopanga'' (1765/75–1846/1848), was a principal chief of the Omaha tribe for many years on the upper Missouri River. He is notable for his oration delivered at the funeral of Black Buffalo in 1813.

Big Elk led his p ...

made the following speech:

:"Here I am, my Father; all these young people you see around here are yours; although they are poor and little, yet they are your children. All my nation loves the whites and always have loved them. Some think, my Father, that you have brought all these soldiers here to take our land from us but I do not believe it. For although I am a poor simple Indian, I know that this land will not suit your farmers. If I even thought your hearts bad enough to take this land, I would not fear it, as I know there is not wood enough on it for the use of the white."

Long wrote that the Pawnee people were "respectable." After finding and naming Longs Peak

Longs Peak (Arapaho: ) is a high and prominent mountain in the northern Front Range of the Rocky Mountains of North America. The fourteener is located in the Rocky Mountain National Park Wilderness, southwest by south ( bearing 209°) of th ...

and the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

, they journeyed up the South Platte River

The South Platte River is one of the two principal tributaries of the Platte River. Flowing through the U.S. states of Colorado and Nebraska, it is itself a major river of the American Midwest and the American Southwest/Mountain West. It ...

to the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United ...

watershed. The expedition was then split, and Long led his group towards the Red River. They missed it, ran into hostile Indians and had to eventually eat their own horses to survive before they finally met the other part of the expedition at Fort Smith (now a city on the western border of the state of Arkansas).

Report

In his report of the 1820 expedition, Long wrote that the Plains from Nebraska to Oklahoma were "unfit for cultivation and of course uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture." On the map he made of his explorations, he called the area a "Great Desert." Long felt the area labeled the "Great Desert" would be better suited as a buffer against the Spanish, British, and Russians, who shared the continent with the United States. He also commented that the eastern wooded portion of the country should be filled up before the republic attempted any further extension westward. He commented that sending settlers to that area was out of the question. Given the technology of the 1820s, Long was right. There was little timber for houses or fuel, minimal surface water, sandy soil, hard winters, vast herds ofbison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North A ...

, hostile Indians, and no easy means of communication. However, it is ironic that the native tribes had been living there for centuries and that, by the end of the 19th century, the "Great Desert" had become the nation's breadbasket.

There were two key results of this expedition—a very accurate description of Indian customs and Indian life as they existed among the Omaha, Otoes, and Pawnees and his description of the land west of the Missouri River as a "desert".

Red River of the North (1823)

Major Long's 1823 expedition up theMinnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

(then known as St. Peter's River), to the headwaters of the Red River of the North

The Red River (french: rivière Rouge or ) is a river in the north-central United States and central Canada. Originating at the confluence of the Bois de Sioux and Otter Tail rivers between the U.S. states of Minnesota and North Dakota, it fl ...

, down that river to Pembina and Fort Garry

Fort Garry, also known as Upper Fort Garry, was a Hudson's Bay Company trading post at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in what is now downtown Winnipeg. It was established in 1822 on or near the site of the North West Company' ...

, and thence by canoe across British Canada to Lake Huron

Lake Huron ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. Hydrologically, it comprises the easterly portion of Lake Michigan–Huron, having the same surface elevation as Lake Michigan, to which it is connected by the , Straits of Mack ...

is sometimes confused with his initial expedition to the Red River in modern-day Texas and Oklahoma. The expedition to the Red River of the North was a separate, later appointment which completed a series of explorations conceived of by Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

and implemented by David Bates Douglass

David Bates Douglass (March 21, 1790 – October 21, 1849) was a civil and military engineer, who worked on a broad set of projects throughout his career. For fifteen years he was a professor at the United States Military Academy, and after his ...

, Henry Schoolcraft

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (March 28, 1793 – December 10, 1864) was an American geographer, geologist, and ethnologist, noted for his early studies of Native American cultures, as well as for his 1832 expedition to the source of the Mississippi R ...

, and others besides Major Long. The 1823 expedition was denoted primarily as a scientific reconnaissance and an evaluation of trade possibilities, but probably had undisclosed military objectives as well, and certainly was viewed with suspicion by British authorities in Canada. This expedition for a time was joined by the Italian adventurer Giacomo Beltrami

Giacomo Costantino Beltrami (1779 – January 6, 1855) was an Italian jurist, author, and explorer, known for claiming to have discovered the headwaters of the Mississippi River in 1823 while on a trip through much of the United States (later exp ...

