North-West Passage on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the

In the 21st century, major changes to the ice pack due to

In the 21st century, major changes to the ice pack due to  The first commercial

The first commercial

The Northwest Passage has three sections:

* East

** East of Baffin Island:

The Northwest Passage has three sections:

* East

** East of Baffin Island:

As a result of their westward explorations and their settlement of Greenland, the

As a result of their westward explorations and their settlement of Greenland, the

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

oceans through the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

, along the northern coast of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Siberia is accordingly called the Northeast Passage

The Northeast Passage (abbreviated as NEP) is the Arctic shipping routes, shipping route between the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, Pacific Oceans, along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia. The western route through the islands o ...

(NEP).

The various islands of the archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Arch ...

are separated from one another and from Mainland Canada by a series of Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

waterways collectively known as the Northwest Passages, Northwestern Passages or the Canadian Internal Waters.

For centuries, European explorers, beginning with Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

in 1492, sought a navigable passage as a possible trade route to Asia, but were blocked by North, Central, and South America, by ice, or by rough waters (e.g. Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

). An ice-bound northern route was discovered in 1850 by the Irish explorer Robert McClure. Scotsman John Rae explored a more southerly area in 1854 through which Norwegian Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen beg ...

found a route, making the first complete passage in 1903–1906. Until 2009, the Arctic pack ice prevented regular marine shipping

Maritime transport (or ocean transport) and hydraulic effluvial transport, or more generally waterborne transport, is the transport of people (passengers) or goods (cargo) via waterways. Freight transport by sea has been widely used thro ...

throughout most of the year. Arctic sea ice decline

Arctic sea ice decline has occurred in recent decades due to the effects of climate change on oceans, with declines in sea ice area, extent, and volume. Sea ice in the Arctic Ocean has been melting more in summer than it refreezes in the winter. ...

, linked primarily to climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

, has rendered the waterways more navigable for ice navigation.

The contested sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

claims over the waters may complicate future shipping through the region: the Canadian government

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown-in ...

maintains that the Northwestern Passages are part of Canadian Internal Waters Canadian Internal Waters is a Canadian term for the waters "on the landward side of the baselines of the territorial sea of Canada."

Definition

The baselines are defined as "the low-water line along the coast or on a low-tide elevation that is situ ...

, but the United States and various Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an countries claim that they are an international strait and transit passage, allowing free and unencumbered passage. If, as has been claimed, parts of the eastern end of the Passage are barely deep, the route's viability as a Euro-Asian shipping route is reduced. In 2016, a Chinese shipping line expressed a desire to make regular voyages of cargo ships using the passage to the Eastern United States

The Eastern United States, commonly referred to as the American East, Eastern America, or simply the East, is the region of the United States to the east of the Mississippi River. In some cases the term may refer to a smaller area or the East C ...

and Europe, after a successful passage by ''Nordic Orion

MS ''Nordic Orion'' is a Danish bulk carrier registered in Panama City. A coal and ore carrier, ''Nordic Orion'' has a capacity of . It was built in 2011 by Oshima Shipbuilding. ''Nordic Orion'' has an ice-strengthened hull, and it is notable ...

'' of 73,500 tonnes deadweight tonnage

Deadweight tonnage (also known as deadweight; abbreviated to DWT, D.W.T., d.w.t., or dwt) or tons deadweight (DWT) is a measure of how much weight a ship can carry. It is the sum of the weights of cargo, fuel, fresh water, ballast water, pro ...

in September 2013. Fully loaded, ''Nordic Orion'' sat too deep in the water to sail through the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

.

Overview

Early expeditions

Before theLittle Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

(late Middle Ages to the 19th century), Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

sailed as far north and west as Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island ( iu, script=Latn, Umingmak Nuna, lit=land of muskoxen; french: île d'Ellesmere) is Canada's northernmost and third largest island, and the tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Br ...

, Skraeling Island

Skraeling Island lies off the east coast of Ellesmere Island in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, at the mouth of Alexandra Fiord. Buchanan Bay lies to its north-east.

History

The Norse referred to the indigenous peoples they encountered in ...

and Ruin Island

Ruin Island is a small island off the coast of the Inglefield Land region of northwest Greenland. In the 1930s, Danish archaeologist Erik Holtved discovered the remains of human habitation on the island. The culture associated with this archae ...

for hunting expeditions and trading with the Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

and people of the Dorset culture

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from to between and , that followed the Pre-Dorset and preceded the Thule people (proto-Inuit) in the North American Arctic. The culture and people are named after Cape Dorset (now Kinngait) in ...

who already inhabited the region. Between the end of the 15th century and the 20th century, colonial powers

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

from Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

dispatched explorers in an attempt to discover a commercial sea route north and west around North America. The Northwest Passage represented a new route to the established trading nations of Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

.

England called the hypothetical northern route the "Northwest Passage". The desire to establish such a route motivated much of the European exploration of both coasts of North America, also known as the New World. When it became apparent that there was no route through the heart of the continent, attention turned to the possibility of a passage through northern waters. There was a lack of scientific knowledge about conditions; for instance, some people believed that seawater

Seawater, or salt water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has appro ...

was incapable of freezing. (As late as the mid-18th century, Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

had reported that Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and othe ...

iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open (salt) water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially-derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". The ...

s had yielded fresh water, seemingly confirming the hypothesis.) Explorers thought that an open water route close to the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

must exist. The belief that a route lay to the far north persisted for several centuries and led to numerous expeditions into the Arctic. Many ended in disaster, including that by Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through t ...

in 1845. While searching for him the McClure Arctic Expedition discovered the Northwest Passage in 1850.

