Pandit Ravi Shankar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

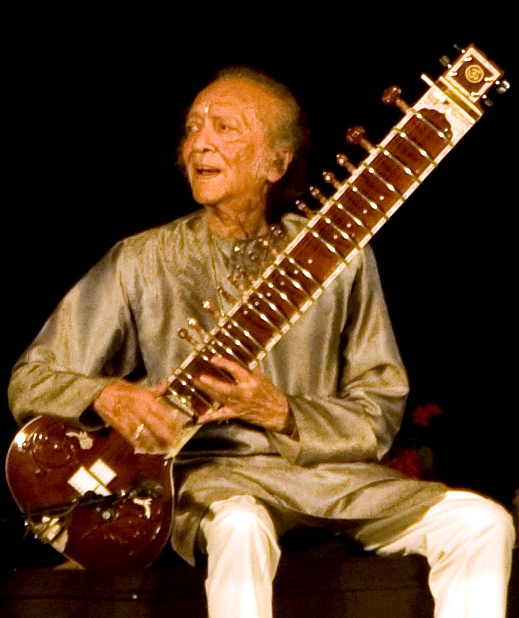

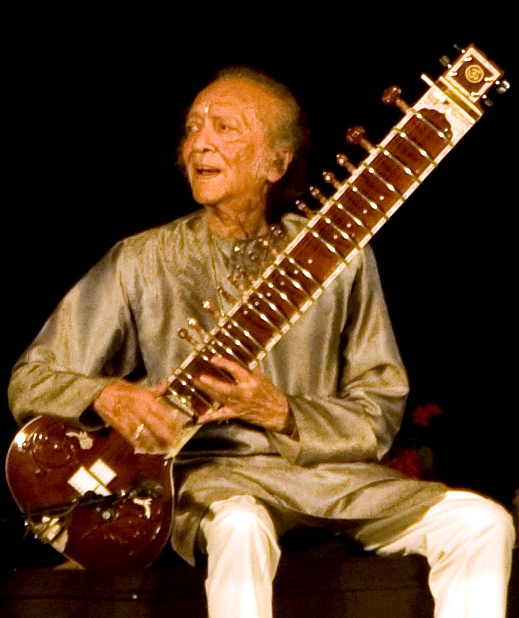

Ravi Shankar (; born Robindro Shaunkor Chowdhury, sometimes spelled as Rabindra Shankar Chowdhury; 7 April 1920 – 11 December 2012) was an Indian

Shankar's parents had died by the time he returned from the Europe tour, and touring the West had become difficult because of political conflicts that would lead to

Shankar's parents had died by the time he returned from the Europe tour, and touring the West had become difficult because of political conflicts that would lead to

Because of the positive response to Shankar's 1996 career compilation ''

Because of the positive response to Shankar's 1996 career compilation ''

Beatles guitarist

Beatles guitarist

, ''New York Times'', 12 December 2012 The influence even extended to blues musicians such as Mike Bloomfield, Michael Bloomfield, who created a raga-influenced improvisation number, "East-West" (Bloomfield scholars have cited its working title as "The Raga" when Bloomfield and his collaborator Nick Gravenites began to develop the idea) for the Butterfield Blues Band in 1966. Harrison met Shankar in London in June 1966 and visited India later that year for six weeks to study ''sitar'' under Shankar in Srinagar. During the visit, a documentary film about Shankar named ''Raga (film), Raga'' was shot by Howard Worth and released in 1971. Shankar's association with Harrison greatly increased Shankar's popularity, and decades later Ken Hunt (music journalist), Ken Hunt of AllMusic wrote that Shankar had become "the most famous Indian musician on the planet" by 1966. George Harrison organized the charity The Concert for Bangladesh, Concert for Bangladesh in August 1971, in which Shankar participated. During the 1970s, Shankar and Harrison worked together again, recording ''Shankar Family & Friends'' in 1973 and touring North America the following year to a mixed response after Shankar had toured Europe with the Harrison-sponsored Ravi Shankar's Music Festival from India, Music Festival from India.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 195 Shankar wrote a second autobiography, '' Raga Mala'', with Harrison as editor.

Interview with Ravi Shankar

NAMM Oral History Library (2009) {{DEFAULTSORT:Shankar, Ravi 1920 births 2012 deaths 20th-century Indian composers 21st-century Indian composers All India Radio people Angel Records artists Apple Records artists Articles containing video clips Musicians from Varanasi Bengali Hindus Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur Composers awarded knighthoods Dark Horse Records artists Deutsche Grammophon artists EMI Classics and Virgin Classics artists Grammy Award winners Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners Hindi film score composers Hindustani instrumentalists Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Indian classical musicians of Bengal Indian composers of Western classical music Indian Hindus Indian male film score composers Maihar gharana Musicians awarded knighthoods Nominated members of the Rajya Sabha Private Music artists Pupils of Allauddin Khan Ramon Magsaysay Award winners Recipients of the Bharat Ratna Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in arts Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in arts Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale Recipients of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award Recipients of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship Sitar players The Beatles and India

sitar

The sitar ( or ; ) is a plucked stringed instrument, originating from the Indian subcontinent, used in Hindustani classical music. The instrument was invented in medieval India, flourished in the 18th century, and arrived at its present form ...

ist and composer. A sitar virtuoso

A virtuoso (from Italian ''virtuoso'' or , "virtuous", Late Latin ''virtuosus'', Latin ''virtus'', "virtue", "excellence" or "skill") is an individual who possesses outstanding talent and technical ability in a particular art or field such a ...

, he became the world's best-known export of North Indian classical music in the second half of the 20th century, and influenced many musicians in India and throughout the world. Shankar was awarded India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ''Jewel of India'') is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest orde ...

, in 1999.

Shankar was born to a Bengali Brahmin

The Bengali Brahmins are Hindu Brahmins who traditionally reside in the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent, currently comprising the Indian state of West Bengal and the country of Bangladesh.

The Bengali Brahmins, along with Baidyas an ...

family in India, and spent his youth as a dancer touring India and Europe with the dance group of his brother Uday Shankar. He gave up dancing in 1938 to study sitar playing under court musician Allauddin Khan

Allauddin Khan, also known as Baba Allauddin Khan ( – 6 September 1972) was an Indian sarod player and multi-instrumentalist, composer and one of the most notable music teachers of the 20th century in Indian classical music. For a generation m ...

