Otto Hersing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Otto Hersing (30 November 1885 – 1 July 1960) was a German naval officer who served as

On September 5, Hersing spotted the

On September 5, Hersing spotted the  At the beginning of 1915, Hersing received the

At the beginning of 1915, Hersing received the

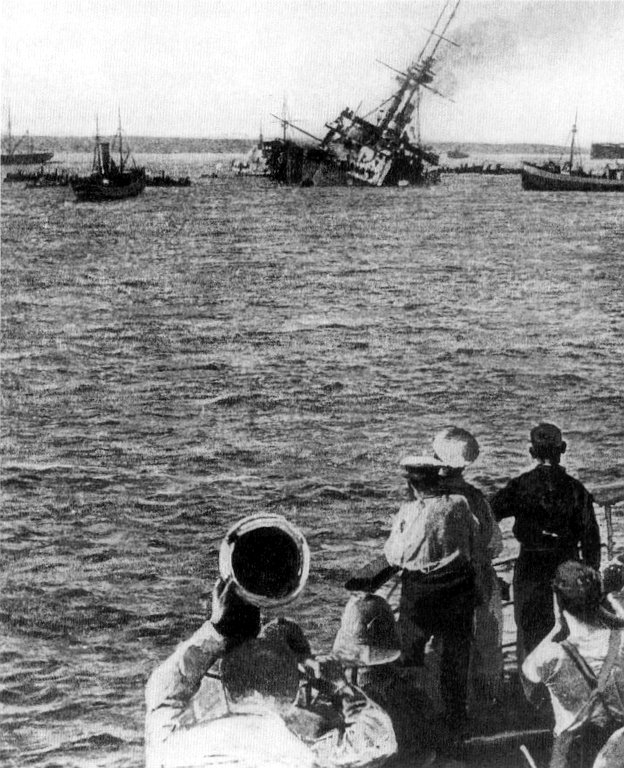

After a week in the friendly port, Hersing sailed to his new operational area off Gallipoli, which he reached on 25 May. The same day, he spotted the British battleship HMS ''Triumph''. Hersing brought his U-boat to within 300 yards (270 m) of his target and fired a single torpedo, which hit the battleship and caused it to capsize and sink, causing the death of 3 officers and 75 members of the crew. After the action, ''Kapitänleutnant'' Hersing took his submarine to the seafloor and waited there for 28 hours before resurfacing to recharge the electric batteries.

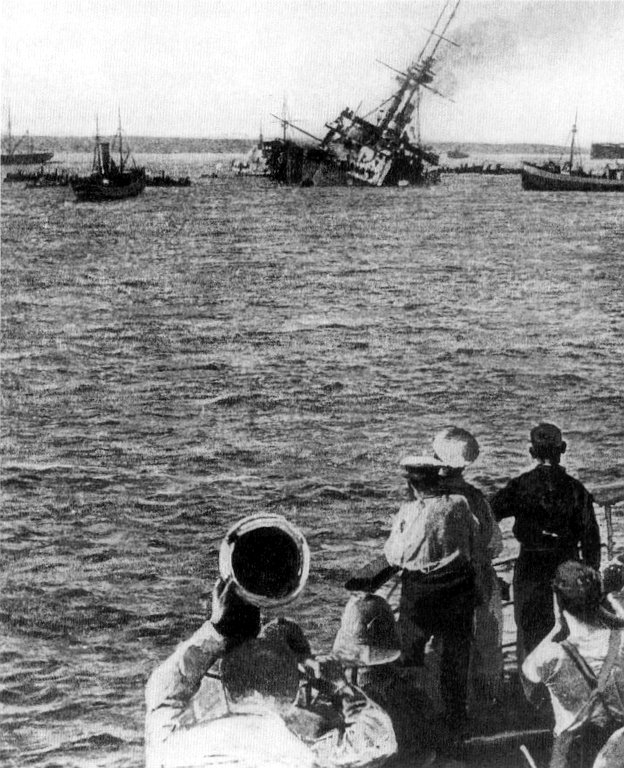

On 27 May, ''U-21'' sank her second Allied battleship in the Dardanelles, the ''Majestic''. Hersing was able to avoid the escorting vessels and the