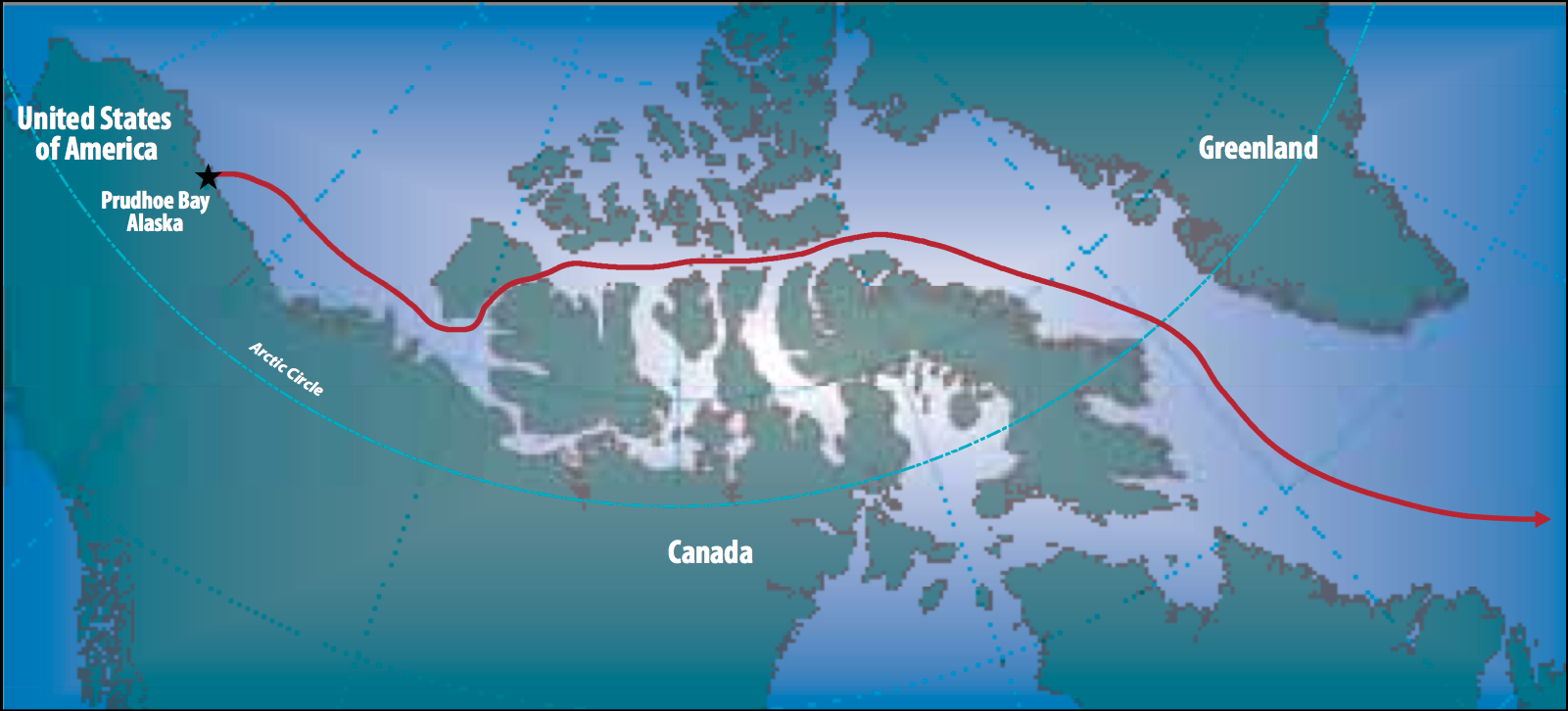

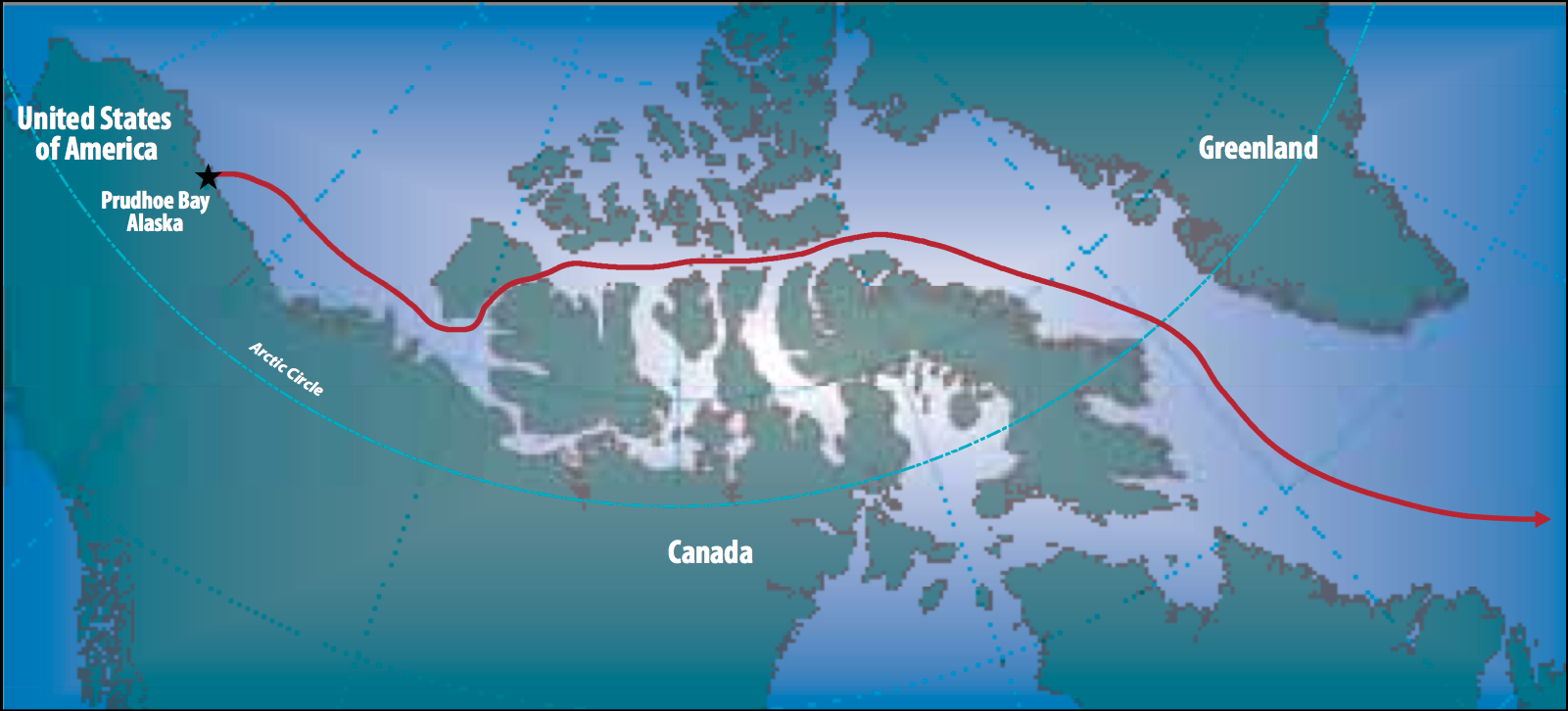

In 1906, the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen beg ...

was the first to complete the passage solely by ship, from Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

to Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

in the sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

. Since that date, several fortified ships have made the journey.

