SMS Preussen (1903) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS ''Preussen''). was the fourth of five

The fleet conducted training exercises in the Baltic in February 1908. Prince Heinrich, then the commander of the High Seas Fleet, had pressed for such a cruise the previous year, arguing that it would prepare the fleet for overseas operations and would break up the monotony of training in German waters, though tensions with Britain over the developing

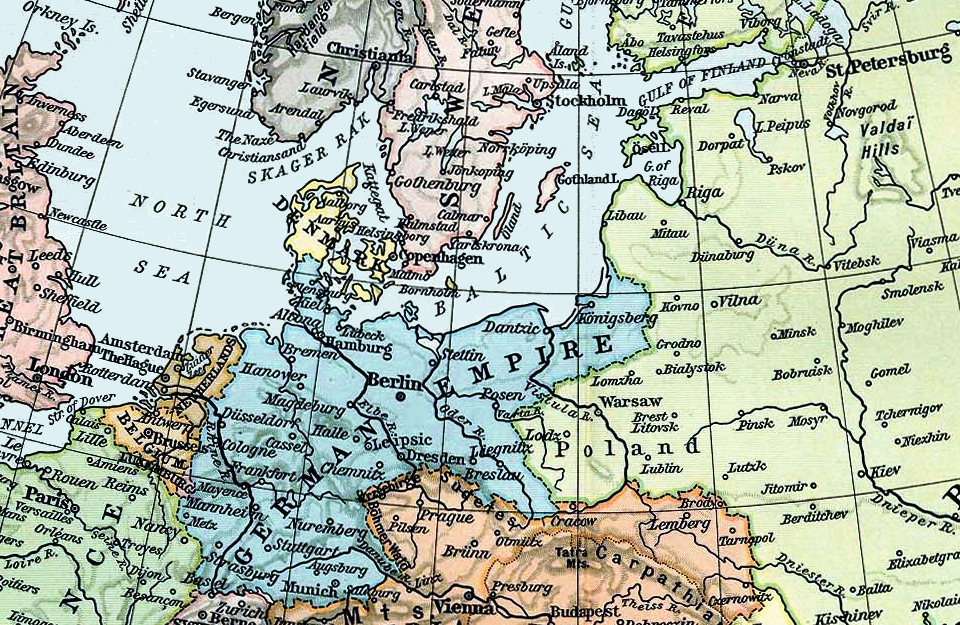

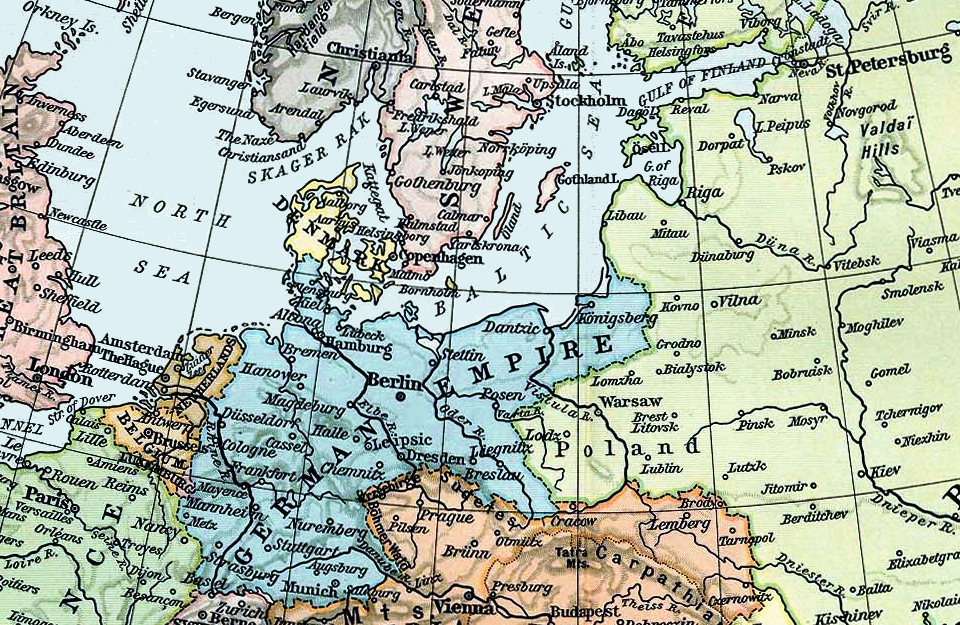

The fleet conducted training exercises in the Baltic in February 1908. Prince Heinrich, then the commander of the High Seas Fleet, had pressed for such a cruise the previous year, arguing that it would prepare the fleet for overseas operations and would break up the monotony of training in German waters, though tensions with Britain over the developing  In May 1910, the fleet conducted training maneuvers in the Kattegat. These were in accordance with Holtzendorff's strategy, which envisioned drawing the Royal Navy into the narrow waters there. The annual summer cruise was to Norway, and was followed by fleet training, during which another fleet review was held in Danzig on 29 August. After the conclusion of the maneuvers, Schröder was promoted to chief of the ''

In May 1910, the fleet conducted training maneuvers in the Kattegat. These were in accordance with Holtzendorff's strategy, which envisioned drawing the Royal Navy into the narrow waters there. The annual summer cruise was to Norway, and was followed by fleet training, during which another fleet review was held in Danzig on 29 August. After the conclusion of the maneuvers, Schröder was promoted to chief of the ''

After the outbreak of war in August 1914, the German command deployed II Squadron in the

After the outbreak of war in August 1914, the German command deployed II Squadron in the

pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, prote ...

s of the , built for the German ''Kaiserliche Marine

{{italic title

The adjective ''kaiserlich'' means "imperial" and was used in the German-speaking countries to refer to those institutions and establishments over which the ''Kaiser'' ("emperor") had immediate personal power of control.

The term wa ...

'' (Imperial Navy). She was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in April 1902, was launched in October 1903, and was commissioned in July 1905. Named for the state of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, the ship was armed with a battery of four guns and had a top speed of . Like all pre-dreadnoughts built at the turn of the century, ''Preussen'' was quickly made obsolete by the launching of the revolutionary in 1906; as a result, she saw only limited service with the German fleet.

