Massachusetts in the American Civil War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

Massachusetts played a major role in the causes of the

Massachusetts played a major role in the causes of the

Governor Andrew took office in January 1861, just two weeks after the secession of South Carolina. Convinced that war was imminent, Andrew took rapid measures to prepare the state militia for active duty. On April 15, 1861, Andrew received a telegraph from

Governor Andrew took office in January 1861, just two weeks after the secession of South Carolina. Convinced that war was imminent, Andrew took rapid measures to prepare the state militia for active duty. On April 15, 1861, Andrew received a telegraph from

One of the best-known regiments formed in Massachusetts was the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first regiment in the Union army consisting of

One of the best-known regiments formed in Massachusetts was the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first regiment in the Union army consisting of

Generals from Massachusetts commanded several army departments, and included a commander of the Army of the Potomac as well as a number of army corps commanders.

One of the most prominent generals from Massachusetts was Maj. Gen.

Generals from Massachusetts commanded several army departments, and included a commander of the Army of the Potomac as well as a number of army corps commanders.

One of the most prominent generals from Massachusetts was Maj. Gen.

The advanced state of industrialization in the North, as compared with the Confederate states, was a major factor in the victory of Union armies. Massachusetts, and the

The advanced state of industrialization in the North, as compared with the Confederate states, was a major factor in the victory of Union armies. Massachusetts, and the

Several instrumental leaders of soldiers' aid and relief organizations came from Massachusetts. These included

Several instrumental leaders of soldiers' aid and relief organizations came from Massachusetts. These included

In all, 12,976 servicemen from Massachusetts died during the war, about eight percent of those who enlisted and about one percent of the state's population (the population of Massachusetts in 1860 was 1,231,066). Official statistics are not available for the number of wounded. Across the nation, organizations such as the

In all, 12,976 servicemen from Massachusetts died during the war, about eight percent of those who enlisted and about one percent of the state's population (the population of Massachusetts in 1860 was 1,231,066). Official statistics are not available for the number of wounded. Across the nation, organizations such as the

online

* Rorabaugh, William J. "Who Fought for the North in the Civil War? Concord, Massachusetts, Enlistments," ''Journal of American History'' 73 (December 1986): 695–70

online

* Ware, Edith E. ''Political Opinion in Massachusetts during the Civil War and Reconstruction'', (1916)

full text online

Massachusetts Civil War Monuments Project

John A. Andrew Papers

at the

Civil War correspondence, diaries, and journals

at the Massachusetts Historical Society

Massachusetts National Guard Museum and Archives

{{Authority control

Commonwealth of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' E ...

played a significant role in national events prior to and during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

(1861-1865). Massachusetts dominated the early antislavery movement during the 1830s, motivating activists across the nation. This, in turn, increased sectionalism in the North and South, one of the factors that led to the war. Politicians from Massachusetts, echoing the views of social activists, further increased national tensions. The state was dominated by the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

and was also home to many Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recon ...

leaders who promoted harsh treatment of slave owners and, later, the former civilian leaders of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

and the military officers in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

.

Once hostilities began, Massachusetts supported the war effort in several significant ways, sending 159,165 men to serve in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

and the Union Navy

The Union Navy was the United States Navy (USN) during the American Civil War, when it fought the Confederate States Navy (CSN). The term is sometimes used carelessly to include vessels of war used on the rivers of the interior while they were un ...

for the loyal North. One of the best known Massachusetts units was the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that saw extensive service in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The unit was the second African-American regiment, following the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry ...

, the first regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscript ...

of African American soldiers (led by white officers). Additionally, a number of important generals came from Massachusetts, including Benjamin F. Butler, Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

, who commanded the Federal Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

in early 1863, as well as Edwin V. Sumner

Edwin Vose Sumner (January 30, 1797March 21, 1863) was a career United States Army officer who became a Union Army general and the oldest field commander of any Army Corps on either side during the American Civil War. His nicknames "Bull" or "B ...

and Darius N. Couch

Darius Nash Couch (July 23, 1822 – February 12, 1897) was an American soldier, businessman, and naturalist. He served as a career U.S. Army officer during the Mexican–American War, the Second Seminole War, and as a general officer in the Uni ...

