An oriental rug is a heavy textile made for a wide variety of utilitarian and symbolic purposes and produced in "

Oriental countries" for home use, local sale, and export.

Oriental carpets can be

pile woven or

flat woven without pile, using various materials such as silk, wool, and cotton. Examples range in size from pillows to large, room-sized carpets, and include carrier bags, floor coverings, decorations for animals, Islamic

prayer rug

A prayer rug or prayer mat is a piece of fabric, sometimes a pile carpet, used by Muslims, some Christians and some Baha'i during prayer.

In Islam, a prayer mat is placed between the ground and the worshipper for cleanliness during the various ...

s ('Jai'namaz'), Jewish Torah ark covers (''

parochet

A ''parochet'' (Hebrew: פרוכת; Ashkenazi pronunciation: ''paroches'') meaning "curtain" or "screen",Sonne Isaiah (1962) 'Synagogue' in The Interpreter's dictionary of the Bible vol 4, New York: Abingdon Press pp 476-491 is the curtain that ...

''), and Christian altar covers. Since the

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended ...

, oriental rugs have been an integral part of their cultures of origin, as well as of the European and, later on, the North American culture.

Geographically, oriental rugs are made in an area referred to as the “Rug Belt”, which stretches from Morocco across North Africa, the Middle East, and into Central Asia and northern India. It includes countries such as northern

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

,

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

,

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

,

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, the

Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

in the west, the

Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

in the north, and

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

in the south. Oriental rugs were also made in

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

from the early 1980s to mid 1990s in the village of Ilinge close to

Queenstown.

People from different cultures, countries, racial groups and religious faiths are involved in the production of oriental rugs. Since many of these countries lie in an area which today is referred to as the

Islamic world, oriental rugs are often also called “Islamic Carpets”,

and the term “oriental rug” is used mainly for convenience. The carpets from Iran are known as “

Persian Carpets

A Persian carpet ( fa, فرش ایرانی, translit=farš-e irâni ) or Persian rug ( fa, قالی ایرانی, translit=qâli-ye irâni ),Savory, R., ''Carpets'',(Encyclopaedia Iranica); accessed January 30, 2007. also known as Iranian ...

”.

[Savory, R., ''Carpets'',(]Encyclopaedia Iranica

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into article ...

); accessed January 30, 2007.

In 2010, the “traditional skills of carpet weaving” in the Iranian province of

Fārs, the Iranian town of

Kashan

Kashan ( fa, ; Qashan; Cassan; also romanized as Kāshān) is a city in the northern part of Isfahan province, Iran. At the 2017 census, its population was 396,987 in 90,828 families.

Some etymologists argue that the city name comes from ...

, and the “

traditional art of Azerbaijani carpet weaving

Azerbaijani carpet weaving ( az, Azərbaycan xalça toxuculuğu) is a historical and traditional activity of the Azerbaijani people. The Azerbaijani carpet is a traditional handmade textile of various sizes, with dense texture and a pile or pile- ...

” in the Republic of

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

" were inscribed to the

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists

UNESCO established its Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage with the aim of ensuring better protection of important intangible cultural heritages worldwide and the awareness of their significance.Compare: This list is published by the Intergover ...

.

The origin of the knotted pile rug

The beginning of carpet weaving remains unknown, as carpets are subject to use, deterioration, and destruction by insects and rodents. There is little archaeological evidence to support any theory about the origin of the pile-woven carpet. The earliest surviving carpet fragments are spread over a wide geographic area, and a long time span. Woven rugs probably developed from earlier floor coverings, made of

felt

Felt is a textile material that is produced by matting, condensing and pressing fibers together. Felt can be made of natural fibers such as wool or animal fur, or from synthetic fibers such as petroleum-based acrylic or acrylonitrile or wood ...

, or a technique known as "extra-weft wrapping". Flat-woven rugs are made by tightly interweaving the

warp

Warp, warped or warping may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Books and comics

* WaRP Graphics, an alternative comics publisher

* ''Warp'' (First Comics), comic book series published by First Comics based on the play ''Warp!''

* Warp (comics), a ...

and

weft

Warp and weft are the two basic components used in weaving to turn thread or yarn into fabric. The lengthwise or longitudinal warp yarns are held stationary in tension on a frame or loom while the transverse weft (sometimes woof) is draw ...

strands of the weave to produce a flat surface with no pile. The technique of weaving carpets further developed into a technique known as extra-weft wrapping weaving, a technique which produces

soumak

Soumak (also spelled Soumakh, Sumak, Sumac, or Soumac) is a tapestry technique of weaving sturdy, decorative fabrics used for rugs, domestic bags and bedding, with soumak fabrics used for bedding known as soumak mafrash.

Soumak is a type of flat ...

, and loop woven textiles. Loop weaving is done by pulling the weft strings over a gauge rod, creating loops of thread facing the weaver. The rod is then either removed, leaving the loops closed, or the loops are cut over the protecting rod, resulting in a rug very similar to a genuine pile rug. Typically, hand-woven

pile rug

A knotted-pile carpet is a carpet containing raised surfaces, or piles, from the cut off ends of knots woven between the warp and weft. The Ghiordes/Turkish knot and the Senneh/Persian knot, typical of Anatolian carpets and Persian carpets, are ...

s are produced by knotting strings of thread individually into the warps, cutting the thread after each single knot. The fabric is then further stabilized by weaving ("shooting") in one or more strings of weft, and compacted by beating with a comb. It seems likely that knotted-pile carpets have been produced by people who were already familiar with extra-weft wrapping techniques.

Historical evidence from ancient sources

Probably the oldest existing texts referring to carpets are preserved in

cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sha ...

writing on

clay tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a stylu ...

s from the royal archives of the kingdom of

Mari, from the 2nd millennium BC. The

Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabi ...

word for rug is ''mardatu'', and specialist rug weavers referred to as ''kāşiru'' are distinguished from other specialized professions like sack-makers (''sabsu'' or ''sabsinnu'').

Palace inventories from the archives of

Nuzi

Nuzi (or Nuzu; Akkadian Gasur; modern Yorghan Tepe, Iraq) was an ancient Mesopotamian city southwest of the city of Arrapha (modern Kirkuk), located near the Tigris river. The site consists of one medium-sized multiperiod tell and two small s ...

, from the 15th/14th century BC, record 20 large and 20 small ''mardatu'' to cover the chairs of

Idrimi

Idrimi was the king of Alalakh c. 1490–1465 BC, or around 1450 BC. He is known, mainly, from an inscription on his statue found at Alalakh by Leonard Woolley in 1939.Longman III, Tremper, (1991)Fictional Akkadian Autobiography: A Generic and Co ...

.

There are documentary records of carpets being used by the ancient Greeks.

Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

writes in

Ilias

Ilias may refer to:

* the ''Iliad'', an ancient Greek epos

* Ilias (name), a personal name (including a list of people with the name)

* ILIAS, a web-based learning management system

* 6604 Ilias, an asteroid

See also

* Profitis Ilias (disambig ...

XVII,350 that the body of Patroklos is covered with a “splendid carpet”. In

Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

Book VII and X “carpets” are mentioned.

Around 400 BC, the Greek author

Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, wikt:Ξενοφῶν, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Anci ...

mentions "carpets" in his book ''

Anabasis

Anabasis (from Greek ''ana'' = "upward", ''bainein'' = "to step or march") is an expedition from a coastline into the interior of a country. Anabase and Anabasis may also refer to:

History

* ''Anabasis Alexandri'' (''Anabasis of Alexander''), a ...

'':

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

wrote in (

nat. VIII, 48) that carpets (“polymita”) were invented in Alexandria. It is unknown whether these were flatweaves or pile weaves, as no detailed technical information is provided in the texts. Already the earliest known written sources refer to carpets as gifts given to, or required from, high-ranking persons.

Pazyryk: The first surviving pile rug

The oldest known hand knotted rug which is nearly completely preserved, and can, therefore, be fully evaluated in every technical and design aspect is the

Pazyryk carpet

The Pazyryk burials are a number of Scythian ( Saka) "The rich kurgan burials in Pazyryk, Siberia probably were those of Saka chieftains" "Analysis of the clothing, which has analogies in the complex of Saka clothes, particularly in Pazyryk, led ...

, dated to the 5th century BC. It was discovered in the late 1940s by the Russian archeologist Sergei Rudenko and his team.

