Science in the Age of Enlightenment on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of science during the Age of Enlightenment traces developments in

The history of science during the Age of Enlightenment traces developments in

The number of universities in Paris remained relatively constant throughout the 18th century. Europe had about 105 universities and colleges by 1700. North America had 44, including the newly founded

The number of universities in Paris remained relatively constant throughout the 18th century. Europe had about 105 universities and colleges by 1700. North America had 44, including the newly founded  Before the 18th century, science courses were taught almost exclusively through formal

Before the 18th century, science courses were taught almost exclusively through formal  Universities in France tended to serve a downplayed role in the development of science during the Enlightenment; that role was dominated by the scientific academies, such as the

Universities in France tended to serve a downplayed role in the development of science during the Enlightenment; that role was dominated by the scientific academies, such as the

Official scientific societies were chartered by the state in order to provide technical expertise. This advisory capacity offered scientific societies the most direct contact between the scientific community and government bodies available during the Enlightenment. State sponsorship was beneficial to the societies as it brought finance and recognition, along with a measure of freedom in management. Most societies were granted permission to oversee their own publications, control the election of new members, and the administration of the society. Membership in academies and societies was therefore highly selective. In some societies, members were required to pay an annual fee to participate. For example, the Royal Society depended on contributions from its members, which excluded a wide range of artisans and mathematicians on account of the expense. Society activities included research, experimentation, sponsoring essay prize contests, and collaborative projects between societies. A dialogue of formal communication also developed between societies and society in general through the publication of

Official scientific societies were chartered by the state in order to provide technical expertise. This advisory capacity offered scientific societies the most direct contact between the scientific community and government bodies available during the Enlightenment. State sponsorship was beneficial to the societies as it brought finance and recognition, along with a measure of freedom in management. Most societies were granted permission to oversee their own publications, control the election of new members, and the administration of the society. Membership in academies and societies was therefore highly selective. In some societies, members were required to pay an annual fee to participate. For example, the Royal Society depended on contributions from its members, which excluded a wide range of artisans and mathematicians on account of the expense. Society activities included research, experimentation, sponsoring essay prize contests, and collaborative projects between societies. A dialogue of formal communication also developed between societies and society in general through the publication of

Academies and societies served to disseminate Enlightenment science by publishing the scientific works of their members, as well as their proceedings. At the beginning of the 18th century, the ''

Academies and societies served to disseminate Enlightenment science by publishing the scientific works of their members, as well as their proceedings. At the beginning of the 18th century, the '' The limitations of such academic journals left considerable space for the rise of independent periodicals. Some eminent examples include

The limitations of such academic journals left considerable space for the rise of independent periodicals. Some eminent examples include

In Germany, practical reference works intended for the uneducated majority became popular in the 18th century. The ''Marperger Curieuses Natur-, Kunst-, Berg-, Gewerkund Handlungs-Lexicon'' (1712) explained terms that usefully described the trades and scientific and commercial education. ''Jablonksi Allgemeines Lexicon'' (1721) was better known than the ''Handlungs-Lexicon'', and underscored technical subjects rather than scientific theory. For example, over five columns of text were dedicated to wine, while geometry and

In Germany, practical reference works intended for the uneducated majority became popular in the 18th century. The ''Marperger Curieuses Natur-, Kunst-, Berg-, Gewerkund Handlungs-Lexicon'' (1712) explained terms that usefully described the trades and scientific and commercial education. ''Jablonksi Allgemeines Lexicon'' (1721) was better known than the ''Handlungs-Lexicon'', and underscored technical subjects rather than scientific theory. For example, over five columns of text were dedicated to wine, while geometry and

However, science took an ever greater step towards popular culture before Voltaire’s introduction and Châtelet’s translation. The publication of Bernard de Fontenelle's ''

However, science took an ever greater step towards popular culture before Voltaire’s introduction and Châtelet’s translation. The publication of Bernard de Fontenelle's ''

During the Enlightenment era, women were excluded from scientific societies, universities and learned professions. Women were educated, if at all, through self-study, tutors, and by the teachings of more open-minded fathers. With the exception of daughters of craftsmen, who sometimes learned their father’s profession by assisting in the workshop, learned women were primarily part of elite society. A consequence of the exclusion of women from societies and universities that prevented much independent research was their inability to access scientific instruments, such as the microscope. In fact, restrictions were so severe in the 18th century that women, including midwives, were forbidden to use

During the Enlightenment era, women were excluded from scientific societies, universities and learned professions. Women were educated, if at all, through self-study, tutors, and by the teachings of more open-minded fathers. With the exception of daughters of craftsmen, who sometimes learned their father’s profession by assisting in the workshop, learned women were primarily part of elite society. A consequence of the exclusion of women from societies and universities that prevented much independent research was their inability to access scientific instruments, such as the microscope. In fact, restrictions were so severe in the 18th century that women, including midwives, were forbidden to use  Despite these limitations, there was support for women in the sciences among some men, and many made valuable contributions to science during the 18th century. Two notable women who managed to participate in formal institutions were Laura Bassi and the Russian Princess Yekaterina Dashkova. Bassi was an Italian physicist who received a PhD from the University of Bologna and began teaching there in 1732. Dashkova became the director of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences of St. Petersburg in 1783. Her personal relationship with Empress

Despite these limitations, there was support for women in the sciences among some men, and many made valuable contributions to science during the 18th century. Two notable women who managed to participate in formal institutions were Laura Bassi and the Russian Princess Yekaterina Dashkova. Bassi was an Italian physicist who received a PhD from the University of Bologna and began teaching there in 1732. Dashkova became the director of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences of St. Petersburg in 1783. Her personal relationship with Empress

The history of science during the Age of Enlightenment traces developments in

The history of science during the Age of Enlightenment traces developments in science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

and technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, scien ...

during the Age of Reason

The Age of reason, or the Enlightenment, was an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th to 19th centuries.

Age of reason or Age of Reason may also refer to:

* Age of reason (canon law), ...

, when Enlightenment ideas and ideals were being disseminated across Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

. Generally, the period spans from the final days of the 16th and 17th-century Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transforme ...

until roughly the 19th century, after the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

(1789) and the Napoleonic era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly, the second being the Legislativ ...

(1799–1815). The scientific revolution saw the creation of the first scientific societies

A learned society (; also learned academy, scholarly society, or academic association) is an organization that exists to promote an academic discipline, profession, or a group of related disciplines such as the arts and science. Membership may ...

, the rise of Copernicanism

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular p ...

, and the displacement of Aristotelian natural philosophy and Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

's ancient medical doctrine. By the 18th century, scientific authority began to displace religious authority, and the disciplines of alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim wo ...

and astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

lost scientific credibility.

While the Enlightenment cannot be pigeonholed into a specific doctrine or set of dogmas, science came to play a leading role in Enlightenment discourse and thought. Many Enlightenment writers and thinkers had backgrounds in the sciences and associated scientific advancement with the overthrow of religion and traditional authority in favour of the development of free speech and thought. Broadly speaking, Enlightenment science greatly valued empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

and rational thought, and was embedded with the Enlightenment ideal of advancement and progress. As with most Enlightenment views, the benefits of science were not seen universally; Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

criticized the sciences for distancing man from nature and not operating to make people happier.

Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosop ...

, which had largely replaced universities as centres of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were also the backbone of the maturation of the scientific profession. Another important development was the popularization

In sociology, popularity is how much a person, idea, place, item or other concept is either liked or accorded status by other people. Liking can be due to reciprocal liking, interpersonal attraction, and similar factors. Social status can be ...

of science among an increasingly literate population. Philosophes

The ''philosophes'' () were the intellectuals of the 18th-century Enlightenment.Kishlansky, Mark, ''et al.'' ''A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, volume II: Since 1555.'' (5th ed. 2007). Few were primarily philosophe ...

introduced the public to many scientific theories, most notably through the ''Encyclopédie

''Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (English: ''Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts''), better known as ''Encyclopédie'', was a general encyclopedia publis ...

'' and the popularization of Newtonianism

Newtonianism is a philosophical and scientific doctrine inspired by the beliefs and methods of natural philosopher Isaac Newton. While Newton's influential contributions were primarily in physics and mathematics, his broad conception of the uni ...

by Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—e ...

as well as by Émilie du Châtelet, the French translator of Newton's ''Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica

(English: ''Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy'') often referred to as simply the (), is a book by Isaac Newton that expounds Newton's laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation. The ''Principia'' is written in Latin and ...

''. Some historians have marked the 18th century as a drab period in the history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Meso ...

; however, the century saw significant advancements in the practice of medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, and physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which ...

; the development of biological taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

; a new understanding of magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles ...

and electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as describe ...

; and the maturation of chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, proper ...

as a discipline, which established the foundations of modern chemistry.

Universities

The number of universities in Paris remained relatively constant throughout the 18th century. Europe had about 105 universities and colleges by 1700. North America had 44, including the newly founded

The number of universities in Paris remained relatively constant throughout the 18th century. Europe had about 105 universities and colleges by 1700. North America had 44, including the newly founded Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

and Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

. The number of university students remained roughly the same throughout the Enlightenment in most Western nations, excluding Britain, where the number of institutions and students increased. University students were generally males from affluent families, seeking a career in either medicine, law, or the Church. The universities themselves existed primarily to educate future physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

s, lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solicit ...

s and members of the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

.

The study of science under the heading of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancien ...

was divided into physics and a conglomerate grouping of chemistry and natural history, which included anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

, biology, geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other Astronomical object, astronomical objects, the features or rock (geology), rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology ...

, mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

, and zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, an ...

. Most European universities taught a Cartesian form of mechanical philosophy

The mechanical philosophy is a form of natural philosophy which compares the universe to a large-scale mechanism (i.e. a machine). The mechanical philosophy is associated with the scientific revolution of early modern Europe. One of the first expo ...

in the early 18th century, and only slowly adopted Newtonianism in the mid-18th century. A notable exception were universities in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, which under the influence of Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

focused almost entirely on Aristotelian natural philosophy until the mid-18th century; they were among the last universities to do so. Another exception occurred in the universities of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

, where University of Halle

Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg (german: Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), also referred to as MLU, is a public, research-oriented university in the cities of Halle and Wittenberg and the largest and oldest university in ...

professor Christian Wolff taught a form of Cartesianism modified by Leibnizian

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathema ...

physics.

Before the 18th century, science courses were taught almost exclusively through formal

Before the 18th century, science courses were taught almost exclusively through formal lecture

A lecture (from Latin ''lēctūra'' “reading” ) is an oral presentation intended to present information or teach people about a particular subject, for example by a university or college teacher. Lectures are used to convey critical infor ...

s. The structure of courses began to change in the first decades of the 18th century, when physical demonstrations were added to lectures. Pierre Polinière and Jacques Rohault

Jacques Rohault (; 1618 – 27 December 1672) was a French philosopher, physicist and mathematician, and a follower of Cartesianism.

Life

Rohault was born in Amiens, the son of a wealthy wine merchant, and educated in Paris. Having grown up with ...

were among the first individuals to provide demonstrations of physical principles in the classroom. Experiments ranged from swinging a bucket of water at the end of a rope, demonstrating that centrifugal force

In Newtonian mechanics, the centrifugal force is an inertial force (also called a "fictitious" or "pseudo" force) that appears to act on all objects when viewed in a rotating frame of reference. It is directed away from an axis which is paralle ...

would hold the water in the bucket, to more impressive experiments involving the use of an air-pump

An air pump is a pump for pushing air. Examples include a bicycle pump, pumps that are used to aerate an aquarium or a pond via an airstone; a gas compressor used to power a pneumatic tool, air horn or pipe organ; a bellows used to encourage a ...

. One particularly dramatic air-pump demonstration involved placing an apple inside the glass receiver of the air-pump, and removing air until the resulting vacuum caused the apple to explode. Polinière's demonstrations were so impressive that he was granted an invitation to present his course to Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

in 1722.

Some attempts at reforming the structure of the science curriculum were made during the 18th century and the first decades of the 19th century. Beginning around 1745, the Hats party in Sweden made propositions to reform the university system by separating natural philosophy into two separate faculties of physics and mathematics. The propositions were never put into action, but they represent the growing calls for institutional reform in the later part of the 18th century. In 1777, the study of arts at Cracow and Vilna

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urba ...

in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

was divided into the two new faculties of moral philosophy

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ...

and physics. However, the reform did not survive beyond 1795 and the Third Partition. During the French Revolution, all colleges and universities in France were abolished and reformed in 1808 under the single institution of the ''Université imperiale''. The ''Université'' divided the arts and sciences into separate faculties, something that had never before been done before in Europe. The United Kingdom of the Netherlands

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands ( nl, Verenigd Koninkrijk der Nederlanden; french: Royaume uni des Pays-Bas) is the unofficial name given to the Kingdom of the Netherlands as it existed between 1815 and 1839. The United Netherlands was cr ...

employed the same system in 1815. However, the other countries of Europe did not adopt a similar division of the faculties until the mid-19th century.

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at ...

. The contributions of universities in Britain were mixed. On the one hand, the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

began teaching Newtonianism early in the Enlightenment, but failed to become a central force behind the advancement of science. On the other end of the spectrum were Scottish universities, which had strong medical faculties and became centres of scientific development.Burns, (2003), entry: 239. Under Frederick II, German universities began to promote the sciences. Christian Wolff's unique blend of Cartesian-Leibnizian physics began to be adopted in universities outside of Halle. The University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen, (german: Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of Göttingen, Germany. Founded ...

, founded in 1734, was far more liberal than its counterparts, allowing professors to plan their own courses and select their own textbooks. Göttingen also emphasized research and publication. A further influential development in German universities was the abandonment of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

in favour of the German vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

.

In the 17th century, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

had played a significant role in the advancement of the sciences, including Isaac Beeckman

Isaac Beeckman (10 December 1588van Berkel, p10 – 19 May 1637) was a Dutch philosopher and scientist, who, through his studies and contact with leading natural philosophers, may have "virtually given birth to modern atomism".Harold J. Cook, in ...

's mechanical philosophy and Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists o ...

' work on the calculus and in astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

. Professors at universities in the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

were among the first to adopt Newtonianism. From the University of Leiden

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; nl, Universiteit Leiden) is a public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. The university was founded as a Protestant university in 1575 by William, Prince of Orange, as a reward to the city of Le ...

