Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

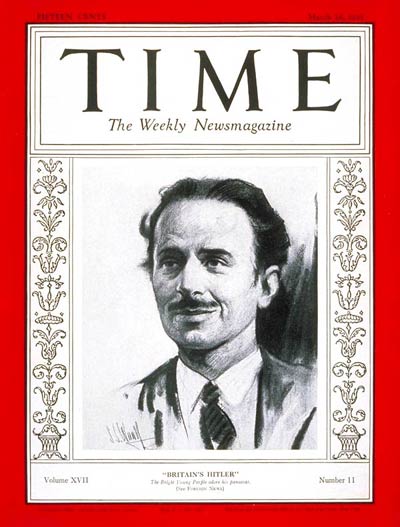

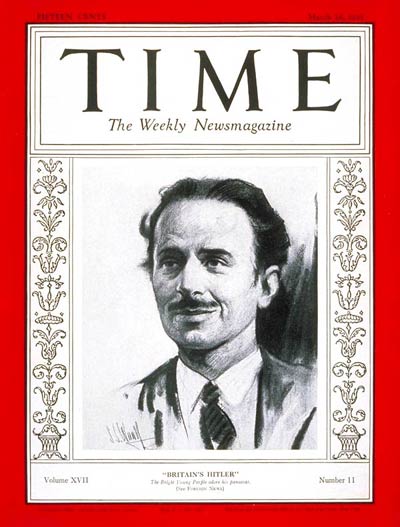

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to

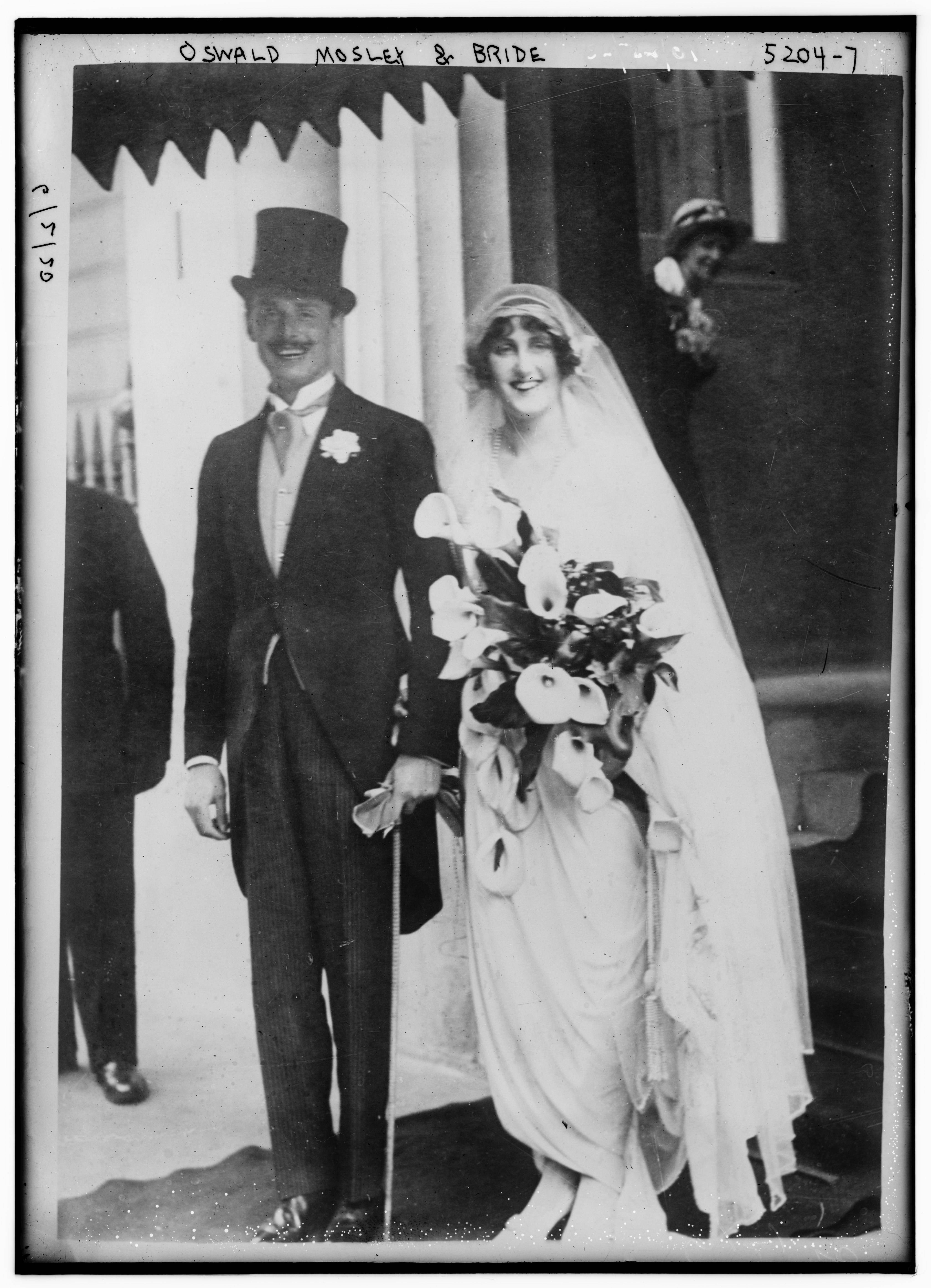

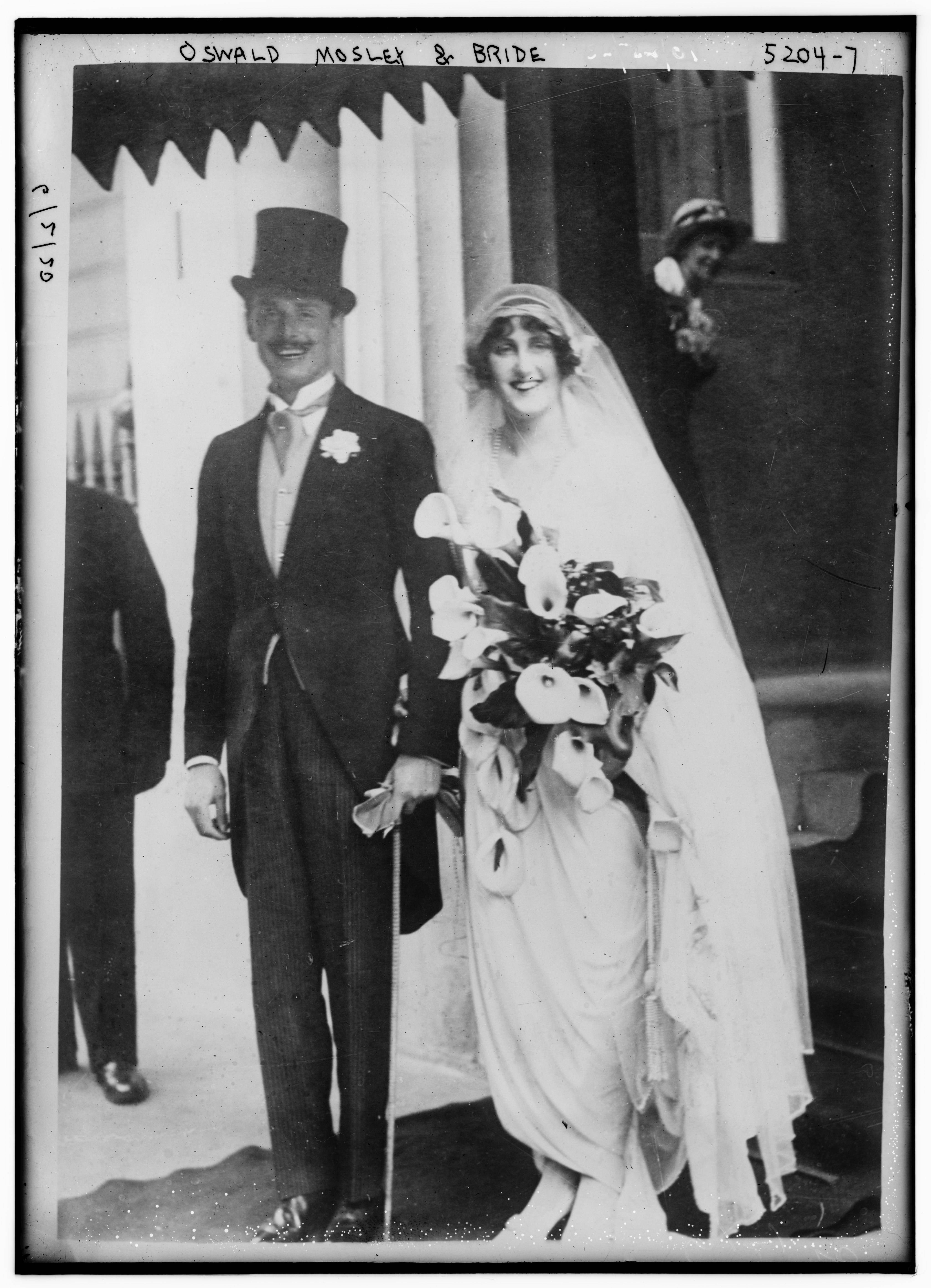

On 11 May 1920, he married Lady Cynthia "Cimmie" Curzon (1898–1933), second daughter of the 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston (1859–1925), Viceroy of India 1899–1905,

On 11 May 1920, he married Lady Cynthia "Cimmie" Curzon (1898–1933), second daughter of the 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston (1859–1925), Viceroy of India 1899–1905,

Dissatisfied with the Labour Party, Mosley founded the New Party.

Its early parliamentary contests, in the

Dissatisfied with the Labour Party, Mosley founded the New Party.

Its early parliamentary contests, in the

After his election failure in 1931, Mosley went on a study tour of the "new movements" of Italy's

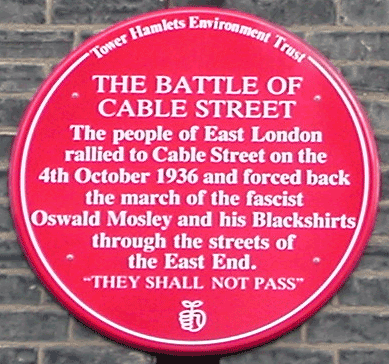

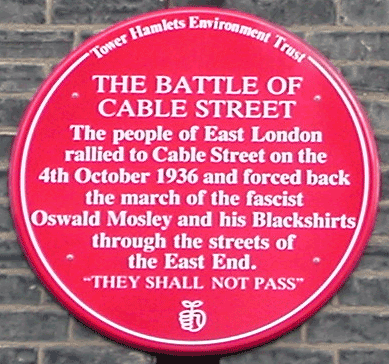

After his election failure in 1931, Mosley went on a study tour of the "new movements" of Italy's  In October 1936, Mosley and the BUF attempted to march through an area with a high proportion of Jewish residents. Violence, since called the Battle of Cable Street, resulted between protesters trying to block the march and police trying to force it through. At length Sir

In October 1936, Mosley and the BUF attempted to march through an area with a high proportion of Jewish residents. Violence, since called the Battle of Cable Street, resulted between protesters trying to block the march and police trying to force it through. At length Sir

''Not The Nine O'Clock News'': "Baronet Oswald Ernald Mosley"

''Some of the Corpses are Amusing''. *The

Friends of Oswald Mosley

at oswaldmosley.com, containing archives of his speeches and books * * * * * (last accessible, 23 October 2017) * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mosley, Oswald 1896 births 1980 deaths 16th The Queen's Lancers officers Anti-Masonry Antisemitism in the United Kingdom Baronets in the Baronetage of Great Britain British Army personnel of World War I British Holocaust deniers British political party founders British Union of Fascists politicians British white supremacists Chancellors of the Duchy of Lancaster Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Deaths from Parkinson's disease English expatriates in France English far-right politicians English memoirists Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Independent Labour Party National Administrative Committee members Independent members of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Labour Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Mosley baronets Oswald Neurological disease deaths in France Pan-European nationalism People detained under Defence Regulation 18B People educated at West Downs School People educated at Winchester College People from Burton upon Trent Racism in the United Kingdom Royal Flying Corps officers Sexism in the United Kingdom UK MPs 1918–1922 UK MPs 1922–1923 UK MPs 1923–1924 UK MPs 1924–1929 UK MPs 1929–1931 Union Movement politicians People_with_Parkinson's_disease

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. He was a member of parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

and later founded and led the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, fo ...

(BUF).

After military service during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Mosley was one of the youngest members of parliament, representing Harrow from 1918

