Sarek National Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sarek National Park ( sv, Sareks nationalpark) is a

Sarek National Park is the most mountainous region in Sweden and it is the part of the country that mostly resembles an alpine countryside. Within the park are 19 summits higher than , the most noted being the second highest summit in Sweden after the

Sarek National Park is the most mountainous region in Sweden and it is the part of the country that mostly resembles an alpine countryside. Within the park are 19 summits higher than , the most noted being the second highest summit in Sweden after the  Interspersed between the valleys and the plateaux, are massive mountains, often with several summits. The main ones are:

*Sarektjåkkå, highest point: Stortoppen,

*Pårte, Pårtetjåkkå,

*Piellorieppe, Kåtokkaskatjåkkå,

*Ålkatj, (Akkatjåkko,

*Äpar,

*Skårki,

*Ruotes,

Interspersed between the valleys and the plateaux, are massive mountains, often with several summits. The main ones are:

*Sarektjåkkå, highest point: Stortoppen,

*Pårte, Pårtetjåkkå,

*Piellorieppe, Kåtokkaskatjåkkå,

*Ålkatj, (Akkatjåkko,

*Äpar,

*Skårki,

*Ruotes,

File:Rapaselet-from-piellorieppe.jpg, Rapaselet

File:Rapaselet (1994-09-03).jpg, Skyview of Rapaselet

File:Laitaure ASTER 2002-08-09.jpg, The river delta of Laitaure

The Sarek National Park lies within the

The Sarek National Park lies within the

The mountain chain was renewed and after that it was subjected to a new period of glacial erosion. In the beginning of the

The mountain chain was renewed and after that it was subjected to a new period of glacial erosion. In the beginning of the

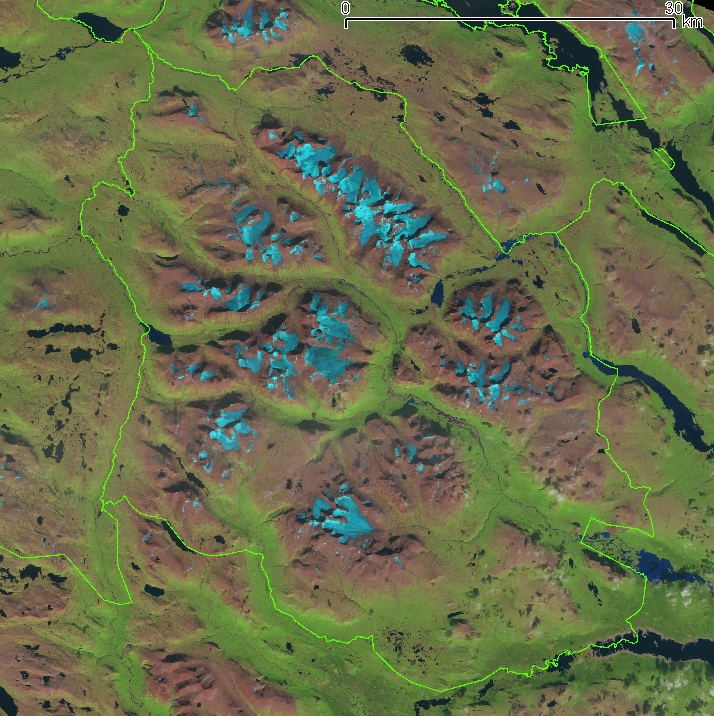

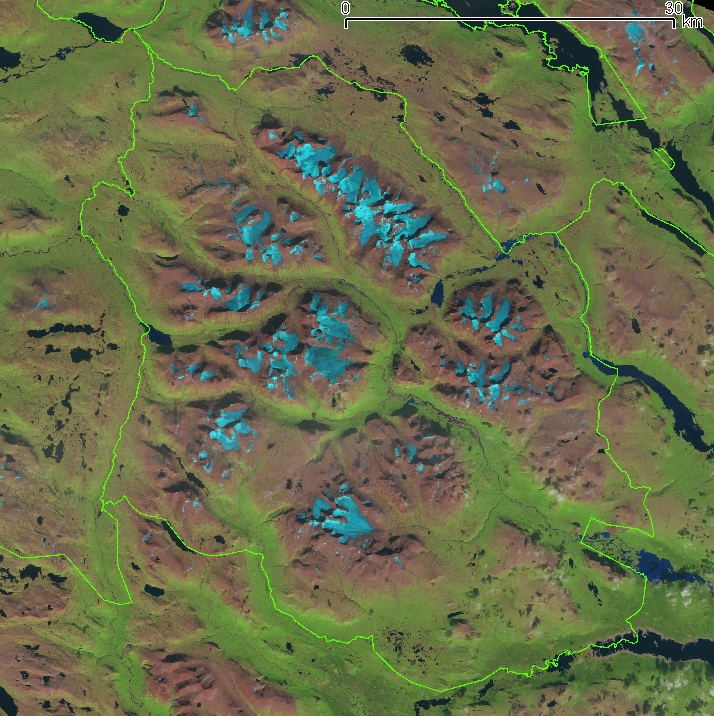

The park has over 100 glaciers, making it one of the most glacier-rich areas in Sweden. The glaciers are relatively small, the largest being Pårtejekna in Pårte at . However, some of the others are relatively large for Sweden, since the largest Swedish glacier, Stuorrajekna in Sulitelma (south of Padjelanta), measures .

The evolution of the glaciers, particularly that of the Mikka () have been studied since the end of the 19th century, especially by mineralogist and geographer

The park has over 100 glaciers, making it one of the most glacier-rich areas in Sweden. The glaciers are relatively small, the largest being Pårtejekna in Pårte at . However, some of the others are relatively large for Sweden, since the largest Swedish glacier, Stuorrajekna in Sulitelma (south of Padjelanta), measures .

The evolution of the glaciers, particularly that of the Mikka () have been studied since the end of the 19th century, especially by mineralogist and geographer

The

The  The division between the birch and coniferous forests is relatively blurred, with many of the animal species listed above also present in the subalpine zone. Some small mammals are found more frequently here than in the coniferous forests, particularly several rodents such as the

The division between the birch and coniferous forests is relatively blurred, with many of the animal species listed above also present in the subalpine zone. Some small mammals are found more frequently here than in the coniferous forests, particularly several rodents such as the

The

The

Although the park does not have the vast marshes and lakes characteristic of the rest of the region, water is nevertheless present everywhere. The humid zones are rich with a great diversity of flora and fauna. The stratification of vegetation is just as valid in the humid zones. In the montane region, the humid soils are covered with flowers such as the northern Labrador tea, cottonsedge, the

Although the park does not have the vast marshes and lakes characteristic of the rest of the region, water is nevertheless present everywhere. The humid zones are rich with a great diversity of flora and fauna. The stratification of vegetation is just as valid in the humid zones. In the montane region, the humid soils are covered with flowers such as the northern Labrador tea, cottonsedge, the

The region's first inhabitants arrived with the retreat of the inland seas 8,000 years ago. They were

The region's first inhabitants arrived with the retreat of the inland seas 8,000 years ago. They were

When the Swedish government took control over the Sami territory, the Sami had to pay the same taxes as other Swedes. In the 17th century the Sami were evangelized by the Swedes, who often built churches and markets in locations where the Sami traditionally stayed during winter.

The Swedes considered the mountains to be frightening and dangerous so they did not explore them. When the first

When the Swedish government took control over the Sami territory, the Sami had to pay the same taxes as other Swedes. In the 17th century the Sami were evangelized by the Swedes, who often built churches and markets in locations where the Sami traditionally stayed during winter.