, Willem 's Gravesande

Willem Jacob 's Gravesande (26 September 1688 – 28 February 1742) was a Dutch mathematician and natural philosopher, chiefly remembered for developing experimental demonstrations of the laws of classical mechanics and the first experimental m ...

's students went on to spread Newtonianism to Harderwijk

Harderwijk (; Dutch Low Saxon: ) is a municipality and city of the Netherlands.

It is served by the Harderwijk railway station.

Its population centres are Harderwijk and Hierden.

Harderwijk is on the western boundary of the Veluwe. The so ...

and Franeker

Franeker (; fry, Frjentsjer) is one of the eleven historical cities of Friesland and capital of the municipality of Waadhoeke. It is located north of the Van Harinxmakanaal and about 20 km west of Leeuwarden. As of 1 January 2014, it had 12 ...

, among other Dutch universities, and also to the University of Amsterdam

The University of Amsterdam (abbreviated as UvA, nl, Universiteit van Amsterdam) is a public research university located in Amsterdam, Netherlands. The UvA is one of two large, publicly funded research universities in the city, the other being ...

.

While the number of universities did not dramatically increase during the Enlightenment, new private and public institutions added to the provision of education. Most of the new institutions emphasized mathematics as a discipline, making them popular with professions that required some working knowledge of mathematics, such as merchants, military and naval officers, and engineers. Universities, on the other hand, maintained their emphasis on the classics, Greek, and Latin, encouraging the popularity of the new institutions with individuals who had not been formally educated.

Societies and Academies

Scientific academies and societies grew out of the Scientific Revolution as the creators of scientific knowledge in contrast to the scholasticism of the university. During the Enlightenment, some societies created or retained links to universities. However, contemporary sources distinguished universities from scientific societies by claiming that the university's utility was in the transmission of knowledge, while societies functioned to create knowledge. As the role of universities in institutionalized science began to diminish, learned societies became the cornerstone of organized science. After 1700 a tremendous number of official academies and societies were founded in Europe and by 1789 there were over seventy official scientific societies . In reference to this growth, Bernard de Fontenelle coined the term "the Age of Academies" to describe the 18th century. National scientific societies were founded throughout the Enlightenment era in the urban hotbeds of scientific development across Europe. In the 17th century theRoyal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

(1662), the Paris ''Académie Royale des Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at the ...

'' (1666), and the Berlin '' Akademie der Wissenschaften'' (1700) were founded. Around the start of the 18th century, the '' Academia Scientiarum Imperialis'' (1724) in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, and the '' Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien'' (Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences) (1739) were created. Regional and provincial societies emerged from the 18th century in Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different na ...

, Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

, Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan a ...

, Dijon

Dijon (, , ) (dated)

* it, Digione

* la, Diviō or

* lmo, Digion is the prefecture of the Côte-d'Or department and of the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region in northeastern France. the commune had a population of 156,920.

The earlie ...

, Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

s, Montpellier

Montpellier (, , ; oc, Montpelhièr ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the department of Hérault. In 2018, 290,053 people l ...

and Uppsala

Uppsala (, or all ending in , ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the county seat of Uppsala County and the fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inhabitants in 2019.

Located north of the ca ...

. Following this initial period of growth, societies were founded between 1752 and 1785 in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Göttingen, Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (german: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's ...

, Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

, Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

and Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

. The development of unchartered societies, such as the private the '' Naturforschende Gesellschaft'' of Danzig (1743) and Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 ...

of Birmingham (1766–1791), occurred alongside the growth of national, regional and provincial societies.

Official scientific societies were chartered by the state in order to provide technical expertise. This advisory capacity offered scientific societies the most direct contact between the scientific community and government bodies available during the Enlightenment. State sponsorship was beneficial to the societies as it brought finance and recognition, along with a measure of freedom in management. Most societies were granted permission to oversee their own publications, control the election of new members, and the administration of the society. Membership in academies and societies was therefore highly selective. In some societies, members were required to pay an annual fee to participate. For example, the Royal Society depended on contributions from its members, which excluded a wide range of artisans and mathematicians on account of the expense. Society activities included research, experimentation, sponsoring essay prize contests, and collaborative projects between societies. A dialogue of formal communication also developed between societies and society in general through the publication of

Official scientific societies were chartered by the state in order to provide technical expertise. This advisory capacity offered scientific societies the most direct contact between the scientific community and government bodies available during the Enlightenment. State sponsorship was beneficial to the societies as it brought finance and recognition, along with a measure of freedom in management. Most societies were granted permission to oversee their own publications, control the election of new members, and the administration of the society. Membership in academies and societies was therefore highly selective. In some societies, members were required to pay an annual fee to participate. For example, the Royal Society depended on contributions from its members, which excluded a wide range of artisans and mathematicians on account of the expense. Society activities included research, experimentation, sponsoring essay prize contests, and collaborative projects between societies. A dialogue of formal communication also developed between societies and society in general through the publication of scientific journal

In academic publishing, a scientific journal is a periodical publication intended to further the progress of science, usually by reporting new research.

Content

Articles in scientific journals are mostly written by active scientists such ...

s. Periodicals

A periodical literature (also called a periodical publication or simply a periodical) is a published work that appears in a new edition on a regular schedule. The most familiar example is a newspaper, but a magazine or a journal are also exampl ...

offered society members the opportunity to publish, and for their ideas to be consumed by other scientific societies and the literate public. Scientific journals, readily accessible to members of learned societies, became the most important form of publication for scientists during the Enlightenment.

Periodicals

Academies and societies served to disseminate Enlightenment science by publishing the scientific works of their members, as well as their proceedings. At the beginning of the 18th century, the ''

