Special Operations, Executive on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British World War II organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under

As part of the subsequent closer ties between the

As part of the subsequent closer ties between the

After working from temporary offices in Central London, the headquarters of SOE was moved on 31 October 1940 into

After working from temporary offices in Central London, the headquarters of SOE was moved on 31 October 1940 into

Most of the resistance networks which SOE formed or liaised with were controlled by radio directly from Britain or one of SOE's subsidiary headquarters. All resistance circuits contained at least one wireless operator, and all drops or landings were arranged by radio, except for some early exploratory missions sent "blind" into enemy-occupied territory.

At first, SOE's radio traffic went through the SIS-controlled radio station at Bletchley Park. From 1 June 1942 SOE used its own transmitting and receiving stations at

Most of the resistance networks which SOE formed or liaised with were controlled by radio directly from Britain or one of SOE's subsidiary headquarters. All resistance circuits contained at least one wireless operator, and all drops or landings were arranged by radio, except for some early exploratory missions sent "blind" into enemy-occupied territory.

At first, SOE's radio traffic went through the SIS-controlled radio station at Bletchley Park. From 1 June 1942 SOE used its own transmitting and receiving stations at

161 Squadron's principal aircraft was the Westland Lysander. It handled very well at low speed and could land from touch down to turn around in only . It had a range of and could carry one to three passengers in the rear cockpit and stores in a pannier underneath the fuselage. It was flown by a single pilot, who also had to navigate, so missions had to be flown on clear nights with a full or near full moon. Bad weather often thwarted missions, German night fighters were also a hazard, and pilots could never know when landing whether they would be greeted by the resistance or the Gestapo.Orchard, Adrian ''Group Captain Percy Charles "Pick" Pickard DSO**, DFC 1915 – 1944'' February 2006

The procedure once a Lysander reached its destination in France was described by Squadron Leader Hugh Verity. Once the aircraft reached the airfield the agent on the ground would signal the aircraft by flashing a prearranged code letter in

161 Squadron's principal aircraft was the Westland Lysander. It handled very well at low speed and could land from touch down to turn around in only . It had a range of and could carry one to three passengers in the rear cockpit and stores in a pannier underneath the fuselage. It was flown by a single pilot, who also had to navigate, so missions had to be flown on clear nights with a full or near full moon. Bad weather often thwarted missions, German night fighters were also a hazard, and pilots could never know when landing whether they would be greeted by the resistance or the Gestapo.Orchard, Adrian ''Group Captain Percy Charles "Pick" Pickard DSO**, DFC 1915 – 1944'' February 2006

The procedure once a Lysander reached its destination in France was described by Squadron Leader Hugh Verity. Once the aircraft reached the airfield the agent on the ground would signal the aircraft by flashing a prearranged code letter in

In France, most agents were directed by two London-based country sections. F Section was under SOE control, while RF Section was linked to

In France, most agents were directed by two London-based country sections. F Section was under SOE control, while RF Section was linked to

Section N of SOE ran operations in the Netherlands. They committed some of SOE's worst blunders in security, which allowed the Germans to capture many agents and much sabotage material, in what the Germans called the '

Section N of SOE ran operations in the Netherlands. They committed some of SOE's worst blunders in security, which allowed the Germans to capture many agents and much sabotage material, in what the Germans called the '

SOE sent many missions into the Czech areas of the so-called Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, and later into Slovakia. The most famous mission was Operation Anthropoid, the assassination of SS- Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich in Prague. From 1942 to 1943 the

SOE sent many missions into the Czech areas of the so-called Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, and later into Slovakia. The most famous mission was Operation Anthropoid, the assassination of SS- Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich in Prague. From 1942 to 1943 the

As early as 1940, SOE was preparing plans for operations in Southeast Asia. As in Europe, after initial Allied military disasters, SOE built up indigenous resistance organisations and guerrilla armies in enemy ( Japanese) occupied territory. SOE also launched ''"Operation Remorse"'' (1944–45), which was ultimately aimed at protecting the economic and political status of Hong Kong. Force 136 engaged in covert trading of goods and currencies in China. Its agents proved remarkably successful, raising £77m through their activities, which were used to provide assistance for Allied prisoners of war and, more controversially, to buy influence locally to facilitate a smooth return to pre-war conditions.

As early as 1940, SOE was preparing plans for operations in Southeast Asia. As in Europe, after initial Allied military disasters, SOE built up indigenous resistance organisations and guerrilla armies in enemy ( Japanese) occupied territory. SOE also launched ''"Operation Remorse"'' (1944–45), which was ultimately aimed at protecting the economic and political status of Hong Kong. Force 136 engaged in covert trading of goods and currencies in China. Its agents proved remarkably successful, raising £77m through their activities, which were used to provide assistance for Allied prisoners of war and, more controversially, to buy influence locally to facilitate a smooth return to pre-war conditions.

"Notes on S.O.E., 1941 TO 1943"

written by a member of the Belgian Section, Major G.T.R. Thompson, in 1963

* ttp://nigelperrin.com/soeagents.htm Profiles of Special Operations Executive Agents in Franceat Nigel Perrin's site

Colin Gubbins, Leo Marks and the SOE

Dudley Maurice Newitt. Director of Scientific Research. SOE.

The Violette Szabo Museum

The Special Operations Executive

- British Foreign & Commonwealth Office

Imperial War Museum (London)

Special_Operations_Executive

- Imperial War Museum

"Mission Scapula" Special Operations Executive in the Far East.

Target near Glasnacardoch Lodge STS22a

near

The 11th Day

film about SOE & Crete Resistance, and Patrick Leigh Fermor

Para-Military Training in Arisaig, Scotland During World War 2

Land, Sea & Islands Centre

SOE: An Amateur Outfit?

