Scots language literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Scots-language literature is literature, including poetry, prose and drama, written in the Scots language in its many forms and derivatives. Middle Scots became the dominant language of Scotland in the late Middle Ages. The first surviving major text in Scots literature is

Scots-language literature is literature, including poetry, prose and drama, written in the Scots language in its many forms and derivatives. Middle Scots became the dominant language of Scotland in the late Middle Ages. The first surviving major text in Scots literature is

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is

As a patron of poets and authors

As a patron of poets and authors

Literary Style

", retrieved 24 September 2010. Burns was skilled in writing not only in the Scots language but also in the Scottish English dialect of the English language. Some of his works, such as "Love and Liberty" (also known as "The Jolly Beggars"), are written in both Scots and English for various effects.Robert Burns:

hae meat

, retrieved 24 September 2010. His themes included republicanism,

to the Kibble

" Retrieved 24 September 2010.

Scots-language literature is literature, including poetry, prose and drama, written in the Scots language in its many forms and derivatives. Middle Scots became the dominant language of Scotland in the late Middle Ages. The first surviving major text in Scots literature is

Scots-language literature is literature, including poetry, prose and drama, written in the Scots language in its many forms and derivatives. Middle Scots became the dominant language of Scotland in the late Middle Ages. The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour John Barbour may refer to:

* John Barbour (poet) (1316–1395), Scottish poet

* John Barbour (MP for New Shoreham), MP for New Shoreham 1368-1382

* John Barbour (footballer) (1890–1916), Scottish footballer

* John S. Barbour (1790–1855), U. ...

's '' Brus'' (1375). Some ballads may date back to the thirteenth century, but were not recorded until the eighteenth century. In the early fifteenth century Scots historical works included Andrew of Wyntoun

Andrew Wyntoun, known as Andrew of Wyntoun (), was a Scottish poet, a canon and prior of Loch Leven on St Serf's Inch and, later, a canon of St. Andrews.

Andrew Wyntoun is most famous for his completion of an eight-syllabled metre entitled, '' ...

's verse ''Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland'' and Blind Harry's '' The Wallace''. Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court, which included James I, who wrote the extended poem '' The Kingis Quair''. Writers such as William Dunbar, Robert Henryson, Walter Kennedy and Gavin Douglas have been seen as creating a golden age in Scottish poetry. In the late fifteenth century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. The first complete surviving work is John Ireland's ''The Meroure of Wyssdome'' (1490). There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s. The landmark work in the reign of James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauchi ...

was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil's '' Aeneid''.

James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV and Margaret Tudor, and duri ...

supported William Stewart and John Bellenden, who translated the Latin ''History of Scotland'' compiled in 1527 by Hector Boece, into verse and prose. David Lyndsay wrote elegiac narratives, romances and satires. From the 1550s cultural pursuits were limited by the lack of a royal court and the Kirk heavily discouraged poetry that was not devotional. Nevertheless, poets from this period included Richard Maitland

Sir Richard Maitland of Lethington and Thirlstane (1496 – 1 August 1586) was a Senator of the College of Justice, an Ordinary Lord of Session from 1561 until 1584, and notable Scottish poet. He was served heir to his father, Sir William Maitl ...

of Lethington, John Rolland John Rolland ( fl. 1560), Scottish poet, appears to have been a priest of the diocese of Glasgow, and to have been known in Dalkeith in 1555.

He is the author of two poems, the ''Court of Venus'' and a translation of the ''Seven Wise Masters''. Th ...

and Alexander Hume

Alexander Hume (1558 – 4 December 1609) was a Scottish poet who served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in the early 17th century.

Life

He was born in 1558 the son of Patrick Hume (d.1599).

The brother of Patr ...

. Alexander Scott's use of short verse designed to be sung to music, opened the way for the Castilan poets of James VI's adult reign. who included William Fowler, John Stewart of Baldynneis

John Stewart of Baldynneis (c. 1545–c. 1605) was a writer and courtier at the Scottish Court. he was one of the Castalian Band grouped around James VI.

He was the son of Elizabeth Beaton, a former mistress of James V, and John Stewart, 4th Lo ...

, and Alexander Montgomerie. Plays in Scots included Lyndsay's '' The Thrie Estaitis'', the anonymous ''The Maner of the Cyring of ane Play'' and ''Philotus''. After his accession to the English throne, James VI increasingly favoured the language of southern England and the loss of the court as a centre of patronage in 1603 was a major blow to Scottish literature. The poets who followed the king to London began to anglicise

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influenc ...

their written language and only significant court poet to continue to work in Scotland after the king's departure was William Drummond of Hawthornden.

After the Union in 1707 the use of Scots was discouraged. Allan Ramsay Allan Ramsay may refer to:

*Allan Ramsay (poet) or Allan Ramsay the Elder (1686–1758), Scottish poet

*Allan Ramsay (artist) or Allan Ramsay the Younger (1713–1784), Scottish portrait painter

*Allan Ramsay (diplomat) (1937–2022), British diplom ...

(1686–1758) is often described as leading a "vernacular revival" and he laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature. He was part of a community of poets working in Scots and English that included William Hamilton of Gilbertfield

William Hamilton (1665? – 24 May 1751) was a Scottish poet. He wrote comic, mock-tragic poetry such as "''The Last Dying Words of Bonny Heck''" - a once-champion hare coursing greyhound in the East Neuk of Fife who was about to be hanged, ...

