Nothomyrmecia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Nothomyrmecia'', also known as the dinosaur ant or dawn ant, is an extremely rare

''Nothomyrmecia'' is a medium-sized ant measuring in length. Workers are monomorphic, meaning that there is little morphological differentiation among one another. The mandibles, clypeus (one of the

''Nothomyrmecia'' is a medium-sized ant measuring in length. Workers are monomorphic, meaning that there is little morphological differentiation among one another. The mandibles, clypeus (one of the  Queens look similar to workers, but several morphological features distinguish the two castes from each other. The queen's body is usually larger.

Queens look similar to workers, but several morphological features distinguish the two castes from each other. The queen's body is usually larger.  The eggs of ''Nothomyrmecia'' are similar to those of ''Myrmecia'', being subspherical and non-adhesive. The larvae bear a primitive body structure with no specialised

The eggs of ''Nothomyrmecia'' are similar to those of ''Myrmecia'', being subspherical and non-adhesive. The larvae bear a primitive body structure with no specialised

The first collection of ''Nothomyrmecia'' was made in December 1931 by amateur entomologist, Amy Crocker, whose colleagues had collected a range of insect samples for her during a field excursion, including specimens of two worker ants, reportedly near the Russell Range, inland from Israelite Bay in Western Australia. Crocker then passed the ants to Australian entomologist John S. Clark. Recognised shortly afterwards as a new species, these specimens became the

The first collection of ''Nothomyrmecia'' was made in December 1931 by amateur entomologist, Amy Crocker, whose colleagues had collected a range of insect samples for her during a field excursion, including specimens of two worker ants, reportedly near the Russell Range, inland from Israelite Bay in Western Australia. Crocker then passed the ants to Australian entomologist John S. Clark. Recognised shortly afterwards as a new species, these specimens became the

In 2000, entomologist Cesare Baroni Urbani described a new Baltic fossil ''Prionomyrmex'' species (''P. janzeni''). After examining specimens of ''Nothomyrmecia'', Baroni Urbani stated that his new species and ''N. macrops'' were so morphologically similar that they belonged to the same genus. He proposed that the name ''Prionomyrmex'' should replace the name ''Nothomyrmecia'' (which would then be just a synonym), and also that the subfamily Nothomyrmeciinae should be called Prionomyrmeciinae.

In 2003, Russian palaeoentomologists G. M. Dlussky and E. B. Perfilieva separated ''Nothomyrmecia'' from ''Prionomyrmex'' on the basis of the fusion of an abdominal segment. In the same year, American entomologists P. S. Ward and S. G. Brady reached the same conclusion as Dlussky and Perfilieva and provided strong support for the

In 2000, entomologist Cesare Baroni Urbani described a new Baltic fossil ''Prionomyrmex'' species (''P. janzeni''). After examining specimens of ''Nothomyrmecia'', Baroni Urbani stated that his new species and ''N. macrops'' were so morphologically similar that they belonged to the same genus. He proposed that the name ''Prionomyrmex'' should replace the name ''Nothomyrmecia'' (which would then be just a synonym), and also that the subfamily Nothomyrmeciinae should be called Prionomyrmeciinae.

In 2003, Russian palaeoentomologists G. M. Dlussky and E. B. Perfilieva separated ''Nothomyrmecia'' from ''Prionomyrmex'' on the basis of the fusion of an abdominal segment. In the same year, American entomologists P. S. Ward and S. G. Brady reached the same conclusion as Dlussky and Perfilieva and provided strong support for the

''Nothomyrmecia'' is present in the cool regions of

''Nothomyrmecia'' is present in the cool regions of

Workers are nectarivores and can be found foraging on top of ''Eucalyptus'' trees, where they search for food and prey for the larvae. Workers are known to consume

Workers are nectarivores and can be found foraging on top of ''Eucalyptus'' trees, where they search for food and prey for the larvae. Workers are known to consume

Before its rediscovery in 1977, entomologists feared that ''Nothomyrmecia'' had already become extinct. The ant was listed as a protected species under the Western Australian Wildlife Conservation Act 1950. In 1996, the International Union for Conservation of Nature listed ''Nothomyrmecia'' as Critically Endangered, stating that only a few small colonies were known. The Threatened Species Scientific Committee states that the species is ineligible for listing under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. This is because there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate that populations are declining. Colonies are also naturally depauperate (lacking in numbers of ants), and their distribution is potentially quite extensive across southern Australia, due to the ants' preference for old-growth mallee woodland. With 18 sites known for this species, and the potential for many more being discovered, there seems little immediate possibility of extinction. With this said, it is unknown how widespread the species actually is, and scientists are not yet clear what, if any, threats affect it.

Suspected Anthropogenic hazard, anthropogenic threats that can significantly affect ''Nothomyrmecia'' include habitat destruction and Habitat fragmentation, fragmentation by railway lines, roads and wheat fields. In the town of Ceduna, west of Poochera, local populations of the ant were almost eliminated after the area was bulldozed and burned during the installation of an underground telephone line, although nearby sites had larger populations than those found in the destroyed site. Colonies may not survive tree-clearing, as they depend on overhead Canopy (biology), canopies to navigate. Wildfire, Bushfires are another major threat to the survival of ''Nothomyrmecia'', potentially destroying valuable food sources, including the trees they forage on, and reducing the population of a colony. These ants may have recovered from previous bushfires, but larger, more frequent fires may devastate the population. ''Nothomyrmecia'' ants can be safe from fires if they remain inside their nests. Climate change could be a threat to their survival, as they depend on cold temperatures to forage and collect food. An increase in the temperature will prevent workers from foraging, and very few areas would be suitable for the species to live in. The cold winds blowing off the Southern Ocean allow ''Nothomyrmecia'' to benefit from the cool temperatures they need for night-time foraging, so an increase in sea temperature could also potentially threaten it.

Conservationists suggest that conducting surveys, maintaining known populations through habitat protection and fighting climate change may ensure the survival of ''Nothomyrmecia''. They also advocate protection of remaining mallee habitat from degradation, and for management actions to improve tree and understorey structure. Because most known populations are found outside protected areas in vegetation alongside roads, a species management plan is required to identify other key actions, including making local councils aware of the presence, conservation status and habitat requirement of ''Nothomyrmecia''. This could result in future land use and management being decided more appropriately at the local level. Not all colonies are found in unprotected areas; some have been discovered in the Lake Gilles Conservation Park and the Chadinga Conservation Reserve. More research is needed to know the true extent of the ant's geographical distribution.

