Robert Owen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a

Robert Owen was born in Newtown, a small market town in

Robert Owen was born in Newtown, a small market town in

On a visit to Scotland, Owen met and fell in love with Ann (or Anne) Caroline Dale, daughter of

On a visit to Scotland, Owen met and fell in love with Ann (or Anne) Caroline Dale, daughter of

Until a series of

Until a series of

Owen embraced socialism in 1817, a turning point in his life, in which he pursued a "New View of Society". He outlined his position in a report to the committee of the

Owen embraced socialism in 1817, a turning point in his life, in which he pursued a "New View of Society". He outlined his position in a report to the committee of the

Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

and the cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted experimental socialistic communities, and sought a more collective approach to child rearing, including government control of education. He gained wealth in the early 1800s from a textile mill

Textile Manufacturing or Textile Engineering is a major industry. It is largely based on the conversion of fibre into yarn, then yarn into fabric. These are then dyed or printed, fabricated into cloth which is then converted into useful goods ...

at New Lanark

New Lanark is a village on the River Clyde, approximately 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometres) from Lanark, in Lanarkshire, and some southeast of Glasgow, Scotland. It was founded in 1785 and opened in 1786 by David Dale, who built cotton mills and hou ...

, Scotland. Having trained as a draper

Draper was originally a term for a retailer or wholesaler of cloth that was mainly for clothing. A draper may additionally operate as a cloth merchant or a haberdasher.

History

Drapers were an important trade guild during the medieval period, ...

in Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a town and civil parish in the South Kesteven District of Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2011 census was 19,701 and estimated at 20,645 in 2019. The town has 17th- and 18th-century stone buildings, older timber-framed ...

he worked in London before relocating aged 18 to Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

and textile manufacturing. In 1824, he moved to America and put most of his fortune in an experimental socialistic community at New Harmony, Indiana

New Harmony is a historic town on the Wabash River in Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana. It lies north of Mount Vernon, the county seat, and is part of the Evansville metropolitan area. The town's population was 789 at the 2010 census. ...

, as a preliminary for his Utopian society. It lasted about two years. Other Owenite

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative ...

communities also failed, and in 1828 Owen returned to London, where he continued to champion the working class, lead in developing cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

s and the trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

movement, and support child labour legislation and free co-educational schools.

Early life and education

Robert Owen was born in Newtown, a small market town in

Robert Owen was born in Newtown, a small market town in Montgomeryshire

, HQ= Montgomery

, Government= Montgomeryshire County Council (1889–1974)Montgomeryshire District Council (1974–1996)

, Origin=

, Status=

, Start=

, End= ...

, Wales, on 14 May 1771, to Anne (Williams) and Robert Owen. His father was a saddle

The saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals. It is not kno ...

r, ironmonger

Ironmongery originally referred, first, to the manufacture of iron goods and, second, to the place of sale of such items for domestic rather than industrial use. In both contexts, the term has expanded to include items made of steel, aluminium ...

and local postmaster; his mother was the daughter of a Newtown farming family. Young Robert was the sixth of the family's seven children, two of whom died at a young age. His surviving siblings were William, Anne, John and Richard.

Owen received little formal education, but he was an avid reader. He left school at the age of ten to be apprenticed to a Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a town and civil parish in the South Kesteven District of Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2011 census was 19,701 and estimated at 20,645 in 2019. The town has 17th- and 18th-century stone buildings, older timber-framed ...

draper

Draper was originally a term for a retailer or wholesaler of cloth that was mainly for clothing. A draper may additionally operate as a cloth merchant or a haberdasher.

History

Drapers were an important trade guild during the medieval period, ...

for four years. He also worked in London drapery shops in his teens. (online version) At about the age of 18, Owen moved to Manchester, where he spent the next twelve years of his life, employed initially at Satterfield's Drapery in Saint Ann's Square.

While in Manchester, Owen borrowed £100 from his brother William, so as to enter into a partnership to make spinning mule

The spinning mule is a machine used to spin cotton and other fibres. They were used extensively from the late 18th to the early 20th century in the mills of Lancashire and elsewhere. Mules were worked in pairs by a minder, with the help of tw ...

s, a new invention for spinning cotton thread, but exchanged his business share within a few months for six spinning mules that he worked in rented factory space. In 1792, when Owen was about 21 years old, mill-owner Peter Drinkwater

Peter Drinkwater (1750 – 15 November 1801) was an English cotton manufacturer and merchant.

Born in Whalley, Lancashire, he had a successful career as a fustian manufacturer using the domestic putting-out system, and as a merchant based in Bo ...

made him manager of the Piccadilly Mill

Piccadilly Mill, also known as Bank Top Mill or Drinkwater's Mill, owned by Peter Drinkwater, was the first cotton mill in Manchester, England, to be directly powered by a steam engine, and the 10th such mill in the world. Construction of the fou ...

at Manchester. However, after two years with Drinkwater, Owen voluntarily gave up a contracted promise of partnership, left the company, and went into partnership with other entrepreneurs to establish and later manage the Chorlton Twist Mills in Chorlton-on-Medlock

Chorlton-on-Medlock or Chorlton-upon-Medlock is an inner city area of Manchester, England.

Historically in Lancashire, Chorlton-on-Medlock is bordered to the north by the River Medlock, which runs immediately south of Manchester city centre ...

.

By the early 1790s, Owen's entrepreneurial spirit, management skills and progressive moral views were emerging. In 1793, he was elected a member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society

The Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, popularly known as the Lit. & Phil., is one of the oldest learned societies in the United Kingdom and second oldest provincial learned society (after the Spalding Gentlemen's Society).

Promine ...

, where the ideas of the Enlightenment were discussed. He also became a committee member of the Manchester Board of Health, instigated principally by Thomas Percival

Thomas Percival (29 September 1740 – 30 August 1804) was an English physician, health reformer, ethicist and author who wrote an early code of medical ethics. He drew up a pamphlet with the code in 1794 and wrote an expanded version in 18 ...

to press for improvements in the health and working conditions of factory workers.

Marriage and family

On a visit to Scotland, Owen met and fell in love with Ann (or Anne) Caroline Dale, daughter of

On a visit to Scotland, Owen met and fell in love with Ann (or Anne) Caroline Dale, daughter of David Dale

David Dale (6 January 1739–7 March 1806) was a leading Scottish industrialist, merchant and philanthropist during the Scottish Enlightenment period at the end of the 18th century. He was a successful entrepreneur in a number of areas, m ...

, a Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

philanthropist and the proprietor of the large New Lanark Mills. After their marriage on 30 September 1799, the Owens set up home in New Lanark, but later moved to Braxfield House in Lanark, Scotland .Estabrook, p. 64.

Robert and Caroline Owen had eight children, the first of whom died in infancy. Their seven survivors were four sons and three daughters: Robert Dale (1801–1877), William (1802–1842), Ann (or Anne) Caroline (1805–1831), Jane Dale (1805–1861), David Dale (1807–1860), Richard Dale (1809–1890) and Mary (1810–1832). Owen's four sons, Robert Dale, William, David Dale and Richard, and his daughter Jane Dale, followed their father to the United States, becoming US citizens and permanent residents in New Harmony, Indiana. Owen's wife Caroline and two of their daughters, Anne Caroline and Mary, remained in Britain, where they died in the 1830s.Estabrook, p. 72.Pitzer, "Why New Harmony is World Famous," in ''Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History'', p. 11.

