Rebecca Clarke (composer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rebecca Helferich Clarke (27 August 1886 – 13 October 1979) was a British-American classical composer and violist. Internationally renowned as a viola virtuoso, she also became one of the first female professional orchestral players. Rebecca Clarke claimed both British and American nationalities and spent substantial periods of her life in the United States, where she permanently settled after World War II. She was born in Harrow and studied at the

Rebecca Helferich Clarke (27 August 1886 – 13 October 1979) was a British-American classical composer and violist. Internationally renowned as a viola virtuoso, she also became one of the first female professional orchestral players. Rebecca Clarke claimed both British and American nationalities and spent substantial periods of her life in the United States, where she permanently settled after World War II. She was born in Harrow and studied at the

Clarke was born in Harrow, England, to Joseph Thacher Clarke, an American, and his German wife, Agnes Paulina Marie Amalie Helferich. Her father was interested in music, and Clarke started on violin after sitting in on lessons that were being given to her brother,

Clarke was born in Harrow, England, to Joseph Thacher Clarke, an American, and his German wife, Agnes Paulina Marie Amalie Helferich. Her father was interested in music, and Clarke started on violin after sitting in on lessons that were being given to her brother,

A large portion of Clarke's music features the viola, as she was a professional performer for many years. Much of her output was written for herself and the all-female chamber ensembles she played in, including the Norah Clench Quartet, the English Ensemble, and the d'Aranyi Sisters. She also toured worldwide, particularly with cellist May Mukle. Her works were strongly influenced by several trends in

A large portion of Clarke's music features the viola, as she was a professional performer for many years. Much of her output was written for herself and the all-female chamber ensembles she played in, including the Norah Clench Quartet, the English Ensemble, and the d'Aranyi Sisters. She also toured worldwide, particularly with cellist May Mukle. Her works were strongly influenced by several trends in

Rebecca Clarke Composer homepageThe Rebecca Clarke Society Homepage

*

Songs by Rebecca Clarke on The Art Song Project

Virginia Eskin hosts 'A Note to You' episode on Rebecca Clarke's life & music

{{DEFAULTSORT:Clarke, Rebecca 1886 births 1979 deaths 20th-century classical composers Alumni of the Royal Academy of Music Alumni of the Royal College of Music English classical violists Women violists English classical composers People from Harrow, London People with mood disorders Pupils of Charles Villiers Stanford British women classical composers 20th-century English composers 20th-century English women musicians 20th-century women composers 20th-century violists British emigrants to the United States Composers for viola

Rebecca Helferich Clarke (27 August 1886 – 13 October 1979) was a British-American classical composer and violist. Internationally renowned as a viola virtuoso, she also became one of the first female professional orchestral players. Rebecca Clarke claimed both British and American nationalities and spent substantial periods of her life in the United States, where she permanently settled after World War II. She was born in Harrow and studied at the

Rebecca Helferich Clarke (27 August 1886 – 13 October 1979) was a British-American classical composer and violist. Internationally renowned as a viola virtuoso, she also became one of the first female professional orchestral players. Rebecca Clarke claimed both British and American nationalities and spent substantial periods of her life in the United States, where she permanently settled after World War II. She was born in Harrow and studied at the Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is the oldest conservatoire in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the first Duke ...

and Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music is a conservatoire established by royal charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, UK. It offers training from the undergraduate to the doctoral level in all aspects of Western Music including perform ...

in London. Stranded in the United States at the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, she married composer and pianist James Friskin in 1944. Clarke died at her home in New York at the age of 93.

Although Clarke's output was not large, her work was recognised for its compositional skill and artistic power. Some of her works have yet to be published (and many were only recently published); those that were published in her lifetime were largely forgotten after she stopped composing. Scholarship and interest in her compositions revived in 1976. The Rebecca Clarke Society was established in 2000 to promote the study and performance of her music.

