René Descartes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

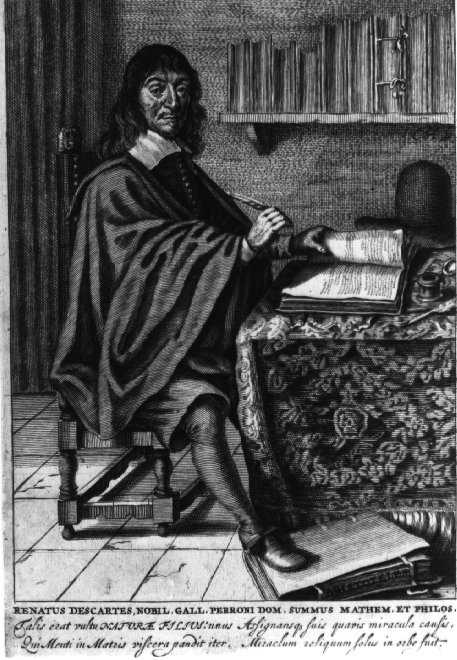

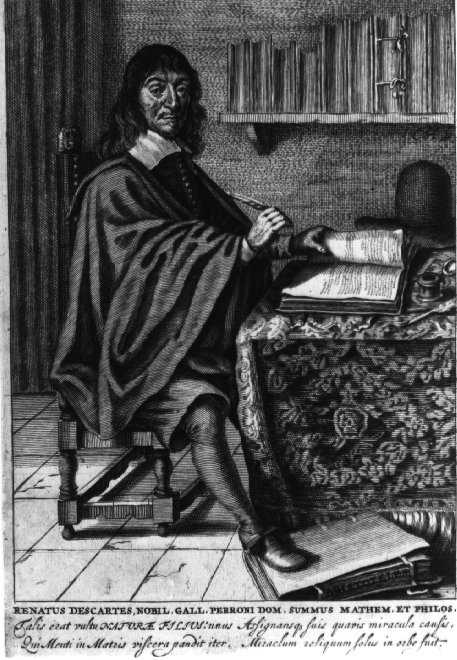

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French

''History of western philosophy''

pp. 511, 516–17. He laid the foundation for 17th-century continental

René Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine, Province of Touraine (now Descartes,

René Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine, Province of Touraine (now Descartes,

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, scientist

A scientist is a person who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosoph ...

, and mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy

Modern philosophy is philosophy developed in the modern era and associated with modernity. It is not a specific doctrine or school (and thus should not be confused with ''Modernism''), although there are certain assumptions common to much of i ...

and science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

. Mathematics was central to his method of inquiry, and he connected the previously separate fields of geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

and algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary ...

into analytic geometry. Descartes spent much of his working life in the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

, initially serving the Dutch States Army

The Dutch States Army ( nl, Staatse leger) was the army of the Dutch Republic. It was usually called this, because it was formally the army of the States-General of the Netherlands, the sovereign power of that federal republic. This mercenary arm ...

, later becoming a central intellectual of the Dutch Golden Age. Although he served a Protestant state and was later counted as a deist by critics, Descartes considered himself a devout Catholic.

Many elements of Descartes' philosophy have precedents in late Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the socia ...

, the revived Stoicism of the 16th century, or in earlier philosophers like Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North A ...

. In his natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

, he differed from the schools

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compulsor ...

on two major points: first, he rejected the splitting of corporeal substance into matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic part ...

and form; second, he rejected any appeal to final ends, divine or natural, in explaining natural phenomena. In his theology, he insists on the absolute freedom of God's act of creation. Refusing to accept the authority of previous philosophers, Descartes frequently set his views apart from the philosophers who preceded him. In the opening section of the ''Passions of the Soul

In his final philosophical treatise, ''The Passions of the Soul'' (french: Les Passions de l'âme), completed in 1649 and dedicated to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, René Descartes contributes to a long tradition of philosophical inquiry into the ...

'', an early modern treatise on emotions, Descartes goes so far as to assert that he will write on this topic "as if no one had written on these matters before." His best known philosophical statement is " la, link=no, cogito, ergo sum

The Latin , usually translated into English as "I think, therefore I am", is the "first principle" of René Descartes's philosophy. He originally published it in French as , in his 1637 ''Discourse on the Method'', so as to reach a wider audie ...

, label=none" ("I think, therefore I am"; french: link=no, Je pense, donc je suis), found in ''Discourse on the Method

''Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences'' (french: Discours de la Méthode Pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la vérité dans les sciences) is a philosophical and autobiographical ...

'' (1637; in French and Latin) and ''Principles of Philosophy

''Principles of Philosophy'' ( la, Principia Philosophiae) is a book by René Descartes. In essence, it is a synthesis of the '' Discourse on Method'' and '' Meditations on First Philosophy''.Guy Durandin, ''Les Principes de la Philosophie. Int ...

'' (1644, in Latin).

Descartes has often been called the father of modern philosophy, and is largely seen as responsible for the increased attention given to epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Epis ...

in the 17th century.Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

(2004''History of western philosophy''

pp. 511, 516–17. He laid the foundation for 17th-century continental

rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy ...

, later advocated by Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, ...

and Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of ma ...

, and was later opposed by the empiricist

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

school of thought consisting of Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influe ...

, Locke, Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

, and Hume. The rise of early modern rationalism – as a highly systematic school of philosophy in its own right for the first time in history – exerted an immense and profound influence on modern Western thought in general, with the birth of two influential rationalistic philosophical systems of Descartes (Cartesianism

Cartesianism is the philosophical and scientific system of René Descartes and its subsequent development by other seventeenth century thinkers, most notably François Poullain de la Barre, Nicolas Malebranche and Baruch Spinoza. Descartes is o ...

) and Spinoza (Spinozism

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

). It was the 17th-century arch-rationalists like Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz who have given the " Age of Reason" its name and place in history. Leibniz, Spinoza, and Descartes were all well-versed in mathematics as well as philosophy, and Descartes and Leibniz contributed greatly to science as well.

Descartes' ''Meditations on First Philosophy

''Meditations on First Philosophy, in which the existence of God and the immortality of the soul are demonstrated'' ( la, Meditationes de Prima Philosophia, in qua Dei existentia et animæ immortalitas demonstratur) is a philosophical treatise ...

'' (1641) continues to be a standard text at most university philosophy departments. Descartes' influence in mathematics is equally apparent; the Cartesian coordinate system was named after him. He is credited as the father of analytic geometry—used in the discovery of infinitesimal calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithm ...

and analysis

Analysis ( : analyses) is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (3 ...

. Descartes was also one of the key figures in the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transfo ...

.