After a week in the friendly port, Hersing sailed to his new operational area off Gallipoli, which he reached on 25 May. The same day, he spotted the British battleship HMS ''Triumph''. Hersing brought his U-boat to within 300 yards (270 m) of his target and fired a single torpedo, which hit the battleship and caused it to capsize and sink, causing the death of 3 officers and 75 members of the crew. After the action, ''Kapitänleutnant'' Hersing took his submarine to the seafloor and waited there for 28 hours before resurfacing to recharge the electric batteries.

On 27 May, ''U-21'' sank her second Allied battleship in the Dardanelles, the ''Majestic''. Hersing was able to avoid the escorting vessels and the

U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

commander in the ''Kaiserliche Marine

{{italic title

The adjective ''kaiserlich'' means "imperial" and was used in the German-speaking countries to refer to those institutions and establishments over which the ''Kaiser'' ("emperor") had immediate personal power of control.

The term wa ...

'' and the '' k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'' during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

In September 1914, while in command of the German '' U-21'' submarine, he became famous for the first sinking of an enemy ship by a self-propelled locomotive torpedo.

Career

Early life and training

Hersing joined theImperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Kaise ...

in 1903. He received his first training on the school ship '' Stosch'', on the corvette '' Blücher'' and on the artillery training ship ''Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

''. He served as a ''Fähnrich

Fähnrich () is an officer candidate rank in the Austrian Bundesheer and German Bundeswehr. The word comes from an older German military title, (flag bearer), and first became a distinct military rank in Germany on 1 January 1899. However, ...

'' on the battleship ''Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

''. In September 1906 he was promoted to ''Leutnant

() is the lowest Junior officer rank in the armed forces the German-speaking of Germany (Bundeswehr), Austrian Armed Forces, and military of Switzerland.

History

The German noun (with the meaning "" (in English "deputy") from Middle High Ge ...

'' and transferred on the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to th ...

''Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

''. On 1909, he was promoted to '' Oberleutnant''. From 1911 to 1913, Hersing served as watch officer

Watchkeeping or watchstanding is the assignment of sailors to specific roles on a ship to operate it continuously. These assignments, also known at sea as ''watches'', are constantly active as they are considered essential to the safe operation o ...

on the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers re ...

'' Hertha'', and he had the chance to sail around the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

and the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

.

World War I and North Sea operations

In 1914, Hersing was promoted to ''Kapitänleutnant

''Kapitänleutnant'', short: KptLt/in lists: KL, ( en, captain lieutenant) is an officer grade of the captains' military hierarchy group () of the German Bundeswehr. The rank is rated OF-2 in NATO, and equivalent to Hauptmann in the Heer an ...

'' and received special training for the submarine warfare. When World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

broke out, he was given command of '' U-21'', at the time located at the island of Heligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

. Between August and September, ''U-21'' carried out reconnaissance in the North Sea, but he was not able to find any enemy ships. Hersing then tried to force his way into the Firth of Forth, at that time a British naval base, but with no success.

On September 5, Hersing spotted the

On September 5, Hersing spotted the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to th ...

''Pathfinder

Pathfinder may refer to:

Businesses

* Pathfinder Energy Services, a division of Smith International

* Pathfinder Press, a publisher of socialist literature

Computing and information science

* Path Finder, a Macintosh file browser

* Pathfinder ( ...

'' off the Scottish coast, sailing at a reduced speed of 5 knots

A knot is a fastening in rope or interwoven lines.

Knot may also refer to:

Places

* Knot, Nancowry, a village in India

Archaeology

* Knot of Isis (tyet), symbol of welfare/life.

