Sir John Anderson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Anderson, 1st Viscount Waverley, (8 July 1882 – 4 January 1958) was a Scottish civil servant and politician who is best known for his service in the

Anderson sailed from England on the on 10 March 1932, accompanied by William Paterson, Mary Anderson and Nellie Mackenzie; his son Alastair was studying medicine at Pembroke College, Cambridge. Anderson arrived in Calcutta on 29 March, and was greeted with a 17-gun salute. The position came with an annual salary of approximately , a sumptuary allowance of and a grant of to cover his staff's wages. In addition to his personal staff he had 120 servants, a seventy-man mounted bodyguard, and a brass band. There were cars, two special trains, a yacht and a house boat.

There were government houses in Raj Bhavan, Kolkata, Calcutta, Raj Bhavan, Darjeeling, Darjeeling, Barrackpore and Bangabhaban, Dacca. The primary residence of the governor was in Calcutta, but when the weather became hot in April the governor and his staff would move to Darjeeling, returning when the Monsoon of South Asia, monsoon broke in June. Each year they would spend a month in Dacca in fulfilment of a promise made when Partition of Bengal (1905), Bengal was reunited in 1911. They would then go back to Darjeeling, remaining until it became cold, and then return to Calcutta. Anderson visited all twenty-six districts of Bengal, usually travelling by train, but sometimes by river on a towed barge he named the ''Mary Anderson (yacht), Mary Anderson'' after his daughter. He regularly attended church services at St Andrew's Church in Calcutta and St Columba's Church in Darjeeling. On 26 March 1933, he was ordained as an Elder of the Church of Scotland at St Andrew's.

Anderson recognised that the root of Bengal's problems was financial. The chief source of revenue was collected under the terms of the Permanent Settlement of Bengal that had been concluded by Lord Cornwallis in 1793 and taxed landowners known as zamindars based on the value of their land. Other forms of taxation, such as income tax and export duties were collected by the central government and little was returned to Bengal. As a result, public infrastructure, such as police, education and health, had been run down. The export duty on the jute trade was particularly unfair, as it had been imposed during the Great War when the trade was booming, but by 1932 the trade was in decline due to competition from paper and cotton bags. The global Great Depression caused the prices of agricultural commodities to fall. Anderson negotiated a revision of the financial arrangements with Sir Otto Niemeyer, under which the provinces retained half of their income tax and jute duty receipts and provincial debts to the central government were cancelled.

The other major task that Anderson confronted was dealing with terrorism. Collective fines were imposed on areas that sheltered or supported terrorists, and the funds used to increase the police presence. He was aware that he was a target, but as the King's representative he continued to make public appearances, travelling in a Rolls-Royce Limited, Rolls-Royce or an open horse-drawn carriage. On 4 May 1934 a would-be assassin fired at Anderson but the bullet passed between him and Nellie Mackenzie, and the man was wrestled to the ground by Charles William Tandy-Green. A second man fired but also missed Anderson, though wounded the ankle of a teenager sitting behind the governor, and was tackled by Bhupendra Narayan Singh. Tandy-Green and Singh were awarded the Empire Gallantry Medal, which they exchanged for the George Cross in 1940. Five other members of the gang attempted to escape but were captured. The would-be assassins were sentenced to hang, but Anderson commuted the sentences of two of them. By 1935 he was described as the world's most-shot-at-man, having survived three assassination attempts. Anderson tackled the problem of what to do with détenus, individuals who had been detained without trial on suspicion of terrorism by giving them training for jobs in agriculture and manufacturing.

Anderson carried out a series of economic and social programs. He waged a campaign against water hyacinth, an invasive plant species that threatened to clog Bengal's waterways. He regulated jute production through a system of voluntarily restrictions. He established a panel that examined the problem of rural debt, and sponsored legislation to reduce the debts of farmers. He introduced compulsory primary school education. The Government of India Act 1935 was scheduled to become operative on 1 April 1937, soon after his five-year term of office was due to expire, but at the request of the Secretary of State for India, the Lawrence Dundas, 2nd Marquess of Zetland, Marquess of Zetland, and the List of governors-general of India, viceroy, the Victor Hope, 2nd Marquess of Linlithgow, Marquess of Linlithgow, Anderson agreed to a six-month extension in order to oversee the transition to self-government, but declined a request from Zetland for his term to be further extended. For his services in India, Anderson was appointed a Knight Grand Commander of the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India (GCSI) on 15 December 1937, and was made a Privy Counsellor in the 1938 New Year Honours.

Anderson sailed from England on the on 10 March 1932, accompanied by William Paterson, Mary Anderson and Nellie Mackenzie; his son Alastair was studying medicine at Pembroke College, Cambridge. Anderson arrived in Calcutta on 29 March, and was greeted with a 17-gun salute. The position came with an annual salary of approximately , a sumptuary allowance of and a grant of to cover his staff's wages. In addition to his personal staff he had 120 servants, a seventy-man mounted bodyguard, and a brass band. There were cars, two special trains, a yacht and a house boat.

There were government houses in Raj Bhavan, Kolkata, Calcutta, Raj Bhavan, Darjeeling, Darjeeling, Barrackpore and Bangabhaban, Dacca. The primary residence of the governor was in Calcutta, but when the weather became hot in April the governor and his staff would move to Darjeeling, returning when the Monsoon of South Asia, monsoon broke in June. Each year they would spend a month in Dacca in fulfilment of a promise made when Partition of Bengal (1905), Bengal was reunited in 1911. They would then go back to Darjeeling, remaining until it became cold, and then return to Calcutta. Anderson visited all twenty-six districts of Bengal, usually travelling by train, but sometimes by river on a towed barge he named the ''Mary Anderson (yacht), Mary Anderson'' after his daughter. He regularly attended church services at St Andrew's Church in Calcutta and St Columba's Church in Darjeeling. On 26 March 1933, he was ordained as an Elder of the Church of Scotland at St Andrew's.

Anderson recognised that the root of Bengal's problems was financial. The chief source of revenue was collected under the terms of the Permanent Settlement of Bengal that had been concluded by Lord Cornwallis in 1793 and taxed landowners known as zamindars based on the value of their land. Other forms of taxation, such as income tax and export duties were collected by the central government and little was returned to Bengal. As a result, public infrastructure, such as police, education and health, had been run down. The export duty on the jute trade was particularly unfair, as it had been imposed during the Great War when the trade was booming, but by 1932 the trade was in decline due to competition from paper and cotton bags. The global Great Depression caused the prices of agricultural commodities to fall. Anderson negotiated a revision of the financial arrangements with Sir Otto Niemeyer, under which the provinces retained half of their income tax and jute duty receipts and provincial debts to the central government were cancelled.

The other major task that Anderson confronted was dealing with terrorism. Collective fines were imposed on areas that sheltered or supported terrorists, and the funds used to increase the police presence. He was aware that he was a target, but as the King's representative he continued to make public appearances, travelling in a Rolls-Royce Limited, Rolls-Royce or an open horse-drawn carriage. On 4 May 1934 a would-be assassin fired at Anderson but the bullet passed between him and Nellie Mackenzie, and the man was wrestled to the ground by Charles William Tandy-Green. A second man fired but also missed Anderson, though wounded the ankle of a teenager sitting behind the governor, and was tackled by Bhupendra Narayan Singh. Tandy-Green and Singh were awarded the Empire Gallantry Medal, which they exchanged for the George Cross in 1940. Five other members of the gang attempted to escape but were captured. The would-be assassins were sentenced to hang, but Anderson commuted the sentences of two of them. By 1935 he was described as the world's most-shot-at-man, having survived three assassination attempts. Anderson tackled the problem of what to do with détenus, individuals who had been detained without trial on suspicion of terrorism by giving them training for jobs in agriculture and manufacturing.

