Piano Concerto No. 2 (Rachmaninoff) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in

In June 1900, after receiving an invitation to perform ''

In June 1900, after receiving an invitation to perform ''

His debut with an American orchestra occurred on 8 November 1909, performing the concerto at the

His debut with an American orchestra occurred on 8 November 1909, performing the concerto at the

The opening

The opening

In 1901, Gutheil published the concerto along with the composer's two piano arrangement. Austrian violinist and composer

In 1901, Gutheil published the concerto along with the composer's two piano arrangement. Austrian violinist and composer

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor

C minor is a minor scale based on C, consisting of the pitches C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. Its key signature consists of three flats. Its relative major is E major and its parallel major is C major.

The C natural minor scale is:

:

Cha ...

, Op. 18, is a concerto

A concerto (; plural ''concertos'', or ''concerti'' from the Italian plural) is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The typi ...

for piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keyboa ...

and orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families.

There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* bowed string instruments, such as the violin, viola, c ...

composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one o ...

between June 1900 and April 1901. From the summer to the autumn of 1900, he worked on the second and third movements

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

of the concerto, with the first movement causing him difficulties. Both movements of the unfinished concerto were first performed with him as soloist and his cousin Alexander Siloti making his conducting debut on . The first movement was finished in 1901 and the complete work had an astoundingly successful premiere on , again with the composer as soloist and Siloti conducting. Gutheil Gutheil is a German surname of:

* Emil Arthur Gutheil (1889–1959), Polish-American psychiatrist

* (1868–1914), German conductor and composer, husband of Marie Gutheil-Schoder

* Marie Gutheil-Schoder (1874–1935), German soprano

* (born 1959 ...

published the work the same year. The piece established Rachmaninoff's fame as a concerto composer and is one of his most enduringly popular pieces.

After the disastrous 1897 premiere of his First Symphony, Rachmaninoff suffered a psychological breakdown that prevented composition for three years. Although depression sapped his energy, he still engaged in performance. Conducting

Conducting is the art of directing a musical performance, such as an orchestral or choral concert. It has been defined as "the art of directing the simultaneous performance of several players or singers by the use of gesture." The primary duti ...

and piano lessons became necessary to ease his financial position. In 1899, he was supposed to perform the Second Piano Concerto in London, which he had not composed yet due to illness, and instead made a successful conducting debut. The success led to an invitation to return next year with his First Piano Concerto; however, he promised to reappear with a newer and better one. Rachmaninoff was later invited to Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

's home in hopes of having his writer's block

Writer's block is a condition, primarily associated with writing, in which an author is either unable to produce new work or experiences a creative slowdown. Mike Rose found that this creative stall is not a result of commitment problems or th ...

revoked, but the meeting only worsened his situation. Relatives decided to introduce him to the neurologist Nikolai Dahl

Nikolai Vladimirovich Dahl, often called Nicolai Dahl (russian: Николай Владимирович Даль) (July 17, 1860 – 1939) was a Russian Empire physician. He is most notable for his successful treatment of the composer Sergei R ...

, whom he visited daily from January to April 1900, which helped restore his health and confidence in composition. Rachmaninoff dedicated the concerto to Dahl for successfully treating him.

History

Background

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one o ...

had been working on his First Symphony from January to September 1895. In 1896, after a long hiatus, the music publisher and philanthropist Mitrofan Belyayev

Mitrofan Petrovich Belyayev (russian: Митрофа́н Петро́вич Беля́ев; old style 10/22 February 1836, St. Petersburg22 December 1903/ 4 January 1904) was an Imperial Russian music publisher, outstanding philanthropist, a ...

agreed to include it at one of his Saint Petersburg Russian Symphony Concerts The Russian Symphony Concerts were a series of Russian classical music concerts hosted by timber magnate and musical philanthropist Mitrofan Belyayev in St. Petersburg as a forum for young Russian composers to have their orchestral works performed. ...

. However, there were setbacks: complaints were raised about the symphony by his teacher Sergei Taneyev

Sergey Ivanovich Taneyev (russian: Серге́й Ива́нович Тане́ев, ; – ) was a Russian composer, pianist, teacher of composition, music theorist and author.

Life

Taneyev was born in Vladimir, Vladimir Governorate, Russia ...

upon receiving its score, which elicited revisions by Rachmaninoff, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

expressed dissatisfaction during rehearsal. Eventually, the symphony was scheduled to be premiered in March 1897. Before the due date, he was nervous but optimistic due to his prior successes, which included winning the Moscow Conservatory

The Moscow Conservatory, also officially Moscow State Tchaikovsky Conservatory (russian: Московская государственная консерватория им. П. И. Чайковского, link=no) is a musical educational inst ...

Great Gold Medal and earning the praise of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

. The premiere, however, was a disaster; Rachmaninoff listened to the cacophonous performance backstage to avoid getting humiliated by the audience and eventually left the hall when the piece finished. The symphony was brutally panned by critics, and apart from issues with the piece, the poor performance of the possibly drunk conductor, Alexander Glazunov

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov; ger, Glasunow (, 10 August 1865 – 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 ...

, was also to blame. César Cui

César Antonovich Cui ( rus, Це́зарь Анто́нович Кюи́, , ˈt͡sjezərʲ ɐnˈtonəvʲɪt͡ɕ kʲʊˈi, links=no, Ru-Tsezar-Antonovich-Kyui.ogg; french: Cesarius Benjaminus Cui, links=no, italic=no; 13 March 1918) was a Ru ...

wrote:

If there were a conservatoire in Hell, if one of its talented students were instructed to write a programme symphony on " The Seven Plagues of Egypt", and if he were to compose a symphony like Mr Rachmaninoff's, then he would have fulfilled his task brilliantly and delighted the inmates of Hell.Rachmaninoff initially remained aloof to the failure of his symphony, but upon reflection, suffered a psychological breakdown that stopped his compositional output for three years. He adopted a lifestyle of heavy drinking to forget about his problems. Depression consumed him, and although he rarely composed, he still engaged in performance, accepting a conducting position by the Russian entrepreneur

Savva Mamontov

Savva Ivanovich Mamontov (russian: Са́вва Ива́нович Ма́монтов, ; 3 October 1841 (15 October N.S.), Yalutorovsk – 6 April 1918, Moscow) was a Russian industrialist, merchant, entrepreneur and patron of the arts.