* Minoan snake goddess figurines#Sacral knot

Arts, entertainme ...

due to a shortage of coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

. Hersing decided to attack the ship and hit her with a single torpedo just below the bridge, close to the ship's powder magazine, which was destroyed by a great explosion. The ship sank in a short time, and 261 sailors were killed. It was the first sinking of a modern warship by a submarine armed with torpedoes.

On 14 November, ''U-21'' intercepted the French steamer ''Malachite''. Hersing ordered the crew to abandon the ship before he sank the vessel with his deck gun

A deck gun is a type of naval artillery mounted on the deck of a submarine. Most submarine deck guns were open, with or without a shield; however, a few larger submarines placed these guns in a turret.

The main deck gun was a dual-purpose ...

. Three days later, the British collier '' Primo'' suffered the same fate. These two ships were the first vessels to be sunk in the restricted German submarine offensive against British and French merchant shipping.

At the beginning of 1915, Hersing received the

At the beginning of 1915, Hersing received the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

, 2nd Class, and was ordered to extend German submarine warfare to the western coast of the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

. On 21 January, he sailed from Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsh ...

and entered the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Ce ...

, where he tried to shell the airfield on Walney Island

Walney Island, also known as the Isle of Walney, is an island off the west coast of England, at the western end of Morecambe Bay in the Irish Sea. It is part of Barrow-in-Furness, separated from the mainland by Walney Channel, which is spanned b ...

, but had no success. On 30 January ''U-21'' met and sank three merchant ships, ''Ben Cruachan

Ben Cruachan ( gd, Cruachan Beann) is a mountain that rises to , the highest in Argyll and Bute, Scotland. It gives its name to the Cruachan Dam, a pumped-storage hydroelectric

Pumped-storage hydroelectricity (PSH), or pumped hydroelectric ...

'', '' Linda Blanche'' and '' Kilcuan''. In every case, Hersing respected the prize rules, helping the crew of the intercepted ships. He then sailed back to Germany and at the beginning of February docked in Wilhelmshaven, having passed through the Dover Barrage

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidston ...

without consequences for the second time in a short while.

Operations in the Mediterranean and the Dardanelles

Hersing was ordered in April to transfer to theMediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

to support the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, allied to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and under attack of British and French troops at the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

. He sailed with ''U-21'' from Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

on 25 April and arrived at the Austro-Hungarian port of Cattaro

Kotor (Montenegrin Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a coastal town in Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,510 and is the administrative ...

after eighteen days. Due to a problem in refueling, Hersing was forced to slow down his submarine and proceed part of the way on the surface, exposing it to the risk of being detected by Allied units.

After a week in the friendly port, Hersing sailed to his new operational area off Gallipoli, which he reached on 25 May. The same day, he spotted the British battleship HMS ''Triumph''. Hersing brought his U-boat to within 300 yards (270 m) of his target and fired a single torpedo, which hit the battleship and caused it to capsize and sink, causing the death of 3 officers and 75 members of the crew. After the action, ''Kapitänleutnant'' Hersing took his submarine to the seafloor and waited there for 28 hours before resurfacing to recharge the electric batteries.

On 27 May, ''U-21'' sank her second Allied battleship in the Dardanelles, the ''Majestic''. Hersing was able to avoid the escorting vessels and the

After a week in the friendly port, Hersing sailed to his new operational area off Gallipoli, which he reached on 25 May. The same day, he spotted the British battleship HMS ''Triumph''. Hersing brought his U-boat to within 300 yards (270 m) of his target and fired a single torpedo, which hit the battleship and caused it to capsize and sink, causing the death of 3 officers and 75 members of the crew. After the action, ''Kapitänleutnant'' Hersing took his submarine to the seafloor and waited there for 28 hours before resurfacing to recharge the electric batteries.

On 27 May, ''U-21'' sank her second Allied battleship in the Dardanelles, the ''Majestic''. Hersing was able to avoid the escorting vessels and the torpedo net

Torpedo nets were a passive ship defensive device against torpedoes. They were in common use from the 1890s until the Second World War. They were superseded by the anti-torpedo bulge and torpedo belts.

