Martin Heidegger and Nazism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philosopher

Philosopher

"The Self-Assertion of the German University"

Rectoral address at the University of Freiburg, 1933

original German

). English version translated by Karston Harries, ''Review of Metaphysics'' 38 (March 1985): pp. 467–502. See also G. Neske and E. Kettering (eds), ''Martin Heidegger and National Socialism'', New York: Paragon House, 1990, pp. 5–13; see also R. Wolin, ed., ''The Heidegger Controversy'' (MIT Press, 1993). This speech has become notorious as a visible endorsement of Nazism by Heidegger, giving the blessing of his philosophy to the new political party. However, philosopher Jacques Taminiaux writes that "it is to admit that the rectorate speech do snot tally at all with the Nazi ideology", and Eduard Langwald calls it even a "challenge to Hitlerism" or an "anti-Mein-Kampf-address", for Heidegger refers to Plato instead of Hitler (who is not mentioned) and, above all, puts limits on the Nazi leader-principle (''Führerprinzip''):

According to Farias and Ott, Heidegger also denounced or demoted three colleagues for being insufficiently committed to the Nazi cause. But this has been disputed by Eduard Langwald, who considers "Heidegger was never a Nazi-minded informer".

According to Hugo Ott, Heidegger leaked information on September 29, 1933 to the local minister of education that the chemist Hermann Staudinger had been a pacifist during World War I. Staudinger was a professor of chemistry at Freiburg, and had developed the theory that

According to Farias and Ott, Heidegger also denounced or demoted three colleagues for being insufficiently committed to the Nazi cause. But this has been disputed by Eduard Langwald, who considers "Heidegger was never a Nazi-minded informer".

According to Hugo Ott, Heidegger leaked information on September 29, 1933 to the local minister of education that the chemist Hermann Staudinger had been a pacifist during World War I. Staudinger was a professor of chemistry at Freiburg, and had developed the theory that

Beginning in 1917, the philosopher

Beginning in 1917, the philosopher

According to Emmanuel Faye, Heidegger supported the "necessity of a

According to Emmanuel Faye, Heidegger supported the "necessity of a  In another speech a few days later, Heidegger endorsed the German election of November 1933, in which the electorate was presented with a single Nazi-approved list of candidates:

In another speech a few days later, Heidegger endorsed the German election of November 1933, in which the electorate was presented with a single Nazi-approved list of candidates:

Only a God Can Save Us

by William J. Richardson in

For critical readings of the interview, see In particular the contributions by Jürgen Habermas (), Blanchot (), Derrida (), and Lacoue-Labarthe (). At his own insistence, Heidegger edited the published version of the interview extensively. In the interview, Heidegger defends his involvement with the Nazi party on two points: first, that he was trying to save the university from being completely taken over by the Nazis, and therefore he tried to work with them. Second, he saw in the historic moment the possibility for an "awakening" (''Aufbruch'') which might help to find a "new national and social approach" to the problem of Germany's future, a kind of middle ground between capitalism and communism. For example, when Heidegger talked about a "national and social approach" to political problems, he linked this to

In his 1985 book '' The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity'', Jürgen Habermas wrote that Heidegger's lack of explicit criticism against Nazism is due to his unempowering turn (''

In his 1985 book '' The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity'', Jürgen Habermas wrote that Heidegger's lack of explicit criticism against Nazism is due to his unempowering turn (''

academia.edu, 2018

François Rastier

Heidegger, théoricien et acteur de l’extermination des juifs?, The Conversation, 1. November 2017

/ref>

"Heidegger and the Nazis"

(), a review of Victor Farias' ''Heidegger et le nazisme''. Original article: On the other hand, Jaspers testified in his report of December 1945: "In the twenties, Heidegger was no anti-Semite. With respect to this question he did not always exercise discretion. This doesn't rule out the possibility that, as I must assume, in other cases anti-Semitism went against his conscience and his taste." There were "rumors" that Heidegger was anti-Semitic by 1932, and he was aware of them, and vehemently denied them, calling them "slander" in a letter to Hannah Arendt. In response to her concern about these rumors that he was ''becoming'' anti-Semitic, Heidegger wrote ironically:

"Heidegger, l'enfer des philosophes"

''Le Nouvel Observateur'', Paris, 6–12 novembre 1987. * Victor Farias, ''Heidegger and Nazism'', Temple University Press (1989) . * Emmanuel Faye, ''Heidegger, l'introduction du nazisme dans la philosophie'', Albin Michel, 2005. * François Fédier, ''Heidegger. Anatomie d'un scandale'', Robert Laffont, Paris, 1988. . * François Fédier (ed.), Martin Heidegger, ''Écrits politiques 1933–1966'', Gallimard, Paris, 1995. . * François Fédier (ed.), ''Heidegger, à plus forte raison'', Paris: Fayard, 2007. * Luc Ferry & Alain Renaut (1988). ''Heidegger et les Modernes'', Gallimard, 1988. * Luc Ferry & Alain Renaut, Système et critique, Ousia, Bruxelles, 1992. *

Political Texts – Rectoral Addresses

*Karl Löwith

*Arne D. Naess Jr.

Heidegger and Nazism

on ''

Der Spiegel Interview by Rudolf Augstein and Georg Wolff, 23 September 1966; published May 31 1976Heidegger and Nazism: An ExchangeA Normal Nazi Thomas Sheehan On Heidegger

In French

Réponses de Gérard Guest (1) (au dossier publié dans "Magazine Littéraire")Réponses de Gérard Guest (2) ( au dossier publié dans "Le Point")Television debate François Fédier, Pascal David and E.Faye. Multimedia

{{Authority control German philosophy Martin Heidegger Heidegger, Martin 20th-century philosophy

