Pelagornithidae on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Pelagornithidae, commonly called pelagornithids, pseudodontorns, bony-toothed birds, false-toothed birds or pseudotooth birds, are a

The biggest of the pseudotooth birds were the largest flying birds known. Almost all of their remains from the

The biggest of the pseudotooth birds were the largest flying birds known. Almost all of their remains from the  The legs were proportionally short, the feet probably webbed and the

The legs were proportionally short, the feet probably webbed and the

Unlike the true teeth of

Unlike the true teeth of  It is sometimes claimed that as with some other

It is sometimes claimed that as with some other  There is no obvious single reason for the pseudotooth birds' extinction. A scenario of general ecological change â exacerbated by the beginning ice age and changes in

There is no obvious single reason for the pseudotooth birds' extinction. A scenario of general ecological change â exacerbated by the beginning ice age and changes in  Irrespective of the cause of their ultimate extinction, during the long time of their existence the pseudotooth birds furnished

Irrespective of the cause of their ultimate extinction, during the long time of their existence the pseudotooth birds furnished

Nothing is known for sure about the colouration of these birds, as they left no living descendants. But some

Nothing is known for sure about the colouration of these birds, as they left no living descendants. But some

In 2005, a

In 2005, a

prehistoric

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The us ...

family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

of large seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same envir ...

s. Their fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

remains have been found all over the world in rocks dating between the Early Paleocene

The Danian is the oldest age or lowest stage of the Paleocene Epoch or Series, of the Paleogene Period or System, and of the Cenozoic Era or Erathem. The beginning of the Danian (and the end of the preceding Maastrichtian) is at the Cretaceousâ ...

and the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

boundary.