, who both successively commanded the II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

of the Union Army.

In terms of war materiel, Massachusetts, as a leading center of industry and manufacturing, was poised to become a major producer of munitions and supplies. The most important source of armaments in Massachusetts was the Springfield Armory

The Springfield Armory, more formally known as the United States Armory and Arsenal at Springfield located in the city of Springfield, Massachusetts, was the primary center for the manufacture of United States military firearms from 1777 until ...

of the United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army, ...

.

The state also made important contributions to relief efforts. Many leaders of nursing and soldiers' aid organizations hailed from Massachusetts, including Dorothea Dix

Dorothea Lynde Dix (April 4, 1802July 17, 1887) was an American advocate on behalf of the indigent mentally ill who, through a vigorous and sustained program of lobbying state legislatures and the United States Congress, created the first gen ...

, founder of the Army Nurses Bureau, the Rev. Henry Whitney Bellows, founder of the United States Sanitary Commission

The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was a private relief agency created by federal legislation on June 18, 1861, to support sick and wounded soldiers of the United States Army (Federal / Northern / Union Army) during the American Civil ...

, and independent nurse Clara Barton

Clarissa Harlowe Barton (December 25, 1821 – April 12, 1912) was an American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse in the American Civil War, a teacher, and a patent clerk. Since nursing education was not then very ...

, future founder of the American Red Cross

The American Red Cross (ARC), also known as the American National Red Cross, is a non-profit humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. It is the des ...

.

Antebellum and wartime politics

Massachusetts played a major role in the causes of the

Massachusetts played a major role in the causes of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, particularly with regard to the political ramifications of the antislavery abolitionist movement. Antislavery activists in Massachusetts sought to influence public opinion and applied moral and political pressure on the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

to abolish slavery. William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he fo ...

(1805-1879), of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

began publishing the antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'' and founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society

The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, headquartered in Boston, was organized as an auxiliary of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1835. Its roots were in the New England Anti-Slavery Society, organized by William Lloyd Garrison, editor of ' ...

in 1831, becoming one of the nation's most influential editors and abolitionists. Garrison and his uncompromising rhetoric provoked a backlash both in the North and South and escalated regional tension prior to the war.

By the late 1850s, the antislavery Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

became the dominant political organization in several northeastern states. Prominent Republican leaders from Massachusetts included U.S. Senators

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

and Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 ...

who espoused Garrison's views and further increased sectionalism. In 1856, Sumner delivered a scathing speech in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

at the criticizing and insulting pro-slavery southern politicians. This prompted Representative Preston Brooks

Preston Smith Brooks (August 5, 1819 – January 27, 1857) was an American politician and member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina, serving from 1853 until his resignation in July 1856 and again from August 1856 until his ...

of South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

to later attack Senator Sumner on the Senate floor, severely beating him over the head and shoulders with a cane. Sumner was so severely injured that he did not return to his Senate duties for several months. The incident further heightened sectional tensions.

By 1860, the Republicans controlled the Governor's office and the General Court of Massachusetts. During the 1860 presidential election, 63 percent of Massachusetts voters supported Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

and the Republican Party, 20 percent supported Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

of the northern wing of the Democratic Party, 13 percent supported John Bell and the temporary third party Constitutional Union Party and 4 percent supported John C. Breckinridge. Support for the Republican Party increased during the war years, with 72 percent voting for Lincoln for reelection in the Election of 1864.

The dominant political figure in Massachusetts during the war was 25th Governor John Albion Andrew

John Albion Andrew (May 31, 1818 – October 30, 1867) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts. He was elected in 1860 as the 25th Governor of Massachusetts, serving between 1861 and 1866, and led the state's contributions to ...

a staunch Republican who energetically supported the war effort. Massachusetts annually re-elected him by large margins for the duration of the war—his smallest margin of victory occurred in 1860 for his first election, with 61 percent of the popular vote and his largest later in 1863 with 71 percent.

