Louis Philippe I d'Orléans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Louis Philippe (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850) was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, and the penultimate monarch of France.

As Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres, he distinguished himself commanding troops during the Revolutionary Wars and was promoted to lieutenant general by the age of nineteen, but he broke with the

The reaction in Paris to Louis Philippe's involvement in Dumouriez's treason inevitably resulted in misfortunes for the Orléans family. Philippe Égalité spoke in the National Convention, condemning his son for his actions, asserting that he would not spare his son, much akin to the Roman consul Lucius Junius Brutus, Brutus and his sons. However, letters from Louis Philippe to his father were discovered in transit and were read out to the National Convention, Convention. Philippe Égalité was then put under continuous surveillance. Shortly thereafter, the Girondists moved to arrest him and the two younger brothers of Louis Philippe, Louis-Charles, Count of Beaujolais, Louis-Charles and Antoine Philippe, Duke of Montpensier, Antoine Philippe; the latter had been serving in the Army of Italy (France), Army of Italy. The three were interned in Fort Saint-Jean (Marseille), Fort Saint-Jean in Marseille.

Meanwhile, Louis Philippe was forced to live in the shadows, avoiding both pro-Republican revolutionaries and Legitimist French ''French emigration (1789–1815), émigré'' centres in various parts of Europe and also in the Austrian army. He first moved to Switzerland under an assumed name, and met up with the Countess of Genlis and his sister Louise Marie Adélaïde Eugénie d'Orléans, Adélaïde at Schaffhausen. From there they went to Zürich, where the Swiss authorities decreed that to protect Swiss neutrality, Louis Philippe would have to leave the city. They went to Zug, where Louis Philippe was discovered by a group of ''émigrés''.

It became quite apparent that for the women to settle peacefully anywhere, they would have to separate from Louis Philippe. He then left with his faithful valet Baudouin for the heights of the Alps, and then to Basel, where he sold all but one of his horses. Now moving from town to town throughout Switzerland, he and Baudouin found themselves very much exposed to all the distresses of extended travelling. They were refused entry to a monastery by monks who believed them to be young vagabonds. Another time, he woke up after spending a night in a barn to find himself at the far end of a musket, confronted by a man attempting to keep away thieves.

Throughout this period, he never stayed in one place more than 48 hours. Finally, in October 1793, Louis Philippe was appointed a teacher of geography, history, mathematics and modern languages, at a boys' boarding school. The school, owned by a Monsieur Jost, was in Reichenau, Switzerland, Reichenau, a village on the upper Rhine in the then independent Three Leagues, Grisons league state, now part of Switzerland. His salary was 1,400 francs and he taught under the name ''Monsieur Chabos''. He had been at the school for a month when he heard the news from Paris: his father had been guillotined on 6 November 1793 after a trial before the Revolutionary Tribunal.

The reaction in Paris to Louis Philippe's involvement in Dumouriez's treason inevitably resulted in misfortunes for the Orléans family. Philippe Égalité spoke in the National Convention, condemning his son for his actions, asserting that he would not spare his son, much akin to the Roman consul Lucius Junius Brutus, Brutus and his sons. However, letters from Louis Philippe to his father were discovered in transit and were read out to the National Convention, Convention. Philippe Égalité was then put under continuous surveillance. Shortly thereafter, the Girondists moved to arrest him and the two younger brothers of Louis Philippe, Louis-Charles, Count of Beaujolais, Louis-Charles and Antoine Philippe, Duke of Montpensier, Antoine Philippe; the latter had been serving in the Army of Italy (France), Army of Italy. The three were interned in Fort Saint-Jean (Marseille), Fort Saint-Jean in Marseille.

Meanwhile, Louis Philippe was forced to live in the shadows, avoiding both pro-Republican revolutionaries and Legitimist French ''French emigration (1789–1815), émigré'' centres in various parts of Europe and also in the Austrian army. He first moved to Switzerland under an assumed name, and met up with the Countess of Genlis and his sister Louise Marie Adélaïde Eugénie d'Orléans, Adélaïde at Schaffhausen. From there they went to Zürich, where the Swiss authorities decreed that to protect Swiss neutrality, Louis Philippe would have to leave the city. They went to Zug, where Louis Philippe was discovered by a group of ''émigrés''.

It became quite apparent that for the women to settle peacefully anywhere, they would have to separate from Louis Philippe. He then left with his faithful valet Baudouin for the heights of the Alps, and then to Basel, where he sold all but one of his horses. Now moving from town to town throughout Switzerland, he and Baudouin found themselves very much exposed to all the distresses of extended travelling. They were refused entry to a monastery by monks who believed them to be young vagabonds. Another time, he woke up after spending a night in a barn to find himself at the far end of a musket, confronted by a man attempting to keep away thieves.

Throughout this period, he never stayed in one place more than 48 hours. Finally, in October 1793, Louis Philippe was appointed a teacher of geography, history, mathematics and modern languages, at a boys' boarding school. The school, owned by a Monsieur Jost, was in Reichenau, Switzerland, Reichenau, a village on the upper Rhine in the then independent Three Leagues, Grisons league state, now part of Switzerland. His salary was 1,400 francs and he taught under the name ''Monsieur Chabos''. He had been at the school for a month when he heard the news from Paris: his father had been guillotined on 6 November 1793 after a trial before the Revolutionary Tribunal.

In 1808, Louis Philippe proposed to Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom, Princess Elizabeth, daughter of King George III of the United Kingdom. His Catholicism and the opposition of her mother Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen Charlotte meant the Princess reluctantly declined the offer.

In 1809, Louis Philippe married Princess Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily, daughter of King Ferdinand IV of Naples and Maria Carolina of Austria. The ceremony was celebrated in Palermo 25 November 1809. The marriage was controversial because her mother's younger sister was Queen Marie Antoinette, and Louis Philippe's father was considered to have a role in Marie Antoinette's execution. The Queen of Naples was opposed to the match for this reason. She had been very close to her sister and devastated by her execution, but she had given her consent after Louis Philippe had convinced her that he was determined to compensate for the mistakes of his father, and after having agreed to answer all her questions regarding his father.Dyson. C.C, ''The Life of Marie Amelie Last Queen of the French, 1782–1866'', BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008.

In 1808, Louis Philippe proposed to Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom, Princess Elizabeth, daughter of King George III of the United Kingdom. His Catholicism and the opposition of her mother Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen Charlotte meant the Princess reluctantly declined the offer.

In 1809, Louis Philippe married Princess Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily, daughter of King Ferdinand IV of Naples and Maria Carolina of Austria. The ceremony was celebrated in Palermo 25 November 1809. The marriage was controversial because her mother's younger sister was Queen Marie Antoinette, and Louis Philippe's father was considered to have a role in Marie Antoinette's execution. The Queen of Naples was opposed to the match for this reason. She had been very close to her sister and devastated by her execution, but she had given her consent after Louis Philippe had convinced her that he was determined to compensate for the mistakes of his father, and after having agreed to answer all her questions regarding his father.Dyson. C.C, ''The Life of Marie Amelie Last Queen of the French, 1782–1866'', BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008.

In 1830, the July Revolution overthrew Charles X, who abdicated in favour of his 10-year-old grandson, Henri, comte de Chambord, Henri, Duke of Bordeaux. Charles X named Louis Philippe ''Lieutenant général du royaume'', and charged him to announce his desire to have his grandson succeed him to the popularly elected Chamber of Deputies of France, Chamber of Deputies. Louis-Philippe did not do this, in order to increase his own chances of succession. As a consequence, because the chamber was aware of his liberal policies and of his popularity with the masses, they proclaimed Louis-Philippe as the new French king, displacing the senior branch of the

In 1830, the July Revolution overthrew Charles X, who abdicated in favour of his 10-year-old grandson, Henri, comte de Chambord, Henri, Duke of Bordeaux. Charles X named Louis Philippe ''Lieutenant général du royaume'', and charged him to announce his desire to have his grandson succeed him to the popularly elected Chamber of Deputies of France, Chamber of Deputies. Louis-Philippe did not do this, in order to increase his own chances of succession. As a consequence, because the chamber was aware of his liberal policies and of his popularity with the masses, they proclaimed Louis-Philippe as the new French king, displacing the senior branch of the

Louis Philippe ruled in an unpretentious fashion, avoiding the pomp and lavish spending of his predecessors. Despite this outward appearance of simplicity, his support came from the wealthy ''bourgeoisie''. At first, he was much loved and called the "Citizen King" and the "bourgeois monarch", but his popularity suffered as his government was perceived as increasingly conservative and monarchical, despite his decision to have retour des cendres, Napoleon's remains returned to France. Under his management, the conditions of the working classes deteriorated, and the income gap widened considerably. In foreign affairs it was a quiet period, with friendship with Great Britain.

An industrial and agricultural depression in 1846 led to the Revolutions of 1848 in France, 1848 Revolutions, and Louis Philippe's abdication.

The dissonance between his positive early reputation and his late unpopularity was epitomized by Victor Hugo in ''Les Misérables'' as an oxymoron describing his reign as "Prince Equality", in which Hugo states:

Louis Philippe ruled in an unpretentious fashion, avoiding the pomp and lavish spending of his predecessors. Despite this outward appearance of simplicity, his support came from the wealthy ''bourgeoisie''. At first, he was much loved and called the "Citizen King" and the "bourgeois monarch", but his popularity suffered as his government was perceived as increasingly conservative and monarchical, despite his decision to have retour des cendres, Napoleon's remains returned to France. Under his management, the conditions of the working classes deteriorated, and the income gap widened considerably. In foreign affairs it was a quiet period, with friendship with Great Britain.