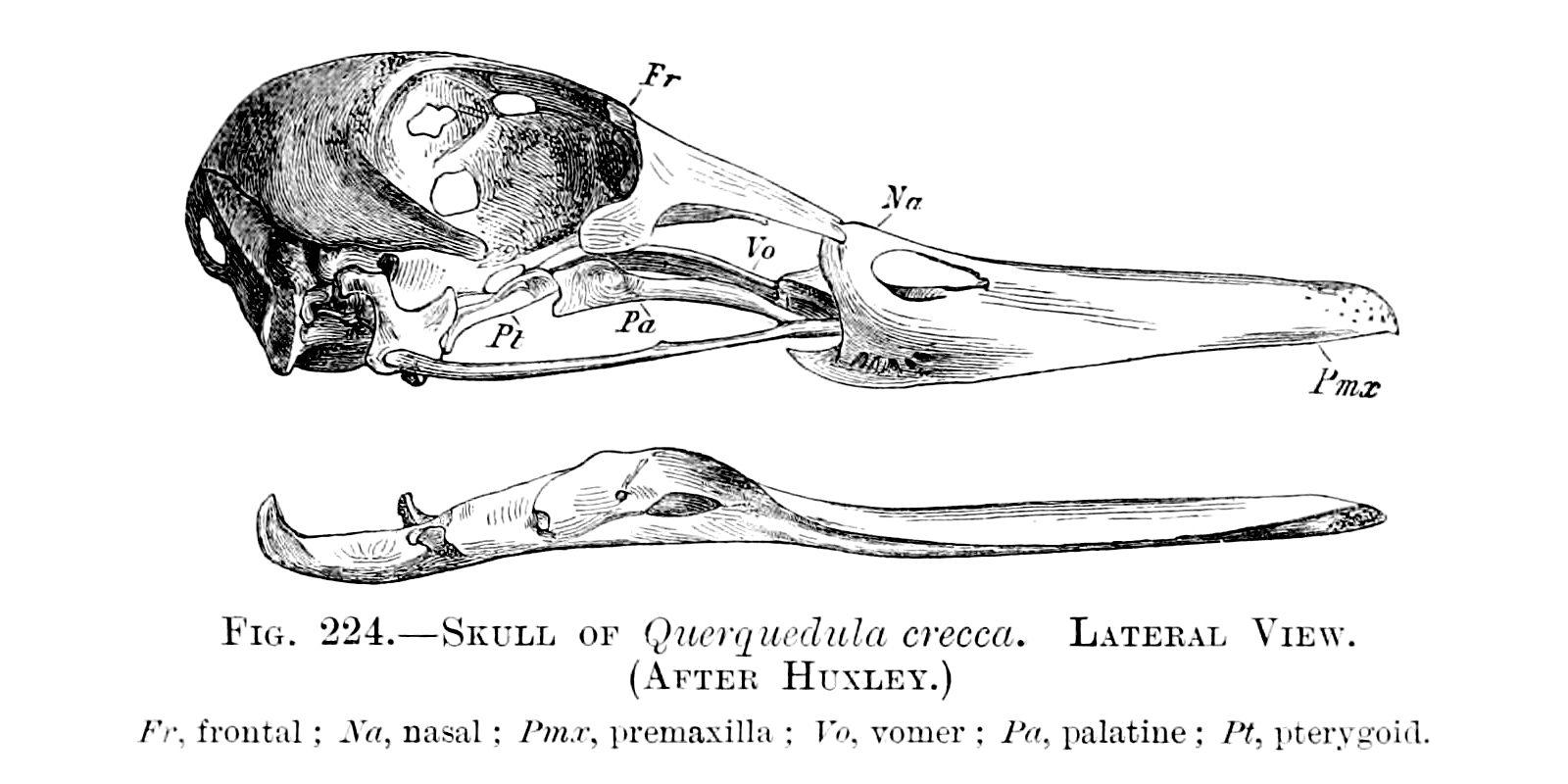

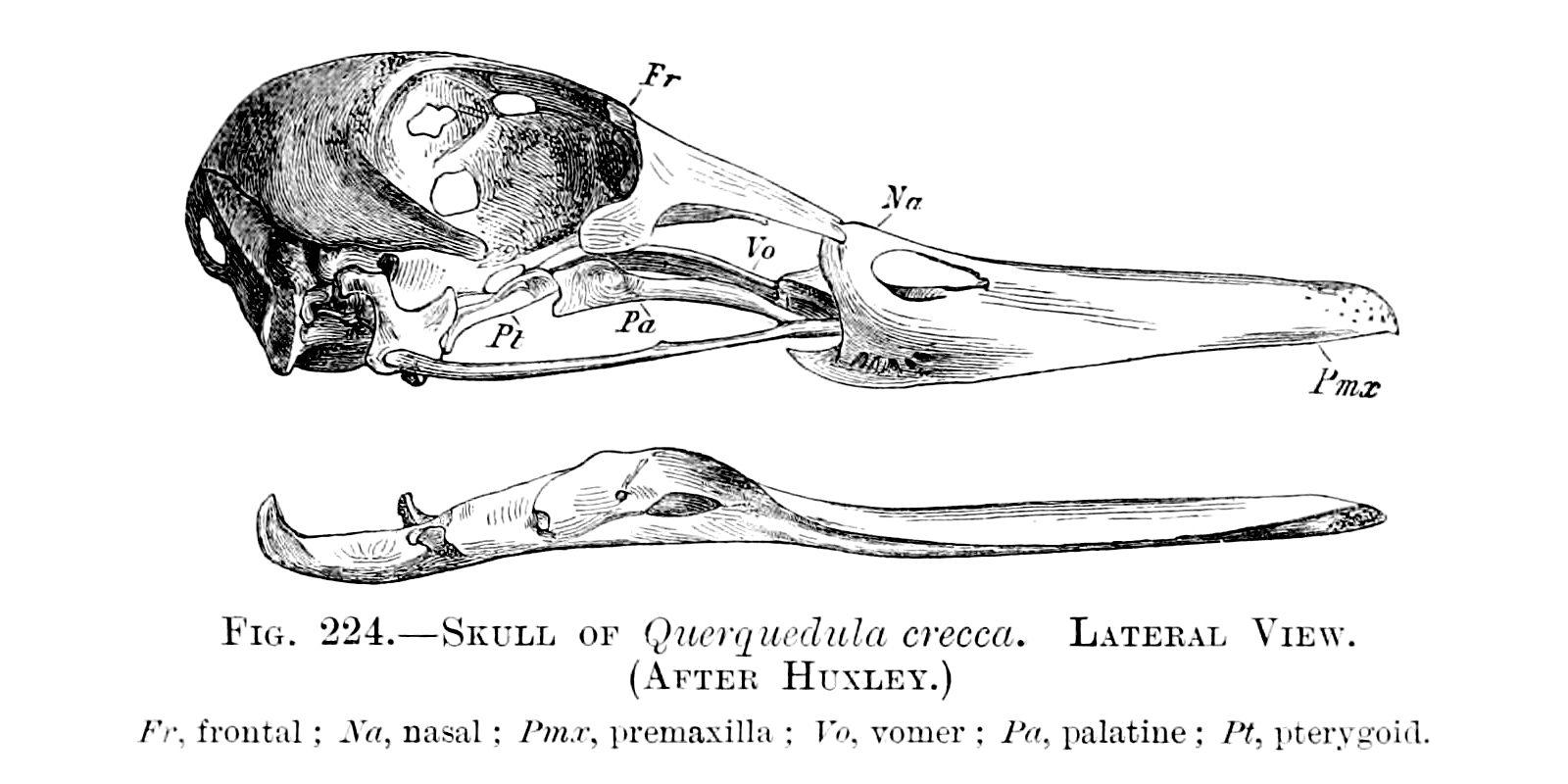

Most of the common names refer to these birds' most notable trait: tooth-like points on their beak's edges, which, unlike true teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, ...

, contained Volkmann's canals and were outgrowths of the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

ry and mandibular bones. Even "small" species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

of pseudotooth birds were the size of albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pac ...

es; the largest ones had wingspan

The wingspan (or just span) of a bird or an airplane is the distance from one wingtip to the other wingtip. For example, the Boeing 777â200 has a wingspan of , and a wandering albatross (''Diomedea exulans'') caught in 1965 had a wingspan o ...

s estimated at 5â6 metres (15â20 ft) and were among the largest flying birds ever to live. They were the dominant seabirds of most oceans throughout most of the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

, and modern human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, cultu ...

s apparently missed encountering them only by a tiny measure of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary time: the last known pelagornithids were contemporaries of ''Homo habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly ...

'' and the beginning of the history of technology

The history of technology is the history of the invention of tools and techniques and is one of the categories of world history. Technology can refer to methods ranging from as simple as stone tools to the complex genetic engineering and inf ...

.

Description and ecology

The biggest of the pseudotooth birds were the largest flying birds known. Almost all of their remains from the

The biggest of the pseudotooth birds were the largest flying birds known. Almost all of their remains from the Neogene

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

are immense, but in the Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or PalĂŠogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning o ...

there were a number of pelagornithids that were around the size of a great albatross (genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

''Diomedea'') or even a bit smaller. The undescribed species provisionally called "'' Odontoptila inexpectata''" â from the Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name is a combination of the Ancient Greek ''pala ...

-Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''Äáčs'', ...

boundary of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

â is the smallest pseudotooth bird discovered to date and was just a bit larger than a white-chinned petrel

The white-chinned petrel (''Procellaria aequinoctialis'') also known as the Cape hen and shoemaker, is a large shearwater in the family Procellariidae. It ranges around the Southern Ocean as far north as southern Australia, Peru and Namibia, and ...

(''Procellaria aequinoctialis'').

The Pelagornithidae had extremely thin-walled bones widely pneumatized with the air sac extensions of the lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either si ...

. Most limb bone fossils are very much crushed for that reason. In life, the thin bones and extensive pneumatization enabled the birds to achieve large size while remaining below critical wing loadings. Though 25 kg/m2 (5 lb/ft2) is regarded as the maximum wing loading for powered bird flight, there is evidence that bony-toothed birds used dynamic soaring

Dynamic soaring is a flying technique used to gain energy by repeatedly crossing the boundary between air masses of different velocity. Such zones of wind gradient are generally found close to obstacles and close to the surface, so the technique is ...

flight almost exclusively: the proximal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position ...

end of the humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a r ...

had an elongated diagonal shape that could hardly have allowed for the movement necessary for the typical flapping flight of birds; their weight thus cannot be easily estimated. The attachment positions for the muscles responsible for holding the upper arm straightly outstretched were particularly well-developed, and altogether the anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

seems to allow for an ability of holding the wings rigidly at the glenoid joint unmatched by any other known bird. This is especially prominent in the Neogene pelagornithids, and less developed in the older Paleogene forms. The sternum

The sternum or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels from injury. Sha ...

had the deep and short shape typical of dynamic soarers, and bony outgrowths at the keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

's forward margin securely anchored the furcula.