Recruitment

Massachusetts sent a total of 159,165 men to serve in the war. Of these, 133,002 served in the Union army and 26,163 served in the navy. The army units raised in Massachusetts consisted of 62 regiments ofinfantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

, six regiments of cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

, 16 batteries

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

of light artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieg ...

, four regiments of heavy artillery, two companies of sharpshooters

A sharpshooter is one who is highly proficient at firing firearms or other projectile weapons accurately. Military units composed of sharpshooters were important factors in 19th-century combat. Along with " marksman" and "expert", "sharpshooter" ...

, a handful of unattached battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions ...

s and 26 unattached companies.

Minutemen of '61

Governor Andrew took office in January 1861, just two weeks after the secession of South Carolina. Convinced that war was imminent, Andrew took rapid measures to prepare the state militia for active duty. On April 15, 1861, Andrew received a telegraph from

Governor Andrew took office in January 1861, just two weeks after the secession of South Carolina. Convinced that war was imminent, Andrew took rapid measures to prepare the state militia for active duty. On April 15, 1861, Andrew received a telegraph from Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

calling for 1,500 men from Massachusetts to serve for ninety days. The next day, several companies of the 8th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia from Marblehead, Massachusetts

Marblehead is a coastal New England town in Essex County, Massachusetts, along the North Shore. Its population was 20,441 at the 2020 census. The town lies on a small peninsula that extends into the northern part of Massachusetts Bay. Attache ...

were the first to report in Boston; by the end of the day, three regiments were ready to start for Washington.

While passing through Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

on April 19, 1861, the 6th Massachusetts was attacked by a pro-secession mob and became the first volunteer troops to suffer casualties in the war. The 6th Massachusetts was also the first volunteer regiment to reach Washington, D.C. in response to Lincoln's call for troops. Lincoln awaited the arrival of additional regiments, but none arrived for several days. Inspecting the 6th Massachusetts on April 24, Lincoln told the soldiers, "I don't believe there is any North...You are the only Northern realities."

Given that the 6th Massachusetts reached Washington on April 19 (the anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, ...

, which commenced the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

) and other Massachusetts regiments were en route to Washington and Virginia on that date, the first militia units to leave Massachusetts were dubbed, "The Minutemen of '61."

Recruiting the three-year regiments

As the initial rush of enthusiasm subsided, the state government faced the ongoing task of recruiting tens of thousands of soldiers to fill federal quotas. The great majority of these troops were required to serve for three years. Recruiting offices were opened in virtually every town and, over the course of 1861, recruits from Massachusetts surpassed the quotas. However, by the summer of 1862, recruiting had slowed considerably. On July 7, 1862, Andrew instituted a system whereby recruitment quotas were issued to every city and town in proportion to their population. This motivated local leaders, increasing enlistment.28th Massachusetts Infantry

The 28th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was well known as the fourth regiment of the famed Irish Brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher. It was the second primarily Irish American volunteer infantry regiment recruited in Massachusetts for service in the American Civil War (the first being the 9th Massachusetts). The regiment's motto (or battle-cry) was ''Faugh a Ballagh'' (Clear the Way!). The men of the 28th Massachusetts saw action in most of the Union Army's major eastern theater engagements, includingAntietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union ...

, and the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

. The regiment was present for Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

's surrender to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

at Appomattox Court House Appomattox Court House could refer to:

* The village of Appomattox Court House, now the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, in central Virginia (U.S.), where Confederate army commander Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union commander Ulyss ...

.

