The Portuguese Colonial War ( pt, Guerra Colonial Portuguesa), also known in Portugal as the Overseas War () or in the

former colonies as the War of Liberation (), and also known as the Angolan, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambican War of Independence, was a 13-year-long conflict fought between

Portugal's military and the emerging

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

movements in Portugal's African colonies between 1961 and 1974. The Portuguese ultraconservative regime at the time, the , was overthrown by a military

coup in 1974, and the change in government brought the conflict to an end. The war was a decisive

ideological

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied prim ...

struggle in

Lusophone

Lusophones ( pt, Lusófonos) are peoples that speak Portuguese as a native or as common second language and nations where Portuguese features prominently in society. Comprising an estimated 270 million people spread across 10 sovereign countries ...

Africa, surrounding nations, and mainland Portugal.

The prevalent Portuguese and international historical approach considers the Portuguese Colonial War as was perceived at the time—a single conflict fought in the three separate

Angolan,

Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau ( ; pt, Guiné-Bissau; ff, italic=no, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫 𞤄𞤭𞤧𞤢𞥄𞤱𞤮, Gine-Bisaawo, script=Adlm; Mandinka: ''Gine-Bisawo''), officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau ( pt, República da Guiné-Bissau, links=no ) ...

and

Mozambican theaters of operations, rather than a number of separate conflicts as the emergent African countries aided each other and were supported by the same global powers and even the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

during the war. The

1954 Indian Annexation of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and

1961 Indian Annexation of Goa

The Annexation of Goa was the process in which the Republic of India annexed ', the then Portuguese Indian territories of Goa, Daman and Diu, starting with the armed action carried out by the Indian Armed Forces in December 1961. In India ...

are sometimes included as part of the conflict.

Unlike other European nations during the 1950s and 1960s, the Portuguese regime did not withdraw from its African colonies, or the overseas provinces () as those territories had been officially called since 1951. During the 1960s, various armed independence movements became active—the

People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, Abbreviation, abbr. MPLA), for some years called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan left-wi ...

,

National Liberation Front of Angola

The National Front for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola; abbreviated FNLA) is a political party and former militant organisation that fought for Angolan independence from Portugal in the war of independe ...

,

National Union for the Total Independence of Angola in Angola,

African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde

The African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde ( pt, Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, PAIGC) is a political party in Guinea-Bissau. Originally formed to peacefully campaign for independence from ...

in Portuguese Guinea, and the

Mozambique Liberation Front in Mozambique. During the ensuing conflict, atrocities were committed by all forces involved.

Throughout the period, Portugal faced increasing dissent, arms embargoes, and other punitive sanctions imposed by the international community, including by some

Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Free Bloc, the Capitalist Bloc, the American Bloc, and the NATO Bloc, was a coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War of 1947–1991. It was spearheaded by ...

governments, either intermittently or continuously. The independentist guerrillas and movements of Portuguese Africa were heavily supported and instigated with money, weapons, training and diplomatic lobbying by the

Communist Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

which had the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

as its lead nation. By 1973, the war had become increasingly unpopular due to its length and financial costs, the worsening of diplomatic relations with other United Nations members, and the role it had always played as a factor of perpetuation of the entrenched Estado Novo regime and the nondemocratic

status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, political, religious or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the current state of social structure and/or values. ...

in Portugal.

The end of the war came with the

Carnation Revolution

The Carnation Revolution ( pt, Revolução dos Cravos), also known as the 25 April ( pt, 25 de Abril, links=no), was a military coup by left-leaning military officers that overthrew the authoritarian Estado Novo regime on 25 April 1974 in Lisbo ...

military coup of April 1974 in

mainland Portugal

Continental Portugal ( pt, Portugal continental, ) or mainland Portugal comprises the bulk of the Portuguese Republic, namely that part on the Iberian Peninsula and so in Continental Europe, having approximately 95% of the total population and 9 ...

. The withdrawal resulted in the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Portuguese citizens plus military personnel of European, African, and mixed ethnicity from the former Portuguese territories and newly independent African nations. This migration is regarded as one of the largest peaceful, if forced,

migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

s in the world's history although most of the migrants fled the former Portuguese territories as destitute refugees.

The former colonies faced severe problems after independence. Devastating

civil wars

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

followed in

Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

and

Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

, which lasted several decades, claimed millions of lives, and resulted in large numbers of displaced

refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution. s.

[Stuart A. Notholt (Apr., 1998) Review: ‘The Decolonization of Portuguese Africa: Metropolitan Revolution and the Dissolution of Empire by Norrie MacQueen – Mozambique since Independence: Confronting Leviathan by Margaret Hall, Tom Young’ ''African Affairs'', Vol. 97, No. 387, pp. 276–78, ] Angola and Mozambique established

state-planned economies after independence,

[Susan Rose-Ackerman, 2009, "Corruption in the Wake of Domestic National Conflict" in ''Corruption, Global Security, and World Order'' (ed. Robert I. Rotberg: Brookings Institution), p. 79.] and struggled with inefficient judicial systems and bureaucracies,

[ corruption,][Mario de Queiroz]

Africa–Portugal: Three Decades After Last Colonial Empire Came to an End

Inter Press Service (November 23, 2005). poverty and unemployment.[ A level of ]social order

The term social order can be used in two senses: In the first sense, it refers to a particular system of social structures and institutions. Examples are the ancient, the feudal, and the capitalist social order. In the second sense, social order ...

and economic development

In the economics study of the public sector, economic and social development is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and ...

comparable to what had existed under Portuguese rule, including during the period of the Colonial War, became the goal of the independent territories.["Things are going well in Angola. They achieved good progress in their first year of independence. There's been a lot of building and they are developing health facilities. In 1976, they produced 80,000 tons of coffee. Transportation means are also being developed. Currently, between 200,000 and 400,000 tons of coffee are still in warehouses. In our talks with ngolan President AgostinhoNeto we stressed the absolute necessity of achieving a level of economic development comparable to what had existed under ortuguesecolonialism."; "There is also evidence of black racism in Angola. Some are using the hatred against the colonial masters for negative purposes. There are many mulattos and whites in Angola. Unfortunately, racist feelings are spreading very quickly." Castro']

1977 southern Africa tour: A report

to Honecker

Erich Ernst Paul Honecker (; 25 August 1912 – 29 May 1994) was a German communist politician who led the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from 1971 until shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. He held the posts ...

, CNN

The former Portuguese territories in Africa became sovereign states, with Agostinho Neto

António Agostinho da Silva Neto (17 September 1922 – 10 September 1979) was an Angolan politician and poet. He served as the first president of Angola from 1975 to 1979, having led the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) i ...

in Angola, Samora Machel

Samora Moisés Machel (29 September 1933 – 19 October 1986) was a Mozambican military commander and political leader. A socialist in the tradition of Marxism–Leninism, he served as the first President of Mozambique from the country's ...

in Mozambique, Luís Cabral

Luís Severino de Almeida Cabral (11 April 1931 – 30 May 2009) was a Bissau-Guinean politician who was the first President of Guinea-Bissau. He served from 1974 to 1980, when a military '' coup d'état'' led by João Bernardo Vieira deposed h ...

in Guinea-Bissau, Manuel Pinto da Costa

Manuel Pinto da Costa (born 5 August 1937) is a Santomean economist and politician who served as the first president of São Tomé and Príncipe from 1975 to 1991. He again served as president from 2011 to 2016.