The legs were proportionally short, the feet probably webbed and the

The legs were proportionally short, the feet probably webbed and the hallux

Toes are the digits (fingers) of the foot of a tetrapod. Animal species such as cats that walk on their toes are described as being ''digitigrade''. Humans, and other animals that walk on the soles of their feet, are described as being ''plan ...

was vestigial or entirely absent; the tarsometatarsi (anklebones) resembled those of albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pac ...

es while the arrangement of the front toes was more like in fulmar

The fulmars are tubenosed seabirds of the family Procellariidae. The family consists of two extant species and two extinct fossil species from the Miocene.

Fulmars superficially resemble gulls, but are readily distinguished by their flight on ...

s. Typical for pseudotooth birds was a second toe that attached a bit kneewards from the others and was noticeably angled outwards. The "teeth" were probably covered by the rhamphotheca

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for food, ...

in life, and there are two furrows running along the underside of the upper bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Pla ...

just inside the ridges which bore the "teeth". Thus, when the bill was closed only the upper jaw's "teeth" were visible, with the lower ones hidden behind them. Inside the eye socket

In anatomy, the orbit is the cavity or socket of the skull in which the eye and its appendages are situated. "Orbit" can refer to the bony socket, or it can also be used to imply the contents. In the adult human, the volume of the orbit is , of ...

s of at least some pseudotooth birds â perhaps only in the younger species â were well-developed salt glands.

Altogether, almost no major body part of pelagornithids is known from a well-preserved associated fossil and most well-preserved material consists of single bones only; on the other hand the long occurrence and large size makes for a few rather comprehensive (though much crushed and distorted) remains of individual birds that were entombed by as they lay dead, complete with some fossilized feather

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and a premie ...

s. Large parts of the skull and some beak pieces are found not too infrequently. In February 2009, an almost-complete fossilized skull of a presumed '' Odontopteryx'' from around the Chasicoan-Huayquerian The Huayquerian ( es, Huayqueriense) age is a period of geologic time (9.0â6.8 Ma) within the Late Miocene epoch of the Neogene, used more specifically within the SALMA classification. It follows the Mayoan The Mayoan ( es, Mayoense) age is a ...

boundary c. 9 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago ...

(Ma) was unveiled in Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the ChillĂłn, RĂmac and LurĂn Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

. It had been found a few months earlier in Ocucaje District of Ica Province, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del PerĂș.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

. According to paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palĂŠontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

Mario Urbina, who discovered the specimen, and his colleagues Rodolfo Salas, Ken Campbell and Daniel T. Ksepka, the Ocucaje skull is the best-preserved pelagornithid cranium

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

known as of 2009.

Ecology and extinction

Unlike the true teeth of

Unlike the true teeth of Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

birds like ''Archaeopteryx

''Archaeopteryx'' (; ), sometimes referred to by its German name, "" ( ''Primeval Bird''), is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek (''archaīos''), meaning "ancient", and (''ptéryx''), meaning "feather" ...

'' or '' Aberratiodontus'', the pseudoteeth of the Pelagornithidae do not seem to have had serrated or otherwise specialized cutting edges, and were useful to hold prey for swallowing whole rather than to tear bits off it. Since the teeth were hollow or at best full of cancellous bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, and ...

and are easily worn or broken off in fossils, it is surmised they were not extremely resilient in life either. Pelagornithid prey would thus have been soft-bodied, and have encompassed mainly cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda ( Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head ...

s and soft-skinned fish

Fish are Aquatic animal, aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack Limb (anatomy), limbs with Digit (anatomy), digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and Chondrichthyes, cartilaginous and bony fish as we ...

es. Prey items may have reached considerable size. Though some reconstructions show pelagornithids as diving birds in the manner of gannet

Gannets are seabirds comprising the genus ''Morus'' in the family Sulidae, closely related to boobies.

Gannets are large white birds with yellowish heads; black-tipped wings; and long bills. Northern gannets are the largest seabirds in the ...

s, the thin-walled highly pneumatized bones

Skeletal pneumaticity is the presence of air spaces within bones. It is generally produced during development by excavation of bone by pneumatic diverticula (air sacs) from an air-filled space, such as the lungs or nasal cavity. Pneumatization is h ...

which must have fractured easily judging from the state of fossil specimens make such a mode of feeding unlikely, if not outright dangerous. Rather, prey would have been picked up from immediately below the ocean surface while the birds were flying or swimming, and they probably submerged only the beak in most situations. Their quadrate bone articulation with the lower jaw resembled that of a pelican or other birds that can open their beak widely. Altogether, the pseudotooth birds would have filled an ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

almost identical to that of the larger fish-eating pteranodontian pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 ...

s, whose extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

ion at the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

may well have paved the way for the highly successful 50-million-year reign of the Pelagornithidae. Like them as well as modern albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pac ...

es, the pseudotooth birds could have used the system of ocean current

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of sea water generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth conto ...

s and atmospheric circulation

Atmospheric circulation is the large-scale movement of air and together with ocean circulation is the means by which thermal energy is redistributed on the surface of the Earth. The Earth's atmospheric circulation varies from year to year, bu ...

to take round-track routes soaring over the open oceans, returning to breed only every few years. Unlike albatrosses today, which avoid the tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

equatorial currents with their doldrums, Pelagornithidae were found in all sorts of climates, and records from around 40 Ma stretch from Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

through Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: RĂ©publique togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

to the Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and othe ...

. It is conspicuous that penguin

Penguins (order Sphenisciformes , family Spheniscidae ) are a group of aquatic flightless birds. They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere: only one species, the GalĂĄpagos penguin, is found north of the Equator. Highly adap ...

s and plotopterids â both wing-propelled divers that foraged over the continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

â are almost invariably found in the company of pseudotooth birds. Thus, pseudotooth birds seem to have gathered in some numbers in upwelling

Upwelling is an physical oceanography, oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted ...

regions, presumably to feed but perhaps also to breed nearby.

It is sometimes claimed that as with some other

It is sometimes claimed that as with some other seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same envir ...

s (e.g. the flightless Plotopteridae), the evolutionary radiation of cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel th ...

ns and pinniped

Pinnipeds (pronounced ), commonly known as seals, are a widely distributed and diverse clade of carnivorous, fin-footed, semiaquatic, mostly marine mammals. They comprise the extant families Odobenidae (whose only living member is the ...

s outcompeted the pseudotooth birds and drove them into extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

ion. While this may be correct for the plotopterids, for pelagornithids it is not so likely for two reasons: First, the Pelagornithidae continued to thrive for 10 million years after modern-type baleen whale

Baleen whales ( systematic name Mysticeti), also known as whalebone whales, are a parvorder of carnivorous marine mammals of the infraorder Cetacea ( whales, dolphins and porpoises) which use keratinaceous baleen plates (or "whalebone") in t ...

s evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variati ...