The Swedes considered the mountains to be frightening and dangerous so they did not explore them. When the first

In 1982, the

In 1982, the

As for the majority of the Swedish national parks, the management and administration of the park is divided between the Environmental Protection Agency of Sweden and the

As for the majority of the Swedish national parks, the management and administration of the park is divided between the Environmental Protection Agency of Sweden and the

Sweden's National Parks: Sarek National Park

from the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

Trekking Sarek National Park

{{Authority control National parks of Sweden Lapland (Sweden) Geography of Norrbotten County Protected areas of the Arctic Protected areas established in 1909 1909 establishments in Sweden Tourist attractions in Norrbotten County Animal reintroduction Legislation concerning indigenous peoples Indigenous rights

national park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

in Jokkmokk Municipality

Jokkmokk Municipality (, fi, Jokimukan kunta, se, Johkamohkki gielda, fit, Jokinmukka) is a municipality in Norrbotten County in northern Sweden. Its seat is located in Jokkmokk.

The name ''Jokkmokk'' is Sami for the words "river" and "bend", ...

, Lapland in northern Sweden. Established in 1909, the park is the oldest national park in Europe. It is adjacent to two other national parks, namely Stora Sjöfallet and Padjelanta

Padjelanta ( sv, Padjelanta nationalpark) is a national park in Norrbotten County in northern Sweden. Established in 1963, it is the largest national park in Sweden with an area of , and part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site Laponia establis ...

. The shape of Sarek National Park is roughly circular with an average diameter of about .

The most noted features of the national park are six of Sweden's thirteen peaks over located within the park's boundaries. Among these is the second highest mountain in Sweden, Sarektjåkkå, whilst the massif Áhkká

Áhkká (, ), is a massif in the southwestern corner of Stora Sjöfallet National Park in northern Sweden.

The massif has twelve individual peaks and ten glaciers, of which ''Stortoppen'' is the highest at . This peak is the eighth-highest in Sw ...

is located just outside the park. The park has about 200 peaks over , 82 of which have names. Sarek is also the name of a geographical area which the national park is part of. The Sarek mountain district includes a total of eight peaks over . Due to the long trek, the mountains in the district are seldom climbed. There are approximately 100 glaciers in Sarek National Park.

Sarek is a popular area for hikers and mountaineers. Beginners in these disciplines are advised to accompany a guide since there are no marked trails or accommodations and only two bridges aside from those in the vicinity of its borders. The area is among those that receives the heaviest rainfall in Sweden, making hiking dependent on weather conditions. It is also intersected by turbulent

In fluid dynamics, turbulence or turbulent flow is fluid motion characterized by chaotic changes in pressure and flow velocity. It is in contrast to a laminar flow, which occurs when a fluid flows in parallel layers, with no disruption between t ...

streams that are hazardous to cross without proper training.

The delta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), a letter of the Greek alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* D ( NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta")

* Delta Air Lines, US

* Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19

Delta may also ...

of the Rapa River

The Rapa River ( smj, Rapaätno and sv, Rapaälven) is a tributary of the Lesser Lule River in north Norrland, in Norrbotten County, Sweden. The river stretches 75 km from its source to the mouth of Lake Tjaktjajaure (477 amsl). At the mou ...

is considered one of Europe's most noted views and the summit of mount Skierfe offers an overlook of that ice-covered, glacial

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

, trough valley.

The Pårte Scientific Station in Sarek (also known as the ''Pårte observatory'') was built in the early 1900s by Swedish mineralogist

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proces ...

and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

Axel Hamberg

Axel Hamberg (17 January 1863 – 28 June 1933) was a Swedish mineralogist, geographer and explorer. Biography

Hamberg was born in Stockholm, Sweden.

He was the son of Nils Peter Hamberg (1815-1902) and Emma Augusta Christina Härnström (18 ...

. All the building material for the huts had to be carried to the site by porters Porters may refer to:

* Porters, Virginia, an unincorporated community in Virginia, United States

* Porters, Wisconsin, an unincorporated community in Wisconsin, United States

* Porters Ski Area, a ski resort in New Zealand

* ''Porters'' (TV ser ...

.

Names of locations

In Sarek National Park, as in the most of Sápmi, a large number of the locations have names originating from theSami languages

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise net ...

. These languages have several variations and their written forms have changed over time, which explains why some placenames do not always correspond with each other in different sources.

The most common Sami names for locations or features in the park are ''tjåkkå'' or ''tjåkko'' (mountain), ''vagge'' (valley), ''jåkkå'' or ''jåkko'' (stream), ''lako'' (plateau) and ''ätno'' (river). An example of this is ''Rapaätno'', meaning Rapa River

The Rapa River ( smj, Rapaätno and sv, Rapaälven) is a tributary of the Lesser Lule River in north Norrland, in Norrbotten County, Sweden. The river stretches 75 km from its source to the mouth of Lake Tjaktjajaure (477 amsl). At the mou ...

. These names are also the official Swedish names of the locations.

Geography

Location and borders

Sarek National Park is situated in theJokkmokk Municipality

Jokkmokk Municipality (, fi, Jokimukan kunta, se, Johkamohkki gielda, fit, Jokinmukka) is a municipality in Norrbotten County in northern Sweden. Its seat is located in Jokkmokk.

The name ''Jokkmokk'' is Sami for the words "river" and "bend", ...

, Norrbotten County

Norrbotten County ( sv, Norrbottens län; se, Norrbottena leatna, fi, Norrbottenin lääni) is the northernmost county or '' län'' of Sweden. It is also the largest county by land area, almost a quarter of Sweden's total area. It shares border ...

, Sweden, north of the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at w ...

, from the Norwegian border.

The area of the park is and it is adjacent to the national parks Padjelanta

Padjelanta ( sv, Padjelanta nationalpark) is a national park in Norrbotten County in northern Sweden. Established in 1963, it is the largest national park in Sweden with an area of , and part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site Laponia establis ...

(in the west) and Stora Sjöfallet (in the north). The parks have a combined area of approximately . There are also a number of nature reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

s nearby.

Topography

Sarek National Park is the most mountainous region in Sweden and it is the part of the country that mostly resembles an alpine countryside. Within the park are 19 summits higher than , the most noted being the second highest summit in Sweden after the

Sarek National Park is the most mountainous region in Sweden and it is the part of the country that mostly resembles an alpine countryside. Within the park are 19 summits higher than , the most noted being the second highest summit in Sweden after the Kebnekaise

Kebnekaise (; from Sami or , "Cauldron Crest") is the highest mountain in Sweden. The Kebnekaise massif, which is part of the Scandinavian mountain range, has two main peaks. The glaciated southern peak used to be the highest at above sea leve ...

– the Sarektjåkkå with a height of . The lowest altitude in the park is found in the southwest, near Lake Rittakjaure, at .

The park is made up of three types of landscape, sometimes difficult to differentiate between: large valleys, massive mountains, and high plateaux. The largest valley of the park, which is also the most noted, is the Rapa Valley. This valley occupies of the park, including several branches, the most important of which are the Sarvesvagge, which climbs as far as Padjelanta, the Kuopervagge — with an area of nearly — and the Ruotesvagge, surrounded by numerous glaciers, including those of Mount Sarektjåkkå. Among the other notable valleys, outside the Rapadalen network, are the Kukkesvagge that makes up the north-eastern border of the park, and the Njåtsosvagge near the southern border. The largest plateau is the Ivarlako, east of the Pårte massif

In geology, a massif ( or ) is a section of a planet's crust that is demarcated by faults or flexures. In the movement of the crust, a massif tends to retain its internal structure while being displaced as a whole. The term also refers to a ...

, with an altitude starting at . West of Pårte, the Luottolako plateau covers an area of and has an even higher altitude at .