Busine ...

at the Moscow Private Russian Opera

The Private Opera (russian: Частная Опера), also known as:

*The Russian Private Opera ();

*Moscow Private Russian Opera, ();

*Mamontov's Private Russian Opera in Moscow ();

*Korotkov's Theatre (, 1885-1888);

*Vinter's Theatre (, ...

from 1897 to 1898. It provided income for the cash-strapped Rachmaninoff; he eventually left as it didn't allow time for other activities and due to the incompetence of the theater, which turned piano lessons into his main source of income.

At the end of 1898, Rachmaninoff was invited to perform in London in April 1899, where he was expected to play his Second Piano Concerto. However, he wrote to the London Philharmonic Society that he couldn't finish a second concerto due to illness. The society then requested he play his First Piano Concerto, but he declined, dismissing it as a student piece. Instead, he offered to conduct one of his orchestral pieces, to which the society agreed, provided he also performed at the piano. He made a successful conducting debut, performing '' The Rock'' and playing piano pieces such as his hackneyed Prelude in C-sharp minor. The society secretary Francesco Berger

Francesco Berger (10 June 1834 – 26 April 1933) was a pianist and composer. He was a teacher of the piano and a professor at the Royal Academy of Music but is mostly remembered as the honorary secretary of the Philharmonic Society for 27 years ...

invited him to return next year with a performance of the First Concerto. However, he promised to return with a newer and better one, although he did not perform it there until 1908. Alexander Goldenweiser, a peer from the same conservatory, wanted to play his new concerto at a Belyayev concert in Saint Petersburg, thinking its consummation was inevitable. Rachmaninoff, who had thoughts of composing it three years earlier, sent a letter to him stating that nothing had been penned so far.

For the rest of the summer and autumn of 1899, Rachmaninoff's unproductiveness worsened his depression. A friend of the Satins (relatives of Rachmaninoff), in an attempt to revoke the depressed composer's writer's block

Writer's block is a condition, primarily associated with writing, in which an author is either unable to produce new work or experiences a creative slowdown. Mike Rose found that this creative stall is not a result of commitment problems or th ...

, suggested he visit Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

. However, his visit to the querulous author only served to increase his despondency, and he became so self-critical that he was rendered unable to compose. The Satins, anxious about his well-being, persuaded him to visit Nikolai Dahl

Nikolai Vladimirovich Dahl, often called Nicolai Dahl (russian: Николай Владимирович Даль) (July 17, 1860 – 1939) was a Russian Empire physician. He is most notable for his successful treatment of the composer Sergei R ...

, a neurologist who specialized in hypnosis

Hypnosis is a human condition involving focused attention (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI), reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion.In 2015, the American Psychologica ...

, with whom they had a good experience. Desperate, he agreed without hesitation. From January to April 1900, he visited him daily free of charge. Dahl restored Rachmaninoff's health as well as his confidence to compose. Himself a musician, Dahl engaged in lengthy conversations surrounding music with Rachmaninoff, and would repeat a triptych

A triptych ( ; from the Greek language, Greek adjective ''τρίπτυχον'' "''triptukhon''" ("three-fold"), from ''tri'', i.e., "three" and ''ptysso'', i.e., "to fold" or ''ptyx'', i.e., "fold") is a work of art (usually a panel painting) t ...

formula while the composer was half-asleep: "You will begin to write your concerto ... You will work with great facility ... The concerto will be of an excellent quality". Even though the results were not readily evident, they were still successful.

Composition and premiere

In June 1900, after receiving an invitation to perform ''

In June 1900, after receiving an invitation to perform ''Mefistofele

''Mefistofele'' () is an opera in a prologue and five acts, later reduced to four acts and an epilogue, the only completed opera with music by the Italian composer-librettist Arrigo Boito (there are several completed operas for which he was libret ...

'' in La Scala

La Scala (, , ; abbreviation in Italian of the official name ) is a famous opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the ' (New Royal-Ducal Theatre alla Scala). The premiere performan ...

, Feodor Chaliapin

Feodor Ivanovich Chaliapin ( rus, Фёдор Ива́нович Шаля́пин, Fyodor Ivanovich Shalyapin, ˈfʲɵdər ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ ʂɐˈlʲapʲɪn}; April 12, 1938) was a Russian opera singer. Possessing a deep and expressive bass v ...

invited Rachmaninoff to live with him in Italy, where he sought his advice while studying the opera. During his stay, Rachmaninoff composed the love duet of his opera ''Francesca da Rimini

Francesca da Rimini or Francesca da Polenta (died between 1283 and 1286) was a medieval noblewoman of Ravenna, who was murdered by her husband, Giovanni Malatesta, upon his discovery of her affair with his brother, Paolo Malatesta. She was a co ...

'' and also began working on the second and third movements

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

of his Second Piano Concerto. With newfound enthusiasm for composition, he resumed working on them after returning to Russia, which for the rest of the summer and the autumn were being finished "quickly and easily", although the first movement caused him difficulties. He told his biographer Oscar von Riesemann that "the material grew in bulk, and new musical ideas began to stir within me—far more than I needed for my concerto". The two finished movements were to be performed in the Moscow Nobility Hall on at a concert arranged for the benefit of the Ladies' Charity Prison Committee. On the eve of the concert, Rachmaninoff caught a cold, prompting his friends and relatives to stuff him with remedies, filling him with an excess of mulled wine

Mulled wine, also known as spiced wine, is an alcoholic drink usually made with red wine, along with various mulling spices and sometimes raisins, served hot or warm. It is a traditional drink during winter, especially around Christmas. It is us ...