. After finishing his studies in 1944, Shankar worked as a composer, creating the music for the '' Apu Trilogy'' by Satyajit Ray

Satyajit Ray (; 2 May 1921 – 23 April 1992) was an Indian director, screenwriter, documentary filmmaker, author, essayist, lyricist, magazine editor, illustrator, calligrapher, and music composer. One of the greatest auteurs of ...

, and was music director of All India Radio

All or ALL may refer to:

Language

* All, an indefinite pronoun in English

* All, one of the English determiners

* Allar language (ISO 639-3 code)

* Allative case (abbreviated ALL)

Music

* All (band), an American punk rock band

* ''All'' (All ...

, New Delhi, from 1949 to 1956.

In 1956, Shankar began to tour Europe and the Americas playing Indian classical music

Indian classical music is the classical music of the Indian subcontinent. It has two major traditions: the North Indian classical music known as '' Hindustani'' and the South Indian expression known as '' Carnatic''. These traditions were not ...

and increased its popularity there in the 1960s through teaching, performance, and his association with violinist Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi or Jehudi (Hebrew: יהודי, endonym for Jew) is a common Hebrew name:

* Yehudi Menuhin (1916–1999), violinist and conductor

** Yehudi Menuhin School, a music school in Surrey, England

** Who's Yehoodi?, a catchphrase referring to t ...

and Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the most influential band of all time and were integral to the developm ...

guitarist George Harrison

George Harrison (25 February 1943 – 29 November 2001) was an English musician and singer-songwriter who achieved international fame as the lead guitarist of the Beatles. Sometimes called "the quiet Beatle", Harrison embraced Indian c ...

. His influence on Harrison helped popularize the use of Indian instruments in Western pop music in the latter half of the 1960s. Shankar engaged Western music by writing compositions for sitar and orchestra, and toured the world in the 1970s and 1980s. From 1986 to 1992, he served as a nominated member of Rajya Sabha, the upper chamber of the Parliament of India

The Parliament of India ( IAST: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Republic of India. It is a bicameral legislature composed of the president of India and two houses: the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok Sabha (House of ...

. He continued to perform until the end of his life.

Early life

Shankar was born on 7 April 1920 inBenares

Varanasi (; ; also Banaras or Benares (; ), and Kashi.) is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.

*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic tra ...

(now Varanasi), then the capital of the eponymous princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

, in a Bengali family, as the youngest of seven brothers.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 48Massey 1996, p. 159 His father, Shyam Shankar Chowdhury, was a Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's I ...

barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and givin ...

and scholar from East Bengal

ur,

, common_name = East Bengal

, status = Province of the Dominion of Pakistan

, p1 = Bengal Presidency

, flag_p1 = Flag of British Bengal.svg

, s1 = Ea ...

(now Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mo ...

). A respected statesman, lawyer and politician, he served for several years as ''dewan

''Dewan'' (also known as ''diwan'', sometimes spelled ''devan'' or ''divan'') designated a powerful government official, minister, or ruler. A ''dewan'' was the head of a state institution of the same name (see Divan). Diwans belonged to the e ...

'' (Prime minister) of Jhalawar

Jhalawar () is a city, municipal council and headquarter in Jhalawar district of the Indian state of Rajasthan. It is located in the southeastern part of the state. It was the capital of the former princely state of Jhalawar, and is the ad ...

, Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern ...

, and used the Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

spelling of the family name and removed its last part.Ghosh 1983, p. 7 Shyam was married to Hemangini Devi who hailed from a small village named Nasrathpur in Mardah block of Ghazipur district

Ghazipur district is a district of Uttar Pradesh state in northern India. The city of Ghazipur is the district headquarters. The district is part of Varanasi Division. The region of Ghazipur is famous mainly for the production of its unique r ...

, near Benares and her father was a prosperous landlord. Shyam later worked as a lawyer in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, England, and there he married a second time while Devi raised Shankar in Benares, and did not meet his son until he was eight years old.

Shankar shortened the Sanskrit version of his first name, Ravindra, to Ravi, for "sun". Shankar had five siblings: Uday Uday or Odai is a masculine name in Arabic as well as several Indian languages. In many Indian languages it means 'dawn' or 'rise'. The Arabic name (عدي) means 'runner' or 'rising'.

List of people

* Uday Benegal, Indian musician

* Uday Pratap Si ...

(who became a famous choreographer and dancer), Rajendra, Debendra and Bhupendra. Shankar attended the Bengalitola High School in Benares between 1927 and 1928.

At the age of 10, after spending his first decade in Benares, Shankar went to Paris with the dance group of his brother, choreographer Uday Shankar.Slawek 2001, pp. 202–203Ghosh 1983, p. 55 By the age of 13 he had become a member of the group, accompanied its members on tour and learned to dance and play various Indian instruments. Uday's dance group travelled Europe and the United States in the early to mid-1930s and Shankar learned French, discovered Western classical music, jazz, cinema and became acquainted with Western customs.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 50 Shankar heard Allauddin Khan

Allauddin Khan, also known as Baba Allauddin Khan ( – 6 September 1972) was an Indian sarod player and multi-instrumentalist, composer and one of the most notable music teachers of the 20th century in Indian classical music. For a generation m ...

– the lead musician at the court of the princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

of Maihar

Maihar is a tehsil in Satna, Madhya Pradesh, India. Maihar is known for the temple of the revered mother goddess Sharda situated on Trikuta hill.

Origin of the name

It is said that when lord Shiva was carrying the body of the dead mother go ...

– play at a music conference in December 1934 in Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commer ...

, and Uday persuaded the Maharaja of Maihar H.H Maharaja Brijnath singh Judev in 1935 to allow Khan to become his group's soloist for a tour of Europe. Shankar was sporadically trained by Khan on tour, and Khan offered Shankar training to become a serious musician under the condition that he abandon touring and come to Maihar.