An industrial and agricultural depression in 1846 led to the Revolutions of 1848 in France, 1848 Revolutions, and Louis Philippe's abdication.

The dissonance between his positive early reputation and his late unpopularity was epitomized by Victor Hugo in ''Les Misérables'' as an oxymoron describing his reign as "Prince Equality", in which Hugo states:

Louis Philippe survived seven assassination attempts.

On 28 July 1835, Louis Philippe survived an assassination attempt by Giuseppe Mario Fieschi and two other conspirators in Paris. During the king's annual review of the Paris National Guard commemorating the revolution, Louis Philippe was passing along the Boulevard du Temple, which connected Place de la République to the Bastille, accompanied by three of his sons, the Ferdinand Philippe, Duke of Orléans, Duke of Orleans, the Prince Louis, Duke of Nemours, Duke of Nemours, and the François d'Orléans, Prince of Joinville, Prince de Joinville, and numerous staff.

Fieschi, a Corsican ex-soldier, attacked the procession with a weapon he built himself, a volley gun that later became known as the Infernal machine (weapon), ''Machine infernale''. This consisted of 25 gun barrels fastened to a wooden frame that could be fired simultaneously. The device was fired from the third level of n° 50 Boulevard du Temple (a commemorative plaque has since been engraved there), which had been rented by Fieschi.

A ball only grazed the King's forehead. Eighteen people were killed, including Lieutenant Colonel of the 8th Legion together with eight other officers, Édouard Adolphe Casimir Joseph Mortier, Marshal Mortier, duc de Trévise, and Colonel Raffet, General Girard, Captain Villate, General La Chasse de Vérigny, a woman, a 14-year-old girl and two men. A further 22 people were injured. The King and the princes escaped essentially unharmed. Horace Vernet, the King's painter, was ordered to make a drawing of the event.

Several of the gun barrels of Fieschi's weapon burst when it was fired; he was badly injured and was quickly captured. He was executed by guillotine together with his two co-conspirators the following year.

Louis Philippe survived seven assassination attempts.

On 28 July 1835, Louis Philippe survived an assassination attempt by Giuseppe Mario Fieschi and two other conspirators in Paris. During the king's annual review of the Paris National Guard commemorating the revolution, Louis Philippe was passing along the Boulevard du Temple, which connected Place de la République to the Bastille, accompanied by three of his sons, the Ferdinand Philippe, Duke of Orléans, Duke of Orleans, the Prince Louis, Duke of Nemours, Duke of Nemours, and the François d'Orléans, Prince of Joinville, Prince de Joinville, and numerous staff.

Fieschi, a Corsican ex-soldier, attacked the procession with a weapon he built himself, a volley gun that later became known as the Infernal machine (weapon), ''Machine infernale''. This consisted of 25 gun barrels fastened to a wooden frame that could be fired simultaneously. The device was fired from the third level of n° 50 Boulevard du Temple (a commemorative plaque has since been engraved there), which had been rented by Fieschi.

A ball only grazed the King's forehead. Eighteen people were killed, including Lieutenant Colonel of the 8th Legion together with eight other officers, Édouard Adolphe Casimir Joseph Mortier, Marshal Mortier, duc de Trévise, and Colonel Raffet, General Girard, Captain Villate, General La Chasse de Vérigny, a woman, a 14-year-old girl and two men. A further 22 people were injured. The King and the princes escaped essentially unharmed. Horace Vernet, the King's painter, was ordered to make a drawing of the event.

Several of the gun barrels of Fieschi's weapon burst when it was fired; he was badly injured and was quickly captured. He was executed by guillotine together with his two co-conspirators the following year.

On 24 February 1848, during the Revolutions of 1848 in France, February 1848 Revolution, King Louis Philippe abdicated in favour of his nine-year-old grandson, Philippe, comte de Paris. Fearful of what had happened to the deposed Louis XVI, Louis Philippe quickly left Paris under disguise. He rode in an ordinary cab under the name of "Mr. Smith". He fled to England and spent his final years incognito as the 'Comte de Neuilly'.

The National Assembly of France initially planned to accept young Philippe as king, but the strong current of public opinion rejected that. On 26 February, the French Second Republic, Second Republic was proclaimed. Louis Napoléon Bonaparte was elected president on 10 December 1848; on 2 December 1851, he declared himself president for life and then Emperor Napoleon III of France, Napoleon III in 1852.

Louis Philippe and his family remained in exile in Great Britain in Claremont (country house), Claremont, Surrey, though a plaque on Angel Hill, Bury St Edmunds, claims that he spent some time there, possibly due to a friendship with the Marquess of Bristol, who lived nearby at Ickworth House. The royal couple spent some time by the sea at St. LeonardsRoyal Victoria Hotel - Historical Hastings Wiki

On 24 February 1848, during the Revolutions of 1848 in France, February 1848 Revolution, King Louis Philippe abdicated in favour of his nine-year-old grandson, Philippe, comte de Paris. Fearful of what had happened to the deposed Louis XVI, Louis Philippe quickly left Paris under disguise. He rode in an ordinary cab under the name of "Mr. Smith". He fled to England and spent his final years incognito as the 'Comte de Neuilly'.

The National Assembly of France initially planned to accept young Philippe as king, but the strong current of public opinion rejected that. On 26 February, the French Second Republic, Second Republic was proclaimed. Louis Napoléon Bonaparte was elected president on 10 December 1848; on 2 December 1851, he declared himself president for life and then Emperor Napoleon III of France, Napoleon III in 1852.

Louis Philippe and his family remained in exile in Great Britain in Claremont (country house), Claremont, Surrey, though a plaque on Angel Hill, Bury St Edmunds, claims that he spent some time there, possibly due to a friendship with the Marquess of Bristol, who lived nearby at Ickworth House. The royal couple spent some time by the sea at St. LeonardsRoyal Victoria Hotel - Historical Hastings Wiki

accessdate: 22 May 2020 and later at the Marquess's home in Brighton. Louis Philippe died at Claremont on 26 August 1850. He was first buried at St. Charles Borromeo Chapel in Weybridge, Surrey. In 1876, his remains and those of his wife were taken to France and buried at the ''Chapelle royale de Dreux'', the Orléans family necropolis his mother had built in 1816, and which he had enlarged and embellished after her death.

Militaire Willems-Orde: Bourbon, Louis Phillip prince de

' (in Dutch) * : Order of the Golden Fleece, Knight of the Golden Fleece, ''21 February 1834'' * Beylik of Tunis: Husainid Family Order * : ** Order of Saint Januarius, Knight of St. Januarius ** Order of Saint Ferdinand and of Merit, Grand Cross of St. Ferdinand and Merit * : Order of the Garter, Stranger Knight of the Garter, ''11 October 1844''

File:Royal Standard of Louis-Philippe I of France (1830–1848).svg, Standard of Louis Philippe I

File:Coat of Arms of the July Monarchy (1831-48).svg, Coat of arms of Louis Philippe I

Akaroa, Port Louis-Philippe (Akaroa), the oldest French colonial empire, French colony in the South Pacific Ocean, South Pacific and the oldest town in the Canterbury Region of the New Zealand's South Island was named in honour of Louis Philippe who reigned as King of the French at the time the colony was established on 18 August 1840. Louis Philippe had been instrumental in patronage, supporting the settlement project. The Nanto-Bordelaise Company, company responsible for the endeavour received Louis Philippe's signature on 11 December 1839 as well as his permission to carry out the voyage in line with his policy of supporting colonial expansion and the construction of a French colonial empire#Second French colonial empire (after 1830), second empire which had first commenced under him in French rule in Algeria, Algeria around a decade earlier. The British Lieutenant-Governor Captain William Hobson subsequently went on to claim sovereignty over Port Louis-Philippe.

As a further honorific gesture to Louis Philippe and his Orléanist branch of the Bourbons, the ship on which the settlers sailed to found the eponymous colony of Port Louis-Philippe was named the Comte de Paris (ship), ''Comte de Paris'' after Louis Philippe's beloved infant grandson, Prince Philippe, Count of Paris, Prince Philippe d'Orléans, Count of Paris who was born on 24 August 1838.

Akaroa, Port Louis-Philippe (Akaroa), the oldest French colonial empire, French colony in the South Pacific Ocean, South Pacific and the oldest town in the Canterbury Region of the New Zealand's South Island was named in honour of Louis Philippe who reigned as King of the French at the time the colony was established on 18 August 1840. Louis Philippe had been instrumental in patronage, supporting the settlement project. The Nanto-Bordelaise Company, company responsible for the endeavour received Louis Philippe's signature on 11 December 1839 as well as his permission to carry out the voyage in line with his policy of supporting colonial expansion and the construction of a French colonial empire#Second French colonial empire (after 1830), second empire which had first commenced under him in French rule in Algeria, Algeria around a decade earlier. The British Lieutenant-Governor Captain William Hobson subsequently went on to claim sovereignty over Port Louis-Philippe.

