The Rattanakosin Kingdom ( th, อาณาจักรรัตนโกสินทร์, , , abbreviated as , ) or Kingdom of Siam were names used to reference the fourth and current

Thai

Thai or THAI may refer to:

* Of or from Thailand, a country in Southeast Asia

** Thai people, the dominant ethnic group of Thailand

** Thai language, a Tai-Kadai language spoken mainly in and around Thailand

*** Thai script

*** Thai (Unicode block ...

kingdom in the

history of Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

(then known as Siam). It was founded in 1782 with the

establishment of Rattanakosin (

Bangkok

Bangkok, officially known in Thai language, Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon and colloquially as Krung Thep, is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estima ...

), which replaced the city of

Thonburi

__NOTOC__

Thonburi ( th, ธนบุรี) is an area of modern Bangkok. During the era of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya, its location on the right (west) bank at the mouth of the Chao Phraya River had made it an important garrison town, which is ...

as the capital of Siam. This article covers the period until the

Siamese revolution of 1932.

The maximum zone of influence of Rattanakosin included the

vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back to ...

s of

Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

,

Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist ...

,

Shan States

The Shan States (1885–1948) were a collection of minor Shan kingdoms called ''muang'' whose rulers bore the title ''saopha'' in British Burma. They were analogous to the princely states of British India.

The term "Shan States" was firs ...

, and the northern

Malay states

The monarchies of Malaysia refer to the constitutional monarchy system as practised in Malaysia. The political system of Malaysia is based on the Westminster parliamentary system in combination with features of a federation.

Nine of the states ...

. The kingdom was founded by

Rama I

Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok Maharaj (, 20 March 1737 – 7 September 1809), personal name Thongduang (), also known as Rama I, was the founder of the Rattanakosin Kingdom and the first monarch of the reigning Chakri dynasty of Siam (now Tha ...

of the

Chakri Dynasty

The Chakri dynasty ( th, ราชวงศ์ จักรี, , , ) is the current reigning dynasty of the Kingdom of Thailand, the head of the house is the king, who is head of state. The family has ruled Thailand since the founding of the ...

. The first half of this period was characterized by the consolidation of the kingdom's power and was punctuated by periodic conflicts with

Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

,

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

and Laos. The second period was one of engagements with the

colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

powers of Britain and France in which Siam remained the only

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

n state to maintain its independence.

Internally the kingdom developed into a modern centralized

nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

with borders defined by interactions with Western powers. Economic and social progress was made, marked by an increase in foreign trade, the abolition of

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and the expansion of formal education to the emerging

middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

. However, the failure to implement substantial political reforms culminated in the

1932 revolution and the abandonment of absolute monarchy in favor of a constitutional monarchy.

History

Early Rattanakosin period (1782–1855)

Foundation of Bangkok

Chakri ruled under the name Ramathibodi, but was generally known as King

Rama I

Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok Maharaj (, 20 March 1737 – 7 September 1809), personal name Thongduang (), also known as Rama I, was the founder of the Rattanakosin Kingdom and the first monarch of the reigning Chakri dynasty of Siam (now Tha ...

, moved the royal seat from

Thonburi

__NOTOC__

Thonburi ( th, ธนบุรี) is an area of modern Bangkok. During the era of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya, its location on the right (west) bank at the mouth of the Chao Phraya River had made it an important garrison town, which is ...

on the West bank of Chao Phraya River to the East bank, the village of

Bang Makok, meaning "place of

olive plums", for better strategic position in defenses against Burmese invasions from the West, protected from attack by the river to the west and by a series of

canals

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or river engineering, engineered channel (geography), channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport watercraft, vehicles (e.g. ...

to the north, east and south. The East bank was low marshlands inhabited by the Chinese, whom King Rama I ordered to move to

Sampheng

Sampheng ( th, สำเพ็ง, ) is a historic neighbourhood and market in Bangkok's Chinatown, in Samphanthawong District. It was settled during the establishment of Bangkok in 1782 by Teochew Chinese, and eventually grew into the surroundi ...

. The official foundation date of

Bangkok

Bangkok, officially known in Thai language, Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon and colloquially as Krung Thep, is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estima ...

was April 21, 1782 when the city pillar was consecrated in a ceremony. King Rama I underwent an abbreviated form of coronation in 1782.

He founded the

Chakri dynasty

The Chakri dynasty ( th, ราชวงศ์ จักรี, , , ) is the current reigning dynasty of the Kingdom of Thailand, the head of the house is the king, who is head of state. The family has ruled Thailand since the founding of the ...

and made his younger brother Chao Phraya Surasi the ''Wangna'' or Prince

Sura Singhanat of the

Front Palace

Krom Phra Ratchawang Bowon Sathan Mongkhon , colloquially known as the Front Palace ( th, วังหน้า, ), was the title of the ''uparaja'' of Siam, variously translated as "viceroy", "vice king" or "Lord/Prince of the Front Palace", as ...

. In 1783, Bangkok city walls were constructed with part of the bricks taken from Ayutthaya ruins.

Lao and Cambodian

laborers were assigned to dig the city moat. The

Grand Palace

The Grand Palace ( th, พระบรมมหาราชวัง, Royal Institute of Thailand. (2011). ''How to read and how to write.'' (20th Edition). Bangkok: Royal Institute of Thailand. .) is a complex of buildings at the heart of Ban ...

and the

Wat Phra Kaew

Wat Phra Kaew ( th, วัดพระแก้ว, , ), commonly known in English as the Temple of the Emerald Buddha and officially as Wat Phra Si Rattana Satsadaram, is regarded as the most sacred Buddhist temple in Thailand. The complex co ...

were completed in 1784 and the

Emerald Buddha

The Emerald Buddha ( th, พระแก้วมรกต , or ) is an image of the meditating Gautama Buddha seated in a meditative posture, made of a semi-precious green stone (jasper rather than emerald or jade), clothed in gold. and about ...

was transferred from

Wat Arun

Wat Arun Ratchawararam Ratchawaramahawihan ( th, วัดอรุณราชวราราม ราชวรมหาวิหาร ) or Wat Arun (, "Temple of Dawn") is a Buddhist temple (''wat'') in Bangkok Yai district of Bangkok, Tha ...

to be placed in Wat Phra Kaew. In 1785, King Rama I performed full coronation ceremony and named the new city "Rattanakosin", which meant the "Jewel of Indra" referring to the Emerald Buddha.

Burmese wars

The Burmese continued to pose the major threat to Siamese state of existence. In 1785, King

Bodawpaya

Bodawpaya ( my, ဘိုးတော်ဘုရား, ; th, ปดุง; 11 March 1745 – 5 June 1819) was the sixth king of the Konbaung dynasty of Burma. Born Maung Shwe Waing and later Badon Min, he was the fourth son of Alaungpaya, fou ...

of the Burmese

Konbaung dynasty

The Konbaung dynasty ( my, ကုန်းဘောင်ခေတ်, ), also known as Third Burmese Empire (တတိယမြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်) and formerly known as the Alompra dynasty (အလောင်းဘ ...

sent massive armies to invade Siam in five directions in the

Nine Armies' War. Decades of continuous warfare had left Siam depopulated and the Siamese court managed to muster only the total of 70,000 men

against the 144,000 men of Burmese invaders. The Burmese, however, were over-stretched and unable to converge. Prince Sura Singhanat led his army to defeat the main army of King Bodawpaya in the Battle of Latya in

Kanchanaburi

Kanchanaburi ( th, กาญจนบุรี, ) is a town municipality (''thesaban mueang'') in the west of Thailand and part of Kanchanaburi Province. In 2006 it had a population of 31,327. That number was reduced to 25,651 in 2017. The town ...

in 1786. In the north, the Burmese laid siege on Lanna

Lampang

Lampang, also called Nakhon Lampang ( th, นครลำปาง, ) to differentiate from Lampang province, is the third largest city in northern Thailand and capital of Lampang province and the Mueang Lampang district. Traditional names for La ...

.

Kawila

Kawila ( th, กาวิละ, , nod, , 31 October 17421816), also known as Phra Boromrachathibodi ( th, พระบรมราชาธิบดี), was the Northern Thai ruler of Chiangmai Kingdom and the founder of Chetton Dynasty. Orig ...

the ruler of Lampang managed to hold the siege for four months until relief forces from Bangkok came to rescue Lampang. In the south,

Lady Chan and Lady Mook were able to fend off Burmese attacks on Thalang (

Phuket

Phuket (; th, ภูเก็ต, , ms, Bukit or ''Tongkah''; Hokkien:普吉; ) is one of the southern provinces (''changwat'') of Thailand. It consists of the island of Phuket, the country's largest island, and another 32 smaller islands of ...

) in 1786. After the unfruitful campaign, King Bodawpaya of Burma sent his son ''

Uparaja

Uparaja or Ouparath, also Ouparaja ( my, ဥပရာဇာ ; km, ឧបរាជ, ; th, อุปราช, ; lo, ອຸປຮາດ, ''Oupahat''), was a royal title reserved for the viceroy in the Buddhist dynasties in Burma, Cambodia, and ...