Life

Early life

Indre-et-Loire

Indre-et-Loire () is a department in west-central France named after the Indre River and Loire River. In 2019, it had a population of 610,079. René Descartes was conceived about halfway through August 1595. His mother, Jeanne Brochard, died a few days after giving birth to a still-born child in May 1597. Descartes' father, Joachim, was a member of the  In accordance with his ambition to become a professional military officer in 1618, Descartes joined, as a

In accordance with his ambition to become a professional military officer in 1618, Descartes joined, as a

Descartes: An Intellectual Biography

''. Oxford:

Descartes returned to the

Descartes returned to the

"Descartes' debt to Teresa of Ávila, or why we should work on women in the history of philosophy"

, ''

In his ''Discourse on the Method'', he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called hyperbolical/metaphysical doubt, also sometimes referred to as

In his ''Discourse on the Method'', he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called hyperbolical/metaphysical doubt, also sometimes referred to as

Descartes has often been dubbed the father of modern

Descartes has often been dubbed the father of modern

''Postmodern theory and biblical theology: vanquishing God's shadow''

p. 126 In modernity, the guarantor of truth is not God anymore but human beings, each of whom is a "self-conscious shaper and guarantor" of their own reality. In that way, each person is turned into a reasoning adult, a subject and agent,Lovitt, Tom (1977) introduction to

One of Descartes's most enduring legacies was his development of Cartesian or analytic geometry, which uses algebra to describe geometry. Descartes "invented the convention of representing unknowns in equations by ''x'', ''y'', and ''z'', and knowns by ''a'', ''b'', and ''c''". He also "pioneered the standard notation" that uses superscripts to show the powers or exponents; for example, the 2 used in x2 to indicate x squared. He was first to assign a fundamental place for algebra in the system of knowledge, using it as a method to automate or mechanize reasoning, particularly about abstract, unknown quantities. European mathematicians had previously viewed geometry as a more fundamental form of mathematics, serving as the foundation of algebra. Algebraic rules were given geometric proofs by mathematicians such as Pacioli, Cardan, Tartaglia and

One of Descartes's most enduring legacies was his development of Cartesian or analytic geometry, which uses algebra to describe geometry. Descartes "invented the convention of representing unknowns in equations by ''x'', ''y'', and ''z'', and knowns by ''a'', ''b'', and ''c''". He also "pioneered the standard notation" that uses superscripts to show the powers or exponents; for example, the 2 used in x2 to indicate x squared. He was first to assign a fundamental place for algebra in the system of knowledge, using it as a method to automate or mechanize reasoning, particularly about abstract, unknown quantities. European mathematicians had previously viewed geometry as a more fundamental form of mathematics, serving as the foundation of algebra. Algebraic rules were given geometric proofs by mathematicians such as Pacioli, Cardan, Tartaglia and

''Musicae Compendium''

A treatise on music theory and the aesthetics of music, which Descartes dedicated to early collaborator Isaac Beeckman (written in 1618, first published—posthumously—in 1650). * 1626–1628. ''Regulae ad directionem ingenii'' (''

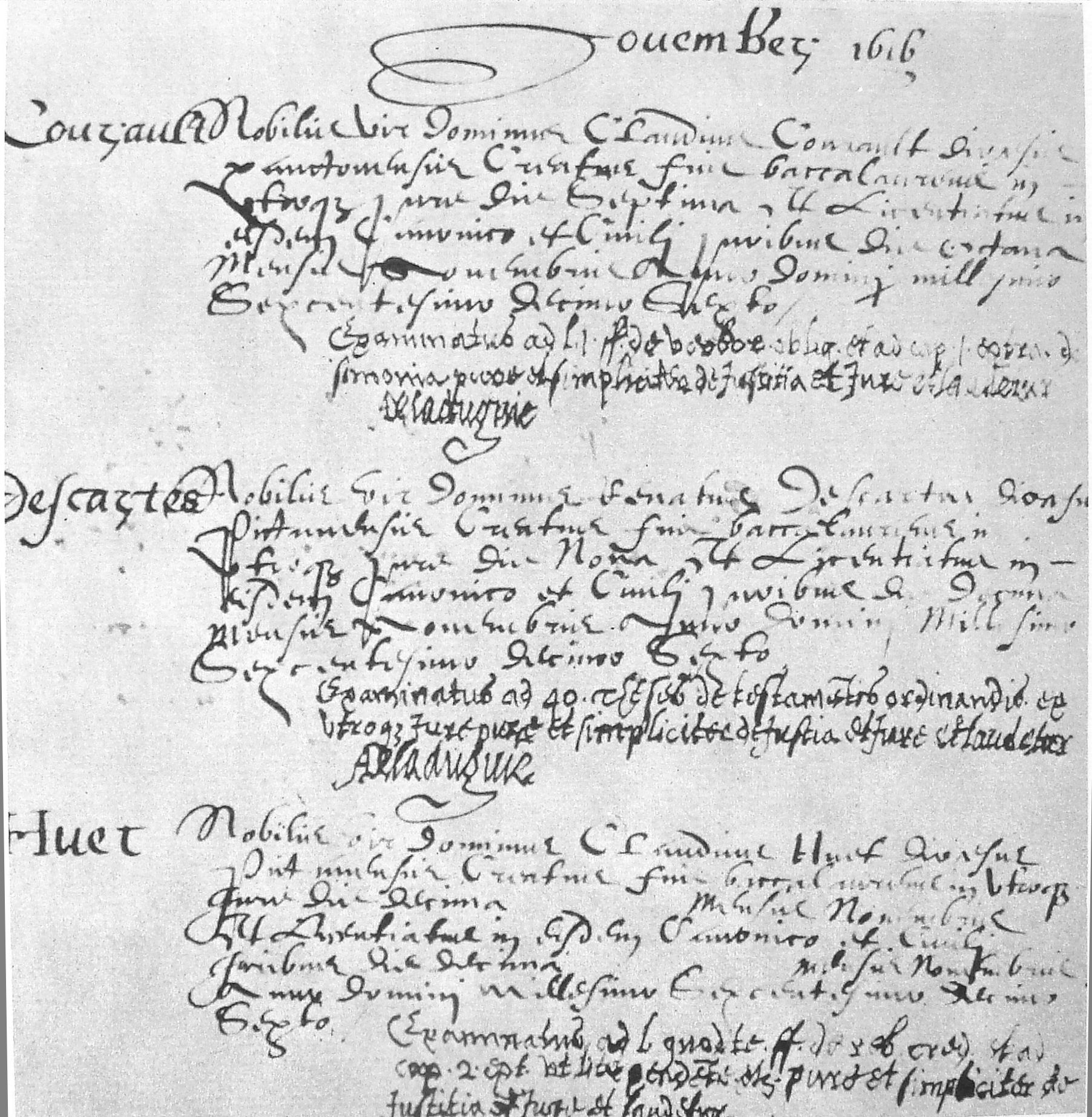

File:Handwritten letter by Descartes December 1638.jpg, Handwritten letter by Descartes, December 1638