''Preussen''s peacetime career centered on squadron and fleet exercises and training cruises to foreign ports. The ship served as the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of II Battle Squadron

The II Battle Squadron was a unit of the German High Seas Fleet before and during World War I. The squadron saw action throughout the war, including the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916, where it formed the rear of the German line. ...

of the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

for the majority of her career. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, she served as a guard ship

A guard ship is a warship assigned as a stationary guard in a port or harbour, as opposed to a coastal patrol boat, which serves its protective role at sea.

Royal Navy

In the Royal Navy of the eighteenth century, peacetime guard ships were usual ...

in the German Bight

The German Bight (german: Deutsche Bucht; da, tyske bugt; nl, Duitse bocht; fry, Dútske bocht; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and ...

and later in the Danish straits

The Danish straits are the straits connecting the Baltic Sea to the North Sea through the Kattegat and Skagerrak. Historically, the Danish straits were internal waterways of Denmark; however, following territorial losses, Øresund and Fehmarn Be ...

. She participated in a fleet sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warfare. ...

in December 1914 in support of the Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby

The Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby on 16 December 1914 was an attack by the Imperial German Navy on the British ports of Scarborough, Hartlepool, West Hartlepool and Whitby. The bombardments caused hundreds of civilian casualties an ...

during which the German fleet briefly clashed with a detachment of the British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

. ''Preussen'' had been temporarily assigned to guard ship duties in the Baltic in May 1916, and so missed the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy ...

. Due to her age, she did not rejoin the fleet, and instead continued to serve as a guard ship until 1917, when she became a tender for U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s based in Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsha ...

.

After the war, ''Preussen'' was retained by the re-formed ''Reichsmarine

The ''Reichsmarine'' ( en, Realm Navy) was the name of the German Navy during the Weimar Republic and first two years of Nazi Germany. It was the naval branch of the ''Reichswehr'', existing from 1919 to 1935. In 1935, it became known as the ''K ...