, Robert Crawford, Alexander Ross, William Hamilton of Bangour, Alison Rutherford Cockburn and James Thomson. Also important was Robert Fergusson. Robert Burns is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, working in both Scots and English. His "Auld Lang Syne

"Auld Lang Syne" (: note "s" rather than "z") is a popular song, particularly in the English-speaking world. Traditionally, it is sung to bid farewell to the old year at the stroke of midnight on New Year's Eve. By extension, it is also often ...

" is often sung at Hogmanay

Hogmanay ( , ) is the Scots word for the last day of the old year and is synonymous with the celebration of the New Year in the Scottish manner. It is normally followed by further celebration on the morning of New Year's Day (1 January) or i ...

, and "Scots Wha Hae

"Scots Wha Hae" (English: ''Scots Who Have''; gd, Brosnachadh Bhruis) is a patriotic song of Scotland written using both words of the Scots language and English, which served for centuries as an unofficial national anthem of the country, but h ...

" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem. Scottish poetry is often seen as entering a period of decline in the nineteenth century, with Scots-language poetry criticised for its use of parochial dialect. Conservative and anti-radical Burns club

Burns Clubs exist throughout the world to encourage and cherish the memory of Robert Burns, to foster a love of his writings and generally to encourage an interest in the Scots Language and Literature.Whistle Binkie

''Whistle-Binkie, or, The piper of the party: Being a collection of songs for the social circle'' was a Scottish poetry and song anthology first appearing in 1832. There were later volumes under the same title, at least four more anthologies, and ...

anthologies, leading into the sentimental parochialism of the Kailyard school

The Kailyard school (1880–1914) is a proposed literary movement of Scottish fiction dating from the last decades of the 19th century.

Origin and etymology

It was first given the name in an article published April 1895 in the ''New Review'' by ...

. Poets from the lower social orders who used Scots included the weaver-poet William Thom. Walter Scott, the leading literary figure of the early nineteenth century, largely wrote in English, and Scots was confined to dialogue or interpolated narrative, in a model that would be followed by other novelists such as John Galt and Robert Louis Stevenson. James Hogg provided a Scots counterpart to the work of Scott.G. Carruthers, ''Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), , p. 58. However, popular Scottish newspapers regularly included articles and commentary in the vernacular and there was an interest in translations into Scots from other Germanic languages, such as Danish, Swedish and German, including those by Robert Jamieson and Robert Williams Buchanan

Robert Williams Buchanan (18 August 1841 – 10 June 1901) was a Scottish poet, novelist and dramatist.

Early life and education

He was the son of Robert Buchanan (1813–1866), Owenite lecturer and journalist, and was born at Caverswall, S ...

.

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by modernism and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure in the movement was Hugh MacDiarmid

Christopher Murray Grieve (11 August 1892 – 9 September 1978), best known by his pen name Hugh MacDiarmid (), was a Scottish poet, journalist, essayist and political figure. He is considered one of the principal forces behind the Scottish Rena ...

who attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature, developing a form of Synthetic Scots

Lallans (; a variant of the Modern Scots word ''lawlands'' meaning the lowlands of Scotland), is a term that was traditionally used to refer to the Scots language as a whole. However, more recent interpretations assume it refers to the dialects ...

that combined different regional dialects and archaic terms. Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poets Edwin Muir and William Soutar

William Soutar (28 April 1898 – 15 October 1943) was a Scottish poet and diarist who wrote in English and in Braid Scots. He is known best for his epigrams.

Life and works

William Soutar was born on 28 April 1898 on South Inch Terrace in P ...

. Some writers that emerged after the Second World War followed MacDiarmid by writing in Scots, including Robert Garioch

Robert Garioch Sutherland (9 May 1909 – 26 April 1981) was a Scottish poet and translator. His poetry was written almost exclusively in the Scots language, he was a key member in the literary revival of the language in the mid-20th century ...

, Sydney Goodsir Smith and Edwin Morgan, who became known for translations of works from a wide range of European languages. Alexander Gray is chiefly remembered for this translations into Scots from the German and Danish ballad traditions into Scots. Writers who reflected urban contemporary Scots included Douglas Dunn, Tom Leonard and Liz Lochhead. The Scottish Renaissance increasingly concentrated on the novel. George Blake pioneered the exploration of the experiences of the working class. Lewis Grassic Gibbon produced one of the most important realisations of the ideas of the Scottish Renaissance in his trilogy '' A Scots Quair''. Other writers that investigated the working class included James Barke and J. F. Hendry

James Findlay Hendry (12 September 1912 – 17 December 1986) was a Scottish poet known also as an editor and writer. He was born in Glasgow, and read Modern Languages at the University of Glasgow. During World War II he served in the Royal Arti ...

. From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers that included Alasdair Gray and James Kelman were among the first novelists to fully utilise a working class Scots voice as the main narrator. Irvine Welsh and Alan Warner

Alan Warner (born 1964) is a Scottish novelist who grew up in Connel, near Oban. His notable novels include '' Morvern Callar'' and ''The Sopranos'' – the latter being the inspiration for the play '' Our Ladies of Perpetual Succour'' and its ...

both made use of vernacular language including expletives and words from the Scots language.

Background

In the late Middle Ages, Middle Scots, often simply called English, became the dominant language of the country. It was derived largely fromOld English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

, with the addition of elements from Gaelic and French. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late fourteenth century onwards.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 60–7. It began to be adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French. By the fifteenth century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I (1406–37) onwards. As a result, Gaelic, once dominant north of the Tay, began a steady decline.