Philosopher

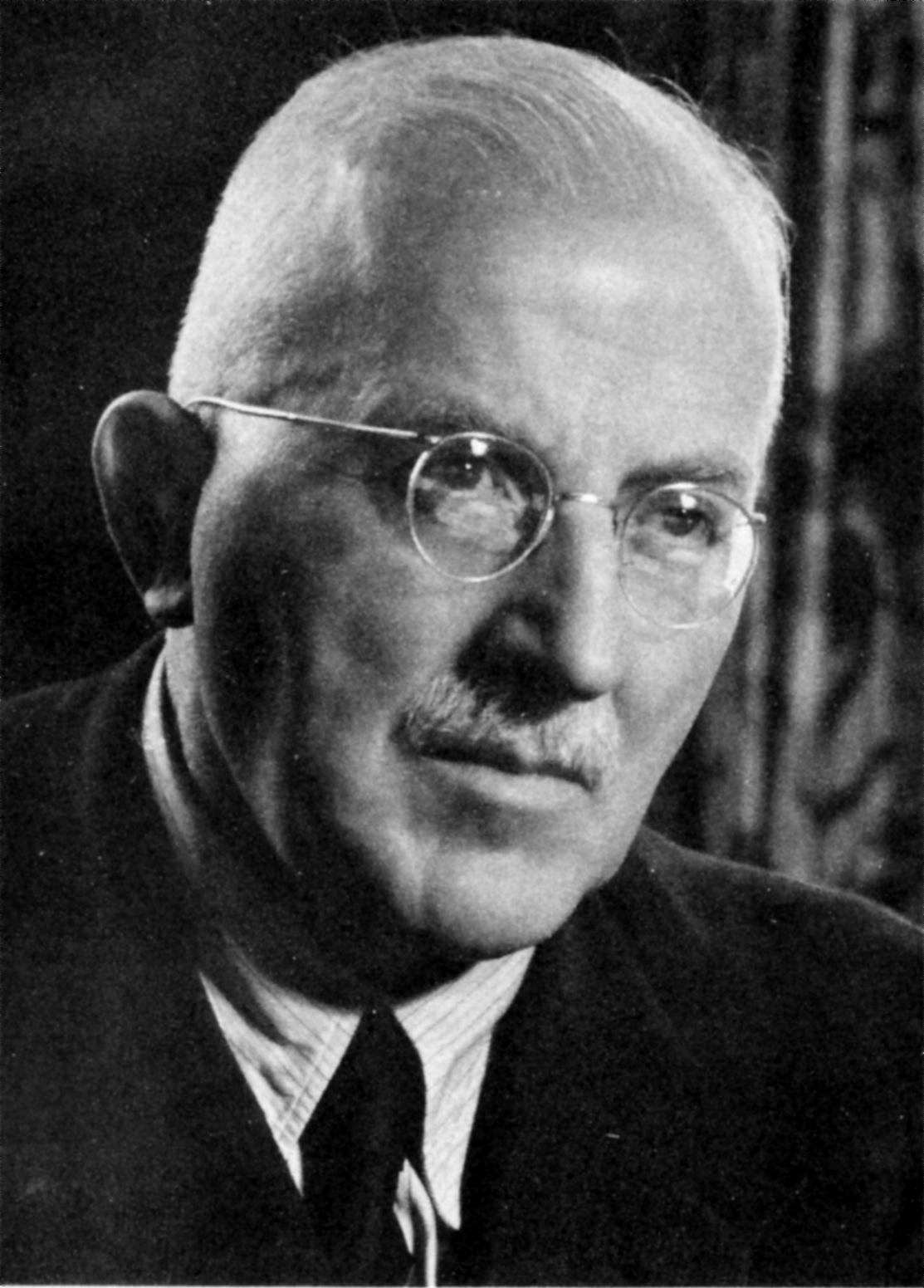

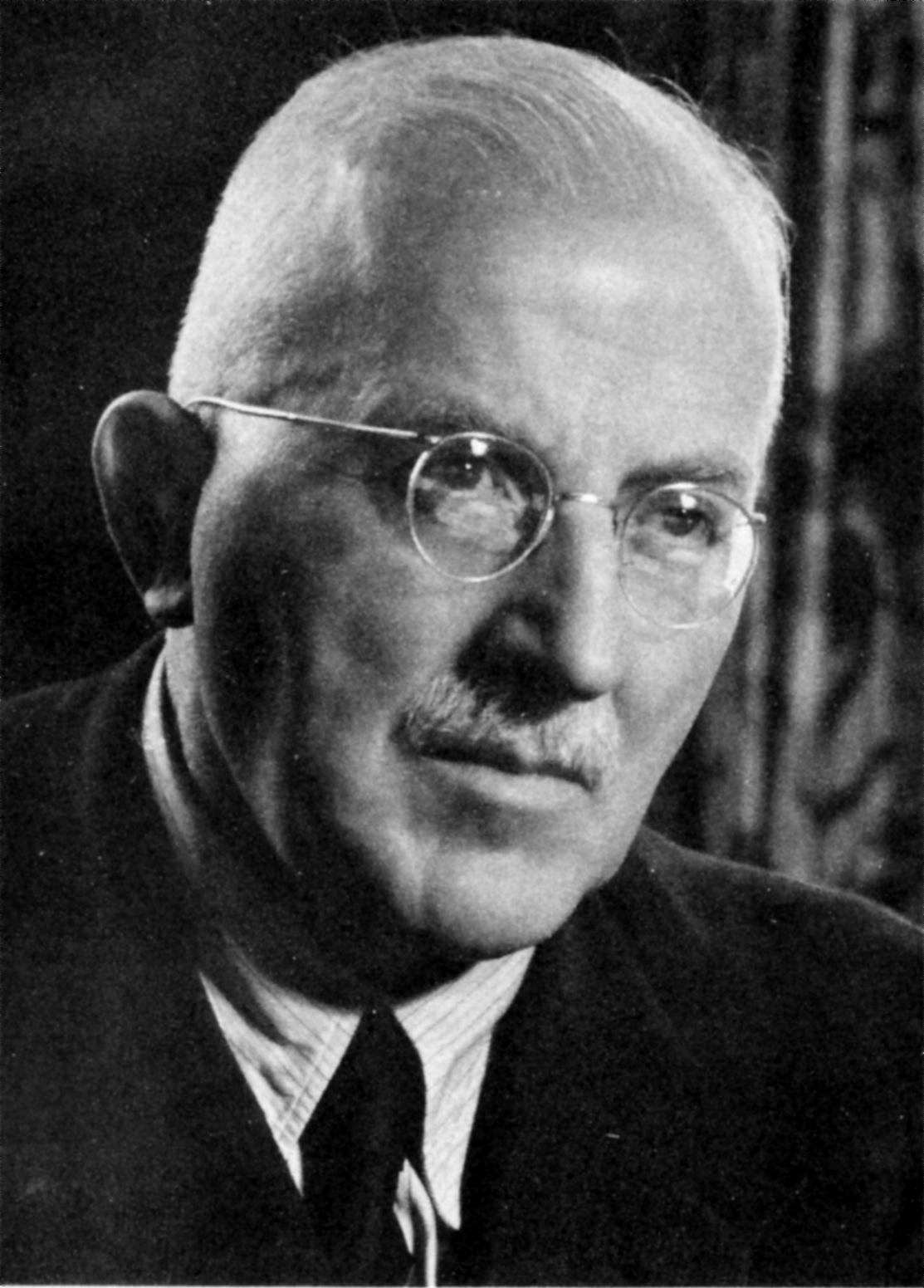

Philosopher Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; ; 26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th ce ...

joined the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

(NSDAP) on May 1, 1933, ten days after being elected Rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially german: Uni Freiburg), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (german: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg), is a public research university located in Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemb ...

. A year later, in April 1934, he resigned the Rectorship and stopped taking part in Nazi Party meetings, but remained a member of the Nazi Party until its dismantling at the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. The denazification hearings immediately after World War II led to Heidegger's dismissal from Freiburg, banning him from teaching. In 1949, after several years of investigation, the French military finally classified Heidegger as a ''Mitläufer

A (plural , German for " fellow traveller") is a person (the German term has the male grammatical gender; to specifically indicate a female the -in suffix has to be added) believed to be tied to or passively sympathising of certain social movemen ...

'' or "fellow traveller

The term ''fellow traveller'' (also ''fellow traveler'') identifies a person who is intellectually sympathetic to the ideology of a political organization, and who co-operates in the organization's politics, without being a formal member of that o ...

." The teaching ban was lifted in 1951, and Heidegger was granted '' emeritus'' status in 1953, but he was never allowed to resume his philosophy chairmanship.

Heidegger's involvement with Nazism, his attitude towards Jews and his near-total silence about the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

in his writing and teaching after 1945 are highly controversial. The '' Black Notebooks'', written between 1931 and 1941, contain several anti-semitic statements, although they also contain several statements where Heidegger appears extremely critical of racial antisemitism

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews based on a belief or assertion that Jews constitute a distinct race that has inherent traits or characteristics that appear in some way abhorrent or inherently inferior or otherwise different from ...

. After 1945, Heidegger never published anything about the Holocaust or the extermination camps, and made one sole verbal mention of them, in 1949, whose meaning is disputed among scholars. Heidegger never apologized for anything and is only known to have expressed regret once, privately, when he described his rectorship and the related political engagement as "the greatest stupidity of his life" (''"die größte Dummheit seines Lebens"'').

Whether there is a relation between Heidegger's political affiliation and his philosophy is another matter of controversy. Critics, such as Günther Anders

Günther Anders (born Günther Siegmund Stern, 12 July 1902 – 17 December 1992) was a German-Austrian Jewish émigré, philosopher, essayist and journalist.

Trained in the phenomenological tradition, he developed a philosophical anthropolo ...

, Jürgen Habermas, Theodor Adorno

Theodor is a masculine given name. It is a German form of Theodore. It is also a variant of Teodor.

List of people with the given name Theodor

* Theodor Adorno, (1903–1969), German philosopher

* Theodor Aman, Romanian painter

* Theodor Blue ...

, Hans Jonas, Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Maurice Jean Jacques Merleau-Ponty. (; 14 March 1908 – 3 May 1961) was a French phenomenological philosopher, strongly influenced by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. The constitution of meaning in human experience was his main interest an ...

, Karl Löwith,Karl Löwith, ''Mein Leben in Deutschland vor und nach 1933: ein Bericht'' (Stuttgart: Metzler, 1986), p. 57, translated by Paula Wissing as cited by Maurice Blanchot in "Thinking the Apocalypse: a Letter from Maurice Blanchot to Catherine David", in ''Critical Inquiry'' 15:2, pp. 476–477. Pierre Bourdieu

Pierre Bourdieu (; 1 August 1930 – 23 January 2002) was a French sociologist and public intellectual. Bourdieu's contributions to the sociology of education, the theory of sociology, and sociology of aesthetics have achieved wide influence ...

, Maurice Blanchot

Maurice Blanchot (; ; 22 September 1907 – 20 February 2003) was a French writer, philosopher and literary theorist. His work, exploring a philosophy of death alongside poetic theories of meaning and sense, bore significant influence on pos ...

, Emmanuel Levinas

Emmanuel Levinas (; ; 12 January 1906 – 25 December 1995) was a French philosopher of Lithuanian Jewish ancestry who is known for his work within Jewish philosophy, existentialism, and phenomenology, focusing on the relationship of ethics t ...

