Musical note on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

\relative c'

\layout

\midi

The staff above shows the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C and then in reverse order, with no key signature or accidentals.

Music notation systems have used letters of the

Music notation systems have used letters of the

Converter: Frequencies to note name, ± cents

* ttp://www.sengpielaudio.com/calculator-notenames.htm Music notation systems − Frequencies of equal temperament tuning – The English and American system versus the German systembr>Frequencies of musical notesLearn How to Read Sheet MusicFree music paper for printing and downloading

{{Authority control Musical notation

music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

, notes are distinct and isolatable sound

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the ''reception'' of such waves and their ''perception'' by the br ...

s that act as the most basic building blocks for nearly all of music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

. This discretization

In applied mathematics, discretization is the process of transferring continuous functions, models, variables, and equations into discrete counterparts. This process is usually carried out as a first step toward making them suitable for numeri ...

facilitates performance, comprehension, and analysis

Analysis (: analyses) is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (38 ...

. Notes may be visually communicated by writing

Writing is the act of creating a persistent representation of language. A writing system includes a particular set of symbols called a ''script'', as well as the rules by which they encode a particular spoken language. Every written language ...

them in musical notation

Musical notation is any system used to visually represent music. Systems of notation generally represent the elements of a piece of music that are considered important for its performance in the context of a given musical tradition. The proce ...

.

Notes can distinguish the general pitch class or the specific pitch played by a pitched instrument. Although this article focuses on pitch, notes for unpitched percussion instruments distinguish between different percussion instruments (and/or different manners to sound them) instead of pitch. Note value expresses the relative duration of the note in time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

. Dynamics for a note indicate how loud to play them. Articulations may further indicate how performers should shape the attack and decay of the note and express fluctuations in a note's timbre and pitch. Notes may even distinguish the use of different extended techniques by using special symbols.

The term ''note'' can refer to a specific musical event, for instance when saying the song

A song is a musical composition performed by the human voice. The voice often carries the melody (a series of distinct and fixed pitches) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs have a structure, such as the common ABA form, and are usu ...

" Happy Birthday to You", begins with two notes of identical pitch. Or more generally, the term can refer to a class of identically sounding events, for instance when saying "the song begins with the same note repeated twice".

Distinguishing duration

A note can have a note value that indicates the note's duration relative to the musical meter. In order of halving duration, these values are: Longer note values (e.g. the longa) and shorter note values (e.g. the two hundred fifty-sixth note) do exist, but are very rare in modern times. These durations can further be subdivided using tuplets. A rhythm is formed from a sequence intime

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

of consecutive notes (without particular focus on pitch) and rests (the time between notes) of various durations.

Distinguishing pitch

Distinguishing pitches of a scale

Music theory

Music theory is the study of theoretical frameworks for understanding the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory": The first is the "Elements of music, ...

in most European countries and others use the solfège naming convention. Fixed do uses the syllable

A syllable is a basic unit of organization within a sequence of speech sounds, such as within a word, typically defined by linguists as a ''nucleus'' (most often a vowel) with optional sounds before or after that nucleus (''margins'', which are ...

s ''re–mi–fa–sol–la–ti'' specifically for the C major scale, while movable do labels notes of ''any'' major scale with that same order of syllables.

Alternatively, particularly in English- and some Dutch-speaking regions, pitch classes are typically represented by the first seven letters of the Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also known as the Roman alphabet, is the collection of letters originally used by the Ancient Rome, ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered except several letters splitting—i.e. from , and from � ...

(A, B, C, D, E, F and G), corresponding to the A minor scale. Several European countries, including Germany, use H instead of B (see for details). Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion () was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' continued to be used as a n ...

used the names ''Pa–Vu–Ga–Di–Ke–Zo–Ni'' (Πα–Βου–Γα–Δι–Κε–Ζω–Νη).

In traditional Indian music, musical notes are called svaras and commonly represented using the seven notes, Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha and Ni.