''

Thado Minsaw

Thado Minsaw ( my, သတိုးမင်းစော ; 15 June 1762 – 9 April 1808), also known as Shwedaung Min (), was heir-apparent of Burma from 1783 to 1808, during the reign of his father King Bodawpaya of Konbaung dynasty. As Prin ...

to invade Kanchanaburi concentrating only in one direction. King Rama I and his brother Prince Sura Singhanat defeated the Burmese in the

Tha Dindaeng Campaign in 1786–1787.

After victories over Burmese invaders, Siam

staged the offensives on the

Tenasserim Coast

Tanintharyi Region ( my, တနင်္သာရီတိုင်းဒေသကြီး, ; Mon: or ; ms, Tanah Sari; formerly Tenasserim Division and subsequently Tanintharyi Division, th, ตะนาวศรี, RTGS: ''Tanao Si'', ...

,

which was the former territory of Ayutthaya. King Rama I marched Siamese armies to lay siege on

Tavoy

Dawei (, ; mnw, ဓဝဲါ, ; th, ทวาย, RTGS: ''Thawai'', ; formerly known as Tavoy) is a city in south-eastern Myanmar and is the capital of the Tanintharyi Region, formerly known as the Tenasserim Division, on the northern bank of ...

in 1788

but did not succeed. In 1792, the Burmese governors of Tavoy and

Mergui

Myeik (, or ; mnw, ဗိက်, ; th, มะริด, , ; formerly Mergui, ) is a rural city in Tanintharyi Region in Myanmar (Burma), located in the extreme south of the country on the coast off an island on the Andaman Sea. , the estimate ...

defected to Siam.

Siam came to temporarily occupy the Tenasserim Coast. However, as the court was preparing for the invasions of Lower Burma,

King Bodawpaya sent his son Thado Minsaw to reclaim Tenasserim.

The Siamese were soundly defeated by the Burmese in the Battle of Tavoy in 1793 and ceded the Tenasserim Coast to Burma

for perpetuity, becoming modern

Tanintharyi Division

Tanintharyi Region ( my, တနင်္သာရီတိုင်းဒေသကြီး, ; Mon: or ; ms, Tanah Sari; formerly Tenasserim Division and subsequently Tanintharyi Division, th, ตะนาวศรี, RTGS: ''Tanao Si'', ; ...

.

Lord Kawila was finally able to re-establish

Chiang Mai

Chiang Mai (, from th, เชียงใหม่ , nod, , เจียงใหม่ ), sometimes written as Chiengmai or Chiangmai, is the largest city in northern Thailand, the capital of Chiang Mai province and the second largest city in ...

as the centre of Lanna in 1797. King Bodawpaya was eager to regain Burmese control over Lanna.

The Burmese invaded Chiang Mai in 1797 and 1802,

in both occasions Kawila defended the city and Prince Sura Singhanat marched north to relieve Chiang Mai.

The Siamese and Lanna forces then proceeded to capture

Chiang Saen Chiang Saen may refer to:

* Chiang Saen District, in Chiang Rai Province, northern Thailand

* Chiang Saen, a capital of the ancient Lanna

The Lan Na Kingdom ( nod, , , "Kingdom of a Million Rice Fields"; th, อาณาจักรล้� ...

, the stronghold of Burmese authority in Lanna, in 1804,

eliminating Burmese influence in Lanna. Siamese victories over the Burmese in Lanna allowed Siam to expand domination north towards the northernmost Tai princedoms:

Keng Tung

th , เชียงตุง

, other_name = Kyaingtong

, settlement_type = Town

, imagesize =

, image_caption =

, pushpin_map = Myanmar

, pushpin_label_position = left

, ...

and

Chianghung. Kawila of Chiang Mai sent forces to raid Keng Tung and

Mong Hsat

Mong Hsat ( Burmese: မိုင်းဆတ်မြို့, MLCTS: ''muing.chat.mrui'') is a town in the Shan State of Myanmar, the capital of Mong Hsat Township. It is served by Monghsat Airport.

History

Monghsat State (Mönghsat, where ...

in 1802 and subjugated

Mong Yawng

Mong Yawng ( my, မိုင်းယောင်းမြို့) is a town, located in eastern Shan State, Myanmar.

History

Mongyawng State (Möngyawng) was one of the Shan States

The Shan States (1885–1948) were a collection of ...

, Mueang Luang Phukha, and

Chiang Hung

Chiang Hung, Sipsongpanna or Keng Hung ( th, เมืองหอคำเชียงรุ่ง; Mueang Ho Kham Chiang Rung, zh, 車里 or 江洪) was one of the states of Shans under the suzerainty of Burma and China.

Chiang Hung was inh ...

in 1805.

In 1805, the Prince of Nan invaded the

Tai Lue confederacy of

Sipsongpanna

Xishuangbanna, Sibsongbanna or Sipsong Panna ( Tham: , New Tai Lü script: ; ; th, สิบสองปันนา; lo, ສິບສອງພັນນາ; shn, သိပ်းသွင်ပၼ်းၼႃး; my, စစ်ဆောင်� ...

and Chiang Hung surrendered.

Prince Sura Singhanat of the Front Palace died in 1803. King Rama I appointed his own son Prince Itsarasunthon

as the succeeding Prince of the Front Palace in 1806. King Rama I died in 1809 and Prince Itsarasunthon ascended to become King

Rama II

Phra Phutthaloetla Naphalai ( th, พระพุทธเลิศหล้านภาลัย, 24 February 1767 – 21 July 1824), personal name Chim ( th, ฉิม), also styled as Rama II, was the second monarch of Siam under the Chakri ...

.

King Bodawpaya then took the opportunity to initiate the

Burmese invasion of Thalang on the Andaman Coast. Bangkok court sent armies to relieve Thalang but faced logistic difficulties before when Thalang fell to the Burmese in 1810.

The Siamese were able to repel the Burmese from Thalang anyway. The Burmese Invasion of Phuket in 1809-1810 was the last Burmese incursion into Siamese territories in Thai history. Siam remained vigilant of prospective Burmese invasions through the 1810s. Only when Burma ceded Tenasserim to the British in the

Treaty of Yandabo

The Treaty of Yandabo ( my, ရန္တပိုစာချုပ် ) was the peace treaty that ended the First Anglo-Burmese War. The treaty was signed on 24February 1826, nearly two years after the war formally broke out on 5March 1824, by ...

in 1826 in aftermath of the

First Anglo-Burmese War

The First Anglo-Burmese War ( my, ပထမ အင်္ဂလိပ်-မြန်မာ စစ်; ; 5 March 1824 – 24 February 1826), also known as the First Burma War, was the first of three wars fought between the British and Burmese ...

that Burmese threats effectively ended.

Eastern fronts: Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam

When the Siamese forces

took Vientiane in 1779 in Thonburi period, all three Lao kingdoms of

Luang Phrabang

Luang Phabang, ( Lao: ຫລວງພະບາງ/ ຫຼວງພະບາງ) or ''Louangphabang'' (pronounced ), commonly transliterated into Western languages from the pre-1975 Lao spelling ຫຼວງພຣະບາງ (ຣ = silent r) ...

,

Vientiane

Vientiane ( , ; lo, ວຽງຈັນ, ''Viangchan'', ) is the capital and largest city of Laos. Vientiane is divided administratively into 9 cities with a total area of only approx. 3,920 square kilometres and is located on the banks of ...

and

Champasak came under Siamese domination. Lao Princes

Nanthasen

Nanthasen (also spelled Nanthasan; lo, ພຣະເຈົ້ານັນທະເສນ, died 1795), also known as Chao Nan, was the 6th king of the Kingdom of Vientiane. He ruled from 1781 to 1795.

Nanthasen was the eldest son of his father Ong ...

,

Inthavong

Chao Inthavong ( lo, ເຈົ້າອິນທະວົງສ໌; th, เจ้าอินทวงศ์; died 7 February 1805), or known as his regnal name Xaiya Setthathirath III, was the 5th king of the Kingdom of Vientiane (r. 1795 to 1805 ...

and

Anouvong

Chao Anouvong ( lo, ເຈົ້າອານຸວົງສ໌; th, เจ้าอนุวงศ์; ), or regnal name Xaiya Setthathirath V ( lo, ໄຊຍະເສດຖາທິຣາຊທີ່ຫ້າ; th, ไชยเชษฐาธ� ...

were taken as hostages to Bangkok. In 1782, King Rama I installed Nanthasen as King of Vientiane. However, Nanthasen was dethroned in 1795

due to his alleged diplomatic overtures with

Tây Sơn dynasty

The Tây Sơn dynasty (, vi, Nhà Tây Sơn (Chữ Nôm: 茹西山); vi, Tây Sơn triều ( Hán tự: 西山朝) was a ruling dynasty of Vietnam, founded in the wake of a rebellion against both the Nguyễn lords and the Trịnh lords befor ...

in favor of Inthavong. When King Inthavong died in 1804, Anouvong succeeded as King of Vientiane.

