Medieval literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

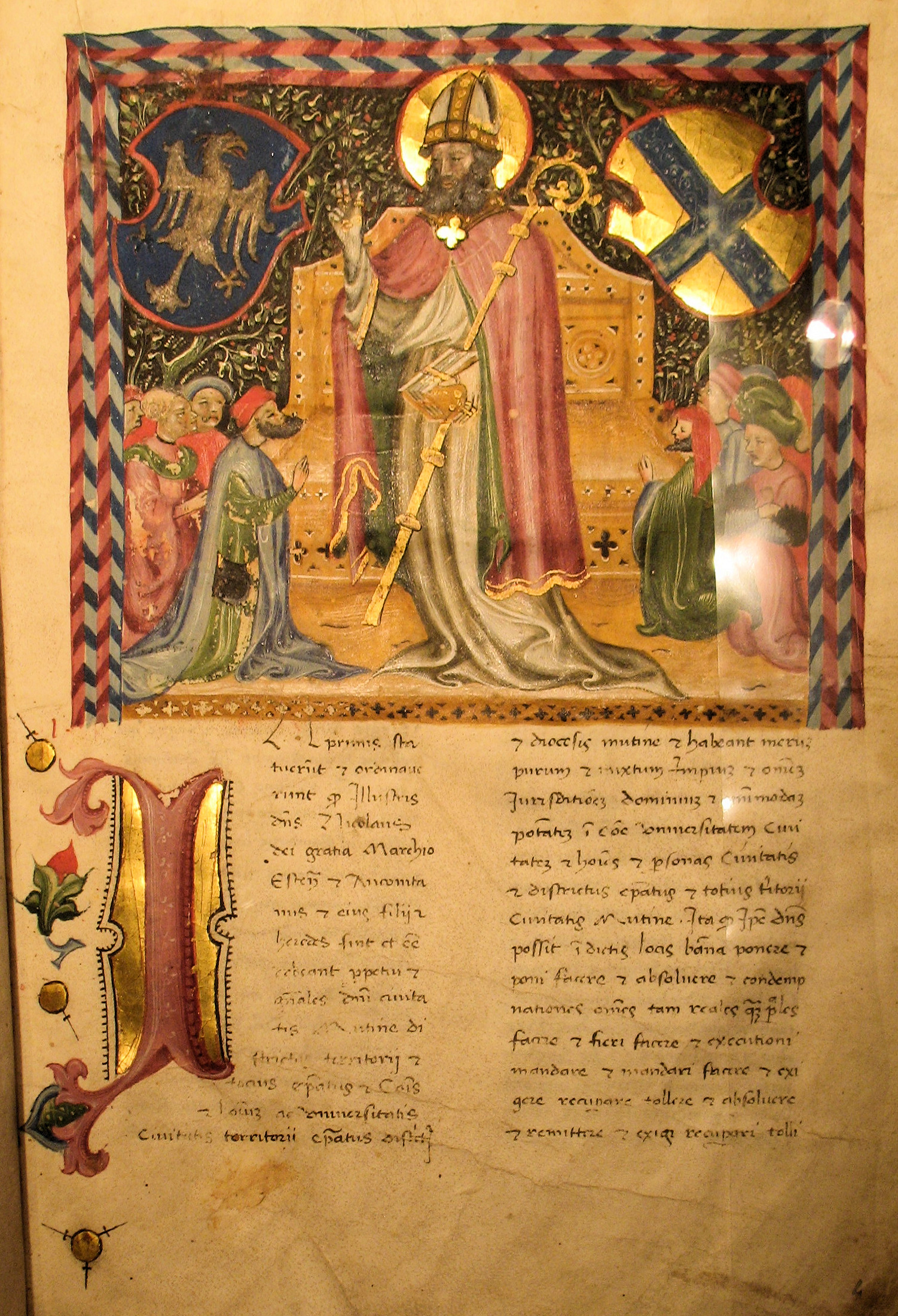

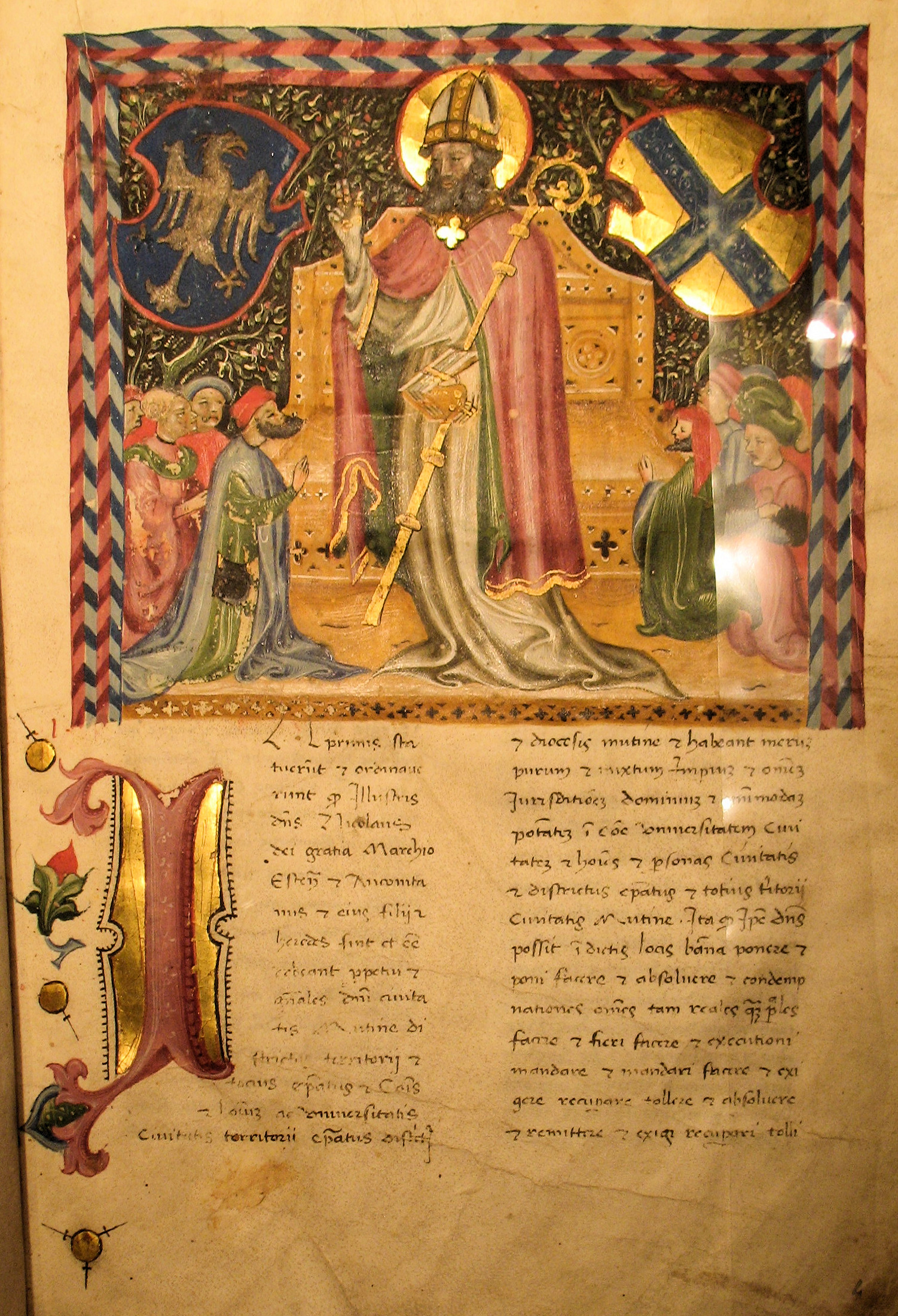

Medieval literature is a broad subject, encompassing essentially all written works available in Europe and beyond during the Middle Ages (that is, the one thousand years from the

Medieval literature is a broad subject, encompassing essentially all written works available in Europe and beyond during the Middle Ages (that is, the one thousand years from the

*''Alexiad'', Anna Comnena

*'' Beowulf'', Anonymous work, anonymous Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon author

*''Caedmon's Hymn''

*''Cantigas de Santa Maria'', Galician language literature, Galician

*''The Book of the City of Ladies'', Christine de Pizan

*''Book of the Civilized Man'', Daniel of Beccles

*''The Book of Good Love'', Juan Ruiz

*''The Book of Margery Kempe'', Margery Kempe

*''Brut (Layamon), Brut'', Layamon

*''Roman de Brut, Brut'', Wace

*''The Canterbury Tales'', Geoffrey Chaucer

*''Consolation of Philosophy'', Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, Boethius

*''David of Sassoun'', anonymous Armenian author

*''Decameron'', Giovanni Boccaccio

*''The Dialogue'',

*''Alexiad'', Anna Comnena

*'' Beowulf'', Anonymous work, anonymous Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon author

*''Caedmon's Hymn''

