Paterson Clarence Hughes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Paterson Clarence Hughes, DFC (19 September 1917 – 7 September 1940) was an Australian

Paterson Clarence Hughes was born in Numeralla, near

Paterson Clarence Hughes was born in Numeralla, near

On 3 September, Hughes' promotion to

On 3 September, Hughes' promotion to

National Archives of Australia: Personal File

* ttp://www.battleofbritain1940.net/0037.html Battle of Britain Historical Society: Saturday, September 7th 1940 {{DEFAULTSORT:Hughes, Pat 1917 births 1940 deaths Australian military personnel killed in World War II Royal Air Force personnel killed in World War II Australian World War II flying aces People from Cooma Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) Royal Air Force officers Royal Australian Air Force officers The Few Royal Air Force pilots of World War II

fighter ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ace is varied, but is usually co ...

of World War II. Serving with the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF), he was credited with as many as seventeen aerial victories during the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

, before being killed in action on 7 September 1940. His tally made him the highest-scoring Australian of the battle, and among the three highest-scoring Australians of the war.

Born in Cooma

Cooma is a town in the south of New South Wales, Australia. It is located south of the national capital, Canberra, via the Monaro Highway. It is also on the Snowy Mountains Highway, connecting Bega with the Riverina.

At the , Cooma had a po ...

, New South Wales, Hughes joined the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

as a cadet in 1936. After graduating as a pilot, he chose to take a commission with the RAF. In July 1937, he was assigned to No. 64 Squadron, which operated Hawker Demon

The Hawker Hart is a British two-seater biplane light bomber aircraft that saw service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was designed during the 1920s by Sydney Camm and manufactured by Hawker Aircraft. The Hart was a prominent British aircra ...

and, later, Bristol Blenheim

The Bristol Blenheim is a British light bomber aircraft designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company (Bristol) which was used extensively in the first two years of the Second World War, with examples still being used as trainers until ...

fighters. Posted to No. 234 Squadron following the outbreak of World War II, Hughes began flying Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

s as a flight commander. He shared in his unit's first aerial victory on 8 July 1940, and began scoring heavily against the ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' the following month. Known for his practice of attacking his targets at extremely close range, Hughes is generally thought to have died after his Spitfire was struck by flying debris from a German bomber that he had just shot down. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, and was buried in England.

Early life

Cooma

Cooma is a town in the south of New South Wales, Australia. It is located south of the national capital, Canberra, via the Monaro Highway. It is also on the Snowy Mountains Highway, connecting Bega with the Riverina.

At the , Cooma had a po ...

, New South Wales, on 19 September 1917. He was the second-youngest of twelve children, the last of four boys in his family.Alexander, ''Australia's Few'', pp. 30–31 Hughes' father was a teacher by profession but at the time of Pat's birth was running the community post office; christened Percival Clarence Hughes, and known as Percy, he had apparently adopted the name Paterson by the time of his marriage to Catherine Vennell in 1895. Percy was also a writer, contributing to newspapers and magazines such as '' The Bulletin'', and "Paterson" may have been homage to the poet Banjo Paterson

Andrew Barton "Banjo" Paterson, (17 February 18645 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author. He wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing particularly on the rural and outback areas, including the ...

. In any case, Pat shared his father's interest in literature. He also grew to love the landscape of the local Monaro district in the shadow of the Snowy Mountains

The Snowy Mountains, known informally as "The Snowies", is an IBRA subregion in southern New South Wales, Australia, and is the tallest mountain range in mainland Australia, being part of the continent's Great Dividing Range cordillera system ...

, which he described as "unrivalled in the magnificence and grandeur of its beauty".

Hughes was educated at Cooma Public School until age twelve, when the family moved to Haberfield in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

; his father was by then working as a labourer.Newton, ''Australian Air Aces'', pp. 91–92 He attended Petersham Boys' School, becoming a prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

in 1932 and vice captain the following year. As well as playing sport, he was a keen aircraft modeller and built crystal radio

A crystal radio receiver, also called a crystal set, is a simple radio receiver, popular in the early days of radio. It uses only the power of the received radio signal to produce sound, needing no external power. It is named for its most impo ...

sets.Claasen, ''Dogfight'', p. 141 Having attained his intermediate certificate, Hughes entered Fort Street High School

Fort Street High School (FSHS) is a Education in Australia#Government schools, government-funded Mixed-sex school, co-educational Selective school (New South Wales), academically selective secondary school, secondary day school, located in Petersh ...

in February 1934. He left after eight months to take up employment at Saunders' Jewellers in George Street, Sydney

George Street is a street in the central business district of Sydney.