Anderson carried out a series of economic and social programs. He waged a campaign against water hyacinth, an invasive plant species that threatened to clog Bengal's waterways. He regulated jute production through a system of voluntarily restrictions. He established a panel that examined the problem of rural debt, and sponsored legislation to reduce the debts of farmers. He introduced compulsory primary school education. The Government of India Act 1935 was scheduled to become operative on 1 April 1937, soon after his five-year term of office was due to expire, but at the request of the Secretary of State for India, the Lawrence Dundas, 2nd Marquess of Zetland, Marquess of Zetland, and the List of governors-general of India, viceroy, the Victor Hope, 2nd Marquess of Linlithgow, Marquess of Linlithgow, Anderson agreed to a six-month extension in order to oversee the transition to self-government, but declined a request from Zetland for his term to be further extended. For his services in India, Anderson was appointed a Knight Grand Commander of the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India (GCSI) on 15 December 1937, and was made a Privy Counsellor in the 1938 New Year Honours.

Mary Anderson and Nellie Mackenzie had preceded Anderson to England and rented a house at 11 Chepstow Villas in Notting Hill for nine guinea (coin), guineas a week (). Although this was a bargain, Anderson feared that his income would not be sufficient to keep up the rental payments. Before leaving Calcutta he accepted a directorship from the Midland Bank, and after his return to England he joined the boards of Vickers, Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) and the Employers Liability Assurance Corporation. The directors' fees gave him an annual income of around . He was approached by members of the board of Imperial Airways who were seeking a new full-time chairman with an offer of more than twice that amount. However, Chamberlain stipulated that if he accepted then he would have to resign his other directorships and his seat in the House of Commons at the next general election, which was due in 1940. Anderson therefore declined the appointment. He would sometimes go horse riding in Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park with Mary Anderson, but sought a more rural environment. He disposed of the house in Chepstow Villas in October and bought a property near Merstham in December. During the week he lived with William Paterson and his wife.

In May 1938, Hoare, who was now the

Mary Anderson and Nellie Mackenzie had preceded Anderson to England and rented a house at 11 Chepstow Villas in Notting Hill for nine guinea (coin), guineas a week (). Although this was a bargain, Anderson feared that his income would not be sufficient to keep up the rental payments. Before leaving Calcutta he accepted a directorship from the Midland Bank, and after his return to England he joined the boards of Vickers, Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) and the Employers Liability Assurance Corporation. The directors' fees gave him an annual income of around . He was approached by members of the board of Imperial Airways who were seeking a new full-time chairman with an offer of more than twice that amount. However, Chamberlain stipulated that if he accepted then he would have to resign his other directorships and his seat in the House of Commons at the next general election, which was due in 1940. Anderson therefore declined the appointment. He would sometimes go horse riding in Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park with Mary Anderson, but sought a more rural environment. He disposed of the house in Chepstow Villas in October and bought a property near Merstham in December. During the week he lived with William Paterson and his wife.

In May 1938, Hoare, who was now the

Once the Blitz began, the contingencies that Anderson had been preparing for were realised, and Anderson came under heavy attack in the press and the House of Commons over the issue of not providing deep shelters. On 8 October 1940, in a reshuffle precipitated by Chamberlain's resignation due to ill-health, Anderson was replaced by

Once the Blitz began, the contingencies that Anderson had been preparing for were realised, and Anderson came under heavy attack in the press and the House of Commons over the issue of not providing deep shelters. On 8 October 1940, in a reshuffle precipitated by Chamberlain's resignation due to ill-health, Anderson was replaced by