Career

Training and work in India

Shankar's parents had died by the time he returned from the Europe tour, and touring the West had become difficult because of political conflicts that would lead to

Shankar's parents had died by the time he returned from the Europe tour, and touring the West had become difficult because of political conflicts that would lead to World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 51 Shankar gave up his dancing career in 1938 to go to Maihar

Maihar is a tehsil in Satna, Madhya Pradesh, India. Maihar is known for the temple of the revered mother goddess Sharda situated on Trikuta hill.

Origin of the name

It is said that when lord Shiva was carrying the body of the dead mother go ...

and study Indian classical music

Indian classical music is the classical music of the Indian subcontinent. It has two major traditions: the North Indian classical music known as '' Hindustani'' and the South Indian expression known as '' Carnatic''. These traditions were not ...

as Khan's pupil, living with his family in the traditional '' gurukul'' system. Khan was a rigorous teacher and Shankar had training on ''sitar'' and ''surbahar

''Surbahar'' (; ) sometimes known as bass sitar, is a plucked string instrument used in the Hindustani classical music of the Indian subcontinent. It is closely related to the sitar, but has a lower pitch. Depending on the instrument's size, it ...

'', learned ''raga

A ''raga'' or ''raag'' (; also ''raaga'' or ''ragam''; ) is a melodic framework for improvisation in Indian classical music akin to a melodic mode. The ''rāga'' is a unique and central feature of the classical Indian music tradition, and as ...

s'' and the musical styles ''dhrupad

Dhrupad is a genre in Hindustani classical music from the Indian subcontinent. It is the oldest known style of major vocal styles associated with Hindustani classical music, Haveli Sangeet of Pushtimarg Sampraday and also related to the South I ...

'', '' dhamar'', and ''khyal

Khyal or Khayal (ख़याल / خیال) is a major form of Hindustani classical music in the Indian subcontinent. Its name comes from a Persian/Arabic word meaning "imagination". Khyal is associated with romantic poetry, and allows the perfo ...

'', and was taught the techniques of the instruments ''rudra veena

The ''Rudra veena'' ( sa, रुद्र वीणा) (also spelled ''Rudraveena'' or ''Rudra vina'')—also called ''Bīn'' in North India—is a large plucked string instrument used in Hindustani Music, especially dhrupad. It is one of the m ...

'', '' rubab'', and ''sursingar

The sursingar (IAST: ), sursringar or surshringar (Sringara: Pleasure in Sanskrit), is a musical instrument originating from the Indian subcontinent having many similarities with the sarod. It is larger than the sarod and produces a deeper sound. ...

''.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 52 He often studied with Khan's children Ali Akbar Khan

Ali Akbar Khan (14 April 192218 June 2009) was a Indian Hindustani classical musician of the Maihar gharana, known for his virtuosity in playing the sarod. Trained as a classical musician and instrumentalist by his father, Allauddin Khan, he a ...

and Annapurna Devi

(1927 – 13 October 2018) was an Indian surbahar (bass sitar) player of Hindustani classical music. She was given the name 'Annapurna' by former Maharaja Brijnath Singh of the former Maihar Estate (M.P.), and it was by this name that she was p ...

. Shankar began to perform publicly on ''sitar'' in December 1939 and his debut performance was a ''jugalbandi

A jugalbandi or jugalbandhi is a performance in Indian classical music, especially in Hindustani classical music but also in Carnatic, that features a duet of two solo musicians. The word jugalbandi means, literally, "entwined twins." The duet ca ...

'' (duet) with Ali Akbar Khan, who played the string instrument ''sarod

The sarod is a stringed instrument, used in Hindustani music on the Indian subcontinent. Along with the sitar, it is among the most popular and prominent instruments. It is known for a deep, weighty, introspective sound, in contrast with the swe ...

''.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 53

Shankar completed his training in 1944. He moved to Mumbai

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the secon ...

and joined the Indian People's Theatre Association

Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA) is the oldest association of theatre-artists in India. IPTA was formed in 1943 during the British rule in India, and promoted themes related to the Indian freedom struggle. Its goal was to bring cultu ...

, for whom he composed music for ballets in 1945 and 1946.Ghosh 1983, p. 57 Shankar recomposed the music for the popular song " Sare Jahan Se Achcha" at the age of 25.Sharma 2007, pp. 163–164 He began to record music for HMV India and worked as a music director for All India Radio

All or ALL may refer to:

Language

* All, an indefinite pronoun in English

* All, one of the English determiners

* Allar language (ISO 639-3 code)

* Allative case (abbreviated ALL)

Music

* All (band), an American punk rock band

* ''All'' (All ...

(AIR), New Delhi, from February 1949 until January 1956. Shankar founded the Indian National Orchestra at AIR and composed for it; in his compositions he combined Western and classical Indian instrumentation.Lavezzoli 2Ravi ShankarRavi ShankarRavi Shankar006, p. 56 Beginning in the mid-1950s he composed the music for the '' Apu Trilogy'' by Satyajit Ray

Satyajit Ray (; 2 May 1921 – 23 April 1992) was an Indian director, screenwriter, documentary filmmaker, author, essayist, lyricist, magazine editor, illustrator, calligrapher, and music composer. One of the greatest auteurs of ...

, which became internationally acclaimed. He was music director for several Hindi movies including '' Godaan'' and ''Anuradha''.

1956–1969: International performances

V. K. Narayana Menon

V. K. Narayana Menon (Thrissur Vadakke Kurupath Narayana Menon) (1911–1997) was a scholar of classical Indian dance and Indian classical music. He was one of the prominent art critics of India and a Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship.

Educat ...

, director of AIR Delhi, introduced the Western violinist Yehudi Menuhin to Shankar during Menuhin's first visit to India in 1952.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 47 Shankar had performed as part of a cultural delegation in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

in 1954 and Menuhin invited Shankar in 1955 to perform in New York City for a demonstration of Indian classical music, sponsored by the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a US$25,000 gift from Edsel Ford. By 1947, after the death ...