, Luc Ferry, Jacques Ellul

Jacques Ellul (; ; January 6, 1912 – May 19, 1994) was a French philosopher, sociologist, lay theologian, and professor who was a noted Christian anarchist. Ellul was a longtime Professor of History and the Sociology of Institutions on ...

, and Alain Renaut assert that Heidegger's affiliation with the Nazi Party revealed flaws inherent in his philosophical conceptions. His supporters, such as Hannah Arendt, Otto Pöggeler, Jan Patočka

Jan Patočka (; 1 June 1907 – 13 March 1977) was a Czech philosopher. Having studied in Prague, Paris, Berlin, and Freiburg, he was one of the last pupils of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. In Freiburg he also developed a lifelong philos ...

, Silvio Vietta

Silvio Vietta (born 7 August 1941, in Berlin) is a German scholar and professor emeritus of the University of Hildesheim. His work has concerned itself principally with German literature, philosophy and European cultural history. His main areas of ...

, Jacques Derrida, Jean Beaufret

Jean Beaufret (; 22 May 1907, in Auzances7 August 1982, in Paris) was a French philosopher and Germanist tremendously influential in the reception of Martin Heidegger's work in France.

Life

After graduating from the École Normale Supérieure ...

, Jean-Michel Palmier, Richard Rorty

Richard McKay Rorty (October 4, 1931 – June 8, 2007) was an American philosopher. Educated at the University of Chicago and Yale University, he had strong interests and training in both the history of philosophy and in contemporary analytic ...

, Marcel Conche, Julian Young, Catherine Malabou, and François Fédier, see his involvement with Nazism as a personal "error"a word which Arendt placed in quotation marks when referring to Heidegger's Nazi-era politics that is irrelevant to his philosophy.

Timeline

Heidegger's rectorate at the University of Freiburg

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. Heidegger was elected rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially german: Uni Freiburg), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (german: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg), is a public research university located in Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemb ...

on April 21, 1933, on the recommendation of his predecessor von Möllendorff, who was forced to give up his position because he had refused to display an anti-Jewish poster, and assumed the position the following day. He joined the "National Socialist German Workers' Party" ten days later, on May 1 (significantly the international day of workers' solidarity: Heidegger said after the war he supported the social more than the national). He co-signed a public telegram sent by Nazi rectors to Hitler on May 20, 1933. Otto Pöggeler puts this attitude into perspective:

He wasn't alone to be mystified. Toynbee too after an audience in 1936 noted about Hitler: "he has beautiful hands". (...) ''Mein Kampf'' had hardly been read and absolutely not taken seriously. (...) Roosevelt was impressed by Hitler's manners, the ''Times'' in London supported Hitler's demands, and as a result of high stock exchange prices, people applauded in London's cinemas when the newsreel showed Hitler's image.In Germany, the atmosphere of those days has been described by

Sebastian Haffner

Raimund Pretzel (27 December 1907 – 2 January 1999), better known by his pseudonym Sebastian Haffner, was a German journalist and historian. As an émigré in Britain during World War II, Haffner argued that accommodation was impossible not on ...

, who experienced it himself, as "a widespread feeling of deliverance, of liberation from democracy." Rüdiger Safranski

Rüdiger Safranski (born 1 January 1945) is a German philosopher and author.

Life

From 1965 to 1972, Safranski studied philosophy (among others with Theodor W. Adorno), German literature, history and history of art at Goethe University i ...

explains:

This sense of relief at the demise of democracy was shared not only by the enemies of the republic. Most of its supporters, too, no longer credited it with the strength to master the crisis. It was as if a paralyzing weight had been lifted. Something genuinely new seemed to be beginning — a people's rule without political parties, with a leader of whom it was hoped that he would unite Germany once more internally and make her self-assured externally. (...) Hitler's "Peace Speech" of May 17, 1933, when he declared that "boundless love and loyalty to one's own nation" included "respect" for the national rights of other nations, had its effect. The London ''Times'' observed that Hitler had "indeed spoken for a united Germany." Even among the Jewish population — despite the boycott of Jewish businesses on April 1 and the dismissal of Jewish public employees after April 7 — there was a good deal of enthusiastic support for the "National revolution". Georg Picht recalls thatJaspers noted about his last meeting with him in May 1933: "It's just like 1914, again this deceptive mass intoxication." The new rector Heidegger was sober enough to refuse, like his predecessor, to display the anti-Jewish poster. He argued after the war that he joined the Party to avoid dismissal, and he forbade the planned book-burning that was scheduled to take place in front of the main University building. Nevertheless, according to Victor Farias, Hugo Ott, and Emmanuel Faye, Heidegger implemented the '' Gleichschaltung'' totalitarian policy, suppressing all opposition to the government. Faye p. 40–46details precisely Heidegger's actions in implementing anti-Semitic legislation within Freiburg University. Along with Ernst Krieck and Alfred Baeumler, Heidegger spearheaded theEugen Rosenstock-Huessy Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy (July 6, 1888 – February 24, 1973) was a historian and social philosopher, whose work spanned the disciplines of history, theology, sociology, linguistics and beyond. Born in Berlin, Germany into a non-observant Jewish ..., in a lecture in March 1933, declared that the National Socialist revolution was an attempt by the Germans to realize Hölderlin's dream. (...) Heidegger was indeed captivated by Hitler in this first year.

Conservative Revolution

The Conservative Revolution (german: Konservative Revolution), also known as the German neoconservative movement or new nationalism, was a German national-conservative movement prominent during the Weimar Republic, in the years 1918–1933 (betw ...

promoted (in the beginning) by the Nazis. But according to others such as François Fédier and Julian Young, Heidegger "called for, not the subordination of the university to the state, but precisely the reverse", and "did indeed seek to protect students from indoctrination by the crasser form of Nazi propaganda". Young quotes the testimony of a former student, Georg Picht

Georg may refer to:

* ''Georg'' (film), 1997

*Georg (musical), Estonian musical

* Georg (given name)

* Georg (surname) George is a surname of Irish, English, Welsh, South Indian Christian, Middle Eastern Christian (usually Lebanese), French, or ...

:

The way Heidegger conceived of the revival of the university, this became clear to me on the occasion of a memorable event. To give the first lecture within the framework of "political education" a compulsory measure introduced at the universities by the Nazis (...) – Heidegger, rector at that time, invited my mother's brother in law, Viktor von Weizsäcker. Everyone was puzzled, because it was well-known that Weizsäcker was no Nazi. But Heidegger's word was law. The student he had chosen to lead the philosophy department thought he should pronounce introductory words on national socialist revolution. Heidegger soon manifested signs of impatience, then he shouted with a loud voice that irritation strained: "this jabber will stop immediately!" Totally prostrated, the student disappeared from the tribune. He had to resign from office. As for Victor von Weizsäcker, he gave a perfect lecture on his philosophy of medicine, in which national socialism was not once mentioned, but far ratherPicht recalls his uncle Weizsäcker told him afterwards about Heidegger's political engagement:Sigmund Freud Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts ....

I'm pretty sure it's a misunderstandingsuch a thing happens often in history of philosophy. But Heidegger is a step ahead: he perceives something is going on that the others don't.Heidegger's tenure as rector was fraught with difficulties. He was in conflict with Nazi students, intellectuals, and bureaucrats. Philosophical historian

Hans Sluga

Hans D. Sluga (; born April 24, 1937) is a German philosopher who spent most of his career as professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. Sluga teaches and writes on topics in the history of analytic philosophy, the history ...

wrote:

Though as rector he prevented students from displaying an anti-Semitic poster at the entrance to the university and from holding a book burning, he kept in close contact with the Nazi student leaders and clearly signaled to them his sympathy with their activism.Some Nazi education officials viewed also him as a rival, while others saw his efforts as comical. His most risible initiative was the creation of a ''Wissenschaftslager'' or Scholar's camp, seriously described by Rockmore as a "reeducation camp", but by Safranski as rather a "mixture of scout camp and Platonic academy", actually "to build campfires, share food, have conversation, sing along with guitar... with people who were really a little beyond Cub Scout age". Safranski tells how a dispute occurred with a group of SA students and their military spirit. Some of Heidegger's fellow Nazis also ridiculed his philosophical writings as gibberish. He finally offered his resignation on April 23, 1934, and it was accepted on April 27. Heidegger remained a member of both the academic faculty and of the Nazi Party until the end of the war, but took no part in Party meetings. In 1944, he didn't even have the right to teach anymore, was considered a "completely dispensable" teacher, and was ordered up the Rhine to build fortifications, then drafted into the ''

Volkssturm

The (; "people's storm") was a levée en masse national militia established by Nazi Germany during the last months of World War II. It was not set up by the German Army, the ground component of the combined German ''Wehrmacht'' armed forces, ...