Yumreach Baen, a pro-Siamese Cambodian noble, staged a coup in Cambodia to overthrow and kill the pro-Vietnamese Cambodian Prime Minister

Tolaha Mu in 1783. Chaos and upheavals that ensued caused Yumreach Baen to take young King

Ang Eng

Ang Eng ( km, អង្គអេង ; 1773 – 5 May 1796) was King of Cambodia from 1779 to his death in 1796. He reigned under the name of Neareay Reachea III ( km, នារាយណ៍រាជាទី៣, link=no).

Ang Eng was a son of Out ...

to Bangkok. King Rama I appointed Yumreach Baen as

Chaophraya Aphaiphubet. Also in 1783,

Nguyễn Phúc Ánh

Gia Long ( (''North''), (''South''); 8 February 1762 – 3 February 1820), born Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (阮福暎) or Nguyễn Ánh, was the founding emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty, the last dynasty of Vietnam. His dynasty would rule the unifie ...

arrived in Bangkok to take refuge from the Tây Sơn. In 1784, Siamese forces invaded Saigon to reinstate Nguyễn Phúc Ánh but were defeated in the

Battle of Rạch Gầm-Xoài Mút

Lê Văn Duyệt Lê Văn QuânNguyễn Văn Thành Nguyễn Văn Oai Mạc Tử Sinh

, units1 = Tây Sơn Army

, units2 = Siamese Army Siamese Navy Nguyễn Ánh's forces

, strength1 = 30,000 men55 warships100 ...

by the Tây Sơn. In 1789, Aphaiphubet took control of Cambodia and became the Regent. Also in the same year Nguyễn Phúc Ánh took Saigon and established himself in Southern Vietnam. In 1794, King Rama I allowed Ang Eng to return to Cambodia to rule as king

and carved northwestern part of Cambodia including

Battambang

Battambang ( km, បាត់ដំបង, UNGEGN: ) is the capital of Battambang Province and the third largest city in Cambodia.

Founded in the 11th century by the Khmer Empire, Battambang is the leading rice-producing province of the coun ...

and

Siemreap

Siem Reap ( km, សៀមរាប, ) is the second-largest city of Cambodia, as well as the capital and largest city of Siem Reap Province in northwestern Cambodia.

Siem Reap has French colonial and Chinese-style architecture in the Old F ...

for Aphaiphubet to govern as the governor of Battambang under direct Siamese rule.

King Ang Eng of Cambodia died in 1796 and was succeeded by his son

Ang Chan who became pro-Vietnamese.

Pro-Siamese Prince Ang Sngoun, younger brother of Ang Chan,

decided to rebel against his brother in 1811. The Siamese forces marched from Battambang to

Oudong

( km, ឧដុង្គ; also romanized as Udong or Odong) is a former town of the post-Angkorian period (1618–1863) situated in present-day ''Phsar Daek'' Commune, Ponhea Lueu District, Kandal Province, Cambodia. Located at the foothill of th ...

. The panicked King Ang Chan fled to take refuge at Saigon under the protection of Vietnam. Siamese forces sacked Oudong and returned.

Lê Văn Duyệt

Lê Văn Duyệt)., group=n (1763 or 1764 – 30 July 1832) was a Vietnamese general who helped Nguyễn Ánh—the future Emperor Gia Long—put down the Tây Sơn wars, unify Vietnam and establish the Nguyễn dynasty. After the Nguyễn came ...

brought Ang Chan back to

Phnom Penh

Phnom Penh (; km, ភ្នំពេញ, ) is the capital and most populous city of Cambodia. It has been the national capital since the French protectorate of Cambodia and has grown to become the nation's primate city and its economic, indus ...

to rule under Vietnamese influence.

King Anouvong of Vientiane

rebelled

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

against Siam in 1827. He led the Lao armies to capture

Nakhon Ratchasima

Nakhon Ratchasima ( th, นครราชสีมา, ) is one of the four major cities of Isan, Thailand, known as the "big four of Isan". The city is commonly known as Korat (, ), a shortened form of its name. It is the governmental seat of ...

and

Saraburi

Saraburi City (''thesaban mueang'') is the provincial capital of Saraburi Province in central Thailand. In 2020, it had a population of 60,809 people, and covers the complete ''tambon'' Pak Phriao of the Mueang Saraburi district.

Location

Sa ...

,

while his son King

Raxabut Nyô of Champasak invaded Southern Isan. Phraya Palat and his wife

Lady Mo

Thao Suranari ( th, ท้าวสุรนารี; 1771–1852) is the royally bestowed title of Lady Mo, also known as Ya Mo (, who was the wife of the deputy governor of Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat), the stronghold of Siamese control over ...

led the Siamese captives to rise against their Laos overseers in the

Battle of Samrit Fields. King Rama III sent

Prince Sakdipolsep of the Front Palace to defeat Anouvong at

Nong Bua Lamphu

Nong Bua Lam Phu () is a town in Thailand, capital of Nong Bua Lamphu Province. It is on the central eastern border of the province, approximately 45 kilometers south-west of the city of Udon Thani and from there, accessed by route 210. The town l ...

and Phraya Ratchasuphawadi

(later

Chaophraya Bodindecha

''Chao Phraya'' Bodindecha ( th, เจ้าพระยาบดินทรเดชา, km, ចៅ ឃុន បឌិន, 13 January 1776 – 24 June 1849), personal name Sing Sinhaseni (), was a prominent military figure of the early Rat ...

) to capture Raxabut Nyô. Anouvong and his family fled to

Nghệ An Province of Vietnam under protection of Emperor Ming Mạng. Ming Mạng sent Anouvong back to Vientiane to negotiate with Siam. However, Anouvong retook control of Vientiane only to be pushed back by Phraya Ratchasuphawadi in 1828. Anouvong was eventually captured and sent to Bangkok where he was imprisoned and died in 1829.

Anouvong's rebellion worsened Siamese-Vietnamese relations. Lê Văn Duyệt died in 1832 and his posthumous punishments by Ming Mạng spurred the

Lê Văn Khôi rebellion at Saigon in 1833. King Rama III took the opportunity to eliminate Vietnamese influence in the region. He assigned Chaophraya Bodindecha to lead armies to invade Cambodia and Saigon, while

Chaophraya Phrakhlang led the fleet. However, the Siamese forces were defeated in the naval Battle of Vàm Nao and retreated. The Siamese defeat confirmed Vietnamese domination over Cambodia. Ming Mạng annexed Cambodia into

Trấn Tây Province with

Trương Minh Giảng

Trương Minh Giảng ( vi-hantu, 張明講, 1792 – 1841) was a general and official of Vietnam during the Nguyễn dynasty.

Early life

Trương-Minh Giảng was born in Gia Định (modern Ho Chi Minh City). He came from an important aristocr ...

as the governor. After the death of Ang Chan, Minh Mạng also installed

Ang Mey

Ang Mey ( km, អង្គម៉ី ; 1815 – December 1874) was a Monarchy of Cambodia, monarch of Cambodia. Her official title was Samdech Preah Mahā Rājinī Ang Mey. She was one of few female rulers in History of Cambodia, Cambodia's hist ...

as puppet queen regnant of Cambodia. In 1840, the Cambodians arose in general rebellion against Vietnamese domination. Bodindecha marched Siamese armies to attack

Pursat

Pursat ( ; km, ពោធិ៍សាត់, ) is the capital of Pursat Province, Cambodia. Its name derived from a type of tree. It lies on the Pursat River. The city is famous as the place of mythical 16th century ''neak ta'' of Khleang Moeu ...

and

Kampong Svay in 1841. The new Vietnamese Emperor

Thiệu Trị

Thiệu Trị (, vi-hantu, 紹 治, lit. "inheritance of prosperity"; 6 June 1807 – 4 November 1847), personal name Nguyễn Phúc Miên Tông or Nguyễn Phúc Tuyền, was the third emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty. He was the eldest son of Em ...

ordered the Vietnamese to retreat and the Siamese took over Cambodia. The war resumed in 1845 when Emperor Thiệu Trị sent

Nguyễn Tri Phương

Nguyễn Tri Phương ( vi-hantu, 阮知方, 1800 – 1873), born Nguyễn Văn Chương, was a Nguyễn dynasty mandarin and military commander. He commanded armies against French conquest of Vietnam at the Siege of Tourane, the Siege of Sai ...

to successfully take Phnom Penh and lay siege on Siamese-held Oudong. After months of siege, Siam and Vietnam negotiated for peace with Prince

Ang Duong

Ang Duong ( km, អង្គឌួង ; 12 June 1796 – 19 October 1860) was the King of Cambodia from 1841 to 1844 and from 1845 to his death in 1860. Formally invested in 1848, his rule benefited a kingdom that suffered from several centuries ...

, who would recognize both Siamese and Vietnamese suzerainty, installed as the new King of Cambodia in 1848.

Malay Peninsula and Contacts with the West

After the Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767, the Northern Malay states that used to pay

''bunga mas'' tributes to Siam were freed temporarily from Siamese domination.