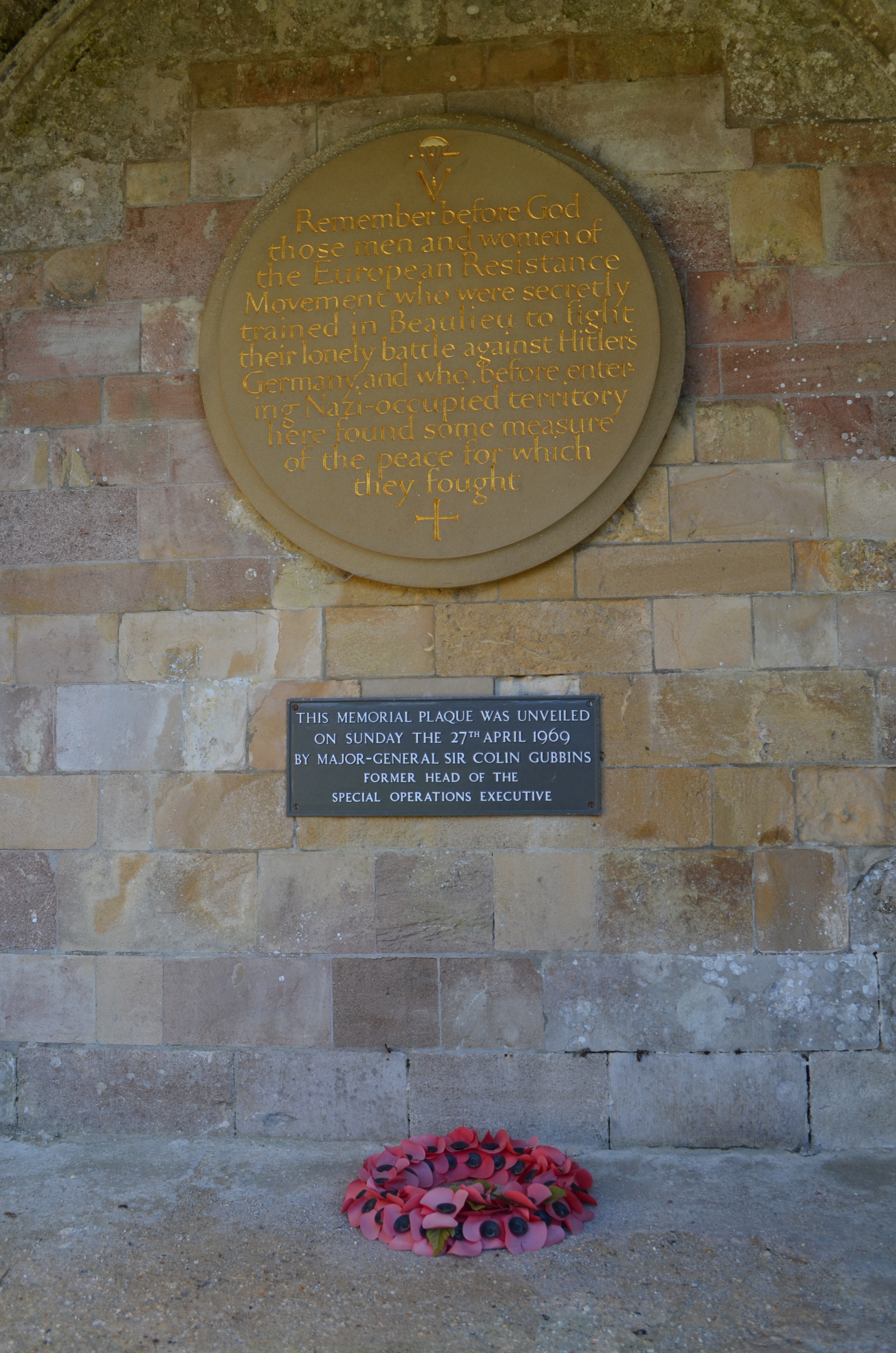

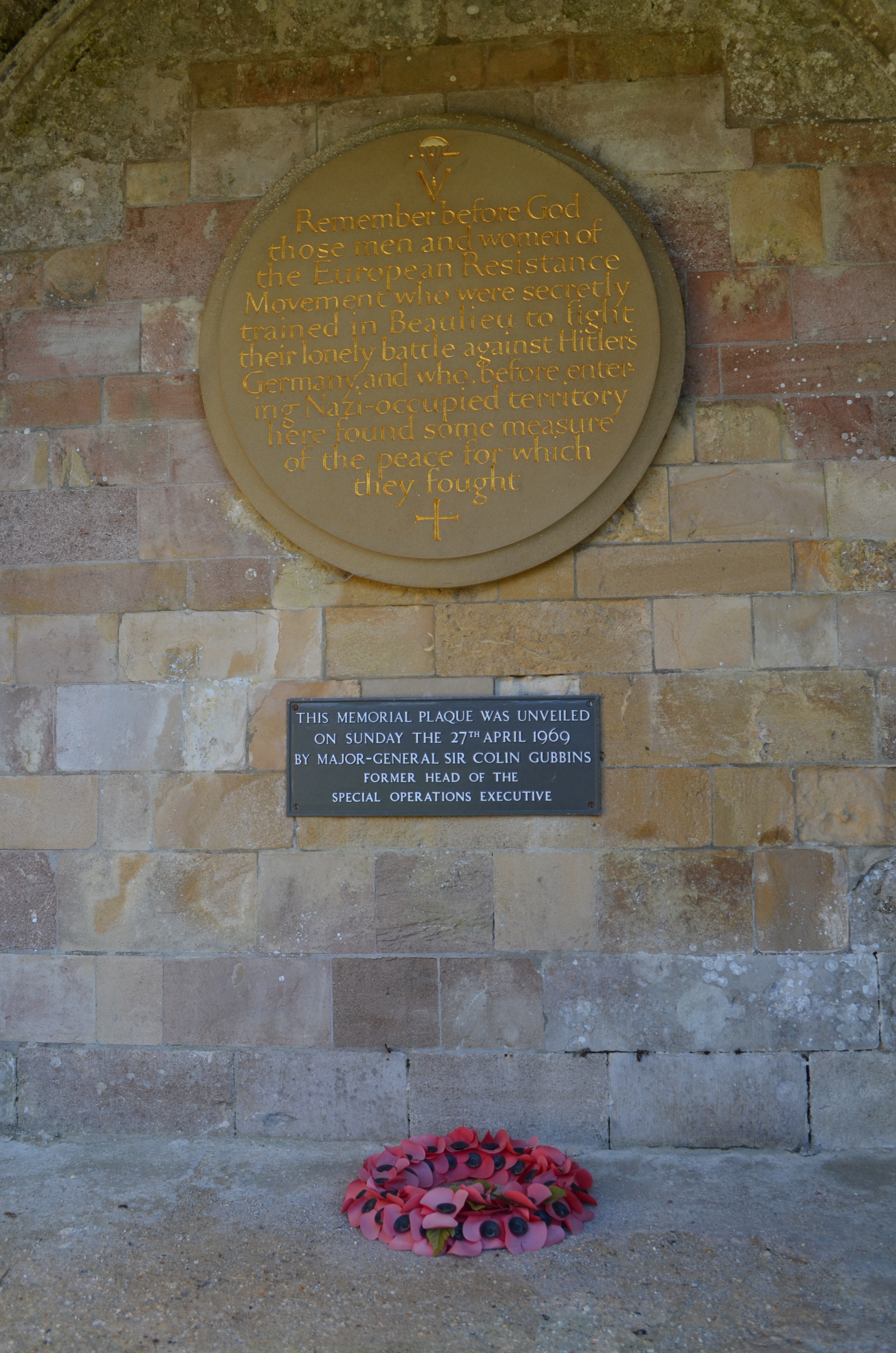

Secret Army Exhibition at Beaulieu

SOE

''Special Forces Roll Of Honour'' {{Authority control 1940 establishments in the United Kingdom 1946 disestablishments in the United Kingdom Covert organizations Saboteurs Ministry of Economic Warfare World War II resistance movements British intelligence services of World War II Government agencies established in 1940 Government agencies disestablished in 1946

Minister of Economic Warfare

The Minister of Economic Warfare was a British government position which existed during the Second World War. The minister was in charge of the Special Operations Executive and the Ministry of Economic Warfare.

See also

* Blockade of Germany (193 ...

Hugh Dalton

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton, (16 August 1887 – 13 February 1962) was a British Labour Party economist and politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947. He shaped Labour Party foreign policy in the 1 ...

, from the amalgamation of three existing secret organisations. Its purpose was to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in occupied Europe (and later, also in occupied Southeast Asia) against the Axis powers, and to aid local resistance movements.

Few people were aware of SOE's existence. Those who were part of it or liaised with it were sometimes referred to as the " Baker Street Irregulars", after the location of its London headquarters. It was also known as "Churchill's Secret Army" or the "Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare". Its various branches, and sometimes the organisation as a whole, were concealed for security purposes behind names such as the "Joint Technical Board" or the "Inter-Service Research Bureau", or fictitious branches of the Air Ministry, Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

* Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

*Admiralty, Tr ...

or War Office.

SOE operated in all territories occupied or attacked by the Axis forces, except where demarcation lines were agreed upon with Britain's principal Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

(the United States and the Soviet Union). It also made use of neutral territory on occasion or made plans and preparations in case neutral countries were attacked by the Axis. The organisation directly employed or controlled more than 13,000 people, about 3,200 of whom were women.

After the war, the organisation was officially dissolved on 15 January 1946. The official memorial to all those who served in the SOE during the Second World War was unveiled on 13 February 1996 on the wall of the west cloister of Westminster Abbey by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (4 August 1900 – 30 March 2002) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 to 6 February 1952 as the wife of King George VI. She was the l ...