'' and converted into a depot ship

A depot ship is an auxiliary ship used as a mobile or fixed base for submarines, destroyers, minesweepers, fast attack craft, landing craft, or other small ships with similarly limited space for maintenance equipment and crew dining, berthing an ...

for F-type minesweeper

A minesweeper is a small warship designed to remove or detonate naval mines. Using various mechanisms intended to counter the threat posed by naval mines, minesweepers keep waterways clear for safe shipping.

History

The earliest known usage of ...

s. She was stricken from the naval register

A Navy Directory, formerly the Navy List or Naval Register is an official list of naval officers, their ranks and seniority, the ships which they command or to which they are appointed, etc., that is published by the government or naval author ...

in April 1929 and sold to ship breakers in 1931. A section of her hull was retained as a target; it was bombed and sunk in 1945 by Allied bombers at the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and was scrapped in 1954.

Design

With the passage of the Second Naval Law under the direction of ''Vizeadmiral

(abbreviated VAdm) is a senior naval flag officer rank in several German-speaking countries, equivalent to Vice admiral.

Austria-Hungary

In the Austro-Hungarian Navy there were the flag-officer ranks ''Kontreadmiral'' (also spelled ''Kont ...

'' (''VAdm''—Vice Admiral) Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916. Prussi ...

in 1900, funding was allocated for a new class of battleships to succeed the ships authorized under the 1898 Naval Law. By this time, Krupp

The Krupp family (see pronunciation), a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, is notable for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition and other armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG (Friedrich Krup ...

, the supplier of naval artillery to the ''Kaiserliche Marine

{{italic title

The adjective ''kaiserlich'' means "imperial" and was used in the German-speaking countries to refer to those institutions and establishments over which the ''Kaiser'' ("emperor") had immediate personal power of control.

The term wa ...

'' (Imperial Navy) had developed quick-firing, guns; the largest guns that had previously incorporated the technology were the guns mounted on the ''Wittelsbach''s. The Design Department of the ''Reichsmarineamt

The Imperial Naval Office (german: Reichsmarineamt) was a government agency of the German Empire. It was established in April 1889, when the German Imperial Admiralty was abolished and its duties divided among three new entities: the Imperial Na ...

'' (Imperial Navy Office) adopted these guns for the new battleships, along with an increase from to for the secondary battery, owing to the increased threat from torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s as torpedoes became more effective.

Though the ''Braunschweig'' class marked a significant improvement over earlier German battleships, its design fell victim to the rapid pace of technological development in the early 1900s. The British battleship —armed with ten 12-inch (30.5 cm) guns—was commissioned in December 1906, less than a year and a half after ''Preussen'' entered service. ''Dreadnought''s revolutionary design rendered every capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

of the German navy obsolete, including ''Preussen''.

''Preussen'' was long overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

and had a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vessel ...

of forward. She displaced as designed and at Full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. Her crew consisted of 35 officers and 708 enlisted men. The ship was powered by three 3-cylinder vertical triple expansion engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be tr ...

s that drove three screws. Steam was provided by eight naval and six cylindrical boilers, all of which burned coal. ''Preussen''s powerplant was rated at , which generated a top speed of . She could steam at a cruising speed of .

''Preussen''s armament consisted of a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of four 28 cm (11 in) SK L/40 guns in twin gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, one fore and one aft of the central superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. Her secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored ...

consisted of fourteen 17 cm (6.7 inch) SK L/40 guns and eighteen 8.8 cm (3.45 in) SK L/35 quick-firing guns. The armament suite was rounded out with six torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, all mounted submerged in the hull. One tube was in the bow, two were on each broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

, and the final tube was in the stern. ''Preussen'' was protected with Krupp armor

Krupp armour was a type of steel naval armour used in the construction of capital ships starting shortly before the end of the nineteenth century. It was developed by Germany's Krupp Arms Works in 1893 and quickly replaced Harvey armour as the p ...

