March 1965 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The following events occurred in March 1965:

The following events occurred in March 1965:

*''

*''

*Died:

*Died:

*Two days before the opening of a European conference in Vienna to discuss a common system of color television, France announced that it had signed an accord with the Soviet Union to adopt the French version, SECAM (Séquentiel couleur avec mémoire), which was competing with West Germany's PAL (Phase Alternating Line) system. The result at the Vienna Conference would be that all of the other Western European nations except France would use PAL, while SECAM would be used in Eastern Europe and France. North America and much of Latin America would use the NTSC (National Television System Committee) standard.

*Quoting Associated Press photographer Horst Faas and unidentified sources, AP reporter Peter Arnett broke the story that U.S. and South Vietnamese forces were using gas warfare in combat. Though he emphasized that these were "non-lethal" gases dispensed by helicopters and bombers, Arnett wrote that "one gas reportedly causes extreme nausea and vomiting, another loosens the bowels". Hours after the story was revealed, a spokesman for the U.S. Department of Defense confirmed for afternoon papers the story about the use of gas, but said that it was only being used by "South Vietnam's armed forces". Two days later, U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk would hold a press conference to respond to the controversy saying, "We are not embarking upon gas warfare in Vietnam. There has been no policy decision to engage in gas warfare in Vietnam. We are not talking about agents or weapons that are associated with gas warfare... We are not talking about gas that is prohibited by the Geneva Convention of 1925."

* Nicolae Ceauşescu was unanimously elected the new First Secretary by the Central Committee of the

*Two days before the opening of a European conference in Vienna to discuss a common system of color television, France announced that it had signed an accord with the Soviet Union to adopt the French version, SECAM (Séquentiel couleur avec mémoire), which was competing with West Germany's PAL (Phase Alternating Line) system. The result at the Vienna Conference would be that all of the other Western European nations except France would use PAL, while SECAM would be used in Eastern Europe and France. North America and much of Latin America would use the NTSC (National Television System Committee) standard.

*Quoting Associated Press photographer Horst Faas and unidentified sources, AP reporter Peter Arnett broke the story that U.S. and South Vietnamese forces were using gas warfare in combat. Though he emphasized that these were "non-lethal" gases dispensed by helicopters and bombers, Arnett wrote that "one gas reportedly causes extreme nausea and vomiting, another loosens the bowels". Hours after the story was revealed, a spokesman for the U.S. Department of Defense confirmed for afternoon papers the story about the use of gas, but said that it was only being used by "South Vietnam's armed forces". Two days later, U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk would hold a press conference to respond to the controversy saying, "We are not embarking upon gas warfare in Vietnam. There has been no policy decision to engage in gas warfare in Vietnam. We are not talking about agents or weapons that are associated with gas warfare... We are not talking about gas that is prohibited by the Geneva Convention of 1925."

* Nicolae Ceauşescu was unanimously elected the new First Secretary by the Central Committee of the

* Ranger 9 impacted into the Alphonsus crater on the Moon at 9:08 a.m. Eastern Time, after taking 6,150 high resolution photos and transmitting them to Earth. For the first time, viewers were able to watch lunar photos on live television as the digital data from the probe was being assembled.

*U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy became the first person to reach the top of the tall

* Ranger 9 impacted into the Alphonsus crater on the Moon at 9:08 a.m. Eastern Time, after taking 6,150 high resolution photos and transmitting them to Earth. For the first time, viewers were able to watch lunar photos on live television as the digital data from the probe was being assembled.

*U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy became the first person to reach the top of the tall

The following events occurred in March 1965:

The following events occurred in March 1965:

March 1, 1965 (Monday)

* The first general election in the Bechuanaland Protectorate to feature universal suffrage took place throughout the former British colony and African protectorate. The Bechuanaland Democratic Party won 28 of the 31 seats in the new parliament, and the BDP leader, Sir Seretse Khama, became the first prime minister. Bechuanaland would be granted independence from the United Kingdom in 1966 as Botswana. Khama, who had been destined to become the Chief Khama IV of the Bamangwato tribe, had been ostracized for his interracial marriage to a white British woman, Ruth Williams, and exiled from his homeland until 1956, then returned to even greater popularity. *The United States Supreme Court rendered its opinion in ''Freedman v. Maryland

''Freedman v. Maryland'', 380 U.S. 51 (1965), was a United States Supreme Court case that ended government-operated rating boards with a decision that a rating board could only approve a film and had no power to ban a film. The ruling also con ...

'', unanimously striking down a Maryland censorship law that had given the state censor the authority to ban the showing of a film and putting the burden on the film exhibitor to file a lawsuit in order to appeal. Under the new rule, it would become the burden of the censor to prove that a film content was not protected by the U.S. Constitution, and the censor would now have the burden of filing for an injunction against the showing of a film. The guidelines of the ruling would apply to all state censorship laws.

*On March 1 and 2, Office of Manned Space Flight held the Gemini crewed space flight design certification review in Washington, D.C.. Chief executives of all major Gemini contractors certified the readiness of their products for human spaceflight

Human spaceflight (also referred to as manned spaceflight or crewed spaceflight) is spaceflight with a crew or passengers aboard a spacecraft, often with the spacecraft being operated directly by the onboard human crew. Spacecraft can also be ...

. Gemini 3 was ready for launch as soon as the planned test and checkout procedures at Cape Kennedy were completed.

*Olympic swimming champion and 1964 Australian of the Year

The Australian of the Year is a national award conferred on an Australian citizen by the National Australia Day Council, a not-for-profit Australian Governmentowned social enterprise. Similar awards are also conferred at the State and Territo ...

Dawn Fraser was banned from competition for ten years by the Australian Amateur Swimming Union, in apparent disapproval of her partying lifestyle and for her behavior during the 1964 Summer Olympics

The , officially the and commonly known as Tokyo 1964 ( ja, 東京1964), were an international multi-sport event held from 10 to 24 October 1964 in Tokyo, Japan. Tokyo had been awarded the organization of the 1940 Summer Olympics, but this ho ...

.

*At 8:12 a.m., a natural gas explosion at the La Salle Heights Apartments in La Salle, Quebec

LaSalle () is the most southerly borough (''arrondissement'') of the city of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It is located in the south-west portion of the Island of Montreal, along the Saint Lawrence River. Prior to 2002, it was a separate municipalit ...

killed 28 people. Eighteen of the apartment units in the three-story building at Bergevin and Jean Milot Streets were destroyed, and most of the dead were children.

* Bruce McLaren won the 1965 Australian Grand Prix

The 1965 Australian Grand Prix was a motor race held at the Longford Circuit in Tasmania, Australia on 1 March 1965.Longford Programme, 30th Australian Grand Prix Meeting 1965 – Second Day It was open to Racing Cars complying with the Australi ...

, held at the Longford Circuit

The Longford Circuit was a temporary motor racing course laid out on public roads at Longford, south-west of Launceston in Tasmania, Australia. It was located on the northern edges of the town and its lap passed under a railway line viaduct ...

at Launceston, Tasmania

Launceston () or () is a city in the north of Tasmania, Australia, at the confluence of the North Esk and South Esk rivers where they become the Tamar River (kanamaluka). As of 2021, Launceston has a population of 87,645. Material was copied ...

, but the race was marred by a crash that killed driver Rocky Tresise and a cameraman, Robin Babera.

*The U.S. made its first underground silo launch of the new Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

. The test took place at Ellsworth Air Force Base

Ellsworth Air Force Base (AFB) is a United States Air Force base located about northeast of Rapid City, South Dakota, just north of the town of Box Elder, South Dakota, Box Elder.

The host unit at Ellsworth is the 28th Bomb Wing (28 BW). Assi ...

near Rapid City, South Dakota.

*East African members of the British Commonwealth began negotiations with the "Common Market" (European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

).