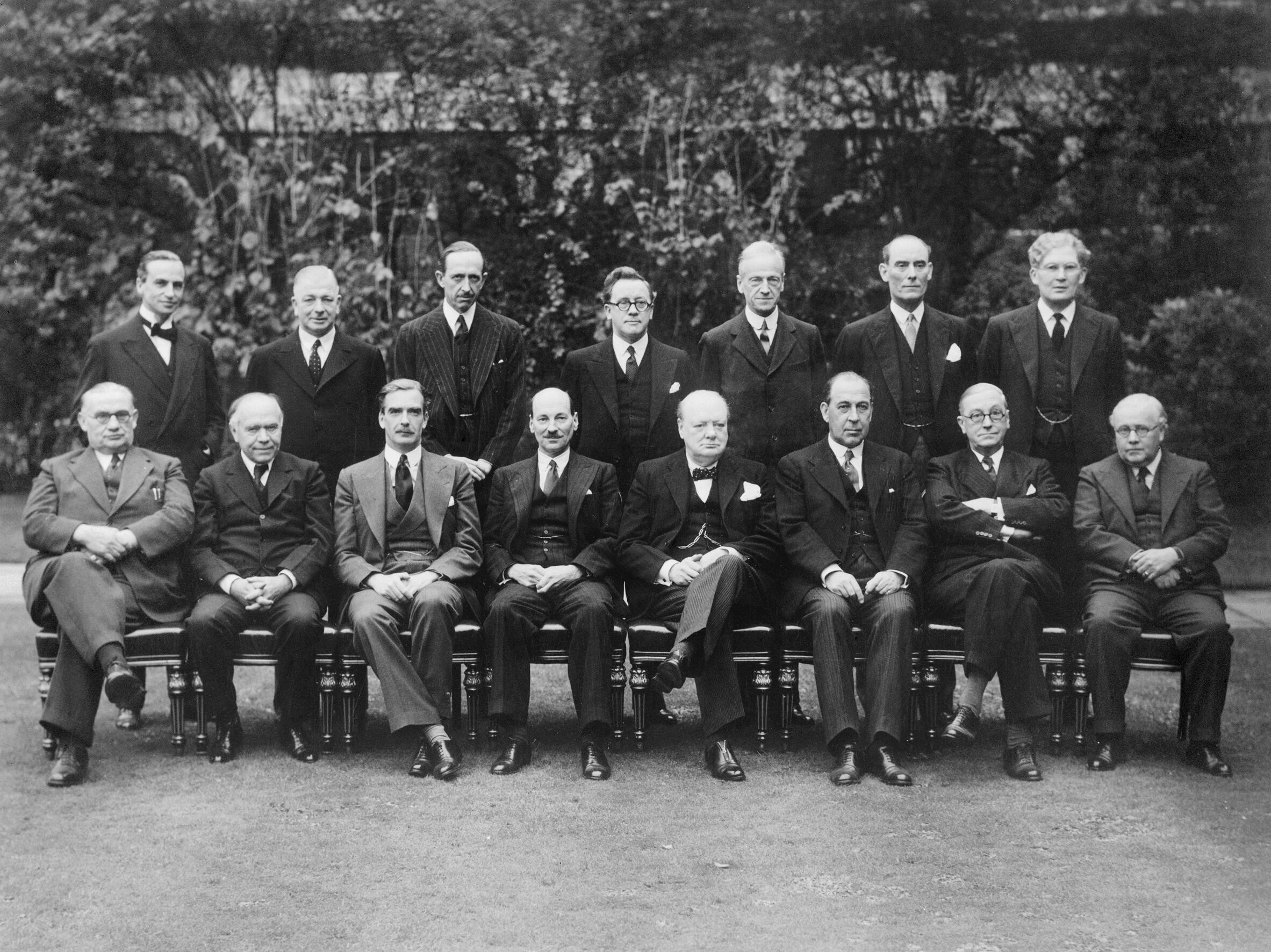

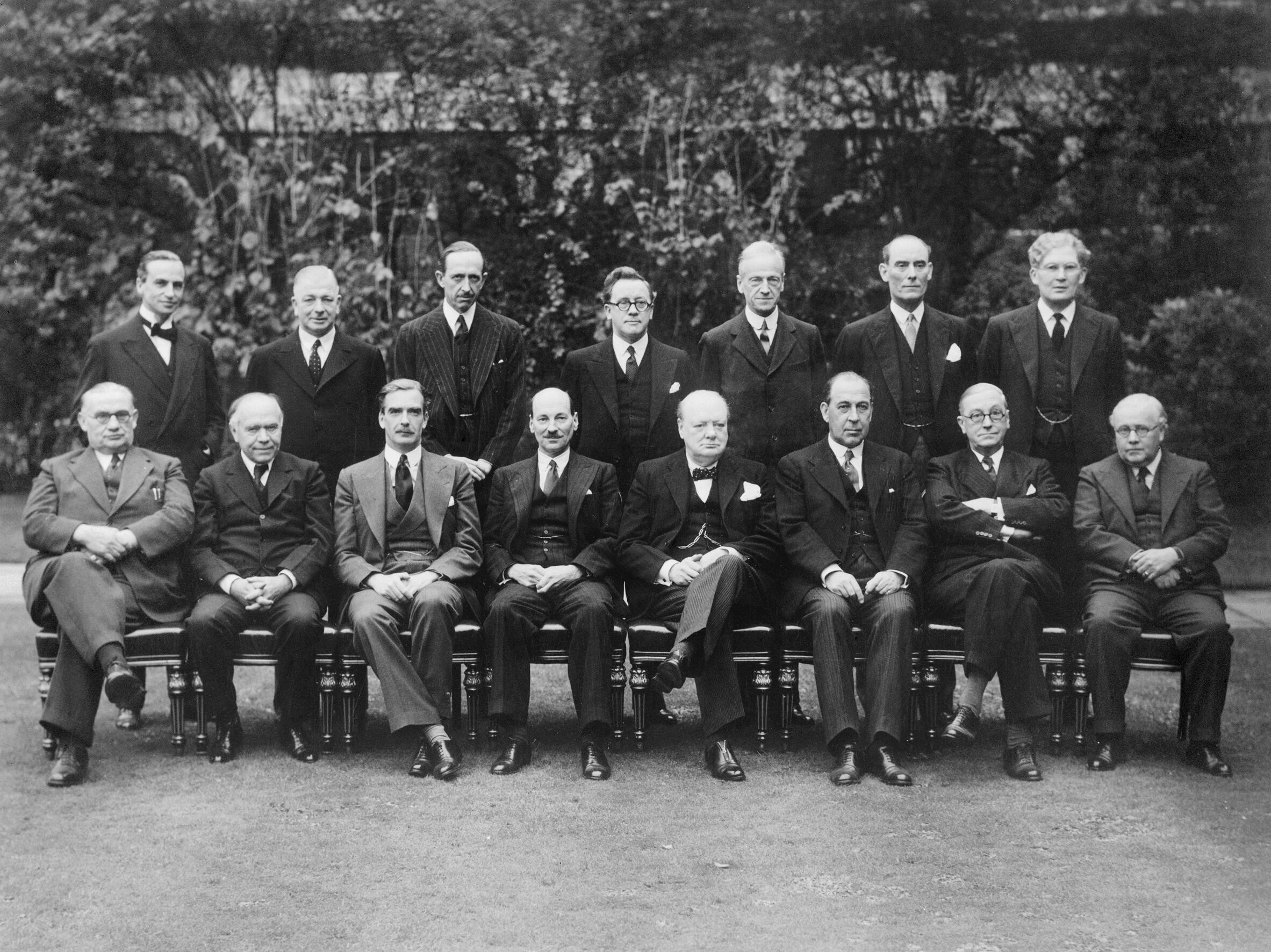

War Cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senio ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, for which he was nicknamed the "Home Front Prime Minister". He served as Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

, Lord President of the Council and Chancellor of the Exchequer. The Anderson shelter

Air raid shelters are structures for the protection of non-combatants as well as combatants against enemy attacks from the air. They are similar to bunkers in many regards, although they are not designed to defend against ground attack (but many ...

s are named after him.

A graduate of the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

and the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 Decemb ...

where he studied the chemistry of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

, Anderson joined the Civil Service in 1905, and worked in the West African Department of the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of c ...

. During the Great War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

he headed the staff of the Ministry of Shipping. He served as Under-Secretary for Ireland

The Under-Secretary for Ireland (Permanent Under-Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland) was the permanent head (or most senior civil servant) of the British administration in Ireland prior to the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922 ...

from 1921 to 1922 during its transition to independence, and as the Permanent Under-Secretary of State at the Home Office

The Permanent Under-Secretary of State of the Home Office is the permanent secretary of the Home Office, the most senior civil servant in the department, charged with running its affairs on a day-to-day basis.

Home Office Permanent Secretaries

...

from 1922 to 1931 he had to deal with the General Strike of 1926

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British governmen ...

. As Governor of Bengal from 1932 to 1937, he instituted social and financial reforms, and narrowly escaped an assassination attempt.

In early 1938, Anderson was elected to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

by the Scottish Universities as a National Independent Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

, and was a non-party supporter of the National Government. In October 1938 he entered Neville Chamberlain's Cabinet as Lord Privy Seal. In that capacity, he was put in charge of air raid preparations. He initiated the development of the Anderson shelter, a small sheet metal cylinder made of prefabricated

Prefabrication is the practice of assembling components of a structure in a factory or other manufacturing site, and transporting complete assemblies or sub-assemblies to the construction site where the structure is to be located. The term ...

pieces which could be assembled in a garden and partially buried to protect against bomb blast.

After the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Anderson returned to hold the joint portfolio of Home Secretary and Minister of Home Security, a position in which he served under Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

. He retained responsibility for civil defence. In October 1940, he exchanged places with Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the UK Cabinet as member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Minis ...

and became Lord President of the Council. In July 1941 as Lord President of the Council he was appointed as minister responsible for the British effort to build an atomic bomb, known as the Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the ...

project. He became the Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1943 and remained in the post until the Labour Party's victory in the general election in July 1945.

Anderson left the Commons when the university constituencies

A university constituency is a constituency, used in elections to a legislature, that represents the members of one or more universities rather than residents of a geographical area. These may or may not involve plural voting, in which voters a ...

were abolished at the 1950 general election. He became Chairman of the Port of London Authority in 1946 and the Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Ope ...

in March the same year. He rejected an offer to join Churchill's peacetime administration when it was formed in 1951, and was created Viscount Waverley of Westdean

Cuckmere Valley is a civil parish in the Wealden District of East Sussex, England. As its name suggests, the parish consists of a number of small settlements in the lower reaches of the River Cuckmere.

The settlements

There are three villages ...

in the County of Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

in 1952.

Early life

John Anderson was born at his parents' home at 1 Livingstone Place, Edinburgh, on 8 July 1882, the oldest child of David Alexander Pearson Anderson, a printer and stationer, and his wife Janet Kilgour Briglmen. He had three younger siblings: a brother, Charles, who died from meningitis in infancy, and sisters Catherine (Katie) and Janet (Nettie). The family moved toBraid Hills

The Braid Hills form an area towards the south-western edge of Edinburgh, Scotland.

The hills themselves are largely open space. Housing in the area is mostly confined to detached villas, and some large terraced houses. The ''Braid Hills Hotel ...

in May 1890. He attended George Watson's College

George Watson's College is a co-educational independent day school in Scotland, situated on Colinton Road, in the Merchiston area of Edinburgh. It was first established as a hospital school in 1741, became a day school in 1871, and was merg ...

in Edinburgh, where he was dux of the school, earning prizes for Anglo-Saxon, Old English, and Modern Languages.

