Oxygenic photosynthesis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Photosynthesis is a process used by

Photosynthesis is a process used by

Most photosynthetic organisms are photoautotrophs, which means that they are able to synthesize food directly from carbon dioxide and water using energy from light. However, not all organisms use carbon dioxide as a source of carbon atoms to carry out photosynthesis; photoheterotrophs use organic compounds, rather than carbon dioxide, as a source of carbon. In plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, photosynthesis releases oxygen. This oxygenic photosynthesis is by far the most common type of photosynthesis used by living organisms. Although there are some differences between oxygenic photosynthesis in

Most photosynthetic organisms are photoautotrophs, which means that they are able to synthesize food directly from carbon dioxide and water using energy from light. However, not all organisms use carbon dioxide as a source of carbon atoms to carry out photosynthesis; photoheterotrophs use organic compounds, rather than carbon dioxide, as a source of carbon. In plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, photosynthesis releases oxygen. This oxygenic photosynthesis is by far the most common type of photosynthesis used by living organisms. Although there are some differences between oxygenic photosynthesis in

In photosynthetic bacteria, the proteins that gather light for photosynthesis are embedded in

In photosynthetic bacteria, the proteins that gather light for photosynthesis are embedded in

In the

In the

In plants, light-dependent reactions occur in the

In plants, light-dependent reactions occur in the

In hot and dry conditions, plants close their

In hot and dry conditions, plants close their

Several groups of animals have formed

Several groups of animals have formed

Jan van Helmont began the research of the process in the mid-17th century when he carefully measured the

Jan van Helmont began the research of the process in the mid-17th century when he carefully measured the

Melvin Calvin and

Melvin Calvin and

There are three main factors affecting photosynthesis and several corollary factors. The three main are:

* Light

There are three main factors affecting photosynthesis and several corollary factors. The three main are:

* Light

The process of photosynthesis provides the main input of free energy into the biosphere, and is one of four main ways in which radiation is important for plant life.

The radiation climate within plant communities is extremely variable, in both time and space.

In the early 20th century,

The process of photosynthesis provides the main input of free energy into the biosphere, and is one of four main ways in which radiation is important for plant life.

The radiation climate within plant communities is extremely variable, in both time and space.

In the early 20th century,

As carbon dioxide concentrations rise, the rate at which sugars are made by the light-independent reactions increases until limited by other factors.

As carbon dioxide concentrations rise, the rate at which sugars are made by the light-independent reactions increases until limited by other factors.

A collection of photosynthesis pages for all levels from a renowned expert (Govindjee)

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20090428090455/http://scienceaid.co.uk/biology/biochemistry/photosynthesis.html Science Aid: PhotosynthesisArticle appropriate for high school science

Metabolism, Cellular Respiration and Photosynthesis – The Virtual Library of Biochemistry and Cell Biology

* ttp://www.life.uiuc.edu/govindjee/photosynBook.html Overall Energetics of Photosynthesis

The source of oxygen produced by photosynthesis

Interactive animation, a textbook tutorial *

Photosynthesis – Light Dependent & Light Independent Stages

Khan Academy, video introduction

{{Authority control Agronomy Biological processes Botany Cellular respiration Ecosystems Metabolism Plant nutrition Plant physiology Quantum biology

Photosynthesis is a process used by

Photosynthesis is a process used by plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...

s and other organisms to convert

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

light energy into chemical energy

Chemical energy is the energy of chemical substances that is released when they undergo a chemical reaction and transform into other substances. Some examples of storage media of chemical energy include batteries, Schmidt-Rohr, K. (2018). "How ...

that, through cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may o ...

molecules, such as sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or do ...

s and starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human die ...

es, which are synthesized from carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

and water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as ...

– hence the name ''photosynthesis'', from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''phōs'' (), "light", and ''synthesis'' (), "putting together". Most plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...

s, algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular micr ...

, and cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, bl ...

perform photosynthesis; such organisms are called photoautotrophs Photoautotrophs are organisms that use light energy and inorganic carbon to produce organic materials. Eukaryotic photoautotrophs absorb energy through the chlorophyll molecules in their chloroplasts while prokaryotic photoautotrophs use chlorophyll ...

. Photosynthesis is largely responsible for producing and maintaining the oxygen content of the Earth's atmosphere, and supplies most of the energy necessary for life on Earth.

Although photosynthesis is performed differently by different species, the process always begins when energy from light is absorbed by protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s called reaction center

A photosynthetic reaction center is a complex of several proteins, pigments and other co-factors that together execute the primary energy conversion reactions of photosynthesis. Molecular excitations, either originating directly from sunlight or ...

s that contain green chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to ...

(and other colored) pigments/chromophores. In plants, these proteins are held inside organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' th ...

s called chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it i ...

s, which are most abundant in leaf cells, while in bacteria they are embedded in the plasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (t ...

. In these light-dependent reactions, some energy is used to strip electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have n ...

s from suitable substances, such as water, producing oxygen gas. The hydrogen freed by the splitting of water is used in the creation of two further compounds that serve as short-term stores of energy, enabling its transfer to drive other reactions: these compounds are reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, abbreviated NADP or, in older notation, TPN (triphosphopyridine nucleotide), is a cofactor used in anabolic reactions, such as the Calvin cycle and lipid and nucleic acid syntheses, which require NAD ...

(NADPH) and adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms ...

(ATP), the "energy currency" of cells.

In plants, algae and cyanobacteria, sugars are synthesized by a subsequent sequence of reactions called the Calvin cycle

The Calvin cycle, light-independent reactions, bio synthetic phase, dark reactions, or photosynthetic carbon reduction (PCR) cycle of photosynthesis is a series of chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen-carrier compounds into ...

. In the Calvin cycle, atmospheric carbon dioxide is incorporated into already existing organic carbon compounds, such as ribulose bisphosphate

Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) is an organic substance that is involved in photosynthesis, notably as the principal acceptor in plants. It is a colourless anion, a double phosphate ester of the ketopentose (ketone-containing sugar with five ca ...