Development

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour John Barbour may refer to:

* John Barbour (poet) (1316–1395), Scottish poet

* John Barbour (MP for New Shoreham), MP for New Shoreham 1368-1382

* John Barbour (footballer) (1890–1916), Scottish footballer

* John S. Barbour (1790–1855), U. ...

's '' Brus'' (1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of Robert I Robert I may refer to:

*Robert I, Duke of Neustria (697–748)

*Robert I of France (866–923), King of France, 922–923, rebelled against Charles the Simple

*Rollo, Duke of Normandy (c. 846 – c. 930; reigned 911–927)

* Robert I Archbishop of ...

's actions before the English invasion until the end of the first war of independence. The work was extremely popular among the Scots-speaking aristocracy and Barbour is referred to as the father of Scots poetry, holding a similar place to his contemporary Chaucer in England. Some Scots ballads may date back to the late medieval era and deal with events and people that can be traced back as far as the thirteenth century, including "Sir Patrick Spens

"Sir Patrick Spens" is one of the most popular of the Child Ballads (No. 58) (Roud 41), and is of Scottish origin. It is a maritime ballad about a disaster at sea.

Background

''Sir Patrick Spens'' remains one of the most anthologized of Briti ...

" and " Thomas the Rhymer", but which are not known to have existed until they were collected and recorded in the eighteenth century. They were probably composed and transmitted orally and only began to be written down and printed, often as broadsides and as part of chapbooks, later being recorded and noted in books by collectors including Robert Burns and Walter Scott. In the early fifteenth century Scots historical works included Andrew of Wyntoun

Andrew Wyntoun, known as Andrew of Wyntoun (), was a Scottish poet, a canon and prior of Loch Leven on St Serf's Inch and, later, a canon of St. Andrews.

Andrew Wyntoun is most famous for his completion of an eight-syllabled metre entitled, '' ...

's verse ''Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland'' and Blind Harry's '' The Wallace'', which blended historical romance with the verse chronicle. They were probably influenced by Scots versions of popular French romances that were also produced in the period, including '' The Buik of Alexander'', '' Launcelot o the Laik'', ''The Porteous of Noblenes'' by Gilbert Hay.

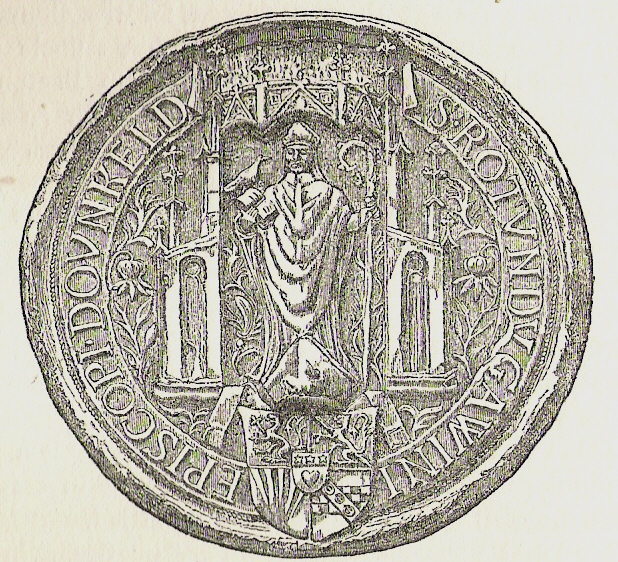

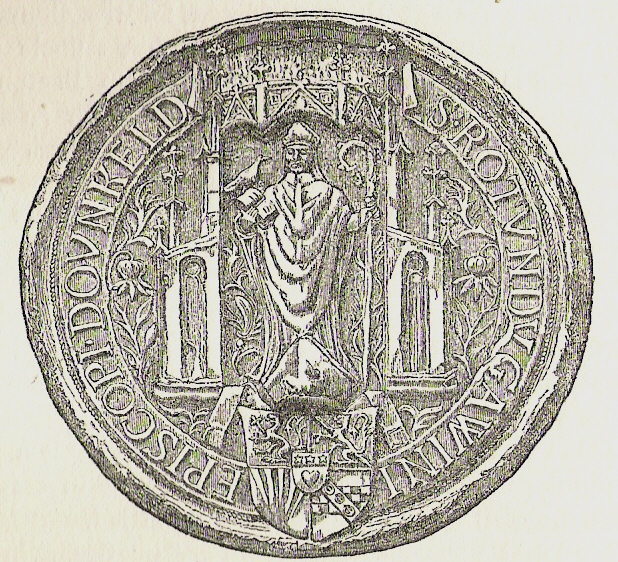

Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court, which included James I, who wrote the extended poem '' The Kingis Quair''. Many of the makars had university education and so were also connected with the Kirk. However, William Dunbar's (1460–1513) '' Lament for the Makaris'' (c. 1505) provides evidence of a wider tradition of secular writing outside of Court and Kirk now largely lost. Writers such as Dunbar, Robert Henryson, Walter Kennedy and Gavin Douglas have been seen as creating a golden age in Scottish poetry. Major works include Richard Holland

Richard Holland or Richard de Holande (died in or after 1483) was a Scottish cleric and poet, author of the ''Buke of the Howlat''.

Life

Holland was secretary or chaplain to Archibald Douglas, Earl of Moray (c. 1450) and rector of Halkirk, nea ...