In October 1899, Anderson sat the examination for students entering the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

, which determined order of merit for scholarships and bursaries. He was ranked eleventh, and awarded a bursary of . In his first year, he was ranked first in his class in mathematics and natural philosophy. In November 1900, the family moved to Eskbank. The previous owner of their new home had been an amateur astronomer and Anderson took over a room with a large telescope.

A neighbour, Andrew Mackenzie, had five daughters, and Anderson became the boyfriend of one of them, Christina (Chrissie) Mackenzie. In 1902 he took a bicycle tour of France and Switzerland, during which he wrote frequently to Chrissie. He graduated the following year with distinction in mathematics, physics and chemistry, earning a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

degree, and first class honours in mathematics and natural philosophy, earning a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Th ...

degree.

The Anderson, Briglmen and Mackenzie families holidayed together in summer of 1903. On 29 August they were bathing in the River Ythan when a freak wave suddenly swept Nettie Anderson and Chrissie's sister Nellie Mackenzie into deep water. Nellie was rescued but Nettie drowned. Anderson and Chrissie were on their way to join the group at the time of the accident, but it fell to him to identify the body and inform his parents.

Along with fellow Scotsmen Joseph Henry Maclagen Wedderburn

Joseph Henry Maclagan Wedderburn FRSE FRS (2 February 1882 – 9 October 1948) was a Scottish mathematician, who taught at Princeton University for most of his career. A significant algebraist, he proved that a finite division algebra is a fi ...

, Forsyth James Wilson and William Wilson, Anderson went to the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 Decemb ...

in Germany, where he intended to study physical chemistry under Wilhelm Ostwald

Friedrich Wilhelm Ostwald (; 4 April 1932) was a Baltic German chemist and philosopher. Ostwald is credited with being one of the founders of the field of physical chemistry, with Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff, Walther Nernst, and Svante Arrhen ...

. When he arrived he found that Ostwald had abandoned chemistry, so Anderson studied under Robert Luther instead. He chose to examine the chemistry of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

. Although Henri Becquerel

Antoine Henri Becquerel (; 15 December 1852 – 25 August 1908) was a French engineer, physicist, Nobel laureate, and the first person to discover evidence of radioactivity. For work in this field he, along with Marie Skłodowska-Curie and Pie ...

had discovered that uranium had radioactive properties in 1896, Anderson studied only its chemical properties. On his return to Edinburgh he wrote a paper on the subject, but this was not a PhD thesis.

Civil Service career

Colonial Office

Although Anderson was a brilliant student, winning numerous prizes, he decided to forsake a career in science for one in the Civil Service. At the time this was the normal career path for graduates of the University of Edinburgh, and his father advised him that if he wished to marry Chrissie the Civil Service would offer greater job security. To prepare, he took an honours course in economics and political science. In July 1905, he travelled to London with a fellow candidate, Alexander Gray and sat the Britishcivil service examination

Civil service examinations are examinations implemented in various countries for recruitment and admission to the civil service. They are intended as a method to achieve an effective, rational public administration on a merit system for recruitin ...

.

In those days a candidate could take tests in as many subjects as they liked, and Anderson took fourteen, earning a score of 4566 out of a possible 7500, which was the highest score that year and the second highest ever; Gray came second with a score of 4107 out of 7900. Anderson was offered the choice of joining the Home Civil Service or the Indian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 300 million p ...

. Most candidates preferred the latter, as salaries and allowances were higher, but Anderson's parents did not want him to leave Britain, and he did not want to subject Chrissie to the rigours of life in India. He therefore joined the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of c ...

as a Second Class Clerk on an annual salary of .

Anderson commenced work at the Colonial Office on 23 October 1905, in the West African Department. He was known in the department as "young John Anderson" to distinguish him from another John Anderson who became the Governor of the Straits Settlements

The governor of the Straits Settlements was appointed by the British East India Company until 1867, when the Straits Settlements became a Crown colony. Thereafter the governor was appointed by the Colonial Office. The position existed from 1826 ...

. In London, Anderson shared accommodation with Gray and William Paterson, a family friend from Eskbank. On 2 April 1907, he married Chrissie at St Andrew's Church in Drumsheugh Gardens, Edinburgh; Gray was his best man and Chrissie's sister Kate and William Paterson were witnesses. The newlywed couple rented a house in Sutton, London. They had two children: David Alastair Pearson on 18 February 1911, and Mary Mackenzie on 3 February 1916.

Anderson served on Sir Kenelm Digby

Sir Kenelm Digby (11 July 1603 – 11 June 1665) was an English courtier and diplomat. He was also a highly reputed natural philosopher, astrologer and known as a leading Roman Catholic intellectual and Blackloist. For his versatility, he is d ...

's 1908 Committee on Northern Nigerian Lands. This did not involve travel to Nigeria, but the following year he went to Hamburg to meet with his German counterparts at the Hamburg Colonial Institute, where his fluency in German was useful. In 1911 he was the secretary of Lord Emmott's departmental committee that recommended the introduction of a distinctive local currency in British West Africa.

Great War

In 1912, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lloyd George, introducedNational Insurance

National Insurance (NI) is a fundamental component of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It acts as a form of social security, since payment of NI contributions establishes entitlement to certain state benefits for workers and their fami ...

, the start of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. A new government department was created to administer it, chaired by Sir Robert Morant. Anderson and Gray joined the new department. When the position of secretary of the National Insurance Commission fell vacant in May 1913, Anderson was appointed to the position over the head of many more senior civil servants. Anderson formed a good working relationship with the notoriously difficult Morant. "The trouble with young John Anderson", Morant lamented, "is that he is always so damned right."

Following the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914, Anderson was involved in securing supplies of medical and surgical implements that had hitherto been imported from Germany. He summoned a group of experts to analyse and produce arsphenamine

Arsphenamine, also known as Salvarsan or compound 606, is a drug that was introduced at the beginning of the 1910s as the first effective treatment for syphilis, relapsing fever, and African trypanosomiasis.

This organoarsenic compound was the f ...

, known as "606", a drug formerly sourced from Bayer in Germany. They went on to produce other substances, including aspirin

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat inc ...

. Anderson registered for service under the Derby Scheme but was placed on the Army Reserve. This did not prevent a young woman from presenting him with a white feather

The white feather is a widely recognised propaganda symbol. It has, among other things, represented cowardice or conscientious pacifism; as in A. E. W. Mason's 1902 book, '' The Four Feathers''. In Britain during the First World War it was of ...

.

Lloyd George became the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern ...

on 7 December 1916, and one of his first acts was to create a Ministry of Shipping under Sir Joseph Maclay, and Morant agreed to release Anderson to become its secretary on 8 January 1917. Although it was not his idea, Anderson recognised the value of an Allied Maritime Transport Council The Allied Maritime Transport Council (AMTC) was an international agency created during World War I to coordinate shipping between the allied powers of France, Italy, Great Britain, and the United States. The council (based in London) was formed at ...

, and threw his support behind it. After the Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

, the Ministry of Shipping became embroiled in a controversy over the continuance of the blockade of Germany and the shipment of relief supplies for starving civilians. In the end the Germans agreed to turn all their ships over to the Allies to carry supplies. The vessels were eventually retained as reparations. For his wartime service with the Ministry of Shipping, Anderson was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath in the 1918 New Year Honours

The 1918 New Year Honours were appointments by King George V to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of the British Empire. The appointments were published in ''The London Gazette'' and ''The Times'' in Ja ...

, and was promoted to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as o ...

in the 1919 Birthday Honours.

Anderson became a secretary of the Local Government Board

The Local Government Board (LGB) was a British Government supervisory body overseeing local administration in England and Wales from 1871 to 1919.