Life and career

Educated in Ea ...

in São Tomé and Príncipe, and Aristides Pereira

Aristides Maria Pereira (; 17 November 1923 – 22 September 2011) was a Cape Verdean politician. He was the first President of Cape Verde, serving from 1975 to 1991.

Biography

Pereira was born in Fundo das Figueiras, on the island of Boa V ...

in Cape Verde as the heads of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

.

Political context

15th century

When the Portuguese began trading on the west coast of Africa in the 15th century, they concentrated their energies on Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

and Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

. Hoping at first for gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

, they soon found that slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

s were the most valuable commodity available in the region for export. The Islamic Empire was already well-established in the African slave trade

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were common in parts of Africa in ancient times, as they were in much of the rest of the ancient world. When the trans-Saharan slave trade, Indian Ocean ...

, for centuries linking it to the Arab slave trade

History of slavery in the Muslim world refers to various periods in which a slave trade has been carried out under the auspices of Arab peoples or Arab countries. Examples include:

* Trans-Saharan slave trade

* Indian Ocean slave trade

* Barbary s ...

. However, the Portuguese who had conquered the Islamic port of Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territori ...

in 1415 and several other towns in current-day Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

in a Crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

against Islamic neighbors, managed to successfully establish themselves in the area. The Portuguese, though, never established much more than a foothold in either place.

In Guinea, rival European powers had established control over the trade routes in the region, while local African rulers confined the Portuguese to the coast. These rulers then sent enslaved Africans to the Portuguese ports, or to forts in Africa from where they were exported. Thousands of kilometers down the coast, in Angola, the Portuguese found consolidating their early advantage in establishing hegemony over the region even harder, due to the encroachment of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

traders. Nevertheless, the fortified Portuguese towns of Luanda

Luanda () is the capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major industrial, cultural and urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atlantic coast, Luanda is Angola's administrative centre, its chief seapo ...

(established in 1587 with 400 Portuguese settlers) and Benguela

Benguela (; Umbundu: Luombaka) is a city in western Angola, capital of Benguela Province. Benguela is one of Angola's most populous cities with a population of 555,124 in the city and 561,775 in the municipality, at the 2014 census.

History

P ...

(a fort from 1587, a town from 1617) remained almost continuously in Portuguese hands.

As in Guinea, the slave trade became the basis of the local economy in Angola. Excursions traveled ever farther inland to procure captives who were sold by African rulers; the primary source of these slaves were those captured as a result of losing a war or interethnic skirmish with other African tribes. More than a million men, women, and children were shipped from Angola across the Atlantic. In this region, unlike Guinea, the trade remained largely in Portuguese hands. Nearly all the slaves were destined for the Portuguese colony of Brazil.

In Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

, reached in the 15th century by Portuguese sailors searching for a maritime spice trade route, the Portuguese settled along the coast and made their way into the hinterland as '' sertanejos'' (backwoodsmen). These ''sertanejos'' lived alongside Swahili traders and even obtained employment among Shona kings as interpreters and political advisers. One such ''sertanejo'' managed to travel through almost all the Shona kingdoms, including the Mutapa Empire

The Kingdom of Mutapa – sometimes referred to as the Mutapa Empire, Mwenemutapa, ( sn, Mwene we Mutapa, pt, Monomotapa) – was an African kingdom in Zimbabwe, which expanded to what is now modern-day Mozambique.

The Portuguese term ''Mon ...

's (Mwenemutapa) metropolitan district, between 1512 and 1516.

By the 1530s, small bands of Portuguese traders and prospectors penetrated the interior regions seeking gold, where they set up garrisons and trading posts at Sena

Sena may refer to:

Places

* Sanandaj or Sena, city in northwestern Iran

* Sena (state constituency), represented in the Perlis State Legislative Assembly

* Sena, Dashtestan, village in Bushehr Province, Iran

* Sena, Huesca, municipality in Hue ...

and Tete

Tete is the capital city of Tete Province in Mozambique. It is located on the Zambezi River, and is the site of two of the four bridges crossing the river in Mozambique. A Swahili trade center before the Portuguese colonial era, Tete continue ...

on the Zambezi River

The Zambezi River (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than hal ...

and tried to establish a monopoly over the gold trade. The Portuguese finally entered into direct relations with the Mwenemutapa in the 1560s. However, the Portuguese traders and explorers settled in the coastal strip with greater success, and established strongholds safe from their main rivals in East Africa – the Omani Arabs

Omanis ( ar, الشعب العماني) are the nationals of Sultanate of Oman, located in the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula. Omanis have inhabited the territory that is now Oman. In the eighteenth century, an alliance of traders ...

, including those of Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

.

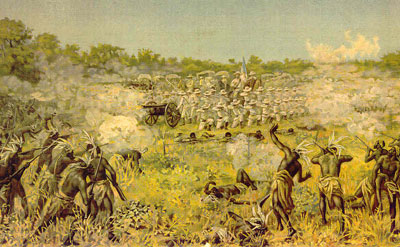

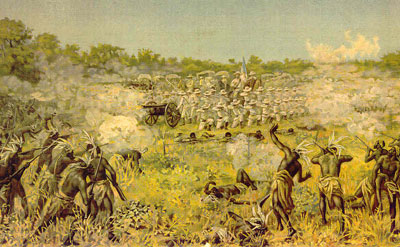

Scramble for Africa and the World Wars

Portugal's colonial claim to the region was recognized by the other European powers during the 1880s, during the

Portugal's colonial claim to the region was recognized by the other European powers during the 1880s, during the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during a short period known as New Imperialism ...

, and the final boundaries of Portuguese Africa were agreed by negotiation in Europe in 1891. At the time, Portugal was in effective control of little more than the coastal strip of both Angola and Mozambique, but important inroads into the interior had been made since the first half of the 19th century. In Angola, construction of a railway from Luanda

Luanda () is the capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major industrial, cultural and urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atlantic coast, Luanda is Angola's administrative centre, its chief seapo ...

to Malanje, in the fertile highlands, was started in 1885.

Work began in 1903 on a commercially significant line from Benguela all the way inland to the Katanga region, aiming to provide access to the sea for the richest mining district of the Belgian Congo.World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

in 1914, Portugal sent reinforcements to both colonies, because the fighting in the neighboring German African colonies was expected to spill over the borders into its territories.

After Germany declared war on Portugal in March 1916, the Portuguese government sent more reinforcements to Mozambique (the South Africans had captured German South West Africa in 1915). These troops supported British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

, South African and Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

military operations against German colonial forces in German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; german: Deutsch-Ostafrika) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mo ...