*''Cantigas de Santa Maria'', Galician language literature, Galician

*''The Book of the City of Ladies'', Christine de Pizan

*''Book of the Civilized Man'', Daniel of Beccles

*''The Book of Good Love'', Juan Ruiz

*''The Book of Margery Kempe'', Margery Kempe

*''Brut (Layamon), Brut'', Layamon

*''Roman de Brut, Brut'', Wace

*''The Canterbury Tales'', Geoffrey Chaucer

*''Consolation of Philosophy'', Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, Boethius

*''David of Sassoun'', anonymous Armenian author

*''Decameron'', Giovanni Boccaccio

*''The Dialogue'',

The Medieval and Classical Literature LibraryThe Labyrinth: Resources for Medieval StudiesMedieval and Renaissance manuscripts, Vulgates, Books of Hours, Medicinal Texts and more, 12 - 17th century, Center for Digital Initiatives, University of Vermont LibrariesLuminarium: Anthology of Middle English LiteratureMedieval Nordic Literature

at the Icelandic Saga Database {{Authority control Medieval literature, History of literature, 03 Medieval culture, Literature

Medieval literature is a broad subject, encompassing essentially all written works available in Europe and beyond during the Middle Ages (that is, the one thousand years from the

Medieval literature is a broad subject, encompassing essentially all written works available in Europe and beyond during the Middle Ages (that is, the one thousand years from the fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

ca. AD 500 to the beginning of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

in the 14th, 15th or 16th century, depending on country). The literature of this time was composed of religious writings as well as secular works. Just as in modern literature, it is a complex and rich field of study, from the utterly sacred to the exuberantly profane, touching all points in-between. Works of literature are often grouped by place of origin, language, and genre.

Languages

Outside of Europe, medieval literature was written in Ethiopic,Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

, Coptic

Coptic may refer to:

Afro-Asia

* Copts, an ethnoreligious group mainly in the area of modern Egypt but also in Sudan and Libya

* Coptic language, a Northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century

* Coptic alphabet ...

, Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

, Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

, and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

, among many other languages.

In Western Europe, Latin was the common language for medieval writing, since Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

was the language of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, which dominated Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

, and since the Church was virtually the only source of education. This was the case even in some parts of Europe that were never Romanized.

In Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

, the influence of the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

and the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

made Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Old Church Slavonic the dominant written languages.

In Europe the common people used their respective vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

s. A few examples, such as the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

'' Beowulf'', the Middle High German

Middle High German (MHG; german: Mittelhochdeutsch (Mhd.)) is the term for the form of German spoken in the High Middle Ages. It is conventionally dated between 1050 and 1350, developing from Old High German and into Early New High German. Hig ...

''Nibelungenlied

The ( gmh, Der Nibelunge liet or ), translated as ''The Song of the Nibelungs'', is an epic poem written around 1200 in Middle High German. Its anonymous poet was likely from the region of Passau. The is based on an oral tradition of Germani ...

'', the Medieval Greek

Medieval Greek (also known as Middle Greek, Byzantine Greek, or Romaic) is the stage of the Greek language between the end of classical antiquity in the 5th–6th centuries and the end of the Middle Ages, conventionally dated to the Fall of Co ...

''Digenis Acritas

''Digenes Akritas'', ) is a variant of ''Akritas''. Sometimes it is further latinized as ''Acritis'' or ''Acritas''. ( el, Διγενῆς Ἀκρίτας, ) is the most famous of the Acritic songs and is often regarded as the only surviving epic ...

'', the Old East Slavic ''Tale of Igor's Campaign

''The Tale of Igor's Campaign'' ( orv, Слово о пълкѹ Игоревѣ, translit=Slovo o pŭlku Igorevě) is an anonymous epic poem written in the Old East Slavic language.

The title is occasionally translated as ''The Tale of the Campaig ...

'', and the Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

''Chanson de Roland

''The Song of Roland'' (french: La Chanson de Roland) is an 11th-century ''chanson de geste'' based on the Frankish military leader Roland at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778 AD, during the reign of the Carolingian king Charlemagne. It is ...

'', are well known to this day. Although the extant versions of these epics

The Experimental Physics and Industrial Control System (EPICS) is a set of software tools and applications used to develop and implement distributed control systems to operate devices such as particle accelerators, telescopes and other large sci ...

are generally considered the works of individual (but anonymous) poets, there is no doubt that they are based on their peoples' older oral traditions. Celtic traditions have survived in the lais of Marie de France

Marie de France ( fl. 1160 to 1215) was a poet, possibly born in what is now France, who lived in England during the late 12th century. She lived and wrote at an unknown court, but she and her work were almost certainly known at the royal court ...