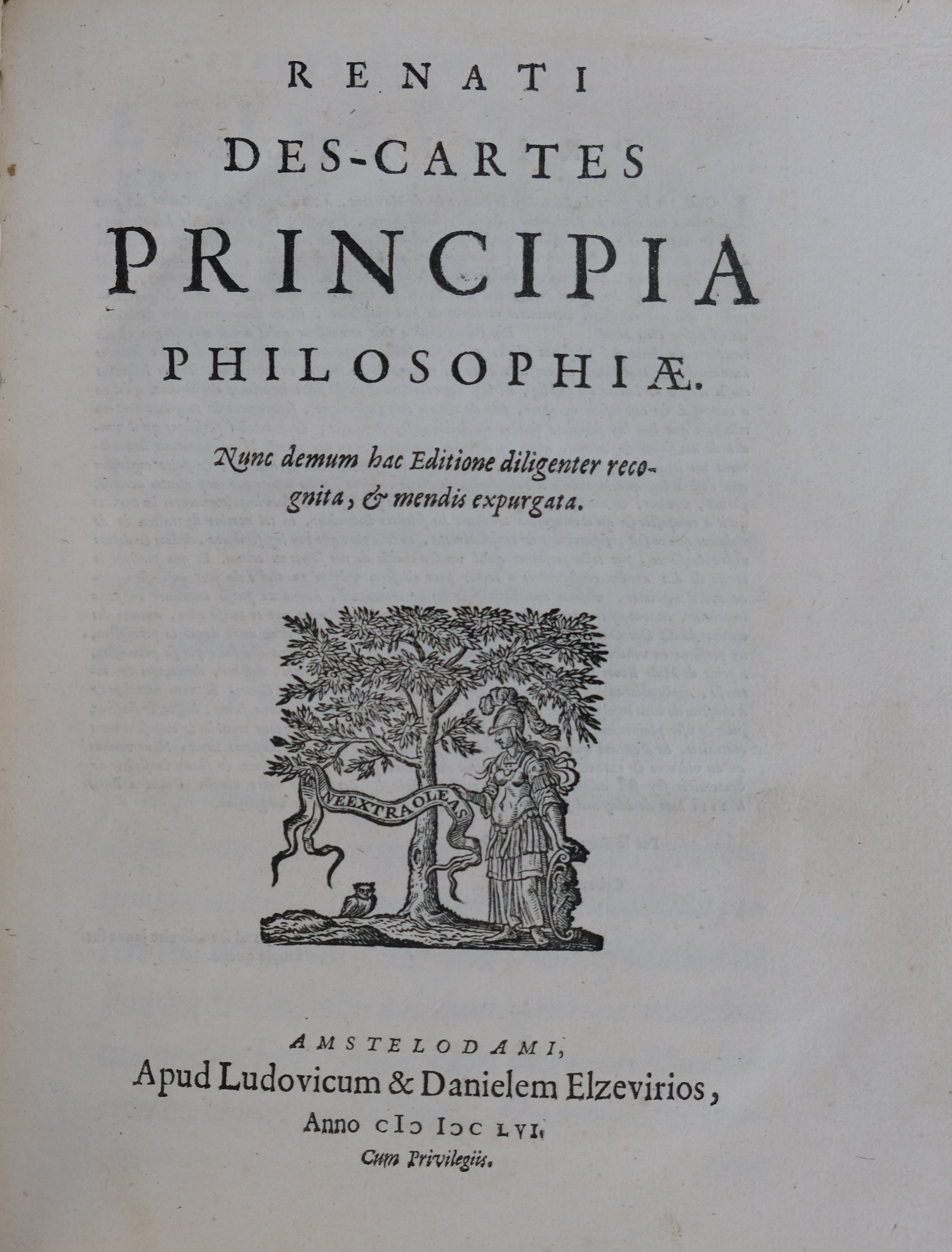

File:René Descartes 1644 Principia philosophiae.jpg, ''Principia philosophiae'', 1644

''Discours de la methode''

, 1637

''Renati Des-Cartes Principia philosophiæ''

, 1644

''Le monde de Mr. Descartes ou le traité de la lumiere''

, 1664

''Geometria''

, 1659

''Meditationes de prima philosophia''

, 1670

''Opera philosophica''

, 1672

''Regulae ad directionem ingenii. Rules for the Direction of the Natural Intelligence. A Bilingual Edition of the Cartesian Treatise on Method''

, ed. & trans. G. Heffernan (Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi, 1998). * 1633

, tr. by

''The Geometry of René Descartes''

, trans. D. E. Smith & Marcia Latham (Chicago: Open Court, 1925). * 1641. ''Meditations on First Philosophy'', tr. by J. Cottingham, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. Latin original. Alternative English title: ''Metaphysical Meditations''. Includes six ''Objections and Replies''. A second edition published the following year, includes an additional ''Objection and Reply'' and a ''Letter to Dinet''

HTML Online Latin-French-English Edition

. * 1644

''Principles of Philosophy''

, trans. V. R. Miller & R. P. Miller: (

''Passions of the Soul''

, trans. S. H. Voss (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1989). Dedicated to Elisabeth of the Palatinate. * 1619–1648. ''René Descartes, Isaac Beeckman, Marin Mersenne. Lettere 1619–1648'', ed. by Giulia Beglioioso and Jean Robert-Armogathe, Milano, Bompiani, 2015 pp. 1696.

Descartes' Demon: A Dialogical Analysis of 'Meditations on First Philosophy.'

Theory & Psychology, 16, 761–781. * * Heidegger, Martin 938(2002) ''The Age of the World Picture'' i

''Off the Beaten Track''

pp. 57–85 * * * Monnoyeur, Françoise (November 2017), ''Matière et espace dans le système cartésien'', Paris, Harmattan, 266 pages. . * Moreno Romo, Juan Carlos, ''Vindicación del cartesianismo radical'', Anthropos, Barcelona, 2010. * Moreno Romo, Juan Carlos (Coord.), ''Descartes vivo. Ejercicios de hermenéutica cartesiana'', Anthropos, Barcelona, 2007. * * Negri, Antonio (2007) ''The Political Descartes'', Verso. * * Sasaki Chikara (2003)

''Descartes's Mathematical Thought''

. (Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 237.) xiv + 496 pp., bibl., indexes. Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. * * Serfati, Michel, 2005, "Géometrie" in Ivor Grattan-Guinness, ed., ''Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics''. Elsevier: 1–22. * * * * Watson, Richard A. (2007). Cogito, Ergo Sum: a life of René Descartes. David R Godine. 2002, reprint 2007. . Was chosen by the New York Public library as one of "25 Books to Remember from 2002" *

The Correspondence of René Descartes

i

EMLO

* * *

*

* ttp://digitalcommons.unl.edu/modlangfrench/20/ René Descartes (1596–1650)Published in ''Encyclopedia of Rhetoric and Composition'' (1996)

A site containing Descartes's main works, including correspondence, slightly modified for easier reading

Descartes Philosophical Writings tr. by Norman Kemp Smith

at archive.org

Studies in the Cartesian philosophy (1902) by Norman Kemp Smith

at archive.org

The Philosophical Works Of Descartes Volume II (1934)

at archive.org

* *

Centro Interdipartimentale di Studi su Descartes e il Seicento

* Livre Premier, ''La Géométrie'', online and analyzed by A. Warusfel

''BibNum''

small> lick "à télécharger" for English analysis/small>

''Bibliografia cartesiana/Bibliographie cartésienne on-line (1997–2012)''

Descartes

Life and works

Epistemology

Mathematics

Physics

Ethics

Modal Metaphysics

Ontological Argument

Theory of Ideas

Pineal Gland

Descartes

Descartes: Ethics

Descartes: Mind-Body Distinction

Descartes: Scientific Method

Bernard Williams interviewed about Descartes on ''Men of ideas''

BALDASSARRI, F. (2019) The mechanical life of plants: Descartes on botany. The British Journal for the History of Science, 52(1), 41-63. doi:10.1017/S000708741800095X

{{DEFAULTSORT:Descartes, Rene * 1596 births 1650 deaths 17th-century French mathematicians 17th-century French philosophers 17th-century French scientists 17th-century French writers 17th-century Latin-language writers 17th-century male writers Age of Enlightenment Aphorists Augustinian philosophers Burials at Saint-Germain-des-Prés (abbey) Catholic philosophers French consciousness researchers and theorists Constructed language creators Critics of animal rights Deaths from pneumonia in Sweden Enlightenment philosophers Epistemologists Founders of philosophical traditions French emigrants to the Dutch Republic French ethicists French expatriates in Sweden French expatriates in the Dutch Republic French logicians French mercenaries French music theorists French Roman Catholics Geometric algebra History of algebra History of cartography History of education in Europe History of ethics History of geometry History of logic History of mathematics History of measurement History of philosophy History of science Humor researchers Intellectual history Leiden University alumni Metaphilosophers Metaphysics writers Military personnel of the Thirty Years' War Mind–body problem Moral philosophers Natural philosophers Ontologists People from Indre-et-Loire People of the Age of Enlightenment Philosophers of art Philosophers of culture Philosophers of education Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of history Philosophers of logic Philosophers of mathematics Philosophers of mind Philosophers of psychology Philosophers of science Philosophers of social science Rationalists Rationality theorists Social critics Social philosophers Theorists on Western civilization University of Poitiers alumni Western philosophy Writers about activism and social change Writers about religion and science Writers who illustrated their own writing