*Born:

**Booker T Booker T or Booker T. may refer to

* Booker T. Washington (1856–1915), African American political leader at the turn of the 20th century

** List of things named after Booker T. Washington, some nicknamed "Booker T."

* Booker T. Jones (born 1944) ...

, American professional wrestling champion and promoter; as Robert Brooker Tio Huffman in Plain Dealing, Bossier, Louisiana

** Mike Dean, American record producer, audio engineer and multi-instrumentalist; in Houston

**Stewart Elliott

Stewart Elliott (born March 1, 1965) is an American thoroughbred jockey.

Elliott was born, in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. He grew up in horse racing; his father was a jockey for many years, his mother rode show horses and was a riding instructor ...

, Canadian-born American thoroughbred racing jockey; in Toronto

March 2, 1965 (Tuesday)

*Canadian drug lord and mobsterLucien Rivard

Lucien Rivard (June 16, 1914 – February 3, 2002) was a Quebec criminal known for a sensational prison escape in 1965.

Background

Rivard had been engaged in robbery and smuggling drugs since the 1940s. He has been described as a "petty crook" in ...

escaped from the Bourdeaux Jail in Montreal, where he had been held for ten months while fighting extradition to the United States to face charges of drug trafficking. At about 6:20 p.m., Rivard and a fellow inmate, Andre Durocher, asked one of the guards for permission to get a hose "so they could flood the jail's hockey rink". After a guard escorted them to the storage room, Durocher pointed a gun (which was actually a carved piece of wood covered with black shoe polish) at the guard, tied him and two maintenance workers up with wire, overpowered another guard and took his shotgun, scaled the high wall around the jail with a ladder, used the hose to slide to the ground, hijacked a car that was stopped at a traffic light, and made their escape. The incident would lead to a scandal in which the members of the cabinet of Prime Minister Lester Pearson

Lester Bowles "Mike" Pearson (23 April 1897 – 27 December 1972) was a Canadian scholar, statesman, diplomat, and politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Canada from 1963 to 1968.

Born in Newtonbrook, Ontario (now part of ...

were accused of complicity in the escape, and which would ultimately lead to the resignation of Canada's Minister of Justice, Guy Favreau

Guy Favreau, (May 20, 1917 – July 11, 1967) was a Canadian lawyer, politician and judge.

Born in Montreal, Quebec, the son of Léopold Favreau and Béatrice Gagnon, he obtained a Bachelor of Arts and an LL.B. from the Université de Mon ...

. Rivard would be recaptured on July 16 at a cottage southwest of the jail.

* Operation Rolling Thunder, the daily bombing of North Vietnam by the United States, began as the 8th and the 13th Bomber Squadrons set off from the Biên Hòa Airfield with eight B-57 Canberra bombers and the protection of F-100 Super Sabres. The first raid was on an ammunition dump at Xom Bong, in North Vietnamese territory north of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), and did serious damage, but at the cost of three F-105

The Republic F-105 Thunderchief is an American supersonic fighter-bomber that served with the United States Air Force from 1958 to 1984. Capable of Mach 2, it conducted the majority of strike bombing missions during the early years of the Viet ...

and two F-100 fighters, and the capture of the one surviving pilot of the five; a historian would later note, "America was shocked that its large, high-tech, expensive air force, in combat for the first time since the Korean War, had been humbled by a third world country, a communist one at that." The operation would have 700,000 sorties until its halt on October 31, 1968, without bringing any visible end to the Vietnam War. "Rolling Thunder's ultimate failure came as a result of an inappropriate strategy that dictated a conventional air war against North Vietnam to affect what was basically an unconventional war in South Vietnam."

*'' The Sound of Music'', starring Julie Andrews

Dame Julie Andrews (born Julia Elizabeth Wells; 1 October 1935) is an English actress, singer, and author. She has garnered numerous accolades throughout her career spanning over seven decades, including an Academy Award, a British Academy Fi ...

and Christopher Plummer in 20th Century Fox's film adaptation of the Rodgers & Hammerstein musical

Musical is the adjective of music.

Musical may also refer to:

* Musical theatre, a performance art that combines songs, spoken dialogue, acting and dance

* Musical film and television, a genre of film and television that incorporates into the narr ...

, premiered at the Rivoli Theater in New York City. It would be released in Los Angeles on March 10, and elsewhere in the U.S. on the Wednesdays that followed. "Sneak" previews had also been held on January 15 at the Mann Theatre in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and in Tulsa, Oklahoma the next day.

*In the U.S. city of Philadelphia, four men were driving past the Fidelity Philadelphia Trust Company bank when they spotted a bag that had been accidentally dropped by a Brink's armored car, and picked up what turned out to be $40,000 in cash (worth more than $300,000 fifty years later). They were arrested four days later after one of the group used some of his newfound wealth to buy a 1963 Cadillac automobile.

*An avalanche in the Austrian Alps killed 14 college students from Sweden. The students were passengers on a bus that was taking them to the ski resort at Obertauern

Obertauern is a tourist destination which is located in the Radstädter Tauern in the Salzburger Land of Austria. The winter sports resort is separated in two communities: Tweng and Untertauern.

Geography

Obertauern lies in the southeast o ...

, and were on the Radstadt Tauern road. They died after falling rocks swept the vehicle down into a valley below.

*The U.S. space program suffered a setback when a $12,000,000 Atlas-Centaur rocket exploded during an attempted uncrewed launch. The rocket "rose about three feet from its pad, lost power from two of its three engines, crashed back to the ground and erupted into a brilliant orange ball of fire".

March 3, 1965 (Wednesday)

*The bombing raids by the United States against North Vietnam were not a "war", according to a U.S. State Department release. The bombing "does not bring about the existence of a state of war, which is a legal characterization rather than an actual description," a spokesman wrote. Instead, there was "armed aggression from the north against the Republic of Viet Nam" and "Pursuant to South Viet Nam's request and consultations between our two governments, the Republic of Viet Nam and the United States are engaged in collective defense against that armed aggression." * Wilbur Mills, the Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, "pulled a 'legislative coup' that would forever change the nation's health care system" with the surprise recommendation that all three of the alternative proposals for health care should be combined. The result would be that the Social Security Amendments of 1965 would have the Democrats' King-Anderson Bill as "Medicare Part A", the Republicans' "Bettercare" bill would become "Medicare Part B", and the "Eldercare" bill would become Medicaid. *Congress voted to repeal a requirement that one-fourth of bank deposit liabilities of the Federal Reserve System had to be matched by an equivalent amount of gold. The rule had been in effect for 52 years since the passage of the original Federal Reserve Act in 1913. President Johnson signed the bill into the law the next day. The requirement of gold backing for one-fourth of bank notes on deposit in the 12 Federal Reserve System would continue until March 18, 1968. *The U.S. House of Representatives voted 257–165 to approve theAppalachian Regional Development Act The Appalachian Regional Development Act of 1965 established the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), which was tasked with overseeing economic development programs in the Appalachia region, as well as the construction of the Appalachian Developme ...

, the first of the War on Poverty bills, a month after the U.S. Senate had given 62–22 approval. President Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

would sign the one-billion-dollar measure, which provided $1,092,200,000 toward highway construction and other projects, on March 9.

* Lincoln City, Oregon was created by the merger of five towns (Cutler City, Delake, Nelscott, Oceanlake and Taft). The name, suggested by a group of schoolchildren, was selected in a contest.

*Born: Dragan Stojković, Serbian footballer and football manager; in Niš, Yugoslavia

*Died: Renato Biasutti

Renato Biasutti (San Daniele del Friuli, 22 March 1878 – Florence, 3 March 1965) was a notable Italian geographer, who published many works on physical anthropology.

Life

He studied in the University of Florence under the guidance of Giovann ...

, 76, Italian geographer and physical anthropologist who wrote ''The Races and People of the World'', classifying ''homo sapiens'' into "five subspecies, sixteen primary races, and fifty-two secondary races".