Interspersed between the valleys and the plateaux, are massive mountains, often with several summits. The main ones are:

*Sarektjåkkå, highest point: Stortoppen,

*Pårte, Pårtetjåkkå,

*Piellorieppe, Kåtokkaskatjåkkå,

*Ålkatj, (Akkatjåkko,

*Äpar,

*Skårki,

*Ruotes,

Interspersed between the valleys and the plateaux, are massive mountains, often with several summits. The main ones are:

*Sarektjåkkå, highest point: Stortoppen,

*Pårte, Pårtetjåkkå,

*Piellorieppe, Kåtokkaskatjåkkå,

*Ålkatj, (Akkatjåkko,

*Äpar,

*Skårki,

*Ruotes,

Climate

Hydrography

The park's main river is the Rapa River (''Rapaätno''). It originates from theglacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s of Sarektjåkkå and runs down the Rapa Valley as far as Lake Laitaure, and continues outside the park, where it joins with the Lesser Lule River which becomes a tributary of the Lule River

Lule River ( smj, Julevädno, sv, Lule älv, ''Luleälven'') is a major river in Sweden, rising in northern Sweden and flowing southeast for before reaching the Gulf of Bothnia at Luleå. It is the second longest river by watershed area or length ...

at its confluence. This river is fed by thirty glaciers, contributing to a significant flow. The specific flow, the ratio between the average flow and the drainage basin

A drainage basin is an area of land where all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, t ...

, from these waters, is the most significant in Sweden. The flow fluctuates strongly with the seasons, having an average of 100 m3⋅s−1 in July and about 4 m3⋅s−1 in winter, resulting in an average annual flow of approximately 30 m3⋅s−1. The river also transports a significant quantity of sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand an ...

. In summer, it can carry up to of sediment daily. In winter it only carries a few tons every day, resulting in an annual total of . The sediment gives the river a grey-green colour and forms large deltas

A river delta is a landform shaped like a triangle, created by deposition of sediment that is carried by a river and enters slower-moving or stagnant water. This occurs where a river enters an ocean, sea, estuary, lake, reservoir, or (more rarel ...

. The main delta is formed at the confluence of the Rapaätno with its principal tributary, the river Sarvesjokk.

Just before the confluence, the river braids

A braid (also referred to as a plait) is a complex structure or pattern formed by interlacing two or more strands of flexible material such as textile yarns, wire, or hair.

The simplest and most common version is a flat, solid, three-strande ...

for nearly , forming a zone called Rapaselet. The most noted of the deltas – and an emblem of the park – is the Laitaure delta (''Laitauredeltat''), which the river forms as it connects with Lake Laitaure. The other significant rivers correspond to the principal valleys listed above. Most of them make up the drainage basin of Lesser Lule River. The rivers in the north part of the park flow into Lake Akkajaure

Akkajaure (from smj, Áhkájávrre) is one of the largest reservoirs in Sweden. It lies at the headwaters of the Lule River in Norrbotten County, in Swedish Lappland, within the Stora Sjöfallet national park. The lake formed after the cons ...

, in the Stora Sjöfallet National Park, forming part of the hydrographic network of Lule älv.

The park also contains several lakes. The largest are the Alkajaure (altitude ), on the border between the Sarek and the Padjelanta park, and the Pierikjaure (altitude ) near the Stora Sjöfallet National Park.

Geology

Formation

The Sarek National Park lies within the

The Sarek National Park lies within the Scandinavian Mountains

The Scandinavian Mountains or the Scandes is a mountain range that runs through the Scandinavian Peninsula. The western sides of the mountains drop precipitously into the North Sea and Norwegian Sea, forming the fjords of Norway, whereas to the ...

, a mountain chain whose origin is still a matter of debate. The rocks of the Scandinavian Mountains were put in place by the Caledonian orogeny

The Caledonian orogeny was a mountain-building era recorded in the northern parts of the British Isles, the Scandinavian Mountains, Svalbard, eastern Greenland and parts of north-central Europe. The Caledonian orogeny encompasses events that occ ...

, forming a belt of deformed and displaced rocks now known as the Scandinavian Caledonides

The Scandinavian Caledonides are the vestiges of an ancient, today deeply eroded orogenic belt formed during the Silurian–Devonian continental collision of Baltica and Laurentia, which is referred to as the Scandian phase of the Caledonian oroge ...

. Caledonian rocks overlie rocks of the much older Svecokarelian and Sveconorwegian provinces

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outsi ...

. The Caledonian rocks actually form large nappe

In geology, a nappe or thrust sheet is a large sheetlike body of rock (geology), rock that has been moved more than or above a thrust fault from its original position. Nappes form in compressional tectonic settings like continental collision z ...

s ( sv, skollor) that have been thrusted over the older rocks. Much of the Caledonian rocks have been eroded since they were put in place meaning that they were once thicker and more contiguous. It is also implyed from the erosion that the nappes of Caledonian rock reached once further east than they do today. The erosion has left remaining massifs of Caledonian rocks and windows

Windows is a group of several proprietary graphical operating system families developed and marketed by Microsoft. Each family caters to a certain sector of the computing industry. For example, Windows NT for consumers, Windows Server for serv ...

of Precambrian rock. The Caledonian orogeny resulted from the collision of the Laurentia

Laurentia or the North American Craton is a large continental craton that forms the ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of North America, although ...

and Baltica

Baltica is a paleocontinent that formed in the Paleoproterozoic and now constitutes northwestern Eurasia, or Europe north of the Trans-European Suture Zone and west of the Ural Mountains.

The thick core of Baltica, the East European Craton, is mo ...

plates, 450 to 250 million years ago, with the disappearance of the Iapetus Ocean

The Iapetus Ocean (; ) was an ocean that existed in the late Neoproterozoic and early Paleozoic eras of the geologic timescale (between 600 and 400 million years ago). The Iapetus Ocean was situated in the southern hemisphere, between the paleoco ...

by subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

. This happened just before the formation of the chain and was caused by the appearance of a rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-grabe ...

, which finally led to the creation of the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

. The chain, once split open, continued to erode until it formed a peneplain

390px, Sketch of a hypothetical peneplain formation after an orogeny.

In geomorphology and geology, a peneplain is a low-relief plain formed by protracted erosion. This is the definition in the broadest of terms, albeit with frequency the usage ...

.

Starting about 60 million years ago, both the Scandinavian and the North-American sections suffered a tectonic uplift

Tectonic uplift is the geologic uplift of Earth's surface that is attributed to plate tectonics. While isostatic response is important, an increase in the mean elevation of a region can only occur in response to tectonic processes of crustal thick ...

. It is unclear what causes this and several hypotheses have been presented. One of the theories is the influence of the Iceland hotspot

The Iceland hotspot is a hotspot which is partly responsible for the high volcanic activity which has formed the Iceland Plateau and the island of Iceland.

Iceland is one of the most active volcanic regions in the world, with eruptions occur ...

which could have raised the crust. Another hypothesis is the isostasy

Isostasy (Greek ''ísos'' "equal", ''stásis'' "standstill") or isostatic equilibrium is the state of gravitational equilibrium between Earth's crust (or lithosphere) and mantle such that the crust "floats" at an elevation that depends on its ...

related to glaciations

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betwe ...

caused the uplift. In any of those cases, the uplift allowed the ancient mountain chain to rise several thousand metres.

The area of the national park, and the eastern Sarek Mountains in particular, was the last of part of Fennoscandia

__NOTOC__

Fennoscandia (Finnish language, Finnish, Swedish language, Swedish and no, Fennoskandia, nocat=1; russian: Фенноскандия, Fennoskandiya) or the Fennoscandian Peninsula is the geographical peninsula in Europe, which includes ...

to be deglaciated. The last remnants of the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet

The Weichselian glaciation was the last glacial period and its associated glaciation in northern parts of Europe. In the Alpine region it corresponds to the Würm glaciation. It was characterized by a large ice sheet (the Fenno-Scandian ice sheet) ...

melted there slightly after 9,700 years BP.