In 1786, after expelling Burmese invaders from

Southern Siam,

Prince Sura Singhanat declared that Northern Malay sultanates should resume tributary obligations as it had used to be during the Ayutthaya times.

Kedah

Kedah (), also known by its honorific Darul Aman (Islam), Aman and historically as Queda, is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia, located in the northwestern part of Peninsular Malaysia. The state covers a total area ...

and

Terengganu

Terengganu (; Terengganu Malay: ''Tranung'', Jawi: ), formerly spelled Trengganu or Tringganu, is a sultanate and constitutive state of federal Malaysia. The state is also known by its Arabic honorific, ''Dāru l- Īmān'' ("Abode of Faith"). ...

resolved to send tributes but

Pattani refused. The Siamese prince then sent armies to sack Pattani in 1786, bringing Pattani into Siamese rule.

Malay states of Pattani, Kedah and Terengganu (including

Kelantan

Kelantan (; Jawi: ; Kelantanese Malay: ''Klate'') is a state in Malaysia. The capital is Kota Bharu and royal seat is Kubang Kerian. The honorific name of the state is ''Darul Naim'' (Jawi: ; "The Blissful Abode").

Kelantan is located in the ...

, which was then part of Terengganu) came under Siamese suzerainty as

tributary states

A tributary state is a term for a pre-modern state in a particular type of subordinate relationship to a more powerful state which involved the sending of a regular token of submission, or tribute, to the superior power (the suzerain). This to ...

. Pattani rebelled in 1789–1791 and 1808. Siam ended up dividing Pattani into seven distinct townships to rule. Kelantan was separated from Terengganu in 1814. In 1821,

Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin Halim Shah (known in Thai sources as Tuanku Pangeran) of Kedah was found forging alliance with Burma – Siam's archnemesis. Siamese forces under

Phraya Nakhon Noi the "Raja of Ligor"

invaded and captured Kedah. The Kedah sultan took refuge in British-held

Penang

Penang ( ms, Pulau Pinang, is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, by the Malacca Strait. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the Malay ...

. A son of Nakhon Noi was installed as the governor of Kedah. The Kedah sultanate ceased to exist for a time being.

Since the fifteenth century, the Siamese royal court had retained monopoly on foreign trades through the ''Phra Khlang Sinkha''

or Royal Warehouse.

Foreign merchants had to present their ships and goods at ''Phra Khlang Sinkha'' for tariffs to be levied and goods to be purchased by the Royal Warehouse. Foreigners could not directly and privately trade important profitable government-restricted goods with the native Siamese. In 1821, the Governor-General of

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

, in the mission to establish trade contacts with Siam, sent

John Crawfurd

John Crawfurd (13 August 1783 – 11 May 1868) was a Scottish physician, colonial administrator, diplomat, and author who served as the second and last Resident of Singapore.

Early life

He was born on Islay, in Argyll, Scotland, the son of S ...

to Bangkok.

Crawfurd arrived in Bangkok in 1822, delivering the British concern for Kedah sultan and demands for trade concessions, which turned negotiation soured. Siam sent military troops to aid the British in

Tenasserim in the

First Anglo-Burmese War

The First Anglo-Burmese War ( my, ပထမ အင်္ဂလိပ်-မြန်မာ စစ်; ; 5 March 1824 – 24 February 1826), also known as the First Burma War, was the first of three wars fought between the British and Burmese ...

. However, a dispute prompted King Rama III to withdraw the Siamese armies from Burma. In 1825, the British sent another mission led by

Henry Burney

Henry Burney (27 February 1792 – 4 March 1845) or Hantri Barani ( th, หันตรีบารนี) in Thai, was a British commercial traveller and diplomat for the British East India Company. His parents were Richard Thomas Burney (1768 ...

to Bangkok.

The Anglo-Siamese

Burney Treaty

The treaty between Kingdom of Siam and Great Britain commonly known as the Burney Treaty was signed at Bangkok on 20 June 1826 by Henry Burney, an agent of British East India Company, for Britain, and King Rama III for Siam. It followed an earlie ...

was ratified in 1826,

in which centuries-old royal Siamese monopoly over Western trades was ended

with the British granted to trade freely in Siam. The treaty also recognized Siamese claims over Kedah.

However, some trade restrictions including the ''Phasi Pak Ruea'' or measurement duties were still intact. Siam also concluded the similar "

Roberts Treaty" with the United States in 1833.

Tunku Kudin, a nephew of the former Kedah sultan, reclaimed Kedah by force in 1831 and rose up against Siam. Pattani, Kelantan and Terengganu joined on Kedahan side against Siam. King Rama III sent forces under Nakhon Noi and a navy fleet under

Chaophraya Phrakhlang to put down Malay insurgency. The Raja of Ligor recaptured Kedah in 1832. In 1838, Tunku Muhammad Sa'ad, another nephew of the Kedah sultan, in concert with Wan Muhammad Ali (called Wan Mali in Thai sources) the

Andaman Sea

The Andaman Sea (historically also known as the Burma Sea) is a marginal sea of the northeastern Indian Ocean bounded by the coastlines of Myanmar and Thailand along the Gulf of Martaban and west side of the Malay Peninsula, and separated from ...

adventurer, again retook

Alor Setar

Alor Setar ( Jawi: الور ستار, Kedahan: ''Loqstaq'') is the state capital of Kedah, Malaysia. It is the second-largest city in the state after Sungai Petani and one of the most-important cities on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia ...

from the Siamese. Kedahan forces invaded Southern Siam, attacking

Trang,

Pattani and

Songkhla

Songkhla ( th, สงขลา, ), also known as Singgora or Singora (Pattani Malay: ซิงกอรอ), is a city (''thesaban nakhon'') in Songkhla Province of southern Thailand, near the border with Malaysia. Songkhla lies south of Ba ...

. King Rama III sent fleet, led by

Phraya Siphiphat (younger brother of Phrakhlang), to quell the rebellion. Siamese forces recaptured Alor Setar in 1839. Chaophraya Nakhon Noi the Raja of Ligor died in 1838, leaving Malay affairs to Phraya Siphiphat. Siphiphat divided Kedah into four states:

Setul

Setul, officially the Kingdom of Setul Mambang Segara ( ms, Kerajaan Setul Mambang Segara; Jawi: ; ; ) was a traditional Malay kingdom founded in the northern coast of the Malay Peninsula. The state was established in 1808 in wake of the par ...

,

Kubang Pasu,

Perlis

Perlis, ( Northern Malay: ''Peghelih''), also known by its honorific title Perlis Indera Kayangan, is the smallest state in Malaysia by area and population. Located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, it borders the Thai provinces o ...

and Kedah proper. The former Kedah sultan reconciled and he was finally restored as Sultan of Kedah in 1842. Journey of Phraya Siphiphat to the south in 1839 coincided with the

Kelantanese Civil War. Sultan Muhammad II of Kelantan had conflicts with his rival contender Tuan Besar

and requested for military aid from Phraya Siphiphat. Siphiphat, however, posted himself as the negotiator and forced peace agreement upon warring Kelantan factions.

Tuan Besar arose again in 1840. Siam resolved to move Tuan Besar to somewhere else to placate the conflicts. Eventually, Tuan Besar was made the ruler of Pattani in 1842,

becoming Sultan Phaya Long Muhammad of Pattani. Descendants of Phaya Long Muhammad would continue to rule Pattani until 1902.

After the

First Opium War

The First Opium War (), also known as the Opium War or the Anglo-Sino War was a series of military engagements fought between Britain and the Qing dynasty of China between 1839 and 1842. The immediate issue was the Chinese enforcement of the ...

,

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

emerged as the most powerful maritime power in the region and was eager for more favorable trade agreements. Both the British and the Americans sent their delegates to Bangkok in 1850 to propose treaty amendments for abolition of all commercial restrictions but were not successful. Only with the

Bowring Treaty

The Bowring Treaty was a treaty signed between the British Empire and the Kingdom of Siam on 18 April 1855. The treaty had the primary effect of liberalizing foreign trade in Siam, and was signed by five Siamese plenipotentiaries (among them Won ...

of 1855 that these goals were achieved, liberalizing Siamese economy

and ushering new period of Thai history. King Rama III reportedly said on his deathbed in 1851: "''...there will be no more wars with Vietnam and Burma. We will have them only with the West.''".

King Mongkut

Mongkut ( th, มงกุฏ; 18 October 18041 October 1868) was the fourth monarch of Siam (Thailand) under the House of Chakri, titled Rama IV. He ruled from 1851 to 1868. His full title in Thai was ''Phra Bat Somdet Phra Menthora Ramathibod ...

, who had been a Buddhist monk for twenty-seven years,

ascended the throne in 1851 with supports from

Bunnag family

The House of Bunnag ( th, บุนนาค; ) was a powerful Siamese noble family of Mon- Persian descent influential during the late Ayutthaya kingdom and early Rattanakosin period. Originally of Persian Islamic descent, they converted en masse ...

.