New Lanark mill

In July 1799 Owen and his partners bought theNew Lanark

New Lanark is a village on the River Clyde, approximately 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometres) from Lanark, in Lanarkshire, and some southeast of Glasgow, Scotland. It was founded in 1785 and opened in 1786 by David Dale, who built cotton mills and hou ...

mill from David Dale, and Owen became its manager in January 1800. Encouraged by his management success in Manchester, Owen hoped to conduct the New Lanark mill on higher principles than purely commercial ones. It had been established in 1785 by David Dale and Richard Arkwright. Its water power provided by the falls of the River Clyde

The River Clyde ( gd, Abhainn Chluaidh, , sco, Clyde Watter, or ) is a river that flows into the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. It is the ninth-longest river in the United Kingdom, and the third-longest in Scotland. It runs through the major cit ...

turned its cotton-spinning operation into one of Britain's largest. About 2,000 individuals were involved, 500 of them children brought to the mill at the age of five or six from the poorhouses and charities of Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

and Glasgow. Dale, known for his benevolence, treated the children well, but the general condition of New Lanark residents was unsatisfactory, despite efforts by Dale and his son-in-law Owen to improve their workers' lives.John F. C. Harrison, "Robert Owen's Quest for the New Moral World in America," in

Many of the workers were from the lowest social levels: theft, drunkenness and other vices were common and education and sanitation neglected. Most families lived in one room. More respected people rejected the long hours and demoralising drudgery of the mills.

Until a series of

Until a series of Truck Acts

Truck Acts is the name given to legislation that outlaws truck systems, which are also known as "company store" systems, commonly leading to debt bondage. In England and Wales such laws date back to the 15th century.

History

The modern success ...

(1831–1887) required employers to pay their employees in common currency, many operated a truck system

Truck wages are wages paid not in conventional money but instead in the form of payment in kind (i.e. commodities, including goods and/or services); credit with retailers; or a money substitute, such as scrip, chits, vouchers or tokens. Truc ...

, paying workers wholly or in part with tokens that had no monetary value outside the mill owner's "truck shop", which charged high prices for shoddy goods. Unlike others, Owen's truck store offered goods at prices only slightly above their wholesale cost, passing on the savings from bulk purchases to his customers and placing alcohol sales under strict supervision. These principles became the basis for Britain's Co-operative shops, some of which continue trading in altered forms to this day.

Philosophy and influence

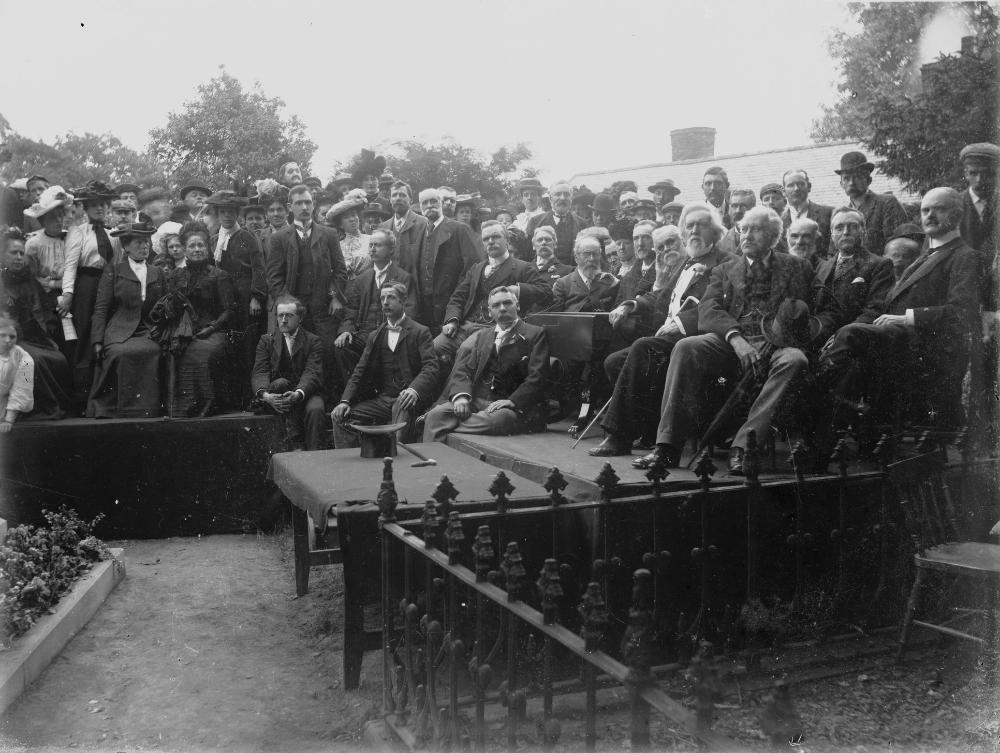

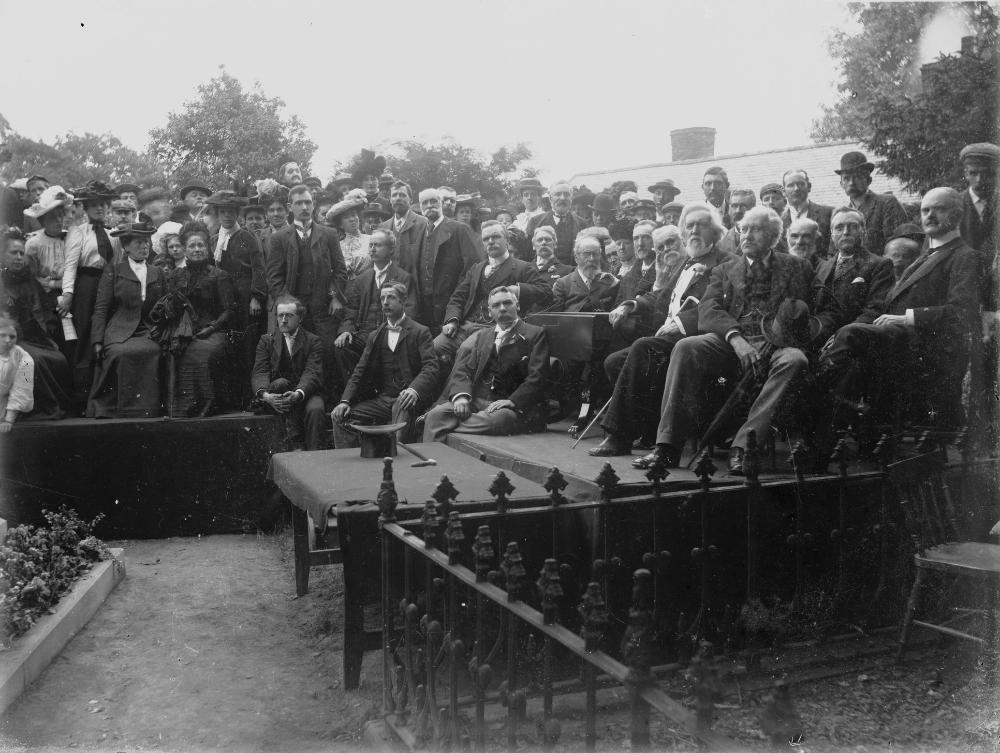

Owen tested his social and economic ideas at New Lanark, where he won his workers' confidence and continued to have success through the improved efficiency at the mill. The community also earned an international reputation. Social reformers, statesmen and royalty, including the future TsarNicholas I of Russia

Nicholas I , group=pron ( – ) was List of Russian rulers, Emperor of Russia, Congress Poland, King of Congress Poland and Grand Duke of Finland. He was the third son of Paul I of Russia, Paul I and younger brother of his predecessor, Alexander I ...

