Soviet rocketry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Soviet rocketry commenced in 1921 with development of

Soviet rocketry commenced in 1921 with development of

The research continued from 1933 by the

The research continued from 1933 by the

/ref> Glushko proposed to use energy in electric explosion of metals to create rocket propulsion. In the early 1930s the world's first example of an electrothermal rocket engine was created. This early work by GDL has been steadily carried on and electric rocket engines were used in the 1960s on board the

Concurrently with the work at GDL

Concurrently with the work at GDL  GIRD began as the Jet Engine Section of a larger civil defense organization known as the Society for the Promotion of Defense and Aerochemical Development (

GIRD began as the Jet Engine Section of a larger civil defense organization known as the Society for the Promotion of Defense and Aerochemical Development (

As a young adult,

As a young adult,

The Katyusha rocket launchers were top secret in the beginning of World War II, however only forty launchers had been built. A special unit of the NKVD troops was raised to operate them. On July 14, 1941, an experimental artillery battery of seven launchers was first used in battle at Rudnya in

The Katyusha rocket launchers were top secret in the beginning of World War II, however only forty launchers had been built. A special unit of the NKVD troops was raised to operate them. On July 14, 1941, an experimental artillery battery of seven launchers was first used in battle at Rudnya in

The German invasion of Russia in the summer of 1941 led to an acute sense of urgency for the Soviets to develop practical rocket-powered aircraft. The Russian conventional air force was dominated by the

The German invasion of Russia in the summer of 1941 led to an acute sense of urgency for the Soviets to develop practical rocket-powered aircraft. The Russian conventional air force was dominated by the

During WWII

During WWII

''Rockets and People: Volume II''

Washington, D.C.: NASA, 2006. Accessed April 7, 2016. * Chertok, Boris Evseyevich. ''Rockets and People: Volume IV: The Moon Race''. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NASA History Office, Office of External Affairs, 2005. * Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition. ''Wernher Von Braun''. June 2015. Accessed April 8, 2016. * Darrin, Ann Garrison and O'Leary, Beth Laura. ''Handbook of Space Engineering, Archaeology, and Heritage''. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, 2009. * Faure, Gunter, and Mensing, Teresa M. ''Introduction to Planetary Science: The Geological Perspective.'' Dordrecht: Springer, 2007.

''Encyclopedia Astronautica Glushko.'' Web, Accessed 08 Apr. 2016. * Hagler, Gina. ''Modeling Ships and Space Craft: The Science and Art of Mastering the Oceans and Sky''. New York: Springer, 2013. * Harvey, Brian. ''Russian Planetary Exploration: History, Development, Legacy, Prospects''. Berlin: Springer, 2007.

Florida International University. Accessed 08 Apr. 2016. * "Konstantin Tsiolkovsky." NASA. Accessed 08 Apr. 2016.

* Lethbridge, Cliff. "History of Rocketry Chapter 6: 1945 to the Creation of NASA." ''Spaceline''. (2000). Accessed April 7, 2016. http://www.spaceline.org/history/6.html. * MSFC History Office: NASA

Accessed April 7, 2016. * {{cite journal , last1 = O'Brien , first1 = Jason L. , last2 = Sears , first2 = Christine E. , title = Victor or Villain? Wernher von Braun and the Space Race , journal = Social Studies , volume = 102 , issue = 2

''Russian Space Web.'' Web, Accessed 08 Apr. 2016.

"Yury Alekseyevich Gagarin."

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Rocket propulsion Space program of the Soviet Union Science and technology in the Soviet Union

Soviet rocketry commenced in 1921 with development of

Soviet rocketry commenced in 1921 with development of Solid-fuel rocket

A solid-propellant rocket or solid rocket is a rocket with a rocket engine that uses solid propellants ( fuel/oxidizer). The earliest rockets were solid-fuel rockets powered by gunpowder; they were used in warfare by the Arabs, Chinese, Persian ...

s, which resulted in the development of the Katyusha rocket launcher

The Katyusha ( rus, Катю́ша, p=kɐˈtʲuʂə, a=Ru-Катюша.ogg) is a type of rocket artillery first built and fielded by the Soviet Union in World War II. Multiple rocket launchers such as these deliver explosives to a target area ...

. Rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

scientists and engineers, particularly Valentin Glushko

Valentin Petrovich Glushko (russian: Валенти́н Петро́вич Глушко́; uk, Валентин Петрович Глушко, Valentyn Petrovych Hlushko; born 2 September 1908 – 10 January 1989) was a Soviet engineer and the m ...

and Sergei Korolev

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (russian: Сергей Павлович Королёв, Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov, sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ kərɐˈlʲɵf, Ru-Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.ogg; ukr, Сергій Павлович Корольов, ...

, contributed to the development of Liquid-fuel rocket

A liquid-propellant rocket or liquid rocket utilizes a rocket engine that uses liquid rocket propellant, liquid propellants. Liquids are desirable because they have a reasonably high density and high Specific impulse, specific impulse (''I''sp). T ...

s, which were first used for fighter aircraft

Fighter aircraft are fixed-wing military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air superiority of the battlespace. Domination of the airspace above a battlefield ...

and later for ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are guided only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles stay within the ...

s, and space exploration

Space exploration is the use of astronomy and space technology to explore outer space. While the exploration of space is carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration though is conducted both by robotic spacec ...

. Progress was greatly augmented by the reverse engineering of Nazi German

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

technology captured by westward-moving troops during the final days of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and the immediate period following, though after 1947 their influence was marginal. Developments continued in the 1950s with a variety of ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

s and resulted in the launch of Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

in 1957, the first artificial Earth satellite ever launched.

Origins

Russian involvement in rocketry began in 1903 whenKonstantin Tsiolkovsky

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (russian: Константи́н Эдуа́рдович Циолко́вский , , p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin ɪdʊˈardəvʲɪtɕ tsɨɐlˈkofskʲɪj , a=Ru-Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.oga; – 19 September 1935) ...

published a paper on liquid-propelled rockets (LPREs). Tsiolkovsky's efforts made significant advances in the use of liquid fuel. His work challenged traditional thought and sparked a revolution in science which embraced new ideas in rocket technology.

Solid Fuel: The first rockets

The first Soviet development of rockets was in 1921 when the Soviet military sanctioned the commencement of a small research laboratory to explore solid fuel rockets, led by Nikolai Tikhomirov, a chemical engineer and supported byVladimir Artemyev

Vladimir Andreyevich Artemyev (russian: Владимир Андреевич Артемьев) ( in Saint Petersburg - 11 September 1962 in Moscow) was a Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. ...

a Soviet engineer. Tikhomirov had commenced studying solid and Liquid-fueled rocket

A liquid-propellant rocket or liquid rocket utilizes a rocket engine that uses liquid propellants. Liquids are desirable because they have a reasonably high density and high specific impulse (''I''sp). This allows the volume of the propellant ta ...

s in 1894, and in 1915 he lodged a patent for "self-propelled aerial and water-surface mines." In 1928 the laboratory was renamed the Gas Dynamics Laboratory

Gas Dynamics Laboratory (GDL) (russian: Газодинамическая лаборатория) was the first Soviet research and development laboratory to focus on rocket technology. Its activities were initially devoted to the development o ...