(RuBP). Using the ATP and NADPH produced by the light-dependent reactions, the resulting compounds are then reduced and removed to form further carbohydrates, such as glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

. In other bacteria, different mechanisms such as the reverse Krebs cycle are used to achieve the same end.

The first photosynthetic organisms probably evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variati ...

early in the evolutionary history of life

The history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and fossil organisms evolved, from the earliest emergence of life to present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as ''Ga'', for ''gigaannum'') and evide ...

and most likely used reducing agent

In chemistry, a reducing agent (also known as a reductant, reducer, or electron donor) is a chemical species that "donates" an electron to an (called the , , , or ).

Examples of substances that are commonly reducing agents include the Earth met ...

s such as hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

or hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The under ...

, rather than water, as sources of electrons. Cyanobacteria appeared later; the excess oxygen they produced contributed directly to the oxygenation of the Earth

The Great Oxidation Event (GOE), also called the Great Oxygenation Event, the Oxygen Catastrophe, the Oxygen Revolution, the Oxygen Crisis, or the Oxygen Holocaust, was a time interval during the Paleoproterozoic era when the Earth's atmosphere ...

, which rendered the evolution of complex life

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- ...

possible. Today, the average rate of energy capture by photosynthesis globally is approximately 130 terawatts

The watt (symbol: W) is the unit of power or radiant flux in the International System of Units (SI), equal to 1 joule per second or 1 kg⋅m2⋅s−3. It is used to quantify the rate of energy transfer. The watt is named after James Watt ...

, which is about eight times the current power consumption of human civilization

World energy supply and consumption is global production and preparation of fuel, generation of electricity, energy transport, and energy consumption. It is a basic part of economic activity. It includes heat, but not energy from food.

This art ...

. Photosynthetic organisms also convert around 100–115 billion ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s (91–104 Pg petagrams, or billion metric tons), of carbon into biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms bio ...

per year. That plants receive some energy from light – in addition to air, soil, and water – was first discovered in 1779 by Jan Ingenhousz.

Photosynthesis is vital for climate processes, as it captures carbon dioxide from the air and then binds carbon in plants and further in soils and harvested products. Cereal

A cereal is any grass cultivated for the edible components of its grain (botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran. Cereal grain crops are grown in greater quantities and provide more food ...

s alone are estimated to bind 3,825 Tg (teragrams) or 3.825 Pg (petagrams) of carbon dioxide every year, i.e. 3.825 billion metric tons.

Overview

plants

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclude ...

, algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular micr ...

, and cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, bl ...

, the overall process is quite similar in these organisms. There are also many varieties of anoxygenic photosynthesis

Bacterial anoxygenic photosynthesis differs from the better known oxygenic photosynthesis in plants by the reductant used (e.g. hydrogen sulfide instead of water) and the byproduct generated (e.g. elemental sulfur instead of molecular oxygen).

Ba ...

, used mostly by bacteria, which consume carbon dioxide but do not release oxygen.

Carbon dioxide is converted into sugars in a process called carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation or сarbon assimilation is the process by which inorganic carbon (particularly in the form of carbon dioxide) is converted to organic compounds by living organisms. The compounds are then used to store energy and as ...

; photosynthesis captures energy from sunlight to convert carbon dioxide into carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may o ...

s. Carbon fixation is an endothermic

In thermochemistry, an endothermic process () is any thermodynamic process with an increase in the enthalpy (or internal energy ) of the system.Oxtoby, D. W; Gillis, H.P., Butler, L. J. (2015).''Principle of Modern Chemistry'', Brooks Cole. ...

redox

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or ...

reaction. In general outline, photosynthesis is the opposite of cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

: while photosynthesis is a process of reduction of carbon dioxide to carbohydrates, cellular respiration is the oxidation of carbohydrates or other nutrient

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow, and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excre ...

s to carbon dioxide. Nutrients used in cellular respiration include carbohydrates, amino acids and fatty acids. These nutrients are oxidized to produce carbon dioxide and water, and to release chemical energy to drive the organism's metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run ...

. Photosynthesis and cellular respiration are distinct processes, as they take place through different sequences of chemical reactions and in different cellular compartments.

The general equation

In mathematics, an equation is a formula that expresses the equality of two expressions, by connecting them with the equals sign . The word ''equation'' and its cognates in other languages may have subtly different meanings; for example, in F ...

for photosynthesis as first proposed by Cornelis van Niel is:

: + + → + +

Since water is used as the electron donor in oxygenic photosynthesis, the equation for this process is:

: + + → + +

This equation emphasizes that water is both a reactant in the light-dependent reaction and a product of the light-independent reaction

The Calvin cycle, light-independent reactions, bio synthetic phase, dark reactions, or photosynthetic carbon reduction (PCR) cycle of photosynthesis is a series of chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen-carrier compounds into ...

, but canceling ''n'' water molecules from each side gives the net equation:

: + + → +

Other processes substitute other compounds (such as arsenite

In chemistry, an arsenite is a chemical compound containing an arsenic oxyanion where arsenic has oxidation state +3. Note that in fields that commonly deal with groundwater chemistry, arsenite is used generically to identify soluble AsIII anions. ...

) for water in the electron-supply role; for example some microbes use sunlight to oxidize arsenite to arsenate

The arsenate ion is .

An arsenate (compound) is any compound that contains this ion. Arsenates are salts or esters of arsenic acid.

The arsenic atom in arsenate has a valency of 5 and is also known as pentavalent arsenic or As(V).

Arsenate res ...

: The equation for this reaction is:

: + + → + (used to build other compounds in subsequent reactions)

Photosynthesis occurs in two stages. In the first stage, ''light-dependent reactions'' or ''light reactions'' capture the energy of light and use it to make the hydrogen carrier NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, abbreviated NADP or, in older notation, TPN (triphosphopyridine nucleotide), is a cofactor used in anabolic reactions, such as the Calvin cycle and lipid and nucleic acid syntheses, which require NA ...

and the energy-storage molecule ATP. During the second stage, the ''light-independent reactions'' use these products to capture and reduce carbon dioxide.

Most organisms that use oxygenic photosynthesis use visible light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 t ...

for the light-dependent reactions, although at least three use shortwave infrared

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of Light, visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from ...

or, more specifically, far-red radiation.