It was Sydney's original high street, and remains one of the busiest streets in the city centre. It connects a number of the city's most important buildings and precincts. ...

, and enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

(RAAF) on 20 January 1936.Garrisson, ''Australian Fighter Aces'', p. 140 Hughes had also applied to, and been accepted by, the Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister of ...

, but chose the RAAF.

Training as an air cadet at RAAF Point Cook

RAAF Williams is a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) military air base set across two locations, at Point Cook and Laverton, located approximately south-west of the Melbourne central business district in Victoria, Australia. Both establishm ...

near Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, Hughes learnt to fly in de Havilland Moth

The de Havilland Moths were a series of light aircraft, sports planes, and military trainers designed by Geoffrey de Havilland. In the late 1920s and 1930s, they were the most common civilian aircraft flying in Britain, and during that time ever ...

s before progressing to Westland Wapiti

The Westland Wapiti was a British two-seat general-purpose military single-engined biplane of the 1920s. It was designed and built by Westland Aircraft Works to replace the Airco DH.9A in Royal Air Force service.

First flying in 1927, the Wa ...

s in the middle of the year. A practical joker who bridled under RAAF discipline, his euphoria during his first solo on 11 March 1936 was such that he "went mad, whistled, sang and almost jumped for joy". A fellow cadet recalled that Hughes "loved life and lived it at high pressure". Upon graduation in December 1936, Hughes was assessed as having "no outstanding qualities" despite being "energetic and keen". Under a pre-war arrangement between the British and Australian governments, he volunteered for transfer to the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF), and sailed for the United Kingdom in January 1937.Stephens, ''The Royal Australian Air Force'', pp. 84–85 His decision to transfer had not been quick or easy; though keen to "try and do something special" in England, and intrigued by "a fascinating picture of easy life, beer and women" that had been presented to him, in the end he felt that it was simply "willed" that he should go.

Early RAF service

On 20 March 1937, Hughes was granted a five-year short-service commission as apilot officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off officially in the RAF; in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly P/O in all services, and still often used in the RAF) is the lowest commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many other Commonwealth countri ...

in the RAF. Like some of his compatriots, he refused to exchange his dark-blue RAAF uniform for the lighter-coloured RAF one. He undertook advanced flying instruction at No. 2 Flying Training School in Digby, Lincolnshire. Slated to fly bombers, he appealed and in July was posted as a fighter pilot to No. 64 Squadron, which operated Hawker Demon

The Hawker Hart is a British two-seater biplane light bomber aircraft that saw service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was designed during the 1920s by Sydney Camm and manufactured by Hawker Aircraft. The Hart was a prominent British aircra ...

s out of RAF Martlesham Heath

Royal Air Force Martlesham Heath or more simply RAF Martlesham Heath is a former Royal Air Force station located southwest of Woodbridge, Suffolk, England. It was active between 1917 and 1963, and played an important role in the development of ...

, Suffolk. The squadron was transferred to RAF Church Fenton

Royal Air Force Church Fenton or RAF Church Fenton was a former Royal Air Force (RAF) station located south east of Tadcaster, North Yorkshire, England and north west of Selby, North Yorkshire, near the village of Church Fenton. The station wa ...

, Yorkshire, in May 1938. Hughes was promoted to flying officer on 19 November. No. 64 Squadron subsequently received Bristol Blenheim 1F twin-engined fighters, and completed its conversion to the type in January 1939.

Hughes was promoted to acting flight lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior commissioned rank in air forces that use the Royal Air Force (RAF) system of ranks, especially in Commonwealth countries. It has a NATO rank code of OF-2. Flight lieutenant is abbreviated as Flt Lt in the India ...

in November 1939 and became a flight commander in the newly formed No. 234 Squadron, which, like No. 64 Squadron, came under the control of No. 13 Group in the north of England. On establishment the previous month at RAF Leconfield

Royal Air Force Leconfield or more simply RAF Leconfield is a former Royal Air Force station located in Leconfield (near Beverley), East Riding of Yorkshire, England.

The site is now used by the MoD Defence School of Transport Leconfield or D ...