; he didn't want to admit his desire to cancel the performance. With him as soloist with an orchestra after an eight-year hiatus and his cousin Alexander Siloti making his conducting debut, it was an anxious event, but the concert was a great success, easing the worries of his close ones. Ivan Lipaev

Ivan Vasilievich Lipaev (russian: Иван Васильевич Липаев, 1865–1942) was a Russian music critic, composer, writer, social advocate, pedagogue, and trombonist active in both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. He played ...

wrote: "it's been long since the walls of the Nobility Hall reverberated with such enthusiastic, storming applause as on that evening ... This work contains much poetry, beauty, warmth, rich orchestration

Orchestration is the study or practice of writing music for an orchestra (or, more loosely, for any musical ensemble, such as a concert band) or of adapting music composed for another medium for an orchestra. Also called "instrumentation", orc ...

, healthy and buoyant creative power. Rachmaninoff's talent is evident throughout." The German company Gutheil Gutheil is a German surname of:

* Emil Arthur Gutheil (1889–1959), Polish-American psychiatrist

* (1868–1914), German conductor and composer, husband of Marie Gutheil-Schoder

* Marie Gutheil-Schoder (1874–1935), German soprano

* (born 1959 ...

published the concerto as opus number

In musicology, the opus number is the "work number" that is assigned to a musical composition, or to a set of compositions, to indicate the chronological order of the composer's production. Opus numbers are used to distinguish among compositio ...

18 the following year.

Before continuing composition, Rachmaninoff received financial aid from Siloti to tide him over for the next three years, securing his ability to compose without worrying about rent. By April 1901, while staying with Goldenweiser, he finished the first movement of the concerto and subsequently premiered the full work at a Moscow Philharmonic Society concert on , again with him at the piano and Siloti conducting. Five days before the premiere, however, Rachmaninoff received a letter from Nikita Morozov (his Conservatory colleague) pestering him regarding the structure of the concerto after receiving its score, commenting that the first subject seemed like an introduction to the second one. Frantic, he replied, writing that he concurred with his opinion and was pondering over the first movement. Regardless, it was an astounding success, and Rachmaninoff enjoyed wild acclaim. Even Cui, who previously scolded his First Symphony, displayed exuberance over the work in a letter from 1903. The piece established Rachmaninoff's fame as a concerto composer and is one of his most enduringly popular pieces. He dedicated it to Dahl for his treatment.

Subsequent performances

The popularity of the Second Piano Concerto grew rapidly, developing global fame after its subsequent performances. Its international progress started with a performance in Germany, where Siloti played it with theLeipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

The Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra (Gewandhausorchester; also previously known in German as the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig) is a German symphony orchestra based in Leipzig, Germany. The orchestra is named after the concert hall in which it is bas ...

under Arthur Nikisch

Arthur Nikisch (12 October 185523 January 1922) was a Hungarian conductor who performed internationally, holding posts in Boston, London, Leipzig and—most importantly—Berlin. He was considered an outstanding interpreter of the music of Br ...

's baton in January 1902. In March, the same duo had a tremendously successful performance in Saint Petersburg; two days preceding this, the Rachmaninoff-Siloti duo performed back in Moscow, with the former conducting and the latter as soloist. May of the same year saw a performance at the Queen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. From 1895 until 1941, it ...

in London, the soloist being Wassily Sapellnikoff

Wassily Sapellnikoff (russian: Василий Львович Сапельников; tr. ''Vasily Lvovich Sapelnikov'') (17 March 1941), was a Ukrainian-born Russian pianist.

Biography

Sapellnikoff was born in Odessa. He studied at the Odessa C ...

with the Philharmonic Society and Frederic Cowen

Sir Frederic Hymen Cowen (29 January 1852 – 6 October 1935), was an English composer, conductor and pianist.

Early years and musical education

Cowen was born Hymen Frederick Cohen at 90 Duke Street, Kingston, Jamaica, the fifth and last c ...

conducting; London would wait until 1908 for Rachmaninoff to perform it there. "One was quickly persuaded of its genuine excellence and originality", ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' wrote of the concerto following the performance. England, however, had already heard the work twice prior to the London premiere, with performances by Siloti in Birmingham and Manchester. Rachmaninoff—enhanced by success from repossessing the ability to compose again, coupled with no more financial worries—repaid the loan from Siloti within one year of receiving the last installment.

After marrying his first cousin Natalia Satina, the newly-wed Rachmaninoff received an invitation to play his concerto with the Vienna Philharmonic

The Vienna Philharmonic (VPO; german: Wiener Philharmoniker, links=no) is an orchestra that was founded in 1842 and is considered to be one of the finest in the world.

The Vienna Philharmonic is based at the Musikverein in Vienna, Austria. It ...

under the direction of Vasily Safonov

Vasily Ilyich Safonov (russian: Васи́лий Ильи́ч Сафо́нов, link=no, ; 6 February 185227 February 1918), also known as Wassily Safonoff, was a Russian pianist, teacher, conductor and composer.

Biography

Vasily Safonov, or S ...

in December. Although the engagement guaranteed him a hefty fee, he was anxious that accepting it would show ingratitude towards Siloti. However, after seeking his help, Taneyev reassured Rachmaninoff that this did not offend Siloti. That was followed by concerts in both Vienna and Prague the following spring in 1903 under the same engagement. In late 1904, Rachmaninoff won the Glinka Awards, cash prizes established in Belyayev's will, receiving 500 ruble

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

s for his concerto. Throughout his life, Rachmaninoff soloed the concerto a total of 145 times.

Early reception

After he fulfilled his 1908 London concert engagement at the Queen's Hall underSerge Koussevitzky

Sergei Alexandrovich KoussevitzkyKoussevitzky's original Russian forename is usually transliterated into English as either "Sergei" or "Sergey"; however, he himself adopted the French spelling "Serge", using it in his signature. (SeThe Koussevit ...