54th Massachusetts Infantry

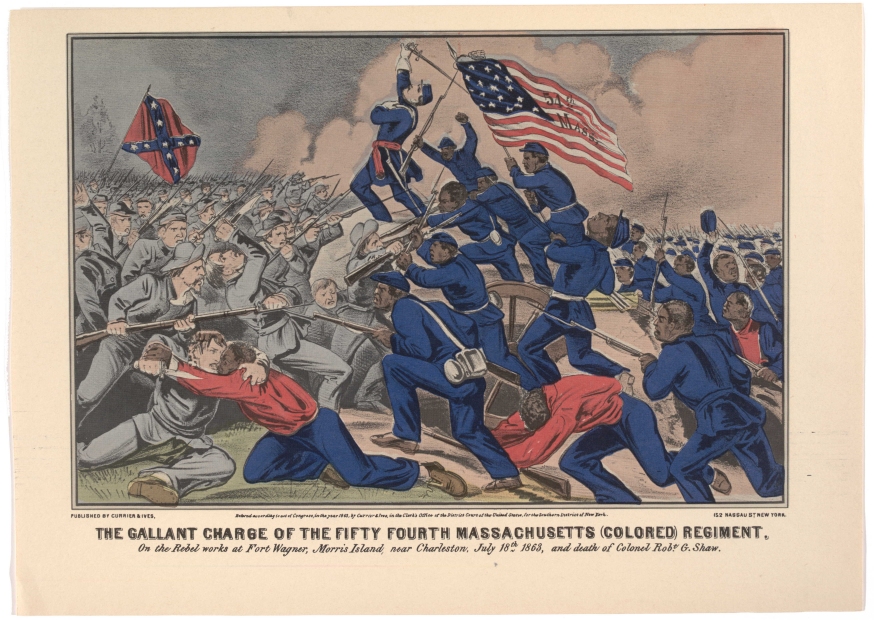

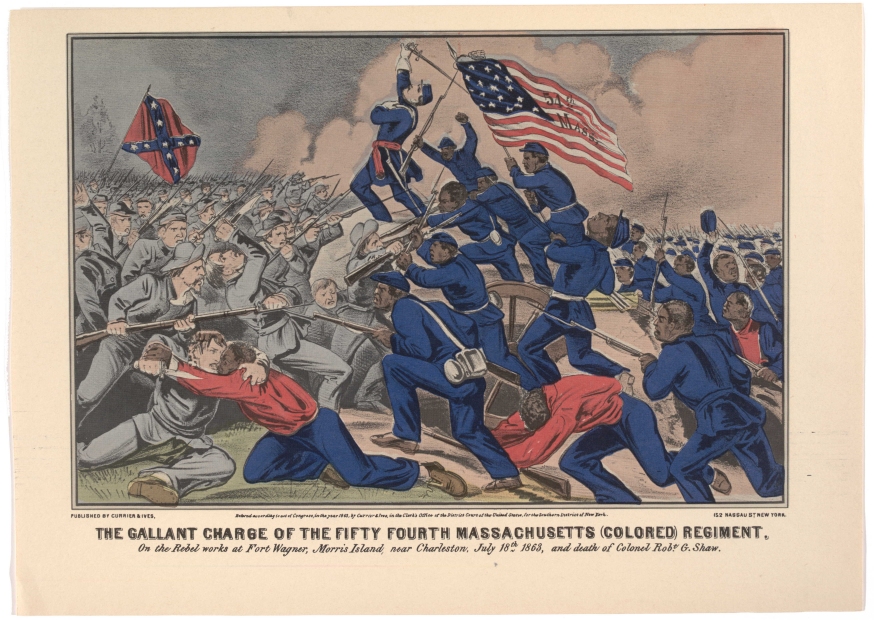

One of the best-known regiments formed in Massachusetts was the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first regiment in the Union army consisting of

One of the best-known regiments formed in Massachusetts was the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first regiment in the Union army consisting of African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

soldiers. It was commanded by white officers. With the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

in effect as of January 1, 1863, Andrew saw the opportunity for Massachusetts to lead the way in recruiting African-American soldiers. After securing permission from President Lincoln, Andrew, black abolitionist Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

and others recruited two regiments of African American soldiers, the 54th and the 55th Massachusetts Infantries.

The 54th, because it was the first such regiment, attracted tremendous publicity during its formation. To ensure the success of the experiment, Andrew solicited donations and political support from many of Boston's elite families. He gained the endorsement of Boston's elite by offering the regiment's command to Robert Gould Shaw, son of prominent Bostonians. The 54th Massachusetts won fame in their assault on Battery Wagner

Fort Wagner or Battery Wagner was a beachhead fortification on Morris Island, South Carolina, that covered the southern approach to Charleston Harbor. It was the site of two American Civil War battles in the campaign known as Operations Agains ...

on Morris Island in Charleston Harbor, during which Col. Shaw was killed. The story of the 54th Massachusetts was the basis for the 1989 film ''Glory''.