'' national militia, "the oldest member of the faculty to be called up". In 1945 Heidegger wrote of his term as rector, giving the writing to his son Hermann; it was published in 1983:

The rectorate was an attempt to see something in the movement that had come to power, beyond all its failings and crudeness, that was much more far-reaching and that could perhaps one day bring a concentration on the Germans' Western historical essence. It will in no way be denied that at the time I believed in such possibilities and for that reason renounced the actual vocation of thinking in favor of being effective in an official capacity. In no way will what was caused by my own inadequacy in office be played down. But these points of view do not capture what is essential and what moved me to accept the rectorate.

Inaugural address

Heidegger's inaugural address as rector of Freiburg, the "Rektoratsrede", was entitled "The Self-Assertion of the German University" ("Die Selbstbehauptung der deutschen Universität").M. Heidegger"The Self-Assertion of the German University"

Rectoral address at the University of Freiburg, 1933

original German

). English version translated by Karston Harries, ''Review of Metaphysics'' 38 (March 1985): pp. 467–502. See also G. Neske and E. Kettering (eds), ''Martin Heidegger and National Socialism'', New York: Paragon House, 1990, pp. 5–13; see also R. Wolin, ed., ''The Heidegger Controversy'' (MIT Press, 1993). This speech has become notorious as a visible endorsement of Nazism by Heidegger, giving the blessing of his philosophy to the new political party. However, philosopher Jacques Taminiaux writes that "it is to admit that the rectorate speech do snot tally at all with the Nazi ideology", and Eduard Langwald calls it even a "challenge to Hitlerism" or an "anti-Mein-Kampf-address", for Heidegger refers to Plato instead of Hitler (who is not mentioned) and, above all, puts limits on the Nazi leader-principle (''Führerprinzip''):

All leading must concede its following its own strength. All following, however, bears resistance in itself. This essential opposition of leading and following must not be blurred let alone eliminated.In this speech, Heidegger declared that "science must become the power that shapes the body of the German university." But by "science" he meant "the primordial and full essence of science", which he defined as "engaged knowledge about the people and about the destiny of the state that keeps itself in readiness ..at one with the spiritual mission." He went on to link this concept of "science" with a historical struggle of the German people:

The will to the essence of the German university is the will to science as will to the historical spiritual mission of the German people as a people Volk"that knows itself in its state Staat" Together, science and German destiny must come to power in the will to essence. And they will do so and only will do so, if weteachers and studentson the one hand, expose science to its innermost necessity and, on the other hand, are able to stand our ground while German destiny is in its most extreme distress.Heidegger also linked the concept of a people with " blood and soil" in a way that would now be regarded as characteristic of Nazism:

The spiritual world of a people is not the superstructure of a culture any more than it is an armory filled with useful information and values; it is the power that most deeply preserves the people’s earth- and blood-bound strengths as the power that most deeply arouses and most profoundly shakes the people’s existence.François Fédier and Beda Allemann argue that this topic was not at that time specifically Nazi. For instance, Austrian-born Israeli philosopher

Martin Buber

Martin Buber ( he, מרטין בובר; german: Martin Buber; yi, מארטין בובער; February 8, 1878 –

June 13, 1965) was an Austrian Jewish and Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism ...

said in 1911: "Blood is the deepest power stratum of the soul" (''Three addresses on Judaism''). In 1936, anti-fascist poet Antonin Artaud wrote that "Any true culture is based on race and blood." Moreover, the 1933–34 lecture course "On the Essence of Truth" contains a clear note of dissent against "blood and soil" as the sole requirement for Dasein:

There is much talk nowadays of blood and soil as frequently invoked powers. Literati, whom one comes across even today, have already seized hold of them. Blood and soil are certainly powerful and necessary, but they are not a sufficient condition for the Dasein of a people.Heidegger's concept of a people is "historical" and not only biological as in

Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ...

, the Nazi Party's chief racial theorist. In his 1941–42 lecture course on Hölderlin's poem "Andenken", Heidegger contends that a people finding itself only in skull measurements and archaeological digs is unable to find itself as a people.

The rectorate speech ended with calls for the German people to "will itself" and "fulfill its historical mission":

Speech to Heidelberg Student Association

In June 1933, Heidegger gave a speech to the Student Association at theUniversity of Heidelberg

}

Heidelberg University, officially the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg, (german: Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg; la, Universitas Ruperto Carola Heidelbergensis) is a public research university in Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, ...

in which he gave clear form to his plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

nian views on the need for the university "to educate the State’s leaders", in the spirit of the Plato's quote ending the Rectorate speech with "All that is great stands in the storm" (''Republic'' 497d9), but also "in the National Socialist spirit" and free from "humanizing, Christian ideas":

Denounced or demoted non-Nazis

According to Farias and Ott, Heidegger also denounced or demoted three colleagues for being insufficiently committed to the Nazi cause. But this has been disputed by Eduard Langwald, who considers "Heidegger was never a Nazi-minded informer".

According to Hugo Ott, Heidegger leaked information on September 29, 1933 to the local minister of education that the chemist Hermann Staudinger had been a pacifist during World War I. Staudinger was a professor of chemistry at Freiburg, and had developed the theory that

According to Farias and Ott, Heidegger also denounced or demoted three colleagues for being insufficiently committed to the Nazi cause. But this has been disputed by Eduard Langwald, who considers "Heidegger was never a Nazi-minded informer".

According to Hugo Ott, Heidegger leaked information on September 29, 1933 to the local minister of education that the chemist Hermann Staudinger had been a pacifist during World War I. Staudinger was a professor of chemistry at Freiburg, and had developed the theory that polymers

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + ''-mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic an ...

were long chain molecule, a theory confirmed by later work and for which Staudinger received the Nobel Prize in 1953. Heidegger knew that the allegation of pacifism could cost Staudinger his job. The Gestapo investigated the matter and confirmed Heidegger's tip. Asked for his recommendation as rector of the university, Heidegger secretly urged the ministry to fire Staudinger without a pension. But nothing eventually happened. As Langwald alleges Heidegger was himself a pacifist since World War I, he doubts that Heidegger could so suddenly become a "pacifist hunter" acting "furiously macho", and asserts Ott did not interpret the facts properly. After Hitler's "Peace Speech" of May 17, 1933, Heidegger more likely wanted to test Staudinger, because as a chemist his researches could become dangerous. Safranski, although he charges Heidegger, recognizes: "It is likely that Heidegger ..may not even have viewed his action as a denunciation. He felt he was a part of the revolutionary movement, and it was his intention to keep opportunists away from the revolutionary awakening. They were not to be allowed to sneak into the movement and use it to their advantage."

Heidegger in the same spirit denounced his former friend Eduard Baumgarten in a letter to the head of the organization of Nazi professors at the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen, (german: Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of Göttingen, Germany. Founded ...

, where Baumgarten had been teaching. He intervened as Baumgarten applied for membership in the SA brownshirts and in the National Socialist Dozentenschaft. In the letter, Heidegger called Baumgarten "anything but a National-Socialist" and underlined his links to "the Heidelberg circle of liberal-democratic intellectuals around Max Weber." But he failed and the opportunistic Baumgarten continued in his career – with the help of the Party. Langwald thinks Heidegger considered Baumgarten as a dangerous pragmatist who could give philosophical weapons to the NS-ideologie.

The Catholic intellectual Max Müller

Friedrich Max Müller (; 6 December 1823 – 28 October 1900) was a German-born philologist and Orientalist, who lived and studied in Britain for most of his life. He was one of the founders of the western academic disciplines of Indian ...

was a member of the inner circle of Heidegger's most gifted students from 1928 to 1933. But Müller stopped attending Heidegger's lectures when Heidegger joined the Nazi party in May 1933. Seven months later, Heidegger fired Müller from his position as a student leader because Müller was "not politically appropriate." Then in 1938 Müller discovered that Heidegger had blocked him from getting a teaching position at Freiburg by informing the university administration that Müller was "unfavorably disposed" toward the regime. Langwald thinks that Heidegger had really no choice but to fire him from his position, as Müller showed too publicly that he was indeed more than "not politically appropriate". Heidegger also fired a Nazi student leader because he was this time too favorably disposed toward the regime (see Picht's testimony).