, visited New Lanark to study its methods. The opinions of many such visitors were favourable.Harrison, "Robert Owen's Quest for the New Moral World in America," in ''Robert Owen's American Legacy'', p. 37.

Owen's biggest success was in support of youth education and early child care. As a pioneer in Britain, notably Scotland, Owen provided an alternative to the "normal authoritarian approach to child education". Supporters of the methods argued that the manners of children brought up under his system were more graceful, genial and unconstrained; health, plenty and contentment prevailed; drunkenness was almost unknown and illegitimacy extremely rare. Owen's relations with his workers remained excellent and operations at the mill proceeded in a smooth, regular and commercially successful way.

However, some of Owen's schemes displeased his partners, forcing him to arrange for other investors to buy his share of the business in 1813, for the equivalent of US$800,000. The new investors, who included Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

and the well-known Quaker William Allen William Allen may refer to:

Politicians

United States

*William Allen (congressman) (1827–1881), United States Representative from Ohio

*William Allen (governor) (1803–1879), U.S. Representative, Senator, and 31st Governor of Ohio

*William ...

, were content to accept a £5,000 return on their capital. The ownership change also provided Owen with a chance to broaden his philanthropy, advocating improvements in workers' rights and child labour laws, and free education for children.

In 1813 Owen authored and published ''A New View of Society, or Essays on the Principle of the Formation of the Human Character'', the first of four essays he wrote to explain the principles behind his philosophy of socialistic reform. In this he writes:

Owen had originally been a follower of the classical liberal, utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

Jeremy Bentham, who believed that free markets, in particular the right of workers to move and choose their employers, would release workers from the excessive power of capitalists. However, Owen developed his own, pro-socialist outlook. In addition, Owen as a deist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

, criticised organised religion, including the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, and developed a belief system of his own.

Owen felt that human character is formed by conditions over which individuals have no control. Thus individuals could not be praised or blamed for their behaviour or situation in life. This principle led Owen to conclude that the correct formation of people's characters called for placing them under proper environmental influences – physical, moral and social – from their earliest years. These notions of inherent irresponsibility in humans and the effect of early influences on an individual's character formed the basis of Owen's system of education and social reform.

Relying on his own observations, experiences and thoughts, Owen saw his view of human nature as original and "the most basic and necessary constituent in an evolving science of society".Curti, "Robert Owen in American Thought," in ''Robert Owen's American Legacy'', p. 61. His philosophy was influenced by Sir Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

's views on natural law, and his views resembled those of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the ''Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promine ...

, Claude Adrien Helvétius

Claude Adrien Helvétius (; ; 26 January 1715 – 26 December 1771) was a French philosopher, freemason and ''littérateur''.

Life

Claude Adrien Helvétius was born in Paris, France, and was descended from a family of physicians, originally su ...

, William Godwin, John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

, James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote ''The History of Brit ...

, and Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

, among others. Owen did not have the direct influence of Enlightenment philosophers.

Owen's work at New Lanark continued to have significance in Britain and continental Europe. He was a "pioneer in factory reform, the father of distributive cooperation, and the founder of nursery schools." His schemes for educating his workers included opening an Institute for the Formation of Character at New Lanark in 1818. This and other programmes at New Lanark provided free education from infancy to adulthood. In addition, he zealously supported factory legislation that culminated in the Cotton Mills and Factories Act of 1819. Owen also had interviews and communications with leading members of the British government, including its premier, Robert Banks Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British Tory statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1812 to 1827. He held many important cabinet offices such as Foreign Secret ...

. He also met many of the rulers and leading statesmen of Europe.

Owen adopted new principles to raise the standard of goods his workers produced. A cube with faces painted in different colours was installed above each machinist's workplace. The colour of the face showed to all who saw it the quality and quantity of goods the worker completed. The intention was to encourage workers to do their best. Although it was no great incentive in itself, conditions at New Lanark for workers and their families were idyllic for the time.

Perhaps one of Robert Owen's most memorable ideas was his silent monitor method. Owen was opposed to common corporal punishment, therefore, to have some form of discipline he developed the "silent monitor". In his mills, he would hang a four-sided block each displaying a different color representing the behavior of the employee. The color for poor performance was black and he believed it aligned with the Scottish term 'black-affronted' meaning to be embarrassed. While the opposite being white to symbolize meritorious conduct. His strategy was successful as employees at the time cared about maintain a good relationship with Owen in order to leave a good impression on him, since he took a different approach to employees' regulation. This idea supports his overall thought that human nature is molded for better or worse by the environment. Owen had a significant impact on British socialism as well on unionism that helped him set an example for others. That no matter the background one has whether rich or poor one can always change the status quo and be unalike anyone before.

Owen grew to be known as a utopian socialist and his works are considered to reflect this attitude. Although he could be considered a member of the bourgeoisie his relationship with this class was often complicated. He fought to pass legislation that benefitted workers. He was an advocate for the Factory Act of 1819. He supported socialist ideas so his views did not have immediate impact in Britain or the United States.

Eight-hour day

Owen raised the demand for aneight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

in 1810 and set about instituting the policy at New Lanark

New Lanark is a village on the River Clyde, approximately 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometres) from Lanark, in Lanarkshire, and some southeast of Glasgow, Scotland. It was founded in 1785 and opened in 1786 by David Dale, who built cotton mills and hou ...

. By 1817 he had formulated the goal of an eight-hour working day with the slogan "eight hours labour, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest".

Models for socialism (1817)

Owen embraced socialism in 1817, a turning point in his life, in which he pursued a "New View of Society". He outlined his position in a report to the committee of the

Owen embraced socialism in 1817, a turning point in his life, in which he pursued a "New View of Society". He outlined his position in a report to the committee of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

on the country's Poor Laws. As misery and trade stagnation after the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

drew national attention, the government called on Owen for advice on how to alleviate the industrial concerns. Although he ascribed the immediate misery to the wars, he saw as the underlying cause competition of human labour with machinery, and recommended setting up self-sufficient communities.