This year is noted for the end of the First World War, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, as well as for the Spanish flu pandemic that killed 50–100 million people worldwide.

Events

Below, the events ...

to 1924

Events

January

* January 12 – Gopinath Saha shoots Ernest Day, whom he has mistaken for Sir Charles Tegart, the police commissioner of Calcutta, and is arrested soon after.

* January 20– 30 – Kuomintang in China hol ...

, first as a Conservative, then an independent, before joining the Labour Party. At the 1924 general election he stood in Birmingham Ladywood against the future prime minister, Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasemen ...

, coming within 100 votes of defeating him.

Mosley returned to Parliament as Labour MP for Smethwick

Smethwick () is an industrial town in Sandwell, West Midlands, England. It lies west of Birmingham city centre. Historically it was in Staffordshire.

In 2019, the ward of Smethwick had an estimated population of 15,246, while the wider bu ...

at a by-election in 1926 and served as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster in the Labour Government of 1929–31

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

. In 1928, he succeeded his father as the sixth Mosley baronet, a title that had been in his family for more than a century. He was considered a potential Labour Prime Minister but resigned because of discord with the government's unemployment policies. He chose not to defend his Smethwick constituency at the 1931 general election, instead unsuccessfully standing in Stoke-on-Trent

Stoke-on-Trent (often abbreviated to Stoke) is a city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Staffordshire, England, with an area of . In 2019, the city had an estimated population of 256,375. It is the largest settlement ...

. Mosley's New Party became the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, fo ...

(BUF) in 1932.

Mosley was imprisoned in May 1940 and the BUF was banned. He was released in 1943 and, politically disgraced by his association with fascism, moved abroad in 1951, spending most of the remainder of his life in Paris and two residences in Ireland. He stood for Parliament during the post-war era but received very little support. During this latter period he was an advocate of pro-European

Pro-Europeanism, sometimes called European Unionism, is a political position that favours European integration and membership of the European Union (EU).Krisztina Arató, Petr Kaniok (editors). ''Euroscepticism and European Integration''. Polit ...

integration. He is also known for the influence he had on the thinking of the founders of the Soil Association, a catalyst for the organic farming movement in Great Britain.

Life and career

Early life and education

Mosley was born on 16 November 1896 at 47 Hill Street,Mayfair

Mayfair is an affluent area in the West End of London towards the eastern edge of Hyde Park, in the City of Westminster, between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane. It is one of the most expensive districts in the world. ...

, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

. He was the eldest of the three sons of Sir Oswald Mosley, 5th Baronet

Sir Oswald Mosley, 5th Baronet (29 December 1873 – 21 September 1928), was a British Army officer, aristocrat, amateur sportsman, and the father of Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists (BUF). His interests were in shootin ...

(1873–1928), and Katharine Maud Edwards-Heathcote (1874–1950), daughter of Captain Justinian H. Edwards-Heathcote of Apedale Hall, Staffordshire. He had two younger brothers: Edward Heathcote Mosley (1899–1980) and John Arthur Noel Mosley (1901–1973).