, a flattering review by ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' emerged: "The direct expression of the work, the extraordinary precision and exactitude of Rachmaninoff's playing, and even the strict economy of movement of arms and hands which he exercises, all contributed to the impression of completeness of performance."

His debut with an American orchestra occurred on 8 November 1909, performing the concerto at the

His debut with an American orchestra occurred on 8 November 1909, performing the concerto at the Philadelphia Academy of Music

The Academy of Music, also known as American Academy of Music, is a concert hall and opera house located at 240 S. Broad Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Its location is between Locust and Manning Streets in the Avenue of the Arts area of ...

with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Max Fiedler

Max Fiedler (21 December 1859, Zittau – 1 December 1939, Stockholm) was a German conductor and composer, born August Max Fiedler in Zittau, Saxony, Germany. He was especially noted as an interpreter of Brahms.

He first studied the piano ...

's baton, including repeat performances in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

and New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Critics since the first performance were chiefly dismissive, echoing Philip Hale

Philip Hale (March 5, 1854 in Norwich, Vermont – November 30, 1934 in Boston, Massachusetts) was an American music critic.

Hale attended Yale, where he served on the fourth editorial board of ''The Yale Record''. After graduating in 1876, ...

's program notes

A concert program is a selection and ordering, or programming, of pieces to be performed at an occasion, or concert. Programs may be influenced by the available ensemble of instruments, by performer ability or skill, by theme ( historical, progra ...

for the debut stating that "The concerto is of uneven worth. The first movement is labored and has little marked character. It might have been written by any German, technically well-trained, who was acquainted with the music of Tchaikovsky". Richard Aldrich, who was a music critic for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', murmured about the overperformance of the work in proportion to its worth, but complimented Rachmaninoff's playing, stating that, with the assistance of the orchestra, "he made it sound more interesting than it ever has before here". His last concert during the American tour was on 27 January 1910, performing the '' Isle of the Dead'' and his concerto under Modest Altschuler

Modest (Moisei Isaacovich) Altschuler (February 15, 1873September 12, 1963) was a cellist, orchestral conductor, and composer.Leonard Slatkin, ''Conducting Business: Unveiling the Mystery Behind the Maestro'' (2012), Amadeus Press, p. 32. . Acces ...

with his Russian Symphony Society, who farewelled the homesick Rachmaninoff with appraisal of his ''Isle of the Dead'' but dismissal of the concerto as "not in any way comparable to Rachmaninoff's third concerto". Rachmaninoff played the concerto eight times during the tour. Despite the concerto's popularity, its critical reception has often remained poor.

Following the 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

, Rachmaninoff and his family escaped Russia, never to return, seeing the US as a haven for remedying his financial situation; they arrived there one day before Armistice Day

Armistice Day, later known as Remembrance Day in the Commonwealth and Veterans Day in the United States, is commemorated every year on 11 November to mark Armistice of 11 November 1918, the armistice signed between the Allies of World War I a ...

, following their temporary stay in Scandinavia. Reginald De Koven

Henry Louis Reginald De Koven (April 3, 1859January 16, 1920) was an American music critic and prolific composer, particularly of comic operas.

Biography

De Koven was born in Middletown, Connecticut, and moved to Europe in 1870, where he receive ...

praised a Rachmaninoff concerto performance under Walter Damrosch

Walter Johannes Damrosch (January 30, 1862December 22, 1950) was a German-born American conductor and composer. He was the director of the New York Symphony Orchestra and conducted the world premiere performances of various works, including Ge ...

, writing that he rarely saw a New York audience "more moved, excited and wrought up". A 1927 ''Liverpool Post

The ''Liverpool Post'' was a newspaper published by Reach plc, Trinity Mirror in Liverpool, Merseyside, England. The newspaper and its website ceased publication on 19 December 2013.

Until 13 January 2012 it was a daily morning newspaper, wi ...

'' article called the concerto a "somewhat catchpenny work though it had plently of rather cheap glitter". His last role as a soloist for the concerto was on 18 June 1942 with Vladimir Bakaleinikov

Vladimir Romanovich Bakaleinikov, also Bakaleynikov and Bakaleinikoff (russian: Владимир Романович Бакалейников; 3 October 1885 in Moscow – 5 November 1953 in Pittsburgh) was a Russians, Russian-American Viola, violi ...

leading the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra

The Los Angeles Philharmonic, commonly referred to as the LA Phil, is an American orchestra based in Los Angeles, California. It has a regular season of concerts from October through June at the Walt Disney Concert Hall, and a summer season at th ...

, at the Hollywood Bowl

The Hollywood Bowl is an amphitheatre in the Hollywood Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. It was named one of the 10 best live music venues in America by ''Rolling Stone'' magazine in 2018.

The Hollywood Bowl is known for its distin ...

. Reviewing the performance in ''Los Angeles Evening Citizen News'', Richard D. Saunders opined that the work is of a "songful quality, imbued with haunting melodies all tinged with sombre pathos and expressed with the graceful refinement characteristic of the composer".

Modern reception and legacy

No other concerto by Rachmaninoff was as popular with audiences and pianists alike as his Second Concerto; the musicologist Glen Carruthers attributes this popularity with "memorable melodieshich

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

appear in each movement". Rachmaninoff's biographer Geoffrey Norris

Geoffrey Norris (born 1947) is an English musicologist and music critic. His scholarship focuses on Russian composers; in particularly, Norris is a leading scholar on the life and music of Sergei Rachmaninoff, about whom he has written in nume ...

characterized the concerto as "notable for its conciseness and for its lyrical themes, which are just sufficiently contrasted to ensure that they are not spoilt either by overabundance or overexposure." Stephen Hough

Sir Stephen Andrew Gill Hough (; born 22 November 1961) is a British-born classical pianist, composer and writer. He became an Australian citizen in 2005 and thus has dual nationality (his father was born in Australia in 1926).