Early life

Clarke was born in Harrow, England, to Joseph Thacher Clarke, an American, and his German wife, Agnes Paulina Marie Amalie Helferich. Her father was interested in music, and Clarke started on violin after sitting in on lessons that were being given to her brother,

Clarke was born in Harrow, England, to Joseph Thacher Clarke, an American, and his German wife, Agnes Paulina Marie Amalie Helferich. Her father was interested in music, and Clarke started on violin after sitting in on lessons that were being given to her brother, Hans Thacher Clarke

Hans Thacher Clarke (27 December 1887 – 21 October 1972) was a prominent biochemist during the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in England where he received his university training, but also studied in Germany and Ireland. He sp ...

, who was 15 months her junior. She began her studies at the Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is the oldest conservatoire in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the first Duke ...

in 1903, but was withdrawn by her father in 1905 after her harmony teacher Percy Hilder Miles

Percy Hilder Miles (12 July 1878 – 18 April 1922) was an English composer, violinist and academic. For most of his career he was Professor of Harmony at the Royal Academy of Music. Among his students at was the composer Rebecca Clarke, and ...

proposed to her. He later left her his Stradivarius

A Stradivarius is one of the violins, violas, cellos and other string instruments built by members of the Italian family Stradivari, particularly Antonio Stradivari (Latin: Antonius Stradivarius), during the 17th and 18th centuries. They are c ...

violin

The violin, sometimes known as a '' fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone ( string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument ( soprano) in the family in regu ...

in his will. She made the first of many visits to the United States shortly after leaving the Royal Academy. She then attended the Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music is a conservatoire established by royal charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, UK. It offers training from the undergraduate to the doctoral level in all aspects of Western Music including perform ...

, becoming one of Sir Charles Villiers Stanford

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (30 September 1852 – 29 March 1924) was an Anglo-Irish composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Romantic era. Born to a well-off and highly musical family in Dublin, Stanford was educated at the ...

's first female composition students. Her substantial ''Theme and Variations'' for piano dates from this period.

At Stanford's urging she shifted her focus from the violin to the viola, just as the latter was coming to be seen as a legitimate solo instrument. She studied with Lionel Tertis

Lionel Tertis, CBE (29 December 187622 February 1975) was an English violist. He was one of the first viola players to achieve international fame and a noted teacher.

Career

Tertis was born in West Hartlepool, the son of Polish-Jewish immigra ...

, who was considered by some the greatest violist of the day. In 1910 she composed a setting of Chinese poetry, called "Tears", in collaboration with a group of fellow students at RCM. She also sang under the direction of Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams, (; 12 October 1872– 26 August 1958) was an English composer. His works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies, written over ...

in a student ensemble organised by Clarke to study and perform Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; grc, Πραίνεστος, ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Pre ...

's music.

Following her criticism of his extra-marital affairs, Clarke's father turned her out of the house and cut off her funds. She had to leave the Royal College in 1910 and supported herself through her viola playing. Clarke (along with Jessie Grimson) became one of the first female professional orchestral musicians when she was selected by Sir Henry Wood

Sir Henry Joseph Wood (3 March 186919 August 1944) was an English conductor best known for his association with London's annual series of promenade concerts, known as the The Proms, Proms. He conducted them for nearly half a century, introd ...