King Mongkut made his younger brother

Pinklao

Pinklao ( th, ปิ่นเกล้า) (September 4, 1808 – January 7, 1866) was the viceroy of Siam. He was the younger brother of Mongkut, King Rama IV, who crowned him as a monarch with equal honor to himself.

Early life

Prince Chutaman ...

the Vice-King or Second King

of the Front Palace. Mongkut also granted the exceptionally high rank of ''Somdet Chaophraya''

to the Bunnag brothers –

Chaophraya Phrakhlang (Dit Bunnag) and

Phraya Siphiphat (That Bunnag),

who became

Somdet Chaophraya Prayurawong and

Somdet Chaophraya Phichaiyat, respectively, cementing the roles and powers of Bunnag family in Siamese foreign affairs in mid-nineteenth century. Chuang Bunnag, Prayurawong's son, also became

Chaophraya Si Suriyawong

Somdet Chaophraya Borom Maha Sri Suriwongse ( th, สมเด็จเจ้าพระยาบรมมหาศรีสุริยวงศ์, , ; also spelled ''Suriyawong'', etc.; 23 December 1808 – 19 January 1883), whose personal ...

.

Early Modern Siam (1855–1905)

Bowring Treaty and Siamese Missions to Europe

King Mongkut

Mongkut ( th, มงกุฏ; 18 October 18041 October 1868) was the fourth monarch of Siam (Thailand) under the House of Chakri, titled Rama IV. He ruled from 1851 to 1868. His full title in Thai was ''Phra Bat Somdet Phra Menthora Ramathibod ...

and

Chaophraya Si Suriyawong (Chuang Bunnag) realized that, due to geopolitical situation, Siam could stand no more against British demands for concessions.

Sir John Bowring

Sir John Bowring , or Phraya Siamanukulkij Siammitrmahayot, , , group=note (17 October 1792 – 23 November 1872) was a British political economist, traveller, writer, literary translator, polyglot and the fourth Governor of Hong Kong. He was a ...

the

Governor of Hong Kong

The governor of Hong Kong was the representative of the British Crown in Hong Kong from 1843 to 1997. In this capacity, the governor was president of the Executive Council and commander-in-chief of the British Forces Overseas Hong Kong. ...

, who was the delegate of

Aberdeen government in London rather than the

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

,

arrived at Bangkok in 1855.

The

Bowring Treaty

The Bowring Treaty was a treaty signed between the British Empire and the Kingdom of Siam on 18 April 1855. The treaty had the primary effect of liberalizing foreign trade in Siam, and was signed by five Siamese plenipotentiaries (among them Won ...

was signed in April 1855,

in which tariff was reduced and standardized to three percent

and the ''Phasi Pak Ruea'' or measurement duties, which was based on size of merchant ships, was abolished.

The treaty granted

extraterritoriality

In international law, extraterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdiction was usually cla ...

to the British in Siam,

who would subjected to British law instead of traditional Siamese inquisition, as Westerners sought to dissociate themselves from Siamese ''Nakhonban'' methods of

judiciary tortures and also stipulated establishment of British consulate in Bangkok. The Bowring Treaty was followed by similar agreements with other Western nations including the United States (

Harris

Harris may refer to:

Places Canada

* Harris, Ontario

* Northland Pyrite Mine (also known as Harris Mine)

* Harris, Saskatchewan

* Rural Municipality of Harris No. 316, Saskatchewan

Scotland

* Harris, Outer Hebrides (sometimes called the Isle o ...

, May 1856), France (

Montigny, August 1856), Denmark (1858), Portugal (1858), the Netherlands (1860) and Prussia (

Eulenberg

Eulenberg is a municipality in the district of Altenkirchen, in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe a ...

, 1861), all of which

Prince Wongsathirat Sanit, Mongkut's younger half-brother and Chaophraya Si Suriyawong (called Kalahom''

' in Western sources) were the main negotiators.

The Bowring Treaty had great socioeconomic impact on Siam. Siamese economy was neoliberalized, began to transform from self-subsistence to export-oriented economy

and was incorporated into world economy. The liberation of rice export, which had been previously restricted, led to rapid growth of rice plantations and productions in Central Siam as rice arose to become Siam's top export commodity.

Increased scale of production led to demands for manpower in the industry that rendered traditional corvee system obsolete. Employment took over forced labors and social changes were needed. Increased per capita income of common people and improved quality of life precipitated population boom. The Bowring Treaty of 1855 marks the beginning of 'modern' Siam in most histories.

However, these commercial concessions also took drastic effect on government revenues, which was sacrificed in the name of national security

and trade liberty. The government relied on corrupted and ineffective Chinese tax collector system to generate and levy numerous new tax programs that would compensate revenue loss. The disarray of Siamese tax system would lead to fiscal reforms in 1873.

Siam played the balance between European governments and their own colonial administrations.

King Mongkut sent a mission, led by

Phraya Montri Suriyawong (Chum Bunnag) to London in 1857 and another mission, led by Phraya Siphiphat (Phae Bunnag) to Paris in 1861. These missions were first Siamese missions to Europe after the last one in 1688 in Ayutthaya Period. The

Bunnag family

The House of Bunnag ( th, บุนนาค; ) was a powerful Siamese noble family of Mon- Persian descent influential during the late Ayutthaya kingdom and early Rattanakosin period. Originally of Persian Islamic descent, they converted en masse ...

dominated the kingdom's foreign affairs. France acquired

Cochinchina

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; vi, Đàng Trong (17th century - 18th century, Việt Nam (1802-1831), Đại Nam (1831-1862), Nam Kỳ (1862-1945); km, កូសាំងស៊ីន, Kosăngsin; french: Cochinchine; ) is a historical exony ...

in 1862 as

French Cochinchina

French Cochinchina (sometimes spelled ''Cochin-China''; french: Cochinchine française; vi, Xứ thuộc địa Nam Kỳ, Hán tự: ) was a colony of French Indochina, encompassing the whole region of Lower Cochinchina or Southern Vietnam fr ...

. The French were proven to be hostile new neighbor. King Ang Duong of Cambodia died in 1860, followed by a civil war between his two sons

Norodom

Norodom ( km, នរោត្តម, ; born Ang Voddey ( km, អង្គវតី, ); 3 February 1834 – 24 April 1904) was King of Cambodia from 19 October 1860 to his death on 24 April 1904. He was the eldest son of King Ang Duong and was ...

and

Si Votha

Si Votha ( km, ស៊ីវត្ថា; also spelled Si Vattha; c. 1841 – 31 December 1891) was a Cambodian prince who was briefly a contender for the throne. He spent his entire life fighting his half brother King Norodom for the throne.

Si ...

. Siam installed Norodom as new King of Cambodia in 1860 but the Cambodian king soon sought French assistance. French admiral

La Grandière had Norodom sign a treaty that put Cambodia under

French protection in 1863 without Siamese acknowledgement. Si Suriyawong the ''Kalahom'' responded by having Norodom sign another counter-treaty that recognized Siamese suzerainty over Cambodia and had it published in

''The Strait Times'' in 1864, much to embarrassment of the French consul Gabriel Aubaret. Cambodian issues remained unsettled as the proposals were rejected at Paris in 1865 due to prospect that France would accept Siamese rule over 'Siamese Laos' – France's future colonial ambitions. King Mongkut sent another mission to Paris led by

Phraya Surawong Waiyawat (Won Bunnag) to settle disputes. The agreement was ratified in Paris in 1867 that officially ceded Cambodia to French Indochina but with Siam retaining northwestern Cambodia including Battambang and Siemreap, which would later be ceded in 1907.

Reformer (1868–1910)

Rama IV died in 1868, and was succeeded by his 15-year-old son Chulalongkorn, who reigned as

Rama V

Chulalongkorn ( th, จุฬาลงกรณ์, 20 September 1853 – 23 October 1910) was the fifth monarch of Siam under the House of Chakri, titled Rama V. He was known to the Siamese of his time as ''Phra Phuttha Chao Luang'' (พร� ...

and is now known as Rama the Great. Rama V was the first Siamese king to have a full Western education, having been taught by a British governess,

Anna Leonowens

Anna Harriette Leonowens (born Ann Hariett Emma Edwards; 5 November 1831 – 19 January 1915) was an Anglo-Indian or Indian-born British travel writer, educator, and social activist.

She became well known with the publication of her memoirs, be ...

– whose place in Siamese history has been fictionalized as ''

The King and I

''The King and I'' is the fifth musical by the team of Rodgers and Hammerstein. It is based on Margaret Landon's novel '' Anna and the King of Siam'' (1944), which is in turn derived from the memoirs of Anna Leonowens, governess to the childre ...

''. At first Rama V's reign was dominated by the conservative regent, Chaophraya

Si Suriyawongse

Somdet Chaophraya Borom Maha Sri Suriwongse ( th, สมเด็จเจ้าพระยาบรมมหาศรีสุริยวงศ์, , ; also spelled ''Suriyawong'', etc.; 23 December 1808 – 19 January 1883), whose personal ...

, but when the king came of age in 1873 he soon took control. He created a Privy Council and a Council of State, a formal court system and budget office. He announced that slavery would be gradually abolished and debt-bondage restricted.