. In December 1917, German colonial forces led by Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck

Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck (20 March 1870 – 9 March 1964), also called the Lion of Africa (german: Löwe von Afrika), was a general in the Imperial German Army and the commander of its forces in the German East Africa campaign. For four ye ...

invaded Mozambique from German East Africa. Portuguese, British and Belgian forces spent all of 1918 chasing Lettow-Vorbeck and his men across Mozambique, German East Africa and Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesi ...

. Portugal sent a total of 40,000 reinforcements to Angola and Mozambique during World War I.

By this time, the regime in Portugal had been through two major political upheavals—from monarchy to republic in 1910 and then to a military dictatorship after a coup in 1926. These changes resulted in a tightening of Portuguese control in Angola. In the early years of the expanded colony, near-constant warfare as occurring between the Portuguese and the various African rulers of the region. A systematic campaign of conquest and pacification was undertaken by the Portuguese. One by one, the local kingdoms were overwhelmed and abolished.

By the middle of the 1920s, the whole of Angola was under control. Slavery had officially ended in Portuguese Africa, but the plantations were worked on a system of paid serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

dom by African labour composed of the large majority of ethnic Africans who did not have resources to pay Portuguese taxes and were considered unemployed by the authorities. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and the first decolonization events, this system gradually declined, but paid forced labor, including labor contracts with forced relocation of people, continued in many regions of Portuguese Africa until it was finally abolished in 1961.

Post-World War II

In the late 1950s, the Portuguese Armed Forces

The Portuguese Armed Forces ( pt, Forças Armadas) are the military of Portugal. They include the General Staff of the Armed Forces, the other unified bodies and the three service branches: Portuguese Navy, Portuguese Army and Portuguese Air ...

saw themselves confronted with the paradox generated by the dictatorial regime of the '' Estado Novo'' that had been in power since 1933; on one hand, the policy of Portuguese neutrality in World War II placed the Portuguese Armed Forces out of the way of a possible East-West conflict; on the other, the regime felt the increased responsibility of keeping Portugal's vast overseas territories under control and protecting the citizenry there. Portugal joined NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

as a founding member in 1949, and was integrated within the various fledgling military commands of NATO.

NATO's focus on preventing a conventional Soviet attack against Western Europe was to the detriment of military preparations against guerrilla uprisings in Portugal's overseas provinces that were considered essential for the survival of the nation. The integration of Portugal in NATO resulted in the formation of a military élite who were critical in the planning and implementation of operations during the Overseas War. This "NATO generation" ascended quickly to the highest political positions and military command without having to provide evidence of loyalty to the regime.

The Colonial War established a split between the military structure – heavily influenced by the western powers with democratic governments – and the political power of the regime. Some analysts see the " Botelho Moniz coup" of 1961 (also known as ''A Abrilada'') against the Portuguese government and backed by the U.S. administration,[ Luís Nuno Rodrigue]

"Orgulhosamente Sós"? Portugal e os Estados Unidos no início da década de 1960 – At the 22nd Meeting of History teachers of the Centro (region), Caldas da Rainha, April 2004

, Instituto de Relações Internacionais (International Relations Institute) as the beginning of this rupture, the origin of a lapse on the part of the regime to keep up a unique command center, an armed force prepared for threats of conflict in the colonies. This situation caused, as was verified later, a lack of coordination between the three general staffs (Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an ...

, and Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

).

The U.S. backed FNLA

The National Front for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola; abbreviated FNLA) is a political party and former militant organisation that fought for Angolan independence from Portugal in the war of independen ...

, which was headed by Holden Roberto

Álvaro Holden Roberto (January 12, 1923 – August 2, 2007) was an Angolan politician who founded and led the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) from 1962 to 1999. His memoirs are unfinished.

Early life

Roberto, son of Garcia Diasiwa ...

, attacked Portuguese settlers and Africans living in northern Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

from its bases in Congo-Léopoldville. Many of the victims were African farm workers living under labor contracts that required seasonal relocation from the desertified Southwest and Bailundo

Bailundo (pre-1975 Vila Teixeira da Silva) is a municipality, with a population of 294,494 (2014), and a town, with a population of 70,481 (2014), in the province of Huambo, Angola.

In the 1990s, Bailundo was the location of the headquarters of ...

areas of Angola. Photos of Africans killed by the FLNA, which included photos of decapitated civilians, men, women and children of both white and black ethnicity, was later displayed in the UN by Portuguese diplomats. The emergence of labor protests, attacks by newly organized guerrilla movements, and the Santa Maria hijacking by Henrique Galvão

Henrique Carlos da Mata Galvão (4 February 1895 – 25 June 1970) was a Portuguese military officer, writer and politician. He was initially a supporter but later become one of the strongest opponents of the Portuguese Estado Novo (Portugal), Es ...

began a path to open warfare in Angola.

According to historical researchers such as José Freire Antunes, U.S. President John F. Kennedy[A Guerra De Africa (1961–1974) by José Freire Antunes, Temas e Debates, ] sent a message to President António de Oliveira Salazar

António de Oliveira Salazar (, , ; 28 April 1889 – 27 July 1970) was a Portuguese dictator who served as President of the Council of Ministers from 1932 to 1968. Having come to power under the ("National Dictatorship"), he reframed the re ...

advising Portugal to abandon its African colonies shortly after the outbreak of violence in 1961. Instead, after a coup led by pro-U.S. forces failed to depose him, Salazar consolidated power and immediately sent reinforcements to the overseas territories, setting the stage for continued conflict in Angola. Similar situations played out in other overseas Portuguese territories.

Multiethnic societies, competing ideologies, and armed conflict in Portuguese Africa

By the 1950s, the European mainland Portuguese territory was inhabited by a society that was poorer and had a much higher illiteracy rate than the average Western European societies or those of North America. It was ruled by an authoritarian and conservative right-leaning dictatorship, known as the Estado Novo regime. By this time, the Estado Novo regime ruled both the Portuguese mainland and several centuries-old overseas territories as theoretically co-equal departments. The possessions were

By the 1950s, the European mainland Portuguese territory was inhabited by a society that was poorer and had a much higher illiteracy rate than the average Western European societies or those of North America. It was ruled by an authoritarian and conservative right-leaning dictatorship, known as the Estado Novo regime. By this time, the Estado Novo regime ruled both the Portuguese mainland and several centuries-old overseas territories as theoretically co-equal departments. The possessions were Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

, Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

, Macau

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a pop ...

, Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

, Portuguese Guinea

Portuguese Guinea ( pt, Guiné), called the Overseas Province of Guinea from 1951 until 1972 and then State of Guinea from 1972 until 1974, was a West African colony of Portugal from 1588 until 10 September 1974, when it gained independence as G ...

, Portuguese India

The State of India ( pt, Estado da Índia), also referred as the Portuguese State of India (''Estado Português da Índia'', EPI) or simply Portuguese India (), was a state of the Portuguese Empire founded six years after the discovery of a s ...

, Portuguese Timor

Portuguese Timor ( pt, Timor Português) was a colonial possession of Portugal that existed between 1702 and 1975. During most of this period, Portugal shared the island of Timor with the Dutch East Indies.

The first Europeans to arrive in th ...