From east to west, the direction of most early exploration attempts, expeditions entered the passage from the Atlantic Ocean via the Davis Strait

Davis Strait is a northern arm of the Atlantic Ocean that lies north of the Labrador Sea. It lies between mid-western Greenland and Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada. To the north is Baffin Bay. The strait was named for the English explorer John ...

and through Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; kl, Avannaata Imaa; french: Baie de Baffin), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arc ...

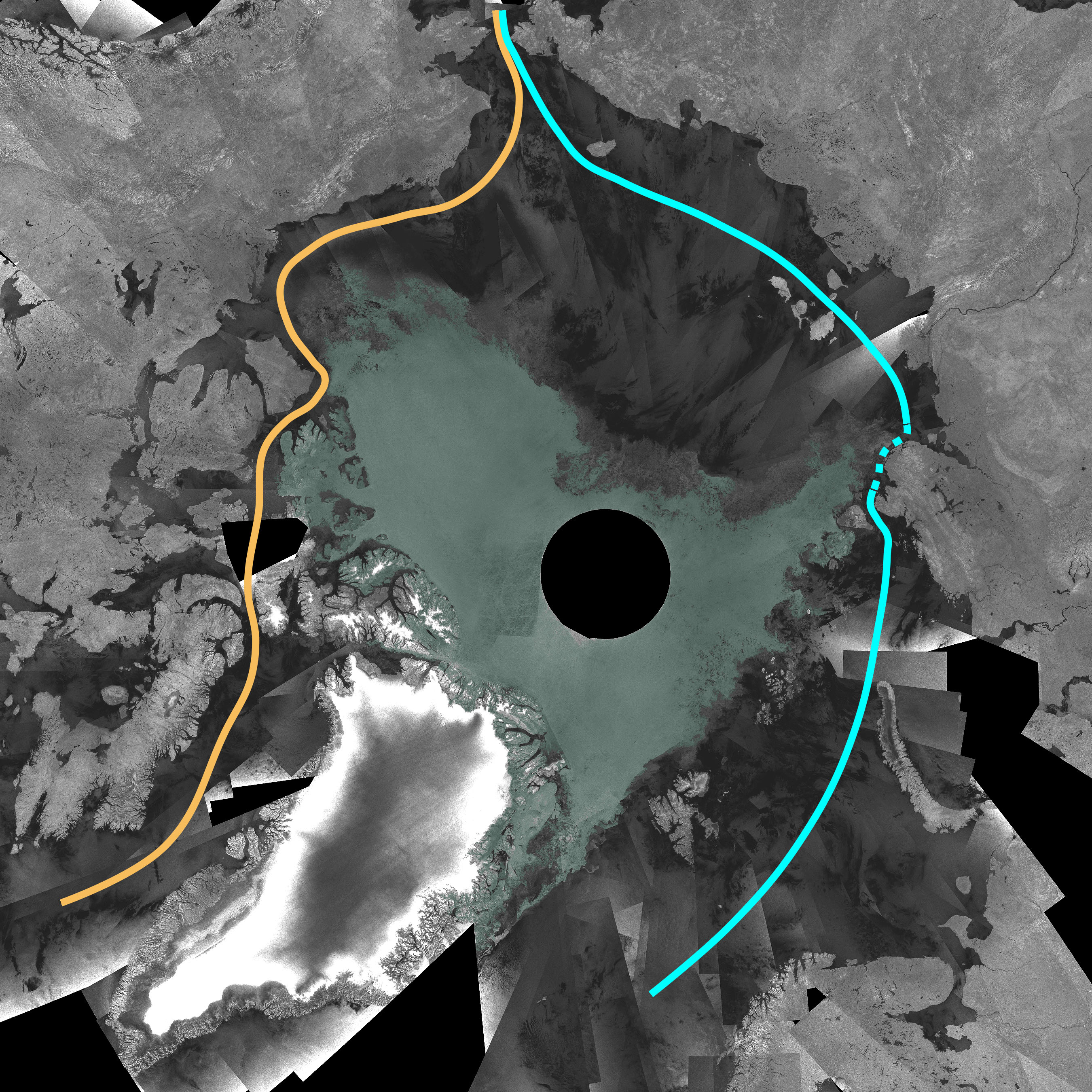

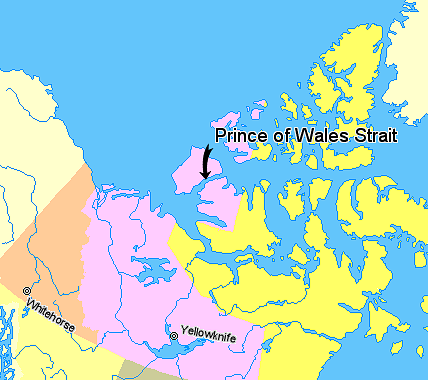

, both of which are in Canada. Five to seven routes have been taken through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, via the McClure Strait

The M'Clure Strait (sometimes rendered McClure Strait) is a strait on the edge of the Canadian Northwest Territories. It forms the northwestern end of the Parry Channel which extends east all the way to Baffin Bay and is thus a possible route for ...

, Dease Strait, and the Prince of Wales Strait, but not all of them are suitable for larger ships. From there ships passed through westward through the Beaufort Sea

The Beaufort Sea (; french: Mer de Beaufort, Iñupiaq: ''Taġiuq'') is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located north of the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, and Alaska, and west of Canada's Arctic islands. The sea is named after Sir ...

and the Chukchi Sea

Chukchi Sea ( rus, Чуко́тское мо́ре, r=Chukotskoye more, p=tɕʊˈkotskəjə ˈmorʲɪ), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west ...