's satire the ''Buke of the Howlat

''The Buke of the Howlat'', often referred to simply as ''The Howlat'', is a humorous 15th century Scots poem by Richard Holland.

Description

The poem is a comic allegory in which all the characters are birds with human attributes, with a howle ...

'' (c. 1448). Dunbar produced satires, lyrics, invectives and dream visions that established the vernacular as a flexible medium for poetry of any kind. Robert Henryson (c. 1450-c. 1505), re-worked Medieval and Classical sources, such as Chaucer and Aesop in works such as his ''Testament of Cresseid'' and ''The Morall Fabillis''. Gavin Douglas (1475–1522), who became Bishop of Dunkeld, injected Humanist concerns and classical sources into his poetry.T. van Heijnsbergen, "Culture: 9 Renaissance and Reformation: poetry to 1603", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 129–30. Much of their work survives in a single collection. The Bannatyne Manuscript was collated by George Bannatyne (1545–1608) around 1560 and contains the work of many Scots poets who would otherwise be unknown.M. Lynch, "Culture: 3 Medieval", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 117–8.

In the late fifteenth century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. Although there are earlier fragments of original Scots prose, such as the ''Auchinleck Chronicle'', the first complete surviving work is John Ireland's ''The Meroure of Wyssdome'' (1490). There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s, including ''The Book of the Law of Armys'' and the ''Order of Knychthode'' and the treatise '' Secreta Secetorum'', an Arabic work believed to be Aristotle's advice to Alexander the Great. The landmark work in the reign of James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauchi ...

was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil's '' Aeneid'', the '' Eneados'', which was the first complete translation of a major classical text in an Anglic language, finished in 1513, but overshadowed by the disaster at Flodden in the same year.

Golden age

As a patron of poets and authors

As a patron of poets and authors James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV and Margaret Tudor, and duri ...

(r. 1513–42) supported William Stewart and John Bellenden, who translated the Latin ''History of Scotland'' compiled in 1527 by Hector Boece, into verse and prose. David Lyndsay (c. 1486 – 1555), diplomat and the head of the Lyon Court, was a prolific poet. He wrote elegiac narratives, romances and satires. From the 1550s, in the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1542–67) and the minority of her son James VI (r. 1567–1625), cultural pursuits were limited by the lack of a royal court and by political turmoil. The Kirk, heavily influenced by Calvinism, also discouraged poetry that was not devotional in nature. Nevertheless, poets from this period included Richard Maitland

Sir Richard Maitland of Lethington and Thirlstane (1496 – 1 August 1586) was a Senator of the College of Justice, an Ordinary Lord of Session from 1561 until 1584, and notable Scottish poet. He was served heir to his father, Sir William Maitl ...

of Lethington (1496–1586), who produced meditative and satirical verses in the style of Dunbar; John Rolland John Rolland ( fl. 1560), Scottish poet, appears to have been a priest of the diocese of Glasgow, and to have been known in Dalkeith in 1555.

He is the author of two poems, the ''Court of Venus'' and a translation of the ''Seven Wise Masters''. Th ...

(fl. 1530–75), who wrote allegorical satires in the tradition of Douglas and courtier and minister Alexander Hume

Alexander Hume (1558 – 4 December 1609) was a Scottish poet who served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in the early 17th century.

Life

He was born in 1558 the son of Patrick Hume (d.1599).

The brother of Patr ...

(c. 1556–1609), whose corpus of work includes nature poetry and epistolary verse. Alexander Scott's (?1520–82/3) use of short verse designed to be sung to music, opened the way for the Castilan poets of James VI's adult reign.

From the mid sixteenth century, written Scots was increasingly influenced by the developing Standard English

In an English-speaking country, Standard English (SE) is the variety of English that has undergone substantial regularisation and is associated with formal schooling, language assessment, and official print publications, such as public service a ...

of Southern England due to developments in royal and political interactions with England. The English supplied books and distributing Bibles and Protestant literature in the Lowlands when they invaded in 1547. With the increasing influence and availability of books printed in England, most writing in Scotland came to be done in the English fashion. Leading figure of the Scottish Reformation John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

was accused of being hostile to Scots because he wrote in a Scots-inflected English developed while in exile at the English court.G. Carruthers, ''Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), , p. 44.

In the 1580s and 1590s James VI strongly promoted the literature of the country of his birth in Scots. His treatise, '' Some Rules and Cautions to be Observed and Eschewed in Scottish Prosody'', published in 1584 when he was aged 18, was both a poetic manual and a description of the poetic tradition in his mother tongue, to which he applied Renaissance principles. He became patron and member of a loose circle of Scottish Jacobean court poets and musicians, later called the Castalian Band, which included William Fowler (c. 1560 – 1612), John Stewart of Baldynneis

John Stewart of Baldynneis (c. 1545–c. 1605) was a writer and courtier at the Scottish Court. he was one of the Castalian Band grouped around James VI.

He was the son of Elizabeth Beaton, a former mistress of James V, and John Stewart, 4th Lo ...

(c. 1545 – c. 1605), and Alexander Montgomerie (c. 1550 – 1598). They translated key Renaissance texts and produced poems using French forms, including sonnet

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's invention, ...

s and short sonnets, for narrative, nature description, satire and meditations on love. Later poets that followed in this vein included William Alexander William or Bill Alexander may refer to:

Literature

*William Alexander (poet) (1808–1875), American poet and author

* William Alexander (journalist and author) (1826–1894), Scottish journalist and author

*William Alexander (author) (born 1976), ...