At first the princes and conservatives successfully resisted the king's reform agenda, but as the older generation was replaced by younger, Western-educated princes, resistance faded. He found powerful allies in his brothers Prince

Chakkraphat, whom he made finance minister, Prince

Damrong

Prince Tisavarakumarn, the Prince Damrong Rajanubhab (Thai: ; Full transcription is "Somdet Phrachao Borommawongthoe Phra-ongchao Ditsawarakuman Kromphraya Damrongrachanuphap" (สมเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธ� ...

, who organized interior government and education, and his brother-in-law Prince

Devrawongse, foreign minister for 38 years. In 1887 Devrawonge visited Europe to study governmental systems. On his recommendation the king established cabinet government, an audit office, and an education department. The semi-autonomous status of Chiang Mai was ended and the army was reorganized and modernized.

In 1893 French authorities in Indochina used a minor border dispute to provoke a crisis. French gunboats appeared at Bangkok and demanded the cession of Lao territories east of the

Mekong

The Mekong or Mekong River is a trans-boundary river in East Asia and Southeast Asia. It is the world's List of rivers by length, twelfth longest river and List of longest rivers of Asia, the third longest in Asia. Its estimated length is , ...

. The king appealed to the British, but the British minister told the king to settle on whatever terms he could get. The king had no choice but to comply. Britain's only gesture was an agreement with France guaranteeing the integrity of the rest of Siam. In exchange, Siam had to give up its claim to the Tai-speaking Shan region of northeastern Burma to the British.

The French, however, continued to pressure Siam, and in 1906–1907 they manufactured another crisis. This time Siam had to concede French control of territory on the west bank of the Mekong opposite Luang Prabang and around

Champasak in southern Laos, as well as western Cambodia. The British interceded to prevent more French pressure on Siam, but their price, in 1909 was the acceptance of British sovereignty over of

Kedah

Kedah (), also known by its honorific Darul Aman (Islam), Aman and historically as Queda, is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia, located in the northwestern part of Peninsular Malaysia. The state covers a total area ...

,

Kelantan

Kelantan (; Jawi: ; Kelantanese Malay: ''Klate'') is a state in Malaysia. The capital is Kota Bharu and royal seat is Kubang Kerian. The honorific name of the state is ''Darul Naim'' (Jawi: ; "The Blissful Abode").

Kelantan is located in the ...

,

Perlis

Perlis, ( Northern Malay: ''Peghelih''), also known by its honorific title Perlis Indera Kayangan, is the smallest state in Malaysia by area and population. Located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, it borders the Thai provinces o ...

, and

Terengganu

Terengganu (; Terengganu Malay: ''Tranung'', Jawi: ), formerly spelled Trengganu or Tringganu, is a sultanate and constitutive state of federal Malaysia. The state is also known by its Arabic honorific, ''Dāru l- Īmān'' ("Abode of Faith"). ...

under

Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. All of these "lost territories" were on the fringes of the Siamese sphere of influence and had never been securely under their control, but being compelled to abandon all claim to them was a substantial humiliation to both king and country. Historian

David K. Wyatt

David K. Wyatt (September 21, 1937 – November 14, 2006) was an American historian and author who studied Thailand. He taught at Cornell University from 1969 to 2002, and also served as Chair of the Cornell University Department of History and ...

describes Chulalongkorn as "broken in spirit and health" following the 1893 crisis. It became the basis for the country's name change: with the loss of these territories ''Great Siam'' was no more; the king now ruled only the core "Thai lands".

Meanwhile, reform continued unabated, transforming an absolute monarchy based on traditional relationships of power into a modern, centralized nation state. The process was increasingly under the control of Rama V's European-educated sons. Railways and telegraph lines united previously remote and semi-autonomous provinces. The currency was tied to the

gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

and a modern system of taxation replaced the arbitrary levies and corvee labor of the past. The biggest problem was the shortage of trained civil servants, and many foreigners had to be employed until new schools could be built and Siamese graduates produced. By 1910, when the king died, Siam had become a semi-modern country and continued to escape colonial rule.

Modern Siam (1905–1932)

From kingdom to modern nation (1910–1925)