As a further honorific gesture to Louis Philippe and his Orléanist branch of the Bourbons, the ship on which the settlers sailed to found the eponymous colony of Port Louis-Philippe was named the Comte de Paris (ship), ''Comte de Paris'' after Louis Philippe's beloved infant grandson, Prince Philippe, Count of Paris, Prince Philippe d'Orléans, Count of Paris who was born on 24 August 1838.

online

* Beik, Paul. ''Louis Philippe and the July Monarchy'' (1965) * Collingham, H.A.C. ''The July Monarchy: A Political History of France, 1830–1848'' (Longman, 1988) * Howarth, T.E.B. ''Citizen-King: The Life of Louis Philippe, King of the French'' (1962). * Jardin, Andre, and Andre-Jean Tudesq. ''Restoration and Reaction 1815–1848'' (The Cambridge History of Modern France) (1988) * Lucas-Dubreton, J. ''The Restoration and the July Monarchy'' (1929) * Newman, Edgar Leon, and Robert Lawrence Simpson. ''Historical Dictionary of France from the 1815 Restoration to the Second Empire'' (Greenwood Press, 1987

online edition

* Porch, Douglas. "The French Army Law of 1832." ''Historical Journal'' 14, no. 4 (1971): 751–69

online

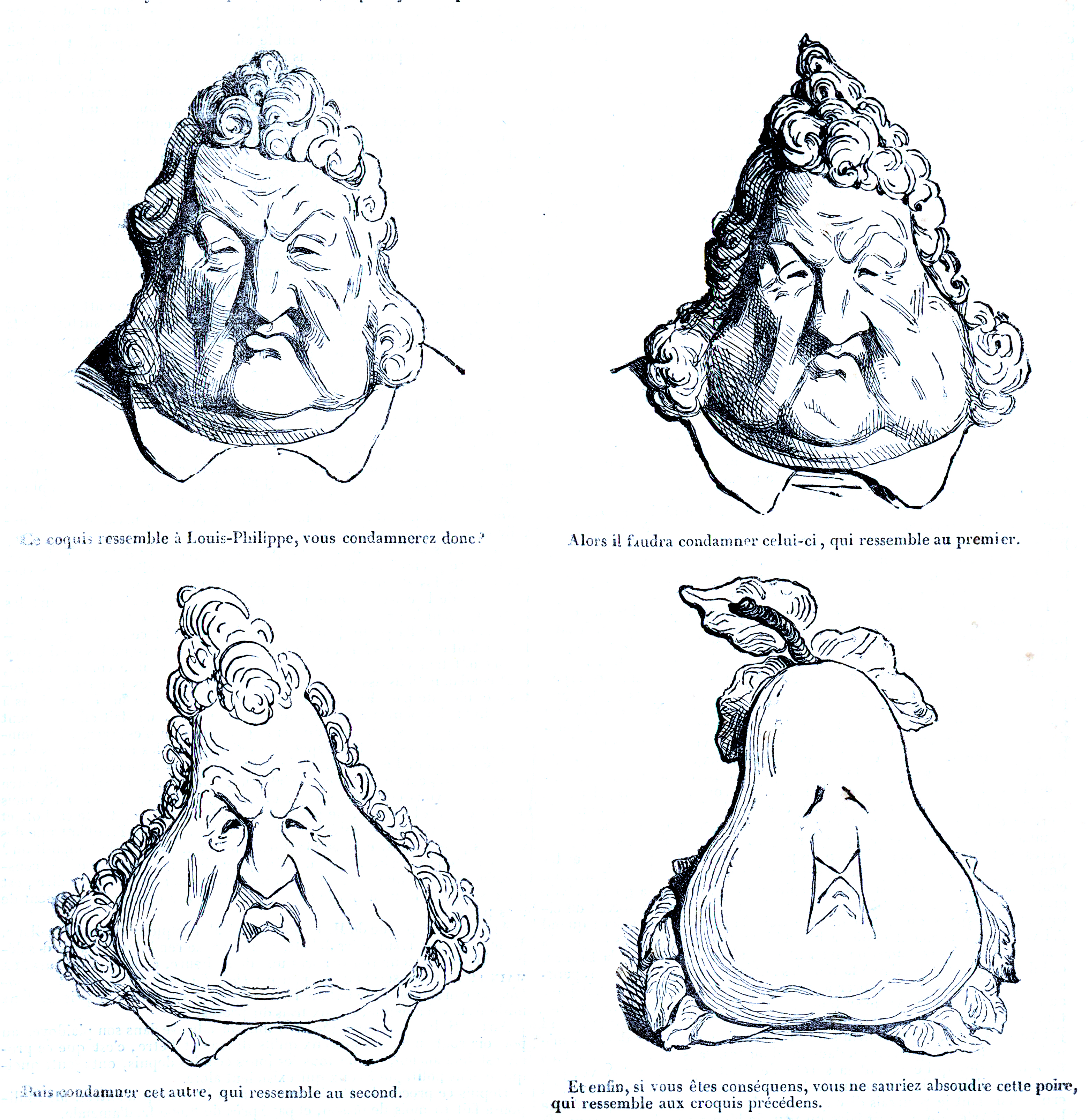

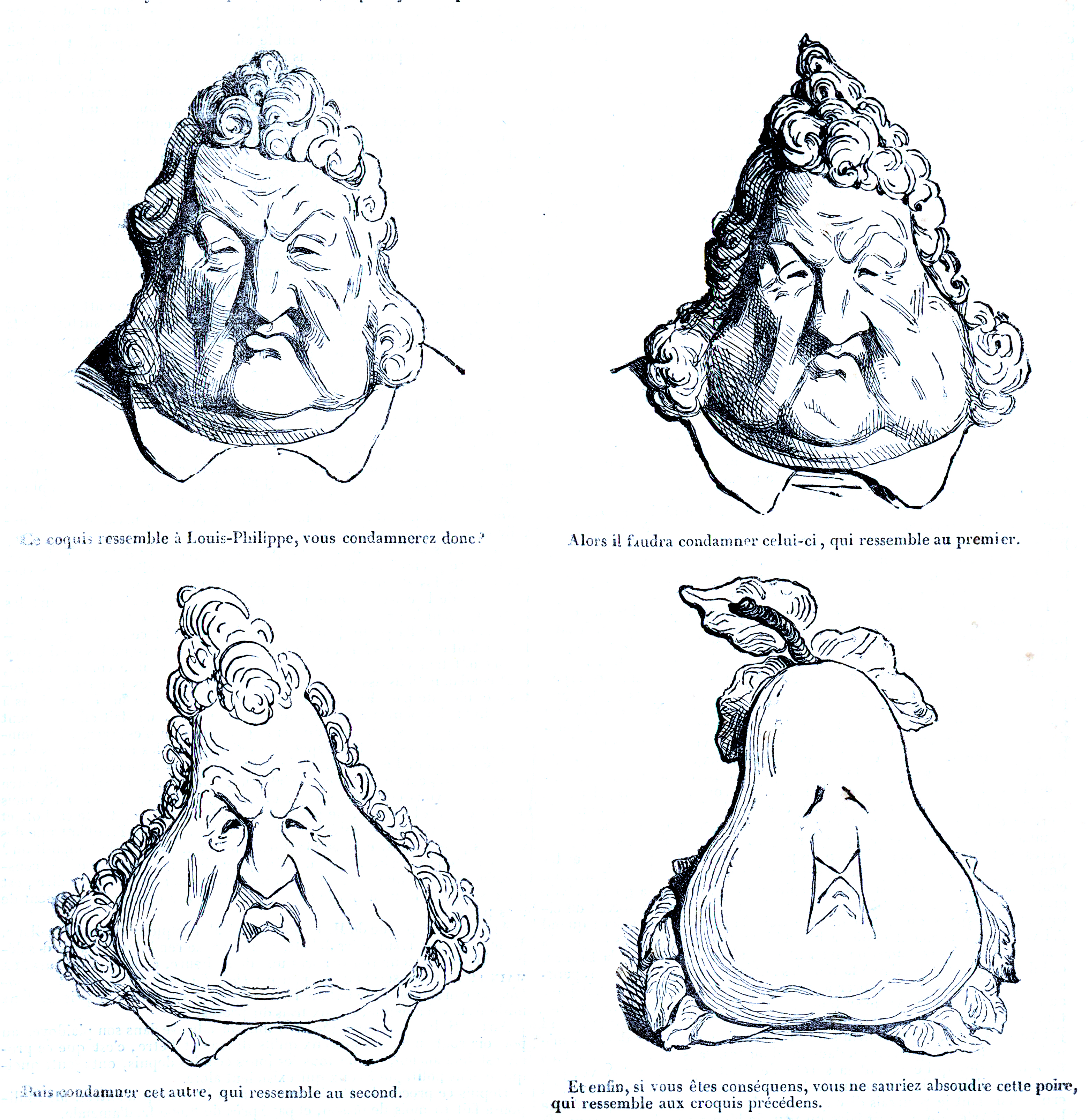

Caricatures of Louis Philippe and others, published in ''La Caricature (1830–1843), La Caricature'' 1830–1835 , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Louis Philippe I Louis Philippe I, 1773 births 1850 deaths 19th-century monarchs of France 19th-century Princes of Andorra Nobility from Paris French Roman Catholics Kings of France House of Orléans Dukes of Enghien Dukes of Montpensier Dukes of Chartres Burials at the Chapelle royale de Dreux People of the July Monarchy, People of the Belgian Revolution People of the French Revolution French people of the Revolutions of 1848 French expatriates in England Monarchs who abdicated French Republican military leaders of the French Revolutionary Wars Names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe French generals 18th-century peers of France Members of the Chamber of Peers of the Bourbon Restoration Princes of Andorra Princes of France (Bourbon) Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Extra Knights Companion of the Garter Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of William Orléanist pretenders to the French throne Royal reburials

Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

over its decision to execute King Louis XVI. He fled to Switzerland in 1793 after being connected with a plot to restore France's monarchy. His father Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans

Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (Louis Philippe Joseph; 13 April 17476 November 1793), was a major French noble who supported the French Revolution.