March 4, 1965 (Thursday)

*At 6:04 a.m., a neighborhood in Natchitoches, Louisiana, was destroyed and 17 people were killed by the explosion of a natural gas pipeline. The blast left a deep crater where seven homes had stood. The disaster was later traced to high pressure that had ruptured the pipe; an area of of land was incinerated, and pieces of metal weighing hundreds of pounds were hurled as far as by the explosion. *An angry mob assembled at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow to protest the bombing of North Vietnam, before finally being driven away by police on horseback and soldiers. The next day, the Soviet Union formally apologized to the U.S. government and began replacement of 310 broken windows in the ten-story high embassy building, and the removal of stains from more than 200 inkpots that had been shattered against the walls. *The government of British Prime MinisterHarold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

survived a censure motion in the House of Commons by a margin of only five votes, with 293 in favor of the condemnation of his national defense policy, and 298 against.

*The U.S. formally requested New Zealand to participate in the Vietnam War. Prime Minister Keith Holyoake did not respond initially, and a second request would be sent eight days later.

*Born: Khaled Hosseini

Khaled Hosseini (;Pashto/Dari ; born March 4, 1965) is an Afghan Americans, Afghan-American novelist, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR goodwill ambassador, and former physician. His debut novel ''The Kite Runner'' (2003) wa ...

, Afghan novelist; in Kabul

*Died: Willard Motley

Willard Francis Motley (July 14, 1909 – March 4, 1965) was an American writer. Motley published a column in the African-American oriented ''Chicago Defender'' newspaper under the pen-name Bud Billiken. He also worked as a freelance writer, and ...

, 55, African-American novelist and author of ''Knock on Any Door'', later adapted for film

March 5

Events Pre-1600

* 363 – Roman emperor Julian leaves Antioch with an army of 90,000 to attack the Sasanian Empire, in a campaign which would bring about his own death.

* 1046 – Nasir Khusraw begins the seven-year Middle Eastern ...

, 1965 (Friday)

*After stripping Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, a ...

of his World Boxing Association heavyweight title, the WBA staged a bout in Chicago for a new "world champion" to replace Ali. Ernie Terrell defeated Eddie Machen in a unanimous decision by the fight judges. "To the man in the street, Ali may have been a Black Muslim... he may have come across as a brash young pain-in-the-ass. He may have been all these of these things," an author would later note, "but until he lost, retired or died, he was the champion. Consequently, when Terrell outpointed Machen, few cared."

*The Bahrain Petroleum Company (BAPCO) announced that it was laying off hundreds of Bahraini workers, an event that triggered what is now referred to as the March Intifada. On March 9, the rest of the Bahraini employees of BAPCO went out on strike, and were joined by student protesters who soon took out their frustrations on cars owned by Europeans in the British protectorate on the Arabian peninsula.

*The Kilauea volcano in Hawaii erupted at 9:43 a.m., through a series of fissures that extended for nearly eight miles from the Makaaopuhi Crater to the Napau Crater. Within the first eight hours, 15 million cubic meters of lava would pour out of the ground.

* Edward R. Murrow, director of the United States Information Agency, was named an Honorary Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. She was queen ...

, less than two months before his death.

* ONGC Videsh Limited, India's entry into the field of international oil exploration, was incorporated as Hydrocarbons India Ltd. Within 50 years, it would be participating in 39 projects in 15 nations.

*Legendary guitarist Jeff Beck

Geoffrey Arnold Beck (born 24 June 1944) is an English rock guitarist. He rose to prominence with the Yardbirds and after fronted the Jeff Beck Group and Beck, Bogert & Appice. In 1975, he switched to a mainly instrumental style, with a focus ...

performed his first major concert, after being hired by The Yardbirds to replace Eric Clapton

Eric Patrick Clapton (born 1945) is an English rock and blues guitarist, singer, and songwriter. He is often regarded as one of the most successful and influential guitarists in rock music. Clapton ranked second in ''Rolling Stone''s list of ...

. Beck's introduction came at Fairfield Halls

Fairfield Halls is an arts, entertainment and conference centre in Croydon, London, England, which opened in 1962 and contains a theatre and gallery, and a large concert hall regularly used for BBC television, radio and orchestral recordings. Fa ...

in Croydon.

*Died:

** Chen Cheng, 68, Chinese political and military leader

** Helen Waddell, 75, Irish poet and playwright

March 6, 1965 (Saturday)

* Tunisia's PresidentHabib Bourguiba

Habib Bourguiba (; ar, الحبيب بورقيبة, al-Ḥabīb Būrqībah; 3 August 19036 April 2000) was a Tunisian lawyer, nationalist leader and statesman who led the country from 1956 to 1957 as the prime minister of the Kingdom of T ...

broke with the leaders of the rest of the Arab nations in North Africa and the Middle East, and called for the recognition of Israel, within the borders that had been set by the United Nations, in 1947, for separate Jewish and Arab states, though "all it earned him was a violent campaign of hate and vilification".

* Fayzulla Khodzhayev, who had served as the leader of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic until his arrest in 1937 on orders of Soviet premier Joseph Stalin, was rehabilitated posthumously by the Soviet government, almost 27 years after he had been among the people executed after the "Trial of the Trotskyite and Rightist Bloc of 21".

*Indonesia hosted the first Africa-Asia Islamic Conference (KIAA, Konferensi Islam Afrika-Asia), with 107 delegates from 33 nations traveling to Bandung

Bandung ( su, ᮘᮔ᮪ᮓᮥᮀ, Bandung, ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of West Java. It has a population of 2,452,943 within its city limits according to the official estimates as at mid 2021, making it the fourth most ...

.

*Chinese students protested at the Soviet Embassy in Beijing, criticizing the USSR's use of force in breaking up the March 4 demonstration in Moscow.

*Red Army General Nikolai F. Vatutin, leader of the Ukrainian Front, was declared a Hero of the Soviet Union, 21 years after his death.

*Died:

** Herbert Morrison, 77, former Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1945–51)

** Margaret Dumont, 82, American film actress best known as the foil for Groucho Marx

Julius Henry "Groucho" Marx (; October 2, 1890 – August 19, 1977) was an American comedian, actor, writer, stage, film, radio, singer, television star and vaudeville performer. He is generally considered to have been a master of quick wit an ...

March 7

Events Pre-1600

* 161 – Marcus Aurelius and L. Commodus (who changes his name to Lucius Verus) become joint emperors of Rome on the death of Antoninus Pius.

* 1138 – Konrad III von Hohenstaufen was elected king of Germany at Cob ...

, 1965 (Sunday)

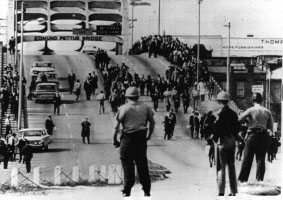

* A march of 550 civil rights demonstrators was broken up violently by 200 members of the Alabama Highway Patrol

The Alabama Highway Patrol is the ''de facto'' highway patrol organization for the U.S. state of Alabama, and which has full jurisdiction anywhere in the State. The Alabama Highway Patrol was created in 1936. Since its establishment, 29 officers h ...

, as the protesters began their march from Selma, Alabama

Selma is a city in and the county seat of Dallas County, in the Black Belt region of south central Alabama and extending to the west. Located on the banks of the Alabama River, the city has a population of 17,971 as of the 2020 census. About ...

, to the state capital at Montgomery. In response to the killing of Jimmie Lee Jackson

Jimmie Lee Jackson (December 16, 1938 – February 26, 1965) was an African American civil rights activist in Marion, Alabama, and a deacon in the Baptist church. On February 18, 1965, while unarmed and participating in a peaceful voting rig ...

. Hosea Williams and John Lewis started from the Brown Chapel AME Church and proceeded over the Edmund Pettus Bridge on U.S. Route 80

U.S. Route 80 or U.S. Highway 80 (US 80) is a major east–west United States Numbered Highway in the Southern United States, much of which was once part of the early auto trail known as the Dixie Overland Highway. As the "0" in the rou ...

with a petition for Alabama Governor George C. Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist and ...