, São João Baptista de Ajudá

SAO or Sao may refer to:

Places

* Sao civilisation, in Middle Africa from 6th century BC to 16th century AD

* Sao, a town in Boussé Department, Burkina Faso

* Saco Transportation Center (station code SAO), a train station in Saco, Maine, U. ...

, and São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe (; pt, São Tomé e Príncipe (); English: " Saint Thomas and Prince"), officially the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe ( pt, República Democrática de São Tomé e Príncipe), is a Portuguese-speaking ...

.

In reality, the relation of mainland Portuguese to their overseas possessions was that of colonial administrator to a subservient colony. Political, legislative, administrative, commercial, and other institutional relations between the colonies and Portugal-based individuals and organizations were numerous, though migration to, from, and between Portugal and its overseas departments was limited in size, due principally to the long distance and low annual income of the average Portuguese and that of the indigenous overseas populations.

An increasing number of African anticolonial movements called for total independence of the overseas African territories from Portugal. Some, like the U.S.-backed UPA wanted national self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a '' jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It sta ...

, while others wanted a new form of government based on Marxist principles. Portuguese leaders, including Salazar, attempted to stave off calls for independence by defending a policy of assimilation, multiracialism, and civilising mission

The civilizing mission ( es, misión civilizadora; pt, Missão civilizadora; french: Mission civilisatrice) is a political rationale for military intervention and for colonization purporting to facilitate the Westernization of indigenous pe ...

, or lusotropicalism, as a way of integrating Portuguese colonies, and their peoples, more closely with Portugal itself.

For the Portuguese ruling regime, the overseas empire was a matter of national interest

The national interest is a sovereign state's goals and ambitions (economic, military, cultural, or otherwise), taken to be the aim of government.

Etymology

The Italian phrase ''ragione degli stati'' was first used by Giovanni della Casa around ...

, to be preserved at all costs. As far back as 1919, a Portuguese delegate to the International Labour Conference in Geneva declared: "The assimilation of the so-called inferior races, by cross-breeding, by means of the Christian religion, by the mixing of the most widely divergent elements; freedom of access to the highest offices of state, even in Europe – these are the principles which have always guided Portuguese colonisation in Asia, in Africa, in the Pacific, and previously in America."

As late as the 1950s, the policy of "colorblind" access and mixing of races did not extend to all of Portugal's African territories, particularly Mozambique, where in tune with other minority white regimes of the day in southern Africa, the territory was segregated along racial lines. Strict qualification criteria ensured that less than one in 100 black Mozambicans became full Portuguese citizens.

Settlement subsidies

Numerous subsidies were offered by the Estado Novo regime to those Portuguese who agreed to settle in Angola or Mozambique, including a special premium for each Portuguese man who agreed to marry an African woman. Salazar himself was fond of restating the old Portuguese policy maxim that any indigenous resident of Portugal's African territories was, in theory, eligible to become a member of Portuguese government, even its president. In practice, this never took place, though trained black Africans living in Portugal's overseas African possessions were allowed to occupy positions in a variety of areas including the military, civil service, clergy, education, and private business

Business is the practice of making one's living or making money by producing or buying and selling products (such as goods and services). It is also "any activity or enterprise entered into for profit."

Having a business name does not separ ...

—providing they had the requisite education and technical skills.

While access to basic, secondary, and technical education remained poor until the 1960s, a few Africans were able to attend schools locally or in some cases in Portugal itself. This resulted in the advancement of certain black Portuguese Africans who became prominent individuals during the war and its aftermath, including

While access to basic, secondary, and technical education remained poor until the 1960s, a few Africans were able to attend schools locally or in some cases in Portugal itself. This resulted in the advancement of certain black Portuguese Africans who became prominent individuals during the war and its aftermath, including Samora Machel

Samora Moisés Machel (29 September 1933 – 19 October 1986) was a Mozambican military commander and political leader. A socialist in the tradition of Marxism–Leninism, he served as the first President of Mozambique from the country's ...

, Mário Pinto de Andrade

Mário Coelho Pinto de Andrade (21 August 1928 – 26 August 1990) was an Angolan poet and politician.

Biography

He was born in Golungo Alto, in Portuguese Angola, and studied philosophy at the University of Lisbon and sociology at the Sorbo ...

, Marcelino dos Santos

Marcelino dos Santos (20 May 1929 – 11 February 2020) was a Mozambican poet, revolutionary, and politician. As a young man he travelled to Portugal, and France for an education. He was a founding member of the ''Frente de Libertação de Mo� ...

, Eduardo Mondlane

Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane (20 June 1920 – 3 February 1969) was the President of the Mozambican Liberation Front (FRELIMO) from 1962, the year that FRELIMO was founded in Tanzania, until his assassination in 1969. Born in Mozambique, ...

, Agostinho Neto

António Agostinho da Silva Neto (17 September 1922 – 10 September 1979) was an Angolan politician and poet. He served as the first president of Angola from 1975 to 1979, having led the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) i ...

, Amílcar Cabral

Amílcar Lopes da Costa Cabral (; – ) was a Bissau-Guinean and Cape Verdean agricultural engineer, pan-Africanist, intellectual, poet, theoretician, revolutionary, political organizer, nationalist and diplomat. He was one of Africa's foremo ...

, Jonas Savimbi

Jonas Malheiro Savimbi (; 3 August 1934 – 22 February 2002) was an Angolan revolutionary politician and rebel military leader who founded and led the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). UNITA waged a guerrilla war agai ...

, Joaquim Chissano

Joaquim Alberto Chissano (born 22 October 1939) is a politician who served as the second President of Mozambique, from 1986 to 2005. He is credited with transforming the war-torn country of Mozambique into one of the most successful African demo ...

, and Graça Machel

Graça Machel (; née Simbine; , born 17 October 1945) is a Mozambican politician and humanitarian. She is the widow of former President of Mozambique Samora Machel (1975–1986) and former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela (1998–20 ...

. Two state-run universities were founded in Portuguese Africa in the 1962 by the Minister of the Overseas Adriano Moreira (the '' Universidade de Luanda'' in Angola and the '' Universidade de Lourenço Marques'' in Mozambique, awarding a range of degrees from engineering to medicine); however, most of their students came from Portuguese families living in the two territories. Several personalities in Portuguese society, including one of the most idolized sports stars in Portuguese football history, a black football player from Portuguese East Africa

Portuguese Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique) or Portuguese East Africa (''África Oriental Portuguesa'') were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese colony. Portuguese Mozambique originally ...

named Eusébio

Eusébio da Silva Ferreira (; 25 January 1942 – 5 January 2014), nicknamed the "Black Panther", the "Black Pearl" or "O Rei" ("The King"), was a Portuguese footballer who played as a striker. He is considered one of the greatest players of ...

, were other examples of efforts towards assimilation and multiracialism in the post-World War II period.