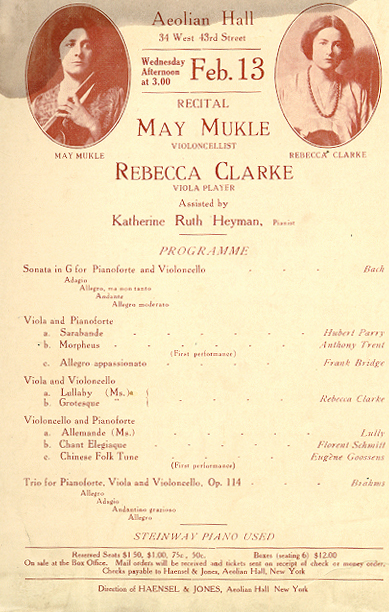

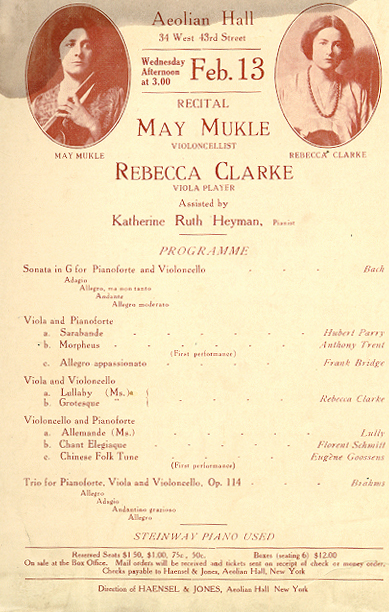

to play in the Queen's Hall Orchestra in 1912. In 1916 she moved to the United States to continue her performing career. A short, lyrical piece for viola and piano entitled ''Morpheus'', composed under the pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individu ...

of "Anthony Trent", was premiered at her 1918 joint recital with cellist May Mukle in New York City. Reviewers praised the "Trent", largely ignoring the works credited to Clarke premiered in the same recital. Her compositional career peaked in a brief period, beginning with the viola sonata

The viola sonata is a sonata for viola, sometimes with other instruments, usually piano. The earliest viola sonatas are difficult to date for a number of reasons:

*in the Baroque era, there were many works written for the viola da gamba, includin ...

she entered in a 1919 competition sponsored by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, Clarke's neighbour and a patron

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

of the arts.

In a field of 72 entrants, Clarke's sonata tied for first place with a composition by Ernest Bloch

Ernest Bloch (July 24, 1880 – July 15, 1959) was a Swiss-born American composer. Bloch was a preeminent artist in his day, and left a lasting legacy. He is recognized as one of the greatest Swiss composers in history. As well as producing music ...

. Coolidge later declared Bloch the winner. Reporters speculated that "Rebecca Clarke" was only a pseudonym for Bloch himself, or at least that it could not have been Clarke who wrote these pieces, as the idea that a woman could write such a beautiful work was socially inconceivable. The sonata was well received and had its first performance at the Berkshire music festival in 1919. In 1921 Clarke again made an impressive showing in Coolidge's composition competition with her piano trio

A piano trio is a group of piano and two other instruments, usually a violin and a cello, or a piece of music written for such a group. It is one of the most common forms found in classical chamber music. The term can also refer to a group of m ...

, though again failed to take the prize. A 1923 rhapsody for cello

The cello ( ; plural ''celli'' or ''cellos'') or violoncello ( ; ) is a bowed (sometimes plucked and occasionally hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually tuned in perfect fifths: from low to high, C2, G2, ...

and piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keyboa ...

followed, sponsored by Coolidge, making Clarke the only female recipient of Coolidge's patronage. These three works represent the height of Clarke's compositional career.

Later life and marriage

Clarke, in 1924, embarked upon a career as a solo and ensemble performer in London, after first completing a world tour in 1922–23. In 1927 she helped form the English Ensemble, a piano quartet that included herself, Marjorie Hayward, Kathleen Long and May Mukle. She also performed on several recordings in the 1920s and 1930s, and participated in BBC music broadcasts. Her compositional output greatly decreased during this period. However, she continued to perform, participating in the Paris Colonial Exhibition in 1931 as part of the English Ensemble. Between 1927 and 1933 she was romantically involved with the Britishbaritone

A baritone is a type of classical male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the bass and the tenor voice-types. The term originates from the Greek (), meaning "heavy sounding". Composers typically write music for this voice in the ...

John Goss, who was eight years her junior and married at the time. He had premiered several of her mature songs, two of which were dedicated to him, "June Twilight" and "The Seal Man". Her "Tiger, Tiger", finished at the time the relationship was ending, proved to be her last composition for solo voice until the early 1940s.