.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 57Lavezzoli 2006, p. 58

Shankar heard about the positive response Khan received and resigned from AIR in 1956 to tour the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 61 He played for smaller audiences and educated them about Indian music, incorporating ''ragas'' from the South India

South India, also known as Dakshina Bharata or Peninsular India, consists of the peninsular southern part of India. It encompasses the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana, as well as the union terr ...

n Carnatic music

Carnatic music, known as or in the South Indian languages, is a system of music commonly associated with South India, including the modern Indian states of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, and Sri Lanka. It ...

in his performances, and recorded his first LP album

The LP (from "long playing" or "long play") is an analog sound storage medium, a phonograph record format characterized by: a speed of rpm; a 12- or 10-inch (30- or 25-cm) diameter; use of the "microgroove" groove specification; and ...

''Three Ragas

''Three Ragas'' is a 1956 LP album by Hindustani classical musician Ravi Shankar. It was Audio mastering, digitally remastered and released in Compact Disc, CD format by Angel Records in 2000. AllMusic reviewer Matthew Greenwald praised the perfo ...

'' in London, released in 1956. In 1958, Shankar participated in the celebrations of the 10th anniversary of the United Nations and UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

music festival in Paris. From 1961, he toured Europe, the United States, and Australia, and became the first Indian to compose music for non-Indian films. Shankar founded the Kinnara School of Music in Mumbai

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the secon ...

in 1962.''Brockhaus'', p. 199

Shankar befriended Richard Bock, founder of World Pacific Records, on his first American tour and recorded most of his albums in the 1950s and 1960s for Bock's label. The Byrds

The Byrds () were an American rock band formed in Los Angeles, California, in 1964. The band underwent multiple lineup changes throughout its existence, with frontman Roger McGuinn (known as Jim McGuinn until mid-1967) remaining the sole con ...

recorded at the same studio and heard Shankar's music, which led them to incorporate some of its elements in theirs, introducing the genre to their friend George Harrison of the Beatles.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 62 In 1967, Shankar performed a well-received set at the Monterey Pop Festival

The Monterey International Pop Festival was a three-day music festival held June 16 to 18, 1967, at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in Monterey, California. The festival is remembered for the first major American appearances by the Jimi Hendrix ...

. While complimentary of the talents of several of the rock artists at the festival, he said he was "horrified" to see Jimi Hendrix

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942September 18, 1970) was an American guitarist, singer and songwriter. Although his mainstream career spanned only four years, he is widely regarded as one of the most ...

set fire to his guitar on stage: "That was too much for me. In our culture, we have such respect for musical instruments, they are like part of God." Shankar's live album from Monterey peaked at number 43 on ''Billboard''s pop LPs chart in the US, which remains the highest placing he achieved on that chart.

Shankar won a Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance for '' West Meets East'', a collaboration with Yehudi Menuhin. He opened a Western branch of the Kinnara School of Music in Los Angeles, in May 1967, and published an autobiography, ''My Music, My Life'', in 1968. In 1968, he composed the score for the film '' Charly''.

He performed at the Woodstock Festival

Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held during August 15–18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, United States, southwest of the town of Woodstock, New York, Woodstock. ...

in August 1969, and found he disliked the venue. In the late 1960s, Shankar distanced himself from the hippie

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to different countries around ...

movement and drug culture. He explained during an interview:

1970–2012: International performances

In October 1970, Shankar became chair of the Department of Indian Music of theCalifornia Institute of the Arts

The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) is a private art university in Santa Clarita, California. It was incorporated in 1961 as the first degree-granting institution of higher learning in the US created specifically for students of both ...

after previously teaching at the City College of New York

The City College of the City University of New York (also known as the City College of New York, or simply City College or CCNY) is a public university within the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York City. Founded in 1847, Cit ...

, the University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the Californ ...

, and being guest lecturer at other colleges and universities, including the Ali Akbar College of Music

The Ali Akbar College of Music (AACM) is the name of three schools founded by Indian musician Ali Akbar Khan to teach Indian classical music. The first was founded in 1956 in Calcutta, India. The second was founded in 1967 in Berkeley, Californi ...

.Ghosh 1983, p. 56 In late 1970, the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

invited Shankar to compose a concerto with ''sitar''. '' Concerto for Sitar & Orchestra'' was performed with André Previn

André George Previn (; born Andreas Ludwig Priwin; April 6, 1929 – February 28, 2019) was a German-American pianist, composer, and conductor. His career had three major genres: Hollywood films, jazz, and classical music. In each he achieved ...

as conductor and Shankar playing the ''sitar''.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 221 Shankar performed at the Concert for Bangladesh in August 1971, held at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylv ...

in New York. After the musicians had tuned up on stage for over a minute, the crowd of rock-music fans broke into applause, to which the amused Shankar responded, "If you like our tuning so much, I hope you will enjoy the playing more." which confused the audience. Although interest in Indian music had decreased in the early 1970s, the live album

An album is a collection of audio recordings issued on compact disc (CD), vinyl, audio tape, or another medium such as digital distribution. Albums of recorded sound were developed in the early 20th century as individual 78 rpm records c ...

from the concert became one of the best-selling recordings to feature the genre and won Shankar a second Grammy Award.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 66