, East Yorkshire, No. 234 Squadron was equipped with Blenheims, Fairey Battle

The Fairey Battle is a British single-engine light bomber that was designed and manufactured by the Fairey Aviation Company. It was developed during the mid-1930s for the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a monoplane successor to the Hawker Hart and Hi ...

s and Gloster Gauntlet

The Gloster Gauntlet was a single-seat biplane fighter designed and produced by the British aeroplane manufacturer Gloster Aircraft in the 1930s. It was the last fighter to be operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF) to have an open cockpit, and ...

s; it began re-arming with Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

s in March 1940 and was operational two months later. The commanding officer, Squadron Leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr in the RAF ; SQNLDR in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly sometimes S/L in all services) is a commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence. It is also ...

Richard Barnett, rarely flew, and Hughes assumed responsibility for overseeing conversion to the Spitfire.Bungay, ''The Most Dangerous Enemy'', pp. 1–2 "More experienced and more mature" than his fellow pilots, according to historian Stephen Bungay

Stephen Francis Bungay (born 2 September 1954) is a British management consultant, historian and author, who currently serves as Director of the Ashridge Strategic Management Centre at Hult International Business School.

Biography

Bungay read Mo ...

, the Australian "effectively led" No. 234 Squadron. By this time, Hughes had acquired a young Airedale Terrier

The Airedale Terrier (often shortened to "Airedale"), also called Bingley Terrier and Waterside Terrier, is a dog breed of the terrier type that originated in the valley (''dale'') of the River Aire, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England. It ...

known as Flying Officer Butch, who sometimes flew with him—against regulations. He had also met and begun dating Kathleen ("Kay") Brodrick of Hull. On 19 June, Hughes and his squadron transferred to RAF St Eval

Royal Air Force St. Eval or RAF St. Eval was a Royal Air Force station for the RAF Coastal Command, southwest of Padstow in Cornwall, England, UK. St Eval's primary role was to provide anti-submarine and anti-shipping patrols off the south wes ...

, Cornwall, under the jurisdiction of the newly formed No. 10 Group in south-west England.

Battle of Britain

As theBattle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

got under way in July 1940, Hughes shared in No. 234 Squadron's first confirmed aerial victories. He and his section of two other Spitfires shot down a German Junkers Ju 88

The Junkers Ju 88 is a Nazi Germany, German World War II ''Luftwaffe'' twin-engined multirole combat aircraft. Junkers, Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works (JFM) designed the plane in the mid-1930s as a so-called ''Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") th ...

attacking convoys near Lands End

Land's End ( kw, Penn an Wlas or ''Pedn an Wlas'') is a headland and tourist and holiday complex in western Cornwall, England, on the Penwith peninsula about west-south-west of Penzance at the western end of the A30 road. To the east of it is ...

on 8 July, and another south-east of Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

during a dawn patrol on 28 July. A shared claim for a Ju 88 on 27 July could not be confirmed as destroyed; after a chase over the water at heights as low as , the German escaped, despite being struck in the engines and cockpit, and was credited to the section as "damaged".Alexander, ''Australia's Few'', pp. 178–179 German records, made available post-war, confirm that a Junkers 88A, piloted by Leutnant Ruckdeschel, was lost on this day. On 1 August, Hughes was seconded from No. 234 Squadron to help set up the only Gloster Gladiator

The Gloster Gladiator is a British biplane fighter. It was used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) (as the Sea Gladiator variant) and was exported to a number of other air forces during the late 1930s.

Developed private ...

-equipped unit to operate during the Battle of Britain, No. 247 (China British) Squadron in Plymouth. The same day, he married Kay Brodrick, who likened him to Errol Flynn

Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn (20 June 1909 – 14 October 1959) was an Australian-American actor who achieved worldwide fame during the Golden Age of Hollywood. He was known for his romantic swashbuckler roles, frequent partnerships with Olivia ...

, in the register office

A register office or The General Register Office, much more commonly but erroneously registry office (except in official use), is a British government office where births, deaths, marriages, civil partnership, stillbirths and adoptions in England, ...

at Bodmin

Bodmin () is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated south-west of Bodmin Moor.

The extent of the civil parish corresponds fairly closely to that of the town so is mostly urban in character. It is bordere ...

, Cornwall.Bungay, ''The Most Dangerous Enemy'', p. 310 Apart from Flying Officer Butch, the witnesses were strangers; Kay arrived alone, and no-one from No. 234 Squadron could attend. Barnett was transferred out of No. 234 Squadron on 13 August, and Hughes took temporary command until the arrival of Squadron Leader Joe "Spike" O'Brien four days later. By now the fighting was intensifying over southern England, and the squadron relocated from St Eval to RAF Middle Wallop

Middle Wallop is a village in the civil parish of Nether Wallop in Hampshire, England, on the A343 road. At the 2011 Census the population was included in the civil parish of Over Wallop. The village has a public house, The George Inn, and a pet ...