. Reverend Frederick D. Reese

Frederick Douglas Reese (November 28, 1929 – April 5, 2018) was an American civil rights activist, educator and minister from Selma, Alabama. Known as a member of Selma's "Courageous Eight", Reese was the president of the Dallas County Voters L ...

would recall later that the officer in charge of the troopers told them, "I have orders from the Governor. You cannot march down Highway 80. This is for your protection." When the marchers began kneeling in prayer rather than turning back, "the troopers came forward and began beating the people with billy clubs" then dispersed the crowd with tear gas. When the marchers moved back across the bridge into Dallas County Dallas County may refer to:

Places in the USA:

* Dallas County, Alabama, founded in 1818, the first county in the United States by that name

* Dallas County, Arkansas

* Dallas County, Iowa

* Dallas County, Missouri

* Dallas County, Texas, the nint ...

, members of the county sheriff's department began beating the group again. The event would be commemorated in the American civil rights movement as "Bloody Sunday".

*Changes to the Liturgy of the Roman Catholic Mass took place throughout the world, with large parts of the Mass being said in local languages (the vernacular) for the first time, rather than in Latin, as the papal instruction ''Inter oecumenici'' became effective on the first Sunday of Lent following the 1964 reform. In Rome, Pope Paul VI conducted services in Italian at the small All Saints Church as part of a plan to substitute for the parish priest in five suburban Rome churches during the Lent season.

*Died: Queen Louise, 75, consort of Sweden and wife of King Gustaf VI Adolf

Gustaf VI Adolf (Oscar Fredrik Wilhelm Olaf Gustaf Adolf; 11 November 1882 – 15 September 1973) was King of Sweden from 29 October 1950 until his death in 1973. He was the eldest son of Gustaf V and his wife, Victoria of Baden. Before Gustaf Ado ...

. Born Louise Mountbatten and a great-granddaughter of Britain's Queen Victoria, Louise was beloved by her subjects as "''vår drottning''" ("our queen") "because she shopped in Stockholm's stores and markets just like any housewife".

March 8, 1965 (Monday)

*The Court also invalidated, in '' Louisiana v. United States'', the "interpretation test" clause of the Louisiana state constitution, which provided that a voter had to interpret a random section of either the state or federal constitution "to the satisfaction of the registrar". As Justice Hugo Black noted in the unanimous opinion, less than one percent of African-Americans were registered to vote between 1921 and 1944, and the only 15% were registered at the time the suit was filed. "This is not a test, but a trap," Black wrote, "sufficient to stop even the most brilliant man on his way to the voting booth... The cherished right of people in a country like ours to vote cannot be obliterated by... the passing whim or impulse of a voting registrar." *At 9:02 a.m. local time, the first American military combat troops arrived inSouth Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

as 1,400 members of the United States Marines in combat gear came ashore at Da Nang Bay. The men of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade were the first of 3,500 troops from the 3rd Marine Regiment

The 3rd Marine Littoral Regiment is a regiment of the United States Marine Corps that is optimized for littoral maneuver in the Indo-Pacific Theater. Based at Marine Corps Base Hawaii, the regiment falls under the command of the 3rd Marine Divisi ...

of the 3rd Marine Division

The 3rd Marine Division is a division of the United States Marine Corps based at Camp Courtney, Marine Corps Base Camp Smedley D. Butler in Okinawa, Japan. It is one of three active duty infantry divisions in the Marine Corps and together with th ...

. The amphibious force ships '' Mount McKinley'', '' Vancouver'', '' Henrico'', and '' Union'' delivered two battalions, relocated from Okinawa to guard the American air base at Da Nang. Although there were 23,000 American military personnel in South Vietnam already, the deployment represented "the first body of Americans to go to the embattled southeast Asian nation as a fighting military unit."

*Emile Zuckerkandl

Émile Zuckerkandl (July 4, 1922 – November 9, 2013) was an Austrian-born French biologist considered one of the founders of the field of molecular evolution. He introduced, with Linus Pauling, the concept of the "molecular clock", which enabl ...

and Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific top ...

published their groundbreaking paper, "Molecules as Documents of Evolutionary History", in the '' Journal of Theoretical Biology'', applying their 1962 theory of the " molecular clock" to a proof "that genes can be used to determine when different organisms evolutionarily diverge", by comparing molecules of different species to estimate when divergence took place.

*Nine passengers on board Aeroflot Flight 513

Aeroflot Flight 513 was a domestic scheduled passenger flight operated by Aeroflot that crashed during takeoff from Kuybyshev Airport in the Soviet Union on 8 March 1965, resulting in the deaths of 30 passengers and crew. It was the first fatal ...

were the only survivors when the plane crashed shortly after takeoff from Kuybyshev (now Samara) on a flight toward Rostov. Thirty other people, including the entire nine-member crew, were killed when the Tu-124 jet dropped from a height of about .

*The U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in ''United States v. Seeger

''United States v. Seeger'', 380 U.S. 163 (1965), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court ruled that the exemption from the military draft for conscientious objectors could be reserved not only for those professing conformity with the ...

'' expanded the allowable grounds for conscientious objection to being drafted.

*Born: Claudia Webbe, British Labour Party politician; in Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

March 9, 1965 (Tuesday)

*In their second attempt to march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, under the leadership of Martin Luther King Jr., civil rights activists were stopped by state police at the bridge that had been the scene of violence two days earlier. Obeying a courtrestraining order

A restraining order or protective order, is an order used by a court to protect a person in a situation involving alleged domestic violence, child abuse, assault, harassment, stalking, or sexual assault.

Restraining and personal protection or ...

, the group halted, and King asked State Police Major John Cloud (who said "This march is not conducive to the safety of those using the highways") whether he objected to a prayer being led by religious leaders who were present. "You can have your prayer, and then return to the church," Cloud said. After being led in prayer by Ralph Abernathy, King led the group back and vowed to march again. Later in the day, white supremacists fractured the skull of a young white Unitarian Universalist minister, Reverend James J. Reeb

James Joseph Reeb (January 1, 1927 – March 11, 1965) was an American Unitarian Universalist minister, pastor, and activist during the civil rights movement in Washington, D.C. and Boston, Massachusetts. While participating in the Selma to M ...

, in Selma. Three men were arrested by Selma city police for the armed assault, released on bail, and immediately re-arrested by the FBI for charges of violating Reeb's civil rights.

*British and South African police detectives in Durban, South Africa, recovered 20 gold bars

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile meta ...

, valued at $280,000, that had been missing from the ocean liner ''Capetown Castle'' for more than a month. The bars, shipped by the South African government and entrusted to the Bank of England, had been reported missing on February 5 when the ship had docked at Southampton. The value was based on the international price of gold at the time of 35 dollars per troy ounce and the weight (400 oz t or 12.4 kg) of each bar. Fifty years later, in March 2015, the price of gold was $1,226.14 per ounce, a gold bar would be worth $490,456 and twenty bars would be worth more than 9.8 million dollars.

*The United States launched OSCAR 3

OSCAR 3 (a.k.a. OSCAR III) is the third amateur radio satellite launched by Project OSCAR into Low Earth Orbit. OSCAR 3 was launched March 9, 1965 by a Thor-DM21 Agena D launcher from Vandenberg Air Force Base, Lompoc, California. The satellite, ...

, the third in the Orbiting Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio series, and the first to have a transponder to allow amateur radio operators to communicate with each other. Over the next two weeks, "more than 100 amateurs in 16 countries" were able to talk to each other until the satellite's batteries ceased working.

*President Johnson authorized the use of a newer, more flammable version of napalm B for the anti-personnel bombs dropped by American bombers in Vietnam.