Some organisms employ even more radical variants of photosynthesis. Some archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaeba ...

use a simpler method that employs a pigment similar to those used for vision in animals. The bacteriorhodopsin

Bacteriorhodopsin is a protein used by Archaea, most notably by haloarchaea, a class of the Euryarchaeota. It acts as a proton pump; that is, it captures light energy and uses it to move protons across the membrane out of the cell. The resulting ...

changes its configuration in response to sunlight, acting as a proton pump. This produces a proton gradient more directly, which is then converted to chemical energy. The process does not involve carbon dioxide fixation and does not release oxygen, and seems to have evolved separately from the more common types of photosynthesis.

Photosynthetic membranes and organelles

cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (t ...

s. In its simplest form, this involves the membrane surrounding the cell itself. However, the membrane may be tightly folded into cylindrical sheets called thylakoid

Thylakoids are membrane-bound compartments inside chloroplasts and cyanobacteria. They are the site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. Thylakoids consist of a thylakoid membrane surrounding a thylakoid lumen. Chloroplast thyl ...

s, or bunched up into round vesicles

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features o ...

called ''intracytoplasmic membranes''. These structures can fill most of the interior of a cell, giving the membrane a very large surface area and therefore increasing the amount of light that the bacteria can absorb.

In plants and algae, photosynthesis takes place in organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' th ...

s called chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it i ...

s. A typical plant cell

Plant cells are the cells present in green plants, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Their distinctive features include primary cell walls containing cellulose, hemicelluloses and pectin, the presence of plastids with the capab ...

contains about 10 to 100 chloroplasts. The chloroplast is enclosed by a membrane. This membrane is composed of a phospholipid inner membrane, a phospholipid outer membrane, and an intermembrane space. Enclosed by the membrane is an aqueous fluid called the stroma. Embedded within the stroma are stacks of thylakoids (grana), which are the site of photosynthesis. The thylakoids appear as flattened disks. The thylakoid itself is enclosed by the thylakoid membrane, and within the enclosed volume is a lumen or thylakoid space. Embedded in the thylakoid membrane are integral and peripheral membrane protein

Peripheral membrane proteins, or extrinsic membrane proteins, are membrane proteins that adhere only temporarily to the biological membrane with which they are associated. These proteins attach to integral membrane proteins, or penetrate the perip ...

complexes of the photosynthetic system.

Plants absorb light primarily using the pigment

A pigment is a colored material that is completely or nearly insoluble in water. In contrast, dyes are typically soluble, at least at some stage in their use. Generally dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic compou ...

chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to ...

. The green part of the light spectrum is not absorbed but is reflected which is the reason that most plants have a green color. Besides chlorophyll, plants also use pigments such as carotene

The term carotene (also carotin, from the Latin ''carota'', "carrot") is used for many related unsaturated hydrocarbon substances having the formula C40Hx, which are synthesized by plants but in general cannot be made by animals (with the ex ...

s and xanthophyll

Xanthophylls (originally phylloxanthins) are yellow pigments that occur widely in nature and form one of two major divisions of the carotenoid group; the other division is formed by the carotenes. The name is from Greek (, "yellow") and (, "lea ...

s. Algae also use chlorophyll, but various other pigments are present, such as phycocyanin

Phycocyanin is a pigment-protein complex from the light-harvesting phycobiliprotein family, along with allophycocyanin and phycoerythrin. It is an accessory pigment to chlorophyll. All phycobiliproteins are water-soluble, so they cannot exist w ...

, carotene

The term carotene (also carotin, from the Latin ''carota'', "carrot") is used for many related unsaturated hydrocarbon substances having the formula C40Hx, which are synthesized by plants but in general cannot be made by animals (with the ex ...

s, and xanthophyll

Xanthophylls (originally phylloxanthins) are yellow pigments that occur widely in nature and form one of two major divisions of the carotenoid group; the other division is formed by the carotenes. The name is from Greek (, "yellow") and (, "lea ...

s in green algae

The green algae (singular: green alga) are a group consisting of the Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister which contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/ Streptophyta. The land plants (Embryophytes) have emerged deep in the Charophyte alga ...

, phycoerythrin

Phycoerythrin (PE) is a red protein-pigment complex from the light-harvesting phycobiliprotein family, present in cyanobacteria, red algae and cryptophytes, accessory to the main chlorophyll pigments responsible for photosynthesis.The red pigment ...

in red algae

Red algae, or Rhodophyta (, ; ), are one of the oldest groups of eukaryotic algae. The Rhodophyta also comprises one of the largest phyla of algae, containing over 7,000 currently recognized species with taxonomic revisions ongoing. The majority ...

(rhodophytes) and fucoxanthin in brown algae

Brown algae (singular: alga), comprising the class Phaeophyceae, are a large group of multicellular algae, including many seaweeds located in colder waters within the Northern Hemisphere. Brown algae are the major seaweeds of the temperate and p ...

and diatoms

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma''), "a cutting through, a severance", from el, διάτομος, diátomos, "cut in half, divided equally" from el, διατέμνω, diatémno, "to cut in twain". is any member of a large group comprising sev ...

resulting in a wide variety of colors.

These pigments are embedded in plants and algae in complexes called antenna proteins. In such proteins, the pigments are arranged to work together. Such a combination of proteins is also called a light-harvesting complex.

Although all cells in the green parts of a plant have chloroplasts, the majority of those are found in specially adapted structures called leaves

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, st ...

. Certain species adapted to conditions of strong sunlight and arid

A region is arid when it severely lacks available water, to the extent of hindering or preventing the growth and development of plant and animal life. Regions with arid climates tend to lack vegetation and are called xeric or desertic. Most ...

ity, such as many ''Euphorbia

''Euphorbia'' is a very large and diverse genus of flowering plants, commonly called spurge, in the family Euphorbiaceae. "Euphorbia" is sometimes used in ordinary English to collectively refer to all members of Euphorbiaceae (in deference to t ...

'' and cactus

A cactus (, or less commonly, cactus) is a member of the plant family Cactaceae, a family comprising about 127 genera with some 1750 known species of the order Caryophyllales. The word ''cactus'' derives, through Latin, from the Ancient Gree ...

species, have their main photosynthetic organs in their stems. The cells in the interior tissues of a leaf, called the mesophyll

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, ...