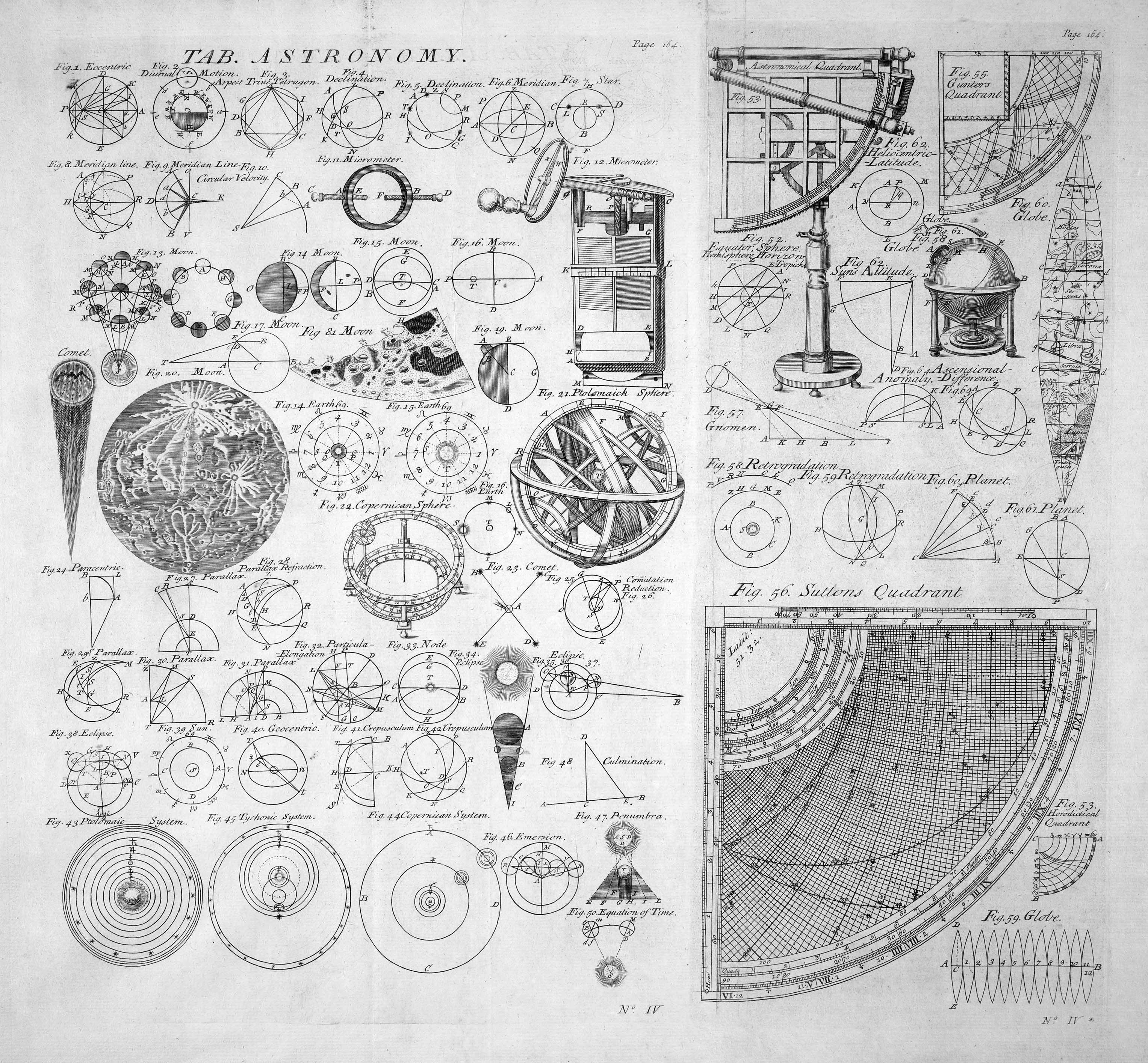

Academies and societies served to disseminate Enlightenment science by publishing the scientific works of their members, as well as their proceedings. At the beginning of the 18th century, the ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'' is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society. In its earliest days, it was a private venture of the Royal Society's secretary. It was established in 1665, making it the first journa ...

'', published by the Royal Society of London, was the only scientific periodical being published on a regular, quarterly

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

basis. The Paris Academy of Sciences, formed in 1666, began publishing in volumes of memoirs rather than a quarterly journal, with periods between volumes sometimes lasting years. While some official periodicals may have published more frequently, there was still a long delay from a paper’s submission for review to its actual publication. Smaller periodicals, such as ''Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

'', were only published when enough content was available to complete a volume.Burns, (2003), entry: 199. At the Paris Academy, there was an average delay of three years for publication. At one point the period extended to seven years. The Paris Academy processed submitted articles through the '' Comité de Librarie'', which had the final word on what would or would not be published. In 1703, the mathematician Antoine Parent

Antoine Parent (September 16, 1666 – September 26, 1716) was a French mathematician, born in Paris and died there, who wrote in 1700 on analytical geometry

In classical mathematics, analytic geometry, also known as coordinate geometry or Carte ...

began a periodical, ''Researches in Physics and Mathematics'', specifically to publish papers that had been rejected by the ''Comité''.

The limitations of such academic journals left considerable space for the rise of independent periodicals. Some eminent examples include

The limitations of such academic journals left considerable space for the rise of independent periodicals. Some eminent examples include Johann Ernst Immanuel Walch

Johann Ernst Immanuel Walch (29 August 1725 – 1 December 1778) was a German theologian, linguist, and naturalist from Jena.

Life

The son of the theologian Johann Georg Walch, he studied Semitic languages at the University of Jena, and also natu ...

's ''Der Naturforscher

''Der Naturforscher'' ( "The Naturalist") was a German scientific publication of the Enlightenment devoted to natural history. It was published yearly from 1774 to 1804, by J. J. Gebauers Witwe and Joh. Jac. Gebauer at Halle and edited first ...

'' (The Natural Investigator) (1725–1778), ''Journal des sçavans

The ''Journal des sçavans'' (later renamed ''Journal des savans'' and then ''Journal des savants,'' lit. ''Journal of the Learned''), established by Denis de Sallo, is the earliest academic journal published in Europe. It is thought to be the ea ...

'' (1665–1792), the Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

''Mémoires de Trévoux

''Mémoires'' (''Memories'') is an artist's book made by the French social critic Guy Debord in collaboration with the Danish artist Asger Jorn. Its last page mentions that it was printed in 1959, however, it was printed in December 1958. This p ...

'' (1701–1779), and Leibniz’s ''Acta Eruditorum

(from Latin: ''Acts of the Erudite'') was the first scientific journal of the German-speaking lands of Europe, published from 1682 to 1782.

History

''Acta Eruditorum'' was founded in 1682 in Leipzig by Otto Mencke, who became its first editor, ...

'' (Reports/Acts of the Scholars) (1682–1782). Independent periodicals were published throughout the Enlightenment and excited scientific interest in the general public. While the journals of the academies primarily published scientific papers, independent periodicals were a mix of reviews, abstracts, translations of foreign texts, and sometimes derivative, reprinted materials. Most of these texts were published in the local vernacular, so their continental spread depended on the language of the readers. For example, in 1761 Russian scientist Mikhail Lomonosov

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (; russian: Михаил (Михайло) Васильевич Ломоносов, p=mʲɪxɐˈil vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ , a=Ru-Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov.ogg; – ) was a Russian polymath, scientist and wr ...

correctly attributed the ring of light around Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

, visible during the planet’s transit

Transit may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Transit'' (1979 film), a 1979 Israeli film

* ''Transit'' (2005 film), a film produced by MTV and Staying-Alive about four people in countries in the world

* ''Transit'' (2006 film), a 2006 ...

, as the planet's atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A ...

; however, because few scientists understood Russian outside of Russia, his discovery was not widely credited until 1910.

Some changes in periodicals occurred during the course of the Enlightenment. First, they increased in number and size. There was also a move away from publishing in Latin in favour of publishing in the vernacular. Experimental descriptions became more detailed and began to be accompanied by reviews. In the late 18th century, a second change occurred when a new breed of periodical began to publish monthly about new developments and experiments in the scientific community. The first of this kind of journal was François Rozier

Jean-Baptiste François Rozier (23 January 1734 in Saint-Nizier parish, Lyon – 28/29 September 1793 in Lyon) was a French botanist and agronomist.

Life

Rozier was the son of Antoine Rozier (a squire, king's counselor and provincial controll ...