Attitude towards Jews

On November 3, 1933, Heidegger issued a decree applying the Nazi racial policies to the students of Freiburg university. These laws meant that Jews were now indirectly and directly dissuaded or banned from privileged and superior positions reserved for " Aryan Germans." Heidegger announced that economic aid would henceforth be awarded to students who belonged to the SS, the SA, or other military groups but would be denied to "Jewish or Marxist students" or anyone who fit the description of a "non-Aryan" in Nazi law. After 1933, Heidegger declined to direct the doctoral dissertations of Jewish students: he sent all those students to his Catholic colleague Professor Martin Honecker. And in his letter denouncing Baumgarten, cited above, Heidegger wrote that "after failing with me" ot as a student but as a friend! Baumgarten "frequented, very actively, the Jew Fränkel"—i.e. Eduard Fränkel, a noted professor of classics at Freiburg. Jaspers declared he was surprised by this expression, "the Jew Fränkel", because Heidegger had never been anti-Semitic before. But the reason is perhaps that the only copy of this letter about Baumgarten seems actually not to have been written by Heidegger himself. Moreover, Heidegger did indeed write a "very impressive letter to the Education minister" (Hugo Ott) in July 1933, this one authentic, to defend Eduard Fränkel against the new anti-Semitic law. Heidegger intervened as rector to help several other Jewish colleagues. He wrote appeals in defense of three Jewish professors, including Fränkel, all of whom were about to be fired for racial reasons. Heidegger also helped certain Jewish students and colleagues to emigrate, such as Karl Löwith and his assistant Werner Brock, who found a position respectively in Italy and in England with Heidegger's assistance. There are nevertheless troubling passages from Heidegger's lecture and seminar courses from the period of the Nazi ''Gleichschaltung.'' In a passage reflecting on Heraclitus' fragment 53, "War is the father of all things", in the summer of 1933–34 after the Nazis' first round of anti-semitic legislation (including university employment and enrollment reforms), Heidegger argued in the following terms concerning the need for 'polemos' or 'Kampf' (combat, war and/or struggle) with an internal enemy:The enemy is one who poses an essential threat to the existence of the people and its members. The enemy is not necessarily the outside enemy, and the outside enemy is not necessarily the most dangerous. It may even appear that there is no enemy at all. The root requirement is then to find the enemy, bring him to light or even to create him, so that there may be that standing up to the enemy, and so that existence does not become apathetic. The enemy may have grafted himself onto the innermost root of the existence of a people, and oppose the latter’s ownmost essence, acting contrary to it. All the keener and harsher and more difficult is then the struggle, for only a very small part of the struggle consists in mutual blows; it is often much harder and more exhausting to seek out the enemy as such, and to lead him to reveal himself, to avoid nurturing illusions about him, to remain ready to attack, to cultivate and increase constant preparedness and to initiate the attack on a long-term basis, with the goal of total extermination 'völligen Vernichtung''In his advanced contemporary seminars "On the Essence and Concept of Nature, State and History," Heidegger expostulated in essentialising terms concerning "semitic nomads" and their lack of possible relation to the German homeland, "drifting" in the "unessence of history":

History teaches us that nomads did not become what they are because of the bleakness of the desert and the steppes, but that they have even left numerous wastelands behind them that had been fertile and cultivated land when they arrived, and that men rooted in the soil have been able to create for themselves a native land, even in the wilderness…the nature of our German space would surely be apparent to a Slavic people in a different manner than to us; to a Semitic nomad, it may never be apparent.

Attitude towards his mentor Husserl

Beginning in 1917, the philosopher

Beginning in 1917, the philosopher Edmund Husserl

, thesis1_title = Beiträge zur Variationsrechnung (Contributions to the Calculus of Variations)

, thesis1_url = https://fedora.phaidra.univie.ac.at/fedora/get/o:58535/bdef:Book/view

, thesis1_year = 1883

, thesis2_title ...

championed Heidegger's work, and helped him secure the retiring Husserl's chair in philosophy at the University of Freiburg.

On April 6, 1933, the ''Reichskommissar

(, rendered as "Commissioner of the Empire", "Reich Commissioner" or "Imperial Commissioner"), in German history, was an official gubernatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and Nazi Germany.

Ger ...

'' of Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden i ...

Province, Robert Wagner, suspended all Jewish government employees, including present and retired faculty at the University of Freiburg. Husserl, who was born Jewish and was an adult convert to Lutheran Christianity, was affected by this law. Heidegger did not become Rector until April 22, so it was Heidegger's predecessor as Rector who formally notified Husserl of his "enforced leave of absence" on April 14, 1933. Then, the week after Heidegger's election, the national Reich law of April 28, 1933 came into effect, overriding Wagner's decree, and requiring that all Jewish professors from German universities, including those who had converted to Christianity, be fired. The termination of Husserl's academic privileges thus did not involve any specific action on Heidegger's part.

Heidegger had by then broken off contact with Husserl, other than through intermediaries. Heidegger later stated that his relationship with Husserl had become strained after Husserl publicly "settled accounts" with him and Max Scheler

Max Ferdinand Scheler (; 22 August 1874 – 19 May 1928) was a German philosopher known for his work in phenomenology, ethics, and philosophical anthropology. Considered in his lifetime one of the most prominent German philosophers,Davis, Zach ...

in the early 1930s. However, in 1933 Husserl wrote to a friend, "The perfect conclusion to this supposed bosom friendship of two philosophers was his very public, very theatrical entrance into the Nazi Party on May 1. Prior to that there was his self-initiated break in relations with me – in fact, soon after his appointment at Freiburg – and, over the last few years, his anti-Semitism, which he came to express with increasing vigor – even against the coterie of his most enthusiastic students, as well as around the department."

Heidegger did not attend his former mentor's cremation in 1938. He spoke of a "human failure" and begged pardon in a letter to his wife.

There is no truth to the oft-repeated story that during Heidegger's time as Rector, the University denied Husserl access to the university library. But in 1941, under pressure from publisher Max Niemeyer, Heidegger did agree to remove the dedication to Husserl from ''Being and Time

''Being and Time'' (german: Sein und Zeit) is the 1927 '' magnum opus'' of German philosopher Martin Heidegger and a key document of existentialism. ''Being and Time'' had a notable impact on subsequent philosophy, literary theory and many oth ...

'', but it could still be found in a footnote on page 38, thanking Husserl for his guidance and generosity. Husserl, of course, had died several years earlier. The dedication was restored in post-war editions.Rüdiger Safranski, ''Martin Heidegger: Between Good and Evil'' (Cambridge, Mass., & London: Harvard University Press, 1998), pp. 253–8.

Support for the "Führer principle"

According to Emmanuel Faye, Heidegger supported the "necessity of a

According to Emmanuel Faye, Heidegger supported the "necessity of a Führer

( ; , spelled or ''Fuhrer'' when the umlaut is not available) is a German word meaning "leader" or " guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

Nazi Germany cultivated the ("leader princip ...

" for Germany as early as 1918. But Heidegger spoke actually of the "necessity of leaders" or "guides" ( genitive plural: ''die Notwendigkeit der Führer'') because "only individuals are creative (even to lead), the crowd never", which sounds more platonic than Nazi; Heidegger in the same letter speaks about people who are rightly "appalled at the Pan-Germanic chimerae" after first World War.

In a number of speeches during November 1933, Heidegger endorses the ''Führerprinzip

The (; German for 'leader principle') prescribed the fundamental basis of political authority in the Government of Nazi Germany. This principle can be most succinctly understood to mean that "the Führer's word is above all written law" and th ...

'' ("leader principle"), i.e. the principle that the Führer is the embodiment of the people; that he is always right and that his word is above all written law and demands total obedience. For example, in one speech Heidegger stated:

Let not propositions and 'ideas' be the rules of your being (''Sein''). The Führer alone ''is'' the present and future German reality and its law. Learn to know ever more deeply: that from now on every single thing demands decision, and every action responsibility. Heil Hitler!