(GDL). The First test-firing of a solid fuel rocket was carried out in March 1928, which flew for about 1,300 meters These rockets were used in 1931 for the world's first successful use of rockets to assist take-off of aircraft. Further developments were led by Georgy Langemak

Georgy Erikhovich Langemak (russian: Георгий Эрихович Лангемак; – 11 January 1938) was a Soviet engineer in the Soviet space program, working on rocket design applications. He is chiefly remembered for being the co ...

. and 1932 in-air test firings of RS-82 missiles from an Tupolev I-4

The Tupolev I-4 was a Soviet sesquiplane single-seat fighter. It was conceived in 1927 by Pavel Sukhoi as his first aircraft design for the Tupolev design bureau, and was the first Soviet all-metal fighter.

Design and development

After the first ...

aircraft armed with six launchers successfully took place.

The research continued from 1933 by the

The research continued from 1933 by the Reactive Scientific Research Institute

Reactive Scientific Research Institute (commonly known by the joint initialism RNII; russian: Реактивный научно-исследовательский институт, Reaktivnyy nauchno-issledovatel’skiy institut) was one of the ...

(RNII) with the development of the RS-82 and RS-132 rockets, including designing several variations for ground-to-air, ground-to-ground, air-to-ground and air-to-air combat. The earliest known use by the Soviet Air Force

The Soviet Air Forces ( rus, Военно-воздушные силы, r=Voyenno-vozdushnyye sily, VVS; literally "Military Air Forces") were one of the air forces of the Soviet Union. The other was the Soviet Air Defence Forces. The Air Forces ...

of aircraft-launched unguided anti-aircraft rockets in combat against heavier-than-air aircraft took place in August 1939, during the Battle of Khalkhin Gol

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (russian: Бои на Халхин-Голе; mn, Халхын голын байлдаан) were the decisive engagements of the undeclared Soviet–Japanese border conflicts involving the Soviet Union, Mongolia, Ja ...

. In June 1938, the RNII began developing a multiple rocket launcher based on the RS-132 rocket. In August 1939, the completed product was the BM-13 / Katyusha rocket launcher. Towards the end of 1938 the first significant large scale testing of the rocket launchers took place, 233 rockets of various types were used. A salvo of rockets could completely straddle a target at a range of .

Electric rocket engines

On 15 May1929

This year marked the end of a period known in American history as the Roaring Twenties after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 ushered in a worldwide Great Depression. In the Americas, an agreement was brokered to end the Cristero War, a Catholic ...

a section at GDL was created to develop electric rocket engines, headed by 23 year old Valentin Glushko

Valentin Petrovich Glushko (russian: Валенти́н Петро́вич Глушко́; uk, Валентин Петрович Глушко, Valentyn Petrovych Hlushko; born 2 September 1908 – 10 January 1989) was a Soviet engineer and the m ...

,Brief chronology of rocket engine building in the USSR/ref> Glushko proposed to use energy in electric explosion of metals to create rocket propulsion. In the early 1930s the world's first example of an electrothermal rocket engine was created. This early work by GDL has been steadily carried on and electric rocket engines were used in the 1960s on board the

Voskhod 1

Voskhod 1 (russian: Восход-1, lit=Sunrise-1) was the seventh crewed Soviet space flight. Flown by cosmonauts Vladimir Komarov, Konstantin Feoktistov, and Boris Yegorov, it launched 12 October 1964, and returned on the 13th. Voskhod 1 was ...

spacecraft and Zond-2

Zond 2 was a Soviet space probe, a member of the Zond program, and was the sixth Soviet spacecraft to attempt a flyby of Mars. (See Exploration of Mars) It was launched on November 30, 1964 at 13:12 UTC onboard Molniya 8K78 launch vehicle from ...

Venus probe.

Liquid Fuel: The early contribution

In 1931 Glushko was redirected to work on liquid propellant rocket engines. This resulted in the creation of ORM (from "Experimental Rocket Motor" in Russian) engines to . To increase the resource, various technical solutions were used: the jet nozzle had a spirally finned wall and was cooled by fuel components, curtain cooling was used for the combustion chamber and ceramic thermal insulation of the combustion chamber usingzirconium dioxide

Zirconium dioxide (), sometimes known as zirconia (not to be confused with zircon), is a white crystalline oxide of zirconium. Its most naturally occurring form, with a monoclinic crystalline structure, is the mineral baddeleyite. A dopant stabi ...

.heading=Gas-Dynamic Laboratory Nitric acid

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but older samples tend to be yellow cast due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available nitri ...

, solutions of nitric acid with froholic nitrogen, tetranitromethane

Tetranitromethane or TNM is an organic oxidizer with chemical formula . Its chemical structure consists of four nitro groups attached to one carbon atom. In 1857 it was first synthesised by the reaction of sodium cyanoacetamide with nitric acid.

...

, hypochloric acid and hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscous than water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usually as a dilute solution (3%� ...

were first proposed as an oxidizing agent. As a result of experiments, by the end of 1933, a high-boiling fuel from kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning "wax", and was regi ...

and nitric acid was selected as the most convenient in operation and industrial production. In 1931

Events

January

* January 2 – South Dakota native Ernest Lawrence invents the cyclotron, used to accelerate particles to study nuclear physics.

* January 4 – German pilot Elly Beinhorn begins her flight to Africa.

* January 22 – Sir I ...

self-igniting combustible and chemical ignition of fuel with gimbal engine suspension were proposed. For fuel supply in 1931-1932 fuel pumps operating from combustion chamber gases were developed. In 1933 a centrifugal turbopump unit for a rocket engine with a thrust of 3000 N was developed. A total of 100 bench tests of liquid-propellant rockets were conducted using various types of fuel, both low and high-boiling and thrust up to 300 kg was achieved.

Concurrently with the work at GDL

Concurrently with the work at GDL Friedrich Zander

Georg Arthur Constantin Friedrich Zander (also Tsander, russian: Фридрих Артурович Цандер, tr. ; lv, Frīdrihs Canders, – 28 March 1933), was a Baltic German pioneer of rocketry and spaceflight in the Russian Empire an ...

, a scientist and inventor, had begun work on the OR-1 experimental engine in 1929 while working at the Central Institute for Aircraft Motor Construction; It ran on compressed air and gasoline and Zander used it to investigate high-energy fuels including powdered metals mixed with gasoline. In September 1931 Zander formed the Moscow-based Group for the Study of Reactive Motion

The Moscow-based Group for the Study of Reactive Motion (also 'Group for the Investigation of Reactive Engines and Reactive Flight' and 'Jet Propulsion Study Group') (russian: Группа изучения реактивного движения, ...

, better known by its Russian acronym “GIRD”. Zander, who idolized Tsiolkovsky and the German rocket scientist Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and engineer. He is considered one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics, along with Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Konstantin Ts ...

, oversaw the development of Russia's first liquid fueled rocket, the GIRD 10. The rocket was launched successfully in 1933, and it reached an altitude of , but Zander died before the test took place. van Pelt, p. 120

GIRD began as the Jet Engine Section of a larger civil defense organization known as the Society for the Promotion of Defense and Aerochemical Development (

GIRD began as the Jet Engine Section of a larger civil defense organization known as the Society for the Promotion of Defense and Aerochemical Development (Osoaviakhim

The Society for the Assistance of Defense, Aircraft and Chemical Construction (russian:

Общество содействия обороне, авиационному и химическому строительству, romanized as ''Obshche ...