*Born: Benito Santiago, Puerto Rican American Major League Baseball player, 3-time Gold Glove Award

The Rawlings Gold Glove Award, usually referred to as simply the Gold Glove, is the award given annually to the Major League Baseball (MLB) players judged to have exhibited superior individual fielding performances at each fielding position in bo ...

and 4-time Silver Slugger Award winner; in Ponce, Puerto Rico

*Died: Kazys Boruta

Kazys Boruta (6 January 1905, in Kūlokai, near Marijampolė – 9 March 1965, in Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or ...

, 60, Soviet Lithuanian poet

March 10, 1965 (Wednesday)

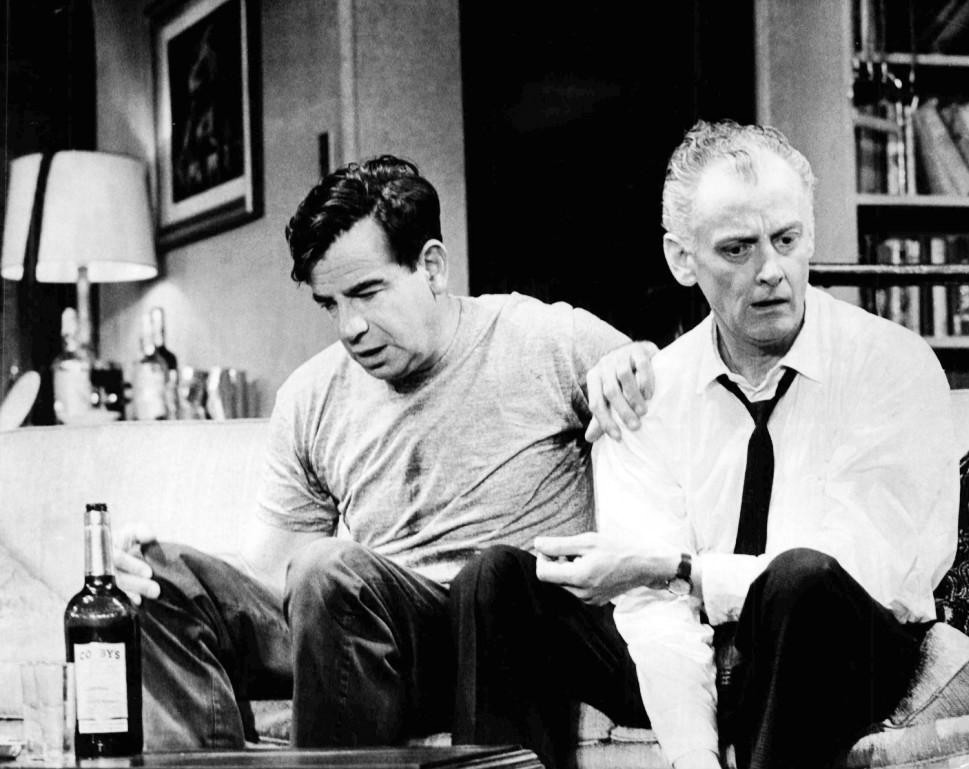

The Odd Couple Odd Couple may refer to:

Neil Simon play and its adaptations

* ''The Odd Couple'' (play), a 1965 stage play by Neil Simon

** ''The Odd Couple'' (film), a 1968 film based on the play

*** ''The Odd Couple'' (1970 TV series), a 1970–1975 televisi ...

'', a play by Neil Simon, debuted on Broadway at the Plymouth Theatre Plymouth Theatre or Plymouth Theater may refer to:

* Plymouth Theatre (Boston)

* Plymouth Theatre (Worcester)

* Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, New York City, formerly the Plymouth Theatre

* H Street Playhouse

The H Street Playhouse was a black box ...

, with Walter Matthau

Walter Matthau (; born Walter John Matthow; October 1, 1920 – July 1, 2000) was an American actor, comedian and film director.

He is best known for his film roles in '' A Face in the Crowd'' (1957), ''King Creole'' (1958) and as a coach of a ...

as Oscar Madison and Art Carney as Felix Ungar. Simon would say later that he based the characters on a situation involving his meticulously tidy older brother, writer Danny Simon

Daniel Simon (December 18, 1918, The Bronx, New York – July 26, 2005, Portland, Oregon) was an American television writer and comedy teacher.

Biography

The older brother of playwright Neil Simon, the two siblings wrote comedy together until ...

, who had had to share an apartment with a disheveled theatrical agent and friend, Roy Gerber, following a divorce. The characters of Oscar and Felix would be reimagined in many versions over the next half-century, including two films (with Matthau and Jack Lemmon

John Uhler Lemmon III (February 8, 1925 – June 27, 2001) was an American actor. Considered equally proficient in both dramatic and comic roles, Lemmon was known for his anxious, middle-class everyman screen persona in dramedy pictures, leadin ...

); a 1970s television show (Jack Klugman

Jack Klugman (April 27, 1922 – December 24, 2012) was an American actor of stage, film, and television.

He began his career in 1950 and started television and film work with roles in ''12 Angry Men'' (1957) and '' Cry Terror!'' (1958). D ...

and Tony Randall

Anthony Leonard Randall (born Aryeh Leonard Rosenberg; February 26, 1920 – May 17, 2004) was an American actor. He is best known for portraying the role of Felix Unger in a television adaptation of the 1965 play ''The Odd Couple'' by Neil Sim ...

); and, more recently, a 2015 TV sitcom with Matthew Perry and Thomas Lennon.

*The first drawings were held under Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

's new birthday lottery system of conscription. At the Department of Labor and National Service in Melbourne, Representative Dan Mackinnon

Ewen Daniel Mackinnon (11 February 1903 – 7 June 1983) was an Australian politician. The son of state MLA Donald Mackinnon, he was born in Melbourne and educated at Geelong Grammar School and then attended Oxford University. He returned to Au ...

drew marbles from a barrel as part of the "birthday ballot" until there were sufficient eligible men to meet the quota of 4,200 draftees. The results were kept secret, with a policy that "Although pressmen will be able to watch and photograph the drawing of the first marble they will not be allowed to see or photograph the number on it." Young men whose birthdays were selected were "balloted out" and would be notified within four weeks.

*In France, the cabinet of President Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

approved a bill to remove many of the restrictions placed on married women, in what Information Minister Alain Peyrefitte

Alain Peyrefitte (; 26 August 1925 – 27 November 1999) was a French scholar and politician. He was a confidant of Charles de Gaulle and had a long career in public service, serving as a diplomat in Germany and Poland. Peyrefitte is remembered ...

described as "a veritable emancipation of the wife". The new bill, drafted by Justice Minister Jean Foyer

Jean Foyer (21 April 1921, Contigné, Maine-et-Loire – 3 October 2008, Paris) was a French politician and minister. He studied law and became a law professor at the university. He wrote several books about French Civil law.

Political care ...

, was expected to be passed by the French parliament. At the time, married women were not allowed to take a job, open a bank account, or spend their own earnings without their husband's consent.

* Robert Komer, President Johnson's adviser on the Middle East, met with Israel's Prime Minister Levi Eshkol in Tel Aviv, seeking to get the Israelis to agree to bring their nuclear program under the jurisdiction of the International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 1957 ...

. However, the only concession that Eshkol would agree to in the "Memorandum of Understanding" signed between the two nations was a reaffirmation that "Israel will not be the first to introduce nuclear weapons into the Arab-Israeli area."

*The MacDonald House bombing, Indonesia's only successful attack on the Malay peninsula during the '' Konfrontasi'' war over Java, killed three people and injured 33 others in Singapore. The two young Indonesian Marine Corps operatives who had carried out the attack, Harun Said and Osman Mohamed Ali, would be executed by hanging in 1968.

*The United Kingdom and Norway signed an agreement on the maritime boundary between the two nations in the North Sea. Rather than the former line based on the Norwegian trench, the British and Norwegian governments agreed that the median line of points equidistant from both mainland coasts would serve as the boundary.

*The engagement was announced between Princess Margriet of the Netherlands and Pieter van Vollenhoven, who would become the first commoner and the first Dutchman to marry into the Dutch royal family.