The family traces its roots to Ernald de Mosley of Bushbury, Staffordshire, in the time of King John King John may refer to:

Rulers

* John, King of England (1166–1216)

* John I of Jerusalem (c. 1170–1237)

* John Balliol, King of Scotland (c. 1249–1314)

* John I of France (15–20 November 1316)

* John II of France (1319–1364)

* John I o ...

in the 12th century. The family was prominent in Staffordshire and three baronetcies were created, two of which are now extinct. His five-time great-grandfather John Parker Mosley, a Manchester hatter, was made a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

in 1781. His father was a third cousin to the 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, father of the future Queen Mother

A queen mother is a former queen, often a queen dowager, who is the mother of the reigning monarch. The term has been used in English since the early 1560s. It arises in hereditary monarchies in Europe and is also used to describe a number of ...

.

After Mosley's parents separated, he was raised by his mother, who went to live at Betton Hall near Market Drayton

Market Drayton is a market town and electoral ward in the north of Shropshire, England, close to the Cheshire and Staffordshire borders. It is on the River Tern, and was formerly known as "Drayton in Hales" (c. 1868) and earlier simply as "Dray ...

, and his paternal grandfather, Sir Oswald Mosley, 4th Baronet

Sir Oswald Mosley, 4th Baronet (25 September 1848 – 10 October 1915),'MOSLEY, Sir Oswald', Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007 was a British baronet and landowner.

Family

Mosley was born in Sta ...

. Within the family and among intimate friends, he was always called "Tom". He lived for many years at his grandparents' stately home, Apedale Hall, and was educated at West Downs School and Winchester College.

Mosley was a fencing champion in his school days; he won titles in both foil and sabre, and retained an enthusiasm for the sport throughout his life.

Military service

In January 1914, Mosley entered the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, but was expelled in June for a "riotous act of retaliation" against a fellow student. During theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

he was commissioned into the British cavalry unit the 16th The Queen's Lancers

The 16th The Queen's Lancers was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, first raised in 1759. It saw service for two centuries, before being amalgamated with the 5th Royal Irish Lancers to form the 16th/5th Lancers in 1922.

History

Early war ...

and fought in France on the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

. He transferred to the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

as an observer, but while demonstrating in front of his mother and sister he crashed, which left him with a permanent limp, as well as a reputation for being brave and somewhat reckless. He returned to the trenches before the injury had fully healed and at the Battle of Loos (1915) passed out at his post from pain. He spent the remainder of the war at desk jobs in the Ministry of Munitions and in the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

.

Marriage to Lady Cynthia Curzon

On 11 May 1920, he married Lady Cynthia "Cimmie" Curzon (1898–1933), second daughter of the 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston (1859–1925), Viceroy of India 1899–1905,

On 11 May 1920, he married Lady Cynthia "Cimmie" Curzon (1898–1933), second daughter of the 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston (1859–1925), Viceroy of India 1899–1905, Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

1919–1924, and Lord Curzon's first wife, the U.S. mercantile heiress Mary Leiter

Mary Victoria Curzon, Baroness Curzon of Kedleston, (née Leiter; May 27, 1870July 18, 1906) was a British peeress of American background who was Vicereine of India, as the wife of Lord Curzon of Kedleston, Viceroy of India. As Vicereine of ...

.

Lord Curzon had to be persuaded that Mosley was a suitable husband, as he suspected Mosley was largely motivated by social advancement in Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

politics and Cynthia's inheritance. The 1920 wedding took place in the Chapel Royal in St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Altho ...

in London. The hundreds of guests included King George V and Queen Mary, as well as foreign royalty such as the Duke and Duchess of Brabant (later King Leopold III and Queen Astrid

Queen or QUEEN may refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a Kingdom

** List of queens regnant

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Queen mother, a queen dowager who is the mothe ...

of Belgium).

During this marriage, he began an extended affair with his wife's younger sister, Lady Alexandra Metcalfe, and a separate affair with their stepmother, Grace Curzon, Marchioness Curzon of Kedleston

Grace Elvina Curzon, Marchioness Curzon of Kedleston, GBE (née Hinds, formerly Duggan; May 16, 1885 – June 29, 1958) was an American-born British marchioness and the second wife of George Curzon, British parliamentarian, cabinet minister, and ...

, the American-born second wife and widow of Lord Curzon of Kedleston. He succeeded to the Baronetcy of Ancoats upon his father's death in 1928.

India and Gandhi

Among his many travels, Mosley travelled to British India accompanied by Lady Cynthia in 1924. His father-in-law's past as Viceroy of India allowed for the acquaintance of various personalities along the journey. They travelled by ship and stopped briefly in Cairo. Having initially arrived inCeylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

(present day Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

), the journey then continued through mainland India. They spent these initial days in the government house of Ceylon, followed by Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

and then Calcutta, where the Governor at the time was Lord Lytton

Earl of Lytton, in the County of Derby, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1880 for the diplomat and poet Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Baron Lytton. He was Viceroy of India from 1876 to 1880 and British Ambassad ...

.

Mosley met Mahatma Gandhi through C.F. Andrews

Charles Freer Andrews (12 February 1871 – 5 April 1940) was an Anglican priest and Christian missionary, educator and social reformer, and an activist for Indian independence. He became a close friend of Rabindranath Tagore and Mahatma Gan ...

, a clergyman and an intimate friend of the "Indian Saint", as Mosley described him. They met in Kadda, where Gandhi was quick to invite him to a private conference in which Gandhi was chairman. They enjoyed each other's company for the short time they were together. Mosley later called Gandhi a "sympathetic personality of subtle intelligence".

Marriage to Diana Mitford

Cynthia died of peritonitis in 1933, after which Mosley married his mistressDiana Guinness

Diana, Lady Mosley (''née'' Freeman-Mitford; 17 June 191011 August 2003) was one of the Mitford sisters. In 1929 she married Bryan Walter Guinness, heir to the barony of Moyne, with whom she was part of the Bright Young Things social group o ...

, ''née'' Mitford (1910–2003). They married in secret in Nazi Germany on 6 October 1936 in the Berlin home of Germany's Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

. Adolf Hitler was their guest of honour.

Mosley spent large amounts of his private fortune on the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, fo ...

(BUF) and tried to establish it on a firm financial footing by various means including an attempt to negotiate, through Diana, with Hitler for permission to broadcast commercial radio to Britain from Germany. Mosley reportedly made a deal in 1937 with Francis Beaumont

Francis Beaumont ( ; 1584 – 6 March 1616) was a dramatist in the English Renaissance theatre, most famous for his collaborations with John Fletcher.

Beaumont's life

Beaumont was the son of Sir Francis Beaumont of Grace Dieu, near Thrin ...

, heir to the Seigneurage of Sark, to set up a privately owned radio station on Sark.

Member of Parliament

By the end of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Mosley had decided to go into politics as a Conservative Member of Parliament, as he had no university education or practical experience because of the war. He was 21 years old. He was driven by, and in Parliament spoke of, a passionate conviction to avoid any future war, and this seemingly motivated his career. Largely because of his family background and war service, local Conservative and Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

associations preferred Mosley in several constituencies – a vacancy near the family estates seemed to be the best prospect. He was unexpectedly selected for Harrow first. In the general election of 1918 he faced no serious opposition and was elected easily. He was the youngest member of the House of Commons to take his seat, though Joseph Sweeney, an abstentionist Sinn Féin member, was younger. He soon distinguished himself as an orator and political player, one marked by extreme self-confidence, and made a point of speaking in the House of Commons without notes. Mosley was an early supporter of the economist John Maynard Keynes. The economic historian Robert Skidelsky described Mosley as "a disciple of Keynes in the 1920s".

Crossing the floor

Mosley was at this time falling out with the Conservatives over its Irish policy, and condemned the operations of the Black and Tans against civilians during theIrish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. He was secretary of the Peace with Ireland Council. As secretary of the council, he proposed sending a commission to Ireland to examine on-the-spot reprisals by the Black and Tans.