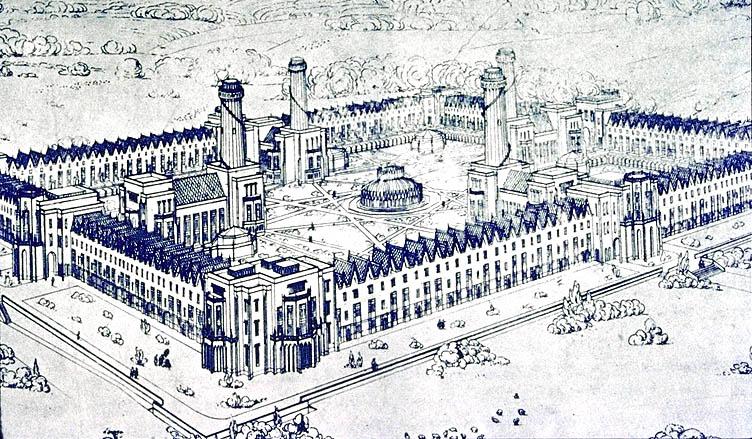

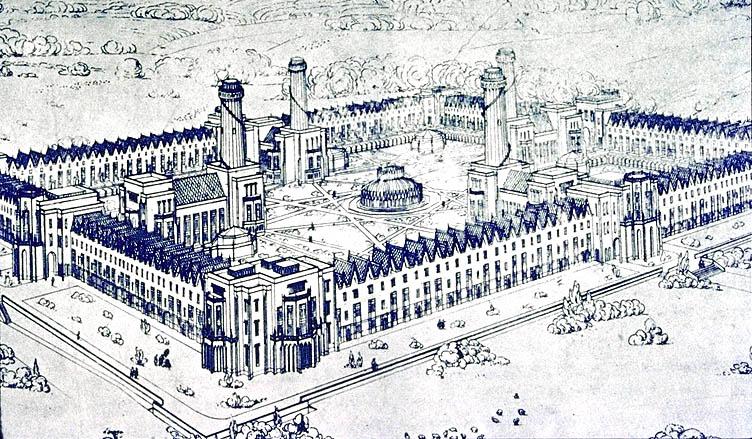

Owen proposed that communities of some 1,200 people should settle on land from , all living in one building with a public kitchen and dining halls. (The proposed size may have been influenced by the size of the village of New Lanark.) Owen also proposed that each family have its own private apartments and the responsibility for the care of its children up to the age of three. Thereafter children would be raised by the community, but their parents would have access to them at mealtimes and on other occasions. Owen further suggested that such communities be established by individuals, parishes, counties

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

, or other governmental units. In each case there would be effective supervision by qualified persons. Work and enjoyment of its results should be experienced communally. Owen believed his idea would be the best way to reorganise society in general, and called his vision the "New Moral World".

Owen's utopian model changed little in his lifetime. His developed model envisaged an association of 500–3,000 people as the optimum for a working community. While mainly agricultural, it would possess the best machinery, offer varied employment, and as far as possible be self-contained. Owen went on to explain that as such communities proliferated, "unions of them federatively united shall be formed in circle of tens, hundreds and thousands", linked by common interest.

Arguments against Owen and his answers

Owen hoped for a better and harmonious environment which promoted mutual respect, love and moral values. He believed everyone would have a good education and a better living condition in order to live righteously. He valued social and educational reforms for the middle class and rejected the capitalist power which elevated the powerful figures at the expense of others. Regardless of his adversaries' attacks, he remained persuasive of his goals. Owen funded kids' schools, and advocated for free education, equal rights and freedom. He participated in legislation to improve laborers' wage and working conditions. Owen's project was considered unachievable because he did not clearly establish a guideline that stipulated the administration of properties and the conditions of memberships. As a result, some critics found his plans unsatisfactory and ineffective because the overpopulation and shortage of supply created antagonism within the community. Owen's opponents view him as a dictator, and a blasphemer of Christianity because he rejected sacred beliefs and defied anyone who differed from his views. Owen perceived religion as a source of fear and ignorance. Therefore, people were unable to think rationally if they stayed attached to "fallacious testimonies" of religion. Owen believed compassion, kindness and solidarity corrected bad habits, encouraged self-disciple and enhanced a person's attitude. Force oppressed people and affect their mental health. Unless people were educated in a proper environment, obtained equal opportunities of job and maintained social norms, differences between labor classes, conflicts, and inequalities will persist just as in the British colonies. Without making any changes in the national institutions, he believed that even reorganizing the working classes would bring great benefits. So he opposed the views of radicals seeking to change in the public mentality by expanding voting rights. Other notable critics of Owen includeKarl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' ''Capital'', that it is the working class that are responsible for creating the unparalleled wealth in capitalist societies. Similarly, Owen also recognized that under the existing economic system, the working class did not automatically receive the benefits of that newly created wealth. Marx and Engels, differentiated, however, their own scientific conception of socialism from Owen's societies. They argued that Owen's plan, to create a model socialist utopia to coexist with contemporary society and prove its superiority over time, was insufficient to create a new society. In their view, Owen's "socialism" was utopian, since to Owen and the other utopian socialists " cialism is the expression of absolute truth, reason and justice, and has only to be discovered to conquer all the world by virtue of its own power." Marx and Engels believed that the overthrow of the capitalist system could only occur once the working class was organized into a revolutionary socialist political party of the working class that was completely independent of all capitalist class influence whereas the utopians sought the assistance and the co-operation of the capitalists in order to achieve the transition to socialism.

To test the viability of his ideas for self-sufficient working communities, Owen began experimenting in communal living in America in 1825. Among the most famous efforts was the one set up at New Harmony, Indiana. Of the 130 identifiable communitarian experiments in America before the

To test the viability of his ideas for self-sufficient working communities, Owen began experimenting in communal living in America in 1825. Among the most famous efforts was the one set up at New Harmony, Indiana. Of the 130 identifiable communitarian experiments in America before the

Although Owen made further brief visits to the United States, London became his permanent home and the centre of his work in 1828. After extended friction with William Allen and some other business partners, Owen relinquished all connections with New Lanark. He is often quoted in a comment by Allen at the time, "All the world is queer save thee and me, and even thou art a little queer". Having invested most of his fortune in the failed New Harmony communal experiment, Owen was no longer a wealthy capitalist. However, he remained the head of a vigorous propaganda effort to promote industrial equality, free education for children and adequate living conditions in factory towns, while delivering lectures in Europe and publishing a weekly newspaper to gain support for his ideas.

In 1832 Owen opened the

Although Owen made further brief visits to the United States, London became his permanent home and the centre of his work in 1828. After extended friction with William Allen and some other business partners, Owen relinquished all connections with New Lanark. He is often quoted in a comment by Allen at the time, "All the world is queer save thee and me, and even thou art a little queer". Having invested most of his fortune in the failed New Harmony communal experiment, Owen was no longer a wealthy capitalist. However, he remained the head of a vigorous propaganda effort to promote industrial equality, free education for children and adequate living conditions in factory towns, while delivering lectures in Europe and publishing a weekly newspaper to gain support for his ideas.