Origins

With the introduction of the White ...

s that surrounded the ship, and the ''Majestic'' sunk within four minutes of being hit off Cape Helles

Cape Helles is the rocky headland at the southwesternmost tip of the Gallipoli peninsula, Turkey. It was the scene of heavy fighting between Ottoman Turkish and British troops during the landing at Cape Helles at the beginning of the Gallipoli c ...

, causing the death of at least 40 members of the crew (many of them were trapped in the defensive nets that were supposed to protect the ship)

Hersing's successes forced the Allies to withdraw all major ships from Cape Helles, and Great Britain offered a 100,000 pound reward for the capture of the German commander. On 5 June Hersing received the ''Pour le Mérite

The ' (; , ) is an order of merit (german: Verdienstorden) established in 1740 by King Frederick II of Prussia. The was awarded as both a military and civil honour and ranked, along with the Order of the Black Eagle, the Order of the Red Eag ...

'', the highest German military honor, as a recognition of his success in the Mediterranean. In the same year, 1915, he was awarded honorary citizenship of the German town of Bad Kreuznach, and he began to be nicknamed ''Zerstörer von Schlachtschiffen'' (destroyer of battleships).

The ''U-21'' crew spent a month in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

, due to needed repairs to their submarine. In the Ottoman capital, they received a great welcome and were treated as heroes. Once the repair work was finished, ''U-21'' sortied through the Dardanelles for another patrol. Hersing found the Allied munitions ship ''Carthage'' and sank her with a single torpedo on 4 July. Right after that, the submarine was forced to return to Constantinople after bumping an anti-submarine mine that did not cause serious damage. The boat then served briefly in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

, but with no results. It then returned to the Mediterranean, where in September Hersing found out that the Allies had established a complete blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

of the Dardanelles, using mines and nets in order to prevent enemy submarines to operate in that area.

Hersing therefore returned to Cattaro and received orders to help the Austro-Hungarian Navy in her fight against the Italian Regia Marina

The ''Regia Marina'' (; ) was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy (''Regno d'Italia'') from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the ''Regia Marina'' changed its name to ''Marina Militare'' ("M ...

. ''U-21'' and her crew were commissioned into the ''k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'' and the boat received the designation ''U-36''. This was necessary to allow the submarine to operate against the Italian merchant fleet, since Germany was not yet legally at war with the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and f ...

. The boat served under this name until Italy declared war on Germany on 27 August 1916. In February 1916, Hersing sank the British steamer '' Belle of France'', then the French armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

'' Amiral Charner'', intercepted off the Syrian coast, which caused the death of 427 crew members. Between April and October 1916, ''U-36'' sank numerous merchant ships, including the British steamer '' City of Lucknow'' (3,677 tons, sunk near Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

on April 30), three small Italian ships (intercepted near Corsica between October 26 and 28) and the steamboat '' SS Glenlogan'' (5,800 tons, October 31). In the first three days of November, Hersing's boat, positioned north of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, sank four more Italian ships, for a total of almost 2,500 tons overall. On 23 December, the German submarine met near Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

the British steamer '' Benalder'' and hit her with a torpedo, but she managed to escape and reach Alexandria. In 1916, ''U-36'' sank a total of 12 ships for more than 24,000 tons overall.

Return to the North Sea

At the beginning of 1917, Hersing left the Mediterranean to support theunrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules (also known as "cruiser rules") that call for warships to s ...

campaign of the German ''Seekriegsleitung

The ''Seekriegsleitung'' or SKL (Maritime Warfare Command) was a higher command staff section of the Kaiserliche Marine and the Kriegsmarine of Germany during the World Wars.

World War I

The SKL was established on August 27, 1918, on the initiativ ...