In late 1920, he crossed the floor

Crossed may refer to:

* ''Crossed'' (comics), a 2008 comic book series by Garth Ennis

* ''Crossed'' (novel), a 2010 young adult novel by Ally Condie

* "Crossed" (''The Walking Dead''), an episode of the television series ''The Walking Dead''

S ...

to sit as an independent MP on the opposition side of the House of Commons. Having built up a following in his constituency, he retained it against a Conservative challenge in the 1922

Events

January

* January 7 – Dáil Éireann (Irish Republic), Dáil Éireann, the parliament of the Irish Republic, ratifies the Anglo-Irish Treaty by 64–57 votes.

* January 10 – Arthur Griffith is elected President of Dáil Éirean ...

and 1923 general elections.

The Liberal '' Westminster Gazette'' wrote that Mosley was:

By 1924, he was growing increasingly attracted to the Labour Party, which had just formed a government, and in March he joined it. He immediately joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) as well and allied himself with the left.

When the government fell in October, Mosley had to choose a new seat, as he believed that Harrow would not re-elect him as a Labour candidate. He therefore decided to oppose Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasemen ...

in Birmingham Ladywood. Mosley campaigned aggressively in Ladywood, and accused Chamberlain of being a "landlords' hireling". The outraged Chamberlain demanded that Mosley retract the claim "as a gentleman". Mosley, whom Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

described as "a cad and a wrong 'un", refused to retract the allegation. Mosley was noted for bringing excitement and energy to the campaign. Leslie Hore-Belisha, a senior Conservative, recorded his impressions of Mosley as a platform orator at this time, claiming that his "dark, aquiline, flashing: tall, thin, assured; defiance in his eye, contempt in his forward chin". Together, Oswald and Cynthia Mosley proved an alluring couple, and many members of the working class in Birmingham succumbed to their charm for, as the historian Martin Pugh described, "a link with powerful, wealthy and glamorous men and women appealed strongly to those who endured humdrum and deprived lives". It took several re-counts before Chamberlain was declared the winner by 77 votes and Mosley blamed poor weather for the result. His period outside Parliament was used to develop a new economic policy for the ILP, which eventually became known as the Birmingham Proposals; they continued to form the basis of Mosley's economics until the end of his political career.

Mosley was critical of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

’s policy as Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

. After Churchill returned Britain to the Gold Standard, Mosley claimed that "faced with the alternative of saying goodbye to the gold standard, and therefore to his own employment, and goodbye to other people's employment, Mr. Churchill characteristically selected the latter course".

In 1926, the Labour-held seat of Smethwick

Smethwick () is an industrial town in Sandwell, West Midlands, England. It lies west of Birmingham city centre. Historically it was in Staffordshire.

In 2019, the ward of Smethwick had an estimated population of 15,246, while the wider bu ...

fell vacant, and Mosley returned to Parliament after winning the resulting by-election on 21 December. Mosley felt the campaign was dominated by Conservative attacks on him for being too rich, including claims that he was covering up his wealth.

In 1927, he mocked the British Fascists as "black-shirted buffoons, making a cheap imitation of ice-cream sellers". The ILP elected him to Labour's National Executive Committee.

Mosley and Cynthia were committed Fabians

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. The Fab ...

in the 1920s and at the start of the 1930s. Mosley appears in a list of names of Fabians from ''Fabian News'' and the ''Fabian Society Annual Report 1929–31''. He was Kingsway Hall lecturer in 1924 and Livingstone Hall lecturer in 1931.

Office

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

Mosley then made a bold bid for political advancement within the Labour Party. He was close toRamsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

and hoped for one of the Great Offices of State, but when Labour won the 1929 general election he was appointed only to the post of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, a position without Portfolio and outside the Cabinet. He was given responsibility for solving the unemployment problem, but found that his radical proposals were blocked either by Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and abov ...

James Henry Thomas

James Henry Thomas (3 October 1874 – 21 January 1949), sometimes known as Jimmy Thomas or Jim Thomas, was a Welsh trade unionist and Labour (later National Labour) politician. He was involved in a political scandal involving budget leaks.

...

or by the Cabinet.

Mosley Memorandum

Realising the economic uncertainty that was facing the nation because of the death of its domestic industry, Mosley put forward a scheme in the "Mosley Memorandum" that called for high tariffs to protect British industries from international finance and transform the British Empire into anautarkic

Autarky is the characteristic of self-sufficiency, usually applied to societies, communities, states, and their economic systems.

Autarky as an ideal or method has been embraced by a wide range of political ideologies and movements, especiall ...

trading bloc, for state nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

of main industries, for higher school-leaving ages and pensions

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

to reduce the labour surplus, and for a programme of public works to solve interwar poverty and unemployment. Furthermore, the memorandum laid out the foundations of the corporate state which intended to combine businesses, workers and the government into one body as a way to "Obliterate class conflict and make the British economy healthy again".

Mosley published this memorandum because of his dissatisfaction with the laissez-faire attitudes held by both Labour and the Conservative party, and their passivity towards the ever-increasing globalisation of the world, and thus looked to a modern solution to fix a modern problem. But it was rejected by the Cabinet and by the Parliamentary Labour Party, and in May 1930 Mosley resigned from his ministerial position. At the time, the weekly Liberal-leaning paper '' The Nation and Athenaeum'' described his move: "The resignation of Sir Oswald Mosley is an event of capital importance in domestic politics... We feel that Sir Oswald has acted rightly – as he has certainly acted courageously – in declining to share any longer in the responsibility for inertia." In October he attempted to persuade the Labour Party Conference to accept the Memorandum, but was defeated again.

The Mosley Memorandum won the support of the economist John Maynard Keynes, who stated that "it was a very able document and illuminating". Keynes also wrote, "I like the spirit which informs the document. A scheme of national economic planning to achieve a right, or at least a better, balance of our industries between the old and the new, between agriculture and manufacture, between home development and foreign investment; and wide executive powers to carry out the details of such a scheme. That is what it amounts to. ... hemanifesto offers us a starting point for thought and action. ... It will shock—it must do so—the many good citizens of this country...who have laissez-faire in their craniums, their consciences, and their bones ... But how anyone professing and calling himself a socialist can keep away from the manifesto is a more obscure matter."

Thirty years later, in 1961, Richard Crossman

Richard Howard Stafford Crossman (15 December 1907 – 5 April 1974) was a British Labour Party politician. A university classics lecturer by profession, he was elected a Member of Parliament in 1945 and became a significant figure among the ...

wrote, "this brilliant memorandum was a whole generation ahead of Labour thinking." As his book, ''The Greater Britain'', focused on the issues of free trade, the criticisms against globalisation that he formulated can be found in critiques of contemporary globalisation. He warns nations that buying cheaper goods from other nations may seem appealing but ultimately ravage domestic industry and lead to large unemployment, as seen in the 1930s. He argues that trying to "challenge the 50-year-old system of free trade ... exposes industry in the home market to the chaos of world conditions, such as price fluctuation, dumping, and the competition of sweated labour, which result in the lowering of wages and industrial decay."

In a newspaper feature, Mosley was described as "a strange blend of J.M. Keynes and Major Douglas

Major Clifford Hugh "C. H." Douglas, MIMechE, MIEE (20 January 1879 – 29 September 1952), was a British engineer and pioneer of the social credit economic reform movement.

Education and engineering career

C.H. Douglas was born in either Ed ...

of credit fame". From July 1930, he began to demand that government must be turned from a “talk-shop” into a “workshop.”

In 1992, the then UK prime minister, John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997, and as Member of Parliament ...

, examined Mosley’s ideas in order to find an unorthodox solution to the aftermath of the 1990-91 economic recession.

New Party

Dissatisfied with the Labour Party, Mosley founded the New Party.

Its early parliamentary contests, in the

Dissatisfied with the Labour Party, Mosley founded the New Party.