The carpet was part of the grave gifts preserved frozen in ice in the

Scythian

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

burial mounds of the

Pazyryk area in the

Altai Mountains

The Altai Mountains (), also spelled Altay Mountains, are a mountain range in Central Asia, Central and East Asia, where Russia, China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan converge, and where the rivers Irtysh and Ob River, Ob have their headwaters. The m ...

of

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

[The State Hermitage Museum: The Pazyryk Carpet](_blank)

Hermitagemuseum.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-27. The provenience of the Pazyryk carpet is under debate, as many carpet weaving countries claim to be its country of origin.

[The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art: The debate on the origin of rugs and carpets](_blank)

Books.google.com. Retrieved on 2015-07-07. The carpet had been dyed with plant and insect dyes from the Mongolian steppes. Wherever it was produced, its fine weaving in symmetric knots and elaborate pictorial design hint at an advanced state of the art of carpet weaving at the time of its production. The design of the carpet already shows the basic arrangement of what was to become the standard oriental carpet design: A field with repeating patterns, framed by a main border in elaborate design, and several secondary borders.

Fragments from Turkestan, Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan

The explorer

Mark Aurel Stein

Sir Marc Aurel Stein,

( hu, Stein Márk Aurél; 26 November 1862 – 26 October 1943) was a Hungarian-born British archaeologist, primarily known for his explorations and archaeological discoveries in Central Asia. He was also a professor at ...

found flat-woven

kilim

A kilim ( az, Kilim کیلیم; tr, Kilim; tm, Kilim; fa, گلیم ''Gilīm'') is a flat tapestry- woven carpet or rug traditionally produced in countries of the former Persian Empire, including Iran, the Balkans and the Turkic countries. Ki ...

s dating to at least the fourth or fifth century AD in

Turpan

Turpan (also known as Turfan or Tulufan, , ug, تۇرپان) is a prefecture-level city located in the east of the autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. It has an area of and a population of 632,000 (2015).

Geonyms

The original name of the cit ...

, East Turkestan, China, an area which still produces carpets today. Rug fragments were also found in the

Lop Nur

Lop Nur or Lop Nor (from a Mongolian name meaning "Lop Lake", where "Lop" is a toponym of unknown origin) is a former salt lake, now largely dried up, located in the eastern fringe of the Tarim Basin, between the Taklamakan and Kumtag deserts ...

area, and are woven in symmetrical knots, with 5-7 interwoven wefts after each row of knots, with a striped design, and various colours. They are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Carpet fragments dated to the third or fourth century BC were excavated from burial mounds at Bashadar in the

Ongudai District,

Altai Republic

The Altai Republic (; russian: Респу́блика Алта́й, Respublika Altay, ; Altai: , ''Altay Respublika''), also known as Gorno-Altai Republic, and colloquially, and primarily referred to in Russian to distinguish from the neighbour ...

,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

by S. Rudenko, the discoverer of the Pazyryk carpet. They show a fine weave of about 4650 asymmetrical

knots per square decimeter

Other fragments woven in symmetrical as well as asymmetrical knots have been found in

Dura-Europos

Dura-Europos, ; la, Dūra Eurōpus, ( el, Δούρα Ευρωπός, Doúra Evropós, ) was a Hellenistic, Parthian, and Roman border city built on an escarpment above the southwestern bank of the Euphrates river. It is located near the vill ...

in

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

,

and from the At-Tar caves in

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

,

dated to the first centuries AD.

These rare findings demonstrate that all the skills and techniques of dyeing and carpet weaving were already known in western Asia before the first century AD.

Fragments of pile rugs from findspots in north-eastern

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, reportedly originating from the province of

Samangan, have been carbon-14 dated to a time span from the turn of the second century to the early

Sasanian

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

period. Among these fragments, some show depictings of animals, like various stags (sometimes arranged in a procession, recalling the design of the Pazyryk carpet) or a winged mythical creature. Wool is used for warp, weft, and pile, the yarn is crudely spun, and the fragments are woven with the asymmetric knot associated with Persian and far-eastern carpets. Every three to five rows, pieces of unspun wool, strips of cloth and leather are woven in.

These fragments are now in the

Al-Sabah Collection in the Dar al-Athar al-Islamyya,

Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the nort ...

.

13th–14th century: The Konya and Fostat fragments; findings from Tibetan monasteries

In the early fourteenth century,

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

wrote about the central Anatolian province of "Turcomania" in his account of his

travels:

"The other classes are Greeks and Armenians, who reside in the cities and fortified places, and gain their living by commerce and manufacture. The best and handsomest carpets in the world are wrought here, and also silks of crimson and other rich colours. Amongst its cities are those of Kogni, Kaisariah, and Sevasta."

Coming from Persia, Polo travelled from Sivas to Kayseri.

Abu'l-Fida

Ismāʿīl b. ʿAlī b. Maḥmūd b. Muḥammad b. ʿUmar b. Shāhanshāh b. Ayyūb b. Shādī b. Marwān ( ar, إسماعيل بن علي بن محمود بن محمد بن عمر بن شاهنشاه بن أيوب بن شادي بن مروان ...

, citing

Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi

Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Mūsā ibn Saʿīd al-Maghribī ( ar, علي بن موسى المغربي بن سعيد) (1213–1286), also known as Ibn Saʿīd al-Andalusī, was an Arab geographer, historian, poet, and the most important collector o ...

refers to carpet export from Anatolian cities in the lte 13th century: “That's where Turkoman carpets are made, which are exported to all other countries”. He and the Moroccan merchant

Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berbers, Berber Maghrebi people, Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, ...

mention Aksaray as a major rug weaving center in the early-to-mid-14th century.

Pile woven Turkish carpets were found in

Konya

Konya () is a major city in central Turkey, on the southwestern edge of the Central Anatolian Plateau, and is the capital of Konya Province. During antiquity and into Seljuk times it was known as Iconium (), although the Seljuks also called it D ...

and

Beyşehir

Beyşehir () is a large town and district of Konya Province in the Akdeniz region of Turkey. The town is located on the southeastern shore of Lake Beyşehir and is marked to the west and the southwest by the steep lines and forests of the Taurus ...

in Turkey, and

Fostat

Fusṭāṭ ( ar, الفُسطاط ''al-Fusṭāṭ''), also Al-Fusṭāṭ and Fosṭāṭ, was the first capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, and the historical centre of modern Cairo. It was built adjacent to what is now known as Old Cairo b ...

in Egypt, and were dated to the 13th century, which corresponds to the Anatolian

Seljuq Seljuk or Saljuq (سلجوق) may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* Seljuk (warlord) (d ...

Period (1243–1302). Eight fragments were found in 1905 by F.R. Martin

in the

Alâeddin Mosque

The Alaaddin Mosque (Turkish: Alaaddin Cami) is the principal monument on Alaaddin Hill (Alaadin Tepesi) in the centre of Konya, Turkey. Part of the hilltop citadel complex that contained the Seljuk Palace, it served as the main prayer hall for ...

in Konya, four in the

Eşrefoğlu Mosque

Eşrefoğlu Mosque is a 13th-century mosque in Beyşehir, Konya Province, Turkey

It is situated north of the Beyşehir Lake

History

During the last years of Seljuks of Rum, various governors of Seljuks enjoyed a partial independency. The ...

in

Beyşehir

Beyşehir () is a large town and district of Konya Province in the Akdeniz region of Turkey. The town is located on the southeastern shore of Lake Beyşehir and is marked to the west and the southwest by the steep lines and forests of the Taurus ...

in Konya province by R.M. Riefstahl in 1925.

More fragments were found in

Fostat

Fusṭāṭ ( ar, الفُسطاط ''al-Fusṭāṭ''), also Al-Fusṭāṭ and Fosṭāṭ, was the first capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, and the historical centre of modern Cairo. It was built adjacent to what is now known as Old Cairo b ...

, today a suburb of the city of Cairo.