In 1832 Owen opened the

In 1817, Owen publicly claimed that all religions were false. In 1854, aged 83, Owen converted to

In 1817, Owen publicly claimed that all religions were false. In 1854, aged 83, Owen converted to

Although he had spent most of his life in England and Scotland, Owen returned to his native town of Newtown at the end of his life. He died there on 17 November 1858 and was buried there on 21 November. He died penniless apart from an annual income drawn from a trust established by his sons in 1844.

Owen was a reformer, philanthropist, community builder, and spiritualist who spent his life seeking to improve the lives of others. An advocate of the working class, he improved working conditions for factory workers, which he demonstrated at New Lanark, Scotland, became a leader in trade unionism, promoted social equality through his experimental Utopian communities, and supported the passage of child labour laws and free education for children. In these reforms he was ahead of his time. He envisioned a

Although he had spent most of his life in England and Scotland, Owen returned to his native town of Newtown at the end of his life. He died there on 17 November 1858 and was buried there on 21 November. He died penniless apart from an annual income drawn from a trust established by his sons in 1844.

Owen was a reformer, philanthropist, community builder, and spiritualist who spent his life seeking to improve the lives of others. An advocate of the working class, he improved working conditions for factory workers, which he demonstrated at New Lanark, Scotland, became a leader in trade unionism, promoted social equality through his experimental Utopian communities, and supported the passage of child labour laws and free education for children. In these reforms he was ahead of his time. He envisioned a

*The Co-operative Movement erected a monument to Robert Owen in 1902 at his burial site in Newtown, Montgomeryshire.

*The Welsh people donated a bust of Owen by Welsh sculptor Sir

*The Co-operative Movement erected a monument to Robert Owen in 1902 at his burial site in Newtown, Montgomeryshire.

*The Welsh people donated a bust of Owen by Welsh sculptor Sir

A New View of Society and Other Writings

', introduction by G. D. H. Cole. London and New York: J. M. Dent & Sons, E. P. Dutton and Co., 1927 *''A New View of Society and Other Writings'', G. Claeys, ed. London and New York: Penguin Books, 1991 *''The Selected Works of Robert Owen'', G. Claeys, ed., 4 vols. London: Pickering and Chatto, 1993 Archival collections: *Robert Owen Collection, National Co-operative Archive, United Kingdom. *New Harmony, Indiana, Collection, 1814–1884, 1920, 1964,

Robert Owen, the Founder of Socialism in England

' (London, 1869) *G. D. H. Cole,

Life of Robert Owen

'. London, Ernest Benn Ltd., 1925; second edition Macmillan, 1930 *

The Life, Times, and Labours of Robert Owen

'. London, 1889 *A. L. Morton,

The Life and Ideas of Robert Owen

'. New York, International Publishers, 1969 *W. H. Oliver, "Robert Owen and the English Working-Class Movements", ''History Today'' (November 1958) 8–11, pp. 787–796 *F. A. Packard,

Life of Robert Owen

'. Philadelphia: Ashmead & Evans, 1866 *

Robert Owen: A Biography

'. London: Hutchinson and Company, 1906 *David Santilli, ''Life of the Mill Man''. London, B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1987 * William Lucas Sargant,

Robert Owen and his social philosophy

'. London, 1860 *Richard Tames, ''Radicals, Railways & Reform''. London, B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1986

Robert Owen: Aspects of his Life and Work

'. Humanities Press, 1971 * *Gregory Claeys, ''Citizens and Saints. Politics and Anti-Politics in Early British Socialism''. Cambridge University Press, 1989 *

The Life of Robert Owen, Philanthropist and Social Reformer, An Appreciation

'. Robert Sutton, 1907 *R. E. Davis and F. J. O'Hagan, ''Robert Owen''. London: Continuum Press, 2010 *E. Dolleans,

Robert Owen

'. Paris, 1905 *I. Donnachie, ''Robert Owen. Owen of New Lanark and New Harmony''. 2000 * Auguste Marie Fabre,

Un Socialiste Pratique, Robert Owen

'. Nìmes, Bureaux de l'Émancipation, 1896 * John F. C. Harrison, ''Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America: Quest for the New Moral World''. New York, 1969 *

The History of Co-operation in England: Its Literature and Its Advocates

' V. 1. London, 1906 *G. J. Holyoake,

The History of Co-operation in England: Its Literature and Its Advocates

' V. 2. London, 1906 *The National Library of Wales,

A Bibliography of Robert Owen, The Socialist

'. 1914 * *H. Simon, ''Robert Owen: Sein Leben und Seine Bedeutung für die Gegenwart''. Jena, 1905 *O. Siméon,

Robert Owen's Experiment at New Lanark. From Paternalism to Socialism

'. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017

at the Marxists Internet Archive

Brief biography at the New Lanark World Heritage Site

The Robert Owen Museum

Newtown, Wales

Video of Owen's wool mill

"Robert Owen and the Co-operative movement"

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Owen, Robert 1771 births 1858 deaths British cooperative organizers European democratic socialists Founders of utopian communities People from Newtown, Powys Owenites Utopian socialists Welsh agnostics Welsh humanists 19th-century Welsh businesspeople 18th-century Welsh businesspeople Welsh business theorists Welsh philanthropists Welsh socialists British social reformers Socialist economists

'' ''Capital'', that it is the working class that are responsible for creating the unparalleled wealth in capitalist societies. Similarly, Owen also recognized that under the existing economic system, the working class did not automatically receive the benefits of that newly created wealth. Marx and Engels, differentiated, however, their own scientific conception of socialism from Owen's societies. They argued that Owen's plan, to create a model socialist utopia to coexist with contemporary society and prove its superiority over time, was insufficient to create a new society. In their view, Owen's "socialism" was utopian, since to Owen and the other utopian socialists " cialism is the expression of absolute truth, reason and justice, and has only to be discovered to conquer all the world by virtue of its own power." Marx and Engels believed that the overthrow of the capitalist system could only occur once the working class was organized into a revolutionary socialist political party of the working class that was completely independent of all capitalist class influence whereas the utopians sought the assistance and the co-operation of the capitalists in order to achieve the transition to socialism.

Community experiments

To test the viability of his ideas for self-sufficient working communities, Owen began experimenting in communal living in America in 1825. Among the most famous efforts was the one set up at New Harmony, Indiana. Of the 130 identifiable communitarian experiments in America before the

To test the viability of his ideas for self-sufficient working communities, Owen began experimenting in communal living in America in 1825. Among the most famous efforts was the one set up at New Harmony, Indiana. Of the 130 identifiable communitarian experiments in America before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, at least 16 were Owenite

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative ...

or Owenite-influenced. New Harmony was Owen's earliest and most ambitious of these.

Owen and his son William sailed to America in October 1824 to establish an experimental community in Indiana. In January 1825 Owen used a portion of his own funds to purchase an existing town of 180 buildings and several thousand acres of land along the Wabash River in Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

. George Rapp

John George Rapp (german: Johann Georg Rapp; November 1, 1757 in Iptingen, Duchy of Württemberg – August 7, 1847 in Economy, Pennsylvania) was the founder of the religious sect called Harmonists, Harmonites, Rappites, or the Harmony Society ...