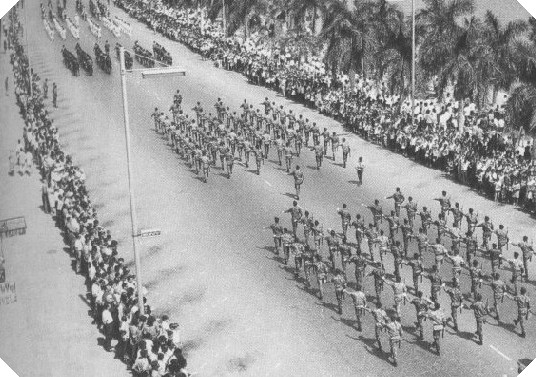

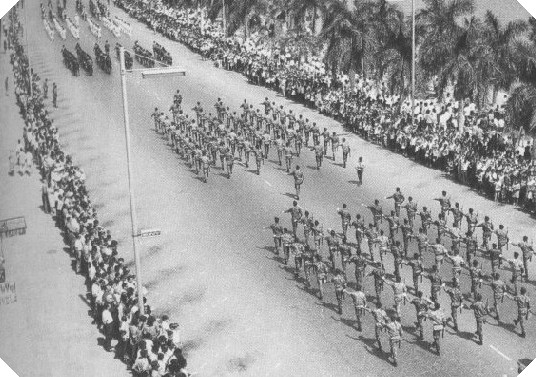

Composition of the Portuguese Army

According to Mozambican historian João Paulo Borges Coelho, the Portuguese colonial army was largely segregated along terms of race and ethnicity until 1960. There were originally three classes of soldier in Portuguese overseas service: commissioned soldiers (whites), overseas soldiers (African ''assimilados''), and native or indigenous Africans (''indigenato). These categories were renamed to first, second, and third class in 1960, which effectively corresponded to the same categories. Later, after official discrimination based on skin colour was outlawed, some Portuguese commanders such as General António de Spínola

António Sebastião Ribeiro de Spínola (generally referred to as António de Spínola, ;This surname, however, was not accompanied by the grammatical nobiliary particle "de". 11 April 1910 – 13 August 1996) was a Portuguese military of ...

began a process of "Africanization" of Portuguese forces fighting in Africa. In Portuguese Guinea, this included a large increase in African recruitment along with the establishment of all-black military formations such as the Black Militias (''Milícias negras'') commanded by Major Carlos Fabião and the African Commando Battalion (''Batalhão de Comandos Africanos'') commanded by General Almeida Bruno.[Afonso, Aniceto and Gomes, Carlos de Matos, ''Guerra Colonial'' (2000), , p. 340]

While sub-Saharan African soldiers constituted a mere 18% of the total number of troops fighting in Portugal's African territories in 1961, this percentage rose dramatically over the next 13 years, with black soldiers constituting over 50% of all government forces fighting in Africa by April 1974. Coelho noted that perceptions of African soldiers varied a good deal among senior Portuguese commanders during the conflict in Angola, Guinea, and Mozambique. General Francisco da Costa Gomes

Francisco da Costa Gomes, ComTE, GOA (; 30 June 1914 – 31 July 2001) was a Portuguese military officer and politician, the 15th president of Portugal (the second after the Carnation Revolution).

Life

He was one of the eleven children of A ...

, perhaps the most successful counterinsurgency commander, sought good relations with local civilians, and employed African units within the framework of an organized counterinsurgency plan.[Coelho, João Paulo Borges, ''African Troops in the Portuguese Colonial Army, 1961-1974: Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique'', Portuguese Studies Review 10 (1) (2002), pp. 129–150] General António de Spínola

António Sebastião Ribeiro de Spínola (generally referred to as António de Spínola, ;This surname, however, was not accompanied by the grammatical nobiliary particle "de". 11 April 1910 – 13 August 1996) was a Portuguese military of ...

, by contrast, appealed for a more political and psycho-social use of African soldiers.mobilized

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and t ...

forces. Under the Salazar regime, a military draft required all males to serve three years of obligatory military service; many of those called up to active military duty were deployed to combat zones in Portugal's African overseas provinces. The national service period was increased to four years in 1967, and virtually all conscripts faced a mandatory two-year tour of service in Africa.[Humbaraci, Arslan and Muchnik, Nicole, ''Portugal's African Wars'', New York: Joseph Okpaku Publishing Co., (1974), pp. 100–102] With illiteracy rates approaching 99% and almost no African enrollment in secondary schools,color blindness

Color blindness or color vision deficiency (CVD) is the decreased ability to see color or differences in color. It can impair tasks such as selecting ripe fruit, choosing clothing, and reading traffic lights. Color blindness may make some aca ...

policy with more spending in education and training opportunities, which started to produce a larger number of black high ranked professionals, including military personnel.

Intervention by Cold War powers

After the World War II, as communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

and anticolonial

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

ideologies spread across Africa, many clandestine political movements were established in support of independence using various interpretations of Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

revolutionary ideology. These new movements seized on anti-Portuguese and anti-colonial sentiment to advocate the complete overthrow of existing governmental structures in Portuguese Africa. These movements alleged that Portuguese policies and development plans were primarily designed by the ruling authorities for the benefit of the territories' ethnic Portuguese population at the expense of local tribal control, the development of native communities, and the majority of the indigenous population, who suffered both state-sponsored discrimination and enormous social pressure to comply with government policies largely imposed from Lisbon. Many felt they had received too little opportunity or resources to upgrade their skills and improve their economic and social situation to a degree comparable to that of the Europeans. Statistically, Portuguese Africa's white Portuguese population were indeed wealthier and more educated than the indigenous majority.

After conflict erupted between the UPA and MPLA and Portuguese military forces, U.S. President John F. Kennedy[Abbott, Peter and Rodrigues, Manuel, ''Modern African Wars 2: Angola and Mozambique 1961–74'', Osprey Publishing (1998), p. 34]