The LGB was created by the Local Government Board Act 1871 (C. 70) and took over the public health a ...

in April 1919, but in July it was merged with the Health Insurance Commission to form the Ministry of Health, and Anderson became the second secretary under Morant, who had requested Anderson's appointment as his deputy. However, Anderson did not remain in that position for long either, for on 1 October 1919 he was appointed the Chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue

The Inland Revenue was, until April 2005, a department of the British Government responsible for the collection of direct taxation, including income tax, national insurance contributions, capital gains tax, inheritance tax, corporation ta ...

, with an annual salary of plus war bonus, which was raised to plus on 1 March 1920.

Ireland

Chrissie died on 9 May 1920 during an operation forcancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

, leaving Anderson a widower with two young children. Nellie Mackenzie, who was training to be a nurse at St Thomas' Hospital, gave up her career to care for them. On 16 May, Anderson became Under-Secretary for Ireland

The Under-Secretary for Ireland (Permanent Under-Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland) was the permanent head (or most senior civil servant) of the British administration in Ireland prior to the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922 ...

. He was also the HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and ...

representative, and he became a Privy Counsellor of Ireland on 3 June 1920. The administrative arrangements were unorthodox: he did not supersede his predecessor, James Macmahon, but shared the position with him. They were answerable to the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Sir Hamar Greenwood, but as a cabinet minister, Greenwood was located in London; Field Marshal French, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (known as the viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

), had wielded special executive powers in 1918 and 1919, but in 1920 reverted to the normal figurehead powers of that post. Anderson therefore wielded great executive power. He had two assistant under-secretaries, Alfred William Cope and Mark Sturgis.

Over eighty members of the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

had been killed during the previous year, and both numbers and morale were low. Anderson oversaw a recruitment campaign among ex-servicemen in England, Scotland and Wales. There were insufficient uniforms for them all, so they wore a mixture of khaki Army service dress

Service dress uniform is the informal type of uniform used by military, police, fire and other public uniformed services for everyday office, barracks and non-field duty purposes and sometimes for ceremonial occasions. It frequently consists of ...

and dark green Royal Irish Constabulary uniforms, giving rise to the nickname "Black and Tans

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have ...

". Major General Hugh Tudor

Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Hugh Tudor, KCB, CMG (14 March 1871 – 25 September 1965) was a British soldier who fought as a junior officer in the Second Boer War (1899–1902), and as a senior officer in the First World War (1914–18), bu ...

was given a free hand to reorganise and reequip the constabulary, and facilitated cooperation between the constabulary and the military.

In the face of an insurgency

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority waged by small, lightly armed bands who practice guerrilla warfare from primarily rural base areas. The key descriptive feature of insurgency is its asymmetric nature: small irr ...

, Anderson strove to avoid the appearance that Britain was engaged in a war of reconquest. He travelled in an armoured car with a police escort, and carried a revolver. He was engaged in peace talks with the Sinn Fein

In the philosophy of language, the distinction between sense and reference was an idea of the German philosopher and mathematician Gottlob Frege in 1892 (in his paper "On Sense and Reference"; German: "Über Sinn und Bedeutung"), reflecting the ...

, but unlike Cope he was not in his element. A settlement was brokered, and on 16 January 1922, the viceroy ( Viscount FitzAlan) formally handed over power to the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

. For his service in Ireland, Anderson was made an additional Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) in the 1923 New Year Honours.

Home Office

All the while Anderson was in Ireland, he was still nominally the Chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue, and he returned to this role in January 1922. But not for long; in March Sir Edward Troup, thePermanent Under-Secretary of State at the Home Office

The Permanent Under-Secretary of State of the Home Office is the permanent secretary of the Home Office, the most senior civil servant in the department, charged with running its affairs on a day-to-day basis.

Home Office Permanent Secretaries

...

, retired and Anderson was appointed to succeed him. At the time the Home office had seven divisions, each with its own Assistant Secretary: Aliens Control, Children and Probation, Crime, Factories and Shops, Channel Islands, Northern Ireland, and Police. Anderson worked an eight-hour day, from 10:15 in the morning to 18:15 each night, with an hour and a half for lunch.

Through the Northern Ireland Division, Anderson continued to be involved with Irish issues. He helped negotiate the border between the new Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

in 1923. He also chaired the 1925 Committee of Imperial Defence subcommittee on air raid precautions. That year also saw Red Friday

On Friday 31 July 1925 the British government agreed to the demands of the Miners Federation of Great Britain to provide a subsidy to the mining industry to maintain miners' wages. The '' Daily Herald'' called this day Red Friday; a union defeat ...

, 31 July 1925, when the government capitulated to the demands of the Miners Federation of Great Britain

The Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) was established after a meeting of local mining trade unions in Newport, Wales in 1888. The federation was formed to represent and co-ordinate the affairs of local and regional miners' unions in Engla ...

to provide a subsidy of £23 million (equivalent to £ million in ) to the mining industry to maintain miners' wages and secure industrial harmony.

Appreciating that this might only temporarily stave off a major industrial dispute, the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, appointed Anderson to the chairmanship of an inter-departmental committee to prepare for one. Each department was allocated a specific role: the Board of Trade stockpiled food and coal, the Ministry of Transport

A ministry of transport or transportation is a ministry responsible for transportation within a country. It usually is administered by the ''minister for transport''. The term is also sometimes applied to the departments or other government ag ...

arranged for distribution, and the Home Office was responsible for keeping law and order. When the UK General Strike of 1926

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British governme ...

commenced on 4 May 1926, Anderson had been preparing for the eventuality for nine months. He was particularly determined to remain even-handed and avoid the appearance of favouring one side over the other. When Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

suggested sending the Army to the London docks to protect the supplies of paper needed to print the ''British Gazette'', Anderson cut him off with: "I would beg the chancellor of the exchequer to stop talking nonsense".

Governor of Bengal

Being the head of a department was the pinnacle of a Civil Service career, and by November 1931, Anderson had been the permanent under-secretary for nine years, but at age 49 he was still eleven years away from retirement. At this point an unexpected offer appeared. The Secretary of State for India, Sir Samuel Hoare, 1st Viscount Templewood, Samuel Hoare, and the Under-Secretary of State for India, Sir Findlater Stewart, were searching for a successor to the Governor of Bengal, Sir Stanley Jackson. The province was a troubled one, and they thought of Anderson, based on his service in Ireland and during the General Strike of 1926. Jackson narrowly escaped an assassin's bullet at the University of Calcutta on 6 February 1932. On 3 March, Anderson had lunch at Buckingham Palace with King George V, who made him an additional Knight Grand Commander of the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire (GCIE). Anderson sailed from England on the on 10 March 1932, accompanied by William Paterson, Mary Anderson and Nellie Mackenzie; his son Alastair was studying medicine at Pembroke College, Cambridge. Anderson arrived in Calcutta on 29 March, and was greeted with a 17-gun salute. The position came with an annual salary of approximately , a sumptuary allowance of and a grant of to cover his staff's wages. In addition to his personal staff he had 120 servants, a seventy-man mounted bodyguard, and a brass band. There were cars, two special trains, a yacht and a house boat.

There were government houses in Raj Bhavan, Kolkata, Calcutta, Raj Bhavan, Darjeeling, Darjeeling, Barrackpore and Bangabhaban, Dacca. The primary residence of the governor was in Calcutta, but when the weather became hot in April the governor and his staff would move to Darjeeling, returning when the Monsoon of South Asia, monsoon broke in June. Each year they would spend a month in Dacca in fulfilment of a promise made when Partition of Bengal (1905), Bengal was reunited in 1911. They would then go back to Darjeeling, remaining until it became cold, and then return to Calcutta. Anderson visited all twenty-six districts of Bengal, usually travelling by train, but sometimes by river on a towed barge he named the ''Mary Anderson (yacht), Mary Anderson'' after his daughter. He regularly attended church services at St Andrew's Church in Calcutta and St Columba's Church in Darjeeling. On 26 March 1933, he was ordained as an Elder of the Church of Scotland at St Andrew's.