By their original size (Riefstahl reports a carpet up to long), the Konya carpets must have been produced in town manufactories, as looms of this size cannot be set up in a nomadic or village home. Where exactly these carpets were woven is unknown. The field patterns of the Konya carpets are mostly geometric, and small in relation to the carpet size. Similar patterns are arranged in diagonal rows: Hexagons with plain, or hooked outlines; squares filled with stars, with interposed kufic-like ornaments; hexagons in diamonds composed of rhomboids, rhomboids filed with stylized flowers and leaves. Their main borders often contain kufic ornaments. The corners are not “resolved”, which means that the border design is cut off, and does not continue around the corners. The colours (blue, red, green, to a lesser extent also white, brown, yellow) are subdued, frequently two shades of the same colour are opposed to each other. Nearly all carpet fragments show different patterns and ornaments.

The Beyşehir carpets are closely related to the Konya carpets in design and colour.

In contrast to the "animal carpets" of the following period, depictings of animals are rarely seen in the Seljuq carpet fragments. Rows of horned quadrupeds placed opposite to each other, or birds beside a tree can be recognized on some fragments. A near-complete carpet of this kind is now at the

Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

The Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) is a museum on one end of the Corniche in Doha, Qatar. As per the architect I. M. Pei's specifications, the museum is built on an island off an artificial projecting peninsula near the traditional '' dhow'' ha ...

. It has survived in a Tibetan monastery and was removed by monks fleeing to Nepal during the

Chinese cultural revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goal ...

.

The style of the Seljuq carpets finds parallels amongst the architectural decoration of contemporaneous mosques such as those at

Divriği

Divriği (formerly Tephrike, Greek: Τεφρική) is a small town and district of Sivas Province of Turkey. The town lies on gentle slope on the south bank of the Çaltısuyu river, a tributary of the Karasu river. The Great Mosque and Hospit ...

,

Sivas

Sivas (Latin and Greek: ''Sebastia'', ''Sebastea'', Σεβάστεια, Σεβαστή, ) is a city in central Turkey and the seat of Sivas Province.

The city, which lies at an elevation of in the broad valley of the Kızılırmak river, is a ...

, and

Erzurum

Erzurum (; ) is a city in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. It is the largest city and capital of Erzurum Province and is 1,900 meters (6,233 feet) above sea level. Erzurum had a population of 367,250 in 2010.

The city uses the double-headed eagle as ...

, and may be related to Byzantine art. The carpets are today at the

Mevlana Museum

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

in Konya, and at the

Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum

The Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum ( tr, ) is a museum located in Sultanahmet Square in Fatih district of Istanbul, Turkey. Constructed in 1524, the building was formerly the palace of Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha, who was the second grand vizier to S ...

in Istanbul.

Current understanding of the origin of pile-woven carpets

Knotted pile woven carpets were likely produced by people who were already familiar with extra-weft wrapping techniques. The different knot types in carpets from locations as distant from each other like the Pazyryk carpet (symmetric), the East Turkestan and Lop Nur (alternate single-weft knots), the At-Tar (symmetric, asymmetric, asymmetric loop knots), and the Fustat fragments (looped-pile, single, asymmetric knots) suggest that the technique as such may have evolved at different places and times.

It is also debated whether pile-knotted carpets were initially woven by nomads who tried to imitate animal pelts as tent-floor coverings,

or if they were a product of settled peoples. A number of knives was found in the graves of women of a settled community in southwest

Turkestan

Turkestan, also spelled Turkistan ( fa, ترکستان, Torkestân, lit=Land of the Turks), is a historical region in Central Asia corresponding to the regions of Transoxiana and Xinjiang.

Overview

Known as Turan to the Persians, western Turke ...

. The knives are remarkably similar to those used by Turkmen weavers for trimming the pile of a carpet. Some ancient motifs on Turkmen carpets closely resemble the ornaments seen on early pottery from the same region. The findings suggest that Turkestan may be among the first places we know of where pile-woven carpets were produced, but this does not mean it was the only place.

In the light of ancient sources and archaeological discoveries, it seems highly likely that the pile-woven carpet developed from one of the extra-weft wrapping weaving techniques, and was first woven by settled people. The technique has probably evolved separately at different places and times. During the migrations of nomadic groups from Central Asia, the technique and designs may have spread throughout the area which was to become the “rug belt” in later times. With the emergence of Islam, the westward migration of nomadic groups began to change Near Eastern history. After this period, knotted-pile carpets became an important form of art under the influence of Islam, and where the nomadic tribes spread, and began to be known as “Oriental” or “Islamic” carpets.

File:Pazyryk carpet.jpg, The Pazyryk Carpet

The Pazyryk burials are a number of Scythian ( Saka) "The rich kurgan burials in Pazyryk, Siberia probably were those of Saka chieftains" "Analysis of the clothing, which has analogies in the complex of Saka clothes, particularly in Pazyryk, led ...

. Circa 400 BC. Hermitage Museum

The State Hermitage Museum ( rus, Государственный Эрмитаж, r=Gosudarstvennyj Ermitaž, p=ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)ɨj ɪrmʲɪˈtaʂ, links=no) is a museum of art and culture in Saint Petersburg, Russia. It is the list of ...

File:Konya Ethnographical Museum - Carpet 1.png, Carpet fragment from Eşrefoğlu Mosque

Eşrefoğlu Mosque is a 13th-century mosque in Beyşehir, Konya Province, Turkey

It is situated north of the Beyşehir Lake

History

During the last years of Seljuks of Rum, various governors of Seljuks enjoyed a partial independency. The ...

, Beysehir, Turkey. Seljuq Period, 13th century.

File:Seljuk Carpet Fragment 13th Century..png, Seljuq carpet, , from Alâeddin Mosque, Konya, 13th century

File:Unknown, Turkey, 11th-13th Century - Carpet with Animal Design - Google Art Project.jpg, Animal carpet, Turkey, dated to the 11th–13th century, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

The Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) is a museum on one end of the Corniche in Doha, Qatar. As per the architect I. M. Pei's specifications, the museum is built on an island off an artificial projecting peninsula near the traditional '' dhow'' ha ...

Manufacture

An oriental rug is woven by hand on a loom, with warps, wefts, and pile made mainly of natural fibers like wool, cotton, and silk. In representative carpets, metal threads made of gold or silver are woven in. The pile consists of hand-spun or machine-spun strings of yarn, which are knotted into the warp and weft foundation. Usually the pile threads are dyed with various natural or synthetic dyes. Once the weaving has finished, the rug is further processed by fastening its borders, clipping the pile to obtain an even surface, and washing, which may use added chemical solutions to modify the colours.

Materials

Materials used in carpet weaving and the way they are combined vary in different rug weaving areas. Mainly, animal

wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As ...

from sheep and goats is used, occasionally also from camels. Yak and horse hair have been used in Far Eastern, but rarely in Middle Eastern rugs.

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

is used for the foundation of the rug, but also in the pile.

Silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

from

silk worms

The domestic silk moth (''Bombyx mori''), is an insect from the moth family Bombycidae. It is the closest relative of ''Bombyx mandarina'', the wild silk moth. The silkworm is the larva or caterpillar of a silk moth. It is an economically im ...

is used for representational rugs.

Wool

In most oriental rugs, the pile is of

sheep's wool. Its characteristics and quality vary from each area to the next, depending on the breed of sheep, climatic conditions, pasturage, and the particular customs relating to when and how the wool is shorn and processed. In the Middle East, rug wools come mainly from the

fat-tailed and fat-rumped sheep races, which are distinguished, as their names suggest, by the accumulation of fat in the respective parts of their bodies. Different areas of a sheep's fleece yield different qualities of wool, depending on the ratio between the thicker and stiffer sheep hair and the finer fibers of the wool. Usually, sheep are

shorn

Sheep shearing is the process by which the woollen fleece of a sheep is cut off. The person who removes the sheep's wool is called a '' shearer''. Typically each adult sheep is shorn once each year (a sheep may be said to have been "shorn" or ...

in spring and fall. The spring shear produces wool of finer quality. The lowest grade of wool used in carpet weaving is “skin” wool, which is removed chemically from dead animal skin.