, Hampshire, on 14 August.Price, ''Spitfire Mk.I/II Aces'', p. 66 Almost immediately after Hughes landed the ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' bombed the airfield; several ground staff and civilian workers were killed, but No. 234 Squadron's Spitfires escaped damage.

It was following No. 234 Squadron's move to Middle Wallop that Hughes began to score heavily against German fighters. On 15 August, in one of the costliest engagements of the Battle of Britain, known thereafter to the ''Luftwaffe'' as "Black Thursday", Hughes claimed victories (one of them shared) over two Messerschmitt Bf 110

The Messerschmitt Bf 110, often known unofficially as the Me 110,Because it was built before ''Bayerische Flugzeugwerke'' became Messerschmitt AG in July 1938, the Bf 110 was never officially given the designation Me 110. is a twin-engine (Des ...

s. He again achieved dual success on 16, 18 and 26 August, all six victims being Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the ''Luftwaffe's'' fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War ...

s brought down in the vicinity of the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

. Whereas in July he had fired at his targets from a range of , it was now his habit to close to , approximately three Spitfire lengths, before delivering his final burst; he also made head-on attacks against enemy aircraft. He had a narrow escape on the 16th after his second victory of the day, when he chased a quartet of Junkers Ju 87s and had his tailplane

A tailplane, also known as a horizontal stabiliser, is a small lifting surface located on the tail (empennage) behind the main lifting surfaces of a fixed-wing aircraft as well as other non-fixed-wing aircraft such as helicopters and gyroplane ...

shot up from behind by another Bf 109; he dived and forced the German to overshoot, then broke off having exhausted his ammunition firing at his former attacker. In the pub with Kay and his squadron mates that evening, Hughes jokingly told his wife, "In case of accidents make sure you marry again."

On 3 September, Hughes' promotion to

On 3 September, Hughes' promotion to substantive

A noun () is a word that generally functions as the name of a specific object or set of objects, such as living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, or ideas.Example nouns for:

* Living creatures (including people, alive, d ...

flight lieutenant was promulgated in ''The London Gazette

''The London Gazette'' is one of the official journals of record or government gazettes of the Government of the United Kingdom, and the most important among such official journals in the United Kingdom, in which certain statutory notices are ...

''. He claimed three Me 110s in the space of fifteen minutes south of Haslemere

The town of Haslemere () and the villages of Shottermill and Grayswood are in south west Surrey, England, around south west of London. Together with the settlements of Hindhead and Beacon Hill, they comprise the civil parish of Haslemere i ...

on 4 September, two Bf 109s while patrolling Kenley

Kenley is an area within the London Borough of Croydon. Prior to its incorporation into Greater London in 1965 it was in the historic county of Surrey. It is situated south of Purley, east of Coulsdon, north of Caterham and Whyteleafe and we ...

the following day, and a Bf 109 destroyed plus one probable near Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

on 6 September; he had to break off combat with the last-mentioned when its tanks ruptured, covering Hughes' canopy in oil. One of his victims on 5 September may have been Oberleutnant Franz von Werra

Franz Xaver Baron von Werra (13 July 1914 – 25 October 1941) was a German World War II fighter pilot and flying ace who was shot down over Britain and captured. He was the only Axis prisoner of war to escape from Canadian custody and return ...

, who was captured and subsequently became famous as " the one that got away". Hughes and his protégé, Bob Doe

Robert Francis Thomas Doe, (10 March 1920 – 21 February 2010) was a British fighter pilot and flying ace of the Second World War. He flew with the Royal Air Force during the Battle of Britain, and was seconded to the Indian Air Force during t ...

, claimed half of No. 234 Squadron's victories between mid-August and early September.