, and in the Middle Miocene

The Middle Miocene is a sub-epoch of the Miocene Epoch made up of two stages: the Langhian and Serravallian stages. The Middle Miocene is preceded by the Early Miocene.

The sub-epoch lasted from 15.97 ± 0.05 Ma to 11.608 ± 0.005 Ma (million ...

''Pelagornis

''Pelagornis'' is a widespread genus of prehistoric pseudotooth birds. These were probably rather close relatives of either pelicans and storks, or of waterfowl, and are here placed in the order Odontopterygiformes to account for this uncertai ...

'' coexisted with '' Aglaocetus'' and Harrison's whale (''Eobalaenoptera harrisoni'') in the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

off the Eastern Seaboard, while the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

''Osteodontornis

''Osteodontornis'' is an extinct seabird genus. It contains a single named species, ''Osteodontornis orri'' (Orr's bony-toothed bird, in literal translation of its scientific name), which was described quite exactly one century after the first sp ...

'' inhabited the same seas as '' Balaenula'' and '' Morenocetus''; the ancestral smallish sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the sperm whale famil ...

genus '' Aulophyseter'' (and/or ''Orycterocetus

''Orycteocetus'' is an extinct genus of sperm whale from the Miocene of the northern Atlantic Ocean.

Classification

''Orycterocetus'' is a member of Physeteroidea closely related to crown-group sperm whales. The type species, ''O. quadratidens'' ...

'') occurred in both Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

oceans at that time, while the mid-sized sperm whale '' Brygmophyseter'' roamed the North Pacific. As regards Miocene pinnipeds, a diversity of ancient walrus

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in the fami ...

es and ancestral fur seal

Fur seals are any of nine species of pinnipeds belonging to the subfamily Arctocephalinae in the family '' Otariidae''. They are much more closely related to sea lions than true seals, and share with them external ears (pinnae), relatively l ...

s like ''Thalassoleon

''Thalassoleon'' ("sea lion"

) is an extinct genus of large fur seal. ''Thalassoleon'' inhabited the Northern Pacific Ocean in latest Miocene and early Pliocene. Fossils of ''T. mexicanus'' are known from Baja California and southern California. ...

'' inhabited the north-east, while the ancient leopard seal

The leopard seal (''Hydrurga leptonyx''), also referred to as the sea leopard, is the second largest species of seal in the Antarctic (after the southern elephant seal). Its only natural predator is the orca. It feeds on a wide range of prey incl ...

''Acrophoca

''Acrophoca longirostris'', sometimes called the swan-necked seal, is an extinct genus of Late Miocene pinniped. It was thought to have been the ancestor of the modern leopard seal, however it is now thought to be a species of monk seal.

Taxono ...

'' is a remarkable species known from the south-east Pacific. Secondly, pinnipeds are limited to near-shore waters while pseudotooth birds roamed the seas far and wide, like large cetaceans, and like all big carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other s ...

s all three groups were K-strategists with moderate to very low population densities

Population density (in agriculture: standing stock or plant density) is a measurement of population per unit land area. It is mostly applied to humans, but sometimes to other living organisms too. It is a key geographical term.Matt RosenberPo ...

.

Thus, direct competition for food between bony-toothed birds and cetaceans or pinnipeds cannot have been very severe. As both the birds and pinnipeds would need level ground near the sea to raise their young, competition for breeding grounds may have affected the birds' population. In that respect, the specializations for dynamic soaring restricted the number of possible nesting sites for the birds, but on the other hand upland on islands or in coastal ranges could have provided breeding grounds for Pelagornithidae that was inaccessible for pinnipeds; just as many albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pac ...

es today nest in the uplands of islands (e.g. the GalĂĄpagos or Torishima). The bony-toothed birds probably required strong updraft

In meteorology, an updraft is a small-scale current of rising air, often within a cloud.

Overview

Localized regions of warm or cool air will exhibit vertical movement. A mass of warm air will typically be less dense than the surrounding regi ...

s for takeoff and would have preferred higher sites anyway for this reason, rendering competition with pinniped rookeries

A rookery is a colony of breeding animals, generally gregarious birds.

Coming from the nesting habits of rooks, the term is used for corvids and the breeding grounds of colony-forming seabirds, marine mammals ( true seals and sea lions), and ...

quite minimal. As regards breeding grounds, giant eggshell fragments from the Famara Famara is the main mountainous massif in the north of the island of Lanzarote in the Canary Islands. It is the eastern slope of a volcano erupting in the Miocene. The cliffs of Famara (''Risco de Famara'') are the remains of a caldera of about te ...

mountains on Lanzarote

Lanzarote (, , ) is a Spanish island, the easternmost of the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean. It is located approximately off the north coast of Africa and from the Iberian Peninsula. Covering , Lanzarote is the fourth-largest of the i ...

, Canary Islands, were tentatively attributed to Late Miocene

The Late Miocene (also known as Upper Miocene) is a sub-epoch of the Miocene Epoch made up of two stages. The Tortonian and Messinian stages comprise the Late Miocene sub-epoch, which lasted from 11.63 Ma (million years ago) to 5.333 Ma.

The ...

pseudotooth birds. As regards the Ypresian

In the geologic timescale the Ypresian is the oldest age or lowest stratigraphic stage of the Eocene. It spans the time between , is preceded by the Thanetian Age (part of the Paleocene) and is followed by the Eocene Lutetian Age. The Ypresian ...

London Clay

The London Clay Formation is a marine geological formation of Ypresian (early Eocene Epoch, c. 56â49 million years ago) age which crops out in the southeast of England. The London Clay is well known for its fossil content. The fossils from ...

of the Isle of Sheppey

The Isle of Sheppey is an island off the northern coast of Kent, England, neighbouring the Thames Estuary, centred from central London. It has an area of . The island forms part of the local government district of Swale. ''Sheppey'' is deriv ...

, wherein pelagornithid fossils are not infrequently found, it was deposited in a shallow epicontinental sea

An inland sea (also known as an epeiric sea or an epicontinental sea) is a continental body of water which is very large and is either completely surrounded by dry land or connected to an ocean by a river, strait, or "arm of the sea". An inland se ...

during a very hot time with high sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardis ...

s. The presumed breeding sites cannot have been as far offshore as many seabird rookeries

A rookery is a colony of breeding animals, generally gregarious birds.