Fibers from

camel

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. C ...

s and

goat

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a domesticated species of goat-antelope typically kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the a ...

s are also used. Goat hair is mainly used for fastening the borders, or selvages, of

Baluchi and

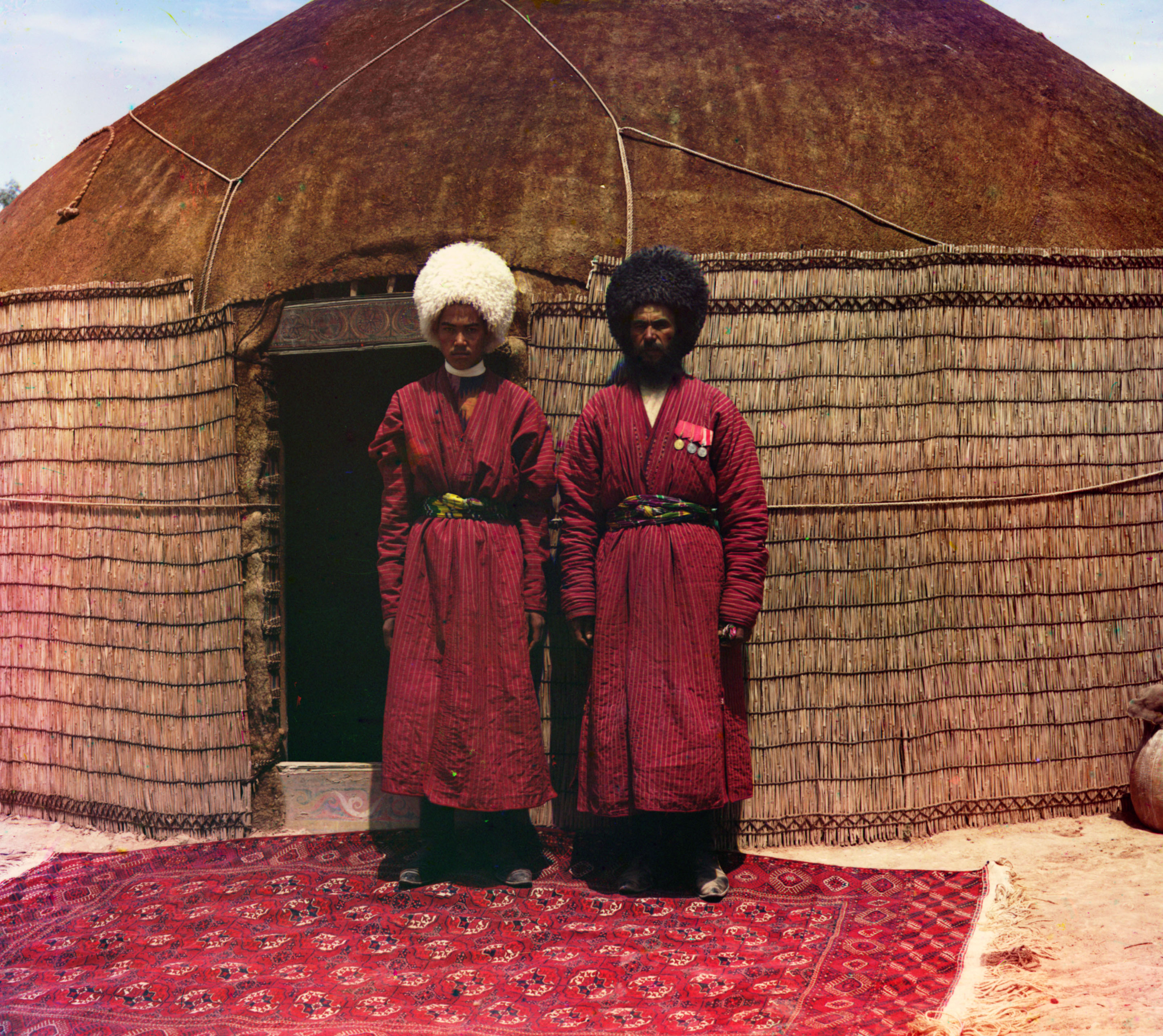

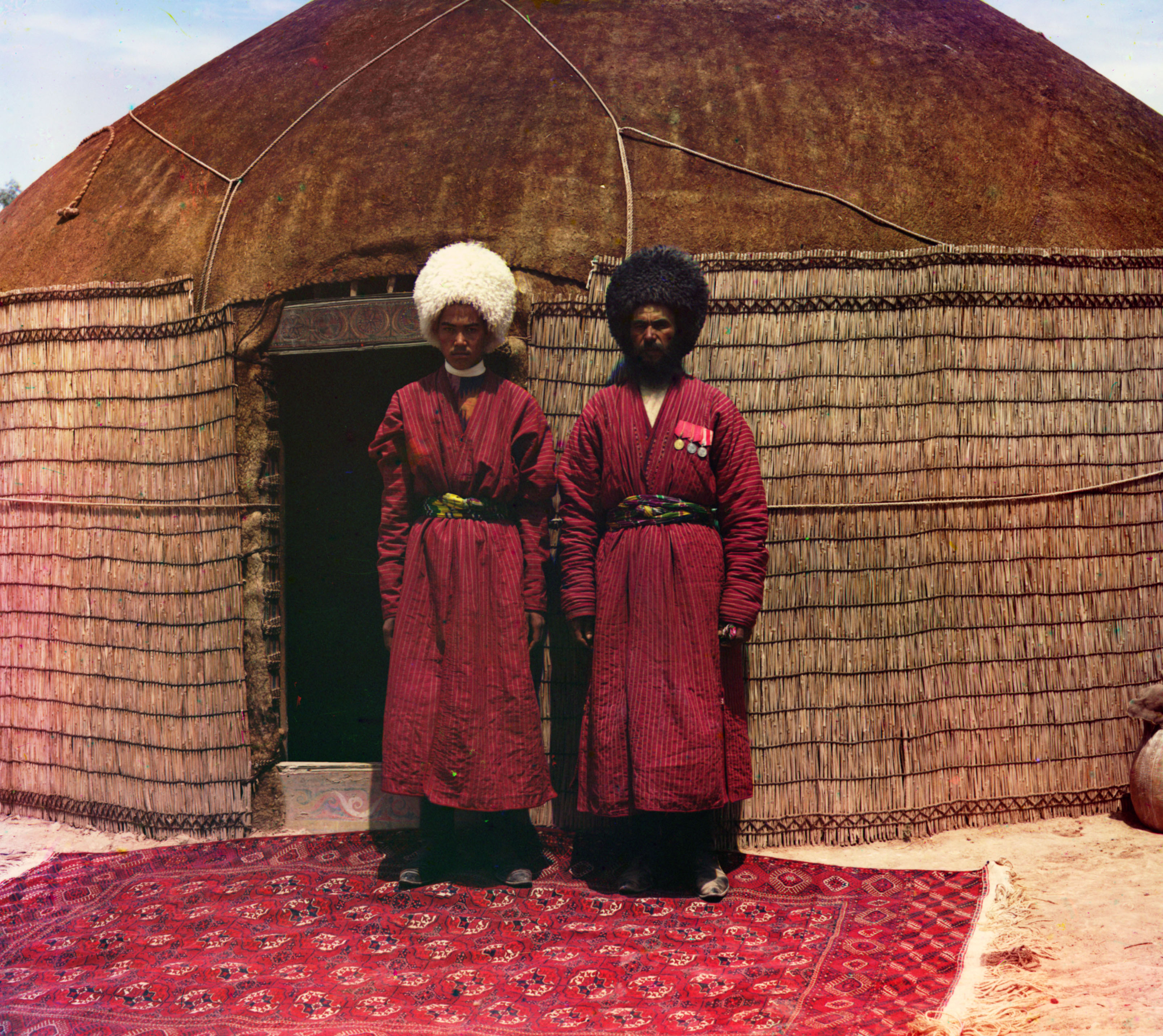

Turkmen rug

A Turkmen rug ( tk, Türkmen haly; or Turkmen carpet or Turkoman carpet) is a type of handmade floor-covering textile traditionally originating in Central Asia. It is useful to distinguish between the original Turkmen tribal rugs and the rugs pr ...

s, since it is more resistant to abrasion. Camel wool is occasionally used in Middle Eastern rugs. It is often dyed in black, or used in its natural colour. More often, wool said to be camel's wool turns out to be dyed sheep wool.

Cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

forms the foundation of warps and wefts of the majority of modern rugs. Nomads who cannot afford to buy cotton on the market use wool for warps and wefts, which are also traditionally made of wool in areas where cotton was not a local product. Cotton can be spun more tightly than wool, and tolerates more tension, which makes cotton a superior material for the foundation of a rug. Especially larger carpets are more likely to lie flat on the floor, whereas wool tends to shrink unevenly, and carpets with a woolen foundation may buckle when wet.