Parlement of Brittany

The Parliament of Brittany (, ) was one of the , a court of justice under the French , with its seat at Rennes. The last building to house the Parliament still stands and now houses the Rennes Court of Appeal, the natural successor of the Parliame ...

at Rennes. René lived with his grandmother and with his great-uncle. Although the Descartes family was Roman Catholic, the Poitou

Poitou (, , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical c ...

region was controlled by the Protestant Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

. In 1607, late because of his fragile health, he entered the Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children between ...

at La Flèche

La Flèche () is a town and commune in the French department of Sarthe, in the Pays de la Loire region in the Loire Valley. It is the sub-prefecture of the South-Sarthe, the chief district and the chief city of a canton, and the second most po ...

, where he was introduced to mathematics and physics, including Galileo's work. While there, Descartes first encountered hermetic mysticism. After graduation in 1614, he studied for two years (1615–16) at the University of Poitiers

The University of Poitiers (UP; french: Université de Poitiers) is a public university located in Poitiers, France. It is a member of the Coimbra Group. It is multidisciplinary and contributes to making Poitiers the city with the highest studen ...

, earning a '' Baccalauréat'' and '' Licence'' in canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western ca ...

and civil law in 1616, in accordance with his father's wishes that he should become a lawyer. From there, he moved to Paris.

In ''Discourse on the Method

''Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences'' (french: Discours de la Méthode Pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la vérité dans les sciences) is a philosophical and autobiographical ...

'', Descartes recalls:

I entirely abandoned the study of letters. Resolving to seek no knowledge other than that of which could be found in myself or else in the great book of the world, I spent the rest of my youth traveling, visiting courts and armies, mixing with people of diverse temperaments and ranks, gathering various experiences, testing myself in the situations which fortune offered me, and at all times reflecting upon whatever came my way to derive some profit from it.

mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any ...

, the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Dutch States Army

The Dutch States Army ( nl, Staatse leger) was the army of the Dutch Republic. It was usually called this, because it was formally the army of the States-General of the Netherlands, the sovereign power of that federal republic. This mercenary arm ...

in Breda under the command of Maurice of Nassau

Maurice of Orange ( nl, Maurits van Oranje; 14 November 1567 – 23 April 1625) was ''stadtholder'' of all the provinces of the Dutch Republic except for Friesland from 1585 at the earliest until his death in 1625. Before he became Prince o ...

, and undertook a formal study of military engineering, as established by Simon Stevin

Simon Stevin (; 1548–1620), sometimes called Stevinus, was a Flemish mathematician, scientist and music theorist. He made various contributions in many areas of science and engineering, both theoretical and practical. He also translated vario ...

.Gaukroger, Stephen. 1995. Descartes: An Intellectual Biography

''. Oxford:

Clarendon Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

. Descartes, therefore, received much encouragement in Breda to advance his knowledge of mathematics. In this way, he became acquainted with Isaac Beeckman

Isaac Beeckman (10 December 1588van Berkel, p10 – 19 May 1637) was a Dutch philosopher and scientist, who, through his studies and contact with leading natural philosophers, may have "virtually given birth to modern atomism".Harold J. Cook, in ...

, the principal of a Dordrecht

Dordrecht (), historically known in English as Dordt (still colloquially used in Dutch, ) or Dort, is a city and municipality in the Western Netherlands, located in the province of South Holland. It is the province's fifth-largest city after R ...

school, for whom he wrote the ''Compendium of Music'' (written 1618, published 1650). Together, they worked on free fall

In Newtonian physics, free fall is any motion of a body where gravity is the only force acting upon it. In the context of general relativity, where gravitation is reduced to a space-time curvature, a body in free fall has no force acting on ...

, catenary

In physics and geometry, a catenary (, ) is the curve that an idealized hanging chain or cable assumes under its own weight when supported only at its ends in a uniform gravitational field.

The catenary curve has a U-like shape, superfici ...

, conic section

In mathematics, a conic section, quadratic curve or conic is a curve obtained as the intersection of the surface of a cone with a plane. The three types of conic section are the hyperbola, the parabola, and the ellipse; the circle is a spe ...

, and fluid statics

Fluid statics or hydrostatics is the branch of fluid mechanics that studies the condition of the equilibrium of a floating body and submerged body " fluids at hydrostatic equilibrium and the pressure in a fluid, or exerted by a fluid, on an imm ...

. Both believed that it was necessary to create a method that thoroughly linked mathematics and physics.Durandin, Guy. 1970. ''Les Principes de la Philosophie. Introduction et notes''. Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin

The Librairie philosophique J. Vrin is a bookshop and publisher in Paris, specializing in books on philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, know ...

.

While in the service of the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Duke Maximilian of Bavaria from 1619, Descartes was present at the Battle of the White Mountain

), near Prague, Bohemian Confederation(present-day Czech Republic)

, coordinates =

, territory =

, result = Imperial-Spanish victory

, status =

, combatants_header =

, combatant1 = Catholic L ...

near Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

, in November 1620.

According to Adrien Baillet

Adrien Baillet (13 June 164921 January 1706) was a French scholar and critic. He is now best known as a biographer of René Descartes.

Life

He was born in the village of La Neuville-en-Hez, Neuville near Beauvais, in Picardy. His parents could o ...

, on the night of 10–11 November 1619 (St. Martin's Day

Saint Martin's Day or Martinmas, sometimes historically called Old Halloween or Old Hallowmas Eve, is the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours and is celebrated in the liturgical year on 11 November. In the Middle Ages and early modern period, it ...

), while stationed in Neuburg an der Donau

Neuburg an der Donau (Central Bavarian: ''Neiburg an da Donau'') is a town which is the capital of the Neuburg-Schrobenhausen district in the state of Bavaria in Germany.

Divisions

The municipality has 16 divisions:

* Altmannstetten

* Bergen, Neu ...

, Descartes shut himself in a room with an "oven" (probably a cocklestove

A masonry heater (also called a masonry stove) is a device for warming an interior space through radiant heating, by capturing the heat from periodic burning of fuel (usually wood), and then radiating the heat at a fairly constant temperature ...

) to escape the cold. While within, he had three dreams, and believed that a divine spirit revealed to him a new philosophy. However, it is speculated that what Descartes considered to be his second dream was actually an episode of exploding head syndrome

Exploding head syndrome (EHS) is an abnormal sensory perception during sleep in which a person experiences auditory hallucinations that are loud and of short duration when falling asleep or waking up. The noise may be frightening, typically occ ...

. Upon exiting, he had formulated analytic geometry and the idea of applying the mathematical method to philosophy. He concluded from these visions that the pursuit of science would prove to be, for him, the pursuit of true wisdom and a central part of his life's work. Descartes also saw very clearly that all truths were linked with one another, so that finding a fundamental truth and proceeding with logic would open the way to all science. Descartes discovered this basic truth quite soon: his famous "I think, therefore I am

The Latin , usually translated into English as "I think, therefore I am", is the "first principle" of René Descartes's philosophy. He originally published it in French as , in his 1637 ''Discourse on the Method'', so as to reach a wider audienc ...