Its early parliamentary contests, in the 1931 Ashton-under-Lyne by-election

The 1931 Ashton-Under-Lyne by-election was held on 30 April. It was triggered by the death of the town's Labour MP, Albert Bellamy, and resulted in a victory for the Conservative candidate, Col John Broadbent.

This was the first election conteste ...

and subsequent by-elections, arguably had a spoiler effect in splitting the left-wing vote and allowing Conservative candidates to win. Despite this, the organisation gained support among many Labour and Conservative politicians who agreed with his corporatist economic policy, and among these were Aneurin Bevan

Aneurin "Nye" Bevan PC (; 15 November 1897 – 6 July 1960) was a Welsh Labour Party politician, noted for tenure as Minister of Health in Clement Attlee's government in which he spearheaded the creation of the British National Health ...

and Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as "Supermac", he ...

. Mosley's corporatism was complemented by Keynesianism, with Robert Skidelsky stating, "Keynesianism was his great contribution to fascism." It also gained the endorsement of the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' newspaper, headed at the time by Harold Harmsworth

Harold Sidney Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Rothermere, (26 April 1868 – 26 November 1940) was a leading British newspaper proprietor who owned Associated Newspapers Ltd. He is best known, like his brother Alfred Harmsworth, later Viscount Northcl ...

(later created 1st Viscount Rothermere).

The New Party increasingly inclined to fascist policies, but Mosley was denied the opportunity to get his party established when during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

the 1931 General Election was suddenly called – the party's candidates, including Mosley himself running in Stoke

Stoke is a common place name in the United Kingdom.

Stoke may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

The largest city called Stoke is Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire. See below.

Berkshire

* Stoke Row, Berkshire

Bristol

* Stoke Bishop

* Stok ...

which had been held by his wife, lost the seats they held and won none. As the New Party gradually became more radical and authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

, many previous supporters defected from it. Shortly after the 1931 election, Mosley was described by '' The Manchester Guardian'':

When Sir Oswald Mosley sat down after his Free Trade Hall speech in Manchester and the audience, stirred as an audience rarely is, rose and swept a storm of applause towards the platform – who could doubt that here was one of those root-and-branch men who have been thrown up from time to time in the religious, political and business story of England. First that gripping audience is arrested, then stirred and finally, as we have said, swept off its feet by a tornado ofperoration Dispositio is the system used for the organization of arguments in the context of Western classical rhetoric. The word is Latin, and can be translated as "organization" or "arrangement". It is the second of five canons of classical rhetoric (the ...yelled at the defiant high pitch of a tremendous voice.

Fascism

After his election failure in 1931, Mosley went on a study tour of the "new movements" of Italy's

After his election failure in 1931, Mosley went on a study tour of the "new movements" of Italy's Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

and other fascists, and returned convinced, particularly by Fascist Italy

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

's economic programme, that it was the way forward for Britain. He was determined to unite the existing fascist movements and created the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, fo ...

(BUF) in 1932. The BUF was protectionist, strongly anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

and nationalistic to the point of advocating authoritarianism. He claimed that the UK Labour Party was pursuing policies of "international socialism", while fascism's aim was "national socialism". It claimed membership as high as 50,000, and had the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' and '' Daily Mirror'' among its earliest supporters. The ''Mirror'' piece was a guest article by the ''Daily Mail'' owner Viscount Rothermere and an apparent one-off; despite these briefly warm words for the BUF, the paper was so vitriolic in its condemnation of European fascism

Fascism in Europe was the set of various fascist ideologies which were practised by governments and political organisations in Europe during the 20th century. Fascism was born in Italy following World War I, and other fascist movements, influen ...

that Nazi Germany added the paper's directors to a hit list in the event of a successful Operation Sea Lion. The ''Mail'' continued to support the BUF until the Olympia

The name Olympia may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Olympia'' (1938 film), by Leni Riefenstahl, documenting the Berlin-hosted Olympic Games

* ''Olympia'' (1998 film), about a Mexican soap opera star who pursues a career as an athlet ...

rally in June 1934.

John Gunther described Mosley in 1940 as "strikingly handsome. He is probably the best orator in England. His personal magnetism is very great". Among Mosley's supporters at this time included John Strachey, the novelist Henry Williamson, military theorist J. F. C. Fuller

Major-General John Frederick Charles "Boney" Fuller (1 September 1878 – 10 February 1966) was a senior British Army officer, military historian, and strategist, known as an early theorist of modern armoured warfare, including categorising pr ...

, and the future "Lord Haw Haw

Lord Haw-Haw was a nickname applied to William Joyce, who broadcast Nazi propaganda to the UK from Germany during the Second World War. The broadcasts opened with "Germany calling, Germany calling", spoken in an affected upper-class English acc ...

", William Joyce.

Mosley had found problems with disruption of New Party meetings, and instituted a corps of black-uniformed paramilitary stewards, the Fascist Defence Force, nicknamed "Blackshirts", like the Italian fascist Voluntary Militia for National Security

The Voluntary Militia for National Security ( it, Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts ( it, Camicie Nere, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the Natio ...

they were emulating. The party was frequently involved in violent confrontations and riots, particularly with communist and Jewish groups and especially in London. At a large Mosley rally at Olympia on 7 June 1934, his bodyguards' violence caused bad publicity. This and the Night of the Long Knives in Germany led to the loss of most of the BUF's mass support. Nevertheless, Mosley continued espousing anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

. At one of his New Party meetings in Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

in April 1935, he said, "For the first time I openly and publicly challenge the Jewish interests of this country, commanding commerce, commanding the Press, commanding the cinema, dominating the City of London, killing industry with their sweat-shops. These great interests are not intimidating, and will not intimidate, the Fascist movement of the modern age." The party was unable to fight the 1935 general election.

In October 1936, Mosley and the BUF attempted to march through an area with a high proportion of Jewish residents. Violence, since called the Battle of Cable Street, resulted between protesters trying to block the march and police trying to force it through. At length Sir

In October 1936, Mosley and the BUF attempted to march through an area with a high proportion of Jewish residents. Violence, since called the Battle of Cable Street, resulted between protesters trying to block the march and police trying to force it through. At length Sir Philip Game

Sir Philip Woolcott Game, (30 March 1876 – 4 February 1961) was a British Royal Air Force commander, who later served as Governor of New South Wales and Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis (London). Born in Surrey in 1876, Game was educa ...

, the Police Commissioner, disallowed the march from going ahead and the BUF abandoned it.

Mosley continued to organise marches policed by the Blackshirts, and the government was sufficiently concerned to pass the Public Order Act 1936, which, amongst other things, banned political uniforms and quasi-military style organisations and came into effect on 1 January 1937. In the London County Council elections in 1937, the BUF stood in three wards in East London (some former New Party seats), its strongest areas, polling up to a quarter of the vote. Mosley made most of the Blackshirt employees redundant, some of whom then defected from the party with William Joyce.

In October 1937 in Liverpool, he was knocked unconscious by two stones thrown by crowd members after he delivered a fascist salute to 8,000 people from the top of a van in Walton.

As the European situation moved towards war, the BUF began to nominate Parliamentary by-election candidates and launched campaigns on the theme of "Mind Britain's Business". Mosley remained popular as late as summer 1939. His Britain First rally at the Earls Court Exhibition Hall on 16 July 1939 was the biggest indoor political rally in British history, with a reported 30,000 attendees.

After the outbreak of war, Mosley led the campaign for a negotiated peace, but after the Fall of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second World ...

and the commencement of aerial bombardment during the Battle of Britain overall public opinion of him became hostile. In mid-May 1940, he was nearly wounded by an assault.