Chemically treated (

mercerised) cotton has been used in rugs as a silk substitute since the late nineteenth century.

Silk

Silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

is an expensive material, and has been used for representative carpets of the Mamluk, Ottoman, and Safavid courts. Its tensile strength has been used in silk warps, but silk also appears in the carpet pile. Silk pile can be used to highlight special elements of the design in

Turkmen rug

A Turkmen rug ( tk, Türkmen haly; or Turkmen carpet or Turkoman carpet) is a type of handmade floor-covering textile traditionally originating in Central Asia. It is useful to distinguish between the original Turkmen tribal rugs and the rugs pr ...

s, but more expensive carpets from Kashan, Qum, Nain, and Isfahan in Persia, and Istanbul and Hereke in Turkey, have all-silk piles. Silk pile carpets are often exceptionally fine, with a short pile and an elaborate design. Silk pile is less resistant to mechanical stress, thus, all-silk piles are often used as wall hangings, or pillow tapestry. Silk is more often used in rugs of Eastern Turkestan and Northwestern China, but these rugs tend to be more coarsely woven.

Spinning

The fibers of wool, cotton, and silk are spun either by hand or mechanically by using

spinning wheel

A spinning wheel is a device for spinning thread or yarn from fibres. It was fundamental to the cotton textile industry prior to the Industrial Revolution. It laid the foundations for later machinery such as the spinning jenny and spinning f ...

s or industrial

spinning machines to produce the yarn. The direction in which the yarn is spun is called ''twist''. Yarns are characterized as S-twist or Z-twist according to the direction of spinning (see diagram). Two or more spun yarns may be twisted together or ''

plied

In the textile arts, plying (from the French verb ''plier'', "to fold", from the Latin verb ''plico'', from the ancient Greek verb .) is a process of twisting one or more strings (called strands) of yarn together to create a stronger yarn. Strands ...

'' to form a thicker yarn. Generally, handspun single plies are spun with a Z-twist, and plying is done with an S-twist. With the exception of Mamluk carpets, nearly all the rugs produced in the countries of the rug belt use "Z" (anti-clockwise) spun and "S" (clockwise)-plied wool.

Dyeing

The dyeing process involves the preparation of the yarn in order to make it susceptible for the proper dyes by immersion in a

mordant

A mordant or dye fixative is a substance used to set (i.e. bind) dyes on fabrics by forming a coordination complex with the dye, which then attaches to the fabric (or tissue). It may be used for dyeing fabrics or for intensifying stains in ...

. Dyestuffs are then added to the yarn which remains in the dyeing solution for a defined time. The dyed yarn is then left to dry, exposed to air and sunlight. Some colours, especially dark brown, require iron mordants, which can damage or fade the fabric. This often results in faster pile wear in areas dyed in dark brown colours, and may create a relief effect in antique oriental carpets.

Vegetal dyes

Traditional dyes used for oriental rugs are obtained from plants and insects. In 1856, the English chemist

William Henry Perkin

Sir William Henry Perkin (12 March 1838 – 14 July 1907) was a British chemist and entrepreneur best known for his serendipitous discovery of the first commercial synthetic organic dye, mauveine, made from aniline. Though he failed in trying ...

invented the first

aniline

Aniline is an organic compound with the formula C6 H5 NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the simplest aromatic amine. It is an industrially significant commodity chemical, as well as a versatile starti ...

dye,

mauveine

Mauveine, also known as aniline purple and Perkin's mauve, was one of the first synthetic dyes. It was discovered serendipitously by William Henry Perkin in 1856 while he was attempting to synthesise the phytochemical quinine for the treatment of ...

. A variety of other synthetic

dyes were invented thereafter. Cheap, readily prepared and easy to use as they were compared to natural dyes, their use is documented in oriental rugs since the mid 1860s. The tradition of natural dyeing was revived in Turkey in the early 1980s, and later on, in Iran.

Chemical analyses led to the identification of natural dyes from antique wool samples, and dyeing recipes and processes were experimentally re-created.

According to these analyzes, natural dyes used in Turkish carpets include:

* ''Red'' from

Madder (Rubia tinctorum) roots,

* ''Yellow'' from plants, including

onion (Allium cepa), several chamomile species (

Anthemis

''Anthemis'' is a genus of aromatic flowering plants in the family (biology), family Asteraceae, closely related to ''Chamaemelum'', and like that genus, known by the common name chamomile; some species are also called dog-fennel or mayweed. ''An ...

,

Matricaria chamomilla

''Matricaria chamomilla'' (synonym: ''Matricaria recutita''), commonly known as chamomile (also spelled camomile), German chamomile, Hungarian chamomile (kamilla), wild chamomile, blue chamomile, or scented mayweed, is an annual plant of the co ...

), and

Euphorbia

''Euphorbia'' is a very large and diverse genus of flowering plants, commonly called spurge, in the family Euphorbiaceae. "Euphorbia" is sometimes used in ordinary English to collectively refer to all members of Euphorbiaceae (in deference to t ...

,

* ''Black'':

Oak apple

Oak apple or oak gall is the common name for a large, round, vaguely apple-like gall commonly found on many species of oak. Oak apples range in size from in diameter and are caused by chemicals injected by the larva of certain kinds of gall ...

s,

Oak acorns,

Tanner's sumach,

* ''Green'' by double dyeing with

Indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', m ...

and yellow dye,

* ''Orange'' by double dyeing with madder red and yellow dye,

* ''Blue'': Indigo gained from

Indigofera tinctoria

''Indigofera tinctoria'', also called true indigo, is a species of plant from the bean family that was one of the original sources of indigo dye.

Description

True indigo is a shrub one to two meters high. It may be an annual plant, annual, bi ...

.

Some of the dyestuffs like indigo or madder were goods of trade, and thus commonly available. Yellow or brown dyestuffs more substantially vary from region to region. In some instances, the analysis of the dye has provided information about the provenience of a rug. Many plants provide yellow dyes, like Vine weld, or Dyer's weed ''(

Reseda luteola

''Reseda luteola'' is a plant species in the genus '' Reseda''. Common names include dyer's rocket, dyer's weed, weld, woold, and yellow weed. A native of Europe and Western Asia, the plant can be found in North America as an introduced species an ...

)'', Yellow larkspur (perhaps identical with the ''isparek'' plant), or Dyer's sumach

Cotinus coggygria. Grape leaves and pomegranate rinds, as well as other plants, provide different shades of yellow.

Insect reds

Carmine dyes are obtained from resinous secretions of scale insects such as the

Cochineal

The cochineal ( , ; ''Dactylopius coccus'') is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the natural dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessile parasite native to tropical and subtropical South America through North Americ ...

scale

Coccus cacti

The cochineal ( , ; ''Dactylopius coccus'') is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the natural dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessile parasite native to tropical and subtropical South America through North America ...

, and certain Porphyrophora species (

Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

and

Polish cochineal). Cochineal dye, the so-called "laq" was formerly exported from India, and later on from Mexico and the Canary Islands. Insect dyes were more frequently used in areas where

Madder (Rubia tinctorum) was not grown, like west and north-west Persia.

Kermes is another common red dye obtained from the crushed dried bodies of a female scale insect. This dye was considered by many in the Middle East to be one of the most valuable and important dyes.

Synthetic dyes

With modern synthetic

dyes, nearly every colour and shade can be obtained so that it is nearly impossible to identify, in a finished carpet, whether natural or artificial dyes were used. Modern carpets can be woven with carefully selected synthetic colours, and provide artistic and utilitarian value.

Abrash

The appearance of slight deviations within the same colour is called abrash (from Turkish ''abraş'', literally, “speckled, piebald”). Abrash is seen in traditionally dyed oriental rugs. Its occurrence suggests that a single weaver has likely woven the carpet, who did not have enough time or resources to prepare a sufficient quantity of dyed yarn to complete the rug. Only small batches of wool were dyed from time to time. When one string of wool was used up, the weaver continued with the newly dyed batch. Because the exact hue of colour is rarely met again when a new batch is dyed, the colour of the pile changes when a new row of knots is woven in. As such, the colour variation suggests a village or tribal woven rug, and is appreciated as a sign of quality and authenticity. Abrash can also be introduced on purpose into a pre-planned carpet design.