. A further memorial to SOE's agents was unveiled in October 2009 on the Albert Embankment in London. The Valençay SOE Memorial honours 104 SOE agents who lost their lives while working in France. The Tempsford Memorial was unveiled on 3 December 2013 by Charles, Prince of Wales, in Church End, Tempsford in Bedfordshire, close to the site of former RAF Tempsford

RAF Tempsford is a former Royal Air Force station located north east of Sandy, Bedfordshire, Sandy, Bedfordshire, England and south of St. Neots, Cambridgeshire, England.

As part of the Royal Air Force Special Duty Service, the airfield wa ...

.

History

Origins

The organisation was formed from the merger of three existing secret departments, which had been formed shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War. Immediately after Germany annexed Austria (the '' Anschluss'') in March 1938, theForeign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

created a propaganda organisation known as Department EH (after Electra House, its headquarters), run by Canadian newspaper magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

Sir Campbell Stuart

Sir Campbell Arthur Stuart (5 July 1885 – 14 September 1972) was a Canadian newspaper magnate. He ran propaganda operations for the British during both World Wars.

Early life

In 1885 Campbell Arthur Stuart was born in Montreal, Canada to st ...

. Later that month, the Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

(SIS, also known as MI6) formed a section known as Section D (the "D" apparently standing for "Destruction") under Major Lawrence Grand, to investigate the use of sabotage, propaganda, and other irregular means to weaken an enemy. In the autumn of the same year, the War Office expanded an existing research department known as GS (R) and appointed Major J. C. Holland as its head to conduct research into guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or Irregular military, irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, Raid (military), raids ...

. GS (R) was renamed MI(R) in early 1939.

These three departments worked with few resources until the outbreak of war. There was much overlap between their activities. Section D and EH duplicated much of each other's work. On the other hand, the heads of Section D and MI(R) knew each other and shared information. They agreed to a rough division of their activities; MI(R) researched irregular operations that could be undertaken by regular uniformed troops, while Section D dealt with truly undercover work.

During the early months of the war, Section D was based first at St Ermin's Hotel

St. Ermin's Hotel is a four-star central London hotel adjacent to St James's Park Underground station, close to Westminster Abbey, Buckingham Palace, and the Houses of Parliament. The Grade II-listed late Victorian building, built as one of ...

in Westminster and then the Metropole Hotel near Trafalgar Square. The Section attempted unsuccessfully to sabotage deliveries of vital strategic material

Strategic material is any sort of raw material that is important to an individual's or organization's strategic plan and supply chain management. Lack of supply of strategic materials may leave an organization or government vulnerable to disru ...

s to Germany from neutral countries by mining the Iron Gate on the River Danube. MI(R) meanwhile produced pamphlets and technical handbooks for guerrilla leaders. MI(R) was also involved in the formation of the Independent Companies

A privately held company (or simply a private company) is a company whose shares and related rights or obligations are not offered for public subscription or publicly negotiated in the respective listed markets, but rather the company's stock is ...

, autonomous units intended to carry out sabotage and guerrilla operations behind enemy lines in the Norwegian Campaign, and the Auxiliary Units

The Auxiliary Units or GHQ Auxiliary Units were specially-trained, highly-secret quasi military units created by the British government during the Second World War with the aim of using irregular warfare in response to a possible invasion of the U ...

, stay-behind commando units based on the Home Guard which would act in the event of an Axis invasion of Britain, as seemed possible in the early years of the war.

Formation

On 13 June 1940, at the instigation of newly appointed Prime MinisterWinston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, Lord Hankey

Maurice Pascal Alers Hankey, 1st Baron Hankey, (1 April 1877 – 26 January 1963) was a British civil servant who gained prominence as the first Cabinet Secretary and later made the rare transition from the civil service to ministerial office. ...

(who held the Cabinet post of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster) persuaded Section D and MI(R) that their operations should be coordinated. On 1 July, a Cabinet level meeting arranged the formation of a single sabotage organisation. On 16 July, Hugh Dalton

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton, (16 August 1887 – 13 February 1962) was a British Labour Party economist and politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947. He shaped Labour Party foreign policy in the 1 ...

, the Minister of Economic Warfare

The Minister of Economic Warfare was a British government position which existed during the Second World War. The minister was in charge of the Special Operations Executive and the Ministry of Economic Warfare.

See also

* Blockade of Germany (193 ...

, was appointed to take political responsibility for the new organisation, which was formally created on 22 July 1940. Dalton recorded in his diary that on that day the War Cabinet agreed to his new duties and that Churchill had told him, "And now go and set Europe ablaze." Dalton used the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

as a model for the organisation.

Sir Frank Nelson was nominated by SIS to be director of the new organisation, and a senior civil servant

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

, Gladwyn Jebb, transferred from the Foreign Office to it, with the title of Chief Executive Officer. Campbell Stuart left the organisation, and the flamboyant Major Grand was returned to the regular army. At his own request, Major Holland also left to take up a regular appointment in the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

. (Both Grand and Holland eventually attained the rank of major-general.) However, Holland's former deputy at MI(R), Brigadier Colin Gubbins

Major-General Sir Colin McVean Gubbins (2 July 1896 – 11 February 1976) was the prime mover of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in the Second World War.

Gubbins was also responsible for setting up the secret Auxiliary Units, a commando ...

, returned from command of the Auxiliary Units to be Director of Operations of SOE.

One department of MI(R), MI R(C), which was involved in the development of weapons for irregular warfare, was not formally integrated into SOE but became an independent body codenamed MD1. Directed by Major (later Lieutenant Colonel) Millis Jefferis, it was located at The Firs in Whitchurch, Buckinghamshire

Whitchurch is a village and civil parish in the unitary authority area of Buckinghamshire, England. The village is on the A413 road about north of Aylesbury and south of Winslow. The 2011 Census recorded a parish population of 932.

Toponym

T ...

and nicknamed "Churchill's Toyshop" from the Prime Minister's close interest in it and his enthusiastic support.

Leadership

The director of SOE was usually referred to by the initials "CD". Nelson, the first director to be appointed, was a former head of a trading firm in India, aback bench

In Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no governmental office and is not a frontbench spokesperson in the Opposition, being instead simply a member of the " ...

Conservative Member of Parliament and Consul in Basel, Switzerland, where he had also been engaged in undercover intelligence work.

In February 1942 Dalton was removed as the political head of SOE (possibly because he was using the SOE's phone tapping facility to listen to conversations of fellow Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

ministers, or possibly because he was viewed as too “communistically inclined” and a threat to SIS). He became President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. This is a committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centu ...

and was replaced as Minister of Economic Warfare by Lord Selborne

Earl of Selborne, in the County of Southampton, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1882 for the lawyer and Liberal politician Roundell Palmer, 1st Baron Selborne, along with the subsidiary title of Viscount Wol ...

. Selborne in turn retired Nelson, who had suffered ill health as a result of his hard work, and appointed Sir Charles Hambro, head of Hambros Bank, to replace him. He also transferred Jebb back to the Foreign Office.

Hambro had been a close friend of Churchill before the war and had won the Military Cross in the First World War. He retained several other interests, for example remaining chairman of Hambros and a director of the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran ...

. Some of his subordinates and associates expressed reservations that these interests distracted him from his duties as director. Selborne and Hambro nevertheless cooperated closely until August 1943, when they fell out over the question of whether SOE should remain a separate body or co-ordinate its operations with those of the British Army in several theatres of war. Hambro felt that any loss of autonomy would cause a number of problems for SOE in the future. At the same time, Hambro was found to have failed to pass on vital information to Selborne. He was dismissed as director, and became head of a raw material

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials that are feedstock for future finished products. As feedst ...

s purchasing commission in Washington, D.C., which was involved in the exchange of nuclear information.