, and then southwards through the Bering Strait (separating Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

and Alaska), into the Pacific Ocean.

Potential as a shipping lane

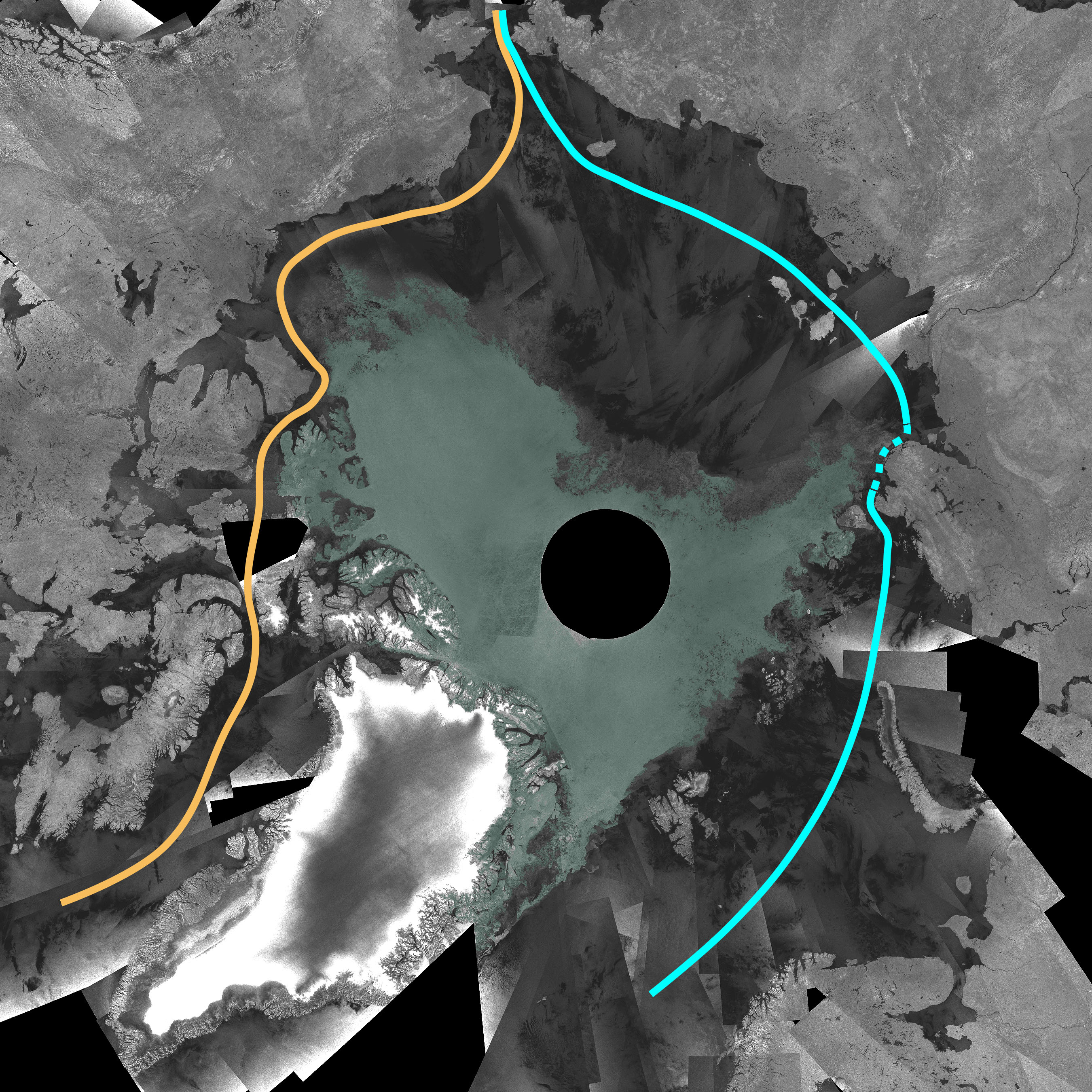

In the 21st century, major changes to the ice pack due to

In the 21st century, major changes to the ice pack due to climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

have stirred speculation that the passage may become clear enough of ice to permit safe commercial shipping for at least part of the year. On August 21, 2007, the Northwest Passage became open to ships without the need of an icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

. According to Nalan Koc of the Norwegian Polar Institute

The Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI; no, Norsk Polarinstitutt) is Norway's central governmental institution for scientific research, mapping and environmental monitoring in the Arctic and the Antarctic. The NPI is a directorate under Norway's Min ...

, this was the first time the Passage has been clear since they began keeping records in 1972. The Northwest Passage opened again on August 25, 2008. It is usually reported in mainstream media that ocean thawing will open up the Northwest Passage (and the Northern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) (russian: Се́верный морско́й путь, ''Severnyy morskoy put'', shortened to Севморпуть, ''Sevmorput'') is a shipping route officially defined by Russian legislation as lying east of N ...

) for various kind of ships, making it possible to sail around the Arctic ice cap

The Arctic ice pack is the sea ice cover of the Arctic Ocean and its vicinity. The Arctic ice pack undergoes a regular seasonal cycle in which ice melts in spring and summer, reaches a minimum around mid-September, then increases during fall ...

and possibly cutting thousands of miles off shipping routes. Warning that the NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

satellite images suggested that the Arctic had entered a "death spiral" caused by climate change, Professor Mark Serreze, a sea ice specialist at the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center

The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) is a United States information and referral center in support of polar and cryospheric research. NSIDC archives and distributes digital and analog snow and ice data and also maintains information abo ...

(NSIDC) said: "The passages are open. It's a historic event. We are going to see this more and more as the years go by."

However, some thick sections of ice will remain hard to melt in the shorter term. Drifting and persistence of large chunks of ice, especially in springtime, can be problematic as they can clog entire straits or severely damage a ship's hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

. Cargo routes may thus be slow and uncertain, depending on prevailing conditions and the ability to predict them. Because much containerized traffic operates in a just-in-time mode (which does not tolerate delays well) and because of the relative isolation of the passage (which impedes shipping companies from optimizing their operations by grouping multiple stopovers on the same itinerary), the Northwest Passage and other Arctic routes are not always seen as promising shipping lanes by industry insiders, at least for the time being. The uncertainty related to physical damage to ships is also thought to translate into higher insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

premiums, especially because of the technical challenges posed by Arctic navigation (as of 2014, only 12 percent of Canada's Arctic waters have been charted to modern standards).