At the outbreak of World War II, Clarke was in the US visiting her two brothers, and was unable to obtain a visa to return to Britain. She lived for a while with her brothers' families and then in 1942 took a position as a governess for a family in Connecticut. She composed 10 works between 1939 and 1942, including her ''Passacaglia on an Old English Tune''. She had first met James Friskin, a composer, concert pianist, and founding member of the Juilliard School

The Juilliard School ( ) is a Private university, private performing arts music school, conservatory in New York City. Established in 1905, the school trains about 850 undergraduate and graduate students in dance, drama, and music. It is widely ...

faculty, and later to become her husband, when they were both students at the Royal College of Music. They renewed their friendship after a chance meeting on a Manhattan street in 1944 and married in September of that year when both were in their late 50s. According to musicologist Liane Curtis, Friskin was "a man who gave larkea sense of deep satisfaction and equilibrium."

Clarke has been described by Stephen Banfield as the most distinguished British female composer of the inter-war generation. However, her later output was sporadic. She had dysthymia

Dysthymia ( ), also known as persistent depressive disorder (PDD), is a mental and behavioral disorder, specifically a disorder primarily of mood, consisting of similar cognitive and physical problems as major depressive disorder, but with l ...

, a chronic form of depression; the lack of encouragement—sometimes outright discouragement—she received for her work also made her reluctant to compose. Clarke did not consider herself able to balance her personal life and the demands of composition: "I can't do it unless it's the first thing I think of every morning when I wake and the last thing I think of every night before I go to sleep." After her marriage, she stopped composing, despite the encouragement of her husband, although she continued working on arrangements until shortly before her death. She also stopped performing.

Clarke sold the Stradivarius she had been bequeathed, and established the May Mukle prize at the Royal Academy. The prize is still awarded annually to an outstanding cellist. After her husband's death in 1967, Clarke began writing a memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobiog ...

, entitled ''I Had a Father Too (or the Mustard Spoon)''; it was completed in 1973 but never published. In it she describes her early life, marked by frequent beatings from her father and strained family relations which affected her perceptions of her proper place in life. Clarke died in 1979 at her home in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

at the age of 93, and was cremated

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre ...

.

Music

A large portion of Clarke's music features the viola, as she was a professional performer for many years. Much of her output was written for herself and the all-female chamber ensembles she played in, including the Norah Clench Quartet, the English Ensemble, and the d'Aranyi Sisters. She also toured worldwide, particularly with cellist May Mukle. Her works were strongly influenced by several trends in

A large portion of Clarke's music features the viola, as she was a professional performer for many years. Much of her output was written for herself and the all-female chamber ensembles she played in, including the Norah Clench Quartet, the English Ensemble, and the d'Aranyi Sisters. She also toured worldwide, particularly with cellist May Mukle. Her works were strongly influenced by several trends in 20th-century classical music

20th-century classical music describes art music that was written nominally from 1901 to 2000, inclusive. Musical style diverged during the 20th century as it never had previously. So this century was without a dominant style. Modernism, impressio ...

. Clarke also knew many leading composers of the day, including Bloch Bloch is a surname of German origin. Notable people with this surname include:

A–F

* (1859-1914), French rabbi

*Adele Bloch-Bauer (1881-1925), Austrian entrepreneur

* Albert Bloch (1882–1961), American painter

* (born 1972), German motor journa ...

and Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

, with whom her work has been compared.

The impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passa ...

of Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most infl ...

is often mentioned in connection with Clarke's work, particularly its lush textures and modernistic harmonies

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. Howev ...

. The Viola Sonata

The viola sonata is a sonata for viola, sometimes with other instruments, usually piano. The earliest viola sonatas are difficult to date for a number of reasons:

*in the Baroque era, there were many works written for the viola da gamba, includin ...

(published in the same year as the Bloch and the Hindemith Viola Sonata) is an example of this, with its pentatonic

A pentatonic scale is a musical scale (music), scale with five Musical note, notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven notes per octave (such as the major scale and minor scale).