Writing notes on a staff

In a score, each note is assigned a specific vertical position on a staff position (a line or space) on the staff, as determined by the clef. Each line or space is assigned a note name. These names are memorized by musicians and allow them to know at a glance the proper pitch to play on their instruments.Accidentals

Notes that belong to thediatonic scale

In music theory a diatonic scale is a heptatonic scale, heptatonic (seven-note) scale that includes five whole steps (whole tones) and two half steps (semitones) in each octave, in which the two half steps are separated from each other by eith ...

relevant in a tonal context are called '' diatonic notes''. Notes that do not meet that criterion are called '' chromatic notes'' or '' accidentals''. Accidental symbols visually communicate a modification of a note's pitch from its tonal context. Most commonly, the sharp symbol () raises a note by a half step, while the flat symbol () lowers a note by a half step. This half step interval is also known as a semitone (which has an equal temperament

An equal temperament is a musical temperament or Musical tuning#Tuning systems, tuning system that approximates Just intonation, just intervals by dividing an octave (or other interval) into steps such that the ratio of the frequency, frequencie ...

frequency ratio of ≅ 1.0595). The natural symbol () indicates that any previously applied accidentals should be cancelled. Advanced musicians use the double-sharp symbol () to raise the pitch by two semitones, the double-flat symbol () to lower it by two semitones, and even more advanced accidental symbols (e.g. for quarter tones). Accidental symbols are placed to ''the right'' of a note's letter when written in text (e.g. F is F-sharp, B is B-flat, and C is C natural), but are placed to ''the left'' of a note's head when drawn on a staff.

Systematic alterations to any of the 7 lettered pitch classes are communicated using a key signature. When drawn on a staff, accidental symbols are positioned in a key signature to indicate that those alterations apply to all occurrences of the lettered pitch class corresponding to each symbol's position. Additional explicitly-noted accidentals can be drawn next to noteheads to override the key signature for all subsequent notes with the same lettered pitch class in that bar. However, this effect does not accumulate for subsequent accidental symbols for the same pitch class.

12-tone chromatic scale

Assuming enharmonicity, accidentals can create pitch equivalences between different notes (e.g. the note B represents the same pitch as the note C). Thus, a 12-note chromatic scale adds 5 pitch classes in addition to the 7 lettered pitch classes. The following chart lists names used in different countries for the 12 pitch classes of a chromatic scale built on C. Their corresponding symbols are in parentheses. Differences between German and English notation are highlighted in bold typeface. Although the English and Dutch names are different, the corresponding symbols are identical.Distinguishing pitches of different octaves

Two pitches that are any number ofoctave

In music, an octave (: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is an interval between two notes, one having twice the frequency of vibration of the other. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been referr ...

s apart (i.e. their fundamental frequencies are in a ratio equal to a power of two) are perceived as very similar. Because of that, all notes with these kinds of relations can be grouped under the same pitch class and are often given the same name.

The top note of a musical scale is the bottom note's second harmonic and has double the bottom note's frequency. Because both notes belong to the same pitch class, they are often called by the same name. That top note may also be referred to as the "octave

In music, an octave (: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is an interval between two notes, one having twice the frequency of vibration of the other. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been referr ...

" of the bottom note, since an octave is the interval between a note and another with double frequency.

Scientific versus Helmholtz pitch notation

Two nomenclature systems for differentiating pitches that have the same pitch class but which fall into different octaves are: #Helmholtz pitch notation

Helmholtz pitch notation is a system for naming musical notes of the Western chromatic scale. Fully described and normalized by the German scientist Hermann von Helmholtz, it uses a combination of upper and lower case letters (A to G), and t ...

, which distinguishes octaves using prime symbols and letter case

Letter case is the distinction between the letters that are in larger uppercase or capitals (more formally ''majuscule'') and smaller lowercase (more formally '' minuscule'') in the written representation of certain languages. The writing system ...

of the pitch class letter.

#* The octave below tenor C is called the "great" octave. Notes in it and are written as upper case

Letter case is the distinction between the letters that are in larger uppercase or capitals (more formally ''#Majuscule, majuscule'') and smaller lowercase (more formally ''#Minuscule, minuscule'') in the written representation of certain langua ...

letters.

#** The next lower octave is named "contra". Notes in it include a prime symbol below the note's letter.

#** Names of subsequent lower octaves are preceded with "sub". Notes in each include an additional prime symbol below the note's letter.

#* The octave starting at tenor C is called the "small" octave. Notes in it are written as lower case

Letter case is the distinction between the letters that are in larger uppercase or capitals (more formally ''majuscule'') and smaller lowercase (more formally '' minuscule'') in the written representation of certain languages. The writing system ...

letters, so tenor C itself is written c in Helmholtz notation.