."

Career

France

In 1620, Descartes left the army. He visitedBasilica della Santa Casa

The Basilica della Santa Casa ( en, Basilica of the Holy House) is a Marian shrine in Loreto, in the Marches, Italy. The basilica is known for enshrining the house in which the Blessed Virgin Mary is believed by some Catholics to have lived. Pio ...

in Loreto, then visited various countries before returning to France, and during the next few years, he spent time in Paris. It was there that he composed his first essay on method: ''Regulae ad Directionem Ingenii'' (''Rules for the Direction of the Mind

In 1628 René Descartes began work on an unfinished treatise regarding the proper method for scientific and philosophical thinking entitled ''Regulae ad directionem ingenii'', or ''Rules for the Direction of the Mind''. The work was eventually pub ...

''). He arrived in La Haye in 1623, selling all of his property to invest in bonds, which provided a comfortable income for the rest of his life. Descartes was present at the siege of La Rochelle

The siege of La Rochelle (, or sometimes ) was a result of a war between the French royal forces of Louis XIII of France and the Huguenots of La Rochelle in 1627–28. The siege marked the height of the struggle between the Catholics and the Pr ...

by Cardinal Richelieu in 1627.Shea, William R. 1991. ''The Magic of Numbers and Motion''. Science History Publications. In the autumn of that year, in the residence of the papal nuncio Guidi di Bagno, where he came with Mersenne

Marin Mersenne, OM (also known as Marinus Mersennus or ''le Père'' Mersenne; ; 8 September 1588 – 1 September 1648) was a French polymath whose works touched a wide variety of fields. He is perhaps best known today among mathematicians for ...

and many other scholars to listen to a lecture given by the alchemist, Nicolas de Villiers, Sieur de Chandoux, on the principles of a supposed new philosophy, Cardinal Bérulle

Bérulle () is a commune in the Aube department in north-central France.

History

Berulle's history dates back to the 12th century when it was a part of a small chastelleny under the county of Champagne. Over time, Berulle's ownership changed ...

urged him to write an exposition of his new philosophy in some location beyond the reach of the Inquisition.

Netherlands

Descartes returned to the

Descartes returned to the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

in 1628. In April 1629, he joined the University of Franeker

The University of Franeker (1585–1811) was a university in Franeker, Friesland, the Netherlands. It was the second oldest university of the Netherlands, founded shortly after Leiden University.

History

Also known as ''Academia Franekerensis'' ...

, studying under Adriaan Metius

Adriaan Adriaanszoon, called Metius, (9 December 1571 – 6 September 1635), was a Dutch geometer and astronomer born in Alkmaar. The name "Metius" comes from the Dutch word ''meten'' ("measuring"), and therefore means something like "measurer" o ...

, either living with a Catholic family or renting the Sjaerdemaslot. The next year, under the name "Poitevin", he enrolled at Leiden University, which at the time was a Protestant University. He studied both mathematics with Jacobus Golius

Jacob Golius born Jacob van Gool (1596 – September 28, 1667) was an Orientalist and mathematician based at the University of Leiden in Netherlands. He is primarily remembered as an Orientalist. He published Arabic texts in Arabic at Leiden, ...

, who confronted him with Pappus's hexagon theorem

In mathematics, Pappus's hexagon theorem (attributed to Pappus of Alexandria) states that

*given one set of collinear points A, B, C, and another set of collinear points a,b,c, then the intersection points X,Y,Z of line pairs Ab and aB, Ac and ...

, and astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

with Martin Hortensius. In October 1630, he had a falling-out with Beeckman, whom he accused of plagiarizing some of his ideas. In Amsterdam, he had a relationship with a servant girl, Helena Jans van der Strom, with whom he had a daughter, Francine

:''This is a disambiguation page for the common name Francine.''

Francine is a female given name. The name is of French origin. The name Francine was most popular in France itself during the 1940s (Besnard & Desplanques 2003), and was well used i ...

, who was born in 1635 in Deventer

Deventer (; Sallands: ) is a city and municipality in the Salland historical region of the province of Overijssel, Netherlands. In 2020, Deventer had a population of 100,913. The city is largely situated on the east bank of the river IJssel, bu ...

. She was baptized a Protestant and died of scarlet fever at the age of 5.

Unlike many moralists of the time, Descartes did not deprecate the passions but rather defended them; he wept upon Francine's death in 1640. According to a recent biography by Jason Porterfield, "Descartes said that he did not believe that one must refrain from tears to prove oneself a man." Russell Shorto

Russell Anthony Shorto (born February 8, 1959) is an American author, historian, and journalist who is best known for his book on the Dutch origins of New York City, '' The Island at the Center of the World''. Shorto's research for the book rel ...

speculates that the experience of fatherhood and losing a child formed a turning point in Descartes's work, changing its focus from medicine to a quest for universal answers.

Despite frequent moves, he wrote all of his major work during his 20-plus years in the Netherlands, initiating a revolution in mathematics and philosophy. In 1633, Galileo was condemned by the Italian Inquisition, and Descartes abandoned plans to publish ''Treatise on the World

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions."Trea ...

'', his work of the previous four years. Nevertheless, in 1637, he published parts of this work in three essays: "Les Météores" (The Meteors), " La Dioptrique" (Dioptrics) and '' La Géométrie'' (''Geometry''), preceded by an introduction, his famous ''Discours de la méthode'' (''Discourse on the Method

''Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences'' (french: Discours de la Méthode Pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la vérité dans les sciences) is a philosophical and autobiographical ...

''). In it, Descartes lays out four rules of thought, meant to ensure that our knowledge rests upon a firm foundation:

In ''La Géométrie'', Descartes exploited the discoveries he made with Pierre de Fermat

Pierre de Fermat (; between 31 October and 6 December 1607 – 12 January 1665) was a French mathematician who is given credit for early developments that led to infinitesimal calculus, including his technique of adequality. In particular, he ...

, having been able to do so because his paper, ''Introduction to Loci'', was published posthumously in 1679. This later became known as Cartesian Geometry.

Descartes continued to publish works concerning both mathematics and philosophy for the rest of his life. In 1641, he published a metaphysics treatise, ''Meditationes de Prima Philosophia'' (''Meditations on First Philosophy''), written in Latin and thus addressed to the learned. It was followed in 1644 by ''Principia Philosophiae'' (''Principles of Philosophy

''Principles of Philosophy'' ( la, Principia Philosophiae) is a book by René Descartes. In essence, it is a synthesis of the '' Discourse on Method'' and '' Meditations on First Philosophy''.Guy Durandin, ''Les Principes de la Philosophie. Int ...

''), a kind of synthesis of the ''Discourse on the Method'' and ''Meditations on First Philosophy''. In 1643, Cartesian philosophy was condemned at the University of Utrecht

Utrecht University (UU; nl, Universiteit Utrecht, formerly ''Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht'') is a public research university in Utrecht, Netherlands. Established , it is one of the oldest universities in the Netherlands. In 2018, it had an enrollme ...

, and Descartes was obliged to flee to the Hague, settling in Egmond-Binnen

Egmond-Binnen () is a village in the Dutch province of North Holland. It is a part of the municipality of Bergen, and lies about southwest of Alkmaar.

History

The village was first mentioned in 922 as Ekmunde. The etymology is unknown. The m ...

.

Between 1643 and 1649 Descartes lived with his girlfriend at Egmond-Binnen in an inn. Descartes became friendly with Anthony Studler van Zurck, lord of Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula of ...

and participated in the design of his mansion and estate. He also met Dirck Rembrantsz van Nierop

Dirck Rembrantsz van Nierop (1610 – 4 November 1682) was a seventeenth-century Dutch cartographer, mathematician, surveyor, astronomer, shoemaker and Mennonite teacher.