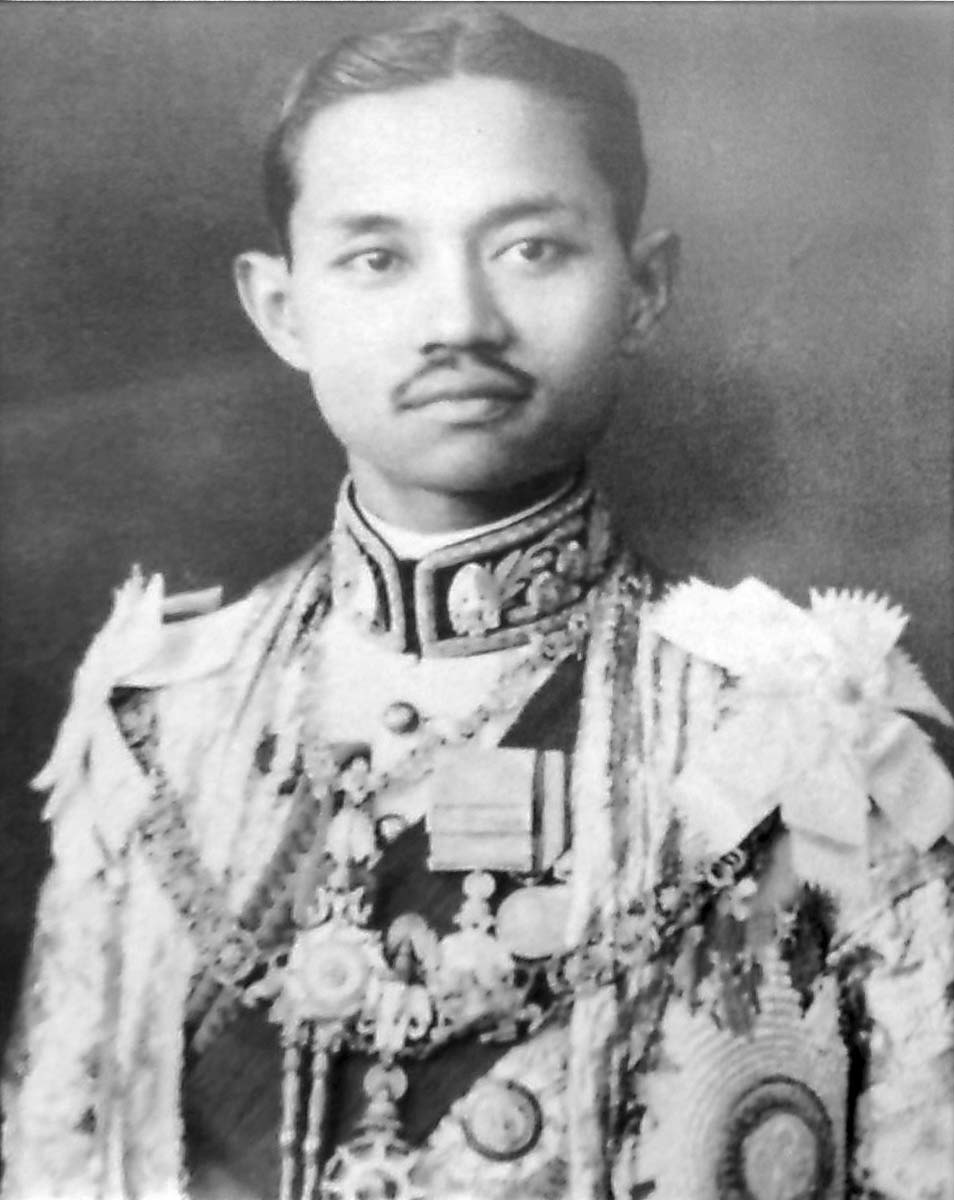

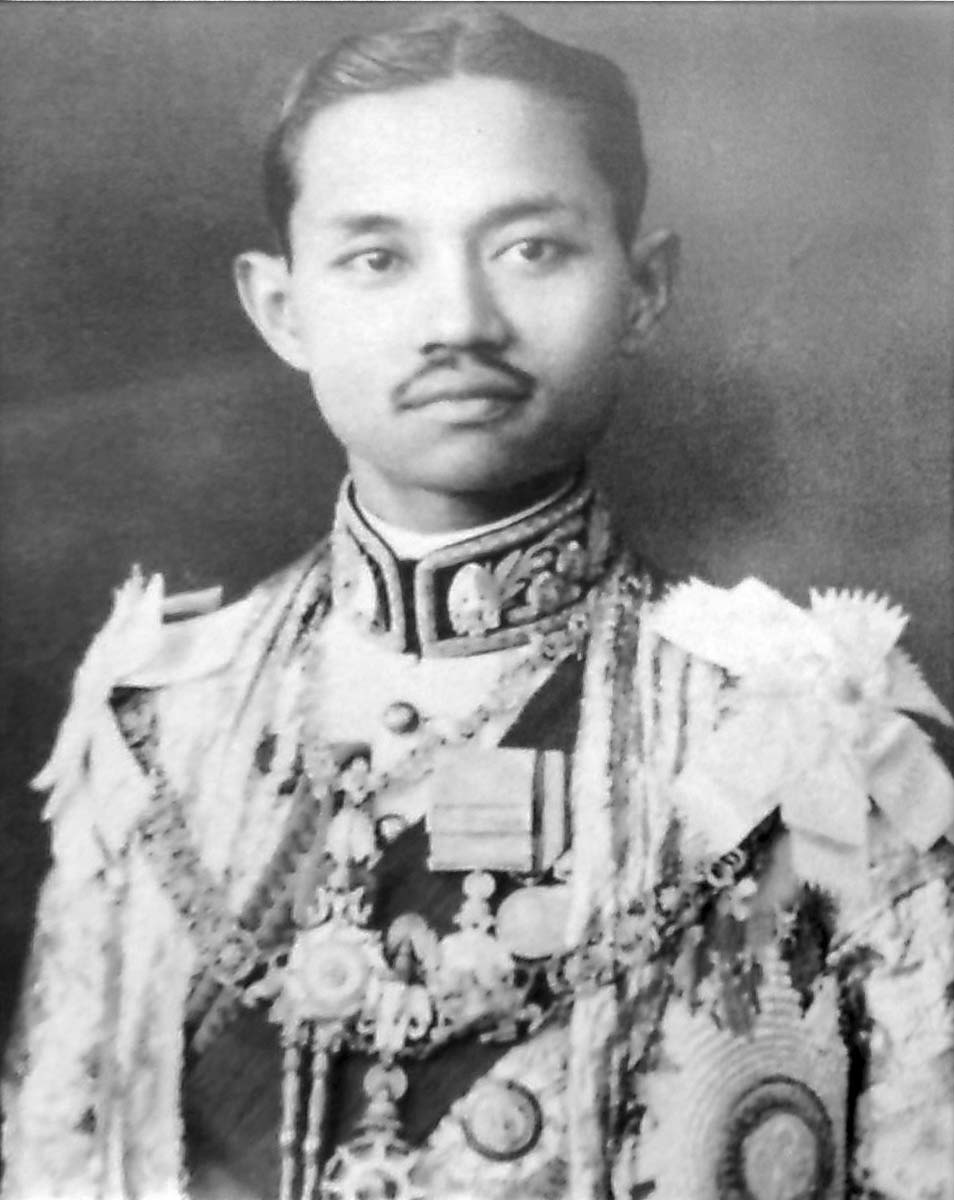

One of Rama V's reforms was to introduce a Western-style law of royal succession, so in 1910 he was peacefully succeeded by his son

Vajiravudh

Vajiravudh ( th, วชิราวุธ, , 1 January 188126 November 1925) was the sixth monarch of Siam under the Chakri dynasty as Rama VI. He ruled from 23 October 1910 until his death in 1925. King Vajiravudh is best known for his efforts ...

, who reigned as

Rama VI

Vajiravudh ( th, วชิราวุธ, , 1 January 188126 November 1925) was the sixth monarch of Siam under the Chakri dynasty as Rama VI. He ruled from 23 October 1910 until his death in 1925. King Vajiravudh is best known for his efforts ...

. He had been educated at

Sandhurst military academy and at

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, and was an anglicized Edwardian gentleman. Indeed, one of Siam's problems was the widening gap between the Westernized royal family and upper aristocracy and the rest of the country. It took another 20 years for Western education to permeate the bureaucracy and the army.

There had been some political reform under Rama V, but the king was still an

absolute monarch

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism (European history), Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute pow ...

, who acted as the head of the cabinet and staffed all the agencies of the state with his own relatives. Vajiravudh knew that the rest of the "new" nation could not be excluded from government forever, but he had no faith in Western-style democracy. He applied his observations of the success of the British monarchy ruling India, appearing more in public and instituting more royal ceremonies. However, Rama VI also carried on his father's modernization plan.

Bangkok became more and more the capital of the new nation of Siam. Rama VI's government began several nationwide development projects, despite financial hardship. New roads, bridges,

railways

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

,

hospitals

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emerge ...

and schools mushroomed throughout the country with funds from Bangkok. Newly created "viceroys" were appointed to the newly restructured "regions", or ''

monthon

''Monthon'' ( th, มณฑล) were administrative subdivisions of Thailand at the beginning of the 20th century. The Thai word ''monthon'' is a translation of the word ''mandala'' (', literally "circle"), in its sense of a type of political for ...

'' (circles), as king's agents supervising administrative affairs in the provinces.

The king established the ''Wild Tiger Corps'', or ''Kong Suea Pa'' (), a

paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

organization of Siamese of "good character" united to further the nation's cause. He also created a junior branch which continues today as the

National Scout Organization of Thailand. The king spent much time on the development of the movements as he saw it as an opportunity to create a bond between himself and loyal citizens. It was also a way to single out and honor his favourites. At first the Wild Tigers were drawn from the king's personal entourage, but an enthusiasm among the population arose later. Of the adult movement, a German observer wrote in September 1911: "This is a troop of volunteers in black uniform, drilled in a more or less military fashion, but without weapons. The British

Scouts

Scouting, also known as the Scout Movement, is a worldwide youth movement employing the Scout method, a program of informal education with an emphasis on practical outdoor activities, including camping, woodcraft, aquatics, hiking, backpacking ...

are apparently the paradigm for the Tiger Corps. In the whole country, at the most far-away places, units of this corps are being set up. One would hardly recognize the quiet and phlegmatic Siamese." The paramilitary movement largely disappeared by 1927, but was revived and evolved into the

Volunteer Defense Corps

The Border Patrol Police ( th, ตำรวจตระเวนชายแดน); (BPP) is a Thai paramilitary police under the jurisdiction of the Royal Thai Police, responsible for border security and counterinsurgency.

History

The Thai Bo ...

, also called the Village Scouts. ()

Vajiravudh's style of government differed from that of his father. In the beginning, the king continued to use his father's team and there was no sudden break in the daily routine of government. Much of the running of daily affairs was therefore in the hands of experienced and competent men. To them and their staff Siam owed many progressive steps, such as the development of a national plan for the education of the whole populace, the setting up of clinics where free vaccination was given against smallpox, and the continuing expansion of railways. However, senior posts were gradually filled with members of the king's coterie when a vacancy occurred through death, retirement, or resignation. By 1915, half the cabinet consisted of new faces. Most notable was Chao Phraya Yomarat's presence and Prince Damrong's absence. He resigned from his post as Minister of the Interior officially because of ill health, but in actuality because of friction between himself and the king.

World War I

In 1917 Siam declared war on

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, mainly to be favor with the British and the French. Siam's taken participation in World War I secured it a seat at the

Versailles Peace Conference

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

, and Foreign Minister

Devawongse

Devan Udayawongse, the Prince Devawongse Varoprakar ( th, สมเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ พระองค์เจ้าเทวัญอุไทยวงศ์ กรมพระยาเทวะวง ...

used this opportunity to argue for the repeal of 19th century treaties and the restoration of full Siamese sovereignty. The United States obliged in 1920, while France and Britain delayed until 1925. This victory gained the king some popularity, but it was soon undercut by discontent over other issues, such as his extravagance, which became more noticeable when a sharp postwar recession hit Siam in 1919. There was also concern that the king had no son, which undermined the stability of the monarchy due to the absence of heirs. Thus when Rama VI died suddenly in 1925, aged only 44, the monarchy was in a weakened state. He was succeeded by his younger brother

Prajadhipok

Prajadhipok ( th, ประชาธิปก, RTGS: ''Prachathipok'', 8 November 1893 – 30 May 1941), also Rama VII, was the seventh monarch of Siam of the Chakri dynasty. His reign was a turbulent time for Siam due to political and ...

.

Transition to 1932 revolution

Unlike other states of

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

,

Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

was never formally colonised by colonial powers, although significant territory had been ceded under duress to Britain and France. Conventional perspectives attribute this to the efforts made by the monarchs of the

Chakri Dynasty

The Chakri dynasty ( th, ราชวงศ์ จักรี, , , ) is the current reigning dynasty of the Kingdom of Thailand, the head of the house is the king, who is head of state. The family has ruled Thailand since the founding of the ...

, particularly

Rama IV

Mongkut ( th, มงกุฏ; 18 October 18041 October 1868) was the fourth monarch of Siam (Thailand) under the House of Chakri, titled Rama IV. He ruled from 1851 to 1868. His full title in Thai was ''Phra Bat Somdet Phra Menthora Ramathibod ...

and

Rama V

Chulalongkorn ( th, จุฬาลงกรณ์, 20 September 1853 – 23 October 1910) was the fifth monarch of Siam under the House of Chakri, titled Rama V. He was known to the Siamese of his time as ''Phra Phuttha Chao Luang'' (พร� ...