''. Between 16 and 17 February, Hersing intercepted and sank two British merchant ships and two small Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

ones off the Portuguese coast. Four days later, it was the turn of the French freighter '' Cacique'' (2,917 tons), sunk in the Bay of Biscay.

On February 22, ''U-21'' arrived in the Celtic Sea

The Celtic Sea ; cy, Y Môr Celtaidd ; kw, An Mor Keltek ; br, Ar Mor Keltiek ; french: La mer Celtique is the area of the Atlantic Ocean off the southern coast of Ireland bounded to the east by Saint George's Channel; other limits includ ...

and finished off the Dutch steamer ''Bandoeng

Bandung ( su, ᮘᮔ᮪ᮓᮥᮀ, Bandung, ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of West Java. It has a population of 2,452,943 within its city limits according to the official estimates as at mid 2021, making it the fourth most ...

'', already damaged by another German submarine. The same day Hersing sank six more Allied ships, five of them Dutch (the largest of which being '' Noorderdijk'', over 7,000 tons) and one Norwegian ('' Normanna'', 2,900 tons). A seventh ship, ''Menado

Manado () is the capital city of the Indonesian province of North Sulawesi. It is the second largest city in Sulawesi after Makassar, with the 2020 Census giving a population of 451,916 distributed over a land area of 162.53 km2.Badan Pu ...

'' suffered severe damage, but avoided sinking. In just one day, Hersing sank a total of seven ships, totalling more than 33,000 tons.

Hersing then sailed into North Sea between Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

. On April 22, he sunk the steamers '' Giskö'' and '' Theodore William''. On April 29 and 30, he sank the Norwegian '' Askepot'' and the Russian bark ''Borrowdale

Borrowdale is a valley and civil parish in the English Lake District in the Borough of Allerdale in Cumbria, England. It lies within the historic county boundaries of Cumberland. It is sometimes referred to as ''Cumberland Borrowdale'' ...

''. In the same area, the British steamers ''Adansi

Adansi is the name of an Akan ethnic group inhabiting the Ashanti Region of Ghana. The capital of the Adansi is at Fomena. An Adansihene (king of Adansi) is still designated. The Adansi has seven paramountcies: the capital, Fomena, New Edubiase, ...

'' and ''Killarney

Killarney ( ; ga, Cill Airne , meaning 'church of sloes') is a town in County Kerry, southwestern Ireland. The town is on the northeastern shore of Lough Leane, part of Killarney National Park, and is home to St Mary's Cathedral, Ross Cast ...

'' suffered the same fate on May 6 and 8, respectively. On June 27, Hersing sank the Swedish auxiliary barge ''Baltic'', carrying a cargo of timber.

Hersing's service in command of ''U-21'' ended in September 1918 when, two months before the Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

, he was assigned to the submarine navigation school at Eckernförde as an instructor.

During the war. Hersing was responsible for the sinking of 40 ships (36 merchantmen and four warships), for a total of more than 113,000 tons; this made him one of the most successful submarine commanders of the ''Kaiserliche Marine

{{italic title

The adjective ''kaiserlich'' means "imperial" and was used in the German-speaking countries to refer to those institutions and establishments over which the ''Kaiser'' ("emperor") had immediate personal power of control.

The term wa ...

''.

After the war

After the armistice, Hersing was given responsibility for the withdrawal of German troops from the city of Riga (in present Latvia). It is suspected that he subsequently was involved in the February 1919 sinking of ''U-21''. His former boat was surrendered to the Allies after the end of the war and sank under mysterious circumstances on 22 February 1919, during the transfer to Great Britain, where it should have formally surrendered. In 1920, he was probably involved in theKapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an attempted coup against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to undo th ...

, an attempted coup against the newly formed Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is ...

, but this had no consequences and he remained in the navy.

In 1922, he was promoted to ''Korvettenkapitän

() is the lowest ranking senior officer in a number of Germanic-speaking navies.