Louis Philippe II was born at the Château de Saint-Cloud to Louis Philippe I, Duke of Char ...

(Philippe Égalité) fell under suspicion and was executed during the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public executions took place in response to revolutionary fervour, ...

.

Louis Philippe remained in exile for 21 years until the Bourbon Restoration Bourbon Restoration may refer to:

France under the House of Bourbon:

* Bourbon Restoration in France (1814, after the French revolution and Napoleonic era, until 1830; interrupted by the Hundred Days in 1815)

Spain under the Spanish Bourbons:

* ...

. He was proclaimed king in 1830 after his cousin Charles X was forced to abdicate by the July Revolution (and because of the Spanish renounciation). The reign of Louis Philippe is known as the July Monarchy and was dominated by wealthy industrialists and bankers. He followed conservative policies, especially under the influence of French statesman François Guizot

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (; 4 October 1787 – 12 September 1874) was a French historian, orator, and statesman. Guizot was a dominant figure in French politics prior to the Revolution of 1848.

A conservative liberal who opposed the a ...

during the period 1840–1848. He also promoted friendship with Great Britain and sponsored colonial expansion, notably the French conquest of Algeria

The French invasion of Algeria (; ) took place between 1830 and 1903. In 1827, an argument between Hussein Dey, the ruler of the Deylik of Algiers, and the French consul escalated into a blockade, following which the July Monarchy of France inva ...

. His popularity faded as economic conditions in France deteriorated in 1847, and he was forced to abdicate after the outbreak of the French Revolution of 1848

The French Revolution of 1848 (french: Révolution française de 1848), also known as the February Revolution (), was a brief period of civil unrest in France, in February 1848, that led to the collapse of the July Monarchy and the foundation ...

.

He lived for the remainder of his life in exile in the United Kingdom. His supporters were known as Orléanists. The Legitimists supported the main line of the House of Bourbon, and the Bonapartists supported the Bonaparte family

Italian and Corsican: ''Casa di Buonaparte'', native_name_lang=French, coat of arms=Arms of the French Empire3.svg, caption=Coat of arms assumed by Emperor Napoleon I, image_size=150px, alt=Coat of Arms of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French, typ ...

, which includes Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and Napoleon III.

Among his grandchildren were the monarchs Leopold II of Belgium, Empress Carlota of Mexico, Ferdinand I of Bulgaria, and Queen Mercedes of Spain .

Before the Revolution (1773–1789)

Early life

Louis Philippe was born in the Palais Royal, the residence of the Orléans family in Paris, to Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres (Duke of Orléans

Duke of Orléans (french: Duc d'Orléans) was a French royal title usually granted by the King of France to one of his close relatives (usually a younger brother or son), or otherwise inherited through the male line. First created in 1344 by King ...

, upon the death of his father Louis Philippe I), and Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon. As a member of the reigning House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanis ...

, he was a Prince of the Blood, which entitled him the use of the style " Serene Highness". His mother was an extremely wealthy heiress who was descended from Louis XIV of France through a legitimized line.

Louis Philippe was the eldest of three sons and a daughter, a family that was to have erratic fortunes from the beginning of the French Revolution to the Bourbon Restoration Bourbon Restoration may refer to:

France under the House of Bourbon:

* Bourbon Restoration in France (1814, after the French revolution and Napoleonic era, until 1830; interrupted by the Hundred Days in 1815)

Spain under the Spanish Bourbons:

* ...

.

The elder branch of the House of Bourbon, to which the kings of France belonged, deeply distrusted the intentions of the cadet branch, which would succeed to the throne of France should the senior branch die out. Louis Philippe's father was exiled from the royal court, and the Orléans confined themselves to studies of the literature and sciences emerging from the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

.

Education

Louis Philippe was tutored by the Countess of Genlis, beginning in 1782. She instilled in him a fondness for liberal thought; it is probably during this period that Louis Philippe picked up his slightly Voltairean brand of Catholicism. When Louis Philippe's grandfather died in 1785, his father succeeded him as Duke of Orléans and Louis Philippe succeeded his father as Duke of Chartres. In 1788, with the Revolution looming, the young Louis Philippe showed his liberal sympathies when he helped break down the door of a prison cell inMont Saint-Michel

Mont-Saint-Michel (; Norman: ''Mont Saint Miché''; ) is a tidal island and mainland commune in Normandy, France.

The island lies approximately off the country's north-western coast, at the mouth of the Couesnon River near Avranches and is ...

, during a visit there with the Countess of Genlis. From October 1788 to October 1789, the ''Palais Royal'' was a meeting-place for the revolutionaries.

Revolution (1789–1793)

Louis Philippe grew up in a period that changed Europe as a whole and, following his father's strong support for the Revolution, he involved himself completely in those changes. In his diary, he reports that he took the initiative to join theJacobin Club

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

, a move that his father supported.

Military service

In June 1791, Louis Philippe got his first opportunity to become involved in the affairs of France. In 1785, he had been given the hereditary appointment of Colonel of the Chartres Dragoons (renamed 14th Dragoons in 1791). With war imminent in 1791, all proprietary colonels were ordered to join their regiments. Louis Philippe was a model officer, and demonstrated his personal bravery in two famous instances. First, three days after Louis XVI'sflight to Varennes

The royal Flight to Varennes (french: Fuite à Varennes) during the night of 20–21 June 1791 was a significant event in the French Revolution in which King Louis XVI of France, Queen Marie Antoinette, and their immediate family unsuccessfull ...

, a quarrel between two local priests and one of the new ''constitutional'' vicars became heated. A crowd surrounded the inn where the priests were staying, demanding blood. The young colonel broke through the crowd and extricated the two priests, who fled. At a river crossing on the same day, another crowd threatened to harm the priests. Louis Philippe put himself between a peasant armed with a carbine and the priests, saving their lives. The next day, Louis Philippe dived into a river to save a drowning local engineer. For this action, he received a civic crown

The Civic Crown ( la, corona civica) was a military decoration during the Roman Republic and the subsequent Roman Empire, given to Romans who saved the lives of fellow citizens. It was regarded as the second highest decoration to which a citizen ...

from the local municipality. His regiment was moved north to Flanders at the end of 1791 after the 27 August 1791 Declaration of Pillnitz

The Declaration of Pillnitz was a statement of five sentences issued on 27 August 1791 at Pillnitz Castle near Dresden (Saxony) by Frederick William II of Prussia and the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II who was Marie Antoinette's brothe ...

.

Louis Philippe served under his father's crony, Armand Louis de Gontaut

Armand Louis de Gontaut (), duc de Lauzun, later duc de Biron, and usually referred to by historians of the French Revolution simply as Biron (13 April 174731 December 1793) was a French soldier and politician, known for the part he played in t ...

the Duke of Biron, along with several officers who later gained distinction. These included Colonel Berthier and Lieutenant Colonel Alexandre de Beauharnais (husband of the future Empress Joséphine).

After the Kingdom of France declared war on the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

on 20 April 1792, Louis Philippe first participated in what became known as the French Revolutionary Wars within the French-occupied Austrian Netherlands at Boussu, Wallonia, on about 28 April 1792. He was next engaged at Quaregnon, Wallonia, on about 29 April 1792, and then at Quiévrain, Wallonia, near Jemappes

Jemappes (; in older texts also: ''Jemmapes''; wa, Djumape) is a town of Wallonia and a district of the municipality of Mons, located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium.

It was a municipality until the fusion of the Belgian municipalities in 1 ...

, Wallonia, on about 30 April 1792. There he was instrumental in rallying a unit of retreating soldiers after French forces had been victorious at the Battle of Quiévrain (1792) two days earlier on 28 April 1792. The Duke of Biron wrote to War Minister Pierre Marie de Grave, de Grave, praising the young colonel, who was promoted to brigadier general; he commanded a brigade of cavalry in Lückner's Army of the North.

In the Army of the North, Louis Philippe served with four future Marshals of France: Étienne-Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre MacDonald, Macdonald, Édouard Adolphe Casimir Joseph Mortier, Mortier (who would later be killed in an #Assassination attempts, assassination attempt on Louis Philippe), Louis Nicolas Davout, Davout and Nicolas Oudinot, Oudinot. Charles François Dumouriez was appointed to command the Army of the North in August 1792. Louis Philippe commanded a division under him in the Battle of Valmy, Valmy campaign.