, can contain between 450,000 and 800,000 chloroplasts for every square millimeter of leaf. The surface of the leaf is coated with a water-resistant waxy cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

that protects the leaf from excessive evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. High concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evaporation, such as when h ...

of water and decreases the absorption of ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation ...

or blue

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB (additive) colour model. It lies between violet and cyan on the spectrum of visible light. The eye perceives blue when ...

light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 t ...

to minimize heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is ...

ing. The transparent epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the amount of water rel ...

layer allows light to pass through to the palisade

A palisade, sometimes called a stakewall or a paling, is typically a fence or defensive wall made from iron or wooden stakes, or tree trunks, and used as a defensive structure or enclosure. Palisades can form a stockade.

Etymology

''Palisade ...

mesophyll cells where most of the photosynthesis takes place.

Light-dependent reactions

light-dependent reactions

Light-dependent reactions is jargon for certain photochemical reactions that are involved in photosynthesis, the main process by which plants acquire energy. There are two light dependent reactions, the first occurs at photosystem II (PSII) and ...

, one molecule of the pigment

A pigment is a colored material that is completely or nearly insoluble in water. In contrast, dyes are typically soluble, at least at some stage in their use. Generally dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic compou ...

chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to ...

absorbs one photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless, so they alwa ...

and loses one electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have n ...

. This electron is taken up by a modified form of chlorophyll called pheophytin

Pheophytin or phaeophytin is a chemical compound that serves as the first electron carrier intermediate in the electron transfer pathway of Photosystem II (PS II) in plants, and the type II photosynthetic reaction center (RC P870) found in pur ...

, which passes the electron to a quinone

The quinones are a class of organic compounds that are formally "derived from aromatic compounds uch as benzene or naphthalene">benzene.html" ;"title="uch as benzene">uch as benzene or naphthalene] by conversion of an even number of –CH= group ...

molecule, starting the flow of electrons down an electron transport chain

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules that transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples ...

that leads to the ultimate reduction of NADP to NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, abbreviated NADP or, in older notation, TPN (triphosphopyridine nucleotide), is a cofactor used in anabolic reactions, such as the Calvin cycle and lipid and nucleic acid syntheses, which require NA ...

. In addition, this creates a proton gradient

An electrochemical gradient is a gradient of electrochemical potential, usually for an ion that can move across a membrane. The gradient consists of two parts, the chemical gradient, or difference in solute concentration across a membrane, and ...

(energy gradient) across the chloroplast membrane, which is used by ATP synthase

ATP synthase is a protein that catalyzes the formation of the energy storage molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP) using adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). It is classified under ligases as it changes ADP by the formation ...

in the synthesis of ATP. The chlorophyll molecule ultimately regains the electron it lost when a water molecule is split in a process called photolysis

Photodissociation, photolysis, photodecomposition, or photofragmentation is a chemical reaction in which molecules of a chemical compound are broken down by photons. It is defined as the interaction of one or more photons with one target molecule. ...

, which releases oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

.

The overall equation for the light-dependent reactions under the conditions of non-cyclic electron flow in green plants is:

Not all wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tr ...

s of light can support photosynthesis. The photosynthetic action spectrum depends on the type of accessory pigment Accessory pigments are light-absorbing compounds, found in photosynthetic organisms, that work in conjunction with chlorophyll ''a''. They include other forms of this pigment, such as chlorophyll ''b'' in green algal and higher plant antennae, w ...

s present. For example, in green plants, the action spectrum

An action spectrum is a graph of the rate of biological effectiveness plotted against wavelength of light. It is related to absorption spectrum in many systems. Mathematically, it describes the inverse quantity of light required to evoke a const ...

resembles the absorption spectrum

Absorption spectroscopy refers to spectroscopic techniques that measure the absorption of radiation, as a function of frequency or wavelength, due to its interaction with a sample. The sample absorbs energy, i.e., photons, from the radiating ...

for chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to ...

s and carotenoid

Carotenoids (), also called tetraterpenoids, are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, ...

s with absorption peaks in violet-blue and red light. In red algae, the action spectrum is blue-green light, which allows these algae to use the blue end of the spectrum to grow in the deeper waters that filter out the longer wavelengths (red light) used by above-ground green plants. The non-absorbed part of the light spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of frequencies (the spectrum) of electromagnetic radiation and their respective wavelengths and photon energies.

The electromagnetic spectrum covers electromagnetic waves with frequencies ranging from b ...

is what gives photosynthetic organisms their color (e.g., green plants, red algae, purple bacteria) and is the least effective for photosynthesis in the respective organisms.

Z scheme

In plants, light-dependent reactions occur in the

In plants, light-dependent reactions occur in the thylakoid membrane

Thylakoids are membrane-bound compartments inside chloroplasts and cyanobacteria. They are the site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. Thylakoids consist of a thylakoid membrane surrounding a thylakoid lumen. Chloroplast thyla ...

s of the chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it i ...

s where they drive the synthesis of ATP and NADPH. The light-dependent reactions are of two forms: cyclic and non-cyclic.