As part of the subsequent closer ties between the

As part of the subsequent closer ties between the Imperial General Staff

The Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board. Prior to 1964, the title was Chief of the Imperial G ...

and SOE (although SOE had no representation on the Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Chiefs of Staff Committee (CSC) is composed of the most senior military personnel in the British Armed Forces who advise on operational military matters and the preparation and conduct of military operations. The committee consists of the Ch ...

), Hambro's replacement as director from September 1943 was Gubbins, who had been promoted to Major-general. Gubbins had wide experience of commando and clandestine operations and had played a major part in MI(R)'s and SOE's early operations. He also put into practice many of the lessons he learned from the IRA during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

.

Organisation

Headquarters

The organisation of SOE continually evolved and changed during the war. Initially, it consisted of three broad departments: SO1 (formerly Department EH, which dealt with propaganda); SO2 (formerly Section D, operations); and SO3 (formerly MI R, research). SO3 was quickly overloaded with paperwork and was merged into SO2. In August 1941, following quarrels between the Ministry of Economic Warfare and the Ministry of Information over their relative responsibilities, SO1 was removed from SOE and became an independent organisation, the Political Warfare Executive. Thereafter, a single, broad "Operations" department controlled the Sections operating into enemy and sometimes neutral territory, and the selection and training of agents. Sections, usually referred to by code letters or groups of letters, were assigned to a single country. Some enemy-occupied countries had two or more sections assigned to deal with politically disparate resistance movements. (France had no less than six). For security purposes, each section had its own headquarters and training establishments. This strict compartmentalisation was so effective that in mid-1942 five governments in exile jointly suggested that a single sabotage organisation be created, and were startled to learn that SOE had been in existence for two years. Four departments and some smaller groups were controlled by the director of scientific research, ProfessorDudley Maurice Newitt

Dudley Maurice Newitt FRS (28 April 1894 – 14 March 1980) was a British chemical engineer who was awarded the Rumford Medal in 1962 in recognition of his 'distinguished contributions to chemical engineering'.

Newitt was born in London and s ...

, and were concerned with the development or acquisition and production of special equipment. A few other sections were involved with finance, security, economic research and administration, although SOE had no central registry or filing system. When Gubbins was appointed director, he formalised some of the administrative practices which had grown in an ''ad hoc'' fashion and appointed an establishment officer to oversee the manpower and other requirements of the various departments.

The main controlling body of SOE was its council, consisting of around fifteen heads of departments or sections. About half of the council were from the armed forces (although some were specialists who were only commissioned after the outbreak of war), the rest were various civil servants

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

, lawyers, or business or industrial experts. Most of the members of the council, and the senior officers and functionaries of SOE generally, were recruited by word of mouth among public school alumni and Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of Oxford and Cambridge, the two oldest, wealthiest, and most famous universities in the United Kingdom. The term is used to refer to them collectively, in contrast to other British universities, and more broadly to de ...

graduates, although this did not notably affect SOE's political complexion.

Subsidiary branches

Several subsidiary SOE headquarters and stations were set up to manage operations which were too distant for London to control directly. SOE's operations in the Middle East and Balkans were controlled from a headquarters in Cairo, which was notorious for poor security, infighting and conflicts with other agencies. It finally became known in April 1944 as Special Operations (Mediterranean), or SO(M). Shortly after theAllied landings in North Africa

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – 16 November 1942) was an Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa while all ...

, a station codenamed ''"Massingham"'' was established near Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

in late 1942, which operated into Southern France

Southern France, also known as the South of France or colloquially in French language, French as , is a defined geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi ...

. Following the Allied invasion of Italy, personnel from "Massingham" established forward stations in Brindisi

Brindisi ( , ) ; la, Brundisium; grc, Βρεντέσιον, translit=Brentésion; cms, Brunda), group=pron is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea.

Histo ...

and near Naples. A subsidiary headquarters initially known as "Force 133" was later set up in Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy a ...

in Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

, under the Cairo headquarters, to control operations in the Balkans and Northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative regions ...

.

An SOE station, which was first called the ''India Mission'', and was subsequently known as ''GS I(k)'' was set up in India late in 1940. It subsequently moved to Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

so as to be closer to the headquarters of the Allied South East Asia Command and became known as Force 136

Force 136 was a far eastern branch of the British World War II intelligence organisation, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Originally set up in 1941 as the India Mission with the cover name of GSI(k), it absorbed what was left of SOE's Or ...

. A ''Singapore Mission'' was set up at the same time as the India Mission but was unable to overcome official opposition to its attempts to form resistance movements in Malaya

Malaya refers to a number of historical and current political entities related to what is currently Peninsular Malaysia in Southeast Asia:

Political entities

* British Malaya (1826–1957), a loose collection of the British colony of the Straits ...

before the Japanese overran Singapore. Force 136 took over its surviving staff and operations.

New York City also had a branch office, formally titled British Security Coordination

British Security Co-ordination (BSC) was a covert organisation set up in New York City by the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) in May 1940 upon the authorisation of the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill.

Its purpose was to investigate ...

, and headed by the Canadian businessman Sir William Stephenson. This office, located at Room 3603, 630 Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major and prominent thoroughfare in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It stretches north from Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village to West 143rd Street in Harlem. It is one of the most expensive shopping stre ...

, Rockefeller Center, coordinated the work of SOE, SIS and MI5 with the American FBI and Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

.

Aims

As with its leadership and organisation, the aims and objectives of SOE changed throughout the war, although they revolved around sabotaging and subverting the Axis war machines through indirect methods. SOE occasionally carried out operations with direct military objectives, such as Operation Harling, originally designed to cut one of the Axis supply lines to their troops fighting in North Africa. They also carried out some high-profile operations aimed mainly at the morale both of the Axis and occupied nations, such as Operation Anthropoid, the assassination in Prague of Reinhard Heydrich. In general also, SOE's objectives were to foment mutual hatred between the population of Axis-occupied countries and the occupiers, and to force the Axis to expend manpower and resources on maintaining their control of subjugated populations. Dalton's early enthusiasm for fomenting widespread strikes, civil disobedience and nuisance sabotage in Axis-occupied areas had to be curbed. Thereafter, there were two main aims, often mutually incompatible; sabotage of the Axis war effort, and the creation of secret armies which would rise up to assist the liberation of their countries when Allied troops arrived or were about to do so. It was recognised that acts of sabotage would bring about reprisals and increased Axis security measures which would hamper the creation of underground armies. As the tide of war turned in the Allies' favour, these underground armies became more important.Relationships

At the government level, SOE's relationships with theForeign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

were often difficult. On several occasions, various governments in exile protested at operations taking place without their knowledge or approval, provoking Axis reprisal

A reprisal is a limited and deliberate violation of international law to punish another sovereign state that has already broken them. Since the 1977 Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions (AP 1), reprisals in the laws of war are extremel ...

s against civilian populations, or complained about SOE's support for movements opposed to the exiled governments. SOE's activities also threatened relationships with neutral countries. SOE nevertheless generally adhered to the rule, ''"No bangs without Foreign Office approval."''

Early attempts at bureaucratic control of Jefferis's MIR(c) by the Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply (MoS) was a department of the UK government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. A separate ministry, however, was responsible for aircr ...

were eventually foiled by Churchill's intervention. Thereafter, the Ministry co-operated, though at arm's length, with Dudley Newitt's various supply and development departments. The Treasury were accommodating from the start and were often prepared to turn a blind eye to some of SOE's questionable activities.