). GIRD's role was to deliver practical jet engine technology to be employed in aerial military applications. Although branches of GIRD were established in major cities all throughout the Soviet Union, the two most active branches were those in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

(MosGIRD, formed in January 1931) and in Leningrad (LenGIRD, formed in November 1931).

MosGIRD worked on the development of space research, liquid-propellant rockets, rocket design as it pertained to aircraft, and the construction of a supersonic wind tunnel (used for the aerodynamic testing of the aircraft that they developed), whereas LenGIRD developed solid-fuel rockets used for photographing the upper atmosphere, carrying flares, and atmospheric sounding.

Mikhail Klavdievich Tikhonravov

Mikhail Klavdievich Tikhonravov (July 29, 1900 – March 3, 1974) was a Soviet engineer who was a pioneer of spacecraft design and rocketry.

Mikhail Tikhonravov was born in Vladimir, Russia. He attended the Zhukovsky Air Force Academy from 1922 ...

, who would later supervise the design of Sputnik I

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

and the Luna programme

The Luna programme (from the Russian word "Luna" meaning "Moon"), occasionally called ''Lunik'' by western media, was a series of robotic spacecraft missions sent to the Moon by the Soviet Union between 1959 and 1976. Fifteen were successful, ...

, headed GIRD's 2nd Brigade, was responsible for the first Soviet liquid propelled rocket launch, the GIRD-9, on 17 August 1933, which reached an altitude of .

In January 1933 Zander began development of the GIRD-X rocket (Note: "X" is the Roman numeral 10). It was originally to use a metallic propellant, but after various metals had been tested without success it was designed without a metallic propellant, and was powered by the Project 10 engine which was first bench tested in March 1933. This design burned liquid oxygen and gasoline and was one of the first engines to be regeneratively cooled by the liquid oxygen, which flowed around the inner wall of the combustion chamber before entering it. Problems with burn-through during testing prompted a switch from gasoline to less energetic alcohol. The final missile, long by in diameter, had a mass of , and it was anticipated that it could carry a payload to an altitude of . The GIRD X rocket was launched on 25 November 1933 and flew to a height of 80 meters.

Early pioneers in the field began to postulate that liquid fuels were more powerful than solid fuels. Some of the early fuels used by these scientists were oxygen, alcohol, methane, hydrogen, or combinations of them. A bitter rivalry developed between the researchers of these institutes.

Reactive Scientific Research Institute

In order to obtain maximum military benefits, the Red Army's chief-of-staff Marshal Mikhail Tukhacheskii merged GIRD with the GDL to study both fuel types. The new group was calledReactive Scientific Research Institute

Reactive Scientific Research Institute (commonly known by the joint initialism RNII; russian: Реактивный научно-исследовательский институт, Reaktivnyy nauchno-issledovatel’skiy institut) was one of the ...

(RNII). When the two institutes combined, they brought together two of the most exceptional and successful engineers in the history of Soviet rocketry. Korolev teamed up with propulsion engineer Valentin Glushko

Valentin Petrovich Glushko (russian: Валенти́н Петро́вич Глушко́; uk, Валентин Петрович Глушко, Valentyn Petrovych Hlushko; born 2 September 1908 – 10 January 1989) was a Soviet engineer and the m ...

, and together they excelled in the rocket industry, pushing the Soviet Union ahead of the United States in the space race. Before merging, the GDL had conducted liquid fuel tests and used nitric acid, while the GIRD had been using liquid oxygen. A brilliant, though often confrontational Sergei Korolev

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (russian: Сергей Павлович Королёв, Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov, sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ kərɐˈlʲɵf, Ru-Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.ogg; ukr, Сергій Павлович Корольов, ...

, headed the GIRD when it merged into RNII

Reactive Scientific Research Institute (commonly known by the joint initialism RNII; russian: Реактивный научно-исследовательский институт, Reaktivnyy nauchno-issledovatel’skiy institut) was one of the ...

, and he was originally RNII's deputy director. Korolev's boss was a hard-nosed man from the GDL by the name of Kleimenov. Bitter in-fighting slowed the pace and quality of the research at RNII, but despite internal dissention, Korolev began to produce designs of missiles with liquid fueled engines. By 1932, RNII was using liquid oxygen

Liquid oxygen—abbreviated LOx, LOX or Lox in the aerospace, submarine and gas industries—is the liquid form of molecular oxygen. It was used as the oxidizer in the first liquid-fueled rocket invented in 1926 by Robert H. Goddard, an applica ...

with kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning "wax", and was regi ...

as a coolant as well as nitric acid

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but older samples tend to be yellow cast due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available nitri ...

and a hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic, and their odors are usually weak or ex ...

.

Applications in early aircraft

As a young adult,

As a young adult, Sergei Korolev

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (russian: Сергей Павлович Королёв, Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov, sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ kərɐˈlʲɵf, Ru-Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.ogg; ukr, Сергій Павлович Корольов, ...

(1907–1966) had always been fascinated by aviation. At college, his fascination towards rocketry and space travel grew. He became one of the most important rocket engineers of Soviet aircraft technology, and became "Chief Designer" of the Soviet space program. Sergei Korolev was a vitally important member of GIRD, and later became the head of the Soviet space program. Korolev would play a crucial role in both the launch of Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

in 1957, and the mission which put Yuri Gagarin

Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin; Gagarin's first name is sometimes transliterated as ''Yuriy'', ''Youri'', or ''Yury''. (9 March 1934 – 27 March 1968) was a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who became the first human to journey into outer space. Tr ...

in space in 1961.

In 1931, Korolev had come to Zander with a conceptual design for a rocket-powered aircraft

A rocket-powered aircraft or rocket plane is an aircraft that uses a rocket engine for propulsion, sometimes in addition to airbreathing jet engines. Rocket planes can achieve much higher speeds than similarly sized jet aircraft, but typicall ...

called the RP-1. This craft was essentially a glider, powered with one of GDL's rocket motors, the OR-2. The OR-2 was a rocket engine powered with gasoline and liquid oxygen, and produced a thrust of . In May 1932, about a year before Zander died, Korolev became the director of GIRD. At this point, he continued developing his design for the RP-1, an updated version called the RP-2, and another craft that he called the RP-218. The plan for the RP-218 called for a two-seat rocket powered plane, complete with a pressurized cabin, a retractable undercarriage, and equipment for high altitude research. The design was never realized, though, because at the time, there was not a rocket powerful enough and light enough to make the RP-218 practical.

Instead of pursuing the RP-218, in 1935, Korolev and RNII began developing the SK-9, a simple wooden two-seat glider which was to be used for testing rocket engines. The rear seat was replaced with tanks holding kerosene and nitric acid, and the OR-2 rocket motor was installed in the fuselage. The resulting craft was referred to as the RP-318. The RP-318 was tested numerous times with the engine installed, and was deemed ready for test flights in April 1938, but the plane's development halted when Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

severely damaged its progress. RNII was particularly affected with Director Kleymyonov and Chief Engineer Langemak arrested in November 1937, and later executed. Glushko was arrested in March 1938 and with many other leading engineers was imprisoned in the Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

. Korolev was arrested in June 1938 and sent to a forced labour camp in Kolyma in June 1939. However, due to the intervention by Andrei Tupolev

Andrei Nikolayevich Tupolev (russian: Андрей Николаевич Туполев; – 23 December 1972) was a Russian Empire, Russian and later Soviet Union, Soviet aeronautical engineer known for his pioneering aircraft designs as Di ...