Before its rediscovery in 1977, entomologists feared that ''Nothomyrmecia'' had already become extinct. The ant was listed as a protected species under the Western Australian Wildlife Conservation Act 1950. In 1996, the International Union for Conservation of Nature listed ''Nothomyrmecia'' as Critically Endangered, stating that only a few small colonies were known. The Threatened Species Scientific Committee states that the species is ineligible for listing under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. This is because there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate that populations are declining. Colonies are also naturally depauperate (lacking in numbers of ants), and their distribution is potentially quite extensive across southern Australia, due to the ants' preference for old-growth mallee woodland. With 18 sites known for this species, and the potential for many more being discovered, there seems little immediate possibility of extinction. With this said, it is unknown how widespread the species actually is, and scientists are not yet clear what, if any, threats affect it.

Suspected Anthropogenic hazard, anthropogenic threats that can significantly affect ''Nothomyrmecia'' include habitat destruction and Habitat fragmentation, fragmentation by railway lines, roads and wheat fields. In the town of Ceduna, west of Poochera, local populations of the ant were almost eliminated after the area was bulldozed and burned during the installation of an underground telephone line, although nearby sites had larger populations than those found in the destroyed site. Colonies may not survive tree-clearing, as they depend on overhead Canopy (biology), canopies to navigate. Wildfire, Bushfires are another major threat to the survival of ''Nothomyrmecia'', potentially destroying valuable food sources, including the trees they forage on, and reducing the population of a colony. These ants may have recovered from previous bushfires, but larger, more frequent fires may devastate the population. ''Nothomyrmecia'' ants can be safe from fires if they remain inside their nests. Climate change could be a threat to their survival, as they depend on cold temperatures to forage and collect food. An increase in the temperature will prevent workers from foraging, and very few areas would be suitable for the species to live in. The cold winds blowing off the Southern Ocean allow ''Nothomyrmecia'' to benefit from the cool temperatures they need for night-time foraging, so an increase in sea temperature could also potentially threaten it.

Conservationists suggest that conducting surveys, maintaining known populations through habitat protection and fighting climate change may ensure the survival of ''Nothomyrmecia''. They also advocate protection of remaining mallee habitat from degradation, and for management actions to improve tree and understorey structure. Because most known populations are found outside protected areas in vegetation alongside roads, a species management plan is required to identify other key actions, including making local councils aware of the presence, conservation status and habitat requirement of ''Nothomyrmecia''. This could result in future land use and management being decided more appropriately at the local level. Not all colonies are found in unprotected areas; some have been discovered in the Lake Gilles Conservation Park and the Chadinga Conservation Reserve. More research is needed to know the true extent of the ant's geographical distribution.

''Nothomyrmecia'' at Arkive.org

{{Taxonbar, from=Q1207403 Myrmeciinae Critically endangered insects Hymenoptera of Australia Endemic fauna of Australia Endangered fauna of Australia Monotypic ant genera Mallee Woodlands and Shrublands

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of ant

Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cretaceous period. More than 13,800 of an estimated total of ...

s consisting of a single species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

, ''Nothomyrmecia macrops''. These ants live in South Australia, nesting in old-growth

An old-growth forestalso termed primary forest, virgin forest, late seral forest, primeval forest, or first-growth forestis a forest that has attained great age without significant disturbance, and thereby exhibits unique ecological feature ...

mallee woodland and ''Eucalyptus

''Eucalyptus'' () is a genus of over seven hundred species of flowering trees, shrubs or mallees in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae. Along with several other genera in the tribe Eucalypteae, including '' Corymbia'', they are commonly known as e ...

'' woodland. The full distribution of ''Nothomyrmecia'' has never been assessed, and it is unknown how widespread the species truly is; its potential range may be wider if it does favour old-growth mallee woodland. Possible threats to its survival include habitat destruction and climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

. ''Nothomyrmecia'' is most active when it is cold because workers encounter fewer competitors and predators such as '' Camponotus'' and ''Iridomyrmex

''Iridomyrmex'' is a genus of ants called rainbow ants (referring to their blue-green iridescent sheen) first described by Austrian entomologist Gustav Mayr in 1862. He placed the genus in the subfamily Dolichoderinae of the family Formici ...

'', and it also increases hunting success. Thus, the increase of temperature may prevent them from foraging and very few areas would be suitable for the ant to live in. As a result, the IUCN lists the ant as Critically Endangered.

As a medium-sized ant, ''Nothomyrmecia'' measures . Workers are monomorphic, showing little morphological differentiation among one another. Mature colonies are very small, with only 50 to 100 individuals in each nest. Workers are strictly nocturnal and are solitary foragers, collecting arthropod prey and sweet substances such as honeydew from scale insects and other Hemiptera. They rely on their vision to navigate and there is no evidence to suggest that the species use chemicals to communicate when foraging, but they do use chemical alarm signals. A queen ant will mate with one or more males and, during colony foundation, she will hunt for food until the brood have fully developed. Queens are univoltine

Voltinism is a term used in biology to indicate the number of broods or generations of an organism in a year. The term is most often applied to insects, and is particularly in use in sericulture, where silkworm varieties vary in their voltinism.

...

(they produce just one generation of ants each year). Two queens may establish a colony together, but only one will remain once the first generation of workers has been reared.

''Nothomyrmecia'' was first described by Australian entomologist John S. Clark in 1934 from two specimens of worker ants. These were reportedly collected in 1931 near the Russell Range, inland from Israelite Bay

Israelite Bay is a bay and locality on the south coast of Western Australia.

Situated in the Shire of Esperance local government area, it lies east of Esperance and the Cape Arid National Park, within the Nuytsland Nature Reserve and the Grea ...

in Western Australia. After its initial discovery, the ant was not seen again for four decades until a group of entomologists rediscovered it in 1977, away from the original reported site. Dubbed as the 'Holy Grail

The Holy Grail (french: Saint Graal, br, Graal Santel, cy, Greal Sanctaidd, kw, Gral) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miracu ...

' of myrmecology

Myrmecology (; from Greek: μύρμηξ, ''myrmex'', "ant" and λόγος, ''logos'', "study") is a branch of entomology focusing on the scientific study of ants. Some early myrmecologists considered ant society as the ideal form of society and ...

, the ant was subject to great scientific interest after its rediscovery, attracting scientists from around the world. In Poochera (the rediscovery site), pictures of the ant are stencilled on the streets, and it is perhaps the only town in the world that thrives off ant-based tourism. Some entomologists have suggested a relationship to the Baltic Eocene fossil ant genus '' Prionomyrmex'' based on morphological similarities, but this interpretation is not widely accepted by the entomological community. Owing to its body structure, ''Nothomyrmecia'' is regarded to be the most plesiomorphic ant alive and a 'living fossil

A living fossil is an extant taxon that cosmetically resembles related species known only from the fossil record. To be considered a living fossil, the fossil species must be old relative to the time of origin of the extant clade. Living foss ...