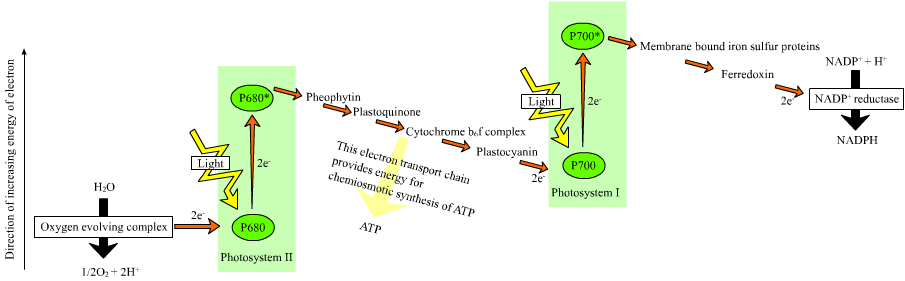

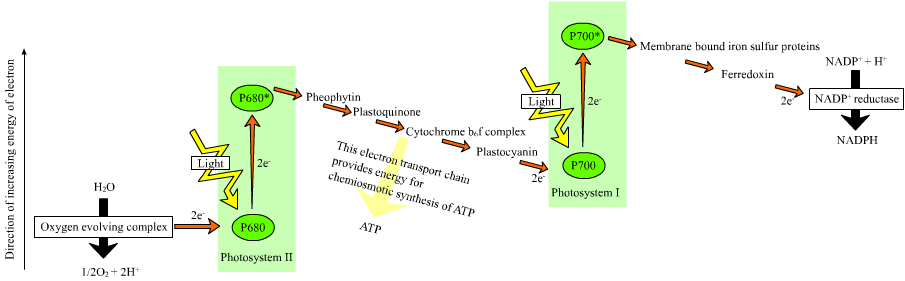

In the non-cyclic reaction, the photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless, so they alwa ...

s are captured in the light-harvesting antenna complex

The light-harvesting complex (or antenna complex; LH or LHC) is an array of protein and chlorophyll molecules embedded in the thylakoid membrane of plants and cyanobacteria, which transfer light energy to one chlorophyll ''a'' molecule at the reac ...

es of photosystem II

Photosystem II (or water-plastoquinone oxidoreductase) is the first protein complex in the light-dependent reactions of oxygenic photosynthesis. It is located in the thylakoid membrane of plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. Within the photosyst ...

by chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to ...

and other accessory pigments Accessory pigments are light-absorbing compounds, found in photosynthetic organisms, that work in conjunction with chlorophyll ''a''. They include other forms of this pigment, such as chlorophyll ''b'' in green algal and higher plant antennae, ...

(see diagram at right). The absorption of a photon by the antenna complex loosens an electron by a process called photoinduced charge separation. The antenna system is at the core of the chlorophyll molecule of the photosystem II reaction center. That loosened electron is taken up by the primary electron-acceptor molecule, pheophytin. As the electrons are shuttled through an electron transport chain

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules that transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples ...

(the so-called ''Z-scheme'' shown in the diagram), a chemiosmotic potential

An electrochemical gradient is a gradient of electrochemical potential, usually for an ion that can move across a membrane. The gradient consists of two parts, the chemical gradient, or difference in solute concentration across a membrane, and ...

is generated by pumping proton cations (H+) across the membrane and into the thylakoid space. An ATP synthase

ATP synthase is a protein that catalyzes the formation of the energy storage molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP) using adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). It is classified under ligases as it changes ADP by the formation ...

enzyme uses that chemiosmotic potential to make ATP during photophosphorylation In the process of photosynthesis, the phosphorylation of ADP to form ATP using the energy of sunlight is called photophosphorylation. Cyclic photophosphorylation occurs in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, driven by the main primary source of ...

, whereas NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, abbreviated NADP or, in older notation, TPN (triphosphopyridine nucleotide), is a cofactor used in anabolic reactions, such as the Calvin cycle and lipid and nucleic acid syntheses, which require NA ...

is a product of the terminal redox

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or ...

reaction in the ''Z-scheme''. The electron enters a chlorophyll molecule in Photosystem I

Photosystem I (PSI, or plastocyanin–ferredoxin oxidoreductase) is one of two photosystems in the photosynthetic light reactions of algae, plants, and cyanobacteria. Photosystem I is an integral membrane protein complex that us ...

. There it is further excited by the light absorbed by that photosystem

Photosystems are functional and structural units of protein complexes involved in photosynthesis. Together they carry out the primary photochemistry of photosynthesis: the absorption of light and the transfer of energy and electrons. Photosy ...

. The electron is then passed along a chain of electron acceptor

An electron acceptor is a chemical entity that accepts electrons transferred to it from another compound. It is an oxidizing agent that, by virtue of its accepting electrons, is itself reduced in the process. Electron acceptors are sometimes mista ...

s to which it transfers some of its energy. The energy delivered to the electron acceptors is used to move hydrogen ions across the thylakoid membrane into the lumen. The electron is eventually used to reduce the co-enzyme NADP with a H+ to NADPH (which has functions in the light-independent reaction); at that point, the path of that electron ends.

The cyclic reaction is similar to that of the non-cyclic but differs in that it generates only ATP, and no reduced NADP (NADPH) is created. The cyclic reaction takes place only at photosystem I. Once the electron is displaced from the photosystem, the electron is passed down the electron acceptor molecules and returns to photosystem I, from where it was emitted, hence the name ''cyclic reaction''.

Water photolysis

Linear electron transport through a photosystem will leave the reaction center of that photosystem oxidized. Elevating another electron will first require re-reduction of the reaction center. The excited electrons lost from the reaction center (P700) ofphotosystem I

Photosystem I (PSI, or plastocyanin–ferredoxin oxidoreductase) is one of two photosystems in the photosynthetic light reactions of algae, plants, and cyanobacteria. Photosystem I is an integral membrane protein complex that us ...

are replaced by transfer from plastocyanin

Plastocyanin is a copper-containing protein that mediates electron-transfer. It is found in a variety of plants, where it participates in photosynthesis. The protein is a prototype of the blue copper proteins, a family of intensely blue-colored ...

, whose electrons come from electron transport through photosystem II

Photosystem II (or water-plastoquinone oxidoreductase) is the first protein complex in the light-dependent reactions of oxygenic photosynthesis. It is located in the thylakoid membrane of plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. Within the photosyst ...

. Photosystem II, as the first step of the ''Z-scheme'', requires an external source of electrons to reduce its oxidized chlorophyll ''a'' reaction center. The source of electrons for photosynthesis in green plants and cyanobacteria is water. Two water molecules are oxidized by the energy of four successive charge-separation reactions of photosystem II to yield a molecule of diatomic oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

and four hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

ions. The electrons yielded are transferred to a redox-active tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a non-essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the G ...

residue that is oxidized by the energy of P680. This resets the ability of P680 to absorb another photon and release another photo-dissociated electron. The oxidation of water is catalyzed in photosystem II by a redox-active structure that contains four manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of ...

ions and a calcium ion; this oxygen-evolving complex

The oxygen-evolving complex (OEC), also known as the water-splitting complex, is the portion of photosystem II where photo-oxidation of water occurs during the light reactions of photosynthesis. The OEC is surrounded by four core protein subunits ...

binds two water molecules and contains the four oxidizing equivalents that are used to drive the water-oxidizing reaction (Kok's S-state diagrams). The hydrogen ions are released in the thylakoid lumen and therefore contribute to the transmembrane chemiosmotic potential that leads to ATP synthesis. Oxygen is a waste product of light-dependent reactions, but the majority of organisms on Earth use oxygen and its energy for cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

, including photosynthetic organisms.