, he was relocated to a prison for scientist and engineers in September 1940. From 1937 to 1944 no serious work was carried out on long range rockets as weapons.

The Soviets began to redesign the thrust chambers of their rocket engines, as well as investigate better ignition systems. These research endeavors were receiving more attention and funding as Europe began its escalation into the chaos of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The Soviet rocket program had developed engines with two-stage ignition and variable thrust nearly two years before Germany rolled out their Me 163

The Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet is a rocket-powered interceptor aircraft primarily designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt. It is the only operational rocket-powered fighter aircraft in history as well as ...

. However, the Soviet engine was only on gliders for testing, and was not available for full-powered flight. The engine's thrust was too low, and pressure build-up caused systemic failures.

Toward the end of 1938, work resumed on the RP-318 at the 'Scientific-Research Institute 3' (NII-3)N II-3, which was the new title for RNII. The aircraft was repaired and modified, with the addition of a new, more powerful engine to replace the OR-2. The new engine (the ORM-65) had been originally designed for a use in a single-launch cruise missile, but was adapted so that it could be employed in a multi-use aircraft. For comparison to the OR-2, the new ORM-65 could produce a variable thrust between . After extensive testing, on February 28, 1940, the new RP-318-1 was successfully tested in a full-powered flight; the craft attained a speed of , reached an altitude of , in 110 seconds of operation, and was landed safely when the fuel was exhausted. Although this was a momentous occasion in Russian jet development, further plans to enhance this aircraft were shelved, and when the German Army neared Moscow in August 1941, the RP-318-1 was burned to keep it away from the Germans.

World War II

Katyusha rocket launchers

The Katyusha rocket launchers were top secret in the beginning of World War II, however only forty launchers had been built. A special unit of the NKVD troops was raised to operate them. On July 14, 1941, an experimental artillery battery of seven launchers was first used in battle at Rudnya in

The Katyusha rocket launchers were top secret in the beginning of World War II, however only forty launchers had been built. A special unit of the NKVD troops was raised to operate them. On July 14, 1941, an experimental artillery battery of seven launchers was first used in battle at Rudnya in Smolensk Oblast

Smolensk Oblast (russian: Смоле́нская о́бласть, ''Smolenskaya oblast''; informal name — ''Smolenschina'' (russian: Смоле́нщина)) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative centre is the city of ...

of Russia, under the command of Captain Ivan Flyorov

Ivan Andreyevich Flyorov (russian: Иван Андреевич Флёров; 24 April 1905 – 7 October 1941), was a captain in the Red Army in command of the first battery of 8 '' Katyushas'' (BM-8), which was formed in Lipetsk and on 14 July 1 ...

, destroying a concentration of German troops with tanks, armored vehicles and trucks at the marketplace, causing massive German Army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

casualties and its retreat from the town in panic, see also in articles by a Russian military historian Andrey Sapronov, an eyewitness of the maiden launches. Following the success, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

organized new Guards mortar batteries for the support of infantry divisions. A battery's complement was standardized at four launchers. They remained under NKVD control until German ''Nebelwerfer

The Nebelwerfer (smoke mortar) was a World War II Nazi Germany, German series of weapons. They were initially developed by and assigned to the German Army (Wehrmacht), Wehrmacht's "smoke troops" (''Nebeltruppen''). Initially, two different mortar ...

'' rocket launchers became common later in the war.

On August 8, 1941, Stalin ordered the formation of eight special Guards mortar regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

s under the direct control of the Reserve of the Supreme High Command

The Reserve of the Supreme High Command (Russian: Резерв Верховного Главнокомандования; also known as the '' Stavka'' Reserve or RVGK ( ru , РВГК)) comprises reserve military formations and units; the Sta ...

(RVGK). Each regiment comprised three battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

s of three batteries, totalling 36 BM-13 or BM-8 launchers. Independent Guards mortar battalions were also formed, comprising 12 launchers in three batteries of four. By the end of 1941, there were eight regiments, 35 independent battalions, and two independent batteries in service, fielding a total of 554 launchers.

By the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

total production of rocket launchers reached about 10,000, with 12 million rockets of the RS type produced for the Soviet armed forces.

Rocket powered aircraft

The German invasion of Russia in the summer of 1941 led to an acute sense of urgency for the Soviets to develop practical rocket-powered aircraft. The Russian conventional air force was dominated by the

The German invasion of Russia in the summer of 1941 led to an acute sense of urgency for the Soviets to develop practical rocket-powered aircraft. The Russian conventional air force was dominated by the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

, with scores of their planes being shot down by individual German fighters. The Russians needed a superior weapon to counter the German air forces, and they looked to rocket-powered interceptor craft as the solution to their dilemma. In spring of 1941, Andrei Kostikov (the new director of N II-3, previously RN II) and Mikhail Tikhonravov

Mikhail Klavdievich Tikhonravov (July 29, 1900 – March 3, 1974) was a Soviet engineer who was a pioneer of spacecraft design and rocketry.

Mikhail Tikhonravov was born in Vladimir, Russia. He attended the Zhukovsky Air Force Academy from 1922 ...

began designing a new rocket-powered interceptor, the Kostikov 302.

The Kostikov 302 became the first Russian rocket plane that would have many features shared with modern fighter aircraft. It was built out of wood, with some aluminum, but it included a pressurized cockpit and retractable landing gear. Another key aspect of the Kostikov 302 was that it was equipped with hydraulic actuators, which allowed the pilot to fly the aircraft with more ease. These actuators, in effect the equivalent of power steering in a car, greatly reduced amount of force the pilots had to apply to control the plane. Because of the ongoing war with Germany, Russian officials strove to make the Kostikov aircraft a functional military asset as quickly as possible. This entailed outfitting it with armored glass, armored plates, several 20 mm cannons, and the option of a payload of either rockets or bombs under the wings. Although it had limited range, this aircraft became a serviceable tool for the purpose of brief forays, such as intercepting enemy aircraft. However, by 1944, the 302 was unable to reach Kostikov's performance requirements, in part because the engine technology was not keeping pace with the aircraft development.

The research teams made an important breakthrough in 1942: finally producing a tested and combat-ready rocket engine, the D-7-A-1100. This utilized a kerosene liquid fuel with a nitric acid

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but older samples tend to be yellow cast due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available nitri ...

oxidizer

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ). In other words, an oxid ...

. However, the Nazi invasion had the Soviet high command centered on other matters, and the engine was never produced for use. During World War II, there is no record of any liquid fueled weapons being either produced or designed.