#** The next higher octave is called "one-lined". Notes in it include a prime symbol above the note's letter, so middle C is written c′.

#** Names of subsequently higher octaves use higher numbers before the "lined". Notes in each include an addition prime symbol above the note's letter.

# Scientific pitch notation, where a pitch class letter (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) is followed by a subscript Arabic numeral designating a specific octave.

#* Middle C is named C4 and is the start of the 4th octave.

#** Higher octaves use successively higher number and lower octaves use successively lower numbers.

#** The lowest note on most pianos is A0, the highest is C8.

For instance, the standard 440 Hz tuning pitch is named A4 in scientific notation and instead named a′ in Helmholtz notation.

Meanwhile, the electronic musical instrument

An electronic musical instrument or electrophone is a musical instrument that produces sound using electronics, electronic circuitry. Such an instrument sounds by outputting an electrical, electronic or digital audio signal that ultimately is ...

standard called MIDI

Musical Instrument Digital Interface (; MIDI) is an American-Japanese technical standard that describes a communication protocol, digital interface, and electrical connectors that connect a wide variety of electronic musical instruments, ...

doesn't specifically designate pitch classes, but instead names pitches by counting from its lowest note: number 0 ; up chromatically to its highest: number 127 (Although the MIDI

Musical Instrument Digital Interface (; MIDI) is an American-Japanese technical standard that describes a communication protocol, digital interface, and electrical connectors that connect a wide variety of electronic musical instruments, ...

''standard'' is clear, the octaves actually played by any one MIDI

Musical Instrument Digital Interface (; MIDI) is an American-Japanese technical standard that describes a communication protocol, digital interface, and electrical connectors that connect a wide variety of electronic musical instruments, ...

device don't necessarily match the octaves shown below, especially in older instruments.)

:

Pitch frequency in hertz

Pitch is associated with the frequency of physical oscillations measured inhertz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), often described as being equivalent to one event (or Cycle per second, cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose formal expression in ter ...

(Hz) representing the number of these oscillations per second. While notes can have any arbitrary frequency, notes in more consonant music tends to have pitches with simpler mathematical ratios to each other.

Western music defines pitches around a central reference " concert pitch" of A4, currently standardized as 440 Hz. Notes played ''in tune'' with the 12 equal temperament system will be an integer

An integer is the number zero (0), a positive natural number (1, 2, 3, ...), or the negation of a positive natural number (−1, −2, −3, ...). The negations or additive inverses of the positive natural numbers are referred to as negative in ...

number of half-steps above (positive ) or below (negative ) that reference note, and thus have a frequency of:

:

Octaves automatically yield powers of two times the original frequency, since can be expressed as when is a multiple of 12 (with being the number of octaves up or down). Thus the above formula reduces to yield a power of 2 multiplied by 440 Hz:

:

Logarithmic scale

The base-2 logarithm of the above frequency–pitch relation conveniently results in a linear relationship with or : : When dealing specifically with intervals (rather than absolute frequency), the constant can be conveniently ignored, because the ''difference'' between any two frequencies and in this logarithmic scale simplifies to: : Cents are a convenient unit for humans to express finer divisions of this logarithmic scale that are of an equally- tempered semitone. Since one semitone equals 100 cents, one octave equals 12 ⋅ 100 cents = 1200 cents. Cents correspond to a ''difference'' in this logarithmic scale, however in the regular linear scale of frequency, adding 1 cent corresponds to ''multiplying'' a frequency by (≅ ).MIDI

For use with theMIDI

Musical Instrument Digital Interface (; MIDI) is an American-Japanese technical standard that describes a communication protocol, digital interface, and electrical connectors that connect a wide variety of electronic musical instruments, ...

(Musical Instrument Digital Interface) standard, a frequency mapping is defined by:

:

where is the MIDI note number. 69 is the number of semitones between C−1 (MIDI note 0) and A4.