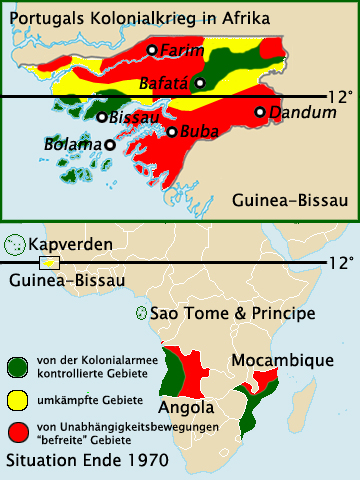

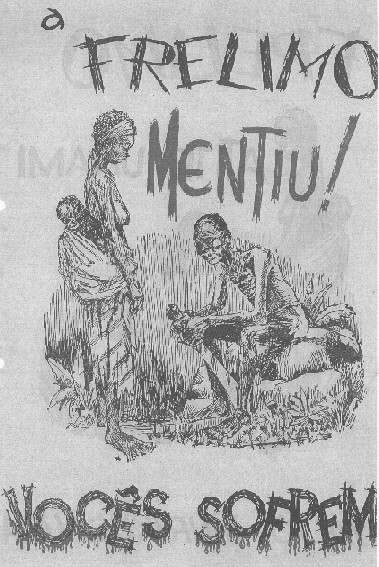

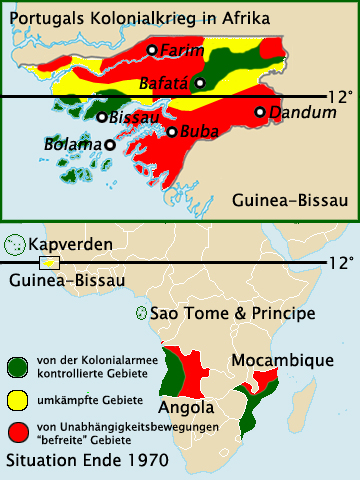

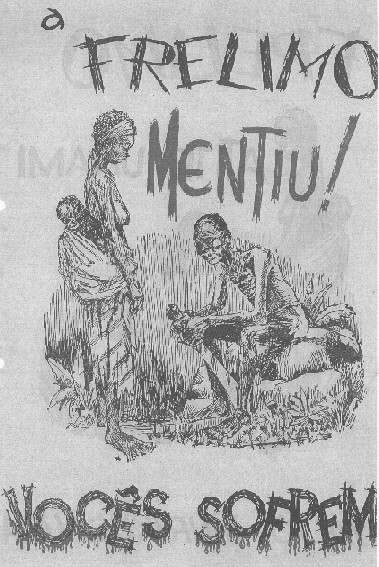

While Portuguese forces had all but won the guerrilla war in Angola, and had stalemated FRELIMO in Mozambique, colonial forces were forced on the defensive in Guinea, where PAIGC forces had carved out a large area of the rural countryside under effective insurgent control, using Soviet-supplied AA cannon and ground-to-air missiles to protect their encampments from attack by Portuguese air assets.

While Portuguese forces had all but won the guerrilla war in Angola, and had stalemated FRELIMO in Mozambique, colonial forces were forced on the defensive in Guinea, where PAIGC forces had carved out a large area of the rural countryside under effective insurgent control, using Soviet-supplied AA cannon and ground-to-air missiles to protect their encampments from attack by Portuguese air assets.[Dos Santos, Manuel, ''Disparar os Strela'', Depoimentos, Quinta-feira, 28 de Maio de 2009, retrieved 26 May 2011] Overall, the increasing success of Portuguese counterinsurgency operations and the inability or unwillingness of guerrilla forces to destroy the economy of Portugal's African territories was seen as a victory for the Portuguese government policies.

The Soviet Union, realising that military success by insurgents in Angola and Mozambique was becoming increasingly remote, shifted much of its military support to the PAIGC in Guinea, while increasing diplomatic efforts to isolate Portugal from the world community. The success of the socialist bloc in isolating Portugal diplomatically extended inside Portugal itself into the armed forces, where younger officers disenchanted with the Estado Novo regime and promotional opportunities began to identify ideologically with those calling for overthrow of the government and the establishment of a state based on Marxist principles.

The Soviet Union, realising that military success by insurgents in Angola and Mozambique was becoming increasingly remote, shifted much of its military support to the PAIGC in Guinea, while increasing diplomatic efforts to isolate Portugal from the world community. The success of the socialist bloc in isolating Portugal diplomatically extended inside Portugal itself into the armed forces, where younger officers disenchanted with the Estado Novo regime and promotional opportunities began to identify ideologically with those calling for overthrow of the government and the establishment of a state based on Marxist principles.[Stewart Lloyd-Jones, ISCTE (Lisbon)]

Portugal's history since 1974

"The Portuguese Communist Party (PCP–Partido Comunista Português), which had courted and infiltrated the MFA from the very first days of the revolution, decided that the time was now right for it to seize the initiative. Much of the radical fervour that was unleashed following Spínola's coup attempt was encouraged by the PCP as part of their own agenda to infiltrate the MFA and steer the revolution in their direction.", Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril, University of Coimbra

The University of Coimbra (UC; pt, Universidade de Coimbra, ) is a public research university in Coimbra, Portugal. First established in Lisbon in 1290, it went through a number of relocations until moving permanently to Coimbra in 1537. The u ...

Nicolae Ceaușescu

Nicolae Ceaușescu ( , ; – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian communist politician and dictator. He was the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989, and the second and last Communist leader of Romania. He ...

's Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

offered consistent support to the African liberation movements. Romania was the first state that recognized the independence of Guinea-Bissau, as well as the first to sign agreements with the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde

The African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde ( pt, Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, PAIGC) is a political party in Guinea-Bissau. Originally formed to peacefully campaign for independence from ...

and Angola's MPLA

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, abbr. MPLA), for some years called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan left-wing, social dem ...

. In May 1974, Ceaușescu reaffirmed Romania's support for Angolan independence. As late as September 1975, Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

publicly supported all three Angolan liberation movements (FNLA, MPLA and UNITA). In the spring of 1972, Romania allowed FRELIMO to open a diplomatic mission in Bucharest, the first of its kind in Eastern Europe. In 1973, Ceaușescu recognized FRELIMO as "the only legitimate representative of the Mozambican people", an important precedent. Samora Machel stressed that—during his trip to the Soviet Union—he and his delegation were granted "the status that we are entitled to" due to Romania's official recognition of FRELIMO. In terms of material support, Romanian trucks were used to transport weapons and ammunition to the front, as well as medicine, school material and agricultural equipment. Romanian tractors contributed to the increase in agricultural production. Romanian weapons and uniforms—reportedly of "excellent quality"—played a "decisive role" in FRELIMO's military progress. It was in early 1973 that FRELIMO made these statements about Romania's material support, in a memorandum sent to the Romanian Communist Party

The Romanian Communist Party ( ro, Partidul Comunist Român, , PCR) was a communist party in Romania. The successor to the pro-Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave ideological endorsement to a communist revolution that wo ...

's Central Committee. In 1974, Romania became the first country to formally recognize Mozambique.

By early 1974, guerrilla operations in Angola and Mozambique had been reduced to sporadic ambush operations against the Portuguese in the rural countryside areas, far from the main centers of population.Portuguese Guinea

Portuguese Guinea ( pt, Guiné), called the Overseas Province of Guinea from 1951 until 1972 and then State of Guinea from 1972 until 1974, was a West African colony of Portugal from 1588 until 10 September 1974, when it gained independence as G ...

, where PAIGC guerrilla operations, strongly supported by neighbouring allies like Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

and Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

, were largely successful in liberating and securing large areas of Portuguese Guinea. According some historians, Portugal recognized its inability to win the conflict in Guinea at the outset, but was forced to fight on to prevent an independent Guinea from serving as an inspirational model for insurgents in Angola and Mozambique.

Despite continuing attacks by insurgent forces against targets throughout the Portuguese African territories, the economies of both Portuguese Angola and Mozambique had actually improved each year of the conflict, as had the economy of Portugal proper. Angola enjoyed an unprecedented economic boom during the 1960s, and the Portuguese government built new transportation networks to link the well-developed and highly urbanized coastal strip with the remote inland regions of the territory.Armed Forces Movement

230px, A mural dedicated to the MFA, it reads: "Towards freedom. Long live the 25th of April!"

The Armed Forces Movement ( pt, Movimento das Forças Armadas; MFA) was an organization of lower-ranking, politically left-leaning officers in the Por ...