Coming from the nesting habits of rooks, the term is used for corvids and the breeding grounds of colony-forming seabirds, marine mammals ( true seals and sea lions), and ...

are today, as the region was hemmed in between the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

and the Grampian and Scandinavian Mountains

The Scandinavian Mountains or the Scandes is a mountain range that runs through the Scandinavian Peninsula. The western sides of the mountains drop precipitously into the North Sea and Norwegian Sea, forming the fjords of Norway, whereas to th ...

, in a sea less wide than the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la CaraĂŻbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De CaraĂŻben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

is today. Neogene pseudotooth birds are common along the America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

coasts near the Appalachian and Cordillera

A cordillera is an extensive chain and/or network system of mountain ranges, such as those in the west coast of the Americas. The term is borrowed from Spanish, where the word comes from , a diminutive of ('rope').

The term is most commonly us ...

n mountains, and these species thus presumably also bred not far offshore or even in the mountains themselves. In that respect the presence of medullary bone

The medullary cavity (''medulla'', innermost part) is the central cavity of bone shafts where red bone marrow and/or yellow bone marrow (adipose tissue) is stored; hence, the medullary cavity is also known as the marrow cavity.

Located in the ...

in the specimens from Lee Creek Mine

Lee may refer to:

Name

Given name

* Lee (given name), a given name in English

Surname

* Chinese surnames romanized as Li or Lee:

** Li (surname æ) or Lee (Hanzi ), a common Chinese surname

** Li (surname ć©) or Lee (Hanzi ), a Chinese ...

in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

, United States, is notable, as among birds this is generally only found in laying females, indicating that the breeding grounds were probably not far away. At least Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

islands of volcanic origin would be eroded away in the last millions of years however, obliterating any remains of pelagornithid breeding colonies that might have once existed in the open ocean. Necker Island for example was of significant size 10 million years ago, when ''Osteodontornis

''Osteodontornis'' is an extinct seabird genus. It contains a single named species, ''Osteodontornis orri'' (Orr's bony-toothed bird, in literal translation of its scientific name), which was described quite exactly one century after the first sp ...

'' roamed the Pacific.

There is no obvious single reason for the pseudotooth birds' extinction. A scenario of general ecological change â exacerbated by the beginning ice age and changes in

There is no obvious single reason for the pseudotooth birds' extinction. A scenario of general ecological change â exacerbated by the beginning ice age and changes in ocean current

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of sea water generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth conto ...

s due to plate tectonic

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, ÏΔÎșÏÎżÎœÎčÎșÏÏ, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large te ...

shifts (e.g. the emergence of the Antarctic circumpolar current

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is an ocean current that flows clockwise (as seen from the South Pole) from west to east around Antarctica. An alternative name for the ACC is the West Wind Drift. The ACC is the dominant circulation feat ...

or the closing of the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de PanamĂĄ), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

) â is more likely, with the pseudotooth birds as remnants of the world's Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or PalĂŠogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning o ...

fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is '' flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. ...

ultimately failing to adapt. In that respect it may be significant that some lineages of cetaceans, like the primitive dolphins of the Kentriodontidae or the shark-toothed whales, flourished contemporary with the Pelagornithidae and became extinct at about the same time. Also, the modern diversity of pinniped and cetacean genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

evolved largely around the Mio-Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

s emerged or became vacant. In addition, whatever caused the Middle Miocene disruption and the Messinian Salinity Crisis

The Messinian salinity crisis (MSC), also referred to as the Messinian event, and in its latest stage as the Lago Mare event, was a geological event during which the Mediterranean Sea went into a cycle of partial or nearly complete desiccation (d ...

did affect the trophic web of Earth's oceans not insignificantly either, and the latter event led to a widespread extinction of seabirds. Together, this combination of factors led to Neogene

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

animals finally replacing the last remnants of the Paleogene fauna in the Pliocene. In that respect, it is conspicuous that the older pseudotooth birds are typically found in the same deposits as plotopterids and penguin

Penguins (order Sphenisciformes , family Spheniscidae ) are a group of aquatic flightless birds. They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere: only one species, the GalĂĄpagos penguin, is found north of the Equator. Highly adap ...

s, while younger forms were sympatric

In biology, two related species or populations are considered sympatric when they exist in the same geographic area and thus frequently encounter one another. An initially interbreeding population that splits into two or more distinct species s ...

with auk

An auk or alcid is a bird of the family Alcidae in the order Charadriiformes. The alcid family includes the murres, guillemots, auklets, puffins, and murrelets. The word "auk" is derived from Icelandic ''ĂĄlka'', from Old Norse ''alka'' (a ...

s, albatrosses, penguins and Procellariidae â which, however, underwent an adaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic in ...

of considerable extent coincident (and probably caused by) with the final demise of the Paleogene-type trophic web. Although the fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

is necessarily incomplete, as it seems cormorant

Phalacrocoracidae is a family of approximately 40 species of aquatic birds commonly known as cormorants and shags. Several different classifications of the family have been proposed, but in 2021 the IOC adopted a consensus taxonomy of seven ge ...

s and seagull

Gulls, or colloquially seagulls, are seabirds of the family Laridae in the suborder Lari. They are most closely related to the terns and skimmers and only distantly related to auks, and even more distantly to waders. Until the 21st century, ...

s were very rarely found in association with the Pelagornithidae.

Irrespective of the cause of their ultimate extinction, during the long time of their existence the pseudotooth birds furnished

Irrespective of the cause of their ultimate extinction, during the long time of their existence the pseudotooth birds furnished prey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

for large predators themselves. Few if any birds that coexisted with them were large enough to harm them while airborne; as evidenced by the Early Eocene '' Limnofregata'', the frigatebird

Frigatebirds are a family of seabirds called Fregatidae which are found across all tropical and subtropical oceans. The five extant species are classified in a single genus, ''Fregata''. All have predominantly black plumage, long, deeply forke ...

s coevolved with the Pelagornithidae and may well have harassed any of the small species for food on occasion, as they today harass albatrosses. From the Middle Miocene or Early Pliocene of the Lee Creek Mine, some remains of pseudotooth birds which probably fell victim to shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

s while feeding are known. The large members of the abundant Lee Creek Mine shark fauna that hunted near the water's surface included the broadnose sevengill shark

The broadnose sevengill shark (''Notorynchus cepedianus'') is the only extant member of the genus ''Notorynchus'', in the family Hexanchidae. It is recognizable because of its seven gill slits, while most shark species have five gill slits, with ...

(''Notorynchus cepedianus''), ''Carcharias

''Carcharias'' is a genus of sand tiger sharks belonging to the family Odontaspididae. Once bearing many prehistoric species, all have gone extinct with the exception of the critically endangered sand tiger shark.