Life

Van Nierop was born and died at Nieuwe Niedorp ("Nierop"), Holland ...

, a mathematician and surveyor. He was so impressed by Van Nierop's knowledge that he even brought him to the attention of Constantijn Huygens

Sir Constantijn Huygens, Lord of Zuilichem ( , , ; 4 September 159628 March 1687), was a Dutch Golden Age poet and composer. He was also secretary to two Princes of Orange: Frederick Henry and William II, and the father of the scientist Ch ...

and Frans van Schooten.

Christia Mercer

Christia Mercer is an American philosopher and the Gustave M. Berne Professor in the Department of Philosophy at Columbia University. She is known for her work on the history of early modern philosophy, the history of Platonism, and the history ...

suggested that Descartes may have been influenced by Spanish author and Roman Catholic nun Teresa of Ávila

Teresa of Ávila, OCD (born Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda y Ahumada; 28 March 15154 or 15 October 1582), also called Saint Teresa of Jesus, was a Spanish Carmelite nun and prominent Spanish mystic and religious reformer.

Active during t ...

, who, fifty years earlier, published ''The Interior Castle

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

'', concerning the role of philosophical reflection in intellectual growth.Mercer, C."Descartes' debt to Teresa of Ávila, or why we should work on women in the history of philosophy"

, ''

Philosophical Studies

''Philosophical Studies'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal for philosophy in the analytic tradition. The journal is devoted to the publication of papers in exclusively analytic philosophy and welcomes papers applying formal techniques to philo ...

'' 174, 2017.

Descartes began (through Alfonso Polloti, an Italian general in Dutch service) a six-year correspondence with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, devoted mainly to moral and psychological subjects. Connected with this correspondence, in 1649 he published ''Les Passions de l'âme'' ('' The Passions of the Soul''), which he dedicated to the Princess. A French translation of ''Principia Philosophiae'', prepared by Abbot Claude Picot, was published in 1647. This edition was also dedicated to Princess Elisabeth. In the preface to the French edition, Descartes praised true philosophy as a means to attain wisdom. He identifies four ordinary sources to reach wisdom and finally says that there is a fifth, better and more secure, consisting in the search for first causes.

Sweden

By 1649, Descartes had become one of Europe's most famous philosophers and scientists. That year, Queen Christina of Sweden invited him to her court to organize a new scientific academy and tutor her in his ideas about love. Descartes accepted, and moved to Sweden in the middle of winter. She was interested in and stimulated Descartes to publish ''The Passions of the Soul.'' He was a guest at the house ofPierre Chanut

Pierre Hector Chanut (February 22, 1601 in Riom – July 3, 1662 in Livry-sur-Seine) was a civil servant in the Auvergne, a French ambassador in Sweden and the Dutch Republic, and state counsellor.

Life

In 1626 Chanut married Marguerite Cle ...

, living on Västerlånggatan, less than 500 meters from Tre Kronor in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

. There, Chanut and Descartes made observations with a Torricellian mercury barometer. Challenging Blaise Pascal, Descartes took the first set of barometric readings in Stockholm to see if atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1013.25 millibars, ...

could be used in forecasting the weather.

Death

Descartes arranged to give lessons to Queen Christina after her birthday, three times a week at 5 am, in her cold and draughty castle. It soon became clear they did not like each other; she did not care for hismechanical philosophy

The mechanical philosophy is a form of natural philosophy which compares the universe to a large-scale mechanism (i.e. a machine). The mechanical philosophy is associated with the scientific revolution of early modern Europe. One of the first expo ...

, nor did he share her interest in Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

. By 15 January 1650, Descartes had seen Christina only four or five times. On 1 February, he contracted pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

and died on 11 February at Chanut.

The cause of death was pneumonia according to Chanut, but peripneumonia according to Christina's physician Johann van Wullen who was not allowed to bleed him. (The winter seems to have been mild, except for the second half of January which was harsh as described by Descartes himself; however, "this remark was probably intended to be as much Descartes' take on the intellectual climate as it was about the weather.")

E. Pies has questioned this account, based on a letter by the Doctor van Wullen; however, Descartes had refused his treatment, and more arguments against its veracity have been raised since. In a 2009 book, German philosopher Theodor Ebert argues that Descartes was poisoned by a Catholic missionary who opposed his religious views.

As a Catholic in a Protestant nation, he was interred in a graveyard used mainly for orphans in Adolf Fredriks kyrka in Stockholm. His manuscripts came into the possession of Claude Clerselier

Claude Clerselier (1614, in Paris – 1684, in Paris) was a French editor and translator.

Clerselier was a lawyer in the Parlement of Paris and resident for the King of France in Sweden. He was the brother-in-law of Pierre Chanut, and served as ...

, Chanut's brother-in-law, and "a devout Catholic who has begun the process of turning Descartes into a saint by cutting, adding and publishing his letters selectively." In 1663, the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

placed Descartes' works on the ''Index of Prohibited Books''. In 1666, sixteen years after his death, his remains were taken to France and buried in Saint-Étienne-du-Mont. In 1671, Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

prohibited all lectures in Cartesianism

Cartesianism is the philosophical and scientific system of René Descartes and its subsequent development by other seventeenth century thinkers, most notably François Poullain de la Barre, Nicolas Malebranche and Baruch Spinoza. Descartes is o ...

. Although the National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nationa ...

in 1792 had planned to transfer his remains to the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, from the Classical Greek word , , ' empleto all the gods') is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was b ...

, he was reburied in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1819, missing a finger and the skull. His skull is on display in the Musée de l'Homme

The Musée de l'Homme (French, "Museum of Mankind" or "Museum of Humanity") is an anthropology museum in Paris, France. It was established in 1937 by Paul Rivet for the 1937 ''Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne ...

in Paris.

Philosophical work

In his ''Discourse on the Method'', he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called hyperbolical/metaphysical doubt, also sometimes referred to as

In his ''Discourse on the Method'', he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called hyperbolical/metaphysical doubt, also sometimes referred to as methodological skepticism

Cartesian doubt is a form of methodological skepticism associated with the writings and methodology of René Descartes (March 31, 1596Feb 11, 1650). Scruton, R.''Modern Philosophy: An Introduction and Survey''(London: Penguin Books, 1994). Leiber, ...

or Cartesian doubt: he rejects any ideas that can be doubted and then re-establishes them in order to acquire a firm foundation for genuine knowledge. Descartes built his ideas from scratch which he does in ''The Meditations on First Philosophy''. He relates this to architecture: the top soil is taken away to create a new building or structure. Descartes calls his doubt the soil and new knowledge the buildings. To Descartes, Aristotle's foundationalism is incomplete and his method of doubt enhances foundationalism.

Initially, Descartes arrives at only a single first principle that he thinks. This is expressed in the Latin phrase in ''the Discourse on Method'' "Cogito, ergo sum

The Latin , usually translated into English as "I think, therefore I am", is the "first principle" of René Descartes's philosophy. He originally published it in French as , in his 1637 ''Discourse on the Method'', so as to reach a wider audie ...

" (English: "I think, therefore I am"). Descartes concluded, if he doubted, then something or someone must be doing the doubting; therefore, the very fact that he doubted proved his existence. "The simple meaning of the phrase is that if one is skeptical of existence, that is in and of itself proof that he does exist." These two first principles—I think and I exist—were later confirmed by Descartes' clear and distinct perception (delineated in his Third Meditation from ''The Meditations''): as he clearly and distinctly perceives these two principles, Descartes reasoned, ensures their indubitability.