German influence

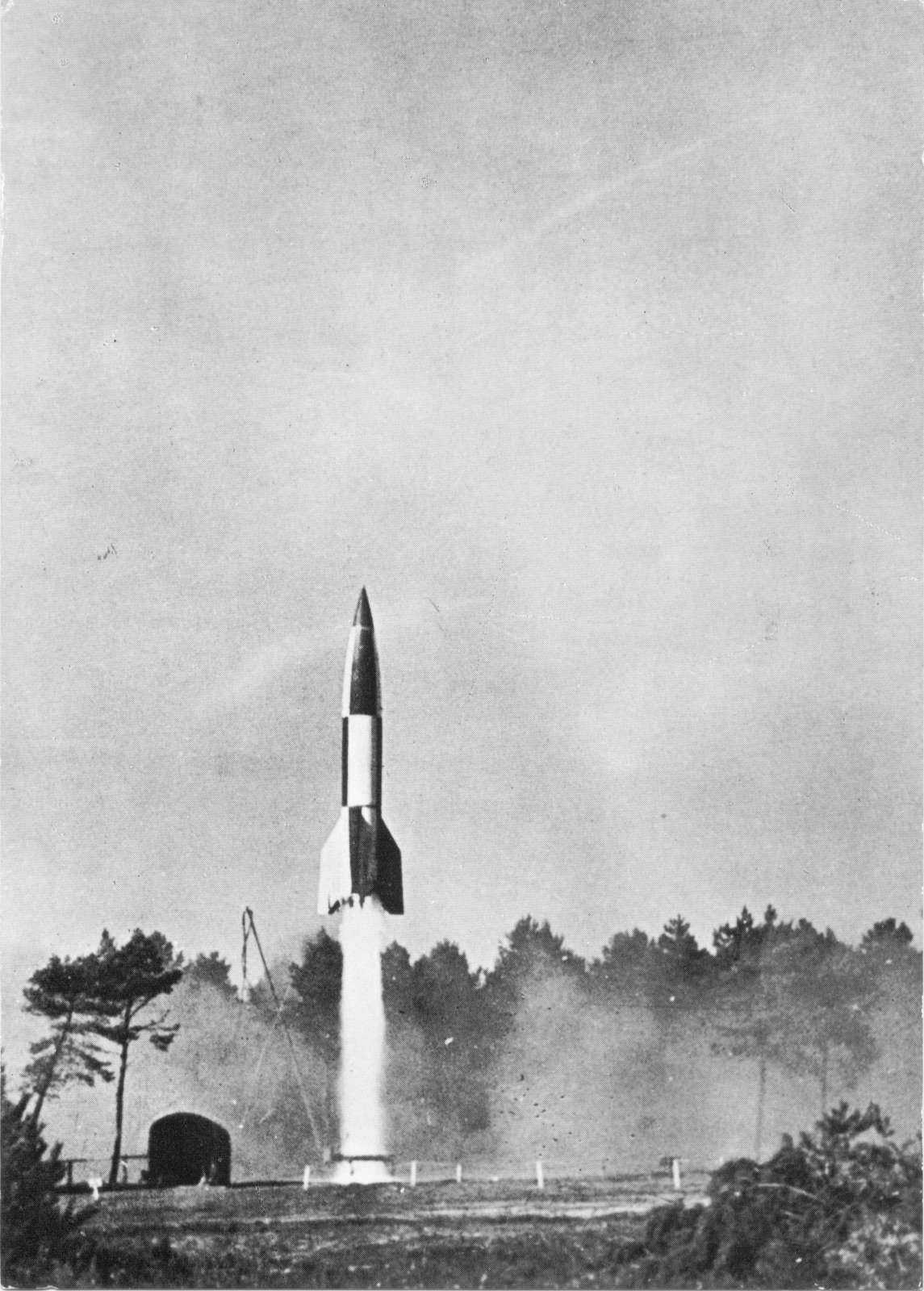

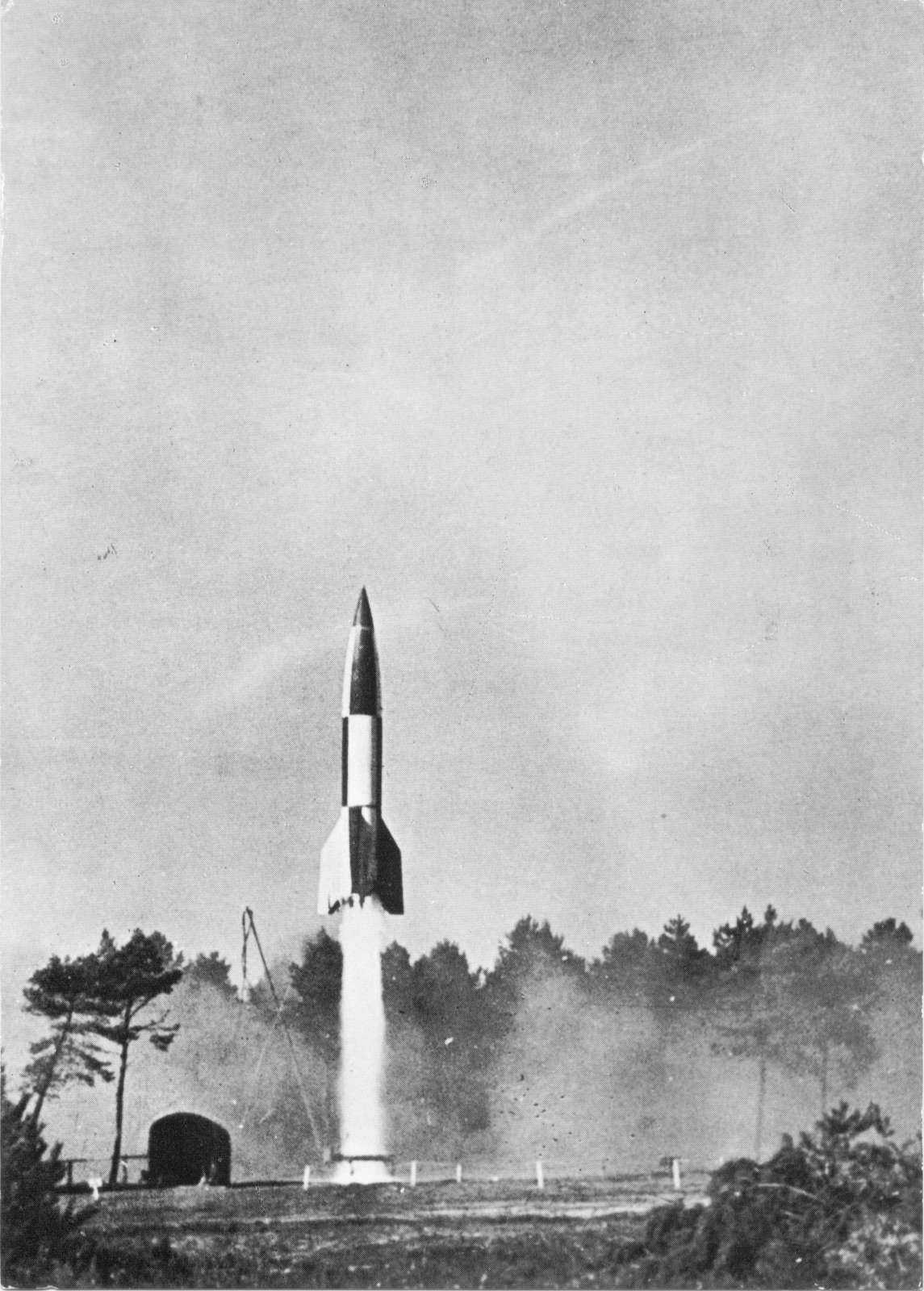

During WWII

During WWII Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

developed the world's first long range Liquid-propellant rocket

A liquid-propellant rocket or liquid rocket utilizes a rocket engine that uses liquid rocket propellant, liquid propellants. Liquids are desirable because they have a reasonably high density and high Specific impulse, specific impulse (''I''sp). T ...

s known as the V-2, with the technical name A4. The V-2 rocket was far more advanced than any rocket developed by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

and a race commenced, particularly United States and Soviets, to acquire the technology behind the V-2 and similar weapons developed by Nazi Germany.