Description

''Carcharias'' ar ...

'' sand tiger sharks, ''Isurus'' and ''Cosmopolitodus'' mako shark

''Isurus'' is a genus of mackerel sharks in the family Lamnidae, commonly known as the mako sharks.

Description

The two living species are the common shortfin mako shark (''I. oxyrinchus'') and the rare longfin mako shark (''I. paucus''). The ...

s, '' Carcharodon'' white sharks, the snaggletooth shark

The snaggletooth shark, or fossil shark (''Hemipristis elongata''), is a species of weasel shark in the family Hemigaleidae, and the only extant member of the genus ''Hemipristis''. It is found in the Indo-West Pacific, including the Red Sea, fr ...

''Hemipristis serra'', tiger sharks (''Galeocerdo''), ''Carcharhinus

''Carcharhinus'' is the type genus of the family Carcharhinidae, the requiem sharks. One of 12 genera in its family, it contains over half of the species therein. It contains 35 extant and eight extinct species to date, with likely more species ...

'' whaler sharks, the lemon shark

The lemon shark (''Negaprion brevirostris'') is a species of shark from the family Carcharhinidae and is classified as a Vulnerable species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Lemon sharks can grow to in length. They are ...

(''Negaprion brevirostris'') and hammerhead shark

The hammerhead sharks are a group of sharks that form the family Sphyrnidae, so named for the unusual and distinctive structure of their heads, which are flattened and laterally extended into a "hammer" shape called a cephalofoil. Most hammerhe ...

s (''Sphyrna''), and perhaps (depending on the bird fossils' age) also '' Pristis'' sawfishes, '' Odontaspis'' sand tiger sharks, and ''Lamna

''Lamna'' is a genus of mackerel sharks in the family Lamnidae, containing two extant species: the porbeagle (''L. nasus'') of the North Atlantic and Southern Hemisphere, and the salmon shark (''L. ditropis'') of the North Pacific.

Endothermy

T ...

'' and '' Parotodus benedeni'' mackerel sharks. It is notable that fossils of smaller diving birds â for example auks, loon

Loons ( North American English) or divers ( British / Irish English) are a group of aquatic birds found in much of North America and northern Eurasia. All living species of loons are members of the genus ''Gavia'', family Gaviidae and order ...

s and cormorant

Phalacrocoracidae is a family of approximately 40 species of aquatic birds commonly known as cormorants and shags. Several different classifications of the family have been proposed, but in 2021 the IOC adopted a consensus taxonomy of seven ge ...

s â as well as those of albatrosses are much more commonly found in those shark pellets than pseudotooth birds, supporting the assumption that the latter had quite low population densities and caught much of their food in mid-flight.

A study on ''Pelagornis

''Pelagornis'' is a widespread genus of prehistoric pseudotooth birds. These were probably rather close relatives of either pelicans and storks, or of waterfowl, and are here placed in the order Odontopterygiformes to account for this uncertai ...

flight performance suggests that, unlike modern seabirds, it relied on thermal soaring much like continental soaring birds and ''Pteranodon

''Pteranodon'' (); from Ancient Greek (''pteron'', "wing") and (''anodon'', "toothless") is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with ''P. longiceps'' having a wingspan of . They lived during the late Cr ...

''.

External appearance

inference

Inferences are steps in reasoning, moving from premises to logical consequences; etymologically, the word ''wikt:infer, infer'' means to "carry forward". Inference is theoretically traditionally divided into deductive reasoning, deduction and in ...

s can be made based on their phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological s ...

: if they were a member of the "higher waterbird" group (see below), they most probably had a plumage similar to that depicted in the reconstruction of '' Osteodontornis orri'' â Procellariiformes

Procellariiformes is an order of seabirds that comprises four families: the albatrosses, the petrels and shearwaters, and two families of storm petrels. Formerly called Tubinares and still called tubenoses in English, procellariiforms are oft ...

and Pelecaniformes

The Pelecaniformes are an order of medium-sized and large waterbirds found worldwide. As traditionallyâbut erroneouslyâdefined, they encompass all birds that have feet with all four toes webbed. Hence, they were formerly also known by such n ...

in the modern sense (or Ciconiiformes

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family called Ciconiidae, and make up the order Ciconiiformes . Ciconiiformes previously included a number of other families, such as herons a ...

, if Pelecaniformes are merged there) have hardly any carotenoid

Carotenoids (), also called tetraterpenoids, are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, ...

or structural colors at all in their plumage

Plumage ( "feather") is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, ...

, and generally lack even phaeomelanins. Thus, the only colours commonly found in these birds are black, white and various shades of grey. Some have patches of iridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear to gradually change color as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Examples of iridescence include soap bubbles, feathers, butterfl ...

feathers, or brownish or reddish hues, but these are rare and limited in extent, and those species in which they are found (e.g. bittern

Bitterns are birds belonging to the subfamily Botaurinae of the heron family Ardeidae. Bitterns tend to be shorter-necked and more secretive than other members of the family. They were called ''hĂŠferblĂŠte'' in Old English; the word "bittern ...

s, ibis

The ibises () (collective plural ibis; classical plurals ibides and ibes) are a group of long-legged wading birds in the family Threskiornithidae, that inhabit wetlands, forests and plains. "Ibis" derives from the Latin and Ancient Greek word ...

es or the hammerkop) are generally only found in freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does incl ...

habitat.del Hoyo ''et al.'' (1992)

If the pseudotooth birds are Galloanseres, phaeomelanins might be more likely to have occurred in their feathers, but it is notable that the most basal lineages of Anseriformes

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which in ...

are typically grey-and-black or black-and-white. Among ocean-going birds in general, the upperside tends to be much darker than the underside (including the underwings) â though some petrel

Petrels are tube-nosed seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes.

Description

The common name does not indicate relationship beyond that point, as "petrels" occur in three of the four families within that group (all except the albatross f ...

s are dark grey all over, a combination of more or less dark grey upperside and white underside and (usually) head is a widespread colouration found in seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same envir ...

s and may either be plesiomorph

In phylogenetics, a plesiomorphy ("near form") and symplesiomorphy are synonyms for an ancestral character shared by all members of a clade, which does not distinguish the clade from other clades.

Plesiomorphy, symplesiomorphy, apomorphy, ...

ic for "higher waterbirds" or, perhaps more likely, be an adaptation

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the po ...

to provide camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

, in particular against being silhouetted against the sky if seen by prey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

in the sea. It is notable that at least the primary remiges

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tail ...