General officers

Generals from Massachusetts commanded several army departments, and included a commander of the Army of the Potomac as well as a number of army corps commanders.

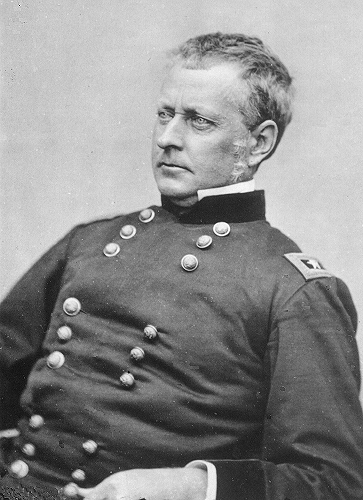

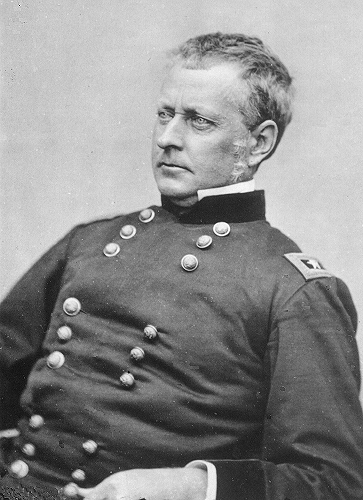

One of the most prominent generals from Massachusetts was Maj. Gen.

Generals from Massachusetts commanded several army departments, and included a commander of the Army of the Potomac as well as a number of army corps commanders.

One of the most prominent generals from Massachusetts was Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

. Born in Hadley, Massachusetts

Hadley (, ) is a town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 5,325 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area. The area around the Hampshire and Mountain Farms Ma ...

and a graduate from the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

at West Point, he served in the Regular Army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a standin ...

during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he was commissioned brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

and steadily rose from brigade commander, to division commander, to commander of the I Corps I Corps, 1st Corps, or First Corps may refer to:

France

* 1st Army Corps (France)

* I Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* I Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Ar ...

, which he led during the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union ...

. Following that battle, he was placed in command of the V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army ...

and then the Center Grand Division of the Army of the Potomac, consisting of the III

III or iii may refer to:

Companies

* Information International, Inc., a computer technology company

* Innovative Interfaces, Inc., a library-software company

* 3i, formerly Investors in Industry, a British investment company

Other uses

* ...

and V Corps. On January 26, 1863, he was promoted to command of the Army of the Potomac. Although he was successful at reviving the ''esprit de corps'' of his army by better distributing supplies and food, he was unable to effectively lead the army in the field, and his inaction during the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

led to his resignation of his command. Transferred to the Department of the Cumberland, he commanded the XI and XII Corps 12th Corps, Twelfth Corps, or XII Corps may refer to:

* 12th Army Corps (France)

* XII Corps (Grande Armée), a corps of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XII (1st Royal Saxon) Corps, a unit of the Imperial German Army

* XII (Ro ...

during several western campaigns and distinguished himself during the Battle of Lookout Mountain

The Battle of Lookout Mountain also known as the Battle Above The Clouds was fought November 24, 1863, as part of the Chattanooga Campaign of the American Civil War. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker assaulted Lookout Mountain, Cha ...

. Hooker resigned his command upon the promotion of Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men against ...

to the command of the Army of the Tennessee

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, a post to which Hooker felt entitled. Hooker served the remainder of the war in an administrative role, overseeing the Department of the North (consisting of army fortifications and troops stationed in Michigan, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois) and the Department of the East

The Department of the East was a military administrative district established by the U.S. Army several times in its history. The first was from 1853 to 1861, the second Department of the East, from 1863 to 1873, and the last from 1877 to 1913.

H ...

(which encompassed installations and troops in New England, New York and New Jersey).

Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

, former governor of Massachusetts, was among the first men appointed major general of volunteers by President Lincoln. In July 1861, Banks came to command the Department of the Shenandoah. In May 1862, he was completely out-generaled by Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

and forced to abandon the Shenandoah Valley. He then commanded the II Corps during the Northern Virginia Campaign and was eventually transferred to command of the Department of the Gulf

The Department of the Gulf was a command of the United States Army in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and of the Confederate States Army during the Civil War.

History United States Army (Civil War)

Creation

The department was con ...

, coordinating military efforts in Louisiana and Texas. In this capacity, Banks led the successful and strategically important Siege of Port Hudson

The siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana, (May 22 – July 9, 1863) was the final engagement in the Union campaign to recapture the Mississippi River in the American Civil War.

While Union General Ulysses Grant was besieging Vicksburg upriver, Ge ...

in the summer of 1863, but also the disastrous Red River Campaign in the spring of 1864, which he commanded under protest. The campaign ended his military career in the field.

Another significant general from Massachusetts, Maj. Gen. Edwin Vose Sumner, born in 1797, was the oldest general officer with a field command on either side of the war. He had served in the Regular Army during the Mexican-American

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

war and numerous campaigns in the West. Sumner commanded the II Corps during the Maryland Campaign and later the Right Grand Division of the Army of the Potomac during the Fredericksburg Campaign

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burns ...

. Following the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Bur ...

, he resigned his command in January 1863 and was to be transferred to command the Department of the Missouri, but died of a heart attack en route on March 21, 1863.

Other important generals from Massachusetts included Maj. Gen. Darius Couch

Darius Nash Couch (July 23, 1822 – February 12, 1897) was an American soldier, businessman, and naturalist. He served as a career U.S. Army officer during the Mexican–American War, the Second Seminole War, and as a general officer in the Uni ...

, who commanded the II Corps and the Department of the Susquehanna The Department of the Susquehanna was a military department created by the United States War Department during the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War. Its goal was to protect the state capital and the southern portions of the commonwea ...

, Maj. Gen. John G. Barnard, who organized the defenses of Washington, DC and became Chief Engineer of the Union Armies in the field, and Maj. Gen. Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represen ...

, who had graduated first in his class at West Point and commanded a division of the IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German ...

.

War materiel

The advanced state of industrialization in the North, as compared with the Confederate states, was a major factor in the victory of Union armies. Massachusetts, and the

The advanced state of industrialization in the North, as compared with the Confederate states, was a major factor in the victory of Union armies. Massachusetts, and the Springfield Armory

The Springfield Armory, more formally known as the United States Armory and Arsenal at Springfield located in the city of Springfield, Massachusetts, was the primary center for the manufacture of United States military firearms from 1777 until ...

in particular, played a pivotal role as a supplier of weapons and equipment for the Union army.

At the start of the war, the Springfield Armory was one of only two federal armories in the country, the other being the Harpers Ferry Armory. After the attack on Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battle ...

and the commencement of hostilities, Governor Andrew wrote Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Simon Cameron, urging him to discontinue the Harpers Ferry Armory (which was at that time on Confederate soil) and to channel all available federal funds towards enhancing production at the Springfield Armory. The armory produced the primary weapon of the Union infantry during the war—the Springfield rifled musket. By the end of the war, nearly 1.5 million had been produced by the armory and its numerous contractors across the country.

Another key source of war materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

was the Watertown Arsenal

The Watertown Arsenal was a major American arsenal located on the northern shore of the Charles River in Watertown, Massachusetts. The site is now registered on the ASCE's List of Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks and on the US Nationa ...

, which produced ammunition, gun carriages and leather military accouterments. Private companies such as Smith & Wesson

Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc. (S&W) is an American firearm manufacturer headquartered in Springfield, Massachusetts, United States.

Smith & Wesson was founded by Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson as the "Smith & Wesson Revolver Company" in 1856 ...

enjoyed significant U.S. government contracts. The Ames Manufacturing Company

Ames Manufacturing Company was a manufacturer of swords, tools and cutlery in Chicopee, Massachusetts, as well as an iron and bronze foundry. They were a major provider of side arms, swords, light artillery, and heavy ordnance for the Union in the ...

of Chicopee became one of the nation's leading suppliers of swords, side arms, and cannons, and the third largest supplier of heavy ordnance.