Descartes concludes that he can be certain that he exists because he thinks. But in what form? He perceives his body through the use of the senses; however, these have previously been unreliable. So Descartes determines that the only indubitable knowledge is that he is a ''thinking thing''. Thinking is what he does, and his power must come from his essence. Descartes defines "thought" ('' cogitatio'') as "what happens in me such that I am immediately conscious of it, insofar as I am conscious of it". Thinking is thus every activity of a person of which the person is immediately conscious

Consciousness, at its simplest, is sentience and awareness of internal and external existence. However, the lack of definitions has led to millennia of analyses, explanations and debates by philosophers, theologians, linguisticians, and scien ...

. He gave reasons for thinking that waking thoughts are distinguishable from dreams

A dream is a succession of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that usually occur involuntarily in the mind during certain stages of sleep. Humans spend about two hours dreaming per night, and each dream lasts around 5 to 20 minutes, althou ...

, and that one's mind cannot have been "hijacked" by an evil demon

The evil demon, also known as Descartes' demon, malicious demon and evil genius, is an epistemological concept that features prominently in Cartesian philosophy. In the first of his 1641 '' Meditations on First Philosophy'', Descartes imagine ...

placing an illusory external world before one's senses.

In this manner, Descartes proceeds to construct a system of knowledge, discarding perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system ...

as unreliable and, instead, admitting only deduction as a method.

Mind–body dualism

Descartes, influenced by theautomaton

An automaton (; plural: automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions.Automaton – Definition and More ...

s on display throughout the city of Paris, began to investigate the connection between the mind and body, and how the two interact. His main influences for dualism were theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

and physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

. The theory on the dualism of mind and body is Descartes' signature doctrine and permeates other theories he advanced. Known as Cartesian dualism Cartesian means of or relating to the French philosopher René Descartes—from his Latinized name ''Cartesius''. It may refer to:

Mathematics

* Cartesian closed category, a closed category in category theory

*Cartesian coordinate system, moder ...

(or mind–body dualism), his theory on the separation between the mind and the body went on to influence subsequent Western philosophies. In ''Meditations on First Philosophy'', Descartes attempted to demonstrate the existence of God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

and the distinction between the human soul and the body. Humans are a union of mind and body; thus Descartes's dualism embraced the idea that mind and body are distinct but closely joined. While many contemporary readers of Descartes found the distinction between mind and body difficult to grasp, he thought it was entirely straightforward. Descartes employed the concept of ''modes'', which are the ways in which substances exist. In ''Principles of Philosophy

''Principles of Philosophy'' ( la, Principia Philosophiae) is a book by René Descartes. In essence, it is a synthesis of the '' Discourse on Method'' and '' Meditations on First Philosophy''.Guy Durandin, ''Les Principes de la Philosophie. Int ...

'', Descartes explained, "we can clearly perceive a substance apart from the mode which we say differs from it, whereas we cannot, conversely, understand the mode apart from the substance". To perceive a mode apart from its substance requires an intellectual abstraction, which Descartes explained as follows:

The intellectual abstraction consists in my turning my thought away from one part of the contents of this richer idea the better to apply it to the other part with greater attention. Thus, when I consider a shape without thinking of the substance or the extension whose shape it is, I make a mental abstraction.According to Descartes, two substances are really distinct when each of them can exist apart from the other. Thus, Descartes reasoned that God is distinct from humans, and the body and mind of a human are also distinct from one another. He argued that the great differences between body (an extended thing) and mind (an un-extended, immaterial thing) make the two

ontologically

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

distinct. According to Descartes' indivisibility argument, the mind is utterly indivisible: because "when I consider the mind, or myself in so far as I am merely a thinking thing, I am unable to distinguish any part within myself; I understand myself to be something quite single and complete."

Moreover, in The ''Meditations'', Descartes discusses a piece of wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to giv ...

and exposes the single most characteristic doctrine of Cartesian dualism: that the universe contained two radically different kinds of substances—the mind or soul defined as thinking

In their most common sense, the terms thought and thinking refer to conscious cognitive processes that can happen independently of sensory stimulation. Their most paradigmatic forms are judging, reasoning, concept formation, problem solving, an ...

, and the body defined as matter and unthinking. The Aristotelian philosophy of Descartes' days held that the universe was inherently purposeful or teleological. Everything that happened, be it the motion of the stars or the growth of a tree

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, including only woody plants with secondary growth, plants that are ...

, was supposedly explainable by a certain purpose, goal or end that worked its way out within nature. Aristotle called this the "final cause," and these final causes were indispensable for explaining the ways nature operated. Descartes' theory of dualism supports the distinction between traditional Aristotelian science and the new science of Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws o ...

and Galileo, which denied the role of a divine power and "final causes" in its attempts to explain nature. Descartes' dualism provided the philosophical rationale for the latter by expelling the final cause from the physical universe (or ''res extensa'') in favor of the mind (or ''res cogitans''). Therefore, while Cartesian dualism paved the way for modern physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

, it also held the door open for religious beliefs about the immortality of the soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest atte ...

.

Descartes' dualism of mind and matter implied a concept of human beings. A human was, according to Descartes, a composite entity of mind and body. Descartes gave priority to the mind and argued that the mind could exist without the body, but the body could not exist without the mind. In The ''Meditations'', Descartes even argues that while the mind is a substance, the body is composed only of "accidents". But he did argue that mind and body are closely joined:

Nature also teaches me, by the sensations of pain, hunger, thirst and so on, that I am not merely present in my body as a pilot in his ship, but that I am very closely joined and, as it were, intermingled with it, so that I and the body form a unit. If this were not so, I, who am nothing but a thinking thing, would not feel pain when the body was hurt, but would perceive the damage purely by the intellect, just as a sailor perceives by sight if anything in his ship is broken.Descartes' discussion on embodiment raised one of the most perplexing problems of his dualism philosophy: What exactly is the relationship of union between the mind and the body of a person? Therefore, Cartesian dualism set the agenda for philosophical discussion of the

mind–body problem

The mind–body problem is a philosophical debate concerning the relationship between thought and consciousness in the human mind, and the brain as part of the physical body. The debate goes beyond addressing the mere question of how mind and bo ...

for many years after Descartes' death. Descartes was also a rationalist and believed in the power of innate ideas

Innatism is a philosophical and epistemological doctrine that the mind is born with ideas, knowledge, and beliefs. Therefore, the mind is not a ''tabula rasa'' (blank slate) at birth, which contrasts with the views of early empiricists such as J ...

. Descartes argued the theory of innate knowledge

Innatism is a philosophical and epistemological doctrine that the mind is born with ideas, knowledge, and beliefs. Therefore, the mind is not a ''tabula rasa'' (blank slate) at birth, which contrasts with the views of early empiricists such as J ...

and that all humans were born with knowledge through the higher power of God. It was this theory of innate knowledge that was later combated by philosopher John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

(1632–1704), an empiricist. Empiricism holds that all knowledge is acquired through experience.