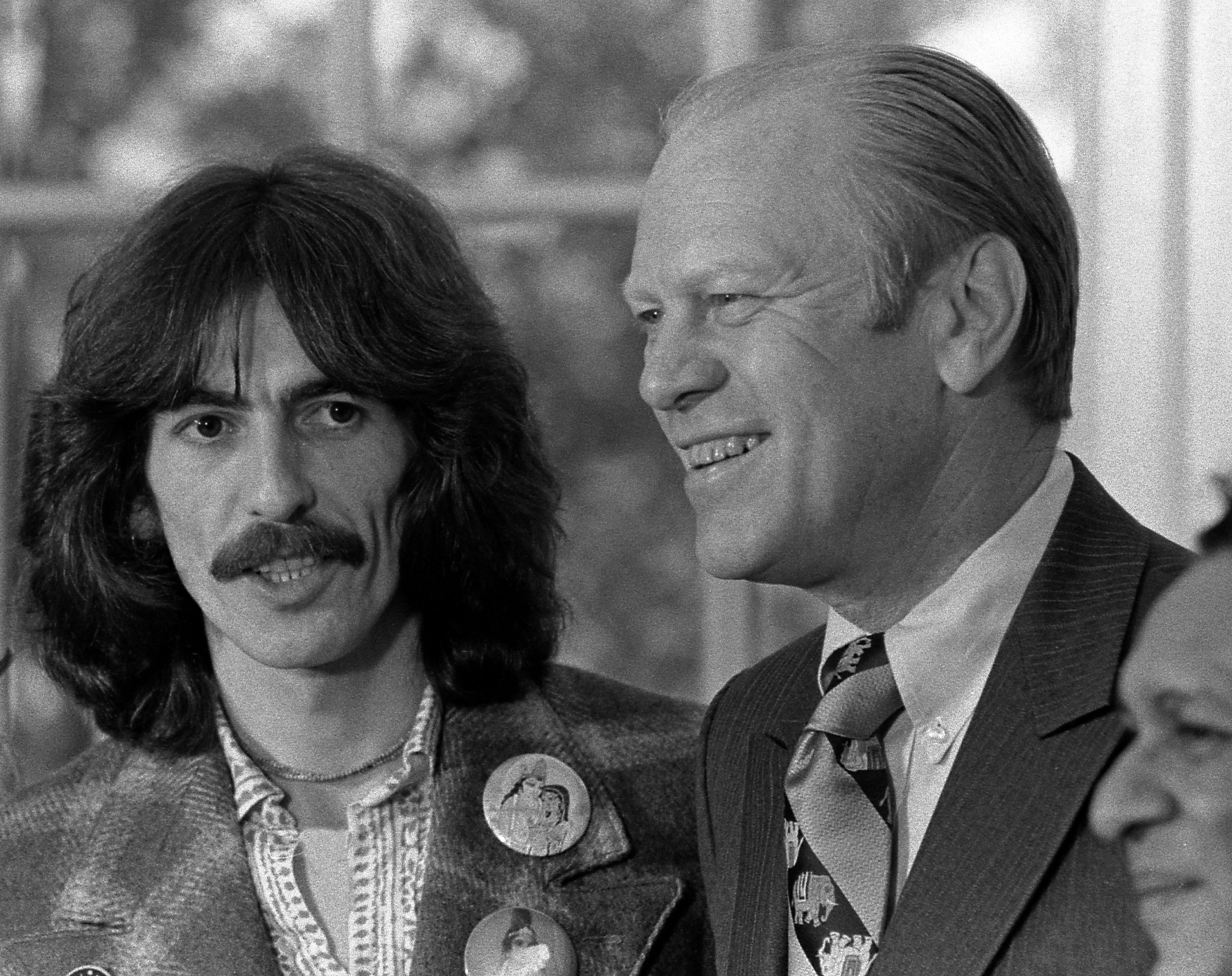

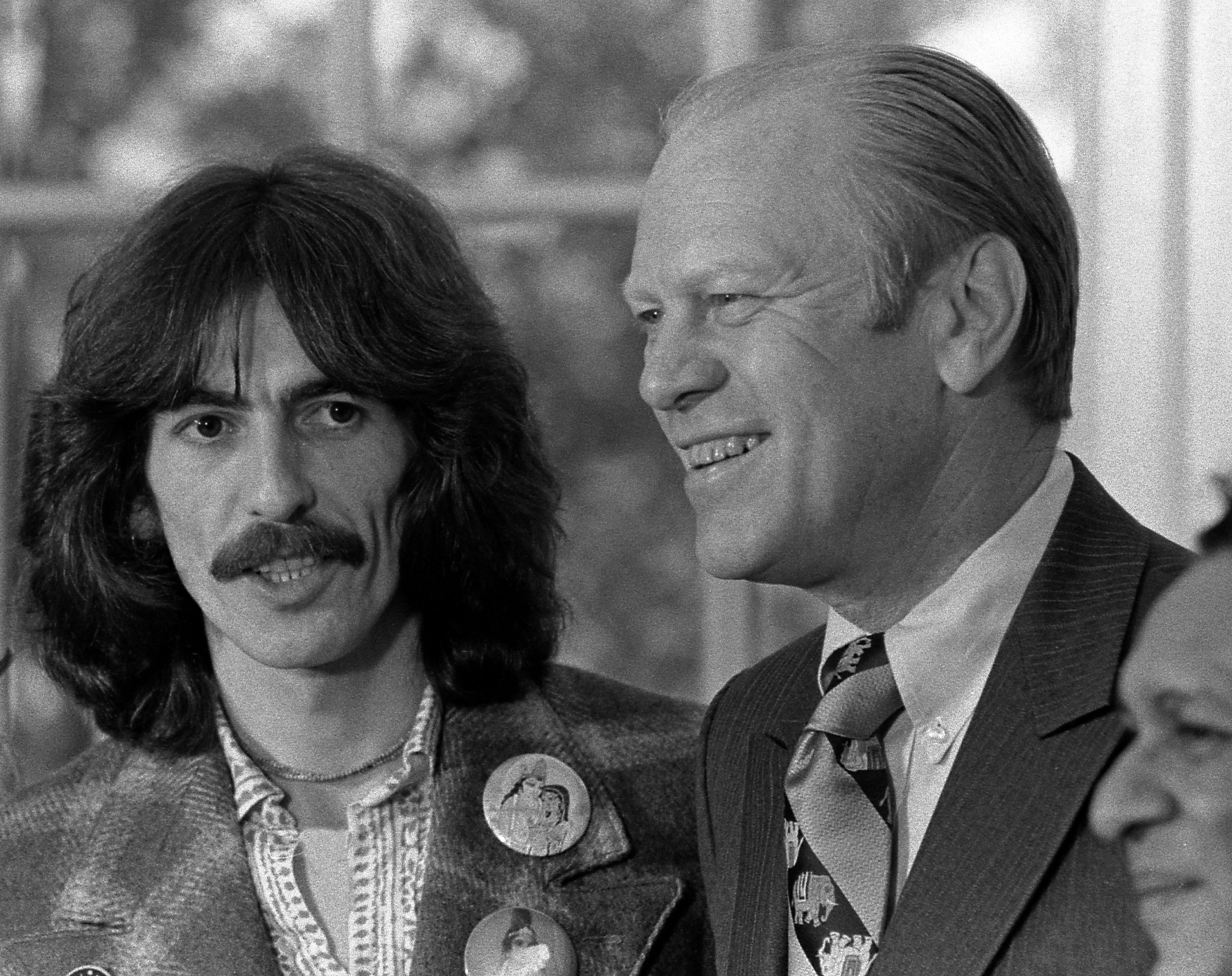

In November and December 1974, Shankar co-headlined a North American tour with George Harrison. The demanding schedule weakened his health, and he suffered a heart attack in Chicago, causing him to miss a portion of the tour. Harrison, Shankar and members of the touring band visited the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

on invitation of John Gardner Ford, son of US president Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