's ''Observations sur la physiques, sur l'histoire naturelle et sur les arts'', commonly referred to as "Rozier's journal", which was first published in 1772. The journal allowed new scientific developments to be published relatively quickly compared to annuals and quarterlies. A third important change was the specialization seen in the new development of disciplinary journals. With a wider audience and ever increasing publication material, specialized journals such as Curtis' ''Botanical Magazine

''The Botanical Magazine; or Flower-Garden Displayed'', is an illustrated publication which began in 1787. The longest running botanical magazine, it is widely referred to by the subsequent name ''Curtis's Botanical Magazine''.

Each of the issue ...

'' (1787) and the '' Annals de Chimie'' (1789) reflect the growing division between scientific disciplines in the Enlightenment era.

Encyclopedias and dictionaries

Although the existence ofdictionaries

A dictionary is a listing of lexemes from the lexicon of one or more specific languages, often arranged alphabetically (or by radical and stroke for ideographic languages), which may include information on definitions, usage, etymologies, ...

and encyclopedia

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

spanned into ancient times, and would be nothing new to Enlightenment readers, the texts changed from simply defining words in a long running list to far more detailed discussions of those words in 18th-century encyclopedic dictionaries. The works were part of an Enlightenment movement to systematize knowledge and provide education to a wider audience than the educated elite. As the 18th century progressed, the content of encyclopedias also changed according to readers’ tastes. Volumes tended to focus more strongly on secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

affairs, particularly science and technology, rather than matters of theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

.

Along with secular matters, readers also favoured an alphabetical ordering scheme over cumbersome works arranged along thematic lines. The historian Charles Porset

Charles Porset (15 April 1944 – 25 May 2011, aged 67) was a French writer and historian. He wrote numerous books, articles and papers on the "Fait Masonic" in the eighteenth century.

Biography

Charles Porset taught philosophy in high school ...

, commenting on alphabetization, has said that “as the zero degree of taxonomy, alphabetical order authorizes all reading strategies; in this respect it could be considered an emblem of the Enlightenment.” For Porset, the avoidance of thematic and hierarchical

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important ...

systems thus allows free interpretation of the works and becomes an example of egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all h ...

. Encyclopedias and dictionaries also became more popular during the Age of Reason as the number of educated consumers who could afford such texts began to multiply. In the later half of the 18th century, the number of dictionaries and encyclopedias published by decade increased from 63 between 1760 and 1769 to approximately 148 in the decade proceeding the French Revolution (1780–1789). Along with growth in numbers, dictionaries and encyclopedias also grew in length, often having multiple print runs that sometimes included in supplemented editions.

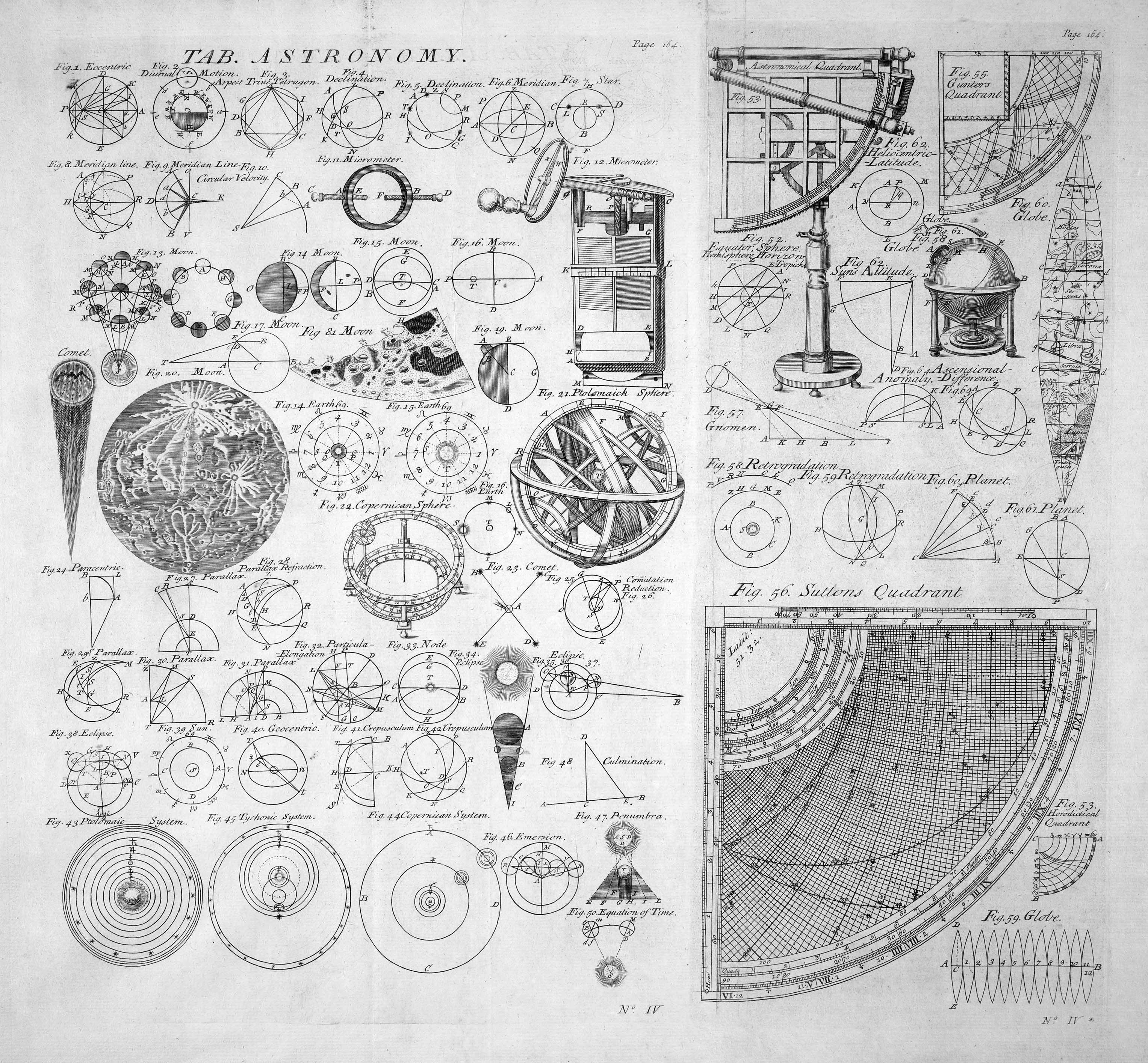

The first technical dictionary was drafted by John Harris and entitled '' Lexicon Technicum: Or, An Universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences''. Harris’ book avoided theological and biographical entries; instead it concentrated on science and technology. Published in 1704, the ''Lexicon technicum'' was the first book to be written in English that took a methodical approach to describing mathematics and commercial arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers— addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th ...

along with the physical sciences and navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation ...

. Other technical dictionaries followed Harris’ model, including Ephraim Chambers

Ephraim Chambers ( – 15 May 1740) was an English writer and encyclopaedist, who is primarily known for producing the '' Cyclopaedia, or a Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences''.

Biography

Chambers was born in Milton near Kendal, Westmo ...

’ '' Cyclopaedia'' (1728), which included five editions, and was a substantially larger work than Harris’. The folio

The term "folio" (), has three interconnected but distinct meanings in the world of books and printing: first, it is a term for a common method of arranging sheets of paper into book form, folding the sheet only once, and a term for a book ma ...

edition of the work even included foldout engravings. The ''Cyclopaedia'' emphasized Newtonian theories, Lockean

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

philosophy, and contained thorough examinations of technologies, such as engraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an in ...