Dresden University of Technology

TU Dresden (for german: Technische Universität Dresden, abbreviated as TUD and often wrongly translated as "Dresden University of Technology") is a public research university, the largest institute of higher education in the city of Dresden, th ...

, Germany

File:Ghermezdaneh.JPG, Kermez (Coccus cacti

The cochineal ( , ; ''Dactylopius coccus'') is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the natural dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessile parasite native to tropical and subtropical South America through North America ...

) lice

File:Abrash.JPG, Section (central medallion) of a South Persian rug, probably Qashqai, late 19th century, showing irregular blue colours (abrash)

Tools

A variety of tools are needed for the construction of a handmade rug. A

loom

A loom is a device used to weave cloth and tapestry. The basic purpose of any loom is to hold the warp threads under tension to facilitate the interweaving of the weft threads. The precise shape of the loom and its mechanics may vary, but th ...

, a horizontal or upright framework, is needed to mount the vertical

warps into which the pile nodes are knotted. One or more shoots of horizontal

wefts are woven (“shot”) in after each row of knots in order to further stabilize the fabric.

Horizontal looms

Nomads usually use a horizontal loom. In its simplest form, two loom beams are fastened, and kept apart by stakes which are driven into the ground. The tension of the warps is maintained by driving wedges between the loom beams and the stakes. If the nomad journey goes on, the stakes are pulled out, and the unfinished rug is rolled up on the beams. The size of the loom beams is limited by the need to be easily transportable, thus, genuine nomad rugs are often small in size. In Persia, loom beams were mostly made of poplar, because poplar is the only tree which is easily available and straight.

The closer the warps are spanned, the more dense the rug can be woven. The width of a rug is always determined by the length of the loom beams. Weaving starts at the lower end of the loom, and proceeds towards the upper end.

Traditionally, horizontal looms were used by the

*

Kurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Ir ...

,

Afshari,

Qashqai,

Lurs

Lurs () are an Iranian people living in the mountains of western Iran. The four Luri branches are the Bakhtiari, Mamasani, Kohgiluyeh and Lur proper, who are principally linked by the Luri language.

Lorestan Province is named after the Lu ...

,

Baloch,

Turkmen and

Bakhtiari in Persia;

* Baloch and Turkmen in Afghanistan and Turkmenistan;

* Kurds and nomads (

Yörük) in Anatolia.

Vertical looms

The technically more advanced, stationary vertical looms are used in villages and town manufactures. The more advanced types of vertical looms are more comfortable, as they allow for the weavers to retain their position throughout the entire weaving process. In essence, the width of the carpet is limited by the length of the loom beams. While the dimensions of a horizontal loom define the maximum size of the rug which can be woven on it, on a vertical loom longer carpets can be woven, as the completed sections of the rugs can be moved to the back of the loom, or rolled up on a beam, as the weaving proceeds.

There are three general types of vertical looms, all of which can be modified in a number of ways: the fixed village loom, the

Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the List of largest cities of Iran, sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quri Chay, Quru River valley in Iran's historic Aze ...

or Bunyan loom, and the roller beam loom.

# The fixed village loom is used mainly in

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and consists of a fixed upper beam and a moveable lower or cloth beam which slots into two sidepieces. The correct tension of the warps is obtained by driving wedges into the slots. The weavers work on an adjustable plank which is raised as the work progresses.

# The Tabriz loom, named after the city of

Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the List of largest cities of Iran, sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quri Chay, Quru River valley in Iran's historic Aze ...

, is used in Northwestern Iran. The warps are continuous and pass around behind the loom. Warp tension is obtained with wedges. The weavers sit on a fixed seat and when a portion of the carpet has been completed, the tension is released, the finished section of the carpet is pulled around the lower beam and upwards on the back of the loom. The Tabriz type of vertical loom allows for weaving of carpets up to double the length of the loom.

# The roller beam loom is used in larger Turkish manufactures, but is also found in Persia and India. It consists of two movable beams to which the warps are attached. Both beams are fitted with ratchets or similar locking devices. Once a section of the carpet is completed, it is wound up on the lower beam. On a roller beam loom, any length of carpet can be produced. In some areas of Turkey several rugs are woven in series on the same warps, and separated from each other by cutting the warps after the weaving is finished.

The vertical loom enables weaving of larger rug formats. The most simple vertical loom, usually used in villages, has fixed beams. The length of the loom determines the length of the rug. As the weaving proceeds, the weavers' benches must be moved upwards, and fixed again at the new working height. Another type of loom is used in manufactures. The wefts are fixed and spanned on the beams, or, in more advanced types of looms, the wefts are spanned on a roller beam, which allows for any length of carpet to be woven, as the finished part of the carpet is rolled up on the roller beam. Thus, the weavers' benches always remain at the same height.

Other tools

Few essential tools are needed in carpet weaving: Knives are used to cut the yarn after the knot is made, a heavy instrument like a comb for beating in the wefts, and a pair of scissors for trimming off the ends of the yarn after each row of knots is finished. From region to region, they vary in size and design, and in some areas are supplemented by other tools. The weavers of Tabriz used a combined blade and hook. The hook projects from the end of the blade, and is used for knotting, instead of knotting with the fingers. Comb-beaters are passed through the warp strings to beat in the wefts. When the rug is completed, the pile is often shorn with special knives to obtain an even surface.

File:Izmir010.jpg, Horizontal nomad loom

File:Khotan-fabrica-alfombras-d09.jpg, Vertical factory loom seen from the back. Weaver sits down left.

File:Yun darağı.jpg, Comb beater

Warp, weft, pile

Warps and

wefts form the foundation of the carpet, the pile accounts for the design. Warps, wefts and pile may consist of any of these materials:

Rugs can be woven with their warp strings held back on different levels, termed sheds. This is done by pulling the wefts of one shed tight, separating the warps on two different levels, which leaves one warp on a lower level. The technical term is “one warp is depressed”. Warps can be depressed slightly, ore more tightly, which will cause a more or less pronounced rippling or “ridging” on the back of the rug. A rug woven with depressed warps is described as “double warped”. Central Iranian city rugs such as Kashan, Isfahan, Qom, and Nain have deeply depressed warps, which make the pile more dense, the rug is heavier than a more loosely woven specimen, and the rug lies more firmly on the floor. Kurdish

Bidjar carpets make most pronounced use of warp depression. Often their pile is further compacted by the use of a metal rod which is driven between the warps and hammered down on, which produces a dense and rigid fabric.

Knots

The pile knots are usually knotted by hand. Most rugs from Anatolia utilize the symmetrical

Turkish double knot. With this form of knotting, each end of the pile thread is twisted around two warp threads at regular intervals, so that both ends of the knot come up between two warp strings on one side of the carpet, opposite to the knot. The thread is then pulled downwards and cut with a knife.

Most rugs from other provenances use the asymmetric, or

Persian knot

A knotted-pile carpet is a carpet containing raised surfaces, or piles, from the cut off ends of knots woven between the warp and weft. The Ghiordes/Turkish knot and the Senneh/Persian knot, typical of Anatolian carpets and Persian carpets, are ...

. This knot is tied by winding a piece of thread around one warp, and halfway around the next warp, so that both ends of the thread come up at the same side of two adjacent strings of warp on one side of the carpet, opposite to the knot. The pile, i.e., the loose end of the thread, can appear on the left or right side of the warps, thus defining the terms “open to the left” or “open to the right”. Variances in the type of knots are significant, as the type of knot used in a carpet may vary on a regional, or tribal, basis. Whether the knots are open to the left or to the right can be determined by passing one's hands over the pile.

A variant knot is the so-called jufti knot, which is woven around four strings of warp, with each loop of one single knot tied around two warps. Jufti can be knotted symmetrically or asymmetrically, open to the left or right.

A serviceable carpet can be made with jufti knots, and jufti knots are sometimes used in large single-colour areas of a rug, for example in the field. However, as carpets woven wholly or partly with the jufti knot need only half the amount of pile yarn than traditionally woven carpets, their pile is less resistant to wear, and these rugs do not last long.

Another variant of knot is known from early Spanish rugs. The Spanish knot or single-warp knot, is tied around one single warp. Some of the rug fragments excavated by A. Stein in Turfan seem to be woven with a single knot. Single knot weavings are also known from

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

ian

Coptic

Coptic may refer to:

Afro-Asia

* Copts, an ethnoreligious group mainly in the area of modern Egypt but also in Sudan and Libya

* Coptic language, a Northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century

* Coptic alphabet ...

pile rugs.