Biography

Houg ...

on an article with ''The Guardian'' posits that the composition is "his most popular, most often performed and, arguably, the most perfect structurally. It sounds as if it wrote itself, so naturally does the music flow". Another article by John Ezard and David Ward calls it one of the "most often performed concertos in the repertoire. Its emergence - in each year so far of the new century - as the British classical listening public's favourite tune indicates Rachmaninov's position as perhaps the most popular mainstream composer of the last 70 years." In 2022, the piece was voted number two in the Classic FM annual "Hall of Fame" poll, and has consistently ranked in the top three.

Numerous films—such as William Dieterle

William Dieterle (July 15, 1893 – December 9, 1972) was a German-born actor and film director who emigrated to the United States in 1930 to leave a worsening political situation. He worked in Hollywood primarily as a director for much of his ...

's ''September Affair

''September Affair'' is a 1950 American romantic drama film directed by William Dieterle and starring Joan Fontaine, Joseph Cotten, and Jessica Tandy. It was produced by Hal B. Wallis.

Plot

Marianne "Manina" Stuart (Joan Fontaine), a prominent c ...

'' (1950), Charles Vidor

Charles Vidor (born Károly Vidor; July 27, 1900June 4, 1959) was a Hungarian film director. Among his film successes are ''The Bridge'' (1929), ''The Tuttles of Tahiti'' (1942), ''The Desperadoes'' (1943), ''Cover Girl'' (1944), '' Together A ...

's ''Rhapsody

Rhapsody may refer to:

* A work of epic poetry, or part of one, that is suitable for recitation at one time

** Rhapsode, a classical Greek professional performer of epic poetry

Computer software

* Rhapsody (online music service), an online m ...

'' (1954), and Billy Wilder

Billy Wilder (; ; born Samuel Wilder; June 22, 1906 – March 27, 2002) was an Austrian-American filmmaker. His career in Hollywood spanned five decades, and he is regarded as one of the most brilliant and versatile filmmakers of Classic Holl ...

's ''The Seven Year Itch

''The Seven Year Itch'' is a 1955 American romantic comedy film directed by Billy Wilder, from a screenplay he co-wrote with George Axelrod from the 1952 three-act play. The film stars Marilyn Monroe and Tom Ewell, who reprised his stage role. ...

'' (1955)—borrow themes from the concerto. David Lean

Sir David Lean (25 March 190816 April 1991) was an English film director, producer, screenwriter and editor. Widely considered one of the most important figures in British cinema, Lean directed the large-scale epics ''The Bridge on the River ...

's romantic drama ''Brief Encounter

''Brief Encounter'' is a 1945 British romantic drama film directed by David Lean from a screenplay by Noël Coward, based on his 1936 one-act play ''Still Life''.

Starring Celia Johnson, Trevor Howard, Stanley Holloway, and Joyce Carey, ...

'' (1945) utilizes the music widely in its soundtrack, and Frank Borzage

Frank Borzage (; April 23, 1894 – June 19, 1962) was an Academy Award-winning American film director and actor, known for directing '' 7th Heaven'' (1927), '' Street Angel'' (1928), '' Bad Girl'' (1931), '' A Farewell to Arms'' (1932), ''Man's ...

's ''I've Always Loved You

''I've Always Loved You'' is a 1946 American drama musical film produced and directed by Frank Borzage and written by Borden Chase. The film stars Philip Dorn, Catherine McLeod, William Carter, Maria Ouspenskaya, Felix Bressart and Elizabeth P ...

'' (1946) features it heavily; this has further popularized the work. The concerto has also inspired numerous songs, and is frequently used in figure skating

Figure skating is a sport in which individuals, pairs, or groups perform on figure skates on ice. It was the first winter sport to be included in the Olympic Games, when contested at the 1908 Olympics in London. The Olympic disciplines are me ...

programmes.

Instrumentation

The concerto is scored forpiano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keyboa ...

and orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families.

There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* bowed string instruments, such as the violin, viola, c ...

:

* Woodwinds

Woodwind instruments are a family of musical instruments within the greater category of wind instruments. Common examples include flute, clarinet, oboe, bassoon, and saxophone. There are two main types of woodwind instruments: flutes and reed ...

:

** 2 flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedless ...

s

** 2 oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

A ...

s

** 2 clarinet

The clarinet is a musical instrument in the woodwind family. The instrument has a nearly cylindrical bore and a flared bell, and uses a single reed to produce sound.

Clarinets comprise a family of instruments of differing sizes and pitches ...

s in B (only in the first movement) and A (only in the second and third movements)

** 2 bassoon

The bassoon is a woodwind instrument in the double reed family, which plays in the tenor and bass ranges. It is composed of six pieces, and is usually made of wood. It is known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, versatility, and virtuo ...

s

* Brass

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other with ...

:

** 4 horns Horns or The Horns may refer to:

* Plural of Horn (instrument), a group of musical instruments all with a horn-shaped bells

* The Horns (Colorado), a summit on Cheyenne Mountain

* ''Horns'' (novel), a dark fantasy novel written in 2010 by Joe Hill ...

in F

** 2 trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

s in B

** 3 trombone

The trombone (german: Posaune, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the Brass instrument, brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips cause the Standing wave, air column ...

s (2 tenor, 1 bass)

** tuba

The tuba (; ) is the lowest-pitched musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, the sound is produced by lip vibrationa buzzinto a mouthpiece. It first appeared in the mid-19th century, making it one of the ne ...

* Percussion

A percussion instrument is a musical instrument that is sounded by being struck or scraped by a beater including attached or enclosed beaters or rattles struck, scraped or rubbed by hand or struck against another similar instrument. Exc ...

:

** timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionall ...

** bass drum

The bass drum is a large drum that produces a note of low definite or indefinite pitch. The instrument is typically cylindrical, with the drum's diameter much greater than the drum's depth, with a struck head at both ends of the cylinder. Th ...