Physiology and psychology

In ''The Passions of the Soul'', published in 1649, Descartes discussed the common contemporary belief that the human body contained animal spirits. These animal spirits were believed to be light and roaming fluids circulating rapidly around the nervous system between the brain and the muscles. These animal spirits were believed to affect the human soul, or passions of the soul. Descartes distinguished six basic passions: wonder, love, hatred, desire, joy and sadness. All of these passions, he argued, represented different combinations of the original spirit, and influenced the soul to will or want certain actions. He argued, for example, that fear is a passion that moves the soul to generate a response in the body. In line with his dualist teachings on the separation between the soul and the body, he hypothesized that some part of the brain served as a connector between the soul and the body and singled out the pineal gland as connector. Descartes argued that signals passed from the ear and the eye to the pineal gland, through animal spirits. Thus different motions in the gland cause various animal spirits. He argued that these motions in the pineal gland are based on God's will and that humans are supposed to want and like things that are useful to them. But he also argued that the animal spirits that moved around the body could distort the commands from the pineal gland, thus humans had to learn how to control their passions. Descartes advanced a theory on automatic bodily reactions to external events, which influenced 19th-century reflex theory. He argued that external motions, such as touch and sound, reach the endings of the nerves and affect the animal spirits. For example, heat from fire affects a spot on the skin and sets in motion a chain of reactions, with the animal spirits reaching the brain through the central nervous system, and in turn, animal spirits are sent back to the muscles to move the hand away from the fire. Through this chain of reactions, the automatic reactions of the body do not require a thought process. Above all, he was among the first scientists who believed that the soul should be subject to scientific investigation. He challenged the views of his contemporaries that the soul wasdivine

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.divine< ...

, thus religious authorities regarded his books as dangerous. Descartes' writings went on to form the basis for theories on emotion

Emotions are mental states brought on by neurophysiology, neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or suffering, displeasure. There is currently no scientific ...

s and how cognitive evaluations were translated into affective processes. Descartes believed that the brain resembled a working machine and unlike many of his contemporaries, he believed that mathematics and mechanics could explain the most complicated processes of the mind. In the 20th century, Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical co ...

advanced computer science

Computer science is the study of computation, automation, and information. Computer science spans theoretical disciplines (such as algorithms, theory of computation, information theory, and automation) to Applied science, practical discipli ...

based on mathematical biology as inspired by Descartes. His theories on reflexes also served as the foundation for advanced physiological theories, more than 200 years after his death. The physiologist Ivan Pavlov

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov ( rus, Ива́н Петро́вич Па́влов, , p=ɪˈvan pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈpavləf, a=Ru-Ivan_Petrovich_Pavlov.ogg; 27 February 1936), was a Russian and Soviet experimental neurologist, psychologist and physio ...

was a great admirer of Descartes.

Moral philosophy

For Descartes,ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

was a science, the highest and most perfect of them. Like the rest of the sciences, ethics had its roots in metaphysics. In this way, he argues for the existence of God, investigates the place of man in nature, formulates the theory of mind–body dualism, and defends free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to ac ...

. However, as he was a convinced rationalist, Descartes clearly states that reason is sufficient in the search for the goods that we should seek, and virtue

Virtue ( la, virtus) is moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that shows high moral standards ...

consists in the correct reasoning that should guide our actions. Nevertheless, the quality of this reasoning depends on knowledge, because a well-informed mind will be more capable of making good choices, and it also depends on mental condition. For this reason, he said that a complete moral philosophy should include the study of the body. He discussed this subject in the correspondence with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, and as a result wrote his work ''The Passions of the Soul'', that contains a study of the psychosomatic processes and reactions in man, with an emphasis on emotions or passions.Blom, John J., Descartes. His moral philosophy and psychology. New York University Press. 1978. His works about human passion and emotion would be the basis for the philosophy of his followers (see Cartesianism

Cartesianism is the philosophical and scientific system of René Descartes and its subsequent development by other seventeenth century thinkers, most notably François Poullain de la Barre, Nicolas Malebranche and Baruch Spinoza. Descartes is o ...

), and would have a lasting impact on ideas concerning what literature and art should be, specifically how it should invoke emotion.

Humans should seek the sovereign good that Descartes, following Zeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

, identifies with virtue, as this produces blessedness. For Epicurus, the sovereign good was pleasure, and Descartes says that, in fact, this is not in contradiction with Zeno's teaching, because virtue produces a spiritual pleasure, that is better than bodily pleasure. Regarding Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

's opinion that happiness (eudaimonia) depends on both moral virtue and also on the goods of fortune such as a moderate degree of wealth, Descartes does not deny that fortunes contribute to happiness but remarks that they are in great proportion outside one's own control, whereas one's mind is under one's complete control. The moral writings of Descartes came at the last part of his life, but earlier, in his ''Discourse on the Method'', he adopted three maxims to be able to act while he put all his ideas into doubt. This is known as his "Provisional Morals".

Religion

In the third and fifth ''Meditation'', Descartes offersproofs

Proof most often refers to:

* Proof (truth), argument or sufficient evidence for the truth of a proposition

* Alcohol proof, a measure of an alcoholic drink's strength

Proof may also refer to:

Mathematics and formal logic

* Formal proof, a co ...

of a benevolent God (the trademark argument and the ontological argument respectively). Because God is benevolent, Descartes has faith in the account of reality his senses provide him, for God has provided him with a working mind and sensory system

The sensory nervous system is a part of the nervous system responsible for processing sensory information. A sensory system consists of sensory neurons (including the sensory receptor cells), neural pathways, and parts of the brain involved i ...

and does not desire to deceive him. From this supposition, however, Descartes finally establishes the possibility of acquiring knowledge about the world based on deduction and perception. Regarding epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Epis ...

, therefore, Descartes can be said to have contributed such ideas as a rigorous conception of foundationalism and the possibility that reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

is the only reliable method of attaining knowledge. Descartes, however, was very much aware that experimentation was necessary to verify and validate theories.

Descartes invokes his causal adequacy principle to support his trademark argument for the existence of God, quoting Lucretius in defence: ''"Ex nihilo nihil fit"'', meaning "Nothing comes from nothing

Nothing comes from nothing ( gr, οὐδὲν ἐξ οὐδενός; la, ex nihilo nihil fit) is a philosophical dictum first argued by Parmenides. It is associated with ancient Greek cosmology, such as is presented not just in the works of Homer ...

" (Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into En ...

). ''Oxford Reference'' summarises the argument, as follows, "that our idea of perfection is related to its perfect origin (God), just as a stamp or trademark is left in an article of workmanship by its maker." In the fifth Meditation, Descartes presents a version of the ontological argument which is founded on the possibility of thinking the "idea of a being that is supremely perfect and infinite," and suggests that "of all the ideas that are in me, the idea that I have of God is the most true, the most clear and distinct."

Descartes considered himself to be a devout Catholic, and one of the purposes of the ''Meditations'' was to defend the Catholic faith. His attempt to ground theological beliefs on reason encountered intense opposition in his time. Pascal regarded Descartes' views as a rationalist and mechanist, and accused him of deism: "I cannot forgive Descartes; in all his philosophy, Descartes did his best to dispense with God. But Descartes could not avoid prodding God to set the world in motion with a snap of his lordly fingers; after that, he had no more use for God," while a powerful contemporary, Martin Schoock Martin Schoock (1 April 1614–1669) was a Dutch academic and polymath.

Life

He was born in Utrecht. His grandfather Anton van Voorst taught him Latin. His parents were Remonstrants and intended him for the law; he studied theology and philosophy ...

, accused him of atheist beliefs, though Descartes had provided an explicit critique of atheism in his ''Meditations''. The Catholic Church prohibited his books in 1663.Descartes, René. (2009). ''Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Deluxe Edition''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

Descartes also wrote a response to external world skepticism. Through this method of skepticism, he does not doubt for the sake of doubting but to achieve concrete and reliable information. In other words, certainty. He argues that sensory perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system ...