, to "modernise" the Siamese polity, and also to the relative cultural and ethnic homogeneity of the Thai nation. Rama IV (King

Mongkut

Mongkut ( th, มงกุฏ; 18 October 18041 October 1868) was the fourth monarch of Siam (Thailand) under the House of Chakri, titled Rama IV. He ruled from 1851 to 1868. His full title in Thai was ''Phra Bat Somdet Phra Menthora Ramathibod ...

) opened

Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 mi ...

to European trade and began the process of modernisation. His son, Rama V (King

Chulalongkorn

Chulalongkorn ( th, จุฬาลงกรณ์, 20 September 1853 – 23 October 1910) was the fifth monarch of Siam under the House of Chakri, titled Rama V. He was known to the Siamese of his time as ''Phra Phuttha Chao Luang'' (พร� ...

), consolidated control over Thai vassal states, creating an

absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

and a centralised state. The success of the Chakri monarchs would sow the seeds of the 1932 revolution and the end of the absolute monarchy. "Modernisation" mandated from above had, by the early 20th century, created a class of Western-educated Thais in the commoner and lower nobility classes, who staffed the middle and lower ranks of the nascent Siamese bureaucracy. They were influenced by the ideals of the

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and

Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

s.

This new faction would eventually form the

People's Party, the nucleus of the

1932 revolution.

Recent scholarship offers alternative perspectives that challenge conventional views of the creation of the nation.

Thongchai Winichakul

Thongchai Winichakul ( th, ธงชัย วินิจจะกูล; , ; born 1957), is a Thai historian and researcher of Southeast Asian studies. He is professor emeritus of Southeast Asian history at the University of Wisconsin–Madison ...

's hypothesis on the emergence of the "geo-body" of Siam is widely accepted by scholars in Thai and Southeast Asian studies. Thongchai argues that the traditional Hindu-Buddhist paradigms of culture, space, governance, and power were challenged by a significantly different civilisation, arising mainly from Latin Christianity tempered by the

humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

of the

Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

. The East became increasingly described as "barbaric", "ignorant", or "inferior". The mission to "civilise" the "barbaric Asiatics" became the ''raison d'être'' for colonialism and imperialism. The ''siwilai'' ('civilise') programme in 19th century Siam was part of a strategy the Chakri monarchy adopted to justify their country's continued existence as a legitimate independent state to fend off colonial intervention. Other components involved the spatial and political reorganisation of the Siamese polity along Western lines to strengthen the state and gain recognition from the Western powers. Thongchai argues that the tactics adopted by the Siamese state were similar to those adopted by Western colonial powers in administering their colonies. Space and power were essentially redefined by the Siamese state. Autonomous and semi-autonomous

mueang

Mueang ( th, เมือง ''mɯ̄ang'', ), Muang ( lo, ເມືອງ ''mɯ́ang'', ; Tai Nuea: ᥛᥫᥒᥰ ''muang''), Mong ( shn, ''mə́ŋ'', ), Meng () or Mường (Vietnamese), were pre-modern semi-independent city-states or principali ...

s were brought under the direct control of the state by the beginning of the 20th century. Cartography was employed to define national borders, replacing the vague frontiers of the

Mandala kingdoms. People were assigned to ethnic groups. To promote the new Western-inspired definitions of ''siwilai'', the educated Siamese of the 19th century, mainly the aristocracy, began writing ethnographies and creating their own versions of the "other" to strengthen the identity of the Siamese nation by emphasising its superiority, in contrast to the barbarity of upland tribal peoples such as the

Lue Lue or LUE may refer to:

People

* Andrew Lue (born 1992), Canadian retired football player

* Cachet Lue (born 1997), Canadian-born Jamaican footballer

* Lue Gim Gong (1860–1925), Chinese-American horticulturalist

* Lee Lue (1935–1969), Laotian ...

and the

Lahu.

These new perspectives created a politically dominant Siamese aristocracy that became increasingly powerful from the "modernisation/self-colonisation" process it initiated and directed. This seems to contradict conventional perspectives, which are based on the assumption that the Chakri absolute monarchy by the early 1930s was a relatively passive actor, due to the political weakness of Rama VI (King

Vajiravudh

Vajiravudh ( th, วชิราวุธ, , 1 January 188126 November 1925) was the sixth monarch of Siam under the Chakri dynasty as Rama VI. He ruled from 23 October 1910 until his death in 1925. King Vajiravudh is best known for his efforts ...

) and Rama VII (King

Prajadhipok

Prajadhipok ( th, ประชาธิปก, RTGS: ''Prachathipok'', 8 November 1893 – 30 May 1941), also Rama VII, was the seventh monarch of Siam of the Chakri dynasty. His reign was a turbulent time for Siam due to political and ...

) and crises such as the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. No longer in control of events and political developments in Siam, they were swept aside by adherents of democracy and nationalism. Revisionists counter by noting that the weaknesses of an individual monarch do not necessarily mean that the resolve and power of the traditional landed aristocracy or the so-called ''

Sakdina ''Sakdina'' ( th, ศักดินา) was a system of social hierarchy in use from the Ayutthaya to early Rattanakosin periods of Thai history. It assigned a numerical rank to each person depending on their status, and served to determine their ...

'' aristocracy in maintaining its preeminence through upholding the political prerogatives of the absolute monarchy was in any way lessened. In their view, attributing the outbreak of the

1932 revolution largely to the beliefs and ambitions of the Western-educated promoters of the People's Party obscures the role played by the Siamese monarchy and aristocracy.

The end of absolute rule (1925–1932)

Unprepared for his new responsibilities, all Prajadhipok had in his favor was a lively intelligence, a charming diplomacy in his dealings with others, modesty and industrious willingness to learn, and the somewhat tarnished, but still potent, allure of the crown.

Unlike his predecessor, the king diligently read virtually all state papers that came his way, from ministerial submissions to petitions by citizens. Within half a year, only three of Vajiravudh's twelve ministers stayed put, the rest having been replaced by members of the royal family. On the one hand, these appointments brought back men of talent and experience; on the other, it signaled a return to royal oligarchy. The king obviously wanted to demonstrate a clear break with the discredited sixth reign, and the choice of men to fill the top positions appeared to be guided largely by a wish to restore a Chulalongkorn-type government.

The legacy that Prajadhipok received from his elder brother were problems of the sort that had become chronic in the Sixth Reign. The most urgent of these was the economy: the finances of the state were in chaos, the budget heavily in deficit, and the royal accounts a nightmare of debts and questionable transactions. That the rest of the world was deep in the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

following World War I did not help the situation either.

Virtually the first act of Prajadipok as king entailed an institutional innovation intended to restore confidence in the monarchy and government, the creation of the

Supreme Council of the State. This privy council was made up of a number of experienced and extremely competent members of the royal family, including the longtime Minister of the Interior (and Chulalongkorn's right-hand man) Prince Damrong. Gradually these princes arrogated increasing power by monopolizing all the main ministerial positions. Many of them felt it their duty to make amends for the mistakes of the previous reign, but it was not generally appreciated.

With the help of this council, the king managed to restore stability to the economy, although at a price of making a significant number of the civil servants redundant and cutting the salary of those that remained. This was obviously unpopular among the officials, and was one of the trigger events for the coup of 1932. Prajadhipok then turned his attention to the question of future politics in Siam. Inspired by the British example, the king wanted to allow the common people to have a say in the country's affairs by the creation of a parliament. A proposed constitution was ordered to be drafted, but the king's wishes were rejected by his advisers, who felt that the population was not yet ready for democracy.

Revolution

In 1932, with the country deep in depression, the Supreme Council opted to introduce cuts in spending, including the military budget. The king foresaw that these policies might create discontent, especially in the army, and he therefore convened a special meeting of officials to explain why the cuts were necessary. In his address he stated the following, "I myself know nothing at all about finances, and all I can do is listen to the opinions of others and choose the best... If I have made a mistake, I really deserve to be excused by the people of Siam."

No previous monarch of Siam had ever spoken in such terms. Many interpreted the speech not as Prajadhipok apparently intended, namely as a frank appeal for understanding and cooperation. They saw it as a sign of his weakness and evidence that a system which perpetuated the rule of fallible autocrats should be abolished. Serious political disturbances were threatened in the capital, and in April the king agreed to introduce a constitution under which he would share power with a prime minister. This was not enough for the radical elements in the army, however. On 24 June 1932, while the king was at the seaside, the Bangkok garrison mutinied and seized power, led by a group of 49 officers known as "

Khana Ratsadon

The People's Party, known in Thai as Khana Ratsadon ( th, คณะราษฎร, ), was a Siamese group of military and civil officers, and later a political party, which staged a bloodless revolution against King Prajadhipok's government a ...

". Thus ended 800 years of

absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

.

Thai political history was little researched by Western Southeast Asian scholars in the 1950s and 1960s. Thailand, as the only nominally "native" Southeast Asian polity to escape colonial conquest, was deemed to be relatively more stable as compared with other newly independent states in Southeast Asia.

It was perceived to have retained enough continuity from its "traditions", such as the institution of the monarchy, to have escaped from the chaos and troubles caused by

decolonisation

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

and to resist the encroachment of revolutionary communism.