. Her armored belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal vehicle armor, armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from p ...

was thick, the heavier armor in the central citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

that protected her magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

and propulsion machinery spaces, and the thinner plating at either end of the hull. Her deck was thick. The main battery turrets had 250 mm of armor plating.

Service history

Construction through 1907

''Preussen'' waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in April 1902 at the AG Vulcan

Aktien-Gesellschaft Vulcan Stettin (short AG Vulcan Stettin) was a German shipbuilding and locomotive building company. Founded in 1851, it was located near the former eastern German city of Stettin, today Polish Szczecin. Because of the limited ...

shipyard in Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin language, Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital city, capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the Po ...

under construction number 256. The fourth unit of her class, she had been ordered under the contract name "K" as a new unit for the fleet. ''Preussen'' was launched on 30 October 1903, with a speech given by Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Bernhard von Bülow

Bernhard Heinrich Karl Martin, Prince of Bülow (german: Bernhard Heinrich Karl Martin Fürst von Bülow ; 3 May 1849 – 28 October 1929) was a German statesman who served as the foreign minister for three years and then as the chancellor of t ...

and the christening performed by Empress Augusta Victoria

, house = Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg

, father = Frederick VIII, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein

, mother = Princess Adelheid of Hohenlohe-Langenburg

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Dolzig Palace ...

. The ship was commissioned into the fleet on 12 July 1905. Sea trials

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and i ...

lasted until September, when she formally joined II Squadron, where she replaced the battleship as the squadron flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

. ''VAdm'' Max von Fischel was the squadron commander at the time.

The German fleet was occupied with extensive training exercises during the early 1900s. The ships were occupied with individual, division and squadron exercises throughout April 1906, the only interruption being in February, when ''Preussen'' carried Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empir ...

to Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

in company with the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

and the torpedo boats and . Wilhelm II attended the burial of the Danish King Christian IX

Christian IX (8 April 181829 January 1906) was King of Denmark from 1863 until his death in 1906. From 1863 to 1864, he was concurrently Duke of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg.

A younger son of Frederick William, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein ...

, who had died the previous month. Starting on 13 May, major fleet exercises took place in the North Sea and lasted until 8 June with a cruise around the Skagen

Skagen () is Denmark's northernmost town, on the east coast of the Skagen Odde peninsula in the far north of Jutland, part of Frederikshavn Municipality in Nordjylland, north of Frederikshavn and northeast of Aalborg. The Port of Skagen is ...

into the Baltic. During Kiel Week

The Kiel Week (german: Kieler Woche) or Kiel Regatta is an annual sailing event in Kiel, the capital of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is the largest sailing event in Europe, and also one of the largest Volksfeste in Germany, attracting ...

on 21 June, ''Preussen'' received a gift from the provinces of West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

and East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

, in the form of a Prussian war flag. The fleet began its usual summer cruise to Norway in mid-July, and the fleet was present for the birthday of Norwegian King Haakon VII

Haakon VII (; born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick VI ...

on 3 August. The German ships departed the following day for Helgoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

, to join exercises being conducted there.

The fleet was back in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

by 15 August, where preparations for the autumn maneuvers began. On 22–24 August, the fleet took part in landing exercises in Eckernförde Bay

Eckernförde Bay (german: Eckernförder Bucht; da, Egernførde Fjord or Egernfjord) is a firth and a branch of the Bay of Kiel between the Danish Wahld peninsula in the south and the Schwansen peninsula in the north in the Baltic Sea off the lan ...

outside Kiel. The maneuvers were paused from 31 August to 3 September when the fleet hosted vessels from Denmark and Sweden, along with a Russian squadron from 3 to 9 September in Kiel. The maneuvers resumed on 8 September and lasted five more days. The ship participated in the uneventful winter cruise into the Kattegat

The Kattegat (; sv, Kattegatt ) is a sea area bounded by the Jutlandic peninsula in the west, the Danish Straits islands of Denmark and the Baltic Sea to the south and the provinces of Bohuslän, Västergötland, Halland and Skåne in Sweden ...

and Skagerrak

The Skagerrak (, , ) is a strait running between the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, the southeast coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden, connecting the North Sea and the Kattegat sea area through the Danish Straits to the Baltic Sea.