** cymbal

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs soun ...

s

* Strings

String or strings may refer to:

*String (structure), a long flexible structure made from threads twisted together, which is used to tie, bind, or hang other objects

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Strings'' (1991 film), a Canadian anim ...

:

** 1st violin

The violin, sometimes known as a ''fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone (string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in the family in regular ...

s

** 2nd violins

** viola

The viola ( , also , ) is a string instrument that is bow (music), bowed, plucked, or played with varying techniques. Slightly larger than a violin, it has a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of ...

s

** cello

The cello ( ; plural ''celli'' or ''cellos'') or violoncello ( ; ) is a Bow (music), bowed (sometimes pizzicato, plucked and occasionally col legno, hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually intonation (music), t ...

s

** double bass

The double bass (), also known simply as the bass () (or #Terminology, by other names), is the largest and lowest-pitched Bow (music), bowed (or plucked) string instrument in the modern orchestra, symphony orchestra (excluding unorthodox addit ...

es

Structure

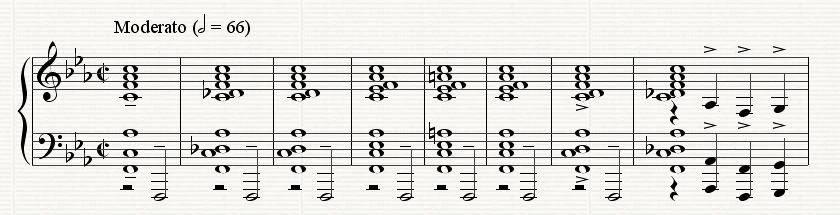

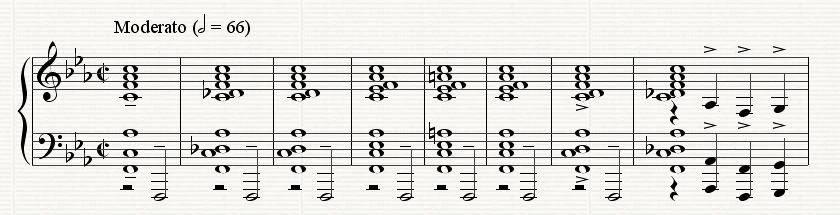

The piece is written in three-movement concerto form:I. Moderato

The opening

The opening movement

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

begins with a series of chromatic bell-like tollings on the piano that build tension, eventually climaxing in the introduction of the main theme

Theme or themes may refer to:

* Theme (arts), the unifying subject or idea of the type of visual work

* Theme (Byzantine district), an administrative district in the Byzantine Empire governed by a Strategos

* Theme (computing), a custom graphical ...

by the violins, violas, and first clarinet.

In this first section, while the melody is stated by the orchestra, the piano takes on the role of accompaniment, consisting of rapid oscillating arpeggios between both hands which contribute to the fullness and texture of the section's sound. The theme soon goes into a slightly lower register, where it is carried on by the cello section, and then is joined by the violins and violas, soaring to a climactic C note. After the statement of the long first theme, a quick and virtuosic "''piu mosso''" pianistic figuration transition leads into a short series of authentic cadences, accompanied by both a crescendo and an accelerando; this then progresses into the gentle, lyrical second theme in E major

E major (or the key of E) is a major scale based on E, consisting of the pitches E, F, G, A, B, C, and D. Its key signature has four sharps. Its relative minor is C-sharp minor and its parallel minor is E minor. Its enharmonic equivalent, ...

, the relative key

In music, relative keys are the major and minor scales that have the same key signatures ( enharmonically equivalent), meaning that they share all the same notes but are arranged in a different order of whole steps and half steps. A pair of major ...

. The second theme is first stated by the solo piano, with light accompaniment coming from the upper wind instruments. A transition which follows the chromatic scale eventually leads to the final reinstatement of the second theme, this time with the full orchestra at a piano dynamic. The exposition

Exposition (also the French for exhibition) may refer to:

*Universal exposition or World's Fair

*Expository writing

**Exposition (narrative)

*Exposition (music)

*Trade fair

* ''Exposition'' (album), the debut album by the band Wax on Radio

*Exposi ...

ends with an agitated closing section with scaling arpeggios on the E major scale in both hands.

The agitated and unstable development borrows motifs from both themes, changing keys very often and giving the melody to different instruments while a new musical idea is slowly formed. The sound here, while focused on a particular tonality, has ideas of chromaticism. Two sequences of pianistic figurations lead to a placid, orchestral reinstatement of the first theme in the dominant 7th key of G. The development furthers with motifs from the previous themes, climaxing towards a B major "''più vivo''" section. A triplet arpeggio section leads into the accelerando section, with the accompanying piano playing chords in both hands, and the string section providing the melody reminiscent of the second theme. The piece reaches a climax with the piano playing dissonant fortississimo () chords, and with the horns and trumpets providing the syncopated melody.

While the orchestra restates the first theme, the piano, that on the other occasion had an accompaniment role, now plays the march-like theme that had been halfly presented in the development, thus making a considerable readjustment in the exposition, as in the main theme, the arpeggios in the piano serve as an accompaniment. This is followed by a piano-solo which continues the first theme and leads into a descending chromatic passage to a pianississimo A major chord. Then the second theme is heard played with a horn solo. The entrance of the piano reverts the key back into C minor, with triplet passages played over a mysterious theme played by the orchestra. Briefly, the piece transitions to a C major glissando in the piano, and is placid until drawn into the agitated closing section in which the movement ends in a C minor ''fortissimo

In music, the dynamics of a piece is the variation in loudness between notes or phrases. Dynamics are indicated by specific musical notation, often in some detail. However, dynamics markings still require interpretation by the performer dependi ...

'', with the same authentic cadence as those that followed the first statement of the first theme in the exposition.

II. Adagio sostenuto

The second movement opens with a series of slow chords in the strings which modulate from theC minor

C minor is a minor scale based on C, consisting of the pitches C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. Its key signature consists of three flats. Its relative major is E major and its parallel major is C major.