* Goldie, a London Zoo

London Zoo, also known as ZSL London Zoo or London Zoological Gardens is the world's oldest scientific zoo. It was opened in London on 27 April 1828, and was originally intended to be used as a collection for science, scientific study. In 1831 o ...

golden eagle, was recaptured 12 days after her escape.

*Born: Rod Woodson

Roderick Kevin Woodson (born March 10, 1965) is an American former professional football defensive back in the National Football League (NFL) for 17 seasons. He is currently the Head Coach of the XFL's Vegas Vipers. Woodson was drafted in the ...

, American NFL Hall of Fame cornerback; in Fort Wayne, Indiana

*Died:

** José "El Piloto" Castro Veiga, 50, Galician guerrilla and terrorist, was executed in Spain

** Daisy Lampkin, 81, African-American suffragette and civil rights activist

March 11, 1965 (Thursday)

*Operation Market Time

Operation Market Time was the United States Navy, Republic of Vietnam Navy and Royal Australian Navy operation begun in 1965 to stop the flow of troops, war material, and supplies by sea, coast, and rivers, from North Vietnam into parts of Sout ...

, the U.S. Navy complement to the aerial bombing in Operation Rolling Thunder, began off the coast of North and South Vietnam with patrols along the coast, and and offcoast, in order to disrupt North Vietnam's supply lines to the Viet Cong in the south. Unlike the strikes against inland supply lines, the naval operation "proved to be very successful" and cut off the sea supply routes during the war. The first attacks would take place on March 15, as fighter-bombers took off from the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s and to bomb an ammunition dump at Phu Qui.

*The first sit-in

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

at the White House was carried out by 12 young men and women who were staging a civil rights protest. The group arrived at the U.S. presidential residence as part of a tour group but, once inside the central corridor, dropped to the floor, demanded to meet President Johnson, and refused orders to leave. Three went home voluntarily, but the others stayed for 7 hours until they were forcibly removed under police escort.

*Ireland's Prime Minister Seán Lemass dissolved the Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

, the nation's lower house of parliament, and called for new elections, after his Fianna Fáil party lost one seat in a by-election and another to the death of the incumbent. New elections would take place on April 7.

*The city of Inver Grove Heights, Minnesota (with a current population of about 34,000) was created by the merger of Inver Grove and Inver Grove Township.

*Born:

**Jesse Jackson Jr.

Jesse Louis Jackson Jr. (born March 11, 1965) is an American politician. He served as the U.S. representative from from 1995 until his resignation in 2012. A member of the Democratic Party, he is the son of activist and former presidential candi ...

, African-American Congressman for Illinois; in Greenville, South Carolina

Greenville (; locally ) is a city in and the seat of Greenville County, South Carolina, United States. With a population of 70,720 at the 2020 census, it is the sixth-largest city in the state. Greenville is located approximately halfway be ...

** Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen, British designer and television presenter; in Kensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West End of London, West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up b ...

, London

*Died: James Reeb, 38, white Unitarian Universalist minister, two days after receiving severe head injuries received in a beating by white supremacists in Selma, Alabama

Selma is a city in and the county seat of Dallas County, in the Black Belt region of south central Alabama and extending to the west. Located on the banks of the Alabama River, the city has a population of 17,971 as of the 2020 census. About ...

.

March 12

Events Pre-1600

* 538 – Vitiges, king of the Ostrogoths ends his siege of Rome and retreats to Ravenna, leaving the city to the victorious Byzantine general, Belisarius.

* 1088 – Election of Urban II as the 159th Pope of the Cat ...

, 1965 (Friday)

*A reporter for the '' Chicago Daily News'', Margery McElheny, broke the story that former Governor of West Virginia William C. Marland

William Casey Marland (March 26, 1918 – November 26, 1965), a Democrat, was the 24th Governor of West Virginia from 1953 to 1957. He is best known for his early attempts to tax companies that depleted the state's natural resources, especial ...

had been working for the last two and a half years as a taxicab driver in Chicago. Marland, who had served as a state governor ten years earlier, from 1953 to 1957, told reporters at a press conference the next day that he was a recovering alcoholic, and that after being fired from a job as legal counsel for a coal company, he had been working since August 1962 for the Flash Cab Company. Marland, who had been chauffeured while governor, said that he had been driving passengers in an effort "to compose my character, which had fallen apart" as he rehabilitated himself. Marland would receive job offers after his story was told nationwide, including in his own appearance on '' The Jack Paar Show'' on March 26, but would soon be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and would die on November 26.

*A longshoreman named Teddy Deegan was found murdered in Chelsea, Massachusetts

Chelsea is a city in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, Suffolk County, Massachusetts, United States, directly across the Mystic River from the city of Boston. As of the 2020 census, Chelsea had a population of 40,787. With a total area of just 2.46 s ...

. It would be noted later that the murder "would not even qualify as a footnote in Boston mob annals except for one crucial outcome; four men were wrongly imprisoned for decades for his murder, and the case became a cause célèbre and a lesson in the miscarriage of justice." In 1967, Joe Barboza would confess to the murder, but would also accuse Joe Salvati Joe Salvati, wrongfully convicted of a mob-related murder, was ultimately cleared by evidence found by Boston journalist Dan Rea. Sentenced to life in May 1968, he was released in 1997. As a result, the House Committee on Government Reform inve ...

, Peter J. Limone, Louis Greco, and Henry Tameleo of being his accomplices. The four men would be sentenced to life in prison, where Tameleo and Greco would die of old age; Salvati and Limone would spend 30 years behind bars before an enterprising investigative reporter, Dan Rea, would find the evidence that led to their release in 1997.

*The third Test of New Zealand's 1964–65 cricket tour of India opened at the Brabourne Stadium, Bombay.

*Born:

** Steve Finley, American major league outfielder and five time Gold Glove Award

The Rawlings Gold Glove Award, usually referred to as simply the Gold Glove, is the award given annually to the Major League Baseball (MLB) players judged to have exhibited superior individual fielding performances at each fielding position in bo ...

winner; in Union City, Tennessee

** Coleen Nolan, English-Irish singer, television personality, and author; in Blackpool

Blackpool is a seaside resort in Lancashire, England. Located on the North West England, northwest coast of England, it is the main settlement within the Borough of Blackpool, borough also called Blackpool. The town is by the Irish Sea, betw ...

, Lancashire

March 13, 1965 (Saturday)

*A week after a White House meeting with Martin Luther King Jr., President Johnson met with Alabama GovernorGeorge Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist and ...

to discuss the recent events in Selma, and to seek Wallace's support for federal efforts toward African-American voting rights and the right of peaceful assembly for all races. After the meeting, Johnson and Wallace appeared at a press conference, and said, "This March week has brought a very deep and painful challenge to the unending search for American freedom... before it is ended, every resource of this government will be directed to insuring justice for all men of all races in Alabama and everywhere in this land." He described the recent Bloody Sunday in Selma as "an American tragedy". Wallace told the press that he would consider Johnson's recommendations and that he recognized the right of peaceful assembly, "but there are limitations."

*Three weeks after the assassination of Malcolm X, his former bodyguard and potential successor, Leon 4X Ameer, was found dead in his room at the Sherry-Biltmore Hotel in Boston. However, a Boston medical examiner concluded that Ameer, 31, had a history of epilepsy, had "died in a coma while peacefully in bed", and police found "no signs of a struggle and no visible marks of violence on the body".

* Thailand and Malaysia signed an agreement at Songkhla

Songkhla ( th, สงขลา, ), also known as Singgora or Singora (Pattani Malay: ซิงกอรอ), is a city (''thesaban nakhon'') in Songkhla Province of southern Thailand, near the border with Malaysia. Songkhla lies south of Ba ...

, a town on the Thai side of the border of the two nations, to combine operations against guerrilla and terrorist incursions.