, brewing

Brewing is the production of beer by steeping a starch source (commonly cereal grains, the most popular of which is barley) in water and fermenting the resulting sweet liquid with yeast. It may be done in a brewery by a commercial brewer ...

, and dyeing

Dyeing is the application of dyes or pigments on textile materials such as fibers, yarns, and fabrics with the goal of achieving color with desired color fastness. Dyeing is normally done in a special solution containing dyes and particular c ...

.  In Germany, practical reference works intended for the uneducated majority became popular in the 18th century. The ''Marperger Curieuses Natur-, Kunst-, Berg-, Gewerkund Handlungs-Lexicon'' (1712) explained terms that usefully described the trades and scientific and commercial education. ''Jablonksi Allgemeines Lexicon'' (1721) was better known than the ''Handlungs-Lexicon'', and underscored technical subjects rather than scientific theory. For example, over five columns of text were dedicated to wine, while geometry and

In Germany, practical reference works intended for the uneducated majority became popular in the 18th century. The ''Marperger Curieuses Natur-, Kunst-, Berg-, Gewerkund Handlungs-Lexicon'' (1712) explained terms that usefully described the trades and scientific and commercial education. ''Jablonksi Allgemeines Lexicon'' (1721) was better known than the ''Handlungs-Lexicon'', and underscored technical subjects rather than scientific theory. For example, over five columns of text were dedicated to wine, while geometry and logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...

were allocated only twenty-two and seventeen lines, respectively. The first edition of the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'' (1771) was modelled along the same lines as the German lexicons.

However, the prime example of reference works that systematized scientific knowledge in the age of Enlightenment were universal encyclopedia

Universal is the adjective for universe.

Universal may also refer to:

Companies

* NBCUniversal, a media and entertainment company

** Universal Animation Studios, an American Animation studio, and a subsidiary of NBCUniversal

** Universal TV, a t ...

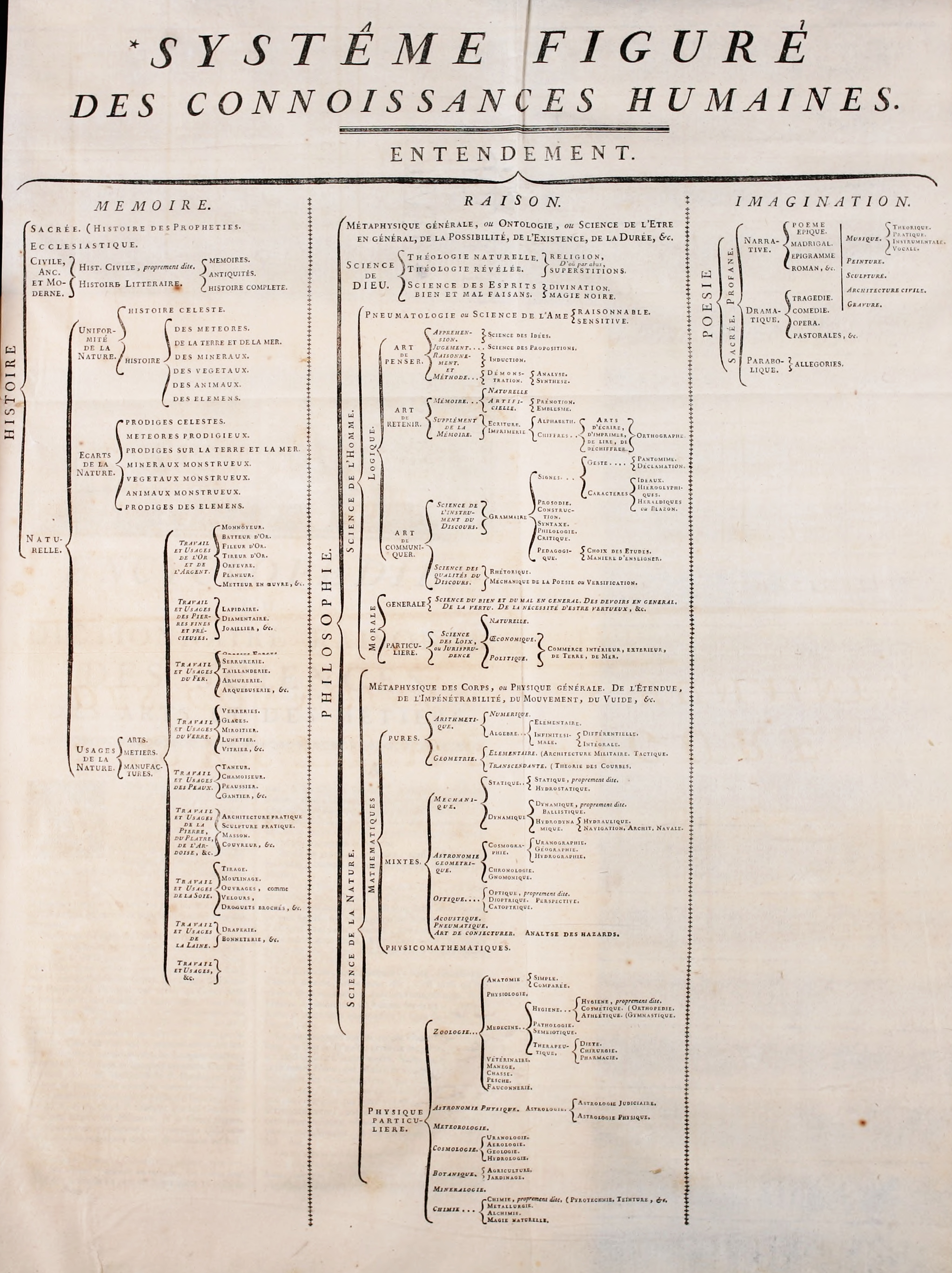

s rather than technical dictionaries. It was the goal of universal encyclopedias to record all human knowledge in a comprehensive reference work. The most well-known of these works is Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

and Jean le Rond d'Alembert

Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert (; ; 16 November 1717 – 29 October 1783) was a French mathematician, mechanician, physicist, philosopher, and music theorist. Until 1759 he was, together with Denis Diderot, a co-editor of the '' Encyclopéd ...