's Harmony Society

The Harmony Society was a Christian theosophy and pietist society founded in Iptingen, Germany, in . Due to religious persecution by the Lutheran Church and the government in Württemberg, the group moved to the United States,Robert Paul Sutto ...

, the religious group that owned the property and had founded the communal village of Harmony (or Harmonie) on the site in 1814, decided in 1824 to relocate to Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. Owen renamed it New Harmony and made the village his preliminary model for a Utopian community.

Owen sought support for his socialist vision among American thinkers, reformers, intellectuals and public statesmen. On 25 February and 7 March 1825, Owen gave addresses in the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

to the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

and others in the US government, outlining his vision for the Utopian community at New Harmony, and his socialist beliefs. The audience for his ideas included three former U.S. presidents

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term

Term may refer to:

* Terminology, or term, a noun or compound word used in a specific context, in pa ...

– John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, and James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

) – the outgoing US President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

, and the President-elect, John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

. His meetings were perhaps the first discussions of socialism in the Americas; they were certainly a big step towards discussion of it in the United States. Owenism

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative m ...

, among the first socialist ideologies active in the United States, can be seen as an instigator of the later socialist movement.

Owen convinced William Maclure

William Maclure (27 October 176323 March 1840) was an Americanized Scottish geologist, cartographer and philanthropist. He is known as the 'father of American geology'. As a social experimenter on new types of community life, he collaborated ...

, a wealthy Scottish scientist and philanthropist living in Philadelphia to join him at New Harmony and become his financial partner. Maclure's involvement went on to attract scientists, educators and artists such as Thomas Say

Thomas Say (June 27, 1787 – October 10, 1834) was an American entomologist, conchologist, and herpetologist. His studies of insects and shells, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Georgia, the R ...

, Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, and Madame Marie Duclos Fretageot. These helped to turn the New Harmony community into a centre for educational reform, scientific research and artistic expression. See also:

Although Owen sought to build a "Village of Unity and Mutual Cooperation" south of the town, his grand plan was never fully realised and he returned to Britain to continue his work. During his long absences from New Harmony, Owen left the experiment under the day-to-day management of his sons, Robert Dale Owen and William Owen, and his business partner, Maclure. However, New Harmony proved to be an economic failure, lasting about two years, although it had attracted over a thousand residents by the end of its first year. The socialistic society was dissolved in 1827, but many of its scientists, educators, artists and other inhabitants, including Owen's four sons, Robert Dale, William, David Dale, and Richard Dale Owen, and his daughter Jane Dale Owen Fauntleroy, remained at New Harmony after the experiment ended.

Other experiments in the United States included communal settlements at Blue Spring, near Bloomington, Indiana, at Yellow Springs, Ohio, and at Forestville Commonwealth at Earlton, New York, as well as other projects in New York, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, and Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

. Nearly all of these had ended before New Harmony was dissolved in April 1827.

Owen's Utopian communities attracted a mix of people, many with the highest aims. They included vagrants, adventurers and other reform-minded enthusiasts. In the words of Owen's son David Dale Owen, they attracted "a heterogeneous collection of Radicals", "enthusiastic devotees to principle," and "honest latitudinarians, and lazy theorists," with "a sprinkling of unprincipled sharpers thrown in."

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

, a participant at New Harmony, asserted that it was doomed to failure for lack of individual sovereignty and personal property. In describing the community, Warren explained: "We had a world in miniature – we had enacted the French revolution over again with despairing hearts instead of corpses as a result.... It appeared that it was nature's own inherent law of diversity that had conquered us... our 'united interests' were directly at war with the individualities of persons and circumstances and the instinct of self-preservation...." Warren's observations on the reasons for the community's failure led to the development of American individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism in the United States was strongly influenced by Benjamin Tucker, Josiah Warren, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Lysander Spooner, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Max Stirner, Herbert Spencer and Henry David Thoreau. Other important individua ...

, of which he was its original theorist. Some historians have traced the demise of New Harmony to serial disagreements among its members.Estabrook, p. 68.

Social experiments also began in Scotland in 1825, when Abram Combe

Abram Combe (15 January 1785–11 August 1827) was a British utopian socialist, an associate of Robert Owen and a major figure in the early co-operative movement, leading one of the earliest Owenite communities, at Orbiston, Scotland.

Life Earl ...

, an Owenite, attempted a utopian experiment at Orbiston, near Glasgow, but this failed after about two years. In the 1830s, additional experiments in socialistic cooperatives were made in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and Britain, the most important being at Ralahine

Ralahine ''( Irish, Ráth Fhlaithín)'' is a townland of County Clare, it is best known for its historic and extraordinary experiment in communism in 1831, long before communism, as we have come to know it, became a reality.

The Ralahine Commune ...

, established in 1831 in County Clare

County Clare ( ga, Contae an Chláir) is a county in Ireland, in the Southern Region and the province of Munster, bordered on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. Clare County Council is the local authority. The county had a population of 118,81 ...

, Ireland, and at Tytherley, begun in 1839 in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

, England. The former proved a remarkable success for three-and-a-half years until the proprietor, having ruined himself by gambling, had to sell his interest. Tytherley, known as Harmony Hall or Queenwood College

Queenwood College was a British Public School, that is an independent fee-paying school, situated near Stockbridge, Hampshire, England. The school was in operation from 1847 to 1896.

History of the site

In 1335 Edward III gave the Manor of East ...

, was designed by the architect Joseph Hansom. This also failed. Another social experiment, Manea Colony Manea may refer to:

* Manea, Cambridgeshire, a village in the District of Fenland, Cambridgeshire, England

* Manea (name), both a surname and a given name

* MANEA, an enzyme

* Manea River, a tributary of the Crasna River in Romania

* a singular ...

in the Isle of Ely

The Isle of Ely () is a historic region around the city of Ely in Cambridgeshire, England. Between 1889 and 1965, it formed an administrative county.

Etymology

Its name has been said to mean "island of eels", a reference to the creatures th ...

, Cambridgeshire, launched in the late 1830s by William Hodson, likewise an Owenite, but it failed in a couple of years and Hodson emigrated to the United States. The Manea Colony site has been excavated by Cambridge Archaeology Unit (CAU) based at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

.

Return to Britain

Although Owen made further brief visits to the United States, London became his permanent home and the centre of his work in 1828. After extended friction with William Allen and some other business partners, Owen relinquished all connections with New Lanark. He is often quoted in a comment by Allen at the time, "All the world is queer save thee and me, and even thou art a little queer". Having invested most of his fortune in the failed New Harmony communal experiment, Owen was no longer a wealthy capitalist. However, he remained the head of a vigorous propaganda effort to promote industrial equality, free education for children and adequate living conditions in factory towns, while delivering lectures in Europe and publishing a weekly newspaper to gain support for his ideas.

In 1832 Owen opened the

Although Owen made further brief visits to the United States, London became his permanent home and the centre of his work in 1828. After extended friction with William Allen and some other business partners, Owen relinquished all connections with New Lanark. He is often quoted in a comment by Allen at the time, "All the world is queer save thee and me, and even thou art a little queer". Having invested most of his fortune in the failed New Harmony communal experiment, Owen was no longer a wealthy capitalist. However, he remained the head of a vigorous propaganda effort to promote industrial equality, free education for children and adequate living conditions in factory towns, while delivering lectures in Europe and publishing a weekly newspaper to gain support for his ideas.