Austro-Hungary

Belgium

Germany

Korvettenkapitän, short: KKpt/in lists: KK, () is the lowest senior officer rank () in the German Navy.

Address

The off ...

'' (corvette captain), the highest rank that he attained in his career. His fame was still so great after the war that the French authorities offered a reward of 20,000 Marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

for his capture in the occupied Rhineland.

Hersing ended his military service in 1924 due to health reasons and moved with his wife to Rastede, a small town in Lower Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

, where he became a potato farmer. In 1932, he published his memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobiog ...

, ''U-21 rettet die Dardanellen'' ("U-21 saves the Dardanelles"). In 1935, he and his wife moved to Gremmendorf, a district of the city of Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state di ...

.

Hersing died in 1960 after a long illness; his grave is in the Angelmodde cemetery. The complete collection of his papers and writings is preserved in the ''Deutsches U-Boot Museum'' located in the Niedersachsen town of Altenbruch, in a room dedicated to his memory.

Awards

*Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

(1914)

** 2nd Class

** 1st Class

* ''Pour le Mérite

The ' (; , ) is an order of merit (german: Verdienstorden) established in 1740 by King Frederick II of Prussia. The was awarded as both a military and civil honour and ranked, along with the Order of the Black Eagle, the Order of the Red Eag ...

''

* Hanseatic Cross

The Hanseatic Cross (German: ''Hanseatenkreuz'') was a military decoration of the three Hanseatic city-states of Bremen, Hamburg and Lübeck, who were members of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 188 ...

of Lübeck

* Military Merit Order (Bavaria)

The Bavarian Military Merit Order (german: Militär-Verdienstorden) was established on 19 July 1866 by King Ludwig II of Bavaria. It was the kingdom's main decoration for bravery and military merit for officers and higher-ranking officials. Civi ...

* Albert Order (Saxony)

* U-Boat War Badge

The U-boat War Badge (german: U-Boot-Kriegsabzeichen) was a German war badge that was awarded to U-boat crew members during World War I and World War II.

History

The ''U-boat War Badge'' was originally instituted during the First World War on Feb ...

1918 version

* The Honour Cross of the World War 1914/1918

The Honour Cross of the World War 1914/1918 (german: Das Ehrenkreuz des Weltkrieges 1914/1918), commonly, but incorrectly, known as the Hindenburg Cross or the German WWI Service Cross was established by Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, Presiden ...

* Iron Crescent (Ottoman Empire)

See also

*Atlantic U-boat campaign of World War I

The Atlantic U-boat campaign of World War I (sometimes called the "First Battle of the Atlantic", in reference to the World War II campaign of that name) was the prolonged naval conflict between German submarines and the Allied navies in Atlan ...

* Battle of Gallipoli

References

Bibliography

* Dufeil, Yves (2011). Kaiserliche Marine U-Boote 1914-1918 - Dictionnaire biographique des commandants de la marine imperiale allemande iographic dictionary of the German Imperial Navy(in French). Histomar Publications. * Gibson, R.H.; Prendergast, M. (2002). The German Submarine War 1914-1918. Penzance: Periscope Publishing Ltd. . * Gilbert, Martin (2000). La grande storia della prima guerra mondiale orld War I(in Italian). Milan: Oscar Mondadori. . * Gray, Edwyn A. (1994). The U-Boat War: 1914–1918. London: L.Cooper. . * Hadley, Michael L. (1995). Count Not the Dead: The Popular Image of the German Submarine. Quebec City: McGill-Queen's University Press. . * Lowell, Thomas (2004). Raiders of the Deep. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. . * Sondhaus, Lawrence (2017). German Submarine Warfare in World War I: The Onset of Total War at Sea. Rowman and Littlefield. .External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hersing, Otto 1885 births 1960 deaths Military personnel from Mulhouse U-boat commanders (Imperial German Navy) Imperial German Navy personnel of World War I Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (military class) Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 1st class Recipients of the Iron Cross, 2nd class Recipients of the Hanseatic Cross