The ...

from 8 to 16 December. The first quarter of 1907 followed the previous pattern and, on 16 February, the Active Battle Fleet was re-designated the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

. From the end of May to early June the fleet went on its summer cruise in the North Sea, returning to the Baltic via the Kattegat. This was followed by the regular cruise to Norway from 12 July to 10 August, after which the fleet conducted the annual autumn maneuvers, which lasted from 26 August to 6 September. The exercises included landing exercises in northern Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

with IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial Germ ...

. On 1 October 1907, ''Konteradmiral

''Konteradmiral'', abbreviated KAdm or KADM, is the second lowest naval flag officer rank in the German Navy. It is equivalent to '' Generalmajor'' in the '' Heer'' and ''Luftwaffe'' or to '' Admiralstabsarzt'' and ''Generalstabsarzt'' in the '' ...

'' (''KAdm''—Rear Admiral) Ludwig von Schröder

Ludwig von Schröder (17 July 1854 Hintzenkamp near Eggesin – 23 July 1933 in Berlin-Halensee) was an Imperial German Navy officer and Admiral during the First World War and a recipient of the ''Pour le Mérite'' with Oak Leaves.

Schröder ent ...

came aboard ''Preussen'', taking command of the squadron, as Fischel had become the chief of the ''Marinestation der Nordsee

The Marinestation der Nordsee (North Sea Naval Station) of the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) at Wilhelmshaven came out of the efforts of the navy of the North German Confederation. The land was obtained for the Confederation from the ...

'' (Naval Station of the North Sea). The winter training cruise went into the Kattegat from 22 to 30 November.

1908–1914

The fleet conducted training exercises in the Baltic in February 1908. Prince Heinrich, then the commander of the High Seas Fleet, had pressed for such a cruise the previous year, arguing that it would prepare the fleet for overseas operations and would break up the monotony of training in German waters, though tensions with Britain over the developing

The fleet conducted training exercises in the Baltic in February 1908. Prince Heinrich, then the commander of the High Seas Fleet, had pressed for such a cruise the previous year, arguing that it would prepare the fleet for overseas operations and would break up the monotony of training in German waters, though tensions with Britain over the developing Anglo-German naval arms race

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany that occurred from the last decade of the nineteenth century until the advent of World War I in 1914 was one of the intertwined causes of that conflict. While based in a bilateral relationship that ...

were high. The fleet departed Kiel on 17 July, passed through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal

The Kiel Canal (german: Nord-Ostsee-Kanal, literally "North- oEast alticSea canal", formerly known as the ) is a long freshwater canal in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The canal was finished in 1895, but later widened, and links the ...

to the North Sea, and continued to the Atlantic. During the cruise, ''Preussen'' visited Las Palmas

Las Palmas (, ; ), officially Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, is a Spain, Spanish city and capital of Gran Canaria, in the Canary Islands, on the Atlantic Ocean.

It is the capital (jointly with Santa Cruz de Tenerife), the most populous city in th ...

in the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

. The fleet returned to Germany on 13 August. The autumn maneuvers followed from 27 August to 12 September. Later that year, the fleet toured coastal German cities as part of an effort to increase public support for naval expenditures.

In early 1909, ''Preussen'' and the battleships and were sent to break paths in the sea ice off the coast of Holstein for merchant shipping. Another cruise into the Atlantic was conducted from 7 July to 1 August, during which ''Preussen'' stopped in El Ferrol

Ferrol () is a city in the Province of A Coruña in Galicia, on the Atlantic coast in north-western Spain, in the vicinity of Strabo's Cape Nerium (modern day Cape Prior). According to the 2021 census, the city has a population of 64,785, mak ...