', stimulating studies on its morphology, behaviour, ecology, and chromosomes.

Description

''Nothomyrmecia'' is a medium-sized ant measuring in length. Workers are monomorphic, meaning that there is little morphological differentiation among one another. The mandibles, clypeus (one of the

''Nothomyrmecia'' is a medium-sized ant measuring in length. Workers are monomorphic, meaning that there is little morphological differentiation among one another. The mandibles, clypeus (one of the sclerite

A sclerite (Greek , ', meaning " hard") is a hardened body part. In various branches of biology the term is applied to various structures, but not as a rule to vertebrate anatomical features such as bones and teeth. Instead it refers most commonly ...

s that make up the "face" of an arthropod or insect), antennae and legs are pale yellow. The hairs on the body are yellow, erect and long and abundant, but on the antennae and legs they are shorter and suberect (standing almost in an erect position). It shows similar characteristics to ''Myrmecia

Myrmecia can refer to:

* ''Myrmecia'' (alga), genus of algae associated with lichens

* ''Myrmecia'' (ant), genus of ants called bulldog ants

* Myrmecia (skin), a kind of deep wart on the human hands or feet

See also

* '' Copromorpha myrmecias'' ...

'', and somewhat resembles '' Oecophylla'', commonly known as weaver ants. Workers are strictly nocturnal (active mainly at night) but navigate by vision, relying on large compound eyes

A compound eye is a visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens, and photoreceptor cells which distin ...

. The mandibles are shorter than the head. They have 10 to 15 intermeshing teeth and are less specialised than those of ''Myrmecia'' and '' Prionomyrmex'', being elongate and triangular. The head is longer than it is wide and broader towards the back. The sides of the head are convex around the eyes. The long antennal scapes (the base of the antenna) extend beyond the occipital border, and the second segment of the funiculus (a series of segments between the base and club

Club may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Club'' (magazine)

* Club, a '' Yie Ar Kung-Fu'' character

* Clubs (suit), a suit of playing cards

* Club music

* "Club", by Kelsea Ballerini from the album ''kelsea''

Brands and enterprises ...

) is slightly longer than the first, third and fourth segment. The node, pronotum

The prothorax is the foremost of the three segments in the thorax of an insect, and bears the first pair of legs. Its principal sclerites (exoskeletal plates) are the pronotum ( dorsal), the prosternum (ventral), and the propleuron (lateral) on e ...

, epinotum and thorax are longer than broad, and the mesonotum

The mesothorax is the middle of the three segments of the thorax of hexapods, and bears the second pair of legs. Its principal sclerites (exoskeletal plates) are the mesonotum (dorsal), the mesosternum (ventral), and the mesopleuron (lateral) on ...

is just as long as it is wide. The first segment of the gaster (the bulbous posterior portion of the metasoma

The metasoma is the posterior part of the body, or tagma, of arthropods whose body is composed of three parts, the other two being the prosoma and the mesosoma. In insects, it contains most of the digestive tract, respiratory system, and circul ...

) is broader than long by a third and broader at the back than the front with strongly convex sides.

A long and retractable stinger

A stinger (or sting) is a sharp organ found in various animals (typically insects and other arthropods) capable of injecting venom, usually by piercing the epidermis of another animal.

An insect sting is complicated by its introduction of ve ...

is present at the rear of the abdomen. It has been described as "prominent and effective" and is capable of inflicting a painful sting to humans. A 'sting bulb gland' is also present in ''Nothomyrmecia''; this is a small exocrine gland

Exocrine glands are glands that secrete substances on to an epithelial surface by way of a duct. Examples of exocrine glands include sweat, salivary, mammary, ceruminous, lacrimal, sebaceous, prostate and mucous. Exocrine glands are one of ...

of unknown function, first discovered and named in 1990. It is situated in the basal part of the insect's sting, and is located between the two ducts of the venom gland and the Dufour's gland

Dufour's gland is an abdominal gland of certain insects, part of the anatomy of the ovipositor or sting apparatus in female members of Apocrita. The diversification of Hymenoptera took place in the Cretaceous and the gland may have developed at a ...

. Despite its many plesiomorphic features, the sting apparatus of ''Nothomyrmecia'' is considered less primitive than those found in other ants such as '' Stigmatomma pallipes''. It is the only known species of ant that contains both a sting and a 'waist' (i.e. it has no postpetiole between the first and second gastral segments).

Queens look similar to workers, but several morphological features distinguish the two castes from each other. The queen's body is usually larger.

Queens look similar to workers, but several morphological features distinguish the two castes from each other. The queen's body is usually larger. Ocelli

A simple eye (sometimes called a pigment pit) refers to a form of eye or an optical arrangement composed of a single lens and without an elaborate retina such as occurs in most vertebrates. In this sense "simple eye" is distinct from a multi-l ...

are highly developed, but the eyes on the queen are not enlarged. The structure of the pterothorax (the wing-bearing area of the thorax) is consistent with other reproductive ants, but it does not occupy as much of its mesosomal bulk. The wings of the queens are rudimentary and stubby, barely overlapping the first gastral segment, and are brachypterous

Brachyptery is an anatomical condition in which an animal has very reduced wings. Such animals or their wings may be described as "brachypterous". Another descriptor for very small wings is microptery.

Brachypterous wings generally are not functi ...

(non-functional). Males resemble those of ''Myrmecia'', but ''Nothomyrmecia'' males bear a single waist node. The wings on the male ant are not stubby like a queen's; rather they are long and fully developed, exhibiting a primitive venational complement. They have a jugal anal lobe (a portion of the hindwing), a feature found in many primitive ants, and basal hamuli

A hamus or hamulus is a structure functioning as, or in the form of, hooks or hooklets.

Etymology

The terms are directly from Latin, in which ''hamus'' means "hook". The plural is ''hami''.

''Hamulus'' is the diminutive – hooklet or little h ...

(hook-like projections that link the forewings and hindwings). Most male specimens collected have two tibial spurs (spines located on the distal end of the tibia); the first spur is a long calcar

The calcar, also known as the calcaneum, is the name given to a spur of cartilage arising from inner side of ankle and running along part of outer interfemoral membrane in bats, as well as to a similar spur on the legs of some arthropods.