Irregular knots sometimes occur, and include missed warps, knots over three or four warps, single warp knots, or knots sharing one warp, both symmetric and asymmetric. They are frequently found in Turkmen rugs, and contribute to the dense and regular structure of these rugs.

Diagonal, or offset knotting has knots in successive rows occupy alternate pairs of warps. This feature allows for changes from one half knot to the next, and creates diagonal pattern lines at different angles. It is sometimes found in Kurdish or Turkmen rugs, particularly in Yomuds. It is mostly tied symmetrically.

The upright pile of oriental rugs usually inclines in one direction, as knots are always pulled downwards before the string of pile yarn is cut off and work resumes on the next knot, piling row after row of knots on top of each other. When passing one's hand over a carpet, this creates a feeling similar to stroking an animal's fur. This can be used to determine where the weaver has started knotting the pile.

Prayer rug

A prayer rug or prayer mat is a piece of fabric, sometimes a pile carpet, used by Muslims, some Christians and some Baha'i during prayer.

In Islam, a prayer mat is placed between the ground and the worshipper for cleanliness during the various ...

s are often woven “upside down”, as becomes apparent when the direction of the pile is assessed. This has both technical reasons (the weaver can focus on the more complicated niche design first), and practical consequences (the pile bends in the direction of the worshipper's prostration).

Knot count

The knot count is expressed in knots per square inch (''kpsi'') or per square decimeter. Knot count per square decimeter can be converted to square inch by division by 15.5. Knot counts are best performed on the back of the rug. If the warps are not too deeply depressed, the two loops of one knot will remain visible, and will have to be counted as one knot. If one warp is deeply depressed, only one loop of the knot may be visible, which has to be considered when the knots are counted.

Compared to the kpsi counts, additional structural information is obtained when the horizontal and vertical knots are counted separately. In Turkmen carpets, the ratio between horizontal and vertical knots is frequently close to 1:1. Considerable technical skill is required to achieve this knot ratio. Rugs which are woven in this manner are very dense and durable.

Knot counts bear evidence of the fineness of the weaving, and of the amount of labour needed to complete the rug. However, the artistic and utilitarian value of a rug hardly depends on knot counts, but rather on the execution of the design and the colours. For example, Persian Heriz or some Anatolian carpets may have low knot counts as compared to the extremely fine-woven Qom or Nain rugs, but provide artistic designs, and are resistant to wear.

Finishing

Once the weaving is finished, the rug is cut from the loom. Additional work has to be done before the rug is ready for use.

Edges and ends

The edges of a rug need additional protection, as they are exposed to particular mechanical stress. The last warps on each side of the rug are often thicker than the inner warps, or doubled. The edge may consist of only one warp, or of a bundle of warps, and is attached to the rugs by weft shoots looping over it, which is termed an “overcast”. The edges are often further reinforced by encircling it in wool, goat's hair, cotton, or silk in various colours and designs. Edges thus reinforced are called selvedges, or ''shirazeh'' from the Persian word.

The remaining ends of the warp threads form the fringes that may be weft-faced, braided, tasseled, or secured in some other manner. Especially Anatolian village and nomadic rugs have flat-woven

kilim

A kilim ( az, Kilim کیلیم; tr, Kilim; tm, Kilim; fa, گلیم ''Gilīm'') is a flat tapestry- woven carpet or rug traditionally produced in countries of the former Persian Empire, including Iran, the Balkans and the Turkic countries. Ki ...

ends, made by shooting in wefts without pile at the beginning and end of the weaving process. They provide further protection against wear, and sometimes include pile-woven tribal signs or village crests.

Pile

The pile of the carpet is shorn with special knives (or carefully burned down) in order to remove excess pile and obtain an equal surface. In parts of Central Asia, a small sickle-shaped knife with the outside edge sharpened is used for pile shearing. Knives of this shape have been excavated from

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

sites in Turkmenistan (cited in). In some carpets, a relief effect is obtained by clipping the pile unevenly following the contours of the design. This feature is often seen in

Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

and

Tibetan

Tibetan may mean:

* of, from, or related to Tibet

* Tibetan people, an ethnic group

* Tibetan language:

** Classical Tibetan, the classical language used also as a contemporary written standard

** Standard Tibetan, the most widely used spoken dial ...

rugs.

Washing

Most carpets are washed before they are used or go to the market. The washing may be done with water and soap only, but more often chemicals are added to modify the colours. Various chemical washings were invented in New York, London, and other European centers. The washing often included chlorine bleach or sodium hydrosulfite. Chemical washings not only damage the wool fibers, but change the colours to an extent that some rugs had to be re-painted with different colours after the washing, as is exemplified by the so-called "American Sarouk" carpet.

Kilim

A kilim ( az, Kilim کیلیم; tr, Kilim; tm, Kilim; fa, گلیم ''Gilīm'') is a flat tapestry- woven carpet or rug traditionally produced in countries of the former Persian Empire, including Iran, the Balkans and the Turkic countries. Ki ...

end and fringes

Design

Oriental rugs are known for their richly varied designs, but common traditional characteristics identify the design of a carpet as “oriental”. With the exception of pile relief obtained by clipping the pile unevenly, rug design originates from a two-dimensional arrangement of knots in various colours. Each knot tied into a rug can be regarded as one "

pixel

In digital imaging, a pixel (abbreviated px), pel, or picture element is the smallest addressable element in a raster image, or the smallest point in an all points addressable display device.

In most digital display devices, pixels are the smal ...

" of a picture, which is composed by the arrangement of knot after knot. The more skilled the weaver or, as in manufactured rugs, the designer, the more elaborate the design.

Rectilinear and curvilinear design

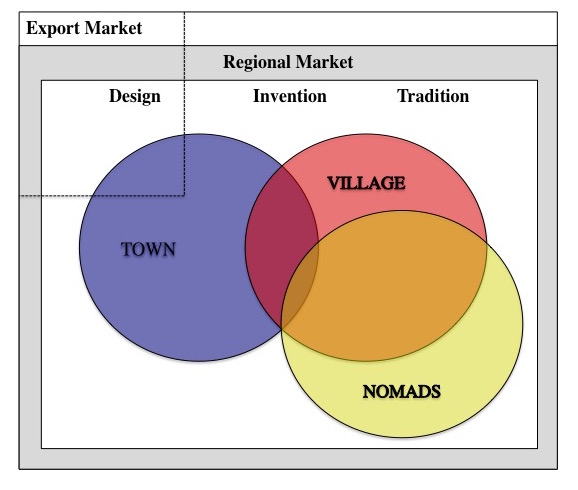

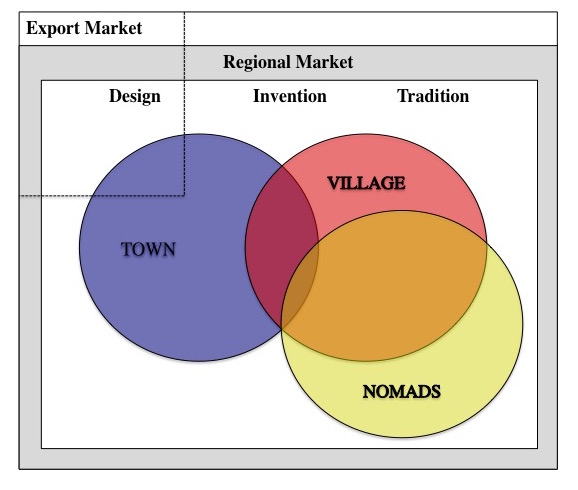

A rug design is described either as rectilinear (or “geometric”), or curvilinear (or “floral”). Curvilinear rugs show floral figures in a realistic manner. The drawing is more fluid, and the weaving is often more complicated. Rectilinear patterns tend to be bolder and more angular. Floral patterns can be woven in rectilinear design, but they tend to be more abstract, or more highly stylized. Rectilinear design is associated with nomadic or village weaving, whereas the intricate curvilinear designs require pre-planning, as is done in factories. Workshop rugs are usually woven according to a plan designed by an artist and handed over to the weaver to execute it on the loom.