, who argued with Long and left the expedition near Fort Garry. The 1823 expedition encouraged American traders to push into the fur trade in Northern Minnesota and Dakota, and fostered the development of the Red River Trails

The Red River Trails were a network of ox cart routes connecting the Red River Colony (the "Selkirk Settlement") and Fort Garry in British North America with the head of navigation on the Mississippi River in the United States. These trade route ...

and a colorful chapter of ox cart

A bullock cart or ox cart (sometimes called a bullock carriage when carrying people in particular) is a two-wheeled or four-wheeled vehicle pulled by oxen. It is a means of transportation used since ancient times in many parts of the world. The ...

trade between the Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assinboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hudson's Bay ...

and Fort Garry

Fort Garry, also known as Upper Fort Garry, was a Hudson's Bay Company trading post at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in what is now downtown Winnipeg. It was established in 1822 on or near the site of the North West Company' ...

via Pembina and the newly developing towns of Mendota and St. Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

.

Marine Hospitals and Napoleon, Arkansas

In 1837 Congress authorized the building of seven Marine Hospitals. Long was commissioned to build the first hospital for the Treasury Department at Louisville, Kentucky. Long had been commissioned to build the hospital along with his other duties but construction would be delayed until the Mexican War was over. It wasn't until the end of 1845 that work finally began. During the completion of the Louisville Marine Hospital, Long would also start work on building similar Marine Hospitals in Paducah, Kentucky; Natchez, Louisiana and Napoleon, Arkansas. These Marine Hospitals were based upon plans provided by Robert Mills, the architect of the Washington Monument. Long was commissioned to build the Marine Hospital at Napoleon, Arkansas in 1849. Napoleon, Arkansas was situated at the southern mouth of the Arkansas River. After a completing a survey Long had objections to building at Napoleon because of the tendency for flooding and likelihood that the town would face destruction in the future thanks to the unwieldy Mississippi and Arkansas Rivers. He had petitioned for Helena, Arkansas to be a suitable alternative. In early 1850 Long's objections to the location were rebuffed. Senator Solon Borland, ignoring Long's objections to the location of Napoleon, reported to the Corps of Topographical Engineers that the situation at Napoleon had been discussed before the bill which would create the Marine Hospital at Napoleon was passed. The erection of the hospital at Napoleon without delay was then ordered. In the Spring of 1850 Long requested $10,250 in order to begin construction at Napoleon but it wasn't until August that construction finally started thanks to flooding which hampered building the foundation and cellar. Delays continued to dog the construction and by the Spring of 1851 the supervisor wrote Long suggesting suspension of the work as contracts were expiring due to delays and sickness had been rampant thanks to Spring floods. Work resumed in October 1851 and the slow pace continued over the next three years. By August 1854 the hospital was finally finished but apparently the hospital did not accept its first patients until 1855. The city of Napoleon would be burned in 1862 by General Sherman, but the hospital survived. Federal Forces did not use the hospital for its intended purpose, instead patients were sent elsewhere. While the hospital did survive the war it wouldn't last long. Long's observations and objections had been accurate. By March 11, 1868 the river had eroded the land to 52 feet from the hospital's doors. Less than a month later, and nearly four years after Long's death, a corner of the hospital fell into the Mississippi River. The entire town of Napoleon was swallowed twenty-eight years after Long first objected to building the hospital at Napoleon. Of the Marine Hospitals that Long oversaw, the hospital at Louisville, Kentucky, remains today.See also

* New Hampshire Historical Marker No. 179: Smith Bridge * New Hampshire Historical Marker No. 196: Blair BridgeNotes

References

* Goetzmann, William H. ''Army Exploration in the American West 1803-1863'' (Yale University Press, 1959; University of Nebraska Press, 1979) * Johnston, James Houstoun, ''Western and Atlantic Railroad of the State of Georgia'', Atlanta, 1931 * Kane, Lucile M., Holmquist, June D., and Gilman, Caroly, eds., ''The Northern Expeditions of Stephen H. Long: The Journals of 1817 and 1823 and Related Documents'' (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1978). * * *Nebraska Studies website

*

Research resources

The Journal of Captain John R. Bell: official journalist for the Stephen H. Long Expedition to the Rocky Mountains

(1 folder) is housed in th

a

Stanford University Libraries

External links

*details a 1600 feet (490 m) length minimalist art sculpture 'Stephen Long', installed by

Patricia Johanson

Patricia Johanson (born September 8, 1940, New York City) is an American artist. Johanson is known for her large-scale art projects that create aesthetic and practical habitats for humans and wildlife. She designs her functional art projects, c ...

in 1968 along an abandoned railroad track in Buskirk, upper New York.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Long, Stephen Harriman

1784 births

1864 deaths

American explorers

Dartmouth College alumni

American people of English descent

American railway civil engineers

Explorers of the United States

People from Hopkinton, New Hampshire

Members of the American Philosophical Society

Military personnel from New Hampshire

United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers