Royal Court of Scotland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Royal Court of Scotland was the administrative, political and artistic centre of the

The Royal Court of Scotland was the administrative, political and artistic centre of the

''Alba: The Gaelic Kingdom of Scotland, AD 800–1124, The Making of Scotland''

(Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2002), p. 13.

Little is known about the structure of the Scottish royal court in the period before the reign of David I. Some minor posts that are mentioned in later sources are probably Gaelic in origin. These include the senior clerks of the Provend and the Liverence, in charge of the distribution of food, and the Hostarius (later Usher or "Doorward"), who was in charge of the royal bodyguard.G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (Berkeley CA.: University of California Press, 1965), pp. 11–12. By the late thirteenth century the court had taken on a distinctly feudal character. The major offices were the Steward or Stewart,

Little is known about the structure of the Scottish royal court in the period before the reign of David I. Some minor posts that are mentioned in later sources are probably Gaelic in origin. These include the senior clerks of the Provend and the Liverence, in charge of the distribution of food, and the Hostarius (later Usher or "Doorward"), who was in charge of the royal bodyguard.G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (Berkeley CA.: University of California Press, 1965), pp. 11–12. By the late thirteenth century the court had taken on a distinctly feudal character. The major offices were the Steward or Stewart,

After the crown, the most important government institution in the late Middle Ages was the king's council, composed of the king's closest advisers and presided over by the Lord Chancellor. Unlike its counterpart in England, the king's council in Scotland retained legislative and judicial powers. It was relatively small, with normally less than 10 members in a meeting, some of whom were nominated by parliament, particularly during the many minorities of the era, as a means of limiting the power of a regent.Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community'', pp. 22–3.

The council was a virtually full-time institution by the late fifteenth century, and surviving records from the period indicate that it was critical in the working of royal justice. Nominally members of the council were some of the great magnates of the realm, but they rarely attended meetings. Most of the active members of the council for most of the late Medieval Period were career administrators and lawyers, almost exclusively university-educated clergy. The most successful of these moved on to occupy the major ecclesiastical positions in the realm as bishops and, towards the end of the period, archbishops. By the end of the fifteenth century, this group was being joined by increasing numbers of literate laymen, often secular lawyers, of which the most successful gained preferment in the judicial system and grants of lands and lordships.

After the crown, the most important government institution in the late Middle Ages was the king's council, composed of the king's closest advisers and presided over by the Lord Chancellor. Unlike its counterpart in England, the king's council in Scotland retained legislative and judicial powers. It was relatively small, with normally less than 10 members in a meeting, some of whom were nominated by parliament, particularly during the many minorities of the era, as a means of limiting the power of a regent.Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community'', pp. 22–3.

The council was a virtually full-time institution by the late fifteenth century, and surviving records from the period indicate that it was critical in the working of royal justice. Nominally members of the council were some of the great magnates of the realm, but they rarely attended meetings. Most of the active members of the council for most of the late Medieval Period were career administrators and lawyers, almost exclusively university-educated clergy. The most successful of these moved on to occupy the major ecclesiastical positions in the realm as bishops and, towards the end of the period, archbishops. By the end of the fifteenth century, this group was being joined by increasing numbers of literate laymen, often secular lawyers, of which the most successful gained preferment in the judicial system and grants of lands and lordships.

The union of the Gaelic and

The union of the Gaelic and

''Alba: The Gaelic Kingdom of Scotland''

p. 33. At least from the accession of

Ideas of chivalry, similar to those that developed at the English court of Edward III, began to dominate in Scotland during the reign of the Anglophile David II (1329–71).

Ideas of chivalry, similar to those that developed at the English court of Edward III, began to dominate in Scotland during the reign of the Anglophile David II (1329–71).

Early Medieval Scotland and Ireland shared a common culture and language. There are much fuller historical sources for Ireland, which suggest that there would have been filidh in Scotland, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge and culture in the Gaelic to the next generation.R. Crawford

Early Medieval Scotland and Ireland shared a common culture and language. There are much fuller historical sources for Ireland, which suggest that there would have been filidh in Scotland, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge and culture in the Gaelic to the next generation.R. Crawford

''Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature''

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), .R. A. Houston, ''Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), , p. 76. After the "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court, a less highly regarded order of bards took over the functions of the filidh, often trained in bardic schools. They probably accompanied their poetry on the harp. When Alexander III (r. 1249–86) met Edward I in England he was accompanied by a Master Elyas, described as "the king of Scotland's harper". The captivity of James I in England from 1406 to 1423, where he earned a reputation as a poet and composer, may have led him to take English and continental styles and musicians back to the Scottish court on his release.K. Elliott and F. Rimmer, ''A History of Scottish Music'' (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1973), , pp. 8–12. The story of the execution of James III's favourites, including the English musician William Roger, at Lauder Bridge in 1482, may indicate his interest in music. Renaissance monarchs often used chapels to impress visiting dignitaries. James III also founded a new large hexagonal Chapel Royal at

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is

From the fifteenth century the records of the Scottish court contain references to artists. Matthew the "king's painter" is the first mentioned, said to be at Linlithgow in 1434. The most impressive works and artists were imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, generally considered the centre of painting in the

From the fifteenth century the records of the Scottish court contain references to artists. Matthew the "king's painter" is the first mentioned, said to be at Linlithgow in 1434. The most impressive works and artists were imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, generally considered the centre of painting in the

The royal centre at Forteviot was not in a defensive situation and there are no traces of any fortified enclosure. There is some archaeological evidence of artistic and architectural patronage on an impressive scale. The most notable piece of sculpture is the

The royal centre at Forteviot was not in a defensive situation and there are no traces of any fortified enclosure. There is some archaeological evidence of artistic and architectural patronage on an impressive scale. The most notable piece of sculpture is the

Lavish spending on luxurious clothing, fine foods, the patronage of innovative architecture, art and music can be seen from the reign of James I. James III is generally thought to have amassed a surplus and, despite his lavish spending, James IV was able to sustain his finances, probably thanks mainly to an increase in revenues from crown lands, the latter doubling his income from this source across his reign. James V was able to undertake lavish court spending due to two dowries from the King of France and his ability to exploit the wealth of the church, despite which spending kept pace with expanding income.J. E. A. Dawson, ''Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 138–9. Mary, Queen of Scots' attempt to create a court in the image the French Renaissance monarchy was hampered by financial limitations, intensified by the general price inflation of the period.

The court of James VI proved extremely expensive and may have provided one of the motivations for the attempted coup of the

Lavish spending on luxurious clothing, fine foods, the patronage of innovative architecture, art and music can be seen from the reign of James I. James III is generally thought to have amassed a surplus and, despite his lavish spending, James IV was able to sustain his finances, probably thanks mainly to an increase in revenues from crown lands, the latter doubling his income from this source across his reign. James V was able to undertake lavish court spending due to two dowries from the King of France and his ability to exploit the wealth of the church, despite which spending kept pace with expanding income.J. E. A. Dawson, ''Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 138–9. Mary, Queen of Scots' attempt to create a court in the image the French Renaissance monarchy was hampered by financial limitations, intensified by the general price inflation of the period.

The court of James VI proved extremely expensive and may have provided one of the motivations for the attempted coup of the

The Royal Court of Scotland was the administrative, political and artistic centre of the

The Royal Court of Scotland was the administrative, political and artistic centre of the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

. It emerged in the tenth century and continued until it ceased to function when James VI

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

inherited the throne of England in 1603. For most of the medieval era, the king had no "capital" as such. The Pictish centre of Forteviot

Forteviot ( gd, Fothair Tabhaicht) (Ordnance Survey ) is a village in Strathearn, Scotland on the south bank of the River Earn between Dunning and Perth. It lies in the council area of Perth and Kinross. The population in 1991 was 160.

The pres ...

was the chief royal seat of the early Gaelic Kingdom of Alba that became the Kingdom of Scotland. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries Scone was a centre for royal business. Edinburgh only began to emerge as the capital in the reign of James III but his successors undertook occasional royal progress to a part of the kingdom. Little is known about the structure of the Scottish royal court in the period before the reign of David I when it began to take on a distinctly feudal character, with the major offices of the Steward, Chamberlain

Chamberlain may refer to:

Profession

*Chamberlain (office), the officer in charge of managing the household of a sovereign or other noble figure

People

*Chamberlain (surname)

**Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855–1927), German-British philosop ...

, Constable, Marischal and Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

. By the early modern era the court consisted of leading nobles, office holders, ambassadors and supplicants who surrounded the king or queen. The Chancellor was now effectively the first minister of the kingdom and from the mid-sixteenth century he was the leading figure of the Privy Council.

At least from the accession of David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland ...

Gaelic ceased to be the main language of the royal court and was probably replaced by French. In the late Middle Ages, Middle Scots

Middle Scots was the Anglic language of Lowland Scotland in the period from 1450 to 1700. By the end of the 15th century, its phonology, orthography, accidence, syntax and vocabulary had diverged markedly from Early Scots, which was virtually ...

, became the dominant language. Ideas of chivalry began to dominate during the reign of David II. Tournaments

A tournament is a competition involving at least three competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:

# One or more competitions held at a single venue and concentr ...

provided one focus of display. The Scottish crown in the fifteenth century adopted the example of the Burgundian court, through formality and elegance putting itself at the centre of culture and political life. By the sixteenth century, the court was central to the patronage and dissemination of Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

works and ideas. It was also central to the staging of lavish display that portrayed the political and religious role of the monarchy.

There were probably filidh, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king. After the "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court, a less highly regarded order of bards took over their functions, accompanying their poetry on the harp. James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

may have taken English and continental styles and musicians back to the Scottish court after his captivity and Scotland followed the trend of Renaissance courts for instrumental accompaniment and playing. Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court. James VI became patron and member of a loose circle of Scottish Jacobean court poets and musicians, later called the Castalian Band

The Castalian Band is a modern name given to a grouping of Scottish Jacobean poets, or makars, which is said to have flourished between the 1580s and early 1590s in the court of James VI and consciously modelled on the French example of the P ...

. From the fifteenth century the records of the Scottish court contain references to artists. The most impressive works and artists were imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands. James VI employed two Flemish artists, Arnold Bronckorst

Arnold Bronckhorst, or Bronckorst or Van Bronckhorst ( 1565–1583) was a Flemish or Dutch painter who was court painter to James VI of Scotland.Adrian Vanson

Adrian Vanson (died c. 1602) was court portrait painter to James VI of Scotland.

Family and artistic background

Adrian was probably born in Breda, the son of Willem Claesswen van Son by Kathelijn Adriaen Matheus de Blauwverversdochter. His uncle ...

, who have left a visual record of the king and major figures at the court. In the early Middle Ages Forteviot

Forteviot ( gd, Fothair Tabhaicht) (Ordnance Survey ) is a village in Strathearn, Scotland on the south bank of the River Earn between Dunning and Perth. It lies in the council area of Perth and Kinross. The population in 1991 was 160.

The pres ...

probably served as a royal palace. The introduction of feudalism into Scotland in the twelfth century led to the introduction of royal castles. Under the Stuart Dynasty there was a programme of extensive building and rebuilding of royal palaces.

Lavish spending on luxurious clothing, fine foods, the patronage of innovative architecture, art and music can be seen from the reign of James I. His successors struggled with different levels of success with the costs of the royal court. After James VI inherited the English throne in 1603 the Scottish court effectively ceased to exist, ending its role as a centre of artistic patronage, political display and intrigue.

Location

For most of the medieval era, the king was itinerant and had no "capital" as such. The Pictish centre ofForteviot

Forteviot ( gd, Fothair Tabhaicht) (Ordnance Survey ) is a village in Strathearn, Scotland on the south bank of the River Earn between Dunning and Perth. It lies in the council area of Perth and Kinross. The population in 1991 was 160.

The pres ...

was the chief royal seat of the early Gaelic Kingdom of Alba

The Kingdom of Alba ( la, Scotia; sga, Alba) was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286. The latter's death led indirectly to an invasion of Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 and the ...

that became the Kingdom of Scotland. It was used by Cinaed mac Ailpin

Kenneth MacAlpin ( mga, Cináed mac Ailpin, label=Medieval Gaelic, gd, Coinneach mac Ailpein, label=Modern Scottish Gaelic; 810 – 13 February 858) or Kenneth I was King of Dál Riada (841–850), King of the Picts (843–858), and the Kin ...

(Kenneth MacAlpin, r. 843–58) and his brother Domnall mac Ailpín (Donald I MacAlpin, 812–62). Later poetic tradition suggests that Máel Coluim mac Donnchada

Malcolm III ( mga, Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, label=Medieval Gaelic; gd, Maol Chaluim mac Dhonnchaidh; died 13 November 1093) was King of Scotland from 1058 to 1093. He was later nicknamed "Canmore" ("ceann mòr", Gaelic, literally "big head" ...

(Malcolm III "Canmore", r. 1058–93) was also resident and charters of Malcolm IV

Malcolm IV ( mga, Máel Coluim mac Eanric, label=Medieval Gaelic; gd, Maol Chaluim mac Eanraig), nicknamed Virgo, "the Maiden" (between 23 April and 24 May 11419 December 1165) was King of Scotland from 1153 until his death. He was the eldest ...

(dated 1162–64) and of William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

(dated 1165–71) indicate that it remained important into the twelfth century. After this it fell from the royal circuit, but it remained a royal estate until the fourteenth century.S. T. Driscoll''Alba: The Gaelic Kingdom of Scotland, AD 800–1124, The Making of Scotland''

(Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2002), p. 13.

David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland ...

(r. 1124–53) tried to build up Roxburgh

Roxburgh () is a civil parish and formerly a royal burgh, in the historic county of Roxburghshire in the Scottish Borders, Scotland. It was an important trading burgh in High Medieval to early modern Scotland. In the Middle Ages it had at leas ...

as a royal centre,J. Bannerman, "MacDuff of Fife," in A. Grant & K. Stringer, eds., ''Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community, Essays Presented to G. W. S. Barrow'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993), pp. 22–3. but in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, more charters were issued at Scone than any other location, suggesting that this was a centre for royal business. Other popular locations in the early part of the era were nearby Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth i ...

, Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

, Dunfermline and Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

.P. G. B. McNeill and Hector L. MacQueen, eds, ''Atlas of Scottish History to 1707'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), pp. 159–63.

The court was severely disrupted during the Wars of Independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars

Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against for ...

(1296–1357) and almost ceased to function, but was restored by Robert I and his Stuart successors, who attempted to embody national and dynastic identity. In the later Middle Ages the king moved between royal castles, particularly Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth i ...

and Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

, but continued to hold judicial sessions throughout the kingdom. Edinburgh only began to emerge as the capital in the reign of James III (r. 1460–88) at the cost of considerable unpopularity, as it was felt that the king's presence in the rest of the kingdom was part of his role.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 14–15. Although increasingly based at the royal palace of Holyrood in Edinburgh, the monarch and the court still spent time at the refurbished royal palaces of Linlithgow

Linlithgow (; gd, Gleann Iucha, sco, Lithgae) is a town in West Lothian, Scotland. It was historically West Lothian's county town, reflected in the county's historical name of Linlithgowshire. An ancient town, it lies in the Central Belt on a ...

, Stirling and Falkland, and still undertook occasional royal progress to different parts of the kingdom to ensure that the rule of law, royal authority or smooth government was maintained.J. Goodare, ''The Government of Scotland, 1560–1625'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), , p. 141.

Composition

Offices

Little is known about the structure of the Scottish royal court in the period before the reign of David I. Some minor posts that are mentioned in later sources are probably Gaelic in origin. These include the senior clerks of the Provend and the Liverence, in charge of the distribution of food, and the Hostarius (later Usher or "Doorward"), who was in charge of the royal bodyguard.G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (Berkeley CA.: University of California Press, 1965), pp. 11–12. By the late thirteenth century the court had taken on a distinctly feudal character. The major offices were the Steward or Stewart,

Little is known about the structure of the Scottish royal court in the period before the reign of David I. Some minor posts that are mentioned in later sources are probably Gaelic in origin. These include the senior clerks of the Provend and the Liverence, in charge of the distribution of food, and the Hostarius (later Usher or "Doorward"), who was in charge of the royal bodyguard.G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (Berkeley CA.: University of California Press, 1965), pp. 11–12. By the late thirteenth century the court had taken on a distinctly feudal character. The major offices were the Steward or Stewart, Chamberlain

Chamberlain may refer to:

Profession

*Chamberlain (office), the officer in charge of managing the household of a sovereign or other noble figure

People

*Chamberlain (surname)

**Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855–1927), German-British philosop ...

, Constable, Marischal and Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

. The office of Stewart, responsible for management of the king's household, was created by David I and given as an hereditary office to Walter Fitzalan

Walter FitzAlan (1177) was a twelfth-century English baron who became a Scottish magnate and Steward of Scotland. He was a younger son of Alan fitz Flaad and Avelina de Hesdin. In about 1136, Walter entered into the service of David I, King o ...

, whose descendants became the House of Stewart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

. The office was merged with the crown when Robert II inherited the throne. The other major secular posts also had a tendency to become hereditary. The Chamberlain was responsible for royal finances and the Constable for organising the crown's military forces, while the Marishchal had a leadership role in battle. The Chancellor, who was usually a clergyman in the Middle Ages, had charge of the king's chapel, which was also the major administrative centre of the crown, and had control of the letters, legal writs and seals. Under him were various posts, usually filled by clerics, including the custodian of the great seal. From the reign of James III onwards, the post of Chancellor was increasingly taken by leading laymen.

By the early modern era the court consisted of leading nobles, office holders, ambassadors and supplicants who surrounded the king or queen. At its centre was the monarch and members of the Privy Chamber

A privy chamber was the private apartment of a royal residence in England.

The Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber were noble-born servants to the Crown who would wait and attend on the King in private, as well as during various court activities, f ...

. Gentleman of the chamber

''Valet de chambre'' (), or ''varlet de chambre'', was a court appointment introduced in the late Middle Ages, common from the 14th century onwards. Royal households had many persons appointed at any time. While some valets simply waited on t ...

were usually leading nobles or individuals with kinship links to the leading noble families. They had direct access to the monarch, with the implication of being able to exert influence, and were usually resident at the court.Goodare, ''The Government of Scotland'', pp. 88–9. The Chancellor was now effectively the first minister of the kingdom and from the mid-sixteenth century he was the leading figure of the Privy Council. His department, the chancery, was responsible for the Great Seal, which was needed to process the inheritance of land titles and the confirmation of land transfers. His key responsibility was to preside at meetings of the Privy Council, and, on those rare occasions he attended, at meetings of the court of session.Goodare, ''The Government of Scotland'', pp. 150–1. The second most prestigious office was now the Secretary, who was responsible for the records of the Privy Council and for foreign policy, including the borders, despite which the post retained its importance after the Union of Crowns in 1603. The Treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

was the last of the major posts and, with the Comptroller, dealt with the royal finances until the Comptroller's office was merged into the Treasurer's from 1610.Goodare, ''The Government of Scotland'', p. 152.

The Lord President of the Court of Session

The Lord President of the Court of Session and Lord Justice General is the most senior judge in Scotland, the head of the judiciary, and the presiding judge of the College of Justice, the Court of Session, and the High Court of Justiciary. The L ...

, often known simply as the Lord President, acted as a link between the Privy Council and the Court.Goodare, ''The Government of Scotland'', p. 160. The king's advocate acted as the legal council. The post emerged in the 1490s to deal with the king's patrimonial land rights and from 1555 there were usually two king's councillors, indicating the increase in the level of work. From 1579 they increasingly became a public prosecutor.Goodare, ''The Government of Scotland'', p. 164. After the union most of the offices remained, but political power was increasingly centred in London.

General council

After the crown, the most important government institution in the late Middle Ages was the king's council, composed of the king's closest advisers and presided over by the Lord Chancellor. Unlike its counterpart in England, the king's council in Scotland retained legislative and judicial powers. It was relatively small, with normally less than 10 members in a meeting, some of whom were nominated by parliament, particularly during the many minorities of the era, as a means of limiting the power of a regent.Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community'', pp. 22–3.

The council was a virtually full-time institution by the late fifteenth century, and surviving records from the period indicate that it was critical in the working of royal justice. Nominally members of the council were some of the great magnates of the realm, but they rarely attended meetings. Most of the active members of the council for most of the late Medieval Period were career administrators and lawyers, almost exclusively university-educated clergy. The most successful of these moved on to occupy the major ecclesiastical positions in the realm as bishops and, towards the end of the period, archbishops. By the end of the fifteenth century, this group was being joined by increasing numbers of literate laymen, often secular lawyers, of which the most successful gained preferment in the judicial system and grants of lands and lordships.

After the crown, the most important government institution in the late Middle Ages was the king's council, composed of the king's closest advisers and presided over by the Lord Chancellor. Unlike its counterpart in England, the king's council in Scotland retained legislative and judicial powers. It was relatively small, with normally less than 10 members in a meeting, some of whom were nominated by parliament, particularly during the many minorities of the era, as a means of limiting the power of a regent.Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community'', pp. 22–3.

The council was a virtually full-time institution by the late fifteenth century, and surviving records from the period indicate that it was critical in the working of royal justice. Nominally members of the council were some of the great magnates of the realm, but they rarely attended meetings. Most of the active members of the council for most of the late Medieval Period were career administrators and lawyers, almost exclusively university-educated clergy. The most successful of these moved on to occupy the major ecclesiastical positions in the realm as bishops and, towards the end of the period, archbishops. By the end of the fifteenth century, this group was being joined by increasing numbers of literate laymen, often secular lawyers, of which the most successful gained preferment in the judicial system and grants of lands and lordships.

Privy Council

The Privy Council developed out of the theoretically larger king's or queen's council of leading nobles and office holders in the sixteenth century. "Secret Councils" had been maintained during the many regencies of the later medieval era, but the origins of the Privy Council were in 1543, during the minority ofMary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

(r. 1542–67). After her majority it was not disbanded, but continued to sit and became an accepted part of government.Goodare, ''The Government of Scotland'', pp. 35 and 130. While in session in Edinburgh, the Privy Council met in what is now the West Drawing Room at the Palace of Holyroodhouse. When the monarch was at one of the royal palaces or visiting a region of the kingdom on official business, the council would normally go with them and as a result of being away from its servants, records and members, its output tended to decrease. While the monarch was away on a holiday or hunting trip, the council usually stayed in session in Edinburgh and continued to run the government.

The Privy Council's primary function was judicial, but it also acted as a body of advisers to the monarch and as a result its secondary function was as an executive in the absence or minority of the monarch.F. N. McCoy, ''Robert Baillie and the Second Scots Reformation'' (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1974), , pp. 1–2. Although the monarch might often attend the council, their presence was not necessary for the council to act with royal authority. Like parliament, it had the power to issue acts that could have the force of law.R. Mitchison, ''Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), , p. 15. Although the theoretical membership of the council was relatively large, at around 30 persons, most of the business was carried out by an informal inner group, consisting mainly of the officers of state.

Culture

Language

The union of the Gaelic and

The union of the Gaelic and Pictish

Pictish is the extinct Brittonic language spoken by the Picts, the people of eastern and northern Scotland from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Virtually no direct attestations of Pictish remain, short of a limited number of geographica ...

kingdoms that created the kingdom of Alba in the eighth century led to a domination by Gaelic language and culture.Driscoll''Alba: The Gaelic Kingdom of Scotland''

p. 33. At least from the accession of

David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland ...

(r. 1124–53), as part of a Davidian Revolution

The Davidian Revolution is a name given by many scholars to the changes which took place in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of David I (1124–1153). These included his foundation of burghs, implementation of the ideals of Gregorian ...

that introduced French culture and political systems, Gaelic ceased to be the main language of the royal court and was probably replaced by French. So complete was this cultural transformation that David's successors Malcolm IV

Malcolm IV ( mga, Máel Coluim mac Eanric, label=Medieval Gaelic; gd, Maol Chaluim mac Eanraig), nicknamed Virgo, "the Maiden" (between 23 April and 24 May 11419 December 1165) was King of Scotland from 1153 until his death. He was the eldest ...

and William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

, according to the English ''Barnwell Chronicle'', confessed themselves to be French in "both in race and in manners, in language and culture".C. Eddington, "Royal Court: 1 to 1542", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 535–7. However, Gaelic culture remained part of the court throughout the Middle Ages, with Gaelic musicians and poets still being patronised by James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

(1488–1513), who was a Gaelic speaker. In the late Middle Ages, Middle Scots

Middle Scots was the Anglic language of Lowland Scotland in the period from 1450 to 1700. By the end of the 15th century, its phonology, orthography, accidence, syntax and vocabulary had diverged markedly from Early Scots, which was virtually ...

, became the dominant language of the country. It was derived largely from Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

, with the addition of elements from the Gaelic, French & Scandinavian languages. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct language from the late fourteenth century onwards.Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community'', pp. 60–7. As the ruling elite gradually abandoned French, they began to adopt Middle Scots, and by the fifteenth century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

(r. 1406–37) onwards and of the court soon after.

Display

Tournaments

A tournament is a competition involving at least three competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:

# One or more competitions held at a single venue and concentr ...

provided one focus of display. These occurred in 1449 at Stirling Castle in the reign of James II (r. 1437–60), where the Burgundian adventurer Jacques de Lalaing

Jacques de Lalaing (1421–1453), perhaps the most renowned knight of Burgundy in the 15th century, was reportedly one of the best medieval tournament fighters of all time. A Walloon knight, he began his military career in the service of Adolp ...

fought the greatest Scottish knights. In the early sixteenth century chivalry was evolving from a practical military ethos into a more ornamental and honorific cult. It saw its origins in the classical era, with Hector of Troy, Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

and Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, ...

often depicted as proto-knights. James IV held tournaments of the Wild Knight and the Black Lady in 1507 and 1508, events with an Arthurian

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

theme. Tournaments were pursued enthusiastically by James V (r. 1513–42) who, proud of his membership of international orders of knighthood, displayed their insignia on the Gateway at Linlithgow Palace.

Like most western European monarchies, the Scottish crown in the fifteenth century adopted the example of the Burgundian court, through formality and elegance putting itself at the centre of culture and political life, defined with display, ritual and pageantry, reflected in elaborate new palaces and patronage of the arts.Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community'', p. 18. By the sixteenth century, the court was central to the patronage and dissemination of Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

works and ideas. It was also central to the staging of lavish display that portrayed the political and religious role of the monarchy. During her brief personal rule Mary, Queen of Scots brought many of the elaborate court activities that she had grown up with at the French court, with balls, masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A masq ...

s and celebrations, designed to illustrate the resurgence of the monarchy and to facilitate national unity.Andrea Thomas, "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, ''The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), , pp. 192–3. There were elaborate staged events at the investiture of Mary's husband Darnley

Darnley is an area in south-west Glasgow, Scotland, on the A727 just west of Arden (the areas are separated by the M77 motorway although a footbridge connects them). Other nearby neighbourhoods are Priesthill to the north, Southpark Village t ...

in at Candlemass in February 1566. In December of the same year there was an elaborate three-day festival to celebrate the baptism of her son and heir, the future James VI, copied from the festivities at Bayonne a year before by Charles IX of France

Charles IX (Charles Maximilien; 27 June 1550 – 30 May 1574) was King of France from 1560 until his death in 1574. He ascended the French throne upon the death of his brother Francis II in 1560, and as such was the penultimate monarch of the ...

. It included a ritual assault on a fort by mock "wild highlanders", symbolising the role of the dynasty in defending the nation. Under James VI

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

the court returned to being a centre of culture and learning and he cultivated the image of a philosopher king, evoking the models of David, Solomon and Constantine.Thomas, "The Renaissance", p. 200.

Music

Early Medieval Scotland and Ireland shared a common culture and language. There are much fuller historical sources for Ireland, which suggest that there would have been filidh in Scotland, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge and culture in the Gaelic to the next generation.R. Crawford

Early Medieval Scotland and Ireland shared a common culture and language. There are much fuller historical sources for Ireland, which suggest that there would have been filidh in Scotland, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge and culture in the Gaelic to the next generation.R. Crawford''Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature''

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), .R. A. Houston, ''Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), , p. 76. After the "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court, a less highly regarded order of bards took over the functions of the filidh, often trained in bardic schools. They probably accompanied their poetry on the harp. When Alexander III (r. 1249–86) met Edward I in England he was accompanied by a Master Elyas, described as "the king of Scotland's harper". The captivity of James I in England from 1406 to 1423, where he earned a reputation as a poet and composer, may have led him to take English and continental styles and musicians back to the Scottish court on his release.K. Elliott and F. Rimmer, ''A History of Scottish Music'' (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1973), , pp. 8–12. The story of the execution of James III's favourites, including the English musician William Roger, at Lauder Bridge in 1482, may indicate his interest in music. Renaissance monarchs often used chapels to impress visiting dignitaries. James III also founded a new large hexagonal Chapel Royal at

Restalrig

Restalrig () is a small residential suburb of Edinburgh, Scotland (historically, an estate and independent parish).

It is located east of the city centre, west of Craigentinny and to the east of Lochend, both of which it overlaps. Restalri ...

near Holyrood, that was probably designed for a large number of choristers.J. R. Baxter, "Music, ecclesiastical", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 431–2. In 1501 his son James IV refounded the Chapel Royal within Stirling Castle, with a new and enlarged choir meant to emulate St. George's Chapel at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

and it became the focus of Scottish liturgical music. Burgundian and English influences were probably reinforced when Henry VII's daughter Margaret Tudor

Margaret Tudor (28 November 1489 – 18 October 1541) was Queen of Scotland from 1503 until 1513 by marriage to King James IV. She then served as regent of Scotland during her son's minority, and successfully fought to extend her regency. Ma ...

married James IV in 1503.M. Gosman, A. A. MacDonald, A. J. Vanderjagt and A. Vanderjagt, ''Princes and Princely Culture, 1450–1650'' (Brill, 2003), , p. 163. No piece of music can be unequivocally identified with these chapels, but the survival of a Mass based on the Burgundian song ''L'Homme armé'' in the later '' Carver Choirbook'' may indicate that this was part of the Chapel Royal repertoire. James IV was said to be constantly accompanied by music, but very little surviving secular music can be unequivocally attributed to his court. An entry in the accounts of the Lord Treasurer of Scotland

The Treasurer was a senior post in the pre- Union government of Scotland, the Privy Council of Scotland.

Lord Treasurer

The full title of the post was ''Lord High Treasurer, Comptroller, Collector-General and Treasurer of the New Augmentation'', ...

indicates that when James IV was at Stirling on 17 April 1497, there was a payment "to twa fithalaris iddlersthat sang Greysteil to the king, ixs". '' Greysteil'' was an epic romance and the music survives, having been placed in a collection of lute airs in the seventeenth century.

Scotland followed the trend of Renaissance courts for instrumental accompaniment and playing. James V, as well as being a major patron of sacred music, was a talented lute player and introduced French chansons

A (, , french: chanson française, link=no, ; ) is generally any lyric-driven French song, though it most often refers to the secular polyphonic French songs of late medieval and Renaissance music. The genre had origins in the monophonic so ...

and consorts of viols to his court, although almost nothing of this secular chamber music survives.J. Patrick, ''Renaissance and Reformation'' (London: Marshall Cavendish, 2007), , p. 1264. The return of Mary, Queen of Scots from France in 1561 to begin her personal reign, and her position as a Catholic, gave a new lease of life to the choir of the Chapel Royal, but the destruction of Scottish church organs meant that instrumentation to accompany the mass had to employ bands of musicians with trumpets, drums, fifes, bagpipes and tabors. Like her father she played the lute, virginals

The virginals (or virginal) is a keyboard instrument of the harpsichord family. It was popular in Europe during the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

Description

A virginal is a smaller and simpler rectangular or polygonal form of ha ...

and (unlike her father) was a fine singer.A. Fraser, ''Mary Queen of Scots'' (London: Book Club Associates, 1969), pp. 206–7. She brought French musical influences with her, employing lutenists and viol players in her household.

James VI (r. 1566–1625) was a major patron of the arts in general. He rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling in 1594 and the choir was used for state occasions like the baptism of his son Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

.P. Le Huray, ''Music and the Reformation in England, 1549–1660'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), , pp. 83–5. He followed the tradition of employing lutenists like John Norlie for his private entertainment, as did other members of his family.T. Carter and J. Butt, ''The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), , pp. 280, 300, 433 and 541. James VI and his wife Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and Queen of England and Ireland from the union of the Scottish and Eng ...

attended wedding celebrations and danced in costume at masques.

Literature

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour John Barbour may refer to:

* John Barbour (poet) (1316–1395), Scottish poet

* John Barbour (MP for New Shoreham), MP for New Shoreham 1368-1382

* John Barbour (footballer) (1890–1916), Scottish footballer

* John S. Barbour (1790–1855), U. ...

's ''Brus

Brus ( sr-cyr, Брус, ) is a town and municipality located in the Rasina District of southern Serbia. According to the 2011 census, the population of the town is 4,572, while the population of the municipality is 16,293. It is located at above ...

'' (1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of Robert I's actions before the English invasion until the end of the war of independence. The work was extremely popular among the Scots-speaking aristocracy, and Barbour is referred to as the father of Scots poetry, holding a similar place to his contemporary Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

in England. Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court, which included James I, who wrote the extended poem ''The Kingis Quair

''The Kingis Quair'' ("The King's Book") is a fifteenth-century poem attributed to James I of Scotland. It is semi-autobiographical in nature, describing the King's capture by the English in 1406 on his way to France and his subsequent imprisonmen ...

''.

James IV's (r. 1488–1513) creation of a Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

court included the patronage of poets who were mainly clerics. These included Robert Henryson

Robert Henryson (Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the Scots ''makars'', he lived in the royal burgh of Dunfermline and is a distinctive voice in the Northern Renai ...

(c. 1450-c. 1505), who re-worked Medieval and Classical sources, such as Chaucer and Aesop

Aesop ( or ; , ; c. 620–564 BCE) was a Greek fabulist and storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as ''Aesop's Fables''. Although his existence remains unclear and no writings by him survive, numerous tales c ...

in works such as his ''Testament of Cresseid'' and ''The Morall Fabillis''. William Dunbar

William Dunbar (born 1459 or 1460 – died by 1530) was a Scottish makar, or court poet, active in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. He was closely associated with the court of King James IV and produced a large body of work i ...