The C natural minor scale is:

:

Cha ...

of the previous movement to the E major of this movement.

At the beginning of the A section, the piano enters, playing a simple arpeggiated

A broken chord is a chord broken into a sequence of notes. A broken chord may repeat some of the notes from the chord and span one or more octaves.

An arpeggio () is a type of broken chord, in which the notes that compose a chord are played ...

figure. This opening piano figure was composed in 1891 as the opening of the Romance from Two Pieces For Six Hands. The main theme is initially introduced by the flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedless ...

, before being developed by an extensive clarinet

The clarinet is a musical instrument in the woodwind family. The instrument has a nearly cylindrical bore and a flared bell, and uses a single reed to produce sound.

Clarinets comprise a family of instruments of differing sizes and pitches ...

solo. The motif is passed between the piano and then the strings.

Then the B section is heard. It builds up to a short climax centred on the piano, which leads to cadenza for piano.

The original theme is repeated, and the music appears to die away, finishing with just the soloist in E major.

III. Allegro scherzando

The last movement opens with a short orchestral introduction that modulates from E major (the key of the previous movement) to C minor, before a piano solo leads to the statement of the agitated first theme. After the original fast tempo and musical drama ends, a short transition from the piano solo leads to the second lyrical theme in B major is introduced by theoboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

A ...

and violas. This theme maintains the motif of the first movement's second theme. The exposition ends with a suspenseful closing section in B major.

After that an extended and energetic development section is heard. The development is based on the first theme of the exposition. It maintains a very improvisational quality, as instruments take turns playing the stormy motifs.

In the recapitulation, the first theme is truncated to only 8 bars on the tutti, because it was widely used in the development section. After the transition, the recapitulation's 2nd theme appears, this time in D major, half above the tonic. However, after the ominous closing section ends it then builds up into a triumphant climax in C major from the beginning of the coda. The movement ends very triumphantly in the tonic major with the same four-note rhythm ending the Third Concerto in D minor.

Recordings

Commercial recordings include: * 1929:Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one o ...

with Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra is an American symphony orchestra, based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. One of the " Big Five" American orchestras, the orchestra is based at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, where it performs its subscription ...

conducted by Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appeara ...

* 1959: Sviatoslav Richter

Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter, group= ( – August 1, 1997) was a Soviet classical pianist. He is frequently regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time, Great Pianists of the 20th Century and has been praised for the "depth of his int ...

with Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra

The Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra ( pl, Orkiestra Filharmonii Narodowej w Warszawie) is a Polish orchestra based in Warsaw. Founded in 1901, it is one of Poland's oldest musical institutions.

History

The orchestra was conceived on ...

conducted by Stanislaw Wislocki

* 1962: Van Cliburn

Harvey Lavan "Van" Cliburn Jr. (; July 12, 1934February 27, 2013) was an American pianist who, at the age of 23, achieved worldwide recognition when he won the inaugural International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958 during the Cold Wa ...

with Chicago Symphony Orchestra

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) was founded by Theodore Thomas in 1891. The ensemble makes its home at Orchestra Hall in Chicago and plays a summer season at the Ravinia Festival. The music director is Riccardo Muti, who began his tenure ...

conducted by Fritz Reiner

Frederick Martin "Fritz" Reiner (December 19, 1888 – November 15, 1963) was a prominent conductor of opera and symphonic music in the twentieth century. Hungarian born and trained, he emigrated to the United States in 1922, where he rose t ...

* 1965: Earl Wild

Earl Wild (November 26, 1915January 23, 2010) was an American pianist known for his transcriptions of jazz and classical music.

Biography

Royland Earl Wild was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1915. Wild was a musically precocious child and ...

with Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London, that performs and produces primarily classic works.

The RPO was established by Thomas Beecham in 1946. In its early days, the orchestra secured profitable ...

conducted by Jascha Horenstein

Jascha Horenstein (russian: Яша Горенштейн; – 2 April 1973) was an American conductor.

Biography

Horenstein was born in Kiev, Russian Empire (now Ukraine), into a well-to-do Jewish family; his mother (Marie Ettinger) came fr ...

* 1970: Alexis Weissenberg

Alexis Sigismund Weissenberg ( bg, Алексис Сигизмунд Вайсенберг; 26 July 1929 – 8 January 2012) was a Bulgarian-born French pianist.

Early life and career

Born into a Jewish family in Sofia, Weissenberg began taking ...

with Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

The Berlin Philharmonic (german: Berliner Philharmoniker, links=no, italic=no) is a German orchestra based in Berlin. It is one of the most popular, acclaimed and well-respected orchestras in the world.

History

The Berlin Philharmonic was fo ...

conducted by Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan (; born Heribert Ritter von Karajan; 5 April 1908 – 16 July 1989) was an Austrian conductor. He was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 34 years. During the Nazi era, he debuted at the Salzburg Festival, wit ...

* 1971: Vladimir Ashkenazy

Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazy (russian: Влади́мир Дави́дович Ашкена́зи, ''Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazi''; born 6 July 1937) is an internationally recognized solo pianist, chamber music performer, and conductor. He ...

with London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

conducted by André Previn

André George Previn (; born Andreas Ludwig Priwin; April 6, 1929 – February 28, 2019) was a German-American pianist, composer, and conductor. His career had three major genres: Hollywood films, jazz, and classical music. In each he achieved ...

* 1988: Evgeny Kissin

Evgeny Igorevich Kissin (russian: link=no, Евге́ний И́горевич Ки́син, translit=Evgénij Ígorevič Kísin, yi, link=no, יעווגעני קיסין, translit=Yevgeni Kisin; born 10 October 1971) is a Russian concert piani ...

with London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

conducted by Valery Gergiev

Valery Abisalovich Gergiev (russian: Вале́рий Абиса́лович Ге́ргиев, ; os, Гергиты Абисалы фырт Валери, Gergity Abisaly fyrt Valeri; born 2 May 1953) is a Russian conductor and opera company d ...