The Beluga group of Bremen

Bremen ( Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state cons ...

, Germany, sent the first Western commercial vessels through the Northern Sea Route (Northeast Passage) in 2009. Canada's Prime Minister Stephen Harper

Stephen Joseph Harper (born April 30, 1959) is a Canadian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Canada from 2006 to 2015. Harper is the first and only prime minister to come from the modern-day Conservative Party of Canada, ...

announced that "ships entering the North-West passage should first report to his government".

The first commercial

The first commercial cargo ship

A cargo ship or freighter is a merchant ship that carries cargo, goods, and materials from one port to another. Thousands of cargo carriers ply the world's seas and oceans each year, handling the bulk of international trade. Cargo ships are usu ...

to have sailed through the Northwest Passage was in August 1969. SS ''Manhattan'', of 115,000 deadweight tonnage

Deadweight tonnage (also known as deadweight; abbreviated to DWT, D.W.T., d.w.t., or dwt) or tons deadweight (DWT) is a measure of how much weight a ship can carry. It is the sum of the weights of cargo, fuel, fresh water, ballast water, pro ...

, was the largest commercial vessel ever to navigate the Northwest Passage.

The largest passenger ship to navigate the Northwest Passage was the cruise liner

Cruise ships are large passenger ships used mainly for vacationing. Unlike ocean liners, which are used for transport, cruise ships typically embark on round-trip voyages to various ports-of-call, where passengers may go on tours known as "sho ...

of gross tonnage

Gross tonnage (GT, G.T. or gt) is a nonlinear measure of a ship's overall internal volume. Gross tonnage is different from gross register tonnage. Neither gross tonnage nor gross register tonnage should be confused with measures of mass or weig ...

69,000. Starting on August 10, 2016, the ship sailed from Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. ...

to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

with 1,500 passengers and crew, taking 28 days.

In 2018, two of the freighters leaving Baffinland's port in the Milne Inlet

Milne Inlet () is a small, shallow arm of Eclipse Sound which, along with Navy Board Inlet, separates Bylot Island from Baffin Island in Nunavut's Qikiqtaaluk Region. Milne Inlet flows in a southerly direction from Navy Board Inlet at the c ...

, on Baffin Island

Baffin Island (formerly Baffin Land), in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is , slightly larger than Spain; its population was 13,039 as of the 2021 Canadia ...

's north shore, were bound for ports in Asia. Those freighters did not sail west through the remainder of the Northwest Passage, they sailed east, rounded the tip of Greenland, and transitted Russia's Northern Sea Route.

Routes

The Northwest Passage has three sections:

* East

** East of Baffin Island:

The Northwest Passage has three sections:

* East

** East of Baffin Island: Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; kl, Avannaata Imaa; french: Baie de Baffin), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arc ...

between Greenland and Baffin Island

Baffin Island (formerly Baffin Land), in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is , slightly larger than Spain; its population was 13,039 as of the 2021 Canadia ...

to Lancaster Sound

Lancaster Sound () is a body of water in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is located between Devon Island and Baffin Island, forming the eastern entrance to the Parry Channel and the Northwest Passage. East of the sound lies Baffin Bay ...

at the north end of Baffin Island, or

** West of Baffin Island (impractical): Through Hudson Strait

Hudson Strait (french: Détroit d'Hudson) links the Atlantic Ocean and Labrador Sea to Hudson Bay in Canada. This strait lies between Baffin Island and Nunavik, with its eastern entrance marked by Cape Chidley in Newfoundland and Labrador and ...

south of Baffin Island, north through the Foxe Basin

Foxe Basin is a shallow oceanic basin north of Hudson Bay, in Nunavut, Canada, located between Baffin Island and the Melville Peninsula. For most of the year, it is blocked by sea ice (fast ice) and drift ice made up of multiple ice floes.

...

, west through the Fury and Hecla Strait

Fury and Hecla Strait is a narrow (from wide) Arctic seawater channel located in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada.

Geography

Situated between Baffin Island to the north and the Melville Peninsula to the south, it connects Foxe Basin o ...

, north to Lancaster Sound through the Gulf of Boothia

The Gulf of Boothia is a body of water in Nunavut, Canada. Administratively it is divided between the Kitikmeot Region on the west and the Qikiqtaaluk Region on the east. It merges north into Prince Regent Inlet, the two forming a single bay w ...

and Prince Regent Inlet

Prince Regent Inlet () is a body of water in Nunavut, Canada between the west end of Baffin Island (Brodeur Peninsula) and Somerset Island on the west. It opens north into Lancaster Sound and to the south merges into the Gulf of Boothia. The Arc ...

. The Fury and Hecla Strait is usually closed by ice.

* Centre: Canadian Arctic Archipelago

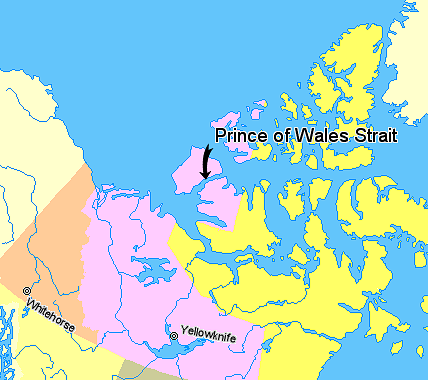

** North: From Lancaster Sound west through the Parry Channel

The Parry Channel ( iu, ᑕᓪᓗᕈᑎᐅᑉ ᐃᒪᖓ, ''Tallurutiup Imanga'') is a natural waterway through the central Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Its eastern two-thirds lie in the territory of Nunavut, while its western third (west of 110� ...

to the Prince of Wales Strait on the northwest side of Victoria Island

Victoria Island ( ikt, Kitlineq, italic=yes) is a large island in the Arctic Archipelago that straddles the boundary between Nunavut and the Northwest Territories of Canada. It is the eighth-largest island in the world, and at in area, it is ...