With other military headquarters and commands, SOE cooperated fairly well with Combined Operations Headquarters during the middle years of the war, usually on technical matters as SOE's equipment was readily adopted by commandos and other raiders. This support was lost when Vice Admiral Louis Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

left Combined Operations, though by this time SOE had its own transport and had no need to rely on Combined Operations for resources. On the other hand, the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

* Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

*Admiralty, Tr ...

objected to SOE developing its own underwater vessels, and the duplication of effort this involved. The Royal Air Force, and in particular RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the strategic bombing of Germany in World War II. From 1942 onward, the British bo ...

under "Bomber" Harris were usually reluctant to allocate aircraft to SOE.

Towards the end of the war, as Allied forces began to liberate territories occupied by the Axis and in which SOE had established resistance forces, SOE also liaised with and to some extent came under the control of the Allied theatre commands. Relationships with Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF; ) was the headquarters of the Commander of Allied forces in north west Europe, from late 1943 until the end of World War II. U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the commander in SHAEF th ...

in north-west Europe (whose commander was General Dwight D. Eisenhower) and South East Asia Command (whose commander was Admiral Louis Mountbatten, already well known to SOE) were generally excellent. However, there were difficulties with the Commanders in Chief in the Mediterranean, partly because of the complaints over impropriety at SOE's Cairo headquarters during 1941 and partly because both the supreme command in the Mediterranean and SOE's establishments were split in 1942 and 1943, leading to divisions of responsibility and authority.

There was tension between SOE and SIS, which the Foreign Office controlled. Stewart Menzies, the chief of SIS, was aggrieved to lose control of Section D. Where SIS preferred placid conditions in which it could gather intelligence and work through influential persons or authorities, SOE was intended to create unrest and turbulence, and often backed anti-establishment organisations, such as the Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

s, in several countries. At one stage, SIS actively hindered SOE's attempts to infiltrate agents into enemy-occupied France.

Even before the United States joined the war, the head of the newly formed Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI), William J. Donovan

William Joseph "Wild Bill" Donovan (January 1, 1883 – February 8, 1959) was an American soldier, lawyer, intelligence officer and diplomat, best known for serving as the head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the Bur ...

, had received technical information from SOE and had arranged for some members of his organisation to undergo training at a camp

Camp may refer to:

Outdoor accommodation and recreation

* Campsite or campground, a recreational outdoor sleeping and eating site

* a temporary settlement for nomads

* Camp, a term used in New England, Northern Ontario and New Brunswick to descri ...

run by SOE in Oshawa in Canada. In early 1942, Donovan's organisation became the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

. SOE and OSS worked out respective areas of operation: OSS's exclusive sphere included China (including Manchuria), Korea and Australia, the Atlantic islands and Finland. SOE retained India, the Middle East and East Africa, and the Balkans. While the two services both worked in Western Europe, it was expected that SOE would be the leading partner.

In the middle of the war, the relations between SOE and OSS were not often smooth. They established a joint headquarters in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

but the officers of the two organisations working there refused to share information with each other. In the Balkans, and Yugoslavia especially, SOE and OSS several times worked at cross-purposes, reflecting their governments' differing (and changing) attitudes to the Partisans and Chetniks

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nationa ...

. However, in 1944 SOE and OSS successfully pooled their personnel and resources to mount Operation Jedburgh, providing large scale support to the French Resistance following the Normandy landings.

SOE had some nominal contact with the Soviet NKVD, but this was limited to a single liaison officer at each other's headquarters.

Locations

Baker Street

After working from temporary offices in Central London, the headquarters of SOE was moved on 31 October 1940 into

After working from temporary offices in Central London, the headquarters of SOE was moved on 31 October 1940 into 64 Baker Street

64 Baker Street is a commercial property in central London. It was the address of the headquarters of the Special Operations Executive.

History

The building was completed in the first half of the 20th century and, after becoming part of the Gover ...

(hence the nickname ''"the Baker Street Irregulars"''). Ultimately, SOE occupied much of the western side of Baker Street. "Baker Street" became the euphemistic way of referring to SOE. The precise nature of the buildings remained concealed; it had no entry in the telephone directories, and correspondence to external bodies bore service addresses; MO1 (SP) (a War Office branch), NID(Q) (Admiralty), AI10 (Air Ministry), or other fictitious bodies or civilian companies.

SOE maintained a large number of training, research and development or administrative centres. It was a joke that ''"SOE"'' stood for ''"Stately 'omes of England"'', after the large number of country houses and estates it requisitioned and used.

Production and trials

The establishments connected with experimentation and production of equipment were mainly concentrated in and aroundHertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

and were designated by roman numbers. The main weapons and devices research establishments were The Firs, the home of MD1, formerly MIR(C), near Aylesbury

Aylesbury ( ) is the county town of Buckinghamshire, South East England. It is home to the Roald Dahl Children's Gallery, David Tugwell`s house on Watermead and the Waterside Theatre. It is in central Buckinghamshire, midway between High Wy ...

in Buckinghamshire (although this was not formally part of SOE), and Station IX

Station IX (formerly known as the Inter-Services Research Bureau) was a secret British Special Operations Executive factory making special weapons and equipment during World War II.

The small Welbike paratrooper's motorcycle and the Welrod assass ...

at The Frythe

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

, a country house (and former private hotel) outside Welwyn Garden City where, under the cover name of ISRB (Inter Services Research Bureau), SOE developed radios, weapons, explosive devices and booby trap

A booby trap is a device or setup that is intended to kill, harm or surprise a human or another animal. It is triggered by the presence or actions of the victim and sometimes has some form of bait designed to lure the victim towards it. The trap m ...

s.

Section D originally had a research station at Bletchley Park, which also held the Government Code and Cipher School, until in November 1940 it was decided that it was unwise to conduct codebreaking and explosives experiments on the same site. The establishment moved to Aston House near Stevenage

Stevenage ( ) is a large town and borough in Hertfordshire, England, about north of London. Stevenage is east of junctions 7 and 8 of the A1(M), between Letchworth Garden City to the north and Welwyn Garden City to the south. In 1946, Stevena ...

in Hertfordshire and was renamed Station XII

Station may refer to:

Agriculture

* Station (Australian agriculture), a large Australian landholding used for livestock production

* Station (New Zealand agriculture), a large New Zealand farm used for grazing by sheep and cattle

** Cattle statio ...

. It originally conducted research and development but from 1941 it became a production, storage and distribution centre for devices already developed.

Station XV, at the Thatched Barn

The Thatched Barn was a two-storey mock-Tudor hotel built in the 1930s on the Barnet by-pass in Borehamwood, Hertfordshire, England. It was bought by holiday camp founder, Billy Butlin, before being requisitioned as Station XV by the Special Opera ...

near Borehamwood, was devoted to camouflage, which usually meant equipping agents with authentic local clothing and personal effects. Various sub-stations in London were also involved in this task. Station XV and other camouflage sections also devised methods of hiding weapons, explosives or radios in innocuous-seeming items.

Agents also needed identity papers, ration cards, currency and so on. Station XIV, at Briggens House

Briggens House is a Grade II listed 18th-century house and parklands near the village of Roydon, Essex, England. It has a number of features from the garden designer Charles Bridgeman from 1720. There are also some remains of the pleasure garden ...

near Roydon in Essex, was originally the home of STS38, a training facility for Polish saboteurs, ) who set up their own forgery section. As the work expanded, it became the central forgery department for SOE and the Poles eventually moved out on 1 April 1942. The technicians at Station XIV included a number of ex-convicts.

Training and operations

The training establishments, and properties used by country sections, were designated by Arabic numbers and were widely distributed. The initial training centres of the SOE were at country houses such as Wanborough Manor,Guildford

Guildford ()

is a town in west Surrey, around southwest of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The name "Guildf ...