*Born: Pamela Andersson

Pamela Kristina Alselind, (, born 13 March 1965) is a Swedish journalist that writes for ''Expressen'' and the magazine ''Amelia''. In 2006 she participated in the SVT show ''På spåret'' along with Tomas Bolme.

Since 1993, she has also been ...

, Swedish journalist that writes for ''Expressen

''Expressen'' (''The Express'') is one of two nationwide evening newspapers in Sweden, the other being '' Aftonbladet''. ''Expressen'' was founded in 1944; its symbol is a wasp and its slogans are "it stings" or "''Expressen'' to your rescue".

...

'' and the magazine ''Amelia''; in Hudiksvall

*Died:

** Corrado Gini, 80, Italian statistician, demographer, and sociologist, best known for developing the Gini coefficient as a measure of income inequality

**Fan Noli

Theofan Stilian Noli, known as Fan Noli (6 January 1882 – 13 March 1965), was an Albanian writer, scholar, diplomat, politician, historian, orator, Archbishop, Metropolitan and founder of the Albanian Orthodox Church and the Albanian Orthodox ...

, 83, founder of the Albanian Orthodox Church

The Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Albania ( sq, Kisha Ortodokse Autoqefale e Shqipërisë), commonly known as the Albanian Orthodox Church or the Orthodox Church of Albania, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church. It declared its autoce ...

and one-time Prime Minister of Albania

March 14

Events Pre-1600

* 1074 – Battle of Mogyoród: Dukes Géza and Ladislaus defeat their cousin Solomon, King of Hungary, forcing him to flee to Hungary's western borderland.

* 1590 – Battle of Ivry: Henry of Navarre and the Huguen ...

, 1965 (Sunday)

* Israel and West Germany established diplomatic relations, one week after an announcement made by German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard

Ludwig Wilhelm Erhard (; 4 February 1897 – 5 May 1977) was a German politician affiliated with the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), and chancellor of West Germany from 1963 until 1966. He is known for leading the West German postwar economic ...

and nearly twenty years after the defeat of Nazi Germany. The next day, the Foreign Ministers of 13 Arab nations, already meeting in Cairo, announced that they would sever relations with the West Germans, and ordered the immediate recall of their ambassadors from Bonn. Four nations ( Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Libya, and Tunisia) later declined to break with West Germany, while six others ( Egypt, Iraq, Yemen, Algeria, Kuwait, and the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

) announced that they planned to establish stronger relations with East Germany.

*Former Soviet Union leader Nikita Khrushchev appeared in public for the first time since he had been fired from his positions as First Secretary of the Communist Party and Prime Minister five months earlier. Khrushchev and his wife, Nina, were casting their votes in Moscow's city elections and arrived at the Moscow University Club, where he was applauded by "a cluster of citizens", who let him come to the head of the line. The election monitor who greeted him handed him a ballot without asking him to show his internal passport, and Khrushchev joked, "How come you're trusting me and letting me vote without identification? You used to be stricter in the past."

* Che Guevara returned to Cuba after a three-month tour of the world and found himself in disfavor with the government. Behind closed doors, "Every one of Che's possible political 'offences' were brought up; his flirtation with Beijing, his digs at the economic systems of the 'fraternal' socialist countries, his polemics against Cuba's Communist old guard and his personal criticism of Castro. Above all, though, there was the withering attack he had made on the Soviet Union in Algeria in February 1965." Guevara would soon resign his government position and even renounce his citizenship, then travel elsewhere in the world to foment revolution.

*Experienced American mountain climbers Daniel Doody and Craig Merrihue fell over to their deaths while climbing a difficult route on Mount Washington

Mount Washington is the highest peak in the Northeastern United States at and the most topographically prominent mountain east of the Mississippi River.

The mountain is notorious for its erratic weather. On the afternoon of April 12, 1934, ...

in preparation for an upcoming trip to the Himalayas. 31-year-old Doody, of North Branford, Connecticut, had served as photographer on the 1963 American expedition to Mount Everest. 31-year-old Merrihue was a physicist at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory

The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) is a research institute of the Smithsonian Institution, concentrating on astrophysical studies including galactic and extragalactic astronomy, cosmology, solar, earth and planetary sciences, the ...

in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

*The first round of municipal elections was held for all the cities in France, with almost 950,000 candidates for 470,000 offices. Runoff elections would be held a week later for any office where a candidate had not received a majority, with the top two vote-getters being on the ballot for the second round.

*Born:

** Kevin Williamson, American TV producer known for creating '' The Vampire Diaries'' and '' Dawson's Creek''; in New Bern, North Carolina

New Bern, formerly called Newbern, is a city in Craven County, North Carolina, United States. As of the 2010 census it had a population of 29,524, which had risen to an estimated 29,994 as of 2019. It is the county seat of Craven County and t ...

** Aamir Khan, Indian Bollywood film actor, director, and producer; in Bombay (now Mumbai)

**Kevin Brown Kevin Brown may refer to:

Entertainment

* Kevin Brown (blues musician) (born 1950), English blues guitarist

* Kevin Brown (author) (born 1960), American journalist and translator

* Kevin Brown (poet) (born 1970), American poet and teacher

* Kevin ...

, American baseball pitcher; in Milledgeville, Georgia

Milledgeville is a city in and the county seat of Baldwin County in the U.S. state of Georgia. It is northeast of Macon and bordered on the east by the Oconee River. The rapid current of the river here made this an attractive location to buil ...

*Died: Stanko Premrl

Stanko Premrl (28 September 1880 – 14 March 1965) was a Slovene Roman Catholic priest, composer, and music teacher. He is best known as the composer of the music for the Slovene national anthem, "Zdravljica".

Premrl was born in the village o ...

, 84, Slovenian Roman Catholic priest and composer of the Slovenian national anthem, the '' Zdravljica''

March 15, 1965 (Monday)

*Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. She was queen ...

ended the ostracism of the Duchess of Windsor, the former Mrs. Wallis Warfield Simpson

Wallis, Duchess of Windsor (born Bessie Wallis Warfield, later Simpson; June 19, 1896 – April 24, 1986), was an American socialite and wife of the former King Edward VIII. Their intention to marry and her status as a divorcée caused ...

, 28 years after her uncle, formerly King Edward VIII, had abdicated the throne in order to marry the divorced American. The decision was occasioned by Edward's illness and surgery, and the meeting took place at his bedside at The London Clinic

The London Clinic is a private healthcare organisation and registered charity based on the corner of Devonshire Place and Marylebone Road in central London. According to HealthInvestor, it is one of England's largest private hospitals.

Histor ...

. "When the 68-year-old duchess curtsied to the queen," UPI would report, "it ended the bitterness in the royal family over the duke's marriage..."

*President Johnson spoke to a joint session of Congress and a nationwide television audience to call for federal legislation that would become the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

. The speech would be remembered for his repeated reference to an African-American song, "We Shall Overcome". "Experience has clearly shown that the existing process of law cannot overcome systematic and ingenious discrimination," Johnson said. "No law that we now have on the books—and I have helped to put three of them there—can ensure the right to vote when local officials are determined to deny it.... What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and State of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome." The bill would be introduced in the Senate on March 17, pass the House, with amendments, on August 3 by a 328–74 vote, and by 79–18 the next day in the Senate, and would be signed into law on August 6, 1965.

*Frank Bossard

Frank Clifton Bossard (13 December 1912 – 19 June 2001) was a British Secret Intelligence Service agent who provided classified documents to the Soviet Union in the 1960s.

Early life

Bossard was born in 1912 to a poor single mother, Ethel ...

, a member of Britain's Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

who had been selling information to the Soviet Union for four years about British military radar and guidance systems, was arrested by Special Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security and Intelligence (information gathering), intelligence in Policing in the United Kingdom, British, Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, ...

agents at the Ivanhoe Hotel in Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest mus ...

. A Soviet defector, code-named "Top Hat", had alerted British intelligence of Bossard's activities, and when he made reservations for the Ivanhoe on March 12, agents trailed him from the Ministry of Aviation to the hotel. When he emerged from his room after a little more than an hour, two officers searched him and found four classified file folders, photography equipment, and exposed rolls of 35 millimeter film. On May 10, he would be sentenced to 21 years in prison.