The ...

and the second spur is short and thick. Adults have a stridulatory organ on the ventral side of the abdomen – unlike all other hymenopterans in which such organs are located dorsally.

In all castes, these ants have six maxillary palp

Pedipalps (commonly shortened to palps or palpi) are the second pair of appendages of chelicerates – a group of arthropods including spiders, scorpions, horseshoe crabs, and sea spiders. The pedipalps are lateral to the chelicerae ("jaws") ...

s (palps that serve as organs of touch and taste in feeding) and four labial palps (sensory structures on the labium), a highly primitive feature. The females have a 12-segmented antenna, whereas males have 13 segments. Other features include paired calcariae found on both the hind and middle tibiae, and the claws have a median tooth. The unspecialised nature of the cuticle (outer exoskeleton of the body) is similar to ''Pseudomyrmex

''Pseudomyrmex'' is a genus of stinging, wasp-like ants in the subfamily Pseudomyrmecinae. They are large-eyed, slender ants, found mainly in tropical and subtropical regions of the New World.

Distribution and habitat

''Pseudomyrmex'' is predom ...

'', a member of the subfamily Pseudomyrmecinae

Pseudomyrmecinae is a small subfamily of ants containing only three genera of slender, large-eyed arboreal ants, predominantly tropical or subtropical in distribution. In the course of adapting to arboreal conditions (unlike the predominantly ...

. Many of the features known in ''Nothomyrmecia'' are found in Ponerinae and Pseudomyrmecinae.

The eggs of ''Nothomyrmecia'' are similar to those of ''Myrmecia'', being subspherical and non-adhesive. The larvae bear a primitive body structure with no specialised

The eggs of ''Nothomyrmecia'' are similar to those of ''Myrmecia'', being subspherical and non-adhesive. The larvae bear a primitive body structure with no specialised tubercle

In anatomy, a tubercle (literally 'small tuber', Latin for 'lump') is any round nodule, small eminence, or warty outgrowth found on external or internal organs of a plant or an animal.

In plants

A tubercle is generally a wart-like projection ...

s, sharing similar characteristics with the subfamily Ponerinae, but the sensilla are more abundant on the mouthparts. The larvae are characterised into three stages: very young, young, and mature, measuring , and , respectively. The cocoons have thin walls and produce meconium (a metabolic waste product expelled through the anal opening after an insect emerges from its pupal stage). The cuticular hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic, and their odors are usually weak or ...

s have internally branched alkenes

In organic chemistry, an alkene is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon double bond.

Alkene is often used as synonym of olefin, that is, any hydrocarbon containing one or more double bonds.H. Stephen Stoker (2015): General, Organic, an ...

, a feature rarely found in ants and most insects.

In general, the body structure of all ''Nothomyrmecia'' castes demonstrates the primitive nature of the species. Notable derived features include vestigial ocelli on workers, brachypterous queens, and the mesoscutal structure on males. The morphology of the abdomen, mandibles, gonoforceps (a sclerite, serving as the base of the ovipositors sheath) and basal hamuli show it is more primitive than ''Myrmecia''. The structure of the abdominal region can separate it from other Myrmeciinae relatives (the fourth abdominal segment of ''Myrmecia'' is tubulate, whereas ''Nothomyrmecia'' has a non-tubulated abdominal segment). The appearance of the fourth abdominal segment is consistent with almost all aculeate insects, and possibly ''Sphecomyrma

''Sphecomyrma'' is an extinct genus of ants which existed in the Cretaceous approximately 79 to 92 million years ago. The first specimens were collected in 1966, found embedded in amber which had been exposed in the cliffs of Cliffwood, New Jer ...

''.

The feature of non-functional, vestigial wings may have evolved in this species relatively recently, as wings might otherwise have long-since disappeared completely had they no function for dispersal. Wing-reduction could somehow relate to population structure or some other specialised ecological pressure. Equally, wing-reduction might be a feature that only forms in drought-stressed colonies, as has been observed in several ''Monomorium

''Monomorium'' is a genus of ants in the subfamily Myrmicinae. As of 2013 it contains about 396 species. It is distributed around the world, with many species native to the Old World tropics. It is considered to be "one of the more important gr ...

'' ant species found throughout semi-arid regions of Australia. As yet, scientists do not fully understand how the feature of non-functional, vestigial wings arose in ''Nothomyrmecia macrops''.