Anderson recognised that the root of Bengal's problems was financial. The chief source of revenue was collected under the terms of the Permanent Settlement of Bengal that had been concluded by Lord Cornwallis in 1793 and taxed landowners known as zamindars based on the value of their land. Other forms of taxation, such as income tax and export duties were collected by the central government and little was returned to Bengal. As a result, public infrastructure, such as police, education and health, had been run down. The export duty on the jute trade was particularly unfair, as it had been imposed during the Great War when the trade was booming, but by 1932 the trade was in decline due to competition from paper and cotton bags. The global Great Depression caused the prices of agricultural commodities to fall. Anderson negotiated a revision of the financial arrangements with Sir Otto Niemeyer, under which the provinces retained half of their income tax and jute duty receipts and provincial debts to the central government were cancelled.

The other major task that Anderson confronted was dealing with terrorism. Collective fines were imposed on areas that sheltered or supported terrorists, and the funds used to increase the police presence. He was aware that he was a target, but as the King's representative he continued to make public appearances, travelling in a Rolls-Royce Limited, Rolls-Royce or an open horse-drawn carriage. On 4 May 1934 a would-be assassin fired at Anderson but the bullet passed between him and Nellie Mackenzie, and the man was wrestled to the ground by Charles William Tandy-Green. A second man fired but also missed Anderson, though wounded the ankle of a teenager sitting behind the governor, and was tackled by Bhupendra Narayan Singh. Tandy-Green and Singh were awarded the Empire Gallantry Medal, which they exchanged for the George Cross in 1940. Five other members of the gang attempted to escape but were captured. The would-be assassins were sentenced to hang, but Anderson commuted the sentences of two of them. By 1935 he was described as the world's most-shot-at-man, having survived three assassination attempts. Anderson tackled the problem of what to do with détenus, individuals who had been detained without trial on suspicion of terrorism by giving them training for jobs in agriculture and manufacturing.

Anderson carried out a series of economic and social programs. He waged a campaign against water hyacinth, an invasive plant species that threatened to clog Bengal's waterways. He regulated jute production through a system of voluntarily restrictions. He established a panel that examined the problem of rural debt, and sponsored legislation to reduce the debts of farmers. He introduced compulsory primary school education. The Government of India Act 1935 was scheduled to become operative on 1 April 1937, soon after his five-year term of office was due to expire, but at the request of the Secretary of State for India, the Lawrence Dundas, 2nd Marquess of Zetland, Marquess of Zetland, and the List of governors-general of India, viceroy, the Victor Hope, 2nd Marquess of Linlithgow, Marquess of Linlithgow, Anderson agreed to a six-month extension in order to oversee the transition to self-government, but declined a request from Zetland for his term to be further extended. For his services in India, Anderson was appointed a Knight Grand Commander of the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India (GCSI) on 15 December 1937, and was made a Privy Counsellor in the 1938 New Year Honours.

Anderson sailed from England on the on 10 March 1932, accompanied by William Paterson, Mary Anderson and Nellie Mackenzie; his son Alastair was studying medicine at Pembroke College, Cambridge. Anderson arrived in Calcutta on 29 March, and was greeted with a 17-gun salute. The position came with an annual salary of approximately , a sumptuary allowance of and a grant of to cover his staff's wages. In addition to his personal staff he had 120 servants, a seventy-man mounted bodyguard, and a brass band. There were cars, two special trains, a yacht and a house boat.

There were government houses in Raj Bhavan, Kolkata, Calcutta, Raj Bhavan, Darjeeling, Darjeeling, Barrackpore and Bangabhaban, Dacca. The primary residence of the governor was in Calcutta, but when the weather became hot in April the governor and his staff would move to Darjeeling, returning when the Monsoon of South Asia, monsoon broke in June. Each year they would spend a month in Dacca in fulfilment of a promise made when Partition of Bengal (1905), Bengal was reunited in 1911. They would then go back to Darjeeling, remaining until it became cold, and then return to Calcutta. Anderson visited all twenty-six districts of Bengal, usually travelling by train, but sometimes by river on a towed barge he named the ''Mary Anderson (yacht), Mary Anderson'' after his daughter. He regularly attended church services at St Andrew's Church in Calcutta and St Columba's Church in Darjeeling. On 26 March 1933, he was ordained as an Elder of the Church of Scotland at St Andrew's.

Anderson recognised that the root of Bengal's problems was financial. The chief source of revenue was collected under the terms of the Permanent Settlement of Bengal that had been concluded by Lord Cornwallis in 1793 and taxed landowners known as zamindars based on the value of their land. Other forms of taxation, such as income tax and export duties were collected by the central government and little was returned to Bengal. As a result, public infrastructure, such as police, education and health, had been run down. The export duty on the jute trade was particularly unfair, as it had been imposed during the Great War when the trade was booming, but by 1932 the trade was in decline due to competition from paper and cotton bags. The global Great Depression caused the prices of agricultural commodities to fall. Anderson negotiated a revision of the financial arrangements with Sir Otto Niemeyer, under which the provinces retained half of their income tax and jute duty receipts and provincial debts to the central government were cancelled.

The other major task that Anderson confronted was dealing with terrorism. Collective fines were imposed on areas that sheltered or supported terrorists, and the funds used to increase the police presence. He was aware that he was a target, but as the King's representative he continued to make public appearances, travelling in a Rolls-Royce Limited, Rolls-Royce or an open horse-drawn carriage. On 4 May 1934 a would-be assassin fired at Anderson but the bullet passed between him and Nellie Mackenzie, and the man was wrestled to the ground by Charles William Tandy-Green. A second man fired but also missed Anderson, though wounded the ankle of a teenager sitting behind the governor, and was tackled by Bhupendra Narayan Singh. Tandy-Green and Singh were awarded the Empire Gallantry Medal, which they exchanged for the George Cross in 1940. Five other members of the gang attempted to escape but were captured. The would-be assassins were sentenced to hang, but Anderson commuted the sentences of two of them. By 1935 he was described as the world's most-shot-at-man, having survived three assassination attempts. Anderson tackled the problem of what to do with détenus, individuals who had been detained without trial on suspicion of terrorism by giving them training for jobs in agriculture and manufacturing.

Anderson carried out a series of economic and social programs. He waged a campaign against water hyacinth, an invasive plant species that threatened to clog Bengal's waterways. He regulated jute production through a system of voluntarily restrictions. He established a panel that examined the problem of rural debt, and sponsored legislation to reduce the debts of farmers. He introduced compulsory primary school education. The Government of India Act 1935 was scheduled to become operative on 1 April 1937, soon after his five-year term of office was due to expire, but at the request of the Secretary of State for India, the Lawrence Dundas, 2nd Marquess of Zetland, Marquess of Zetland, and the List of governors-general of India, viceroy, the Victor Hope, 2nd Marquess of Linlithgow, Marquess of Linlithgow, Anderson agreed to a six-month extension in order to oversee the transition to self-government, but declined a request from Zetland for his term to be further extended. For his services in India, Anderson was appointed a Knight Grand Commander of the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India (GCSI) on 15 December 1937, and was made a Privy Counsellor in the 1938 New Year Honours.