, and often the other flight feather

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tai ...

s too, are typically black in birds â even if the entire remaining plumage is completely white, as in some pelican

Pelicans (genus ''Pelecanus'') are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before ...

s or in the Bali starling

The Bali myna (''Leucopsar rothschildi''), also known as Rothschild's mynah, Bali starling, or Bali mynah, locally known as jalak Bali, is a medium-sized (up to long), stocky myna, almost wholly white with a long, drooping crest, and black tip ...

(''Leucopsar rothschildi''). This is due to the fact that melanin

Melanin (; from el, ÎŒÎλαÏ, melas, black, dark) is a broad term for a group of natural pigments found in most organisms. Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amino ...

s will polymer

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + '' -mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic a ...

ize, making all-black feathers very robust; as the largest force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can also be described intuitively as a ...

s encountered by bird feathers affect the flight feathers, the large amount of melanin gives them better resistance against being damaged in flight. In soaring birds as dependent on strong winds as the bony-toothed birds were, black wingtips and perhaps tails can be expected to have been present.

As regards the bare parts, all the presumed close relatives of the Pelagornithidae quite often have rather bright reddish colours, in particular on the bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Pla ...

. The phylogenetic uncertainties surrounding them do not allow to infer whether the bony-toothed birds had a throat sac similar to pelicans. If they did, it was probably red or orange, and may have been used in mating displays. Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

was probably almost nonexistent, as it typically is among the basal Anseriformes and the "higher waterbirds".

Taxonomy, systematics and evolution

The name "pseudodontorns" refers to thegenus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

'' Pseudodontornis'', which for some time served as the family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

's namesake. However, the presently used name Pelagornithidae pre-dates Pseudodontornithidae, and thus modern authors generally prefer "pelagornithids" over "pseudodontorns". The latter name is generally found in mid-20th-century literature however.

Historically, the disparate bones of the pseudotooth birds were spread across six groups: a number of genera described from leg bones was placed in a family Cyphornithidae, and considered close allies of the pelican

Pelicans (genus ''Pelecanus'') are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before ...

family ( Pelecanidae). They were united with the latter in a superfamily

SUPERFAMILY is a database and search platform of structural and functional annotation for all proteins and genomes. It classifies amino acid sequences into known structural domains, especially into SCOP superfamilies. Domains are functional, str ...

Pelecanides in suborder Pelecanae, or later on (after the endings of taxonomic rank

In biological classification, taxonomic rank is the relative level of a group of organisms (a taxon) in an ancestral or hereditary hierarchy. A common system consists of species, genus, family, order, class, phylum, kingdom, domain. While ...

s were fixed to today's standard) Pelecanoidea in suborder Pelecani. Subsequently, some allied them with the entirely spurious "family" " Cladornithidae" in a "pelecaniform" suborder " Cladornithes". Those genera known from skull material were typically assigned to one or two families ( Odontopterygidae and sometimes also Pseudodontornithidae) in a "pelecaniform" suborder Odontopteryges or Odontopterygia. ''Pelagornis

''Pelagornis'' is a widespread genus of prehistoric pseudotooth birds. These were probably rather close relatives of either pelicans and storks, or of waterfowl, and are here placed in the order Odontopterygiformes to account for this uncertai ...

'' meanwhile, described from wing bones, was traditionally placed in a monotypic

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unispe ...

"pelecaniform" family Pelagornithidae. This was often assigned either to the gannet

Gannets are seabirds comprising the genus ''Morus'' in the family Sulidae, closely related to boobies.

Gannets are large white birds with yellowish heads; black-tipped wings; and long bills. Northern gannets are the largest seabirds in the ...

and cormorant

Phalacrocoracidae is a family of approximately 40 species of aquatic birds commonly known as cormorants and shags. Several different classifications of the family have been proposed, but in 2021 the IOC adopted a consensus taxonomy of seven ge ...

suborder Sulae

The order Suliformes (, dubbed "Phalacrocoraciformes" by ''Christidis & Boles 2008'') is an order recognised by the International Ornithologist's Union. In regard to the recent evidence that the traditional Pelecaniformes is polyphyletic, it has ...

(which was formerly treated as superfamily Sulides in suborder Pelecanae), or to the Odontopterygia. The sternum

The sternum or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels from injury. Sha ...

of ''Gigantornis

''Gigantornis eaglesomei'' is a very large prehistoric bird described from a fragmentary specimen from the Eocene of Nigeria. It was originally described as a representative of the albatross family, Diomedeidae, but was later referred to the ps ...

'' was placed in the albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pac ...

family (Diomedeidae) in the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

of tube-nosed seabirds (Procellariiformes).

The most extensive taxonomic and systematic confusion affected '' Dasornis''. That genus was established based on a huge skull piece, which for long was placed in the Gastornithidae merely due to its size. ''Argillornis'' â nowadays recognized to belong in ''Dasornis'' â was described from wing bones, and generally included in the Sulae as part of the " Elopterygidae" â yet another invalid "family", and its type genus

In biological taxonomy, the type genus is the genus which defines a biological family and the root of the family name.

Zoological nomenclature

According to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, "The name-bearing type of a nominal ...

is generally not considered a modern-type bird by current authors. Some additional tarsometatarsus

The tarsometatarsus is a bone that is only found in the lower leg of birds and some non-avian dinosaurs. It is formed from the fusion of several bones found in other types of animals, and homologous to the mammalian tarsus (ankle bones) and me ...

(ankle) bone fragments were placed in the genus ''Neptuniavis'' and assigned to the Procellariidae in the Procellariiformes. All these remains were only shown to belong in the pseudotooth bird genus ''Dasornis'' in 2008.

The most basal known pelagornithid is '' Protodontopteryx''.G. Mayr, V. L. De Pietri, L. Love, A. Mannering, and R. P. Scofield. 2019. Oldest, smallest and phylogenetically most basal pelagornithid, from the early Paleocene of New Zealand, sheds light on the evolutionary history of the largest flying birds. Papers in Palaeontology

Systematics and phylogeny

Thesystematics

Biological systematics is the study of the diversification of living forms, both past and present, and the relationships among living things through time. Relationships are visualized as evolutionary trees (synonyms: cladograms, phylogenetic t ...

of bony-toothed birds are subject of considerable debate. Initially, they were allied with the (then-paraphyletic

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In ...

) "Pelecaniformes

The Pelecaniformes are an order of medium-sized and large waterbirds found worldwide. As traditionallyâbut erroneouslyâdefined, they encompass all birds that have feet with all four toes webbed. Hence, they were formerly also known by such n ...