* 2005: Leif Ove Andsnes

Leif Ove Andsnes (; born 7 April 1970) is a Norwegian pianist and chamber musician. Andsnes has made several recordings for Virgin and EMI. In 2012, Leif Ove Andsnes has signed to Sony Classical, and recorded for the label the "Beethoven Journe ...

with Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

The Berlin Philharmonic (german: Berliner Philharmoniker, links=no, italic=no) is a German orchestra based in Berlin. It is one of the most popular, acclaimed and well-respected orchestras in the world.

History

The Berlin Philharmonic was fo ...

conducted by Antonio Pappano

Sir Antonio Pappano (born 30 December 1959) is an English-Italian conductor and pianist. He is currently music director of the Royal Opera House and of the Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. He is scheduled to become chief con ...

* 2011: Yuja Wang

Yuja Wang (; born February 10, 1987) is a Chinese classical pianist. She was born in Beijing, began studying piano there at age six, and went on to study at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing and the Curtis Institute of Music in Phila ...

with Verbier Festival Orchestra

The Verbier Festival is an annual international music festival that takes place for two weeks in late July and early August in the mountain resort of Verbier, Switzerland.

Founded by Swedish expatriate in 1994, it has attracted international s ...

conducted by Yuri Temirkanov

Yuri Khatuevich Temirkanov (russian: Ю́рий Хату́евич Темирка́нов; kbd, Темыркъан Хьэту и къуэ Юрий; born December 10, 1938) is a Russian conductor of Circassian ( Kabardian) origin.

Early life

...

* 2013: Anna Federova with Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie

The Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie (North West German Philharmonic) is a German orchestra, symphony orchestra based in Herford. It was founded in 1950 and, along with Philharmonie Südwestfalen and Landesjugendorchester NRW, is one of the 'official ...

conducted by Martin Panteleev

* 2017: Khatia Buniatishvili

Khatia Buniatishvili ( ka, ხატია ბუნიათიშვილი, ; born 21 June 1987) is a Georgian concert pianist.

Early life and education

Born in 1987 in Batumi, Georgia, Khatia Buniatishvili began studying piano under her ...

with the Czech Philharmonic

The Česká filharmonie (Czech Philharmonic) is a symphony orchestra based in Prague. The orchestra's principal concert venue is the Rudolfinum.

History

The name "Czech Philharmonic Orchestra" appeared for the first time in 1894, as the title ...

conducted by Paavo Järvi

Paavo Järvi (; born 30 December 1962) is an Estonian-American conductor.

Early life

Järvi was born in Tallinn, Estonia, to Liilia Järvi and the Estonian conductor Neeme Järvi. His siblings, Kristjan Järvi and Maarika Järvi, are also mu ...

* 2018: Daniil Trifonov

Daniil Olegovich Trifonov (russian: Дании́л Оле́гович Три́фонов; born 5 March 1991) is a Russian pianist and composer. Described by ''The Globe and Mail'' as "arguably today's leading classical virtuoso" and by ''The Tim ...

with Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra is an American symphony orchestra, based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. One of the " Big Five" American orchestras, the orchestra is based at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, where it performs its subscription ...

conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Yannick Nézet-Séguin, CC (; born Yannick Séguin;David Patrick Stearns, "Nezet-Seguin signs Philadelphia Orchestra contract". ''The Philadelphia Inquirer'', 19 June 2010. 6 March 1975) is a Canadian ( Québécois) conductor and pianist. He ...

Transcriptions and derivative works

In 1901, Gutheil published the concerto along with the composer's two piano arrangement. Austrian violinist and composer

In 1901, Gutheil published the concerto along with the composer's two piano arrangement. Austrian violinist and composer Fritz Kreisler

Friedrich "Fritz" Kreisler (February 2, 1875 – January 29, 1962) was an Austrian-born American violinist and composer. One of the most noted violin masters of his day, and regarded as one of the greatest violinists of all time, he was known ...

transcribed the second movement for violin and piano in 1940, named ''Preghiera'' (Prayer). In 1946, Percy Grainger

Percy Aldridge Grainger (born George Percy Grainger; 8 July 188220 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger and pianist who lived in the United States from 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. In the course of a long an ...

made a concert transcription of the third movement for piano solo. The Classical Jazz Quartet's 2006 arrangement uses thematic sections derived from each movement as grounds for jazz improvisation

Jazz improvisation is the spontaneous invention of melodic solo lines or accompaniment parts in a performance of jazz music. It is one of the defining elements of jazz. Improvisation is composing on the spot, when a singer or instrumentalist inv ...

.

Two songs recorded by Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Nicknamed the "Honorific nicknames in popular music, Chairman of the Board" and later called "Ol' Blue Eyes", Sinatra was one of the most popular ...

have roots in the concerto: "I Think of You", from the second theme of the first movement, and "Full Moon and Empty Arms

"Full Moon and Empty Arms" is a 1945 popular song by Buddy Kaye and Ted Mossman, based on Sergei Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 2.

The best-known recording of the song was made by Frank Sinatra in 1945 and reached No. 17 in the Billboard char ...

", from the second theme of the third movement. Eric Carmen

Eric Howard Carmen (born August 11, 1949) is an American singer, songwriter, guitarist, and keyboardist. He was first known as the lead vocalist of the Raspberries. He had numerous hit songs in the 1970s and 1980s, first as a member of the Rasp ...

's 1975 ballad "All by Myself

"All by Myself" is a song by American singer-songwriter Eric Carmen released in 1975. The verse is based on the second movement (''Adagio sostenuto'') of Sergei Rachmaninoff's circa 1900–1901 '' Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor'', Opus 18. The ...

" is based on the second movement.

Notes

References

Sources

Books and journals

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * (Score contains markings byLeonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein ( ; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first America ...

)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Other

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

* * {{Authority control Piano concerto 2 1901 compositions United States National Recording Registry recordings Compositions in C minor