Erosion

The mountain chain was renewed and after that it was subjected to a new period of glacial erosion. In the beginning of the

The mountain chain was renewed and after that it was subjected to a new period of glacial erosion. In the beginning of the Quaternary

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million years ...

period, 15 million years ago, a significant glacial advance occurred. The glaciers began to grow and move into the valleys where they gradually merged to form an ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are in Antarctica and Greenland; during the Last Glacial Period at Las ...

that covered the entire region. Several further glaciations followed, forming the current landscape, with glacial valleys, cirque

A (; from the Latin word ') is an amphitheatre-like valley formed by glacial erosion. Alternative names for this landform are corrie (from Scottish Gaelic , meaning a pot or cauldron) and (; ). A cirque may also be a similarly shaped landform ...

s, nunatak

A nunatak (from Inuit ''nunataq'') is the summit or ridge of a mountain that protrudes from an ice field or glacier that otherwise covers most of the mountain or ridge. They are also called glacial islands. Examples are natural pyramidal peaks. ...

s etc.

The degree to which the chain was affected by the erosion depended mainly on the structure of the terrain, which explains the diversity in the topography of the area. The topography of Sarek, similar to that of Kebnekaise, is divided into sharply defined zones, particularly in respect to the two neighbouring national parks. This is mainly due to the existence of diabase

Diabase (), also called dolerite () or microgabbro,

is a mafic, holocrystalline, subvolcanic rock equivalent to volcanic basalt or plutonic gabbro. Diabase dikes and sills are typically shallow intrusive bodies and often exhibit fine-graine ...

and diorite

Diorite ( ) is an intrusive igneous rock formed by the slow cooling underground of magma (molten rock) that has a moderate content of silica and a relatively low content of alkali metals. It is intermediate in composition between low-silic ...

dikes

Dyke (UK) or dike (US) may refer to:

General uses

* Dyke (slang), a slang word meaning "lesbian"

* Dike (geology), a subvertical sheet-like intrusion of magma or sediment

* Dike (mythology), ''Dikē'', the Greek goddess of moral justice

* Dikes ...

which are more resistant to erosion. The park is intersected by a tangle of dikes created 608 million years ago, an era that probably corresponds with the first appearance of the rift during the formation of the Iapetus ocean. These dikes represent intrusions into the Sarektjåkkå nappe

In geology, a nappe or thrust sheet is a large sheetlike body of rock (geology), rock that has been moved more than or above a thrust fault from its original position. Nappes form in compressional tectonic settings like continental collision z ...

, which is composed of sediments probably deposited in the rift basin.

Glaciers

The park has over 100 glaciers, making it one of the most glacier-rich areas in Sweden. The glaciers are relatively small, the largest being Pårtejekna in Pårte at . However, some of the others are relatively large for Sweden, since the largest Swedish glacier, Stuorrajekna in Sulitelma (south of Padjelanta), measures .

The evolution of the glaciers, particularly that of the Mikka () have been studied since the end of the 19th century, especially by mineralogist and geographer

The park has over 100 glaciers, making it one of the most glacier-rich areas in Sweden. The glaciers are relatively small, the largest being Pårtejekna in Pårte at . However, some of the others are relatively large for Sweden, since the largest Swedish glacier, Stuorrajekna in Sulitelma (south of Padjelanta), measures .

The evolution of the glaciers, particularly that of the Mikka () have been studied since the end of the 19th century, especially by mineralogist and geographer Axel Hamberg

Axel Hamberg (17 January 1863 – 28 June 1933) was a Swedish mineralogist, geographer and explorer. Biography

Hamberg was born in Stockholm, Sweden.

He was the son of Nils Peter Hamberg (1815-1902) and Emma Augusta Christina Härnström (18 ...

. The other glaciers in the park have an evolution similar to that of the Mikka: in 1883 to 1895 they were mostly receding, then advanced a little in 1900 to 1916, after which they started to recede again. Later they stabilised or grew, which was interpreted as being caused by the increase in winter precipitation related to global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

. The effect of the raised summer temperatures has been taken into account when assessing the data. The receding of the glaciers has resumed at a particularly rapid pace during the first years of the 21st century.

Wildlife

According to its WWF classification, Sarek National Park is situated in theScandinavian Montane Birch forest and grasslands

The Scandinavian montane birch forests and grasslands is defined by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) as a terrestrial tundra ecoregion in Norway, Sweden, and Finland.

Conservation value

The Scandinavian montane birch forests and grasslands is on ...

ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) or ecozone (ecological zone) is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a bioregion, which in turn is smaller than a biogeographic realm. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas of l ...

, with a minor section in the Scandinavian and Russian taiga

The Scandinavian and Russian taiga is an ecoregion within the taiga and boreal forests biome as defined by the WWF classification (ecoregion PA0608). It is situated in Northern Europe between tundra in the north and temperate mixed forests in ...

. With regards to the flora and fauna, Sarek does not have a wide variety of species. This is mainly explained by the fact that most of the park, except the south and south-east part, is above the growth-limit of conifers, which is at an altitude of about in this region. Adding to this, unlike most of the region, Sarek National Park has few vast lakes or swamp

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

s. A total of approximately 380 species of vascular plant

Vascular plants (), also called tracheophytes () or collectively Tracheophyta (), form a large group of land plants ( accepted known species) that have lignified tissues (the xylem) for conducting water and minerals throughout the plant. They al ...

s have been found in the park, as well as 182 species of vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

s, 24 mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s, 142 bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

s, 2 reptile

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates (lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalians ( ...

s, 2 amphibian

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

s and 12 fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

. Many of these species are on the Swedish red list

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biologi ...

of endangered species

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inv ...

, notably the large carnivores.

The vegetation follows a fairly strict altitudinal zonation

Altitudinal zonation (or elevational zonation) in mountainous regions describes the natural layering of ecosystems that occurs at distinct elevations due to varying environmental conditions. Temperature, humidity, soil composition, and solar radi ...

, as a result of the climate, and implying a similar zonation of fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zoo ...

, although this is often less strict.

Montane zone

The montane zones are relatively rare in the park, as its upper limit is about below most altitudes in these northernlatitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

s. The flora of this zone is constituted by old-growth forest

An old-growth forestalso termed primary forest, virgin forest, late seral forest, primeval forest, or first-growth forestis a forest that has attained great age without significant disturbance, and thereby exhibits unique ecological featur ...

s of conifers, with mainly Scots pine

''Pinus sylvestris'', the Scots pine (UK), Scotch pine (US) or Baltic pine, is a species of tree in the pine family Pinaceae that is native to Eurasia. It can readily be identified by its combination of fairly short, blue-green leaves and orang ...

s and including Norway spruces. The pines can become very tall, particularly those around Lake Rittak, in the south part of the park. The undergrowth is mostly covered with moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) '' sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and hor ...

es and lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship.reindeer lichen

''Cladonia rangiferina'', also known as reindeer cup lichen, reindeer lichen (cf. Sw. ''renlav'') or grey reindeer lichen, is a light-colored fruticose, cup lichen species in the family Cladoniaceae. It grows in both hot and cold climates in we ...

, and also with ''Vaccinium myrtillus

''Vaccinium myrtillus'' or European blueberry is a holarctic species of shrub with edible fruit of blue color, known by the common names bilberry, blaeberry, wimberry, and whortleberry. It is more precisely called common bilberry or blue whortle ...

'', ''Empetrum nigrum

''Empetrum nigrum'', crowberry, black crowberry, or, in western Alaska, blackberry, is a flowering plant species in the heather family Ericaceae with a near circumboreal distribution in the Northern Hemisphere. It is usually dioecious, but there ...