At the 20 September 1792 Battle of Valmy, Louis Philippe was ordered to place a battery of artillery on the crest of the hill of Valmy. The battle was apparently inconclusive, but the Austrian-Prussian army, short of supplies, was forced back across the Rhine. Dumouriez praised Louis Philippe's performance in a letter after the battle. Louis Philippe was recalled to Paris to give an account of the Battle at Valmy to the French government. He had a rather trying interview with Georges Danton, Danton, the Minister of Justice, which he later told his children about.

While in Paris, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-general. In October Louis Philippe returned to the Army of the North, where Dumouriez had begun a march into the Austrian Netherlands (now Belgium). Louis Philippe again commanded a division. On 6 November 1792, Dumouriez chose to attack an Austrian force in a strong position on the heights of Cuesmes and Battle of Jemappes, Jemappes to the west of Mons. Louis Philippe's division sustained heavy casualties as it attacked through a wood, and retreated in disorder. Lt. General Louis Philippe rallied a group of units, dubbing them "the battalion of Mons", and pushed forward along with other French units, finally overwhelming the outnumbered Austrians.

Events in Paris undermined his budding military career. The incompetence of Jean-Nicolas Pache, the new Girondist appointee of 3 October 1792, left the Army of the North almost without supplies. Soon thousands of troops were deserting the army. Louis Philippe was alienated by the more radical policies of the French Republic, Republic. After the National Convention decided to put Louis XVI of France, the deposed King to death, Louis Philippe began to consider leaving France. He was dismayed that his own father, known then as ''Philippe Égalité'', voted in favour of the execution.

Louis Philippe was willing to stay to fulfill his duties in the army, but he became implicated in the plot Dumouriez had planned to ally with the Austrians, march his army on Paris, and restore the French Constitution of 1791, Constitution of 1791. Dumouriez had met with Louis Philippe on 22 March 1793 and urged his subordinate to join in the attempt.

With the French government falling into the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public executions took place in response to revolutionary fervour, ...

about the time of the creation of the Revolutionary Tribunal earlier in March 1793, Louis Philippe decided to leave France to save his life. On 4 April, Dumouriez and Louis Philippe left for the Austrian camp. They were intercepted by Lieutenant-Colonel Louis-Nicolas Davout, who had served at Battle of Jemappes, Jemappes with Louis Philippe. As Dumouriez ordered the Colonel back to the camp, some of his soldiers cried out against the General, now declared a traitor by the National Convention. Shots rang out as the two men fled toward the Austrian camp. The next day, Dumouriez again tried to rally soldiers against the convention; however, he found that the artillery had declared itself in favour of the Republic. He and Louis Philippe had not choice but to go into exile.

At the age of nineteen, and already ranked as a Lieutenant General, Louis Philippe left France. He did not return for twenty-one years.

Exile (1793–1815)

The reaction in Paris to Louis Philippe's involvement in Dumouriez's treason inevitably resulted in misfortunes for the Orléans family. Philippe Égalité spoke in the National Convention, condemning his son for his actions, asserting that he would not spare his son, much akin to the Roman consul Lucius Junius Brutus, Brutus and his sons. However, letters from Louis Philippe to his father were discovered in transit and were read out to the National Convention, Convention. Philippe Égalité was then put under continuous surveillance. Shortly thereafter, the Girondists moved to arrest him and the two younger brothers of Louis Philippe, Louis-Charles, Count of Beaujolais, Louis-Charles and Antoine Philippe, Duke of Montpensier, Antoine Philippe; the latter had been serving in the Army of Italy (France), Army of Italy. The three were interned in Fort Saint-Jean (Marseille), Fort Saint-Jean in Marseille.

Meanwhile, Louis Philippe was forced to live in the shadows, avoiding both pro-Republican revolutionaries and Legitimist French ''French emigration (1789–1815), émigré'' centres in various parts of Europe and also in the Austrian army. He first moved to Switzerland under an assumed name, and met up with the Countess of Genlis and his sister Louise Marie Adélaïde Eugénie d'Orléans, Adélaïde at Schaffhausen. From there they went to Zürich, where the Swiss authorities decreed that to protect Swiss neutrality, Louis Philippe would have to leave the city. They went to Zug, where Louis Philippe was discovered by a group of ''émigrés''.

It became quite apparent that for the women to settle peacefully anywhere, they would have to separate from Louis Philippe. He then left with his faithful valet Baudouin for the heights of the Alps, and then to Basel, where he sold all but one of his horses. Now moving from town to town throughout Switzerland, he and Baudouin found themselves very much exposed to all the distresses of extended travelling. They were refused entry to a monastery by monks who believed them to be young vagabonds. Another time, he woke up after spending a night in a barn to find himself at the far end of a musket, confronted by a man attempting to keep away thieves.

Throughout this period, he never stayed in one place more than 48 hours. Finally, in October 1793, Louis Philippe was appointed a teacher of geography, history, mathematics and modern languages, at a boys' boarding school. The school, owned by a Monsieur Jost, was in Reichenau, Switzerland, Reichenau, a village on the upper Rhine in the then independent Three Leagues, Grisons league state, now part of Switzerland. His salary was 1,400 francs and he taught under the name ''Monsieur Chabos''. He had been at the school for a month when he heard the news from Paris: his father had been guillotined on 6 November 1793 after a trial before the Revolutionary Tribunal.

The reaction in Paris to Louis Philippe's involvement in Dumouriez's treason inevitably resulted in misfortunes for the Orléans family. Philippe Égalité spoke in the National Convention, condemning his son for his actions, asserting that he would not spare his son, much akin to the Roman consul Lucius Junius Brutus, Brutus and his sons. However, letters from Louis Philippe to his father were discovered in transit and were read out to the National Convention, Convention. Philippe Égalité was then put under continuous surveillance. Shortly thereafter, the Girondists moved to arrest him and the two younger brothers of Louis Philippe, Louis-Charles, Count of Beaujolais, Louis-Charles and Antoine Philippe, Duke of Montpensier, Antoine Philippe; the latter had been serving in the Army of Italy (France), Army of Italy. The three were interned in Fort Saint-Jean (Marseille), Fort Saint-Jean in Marseille.

Meanwhile, Louis Philippe was forced to live in the shadows, avoiding both pro-Republican revolutionaries and Legitimist French ''French emigration (1789–1815), émigré'' centres in various parts of Europe and also in the Austrian army. He first moved to Switzerland under an assumed name, and met up with the Countess of Genlis and his sister Louise Marie Adélaïde Eugénie d'Orléans, Adélaïde at Schaffhausen. From there they went to Zürich, where the Swiss authorities decreed that to protect Swiss neutrality, Louis Philippe would have to leave the city. They went to Zug, where Louis Philippe was discovered by a group of ''émigrés''.

It became quite apparent that for the women to settle peacefully anywhere, they would have to separate from Louis Philippe. He then left with his faithful valet Baudouin for the heights of the Alps, and then to Basel, where he sold all but one of his horses. Now moving from town to town throughout Switzerland, he and Baudouin found themselves very much exposed to all the distresses of extended travelling. They were refused entry to a monastery by monks who believed them to be young vagabonds. Another time, he woke up after spending a night in a barn to find himself at the far end of a musket, confronted by a man attempting to keep away thieves.

Throughout this period, he never stayed in one place more than 48 hours. Finally, in October 1793, Louis Philippe was appointed a teacher of geography, history, mathematics and modern languages, at a boys' boarding school. The school, owned by a Monsieur Jost, was in Reichenau, Switzerland, Reichenau, a village on the upper Rhine in the then independent Three Leagues, Grisons league state, now part of Switzerland. His salary was 1,400 francs and he taught under the name ''Monsieur Chabos''. He had been at the school for a month when he heard the news from Paris: his father had been guillotined on 6 November 1793 after a trial before the Revolutionary Tribunal.