The Soviet Union was first informed of the Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

's rocket programme in July 1944 by Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, who appealed directly to Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

to inspect a missile test station in Debica, Poland which was about to be overrun by advancing Soviet forces. British and Soviet personnel inspected the site and recovered A-4 missile parts, which were sent to London via Moscow. Whilst in Moscow the parts were inspected by several members of RNII.

In early 1945 a team of Soviet rocket specialists were sent to Germany to identify and recover German rocket technology. The first Soviet team to arrive at Nordhausen Nordhausen may refer to:

* Nordhausen (district), a district in Thuringia, Germany

** Nordhausen, Thuringia, a city in the district

**Nordhausen station, the railway station in the city

* Nordhouse, a commune in Alsace (German: Nordhausen)

* Narost ...

, the main V-2 construction site were disappointed, United States teams had already removed approximately 100 completed V-2 missiles and destroyed what remained. In addition, the majority of the German rocket engineers had surrendered to the United States, including a large quantity of documents relating to rocket technology. Soviet search teams did locate V-2 parts at Nordhausen Nordhausen may refer to:

* Nordhausen (district), a district in Thuringia, Germany

** Nordhausen, Thuringia, a city in the district

**Nordhausen station, the railway station in the city

* Nordhouse, a commune in Alsace (German: Nordhausen)

* Narost ...

, Lehesten

Lehesten is a town in the Thuringian Forest, 20 km southeast of Saalfeld.

World War II V-2 facility

After an August 194explosion at the Redl-Zipf V-2 liquid oxygen plant at Schlier stopped production, the third V-2 liquid oxygen plant (5000 ...

(test site for rocket engines) and other locations in the Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and larg ...

area. The Soviets also obtained some conceptual studies of the A-9/A-10 ocean range rockets and plans for the Rheinbote

''Rheinbote'' (''Rhine Messenger'', or V4) was a German short range ballistic rocket developed by Rheinmetall-Borsig at Berlin-Marienfelde during World War II. It was intended to replace, or at least supplement, large-bore artillery by providing f ...

short-range surface-surface missile. A Soviet missile research group based in Bleicherode

Bleicherode () is a town in the district of Nordhausen, in Thuringia, Germany. It is situated on the river Wipper, 17 km southwest of Nordhausen. On 1 December 2007, the former municipality Obergebra was incorporated by Bleicherode. The for ...

was created in July 1945 called Institute Rabe

Institut RABE (Missile Construction and Development in Bleicherode, Raketenbau und Entwicklung) was a group of German engineers founded by the Soviets to recreate the A-4 flight control system. It was created in July 1945 in Bleicherode when the R ...

, headed by Boris Chertok

Boris Yevseyevich Chertok (russian: link=no, Бори́с Евсе́евич Черто́к; – 14 December 2011) was a Russian electrical engineer and the control systems designer in the Soviet Union's space program, and later found employm ...

that recruited and employed German rocket specialists to work with Soviet engineers for restoring a working V-2 rocket flight control system. Institut RABE also retrieved German rocket specialists from the United States Occupation zone. As an early success in August 1945 Chertok recruited Helmut Gröttrup

Helmut Gröttrup (12 February 1916 – 4 July 1981) was a German engineer, rocket scientist and inventor of the smart card. During World War II, he worked in the German V-2 rocket program under Wernher von Braun. From 1946 to 1950 he headed a grou ...

(the deputy for the electrical system and missile control at Peenemünde

Peenemünde (, en, "Peene iverMouth") is a municipality on the Baltic Sea island of Usedom in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is part of the ''Amt'' (collective municipality) of Usedom-Nord. The communi ...

, also assistant to Ernst Steinhoff

Ernst August Wilhelm Steinhoff (February 11, 1908 – December 2, 1987) was a rocket scientist and member of the " von Braun rocket group", at the Peenemünde Army Research Center (1939–1945). Ernst Steinhoff saw National Socialist (Nazi) d ...

) from American territory, along with his family, and offered him founding the ''Büro Gröttrup'' in parallel to the Institut RABE. In February 1946 the Institute RABE was absorbed into the larger Institut Nordhausen, which had the goal of recreating the entire German A-4 rocket. It was directed by Korolew as the Chief Engineer and Gröttrup as the German head.

By October 1946, Institut Nordhausen employed 733 Soviet specialists, and between 5,000 and 7,000 Germans. In May 1946 the Soviet government decided that work in Germany would end in late 1946 with Soviet and German personnel transferred to Soviet locations. Therefore, the most capable German rocket scientists and engineers from the Bleicherode area were identified, and on 22 October, 152 personnel and their families (a total of 495 persons) were deported to the Soviet Union as part of Operation Osoaviakhim

Operation Osoaviakhim ()

was a secret Soviet operation under which more than 2,500 former Nazi German specialists

(; i.e. scientists, engineers and technicians who worked in specialist areas)

from companies and institutions relevant to military a ...

. According to another source, 2,552 German specialists together with 4,008 family members were relocated to the USSR, 302 of them having knowledge in rocketry, thereof 198 from the Zentralwerke.

The first Soviet tests of V-2 rockets took place in October 1947 at Kapustin Yar

Kapustin Yar (russian: Капустин Яр) is a Russian rocket launch complex in Astrakhan Oblast, about 100 km east of Volgograd. It was established by the Soviet Union on 13 May 1946. In the beginning, Kapustin Yar used technology, material ...

. Numerous German engineers participated in the tests. In June 1947 the German team, led by Gröttrup, proposed the development of an improved copy of the V-2, which he called the G-1 (called the R-10 in Soviet terms). This plan, whilst supported by senior Soviet management, was opposed by Soviet engineers, particularly by Sergei Korolev

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (russian: Сергей Павлович Королёв, Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov, sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ kərɐˈlʲɵf, Ru-Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.ogg; ukr, Сергій Павлович Корольов, ...

, who was now Chief Designer of long-range ballistic missiles to develop an improved Soviet copy of the V-2, that was designated the R-2. Due to political and security concerns, German specialists were not allowed knowledge or access to any Soviet missile design. Therefore, once the Soviets had mastered understanding and production of the V-2 rocket in 1946–47, all German specialists were excluded from Soviet developments. Their work was conducted independently, including work on the G-1, which proceeded as a "draft plan". In September 1948 test flights were carried on the R-1, the Soviet copy of the V-2 rocket, built with local materials. No German personnel were present for these tests at Kapustin Yar.

Glushko, who was Chief Designer of liquid-propellant rocket engines in OKB-456, utilised German expertise for mastering and improving the existing V-2 engine, internally called RD-100 (copy of V-2) and RD-101 (used for R-1) with a thrust of up to 267 kN. Further German ideas for increased thrust helped Glusko to develop RD-103 for the R-5 Pobeda

The R-5 Pobeda (Побе́да, "Victory") was a theatre ballistic missile developed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The R-5M version was assigned the NATO reporting name SS-3 Shyster and carried the GRAU index 8K51.

The R-5 was origi ...

with a thrust of 432 kN (500 tons) and higher efficiency. However once this was accomplished Glushko no longer needed their expertise and the German team was allowed to return from Khimki to Germany in September 1950.