Conversely, the formula to determine frequency from a MIDI note is:

:

Pitch names and their history

Music notation systems have used letters of the

Music notation systems have used letters of the alphabet

An alphabet is a standard set of letter (alphabet), letters written to represent particular sounds in a spoken language. Specifically, letters largely correspond to phonemes as the smallest sound segments that can distinguish one word from a ...

for centuries. The 6th century philosopher Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known simply as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480–524 AD), was a Roman Roman Senate, senator, Roman consul, consul, ''magister officiorum'', polymath, historian, and philosopher of the Early Middl ...

is known to have used the first fourteen letters of the classical Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also known as the Roman alphabet, is the collection of letters originally used by the Ancient Rome, ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered except several letters splitting—i.e. from , and from � ...

(the letter J did not exist until the 16th century),

:A B C D E F G H I K L M N O

to signify the notes of the two-octave range that was in use at the time and in modern scientific pitch notation are represented as

:A B C D E F G A B C D E F G

Though it is not known whether this was his devising or common usage at the time, this is nonetheless called ''Boethian notation''. Although Boethius is the first author known to use this nomenclature in the literature, Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

wrote of the two-octave range five centuries before, calling it the ''perfect system'' or ''complete system'' – as opposed to other, smaller-range note systems that did not contain all possible species of octave (i.e., the seven octaves starting from A, B, C, D, E, F, and G). A modified form of Boethius' notation later appeared in the ''Dialogus de musica'' (ca. 1000) by Pseudo-Odo, in a discussion of the division of the monochord.

Following this, the range (or compass) of used notes was extended to three octaves, and the system of repeating letters A–G in each octave was introduced, these being written as lower-case for the second octave (a–g) and double lower-case letters for the third (aa–gg). When the range was extended down by one note, to a G, that note was denoted using the Greek letter gamma

Gamma (; uppercase , lowercase ; ) is the third letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals it has a value of 3. In Ancient Greek, the letter gamma represented a voiced velar stop . In Modern Greek, this letter normally repr ...

(), the lowest note in Medieval music notation. (It is from this gamma that the French word for scale, derives, and the English word ''gamut'', from "gamma-ut".)

The remaining five notes of the chromatic scale (the black keys on a piano keyboard) were added gradually; the first being B, since B was flattened in certain modes to avoid the dissonant tritone interval. This change was not always shown in notation, but when written, B (B flat) was written as a Latin, cursive "", and B (B natural) a Gothic script (known as Blackletter

Blackletter (sometimes black letter or black-letter), also known as Gothic script, Gothic minuscule or Gothic type, was a script used throughout Western Europe from approximately 1150 until the 17th century. It continued to be commonly used for ...

) or "hard-edged" . These evolved into the modern flat () and natural () symbols respectively. The sharp symbol arose from a (barred b), called the "cancelled b".