. Shankar toured and taught for the remainder of the 1970s and the 1980s and released his second concerto, ''Raga Mala'', conducted by Zubin Mehta

Zubin Mehta (born 29 April 1936) is an Indian conductor of Western classical music. He is music director emeritus of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (IPO) and conductor emeritus of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Mehta's father was the fou ...

, in 1981.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 222 Shankar was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Music Score for his work on the 1982 movie ''Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

''.

He performed in Moscow in 1988, with 140 musicians, including the Russian Folk Ensemble and members of the Moscow Philharmonic, along with his own group of Indian musicians.

He served as a member of the Rajya Sabha

The Rajya Sabha, constitutionally the Council of States, is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of India. , it has a maximum membership of 245, of which 233 are elected by the legislatures of the states and union territories using si ...

, the upper chamber of the Parliament of India, from 12 May 1986 to 11 May 1992, after being nominated by Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi

Rajiv Gandhi (; 20 August 1944 – 21 May 1991) was an Indian politician who served as the sixth prime minister of India from 1984 to 1989. He took office after the 1984 assassination of his mother, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to beco ...

. Shankar composed the dance drama ''Ghanashyam'' in 1989. His liberal views on musical co-operation led him to contemporary composer Philip Glass

Philip Glass (born January 31, 1937) is an American composer and pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential composers of the late 20th century. Glass's work has been associated with minimalism, being built up from repetitive ...

, with whom he released an album, '' Passages'', in 1990, in a project initiated by Peter Baumann

Peter Baumann (born 29 January 1953) is a German musician. He formed the core line-up of the pioneering German electronic group Tangerine Dream with Edgar Froese and Christopher Franke in 1971. Baumann composed his first solo album in 1976, w ...

of the band Tangerine Dream

Tangerine Dream is a German electronic music band founded in 1967 by Edgar Froese. The group has seen many personnel changes over the years, with Froese having been the only constant member until his death in January 2015. The best-known lineup ...

.

Because of the positive response to Shankar's 1996 career compilation ''

Because of the positive response to Shankar's 1996 career compilation ''In Celebration

''In Celebration'' is a 1975 British drama film directed by Lindsay Anderson. It is based in the 1969 stage production of the same name by David Storey which was also directed by Anderson. The movie was produced and released as part of the Amer ...

'', Shankar wrote a second autobiography, '' Raga Mala''.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 197 He performed between 25 and 40 concerts every year during the late 1990s. Shankar taught his daughter Anoushka Shankar to play ''sitar'' and in 1997 became a Regents' Professor at University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego or colloquially, UCSD) is a public land-grant research university in San Diego, California. Established in 1960 near the pre-existing Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego is ...

.

He performed with Anoushka for the BBC in 1997 at the Symphony Hall in Birmingham, England. In the 2000s, he won a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album for '' Full Circle: Carnegie Hall 2000'' and toured with Anoushka, who released a book about her father, ''Bapi: Love of My Life'', in 2002.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 411 After George Harrison's death in 2001, Shankar performed at the Concert for George

The Concert for George was held at the Royal Albert Hall in London on 29 November 2002 as a memorial to George Harrison on the first anniversary of his death. The event was organised by Harrison's widow, Olivia, and his son, Dhani, and arrang ...

, a celebration of Harrison's music staged at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

in London in 2002.

In June 2008, Shankar played what was billed as his last European concert, but his 2011 tour included dates in the United Kingdom.

On 1 July 2010, at the Southbank Centre

Southbank Centre is a complex of artistic venues in London, England, on the South Bank of the River Thames (between Hungerford Bridge and Waterloo Bridge).

It comprises three main performance venues (the Royal Festival Hall including the Nati ...

's Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is a 2,700-seat concert, dance and talks venue within Southbank Centre in London. It is situated on the South Bank of the River Thames, not far from Hungerford Bridge, in the London Borough of Lambeth. It is a Grade I li ...

, London, England, Anoushka Shankar, on sitar, performed with the London Philharmonic Orchestra

The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) is one of five permanent symphony orchestras based in London. It was founded by the conductors Sir Thomas Beecham and Malcolm Sargent in 1932 as a rival to the existing London Symphony and BBC Symp ...

, conducted by David Murphy, which was billed the first ''Symphony'' by Ravi Shankar.

Collaboration with George Harrison

Beatles guitarist

Beatles guitarist George Harrison

George Harrison (25 February 1943 – 29 November 2001) was an English musician and singer-songwriter who achieved international fame as the lead guitarist of the Beatles. Sometimes called "the quiet Beatle", Harrison embraced Indian c ...

, who was first introduced to Shankar's music by American singers Roger McGuinn and David Crosby,Thomson, Graeme. ''George Harrison: Behind the Locked Door'', Overlook-Omnibus (2016) who were big fans of Shankar, became influenced by Shankar's music. He went on to help popularize Shankar and the Raga rock, use of Indian instruments in pop music throughout the 1960s. Olivia Harrison explains:

Harrison became interested in Indian classical music, bought a sitar and used it to record the song "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)".Schaffner 1980, p. 64 In 1968, he went to India to take lessons from Shankar, some of which were captured on film. This led to Indian music being used by other musicians and popularised the raga rock trend. As the sitar and Indian music grew in popularity, groups such as the Rolling Stones, the Animals and the Byrds began using it in some of their songs."Ravi Shankar, Sitarist Who Introduced Indian Music to the West, Dies at 92", ''New York Times'', 12 December 2012 The influence even extended to blues musicians such as Mike Bloomfield, Michael Bloomfield, who created a raga-influenced improvisation number, "East-West" (Bloomfield scholars have cited its working title as "The Raga" when Bloomfield and his collaborator Nick Gravenites began to develop the idea) for the Butterfield Blues Band in 1966. Harrison met Shankar in London in June 1966 and visited India later that year for six weeks to study ''sitar'' under Shankar in Srinagar. During the visit, a documentary film about Shankar named ''Raga (film), Raga'' was shot by Howard Worth and released in 1971. Shankar's association with Harrison greatly increased Shankar's popularity, and decades later Ken Hunt (music journalist), Ken Hunt of AllMusic wrote that Shankar had become "the most famous Indian musician on the planet" by 1966. George Harrison organized the charity The Concert for Bangladesh, Concert for Bangladesh in August 1971, in which Shankar participated. During the 1970s, Shankar and Harrison worked together again, recording ''Shankar Family & Friends'' in 1973 and touring North America the following year to a mixed response after Shankar had toured Europe with the Harrison-sponsored Ravi Shankar's Music Festival from India, Music Festival from India.Lavezzoli 2006, p. 195 Shankar wrote a second autobiography, '' Raga Mala'', with Harrison as editor.

Style and contributions

Shankar developed a style distinct from that of his contemporaries and incorporated influences from rhythm practices ofCarnatic music

Carnatic music, known as or in the South Indian languages, is a system of music commonly associated with South India, including the modern Indian states of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, and Sri Lanka. It ...

. His performances begin with solo ''alap'', jor (music), ''jor'', and ''jhala'' (introduction and performances with pulse and rapid pulse) influenced by the slow and serious ''dhrupad

Dhrupad is a genre in Hindustani classical music from the Indian subcontinent. It is the oldest known style of major vocal styles associated with Hindustani classical music, Haveli Sangeet of Pushtimarg Sampraday and also related to the South I ...

'' genre, followed by a section with ''tabla'' accompaniment featuring compositions associated with the prevalent ''khyal

Khyal or Khayal (ख़याल / خیال) is a major form of Hindustani classical music in the Indian subcontinent. Its name comes from a Persian/Arabic word meaning "imagination". Khyal is associated with romantic poetry, and allows the perfo ...

'' style. Shankar often closed his performances with a piece inspired by the light-classical ''thumri'' genre.

Shankar has been considered one of the top ''sitar'' players of the second half of the 20th century. He popularised performing on the bass octave of the ''sitar'' for the ''alap'' section and became known for a distinctive playing style in the middle and high registers that used quick and short deviations of the playing string and his sound creation through stops and strikes on the main playing string. Narayana Menon of Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ''The New Grove Dictionary'' noted Shankar's fondness for rhythmic novelties, among them the use of unconventional rhythmic cycles.Menon 1995, p. 220 Hans Neuhoff of ''Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'' has argued that Shankar's playing style was not widely adopted and that he was surpassed by other ''sitar'' players in the performance of melodic passages. Shankar's interplay with Alla Rakha improved appreciation for ''tabla'' playing in Hindustani classical music. Shankar promoted the ''jugalbandi

A jugalbandi or jugalbandhi is a performance in Indian classical music, especially in Hindustani classical music but also in Carnatic, that features a duet of two solo musicians. The word jugalbandi means, literally, "entwined twins." The duet ca ...

'' duet concert style. Shankar introduced at least 31 new ragas, including ''Nat Bhairav'', ''Ahir Lalit'', ''Rasiya'', ''Yaman Manjh'', ''Gunji Kanhara'', ''Janasanmodini'', ''Tilak Shyam'', ''Bairagi'', ''Mohan Kauns'', ''Manamanjari'', ''Mishra Gara'', ''Pancham Se Gara'', ''Purvi Kalyan'', ''Kameshwari'', ''Gangeshwari'', ''Rangeshwari'', ''Parameshwari'', ''Palas Kafi'', ''Jogeshwari'', ''Charu Kauns'', ''Kaushik Todi'', ''Bairagi Todi'', ''Bhawani Bhairav'', ''Sanjh Kalyan'', ''Shailangi'', ''Suranjani'', ''Rajya Kalyan'', ''Banjara'', ''Piloo Banjara'', ''Suvarna'', ''Doga Kalyan'', ''Nanda Dhwani'', and ''Natacharuka (for Anoushka)''. In 2011, at a concert recorded and released in 2012 as ''Tenth Decade in Concert: Ravi Shankar Live in Escondido'', Shankar introduced a new percussive sitar technique called ''Goonga Sitar'', whereby the strings are muffled with a cloth.

Awards

Indian Government honours

*Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ''Jewel of India'') is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest orde ...

(1999)

* Padma Vibhushan (1981)

* Padma Bhushan (1967)

* Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (1962)

*List of Sangeet Natak Akademi fellows, Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship (1975)

*Kalidas Samman from the Government of Madhya Pradesh for 1987–88

Other governmental and academic honours

* Ramon Magsaysay Award (1992) * Commander of the Légion d'honneur, Legion of Honour of France (2000) * Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) for "services to music" (2001) * Honorary degrees from universities in India and the United States. * Honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters * Honorary Doctor of Laws from the University of Melbourne, Australia (2010)Arts awards

* 1964 fellowship from the Asian Cultural Council, John D. Rockefeller 3rd Fund * Silver Bear Extraordinary Prize of the Jury at the 7th Berlin International Film Festival, 1957 Berlin International Film Festival (for composing the music for the movie ''Kabuliwala (1957 film), Kabuliwala''). *UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

International Music Council (1975)

* Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize (1991)

* Praemium Imperiale for music from the Japan Art Association (1997)

* Polar Music Prize (1998)

* Five Grammy Awards

** 1967: Best Chamber Music Performance – West Meets East (with Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi or Jehudi (Hebrew: יהודי, endonym for Jew) is a common Hebrew name:

* Yehudi Menuhin (1916–1999), violinist and conductor

** Yehudi Menuhin School, a music school in Surrey, England

** Who's Yehoodi?, a catchphrase referring to t ...

)

** 1973: Album of the Year – The Concert for Bangladesh (with George Harrison

George Harrison (25 February 1943 – 29 November 2001) was an English musician and singer-songwriter who achieved international fame as the lead guitarist of the Beatles. Sometimes called "the quiet Beatle", Harrison embraced Indian c ...