In December 1948 the updated plan for the G-1 rocket was reviewed, which the German team had improved by range and accuracy. However major work on the G-1 was terminated by senior Soviet management. A number of other studies were carried out by the German specialist between 1948 and 1950, including the G-1M, G-2, G-3, G-4 and G-5. In October 1949 Korolev and Dmitry Ustinov

Dmitriy Fyodorovich Ustinov (russian: Дмитрий Фёдорович Устинов; 30 October 1908 – 20 December 1984) was a Marshal of the Soviet Union and Soviet politician during the Cold War. He served as a Central Committee sec ...

, the then Soviet Minister of Armaments, visited the branch of NII-88 in Gorodomlya to gather and understand German knowledge as much as possible to push the development of mid-range R-3 and R-5 Pobeda

The R-5 Pobeda (Побе́да, "Victory") was a theatre ballistic missile developed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The R-5M version was assigned the NATO reporting name SS-3 Shyster and carried the GRAU index 8K51.

The R-5 was origi ...

missiles. The concept of the G-4 targeted to build a long-range ballistic missile for a range of 3,000 km and a payload of 3 tons. The newly developed design scheme showed a number of changes compared to the V-2 and thus differed fundamentally from the rockets previously manufactured in the USSR. The newly chosen shape of a circular cone was intended to ensure increased aerodynamic stability so that the stabilization surfaces at the rear could be dispensed with. The position control was carried out by a swiveling engine. At the same time, the German designers paid attention to radical simplification of the overall system and consistent weight savings in order to achieve the required reliability and range.

The later studies from 1950 were limited to initial designs, including diagrams and calculations. By August 1950 the Soviet government had decided to send the Germans home, which occurred in three waves in December 1951, June 1952 and the last group of eight, including Gröttrup, left in November 1953.

The involvement of German scientists and engineers was an essential catalyst to early Soviet efforts. In 1945 and 1946 German expertise played a central role in reducing the time needed to master the intricacies of the V-2 rocket, establishing production of the R-1 rocket and enable a base for further developments. However, after 1947-48 the Soviets made very little use of German specialists as they were frozen out, worked on designs that were never used and their influence on the future Soviet rocket program was marginal. Details of Soviet achievements were unknown to the German team and completely underestimated by Western intelligence until, in November 1957, the Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

satellite was successfully launched to orbit by the Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

rocket based on R-7, the world's first intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

.

Advances in military systems

Over the course of the Cold War, the Soviet Union developed an estimated 500 LPRE rocket platforms. From 1958 to 1962, the Soviets researched and developed LPRE propelled anti-aircraft missile systems. These rockets primarily used nitric acid ratioed with a hypergolic amine for fuel. The need for mobile nuclear forces began to increase as the Cold War escalated in the early 1950s. The idea of naval launched tactical nuclear weaponry began to take hold. By 1950, the USSR had developed submarine launched ballistic missiles. These missiles were multi stage, but due to fuel constraints, they could not be launched from underwater. The initial missile system used land based armaments. The USSR is the only known nation to utilize LPRE fueled engines for its SLBMs. In 1982, the Soviets began testing of theRD-170

The RD-170 ( rus, РД-170, Ракетный Двигатель-170, Raketnyy Dvigatel-170) is the world's most powerful and heaviest liquid-fuel rocket engine. It was designed and produced in the Soviet Union by NPO Energomash for use with the ...

. This nitric acid and kerosene propelled rocket was capable of producing more thrust than any engine available. The RD-170 had 4 variable thrusters with staged combustion

Staged combustion is a method used to reduce the emission of nitrogen oxides ( NOx) during combustion. There are two methods for staged combustion: air staged supply and fuel staged supply. Applications of staged combustion include boilers and ro ...

. The engine experienced early technical difficulties, and it experienced massive damage as it was shut down in stages. To remediate this, Soviet engineers had to reduce its thrust capacity. The engine was officially flight tested successfully in 1985.

Space age advances

Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

was the first artificial Earth satellite ever launched. On October 4, 1957, the USSR launched Sputnik 1 into orbit and received transmissions from it. Sputnik 1 was designed to be the forerunner for multiple satellite missions. The technology constantly underwent upgrades as the weight of satellites increased. The first notable failure occurred during Sputnik 4

Korabl-Sputnik 1 (russian: Корабль Спутник 1 meaning ''Vessel Satellite 1''), also known as Sputnik 4 in the West, was the first test flight of the Soviet Vostok programme, and the first Vostok spacecraft. It was launched on May 15, 1 ...

, an unmanned test of the Vostok capsule. A guidance system malfunction pointed the capsule in the wrong direction for the orbit-exiting engine burn, sending it instead into a higher orbit, which decayed approximately four months later. The success of Sputnik 1 was followed by the launch of 175 meteorological rockets in the next two years. In all, there were ten of the Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

satellites launched.

The Soviet Space Program brought about numerous advances such as Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

. However, before the institution of the satellite probe, technology needed to be developed in order to ensure the success of the satellite. In order for the probe to be successful in space, a mechanism needed to be developed to get the object outside Earth's atmosphere. The propulsion system that was utilized to send Sputnik 1 into space was dubbed the R-7. The design of the R-7 was also unique for its time and allowed for the Sputnik 1 launch to be a success. One key aspect was the type of fuel utilized to propel the rocket. A main component of the fuel was UDMH

Unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH; 1,1-dimethylhydrazine, НДМГ or codenamed Geptil) is a chemical compound with the formula H2NN(CH3)2 that is used as a rocket propellant. It is a colorless liquid, with a sharp, fishy, ammonia-like smell ...

which when combined with other compounds yielded a fuel that was both potent and stable at certain temperatures.

The ability to launch satellites came from the Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

(ICBM) arsenal, using the RD-107

The RD-107 and its sibling, the RD-108, are a type of rocket engine initially used to launch R-7 Semyorka missiles. RD-107 engines were later used on space launch vehicles based on the R-7. , very similar RD-107A and RD-108A engines are used to la ...

engine for the Vostok launch vehicle. The first Vostok version had 1 core engine and 4 strap-on stage engines. The engines were all vectored thrust capable. The original Vostok was fueled by liquid oxygen and kerosene. There were a total of 20 engines, each capable of contributing of thrust. The Vostok engine was the first true Soviet design. The technical name was the RD-107 and later the RD-108. These engines had two thrust chambers. They were originally mono-propellant-burning using hydrogen peroxide fuel. This family of engines were utilized not just on the Vostok, but also on the Voskhod, Molniya Molniya (Russian for ''lightning'') may refer to:

* Molniya (satellite), a Soviet military communications satellite

** Molniya orbit

* Molniya (explosive trap), a KGB explosive device

* Molniya (rocket), a variation of the Soyuz launch vehicle

* OKB ...

, and Soyuz Soyuz is a transliteration of the Cyrillic text Союз (Russian and Ukrainian, 'Union'). It can refer to any union, such as a trade union (''profsoyuz'') or the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (Сою́з Сове́тских Социалис� ...

launch vehicles.

By 1959, the space program needed a 3-stage engine platform, so the Vostok engine was adapted accordingly for launching Moon probes. By 1963, the Vostok was equipped for 4-stage applications. This platform was used for the first multi-manned flight. As 1964 began, the Soviets introduced a new engine into its booster engine program, the RD-0110

The RD-0110 (or RO-8 , RD-0108 , RD-461 ) is a rocket engine burning liquid oxygen and kerosene in a gas generator combustion cycle. It has four fixed nozzles and the output of the gas generator is directed to four secondary vernier nozzles to s ...