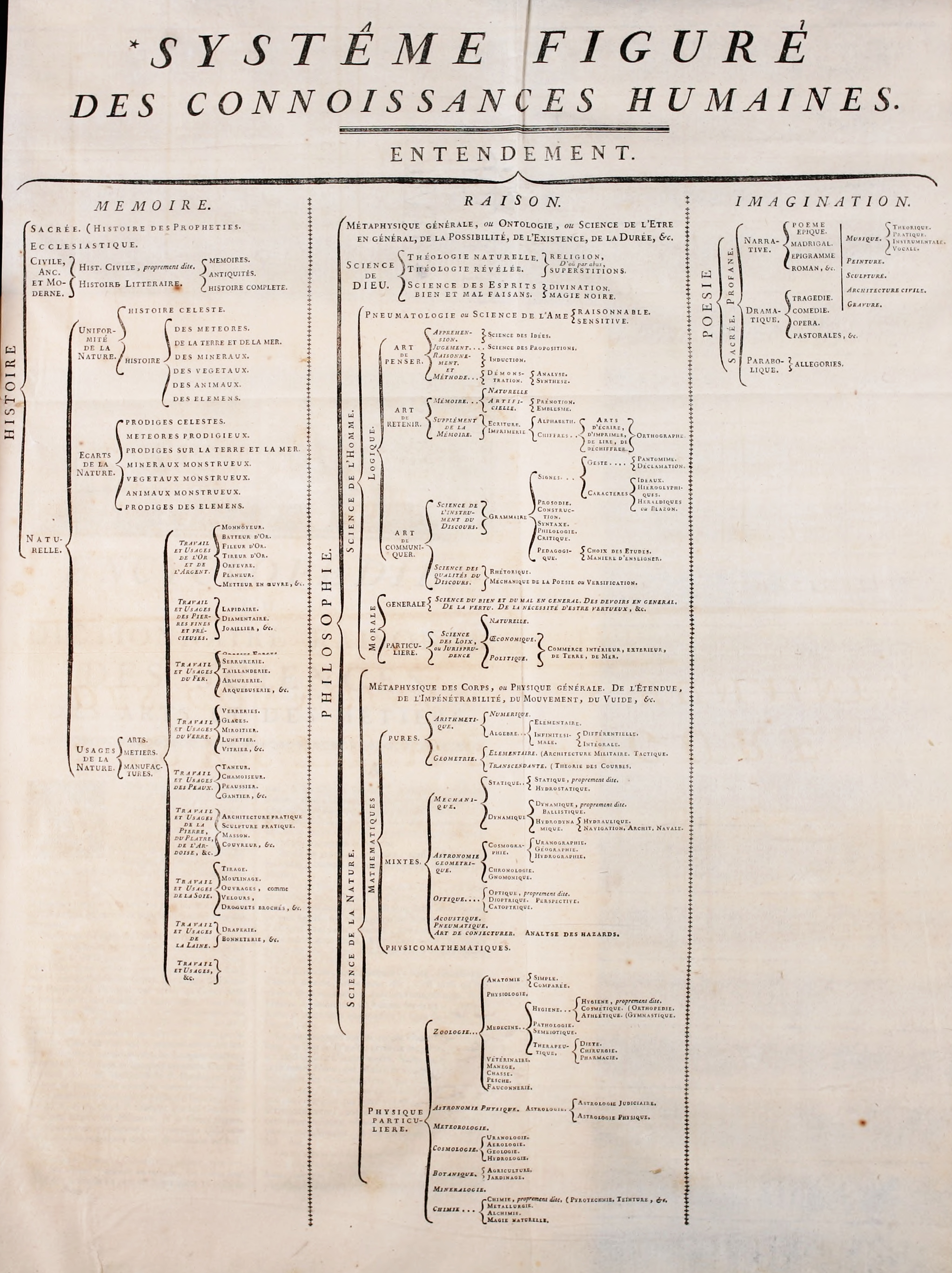

's '' Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers''. The work, which began publication in 1751, was composed of thirty-five volumes and over 71 000 separate entries. A great number of the entries were dedicated to describing the sciences and crafts in detail. In d'Alembert's ''Preliminary Discourse to the Encyclopedia of Diderot'', the work’s massive goal to record the extent of human knowledge in the arts and sciences is outlined:

The massive work was arranged according to a "tree of knowledge". The tree reflected the marked division between the arts and sciences, which was largely a result of the rise of empiricism. Both areas of knowledge were united by philosophy, or the trunk of the tree of knowledge. The Enlightenment's desacrilization of religion was pronounced in the tree’s design, particularly where theology accounted for a peripheral branch, with black magic as a close neighbour. As the ''Encyclopédie'' gained popularity, it was published in quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

and octavo

Octavo, a Latin word meaning "in eighth" or "for the eighth time", (abbreviated 8vo, 8º, or In-8) is a technical term describing the format of a book, which refers to the size of leaves produced from folding a full sheet of paper on which multip ...

editions after 1777. The quarto and octavo editions were much less expensive than previous editions, making the ''Encyclopédie'' more accessible to the non-elite. Robert Darnton estimates that there were approximately 25 000 copies of the ''Encyclopédie'' in circulation throughout France and Europe before the French Revolution. The extensive, yet affordable encyclopedia came to represent the transmission of Enlightenment and scientific education to an expanding audience.

Popularization of science

One of the most important developments that the Enlightenment era brought to the discipline of science was its popularization. An increasingly literate population seeking knowledge and education in both the arts and the sciences drove the expansion of print culture and the dissemination of scientific learning. The new literate population was due to a high rise in the availability of food. This enabled many people to rise out of poverty, and instead of paying more for food, they had money for education. Popularization was generally part of an overarching Enlightenment ideal that endeavoured “to make information available to the greatest number of people.” As public interest in natural philosophy grew during the 18th century, public lecture courses and the publication of popular texts opened up new roads to money and fame for amateurs and scientists who remained on the periphery of universities and academies.British coffeehouses

An early example of science emanating from the official institutions into the public realm was the Britishcoffeehouse

A coffeehouse, coffee shop, or café is an establishment that primarily serves coffee of various types, notably espresso, latte, and cappuccino. Some coffeehouses may serve cold drinks, such as iced coffee and iced tea, as well as other non-ca ...

. With the establishment of coffeehouses, a new public forum for political, philosophical and scientific discourse was created. In the mid-16th century, coffeehouses popped up around Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, where the academic community began to capitalize on the unregulated conversation that the coffeehouse allowed. The new social space began to be used by some scholars as a place to discuss science and experiments outside of the laboratory of the official institution. Coffeehouse patrons were only required to purchase a dish of coffee to participate, leaving the opportunity for many, regardless of financial means, to benefit from the conversation. Education was a central theme and some patrons began offering lessons and lectures to others. The chemist Peter Staehl provided chemistry lessons at Tilliard’s coffeehouse in the early 1660s. As coffeehouses developed in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, customers heard lectures on scientific subjects, such as astronomy and mathematics, for an exceedingly low price. Notable Coffeehouse enthusiasts included John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the '' Brief Lives'', his collection of short biographical pieces. He was a pioneer archaeologist ...

, Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

, James Brydges, and Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

.

Public lectures

Public lecture courses offered some scientists who were unaffiliated with official organizations a forum to transmit scientific knowledge, at times even their own ideas, and the opportunity to carve out a reputation and, in some instances, a living. The public, on the other hand, gained both knowledge and entertainment from demonstration lectures. Between 1735 and 1793, there were over seventy individuals offering courses and demonstrations for public viewers in experimental physics. Class sizes ranged from one hundred to four or five hundred attendees. Courses varied in duration from one to four weeks, to a few months, or even the entire academic year. Courses were offered at virtually any time of day; the latest occurred at 8:00 or 9:00 at night. One of the most popular start times was 6:00 pm, allowing the working population to participate and signifying the attendance of the nonelite. Barred from the universities and other institutions, women were often in attendance at demonstration lectures and constituted a significant number ofauditors

An audit is an "independent examination of financial information of any entity, whether profit oriented or not, irrespective of its size or legal form when such an examination is conducted with a view to express an opinion thereon.” Auditing ...

.