, the '' Mabinogion'' and the Arthurian cycles. Another host of vernacular literature has survived in the Old Norse literature

Old Norse literature refers to the vernacular literature of the Scandinavian peoples up to c. 1350. It chiefly consists of Icelandic writings.

In Britain

From the 8th to the 15th centuries, Vikings and Norse settlers and their descendants colon ...

and more specifically in the saga literature of Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

.

Anonymity

A notable amount of medieval literature is anonymous. This is not only due to the lack of documents from a period, but also due to an interpretation of theauthor

An author is the writer of a book, article, play, mostly written work. A broader definition of the word "author" states:

"''An author is "the person who originated or gave existence to anything" and whose authorship determines responsibility f ...

's role that differs considerably from the romantic interpretation of the term in use today. Medieval authors often deeply respected the classical writers and the Church Fathers and tended to re-tell and embellish stories they had heard or read rather than invent new stories. And even when they did, they often claimed to be handing down something from an '' auctor'' instead. From this point of view, the names of the individual authors seemed much less important, and therefore many important works were never attributed to any specific person.

Types of writing

Religious

Theological works were the dominant form of literature typically found in libraries during the Middle Ages.Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

clerics were the intellectual center of society in the Middle Ages, and it is their literature that was produced in the greatest quantity.

Countless hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hy ...

s survive from this time period (both liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

and paraliturgical). The liturgy itself was not in fixed form, and numerous competing missals set out individual conceptions of the order of the mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

. Religious scholars such as Anselm of Canterbury, Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wit ...

, and Pierre Abélard

Peter Abelard (; french: link=no, Pierre Abélard; la, Petrus Abaelardus or ''Abailardus''; 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, poet, composer and musician. This source has a detailed de ...

wrote lengthy theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the s ...

and philosophical

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

treatises, often attempting to reconcile the teachings of the Greek and Roman pagan authors with the doctrines of the Church. Hagiographies

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies might ...

, or "lives of the saints", were also frequently written, as an encouragement to the devout and a warning to others.

The ''Golden Legend

The ''Golden Legend'' (Latin: ''Legenda aurea'' or ''Legenda sanctorum'') is a collection of hagiographies by Jacobus de Voragine that was widely read in late medieval Europe. More than a thousand manuscripts of the text have survived.Hilary ...

'' of Jacobus de Voragine

Jacobus de Voragine (c. 123013/16 July 1298) was an Italian chronicler and archbishop of Genoa. He was the author, or more accurately the compiler, of the '' Golden Legend'', a collection of the legendary lives of the greater saints of the medi ...

reached such popularity that, in its time, it was reportedly read more often than the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

. Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christianit ...

was a prolific poet, and his Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

followers frequently wrote poetry themselves as an expression of their piety. '' Dies Irae'' and '' Stabat Mater'' are two of the most powerful Latin poems on religious subjects. Goliardic poetry

The goliards were a group of generally young clergy in Europe who wrote satirical Latin poetry in the 12th and 13th centuries of the Middle Ages. They were chiefly clerics who served at or had studied at the universities of France, Germany, Spai ...

(four-line stanzas of satiric verse) was an art form used by some clerics to express dissent. The only widespread religious writing that was not produced by clerics were the mystery play

Mystery plays and miracle plays (they are distinguished as two different forms although the terms are often used interchangeably) are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the represe ...

s: growing out of simple tableaux

The International Conference on Automated Reasoning with Analytic Tableaux and Related Methods (TABLEAUX) is an annual international academic conference that deals with all aspects of automated reasoning with analytic tableaux. Periodically, it jo ...

re-enactments of a single Biblical scene, each mystery play became its village's expression of the key events in the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

. The text of these plays was often controlled by local guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s, and mystery plays would be performed regularly on set feast-days, often lasting all day long and into the night.

During the Middle Ages, the Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

ish population of Europe also produced a number of outstanding writers. Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

, born in Cordoba, Spain, and Rashi

Shlomo Yitzchaki ( he, רבי שלמה יצחקי; la, Salomon Isaacides; french: Salomon de Troyes, 22 February 1040 – 13 July 1105), today generally known by the acronym Rashi (see below), was a medieval French rabbi and author of a compre ...

, born in Troyes, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, are two of the best-known and most influential of these Jewish authors.

Secular

Secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

literature in this period was not produced in equal quantity as religious literature. The earliest tales are based on oral traditions: the British ''Y Gododdin

''Y Gododdin'' () is a medieval Welsh poem consisting of a series of elegies to the men of the Brittonic kingdom of Gododdin and its allies who, according to the conventional interpretation, died fighting the Angles of Deira and Bernicia a ...