Taxonomy

Discovery

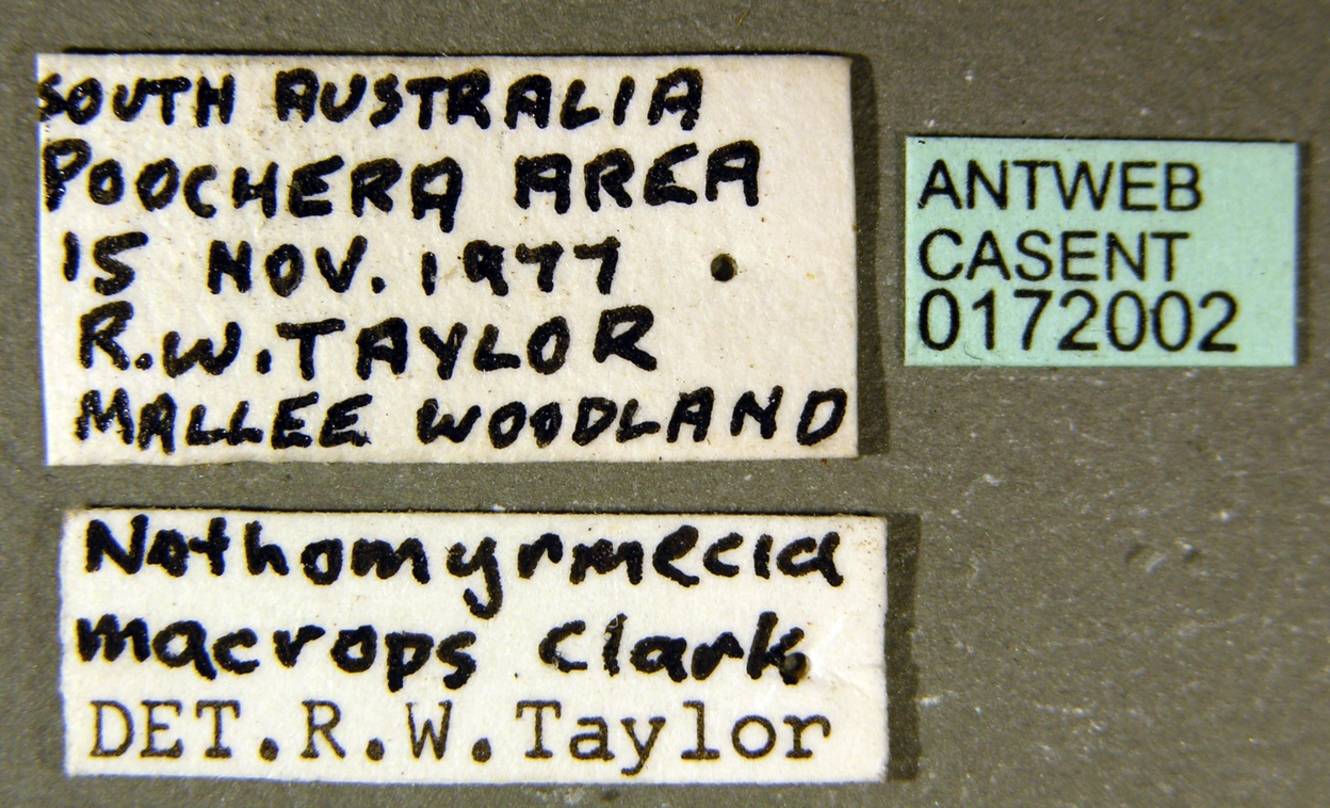

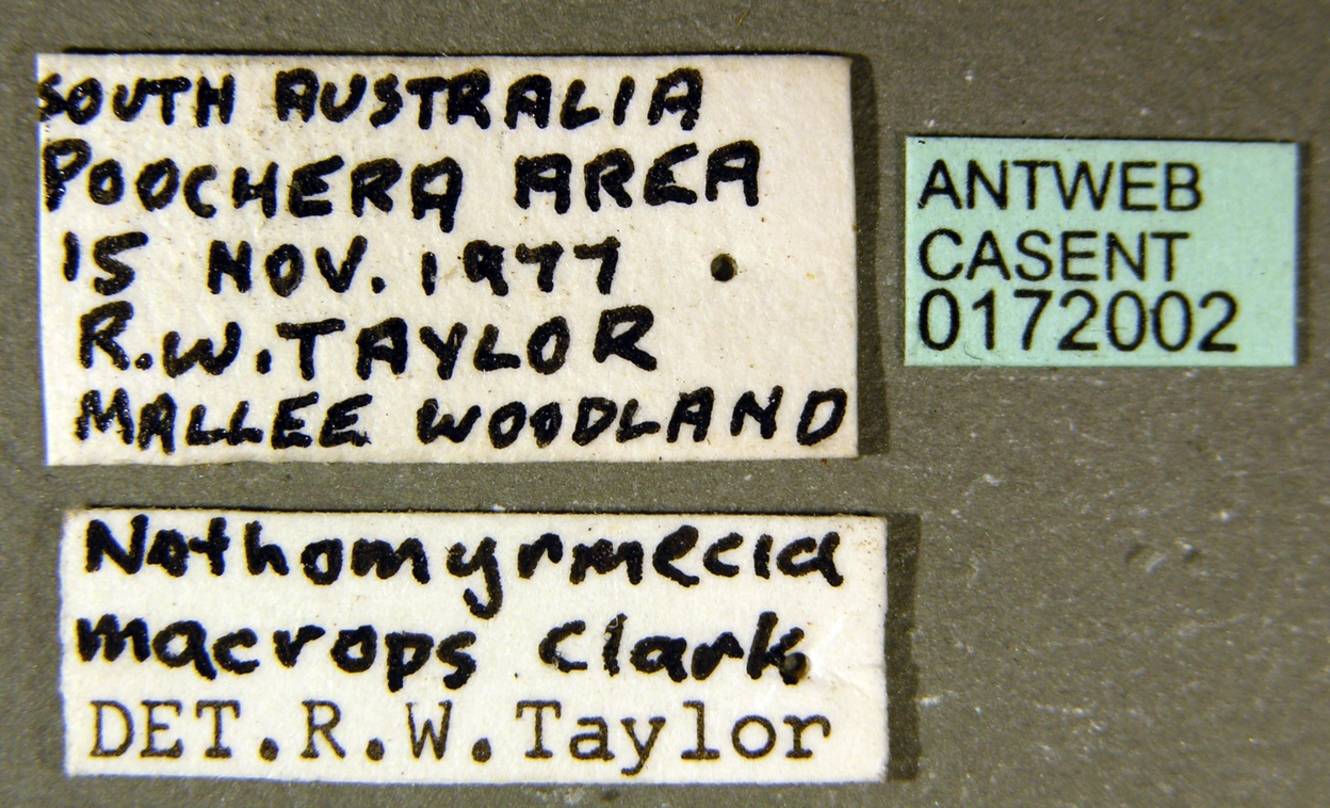

The first collection of ''Nothomyrmecia'' was made in December 1931 by amateur entomologist, Amy Crocker, whose colleagues had collected a range of insect samples for her during a field excursion, including specimens of two worker ants, reportedly near the Russell Range, inland from Israelite Bay in Western Australia. Crocker then passed the ants to Australian entomologist John S. Clark. Recognised shortly afterwards as a new species, these specimens became the

The first collection of ''Nothomyrmecia'' was made in December 1931 by amateur entomologist, Amy Crocker, whose colleagues had collected a range of insect samples for her during a field excursion, including specimens of two worker ants, reportedly near the Russell Range, inland from Israelite Bay in Western Australia. Crocker then passed the ants to Australian entomologist John S. Clark. Recognised shortly afterwards as a new species, these specimens became the syntype

In biological nomenclature, a syntype is any one of two or more biological types that is listed in a description of a taxon where no holotype was designated. Precise definitions of this and related terms for types have been established as part of ...

s. Entomologist Robert W. Taylor subsequently expressed doubt about the accuracy of recording of the original discovery site, stating the specimens were probably collected from the western end of the Great Australian Bight

The Great Australian Bight is a large oceanic bight, or open bay, off the central and western portions of the southern coastline of mainland Australia.

Extent

Two definitions of the extent are in use – one used by the International Hydrog ...

, south from Balladonia. The discovery of ''Nothomyrmecia'' and the appearance of its unique body structure led scientists in 1951 to initiate a series of searches to find the ant in Western Australia. Over three decades, teams of Australian and American collectors failed to re-find it; entomologists such as E. O. Wilson

Edward Osborne Wilson (June 10, 1929 – December 26, 2021) was an American biologist, naturalist, entomologist and writer. According to David Attenborough, Wilson was the world's leading expert in his specialty of myrmecology, the study of an ...

and William Brown, Jr., made attempts to search for it, but neither was successful. Then, on 22 October 1977, Taylor and his party of entomologists from Canberra serendipitously discovered a solitary worker ant at Poochera, South Australia

Poochera is a small grain belt town 60 km north-west of Streaky Bay on the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia.