Internment

Unbeknown to Mosley, MI5 and theSpecial Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security and Intelligence (information gathering), intelligence in Policing in the United Kingdom, British, Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, ...

had deeply penetrated the BUF and were also monitoring him through listening devices. Beginning in 1934, they were increasingly worried that Mosley's noted oratory skills would convince the public to provide financial support to the BUF, enabling it to challenge the political establishment. His agitation was officially tolerated until the events of the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

in May 1940 made the government consider him too dangerous. Mosley, who at that time was focused on pleading for the British to accept Hitler's peace offer of March, was detained on 23 May 1940, less than a fortnight after Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

became Prime Minister. Mosley was interrogated for 16 hours by Lord Birkett but never formally charged with a crime, and was instead interned under Defence Regulation 18B. The other most active fascists in Britain met the same fate, resulting in the BUF's practical removal at an organised level from the United Kingdom's political stage. Mosley's wife, Diana, was also interned in June, shortly after the birth of their son ( Max Mosley); the Mosleys lived together for most of the war in a house in the grounds of Holloway prison. The BUF was proscribed

Proscription ( la, proscriptio) is, in current usage, a 'decree of condemnation to death or banishment' (''Oxford English Dictionary'') and can be used in a political context to refer to state-approved murder or banishment. The term originated ...

by the British Government later that year.

Mosley used the time in confinement to read extensively in classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

, particularly regarding politics and war, with a focus upon key historical figures. He refused visits from most BUF members, but on 18 March 1943, Dudley and Norah Elam (who had been released by then) accompanied Unity Mitford to see her sister Diana. Mosley agreed to be present because he mistakenly believed that it was Lady Redesdale, Diana and Unity's mother, who was accompanying Unity. The internment, particularly that of Lady Mosley, resulted in significant public debate in the press, although most of the public supported the Government's actions. Others demanded a trial, either in the hope it would end the detention or in the hope of a conviction. During his internment he developed what would become a lifelong friendship with fellow prisoner Cahir Healy, a Catholic Irish nationalist MP for the Northern Irish parliament.

In November 1943, the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, ordered the release of the Mosleys. After a fierce debate in the House of Commons, Morrison's action was upheld by a vote of 327–26. Mosley, who was suffering with phlebitis, spent the rest of the war confined under house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if all ...

and police supervision. On his release from prison, he first stayed with his sister-in-law Pamela Mitford, followed shortly by a stay at the Shaven Crown Hotel in Shipton-under-Wychwood. He then purchased Crux Easton House, near Newbury, with Diana. He and his wife remained the subject of much press attention.

Post-war politics

After the war, Mosley was contacted by his former supporters and persuaded to return to participation in politics. He formed the Union Movement, which called for a singlenation-state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

to cover the continent of Europe (known as Europe a Nation

Europe a Nation was a policy developed by the British fascist politician Oswald Mosley as the cornerstone of his Union Movement. It called for the integration of Europe into a single political entity. Although the idea failed to gain widespread ...

) and later attempted to launch a National Party of Europe

The National Party of Europe (NPE) was an initiative undertaken by a number of political parties in Europe during the 1960s to help increase cross-border co-operation and work towards European unity. Under the direction of Oswald Mosley, a pre-war ...

to this end. He had connections with the Italian neo-Fascist

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration sent ...

political party, Movimento Sociale Italiano

The Italian Social Movement ( it, Movimento Sociale Italiano, MSI) was a neo-fascist political party in Italy. A far-right party, it presented itself until the 1990s as the defender of Italian fascism's legacy, and later moved towards national c ...

, and contributed to a weekly Roman magazine, '' Asso di bastoni'', which was supported by his Europe a Nation. ''The New European'' has described Mosley as an "avowed Europhile". The Union Movement's meetings were often physically disrupted, as Mosley's meetings had been before the war, and largely by the same opponents. This led to his decision, in 1951, to leave Britain and live in Ireland. He responded to criticism of him abandoning his supporters in a hostile Britain for a life abroad by saying, "You don't clear up a dungheap from underneath it." In the 1950s, Mosley advocated for Africa to be divided into black and white areas, but the decolonisation of the 1960s put an end to this proposal.

Mosley was a key pioneer in the emergence of Holocaust denial. While not denying the existence of Nazi concentration camps, he claimed that they were a necessity to hold "a considerable disaffected population", where problems were caused by lack of supplies due to "incessant bombing" by the Allies, with bodies burned in gas chambers due to typhus outbreaks, rather than being created by the Nazis to exterminate people, and sought to discredit pictures taken from places like Buchenwald and Belsen. He also claimed that the Holocaust was to be blamed on the Jews and that Adolf Hitler knew nothing about it. He criticised the Nuremberg trials as "a zoo and a peep show".

In the wake of the 1958 Notting Hill race riots

The Notting Hill race riots were a series of racially motivated riots that took place in Notting Hill, England, between 29 August and 5 September 1958.

Background

Following the end of the Second World War, as a result of the losses during the wa ...

, Mosley briefly returned to Britain to stand in the 1959 general election at Kensington North

Kensington North was a parliamentary constituency centred on the Kensington district of west London. It returned one Member of Parliament (MP) to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United K ...

. He led his campaign stridently on an anti-immigration

Opposition to immigration, also known as anti-immigration, has become a significant political ideology in many countries. In the modern sense, immigration refers to the entry of people from one state or territory into another state or territory ...

platform, calling for forced repatriation of Caribbean immigrants as well as a prohibition upon mixed marriages. Mosley's final share of the vote was 8.1%. Shortly after his failed election campaign, Mosley permanently moved to Orsay, outside Paris.

In 1961, he took part in a debate at University College London about Commonwealth immigration, seconded by a young David Irving. He returned to politics one last time, contesting the 1966 general election at Shoreditch and Finsbury, and received 4.6% of the vote. After this, he retired and moved back to France, where he wrote his autobiography, ''My Life My Life may refer to:

Autobiographies

* ''Mein Leben'' (Wagner) (''My Life''), by Richard Wagner, 1870

* ''My Life'' (Clinton autobiography), by Bill Clinton, 2004

* ''My Life'' (Meir autobiography), by Golda Meir, 1973

* ''My Life'' (Mosley a ...

'' (1968). In 1968, he remarked in a letter to ''The Times'', "I am not, and never have been, a man of the right. My position was on the left and is now in the centre of politics."

In 1977, by which time he was suffering from Parkinson's disease, Mosley was nominated as a candidate for Rector of the University of Glasgow in which election he polled over 100 votes but finished bottom of the poll.

Mosley's political thought is believed to have influence on the organic farming movement in Great Britain. Henry Williamson, the agricultural writer and ruralist, put the theories of “blood and soil” into practice, which, in effect, acted as a demonstration farm for Mosley’s ideas for the BUF. In ''The Story of a Norfolk Farm'' (1941) Williamson recounts the physical and philosophical journey he undertook in turning the farm’s worn-out soil back into fertile land. The tone contained in this text is more politically overt than his nature works. Throughout the book, Williamson makes references to regular meetings he had held with his “Leader” (Mosley) and a group of like-minded agrarian thinkers. Lady Eve Balfour, a founder of the Soil Association, supported Mosley's proposals to abolish Church of England tithes on agricultural land (Mosley’s blackshirts “protected” a number of East Anglian farms in the 1930s from the bailiffs authorised to extract payments to the Church). Jorian Jenks, another founder of the Soil Association, was active within the Blackshirts and served as Mosley's agricultural adviser.

Personal life

Mosley had three children with his first wife Lady Cynthia Curzon. * Vivien Elisabeth Mosley (1921–2002); she married Desmond Francis Forbes Adam (1926–58) on 15 January 1949. Adam had been educated at Eton College and atKing's College King's College or The King's College refers to two higher education institutions in the United Kingdom:

*King's College, Cambridge, a constituent of the University of Cambridge

*King's College London, a constituent of the University of London

It ca ...

, Cambridge. The couple had two daughters, Cynthia and Arabella, and a son, Rupert.

* Nicholas Mosley (1923–2017) (later 3rd Baron Ravensdale

Baron Ravensdale, of Ravensdale in the County of Derby, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom.