Light-independent reactions

Calvin cycle

In the light-independent (or "dark") reactions, theenzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

RuBisCO

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase, commonly known by the abbreviations RuBisCo, rubisco, RuBPCase, or RuBPco, is an enzyme () involved in the first major step of carbon fixation, a process by which atmospheric carbon dioxide is con ...

captures CO2 from the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A ...

and, in a process called the Calvin cycle

The Calvin cycle, light-independent reactions, bio synthetic phase, dark reactions, or photosynthetic carbon reduction (PCR) cycle of photosynthesis is a series of chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen-carrier compounds into ...

, uses the newly formed NADPH and releases three-carbon sugars, which are later combined to form sucrose and starch. The overall equation for the light-independent reactions in green plants is

Carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation or сarbon assimilation is the process by which inorganic carbon (particularly in the form of carbon dioxide) is converted to organic compounds by living organisms. The compounds are then used to store energy and as ...

produces the three-carbon sugar intermediate, which is then converted into the final carbohydrate products. The simple carbon sugars produced by photosynthesis are then used to form other organic compounds, such as the building material cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wa ...

, the precursors for lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids in ...

and amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

biosynthesis, or as a fuel in cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

. The latter occurs not only in plants but also in animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage ...

s when the carbon and energy from plants is passed through a food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), de ...

.

The fixation or reduction of carbon dioxide is a process in which carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

combines with a five-carbon sugar, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate

Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) is an organic substance that is involved in photosynthesis, notably as the principal acceptor in plants. It is a colourless anion, a double phosphate ester of the ketopentose (ketone-containing sugar with five ca ...

, to yield two molecules of a three-carbon compound, glycerate 3-phosphate, also known as 3-phosphoglycerate. Glycerate 3-phosphate, in the presence of ATP and NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, abbreviated NADP or, in older notation, TPN (triphosphopyridine nucleotide), is a cofactor used in anabolic reactions, such as the Calvin cycle and lipid and nucleic acid syntheses, which require NA ...

produced during the light-dependent stages, is reduced to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, also known as triose phosphate or 3-phosphoglyceraldehyde and abbreviated as G3P, GA3P, GADP, GAP, TP, GALP or PGAL, is a metabolite that occurs as an intermediate in several central pathways of all organisms.Nelson, D ...

. This product is also referred to as 3-phosphoglyceraldehyde (PGAL

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, also known as triose phosphate or 3-phosphoglyceraldehyde and abbreviated as G3P, GA3P, GADP, GAP, TP, GALP or PGAL, is a metabolite that occurs as an intermediate in several central pathways of all organisms.Nelson, D ...

) or, more generically, as triose

A triose is a monosaccharide, or simple sugar, containing three carbon atoms. There are only three possible trioses (including dihydroxyacetone): L-glyceraldehyde and D-glyceraldehyde, the two enantiomers of glyceraldehyde, which are aldotrio ...

phosphate. Most (5 out of 6 molecules) of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate produced are used to regenerate ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate so the process can continue. The triose phosphates not thus "recycled" often condense to form hexose

In chemistry, a hexose is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) with six carbon atoms. The chemical formula for all hexoses is C6H12O6, and their molecular weight is 180.156 g/mol.

Hexoses exist in two forms, open-chain or cyclic, that easily convert ...

phosphates, which ultimately yield sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refine ...

, starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human die ...

and cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wa ...

. The sugars produced during carbon metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run ...

yield carbon skeletons that can be used for other metabolic reactions like the production of amino acids

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

and lipids

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids in ...

.

Carbon concentrating mechanisms

On land

stomata

In botany, a stoma (from Greek ''στόμα'', "mouth", plural "stomata"), also called a stomate (plural "stomates"), is a pore found in the epidermis of leaves, stems, and other organs, that controls the rate of gas exchange. The pore is b ...

to prevent water loss. Under these conditions, will decrease and oxygen gas, produced by the light reactions of photosynthesis, will increase, causing an increase of photorespiration

Photorespiration (also known as the oxidative photosynthetic carbon cycle or C2 cycle) refers to a process in plant metabolism where the enzyme RuBisCO oxygenates RuBP, wasting some of the energy produced by photosynthesis. The desired reactio ...

by the oxygenase

An oxygenase is any enzyme that oxidizes a substrate by transferring the oxygen from molecular oxygen O2 (as in air) to it. The oxygenases form a class of oxidoreductases; their EC number is EC 1.13 or EC 1.14.

Discoverers

Oxygenases were discov ...

activity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and decrease in carbon fixation. Some plants have evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variati ...

mechanisms to increase the concentration in the leaves under these conditions.

Plants that use the C4 carbon fixation process chemically fix carbon dioxide in the cells of the mesophyll by adding it to the three-carbon molecule phosphoenolpyruvate

Phosphoenolpyruvate (2-phosphoenolpyruvate, PEP) is the ester derived from the enol of pyruvate and phosphate. It exists as an anion. PEP is an important intermediate in biochemistry. It has the highest-energy phosphate bond found (−61.9 kJ/m ...