The township of Poochera was not surveyed until 1920, and its name is thought to be taken from the name of King Poojeri, a local ...

, southeast of Ceduna Ceduna may refer to:

*Ceduna, South Australia, a town and locality

*Ceduna Airport

Ceduna Airport is a public airport in Ceduna, South Australia. The airport, which is owned by the District Council of Ceduna is located adjacent to the Eyre ...

, some from the reported site of the 1931 discovery. In 2012, a report discussing the possible presence of ''Nothomyrmecia'' in Western Australia did not confirm any sighting of the ant between Balladonia and the Western Australian coastal regions. After 46 years of searching for it, entomologists have dubbed the ant the 'Holy Grail

The Holy Grail (french: Saint Graal, br, Graal Santel, cy, Greal Sanctaidd, kw, Gral) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miracu ...

' of myrmecology

Myrmecology (; from Greek: μύρμηξ, ''myrmex'', "ant" and λόγος, ''logos'', "study") is a branch of entomology focusing on the scientific study of ants. Some early myrmecologists considered ant society as the ideal form of society and ...

.

Naming

In 1934 entomologist John S. Clark published a formaldescription

Description is the pattern of narrative development that aims to make vivid a place, object, character, or group. Description is one of four rhetorical modes (also known as ''modes of discourse''), along with exposition, argumentation, and narra ...

of ''Nothomyrmecia macrops'' as a new species and within a completely new genus and tribe (Nothomyrmecii) of the Ponerinae

Ponerinae is a subfamily of ants in the Poneromorph subfamilies group, with about 1,600 species in 47 extant genera, including '' Dinoponera gigantea'' - one of the world's largest species of ant. Mated workers have replaced the queen as the ...

. He did so because the two specimens (which then became the syntypes) bore no resemblance to any ant species he knew of, but they did share similar morphological characteristics with the extinct genus ''Prionomyrmex''. Clark notes that the head and mandibles of ''Nothomyrmecia'' and ''Prionomyrmex'' are somewhat similar, but the two can be distinguished by the appearance of the node (a segment between the mesosoma

The mesosoma is the middle part of the body, or tagma, of arthropods whose body is composed of three parts, the other two being the prosoma and the metasoma. It bears the legs, and, in the case of winged insects, the wings.

In hymenopterans of ...

and gaster). In 1951, Clark proposed the new ant subfamily Nothomyrmeciinae for his ''Nothomyrmecia'', based on morphological differences with other ponerine ants. This proposal was rejected by American entomologist William Brown Jr., who placed it in the subfamily Myrmeciinae

Myrmeciinae is a subfamily of the Formicidae, ants once found worldwide but now restricted to Australia and New Caledonia. This subfamily is one of several ant subfamilies which possess gamergates, female worker ants which are able to mate a ...

with ''Myrmecia'' and ''Prionomyrmex'', under the tribe Nothomyrmeciini. Its distant relationship with extant ants was confirmed after its rediscovery, and its placement within the Formicidae was accepted by most scientists until the late 1980s. The single waist node led scientists to believe that ''Nothomyrmecia'' should be separate from ''Myrmecia'' and retained Clark's original proposal. This proposal would place the ant into its own subfamily, despite many familiar morphological characteristics between the two genera. This separation from ''Myrmecia'' was retained until 2000.

In 2000, entomologist Cesare Baroni Urbani described a new Baltic fossil ''Prionomyrmex'' species (''P. janzeni''). After examining specimens of ''Nothomyrmecia'', Baroni Urbani stated that his new species and ''N. macrops'' were so morphologically similar that they belonged to the same genus. He proposed that the name ''Prionomyrmex'' should replace the name ''Nothomyrmecia'' (which would then be just a synonym), and also that the subfamily Nothomyrmeciinae should be called Prionomyrmeciinae.

In 2003, Russian palaeoentomologists G. M. Dlussky and E. B. Perfilieva separated ''Nothomyrmecia'' from ''Prionomyrmex'' on the basis of the fusion of an abdominal segment. In the same year, American entomologists P. S. Ward and S. G. Brady reached the same conclusion as Dlussky and Perfilieva and provided strong support for the

In 2000, entomologist Cesare Baroni Urbani described a new Baltic fossil ''Prionomyrmex'' species (''P. janzeni''). After examining specimens of ''Nothomyrmecia'', Baroni Urbani stated that his new species and ''N. macrops'' were so morphologically similar that they belonged to the same genus. He proposed that the name ''Prionomyrmex'' should replace the name ''Nothomyrmecia'' (which would then be just a synonym), and also that the subfamily Nothomyrmeciinae should be called Prionomyrmeciinae.

In 2003, Russian palaeoentomologists G. M. Dlussky and E. B. Perfilieva separated ''Nothomyrmecia'' from ''Prionomyrmex'' on the basis of the fusion of an abdominal segment. In the same year, American entomologists P. S. Ward and S. G. Brady reached the same conclusion as Dlussky and Perfilieva and provided strong support for the monophyly

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gro ...

of ''Prionomyrmex''. Ward and Brady also transferred both taxa as distinct genera in the older subfamily Myrmeciinae under the tribe Prionomyrmecini. In 2005 and 2008, Baroni Urbani suggested further evidence in favour of his former interpretation as opposed to Ward and Brady's. This view is not supported in subsequent relevant papers, which continue to use the classification of Ward and Brady, rejecting that of Baroni Urbani.

The ant is commonly known as the dinosaur ant, dawn ant, or living fossil

A living fossil is an extant taxon that cosmetically resembles related species known only from the fossil record. To be considered a living fossil, the fossil species must be old relative to the time of origin of the extant clade. Living foss ...

ant because of its plesiomorphic body structure. The generic name ''Nothomyrmecia'' means "false bulldog ant". Its specific epithet, ''macrops'' ("big eyes"), is derived from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

words ', meaning "long", or "large", and ', meaning "eyes".

Genetics and phylogeny

Studies show that all hymenopteran insects that have a diploid (2n) chromosome count above 52 are themselves all ants; ''Nothomyrmecia'' and another Ponerinae ant, '' Platythyrea tricuspidata'', share the highest number of chromosomes within all the Hymenoptera, having a diploid chromosome number of 92–94. Genetic evidence suggests that the age of themost recent common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

for ''Nothomyrmecia'' and ''Myrmecia'' is approximately 74 million years old, giving a likely origin in the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

. There are two hypotheses of the internal phylogeny of ''Nothomyrmecia'': subfamily Formicinae

The Formicinae are a subfamily within the Formicidae containing ants of moderate evolutionary development.