'' and cowberry.

The Sarek forests are a preferred habitat for numerous species of animals. Among the large carnivores, the brown bear

The brown bear (''Ursus arctos'') is a large bear species found across Eurasia and North America. In North America, the populations of brown bears are called grizzly bears, while the subspecies that inhabits the Kodiak Islands of Alaska is kno ...

is particularly frequent in the park and in the neighbouring Stora Sjöfallet. The bear fairly often also ventures into the subalpine region. The Eurasian lynx

The Eurasian lynx (''Lynx lynx'') is a medium-sized wild cat widely distributed from Northern, Central and Eastern Europe to Central Asia and Siberia, the Tibetan Plateau and the Himalayas. It inhabits temperate and boreal forests up to an eleva ...

, classed as an endangered species in Sweden, is also found around the lakes of Rittak and Laitaure, and is also found in the subalpine forests of Rapa Valley. The red fox

The red fox (''Vulpes vulpes'') is the largest of the true foxes and one of the most widely distributed members of the Order (biology), order Carnivora, being present across the entire Northern Hemisphere including most of North America, Europe ...

is relatively frequent, and is gradually extending its territory into the higher zones, where it competes with the arctic fox

The Arctic fox (''Vulpes lagopus''), also known as the white fox, polar fox, or snow fox, is a small fox native to the Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere and common throughout the Arctic tundra biome. It is well adapted to living in co ...

. Some small mammals that are frequent in the park are the European pine marten

The European pine marten (''Martes martes''), also known as the pine marten, is a mustelid native to and widespread in most of Europe, Asia Minor, the Caucasus and parts of Iran, Iraq and Syria. It is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List ...

, the least weasel

The least weasel (''Mustela nivalis''), little weasel, common weasel, or simply weasel is the smallest member of the genus '' Mustela,'' family Mustelidae and order Carnivora. It is native to Eurasia, North America and North Africa, and has bee ...

and the stoat

The stoat (''Mustela erminea''), also known as the Eurasian ermine, Beringian ermine and ermine, is a mustelid native to Eurasia and the northern portions of North America. Because of its wide circumpolar distribution, it is listed as Least Conc ...

. The ermine is also found in the higher regions. The herbivores include a very large number of moose

The moose (in North America) or elk (in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is a member of the New World deer subfamily and is the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is the largest and heaviest extant species in the deer family. Most adult mal ...

as the forests and humid zones provide them with much food. They often grow to an impressive size in the park, with enormous antler

Antlers are extensions of an animal's skull found in members of the Cervidae (deer) family. Antlers are a single structure composed of bone, cartilage, fibrous tissue, skin, nerves, and blood vessels. They are generally found only on male ...

s.

The birds in Sarek include a number of owl

Owls are birds from the order Strigiformes (), which includes over 200 species of mostly solitary and nocturnal birds of prey typified by an upright stance, a large, broad head, binocular vision, binaural hearing, sharp talons, and feathers a ...

s, such as the Ural owl, and woodpecker

Woodpeckers are part of the bird family Picidae, which also includes the piculets, wrynecks, and sapsuckers. Members of this family are found worldwide, except for Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, Madagascar, and the extreme polar regions. ...

s, particularly the Eurasian three-toed woodpecker

The Eurasian three-toed woodpecker (''Picoides tridactylus'') is a medium-sized woodpecker that is found from northern Europe across northern Asia to Japan.

Taxonomy

The Eurasian three-toed woodpecker was formally described in 1758 by the Swedi ...

. The grey-headed chickadee

The grey-headed chickadee or Siberian tit (''Poecile cinctus''), formerly ''Parus cinctus'', is a passerine bird in the tit family Paridae. It is a widespread resident breeder throughout subarctic Scandinavia and the northern Palearctic, and al ...

is also very common, as are the fieldfare

The fieldfare (''Turdus pilaris'') is a member of the thrush family Turdidae. It breeds in woodland and scrub in northern Europe and across the Palearctic. It is strongly migratory, with many northern birds moving south during the winter. It i ...

, the song thrush

The song thrush (''Turdus philomelos'') is a Thrush (bird), thrush that breeds across the West Palearctic. It has brown upper-parts and black-spotted cream or buff underparts and has three recognised subspecies. Its distinctive Birdsong, song, ...

and the redwing

The redwing (''Turdus iliacus'') is a bird in the thrush family, Turdidae, native to Europe and the Palearctic, slightly smaller than the related song thrush.

Taxonomy and systematics

This species was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his ...

. Reptiles and amphibians, such as the viviparous lizard

The viviparous lizard, or common lizard, (''Zootoca vivipara'', formerly ''Lacerta vivipara''), is a Eurasian lizard. It lives farther north than any other species of non-marine reptile, and is named for the fact that it is viviparous, meaning i ...

, the common frog

The common frog or grass frog (''Rana temporaria''), also known as the European common frog, European common brown frog, European grass frog, European Holarctic true frog, European pond frog or European brown frog, is a semi-aquatic amphibian o ...

and the common European viper, are mostly found in the forests. The vipers of the Rittak region frequently reach remarkable sizes.

Subalpine zone

The

The subalpine zone

Montane ecosystems are found on the slopes of mountains. The alpine climate in these regions strongly affects the ecosystem because temperatures fall as elevation increases, causing the ecosystem to stratify. This stratification is a crucial f ...

mostly consists of old-growth birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech-oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 30 ...

forests. These forests are exceptional in terms of density and richness, making it possible for significant quantities of sediment material to be carried from the mountainside by the runoff and deposited in the watercourses. This kind of transfer is particularly noted in the Rapa Valley. In general, the transition between the conifer forests and the ones consisting of birch is more or less gradual, with the number of birches present in the coniferous forests increasing along with the altitude until the conifers have completely disappeared. The size of the trees also diminishes with increasing altitude. The upper altitude limit for the forests — which is also the tree line

The tree line is the edge of the habitat at which trees are capable of growing. It is found at high elevations and high latitudes. Beyond the tree line, trees cannot tolerate the environmental conditions (usually cold temperatures, extreme snowp ...

varies greatly throughout the park, from in the Tjoulta valley to over in the Rapa Valley.

The birch forests also contain other species of trees. The number of rowan

The rowans ( or ) or mountain-ashes are shrubs or trees in the genus ''Sorbus

''Sorbus'' is a genus of over 100 species of trees and shrubs in the rose family, Rosaceae. Species of ''Sorbus'' (''s.l.'') are commonly known as whitebeam, r ...

, grey alder

''Alnus incana'', the grey alder or speckled alder, is a species of multi-stemmed, shrubby tree in the birch family, with a wide range across the cooler parts of the Northern Hemisphere. Tolerant of wetter soils, it can slowly spread with runners ...

, trembling poplar and hackberry is relatively high. The alpine blue-sow-thistle

''Cicerbita alpina'', commonly known as the alpine sow-thistle or alpine blue-sow-thistle is a perennial herbaceous species of plant sometimes placed in the genus '' Cicerbita'' of the family Asteraceae, and sometimes placed in the genus ''Lactu ...

is very widespread in this zone and is the food the bears prefer. Garden angelica

''Angelica archangelica'', commonly known as garden angelica, wild celery, and Norwegian angelica, is a biennial plant from the family Apiaceae, a subspecies of which is cultivated for its sweetly scented edible stems and roots. Like several oth ...

also grows in the forests, reaching a height of . Many other plants in this zone can also attain exceptional size.