Pentatonic scales were developed ...

opening theme, thick harmonies, emotionally intense nature, and dense, rhythm

Rhythm (from Greek , ''rhythmos'', "any regular recurring motion, symmetry") generally means a " movement marked by the regulated succession of strong and weak elements, or of opposite or different conditions". This general meaning of regular re ...

ically complex texture. The Sonata remains a part of standard repertoire for the viola. ''Morpheus

Morpheus ('Fashioner', derived from the grc, μορφή meaning 'form, shape') is a god associated with sleep and dreams. In Ovid's ''Metamorphoses'' he is the son of Somnus and appears in dreams in human form. From the Middle Ages, the name b ...

'', composed a year earlier, was her first expansive work, after over a decade of songs and miniatures. The ''Rhapsody'' that Coolidge sponsored is Clarke's most ambitious work: it is roughly 23 minutes long, with complex musical ideas and ambiguous tonalities contributing to the varying moods of the piece. In contrast, "Midsummer Moon", written the following year, is a light miniature, with a flutter-like solo violin line.

In addition to her chamber music for strings, Clarke wrote many songs. Nearly all of Clarke's early pieces are for solo voice and piano. Her 1933 "Tiger, Tiger", a setting of Blake's poem "The Tyger

"The Tyger" is a poem by the English poet William Blake, published in 1794 as part of his '' Songs of Experience'' collection and rising to prominence in the romantic period. The poem is one of the most anthologised in the English literary can ...

", is dark and brooding, almost expressionist

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it radi ...

. She worked on it for five years to the exclusion of other works during her tumultuous relationship with John Goss and revised it in 1972. Most of her songs, however, are lighter in nature. Her earliest works were parlour songs

Parlour music is a type of popular music which, as the name suggests, is intended to be performed in the parlours of houses, usually by amateur singers and pianists. Disseminated as sheet music, its heyday came in the 19th century, as a result of a ...

, and she went on to build up a body of work drawn primarily from classic texts by Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

, Masefield, and A.E. Housman

Alfred Edward Housman (; 26 March 1859 – 30 April 1936) was an English classical scholar and poet. After an initially poor performance while at university, he took employment as a clerk in London and established his academic reputation by pub ...

.

During 1939 to 1942, the last prolific period near the end of her compositional career, her style became more clear and contrapuntal

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

, with emphasis on motivic elements and tonal structures, the hallmarks of neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism ...

. ''Dumka'' (1941), a recently published work for violin, viola, and piano, reflects the Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

an folk styles of Bartók and Martinů. The " Passacaglia on an Old English Tune", also from 1941 and premiered by Clarke herself, is based on a theme attributed to Thomas Tallis

Thomas Tallis (23 November 1585; also Tallys or Talles) was an English composer of High Renaissance music. His compositions are primarily vocal, and he occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. Tallis is considered one o ...

which appears throughout the work. The piece is modal in flavor, mainly in the Dorian mode

Dorian mode or Doric mode can refer to three very different but interrelated subjects: one of the Ancient Greek ''harmoniai'' (characteristic melodic behaviour, or the scale structure associated with it); one of the medieval musical modes; or—mo ...

but venturing into the seldom-heard Phrygian mode

The Phrygian mode (pronounced ) can refer to three different musical modes: the ancient Greek ''tonos'' or ''harmonia,'' sometimes called Phrygian, formed on a particular set of octave species or scales; the Medieval Phrygian mode, and the modern ...

. The piece is dedicated to "BB", ostensibly Clarke's niece Magdalen; scholars speculate that the dedication is more likely referring to Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

, who organised a concert commemorating the death of Clarke's friend and major influence Frank Bridge

Frank Bridge (26 February 187910 January 1941) was an English composer, violist and conductor.

Life

Bridge was born in Brighton, the ninth child of William Henry Bridge (1845-1928), a violin teacher and variety theatre conductor, formerly a m ...