In 1832 Owen opened the National Equitable Labour Exchange

In economics, a time-based currency is an alternative currency or exchange system where the unit of account is the person-hour or some other time unit. Some time-based currencies value everyone's contributions equally: one hour equals one service ...

system, a time-based currency

In economics, a time-based currency is an alternative currency or exchange system where the unit of account is the person-hour or some other time unit. Some time-based currencies value everyone's contributions equally: one hour equals one service ...

in which the exchange of goods was effected by means of labour notes; this system superseded the usual means of exchange and middlemen. The London exchange continued until 1833, a Birmingham branch operating for just a few months until July 1833. Owen also became involved in trade unionism, briefly leading the Grand National Consolidated Trade Union (GNCTU) before its collapse in 1834.

Socialism first became current in British terminology in discussions of the Association of all Classes of all Nations

The Grand National Consolidated Trades Union of 1834 was an early attempt to form a national union confederation in the United Kingdom.

There had been several attempts to form national general unions in the 1820s, culminating with the National A ...

, which Owen formed in 1835 and served as its initial leader. Owen's secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

views also gained enough influence among the working classes to cause the ''Westminster Review

The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the liberal journal unt ...

'' to comment in 1839 that his principles were the creed of many of them. However, by 1846, the only lasting result of Owen's agitation for social change, carried on through public meetings, pamphlets, periodicals, and occasional treatises, remained the Co-operative movement, and for a time even that seemed to have collapsed.

Role in spiritualism

In 1817, Owen publicly claimed that all religions were false. In 1854, aged 83, Owen converted to

In 1817, Owen publicly claimed that all religions were false. In 1854, aged 83, Owen converted to spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and Mind-body dualism, dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (w ...

after a series of sittings with Maria B. Hayden, an American medium credited with introducing spiritualism to England. He made a public profession of his new faith in his publication ''The Rational Quarterly Review'' and in a pamphlet titled ''The future of the Human race; or great glorious and future revolution to be effected through the agency of departed spirits of good and superior men and women''.

Owen claimed to have had medium contact with spirits of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

and others. He explained that the purpose of these was to change "the present, false, disunited and miserable state of human existence, for a true, united and happy state... to prepare the world for universal peace, and to infuse into all the spirit of charity, forbearance and love."

Spiritualists

Spiritualism is the metaphysics, metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and Mind-body dualism, dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spir ...

claimed after Owen's death that his spirit had dictated to the medium Emma Hardinge Britten

Emma Hardinge Britten (2 May 1823 – 2 October 1899) was an English advocate for the early Modern Spiritualist Movement. Much of her life and work was recorded and published in her speeches and writing and an incomplete autobiography edite ...

in 1871 the " Seven Principles of Spiritualism", used by their National Union as "the basis of its religious philosophy".

Death and legacy

As Owen grew older and more radical in his views, his influence began to decline.Estabrook, p. 68. Owen published his memoirs, ''The Life of Robert Owen'', in 1857, a year before his death. Although he had spent most of his life in England and Scotland, Owen returned to his native town of Newtown at the end of his life. He died there on 17 November 1858 and was buried there on 21 November. He died penniless apart from an annual income drawn from a trust established by his sons in 1844.

Owen was a reformer, philanthropist, community builder, and spiritualist who spent his life seeking to improve the lives of others. An advocate of the working class, he improved working conditions for factory workers, which he demonstrated at New Lanark, Scotland, became a leader in trade unionism, promoted social equality through his experimental Utopian communities, and supported the passage of child labour laws and free education for children. In these reforms he was ahead of his time. He envisioned a

Although he had spent most of his life in England and Scotland, Owen returned to his native town of Newtown at the end of his life. He died there on 17 November 1858 and was buried there on 21 November. He died penniless apart from an annual income drawn from a trust established by his sons in 1844.

Owen was a reformer, philanthropist, community builder, and spiritualist who spent his life seeking to improve the lives of others. An advocate of the working class, he improved working conditions for factory workers, which he demonstrated at New Lanark, Scotland, became a leader in trade unionism, promoted social equality through his experimental Utopian communities, and supported the passage of child labour laws and free education for children. In these reforms he was ahead of his time. He envisioned a communal society

An intentional community is a voluntary residential community which is designed to have a high degree of social cohesion and teamwork from the start. The members of an intentional community typically hold a common social, political, religious, ...

that others could consider and apply as they wished. In ''Revolution in the Mind and Practice of the Human Race'' (1849), he went on to say that character is formed by a combination of Nature or God and the circumstances of the individual's experience. Citing beneficial results at New Lanark, Scotland, during 30 years of work there, Owen concluded that a person's "character is not made ''by'', but ''for'' the individual," and that nature and society are responsible for each person's character and conduct.

Owen's agitation for social change, along with the work of the Owenites and of his own children, helped to bring lasting social reforms in women's and workers' rights, establish free public libraries and museums, child care and public, co-educational schools, and pre-Marxian communism, and develop the Co-operative and trade union movements. New Harmony, Indiana, and New Lanark, Scotland, two towns with which he is closely associated, remain as reminders of his efforts.

Owen's legacy of public service continued with his four sons, Robert Dale, William, David Dale, and Richard Dale, and his daughter, Jane, who followed him to America to live at New Harmony, Indiana:

*Robert Dale Owen

Robert Dale Owen (7 November 1801 – 24 June 1877) was a Scottish-born Welsh social reformer who immigrated to the United States in 1825, became a U.S. citizen, and was active in Indiana politics as member of the Democratic Party in the Ind ...

(1801–1877), an able exponent of his father's doctrines, managed the New Harmony community after his father returned to Britain in 1825. He wrote articles and co-edited with Frances Wright

Frances Wright (September 6, 1795 – December 13, 1852), widely known as Fanny Wright, was a Scottish-born lecturer, writer, freethinker, feminist, utopian socialist, abolitionist, social reformer, and Epicurean philosopher, who became ...

the ''New-Harmony Gazette'' in the late 1820s in Indiana and the ''Free Enquirer'' in the 1830s in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Owen returned to New Harmony in 1833 and became active in Indiana politics. He was elected to the Indiana House of Representatives (1836–1839 and 1851–1853) and U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

(1843–1847), and was appointed chargé d'affaires in Naples in 1853–1858. While serving as a member of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, he drafted and helped to secure passage of a bill founding the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

in 1846. He was elected a delegate to the Indiana Constitutional Convention in 1850,Estabrook, pp. 72–74. and argued in support of widows and married women's property and divorce rights. He also favoured legislation for Indiana's tax-supported public school system. Like his father, he believed in spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and Mind-body dualism, dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (w ...

, authoring two books on the subject: ''Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World'' (1859) and ''The Debatable Land Between this World and the Next'' (1872).