Field design, medallions and borders

Rug design can also be described by how the surface of the rug is arranged and organized. One single, basic design may cover the entire field (“all-over design”). When the end of the field is reached, patterns may be cut off intentionally, thus creating the impression that they continue beyond the borders of the rug. This feature is characteristic for Islamic design: In the Islamic tradition, depicting animals or humans is

discouraged. Since the codification of the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

by

Uthman Ibn Affan

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic prop ...

in 651 AD/19 AH and the

Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan

Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ibn al-Hakam ( ar, عبد الملك ابن مروان ابن الحكم, ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān ibn al-Ḥakam; July/August 644 or June/July 647 – 9 October 705) was the fifth Umayyad caliph, ruling from April 685 ...

reforms,

Islamic art

Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations. Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide ra ...

has focused on writing and ornament. The main fields of Islamic rugs are frequently filled with redundant, interwoven ornaments in a manner called "infinite repeat".

Design elements may also be arranged more elaborately. One typical oriental rug design uses a medallion, a symmetrical pattern occupying the center of the field. Parts of the medallion, or similar, corresponding designs, are repeated at the four corners of the field. The common “Lechek Torūnj” (medallion and corner) design was developed in Persia for book covers and ornamental

book illuminations in the fifteenth century. In the sixteenth century, it was integrated into carpet designs. More than one medallion may be used, and these may be arranged at intervals over the field in different sizes and shapes. The field of a rug may also be broken up into different rectangular, square, diamond or lozenge shaped compartments, which in turn can be arranged in rows, or diagonally.

In Persian rugs, the medallion represents the primary pattern, and the infinite repeat of the field appears subordinated, creating an impression of the medallion “floating” on the field. Anatolian rugs often use the infinite repeat as the primary pattern, and integrate the medallion as secondary. Its size is often adapted to fit into the infinite repeat.

In most Oriental rugs, the field of the rug is surrounded by stripes, or borders. These may number from one up to over ten, but usually there is one wider main border surrounded by minor, or guardian borders. The main border is often filled with complex and elaborate rectilinear or curvilinear designs. The minor border stripes show simpler designs like meandering vines or reciprocal trefoils. The latter are frequently found in Caucasian and some Turkish rugs, and are related to the Chinese “cloud collar” (yun chien) motif.

The traditional border arrangement was highly conserved through time, but can also be modified to the effect that the field encroaches on the main border. Seen in Kerman rugs and Turkish rugs from the late eighteenth century "mecidi" period, this feature was likely taken over from French

Aubusson or

Savonnerie

The Savonnerie manufactory was the most prestigious European manufactory of knotted-pile carpets, enjoying its greatest period c. 1650–1685; the cachet of its name is casually applied to many knotted-pile carpets made at other centers. The manuf ...

weaving designs. Additional end borders called ''elem'', or skirts, are seen in Turkmen and some Turkish rugs. Their design often differs from the rest of the borders. Elem are used to protect the lower borders of tent door rugs ("ensi").

Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

and

Tibetan

Tibetan may mean:

* of, from, or related to Tibet

* Tibetan people, an ethnic group

* Tibetan language:

** Classical Tibetan, the classical language used also as a contemporary written standard

** Standard Tibetan, the most widely used spoken dial ...

rugs sometimes do not have any borders.

Designing the carpet borders becomes particularly challenging when it comes to the corner articulations. The ornaments have to be woven in a way that the pattern continues without interruption around the corners between horizontal and vertical borders. This requires advance planning either by a skilled weaver who is able to plan the design from start, or by a designer who composes a cartoon before the weaving begins. If the ornaments articulate correctly around the corners, the corners are termed to be “resolved”. In village or nomadic rugs, which are usually woven without a detailed advance plan, the corners of the borders are often not resolved. The weaver has discontinued the pattern at a certain stage, e.g., when the lower horizontal border is finished, and starts anew with the vertical borders. The analysis of the corner resolutions helps distinguishing rural village, or nomadic, from workshop rugs.

Smaller and composite design elements

The field, or sections of it, can also be covered with smaller design elements. The overall impression may be homogeneous, although the design of the elements themselves can be highly complicated. Amongst the repeating figures, the ''

boteh

The boteh ( fa, بته), is an almond or pine cone-shaped motif in ornament with a sharp-curved upper end. Though of Persian origin, it is very common and called buta in India, Azerbaijan, Turkey and other countries of the Near East. Via Kashm ...

'' is used throughout the “carpet belt”. Boteh can be depicted in curvilinear or rectilinear style. The most elaborate boteh are found in rugs woven around

Kerman

Kerman ( fa, كرمان, Kermân ; also romanization of Persian, romanized as Kermun and Karmana), known in ancient times as the satrapy of Carmania, is the capital city of Kerman Province, Iran. At the 2011 census, its population was 821,394, in ...

. Rugs from

Seraband, Hamadan, and Fars sometimes show the boteh in an all-over pattern. Other design elements include ancient motifs like the

Tree of life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythological, religious, and philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A History ...

, or floral and geometric elements like, e.g., stars or palmettes.

Single design elements can also be arranged in groups, forming a more complex pattern:

* The Herati pattern consists of a lozenge with floral figure at the corners surrounded by lancet-shaped leaves sometimes called “fish”. Herati patterns are used throughout the “carpet belt”; typically, they are found in the fields of

Bidjar rug

A Persian carpet ( fa, فرش ایرانی, translit=farš-e irâni ) or Persian rug ( fa, قالی ایرانی, translit=qâli-ye irâni ),Savory, R., ''Carpets'',(Encyclopaedia Iranica); accessed January 30, 2007. also known as Iranian ...

s.

* The Mina Khani pattern is made up of flowers arranged in a rows, interlinked by diamond (often curved) or circular lines. frequently all over the field. The Mina Khani design is often seen on

Varamin rugs.

* The Shah Abbasi design is composed of a group of palmettes. Shah Abbasi motifs are frequently seen in

Kashan

Kashan ( fa, ; Qashan; Cassan; also romanized as Kāshān) is a city in the northern part of Isfahan province, Iran. At the 2017 census, its population was 396,987 in 90,828 families.

Some etymologists argue that the city name comes from ...

,

Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its Achaemenid empire, ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in Sassanian Empire, middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Regio ...

,

Mashhad

Mashhad ( fa, مشهد, Mašhad ), also spelled Mashad, is the List of Iranian cities by population, second-most-populous city in Iran, located in the relatively remote north-east of the country about from Tehran. It serves as the capital of R ...

and

Nain rugs.

* The Bid Majnūn, or Weeping Willow design is in fact a combination of weeping willow, cypress, poplar and fruit trees in rectilinear form. Its origin was attributed to Kurdish tribes, as the earliest known examples are from the Bidjar area.

* The Harshang or Crab design takes its name from its principal motive, which is a large oval motive suggesting a crab. The pattern is found all over the rug belt, but bear some resemblance to palmettes from the Sefavi period, and the “claws” of the crab may be conventionalized arabesques in rectilinear style.

* The Gol Henai small repeating pattern is named after the Henna plant, which it does not much resemble. The plant looks more like the Garden balsam, and in the Western literature is sometimes compared to the blossom of the Horse chestnut.

* The

Gul design is frequently found in

Turkmen rug

A Turkmen rug ( tk, Türkmen haly; or Turkmen carpet or Turkoman carpet) is a type of handmade floor-covering textile traditionally originating in Central Asia. It is useful to distinguish between the original Turkmen tribal rugs and the rugs pr ...

s. Small round or octagonal medallions are repeated in rows all over the field. Although the Gül medallion itself can be very elaborate and colourful, their arrangement within the monochrome field often generates a stern and somber impression. Güls are often ascribed a heraldic function, as it is possible to identify the tribal provenience of a Turkmen rug by its güls.

Common motifs in Oriental rugs

File:Boteh.png, ''Boteh'' motif

File:Carpet Tree of Life.JPG, Pictorial carpet with Tree of life, birds, plants, flowers and vase motifs

File:Karaja 1103L4.jpg, Karaja carpet with ''Bid Majnūn'', or “weeping willow” design

File:Varamin Carpet.jpg, A Carpet from Varamin with the ''Mina Khani'' motif

File:Cloud band Hamburg MKG Safavid animal carpet detail.JPG, “Cloud band” ornament of Chinese origin in a Persian carpet