. The ''Prelude, Allegro, and Pastorale'', also composed in 1941, is another neoclassically influenced piece, written for clarinet and viola (originally for her brother and sister-in-law).

Clarke composed no large scale works such as symphonies. Her total output of compositions comprises 52 songs, 11 choral works, 21 chamber pieces, the Piano Trio, and the Viola Sonata. Her work was all but forgotten for a long period of time, but interest in it was revived in 1976 following a radio broadcast in celebration of her ninetieth birthday. Over half of Clarke's compositions remain unpublished and in the personal possession of her heirs, along with most of her writings. However, in the early 2000s more of her works were printed and recorded. Examples of recent publications include two string quartet

The term string quartet can refer to either a type of musical composition or a group of four people who play them. Many composers from the mid-18th century onwards wrote string quartets. The associated musical ensemble consists of two violinist ...

s and ''Morpheus'', published in 2002.

Modern reception of Clarke's work has been generally positive. A 1981 review of her Viola Sonata called it a "thoughtful, well constructed piece" from a relatively obscure composer; a 1985 review noted its "emotional intensity and use of dark tone colours". Andrew Achenbach, in his review of a Helen Callus

Helen Callus is a British violist who teaches at Northwestern University.

Callus studied with Ian Jewel at the Royal Academy of Music in London, earning an Honorary ARAM (Associate of the RAM). She then continued her studies at the Peabody Co ...

recording of several Clarke works, referred to ''Morpheus'' as "striking" and "languorous". Laurence Vittes noted that Clarke's "Lullaby" was "exceedingly sweet and tender". A 1987 review concluded that "it seems astonishing that such splendidly written and deeply moving music should have lain in obscurity all these years".

The Viola Sonata was the subject of BBC Radio 3

BBC Radio 3 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC. It replaced the BBC Third Programme in 1967 and broadcasts classical music and opera, with jazz, world music, drama, culture and the arts also featuring. The sta ...

's Building a Library survey on 17 October 2015. The top recommendation, chosen by Helen Wallace, was by Tabea Zimmermann

Tabea Zimmermann (born 8 October 1966) is a German violist.

Born in Lahr, she began learning to play the viola at the age of three, and commenced piano studies at age five. At the age of 13, she studied viola with Ulrich Koch at the Conservato ...

(viola) and Kirill Gerstein

Kirill Gerstein (russian: Кирилл Герштейн) (born 23 October 1979) is a Russian-American concert pianist. He is the sixth recipient of the Gilmore Artist Award. Born in the former Soviet Union, Gerstein is an American citizen based in ...

(piano). In 2017 BBC Radio 3 devoted five hours to her music as ''Composer of the Week.''

Rebecca Clarke Society

The Rebecca Clarke Society was established in September 2000 to promote performance, scholarship, and awareness of the works of Rebecca Clarke. Founded bymusicologist

Musicology (from Greek μουσική ''mousikē'' 'music' and -λογια ''-logia'', 'domain of study') is the scholarly analysis and research-based study of music. Musicology departments traditionally belong to the humanities, although some m ...

s Liane Curtis and Jessie Ann Owens

Jessie Ann Owens is an American author and educator. She is a professor of music at University of California, Davis and a former dean of the Division of Humanities, Arts and Cultural Studies. Owens is a recognized musicologist of Renaissance musi ...

and based in the Women's Studies Research Center at Brandeis University

, mottoeng = "Truth even unto its innermost parts"

, established =

, type = Private research university

, accreditation = NECHE

, president = Ronald D. Liebowitz

, p ...

, the Society has promoted recording and scholarship of Clarke's work, including several world premiere performances, recordings of unpublished material, and numerous journal publications.