. M'Clure Strait to the northwest is ice-filled; southwest through the Prince of Wales Strait between Victoria Island and Banks Island might be passable, or

** South: From Lancaster Sound west past Prince Regent Inlet

Prince Regent Inlet () is a body of water in Nunavut, Canada between the west end of Baffin Island (Brodeur Peninsula) and Somerset Island on the west. It opens north into Lancaster Sound and to the south merges into the Gulf of Boothia. The Arc ...

(basically a cul-de-sac but it may be possible to exit west through the Bellot Strait

Bellot Strait is a strait in Nunavut that separates Somerset Island to its north from the Murchison Promontory of Boothia Peninsula to its south, which is the northernmost part of the mainland of the Americas. The and strait connects the Gulf ...

), past Somerset Island, south through Peel Sound between Somerset Island and Prince of Wales Island, either southwest through Victoria Strait (ice-choked), or directly south along the coast through Rae Strait

Rae Strait is a small strait in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located between King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula on the mainland to the east. It is named after Scottish Arctic explorer John Rae who, in 1854, was the fir ...

and James Ross Strait

James Ross Strait, an arm of the Arctic Ocean, is a channel between King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula in the Canadian territory of Nunavut.

long, and to wide, it connects M'Clintock Channel to the Rae Strait to the south. Islands ...

and west through Simpson Strait

The Simpson Strait () is a natural, shallow waterway separating King William Island to the north from Adelaide Peninsula on Nunavut's mainland to the south. The strait, an arm of the Arctic Ocean, connects the Queen Maud Gulf with Rasmussen Bas ...

south of King William Island

King William Island (french: Île du Roi-Guillaume; previously: King William Land; iu, Qikiqtaq, script=Latn) is an island in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, which is part of the Arctic Archipelago. In area it is between and making it the 6 ...

(shallow) into Queen Maud Gulf, then west along the mainland coast south of Victoria Island.

* West: There being no major islands, follow the coast to the Bering Strait.

Many attempts were made to find a salt water exit west from Hudson Bay, but the Fury and Hecla Strait in the far north is blocked by ice. The eastern entrance and main axis of the northwest passage, the Parry Channel, was found in 1819. The approach from the west through Bering Strait is impractical because of the need to sail around ice near Point Barrow

Point Barrow or Nuvuk is a headland on the Arctic coast in the U.S. state of Alaska, northeast of Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow). It is the northernmost point of all the territory of the United States, at , south of the North Pole. (The nor ...

. East of Point Barrow the coast is fairly clear in summer. This area was mapped in pieces from overland in 1821–1839. This leaves the large rectangle north of the coast, south of Parry Channel and east of Baffin Island. This area was mostly mapped in 1848–1854 by ships looking for Franklin's lost expedition. The first crossing was made by Amundsen in 1903–1906. He used a small ship and hugged the coast.

Extent

TheInternational Hydrographic Organization

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) is an intergovernmental organisation representing hydrography. , the IHO comprised 98 Member States.

A principal aim of the IHO is to ensure that the world's seas, oceans and navigable waters ...

defines the limits of the Northwestern Passages as follows:

Historical expeditions

As a result of their westward explorations and their settlement of Greenland, the

As a result of their westward explorations and their settlement of Greenland, the Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

s sailed as far north and west as Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island ( iu, script=Latn, Umingmak Nuna, lit=land of muskoxen; french: île d'Ellesmere) is Canada's northernmost and third largest island, and the tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Br ...

, Skraeling Island

Skraeling Island lies off the east coast of Ellesmere Island in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, at the mouth of Alexandra Fiord. Buchanan Bay lies to its north-east.

History

The Norse referred to the indigenous peoples they encountered in ...

for hunting expeditions and trading with Inuit groups. The subsequent arrival of the Little Ice Age is thought to have been one of the reasons that European seafaring into the Northwest Passage ceased until the late 15th century.