. Agents destined to serve in the field underwent commando training at Arisaig in Scotland, where they were taught armed and unarmed combat skills by William E. Fairbairn

Lieutenant-Colonel William Ewart Fairbairn (; 28 February 1885 – 20 June 1960) was a British Royal Marine and police officer. He developed hand-to-hand combat methods for the Shanghai Police during the interwar period, as well as for the all ...

and Eric A. Sykes

Major Eric Anthony Sykes (5 February 1883 – 12 May 1945), born Eric Anthony Schwabe, was a soldier and firearms expert. He is most famous for his work with William E. Fairbairn in the development of the eponymous Fairbairn–Sykes fighting kni ...

, former Inspectors in the Shanghai Municipal Police. Those who passed this course received parachute

A parachute is a device used to slow the motion of an object through an atmosphere by creating drag or, in a ram-air parachute, aerodynamic lift. A major application is to support people, for recreation or as a safety device for aviators, who ...

training by STS 51 and 51a situated near Altrincham, Cheshire with the assistance of No.1 Parachute Training School RAF, at RAF Ringway (which later became Manchester Airport

Manchester Airport is an international airport in Ringway, Manchester, England, south-west of Manchester city centre. In 2019, it was the third busiest airport in the United Kingdom in terms of passenger numbers and the busiest of those n ...

). They then attended courses in security and Tradecraft

Tradecraft, within the intelligence community, refers to the techniques, methods and technologies used in modern espionage (spying) and generally, as part of the activity of intelligence assessment. This includes general topics or techniques ( ...

at Group B schools around Beaulieu in Hampshire. Finally, depending on their intended role, they received specialist training in skills such as demolition

Demolition (also known as razing, cartage, and wrecking) is the science and engineering in safely and efficiently tearing down of buildings and other artificial structures. Demolition contrasts with deconstruction, which involves taking a ...

techniques or Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

telegraphy at various country houses in England.

SOE's Cairo branch established a commando and parachute training school numbered STS 102 at Ramat David

Ramat David ( he, רָמַת דָּוִד, ''lit.'' David Heights) is a kibbutz in northern Israel. Located in the Jezreel Valley near Ramat David Airbase, it falls under the jurisdiction of Jezreel Valley Regional Council. In it had a population ...

near Haifa. This school trained agents who joined SOE from among the armed forces stationed in the Middle East, and also members of the Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling and in 1950, it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-terro ...

and Greek Sacred Squadron.

A commando training centre similar to Arisaig and run by Fairbairn was later set up at Oshawa

Oshawa ( , also ; 2021 population 175,383; CMA 415,311) is a city in Ontario, Canada, on the Lake Ontario shoreline. It lies in Southern Ontario, approximately east of Downtown Toronto. It is commonly viewed as the eastern anchor of the G ...

, for Canadian members of SOE and members of the newly created American organisation, the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

.

Agents

A variety of people from all classes and pre-war occupations served SOE in the field. The backgrounds of agents in F Section, for example, ranged from aristocrats such as Polish-born Countess Krystyna Skarbek, andNoor Inayat Khan

Noor-un-Nisa Inayat Khan, GC (1 January 1914 – 13 September 1944), also known as Nora Inayat-Khan and Nora Baker, was a British resistance agent in France in World War II who served in the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The purpose of S ...

, the daughter of an Indian Sufi leader, to working-class people such as Violette Szabo

Violette Reine Elizabeth Szabo, GC (née Bushell; 26 June 1921 – February 1945) was a British-French Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent during the Second World War and a posthumous recipient of the George Cross. On her second mission i ...

and Michael Trotobas, with some even reputedly from the criminal underworld. Some of them were recruited by word of mouth among the acquaintances of SOE's officers, others responded to routine trawls of the armed forces for people with unusual languages or other specialised skills.

In most cases, the primary quality required of an agent was a deep knowledge of the country in which he or she was to operate, and especially its language, if the agent was to pass as a native of the country. Dual nationality was often a prized attribute. This was particularly so of France. In other cases, especially in the Balkans, a lesser degree of fluency was required as the resistance groups concerned were already in open rebellion and a clandestine existence was unnecessary. A flair for diplomacy combined with a taste for rough soldiering was more necessary. Some regular army officers proved adept as envoys, although others (such as the former diplomat Fitzroy Maclean or the classicist Christopher Woodhouse) were commissioned only during wartime.

Several of SOE's agents were from the Jewish Parachutists of Mandate Palestine

The Jewish Parachutists of Mandate Palestine were a group of 250 Jewish men and women from Mandate Palestine who volunteered for operations run by British organisations MI9 and the Special Operations Executive (SOE) which involved parachuting int ...

, many of whom were already Émigrés from Nazi or other oppressive or anti-semitic regimes in Europe. Thirty-two of them served as agents in the field, seven of whom were captured and executed.

Exiled or escaped members of the armed forces of some occupied countries were obvious sources of agents. This was particularly true of Norway and the Netherlands. In other cases (such as Frenchmen owing loyalty to Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

and especially the Poles), the agents' first loyalty was to their leaders or governments in exile, and they treated SOE only as a means to an end. This could occasionally lead to mistrust and strained relations in Britain.

The organisation was prepared to ignore almost any contemporary social convention in its fight against the Axis. It employed known homosexuals, people with criminal records (some of whom taught skills such as picking locks) or bad conduct records in the armed forces, Communists and anti-British nationalists. Some of these might have been considered a security risk, but no known case exists of an SOE agent wholeheartedly going over to the enemy. The Frenchman, Henri Déricourt

Henri Déricourt (2 September 1909 − 21 November 1962), code named Gilbert and Claude, was a French agent in 1943 and 1944 for the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive organization during World War II. The purpose of SOE was ...

, is widely regarded as a traitor, but he was exonerated by a war crimes court, and some have claimed he was acting under secret orders from SOE or MI6.

SOE was also far ahead of contemporary attitudes in its use of women in armed combat. Although women were first considered only as couriers in the field or as wireless operators or administrative staff in Britain, those sent into the field were trained to use weapons and in unarmed combat. Most were commissioned into either the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) or the Women's Auxiliary Air Force. Women often assumed leadership roles in the field. Pearl Witherington

Cecile Pearl Witherington Cornioley, (24 June 1914 – 24 February 2008), code names Marie and Pauline, was an agent in France for the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) during the Second World War. The purpose of ...

became the organiser (leader) of a highly successful resistance network in France. Early in the war, American Virginia Hall

Virginia Hall Goillot DSC, Croix de Guerre, (April 6, 1906 – July 8, 1982), code named Marie and Diane, was an American who worked with the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the American Office of St ...

functioned as the unofficial nerve center of several SOE networks in Vichy France. Many women agents such as Odette Hallowes or Violette Szabo

Violette Reine Elizabeth Szabo, GC (née Bushell; 26 June 1921 – February 1945) was a British-French Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent during the Second World War and a posthumous recipient of the George Cross. On her second mission i ...

were decorated for bravery, posthumously in Szabo's case. Of SOE's 41 (or 39 in some estimates) female agents serving in Section F (France) sixteen did not survive with twelve killed or executed in Nazi concentration camps.

Communications

Radio

Most of the resistance networks which SOE formed or liaised with were controlled by radio directly from Britain or one of SOE's subsidiary headquarters. All resistance circuits contained at least one wireless operator, and all drops or landings were arranged by radio, except for some early exploratory missions sent "blind" into enemy-occupied territory.

At first, SOE's radio traffic went through the SIS-controlled radio station at Bletchley Park. From 1 June 1942 SOE used its own transmitting and receiving stations at

Most of the resistance networks which SOE formed or liaised with were controlled by radio directly from Britain or one of SOE's subsidiary headquarters. All resistance circuits contained at least one wireless operator, and all drops or landings were arranged by radio, except for some early exploratory missions sent "blind" into enemy-occupied territory.