(MFA), overthrew the Estado Novo regime in what came to be known as the Carnation Revolution

The Carnation Revolution ( pt, Revolução dos Cravos), also known as the 25 April ( pt, 25 de Abril, links=no), was a military coup by left-leaning military officers that overthrew the authoritarian Estado Novo regime on 25 April 1974 in Lisbo ...

in Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

, Portugal.South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

, which launched a deep border incursion operation into Angola to attack guerrilla-controlled areas of the country following the coup.

Theaters of war

Angola

On 3 January 1961 Angolan peasants in the region of

On 3 January 1961 Angolan peasants in the region of Baixa de Cassanje

Baixa de Cassanje, also called Baixa de Kassanje is a non-sovereign kingdom in Angola. Kambamba Kulaxingo was its king until his death in 2006.

Presently, Dianhenga Aspirante Mjinji Kulaxingo serves as the king.

History

The region of Baixa de ...

, Malanje, boycotted the Cotonang Company's cotton fields where they worked, demanding better working conditions and higher wages. Cotonang, a company owned by European investors, used native African labor to produce an annual cotton crop for export abroad. The uprising, later to become known as the Baixa de Cassanje revolt

The Baixa de Cassanje revolt () is considered the first confrontation of the War of Independence in Angola and the Portuguese Colonial War throughout the Portuguese overseas provinces. The uprising began on 3 January 1961 in the region of Bai ...

, was led by two previously unknown Angolans, António Mariano and Kulu-Xingu. During the protests, African workers burned their identification cards and attacked Portuguese traders. The Portuguese Air Force responded to the rebellion by bombing twenty villages in the area, allegedly using napalm

Napalm is an incendiary mixture of a gelling agent and a volatile petrochemical (usually gasoline (petrol) or diesel fuel). The name is a portmanteau of two of the constituents of the original thickening and gelling agents: coprecipitated alu ...

in an attack that resulted in some 400 indigenous Angolan deaths.

In the Portuguese Overseas Province of Angola

Overseas may refer to:

* ''Overseas'' (album), a 1957 album by pianist Tommy Flanagan and his trio

* Overseas (band), an American indie rock band

* "Overseas" (song), a 2018 song by American rappers Desiigner and Lil Pump

* "Overseas" (Tee Grizzley ...

, the call for revolution was taken up by two insurgent groups, the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, abbr. MPLA), for some years called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan left-wing, social dem ...

), and the União das Populações de Angola (UPA), which became the National Liberation Front of Angola

The National Front for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola; abbreviated FNLA) is a political party and former militant organisation that fought for Angolan independence from Portugal in the war of independe ...

(FNLA) in 1962. The MPLA commenced activities in an area of Angola known as the ''Zona Sublevada do Norte'' (ZSN or the Rebel Zone of the North), consisting of the provinces of Zaire, Uíge and Cuanza Norte.

Insurgent attacks

On February 4, 1961, using arms largely captured from Portuguese soldiers and police

On February 4, 1961, using arms largely captured from Portuguese soldiers and police[Humbaraci, Arslan and Muchnik, Nicole, ''Portugal's African Wars'', New York: Joseph Okpaku Publishing Co., (1974), p. 114] 250 MPLA guerrillas attacked the São Paulo fortress prison and police headquarters in Luanda in an attempt to free what it termed 'political prisoners'. The attack was unsuccessful, and no prisoners were released, but seven Portuguese policemen and forty Angolans were killed, mostly MPLA insurgents.Holden Roberto

Álvaro Holden Roberto (January 12, 1923 – August 2, 2007) was an Angolan politician who founded and led the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) from 1962 to 1999. His memoirs are unfinished.

Early life

Roberto, son of Garcia Diasiwa ...

launched an incursion into the Bakongo

The Kongo people ( kg, Bisi Kongo, , singular: ; also , singular: ) are a Bantu ethnic group primarily defined as the speakers of Kikongo. Subgroups include the Beembe, Bwende, Vili, Sundi, Yombe, Dondo, Lari, and others.

They have lived a ...

region of northern Angola with 4,000–5,000 insurgents. The insurgents called for local Bantu farmworkers and villagers to join them, unleashing an orgy of violence and destruction. The insurgents attacked farms, government outposts, and trading centers, killing everyone they encountered, including women, children and newborns.[Massacres em Africa]

Felícia Cabrita

In surprise attacks, drunken and buoyed by belief in tribal spells that they believed made them immune to bullets, the attackers spread terror and destruction in the whole area.[George, Edward, ''The Cuban Intervention in Angola, 1965–1991'', New York: Frank Cass Publishing Co., (2005) pp. 9–10]

Portuguese response

In response, Portuguese Armed Forces instituted a harsh policy of reciprocity by torturing and massacring rebels and protesters. Some Portuguese soldiers decapitated rebels and impaled their heads on stakes, pursuing a policy of "

In response, Portuguese Armed Forces instituted a harsh policy of reciprocity by torturing and massacring rebels and protesters. Some Portuguese soldiers decapitated rebels and impaled their heads on stakes, pursuing a policy of "an eye for an eye

"An eye for an eye" ( hbo, עַיִן תַּחַת עַיִן, ) is a commandment found in the Book of Exodus 21:23–27 expressing the principle of reciprocal justice measure for measure. The principle exists also in Babylonian law.

In Roman c ...

, a tooth for a tooth". Much of the initial offensive operations against Angolan UPA and MPLA insurgents was undertaken by four companies of '' Caçadores Especiais'' (''Special Hunter'') troops skilled in light infantry and antiguerrilla tactics, and who were already stationed in Angola at the outbreak of fighting. Individual Portuguese counterinsurgency commanders such as Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

Fernando Robles

Fernando Augusto Colaço Leal Robles or Fernando Robles (born 15 August 1940) is a Portuguese former Second Lieutenant (later Colonel) who participated in initial counterinsurgency operations against insurgent União dos Povos de Angola (UPA) gu ...

of the ''6ª Companhia de Caçadores Especiais'' became well known throughout the country for their ruthlessness in hunting down insurgents.

The Portuguese Army steadily pushed the UPA back across the border into Congo-Kinshasa in a brutal counteroffensive that also displaced some 150,000 Bakongo refugees, taking control of Pedra Verde, the UPA's last base in northern Angola, on 20 September 1961.Cabinda province

Cabinda (formerly called Portuguese Congo, kg, Kabinda) is an exclave and province of Angola in Africa, a status that has been disputed by several political organizations in the territory. The capital city is also called Cabinda, known locall ...

, the central plateaus, and eastern and southeastern Angola.

By most accounts, Portugal's counterinsurgency campaign in Angola was the most successful of all its campaigns in the Colonial War.Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

and Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

were so large that the eastern part of Angola's territory was known by the Portuguese as ''Terras do Fim do Mundo'' (the lands of the far side of the world).

Another factor was internecine struggles between three competing revolutionary movements – FNLA, MPLA, and UNITA – and their guerrilla armies. For most of the conflict, the three rebel groups spent as much time fighting each other as they did fighting the Portuguese. For example, during the 1961 ''Ferreira Incident'', a UPA patrol captured 21 MPLA insurgents as prisoners, then summarily executed them on 9 October, sparking open confrontation between the two insurgent groups.