Travels

After Louis Philippe left Reichenau, he separated the now sixteen-year-old Adélaïde from the Countess of Genlis, who had fallen out with Louis Philippe. Adélaïde went to live with her great-aunt the Maria Fortunata d'Este, Princess of Conti at Fribourg, then to Bavaria and Hungary and, finally, to her mother, who was exiled in Spain. Louis Philippe travelled extensively. He visited Scandinavia in 1795 and then moved on to Finland. For about a year he stayed in Muonio, a remote village in the valley of the Tornio river in Lapland (Finland), Lapland. He lived in the rectory under the name Müller, as a guest of the local Lutheranism, Lutheran vicar. While visiting Muonio, he supposedly fathered a child with Beata Caisa Wahlborn (1766–1830) called Erik Kolstrøm (1796–1879). Louis Philippe visited the United States ( to 1798), staying in Philadelphia (where his brothers Antoine Philippe, Duke of Montpensier, Antoine and Louis-Charles, Count of Beaujolais, Louis Charles were in exile), New York City (where he most likely stayed at the Somerindyck House, Somerindyck family estate on Broadway and 75th Street with other exiled princes), and Boston. In Boston, he taught French for a time and lived in lodgings over what is now the Union Oyster House, Boston's oldest restaurant. During his time in the United States, Louis Philippe met with American politicians and people of high society, including George Clinton (vice president), George Clinton, John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and George Washington. His visit to Cape Cod in 1797 coincided with the division of the town of Eastham into two towns, one of which took the name of Orleans, possibly in his honour. During their sojourn, the Orléans princes travelled throughout the country, as far south as Nashville, Tennessee, Nashville and as far north as Maine. The brothers were even held in Philadelphia briefly during an outbreak of yellow fever. Louis Philippe is also thought to have met Isaac Snow of Orleans, Massachusetts, Orleans, Massachusetts, who had escaped to France from a British prison ship, prison hulk during the American Revolutionary War. In 1839, while reflecting on his visit to the United States, Louis Philippe explained in a letter to François Guizot, Guizot that his three years there had a large influence on his political beliefs and judgments when he became king. In Boston, Louis Philippe learned of the coup of 18 Fructidor (4 September 1797) and of the exile of his mother to Spain. He and his brothers then decided to return to Europe. They went to New Orleans, planning to sail to Havana and thence to Spain. This, however, was a troubled journey, as Spain and Great Britain were then at war. While in Louisiana (New Spain), colonial Louisiana in 1798, they were entertained by Julien de Lallande Poydras, Julien Poydras in the town of Point Coupee, Louisiana, Pointe Coupée, as well as by the Bernard de Marigny#Early life, Marigny de Mandeville family in New Orleans. They sailed for Havana in an American corvette, but a British warship intercepted their ship in the Gulf of Mexico. The British seized the three brothers, but took them to Havana anyway. Unable to find passage to Europe, the three brothers spent a year in Cuba (from spring 1798 to autumn 1799), until they were unexpectedly expelled by the Spanish authorities. They sailed via the Bahamas to Nova Scotia, where they were received by Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, the Duke of Kent, son of King George III of the United Kingdom, George III and (later) father of Victoria of the United Kingdom, Queen Victoria. Louis Philippe struck up a lasting friendship with the British prince. Eventually, the brothers sailed back to New York, and in January 1800, they arrived in England, where they stayed for the next fifteen years. During these years, Louis Philippe taught mathematics and geography at the now-defunct Great Ealing School, reckoned, in its 19th-century heyday, to be "the best private school in England".Marriage

In 1808, Louis Philippe proposed to Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom, Princess Elizabeth, daughter of King George III of the United Kingdom. His Catholicism and the opposition of her mother Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen Charlotte meant the Princess reluctantly declined the offer.

In 1809, Louis Philippe married Princess Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily, daughter of King Ferdinand IV of Naples and Maria Carolina of Austria. The ceremony was celebrated in Palermo 25 November 1809. The marriage was controversial because her mother's younger sister was Queen Marie Antoinette, and Louis Philippe's father was considered to have a role in Marie Antoinette's execution. The Queen of Naples was opposed to the match for this reason. She had been very close to her sister and devastated by her execution, but she had given her consent after Louis Philippe had convinced her that he was determined to compensate for the mistakes of his father, and after having agreed to answer all her questions regarding his father.Dyson. C.C, ''The Life of Marie Amelie Last Queen of the French, 1782–1866'', BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008.

In 1808, Louis Philippe proposed to Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom, Princess Elizabeth, daughter of King George III of the United Kingdom. His Catholicism and the opposition of her mother Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen Charlotte meant the Princess reluctantly declined the offer.

In 1809, Louis Philippe married Princess Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily, daughter of King Ferdinand IV of Naples and Maria Carolina of Austria. The ceremony was celebrated in Palermo 25 November 1809. The marriage was controversial because her mother's younger sister was Queen Marie Antoinette, and Louis Philippe's father was considered to have a role in Marie Antoinette's execution. The Queen of Naples was opposed to the match for this reason. She had been very close to her sister and devastated by her execution, but she had given her consent after Louis Philippe had convinced her that he was determined to compensate for the mistakes of his father, and after having agreed to answer all her questions regarding his father.Dyson. C.C, ''The Life of Marie Amelie Last Queen of the French, 1782–1866'', BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008.

Bourbon Restoration (1815–1830)

After the abdication of Napoleon, Louis Philippe, known as ''Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans'', returned to France during the reign of his cousin Louis XVIII of France, Louis XVIII, at the time of theBourbon Restoration Bourbon Restoration may refer to:

France under the House of Bourbon:

* Bourbon Restoration in France (1814, after the French revolution and Napoleonic era, until 1830; interrupted by the Hundred Days in 1815)

Spain under the Spanish Bourbons:

* ...

. Louis Philippe had reconciled the Orléans family with Louis XVIII in exile, and was once more to be found in the elaborate royal court. However, his resentment at the treatment of his family, the cadet branch of the House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanis ...

under the ''Ancien Régime'', caused friction between him and Louis XVIII, and he openly sided with the liberal opposition.

Louis Philippe was on far friendlier terms with Louis XVIII's brother and successor, Charles X, who acceded to the throne in 1824, and with whom he socialized. However, his opposition to the policies of Villèle and later of Jules de Polignac caused him to be viewed as a constant threat to the stability of Charles' government. This soon proved to be to his advantage.

King of the French (1830–1848)

In 1830, the July Revolution overthrew Charles X, who abdicated in favour of his 10-year-old grandson, Henri, comte de Chambord, Henri, Duke of Bordeaux. Charles X named Louis Philippe ''Lieutenant général du royaume'', and charged him to announce his desire to have his grandson succeed him to the popularly elected Chamber of Deputies of France, Chamber of Deputies. Louis-Philippe did not do this, in order to increase his own chances of succession. As a consequence, because the chamber was aware of his liberal policies and of his popularity with the masses, they proclaimed Louis-Philippe as the new French king, displacing the senior branch of the

In 1830, the July Revolution overthrew Charles X, who abdicated in favour of his 10-year-old grandson, Henri, comte de Chambord, Henri, Duke of Bordeaux. Charles X named Louis Philippe ''Lieutenant général du royaume'', and charged him to announce his desire to have his grandson succeed him to the popularly elected Chamber of Deputies of France, Chamber of Deputies. Louis-Philippe did not do this, in order to increase his own chances of succession. As a consequence, because the chamber was aware of his liberal policies and of his popularity with the masses, they proclaimed Louis-Philippe as the new French king, displacing the senior branch of the House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanis ...

. For the prior eleven days Louis-Philippe had been acting as the regent for the young Henri.

Charles X and his family, including his grandson, went into exile in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the United Kingdom. The young ex-king, the Duke of Bordeaux, in exile took the title of ''Comte de Chambord''. Later he became the pretender to the throne of France and was supported by the Légitimists.