At first, SOE's radio traffic went through the SIS-controlled radio station at Bletchley Park. From 1 June 1942 SOE used its own transmitting and receiving stations at Grendon Underwood

Grendon Underwood is a village and civil parish in west Buckinghamshire, England, near the border with Oxfordshire. The village sits between Woodham and Edgcott, near the Roman road Akeman Street (now part of the A41), and around north-west o ...

in Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-ea ...

and Poundon

Poundon is a hamlet and a civil parish in Aylesbury Vale district in Buckinghamshire, England. It is located near the Oxfordshire border, about four miles northeast of Bicester, three miles southwest of Steeple Claydon.

The hamlet name is Anglo ...

nearby, as the location and topography were suitable. Teleprinters linked the radio stations with SOE's HQ in Baker Street. Operators in the Balkans worked to radio stations in Cairo.

SOE was highly dependent upon the security of radio transmissions, involving three factors: the physical qualities and capabilities of the radio sets, the security of the transmission procedures and the provision of proper cipher

In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is ''encipherment''. To encipher or encode i ...

s.

SOE's first radios were supplied by SIS. They were large, clumsy and required large amounts of power. SOE acquired a few, much more suitable, sets from the Poles in exile, but eventually designed and manufactured their own, such as the Paraset

The Paraset was a small, low-power, thermionic valve, CW-only radio transmitter- receiver supplied to the resistance groups in France, Belgium and the Netherlands during World War II.

History

The Paraset was one of the first successful miniatu ...

, under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel F. W. Nicholls of the Royal Corps of Signals

The Royal Corps of Signals (often simply known as the Royal Signals – abbreviated to R SIGNALS or R SIGS) is one of the combat support arms of the British Army. Signals units are among the first into action, providing the battlefield communi ...

who had served with Gubbins between the wars. The A Mk III, with its batteries and accessories, weighed only , and could fit into a small attache case, although the B Mk II, otherwise known as the B2, which weighed , was required to work over ranges greater than about .

Operating procedures were insecure at first. Operators were forced to transmit verbose messages on fixed frequencies and at fixed times and intervals. This allowed German direction finding teams time to triangulate their positions. After several operators were captured or killed, procedures were made more flexible and secure. The SOE wireless operators were also known as "The Pianists".

As with their first radio sets, SOE's first ciphers were inherited from SIS. Leo Marks

Leopold Samuel Marks, (24 September 1920 – 15 January 2001) was an English writer, screenwriter, and cryptographer. During the Second World War he headed the codes office supporting resistance agents in occupied Europe for the secret Special ...

, SOE's chief cryptographer, was responsible for the development of better codes to replace the insecure poem code

The poem code is a simple, and insecure, cryptographic method which was used during World War II by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) to communicate with their agents in Nazi-occupied Europe.

The method works by the sender and rece ...

s. Eventually, SOE settled on single use ciphers, printed on silk. Unlike paper, which would be given away by rustling, silk would not be detected by a casual search if it was concealed in the lining of clothing.

BBC

The BBC also played its part in communications with agents or groups in the field. During the war, it broadcast to almost all Axis-occupied countries, and was avidly listened to, even at risk of arrest. The BBC included various "personal messages" in its broadcasts, which could include lines of poetry or apparently nonsensical items. They could be used to announce the safe arrival of an agent or message in London for example, or could be instructions to carry out operations on a given date. These were used for example to mobilise the resistance groups in the hours beforeOperation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The operat ...

.

Other methods

In the field, agents could sometimes make use of the postal services, though these were slow, not always reliable and letters were almost certain to be opened and read by the Axis security services. In training, agents were taught to use a variety of easily available substances to make invisible ink, though most of these could be detected by a cursory examination, or to hide coded messages in apparently innocent letters. The telephone services were even more certain to be intercepted and listened to by the enemy, and could be used only with great care. The most secure method of communication in the field was by courier. In the earlier part of the war, most women sent as agents in the field were employed as couriers, on the assumption that they would be less likely to be suspected of illicit activities.Equipment

Weapons

Although SOE used some suppressed weapons such as the De Lisle carbine and theWelrod

The Welrod is a British bolt action, Magazine (firearms), magazine fed, suppressor, suppressed pistol devised during the Second World War by Major Hugh Reeves at the Inter-Services Research Bureau (later Station IX). Station IX, being based near ...

(specifically developed for SOE at Station IX), it took the view that weapons issued to resisters should not require extensive training in their use, or need careful maintenance. The crude and cheap Sten was a favourite. For issue to large forces such as the Yugoslav Partisans, SOE used captured German or Italian weapons. These were available in large quantities after the Tunisian and Sicilian campaigns and the surrender of Italy, and the partisans could acquire ammunition for these weapons (and the Sten) from enemy sources.

SOE also adhered to the principle that resistance fighters would be handicapped rather than helped by heavy equipment such as mortars or anti-tank guns

Anti-tank warfare originated from the need to develop technology and tactics to destroy tanks during World War I. Since the Triple Entente deployed the first tanks in 1916, the German Empire developed the first anti-tank weapons. The first devel ...

. These were awkward to transport, almost impossible to conceal and required skilled and highly trained operators. Later in the war however, when resistance groups staged open rebellions against enemy occupation, some heavy weapons were dispatched, for example to the Maquis du Vercors. Weapons such as the British Army's standard Bren light machine gun were also supplied in such cases.

Most SOE agents received training on captured enemy weapons before being sent into enemy-occupied territory. Ordinary SOE agents were also armed with handguns acquired abroad, such as, from 1941, a variety of US pistols, and a large quantity of the Spanish Llama .38 ACP

The .38 ACP ( Automatic Colt Pistol), also known as the .38 Auto or 9x23mmSR, is a semi-rimmed pistol cartridge that was introduced at the turn of the 20th century for the John Browning-designed Colt M1900. It was first used in Colt's Model ...

in 1944. Such was SOE's demand for weapons, a consignment of 8,000 Ballester–Molina

The Ballester–Molina is a pistol designed and built by the Argentine company ''Hispano Argentina Fábrica de Automóviles SA'' (HAFDASA). From 1938 to 1940 it bore the name Ballester–Rigaud.

History

The Ballester–Molina was designed to of ...

.45 calibre weapons was purchased from Argentina, apparently with the mediation of the US.

SOE agents were issued with the Fairbairn–Sykes fighting knife also issued to Commandos. For specialised operations or use in extreme circumstances, SOE issued small fighting knives which could be concealed in the heel of a hard leather shoe or behind a coat lapel. Given the likely fate of agents captured by the Gestapo, SOE also disguised suicide pills as coat buttons.

Sabotage

SOE developed a wide range of explosive devices for sabotage, such aslimpet mine

A limpet mine is a type of naval mine attached to a target by magnets. It is so named because of its superficial similarity to the shape of the limpet, a type of sea snail that clings tightly to rocks or other hard surfaces.

A swimmer or diver m ...

s, shaped charges and time fuses, which were also widely used by commando units. Most of these devices were designed and produced at The Firs. The Time Pencil

A pencil detonator or time pencil is a time fuze designed to be connected to a detonator or short length of safety fuse. They are about the same size and shape as a pencil, hence the name. They were introduced during World War II and developed at ...

, invented by Commander A.J.G. Langley, the first commandant of Station XII at Aston was used to give a saboteur time to escape after setting a charge and was far simpler to carry and use than lighted fuses or electrical detonators. It relied on crushing an internal vial of acid which then corroded a retaining wire, which sometimes made it inaccurate in cold or hot conditions. Later the L-Delay, which instead allowed a lead retaining wire to "creep" until it broke and was less affected by the temperature, was introduced.