'' and ''Preiddeu Annwfn

''Preiddeu Annwfn'' or ''Preiddeu Annwn'' ( en, The Spoils of Annwfn) is a cryptic poem of sixty lines in Middle Welsh, found in the Book of Taliesin. The text recounts an expedition with King Arthur to Annwfn or Annwn, the Welsh name for the ...

'', along with the Germanic '' Beowulf'' and ''Nibelungenlied

The ( gmh, Der Nibelunge liet or ), translated as ''The Song of the Nibelungs'', is an epic poem written around 1200 in Middle High German. Its anonymous poet was likely from the region of Passau. The is based on an oral tradition of Germani ...

''. They relate to myths or certain 6th-century events, but the surviving manuscripts date from centuries later—''Y Gododdin'' from the late 13th century, ''Preiddu Annwfn'' from the early 14th century, ''Beowulf'' from c. 1000, and the ''Nibelungenlied'' from the 13th century. The makers and performers were '' bards'' (British/Welsh) and ''scop

A (

or ) was a poet as represented in Old English poetry. The scop is the Old English counterpart of the Old Norse ', with the important difference that "skald" was applied to historical persons, and scop is used, for the most part, to designa ...

s'' (Germanic), elite professionals attached to royal or noble courts to praise the heroes of legendary history.

Prose tales first emerged in Britain: the intricate Four Branches of the ''Mabinogi'' about princely families, notably anti-war in theme, and the romantic adventure ''Culhwch and Olwen

''Culhwch and Olwen'' ( cy, Culhwch ac Olwen) is a Welsh tale that survives in only two manuscripts about a hero connected with Arthur and his warriors: a complete version in the Red Book of Hergest, c. 1400, and a fragmented version in the Whi ...

''. (The ''Mabinogi'' is not the same as the '' Mabinogion'', a collection of disconnected prose tales, which does, however, include both the ''Mabinogi'' and ''Culhwch and Olwen''.) These works were compiled from earlier oral tradition c. 1100.

At about the same time a new poetry of " courtly love" became fashionable in Europe. Traveling singers—troubadour

A troubadour (, ; oc, trobador ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a ''trobairi ...

s and trouvère

''Trouvère'' (, ), sometimes spelled ''trouveur'' (, ), is the Northern French ('' langue d'oïl'') form of the '' langue d'oc'' (Occitan) word ''trobador'', the precursor of the modern French word ''troubadour''. ''Trouvère'' refers to poet ...

s—made a living from their love songs in French, Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

, Galician-Portuguese

Galician-Portuguese ( gl, galego-portugués or ', pt, galego-português or ), also known as Old Portuguese or as Medieval Galician when referring to the history of each modern language, was a West Iberian Romance language spoken in the Middle ...

, Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

, Provençal, and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

. Germanic culture had its Minnesänger

(; "love song") was a tradition of lyric- and song-writing in Germany and Austria that flourished in the Middle High German period. This period of medieval German literature began in the 12th century and continued into the 14th. People who wr ...

tradition. The songs of courtly love often express unrequited longing for an ideal woman, but there are also aubade

An aubade is a morning love song (as opposed to a serenade, intended for performance in the evening), or a song or poem about lovers separating at dawn. It has also been defined as "a song or instrumental composition concerning, accompanying, or ev ...

s (dawn farewells by lovers) and humorous ditties.

Following the earliest epic poems, prose tales, and romances, more long poems were crafted—the '' chansons de geste'' of the late 11th and early 12th centuries. These extolled conquests, as in ''The Song of Roland

''The Song of Roland'' (french: La Chanson de Roland) is an 11th-century '' chanson de geste'' based on the Frankish military leader Roland at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778 AD, during the reign of the Carolingian king Charlemagne. It i ...

'' (part of the Matter of France) and ''Digenis Acritas

''Digenes Akritas'', ) is a variant of ''Akritas''. Sometimes it is further latinized as ''Acritis'' or ''Acritas''. ( el, Διγενῆς Ἀκρίτας, ) is the most famous of the Acritic songs and is often regarded as the only surviving epic ...

'' (one of the Acritic songs

The Acritic songs ( "frontiersmen songs") are the epic poems that emerged in the Byzantine Empire probably around the ninth century. The songs celebrated the exploits of the Akritai, the frontier guards defending the eastern borders of the Byzant ...