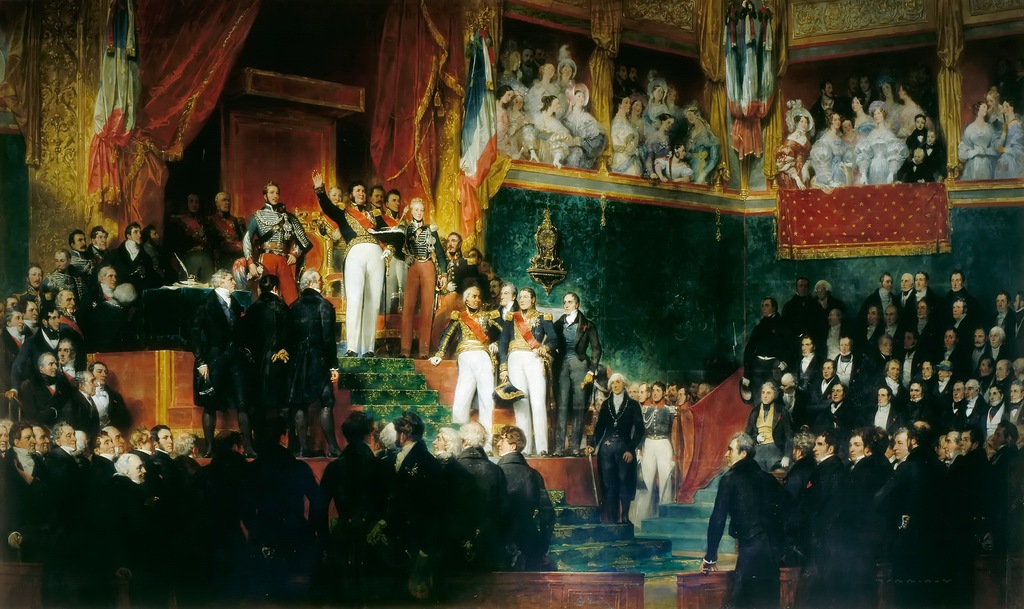

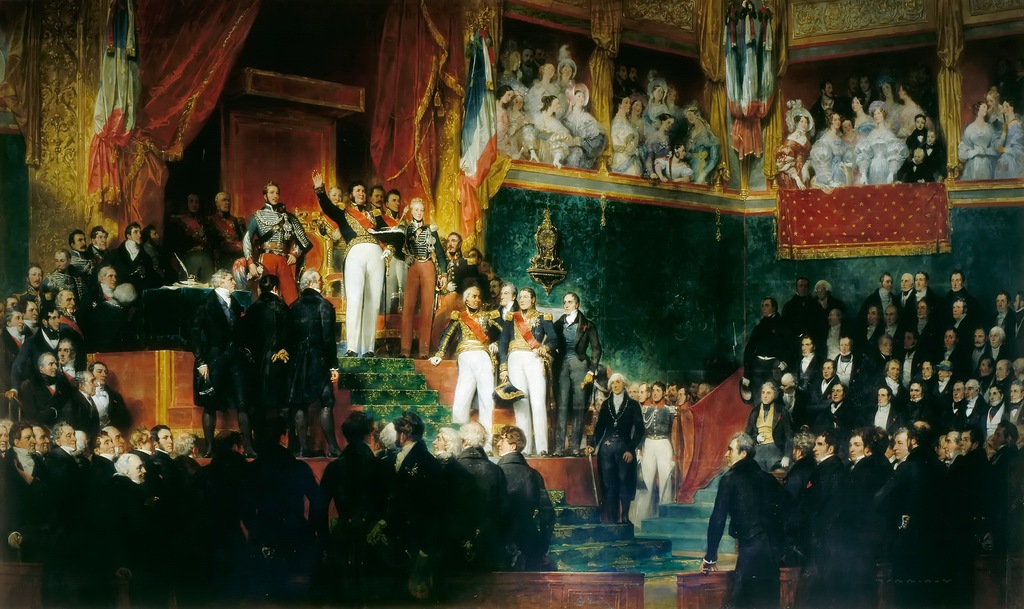

Louis-Philippe was sworn in as King Louis-Philippe I on 9 August 1830. Upon his accession to the throne, Louis-Philippe assumed the title of ''King of the French'', a title previously adopted by Louis XVI in the short-lived French Constitution of 1791, Constitution of 1791. Linking the popular monarchy, monarchy to a people instead of a territory (as the previous designation ''King of France and of Navarre'') was aimed at undercutting the Légitimist claims of Charles X and his family.

By an ordinance he signed on 13 August 1830, the new king defined the manner in which his children, as well as his "beloved" sister, would continue to bear the surname "d'Orléans" and the arms of Orléans, declared that his eldest son, as ''Crown Prince, Prince Royal'' (not ''Dauphin''), would bear the title ''Duke of Orléans

Duke of Orléans (french: Duc d'Orléans) was a French royal title usually granted by the King of France to one of his close relatives (usually a younger brother or son), or otherwise inherited through the male line. First created in 1344 by King ...

'', that the younger sons would continue to have their previous titles, and that his sister and daughters would be styled ''Princesses of Orléans'', not ''of France''.

His ascent to the title of King of the French was seen as a betrayal by Nicholas I of Russia, Emperor Nicholas I of Russia. Nicholas ended their friendship.

In 1832, Louis' daughter, Princess Louise-Marie of France, Louise-Marie, married the first ruler of Belgium, Leopold I of Belgium, Leopold I, King of the Belgians. Their descendants include all subsequent Kings of the Belgians, and Empress Carlota of Mexico.

Rule

Louis Philippe ruled in an unpretentious fashion, avoiding the pomp and lavish spending of his predecessors. Despite this outward appearance of simplicity, his support came from the wealthy ''bourgeoisie''. At first, he was much loved and called the "Citizen King" and the "bourgeois monarch", but his popularity suffered as his government was perceived as increasingly conservative and monarchical, despite his decision to have retour des cendres, Napoleon's remains returned to France. Under his management, the conditions of the working classes deteriorated, and the income gap widened considerably. In foreign affairs it was a quiet period, with friendship with Great Britain.

An industrial and agricultural depression in 1846 led to the Revolutions of 1848 in France, 1848 Revolutions, and Louis Philippe's abdication.

The dissonance between his positive early reputation and his late unpopularity was epitomized by Victor Hugo in ''Les Misérables'' as an oxymoron describing his reign as "Prince Equality", in which Hugo states:

Louis Philippe ruled in an unpretentious fashion, avoiding the pomp and lavish spending of his predecessors. Despite this outward appearance of simplicity, his support came from the wealthy ''bourgeoisie''. At first, he was much loved and called the "Citizen King" and the "bourgeois monarch", but his popularity suffered as his government was perceived as increasingly conservative and monarchical, despite his decision to have retour des cendres, Napoleon's remains returned to France. Under his management, the conditions of the working classes deteriorated, and the income gap widened considerably. In foreign affairs it was a quiet period, with friendship with Great Britain.

An industrial and agricultural depression in 1846 led to the Revolutions of 1848 in France, 1848 Revolutions, and Louis Philippe's abdication.

The dissonance between his positive early reputation and his late unpopularity was epitomized by Victor Hugo in ''Les Misérables'' as an oxymoron describing his reign as "Prince Equality", in which Hugo states:

Assassination attempt

Louis Philippe survived seven assassination attempts.

On 28 July 1835, Louis Philippe survived an assassination attempt by Giuseppe Mario Fieschi and two other conspirators in Paris. During the king's annual review of the Paris National Guard commemorating the revolution, Louis Philippe was passing along the Boulevard du Temple, which connected Place de la République to the Bastille, accompanied by three of his sons, the Ferdinand Philippe, Duke of Orléans, Duke of Orleans, the Prince Louis, Duke of Nemours, Duke of Nemours, and the François d'Orléans, Prince of Joinville, Prince de Joinville, and numerous staff.

Fieschi, a Corsican ex-soldier, attacked the procession with a weapon he built himself, a volley gun that later became known as the Infernal machine (weapon), ''Machine infernale''. This consisted of 25 gun barrels fastened to a wooden frame that could be fired simultaneously. The device was fired from the third level of n° 50 Boulevard du Temple (a commemorative plaque has since been engraved there), which had been rented by Fieschi.

A ball only grazed the King's forehead. Eighteen people were killed, including Lieutenant Colonel of the 8th Legion together with eight other officers, Édouard Adolphe Casimir Joseph Mortier, Marshal Mortier, duc de Trévise, and Colonel Raffet, General Girard, Captain Villate, General La Chasse de Vérigny, a woman, a 14-year-old girl and two men. A further 22 people were injured. The King and the princes escaped essentially unharmed. Horace Vernet, the King's painter, was ordered to make a drawing of the event.

Several of the gun barrels of Fieschi's weapon burst when it was fired; he was badly injured and was quickly captured. He was executed by guillotine together with his two co-conspirators the following year.

Louis Philippe survived seven assassination attempts.

On 28 July 1835, Louis Philippe survived an assassination attempt by Giuseppe Mario Fieschi and two other conspirators in Paris. During the king's annual review of the Paris National Guard commemorating the revolution, Louis Philippe was passing along the Boulevard du Temple, which connected Place de la République to the Bastille, accompanied by three of his sons, the Ferdinand Philippe, Duke of Orléans, Duke of Orleans, the Prince Louis, Duke of Nemours, Duke of Nemours, and the François d'Orléans, Prince of Joinville, Prince de Joinville, and numerous staff.

Fieschi, a Corsican ex-soldier, attacked the procession with a weapon he built himself, a volley gun that later became known as the Infernal machine (weapon), ''Machine infernale''. This consisted of 25 gun barrels fastened to a wooden frame that could be fired simultaneously. The device was fired from the third level of n° 50 Boulevard du Temple (a commemorative plaque has since been engraved there), which had been rented by Fieschi.

A ball only grazed the King's forehead. Eighteen people were killed, including Lieutenant Colonel of the 8th Legion together with eight other officers, Édouard Adolphe Casimir Joseph Mortier, Marshal Mortier, duc de Trévise, and Colonel Raffet, General Girard, Captain Villate, General La Chasse de Vérigny, a woman, a 14-year-old girl and two men. A further 22 people were injured. The King and the princes escaped essentially unharmed. Horace Vernet, the King's painter, was ordered to make a drawing of the event.

Several of the gun barrels of Fieschi's weapon burst when it was fired; he was badly injured and was quickly captured. He was executed by guillotine together with his two co-conspirators the following year.

Abdication and death (1848–1850)

On 24 February 1848, during the Revolutions of 1848 in France, February 1848 Revolution, King Louis Philippe abdicated in favour of his nine-year-old grandson, Philippe, comte de Paris. Fearful of what had happened to the deposed Louis XVI, Louis Philippe quickly left Paris under disguise. He rode in an ordinary cab under the name of "Mr. Smith". He fled to England and spent his final years incognito as the 'Comte de Neuilly'.

The National Assembly of France initially planned to accept young Philippe as king, but the strong current of public opinion rejected that. On 26 February, the French Second Republic, Second Republic was proclaimed. Louis Napoléon Bonaparte was elected president on 10 December 1848; on 2 December 1851, he declared himself president for life and then Emperor Napoleon III of France, Napoleon III in 1852.

Louis Philippe and his family remained in exile in Great Britain in Claremont (country house), Claremont, Surrey, though a plaque on Angel Hill, Bury St Edmunds, claims that he spent some time there, possibly due to a friendship with the Marquess of Bristol, who lived nearby at Ickworth House. The royal couple spent some time by the sea at St. LeonardsRoyal Victoria Hotel - Historical Hastings Wiki

On 24 February 1848, during the Revolutions of 1848 in France, February 1848 Revolution, King Louis Philippe abdicated in favour of his nine-year-old grandson, Philippe, comte de Paris. Fearful of what had happened to the deposed Louis XVI, Louis Philippe quickly left Paris under disguise. He rode in an ordinary cab under the name of "Mr. Smith". He fled to England and spent his final years incognito as the 'Comte de Neuilly'.