(c. 1567 – 1640), Alexander Craig (c. 1567 – 1627) and Robert Ayton (1570–1627). By the late 1590s the king's championing of his native Scottish tradition was to some extent diffused by the prospect of inheriting of the English throne.

In drama Lyndsay produced an interlude at Linlithgow Palace

The ruins of Linlithgow Palace are located in the town of Linlithgow, West Lothian, Scotland, west of Edinburgh. The palace was one of the principal residences of the monarchs of Scotland in the 15th and 16th centuries. Although mai ...

for the king and queen thought to be a version of his play '' The Thrie Estaitis'' in 1540, which satirised the corruption of church and state, and which is the only complete play to survive from before the Reformation.I. Brown, T. Owen Clancy, M. Pittock, S. Manning, eds, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union, until 1707'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 256–7. The anonymous ''The Maner of the Cyring of ane Play'' (before 1568)T. van Heijnsbergen, "Culture: 7 Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1660): literature", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 127–8. and ''Philotus'' (published in London in 1603), are isolated examples of surviving plays. The latter is a vernacular Scots comedy of errors, probably designed for court performance for Mary, Queen of Scots or James VI.S. Carpenter, "Scottish drama until 1650", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), , p. 15.

Decline

Having extolled the virtues of Scots "poesie", after his accession to the English throne, James VI increasingly favoured the language of southern England. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the EnglishAuthorised King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an Bible translations into English, English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and publis ...

of the Bible. In 1617 interpreters were declared no longer necessary in the port of London because Scots and Englishmen were now "not so far different bot ane understandeth ane uther". Jenny Wormald, describes James as creating a "three-tier system, with Gaelic at the bottom and English at the top".J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 192–3. The loss of the court as a centre of patronage in 1603 was a major blow to Scottish literature. A number of Scottish poets, including William Alexander, John Murray and Robert Aytoun accompanied the king to London, where they continued to write,K. M. Brown, "Scottish identity", in B. Bradshaw and P. Roberts, eds, ''British Consciousness and Identity: The Making of Britain, 1533–1707'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), , pp. 253–3. but they soon began to anglicise

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influenc ...

their written language. James's characteristic role as active literary participant and patron in the English court made him a defining figure for English Renaissance poetry and drama, which would reach a pinnacle of achievement in his reign, but his patronage for the high style in his own Scottish tradition largely became sidelined. The only significant court poet to continue to work in Scotland after the king's departure was William Drummond of Hawthornden (1585–1649), and he largely abandoned Scots for a form of court English. The most influential Scottish literary figure of the mid-seventeenth century, Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty (1611 – c. 1660), who translated ''The Works of Rabelais'', worked largely in English, only using occasional Scots for effect. In the late seventeenth century it looked as if Scots might disappear as a literary language.

Revival

After the Union in 1707 and the shift of political power to England, the use of Scots was discouraged by many in authority and education. Intellectuals of theScottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment ( sco, Scots Enlichtenment, gd, Soillseachadh na h-Alba) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century ...

like David Hume and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

, went to great lengths to get rid of every Scotticism from their writings. Following such examples, many well-off Scots took to learning English through the activities of those such as Thomas Sheridan Thomas Sheridan may refer to:

*Thomas Sheridan (divine) (1687–1738), Anglican divine

*Thomas Sheridan (actor) (1719–1788), Irish actor and teacher of elocution

*Thomas Sheridan (soldier) (1775–1817/18)

*Thomas B. Sheridan (born 1931), America ...

, who in 1761 gave a series of lectures on English elocution

Elocution is the study of formal speaking in pronunciation, grammar, style, and tone as well as the idea and practice of effective speech and its forms. It stems from the idea that while communication is symbolic, sounds are final and compelli ...

. Charging a guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

at a time (about £ in today's money,) they were attended by over 300 men, and he was made a freeman of the City of Edinburgh. Following this, some of the city's intellectuals formed the ''Select Society for Promoting the Reading and Speaking of the English Language in Scotland''. From such eighteenth-century activities grew Scottish Standard English

Scottish English ( gd, Beurla Albannach) is the set of varieties of the English language spoken in Scotland. The transregional, standardised variety is called Scottish Standard English or Standard Scottish English (SSE). Scottish Standard ...

. Scots remained the vernacular of many rural communities and the growing number of urban working class Scots.

Allan Ramsay Allan Ramsay may refer to:

*Allan Ramsay (poet) or Allan Ramsay the Elder (1686–1758), Scottish poet

*Allan Ramsay (artist) or Allan Ramsay the Younger (1713–1784), Scottish portrait painter

*Allan Ramsay (diplomat) (1937–2022), British diplom ...

(1686–1758) was the most important literary figure of the era, often described as leading a "vernacular revival". He laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, publishing ''The Ever Green'' (1724), a collection that included many major poetic works of the Stewart period. He led the trend for pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

poetry, helping to develop the Habbie stanza The Burns stanza is a verse form named after the Scottish poet Robert Burns, who used it in some fifty poems. It was not, however, invented by Burns, and prior to his use of it was known as the standard Habbie, after the piper Habbie Simpson (1550� ...

, which would be later be used by Robert Burns as a poetic form. His ''Tea-Table Miscellany'' (1724–37) contained poems old Scots folk material, his own poems in the folk style and "gentilizings" of Scots poems in the English neo-classical style. Ramsay was part of a community of poets working in Scots and English. These included William Hamilton of Gilbertfield

William Hamilton (1665? – 24 May 1751) was a Scottish poet. He wrote comic, mock-tragic poetry such as "''The Last Dying Words of Bonny Heck''" - a once-champion hare coursing greyhound in the East Neuk of Fife who was about to be hanged, ...