). The rather different chivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of High Medieval and Early Modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalri ...

tradition concerns adventures about marvels, love, and chivalry. They tell of the Matter of Britain

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Wester ...

and the Matter of Rome

According to the medieval poet Jean Bodel, the Matter of Rome is the literary cycle of Greek and Roman mythology, together with episodes from the history of classical antiquity, focusing on military heroes like Alexander the Great and Julius Cae ...

.

Political poetry

Political poetry brings together politics and poetry. According to "The Politics of Poetry"by David Orr, poetry and politics connect through expression and feeling, although both of them are matters of persuasion. Political poetry connects to peop ...

threads throughout the period from the very early ''Armes Prydein

''Armes Prydein'' (, ''The Prophecy of Britain'') is an early 10th-century Welsh prophetic poem from the '' Book of Taliesin''.

In a rousing style characteristic of Welsh heroic poetry, it describes a future where all of Brythonic peoples are a ...

'' (10th-century Britain) to the goliard

The goliards were a group of generally young clergy in Europe who wrote satirical Latin poetry in the 12th and 13th centuries of the Middle Ages. They were chiefly clerics who served at or had studied at the universities of France, Germany, ...

rebels of 12th and 13th centuries, who were church trained clerics unable or unwilling to be employed in the church.

Travel literature was highly popular in the Middle Ages, as fantastic accounts of far-off lands (frequently embellished or entirely false) entertained a society that supported sea voyages and trading along coasts and rivers, as well as pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

s to such destinations as Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

; Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of ...

and Glastonbury

Glastonbury (, ) is a town and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated at a dry point on the low-lying Somerset Levels, south of Bristol. The town, which is in the Mendip district, had a population of 8,932 in the 2011 census. Glastonbur ...

in England; St. David's in Wales; and Santiago de Compostela

Santiago de Compostela is the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia, in northwestern Spain. The city has its origin in the shrine of Saint James the Great, now the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as the destination of the Way of St ...

in Spain. Geoffrey Chaucer's ''Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' ( enm, Tales of Caunterbury) is a collection of twenty-four stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. It is widely regarded as Chaucer's ''magnum opus ...

'' became popular at the end of the 14th century.

The most prominent authors of Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

secular poetry in the Middle Ages were Solomon ibn Gabirol and Yehuda Halevi

Judah Halevi (also Yehuda Halevi or ha-Levi; he, יהודה הלוי and Judah ben Shmuel Halevi ; ar, يهوذا اللاوي ''Yahuḏa al-Lāwī''; 1075 – 1141) was a Spanish Jewish physician, poet and philosopher. He was born in Spain, ...

, both of whom were also renowned religious poets.

Women's literature

While it is true that women in the medieval period were never accorded full equality with men, some women were able to use their skill with the written word to gain renown. Religious writing was the easiest avenue—women who would later be canonized assaint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

s frequently published their reflections, revelations, and prayers. Much of what is known about women in the Middle Ages

Women in the Middle Ages in Europe occupied a number of different social roles. Women held the positions of wife, mother, peasant, artisan, and nun, as well as some important leadership roles, such as abbess or queen regnant. The very concept of ...

is known from the works of nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is o ...

s such as Clare of Assisi, Bridget of Sweden

Bridget of Sweden (c. 1303 – 23 July 1373) born as Birgitta Birgersdotter, also Birgitta of Vadstena, or Saint Birgitta ( sv, heliga Birgitta), was a mystic and a saint, and she was also the founder of the Bridgettines nuns and monks after ...

, and Catherine of Siena

Catherine of Siena (Italian: ''Caterina da Siena''; 25 March 1347 – 29 April 1380), a member of the Third Order of Saint Dominic, was a mystic, activist, and author who had a great influence on Italian literature and on the Catholic Church ...

.

Frequently, however, the religious perspectives of women were held to be unorthodox by those in power, and the mystical visions of such authors as Julian of Norwich, Mechthild of Magdeburg, and Hildegard of Bingen provide insight into a part of the medieval experience less comfortable for the institutions that ruled Europe at the time. Women wrote influential texts in the secular realm as well—reflections on courtly love and society by Marie de France

Marie de France ( fl. 1160 to 1215) was a poet, possibly born in what is now France, who lived in England during the late 12th century. She lived and wrote at an unknown court, but she and her work were almost certainly known at the royal court ...

and Christine de Pizan continue to be studied for their glimpses of medieval society.

Some women were patrons of books and owners of significant book collections. Female book collectors in the fifteenth century included Alice Chaucer, Duchess of Suffolk; Cecily Neville, Duchess of York; and Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby. Lady Margaret Beaufort may also have completed translations as a testament to her piety, as Bishop Father John Fisher noted in a sermon dedicated to her after her death.