History

The title was created on 2 November 1911 for the Conservative politician George Curzon, 1st Baron Curzon, with remainder, in def ...

a title inherited from his mother's family), and 7th Baronet of Ancoats; he was a successful novelist who wrote a biography of his father and edited his memoirs for publication.

* Michael Mosley (1932–2012), unmarried and without issue.

In 1924, Lady Cynthia Curzon joined the Labour Party, and was elected as the Labour MP for Stoke-on-Trent

Stoke-on-Trent (often abbreviated to Stoke) is a city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Staffordshire, England, with an area of . In 2019, the city had an estimated population of 256,375. It is the largest settlement ...

in 1929

This year marked the end of a period known in American history as the Roaring Twenties after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 ushered in a worldwide Great Depression. In the Americas, an agreement was brokered to end the Cristero War, a Catholic ...

. She later joined Oswald's New Party and lost the 1931 election in Stoke. She died in 1933 at 34 after an operation for peritonitis following acute appendicitis, in London.

Mosley had two children with his second wife, Diana Mitford (1910–2003):

* (Oswald) Alexander Mosley (1938–2005); father of Louis Mosley (born 1983)

* Max Mosley (1940–2021), who was president of the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) for 16 years

Death and funeral

Oswald Mosley died on 3 December 1980 at Orsay. His body was cremated in a ceremony held at the Père Lachaise Cemetery, and his ashes were scattered on the pond at Orsay. His son Alexander stated that they had received many messages of condolence but no abusive words. "All that was a very long time ago," he said.Archive and residences

Mosley's personal papers are held at the University of Birmingham's Special Collections Archive. Mosley's ancestral family residence,Rolleston Hall Rolleston Hall was a country house originally built in the early 17th century in Rolleston-on-Dove, Staffordshire which had been substantially renovated after a fire in 1871 and was demolished in 1928.

History

A house had stood on the Rolleston sit ...

in Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

, was demolished in 1928. Mosley and his first wife, Cynthia, also lived at Savay Farm, Denham. Immediately following his release in 1943, Mosley lived with his second wife, Diana, at Crux Easton, Hampshire In 1945, he moved to Crowood Farm, located near Marlborough, Wiltshire, which he ran. In November 1945, Mosley was summoned to court for allegedly causing unnecessary suffering to be caused to pigs by failing to provide adequate feeding and accommodation for them. When the decision of the court was announced, Mosley, who had pleaded not guilty, and summoned his own defence, was responsible for an outburst. The hearing lasted for five hours.

Mosley's residence in Fermoy, Co. Cork, Ireland, known as Ileclash House, was put up for sale in 2011, and again in 2016, 2018 and 2020. A Georgian style house, it was built in the 18th century and by 2011 was accompanied by 12 acres. It had fallen into a state of disrepair until it was purchased and restored by Mosley in the 1950s. In the same decade, he bought and restored Clonfert Palace, also in Ireland.

In popular culture

Alternative history fiction

Comics * In the ''Elseworlds

''Elseworlds'' was the publication imprint (trade name), imprint for American comic books produced by DC Comics for stories that took place outside the DC Universe Canon (fictional), canon. Elseworlds publications are set in alternate realitie ...

'' comic '' Superman: War of the Worlds'', Mosley becomes prime minister after the defeat of the Martian invasion of 1938.

Literature

* In Terrance Dicks' ''Doctor Who

''Doctor Who'' is a British science fiction television series broadcast by the BBC since 1963. The series depicts the adventures of a Time Lord called the Doctor, an extraterrestrial being who appears to be human. The Doctor explores the u ...

'' New Adventures

New Adventures is a British dance-theatre company. Founded by choreographer Matthew Bourne in 2001, the company developed from an earlier company Adventures in Motion Pictures, now dissolved.

History

Adventures in Motion Pictures (AMP) was est ...

novel '' Timewyrm: Exodus'', Prime Minister Mosley is shown addressing Britain's first National Socialist parliament.

* In Kim Newman's ''The Bloody Red Baron

''Anno Dracula: The Bloody Red Baron'', or simply ''The Bloody Red Baron'', is a 1995 alternate history/ horror novel by British author Kim Newman. It is the second book in the ''Anno Dracula'' series and takes place during the Great War, 30 ye ...

'', Mosley is shot down and killed in 1918 by Erich von Stalhein (from the Biggles series by W. E. Johns) and a character later comments that "a career has been ended before it was begun".

* In Philip Roth's ''The Plot Against America

''The Plot Against America'' is a novel by Philip Roth published in 2004. It is an alternative history in which Franklin D. Roosevelt is defeated in the presidential election of 1940 by Charles Lindbergh. The novel follows the fortunes of the R ...

'', a secret pact between Charles Lindbergh who has become president of the United States and Hitler includes an agreement to impose Mosley as the ruler of a German-occupied Britain with America's blessing after a ruse in which Lindbergh convinces Churchill to negotiate peace with Hitler, which deliberately fails – mirroring the dishonesty and repudiation of key Hitler-signed treaties, the Munich Conference

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

Accord and Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

* In C. J. Sansom

Christopher John Sansom (born 1952) is a British writer of Historical mystery, historical crime novels, best known for his Shardlake series, Matthew Shardlake series. He was born in Edinburgh and attended George Watson's College in that city, b ...

's novel '' Dominion'', the Second World War ends in June 1940, when the British government, under the leadership of prime minister Lord Halifax, signs a peace treaty with Nazi Germany in Berlin. By November 1952, Mosley is the home secretary in the cabinet of Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

, who leads a coalition government consisting of the pro-treaty factions of the Conservatives and Labour as well as the BUF. The government works closely and sympathises with the Nazi regime in Germany. Under Mosley's leadership, the police have become a feared force and an "Auxiliary Police" consisting mainly of British Union of Fascists thugs that has been set up to deal with political crime.

* In Lavie Tidhar's ''A Man Lies Dreaming'' (2014), Mosley is running for (and eventually becomes) prime minister, in a world where the Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

, rather than the Nazis, successfully overthrew the Weimar Republic in 1933.

* Mosley appears more than once in the works of Harry Turtledove.

** The '' Colonization trilogy'' sees Mosley, still an MP in 1963, spearheading an effort to pass legislation revoking the citizenship of all Jews; the plan fails in the short term.

** '' In the Presence of Mine Enemies'' (2003) empowers Mosley as British leader in a scenario in which Nazi Germany won the Second World War.

** In the ''Southern Victory'' series, Mosley is the minister of war under prime minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

in an authoritarian and revanchist Britain after the Entente

Entente, meaning a diplomatic "understanding", may refer to a number of agreements:

History

* Entente (alliance), a type of treaty or military alliance where the signatories promise to consult each other or to cooperate with each other in case o ...

lose the First Great War. Taking power around 1932, the Churchill/Mosley government joins the Kingdom of France and the Russian Empire in attacking the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

and the Central Powers in the Second Great War from 1941 to 1944 with disastrous results.

* In Guy Walters' ''The Leader'', Mosley has taken power as "The Leader" of Great Britain in 1937. King Edward VIII is still on the throne after his marriage, Winston Churchill is a prisoner on the Isle of Man, and prime minister Mosley is conspiring with Adolf Hitler about the fate of Britain's Jewish population.

* In the sixth book in Jacqueline Winspear

Jacqueline Winspear (born 30 April 1955) is a mystery writer, author of the ''Maisie Dobbs'' series of books exploring the aftermath of World War I. She has won several mystery writing awards for books in this popular series.

Personal life and ...

's Maisie Dobbs

''Maisie Dobbs'' is a 2003 mystery novel by Jacqueline Winspear. Set in England between 1910 and 1929, it features the title character Maisie Dobbs, a private investigator building her business in the aftermath of the First World War. Generally ...

series, ''Among the Mad'', Maisie's investigation takes her to a meeting of Oswald Mosley followers where violence ensues.