" (pelican

Pelicans (genus ''Pelecanus'') are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before ...

s and presumed allies, such as gannet

Gannets are seabirds comprising the genus ''Morus'' in the family Sulidae, closely related to boobies.

Gannets are large white birds with yellowish heads; black-tipped wings; and long bills. Northern gannets are the largest seabirds in the ...

s and frigatebird

Frigatebirds are a family of seabirds called Fregatidae which are found across all tropical and subtropical oceans. The five extant species are classified in a single genus, ''Fregata''. All have predominantly black plumage, long, deeply forke ...

s) and the Procellariiformes

Procellariiformes is an order of seabirds that comprises four families: the albatrosses, the petrels and shearwaters, and two families of storm petrels. Formerly called Tubinares and still called tubenoses in English, procellariiforms are oft ...

(tube-nosed seabirds like albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pac ...

es and petrel

Petrels are tube-nosed seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes.

Description

The common name does not indicate relationship beyond that point, as "petrels" occur in three of the four families within that group (all except the albatross f ...

s), because of their similar general anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

. Some of the first remains of the massive '' Dasornis'' were mistaken for a ratite

A ratite () is any of a diverse group of flightless, large, long-necked, and long-legged birds of the infraclass Palaeognathae. Kiwi, the exception, are much smaller and shorter-legged and are the only nocturnal extant ratites.

The systematics ...

and later a gastornithid. They were even used to argue for a close relationship between these two groups â and indeed, the pelicans and tubenoses, as well as for example the other "Pelecaniformes" (cormorant

Phalacrocoracidae is a family of approximately 40 species of aquatic birds commonly known as cormorants and shags. Several different classifications of the family have been proposed, but in 2021 the IOC adopted a consensus taxonomy of seven ge ...

s and allies) which are preferably separated as Phalacrocoraciformes

The order Suliformes (, dubbed "Phalacrocoraciformes" by ''Christidis & Boles 2008'') is an order recognised by the International Ornithologist's Union. In regard to the recent evidence that the traditional Pelecaniformes is polyphyletic, it ha ...

nowadays, the Ciconiiformes

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family called Ciconiidae, and make up the order Ciconiiformes . Ciconiiformes previously included a number of other families, such as herons a ...

(storks and/or either heron

The herons are long-legged, long-necked, freshwater and coastal birds in the family Ardeidae, with 72 recognised species, some of which are referred to as egrets or bitterns rather than herons. Members of the genera ''Botaurus'' and ''Ixobrychu ...

s and ibis

The ibises () (collective plural ibis; classical plurals ibides and ibes) are a group of long-legged wading birds in the family Threskiornithidae, that inhabit wetlands, forests and plains. "Ibis" derives from the Latin and Ancient Greek word ...

es or the "core" Pelecaniformes) and Gaviiformes

Gaviiformes is an order of aquatic birds containing the loons or divers and their closest extinct relatives. Modern gaviiformes are found in many parts of North America and northern Eurasia (Europe, Asia and debatably Africa), though prehistoric ...

(loons/divers) seem to make up a radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

, possibly a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic â that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants â on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

, of "higher waterbirds". However, the Pelagornithidae are not generally held to be a missing link between pelicans and albatrosses anymore, but if anything much closer to the former and only convergent to the latter in ecomorphology.

In 2005, a

In 2005, a cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

analysis proposed a close relationship between pseudotooth birds and waterfowl

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which ...

(Anseriformes). These are not part of the "higher waterbirds" but of the Galloanserae, a basal lineage of neognath birds. Some features, mainly of the skull, support this hypothesis. For example, the pelagornithids lack a crest on the underside of the palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones () are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal species, located above the uvula in the throat. Together with the maxillae, they comprise the hard palate. (''Palate'' is derived from the Latin ...

, while the Neoaves

Neoaves is a clade that consists of all modern birds (Neornithes or Aves) with the exception of Paleognathae (ratites and kin) and Galloanserae (ducks, chickens and kin). Almost 95% of the roughly 10,000 known species of extant birds belong to ...

â the sister clade

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

of the Galloanserae which includes the "higher waterbirds" and the "higher landbirds" â have such a crest. Also, like ducks, geese and swans pelagornithids only have two and not three condyles

A condyle (;Entry "condyle"

in

mandibular process of the quadrate bone, with the middle condyle beakwards of the side condyle. Their basipterygoid articulation is similar to that of the Galloanseres. At the side of the

at

Electronic supplement

* (2006): L'avifaune du PaléogÚne des phosphates du Maroc et du Togo: diversité, systématique et apports à la connaissance de la diversification des oiseaux modernes (Neornithes) Paleogene avifauna of phosphates of Morocco and Togo: diversity, systematics and contributions to the knowledge of the diversification of the Neornithes" Doctoral thesis,

* * * (2002): El registro de Pelagornithidae del PacĂfico sudeste he record of Pelagornithidae in the southeast Pacific ''Actas del Congreso Latinoamericano de PaleontologĂa de Vertebrados'' 1: 26.

* (2007): El registro de Pelagornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) y la Avifauna NeĂłgena del PacĂfico Sudeste he record of Pelagornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) and the Neogene avifauna of the southeast Pacific ''Bulletin de l'Institut Français dâĂtudes Andines'' 36(2): 175â197 panish with French and English abstractsbr>PDF fulltext

* (2008): ''Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds''. CSIRO Publishing, CollingwoodVictoria, Australia. * (1992): ''

* * * * * (2009): ''Paleogene Fossil Birds''. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg & New York. Preview

at

PDF fulltext

* (2002): ''Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: Europe''. Ninox Press, Prague. PDF fulltext

!-- This should be treated with extreme caution as regards merging of species. Splits are usually good though. See also critical review in Auk121:623-627 here http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3793/is_200404/ai_n9396879 --> * (2003): Early Miocene birds of Djebel Zelten, Libya. ''Äasopis NĂĄrodnĂho muzea, Ćada pĆĂrodovÄdnĂĄ (J. Nat. Mus., Nat. Hist. Ser.)'' 172: 114â120

PDF fulltext

* (2009): Evolution of the Cenozoic marine avifaunas of Europe. ''Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums Wien A'' 111: 357â37

PDF fulltext

* (1985): The Fossil Record of Birds. ''In:'' : ''Avian Biology'' 8: 79â252

PDF fulltext

* (2001): Miocene and Pliocene Birds from the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina. ''In:'' : Geology and Paleontology of the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina III. ''Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology'' 90: 233â307

PDF fulltext

* * * (PD) 009br>Taxonomic name search form