, Spain. On the way back to Germany, the High Seas Fleet was received by the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

in Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

. Later that year, Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff

Henning Rudolf Adolf Karl von Holtzendorff (9 January 1853 – 7 June 1919) was a German admiral during World War I, who became famous for his December 1916 memo about unrestricted submarine warfare against the United Kingdom. He was a recipient ...

became the fleet commander. Holtzendorff's tenure as fleet commander was marked by strategic experimentation, owing to the increased threat the latest underwater weapons posed and the fact that the new s were too wide to pass through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal. Accordingly, the fleet was transferred from the Baltic Sea port of Kiel to the North Sea port of Wilhelmshaven on 1 April 1910.

In May 1910, the fleet conducted training maneuvers in the Kattegat. These were in accordance with Holtzendorff's strategy, which envisioned drawing the Royal Navy into the narrow waters there. The annual summer cruise was to Norway, and was followed by fleet training, during which another fleet review was held in Danzig on 29 August. After the conclusion of the maneuvers, Schröder was promoted to chief of the ''

In May 1910, the fleet conducted training maneuvers in the Kattegat. These were in accordance with Holtzendorff's strategy, which envisioned drawing the Royal Navy into the narrow waters there. The annual summer cruise was to Norway, and was followed by fleet training, during which another fleet review was held in Danzig on 29 August. After the conclusion of the maneuvers, Schröder was promoted to chief of the ''Marinestation der Ostsee The Marinestation der Ostsee (Baltic Sea Naval Station) was a command of both the Imperial German Navy, and the Reichsmarine which served as a shore command for German naval units operating primarily in the Baltic Sea. The station was headquartered ...

'' (Naval Station of the Baltic Sea), his place aboard ''Preussen'' being taken by ''VAdm'' Friedrich von Ingenohl

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Friedrich von Ingenohl (30 June 1857 – 19 December 1933) was a German admiral from Neuwied best known for his command of the German High Seas Fleet at the beginning of World War I.

He was the son of a tradesman. H ...

. A training cruise into the Baltic followed at the end of the year. In March 1911, the fleet held exercises in the Skagerrak and Kattegat, and the year's autumn maneuvers were confined to the Baltic and the Kattegat. Another fleet review was held during the exercises for a visiting Austro-Hungarian delegation that included Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria, (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His assassination in Sarajevo was the most immediate cause of World War I.

Fr ...

and Admiral Rudolf Montecuccoli

Rudolf Graf Montecuccoli degli Erri (22 February 1843-16 May 1922) was chief of the Austro-Hungarian Navy from 1904 to 1913 and largely responsible for the modernization of the fleet before the First World War.

Overview

Montecuccoli was born i ...

.

In mid-1912, due to the Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in April 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, a ...

, the summer cruise was confined to the Baltic, to avoid exposing the fleet during the period of heightened tension with Britain and France. On 30 January 1913, Holtzendorff was relieved as the fleet commander, owing in large part due to Wilhelm II's displeasure with his strategic vision; Ingenohl took Holtzendorff's place, and ''KAdm'' Reinhard Scheer

Carl Friedrich Heinrich Reinhard Scheer (30 September 1863 – 26 November 1928) was an Admiral in the Imperial German Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Scheer joined the navy in 1879 as an officer cadet and progressed through the ranks, commandin ...

in turn replaced Ingenohl as II Squadron commander on 4 February. In late August, the squadron steamed through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal at the start of the autumn maneuvers to reach the island of Helgoland; the voyage through the canal was notable, because the canal had been closed for over a year while it was enlarged to allow the passage of larger dreadnought battleship

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

s. ''Preussen'' went into dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

in November for periodic maintenance, and as a result, missed training exercises conducted that month.

''Preussen'' participated in ceremonies at Sonderburg on 2 May to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Dybbøl

The Battle of Dybbøl ( da, Slaget ved Dybbøl; german: Erstürmung der Düppeler Schanzen) was the key battle of the Second Schleswig War, fought between Denmark and Prussia. The battle was fought on the morning of 18 April 1864, following ...

of the Second Schleswig War

The Second Schleswig War ( da, Krigen i 1864; german: Deutsch-Dänischer Krieg) also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War was the second military conflict over the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the nineteenth century. T ...