(c. 1665 – 1751), Robert Crawford (1695–1733), Alexander Ross (1699–1784), the Jacobite William Hamilton of Bangour (1704–1754), socialite Alison Rutherford Cockburn (1712–1794), and poet and playwright James Thomson (1700–1748). Also important was Robert Fergusson (1750–1774), a largely urban poet, recognised in his short lifetime as the unofficial "laureate" of Edinburgh. His most famous work was his unfinished long poem, ''Auld Reekie'' (1773), dedicated to the life of the city. His borrowing from a variety of dialects prefigured the creation of Synthetic Scots

Lallans (; a variant of the Modern Scots word ''lawlands'' meaning the lowlands of Scotland), is a term that was traditionally used to refer to the Scots language as a whole. However, more recent interpretations assume it refers to the dialects ...

in the twentieth century and he would be a major influence on Robert Burns.

Burns (1759–1796), an Ayrshire poet and lyricist, is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and a major figure in the Romantic movement. As well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne

"Auld Lang Syne" (: note "s" rather than "z") is a popular song, particularly in the English-speaking world. Traditionally, it is sung to bid farewell to the old year at the stroke of midnight on New Year's Eve. By extension, it is also often ...

" is often sung at Hogmanay

Hogmanay ( , ) is the Scots word for the last day of the old year and is synonymous with the celebration of the New Year in the Scottish manner. It is normally followed by further celebration on the morning of New Year's Day (1 January) or i ...

(the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae

"Scots Wha Hae" (English: ''Scots Who Have''; gd, Brosnachadh Bhruis) is a patriotic song of Scotland written using both words of the Scots language and English, which served for centuries as an unofficial national anthem of the country, but h ...

" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country. Burns's poetry drew upon a substantial familiarity with and knowledge of Classical, Biblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

, and English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from United Kingdom, its crown dependencies, the Republic of Ireland, the United States, and the countries of the former British Empire. ''The Encyclopaedia Britannica'' defines E ...

, as well as the Scottish Makar tradition.Robert Burns:Literary Style

", retrieved 24 September 2010. Burns was skilled in writing not only in the Scots language but also in the Scottish English dialect of the English language. Some of his works, such as "Love and Liberty" (also known as "The Jolly Beggars"), are written in both Scots and English for various effects.Robert Burns:

hae meat

, retrieved 24 September 2010. His themes included republicanism,

radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

ism, Scottish patriotism

Scottish national identity is a term referring to the sense of national identity, as embodied in the shared and characteristic culture, languages and traditions, of the Scottish people.

Although the various dialects of Gaelic, the Scots lan ...

, anticlericalism, class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

inequalities, gender roles, commentary on the Scottish Kirk of his time, Scottish cultural identity

Scottish national identity is a term referring to the sense of national identity, as embodied in the shared and characteristic culture, languages and traditions, of the Scottish people.

Although the various dialects of Gaelic, the Scots lang ...

, poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse social, economic, and political causes and effects. When evaluating poverty in ...

, sexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied ...

, and the beneficial aspects of popular socialising.Red Star Cafe:to the Kibble

" Retrieved 24 September 2010.

Marginalisation

Scottish poetry is often seen as entering a period of decline in the nineteenth century, with Scots-language poetry criticised for its use of parochial dialect.L. Mandell, "Nineteenth-century Scottish poetry", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 301–07. Conservative and anti-radicalBurns club

Burns Clubs exist throughout the world to encourage and cherish the memory of Robert Burns, to foster a love of his writings and generally to encourage an interest in the Scots Language and Literature.Robert Burns' life and work and poets who fixated on the "Burns stanza" as a form.G. Carruthers, ''Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), , pp. 58–9. Scottish poetry has been seen as descending into infantalism as exemplified by the highly popular

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by modernism and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure in the movement was

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by modernism and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure in the movement was

Whistle Binkie

''Whistle-Binkie, or, The piper of the party: Being a collection of songs for the social circle'' was a Scottish poetry and song anthology first appearing in 1832. There were later volumes under the same title, at least four more anthologies, and ...

anthologies, which appeared 1830–90 and which notoriously included in one volume "Wee Willie Winkie

"Wee Willie Winkie" is a Scottish nursery rhyme whose titular figure has become popular as a personification of sleep. The poem was written by William Miller and titled "Willie Winkie", first published in '' Whistle-binkie: Stories for the Fire ...

" by William Miler (1810–1872). This tendency has been seen as leading late-nineteenth-century Scottish poetry into the sentimental parochialism of the Kailyard school

The Kailyard school (1880–1914) is a proposed literary movement of Scottish fiction dating from the last decades of the 19th century.

Origin and etymology

It was first given the name in an article published April 1895 in the ''New Review'' by ...

.M. Lindsay and L. Duncan, ''The Edinburgh Book of Twentieth-Century Scottish Poetry'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), , pp. xxxiv–xxxv. Poets from the lower social orders who used Scots included the weaver-poet William Thom (1799–1848), whose his "A chieftain unknown to the Queen" (1843) combined simple Scots language with a social critique of Queen Victoria's visit to Scotland.