(PEP), a reaction catalyzed by an enzyme called PEP carboxylase, creating the four-carbon organic acid oxaloacetic acid. Oxaloacetic acid or malate

Malic acid is an organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a dicarboxylic acid that is made by all living organisms, contributes to the sour taste of fruits, and is used as a food additive. Malic acid has two stereoisomeric forms (L ...

synthesized by this process is then translocated to specialized bundle sheath cells where the enzyme RuBisCO

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase, commonly known by the abbreviations RuBisCo, rubisco, RuBPCase, or RuBPco, is an enzyme () involved in the first major step of carbon fixation, a process by which atmospheric carbon dioxide is con ...

and other Calvin cycle enzymes are located, and where released by decarboxylation

Decarboxylation is a chemical reaction that removes a carboxyl group and releases carbon dioxide (CO2). Usually, decarboxylation refers to a reaction of carboxylic acids, removing a carbon atom from a carbon chain. The reverse process, which is ...

of the four-carbon acids is then fixed by RuBisCO activity to the three-carbon 3-phosphoglyceric acid

3-Phosphoglyceric acid (3PG, 3-PGA, or PGA) is the conjugate acid of 3-phosphoglycerate or glycerate 3-phosphate (GP or G3P). This glycerate is a biochemically significant metabolic intermediate in both glycolysis and the Calvin-Benson cycle. The ...

s. The physical separation of RuBisCO from the oxygen-generating light reactions reduces photorespiration and increases fixation and, thus, the photosynthetic capacity

Photosynthetic capacity (Amax) is a measure of the maximum rate at which leaves are able to fix carbon during photosynthesis. It is typically measured as the amount of carbon dioxide that is fixed per metre squared per second, for example as μmo ...

of the leaf. plants can produce more sugar than plants in conditions of high light and temperature. Many important crop plants are plants, including maize, sorghum, sugarcane, and millet. Plants that do not use PEP-carboxylase in carbon fixation are called C3 plants because the primary carboxylation reaction, catalyzed by RuBisCO, produces the three-carbon 3-phosphoglyceric acids directly in the Calvin-Benson cycle. Over 90% of plants use carbon fixation, compared to 3% that use carbon fixation; however, the evolution of in over 60 plant lineages makes it a striking example of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

. C2 photosynthesis, which involves carbon-concentration by selective breakdown of photorespiratory glycine, is both an evolutionary precursor to and a useful CCM in its own right.

Xerophytes

A xerophyte (from Greek ξηρός ''xeros'' 'dry' + φυτόν ''phuton'' 'plant') is a species of plant that has adaptations to survive in an environment with little liquid water, such as a desert such as the Sahara or places in the Alps or the ...

, such as cacti

A cactus (, or less commonly, cactus) is a member of the plant family Cactaceae, a family comprising about 127 genera with some 1750 known species of the order Caryophyllales. The word ''cactus'' derives, through Latin, from the Ancient Gree ...

and most succulents

In botany, succulent plants, also known as succulents, are plants with parts that are thickened, fleshy, and engorged, usually to retain water in arid climates or soil conditions. The word ''succulent'' comes from the Latin word ''sucus'', meani ...

, also use PEP carboxylase to capture carbon dioxide in a process called Crassulacean acid metabolism

Crassulacean acid metabolism, also known as CAM photosynthesis, is a carbon fixation pathway that evolved in some plants as an adaptation to arid conditions that allows a plant to photosynthesize during the day, but only exchange gases at night. ...

(CAM). In contrast to metabolism, which ''spatially'' separates the fixation to PEP from the Calvin cycle, CAM ''temporally'' separates these two processes. CAM plants have a different leaf anatomy from plants, and fix the at night, when their stomata are open. CAM plants store the mostly in the form of malic acid via carboxylation of phosphoenolpyruvate

Phosphoenolpyruvate (2-phosphoenolpyruvate, PEP) is the ester derived from the enol of pyruvate and phosphate. It exists as an anion. PEP is an important intermediate in biochemistry. It has the highest-energy phosphate bond found (−61.9 kJ/m ...

to oxaloacetate, which is then reduced to malate. Decarboxylation of malate during the day releases inside the leaves, thus allowing carbon fixation to 3-phosphoglycerate by RuBisCO. CAM is used by 16,000 species of plants.

Calcium oxalate

Calcium oxalate (in archaic terminology, oxalate of lime) is a calcium salt of oxalic acid with the chemical formula . It forms hydrates , where ''n'' varies from 1 to 3. Anhydrous and all hydrated forms are colorless or white. The monohydrate ...

accumulating plants, such as ''Amaranthus hybridus

''Amaranthus hybridus'', commonly called green amaranth, slim amaranth, smooth amaranth, smooth pigweed, or red amaranth, is a species of annual flowering plant. It is a weedy species found now over much of North America and introduced into Europ ...

'' and '' Colobanthus quitensis,'' show a variation of photosynthesis where calcium oxalate crystals

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

function as dynamic carbon pools, supplying carbon dioxide ( CO2) to photosynthetic cells when stoma

In botany, a stoma (from Greek ''στόμα'', "mouth", plural "stomata"), also called a stomate (plural "stomates"), is a pore found in the epidermis of leaves, stems, and other organs, that controls the rate of gas exchange. The pore is bo ...

ta are partially or totally closed. This process was named Alarm photosynthesis. Under stress conditions (e.g. water deficit) oxalate released from calcium oxalate crystals is converted to CO2 by an oxalate oxidase enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

and the produced CO2 can support the Calvin cycle

The Calvin cycle, light-independent reactions, bio synthetic phase, dark reactions, or photosynthetic carbon reduction (PCR) cycle of photosynthesis is a series of chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen-carrier compounds into ...

reactions. Reactive hydrogen peroxide ( H2O2), the byproduct of oxalate oxidase reaction, can be neutralized by catalase

Catalase is a common enzyme found in nearly all living organisms exposed to oxygen (such as bacteria, plants, and animals) which catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. It is a very important enzyme in protecting t ...

. Alarm photosynthesis represents a photosynthetic variant to be added to the well-known C4 and CAM

Calmodulin (CaM) (an abbreviation for calcium-modulated protein) is a multifunctional intermediate calcium-binding messenger protein expressed in all eukaryotic cells. It is an intracellular target of the secondary messenger Ca2+, and the bin ...

pathways. However, alarm photosynthesis, in contrast to these pathways, operates as a biochemical pump that collects carbon from the organ interior (or from the soil) and not from the atmosphere.