In another speech a few days later, Heidegger endorsed the German election of November 1933, in which the electorate was presented with a single Nazi-approved list of candidates:

In another speech a few days later, Heidegger endorsed the German election of November 1933, in which the electorate was presented with a single Nazi-approved list of candidates:

The German people has been summoned by the Führer to vote; the Führer, however, is asking nothing from the people; rather, he ''is giving'' the people the possibility of making, directly, the highest free decision of all: whether itthe entire peoplewants its own existence (''Later in November 1933, Heidegger attended a conference at the University of Tübingen organized by the students of the university and the '' Kampfbund'', the local Nazi Party chapter. In this address, he argued for a revolution in knowledge, a revolution that would displace the traditional idea that the university should be independent of the state:Dasein ''Dasein'' () (sometimes spelled as Da-sein) is the German word for 'existence'. It is a fundamental concept in the existential philosophy of Martin Heidegger. Heidegger uses the expression ''Dasein'' to refer to the experience of being that is p ...''), or whether it does not want it. ..On November 12, the German people as a whole will choose ''its'' future, and this future is bound to the Führer. ..There are not separate foreign and domestic policies. There is only one will to the full existence (''Dasein'') of the State. The Führer has awakened this will in the entire people and has welded it into a single resolve.

We have witnessed a revolution. The state has transformed itself. This revolution was not the advent of a power pre-existing in the bosom of the state or of a political party. The national-socialist revolution means rather the radical transformation of German existence. ..However, in the university, not only has the revolution not yet achieved its aims, it has not even started.Heidegger addressed some of these remarks in the 1966 '' Der Spiegel'' interview " Only a God Can Save Us" (see below). In that interview, he stated: "I would no longer write uch thingstoday. Such things as that I stopped saying by 1934." In a recent book Hans Jonas, a former student of Heidegger, argues that Heidegger's endorsement of the "Führer principle" stemmed from his philosophy and was consistent with it:

But as to Heidegger's being, it is an occurrence of unveiling, a fate-laden happening upon thought: so was the Führer and the call of German destiny under him: an unveiling of something indeed, a call of being all right, fate-laden in every sense: neither then nor now did Heidegger's thought provide a norm by which to decide how to answer such calls—linguistically or otherwise: no norm except depth, resolution, and the sheer force of being that issues the call.Jonas' reading can be supported by citations from Heidegger's lectures during and immediately following the time he was rector. In "On the Essence and Concept of Nature, History and State", for instance, Heidegger appears to give a direct ontological sanction to Hitler's absolute rule:

...The origin of all political action is not in knowledge, but in being. Every ''Führer'' is a ''Führer,'' must be a ''Führer'' talics in original in accordance with the stamp in his being, and simultaneously, in the living unfolding of his proper essence, he understands, thinks, and puts into action what the people and the state are.In his 1934 class on Holderlin, Heidegger is able to comment that "The true and only Fuhrer makes a sign in his being towards the domain 'bereich'', empireof the demigods. Being the Führer is a destiny …”,

Resignation from rectorship

In his postwar justification, Heidegger claimed he resigned the rectorship in April 1934 because the ministry in Karlsruhe had demanded the dismissal of the deans Erik Wolf and Wilhelm von Mollendorf on political grounds. But Rüdiger Safransky found no trace of such events and prefers talking about a disagreement with other Party members. According to the historian Richard J. Evans:By the beginning of 1934, there were reports in Berlin that Heidegger had established himself as 'the philosopher of National Socialism'. But to other Nazi thinkers, Heidegger's philosophy appeared too abstract, too difficult, to be of much use ..Though his intervention was welcomed by many Nazis, on closer inspection such ideas did not really seem to be in tune with the Party's. It is not surprising that his enemies were able to enlist the support ofAlfred Rosenberg Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ..., whose own ambition it was to be the philosopher of Nazism himself. Denied a role at the national level, and increasingly frustrated with the minutiae of academic politicswhich seemed to him to betray a sad absence of the new spirit he had hoped would permeate the universitiesHeidegger resigned his post in April 1934.Richard J. Evans, ''The Coming of the Third Reich'', Penguin Books, 2003, p.421-422

Post-rectorate period

After he resigned from the rectorship, Heidegger withdrew from most political activity but he never withdrew his membership in theNazi party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

. In May 1934 he accepted a position on the Committee for the Philosophy of Law in the Academy for German Law

The Academy for German Law (german: Akademie für deutsches Recht) was an institute for legal research and reform founded on 26 June 1933 in Nazi Germany. After suspending its operations during the Second World War in August 1944, it was abolished ...

( Ausschuß für Rechtphilosophie der Akademie für Deutsches Recht), where he remained active until at least 1936.Emmanuel Faye, Heidegger. ''Die Einführung des Nationalsozialismus in die Philosophie'', Berlin 2009, S. 275–278 The academy had official consultant status in preparing Nazi legislation such as the Nuremberg racial laws that came into effect in 1935. In addition to Heidegger, such Nazi notables as Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and lawyer who served as head of the General Government in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member of the German Workers' Party ...

, Julius Streicher

Julius Streicher (12 February 1885 – 16 October 1946) was a member of the Nazi Party, the ''Gauleiter'' (regional leader) of Franconia and a member of the '' Reichstag'', the national legislature. He was the founder and publisher of the virul ...

, Carl Schmitt

Carl Schmitt (; 11 July 1888 – 7 April 1985) was a German jurist, political theorist, and prominent member of the Nazi Party. Schmitt wrote extensively about the effective wielding of political power. A conservative theorist, he is noted as ...

and Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ...

belonged to the academy and served on this committee. References to Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

continued to appear in Heidegger's work, always in ambiguous ways, suitably disguised for the benefit of the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

spies, according to François Fédier and Julian Young, in order to hide his own version of Nazism, as per Emmanuel Faye. For instance, in a 1935 lecture, he publicly criticized National Socialism, but referred in passing to the "inner truth and greatness of this movement":

What today is systematically touted as the philosophy of National Socialism, but which has nothing in the least to do with the inner truth and greatness of this movement (namely the encounter of a globally determined technology with the man of the new age), darts about with fish-like movements in the murky waters of these 'values' and 'totalities'.Heidegger explained later that:

The whole lecture shows that I was at that time an adversary of the regime. The understanding ears knew therefore how to interpret the sentence. Only the spies of the party whoI knew itsat in my courses, understood the sentence otherwise, as it must be. One had to throw them a crumb here and there in order to keep freedom of teaching and speaking.This lecture was published in 1953 under the title '' An Introduction to Metaphysics''. In the published version, Heidegger left the sentence, but added a parenthetical qualification: "(namely, the confrontation of planetary technology and modern humanity)". Heidegger did not mention that this qualification was added at the time of publication, and was not part of the original lecture. This raised concerns in post-Nazi Germany that Heidegger was distinguishing a "good Nazism" from a "bad Nazism", a contention supported by his philosophical opponents, including Bauemler. The controversial page of the 1935 manuscript is missing from the Heidegger Archives in Marbach. He explained again during the ''Der Spiegel'' interview that "The reason I did not read that passage aloud was because I was convinced my audience would understand me correctly. The stupid ones and the spies and the snoopers understood it differentlyand might as well have, too." In this same course, Heidegger criticized both Russia and the United States: "Seen metaphysically, Russia and America are both the same: the same desolate frenzy of unbounded technology and of the unlimited organization of the average human being." He then calls Germany "the most metaphysical of nations." This is a good example of Heidegger's ambiguous way of speaking, since his students would have known that "metaphysical" in this context is actually a synonym of "technological" and "nihilistic" and therefore a term of harsh criticism. In his 1938 lecture, The Age of the World Picture, he wrote "...the laborious fabrication of such absurd entities as National Socialist philosophies"but didn't read it aloud. Heidegger defended himself during the denazification period by claiming that he had opposed the philosophical bases of Nazism, especially

biologism

Biological determinism, also known as genetic determinism, is the belief that human behaviour is directly controlled by an individual's genes or some component of their physiology, generally at the expense of the role of the environment, whether i ...

and the Nazi interpretation of Nietzsche's '' The Will to Power''.

In a 1936 lecture, Heidegger still sounded rather ambiguous as to whether Nietzsche's thought was compatible with Nazism, or at least with that hypothetical "good Nazism": "The two men who, each in his own way, have introduced a counter movement to nihilismMussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

and Hitlerhave learned from Nietzsche, each in an essentially different way." A subtle correction followed immediately: "But even with that, Nietzsche's authentic metaphysical domain has not yet come unto its own."