Formicines retain some primitive features, such as the presence of cocoons around pupae, the presence of ocelli in workers, and little ...

is more closely related to ''Nothomyrmecia'' than it is to ''Myrmecia'', evolving from ''Nothomyrmecia''-like ancestors. Alternatively, ''Nothomyrmecia'' and Aneuretinae

Aneuretinae is a subfamily of ants consisting of a single extant species, ''Aneuretus simoni'' ( Sri Lankan relict ant), and 9 fossil species. Earlier, the phylogenetic position of ''A. simoni'' was thought to be intermediate between primitive ...

may have shared a common ancestor; the two most likely separated from each other, and the first formicines evolved from the Aneuretinae instead. Currently, scientists agree that ''Nothomyrmecia'' most likely evolved from ancestors to the Ponerinae. ''Nothomyrmecia'' and other primitive ant genera such as '' Amblyopone'' and ''Myrmecia'' exhibit behaviour similar to a clade of soil-dwelling families of vespoid wasps. The following cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

generated by Canadian entomologist S. B. Archibald and his colleagues shows the possible phylogenetic position of ''Nothomyrmecia'' among some ants of the subfamily Myrmeciinae. They suggest that ''Nothomyrmecia'' may be closely related to extinct Myrmeciinae ants such as '' Avitomyrmex'', ''Macabeemyrma

''Macabeemyrma'' is an extinct genus of bulldog ants in the subfamily Myrmeciinae containing the single species ''Macabeemyrma ovata'', described in 2006 from Ypresian stage (Early Eocene) deposits of British Columbia, Canada. Only a single spe ...

'', '' Prionomyrmex'', and ''Ypresiomyrma

''Ypresiomyrma'' is an extinct genus of ants in the subfamily Myrmeciinae that was described in 2006. There are four species described; one species is from the Isle of Fur in Denmark, two are from the McAbee Fossil Beds in British Columbia, Cana ...

''.

Distribution and habitat

''Nothomyrmecia'' is present in the cool regions of

''Nothomyrmecia'' is present in the cool regions of South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

within mallee woodland and especially old-growth

An old-growth forestalso termed primary forest, virgin forest, late seral forest, primeval forest, or first-growth forestis a forest that has attained great age without significant disturbance, and thereby exhibits unique ecological feature ...

areas populated with various ''Eucalyptus

''Eucalyptus'' () is a genus of over seven hundred species of flowering trees, shrubs or mallees in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae. Along with several other genera in the tribe Eucalypteae, including '' Corymbia'', they are commonly known as e ...

'' species, including '' Eucalyptus brachycalyx'', '' E. gracilis'' and '' E. oleosa''. It is possible that it also occurs in Western Australia, from where it was first collected. The full distribution of ''Nothomyrmecia'' has never been assessed, and it is unknown how widespread it really is. If it does favour old-growth mallee woodland, it could have the potential for a wider range than is currently known from surveys and museum specimens. In 1998, ''Nothomyrmecia'' colonies were located in 18 areas along the Eyre Peninsula

The Eyre Peninsula is a triangular peninsula in South Australia. It is bounded by the Spencer Gulf on the east, the Great Australian Bight on the west, and the Gawler Ranges to the north.

Originally called Eyre’s Peninsula, it was named af ...

by a team of entomologists, a stretch of .

Nests are found in degraded limestone soil with '' Callitris'' trees present. Colony construction only occurs when the soil is moist. Nest entrance holes are difficult to detect as they are only in width, and are located under shallow leaf litter with no mounds or soil deposits present; guards are regularly seen. A single gallery, in diameter, forms inside a ''Nothomyrmecia'' colony. This gallery descends steeply into the ground towards a somewhat elliptical

Elliptical may mean:

* having the shape of an ellipse, or more broadly, any oval shape

** in botany, having an elliptic leaf shape

** of aircraft wings, having an elliptical planform

* characterised by ellipsis (the omission of words), or by conc ...

and horizontal chamber that is in diameter and in height. This chamber is typically below the soil's surface.

Behaviour and ecology

Foraging, diet and predators

Workers are nectarivores and can be found foraging on top of ''Eucalyptus'' trees, where they search for food and prey for the larvae. Workers are known to consume

Workers are nectarivores and can be found foraging on top of ''Eucalyptus'' trees, where they search for food and prey for the larvae. Workers are known to consume hemolymph

Hemolymph, or haemolymph, is a fluid, analogous to the blood in vertebrates, that circulates in the interior of the arthropod (invertebrate) body, remaining in direct contact with the animal's tissues. It is composed of a fluid plasma in which ...

from the insects they capture, and a queen in a captive colony was observed consuming a fly. Captured prey items are given to larvae, which are carnivorous. The workers search for prey in piles of leaves, killing small arthropods including ''Drosophila

''Drosophila'' () is a genus of flies, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or (less frequently) pomace flies, vinegar flies, or wine flies, a reference to the characteristic of many speci ...

'' flies, microlepidoptera

Microlepidoptera (micromoths) is an artificial (i.e., unranked and not monophyletic) grouping of moth families, commonly known as the 'smaller moths' (micro, Lepidoptera). These generally have wingspans of under 20 mm, and are thus harder to ...

ns and spiderlings. Prey items are usually less than in size, and workers grab them using their mandibles and forelegs, then kill them with their sting. Workers also feed on sweet substances such as honeydew secreted by scale insects and other Hemiptera; one worker alone may feed on these sources for 30 minutes. Pupae may be given to the larvae if a colony has a shortage of food. Workers are able to lay unfertilised eggs specifically to feed the larvae; these are known as trophic egg A trophic egg, in most species that produce them, usually is an unfertilised egg because its function is not reproduction but nutrition; in essence it serves as food for offspring hatched from viable eggs. The production of trophic eggs has been ob ...

s. Sometimes the adults, including the queen and other sexually active ants, consume these eggs. Workers transfer food via Trophallaxis

Trophallaxis () is the transfer of food or other fluids among members of a community through mouth-to-mouth ( stomodeal) or anus-to-mouth ( proctodeal) feeding. Along with nutrients, trophallaxis can involve the transfer of molecules such as pher ...

to other nestmates, including winged adults and larvae; the anal droplets are exuded by the larvae, which are taken up by the workers.