* In the 1944 Second World War novel '' Kaputt'' by Curzio Malaparte, Mosley appears in an important dream sequence. This happens in chapter IV of the book that is based on the writer's experiences in Moldavia, just before he recounts his first hand experiences of the Iași pogrom

The Iași pogrom (, sometimes anglicized as Jassy) was a series of pogroms launched by governmental forces under Marshal Ion Antonescu in the Romanian city of Iași against its Jewish community, which lasted from 29 June to 6 July 1941. Accord ...

.

* In Roy Carter's alternative history novel, ''The Man Who Prevented WW2'', Mosley wins the 1935 election, allies Britain with the Axis Powers, abolishes the monarchy and declares war on Ireland and France.

Film

*In '' Darkest Hour'' (2017), Churchill, played by Gary Oldman, discusses with his Outer Cabinet the possibility of Britain becoming a slave state of Nazi Germany under Mosley if the decision is made to pursue peace talks right before his "We Shall Never Surrender" speech.

*In the mockumentary ''It Happened Here

''It Happened Here'' (also known as ''It Happened Here: The Story of Hitler's England'') is a 1964 British black-and-white film written, produced and directed by Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo, who began work on the film as teenagers. The film ...

'' (1964), showing a Nazi-occupied Britain in the mid-1940s, Mosley is never mentioned by name. A British fascist leader resembling him is, however, shown in "documentary" footage from the 1930s. Mosley's portrait can be seen alongside Hitler's in government offices. The film's fictional Immediate Action Organisation seems to be inspired by Mosley's British Union of Fascists, with members referred to as "blackshirts" and the symbol of the BUF appearing on their uniforms.

Historical and modern day fiction

Film * In the film '' Pink Floyd: The Wall'' (1982), during the "In the Flesh In the Flesh may refer to:

Books

* ''In the Flesh'' (2009 graphic novel), a collection of stories by Koren Shadmi

Film and TV

* ''In the Flesh'' (1998 film), an American gay-themed murder mystery film

* ''In the Flesh'' (2003 film), an Indian ...

" segment, the character Pink (at this stage in the story, a modern Fascist leader) is dressed in a fashion similar to that of Mosley's.

* In the film '' The Remains of the Day'' (1993), the character Sir Geoffrey Wren is based loosely on Sir Oswald Mosley.

Literature

* Amanda K. Hale

Amanda K. Hale is a Canadian writer and daughter of Esoteric Hitlerist James Larratt Battersby.

Background

Born in England, she emigrated to Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She studied at Concordia University and received an M.A. in Creative Writi ...

's novel ''Mad Hatter'' (2019) features Mosley as her father James Larratt Battersby's leader in the BUF.

* Aldous Huxley's novel '' Point Counter Point'' (1928) features Everard Webley, a character who is similar to Mosley in the 1920s, before Mosley left the Labour Party.

* In H. G. Wells's novel '' The Holy Terror'' (1939), the Mosley-like character Lord Horatio Bohun is the leader of an organisation called the Popular Socialist Party. The character is principally motivated by vanity, and is removed from leadership and sent packing to Argentina.

* P. G. Wodehouse's Jeeves short-story and novel series includes the character Sir Roderick Spode from 1938 to 1971, who is a parody of Mosley.

Music

* Originally, Elvis Costello

Declan Patrick MacManus Order of the British Empire, OBE (born 25 August 1954), known professionally as Elvis Costello, is an English singer-songwriter and record producer. He has won multiple awards in his career, including a Grammy Award in ...

's song " Less Than Zero" (1977) was an attack on Mosley and his politics. Listeners in the United States had assumed that the "Mr. Oswald" in the lyrics was Lee Harvey Oswald, so Costello wrote an alternative lyric to refer to Kennedy

Kennedy may refer to:

People

* John F. Kennedy (1917–1963), 35th president of the United States

* John Kennedy (Louisiana politician), (born 1951), US Senator from Louisiana

* Kennedy (surname), a family name (including a list of persons with t ...

's assassin.

* On Mosley's release from prison in 1943, Ewan MacColl

James Henry Miller (25 January 1915 – 22 October 1989), better known by his stage name Ewan MacColl, was a folk singer-songwriter, folk song collector, labour activist and actor. Born in England to Scottish parents, he is known as one of the ...

wrote the song "The Leader's a Bleeder", set to the tune of the Irish song "The Old Orange Flute

The Old Orange Flute (also spelt Ould Orange Flute) is a folk song originating in Ireland. It is often associated with the Orange Order. Despite this, its humour ensured a certain amount of cross-community appeal, especially in the period before th ...

". The song suggests that Mosley had been treated relatively well in prison owing to his aristocratic background.

Periodicals

* In 2006, '' BBC History'' magazine selected Mosley as the 20th century's worst Briton.

Television

* The Channel 4 biographical miniseries '' Mosley'' (1997) starred Jonathan Cake.

* The satirical television programme '' Not the Nine O'Clock News'' lampooned the British media's favourable 1980 obituaries of Mosley in a comedic music video, "Baronet Oswald Ernald Mosley". The actors, dressed as Nazi punk

__NOTOC__

A Nazi punk is a neo-Nazi who is part of the punk subculture. The term also describes the related music genre, which is sometimes also referred to as hatecore. Nazi Punk music generally sounds like other forms of punk rock, but diffe ...

s, performed a punk rock eulogy to Mosley, interweaving some of the positive remarks by newspapers from all sides of the political spectrum, including '' The Times'' and '' The Guardian''.''Some of the Corpses are Amusing''. *The

BBC Wales

BBC Cymru Wales is a division of the BBC and the main public broadcaster in Wales.

It is one of the four BBC national regions, alongside the BBC English Regions, BBC Northern Ireland and BBC Scotland. Established in 1964, BBC Cymru Wales is ...

-produced 2010 revival of ''Upstairs Downstairs Upstairs Downstairs may refer to:

Television

*Upstairs, Downstairs (1971 TV series), ''Upstairs, Downstairs'' (1971 TV series), a British TV series broadcast on ITV from 1971 to 1975

*Upstairs Downstairs (2010 TV series), ''Upstairs Downstairs'' ...

'', set in 1936, included a storyline involving Mosley, the BUF and the Battle of Cable Street.

*Mosley, played by Sam Claflin, was the primary antagonist in the fifth and sixth series of the BBC crime drama '' Peaky Blinders''.

*Mosley was played by Jonathan McGuinness in the first series of the BBC war drama

In film and television, drama is a category or genre of narrative fiction (or semi-fiction) intended to be more serious than humorous in tone. Drama of this kind is usually qualified with additional terms that specify its particular super-gen ...

'' World on Fire''.

See also

* The European * Houston Stewart ChamberlainReferences

Notes Citations Bibliography * * * * * Further reading * * * Gottlieb, Julie V. (2000). Feminine Fascism: Women in Britain's Fascist Movement 1923-1945. London: I.B. Tauris. * * * *External links

Friends of Oswald Mosley

at oswaldmosley.com, containing archives of his speeches and books * * * * * (last accessible, 23 October 2017) * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mosley, Oswald 1896 births 1980 deaths 16th The Queen's Lancers officers Anti-Masonry Antisemitism in the United Kingdom Baronets in the Baronetage of Great Britain British Army personnel of World War I British Holocaust deniers British political party founders British Union of Fascists politicians British white supremacists Chancellors of the Duchy of Lancaster Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Deaths from Parkinson's disease English expatriates in France English far-right politicians English memoirists Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Independent Labour Party National Administrative Committee members Independent members of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Labour Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Mosley baronets Oswald Neurological disease deaths in France Pan-European nationalism People detained under Defence Regulation 18B People educated at West Downs School People educated at Winchester College People from Burton upon Trent Racism in the United Kingdom Royal Flying Corps officers Sexism in the United Kingdom UK MPs 1918–1922 UK MPs 1922–1923 UK MPs 1923–1924 UK MPs 1924–1929 UK MPs 1929–1931 Union Movement politicians People_with_Parkinson's_disease