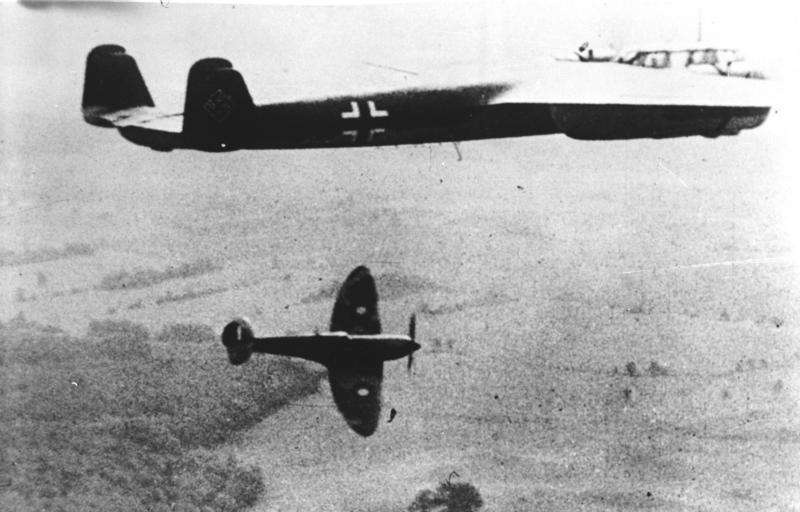

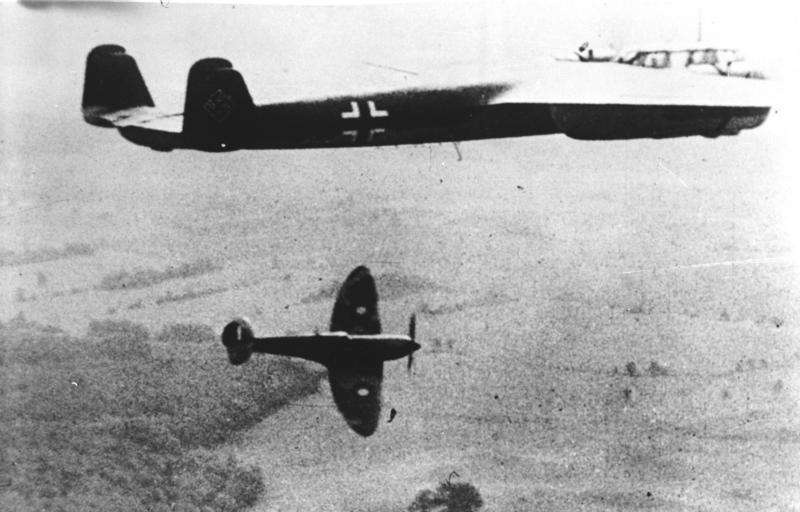

Hughes was killed in action on the evening of 7 September 1940, after he intercepted a Dornier Do 17 bomber taking part in a large-scale attack on London. His Spitfire crashed in a field between Sundridge and Bessels Green

Bessels Green is a village now incorporated into the built-up area of Sevenoaks in Kent, England. It is on the north-western outskirts of Sevenoaks, in the parish of Chevening. At the 2011 Census the village population was included in the civil ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. He apparently bailed out, but his parachute failed to open; his body was found in a garden on Main Road, Sundridge, not far from the wreck of his Spitfire. The Dornier came down in the River Darent

The Darent is a Kentish tributary of the River Thames and takes the waters of the River Cray as a tributary in the tidal portion of the Darent near Crayford, as illustrated by the adjacent photograph, snapped at high tide. 'Darenth' is frequen ...

. No. 234 Squadron lost its commanding officer, O'Brien, in the same action.Bishop, ''Battle of Britain'', p. 305 Mystery surrounds exactly how Hughes came to grief, though his close-in tactics are believed to have played a major part in it. The strain of regular combat without respite, manifesting itself in fatigue and spots before the eyes, may also have contributed. He is generally thought to have collided with flying wreckage from the crippled German bomber, rendering his Spitfire uncontrollable. It is also possible that Hughes accidentally rammed his target. Further speculation suggested that he was the victim of friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while eng ...

from another British fighter attacking the same Dornier, or was struck by German bullets from a Bf 109.Bungay, ''The Most Dangerous Enemy'', p. 472 Some observers on the ground, including collier Charles Hall, maintained that Hughes rammed the Dornier on purpose. Four days after his death, No. 234 Squadron was moved back to the relative quiet of Cornwall.Alexander, ''Australia's Few'', p. 265

Legacy

The top-scoring Australianflying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ace is varied, but is usually co ...

of the Battle of Britain and one of fourteen Australian fighter pilots killed during the battle, Hughes has been described as "the inspiration and driving force behind No. 234 Squadron RAF". He is generally credited with seventeen confirmed victories—fourteen solo and three shared. This tally puts him among the top ten Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

Battle of Britain aces.Alexander, ''Australia's Few'', p. 263 It also ranks him among the three highest-scoring Australians of World War II, after Clive Caldwell

Clive Robertson Caldwell, (28 July 1911 – 5 August 1994) was the leading Australian air ace of World War II. He is officially credited with shooting down 28.5 enemy aircraft in over 300 operational sorties, including an ace in a day. In addit ...

with thirty victories (twenty-seven solo and three shared) and Adrian Goldsmith with seventeen (sixteen solo and one shared).