; she was joined by her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

s and , the battleship , and the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

. The ship was present during the fleet cruise to Norway in July 1914, which was cut short by the July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the major powers of Europe in the summer of 1914, Causes of World War I, which led to the outbreak of World War I (1914–1918). The crisis began on 28 June 1 ...

following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated on 28 June 1914 by Bosnian Serb student Gavrilo Princip. They were shot at close range whil ...

the month before and subsequent rise in international tensions. On 25 July the ship's crew was made aware of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

's ultimatum to Serbia; ''Preussen'' left Norway to rendezvous with the rest of the fleet the following day. ''Preussen'' had been slated to be decommissioned at the end of the year, her place as the squadron flagship to be taken by the dreadnought . ''Preussen'' was to then replace in the Reserve Division of the Baltic Sea, but the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

cancelled those plans.

World War I

After the outbreak of war in August 1914, the German command deployed II Squadron in the

After the outbreak of war in August 1914, the German command deployed II Squadron in the German Bight

The German Bight (german: Deutsche Bucht; da, tyske bugt; nl, Duitse bocht; fry, Dútske bocht; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and ...

to defend Germany's coast from a major attack from the Royal Navy that the Germans presumed was imminent. ''Preussen'' and her squadron mates were stationed in the mouth of the Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Repu ...

to support the vessels on patrol duty in the Bight. Once it became clear that the British would not attack the High Seas Fleet, the Germans began a series of operations designed to lure out a portion of the numerically superior British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

and destroy it. By achieving a rough equality of forces, the German navy could then force a decisive battle in the southern portion of the North Sea.

The first such operation in which the High Seas Fleet participated was the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby

The Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby on 16 December 1914 was an attack by the Imperial German Navy on the British ports of Scarborough, Hartlepool, West Hartlepool and Whitby. The bombardments caused hundreds of civilian casualties an ...

on 15–16 December 1914. The main fleet acted as distant support for ''KAdm'' Franz von Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Franz von Hipper joined the German Navy in 1881 as an officer cadet. He commanded several torpedo boat units an ...

's battlecruiser squadron while it raided the coastal towns. On the evening of 15 December, the fleet came to within of an isolated squadron of six British battleships. However, skirmishes between the rival destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

screens in the darkness convinced Ingenohl, who was now the German fleet commander, that the entire Grand Fleet was deployed before him. Under orders from Wilhelm II to avoid battle if victory was not certain, Ingenohl broke off the engagement and turned the battlefleet back towards Germany. At the end of the month, Scheer was replaced by ''KAdm'' Felix Funke

Felix Funke (3 January 1865 – 22 July 1932) was a German admiral of the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial German Navy).

Early life

Funke was born in Hirschberg (Jelenia Góra), Prussian Silesia. His father Adolf Funke, originally from Magdebu ...

, Scheer going on to command III Battle Squadron

The III Battle Squadron was a unit of the German High Seas Fleet before and during World War I. The squadron saw action throughout the war, including the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916, where it formed the front of the German lin ...

.

On 14 March 1915, ''Preussen'' went to Kiel for periodic maintenance, and she was replaced as the squadron flagship by the battleship . The latter vessel held the position for the remainder of the squadron's existence, with the exceptions of 19 September to 16 October 1915, 25 February to 7 April 1916, in September that year, and from 22 January to 10 February 1917; during each of these periods, ''Preussen'' temporarily resumed the flagship role. Starting in April 1916, the ships of II Squadron were tasked with patrolling the Danish straits

The Danish straits are the straits connecting the Baltic Sea to the North Sea through the Kattegat and Skagerrak. Historically, the Danish straits were internal waterways of Denmark; however, following territorial losses, Øresund and Fehmarn Be ...

; each ship of the squadron was to rotate through the duty, the others remaining in the Elbe or serving with the main fleet. ''Preussen'' began her first stint on 21 April, replacing ''Hessen''; she was accordingly absent during the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft

The Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft, often referred to as the Lowestoft Raid, was a naval battle fought during the First World War between the German Empire and the British Empire in the North Sea.