Political career

Pre-war

After Ireland and Bengal, the British government could find no more dangerous assignment than Mandatory Palestine, Palestine, and on 24 October 1937, the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, offered Anderson the position of High Commissioner for Palestine, but he declined. Another opportunity soon presented itself. The sudden death of Ramsay MacDonald on 9 November 1937 created a casual vacancy in his Scottish Universities seat in the House of Commons, and the Unionist Party (Scotland), Unionist Party now needed to find another candidate. Sir John Graham Kerr, another member for the Scottish Universities, discussed this with Sir Kenneth Pickthorn, one of the members for Cambridge University (UK Parliament constituency), Cambridge University, who suggested that Anderson might make a worthy candidate. Kerr contacted Katie Anderson, who informed him that Anderson was still en route for the UK on the liner SS ''Comorin''. Anderson arrived back in London on 11 December 1937. He spoke to Kerr, and agreed to stand for election as a National Government (United Kingdom), National Government candidate without a party label. His candidacy was announced on 4 January 1938. Voting was by postal voting, postal ballot, which meant that Anderson did not have to campaign but only needed to provide a statement of his political philosophy. In this he affirmed his support for the National Government and gave a qualified support for Scottish nationalism. The results were announced on 28 February; Anderson received more votes than any other candidate, and was declared the winner. He took his seat on 2 March and, after a holiday in Switzerland with Mary Anderson and Nellie Mackenzie, made his maiden speech in the House of Commons on 1 June. The occasion was a debate over the provision of funding authorised under the Air Raid Precaution Act of 1937, a subject that he had previously been involved with and would come to be identified. Mary Anderson and Nellie Mackenzie had preceded Anderson to England and rented a house at 11 Chepstow Villas in Notting Hill for nine guinea (coin), guineas a week (). Although this was a bargain, Anderson feared that his income would not be sufficient to keep up the rental payments. Before leaving Calcutta he accepted a directorship from the Midland Bank, and after his return to England he joined the boards of Vickers, Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) and the Employers Liability Assurance Corporation. The directors' fees gave him an annual income of around . He was approached by members of the board of Imperial Airways who were seeking a new full-time chairman with an offer of more than twice that amount. However, Chamberlain stipulated that if he accepted then he would have to resign his other directorships and his seat in the House of Commons at the next general election, which was due in 1940. Anderson therefore declined the appointment. He would sometimes go horse riding in Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park with Mary Anderson, but sought a more rural environment. He disposed of the house in Chepstow Villas in October and bought a property near Merstham in December. During the week he lived with William Paterson and his wife.

In May 1938, Hoare, who was now the

Mary Anderson and Nellie Mackenzie had preceded Anderson to England and rented a house at 11 Chepstow Villas in Notting Hill for nine guinea (coin), guineas a week (). Although this was a bargain, Anderson feared that his income would not be sufficient to keep up the rental payments. Before leaving Calcutta he accepted a directorship from the Midland Bank, and after his return to England he joined the boards of Vickers, Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) and the Employers Liability Assurance Corporation. The directors' fees gave him an annual income of around . He was approached by members of the board of Imperial Airways who were seeking a new full-time chairman with an offer of more than twice that amount. However, Chamberlain stipulated that if he accepted then he would have to resign his other directorships and his seat in the House of Commons at the next general election, which was due in 1940. Anderson therefore declined the appointment. He would sometimes go horse riding in Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park with Mary Anderson, but sought a more rural environment. He disposed of the house in Chepstow Villas in October and bought a property near Merstham in December. During the week he lived with William Paterson and his wife.

In May 1938, Hoare, who was now the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

, appointed Anderson to chair a new Committee on Evacuation to examine the problems involved in evacuating people and industries from densely populated industrial areas in the event of a war. Over the next eight weeks the committee held twenty-five meetings and examined fifty-seven witnesses. The committee submitted its report in July. The scheme outlined in the report would be implemented when the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

broke out in September 1939. Meanwhile, in October 1938 Anderson entered Chamberlain's ministry as Lord Privy Seal. In that capacity, he was put in charge of civil defence. He initiated the development of a kind of air-raid shelter, and engaged William Paterson to design it. Paterson worked with his co-director, Oscar Carl (Karl) Kerrison, and together they devised a small sheet metal cylinder made of prefabricated

Prefabrication is the practice of assembling components of a structure in a factory or other manufacturing site, and transporting complete assemblies or sub-assemblies to the construction site where the structure is to be located. The term ...

pieces which could be assembled in a garden and partially buried to protect against bomb blast. It became known as the Air-raid shelter#Anderson shelter, Anderson shelter. When war broke out in September 1939, some 1.5 million Anderson shelters had been delivered.

War time

Under a pre-arranged plan, on the outbreak of the Second World War on 3 September 1939, Anderson exchanged places with Hoare and became Home Secretary and Minister of Home Security. In the wake of the Norwegian campaign Chamberlain resigned on 10 May 1940 and Winston Churchill became the Prime Minister but Anderson stayed on as Home Secretary and Minister of Home Security in the new Churchill war ministry, coalition government. Measures taken in Ireland and Bengal were now applied to the UK. Anderson created special tribunals to assess the reliability of Enemy alien, aliens resident in the UK. He informed the House of Commons that of the 73,353 aliens in the UK, no less than 55,457 were refugees from Nazi oppression; only 569 were interned. However, as the tide of war turned against the UK, the pressure to act against aliens grew, and on 16 May some 3,000 men whose reliability was classed as uncertain were interned, and in June 3,500 women and children were sent to the Isle of Man. Anderson then decided to intern refugees previously considered reliable, and some 8,000 were transported to Canada and Australia. One transport, the was sunk by a U-boat. Members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, the Peace Pledge Union and the British Union of Fascists were rounded up. In June 1945, there were still 1,847 persons held in detention under Defence Regulation 18B. Once the Blitz began, the contingencies that Anderson had been preparing for were realised, and Anderson came under heavy attack in the press and the House of Commons over the issue of not providing deep shelters. On 8 October 1940, in a reshuffle precipitated by Chamberlain's resignation due to ill-health, Anderson was replaced by

Once the Blitz began, the contingencies that Anderson had been preparing for were realised, and Anderson came under heavy attack in the press and the House of Commons over the issue of not providing deep shelters. On 8 October 1940, in a reshuffle precipitated by Chamberlain's resignation due to ill-health, Anderson was replaced by Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the UK Cabinet as member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Minis ...

, a less able administrator, but a more adept politician. Anderson became Lord President of the Council and full member of the War Cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senio ...

. The Lord President served as chairman of the Lord President's Committee. This committee acted as a central clearing house which dealt with the country's economic problems. This was vital to the smooth running of the British war economy and consequently the entire British war effort. Anderson had no staff of his own, but used that of the War Cabinet, particularly its Economic Section. As chairman of the Manpower Committee, he controlled the allocation of the most critical of wartime resources: people.

In 1941, he began courting Ava Anderson, Viscountess Waverley, Ava Wigram, the daughter of the historian John Edward Courtenay Bodley, and the widow of Ralph Wigram, a senior civil servant who served in the British Embassy in Paris during the 1930s and died in 1936. Their only child, Charles, was born severely disabled in 1929. Anderson arranged with King George VI for himself and Ava to be married in the Chapel Royal at St James's Palace. The ceremony was officiated by Edward Woods (bishop), Edward Woods, the Bishop of Lichfield; Alastair Anderson was the best man; and while John's father felt that he was too old to travel, Mary and Katie Anderson were there, as was William Paterson. The newlyweds spent their honeymoon at Polesden Lacey. They now owned three houses between them, so they sold them and bought the Mill House at Isfield in September 1942.