Although Massachusetts was a major center of shipbuilding prior to the war, many of the established shipbuilding firms were slow to adapt to new technology. The few Massachusetts shipbuilders who received government contracts for the construction of iron-clad, steam powered warships were those who had invested in iron and machine technology before the war. These included the City Point Works, managed by Harrison Loring, and the Atlantic Iron Works, managed by Nelson Curtis, two Boston companies that produced Passaic class monitors during the war. The Boston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

also produced several smaller gunboats.

Relief organizations

Several instrumental leaders of soldiers' aid and relief organizations came from Massachusetts. These included

Several instrumental leaders of soldiers' aid and relief organizations came from Massachusetts. These included Dorothea Dix

Dorothea Lynde Dix (April 4, 1802July 17, 1887) was an American advocate on behalf of the indigent mentally ill who, through a vigorous and sustained program of lobbying state legislatures and the United States Congress, created the first gen ...

, who had traveled across the nation working to promote proper care for the poor and insane before the war. After the outbreak of the war, she convinced the U.S. Army to establish a Women's Nursing Bureau on April 23, 1861 and became the first woman to head a federal government bureau. Although army officials were dubious about the use of female nurses, Dix proceeded to recruit many women who had previously been serving as unorganized volunteers. One of her greatest challenges, given the biases of the era, was to demonstrate that women could serve as competently as men in army hospitals. Dix had a reputation for rejecting nurses who were too young or attractive, believing that patients and surgeons alike would not take them seriously. U.S. Army surgeons often resented the nurses of Dix's bureau, claiming that they were obstinate and did not follow military protocol. Despite such obstacles, Dix was successful at placing female nurses in hospitals throughout the North.

Henry Whitney Bellows determined to take a different approach, establishing a civilian organization of nurses separate from the U.S. Army. Bellows was the founder of the United States Sanitary Commission

The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was a private relief agency created by federal legislation on June 18, 1861, to support sick and wounded soldiers of the United States Army (Federal / Northern / Union Army) during the American Civil ...

and served as its only president. An influential minister, born and raised in Boston, Bellows went to Washington in May 1861 as head of a delegation of physicians representing the Women's Central Relief Association of New York and other organizations. Bellows's aim was to convince the government to establish a civilian auxiliary branch of the Army Medical Bureau. The Sanitary Commission, established by President Lincoln on June 13, 1861, provided nurses (mostly female) with medical supplies and organized hospital ships and soldiers' homes.

Clara Barton

Clarissa Harlowe Barton (December 25, 1821 – April 12, 1912) was an American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse in the American Civil War, a teacher, and a patent clerk. Since nursing education was not then very ...

, a former teacher from Oxford, Massachusetts and clerk in the U.S. Patent Office

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Commerce that serves as the national patent office and trademark registration authority for the United States. The USPTO's headquarters are in Alexa ...

, created a one-woman relief effort. In the summer of 1861, in response to a shortage of food and medicine in the growing Union army, she began personally purchasing and distributing supplies to wounded soldiers in Washington. Growing dissatisfied with bringing supplies to hospitals, Barton eventually moved her efforts to the battlefield itself. She was granted access through army lines and helped the wounded in numerous campaigns, soon becoming known as the "Angel of the Battlefield." She achieved national prominence, and high-ranking army surgeons requested her assistance in managing their field hospitals.

Aftermath and Reconstruction era

In all, 12,976 servicemen from Massachusetts died during the war, about eight percent of those who enlisted and about one percent of the state's population (the population of Massachusetts in 1860 was 1,231,066). Official statistics are not available for the number of wounded. Across the nation, organizations such as the

In all, 12,976 servicemen from Massachusetts died during the war, about eight percent of those who enlisted and about one percent of the state's population (the population of Massachusetts in 1860 was 1,231,066). Official statistics are not available for the number of wounded. Across the nation, organizations such as the Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy ( U.S. Navy), and the Marines who served in the American Civil War. It was founded in 1866 in Decatur, ...

(GAR) were established to provide aid to veterans, widows and orphans. Massachusetts was the first state to organize a statewide Woman's Relief Corps, a female auxiliary organization of the GAR, in 1879.