The German fleet sent a battlecruiser ...

three days later. On 4 May, ''Preussen'' was relieved and she returned to the Elbe, though she was transferred back to the straits on 21 May, remaining there until 8 June. As a result, she missed the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy ...

, fought on 31 May – 1 June in the North Sea. Her sister ship ''Lothringen'' also missed the battle, as she had been deemed to be in too poor a condition to participate in the fleet sortie.

Jutland proved to Scheer, who was now the fleet commander, that the pre-dreadnought battleships were too vulnerable to take part in a major fleet action, and so he detached II Squadron from the High Seas Fleet. As a result, ''Preussen'' remained in service only as a guard ship

A guard ship is a warship assigned as a stationary guard in a port or harbour, as opposed to a coastal patrol boat, which serves its protective role at sea.

Royal Navy

In the Royal Navy of the eighteenth century, peacetime guard ships were usual ...

. She saw further stints in the Danish straits from 30 June to 23 July and from 15 to 31 August. On 13 March 1917, ''Preussen'' left the Elbe and steamed to the Baltic, where she was temporarily used as an icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

to clear a path to Swinemünde. She was decommissioned on 5 August, and most of her crew were transferred to the new battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

. From then to the end of the war, she served as a tender for III U-boat Flotilla based in Wilhelmshaven. ''Preussen'' briefly held Edouard Izac

Edouard Victor Michel Izac (December 18, 1891 – January 18, 1990) was a lieutenant in the United States Navy during World War I, a Representative from California and a Medal of Honor recipient.

Born in Cresco, Iowa, Izac grew up in a rural se ...

, a US Navy sailor captured after his ship was sunk by , in June 1918; Izac would go on to escape from a German prisoner of war camp and win the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor. ...

.

Post-war career

Following the German defeat in World War I, the German navy was reorganized as the ''Reichsmarine

The ''Reichsmarine'' ( en, Realm Navy) was the name of the German Navy during the Weimar Republic and first two years of Nazi Germany. It was the naval branch of the ''Reichswehr'', existing from 1919 to 1935. In 1935, it became known as the ''K ...

'' according to the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

. The new navy was permitted to retain eight pre-dreadnought battleships under Article 181—two of which would be in reserve—for coastal defense. ''Preussen'' was among those ships chosen to remain on active service with the ''Reichsmarine''. The ship was converted into a parent ship for F-type minesweeper

A minesweeper is a small warship designed to remove or detonate naval mines. Using various mechanisms intended to counter the threat posed by naval mines, minesweepers keep waterways clear for safe shipping.

History

The earliest known usage of ...

s at the Kriegsmarinewerft

Kriegsmarinewerft (or, prior to 1935, Reichsmarinewerft) Wilhelmshaven was, between 1918 and 1945, a naval shipyard in the German Navys extensive base at Wilhelmshaven, ( west of Hamburg).

History

The shipyard was founded on the site of the Wilh ...

in Wilhelmshaven in 1919; the ship was disarmed and platforms for holding the minesweepers were installed.

''Preussen'' was commissioned with the ''Reichsmarine'' to support the minesweeping effort, though she proved to be too top-heavy to serve as an effective mothership, and she was soon replaced by the old light cruiser . ''Preussen'' was placed in reserve and was left out of service until 1929, when she was stricken from the naval register on 5 April. The ''Reichsmarine'' sold her to ship breakers on 25 February 1931 for 216,800 Reichsmark

The (; sign: ℛℳ; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until 20 June 1948 in West Germany, where it was replaced with the , and until 23 June 1948 in East Germany, where it was replaced by the East German mark. The Reich ...

s. ''Preussen'' was subsequently broken up for scrap in Wilhelmshaven, though a length of her hull was retained as a testing target for underwater weapons, including torpedoes and mines. The section of hull was nicknamed "SMS ''Vierkant'' ("SMS Rectangle"). Allied bombers attacked and sank the section of ''Preussen''s hull in April 1945. It was eventually raised and scrapped in late 1954.

Footnotes

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Preussen Braunschweig-class battleships World War I battleships of Germany 1903 ships Ships built in Stettin