The division between the birch and coniferous forests is relatively blurred, with many of the animal species listed above also present in the subalpine zone. Some small mammals are found more frequently here than in the coniferous forests, particularly several rodents such as the

The division between the birch and coniferous forests is relatively blurred, with many of the animal species listed above also present in the subalpine zone. Some small mammals are found more frequently here than in the coniferous forests, particularly several rodents such as the common shrew

The common shrew (''Sorex araneus''), also known as the Eurasian shrew, is the most common shrew, and one of the most common mammals, throughout Northern Europe, including Great Britain, but excluding Ireland. It is long and weighs , and has ve ...

and the field vole

The short-tailed field vole, short-tailed vole, or simply field vole (''Microtus agrestis'') is a grey-brown vole, around 10 cm in length, with a short tail. It is one of the most common mammals in Europe, with a range extending from the Atl ...

. This is also the reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

s' habitat. The Sami people

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise net ...

living within the borders of the park, have domesticated the reindeer that stay in this zone during spring and move up to the alpine zone in summer. Brown bears are common in the valleys of Tjoulta and Rapadalen. However, it is the quantity and variety of birds is that enriches this zone. The willow warbler

The willow warbler (''Phylloscopus trochilus'') is a very common and widespread leaf warbler which breeds throughout northern and temperate Europe and the Palearctic, from Ireland east to the Anadyr River basin in eastern Siberia. It is strongly ...

, the common redpoll

The common redpoll or mealy redpoll (''Acanthis flammea'') is a species of bird in the finch family. It breeds somewhat further south than the Arctic redpoll, also in habitats with thickets or shrubs.

Taxonomy

The common redpoll was listed in 1 ...

, the brambling

The brambling (''Fringilla montifringilla'') is a small passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae. It has also been called the cock o' the north and the mountain finch. It is widespread and migratory, often seen in very large flocks.

Ta ...

, the yellow wagtail, the northern wheatear

The northern wheatear or wheatear (''Oenanthe oenanthe'') is a small passerine bird that was formerly classed as a member of the thrush family Turdidae, but is now more generally considered to be an Old World flycatcher, Muscicapidae. It is the ...

and the bluethroat

The bluethroat (''Luscinia svecica'') is a small passerine bird that was formerly classed as a member of the thrush family Turdidae, but is now more generally considered to be an Old World flycatcher, Muscicapidae. It, and similar small Europea ...

are characteristic of the birch forests. The willow ptarmigan

The willow ptarmigan () (''Lagopus lagopus'') is a bird in the grouse subfamily Tetraoninae of the pheasant family Phasianidae. It is also known as the willow grouse and in Ireland and Britain, where the subspecies '' L. l. scotica'' was prev ...

is also more common in this area. The raptors present in the zone are the merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

and the rough-legged buzzard

The rough-legged buzzard or rough-legged hawk (''Buteo lagopus'') is a medium-large bird of prey. It is found in Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America, Europe, and Russia during the breeding season and migrates south for the winter. It ...

, which often nests on the cliffs. The gyrfalcon

The gyrfalcon ( or ) (), the largest of the falcon species, is a bird of prey. The abbreviation gyr is also used. It breeds on Arctic coasts and tundra, and the islands of northern North America and the Eurosiberian region. It is mainly a reside ...

and the golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known bird of p ...

usually prefer lower altitudes, but are nevertheless also found in the park.

Alpine zone

The

The alpine zone

Alpine tundra is a type of natural region or biome that does not contain trees because it is at high elevation, with an associated harsh climate. As the latitude of a location approaches the poles, the threshold elevation for alpine tundra gets ...

is divided into several narrower zones. The first subzone is mostly characterized by heath

A heath () is a shrubland habitat found mainly on free-draining infertile, acidic soils and characterised by open, low-growing woody vegetation. Moorland is generally related to high-ground heaths with—especially in Great Britain—a cooler ...

land, with many alder

Alders are trees comprising the genus ''Alnus'' in the birch family Betulaceae. The genus comprises about 35 species of monoecious trees and shrubs, a few reaching a large size, distributed throughout the north temperate zone with a few sp ...

shrub

A shrub (often also called a bush) is a small-to-medium-sized perennial woody plant. Unlike herbaceous plants, shrubs have persistent woody stems above the ground. Shrubs can be either deciduous or evergreen. They are distinguished from trees ...

s, mosses and lichens, and frequently dense mats of crowberries. Different types of heaths can be distinguished. One type is mostly composed of a mix of alpine clubmoss

''Diphasiastrum alpinum'', the alpine clubmoss, is a species of clubmoss. It was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his Flora Lapponica, 1737, from specimens obtained in Finland.

Distribution

It has a circumpolar distribution across much of the ...

and alpine bearberry. Cushion pink and Lapland lousewort bring autumn colour to the heaths, which are otherwise fairly monochrome. In the chalky soils of this subzone, the vegetation is very rich and forms prairie

Prairies are ecosystems considered part of the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome by ecologists, based on similar temperate climates, moderate rainfall, and a composition of grasses, herbs, and shrubs, rather than trees, as the ...

s with mountain avens

''Dryas octopetala'', the mountain avens, eightpetal mountain-avens, white dryas or white dryad, is an Arctic–alpine flowering plant in the family Rosaceae. It is a small prostrate evergreen subshrub forming large colonies. The specific epit ...

as the most characteristic species. purple saxifrage

''Saxifraga oppositifolia'', the purple saxifrage or purple mountain saxifrage, is a species of plant that is very common in the high Arctic and also some high mountainous areas further south, including northern Britain, the Alps and the Rocky ...

, velvetbells, alpine pussytoes and alpine veronica Alpine veronica is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

*''Veronica alpina'', native to Europe and Asia

*''Veronica wormskjoldii

''Veronica wormskjoldii'' is a species of flowering plant in the plantain family known by the common ...

are also present. With increasing altitude, the dwarf willow

''Salix herbacea'', the dwarf willow, least willow or snowbed willow, is a species of tiny creeping willow (family Salicaceae) adapted to survive in harsh arctic and subarctic environments. Distributed widely in alpine and arctic environments ar ...

and lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship.wolverine

The wolverine (), (''Gulo gulo''; ''Gulo'' is Latin for "gluttony, glutton"), also referred to as the glutton, carcajou, or quickhatch (from East Cree, ''kwiihkwahaacheew''), is the largest land-dwelling species of the family Mustelidae. It is ...

inhabits a vast territory, roaming as far as the coniferous forests in winter, but the alpine zone is their main territory. They mostly eat carrion

Carrion () is the decaying flesh of dead animals, including human flesh.

Overview

Carrion is an important food source for large carnivores and omnivores in most ecosystems. Examples of carrion-eaters (or scavengers) include crows, vultures, c ...

, but they do also hunt living animals such as small rodents, birds and insects. The wolverine is labelled as an endangered species in Sweden with an estimate of 360 individuals in the country in 2000. The Arctic fox is a critically endangered species in Sweden, with only 50 individuals in the whole country. They dig extensive networks of tunnels in areas above the tree-line, with several families inhabiting the same sett

A sett or set is a badger's den. It usually consists of a network of tunnels and numerous entrances. The largest setts are spacious enough to accommodate 15 or more animals with up to of tunnels and as many as 40 openings. Such elaborate setts ...

. The park is one of the last sanctuaries for the gray wolf

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, and gray wolves, as popularly ...

, a species also critically endangered in Sweden. In 1974–1975, the park was home to the only remaining wild wolf living in Sweden. Although the wolf population is now growing, they have not yet achieved a stable number in the park.

In addition to these three mammals, Norway lemming

The Norway lemming, also known as the Norwegian lemming (''Lemmus lemmus'') is a common species of lemming found in northern Fennoscandia, where it is the only vertebrate species endemic to the region. The Norway lemming dwells in tundra and fell ...

s are also found in the park. The number of lemmings varies extremely, with massive spikes in the population during some years, immediately followed by a very rapid decline. This phenomenon is not completely understood; it appears that favourable weather, and therefore a surplus of food, results in sudden population growths, but the reason for the decline is less obvious, although it is certain that contagious diseases play some role. These cycles are also reflected in the populations of animals who prey on the lemmings.