In water

Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, bl ...

possess carboxysomes, which increase the concentration of around RuBisCO to increase the rate of photosynthesis. An enzyme, carbonic anhydrase

The carbonic anhydrases (or carbonate dehydratases) () form a family of enzymes that catalyze the interconversion between carbon dioxide and water and the dissociated ions of carbonic acid (i.e. bicarbonate and hydrogen ions). The active sit ...

, located within the carboxysome releases CO2 from dissolved hydrocarbonate ions (HCO). Before the CO2 diffuses out it is quickly sponged up by RuBisCO, which is concentrated within the carboxysomes. HCO ions are made from CO2 outside the cell by another carbonic anhydrase and are actively pumped into the cell by a membrane protein. They cannot cross the membrane as they are charged, and within the cytosol they turn back into CO2 very slowly without the help of carbonic anhydrase. This causes the HCO ions to accumulate within the cell from where they diffuse into the carboxysomes. Pyrenoid

Pyrenoids are sub-cellular micro-compartments found in chloroplasts of many algae,Giordano, M., Beardall, J., & Raven, J. A. (2005). CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Bio ...

s in algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular micr ...

and hornwort

Hornworts are a group of non-vascular Embryophytes (land plants) constituting the division Anthocerotophyta (). The common name refers to the elongated horn-like structure, which is the sporophyte. As in mosses and liverworts, hornworts have a ...

s also act to concentrate around RuBisCO.

Order and kinetics

The overall process of photosynthesis takes place in four stages:Efficiency

Plants usually convert light intochemical energy

Chemical energy is the energy of chemical substances that is released when they undergo a chemical reaction and transform into other substances. Some examples of storage media of chemical energy include batteries, Schmidt-Rohr, K. (2018). "How ...

with a photosynthetic efficiency The photosynthetic efficiency is the fraction of light energy converted into chemical energy during photosynthesis in green plants and algae. Photosynthesis can be described by the simplified chemical reaction

:6 H2O + 6 CO2 + energy → C6H12O6 + ...

of 3–6%.

Absorbed light that is unconverted is dissipated primarily as heat, with a small fraction (1–2%) re-emitted as chlorophyll fluorescence

Chlorophyll fluorescence is light re-emitted by chlorophyll molecules during return from excited to non-excited states. It is used as an indicator of photosynthetic energy conversion in plants, algae and bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: b ...

at longer (redder) wavelengths. This fact allows measurement of the light reaction of photosynthesis by using chlorophyll fluorometers.

Actual plants' photosynthetic efficiency varies with the frequency of the light being converted, light intensity, temperature and proportion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and can vary from 0.1% to 8%. By comparison, solar panels

A solar cell panel, solar electric panel, photo-voltaic (PV) module, PV panel or solar panel is an assembly of photovoltaic solar cells mounted in a (usually rectangular) frame, and a neatly organised collection of PV panels is called a photo ...

convert light into electric energy

Electrical energy is energy related to forces on electrically charged particles and the movement of electrically charged particles (often electrons in wires, but not always). This energy is supplied by the combination of electric current and electr ...

at an efficiency of approximately 6–20% for mass-produced panels, and above 40% in laboratory devices.

Scientists are studying photosynthesis in hopes of developing plants with increased yield.

The efficiency of both light and dark reactions can be measured but the relationship between the two can be complex. For example, the ATP and NADPH energy molecules, created by the light reaction, can be used for carbon fixation or for photorespiration in C3 plants. Electrons may also flow to other electron sinks. For this reason, it is not uncommon for authors to differentiate between work done under non-photorespiratory conditions and under photorespiratory conditions.

Chlorophyll fluorescence of photosystem II can measure the light reaction, and infrared gas analyzers can measure the dark reaction. It is also possible to investigate both at the same time using an integrated chlorophyll fluorometer and gas exchange system, or by using two separate systems together. Infrared gas analyzers and some moisture sensors are sensitive enough to measure the photosynthetic assimilation of CO2, and of ΔH2O using reliable methods CO2 is commonly measured in μmols/(m2/s), parts per million or volume per million and H2O is commonly measured in mmol/(m2/s) or in mbars. By measuring CO2 assimilation, ΔH2O, leaf temperature, barometric pressure, leaf area, and photosynthetically active radiation or PAR, it becomes possible to estimate, "A" or carbon assimilation, "E" or transpiration, "gs" or stomatal conductance, and Ci or intracellular CO2. However, it is more common to used chlorophyll fluorescence for plant stress measurement, where appropriate, because the most commonly used parameters FV/FM and Y(II) or F/FM' can be measured in a few seconds, allowing the investigation of larger plant populations.

Gas exchange systems that offer control of CO2 levels, above and below ambient, allow the common practice of measurement of A/Ci curves, at different CO2 levels, to characterize a plant's photosynthetic response.

Integrated chlorophyll fluorometer – gas exchange systems allow a more precise measure of photosynthetic response and mechanisms. While standard gas exchange photosynthesis systems can measure Ci, or substomatal CO2 levels, the addition of integrated chlorophyll fluorescence measurements allows a more precise measurement of CC to replace Ci. The estimation of CO2 at the site of carboxylation in the chloroplast, or CC, becomes possible with the measurement of mesophyll conductance or gm using an integrated system.

Photosynthesis measurement systems are not designed to directly measure the amount of light absorbed by the leaf. But analysis of chlorophyll-fluorescence, P700- and P515-absorbance and gas exchange measurements reveal detailed information about e.g. the photosystems, quantum efficiency and the CO2 assimilation rates. With some instruments, even wavelength-dependency of the photosynthetic efficiency can be analyzed.

A phenomenon known as quantum walk

Quantum walks are quantum analogues of classical random walks. In contrast to the classical random walk, where the walker occupies definite states and the randomness arises due to stochastic transitions between states, in quantum walks randomness ...

increases the efficiency of the energy transport of light significantly. In the photosynthetic cell of an alga, bacterium, or plant, there are light-sensitive molecules called chromophore

A chromophore is the part of a molecule responsible for its color.

The color that is seen by our eyes is the one not absorbed by the reflecting object within a certain wavelength spectrum of visible light. The chromophore is a region in the mo ...

s arranged in an antenna-shaped structure named a photocomplex. When a photon is absorbed by a chromophore, it is converted into a quasiparticle