The National Assembly of France initially planned to accept young Philippe as king, but the strong current of public opinion rejected that. On 26 February, the French Second Republic, Second Republic was proclaimed. Louis Napoléon Bonaparte was elected president on 10 December 1848; on 2 December 1851, he declared himself president for life and then Emperor Napoleon III of France, Napoleon III in 1852.

Louis Philippe and his family remained in exile in Great Britain in Claremont (country house), Claremont, Surrey, though a plaque on Angel Hill, Bury St Edmunds, claims that he spent some time there, possibly due to a friendship with the Marquess of Bristol, who lived nearby at Ickworth House. The royal couple spent some time by the sea at St. LeonardsRoyal Victoria Hotel - Historical Hastings Wikiaccessdate: 22 May 2020 and later at the Marquess's home in Brighton. Louis Philippe died at Claremont on 26 August 1850. He was first buried at St. Charles Borromeo Chapel in Weybridge, Surrey. In 1876, his remains and those of his wife were taken to France and buried at the ''Chapelle royale de Dreux'', the Orléans family necropolis his mother had built in 1816, and which he had enlarged and embellished after her death.

Clash of the pretenders

The clashes of 1830 and 1848 between the Legitimists and the Orléanists over who was the rightful monarch were resumed in the 1870s. After the fall of the Second French Empire, Second Empire, a monarchist-dominated National Assembly offered a throne to the Legitimist pretender, Henri, comte de Chambord, Henri de France, comte de Chambord, as ''Henri V''. As he was childless, his heir was (except to the most extreme Legitimists) Louis Philippe's grandson, Philippe, Comte de Paris, Philippe d'Orléans, Comte de Paris. Thus the comte de Chambord's death would have united the House of Bourbon and House of Orléans. However, the comte de Chambord refused to take the throne unless the Flag of France, Tricolor flag of the Revolution was replaced with the fleur-de-lis flag of the ''Ancien Régime''. This the National Assembly was unwilling to do. The French Third Republic, Third Republic was established, though many intended for it to be temporary, and replaced by a constitutional monarchy after the death of the comte de Chambord. However, the comte de Chambord lived longer than expected. By the time of his death in 1883, support for the monarchy had declined, and public opinion sided with a continuation of the Third Republic, as the form of government that, according to Adolphe Thiers, "divides us least". Some suggested a monarchical restoration under a later comte de Paris after the fall of the Vichy regime but this was not seriously considered. Many of the few remaining French monarchists regard the descendants of Louis Philippe's grandson, who use the title ''Count of Paris'', as the rightful pretenders to the French throne; others, the Legitimists, consider Don Louis Alphonse, Duke of Anjou, Luis-Alfonso de Borbón, Duke of Anjou (to his supporters, "Louis XX"), to be the rightful heir. Head of the Royal House of Bourbon, Louis is descended in the male line from Philip V of Spain, the second grandson of the Sun-King, Louis XIV of France, Louis XIV. Philippe (King Philip V of Spain), however, had renounced his rights to the throne of France to prevent the much-feared union of France and Spain. The two sides challenged each other in the French Republic's law courts in 1897 and again nearly a century later. In the latter case, "Henri, Count of Paris (1908–1999), Henri, comte de Paris, duc de France", challenged the right of the Spanish-born pretender to use the title "Duke of Anjou". The French courts threw out his claim, deciding that the French Republic's legal system has no jurisdiction over the matter.Honours

National

* Order of the Holy Spirit, Knight of the Holy Spirit, ''2 February 1789'' * Legion of Honour, Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, ''3 July 1816''; Grand Master, ''9 August 1830'' * Order of Saint Louis, Grand Cross of the Military Order of St. Louis, ''10 July 1816'' * Founder and Grand Master of the Order of the Cross of July, ''13 December 1830''Foreign

* : Order of Leopold (Belgium), Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, ''10 March 1833'' * : Order of the Elephant, Knight of the Elephant, ''30 April 1846'' * Ernestine duchies: Saxe-Ernestine House Order, Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, ''March 1840'' * : Military William Order, Grand Cross of the Military William Order, ''22 March 1842''Militaire Willems-Orde: Bourbon, Louis Phillip prince de

' (in Dutch) * : Order of the Golden Fleece, Knight of the Golden Fleece, ''21 February 1834'' * Beylik of Tunis: Husainid Family Order * : ** Order of Saint Januarius, Knight of St. Januarius ** Order of Saint Ferdinand and of Merit, Grand Cross of St. Ferdinand and Merit * : Order of the Garter, Stranger Knight of the Garter, ''11 October 1844''

Arms

Territory

Akaroa, Port Louis-Philippe (Akaroa), the oldest French colonial empire, French colony in the South Pacific Ocean, South Pacific and the oldest town in the Canterbury Region of the New Zealand's South Island was named in honour of Louis Philippe who reigned as King of the French at the time the colony was established on 18 August 1840. Louis Philippe had been instrumental in patronage, supporting the settlement project. The Nanto-Bordelaise Company, company responsible for the endeavour received Louis Philippe's signature on 11 December 1839 as well as his permission to carry out the voyage in line with his policy of supporting colonial expansion and the construction of a French colonial empire#Second French colonial empire (after 1830), second empire which had first commenced under him in French rule in Algeria, Algeria around a decade earlier. The British Lieutenant-Governor Captain William Hobson subsequently went on to claim sovereignty over Port Louis-Philippe.

As a further honorific gesture to Louis Philippe and his Orléanist branch of the Bourbons, the ship on which the settlers sailed to found the eponymous colony of Port Louis-Philippe was named the Comte de Paris (ship), ''Comte de Paris'' after Louis Philippe's beloved infant grandson, Prince Philippe, Count of Paris, Prince Philippe d'Orléans, Count of Paris who was born on 24 August 1838.

Akaroa, Port Louis-Philippe (Akaroa), the oldest French colonial empire, French colony in the South Pacific Ocean, South Pacific and the oldest town in the Canterbury Region of the New Zealand's South Island was named in honour of Louis Philippe who reigned as King of the French at the time the colony was established on 18 August 1840. Louis Philippe had been instrumental in patronage, supporting the settlement project. The Nanto-Bordelaise Company, company responsible for the endeavour received Louis Philippe's signature on 11 December 1839 as well as his permission to carry out the voyage in line with his policy of supporting colonial expansion and the construction of a French colonial empire#Second French colonial empire (after 1830), second empire which had first commenced under him in French rule in Algeria, Algeria around a decade earlier. The British Lieutenant-Governor Captain William Hobson subsequently went on to claim sovereignty over Port Louis-Philippe.

As a further honorific gesture to Louis Philippe and his Orléanist branch of the Bourbons, the ship on which the settlers sailed to found the eponymous colony of Port Louis-Philippe was named the Comte de Paris (ship), ''Comte de Paris'' after Louis Philippe's beloved infant grandson, Prince Philippe, Count of Paris, Prince Philippe d'Orléans, Count of Paris who was born on 24 August 1838.

Issue

See also

* Louis Philippe style * List of works by James Pradier * Paris under Louis-Philippe * Lieutenant-General (France) * Origins of the French Foreign Legion * Akaroa, Port Louis-Philippe (Akaroa)Namesakes

*Louis Philippe, Crown Prince of Belgium (1833-1834), grandson by his daughter Queen Louise of the Belgians *Luís Filipe, Prince Royal of Portugal (1887-1908), great-great-grandson and heir to the Portuguese ThroneNotes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* Aston, Nigel. "Orleanism, 1780–1830," ''History Today'', Oct 1988, Vol. 38 Issue 10, pp 41–47 * Bastide, Charles. "The Anglo-French Entente under Louis-Philippe." ''Economica'', no. 19, (1927), pp. 91–98online

* Beik, Paul. ''Louis Philippe and the July Monarchy'' (1965) * Collingham, H.A.C. ''The July Monarchy: A Political History of France, 1830–1848'' (Longman, 1988) * Howarth, T.E.B. ''Citizen-King: The Life of Louis Philippe, King of the French'' (1962). * Jardin, Andre, and Andre-Jean Tudesq. ''Restoration and Reaction 1815–1848'' (The Cambridge History of Modern France) (1988) * Lucas-Dubreton, J. ''The Restoration and the July Monarchy'' (1929) * Newman, Edgar Leon, and Robert Lawrence Simpson. ''Historical Dictionary of France from the 1815 Restoration to the Second Empire'' (Greenwood Press, 1987

online edition

* Porch, Douglas. "The French Army Law of 1832." ''Historical Journal'' 14, no. 4 (1971): 751–69

online

External links

*Caricatures of Louis Philippe and others, published in ''La Caricature (1830–1843), La Caricature'' 1830–1835 , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Louis Philippe I Louis Philippe I, 1773 births 1850 deaths 19th-century monarchs of France 19th-century Princes of Andorra Nobility from Paris French Roman Catholics Kings of France House of Orléans Dukes of Enghien Dukes of Montpensier Dukes of Chartres Burials at the Chapelle royale de Dreux People of the July Monarchy, People of the Belgian Revolution People of the French Revolution French people of the Revolutions of 1848 French expatriates in England Monarchs who abdicated French Republican military leaders of the French Revolutionary Wars Names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe French generals 18th-century peers of France Members of the Chamber of Peers of the Bourbon Restoration Princes of Andorra Princes of France (Bourbon) Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Extra Knights Companion of the Garter Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of William Orléanist pretenders to the French throne Royal reburials