Many birds living at this altitude are associated with the humid zones. However, the alpine zone has its own characteristic species, such as the rock ptarmigan

The rock ptarmigan (''Lagopus muta'') is a medium-sized game bird in the grouse family. It is known simply as the ptarmigan in the UK. It is the official bird for the Canadian territory of Nunavut, where it is known as the ''aqiggiq'' (ᐊᕿ� ...

, the snowy owl

The snowy owl (''Bubo scandiacus''), also known as the polar owl, the white owl and the Arctic owl, is a large, white owl of the true owl family. Snowy owls are native to the Arctic regions of both North America and the Palearctic, breeding mos ...

, the horned lark

The horned lark or shore lark (''Eremophila alpestris'') is a species of lark in the family Alaudidae found across the northern hemisphere. It is known as "horned lark" in North America and "shore lark" in Europe.

Taxonomy, evolution and systema ...

, the meadow pipit

The meadow pipit (''Anthus pratensis'') is a small passerine bird, which breeds in much of the Palearctic, from southeastern Greenland and Iceland east to just east of the Ural Mountains in Russia, and south to central France and Romania; an isol ...

, the snow bunting

The snow bunting (''Plectrophenax nivalis'') is a passerine bird in the family Calcariidae. It is an Arctic specialist, with a circumpolar Arctic breeding range throughout the northern hemisphere. There are small isolated populations on a few hig ...

and the Lapland longspur

The Lapland longspur (''Calcarius lapponicus''), also known as the Lapland bunting, is a passerine bird in the longspur family Calcariidae, a group separated by most modern authors from the Fringillidae (Old World finches).

Etymology

The English ...

.

Humid zone

Although the park does not have the vast marshes and lakes characteristic of the rest of the region, water is nevertheless present everywhere. The humid zones are rich with a great diversity of flora and fauna. The stratification of vegetation is just as valid in the humid zones. In the montane region, the humid soils are covered with flowers such as the northern Labrador tea, cottonsedge, the

Although the park does not have the vast marshes and lakes characteristic of the rest of the region, water is nevertheless present everywhere. The humid zones are rich with a great diversity of flora and fauna. The stratification of vegetation is just as valid in the humid zones. In the montane region, the humid soils are covered with flowers such as the northern Labrador tea, cottonsedge, the Goldilocks buttercup

''Ranunculus auricomus'', known as goldilocks buttercup or Greenland buttercup, is a perennial species of buttercup native to Eurasia. It is a calcicole typically found in moist woods and at the margins of woods. It is Apomixis, apomictic, and se ...

, St Olaf's candlestick, common selfheal and common marsh-bedstraw

''Galium palustre'', the common marsh bedstraw or simply marsh-bedstraw, is a herbaceous annual plant of the family Rubiaceae. This plant is widely distributed, native to virtually every country in Europe, plus Morocco, the Azores, Turkey, Turkm ...

. In the subalpine zone, the humid prairies mainly have mats of Globe-flower, kingcup

''Caltha palustris'', known as marsh-marigold and kingcup, is a small to medium size perennial herbaceous flowering plant, plant of the buttercup family, native plant, native to marshes, fens, ditches and wet woodland in temperate regions of the ...

and twoflower violet. In the alpine region there are many subalpine plants as well as the ''Pedicularis sceptrum-carolinum

''Pedicularis sceptrum-carolinum'', commonly known as moor-king or moor-king lousewort, is a plant species in the genus ''Pedicularis

''Pedicularis'' is a genus of perennial green root parasite plants currently placed in the family Orobancha ...

'', and the vegetation decreases as the altitude increases.

The humid zones of the park are well known for their rich diversity of birds. The common crane

The common crane (''Grus grus''), also known as the Eurasian crane, is a bird of the family Gruidae, the cranes. A medium-sized species, it is the only crane commonly found in Europe besides the demoiselle crane (''Grus virgo'') and the Siberi ...

, the wood sandpiper

The wood sandpiper (''Tringa glareola'') is a small wader. This Eurasian species is the smallest of the shanks, which are mid-sized long-legged waders of the family Scolopacidae. The genus name ''Tringa'' is the New Latin name given to the gree ...

and the short-eared owl

The short-eared owl (''Asio flammeus'') is a widespread grassland species in the family Strigidae. Owls belonging to genus ''Asio'' are known as the eared owls, as they have tufts of feathers resembling mammalian ears. These "ear" tufts may or ...

are found at the lower altitudes, while the Eurasian teal

The Eurasian teal (''Anas crecca''), common teal, or Eurasian green-winged teal is a common and widespread duck that breeds in temperate Eurosiberia and migrates south in winter. The Eurasian teal is often called simply the teal due to being th ...

, the Eurasian wigeon

The Eurasian wigeon or European wigeon (''Mareca penelope''), also known as the widgeon or the wigeon, is one of three species of wigeon in the dabbling duck genus ''Mareca''. It is common and widespread within its Palearctic range.

Taxonomy

Th ...

, the greater scaup

The greater scaup (''Aythya marila''), just scaup in Europe or, colloquially, "bluebill" in North America, is a mid-sized diving duck, larger than the closely related lesser scaup. It spends the summer months breeding in Alaska, northern Canada, ...

, the red-breasted merganser

The red-breasted merganser (''Mergus serrator'') is a diving duck, one of the sawbills. The genus name is a Latin word used by Pliny and other Roman authors to refer to an unspecified waterbird, and ''serrator'' is a sawyer from Latin ''serra'', ...

, the sedge warbler

The sedge warbler (''Acrocephalus schoenobaenus'') is an Old World warbler in the genus '' Acrocephalus''. It is a medium-sized warbler with a brown, streaked back and wings and a distinct pale supercilium. Sedge warblers are migratory, crossing ...

and the common reed bunting

The common reed bunting (''Emberiza schoeniclus'') is a passerine bird in the bunting family Emberizidae, a group now separated by most modern authors from the finches, Fringillidae. The genus name ''Emberiza'' is from Old German ''Embritz'', a ...

are common in the Laitaure delta and around Pårekjaure Lake.

At higher altitudes, Vardojaure Lake is rich with birds, mostly ducks and also the European golden plover

The European golden plover (''Pluvialis apricaria''), also known as the European golden-plover, Eurasian golden plover, or just the golden plover within Europe, is a largish plover. This species is similar to two other golden plovers: the America ...

, characteristic of the alpine zone and sometimes found in the humid zones. Låotakjaure Lake, on the border of Padjelanta, is interesting from an ornithological point of view. Other rare species are also present, such as the lesser white-fronted goose

The lesser white-fronted goose (''Anser erythropus'') is a goose closely related to the larger white-fronted goose (''A. albifrons''). It breeds in the northernmost Palearctic, but it is a scarce breeder in Europe. There is a re-introduction sche ...

, the great snipe

The great snipe (''Gallinago media'') is a small stocky wader in the genus ''Gallinago''. This bird's breeding habitat is marshes and wet meadows with short vegetation in north-eastern Europe, including north-western Russia. Great snipes are mig ...

, the red-throated pipit

The red-throated pipit (''Anthus cervinus'') is a small passerine bird,which breeds in the far north of Europe and the Palearctic, with a foothold in northern Alaska. It is a long-distance migrant, moving in winter to Africa, South and East Asia ...

, the long-tailed duck

The long-tailed duck (''Clangula hyemalis''), formerly known as oldsquaw, is a medium-sized sea duck that breeds in the tundra and taiga regions of the arctic and winters along the northern coastlines of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It is th ...

and the bar-tailed godwit

The bar-tailed godwit (''Limosa lapponica'') is a large and strongly migratory wader in the family Scolopacidae, which feeds on bristle-worms and shellfish on coastal mudflats and estuaries. It has distinctive red breeding plumage, long legs, an ...