(1460–1513) produced satires, lyrics, invectives and dream visions that established the vernacular as a flexible medium for poetry of any kind. Gavin Douglas

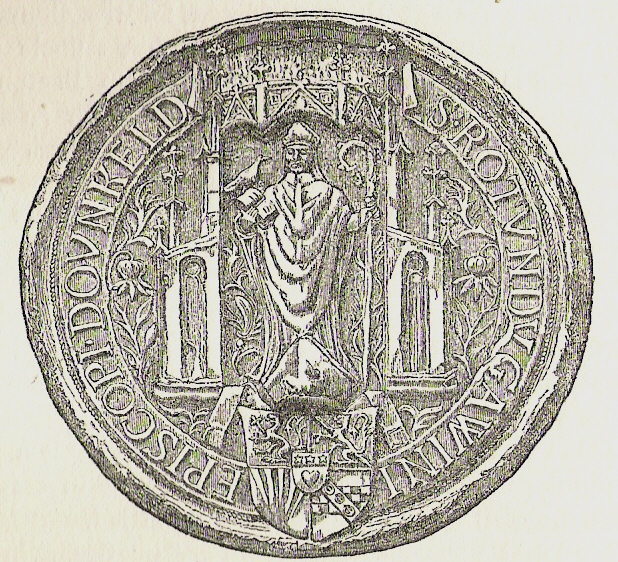

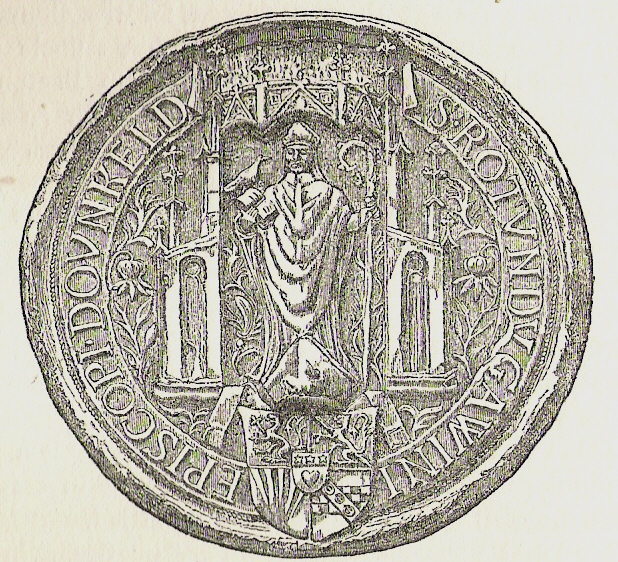

Gavin Douglas (c. 1474 – September 1522) was a Scottish bishop, makar and translator. Although he had an important political career, he is chiefly remembered for his poetry. His main pioneering achievement was the '' Eneados'', a full and fa ...

(1475–1522), who became Bishop of Dunkeld

The Bishop of Dunkeld is the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of Dunkeld, one of the largest and more important of Scotland's 13 medieval bishoprics, whose first recorded bishop is an early 12th-century cleric named Cormac. However, the first ...

, injected Humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

concerns and classical sources into his poetry.T. van Heijnsbergen, "Culture: 9 Renaissance and Reformation: poetry to 1603", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 129–30. The landmark work in the reign of James IV was Douglas's version of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of th ...

'', the ''Eneados

The ''Eneados'' is a translation into Middle Scots of Virgil's Latin ''Aeneid'', completed by the poet and clergyman Gavin Douglas in 1513.

Description

The title of Gavin Douglas' translation "Eneados" is given in the heading of a manuscript at C ...

''. It was the first complete translation of a major classical text in an Anglian language, finished in 1513, but overshadowed by the disaster at Flodden

The Battle of Flodden, Flodden Field, or occasionally Branxton, (Brainston Moor) was a battle fought on 9 September 1513 during the War of the League of Cambrai between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, resulting in an English ...

that brought the reign to an end.

As a patron of poets and authors James V supported William Stewart and John Bellenden

John Bellenden or Ballantyne ( 1533–1587?) of Moray (why Moray, a lowland family) was a Scottish writer of the 16th century.

Life

He was born towards the close of the 15th century, and educated at St. Andrews and Paris.

At the request of ...

, who translated the Latin ''History of Scotland'' compiled in 1527 by Hector Boece

Hector Boece (; also spelled Boyce or Boise; 1465–1536), known in Latin as Hector Boecius or Boethius, was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and the first Principal of King's College in Aberdeen, a predecessor of the University of Abe ...

, into verse and prose.I. Brown, T. Owen Clancy, M. Pittock, S. Manning, eds, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union, until 1707'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 256–7. David Lyndsay

Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount (c. 1490 – c. 1555; ''alias'' Lindsay) was a Scottish herald who gained the highest heraldic office of Lyon King of Arms. He remains a well regarded poet whose works reflect the spirit of the Renaissance, speci ...

(c. 1486–1555), diplomat and the head of the Lyon Court

The Court of the Lord Lyon (the Lyon Court) is a standing court of law, based in New Register House in Edinburgh, which regulates heraldry in Scotland. The Lyon Court maintains the register of grants of arms, known as the Public Register of All ...

, was a prolific poet. He wrote elegiac narratives, romances and satires. George Buchanan

George Buchanan ( gd, Seòras Bochanan; February 1506 – 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth century Scotland produced." ...

(1506–82) had a major influence as a Latin poet, founding a tradition of neo-Latin poetry that would continue in to the seventeenth century.R. Mason, "Culture: 4 Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1660): general", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 120–3. Contributors to this tradition included royal secretary John Maitland (1537–95), reformer Andrew Melville

Andrew Melville (1 August 1545 – 1622) was a Scottish scholar, theologian, poet and religious reformer. His fame encouraged scholars from the European continent to study at Glasgow and St. Andrews.

He was born at Baldovie, on 1 August 154 ...

(1545–1622), John Johnston (1570?–1611) and David Hume of Godscroft

David Hume or Home of Godscroft (1558–1629) was a Scottish historian and political theorist, poet and controversialist, a major intellectual figure in Jacobean Scotland. It has been said that "Hume marks the culmination of the Scottish humani ...

(1558–1629).

From the 1550s, in the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots and the minority of her son James VI (r. 1567–1625), cultural pursuits were limited by the lack of a royal court and by political turmoil. The Kirk, heavily influenced by Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

, also discouraged poetry that was not devotional in nature. Nevertheless, poets from this period included courtier and minister Alexander Hume (c. 1556–1609), whose corpus of work includes nature poetry and epistolary verse. Alexander Scott's (?1520-82/3) use of short verse designed to be sung to music, opened the way for the Castalian poets of James VI's adult reign.