Walter Scott (1771–1832), the leading literary figure of the era began his career as a ballad collector and became the most popular poet in Britain and then its most successful novelist. His works were largely written in English and Scots was largely confined to dialogue or interpolated narrative, in a model that would be followed by other novelists such as John Galt (1779–1839) and later Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894). James Hogg (1770–1835) worked largely in Scots, providing a counterpart to Scott's work in English. Popular Scottish newspapers regularly included articles and commentary in the vernacular.

There was an interest in translations into Scots from other Germanic languages, such as Danish, Swedish and German. These included Robert Jamieson's (c. 1780–1844) ''Popular Ballads And Songs From Tradition, Manuscripts And Scarce Editions With Translations Of Similar Pieces From The Ancient Danish Language'' and ''Illustrations of Northern Antiquities

''Illustrations of Northern Antiquities'' (1814), or to give its full title ''Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, from the Earlier Teutonic and Scandinavian Romances; Being an Abstract of the Book of Heroes, and Nibelungen Lay; with Translatio ...

'' (1814) and

Robert Williams Buchanan

Robert Williams Buchanan (18 August 1841 – 10 June 1901) was a Scottish poet, novelist and dramatist.

Early life and education

He was the son of Robert Buchanan (1813–1866), Owenite lecturer and journalist, and was born at Caverswall, S ...

's (1841–1901) ''Ballad Stories of the Affections'' (1866).

Twentieth-century renaissance

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by modernism and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure in the movement was

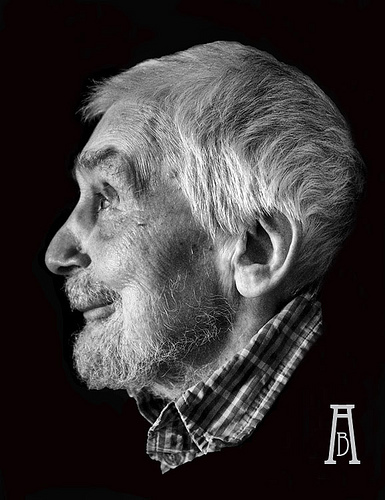

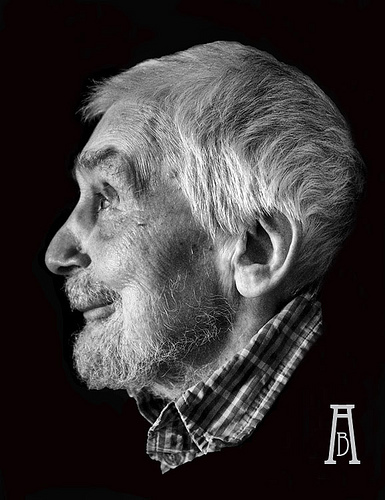

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by modernism and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure in the movement was Hugh MacDiarmid

Christopher Murray Grieve (11 August 1892 – 9 September 1978), best known by his pen name Hugh MacDiarmid (), was a Scottish poet, journalist, essayist and political figure. He is considered one of the principal forces behind the Scottish Rena ...

(the pseudonym of Christopher Murray Grieve, 1892–1978). MacDiarmid attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature in poetic works including " A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle" (1936), developing a form of Synthetic Scots that combined different regional dialects and archaic terms. Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poets Edwin Muir (1887–1959) and William Soutar

William Soutar (28 April 1898 – 15 October 1943) was a Scottish poet and diarist who wrote in English and in Braid Scots. He is known best for his epigrams.

Life and works

William Soutar was born on 28 April 1898 on South Inch Terrace in P ...

(1898–1943), who pursued an exploration of identity, rejecting nostalgia and parochialism and engaging with social and political issues. Some writers that emerged after the Second World War followed MacDiarmid by writing in Scots, including Robert Garioch

Robert Garioch Sutherland (9 May 1909 – 26 April 1981) was a Scottish poet and translator. His poetry was written almost exclusively in the Scots language, he was a key member in the literary revival of the language in the mid-20th century ...

(1909–1981) and Sydney Goodsir Smith (1915–1975). The Glaswegian poet Edwin Morgan (1920–2010) became known for translations of works from a wide range of European languages. He was also the first Scots Makar (the official national poet), appointed by the inaugural Scottish government in 2004. Alexander Gray was an academic and poet, but is chiefly remembered for this translations into Scots from the German and Danish ballad traditions into Scots, including ''Arrows. A Book of German Ballads and Folksongs Attempted in Scots'' (1932) and ''Four-and-Forty. A Selection of Danish Ballads Presented in Scots'' (1954).

The generation of poets that grew up in the postwar period included Douglas Dunn (born 1942), whose work has often seen a coming to terms with class and national identity within the formal structures of poetry and commenting on contemporary events, as in ''Barbarians'' (1979) and ''Northlight'' (1988). His most personal work is contained in the collection of ''Elegies'' (1985), which deal with the death of his first wife from cancer."Scottish poetry" in S. Cushman, C. Cavanagh, J. Ramazani and P. Rouzer, eds, ''The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics: Fourth Edition'' (Princeton University Press, 2012), , pp. 1276–9. Tom Leonard (born 1944), works in the Glaswegian dialect, pioneering the working class voice in Scottish poetry.G. Carruthers, ''Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), , pp. 67–9. Liz Lochhead (born 1947) also explored the lives of working-class people of Glasgow, but added an appreciation of female voices within a sometimes male dominated society. She also adapted classic texts into Scots, with versions of Molière's '' Tartuffe'' (1985) and '' The Misanthrope'' (1973–2005), while Edwin Morgan translated '' Cyrano de Bergerac'' (1992).