*South Africa announced a tougher policy of strict racial segregation of the races in sporting events, going beyond the existing rule of separate sections for white and non-white (black and coloured) spectators. Under the new regulations, non-whites were barred from even attending events at venues in predominantly white districts, and whites could not venture into non-white events. Michiel De Wet Nel, the Minister of African Administration, and Pieter Botha, the Minister of Community Development announced the new policy. On average, 25 percent of the spectators at soccer games had been non-white.

*Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-re ...

was re-elected to another term as President of the United Arab Republic (formerly Egypt) and, once again, without opposition in a yes or no vote. The government would report that 6,950,652 out of 6,951,196 voters approved Nasser and that only 65 voted against him. The other 479 ballots were declared void.

*The first TGI Fridays restaurant was founded, by businessman Alan Stillman, who purchased The Good Tavern, located at 63rd Street and First Avenue and named the chain for the expression "Thank God It's Friday".

March 16, 1965 (Tuesday)

*Following the example of Buddhist monks who had performed self-immolation, 82-year oldAlice Herz

Alice Herz (née Straus; May 25, 1882 – March 26, 1965) was a longtime peace activist who was the first person in the United States known to have immolated herself in protest of the escalating Vietnam War, following the example of Buddhist mon ...

stood at the corner of Grand River Avenue and Oakman Boulevard in Detroit, doused herself with two cans of flammable cleaning fluid, then set herself ablaze. Though she was not a "Holocaust survivor" as reported in some accounts, Mrs. Herz had fled Germany in 1933 after the Nazis took power, and left France in 1940 after the German invasion, and she did stay temporarily in an internment camp for refugees before emigrating to the United States in 1942. She left a note that said, "I choose the illuminating death of a Buddhist to protest against a great country trying to wipe out a small country for no reason." Two bystanders smothered the flames, but Mrs. Herz died of her burns 10 days later.

*Mounted deputies of the Montgomery County Montgomery County may refer to:

Australia

* The former name of Montgomery Land District, Tasmania

United Kingdom

* The historic county of Montgomeryshire, Wales, also called County of Montgomery

United States

* Montgomery County, Alabama

* Mon ...

Sheriff's Office violently broke up a civil rights demonstration in Montgomery, Alabama, due to an order given by Circuit Solicitor David Crosland, who apologized later for a "mixup in signals". Riding on horseback and swinging clubs and canes, officers rode into a crowd of about 600 marchers of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segrega ...

; 14 people were injured, and eight of them were hospitalized. A second march of 1,200 people, made after the organizers obtained a parade permit, took place without incident.

March 17, 1965 (Wednesday)

* Frank M. Johnson, Jr., the federal judge for a U.S. District Court in Montgomery, ruled in favor of the right of civil rights protesters to march along U.S. Highway 60 from Selma to Montgomery, and issued an injunction barring Alabama state and county authorities from interfering with the march, and ordered law enforcement agencies (that had recently attacked previous demonstrators) to protect the marchers. *Jackie Robinson

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (January 31, 1919 – October 24, 1972) was an American professional baseball player who became the first African American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) in the modern era. Robinson broke the baseball color line ...

, who in 1947 had become the first African-American Major League Baseball player in modern times, was hired by the ABC television network as the first African-American broadcaster for nationally televised baseball games. Robinson and Leo Durocher, who was in temporary retirement from managing a team, would handle the commentary on 27 games.

*Tanks from the Israeli Defense Force crossed into Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

in the first of four raids to destroy heavy mechanical equipment to be used in diversion of the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

.

*Died: Amos Alonzo Stagg, 102, American college football coach from 1892 to 1932 for the University of Chicago and, after being forced to retire at age 70, for the College of the Pacific

College of the Pacific is the liberal arts core of the University of the Pacific and offers degrees in the natural sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the fine and performing arts. The College houses 18 academic departments in addition to ...

from 1933 to 1946.

March 18, 1965 (Thursday)

*Soviet cosmonautAlexei Leonov

Alexei Arkhipovich Leonov. (30 May 1934 – 11 October 2019) was a Soviet and Russian cosmonaut, Air Force major general, writer, and artist. On 18 March 1965, he became the first person to conduct a spacewalk, exiting the capsule during th ...

left the airlock on his spacecraft '' Voskhod 2'' for 12 minutes and 9 seconds, becoming the first person to "walk in space". The Voshkod ship was launched into orbit at 1:00 p.m. from Baikonur

Baikonur ( kk, Байқоңыр, ; russian: Байконур, translit=Baykonur), formerly known as Leninsk, is a city of republic significance in Kazakhstan on the northern bank of the Syr Darya river. It is currently leased and administered ...

(10:00 a.m. in Moscow and 3:00 a.m. in Washington), and 90 minutes later, on the second orbit, as the ship was passing over the Soviet Union, Leonov exited the two-man capsule while above the Earth, the highest man had ever been into space at that time. Lieutenant Colonel Leonov, secured by a long tether and equipped with oxygen, spent 12 minutes floating free during his time outside, while his crewmate, Colonel Pavel Belyayev, remained at the controls. When Leonov tried to re-enter the safety of the Voshkod airlock, he found that he could not bend enough to get through the narrow opening, as a result of the greater stiffness of the pressurized suit, rather than a "ballooning", since the dimensions remained the same in both a vacuum and normal conditions. After a struggle that sent his pulse rate to 168 and consumed most of his remaining oxygen supply, Leonov reduced the pressure from 400 hPa to 270 and "with the urgent desperation of a doomed man, elbowed and fought his way back in to the safety of the airlock."

* Mick Jagger, Brian Jones, and Bill Wyman

William George Wyman (né Perks; born 24 October 1936) is an English musician who achieved international fame as the bassist for the Rolling Stones from 1962 until 1993. In 1989, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member ...

of The Rolling Stones were cited by police after publicly urinating on the wall of a garage in Stratford, London, following an argument with an attendant who refused to let them use the bathroom because of their long hair. On July 22, the three would be fined five pounds apiece and 15 guineas court costs for "insulting behaviour". The senior court magistrate in West Ham, A.C. Morey, would admonish them: "Just because you have reached extreme heights in your profession, this does not mean you have the right to act like this. You should set a standard of behaviour, a moral pattern for all your very large number of supporters."

*The Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes Between States and Nationals of Other States, also known as "The Washington Convention", was opened for signature in Washington, D.C.; it would take effect on October 14, 1966, after 20 nations had ratified it, and it created the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). The Convention provided a neutral investment arbitration mechanism to resolve disputes between signing nations and foreign investors.

*A general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

began in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with balloting to continue through April 3. The Congolese National Convention party, led by Moise Tshombe, won a plurality of 38 of the 167 seats in the Chamber of Deputies.

*Died:

**King Farouk I of Egypt

Farouk I (; ar, فاروق الأول ''Fārūq al-Awwal''; 11 February 1920 – 18 March 1965) was the tenth ruler of Egypt from the Muhammad Ali dynasty and the penultimate King of Egypt and the Sudan, succeeding his father, Fuad I, in 193 ...

, 45, who had been dethroned and sent into exile in 1952 when his nation became a republic, collapsed from a heart attack during dinner in Rome. Farouk, who weighed and had lived the playboy life on a vast personal fortune estimated at 250 million dollars, was dining at the Ile de France restaurant with an unidentified female companion when he "collapsed face down into the remains of a meal of oysters, roast lamb, pastry and fruit".

**John Larry Kelly Jr.

John Larry Kelly Jr. (December 26, 1923 – March 18, 1965), was an American scientist who worked at Bell Labs. From a "system he'd developed to analyze information transmitted over networks," from Claude Shannon's earlier work on information t ...

, 41, American scientist best known for his 1956 work in creating the ''Kelly criterion