. The Luottolako Plateau is also considered to be interesting, with the most significant concentration of purple sandpiper

The purple sandpiper (''Calidris maritima'') is a small shorebird in the sandpiper family Scolopacidae. This is a hardy sandpiper that breeds in the arctic and subarctic regions of Eurasia and North America and winters further south on the Atlant ...

s in Sweden.

Arctic char

The Arctic char or Arctic charr (''Salvelinus alpinus'') is a cold-water fish in the family Salmonidae, native to alpine lakes and arctic and subarctic coastal waters. Its distribution is Circumpolar North. It spawns in freshwater and populatio ...

s, trouts and common minnow

The Eurasian minnow, minnow, or common minnow (''Phoxinus phoxinus'') is a small species of freshwater fish in the carp

family Cyprinidae. It is the type species of genus ''Phoxinus''. It is ubiquitous throughout much of Eurasia, from Britain and ...

s are found in the park's lakes, rivers and streams.

Tourism

Sarek National Park is mainly a high-alpine area with almost no accommodation for tourists.Hiking trails

TheKungsleden

Kungsleden (King's Trail) is a hiking trail in northern Sweden, approximately long, between Abisko in the north and Hemavan in the south. It passes through, near the southern end, the Vindelfjällen Nature Reserve, one of the largest protected ...

hiking trail passes through the eastern part of the park, from Saltoluokta

Saltoluokta () is a 120 kilometer drive outside Gällivare in northern Sweden, off the beaten track in Jokkmokk Municipality near the municipality's border with Gällivare Municipality, Gällivare. Saltoluokta is located less than 1 kil ...

to Kvikkjokk. There are no cabins within the park, the Pårte, Aktse and Sitojaure cabins are just outside the park and they are accessible from both Saltoluokta and Kvikkjokk.

The Padjelanta Trail (''Padjelantaleden''), running from Kvikkjokk to Akkajaure, skirts the park along its western rim at Tarraluoppal, where the Tarraluoppal cabin is just on the border of the park.

Hazards

Due to the lack of shelters combined with rapidly shifting weather and rough terrain, it is recommended that hikers are well prepared and experienced before setting out on the trails of the park.Fording streams

There are few bridges in the park, and crossing streams (Sami: ''jokk'') and rivers (Sami: ''ätno'') can be dangerous for ill-equipped or inexperienced hikers. Warm weather increases the melting of the glaciers causing water levels to rise, therefore wading is often easier and safer early in the morning. The onlyford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

across the Rapa River south of the Smaila Moot, is at Tielmaskaite. The ford is long and can only be used when waterlevels are low. Inexperienced hikers are recommended not to cross without a guide.

The glacier ''jokk'' from Pårtejekna, Kåtokjåhkå, has no fords. There is a bridge at the southernmost part of the stream (). Hikers can also follow the streams up to the glacier and cross there, although this requires knowledge about glacier crossing.

Sarek in the winter

The lack of marked trails and accommodations makes it very difficult for visitors to hike in the park in winter, unless they are experienced and properly equipped. The steep slopes of the valleys also contributes to the risk foravalanche

An avalanche is a rapid flow of snow down a slope, such as a hill or mountain.

Avalanches can be set off spontaneously, by such factors as increased precipitation or snowpack weakening, or by external means such as humans, animals, and earth ...

s.

Places of interest

Aktse

Aktse is an old farm settlement on the Kungsleden trail, approximately outside the boundaries of the park.Alkavare

In 1788 a chapel was built at Alkavare () for the Sami that were herding reindeer in the area during summer. The walls of the building were dry set from local stone and the roof was made of timber, transported from Kvikkjokk, away. Originally, service was held every summer on June25. It took the minister from Kvikkjokk three days to reach the chapel, and three days to get back. It was abandoned in the mid-19th century and renovated in 1961, and is still in use. , it belongs to theJokkmokk

Jokkmokk (; smj, Jåhkåmåhkke or ; se, Dálvvadis; fi, Jokimukka) is a locality and the seat of Jokkmokk Municipality in Norrbotten County, province of Lapland, Sweden, with 2,786 inhabitants in 2010. The Lule Sami name of the place (composed ...

parish of the Church of Sweden

The Church of Sweden ( sv, Svenska kyrkan) is an Evangelical Lutheran national church in Sweden. A former state church, headquartered in Uppsala, with around 5.6 million members at year end 2021, it is the largest Christian denomination in Sw ...

, and church service is held throughout July.

The Smaila Moot

Just above the canyon, formed by Smailajåkk as it descends toward Rapaätno, there is a cabin for the National Park Service (). There is also a bridge over the Smailajåkk canyon which allows hikers to cross the stream safely. The bridge is removed every winter and put back in the spring, after the spring flood. The cabin is not open to hikers, but there is an emergency shelter as well as an emergency telephone and an outhouse there. The presence of the bridge and the fact that three of the major valleys in the park (''Routesvagge'', Rapa Valley and ''Koupervagge'') converge there, has resulted in the name 'Smaila Moot' for the location which has become a meeting place for hikers in the park. It is also a preferred location to start a climb to the top of the Sarektjåkkå (), via the Mikkajekna glacier.Pastavagge

Pastavagge (inLule Sami Lule may refer to:

* Lule people, an indigenous people of northern Argentina

* Lule language, a possibly extinct language of Argentina

* Lule Sami language, a language spoken in Sweden and Norway

* Luleå, also known as Lule, a town in Sweden

* Lul ...

Orthography

An orthography is a set of conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, hyphenation, capitalization, word breaks, emphasis, and punctuation.

Most transnational languages in the modern period have a writing system, and mos ...

called ''Basstavágge'') is a narrow valley, forming a pass, running from Pielavalta (''Bielavallda'') towards the east, ending north of Rinim on the shores of Lake Sitojaure (''Sijddojávrre''). The trekking distance from Pielvalta to Rinim is about . As there is a boat connection between Rinim and the Sitojaure cabins on the Kungsleden, Pastavagge is a preferred route to and from central Sarek. The difference in altitude between the eastern entrance of the valley and the highest level of the pass is about . Because of the steep climb, multiple fords and the high-alpine terrain, it usually takes at least a full day for hikers to traverse the pass.

History

The Sami people

The region's first inhabitants arrived with the retreat of the inland seas 8,000 years ago. They were

The region's first inhabitants arrived with the retreat of the inland seas 8,000 years ago. They were nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the popu ...

s who lived in Northern Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

, and probably ancestors of the Samis. Initially they were hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

s, living off reindeer. For those people, the mountains often had religious connotations, and several were ''Sieidi'' (places of worship). Offerings, such as antler

Antlers are extensions of an animal's skull found in members of the Cervidae (deer) family. Antlers are a single structure composed of bone, cartilage, fibrous tissue, skin, nerves, and blood vessels. They are generally found only on male ...

s from reindeer, were often made in those places. One of the most significant ''Sieidi'' was situated at the foot of Mount Skierfe ( high), at the entrance to the Rapa Valley. Samis from the entire region gathered in this place for ceremonies. Mount Apär itself, was believed to be the home of demons and legend tells of an illegitimate child's ghost inside it.

Despite their hunter-gatherer way of life, the Samis kept some domesticated reindeer. They were milked and used for transport as well as other things. Towards the end of the 17th century, the number of domesticated reindeer increased, and the Samis began to harmonize their travelling with the reindeer's search for pasture. Eventually, hunting the reindeer gave way to farming

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

them. The Samis in the mountains gradually developed a system of transhumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and lower vall ...