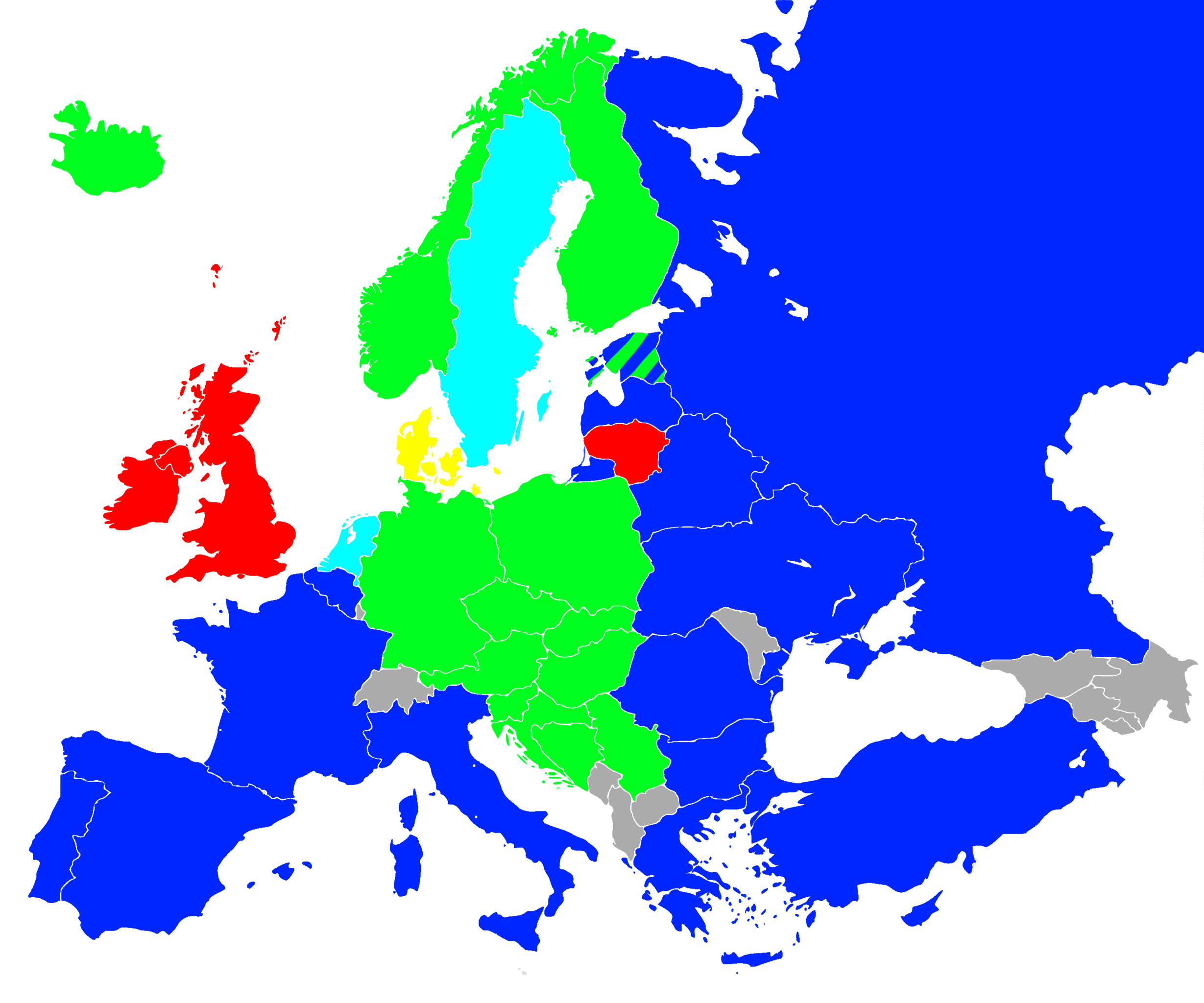

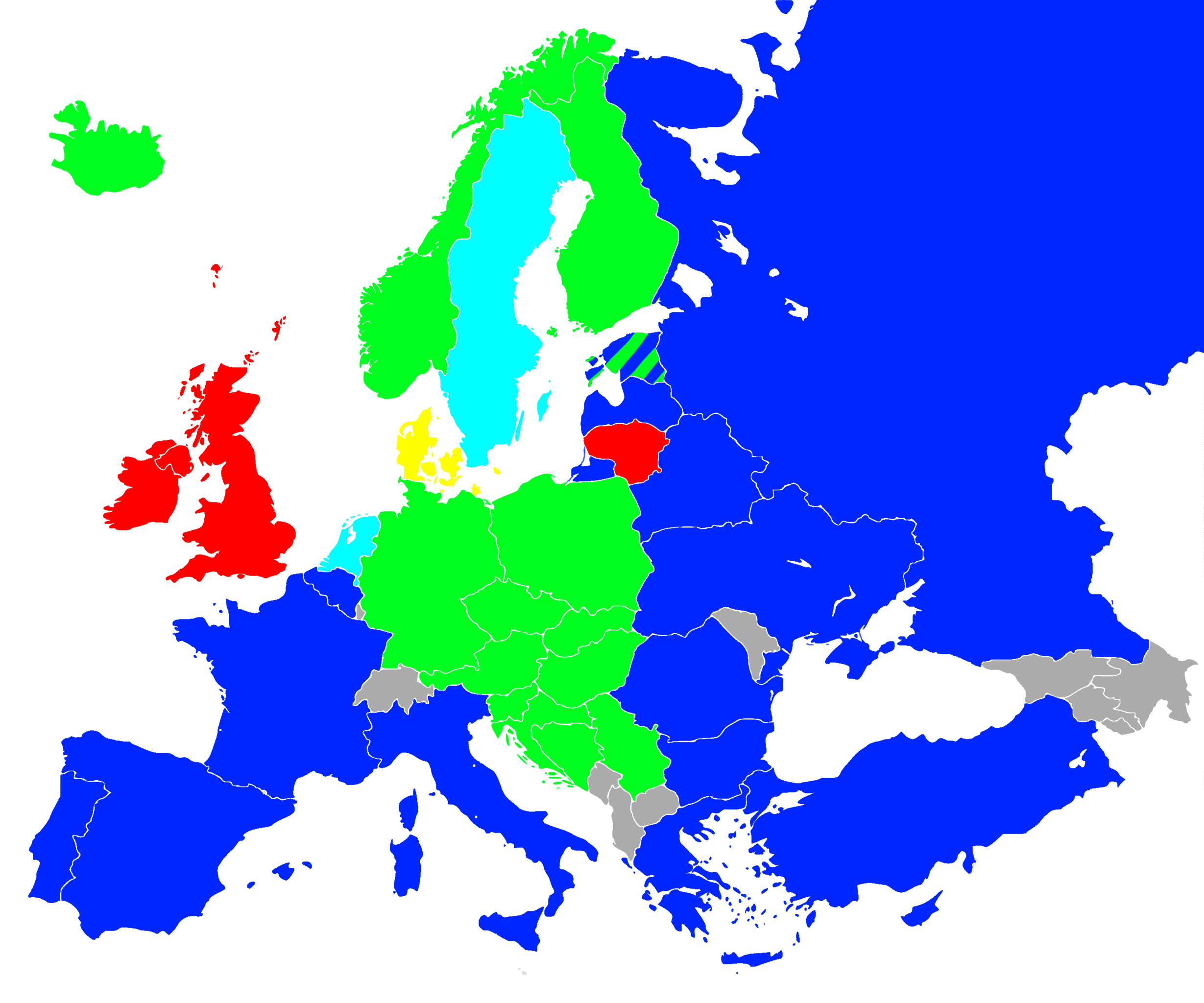

B♭, B and H

In parts of Europe, including Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, Norway, Denmark, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Finland, and Iceland (and Sweden before the 1990s), the Gothic transformed into the letter h (possibly for '' hart'', German for "harsh", as opposed to '' blatt'', German for "planar", or just because the Gothic and resemble each other). Therefore, in current German music notation, H is used instead of B (B natural), and B instead of B (B flat). Occasionally, music written in German for international use will use H for B natural and B for B flat (with a modern-script lower-case b, instead of a flat sign, ). Since a or B in Northern Europe (notated B in modern convention) is both rare and unorthodox (more likely to be expressed as Heses), it is generally clear what this notation means.System "do–re–mi–fa–sol–la–si"

In Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, French, Romanian, Greek, Albanian, Russian, Mongolian, Flemish, Persian, Arabic, Hebrew, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Turkish and Vietnamese the note names are ''do–re–mi–fa–sol–la–si'' rather than C–D–E–F–G–A–B. These names follow the original names reputedly given by Guido d'Arezzo, who had taken them from the first syllables of the first six musical phrases of a Gregorian chant melody '' Ut queant laxis'', whose successive lines began on the appropriate scale