*William Owen (1802–1842) moved to the United States with his father in 1824. His business skill, notably his knowledge of cotton-goods manufacturing, allowed him to remain at New Harmony after his father returned to Scotland, and serve as adviser to the community. He organised New Harmony's Thespian Society in 1827, but died of unknown causes at the age of 40.

*Jane Dale Owen Fauntleroy (1805–1861) arrived in the United States in 1833 and settled in New Harmony. She was a musician and educator who set up a school in her home. In 1835 she married Robert Henry Fauntleroy, a civil engineer from Virginia living at New Harmony.

*David Dale Owen

David Dale Owen (24 June 1807 – 13 November 1860) was a prominent American geologist who conducted the first geological surveys of Indiana, Kentucky, Arkansas, Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota. Owen served as the first state geologist for three sta ...

(1807–1860) moved to the United States in 1827 and resided at New Harmony for several years. He trained as a geologist and natural scientist and earned a medical degree. He was appointed a United States geologist in 1839. His work included geological surveys in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

, more specifically the states of Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, and Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

, as well as Minnesota Territory

The Territory of Minnesota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1849, until May 11, 1858, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Minnesota and west ...

. His brother Richard succeeded him as state geologist of Indiana.Leopold, ''Robert Dale Owen, A Biography'', pp. 50–51.

* Richard Dale Owen (1810–1890) emigrated to the United States in 1827 and joined his siblings at New Harmony. He fought in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

in 1847, taught natural science at Western Military Institute in Tennessee in 1849–1859, and earned a medical degree in 1858. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

he was a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

in the Union army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

and served as a commandant of Camp Morton, a prisoner-of-war camp for Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

soldiers at Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, Indiana. After the war, Owen served as Indiana's second state geologist. In addition, he was a professor at Indiana University

Indiana University (IU) is a system of public universities in the U.S. state of Indiana.

Campuses

Indiana University has two core campuses, five regional campuses, and two regional centers under the administration of IUPUI.

*Indiana Universi ...

and chaired its natural science department in 1864–1879. He helped plan Purdue University

Purdue University is a public land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded in 1869 after Lafayette businessman John Purdue donated land and money ...

and was appointed its first president in 1872–1874, but resigned before its classes began and resumed teaching at Indiana University. He spent his retirement years on research and writing.

Honours and tributes

*The Co-operative Movement erected a monument to Robert Owen in 1902 at his burial site in Newtown, Montgomeryshire.

*The Welsh people donated a bust of Owen by Welsh sculptor Sir

*The Co-operative Movement erected a monument to Robert Owen in 1902 at his burial site in Newtown, Montgomeryshire.

*The Welsh people donated a bust of Owen by Welsh sculptor Sir William Goscombe John

Sir William Goscombe John (21 February 1860 – 15 December 1952) was a prolific Welsh sculptor known for his many public memorials. As a sculptor, John developed a distinctive style of his own while respecting classical traditions and forms of ...

to the International Labour Office library in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

.

*Manchester has a statue of Owen at Balloon and Commercial StreetSelected published works

*''A New View of Society: Or, Essays on the Formation of Human Character, and the Application of the Principle to Practice'' (London, 1813). Retitled, ''A New View of Society: Or, Essays on the Formation of Human Character Preparatory to the Development of a Plan for Gradually Ameliorating the Condition of Mankind'', for second edition, 1816 *''Observations on the Effect of the Manufacturing System''. London, 1815 *''Report to the Committee of the Association for the Relief of the Manufacturing and Labouring Poor'' (1817) *''Two Memorials on Behalf of the Working Classes'' (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1818) *''An Address to the Master Manufacturers of Great Britain: On the Present Existing Evils in the Manufacturing System'' (Bolton, 1819) *''Report to the County of Lanark of a Plan for relieving Public Distress'' (Glasgow: Glasgow University Press, 1821) *''An Explanation of the Cause of Distress which pervades the civilised parts of the world'' (London and Paris, 1823) *''An Address to All Classes in the State''. London, 1832 *''The Revolution in the Mind and Practice of the Human Race''. London, 1849 Collected works: *A New View of Society and Other Writings

', introduction by G. D. H. Cole. London and New York: J. M. Dent & Sons, E. P. Dutton and Co., 1927 *''A New View of Society and Other Writings'', G. Claeys, ed. London and New York: Penguin Books, 1991 *''The Selected Works of Robert Owen'', G. Claeys, ed., 4 vols. London: Pickering and Chatto, 1993 Archival collections: *Robert Owen Collection, National Co-operative Archive, United Kingdom. *New Harmony, Indiana, Collection, 1814–1884, 1920, 1964,

Indiana Historical Society

The Indiana Historical Society (IHS) is one of the United States' oldest and largest historical societies and describes itself as "Indiana's Storyteller". It is housed in the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Indiana History Center at 450 West Ohio Street ...

, Indianapolis, Indiana, United States

*New Harmony Series III Collection, Workingmen's Institute, New Harmony, Indiana, United States

*Owen family collection, 1826–1967, bulk 1830–1890, Indiana University Archives, Bloomington, Indiana, United StatesThe collection includes the correspondence, speeches, and publications of Robert Owens and his descendants. See

See also

*Cincinnati Time Store

The Cincinnati Time Store (1827-1830) was the first in a series of retail stores created by American individualist anarchist Josiah Warren to test his economic labor theory of value. The experimental store operated from May 18, 1827 until May 18 ...

*José María Arizmendiarrieta

Father José María Arizmendiarrieta Madariaga ( Marquina-Xemein, Bizkaia, Spain, April 22, 1915 - Mondragon, Gipuzkoa, Spain, November 29, 1976) was a Basque Catholic priest and promoter of the cooperative companies of the Mondragon Corporat ...

*Labour voucher

Labour vouchers (also known as labour cheques, labour notes, labour certificates and personal credit) are a device proposed to govern demand for goods in some models of socialism and to replace some of the tasks performed by currency under capi ...

*List of Owenite communities in the United States

This is a list of Owenite communities in the United States which emerged during a short-lived popular boom during the second half of the 1820s. Between 1825 and 1830 more than a dozen such colonies were established in the US, inspired by the ide ...

*Owenstown

Owenstown is the name of a proposed new town of 3200 homes to be built on 400 acres of a 2000-acre site in South Lanarkshire, next to Tinto, Tinto Hill and the small village, Rigside, only three miles north-east of the A74(M) and M74 motorways, ...

*Owenism

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative m ...

* William King

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * (online version) * * * * * * *Further reading

*Biographies of Owen

*A. J. Booth,Robert Owen, the Founder of Socialism in England

' (London, 1869) *G. D. H. Cole,

Life of Robert Owen

'. London, Ernest Benn Ltd., 1925; second edition Macmillan, 1930 *

Lloyd Jones Lloyd Jones or Lloyd-Jones may refer to:

People Sports

* Lloyd Jones (athlete) (1884–1971), American athlete in the 1908 Summer Olympics

*Lloyd Jones (figure skater) (born 1988), Welsh ice dancer

*Lloyd Jones (English footballer) (born 1995), En ...

. The Life, Times, and Labours of Robert Owen

'. London, 1889 *A. L. Morton,

The Life and Ideas of Robert Owen