For modern historical reflection, D.H. Green's (2007) historical work entitled, ''Women Readers of the Middle Ages'' explores literacy and literature in terms of women in medieval society. The book has been reviewed as "a radical reassessment of women's contribution to medieval literary culture."

Allegory

While medieval literature makes use of many literary devices, allegory is so prominent in this period as to deserve special mention. Much of medieval literature relied on allegory to convey the morals the author had in mind while writing—representations of abstract qualities, events, and institutions are thick in much of the literature of this time. Probably the earliest and most influential allegory is the ''Psychomachia'' (''Battle of Souls'') by Aurelius Clemens Prudentius. Other important examples include the ''Romance of the Rose'', ''Everyman (15th-century play), Everyman'', ''Piers Plowman'', the ''Roman de Fauvel'', and the ''Divine Comedy''.Preservation

A recent study has concluded that only about 68 percent of all medieval works have survived to the present day, including fewer than 40 percent of English language, English works, around 50 percent of Dutch language, Dutch and French works, and more than three quarters of German language, German, Icelandic language, Icelandic, and Irish language, Irish works.Notable literature of the period

*''Alexiad'', Anna Comnena

*'' Beowulf'', Anonymous work, anonymous Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon author

*''Caedmon's Hymn''

*''Cantigas de Santa Maria'', Galician language literature, Galician

*''The Book of the City of Ladies'', Christine de Pizan

*''Book of the Civilized Man'', Daniel of Beccles

*''The Book of Good Love'', Juan Ruiz

*''The Book of Margery Kempe'', Margery Kempe

*''Brut (Layamon), Brut'', Layamon

*''Roman de Brut, Brut'', Wace

*''The Canterbury Tales'', Geoffrey Chaucer

*''Consolation of Philosophy'', Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, Boethius

*''David of Sassoun'', anonymous Armenian author

*''Decameron'', Giovanni Boccaccio

*''The Dialogue'',

*''Alexiad'', Anna Comnena

*'' Beowulf'', Anonymous work, anonymous Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon author

*''Caedmon's Hymn''

*''Cantigas de Santa Maria'', Galician language literature, Galician

*''The Book of the City of Ladies'', Christine de Pizan

*''Book of the Civilized Man'', Daniel of Beccles

*''The Book of Good Love'', Juan Ruiz

*''The Book of Margery Kempe'', Margery Kempe

*''Brut (Layamon), Brut'', Layamon

*''Roman de Brut, Brut'', Wace

*''The Canterbury Tales'', Geoffrey Chaucer

*''Consolation of Philosophy'', Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, Boethius

*''David of Sassoun'', anonymous Armenian author

*''Decameron'', Giovanni Boccaccio

*''The Dialogue'', Catherine of Siena

Catherine of Siena (Italian: ''Caterina da Siena''; 25 March 1347 – 29 April 1380), a member of the Third Order of Saint Dominic, was a mystic, activist, and author who had a great influence on Italian literature and on the Catholic Church ...

*''Digenis Acritas

''Digenes Akritas'', ) is a variant of ''Akritas''. Sometimes it is further latinized as ''Acritis'' or ''Acritas''. ( el, Διγενῆς Ἀκρίτας, ) is the most famous of the Acritic songs and is often regarded as the only surviving epic ...

'', Anonymous work, anonymous Greek literature, Greek author

*''The Diseases of Women'', Trotula of Salerno

*''The Divine Comedy, La divina commedia'' (''The Divine Comedy''), Dante Alighieri

*''Dukus Horant'', the first extended work in Yiddish.

*''Elder Edda'', various Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

ic authors

*''Das fließende Licht der Gottheit'', Mechthild of Magdeburg

*''First Grammatical Treatise'', 12th-century work on Old Norse phonology

*''Gesta Danorum'', Saxo Grammaticus

*''Heimskringla'', Snorri Sturluson

*''Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum'' (''The Ecclesiastical History of the English People''), the Venerable Bede

*''Holy Cross Sermons'', anonymous Poland, Polish author

*''The Knight in the Panther Skin'', Shota Rustaveli

*''The Lais of Marie de France'', Marie de France

Marie de France ( fl. 1160 to 1215) was a poet, possibly born in what is now France, who lived in England during the late 12th century. She lived and wrote at an unknown court, but she and her work were almost certainly known at the royal court ...