In the 1580s and 1590s James VI strongly promoted the literature of the country of his birth in Scots. His treatise, '' Some Rules and Cautions to be Observed and Eschewed in Scottish Prosody'', published in 1584 when he was aged 18, was both a poetic manual and a description of the poetic tradition in his mother tongue, to which he applied Renaissance principles. He became patron and member of a loose circle of Scottish Jacobean court poets and musicians, later called the Castalian Band

The Castalian Band is a modern name given to a grouping of Scottish Jacobean poets, or makars, which is said to have flourished between the 1580s and early 1590s in the court of James VI and consciously modelled on the French example of the P ...

, which included William Fowler (c. 1560–1612), John Stewart of Baldynneis (c. 1545–c. 1605), and Alexander Montgomerie

Alexander Montgomerie (Scottish Gaelic: Alasdair Mac Gumaraid) (c. 1550?–1598) was a Scottish Jacobean courtier and poet, or makar, born in Ayrshire. He was a Scottish Gaelic speaker and a Scots speaker from Ayrshire, an area which wa ...

(c. 1550–98). They translated key Renaissance texts and produced poems using French forms, including sonnets and short sonnets, for narrative, nature description, satire and meditations on love. Later poets that followed in this vein included William Alexander (c. 1567–1640), Alexander Craig (c. 1567–1627) and Robert Ayton (1570–1627). By the late 1590s the king's championing of his native Scottish tradition was to some extent diffused by the prospect of inheriting of the English throne.

Art

From the fifteenth century the records of the Scottish court contain references to artists. Matthew the "king's painter" is the first mentioned, said to be at Linlithgow in 1434. The most impressive works and artists were imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, generally considered the centre of painting in the

From the fifteenth century the records of the Scottish court contain references to artists. Matthew the "king's painter" is the first mentioned, said to be at Linlithgow in 1434. The most impressive works and artists were imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, generally considered the centre of painting in the Northern Renaissance

The Northern Renaissance was the Renaissance that occurred in Europe north of the Alps. From the last years of the 15th century, its Renaissance spread around Europe. Called the Northern Renaissance because it occurred north of the Italian Renais ...

. The products of these connections included Hugo van Der Goes

Hugo van der Goes (c. 1430/1440 – 1482) was one of the most significant and original Early Netherlandish painting, Flemish painters of the late 15th century. Van der Goes was an important painter of altarpieces as well as portraits. He introduce ...

's altarpiece for the Trinity College Church in Edinburgh, commissioned by James III, and the work after which the Flemish Master of James IV of Scotland is named. There are also a relatively large number of elaborate devotional books from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, usually produced in the Low Countries and France for Scottish patrons, including the Flemish illustrated book of hours, known as the '' Hours of James IV of Scotland'', given by James IV to Margaret Tudor

Margaret Tudor (28 November 1489 – 18 October 1541) was Queen of Scotland from 1503 until 1513 by marriage to King James IV. She then served as regent of Scotland during her son's minority, and successfully fought to extend her regency. Ma ...

and described as "perhaps the finest medieval manuscript to have been commissioned for Scottish use". Around 1500, about the same time as in England, Scottish monarchs turned to the recording of royal likenesses in panel portraits, painted in oils on wood, perhaps as a form of political expression. In 1502 James IV paid for delivery of portraits of the Tudor household, probably by the "Inglishe payntour" named "Mynours," who stayed in Scotland to paint the king and his new bride Margaret Tudor

Margaret Tudor (28 November 1489 – 18 October 1541) was Queen of Scotland from 1503 until 1513 by marriage to King James IV. She then served as regent of Scotland during her son's minority, and successfully fought to extend her regency. Ma ...

the following year.R. Tittler, "Portrait, politics and society", in R. Tittler and N. Jones, eds, ''A Companion to Tudor Britain'' (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2008), , p. 449. "Mynours" was Maynard Wewyck, a Flemish painter who usually worked for Henry VII in London. As in England, the monarchy may have had model portraits of royalty used for copies and reproductions, but the versions of native royal portraits that survive are generally crude by continental standards.Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community'', pp. 57–9.

The tradition of royal portrait painting in Scotland was disrupted by the minorities and regencies it underwent for much of the sixteenth century. In his majority James V was probably more concerned with architectural expressions of royal identity.R. Tittler, "Portrait, politics and society", in R. Tittler and N. Jones, eds, ''A Companion to Tudor Britain'' (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2008), , pp. 455–6. Mary Queen of Scots had been brought up in the French court, where she was drawn and painted by major European artists, but she did not commission any adult portraits, with the exception of the joint portrait with her second husband Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley (1546 – 10 February 1567), was an English nobleman who was the second husband of Mary, Queen of Scots, and the father of James VI of Scotland and I of England. Through his parents, he had claims to both the Scottis ...

. This may have reflected an historic Scottish pattern, where heraldic display or an elaborate tomb were considered more important than a portrait. There was an attempt to produce a series of portraits of Scottish kings in panel portraits, probably for the royal entry of the fifteen-year-old James VI in 1579, which are Medieval in form. In James VI's personal reign, Renaissance forms of portraiture began to dominate. He employed two Flemish artists, Arnold Bronckorst

Arnold Bronckhorst, or Bronckorst or Van Bronckhorst ( 1565–1583) was a Flemish or Dutch painter who was court painter to James VI of Scotland.Adrian Vanson

Adrian Vanson (died c. 1602) was court portrait painter to James VI of Scotland.

Family and artistic background

Adrian was probably born in Breda, the son of Willem Claesswen van Son by Kathelijn Adriaen Matheus de Blauwverversdochter. His uncle ...

from around 1584 to 1602, who have left a visual record of the king and major figures at the court.J. E. A. Dawson, ''Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 55–6.

Architecture

The royal centre at Forteviot was not in a defensive situation and there are no traces of any fortified enclosure. There is some archaeological evidence of artistic and architectural patronage on an impressive scale. The most notable piece of sculpture is the

The royal centre at Forteviot was not in a defensive situation and there are no traces of any fortified enclosure. There is some archaeological evidence of artistic and architectural patronage on an impressive scale. The most notable piece of sculpture is the Dupplin Cross

The Dupplin Cross is a carved, monumental Pictish stone, which dates from around 800 AD. It was first recorded by Thomas Pennant in 1769, on a hillside in Strathearn, a little to the north of (and on the opposite bank of the River Earn from) Forte ...

, found nearby and perhaps once part of the complex, but there are other fragments including the unique Forteviot Arch. Aerial photographs show that Forteviot was also the site of a major cemetery.

The introduction of feudalism into Scotland in the twelfth century led to the creation of baronial castles. There were also royal castles, often larger and providing defence, lodging for the itinerant Scottish court and a local administrative centre. By 1200 these included fortifications at Ayr

Ayr (; sco, Ayr; gd, Inbhir Àir, "Mouth of the River Ayr") is a town situated on the southwest coast of Scotland. It is the administrative centre of the South Ayrshire Subdivisions of Scotland, council area and the historic Shires of Scotlan ...

and Berwick. Alexander II (r. 1198–1249) and Alexander III (r. 1249–86) undertook a number of castle building projects in the modern style, but this phase of royal castle building came to an end with the early death of Alexander III that ushered in the Wars of Independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars

Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against for ...