The Scottish Renaissance increasingly concentrated on the novel, particularly after the 1930s when Hugh MacDiarmid was living in isolation in Shetland and many of these were written in English and not Scots. However, George Blake pioneered the exploration of the experiences of the working class in his major works such as ''The Shipbuilders'' (1935). Lewis Grassic Gibbon, the pseudonym of James Leslie Mitchell, produced one of the most important realisations of the ideas of the Scottish Renaissance in his trilogy '' A Scots Quair'' (''Sunset Song

''Sunset Song'' is a 1932 novel by Scottish writer Lewis Grassic Gibbon. It is considered one of the most important Scottish novels of the 20th century. It is the first part of the trilogy ''A Scots Quair''.

There have been several adaptations, ...

'', 1932, ''Cloud Howe'', 1933 and ''Grey Granite'', 1934), which mixed different Scots dialects with the narrative voice.C. Craig, "Culture: modern times (1914–): the novel", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 157–9. Other works that investigated the working class included James Barke's (1905–1958), ''Major Operation'' (1936) and ''The Land of the Leal'' (1939) and J. F. Hendry

James Findlay Hendry (12 September 1912 – 17 December 1986) was a Scottish poet known also as an editor and writer. He was born in Glasgow, and read Modern Languages at the University of Glasgow. During World War II he served in the Royal Arti ...

's (1912–1986) ''Fernie Brae'' (1947).

From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers focused around meetings in the house of critic, poet and teacher Philip Hobsbaum (1932–2005). Also important in the movement was Peter Kravitz

Peter Kravitz is a figure in the Scottish literary scene. He was born in London, England, but has lived most of his life in Edinburgh. He is Jewish. He is edited '' Contemporary Scottish Fiction'', reprinted by Picador and Faber, and brought new ...

, editor of Polygon Books

Birlinn Limited is an independent publishing house based in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was established in 1992 by managing director Hugh Andrew.

Imprints

Birlinn Limited is composed of a number of imprint (trade name), imprints, including:

*Birlin ...

. These included Alasdair Gray (born 1934), whose epic '' Lanark'' (1981) built on the working class novel to explore realistic and fantastic narratives. James Kelman’s (born 1946) ''The Busconductor Hines'' (1984) and ''A Disaffection

''A Disaffection'' is a novel written by Scottish writer James Kelman, first published in 1989 by Secker and Warburg. Set in Glasgow, it is written in Scots using a stream-of-consciousness style, centring on a 29-year-old schoolteacher named P ...

'' (1989) were among the first novels to fully utilise a working class Scots voice as the main narrator. In the 1990s major, prize winning, Scottish novels that emerged from this movement included Gray's ''Poor Things

''Poor Things'' is a novel by Scottish writer Alasdair Gray, published in 1992. It won the Whitbread Award and the Guardian Fiction Prize the same year.

The novel was called "a magnificently brisk, funny, dirty, brainy book" by the '' London ...

'' (1992), which investigated the capitalist and imperial origins of Scotland in an inverted version of the Frankenstein myth, Irvine Welsh's (born 1958), ''Trainspotting

Trainspotting may refer to:

* Trainspotting (hobby), an amateur interest in railways/railroads

* ''Trainspotting'' (novel), a 1993 novel by Irvine Welsh

** ''Trainspotting'' (film), a 1996 film based on the novel

*** ''Trainspotting'' (soundtr ...

'' (1993), which dealt with the drug addiction in contemporary Edinburgh, Alan Warner

Alan Warner (born 1964) is a Scottish novelist who grew up in Connel, near Oban. His notable novels include '' Morvern Callar'' and ''The Sopranos'' – the latter being the inspiration for the play '' Our Ladies of Perpetual Succour'' and its ...

’s (born 1964) ''Morvern Callar

''Morvern Callar'' is a 1995 experimental novel by Scottish author Alan Warner. Published as his first novel, its first-person narrative—written in a Scottish dialect—explores the life and interests of the titular character following the sud ...

'' (1995), dealing with death and authorship and Kelman's ''How Late It Was, How Late

''How late it was, how late'' is a 1994 stream-of-consciousness novel written by Scottish writer James Kelman. The Glasgow-centred work is written in a working-class Scottish dialect, and follows Sammy, a shoplifter and ex-convict.

It won the ...

'' (1994), a stream of consciousness novel dealing with a life of petty crime. These works were linked by a reaction to Thatcherism that was sometimes overtly political, and explored marginal areas of experience using vivid vernacular language (including expletives and Scots dialect). ''But'n'Ben A-Go-Go

''But n Ben A-Go-Go'' is a science fiction work by Scots writer Matthew Fitt, notable for being entirely in the Scots language. The novel was first published in 2000.

According to the author, as many of the different varieties of Scots as possi ...

'' (2000) by Matthew Fitt

Matthew Fitt (born 1968) is a Scots poet and novelist. He was writer-in-residence at Greater Pollok in Glasgow, then National Scots Language Development Officer. He has translated several literary works into Scots.

Early life

Fitt was born in 19 ...

is the first cyberpunk novel written entirely in Scots. One major outlet for literature in Lallans (Lowland Scots) is ''Lallans'', the magazine of the Scots Language Society.J. Corbett, ''Language and Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997), , p. 16.

Notes

{{European literature Scottish literature European literature History of literature in Scotland Scots language