According to personal notes made in 1939 (not published until 2006), Heidegger took strong exception to Hitler's statement, "There is no attitude, which could not be ultimately justified by the ensuing usefulness for the totality." Under the heading "Truth and Usefulness", Heidegger's private critique is as follows:

Who makes up this totality? (Eighty million-strong extant human mass? Does its extantness assign to this human mass the right to the claim on a continued existence?) How is this totality determined? What is its goal? Is it itself the goal of all goals? Why? Wherein lies the justification for this goal-setting? ..Why is ''usefulness'' the criterion for the legitmacy of a human attitude? On what is this principle grounded? ..From where does the appeal to usefulness as the measure of truth acquire its comprehensibility? Does comprehensibility justify legitimacy?In a 1942 lecture, published posthumously, Heidegger was once again ambiguous on the subject of Nazism. During a discussion of then recent German classics scholarship, he said that: "In the majority of 'research results', the Greeks appear as pure National Socialists. This overenthusiasm on the part of academics seems not even to notice that with such "results" it does National Socialism and its historical uniqueness no service at all, not that it needs this anyhow."Heidegger, ''

Hölderlin's Hymn "The Ister"

''Hölderlin's Hymn "The Ister"'' (german: Hölderlins Hymne »Der Ister«) is the title given to a lecture course delivered by German philosopher Martin Heidegger at the University of Freiburg in 1942. It was first published in 1984 as volume 53 ...

'' (Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1996), pp. 79–80. Also cited in part by Sheehan, op. cit.

In the same lecture, he commented on America's entry into World War II, in a way that seems to identify his philosophy with the Nazi cause:

The entry of America into this planetary war is not an entry into history. No, it is already the last American act of America's history-lessness and self-destruction. This act is the renunciation of the Origin. It is a decision for lack-of-Origin.

Student testimonials

Among Heidegger's students, Günther Anders saw in Heidegger's lectures a "reactionary potential", and Karl Löwith said that in Rome his master spoke enthusiastically of Hitler. However, most students who attended Heidegger's courses between 1933 and 1945 confirm that he became very soon an adversary of Nazism. Walter Biemel, Heidegger's student in 1942, testified in 1945:Heidegger was the only professor not to give any Nazi salutations prior to beginning his courses, even though it was administratory obligatory. His courses... were among the very rare ones where remarks against National Socialism were risked. Some conversations in those times could cost you your head. I had many such conversations with Heidegger. There is absolutely no doubt he was a declared adversary of the regime.Siegfried Bröse, relieved of his functions as subprefect by the Nazis in 1933, and subsequently one of Heidegger's teaching assistants, wrote to the de-Nazification hearing:

One could seeand this was often confirmed to me by the studentsthat Heidegger lectures were attended ''en masse'' because the students wanted to form a rule to guide their own conduct by hearing National Socialism characterized in all its non-truth... Heidegger's lectures were attended not only by students but also by people with long-standing professions and even by retired people, and every time I had the occasion to talk with these people, what came back incessantly was their admiration for the courage with which Heidegger, from the height of his philosophical position and in the rigor of his starting point, attacked National Socialism.Equally, Hermine Rohner, a student from 1940 to 1943, bears testimony to the fact Heidegger "wasn't afraid, as for him, even in front of students from all faculties (so not only "his" students), to attack National Socialism so openly that I hunched up my shoulders." Due to what he calls Heidegger's "spiritual resistance", Czech resistance fighter and former Heidegger student Jan Patočka included him among his "heroes of our times". The testimony of Karl Löwithwho was not in Germanysounds different. He was another of Heidegger's students, aided by Heidegger in 1933 in obtaining a fellowship to study in Rome, where he lived between 1934 and 1936. In 1936, Heidegger visited Rome to lecture on Hölderlin, and had a meeting with Löwith. In an account set down in 1940 and not intended for publication, Löwith noted that Heidegger was wearing a swastika pin, even though he knew that Löwith was Jewish. Löwith recounted their discussion about editorials published in the '' Neue Zürcher Zeitung'':Karl Löwith, "My last meeting with Heidegger in Rome", in R. Wolin, ed., ''The Heidegger Controversy'' (MIT Press, 1993).

He left no doubt about his faith in Hitler; only two things that he had underestimated: the vitality of the Christian churches and the obstacles to theFor commentators such as Habermas who credit Löwith's account, there are a number of generally shared implications: one is that Heidegger did not turn away from National Socialism ''per se'' but became deeply disaffected with the official philosophy and ideology of the party, as embodied byAnschluss The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938. The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...in Austria. Now, as before, he was convinced that National Socialism was the prescribed path for Germany. told him that ..my opinion was that his taking the side of National Socialism was in agreement with the essence of his philosophy. Heidegger told me unreservedly that I was right and developed his idea by saying that his idea of historicity 'Geschichtlichkeit''was the foundation for his political involvement. In response to my remark that I could understand many things about his attitude, with one exception, which was that he would permit himself to be seated at the same table with a figure such asJulius Streicher Julius Streicher (12 February 1885 – 16 October 1946) was a member of the Nazi Party, the ''Gauleiter'' (regional leader) of Franconia and a member of the '' Reichstag'', the national legislature. He was the founder and publisher of the virul ...(at the German Academy of Law), he was silent at first. At last he uttered this well-known rationalisation (which Karl Barth saw so clearly), which amounted to saying that "it all would have been much worse if some men of knowledge had not been involved." And with a bitter resentment towards people of culture, he concluded his statement: "If these gentlemen had not considered themselves too refined to become involved, things would have been different, but I had to stay in there alone." To my reply that one did not have to be very refined to refuse to work with a Streicher, he answered that it was useless to discuss Streicher; ''Der Stürmer ''Der Stürmer'' (, literally "The Stormer / Attacker / Striker") was a weekly German tabloid-format newspaper published from 1923 to the end of the Second World War by Julius Streicher, the '' Gauleiter'' of Franconia, with brief suspensions ...'' was nothing more than "pornography." Why didn't Hitler get rid of this sinister individual? He didn't understand it.

Alfred Bäumler

Alfred Baeumler (sometimes Bäumler; ; 19 November 1887 – 19 March 1968), was an Austrian-born German philosopher, pedagogue and prominent Nazi ideologue. From 1924 he taught at the Technische Universität Dresden, at first as an unsalaried lec ...

or Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ...

, whose biologistic racist doctrines he never accepted.

Post-war

During the hearings of the Denazification Committee, Hannah Arendt, Heidegger's former student and lover, who was Jewish, spoke on his behalf. (Arendt very cautiously resumed her friendship with Heidegger after the war, despite or even because of the widespread contempt for Heidegger and his political sympathies, and despite his being forbidden to teach for many years.) Heidegger's former friendKarl Jaspers

Karl Theodor Jaspers (, ; 23 February 1883 – 26 February 1969) was a German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher who had a strong influence on modern theology, psychiatry, and philosophy. After being trained in and practicing psychiatry, Jaspe ...

spoke against him, suggesting he would have a detrimental influence on German students because of his powerful teaching presence.

In September 1945, the Denazification Committee published its report on Heidegger. He was charged on four counts: his important, official position in the Nazi regime; his introduction of the ''Führerprinzip'' into the University; his engaging in Nazi propaganda

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi polici ...

and his incitement of students against "reactionary" professors. He was subsequently dismissed from university the same year. In March 1949, he was declared a "follower" (Mitläufer

A (plural , German for " fellow traveller") is a person (the German term has the male grammatical gender; to specifically indicate a female the -in suffix has to be added) believed to be tied to or passively sympathising of certain social movemen ...

) of Nazism by the State Commission for Political Purification. But he was reintegrated in 1951, given emeritus status, and continued teaching until 1976. In 1974, he wrote to his friend Heinrich Petzet: "Our Europe is being ruined from below with 'democracy'".

Thomas Sheehan has noted "Heidegger's stunning silence concerning the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

," in contrast to his criticism of the alienation wrought by modern technologies: "We have his statements about the six millions unemployed at the beginning of the Nazi regime, but not a word about the six million who were dead at the end of it." Heidegger did not publish anything concerning the Holocaust or the extermination camps, but did indeed mention them. In a 1949 lecture entitled "Das Ge-stell" ("Enframing"), he stated:

Agriculture is now a motorized food-industry – in essence, the same as the manufacturing of corpses inCommentators differ on whether these statements are evidence of a profound disregard for the fate of the Jews, or a recontextualization of their suffering in terms of the mechanization of life and death. The French Jewish philosopher Jean-Claude Milner once said: "It's a fact, as to gas chambers, the only proper philosophical sentence is by Heidegger ..It is not satisfactory, but no one else did better." Heidegger's defenders have pointed to the deep ecology dimension of Heidegger's critique of technological "enframing" – i.e., that the way human beings relate to nature has a determining influence on the way we relate to one another. At least Heidegger does not say that the mechanization of agriculture and the extermination camps are equivalent, "the same thing" (''dasselbe'') but "the same" (''das Selbe'', a very strange turn of phrase in German), so only "in essence", but not in the technical or metaphysical meaning of identity. Heidegger explained during his lecture: "The same is never the equivalent (''das Gleiche''). The same is no more only the indistinctive coincidence of the identical. The same is rather the relation of the different." Moreover, many of those who align themselves with Heidegger philosophically have pointed out that in his work on "being-towards-death" we can recognize a much more salient criticism of what was wrong with the mass-produced murder of a people. Thinkers as diverse as Giorgio Agamben and Judith Butler have made this point sympathetically. It might be worth pointing out that the SS physiciangas chambers A gas chamber is an apparatus for killing humans or other animals with gas, consisting of a sealed chamber into which a poisonous or asphyxiant gas is introduced. Poisonous agents used include hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide. History ...and extermination camps, the same as the blockading and starving of nations he_Berlin_blockade_was_then_active.html" ;"title="Berlin_blockade.html" ;"title="he Berlin blockade">he Berlin blockade was then active">Berlin_blockade.html" ;"title="he Berlin blockade">he Berlin blockade was then active the same as the manufacture of hydrogen bombs.