The Society made available previously unpublished compositions from Clarke's estate. "Binnorie", a twelve-minute song based on Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

ic folklore, was discovered in 1997, and not premiered until 2001. Over 25 previously unknown works have been published since the establishment of the Society. Several of Clarke's chamber works, including the expansive ''Rhapsody'' for cello and piano, and ''Cortège'' for solo piano (1930), dedicated to William Busch and premiered by him, were first recorded in 2000 on the Dutton label, using material from the Clarke estate. In 2002, the Society organised and sponsored the world premieres of the 1907 and 1909 violin sonatas.

The head of the Rebecca Clarke Society, Liane Curtis, is the editor of ''A Rebecca Clarke Reader'', originally published by Indiana University Press in 2004. The book was withdrawn from circulation by the publisher following complaints from the current manager of Clarke's estate about the quotation of unpublished examples from Clarke's writings. However, the ''Reader'' has since been reissued by the Rebecca Clarke Society itself.

Selected works

Chamber music * ''2 Pieces: Lullaby and Grotesque'' for viola (or violin) and cello () * ''Morpheus

Morpheus ('Fashioner', derived from the grc, μορφή meaning 'form, shape') is a god associated with sleep and dreams. In Ovid's ''Metamorphoses'' he is the son of Somnus and appears in dreams in human form. From the Middle Ages, the name b ...

'' for viola and piano (1917–1918)

* Sonata

Sonata (; Italian: , pl. ''sonate''; from Latin and Italian: ''sonare'' rchaic Italian; replaced in the modern language by ''suonare'' "to sound"), in music, literally means a piece ''played'' as opposed to a cantata (Latin and Italian ''canta ...

for viola and piano (1919)

* Piano Trio (1921)

* ''Rhapsody'' for cello and piano (1923)

* ''Passacaglia on an Old English Tune'' for viola (or cello) and piano (?1940–1941)

* ''Prelude, Allegro and Pastorale'' for viola and clarinet (1941)

Vocal

* ''Shiv and the Grasshopper'' for voice and piano (1904); words from ''The Jungle Book

''The Jungle Book'' (1894) is a collection of stories by the English author Rudyard Kipling. Most of the characters are animals such as Shere Khan the tiger and Baloo the bear, though a principal character is the boy or "man-cub" Mowgli, w ...

'' by Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)'' The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

* ''Shy One'' for voice and piano (1912); words by William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

* ''He That Dwelleth in the Secret Place'' (Psalm 91

Psalm 91 is the 91st psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "He that dwelleth in the secret place of the most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty." In Latin, it is known as 'Qui habitat". As a p ...

) for soloists and mixed chorus (1921)

* ''The Seal Man'' for voice and piano (1922); words by John Masefield

John Edward Masefield (; 1 June 1878 – 12 May 1967) was an English poet and writer, and Poet Laureate from 1930 until 1967. Among his best known works are the children's novels ''The Midnight Folk'' and ''The Box of Delights'', and the poem ...

* ''The Aspidistra'' for voice and piano (1929); words by Claude Flight

Walter Claude Flight (born London 16 February 1881 - died Donhead St Andrew 10 October 1955) also known as Claude Flight or W. Claude Flight was a British artist who pioneered and popularised the linoleum cut technique. He also painted, illustrated ...

* ''The Tiger'' for voice and piano (1929–1933); words by William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the Romantic poetry, poetry and visual art of t ...

* ''God Made a Tree'' for voice and piano (1954); words by Katherine Kendall

Choral

* ''Music, When Soft Voices Die'' for mixed chorus (1907); words by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achi ...

References

External links

Rebecca Clarke Composer homepage

*

Songs by Rebecca Clarke on The Art Song Project

Virginia Eskin hosts 'A Note to You' episode on Rebecca Clarke's life & music

{{DEFAULTSORT:Clarke, Rebecca 1886 births 1979 deaths 20th-century classical composers Alumni of the Royal Academy of Music Alumni of the Royal College of Music English classical violists Women violists English classical composers People from Harrow, London People with mood disorders Pupils of Charles Villiers Stanford British women classical composers 20th-century English composers 20th-century English women musicians 20th-century women composers 20th-century violists British emigrants to the United States Composers for viola