A war widow after barely five weeks of marriage, Kay Hughes was inconsolable in her loss: "I wept until I could cry no more." Flying Officer Butch ran out of the mess

The mess (also called a mess deck aboard ships) is a designated area where military personnel socialize, eat and (in some cases) live. The term is also used to indicate the groups of military personnel who belong to separate messes, such as the o ...

on the day of his master's death, and was never seen again.Alexander, ''Australia's Few'', pp. 264–265 Following a service at St James', Sutton-on-Hull

Sutton-on-Hull (also known as Sutton-in-Holderness) is a suburb of the city of Kingston upon Hull, in the ceremonial county of the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It is located north east of the city centre and has the B1237 road running t ...

, on 13 September 1940, Hughes was buried in the churchyard at Row G, Grave 4. A week later, Kay discovered she was pregnant, but eventually miscarried. She subsequently drove ambulances for the British war effort. News of his son's marriage came as "a complete surprise" to Percy Hughes, who only learned of his daughter-in-law's existence from the Australian Air Board's casualty letter. Having married three more times after Hughes' death, Kay died on 28 June 1983 and, in accordance with her wishes, her ashes were buried with her first husband, whose headstone was amended to read "In loving memory of his wife Kathleen."

Hughes was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) on 22 October 1940 for his "skill and determination" as a flight commander and "gallantry in his attacks on the enemy"; Squadron Leader O'Brien had recommended the decoration a week before their deaths. Kay was presented with the medal at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

on 23 June 1942. In Australia, Hughes is commemorated at Christ's Church, Kiama

Kiama () is a coastal town 120 kilometres south of Sydney in the Illawarra. One of the main tourist attractions is the Kiama Blowhole. Kiama features several popular surfing beaches and caravan parks, and numerous alfresco cafes and restaurants ...

, with a memorial tablet placed by his sister Muriel. A special memorial is dedicated to him at Monaghan Hayes Place, Cooma. His name appears on the Battle of Britain Roll of Honour in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, and on supplementary panel 12 in the Commemorative Area of the Australian War Memorial

The Australian War Memorial is Australia's national memorial to the members of its armed forces and supporting organisations who have died or participated in wars involving the Commonwealth of Australia and some conflicts involving pe ...

(AWM), Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

. The AWM also holds his DFC and service medals in its collection. Kay had given the medals to her sisters-in-law to pass on to Percy in the 1950s and, after being lost during an Anzac Day

, image = Dawn service gnangarra 03.jpg

, caption = Anzac Day Dawn Service at Kings Park, Western Australia, 25 April 2009, 94th anniversary.

, observedby = Australia Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Cook Islands New ...

parade in the 1960s, they went through several family members' hands before turning up in the safe of the Kiama Country Women's Association

The Country Women's Association (CWA) is the largest regional and rural advocacy group in Australia. It comprises seven independent State and Territory Associations, who are passionate advocates for country women and their families, working ...

; they were donated to the AWM in 1990. On 7 September 2005, Charles Hall's sons dedicated a plaque in Hughes' honour at the house where he fell in Main Road, Sundridge; Bob Doe attended, expressing his thanks for "an Australian who came to help us when we needed him". Shoreham Aircraft Museum

The Shoreham Aircraft Museum is located in the village of Shoreham near Sevenoaks in Kent, England, on the south-east edge of Greater London. It was founded by volunteers in 1978 and is dedicated to the airmen who fought in the skies over sout ...

in Kent unveiled a memorial stone to Hughes at Sundridge on 23 August 2008. On 15 September 2014, the AWM's daily Last Post Ceremony was dedicated to Hughes' memory.

Combat record

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

National Archives of Australia: Personal File

* ttp://www.battleofbritain1940.net/0037.html Battle of Britain Historical Society: Saturday, September 7th 1940 {{DEFAULTSORT:Hughes, Pat 1917 births 1940 deaths Australian military personnel killed in World War II Royal Air Force personnel killed in World War II Australian World War II flying aces People from Cooma Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) Royal Air Force officers Royal Australian Air Force officers The Few Royal Air Force pilots of World War II