*''The Letters of Abelard and Heloise''

*''Libro de los ejemplos del conde Lucanor y de Patronio'' (''Book of the Examples of Count Lucanor and of Patronio''), Don Juan Manuel, Prince of Villena

*''Ludus de Antichristo'', anonymous Germany, German author

*'' Mabinogion'', various Wales, Welsh authors

*''Metrical Dindshenchas'', Irish literature, Irish onomastic poems

*''The Travels of Marco Polo, Il milione'' (''The Travels of Marco Polo''), Marco Polo

*''Le Morte d'Arthur'', Sir Thomas Malory

*''Nibelungenlied

The ( gmh, Der Nibelunge liet or ), translated as ''The Song of the Nibelungs'', is an epic poem written around 1200 in Middle High German. Its anonymous poet was likely from the region of Passau. The is based on an oral tradition of Germani ...

'', anonymous Germany, German author

*''Njál's saga'', anonymous Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

ic author

*''Parzival'', Wolfram von Eschenbach

*''Piers Plowman'', William Langland

*''Cantar de Mio Cid, Poem of the Cid'', anonymous Spain, Spanish author

*''Proslogion, Proslogium'', Anselm of Canterbury

*''Queste del Saint Graal'' (''The Quest of the Holy Grail''), anonymous France, French author

*''Revelations of Divine Love'', Julian of Norwich

*''Le Roman de Perceforest''

*''Roman de la Rose'', Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun

*''Sadko'', anonymous Rus' (people), Russian author

*''Scivias'', Hildegard of Bingen

*''Sic et Non'', Abelard

*''Sir Gawain and the Green Knight'', anonymous English people, English author

*''The Song of Roland

''The Song of Roland'' (french: La Chanson de Roland) is an 11th-century '' chanson de geste'' based on the Frankish military leader Roland at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778 AD, during the reign of the Carolingian king Charlemagne. It i ...

'', anonymous France, French author

*''Gertrude the Great, Spiritual Exercises'', Gertrude the Great

*''Summa Theologica, Summa Theologiae'', Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wit ...

*''Táin Bó Cúailnge'', anonymous Ireland, Irish author

*''The Tale of Igor's Campaign'', anonymous Rus' (people), Russian author

*''Tirant lo Blanc'', Joanot Martorell

*''The Travels of Sir John Mandeville'', John Mandeville

*''Tristan'', Thomas d'Angleterre

*''Tristan'', Béroul

*''Tristan'', Gottfried von Strassburg

*''Troilus and Criseyde'', Geoffrey Chaucer

*''Waltharius''

*''Younger Edda'', Snorri Sturluson

*''Yvain: The Knight of the Lion'', Chrétien de Troyes

Specific articles

By region or language

*Anglo-Norman literature *Arabic literature#Classical Arabic literature, Classical Arabic literature *Armenian literature#Medieval era, Medieval Armenian literature *Medieval literacy of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Medieval Bosnian literature *Breton literature, Old Breton literature *Byzantine literature *Medieval Bulgarian literature *Catalan literature#Middle Ages, Medieval Catalan literature *Croatian literature#Croatian medieval literature, Medieval Croatian literature *Dutch literature, Old and Middle Dutch literature *Old English literature *Middle English literature *Early English Jewish literature *Medieval French literature *Sicilian School *Old High German literature *Middle High German literature *Georgian literature#Literary and other written works, Medieval Georgian literature *Medieval Hebrew literature *Icelandic literature *Irish literature#Early and medieval literature, Medieval Irish literature *Italian literature, Medieval Italian literature *Medieval Latin literature **Latin translations of the 12th century *Occitan literature *Old Norse literature

Old Norse literature refers to the vernacular literature of the Scandinavian peoples up to c. 1350. It chiefly consists of Icelandic writings.

In Britain

From the 8th to the 15th centuries, Vikings and Norse settlers and their descendants colon ...

*Pahlavi literature

*Persian literature#Persian literature of the medieval and pre-modern periods, Medieval Persian literature

*Portuguese literature, Medieval Portuguese literature

*Medieval Serbian literature

*Scottish literature, Medieval Scottish literature

*Medieval Spanish literature

*Medieval Welsh literature

By genre

*Medieval poetry *Medieval drama *Medieval allegory *Christian mysticism#Middle ages, Medieval mysticism *Fabliau *Medieval travel literature *Arthurian literature *Alexander romances *Chanson de geste *Chivalric romance *Eddic poetry *Skaldic poetry *Alliterative verse *Miracle plays *Morality plays *Mystery plays *Passion playsBy period

*Early Medieval literature (6th to 9th centuries) *10th century in literature *11th century in literature *12th century in literature *13th century in literature *14th century in literatureReferences

External links

The Medieval and Classical Literature Library

at the Icelandic Saga Database {{Authority control Medieval literature, History of literature, 03 Medieval culture, Literature