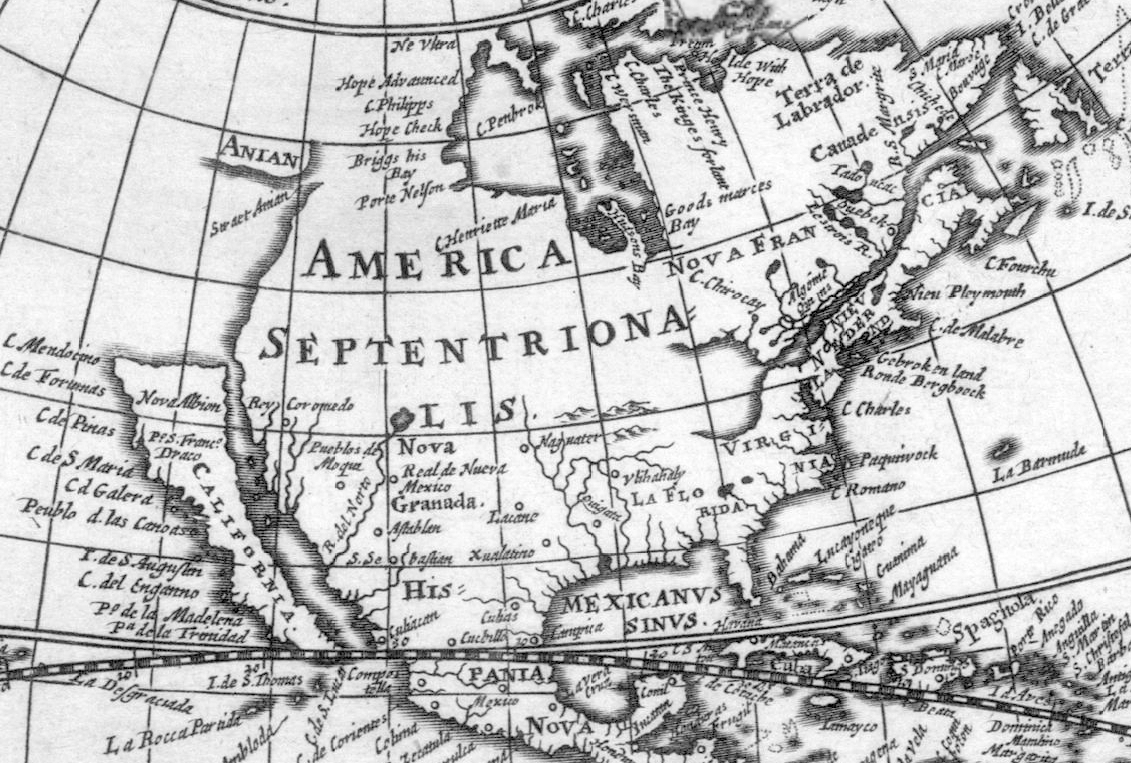

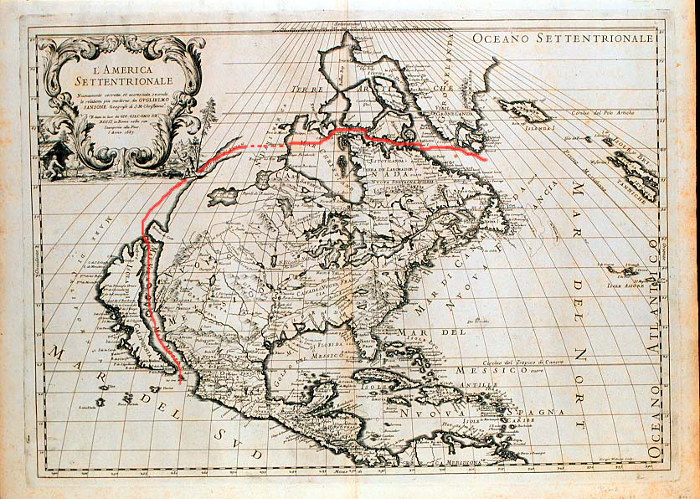

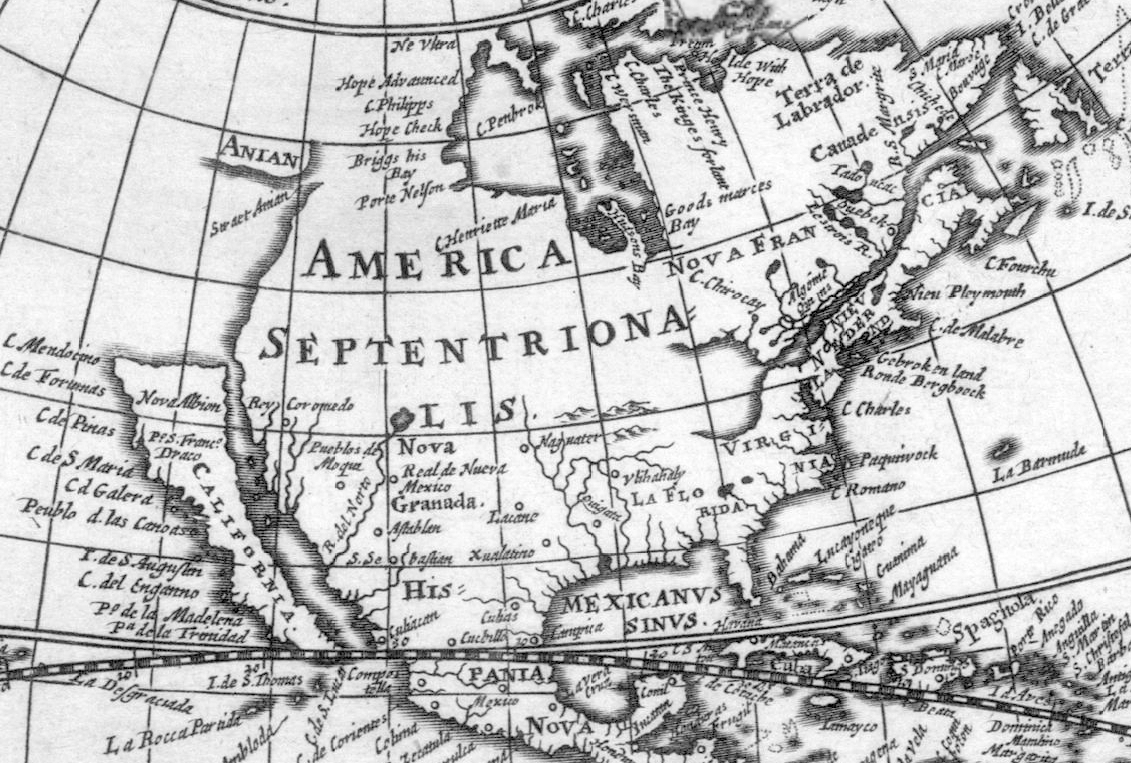

Strait of Anián

In 1539,Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

commissioned Francisco de Ulloa

Francisco de Ulloa () (died 1540) was a Spanish explorer who explored the west coast of present-day Mexico and the Baja California Peninsula under the commission of Hernán Cortés. Ulloa's voyage was among the first to disprove the cartograph ...

to sail along the Baja California Peninsula on the western coast of North America. Ulloa concluded that the Gulf of California

The Gulf of California ( es, Golfo de California), also known as the Sea of Cortés (''Mar de Cortés'') or Sea of Cortez, or less commonly as the Vermilion Sea (''Mar Bermejo''), is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean that separates the Baja C ...

was the southernmost section of a strait supposedly linking the Pacific with the Gulf of Saint Lawrence

, image = Baie de la Tour.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Gulf of St. Lawrence from Anticosti National Park, Quebec

, image_bathymetry = Golfe Saint-Laurent Depths fr.svg

, alt_bathymetry = Bathymetry ...

. His voyage perpetuated the notion of the Island of California and saw the beginning of a search for the Strait of Anián.