.S. Reid, ''Castles and Tower Houses of the Scottish Clans, 1450–1650'' (Botley: Osprey, 2006), , p. 12.G. Stell, "War-damaged Castles: the evidence from Medieval Scotland," in ''Chateau Gaillard: Actes du colloque international de Graz (Autriche)'' (Caen, France: Publications du CRAHM, 2000), , p. 278.

Under the Stuart Dynasty there was a programme of extensive building and rebuilding of royal palaces. This probably began under James III, accelerated under James IV and reached its peak under James V. The influence of Renaissance architecture is reflected in these buildings. Linlithgow

Linlithgow (; gd, Gleann Iucha, sco, Lithgae) is a town in West Lothian, Scotland. It was historically West Lothian's county town, reflected in the county's historical name of Linlithgowshire. An ancient town, it lies in the Central Belt on a ...

was first constructed under James I (r. 1406–27), under the direction of master of work John de Waltoun and was referred to as a palace from 1429, apparently the first use of this term in the country. It was extended under James III and resembled a quadrangular, corner-towered Italian signorial palace or ''palatium ad moden castri'' (a castle-style palace), combining classical symmetry with neo-chivalric imagery. There is evidence that Italian masons were employed by James IV, in whose reign Linlithgow was completed and other palaces were rebuilt with Italianate proportions.M. Glendinning, R. MacInnes and A. MacKechnie, ''A History of Scottish Architecture: From the Renaissance to the Present Day'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), , p. 9.

In 1536 James V visited France for his marriage to Madeleine of Valois

Madeleine of France or Madeleine of Valois (10 August 1520 – 7 July 1537) was a French princess who briefly became Queen of Scotland in 1537 as the first wife of King James V. The marriage was arranged in accordance with the Treaty of Rouen ...

and would have come in contact with French Renaissance architecture

French Renaissance architecture is a style which was prominent between the late 15th and early 17th centuries in the Kingdom of France. It succeeded French Gothic architecture. The style was originally imported from Italy after the Hundred Years ...

. His second marriage to Mary of Guise two years later may have resulted in longer-term connections and influences.Thomas, "The Renaissance", p. 195. One multi-talented French wood-carver, furniture-maker, and metal-worker, Andrew Mansioun settled in Edinburgh and trained apprentices. Scottish architecture largely disregarded the insular style of England under Henry VIII and adopted forms that were recognisably European.Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community'', p. 5. Rather than slavishly copying continental forms, elements of these styles were integrated into traditional local patterns,Thomas, "The Renaissance", p. 189. and adapted to Scottish idioms and materials (particularly stone and harl

Harling is a rough-cast wall finish consisting of lime and aggregate, known for its rough texture. Many castles and other buildings in Scotland and Ulster have walls finished with harling. It is also used on contemporary buildings, where it pr ...

).D. M. Palliser, ''The Cambridge Urban History of Britain: 600–1540'', vol. 1'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), , pp. 391–2. The building at Linlithgow was followed by rebuilding at Holyrood Palace, Falkland Palace

Falkland Palace, in Falkland, Fife, Scotland, is a royal palace of the Scottish Kings. It was one of the favourite places of Mary, Queen of Scots, providing an escape from political and religious turmoil. Today it is under the stewardship of ...

, Stirling Castle and Edinburgh Castle, described by Roger Mason as "some of the finest examples of Renaissance architecture in Britain". Many of the building programs were planned and financed by James Hamilton of Finnart, Steward of the Royal Household

The Lord Steward or Lord Steward of the Household is an official of the Royal Household in England. He is always a peer. Until 1924, he was always a member of the Government. Until 1782, the office was one of considerable political importance ...

and Master of Works to James V.

From the mid-sixteenth century royal architectural work was much more limited. There were minor works were undertaken at Edinburgh Castle after the siege of 1575 and a viewing platform was added to Stirling Castle in the 1580s.M. Lynch, "Royal Court: 2 1542–1603", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 535–7. Work undertaken for James VI by William Schaw

William Schaw (c. 1550–1602) was Master of Works to James VI of Scotland for building castles and palaces, and is claimed to have been an important figure in the development of Freemasonry in Scotland.

Biography

William Schaw was the second ...

demonstrated continued Renaissance influences in the classical entrance of the Chapel Royal at Stirling, built in 1594.Thomas, "The Renaissance", pp. 201–2.

Finance

Lavish spending on luxurious clothing, fine foods, the patronage of innovative architecture, art and music can be seen from the reign of James I. James III is generally thought to have amassed a surplus and, despite his lavish spending, James IV was able to sustain his finances, probably thanks mainly to an increase in revenues from crown lands, the latter doubling his income from this source across his reign. James V was able to undertake lavish court spending due to two dowries from the King of France and his ability to exploit the wealth of the church, despite which spending kept pace with expanding income.J. E. A. Dawson, ''Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 138–9. Mary, Queen of Scots' attempt to create a court in the image the French Renaissance monarchy was hampered by financial limitations, intensified by the general price inflation of the period.

The court of James VI proved extremely expensive and may have provided one of the motivations for the attempted coup of the

Lavish spending on luxurious clothing, fine foods, the patronage of innovative architecture, art and music can be seen from the reign of James I. James III is generally thought to have amassed a surplus and, despite his lavish spending, James IV was able to sustain his finances, probably thanks mainly to an increase in revenues from crown lands, the latter doubling his income from this source across his reign. James V was able to undertake lavish court spending due to two dowries from the King of France and his ability to exploit the wealth of the church, despite which spending kept pace with expanding income.J. E. A. Dawson, ''Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 138–9. Mary, Queen of Scots' attempt to create a court in the image the French Renaissance monarchy was hampered by financial limitations, intensified by the general price inflation of the period.

The court of James VI proved extremely expensive and may have provided one of the motivations for the attempted coup of the Ruthven Raid

The Raid of Ruthven was a political conspiracy in Scotland which took place on 22 August 1582. It was composed of several Presbyterian nobles, led by William Ruthven, 1st Earl of Gowrie, who abducted King James VI of Scotland. The nobles intended ...

of 1582. After his marriage to Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and Queen of England and Ireland from the union of the Scottish and Eng ...

in 1589–90 spending in the court spiraled further out of control. Costume for the king and queen and favoured household servants came from an English subsidy gifted by Queen Elizabeth and managed by the goldsmith Thomas Foulis and the textile merchant Robert Jousie. Despite the money from England, by the closing months of 1591 the rising costs of both households prompted estimates and suggestions for cutting costs on food and costume, and increasing revenue from royal assets. The last of the queen's dowry, 54,000 Danish dalers, which had been loaned to several Scottish towns was spent on the elaborate court entertainment and masque for the baptism of Prince of Wales