As Lord President of the Council, Anderson was the minister responsible for several scientific organisations, including the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (United Kingdom), Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, the Agricultural Research Council and the Medical Research Council (United Kingdom), Medical Research Council. In August 1941, Anderson became the cabinet minister responsible for the oversight of the British project to build an atomic bomb, known as the Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the ...

project. A special section of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research was created to manage it, under the leadership of Wallace Akers. Anderson negotiated cooperation with the Americans at the Second Washington Conference in June 1942, but after the establishment of the Manhattan Project later that year cooperation broke down. In response to a request from the Americans, Anderson flew to Washington, D.C., on 1 August 1943 for negotiations with James B. Conant and Vannevar Bush. He had to reassure the Americans that Britain's interest was in winning the war, and not in profits to be made from nuclear energy afterwards. He then moved on to Canada for negotiations with officials there. The culmination of his efforts was the signing of the Quebec Agreement on 19 August 1943, which paved the way for the British contribution to the Manhattan Project. In 1945 Anderson was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society under Statute 12, which covered those who "rendered conspicuous service to the cause of science, and whose election would be of signal benefit to the Society".

Following the unexpected death on 21 September 1943 of Sir Kingsley Wood, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Anderson was appointed to that office on 24 September. He retained responsibility for Tube Alloys, and his chairmanship of the Manpower Committee. As Chancellor, he introduced the pay-as-you-earn tax system that had been devised by Paul Chambers (industrialist), Paul Chambers; the enabling legislation was to have been introduced by Wood on the day that he died. The system was very successful, and was gradually extended to all employers except the armed forces. In a written Commons answer of 12 June 1945, he announced the creation of the Arts Council of Great Britain, a successor body to the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA).

In January 1945, Churchill wrote to King George VI to advise that should he and his second-in-command (and heir apparent) Anthony Eden die during the war, John Anderson should become Prime Minister: "it is the Prime Minister's duty to advise Your Majesty to send for Sir John Anderson in the event of the Prime Minister and the Foreign Secretary being killed." Although not a member of a political party, Churchill thought Anderson had the abilities to lead the National Government, and that an independent figure was essential to the maintenance of the coalition. During the Yalta Conference Anderson opposed the Soviet Union's demands for World War II reparations, war reparations from Germany because of the role World War I reparations played in the Great Depression and the collapse of the Weimar Republic.

After German Instrument of Surrender, Germany surrendered on 7 May 1945, Churchill unsuccessfully attempted to broker a continuation of the wartime coalition government until after the end of the war with Japan, which was thought at the time to be over a year away. On 23 May Churchill then submitted his resignation to the King, who called an election for 5 July. Anderson retained his role of Chancellor of the Exchequer in the caretaker government, and remained in the post until the Labour Party (UK), Labour victory in the 1945 United Kingdom general election, general election in July 1945. He was returned in his Scottish University electorate, along with Sir John Graham Kerr and Sir John Boyd Orr.

On 29 June 1945, Churchill had initialled a minute from Anderson, seeking "authority to instruct our representatives on the Combined Policy Committee to give their concurrence for the use of the atomic bomb against Japan." After the bombing of Hiroshima, Anderson gave a broadcast on the BBC Home Service on 7 August 1945 in which he described the challenges and potentialities of nuclear energy in layman's terms.

Post-war

The new Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, appointed Anderson the chairman of the new Advisory Committee on Atomic Energy on 14 August 1945. On 9 November, he accompanied Attlee to Washington, D.C., for talks on atomic energy with President Harry S. Truman and Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King. Talks took place on the presidential yacht . The President and the two Prime Ministers were joined by Anderson; the President's White House Chief of Staff, Chief of Staff, Fleet admiral (United States), Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy; the United States Secretary of State, James F. Byrnes; Lord Halifax; and Lester B. Pearson. They agreed to continue the Combined Policy Committee and the Combined Development Trust, and agreed to collaborate, but the Americans soon made it clear that this extended only to basic research. The 1946 McMahon Act ended all cooperation on nuclear weapons. On 7 January 1948, with the post-war High Explosive Research, British atomic weapons project in full swing and being managed by other committees, Anderson tendered his resignation from the Advisory Committee. Anderson left the Commons on 23 February 1950 at the 1950 United Kingdom general election, general election, when the university constituencies were abolished. He declined offers from the Ulster Unionist Party to contest a safe seat in Northern Ireland, and from Churchill to contest the blue-ribbon Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party seat of East Surrey (UK Parliament constituency), East Surrey. At the Boat Race 1951, Attlee tried to get Ava to persuade Anderson to accept a peerages in the United Kingdom, peerage, but Anderson still hoped that university constituencies would be restored and he could contest his old seat. He rejected an offer to become the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster in Churchill's peacetime administration when it was formed in October 1951, and was created Viscount Waverley, ofWestdean

Cuckmere Valley is a civil parish in the Wealden District of East Sussex, England. As its name suggests, the parish consists of a number of small settlements in the lower reaches of the River Cuckmere.

The settlements

There are three villages ...

in the Sussex, County of Sussex, on 29 January 1952.

Meanwhile, Anderson had become Chairman of the Port of London Authority in 1946 and Chairman of the Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Ope ...

in March the same year. He also became a director of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Hudson's Bay Company. He resumed his membership of the boards of ICI, Vickers and the Employers' Life Assurance Corporation that he had given up when he became a minister, but not the Midland Bank, which in those days would have been considered improper for a former Chancellor of the Exchequer. The Port of London Authority chairman had often been part time and unpaid in the past, but now that a full-time role was called for Anderson insisted on being paid, and was given an annual salary of . The job was an immense one, as the port had been badly damaged by bombing during the war, and a major reconstruction effort was called for. Ava used the Port Authority's yacht, the ''St Katharine'', to hold party cruises on the river around the London Docks for special guests, and invitations were highly sought after.

In addition to British honours and awards, Anderson received many awards from other countries. These included being made a Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour by France; a Commander of the Order of the Crown of Italy; the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Olav of Norway, the Order of the Polar Star, Order of the North Star of Sweden, of the Military Order of Christ of Portugal, and the Order of the Dannebrog of Denmark. He was awarded an honorary D.C.L. by Oxford University, and honorary D.Sc. by McGill University, and honorary LL.D. by the University of Edinburgh, University of Aberdeen, University of Cambridge, University of St Andrews, University of Liverpool, University of Leeds, University of Sheffield and the University of London, and was an Honorary Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. It was intended that he should be awarded the Order of Merit in the 1958 New Year Honours but an operation on 17 August 1957 revealed that he had pancreatic cancer, and it was feared he would not live long enough to receive it, so Queen Elizabeth II made an immediate award, which was conferred at his hospital bed. He died on 4 January 1958 in St Thomas' Hospital, and was buried in the churchyard in Westdean.

See also

*''Liversidge v. Anderson''Notes

References

* * * * * * * * *External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Waverley, John Anderson, 1st Viscount 1882 births 1958 deaths Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Chancellors of the Exchequer of the United Kingdom, Anderson, John Civil servants in the Colonial Office, Anderson, John Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12), Anderson, John British governors of Bengal, Anderson, John Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Leipzig University alumni Lord Presidents of the Council, Anderson, John Lords Privy Seal, Anderson, John Members of the Order of Merit Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for the Combined Scottish Universities, Anderson, John Members of the Privy Council of Ireland Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Ministers in the Churchill caretaker government, 1945 Ministers in the Churchill wartime government, 1940–1945 People from Dalkeith Permanent Under-Secretaries of State for the Home Department, Anderson, John Secretaries of State for the Home Department, Anderson, John UK MPs 1935–1945, Anderson, John Under-Secretaries for Ireland, Anderson, John Ministers in the Chamberlain wartime government, 1939–1940 Ministers in the Chamberlain peacetime government, 1937–1939 Viscounts created by George VI Viscounts Waverley