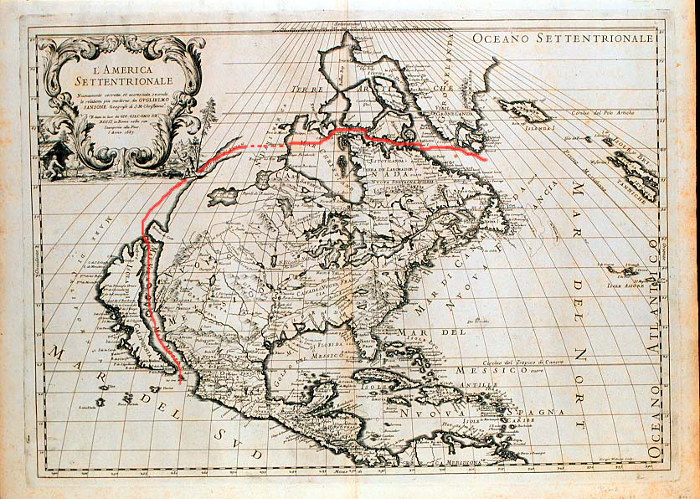

The strait probably took its name from Ania, a Chinese province mentioned in a 1559 edition of Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in '' The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

's book; it first appears on a map issued by Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

cartographer

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an ...

Giacomo Gastaldi about 1562. Five years later Bolognino Zaltieri issued a map showing a narrow and crooked Strait of Anian separating Asia from the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

. The strait grew in European imagination as an easy sea lane linking Europe with the residence of Khagan

Khagan or Qaghan (Mongolian:; or ''Khagan''; otk, 𐰴𐰍𐰣 ), or , tr, Kağan or ; ug, قاغان, Qaghan, Mongolian Script: ; or ; fa, خاقان ''Khāqān'', alternatively spelled Kağan, Kagan, Khaghan, Kaghan, Khakan, Khakhan ...

(the Great Khan) in Cathay

Cathay (; ) is a historical name for China that was used in Europe. During the early modern period, the term ''Cathay'' initially evolved as a term referring to what is now Northern China, completely separate and distinct from China, which ...

(northern China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

).

Cartographers and seamen tried to demonstrate its reality. Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 ...

sought the western entrance in 1579. The Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

pilot Juan de Fuca, sailing from Acapulco (in Mexico) under the flag of the Spanish crown, claimed he had sailed the strait from the Pacific to the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

and back in 1592. The Spaniard Bartholomew de Fonte

The Pacific Northwest coast of North America was one of the last coastlines reached by European explorers. In terms of sailing time from Europe, it was one of the most distant places on earth. This article covers what Europeans knew or thought ...

claimed to have sailed from Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

to the Pacific via the strait in 1640.

Northern Atlantic

The first recorded attempt to discover the Northwest Passage was the east–west voyage ofJohn Cabot

John Cabot ( it, Giovanni Caboto ; 1450 – 1500) was an Italian navigator and explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is the earliest-known European exploration of coastal Nor ...

in 1497, sent by Henry VII in search of a direct route to the Orient

The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of '' Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the ...

. In 1524, Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

sent Estêvão Gomes to find a northern Atlantic passage to the Spice Islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices are ...

. An English expedition was launched in 1576 by Martin Frobisher

Sir Martin Frobisher (; c. 1535 – 22 November 1594) was an English seaman and privateer who made three voyages to the New World looking for the North-west Passage. He probably sighted Resolution Island near Labrador in north-eastern Canad ...

, who took three trips west to what is now the Canadian Arctic

Northern Canada, colloquially the North or the Territories, is the vast northernmost region of Canada variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories and ...

in order to find the passage. Frobisher Bay

Frobisher Bay is an inlet of the Davis Strait in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the southeastern corner of Baffin Island. Its length is about and its width varies from about at its outlet into the Labrador Sea to ...

, which he first charted, is named after him.

As part of another expedition, in July 1583 Sir Humphrey Gilbert

Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539 – 9 September 1583) was an English adventurer, explorer, member of parliament and soldier who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and was a pioneer of the English colonial empire in North America ...

, who had written a treatise on the discovery of the passage and was a backer of Frobisher, claimed the territory of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

for the English crown. On August 8, 1585, the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

explorer John Davis entered Cumberland Sound

Cumberland Sound (french: Baie Cumberland; Inuit: ''Kangiqtualuk'') is an Arctic waterway in Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is a western arm of the Labrador Sea located between Baffin Island's Hall Peninsula and the Cumberland Peninsula ...

, Baffin Island.

The major rivers on the east coast were also explored in case they could lead to a transcontinental passage. Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier ( , also , , ; br, Jakez Karter; 31 December 14911 September 1557) was a French- Breton maritime explorer for France. Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of ...

's explorations of the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

in 1535 were initiated in hope of finding a way through the continent. Cartier became persuaded that the St. Lawrence was the Passage; when he found the way blocked by rapids at what is now Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, he was so certain that these rapids were all that was keeping him from China (in French, ''la Chine''), that he named the rapids for China. Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fr ...

renamed them Sault Saint-Louis in 1611, but the name was changed to Lachine Rapids

The Lachine Rapids (french: Rapides de Lachine) are a series of rapids on the Saint Lawrence River, between the Island of Montreal and the south shore. They are located near the former city of Lachine.

The Lachine Rapids contain large standing ...

in the mid-19th century.

In 1602, George Weymouth

George Weymouth (Waymouth) () was an English explorer of the area now occupied by the state of Maine.

Voyages

George Weymouth was a native of Cockington, Devon, who spent his youth studying shipbuilding and mathematics.

In 1602 Weymouth was ...

became the first European to explore what would later be called Hudson Strait

Hudson Strait (french: Détroit d'Hudson) links the Atlantic Ocean and Labrador Sea to Hudson Bay in Canada. This strait lies between Baffin Island and Nunavik, with its eastern entrance marked by Cape Chidley in Newfoundland and Labrador and ...

when he sailed into the Strait. Weymouth's expedition to find the Northwest Passage was funded jointly by the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sou ...

and the Muscovy Company

The Muscovy Company (also called the Russia Company or the Muscovy Trading Company russian: Московская компания, Moskovskaya kompaniya) was an English trading company chartered in 1555. It was the first major chartered joint s ...

. ''Discovery'' was the same ship used by Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 16 ...

on his final voyage.

John Knight, employed by the British East India Company and the Muscovy Company, set out in 1606 to follow up on Weymouth's discoveries and find the Northwest Passage. After his ship ran aground and was nearly crushed by ice, Knight disappeared while searching for a better anchorage.

In 1609, Henry Hudson sailed up what is now called the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

in search of the Passage; encouraged by the saltiness of the water in the estuary,