Josef Mengele

, allegiance =

, branch = Schutzstaffel

, serviceyears = 1938–1945

, rank = '' SS''-'' Hauptsturmführer'' (Captain)

, servicenumber =

, battles =

, unit =

, awards =

, commands =

, ...

, the so-called "Angel of Death", was the son of the founder of a company that produced major farm machinery under the name Karl Mengele & Sons. This side of Heidegger's thinking can be seen in another controversial lecture from the same period, ''Die Gefahr'' ("The Danger"):

Hundreds of thousands die en masse. Do they die? They succumb. They are done in. Do they die? They become mere quanta, items in an inventory in the business of manufacturing corpses. Do they die? They are liquidated inconspicuously in extermination camps. And even apart from that, right now millions of impoverished people are perishing from hunger in China. But to die is to endure death in its essence. To be able to die means to be capable of this endurance. We are capable of this only if the essence of death makes our own essence possible.In other words, according to Heidegger, the victims of death camps were deprived not only of their life, but of the dignity of an authentic death, since they were "liquidated" as if they were inventory or problematic accounting, rather than killed in combat as one would kill an enemy. Another citation levied against Heidegger by his critics, is his answer to a question by his former student Herbert Marcuse, concerning his silence about the Nazi racial policies. In a letter to Marcuse, he wrote:

I can add only that instead of the word "Jews" n your letterthere should be the word "East Germans", and then exactly the sameThe reference to East Germans concerns theerror An error (from the Latin ''error'', meaning "wandering") is an action which is inaccurate or incorrect. In some usages, an error is synonymous with a mistake. The etymology derives from the Latin term 'errare', meaning 'to stray'. In statistics ...holds true of one of the Allies, with the difference that everything that has happened since 1945 is public knowledge world-wide, whereas the bloody terror of the Nazis was in fact kept a secret from the German people.''

expulsion of Germans after World War II

Expulsion or expelled may refer to:

General

* Deportation

* Ejection (sports)

* Eviction

* Exile

* Expeller pressing

* Expulsion (education)

* Expulsion from the United States Congress

* Extradition

* Forced migration

* Ostracism

* Persona ...

from territories across eastern Europe, which displaced about 15 million and killed another 0.5–0.6 million, involved gang-rapes and looting throughout East Germany, East Prussia, and Austria, and harshly punitive de-industrialization policies.Alfred de Zayas, ''A Terrible Revenge: The Ethnic Cleansing of the East European Germans, 1944–1950'', (New York: Palgrave/Macmillan, 1994, 2006).

''Der Spiegel'' interview

On September 23, 1966, Heidegger was interviewed byRudolf Augstein

Rudolf Karl Augstein (5 November 1923 – 7 November 2002) was a German journalist, editor, publicist, and politician. He was one of the most influential German journalists, founder and part-owner of '' Der Spiegel'' magazine. As a politician, h ...

and Georg Wolff for '' Der Spiegel'' magazine, in which he agreed to discuss his political past provided that the interview be published posthumously (it was published on May 31, 1976). English translation asOnly a God Can Save Us

by William J. Richardson in

For critical readings of the interview, see In particular the contributions by Jürgen Habermas (), Blanchot (), Derrida (), and Lacoue-Labarthe (). At his own insistence, Heidegger edited the published version of the interview extensively. In the interview, Heidegger defends his involvement with the Nazi party on two points: first, that he was trying to save the university from being completely taken over by the Nazis, and therefore he tried to work with them. Second, he saw in the historic moment the possibility for an "awakening" (''Aufbruch'') which might help to find a "new national and social approach" to the problem of Germany's future, a kind of middle ground between capitalism and communism. For example, when Heidegger talked about a "national and social approach" to political problems, he linked this to

Friedrich Naumann

Friedrich Naumann (25 March 1860 – 24 August 1919) was a German liberal politician and Protestant parish pastor. In 1896, he founded the National-Social Association that sought to combine liberalism, nationalism and (non-Marxist) sociali ...

. According to Thomas Sheehan, Naumann had "the vision of a strong nationalism and a militantly anticommunist socialism, combined under a charismatic leader who would fashion a middle-European empire that preserved the spirit and traditions of pre-industrial Germany even as it appropriated, in moderation, the gains of modern technology".

After 1934, Heidegger claims in the interview, he was more critical of the Nazi government, largely prompted by the violence of the Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (German: ), or the Röhm purge (German: ''Röhm-Putsch''), also called Operation Hummingbird (German: ''Unternehmen Kolibri''), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Ad ...

. When the interviewers asked him about the 1935 lecture in which he had referred to the "inner truth and greatness of he National Socialistmovement" (i.e. the lecture now incorporated into the book ''Introduction to Metaphysics''; see above), Heidegger said that he used this phrase so that Nazi informants who observed his lectures would understand him to be praising Nazism, but his dedicated students would know this statement was no eulogy for the Nazi party. Rather, he meant it as he expressed it in the parenthetical clarification added in 1953, namely, as "the confrontation of planetary technology and modern humanity."

Karl Löwith's account of his meeting with Heidegger in 1936 (discussed above) has been cited to rebut these contentions. According to Lowith, Heidegger did not make any decisive break with Nazism in 1934, and Heidegger was willing to entertain more profound relations between his philosophy and political involvement than he would subsequently admit.

The ''Der Spiegel'' interviewers were not in possession of most of the evidence for Heidegger's Nazi sympathies now known, and thus their questions did not press too strongly on those points. In particular, the ''Der Spiegel'' interviewers did not bring up Heidegger's 1949 quotation comparing the industrialization of agriculture to the extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

s. Interestingly, ''Der Spiegel'' journalist George Wolff had been an '' SS-Hauptsturmführer'' with the ''Sicherheitsdienst

' (, ''Security Service''), full title ' (Security Service of the '' Reichsführer-SS''), or SD, was the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Established in 1931, the SD was the first Nazi intelligence organization ...

'', stationed in Oslo during World War II, and had been writing articles with antisemitic and racist overtones in ''Der Spiegel'' since war's end.

Meeting with Paul Celan

In 1967, Heidegger met with the poet Paul Celan, a Jew who had survived concentration camps operated by the Nazis' Romanian allies. On July 24 Celan gave a reading at the University of Freiburg, attended by Heidegger. Heidegger there presented Celan with a copy of ''What is Called Thinking?'', and invited him to visit him at his hut at '' Todtnauberg'', an invitation which Celan accepted. On July 25 Celan visited Heidegger at his retreat, signing the guestbook and spending some time walking and talking with Heidegger. The details of their conversation are not known, but the meeting was the subject of a subsequent poem by Celan, entitled "Todtnauberg" (dated August 1, 1967). The enigmatic poem and the encounter have been discussed by numerous writers on Heidegger and Celan, notably Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe. A common interpretation of the poem is that it concerns, in part, Celan's wish for Heidegger to apologize for his behavior during the Nazi era.The Farias and Faye controversies

Although Heidegger's involvement with Nazism was known and had already divided philosophers, the publication, in 1987, of Victor Farias' book ''Heidegger and Nazism

Martin Heidegger (; ; 26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th centur ...

'' provoked the topic to an open controversy. Farias had access to many documents, including some preserved in the STASI archives. The book, which tries to show that Heidegger supported Hitler and his racial policies and also denounced or demoted colleagues, was highly acclaimed but also starkly criticised. The American philosopher Richard Rorty

Richard McKay Rorty (October 4, 1931 – June 8, 2007) was an American philosopher. Educated at the University of Chicago and Yale University, he had strong interests and training in both the history of philosophy and in contemporary analytic ...