With the war over and his primary goal completed, Governor Andrew declared in September 1865 that he would not seek re-election. Despite this loss, the Republican Party in Massachusetts would become stronger than ever in the post-war years. The Democratic party would be all but non-existent in the Bay State for roughly ten years due to their earlier anti-war platform. The group most affected by this political shift was the growing Boston Irish community, who had backed the Democratic Party and were without significant political voice for decades.

After the war, senators Sumner and Wilson would transform their pre-war antislavery views into vehement support for so-called "Radical Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

" of the South. Their agenda called for civil rights for African Americans and harsh treatment of former Confederates.

For a time, the Radical Republicans made progress on their agenda of dramatic reform measures. According to historian Eric Foner

Eric Foner (; born February 7, 1943) is an American historian. He writes extensively on American political history, the history of freedom, the early history of the Republican Party, African-American biography, the American Civil War, Reconstruc ...

, Massachusetts state legislators passed the first comprehensive integration law in the nation's history in 1865. On the national level, Sumner joined with Representative Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

and others to achieve Congressional approval of the Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Ame ...

, and the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, outlawing slavery and granting increased citizenship rights to former slaves.

As early as 1867, however, a national backlash against Radical Republicans and their sweeping civil rights programs made them increasingly unpopular, even in Massachusetts. When Sumner attempted in 1867 to propose dramatic reforms, including integrated schools in the South and re-distribution of land to former slaves, even Wilson refused to support him. By the 1870s, Radical Republicans had diminished in power and Reconstruction proceeded along more moderate lines.

Culturally speaking, post-Civil War Massachusetts ceased to be a national center of idealistic reform movements (such as evangelicalism

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

, temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

and antislavery) as it had been before the war. Growing industrialism, partly spurred on by the war, created a new culture of competition and materialism.

In 1869, Boston was the site of the National Peace Jubilee, a massive gala to honor veterans and to celebrate the return of peace. Conceived by composer Patrick Gilmore, who had served in an army band, the celebration was held in a colossal arena in Boston's Back Bay

Back Bay is an officially recognized neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, built on reclaimed land in the Charles River basin. Construction began in 1859, as the demand for luxury housing exceeded the availability in the city at the time, and t ...

neighborhood designed to hold 100,000 attendees and specifically built for the occasion. A new hymn was commissioned for the occasion, written by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. and set to ''American Hymn'' by Matthais Keller. Spanning five days, the event featured a chorus of nearly 11,000 and an orchestra of more than 500 musicians. It was the largest musical gathering on the continent up to that time.

See also

*List of Massachusetts Civil War units

Units raised in Massachusetts during the American Civil War consisted of 62 regiments of infantry, six regiments of cavalry, 16 batteries of light artillery, four regiments of heavy artillery, two companies of sharpshooters, a handful of unattac ...

* List of Massachusetts generals in the American Civil War

There were approximately 120 general officers from Massachusetts who served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. This list consists of generals who were either born in Massachusetts or lived in Massachusetts when they joined the army ( ...

* Dedham, Massachusetts in the American Civil War

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Frank, Stephen M. " 'Rendering Aid and Comfort': Images of Fatherhood in the Letters of Civil War Soldiers from Massachusetts and Michigan." ''Journal of Social History'' (1992): 5-31online

* Rorabaugh, William J. "Who Fought for the North in the Civil War? Concord, Massachusetts, Enlistments," ''Journal of American History'' 73 (December 1986): 695–70

online

* Ware, Edith E. ''Political Opinion in Massachusetts during the Civil War and Reconstruction'', (1916)

full text online

External links

Massachusetts Civil War Monuments Project

John A. Andrew Papers

at the

Massachusetts Historical Society

The Massachusetts Historical Society is a major historical archive specializing in early American, Massachusetts, and New England history. The Massachusetts Historical Society was established in 1791 and is located at 1154 Boylston Street in Bosto ...

Civil War correspondence, diaries, and journals

at the Massachusetts Historical Society

Massachusetts National Guard Museum and Archives

{{Authority control

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

1860s in Massachusetts

American Civil War by state