)

** 2002: Best World Music Album – Full Circle: Carnegie Hall 2000

** 2013: Best World Music Album – The Living Room Sessions Pt. 1

** Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, Lifetime Achievement Award received at the 55th Annual Grammy Awards

* Nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Score, along with George Fenton, for ''Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

''.

* Posthumous nomination in the 56th Annual Grammy Awards for his album "The Living Room Sessions Part 2".

* First recipient of the Tagore Award in recognition of his outstanding contribution to cultural harmony and universal values (2013; posthumous)

Other honours and tributes

* 1997 Interfaith Center of New York, James Parks Morton Interfaith Award * American jazz saxophonist John Coltrane named his son Ravi Coltrane after Shankar. * On 7 April 2016 (his 96th birthday), Google published a Google Doodle to honour his work. Google commented: "Shankar evangelized the use of Indian instruments in Western music, introducing the atmospheric hum of the sitar to audiences worldwide. Shankar's music popularized the fundamentals of Indian music, including raga, a melodic form and widely influenced popular music in the 1960s and 70s.". * In September 2014, a postage stamp featuring Shankar was released by India Post commemorating his contributions.Personal life and family

Shankar marriedAllauddin Khan

Allauddin Khan, also known as Baba Allauddin Khan ( – 6 September 1972) was an Indian sarod player and multi-instrumentalist, composer and one of the most notable music teachers of the 20th century in Indian classical music. For a generation m ...

's daughter Annapurna Devi

(1927 – 13 October 2018) was an Indian surbahar (bass sitar) player of Hindustani classical music. She was given the name 'Annapurna' by former Maharaja Brijnath Singh of the former Maihar Estate (M.P.), and it was by this name that she was p ...

(Roshanara Khan) in 1941 and their son, Shubhendra Shankar, was born in 1942. He separated from Devi during 1962 and continued a relationship with Kamala Shastri, a dancer, that had begun in the late 1940s.

An affair with Sue Jones, a New York concert producer, led to the birth of Norah Jones in 1979. He separated from Shastri in 1981 and lived with Jones until 1986.

An affair with Sukanya Rajan, whom he had known since the 1970s, led to the birth of their daughter Anoushka Shankar in 1981. In 1989, he married Sukanya Rajan at Chilkur Temple in Hyderabad, India, Hyderabad.

Shankar's son, Shubhendra "Shubho" Shankar, often accompanied him on tours. He could play the ''sitar'' and ''surbahar'', but elected not to pursue a solo career. Shubhendra died of pneumonia in 1992.

Ananda Shankar, the experimental fusion musician, is his nephew.

His daughter Norah Jones became a successful musician in the 2000s, winning eight Grammy Awards in 2003.

His daughter Anoushka Shankar was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album in 2003. Anoushka and her father were both nominated for Best World Music Album at the 2013 Grammy Awards for separate albums.

Shankar was a Hinduism, Hindu, and a devotee of the Hindu god Hanuman. He was also an "ardent devotee" of the Bengali Hindu saint, Anandamayi Ma, Sri Anandamayi Ma. Shankar used to visit Anandamayi Ma frequently and performed for her on various occasions. Shankar wrote of his hometown, Benares (Varanasi), and his initial encounter with "Ma":

Varanasi is the eternal abode of Lord Shiva, and one of my favorite temples is that of Lord Hanuman, the monkey god. The city is also where one of the miracles that have happened in my life took place: I met Ma Anandamayi, a great spiritual soul. Seeing the beauty of her face and mind, I became her ardent devotee. Sitting at home now in Encinitas, in Southern California, at the age of 88, surrounded by the beautiful greens, multi-colored flowers, blue sky, clean air, and the Pacific Ocean, I often reminisce about all the wonderful places I have seen in the world. I cherish the memories of Paris, New York, and a few other places. But Varanasi seems to be etched in my heart!Shankar was a vegetarian. He wore a large diamond ring which he said was "manifested" by Sathya Sai Baba. He lived with Sukanya in Encinitas, Encinitas, California. Shankar performed his final concert, with daughter Anoushka, on 4 November 2012 at the Terrace Theater in Long Beach, California.

Illness and death

On 9 December 2012, Shankar was admitted to Scripps Health, Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, San Diego, California after complaining of breathing difficulties. He died on 11 December 2012 at around 16:30 Pacific Standard Time, PST after undergoing Valve replacement, heart valve replacement surgery. The ''Swara Samrat festival'', organized on 5–6 January 2013 and dedicated to Ravi Shankar andAli Akbar Khan

Ali Akbar Khan (14 April 192218 June 2009) was a Indian Hindustani classical musician of the Maihar gharana, known for his virtuosity in playing the sarod. Trained as a classical musician and instrumentalist by his father, Allauddin Khan, he a ...

, included performances by such musicians as Shivkumar Sharma, Birju Maharaj, Hariprasad Chaurasia, Zakir Hussain (musician), Zakir Hussain, and Girija Devi.

Discography

Books

* * *Notes

References

General sources

* * * * * * * * * *External links

* * Ravi Shankar Foundation * *Interview with Ravi Shankar

NAMM Oral History Library (2009) {{DEFAULTSORT:Shankar, Ravi 1920 births 2012 deaths 20th-century Indian composers 21st-century Indian composers All India Radio people Angel Records artists Apple Records artists Articles containing video clips Musicians from Varanasi Bengali Hindus Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur Composers awarded knighthoods Dark Horse Records artists Deutsche Grammophon artists EMI Classics and Virgin Classics artists Grammy Award winners Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners Hindi film score composers Hindustani instrumentalists Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Indian classical musicians of Bengal Indian composers of Western classical music Indian Hindus Indian male film score composers Maihar gharana Musicians awarded knighthoods Nominated members of the Rajya Sabha Private Music artists Pupils of Allauddin Khan Ramon Magsaysay Award winners Recipients of the Bharat Ratna Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in arts Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in arts Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale Recipients of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award Recipients of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship Sitar players The Beatles and India