Strategy also played a role, as a successful hearts and minds campaign led by General Francisco da Costa Gomes

Francisco da Costa Gomes, ComTE, GOA (; 30 June 1914 – 31 July 2001) was a Portuguese military officer and politician, the 15th president of Portugal (the second after the Carnation Revolution).

Life

He was one of the eleven children of A ...

helped blunt the influence of the various revolutionary movements. Finally, as in Mozambique, Portuguese Angola was able to receive support of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

. South African military operations proved to be of significant assistance to Portuguese military forces in Angola, who sometimes referred to their South African counterparts as ''primos'' (cousins).

Several unique counter-insurgency forces were developed and deployed in the campaign in Angola:

* '' Batalhões de Caçadores Pára-quedistas'' (Paratrooper Hunter Battalions): employed throughout the conflicts in Africa, were the first forces to arrive in Angola when the war began.

* ''Comandos'' (Commandos

Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin">40_Commando.html" ;"title="Royal Marines from 40 Commando">Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin area of Afghanistan are pictured

A commando is a combatant, or operativ ...

): born out of the war in Angola, they were created as an elite counter- guerrilla special forces, and later used in Guinea and Mozambique.

* ''Caçadores Especiais'' ( Special Hunters): were in Angola from the start of the conflict in 1961.

* ''Fiéis'' (Faithfuls): a force composed by Katanga exiles, black soldiers that opposed the rule of Mobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the president of Zaire from 1965 to 1997 (known as the Democratic Republic o ...

in Congo-Kinshasa

* ''Leais'' (Loyals): a force composed by exiles from Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

, black soldiers that were against Kenneth Kaunda

Kenneth David Kaunda (28 April 1924 – 17 June 2021), also known as KK, was a Zambian politician who served as the first President of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He was at the forefront of the struggle for independence from British rule. Diss ...

* ''Grupos Especiais'' ( Special Groups): units of volunteer black soldiers that had commando training; also used in Mozambique

* ''Tropas Especiais'' (Special Troops): the name of Special Groups in Cabinda

* '' Flechas'' (Arrows): a successful indigenous formation of scouts, controlled by the Portuguese secret police PIDE/DGS

The International and State Defense Police ( pt, Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado; PIDE) was a Portuguese security agency that existed during the '' Estado Novo'' regime of António de Oliveira Salazar. Formally, the main roles of the ...

, and composed by Bushmen

The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are members of various Khoe languages, Khoe, Tuu languages, Tuu, or Kxʼa languages, Kxʼa-speaking indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures that are the Indigenous peoples of Africa, first cultures of Sout ...

that specialized in tracking, reconnaissance and pseudo-terrorist operations. Also employed in Mozambique, the ''Flechas'' inspired the formation of the Rhodesian Selous Scouts

The Selous Scouts was a special forces unit of the Rhodesian Army that operated during the Rhodesian Bush War from 1973 until the reconstitution of the country as Zimbabwe in 1980. It was mainly responsible for infiltrating the black majority ...

.

* ''Grupo de Cavalaria Nº1'' (1st Cavalry Group): a mounted cavalry unit, armed with the 7.62 mm Espingarda m/961 rifle and the m/961 Walther P38

The Walther P38 (originally written Walther P.38) is a 9 mm semi-automatic pistol that was developed by Carl Walther GmbH as the service pistol of the Wehrmacht at the beginning of World War II. It was intended to replace the costly Luger P08 ...

pistol, tasked with reconnaissance and patrolling

Patrolling is a military tactic. Small groups or individual units are deployed from a larger formation to achieve a specific objective and then return. The tactic of patrolling may be applied to ground troops, armored units, naval units, and co ...

. The 1st was also known as the " Angolan Dragoons" (''Dragões de Angola''). The Rhodesians also later developed a similar concept of horse-mounted counter-insurgency forces, forming the Grey's Scouts

Grey's Scouts were a Rhodesian mounted infantry unit raised in July 1975 and named after George Grey, a British soldier and governor. Based in Salisbury (now Harare) it patrolled Rhodesia's borders during the Rhodesian Bush War, and then became ...

.

* ''Batalhão de Cavalaria 1927'' (1927 Cavalry Battalion): a tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful ...

unit equipped with the M5A1 tank. The battalion was used for supporting infantry forces and as a rapid reaction force

A rapid reaction force is a military or police unit designed to respond in very short time frames to emergencies. When used in reference to police forces such as SWAT teams, the time frame is minutes, while in military applications, such as with t ...

. Again the Rhodesians developed a similar unit, forming the Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment.

Portuguese Guinea

In

In Portuguese Guinea

Portuguese Guinea ( pt, Guiné), called the Overseas Province of Guinea from 1951 until 1972 and then State of Guinea from 1972 until 1974, was a West African colony of Portugal from 1588 until 10 September 1974, when it gained independence as G ...

(also referred to as Guinea at that time), the Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde

The African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde ( pt, Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, PAIGC) is a political party in Guinea-Bissau. Originally formed to peacefully campaign for independence from ...

(PAIGC) started fighting in January 1963. Its guerrilla fighters attacked the Portuguese headquarters in Tite, located to the south of Bissau

Bissau () is the capital, and largest city of Guinea-Bissau. Bissau had a population of 492,004. Bissau is located on the Geba River estuary, off the Atlantic Ocean, and is Guinea-Bissau's largest city, major port, and its administrative and ...

, the capital, near the Corubal river. Similar actions quickly spread across the entire colony, requiring a strong response from the Portuguese forces.

The war in Guinea has been termed "Portugal's Vietnam". The PAIGC was well-trained, well-led, and equipped and received substantial support from safe havens in neighboring countries like Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

and the Republic of Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

(Guinea-Conakry). The jungles of Guinea and the proximity of the PAIGC's allies near the border proved to be of significant advantage in providing tactical superiority during cross-border attacks and resupply missions for the guerrillas.

The conflict in Portuguese Guinea involving the PAIGC guerrillas and the Portuguese Army

The Portuguese Army ( pt, Exército Português) is the land component of the Armed Forces of Portugal and is also its largest branch. It is charged with the defence of Portugal, in co-operation with other branches of the Armed Forces. With it ...

proved the most intense and damaging of all conflicts in the Portuguese Colonial War, blocking Portuguese attempts to pacify the disputed territory via new economic and socioeconomic policies that had been applied with some success in Portuguese Angola

Portuguese Angola refers to Angola during the historic period when it was a territory under Portuguese rule in southwestern Africa. In the same context, it was known until 1951 as Portuguese West Africa (officially the State of West Africa).

I ...

and Portuguese Mozambique

Portuguese Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique) or Portuguese East Africa (''África Oriental Portuguesa'') were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese colony. Portuguese Mozambique originally ...

. In 1965 the war spread to the eastern part of Guinea; that year, the PAIGC carried out attacks in the north of the territory where at the time only the Front for the Liberation and Independence of Guinea (FLING), a minor insurgent group, was active. By this time, the PAIGC had begun to openly receive military support from Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and the Soviet Union.