degrees. These became the basis of the solfège system. For ease of singing, the name ''ut'' was largely replaced by ''do'' (most likely from the beginning of ''Dominus'', "Lord"), though ''ut'' is still used in some places. It was the Italian musicologist and humanist Giovanni Battista Doni (1595–1647) who successfully promoted renaming the name of the note from ''ut'' to ''do''. For the seventh degree, the name ''si'' (from ''Sancte Iohannes'', St. John, to whom the hymn is dedicated), though in some regions the seventh is named ''ti'' (again, easier to pronounce while singing).See also

*Ghost note

In music, notably in jazz, a ghost note (or a dead, muted, silenced or false note) is a musical note with a rhythmic value, but no discernible pitch when played. In musical notation, this is represented by an "X" for a note head instead of ...

* Grace note

* Letter notation

* Musical tone

* Pensato

*Shape note

Shape notes are a musical notation designed to facilitate congregational and Sing-along, social singing. The notation became a popular teaching device in American singing schools during the 19th century. Shapes were added to the noteheads in ...

* Universal key

Notes

References

Bibliography

*External links

Converter: Frequencies to note name, ± cents

* ttp://www.sengpielaudio.com/calculator-notenames.htm Music notation systems − Frequencies of equal temperament tuning – The English and American system versus the German systembr>Frequencies of musical notes

{{Authority control Musical notation