Age caste polyethism does not occur in ''Nothomyrmecia'', where the younger workers act as nurses and tend to the brood and the older workers go out and forage. The only ant known other than ''Nothomyrmecia'' which does not exhibit age caste polyethism is ''Stigmatomma pallipes''. Workers are strictly nocturnal, and only emerge from their nests on cold nights. They are most active at temperatures of , and are much more difficult to locate on warmer nights. Workers are possibly most active when it is cold because at these times they encounter fewer and less aggressive competitors, including other more dominant diurnal ant species that are sometimes found foraging during warm nights. Cold temperatures may also hamper the escape of prey items, so increasing the ants' hunting success. Unless a forager has captured prey, workers stay on trees for the remainder of the night until dawn, possibly relying on sunlight to navigate back to their nest. There is no evidence that they use chemical trails when foraging; instead, workers rely on visual cues to navigate around. Chemical markers may play an important role in recognising nest entrances. The ants are solitary foragers. Waste material, such as dead nestmates, cocoon shells, and food remnants, are disposed of far away from the nest.

Workers from different ''Nothomyrmecia'' colonies are not antagonistic towards one another, so they can forage together on a single tree, and they attack if an outsider tries to enter an underground colony. Ants such as '' Camponotus'' and ''Iridomyrmex

''Iridomyrmex'' is a genus of ants called rainbow ants (referring to their blue-green iridescent sheen) first described by Austrian entomologist Gustav Mayr in 1862. He placed the genus in the subfamily Dolichoderinae of the family Formici ...

'' may pose a threat to foragers or to a colony if they try to enter; foraging workers that encounter ''Iridomyrmex'' ants are vigorously attacked and killed. ''Nothomyrmecia'' workers counter this by secreting alarm pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

s from the mandibular gland and Dufour's gland. Foraging workers also engage in alternative methods to protect themselves from predators. Adopting a posture by opening the jaws in a threatening stance or deliberately falling onto the ground and remaining motionless until the threat subsides are two known methods. With that said, ''Nothomyrmecia'' is a timid and shy species that retreats if exposed.

Life cycle and reproduction

Nuptial flight

Nuptial flight is an important phase in the reproduction of most ant, termite, and some bee species. It is also observed in some fly species, such as '' Rhamphomyia longicauda''.

During the flight, virgin queens mate with males and then land t ...

(meaning that virgin queens and males emerge to mate) does not occur in ''Nothomyrmecia''. Instead, they engage in long-range dispersal (they walk away from the colony for some distance and mate) which presumably begins by late summer or autumn, with the winged adults emerging around March and April, but sometimes a colony may overwinter

Overwintering is the process by which some organisms pass through or wait out the winter season, or pass through that period of the year when "winter" conditions (cold or sub-zero temperatures, ice, snow, limited food supplies) make normal acti ...

(a process by which an organism waits out the winter season). These winged adults, born around January, are usually quite young when they begin to mate. Queens are seen around vegetation trying to flutter their vestigial wings – a behaviour seen in some brachypterous ''Myrmecia'' queens. Due to the queen's brachypterous wings, it is likely that the winged adults mate near their parent nest and release sex pheromones, or instead climb on vegetation far away from their nests and attract fully winged males. ''Nothomyrmecia'' is a polyandrous

Polyandry (; ) is a form of polygamy in which a woman takes two or more husbands at the same time. Polyandry is contrasted with polygyny, involving one male and two or more females. If a marriage involves a plural number of "husbands and wive ...

ant, in which queens mate with one or more males. In one study of 32 colonies, it was found that queens mated with an average of 1.37 males. After mating, new colonies can be founded by one or more queens; a colony with two queens reduces to a single queen when the nest is mature, forming colonies that are termed Gyne, monogynous. The queens will compete for dominance, and the subordinate queen is later expelled by workers who drag her outside the nest. An existing nest with no queen may adopt a foraging queen looking for an area to begin her colony, as well as workers. Queens are semi-claustral, meaning that during the initial establishment of the new colony the queen will forage among the worker ants so that she can ensure sufficient food to raise her brood. Sometimes a queen will leave her nest at night with the sole purpose of finding food or water for herself.

Eggs are not seen in nests from April to September. They are laid by late December and develop into adults by mid-February; pupation does not occur until March. ''Nothomyrmecia'' is univoltine, meaning that the queen produces a single generation of eggs per season, and it sometimes may take as many as 12 months for an egg to develop into an adult. Adults are defined as either juveniles or post-juveniles: juveniles are too young (perhaps several months old) to have experienced overwintering whereas post-juveniles have. The pupae generally overwinter and begin to hatch by the time a new generation of eggs is laid. Workers are capable of laying reproductive eggs; it is not known if these develop into males, females or both. This uncertainty results from the suggestion that, because some colonies have been shown to have high levels of genetic diversity, worker ants could be inseminated by males and act as supplementary reproductives. Eggs are scattered among the nest, whereas the larvae and pupae are set apart from each other in groups. The larvae are capable of crawling around the nest. When the larvae are ready to spin their cocoons, they swell up and are later buried by workers in the ground to allow cocoon formation. Small non-aggressive workers that act as nurses provide assistance for newborns to hatch from their cocoons. At maturity, a nest may only contain 50 to 100 adults. In some nests, colony founding can occur within a colony itself: when a queen dies, the colony may be taken over by one of her daughters, or it may adopt a newly mated queen, restricting reproduction among workers; this method of founding extends the lifespan of the colony almost indefinitely.

Relationship with humans

Conservation

Significance

''Nothomyrmecia macrops'' is widely regarded as the most plesiomorphic living ant and, as such, has aroused considerable interest among the entomological community. Following its rediscovery it was the subject of a prolonged and rigorous series of studies involving Australian, American and European ant specialists and it soon became one of the most studied ant species on the planet. ''Nothomyrmecia'' can be cultured with ease, and could potentially prove a useful subject for research into learning in insects as well as the physiology of nocturnal vision. Since its chance discovery at Poochera, the town has become of international interest to myrmecologists, and it is possibly the only town in the world with ant-based tourism. Promoting it as a tourist attraction, ''Nothomyrmecia'' has been adopted as the emblem of the Poochera community. Pictures of the ant have been stencilled onto the pavements, and a large sculpture of ''Nothomyrmecia'' has been erected in the town.Notes

References

Cited literature

*External links

* *''Nothomyrmecia'' at Arkive.org

{{Taxonbar, from=Q1207403 Myrmeciinae Critically endangered insects Hymenoptera of Australia Endemic fauna of Australia Endangered fauna of Australia Monotypic ant genera Mallee Woodlands and Shrublands