The importance of the lectures was not in teaching complex mathematics or physics, but rather in demonstrating to the wider public the principles of physics and encouraging discussion and debate. Generally, individuals presenting the lectures did not adhere to any particular brand of physics, but rather demonstrated a combination of different theories. New advancements in the study of electricity offered viewers demonstrations that drew far more inspiration among the laity than scientific papers could hold. An example of a popular demonstration used by Jean-Antoine Nollet

Jean-Antoine Nollet (; 19 November 170025 April 1770) was a French clergyman and physicist who did a number of experiments with electricity and discovered osmosis. As a deacon in the Catholic Church, he was also known as Abbé Nollet.

Biography

...

and other lecturers was the ‘electrified boy’. In the demonstration, a young boy would be suspended from the ceiling, horizontal to the floor, with silk chords. An electrical machine would then be used to electrify the boy. Essentially becoming a magnet, he would then attract a collection of items scattered about him by the lecturer. Sometimes a young girl would be called from the auditors to touch or kiss the boy on the cheek, causing sparks to shoot between the two children in what was dubbed the ‘electric kiss‘. Such marvels would certainly have entertained the audience, but the demonstration of physical principles also served an educational purpose. One 18th-century lecturer insisted on the utility of his demonstrations, stating that they were “useful for the good of society.”

Popular science in print

Increasing literacy rates in Europe during the course of the Enlightenment enabled science to enter popular culture through print. More formal works included explanations of scientific theories for individuals lacking the educational background to comprehend the original scientific text. Sir Isaac Newton’s celebrated ''Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. S ...

'' was published in Latin and remained inaccessible to readers without education in the classics until Enlightenment writers began to translate and analyze the text in the vernacular. The first French introduction to Newtonianism and the ''Principia'' was ''Eléments de la philosophie de Newton'', published by Voltaire in 1738. Émilie du Châtelet

Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet (; 17 December 1706 – 10 September 1749) was a French natural philosopher and mathematician from the early 1730s until her death due to complications during childbirth in 1749. ...

's translation of the ''Principia'', published after her death in 1756, also helped to spread Newton’s theories beyond scientific academies and the university.

However, science took an ever greater step towards popular culture before Voltaire’s introduction and Châtelet’s translation. The publication of Bernard de Fontenelle's ''

However, science took an ever greater step towards popular culture before Voltaire’s introduction and Châtelet’s translation. The publication of Bernard de Fontenelle's ''Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds

''Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds'' (french: Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes) is a popular science book by French author Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, published in 1686.

Content

The work consists of six lessons popularizing ...

'' (1686) marked the first significant work that expressed scientific theory and knowledge expressly for the laity, in the vernacular, and with the entertainment of readers in mind. The book was produced specifically for women with an interest in scientific writing and inspired a variety of similar works. These popular works were written in a discursive style, which was laid out much more clearly for the reader than the complicated articles, treatises, and books published by the academies and scientists. Charles Leadbetter

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

’s ''Astronomy'' (1727) was advertised as “a Work entirely New” that would include “short and easie Rules and Astronomical Tables.” Francesco Algarotti, writing for a growing female audience, published ''Il Newtonianism per le dame'', which was a tremendously popular work and was translated from Italian into English by Elizabeth Carter

Elizabeth Carter (pen name Eliza; 16 December 1717 – 19 February 1806) was an English poet, classicist, writer, translator, linguist, and polymath. As one of the Bluestocking Circle that surrounded Elizabeth Montagu,Encyclopaedia BritannicRet ...

. A similar introduction to Newtonianism for women was produced by Henry Pembarton. His ''A View of Sir Isaac Newton’s Philosophy'' was published by subscription. Extant records of subscribers show that women from a wide range of social standings purchased the book, indicating the growing number of scientifically inclined female readers among the middling class. During the Enlightenment, women also began producing popular scientific works themselves. Sarah Trimmer

Sarah Trimmer (''née'' Kirby; 6 January 1741 – 15 December 1810) was a writer and critic of 18th-century British children's literature, as well as an educational reformer. Her periodical, ''The Guardian of Education'', helped to define the e ...

wrote a successful natural history textbook for children entitled ''The Easy Introduction to the Knowledge of Nature'' (1782), which was published for many years after in eleven editions.

The influence of science also began appearing more commonly in poetry and literature during the Enlightenment. Some poetry became infused with scientific metaphor

A list of metaphors in the English language organised alphabetically by type. A metaphor is a literary figure of speech that uses an image, story or tangible thing to represent a less tangible thing or some intangible quality or idea; e.g., "Her ey ...

and imagery, while other poems were written directly about scientific topics. Sir Richard Blackmore

Sir Richard Blackmore (22 January 1654 – 9 October 1729), English poet and physician, is remembered primarily as the object of satire and as an epic poet, but he was also a respected medical doctor and theologian.

Earlier years

He was born ...

committed the Newtonian system to verse in ''Creation, a Philosophical Poem in Seven Books'' (1712). After Newton’s death in 1727, poems were composed in his honour for decades.Burns, (2003), entry: 158. James Thomson (1700–1748) penned his “Poem to the Memory of Newton,” which mourned the loss of Newton, but also praised his science and legacy:

While references to the sciences were often positive, there were some Enlightenment writers who criticized scientists for what they viewed as their obsessive, frivolous careers. Other antiscience writers, including William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the Romantic poetry, poetry and visual art of t ...

, chastised scientists for attempting to use physics, mechanics and mathematics to simplify the complexities of the universe, particularly in relation to God. The character of the evil scientist was invoked during this period in the romantic tradition. For example, the characterization of the scientist as a nefarious manipulator in the work of Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann.

Women in science

During the Enlightenment era, women were excluded from scientific societies, universities and learned professions. Women were educated, if at all, through self-study, tutors, and by the teachings of more open-minded fathers. With the exception of daughters of craftsmen, who sometimes learned their father’s profession by assisting in the workshop, learned women were primarily part of elite society. A consequence of the exclusion of women from societies and universities that prevented much independent research was their inability to access scientific instruments, such as the microscope. In fact, restrictions were so severe in the 18th century that women, including midwives, were forbidden to use

During the Enlightenment era, women were excluded from scientific societies, universities and learned professions. Women were educated, if at all, through self-study, tutors, and by the teachings of more open-minded fathers. With the exception of daughters of craftsmen, who sometimes learned their father’s profession by assisting in the workshop, learned women were primarily part of elite society. A consequence of the exclusion of women from societies and universities that prevented much independent research was their inability to access scientific instruments, such as the microscope. In fact, restrictions were so severe in the 18th century that women, including midwives, were forbidden to use forceps

Forceps (plural forceps or considered a plural noun without a singular, often a pair of forceps; the Latin plural ''forcipes'' is no longer recorded in most dictionaries) are a handheld, hinged instrument used for grasping and holding objects. Fo ...

. That particular restriction exemplified the increasingly constrictive, male-dominated medical community. Over the course of the 18th century, male surgeons began to assume the role of midwives in gynaecology. Some male satirists also ridiculed scientifically minded women, describing them as neglectful of their domestic role.Burns, (2003), entry: 253. The negative view of women in the sciences reflected the sentiment apparent in some Enlightenment texts that women need not, nor ought to be educated; the opinion is exemplified by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in ''Émile'':