SOE pioneered the use of plastic explosive. (The term "plastique" comes from plastic explosive packaged by SOE and originally destined for France but taken to the United States instead.) Plastic explosive could be shaped and cut to perform almost any demolition task. It was also inert and required a powerful detonator to cause it to explode, and was therefore safe to transport and store. It was used in everything from car bomb

A car bomb, bus bomb, lorry bomb, or truck bomb, also known as a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED), is an improvised explosive device designed to be detonated in an automobile or other vehicles.

Car bombs can be roughly divided ...

s, to exploding rats designed to destroy coal-fired boilers.

Other, more subtle sabotage methods included lubricant

A lubricant (sometimes shortened to lube) is a substance that helps to reduce friction between surfaces in mutual contact, which ultimately reduces the heat generated when the surfaces move. It may also have the function of transmitting forces, t ...

s laced with grinding materials, intended for introduction into vehicle oil systems, railway wagon

A railroad car, railcar (American and Canadian English), railway wagon, railway carriage, railway truck, railwagon, railcarriage or railtruck (British English and UIC), also called a train car, train wagon, train carriage or train truck, is a ...

axle box

A bogie or railroad truck holds the wheel sets of a rail vehicle.

Axlebox

An ''axle box'', also known as a ''journal box'' in North America, is the mechanical subassembly on each end of the axles under a railway wagon, coach or locomotive; ...

es, etc., incendiaries disguised as innocuous objects, explosive material concealed in coal piles to destroy locomotives, and land mines disguised as cow or elephant dung. On the other hand, some sabotage methods were extremely simple but effective, such as using sledgehammers to crack cast-iron mountings for machinery.

Submarines

Station IX developed several miniature submersible craft. The Welman submarine and '' Sleeping Beauty'' were offensive weapons, intended to place explosive charges on or adjacent to enemy vessels at anchor. The Welman was used once or twice in action, but without success. TheWelfreighter

The Welfreighter was a Second World War British midget submarine developed by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) for the purpose of landing and supplying agents behind enemy lines. It only saw action once and was not particularly successful ...

was intended to deliver stores to beaches or inlets, but it too was unsuccessful.

A sea trials unit was set up in West Wales at Goodwick

Goodwick (; cy, Wdig) is a coastal town in Pembrokeshire, Wales, immediately west of its twin town of Fishguard.

Fishguard and Goodwick form a community that wraps around Fishguard Bay. As well as the two towns, it consists of Dyffryn, Stop-and ...

, by Fishguard (station IXa) where these craft were tested. In late 1944 craft were dispatched to Australia to the Allied Intelligence Bureau (SRD), for tropical testing.

Other

SOE also revived some medieval devices, such as the caltrop, which could be used to burst the tyres of vehicles or injure foot soldiers and crossbows powered by multiple rubber bands to shoot incendiary bolts. There were two types, known as ''"Big Joe"'' and ''"Lil Joe"'' respectively. They had tubular alloy skeleton stocks and were designed to be collapsible for ease of concealment. An important section of SOE was Operational Research, which worked mostly from Station IX but also called on the facilities of Station XII and HQ. It operated through the User Trials Section and later the Air Supply Research Section and was formally established in August 1943. The section had the responsibility both for issuing formal requirements and specifications to the relevant development and production sections, and for testing prototypes of the devices under field conditions. It ensured that operational requirements were properly assessed, trials conducted, and quality monitored. Over the period from 1 November 1943 to 1 November 1944, the section tested 78 devices. Some of these were weapons such as theSleeve gun

A sleeve ( ang, slīef, a word allied to ''slip'', cf. Dutch ) is the part of a garment that covers the arm, or through which the arm passes or slips.

The sleeve is a characteristic of fashion seen in almost every country and time period, acro ...

or fuses or adhesion devices to be used in sabotage, others were utility objects such as waterproof containers for stores to be dropped by parachute, or night glasses (lightweight binoculars with plastic lenses). Of the devices tested, 47% were accepted for use with little or no modification, 31% were accepted only after considerable modification and the remaining 22% were rejected.

Before SOE's research and development procedures were formalised in 1943, a variety of more or less useful devices were developed. Some of the more imaginative devices invented by SOE included exploding pens with enough explosive power to blast a hole in the bearer's body, or guns concealed in tobacco pipes, though there is no record of any of these being used in action. Station IX developed a miniature folding motorbike (the '' Welbike'') for use by parachutists, though this was noisy and conspicuous, used scarce petrol and was of little use on rough ground.

Transport

The continent of Europe was largely closed to normal travel. Although it was possible in some cases to cross frontiers from neutral countries such as Spain or Sweden, it was slow and there were problems over violating these countries' neutrality. SOE had to rely largely on its own air or sea transport for movement of people, arms and equipment.Air

SOE had mostly to rely on the RAF for its planes. It was engaged in disputes with the RAF from its early days. In January 1941, an intended ambush (Operation Savanna

Operation Savanna (or Operation Savannah) was the first insertion of Special Operations Executive, SOE trained Free French paratroops into German-occupied France during World War II.

This SOE mission, requested by the Air Ministry, was to ambu ...

) against the aircrew of a German "pathfinder" air group near Vannes in Brittany was thwarted when Air Vice Marshal Charles Portal

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Charles Frederick Algernon Portal, 1st Viscount Portal of Hungerford, (21 May 1893 – 22 April 1971) was a senior Royal Air Force officer. He served as a bomber pilot in the First World War, and rose to become fi ...

, the Chief of the Air Staff, objected on moral grounds to parachuting what he regarded as assassins, although Portal's objections were later overcome and ''Savanna'' was mounted, unsuccessfully. From 1942, when Air Marshal Arthur Harris

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Travers Harris, 1st Baronet, (13 April 1892 – 5 April 1984), commonly known as "Bomber" Harris by the press and often within the RAF as "Butch" Harris, was Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief (AOC-in-C) ...

(''"Bomber Harris"'') became the Commander-in-Chief of RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the strategic bombing of Germany in World War II. From 1942 onward, the British bo ...

, he consistently resisted the diversion of the most capable types of bombers to SOE purposes.

SOE's first aircraft were two Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys belonging to 419 Flight RAF, which was formed in September 1940. In 1941, the flight was expanded to become No. 138 Squadron RAF

No. 138 Squadron RAF was a squadron of the Royal Air Force that served in a variety of roles during its career, last disbanded in 1962. It was the first 'V-bomber' squadron of the RAF, flying the Vickers Valiant between 1955 and 1962.

History

...

. In February 1942, they were joined by No. 161 Squadron RAF

No. 161 (Special Duties) Squadron was a highly secretive unit of the Royal Air Force, performing missions as part of the Royal Air Force Special Duties Service. It was tasked with missions of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Secr ...

. 161 Squadron flew agent insertions and pick-ups, while 138 Squadron delivered arms and stores by parachute. "C" flight from No. 138 Squadron later became No. 1368 Flight of the Polish Air Force

The Polish Air Force ( pl, Siły Powietrzne, , Air Forces) is the aerial warfare branch of the Polish Armed Forces. Until July 2004 it was officially known as ''Wojska Lotnicze i Obrony Powietrznej'' (). In 2014 it consisted of roughly 16,425 mil ...

, which joined No. 624 Squadron flying Halifaxes in the Mediterranean. By the later stages of the war several United States Army Air Forces squadrons were operating Douglas C-47 Skytrains in the Mediterranean, although by this time their operations had passed from SOE proper to the "Balkan Air Terminal Service". Three Special Duties squadrons operated in the Far East using a variety of aircraft, including the very long-range Consolidated B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models des ...

.

RAF Tempsford

Nos. 161 and 138 Squadrons were based atRAF Tempsford

RAF Tempsford is a former Royal Air Force station located north east of Sandy, Bedfordshire, Sandy, Bedfordshire, England and south of St. Neots, Cambridgeshire, England.

As part of the Royal Air Force Special Duty Service, the airfield wa ...