. This engine replaced the RD-107 in the second stage, in both the Molniya and Soyuz launch vehicles. These engines were liquid oxygen propelled, with kerosene coolant. The RD-0110 had four variable thrusters. This engine was unique because it initially was launched by a solid fuel propellant, but was fueled in flight by liquid oxygen.

This development caused a new problem for the Soviet scientific community, however. The Vostok was too powerful for newer satellites trying to reach low Earth orbit

A low Earth orbit (LEO) is an orbit around Earth with a period of 128 minutes or less (making at least 11.25 orbits per day) and an eccentricity less than 0.25. Most of the artificial objects in outer space are in LEO, with an altitude never mor ...

. The space community turned once again to the Soviet missile command. The new Intermediate Ballistic Missiles (IBRM) systems provided two engine options: the Sandal

Sandals are an open type of footwear, consisting of a sole held to the wearer's foot by straps going over the instep and around the ankle. Sandals can also have a heel. While the distinction between sandals and other types of footwear can some ...

(1 stage), or the Skean (2 stage). Both systems were upgraded to a new RD-111 engine. Following these upgrades, the largest satellite called Proton I was launched in 1965. Stoiko, p. 97 The type of engine used for Proton I was the RD-119. This engine provided nearly of thrust, and was ultimately used to execute low Earth orbit.

December 8, 1957 the Soviet Union head of the Academy of Science addressed the United States in regard to the first artificial satellite that was sent off on October 4, 1957. It was his belief that part of this satellite had fallen back into the North American Continent. The Soviets were wanting the help of the Americans in order to recover the satellite components, however the United States was planning on viewing the satellite technology in order to develop their own satellites and rockets for propulsion and re-entry.

From the year 1961-1963 the Soviet Union wanted to improve on their designs. This led to the development of a new rocket for propulsion. This new rocket was dubbed the N1. This rocket was to become a sophisticated improvement on traditional Soviet design and would pave the way for numerous rocket launches. The specifications to the rocket were also astounding for its time. The amount of thrust generated by the rocket ranged from 10 to 20 tons of thrust which was capable of launching a 40-50 ton satellite into orbit. The man that played a crucial role in the development of this new rocket was Sergei Korolev

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (russian: Сергей Павлович Королёв, Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov, sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ kərɐˈlʲɵf, Ru-Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.ogg; ukr, Сергій Павлович Корольов, ...

. The development of the N1 rocket became the successor to other Soviet designed rockets such as the R-7. It also brought about ample competition to the United States' counterpart moon rocket; the Saturn V

Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, with multistage rocket, three stages, and powered with liquid-propellant r ...

. However, one key difference between the two rockets was the stages that occurred in a typical launch. Whereas the Saturn V had four-stages, the N1 had five stages. The fifth stage of the N1 was utilized for the landing position. The N1 was powered by engines such as the NK-33

The NK-33 and NK-43 are rocket engines designed and built in the late 1960s and early 1970s by the Kuznetsov Design Bureau. The NK designation is derived from the initials of chief designer Nikolay Kuznetsov. The NK-33 was among the most powerfu ...

, NK-43, and NK-39. As revolutionary as this design style had become, the construction was not run as smoothly as expected. The clashing of ideas between scientists wanting to go public with their work and military entities wanting to keep the project as secretive as possible caused delays and hindered the project from progressing at times. As time progressed the N1 was prone to several design flaws. These flaws caused numerous failed launches because of the first stage in its design being faulty. The late 1960s yielded many failed launch attempts. Eventually the program was shut down.

See also

*Soviet space program

The Soviet space program (russian: Космическая программа СССР, Kosmicheskaya programma SSSR) was the national space program of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), active from 1955 until the dissoluti ...

* Sergei Korolev

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (russian: Сергей Павлович Королёв, Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov, sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ kərɐˈlʲɵf, Ru-Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.ogg; ukr, Сергій Павлович Корольов, ...

(1907-1966), chief engineer and brain of the Soviet rocketry and space program, head of Experimental Design Bureau OKB

OKB is a transliteration of the Russian initials of "" – , meaning 'experiment and design bureau'. During the Soviet era, OKBs were closed institutions working on design and prototyping of advanced technology, usually for military applications. ...

-1

* Valentin Glushko

Valentin Petrovich Glushko (russian: Валенти́н Петро́вич Глушко́; uk, Валентин Петрович Глушко, Valentyn Petrovych Hlushko; born 2 September 1908 – 10 January 1989) was a Soviet engineer and the m ...

(1908-1989), chief designer of rocket engines, head of OKB-456

*Dmitry Ustinov

Dmitriy Fyodorovich Ustinov (russian: Дмитрий Фёдорович Устинов; 30 October 1908 – 20 December 1984) was a Marshal of the Soviet Union and Soviet politician during the Cold War. He served as a Central Committee sec ...

(1908-1984), military head of Soviet rocketry and space program, People's Commissar of Armaments from 1941, Defence Minister from 1976

*Boris Chertok

Boris Yevseyevich Chertok (russian: link=no, Бори́с Евсе́евич Черто́к; – 14 December 2011) was a Russian electrical engineer and the control systems designer in the Soviet Union's space program, and later found employm ...

(1912-2011), control systems designer

References

Cited sources

* * * * * * *Bibliography

* Burgess, Colin, and Hall, Rex. ''The First Soviet Cosmonaut Team: Their Lives, Legacy, and Historical Impact''. Berlin: Springer, 2009. * * Chertok, B. E''Rockets and People: Volume II''

Washington, D.C.: NASA, 2006. Accessed April 7, 2016. * Chertok, Boris Evseyevich. ''Rockets and People: Volume IV: The Moon Race''. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NASA History Office, Office of External Affairs, 2005. * Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition. ''Wernher Von Braun''. June 2015. Accessed April 8, 2016. * Darrin, Ann Garrison and O'Leary, Beth Laura. ''Handbook of Space Engineering, Archaeology, and Heritage''. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, 2009. * Faure, Gunter, and Mensing, Teresa M. ''Introduction to Planetary Science: The Geological Perspective.'' Dordrecht: Springer, 2007.

''Encyclopedia Astronautica Glushko.'' Web, Accessed 08 Apr. 2016. * Hagler, Gina. ''Modeling Ships and Space Craft: The Science and Art of Mastering the Oceans and Sky''. New York: Springer, 2013. * Harvey, Brian. ''Russian Planetary Exploration: History, Development, Legacy, Prospects''. Berlin: Springer, 2007.

Florida International University. Accessed 08 Apr. 2016. * "Konstantin Tsiolkovsky." NASA. Accessed 08 Apr. 2016.

* Lethbridge, Cliff. "History of Rocketry Chapter 6: 1945 to the Creation of NASA." ''Spaceline''. (2000). Accessed April 7, 2016. http://www.spaceline.org/history/6.html. * MSFC History Office: NASA

Accessed April 7, 2016. * {{cite journal , last1 = O'Brien , first1 = Jason L. , last2 = Sears , first2 = Christine E. , title = Victor or Villain? Wernher von Braun and the Space Race , journal = Social Studies , volume = 102 , issue = 2

''Russian Space Web.'' Web, Accessed 08 Apr. 2016.

"Yury Alekseyevich Gagarin."

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Rocket propulsion Space program of the Soviet Union Science and technology in the Soviet Union