Joseph Weydemeyer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joseph Arnold Weydemeyer (February 2, 1818,

Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state distr ...

– August 26, 1866, St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

) was a military officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

in the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

as well as a journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalism ...

, politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

and Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

.

At first a supporter of " true socialism", Weydemeyer became in 1845–1846 a follower of Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' League of Communists, heading its

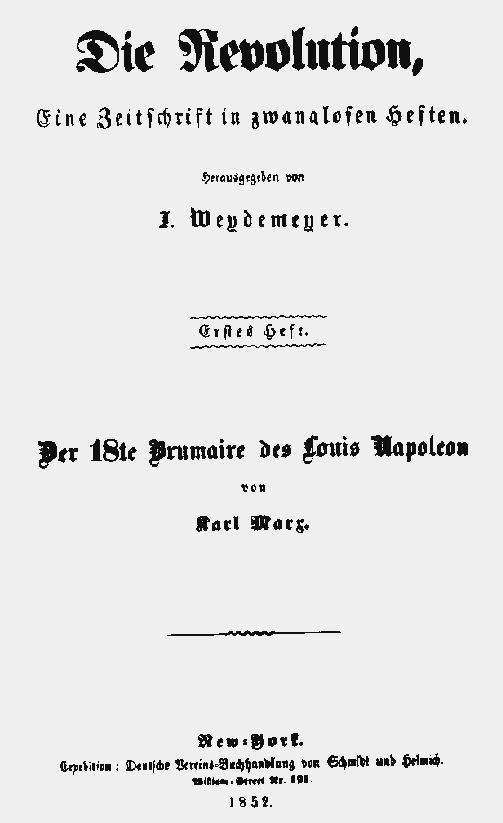

In December 1851, Weydemeyer issues a paper, named ''Die Revolution'', a German-language revolutionary paper, which purpose was to make picture of the

In December 1851, Weydemeyer issues a paper, named ''Die Revolution'', a German-language revolutionary paper, which purpose was to make picture of the

''Joseph Weydemeyer: Pioneer of American Socialism'' by Karl Obermann, 1947.''Socialism in German American Literature'', Issue 24

William Frederic Kamman 1917 * Archive o

Joseph Weydemeyer Papers

at the

'' League of Communists, heading its

Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

chapter from 1849 to 1851. He visited Marx in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, staying there for a time to attend Marx's lectures. He participated in the 1848 Revolution

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

. He was one of the "responsible editors" of the ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung

The ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung: Organ der Demokratie'' ("New Rhenish Newspaper: Organ of Democracy") was a German daily newspaper, published by Karl Marx in Cologne between 1 June 1848 and 19 May 1849. It is recognised by historians as one of the ...

'' from 1849 to 1850. He acted on Marx's behalf in the failed publication of the manuscript of ''The German Ideology

''The German Ideology'' (German: ''Die deutsche Ideologie'', sometimes written as ''A Critique of the German Ideology'') is a set of manuscripts originally written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels around April or early May 1846. Marx and Engels ...

''.

Weydemeyer worked on two socialist periodicals which were the ''Westphälisches Dampfboot'' ("Westphalian Steamboat") and the ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung''. In 1851, he emigrated from Germany to the United States and worked there as a journalist. ''The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon

''The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon'' (german: italic=yes, Der 18te Brumaire des Louis Napoleon) is an essay written by Karl Marx between December 1851 and March 1852, and originally published in 1852 in ''Die Revolution'', a German mo ...

'', written by Marx, was published in 1852 in ''Die Revolution'', a German-language monthly magazine in New York established by Weydemeyer.

Weydemeyer took part in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

as a lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

.

Biography

Early Years

Born in 1818, the same year asKarl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, Weydemeyer was the son of a Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n civil servant residing in Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state distr ...

, Westphalia

Westphalia (; german: Westfalen ; nds, Westfalen ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the regio ...

. Sent to a gymnasium and the Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

military Academy, he received his commission as a Leutnant

() is the lowest Junior officer rank in the armed forces the German (language), German-speaking of Germany (Bundeswehr), Austrian Armed Forces, and military of Switzerland.

History

The German noun (with the meaning "" (in English "deputy") fro ...

in the Prussian artillery (1. Westfälisches Feldartillerie-Regiment Nr. 7) :de:1. Westfälisches Feldartillerie-Regiment Nr. 7 in 1838. At the beginning of his short career, he was stationed in the Westphalian town of Minden

Minden () is a middle-sized town in the very north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, the greatest town between Bielefeld and Hanover. It is the capital of the district (''Kreis'') of Minden-Lübbecke, which is part of the region of Detm ...

. He began to read the bourgeois radical and socialist newspaper ''Rheinische Zeitung

The ''Rheinische Zeitung'' ("Rhenish Newspaper") was a 19th-century German newspaper, edited most famously by Karl Marx. The paper was launched in January 1842 and terminated by Prussian state censorship in March 1843. The paper was eventually su ...

'', the Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

paper Marx became editor and which was suppressed by Prussian censorship in 1843. But it inspired many soldiers in the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

and Westphalia. In the Minden garrison, the paper inspired revolutionaries like Fritz Anneke

Karl Friedrich Theodor "Fritz" Anneke () was a German revolutionary, socialist and newspaper editor. He emigrated to the United States with his family in 1849 and became a Union Army officer in the American Civil War, and later worked as an en ...

, August Willich

August Willich (November 19, 1810 – January 22, 1878), born Johann August Ernst von Willich, was a military officer in the Prussian Army and a leading early proponent of communism in Germany. In 1847 he discarded his title of nobility. He later ...

, Hermann Korff, and Friedrich von Beust

Friedrich (von) Beust (August 9, 1817 – December 6, 1899), German soldier, revolutionary and political activist and Swiss reform pedagogue, was the son of Prussian Major Karl Alexander von Beust. Beust was born in the Odenwald, in whose great f ...

, all of whom, like Weydemeyer, will become prominent Forty-Eighters

The Forty-Eighters were Europeans who participated in or supported the Revolutions of 1848 that swept Europe. In the German Confederation, the Forty-Eighters favoured unification of Germany, a more democratic government, and guarantees of human r ...

and after that officers of the Union army in the Civil War.

The leftist officers in Minden formed a circle in which Weydemeyer took part. He also went frequently to Cologne and took part to discussions of social problems with the journalists of the ''Rheinische Zeitung''. In 1844, Weydemeyer resigned from the Prussian army. He then became assistant editor of the ''Trierische Zeitung'', a paper which advocated the Phalansteries of Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical in ...

and the True Socialism of Karl Gruen. In 1845, he joined the ''Westphaelische Dampfboot'' after paying a visit to Marx, exiled in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

. Marx, as well as Engels, were publishing in the ''Dampfboot''. The paper was edited by Heinrich Otto Lüning in Bielefeld

Bielefeld () is a city in the Ostwestfalen-Lippe Region in the north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population of 341,755, it is also the most populous city in the administrative region (''Regierungsbezirk'') of Detmold and the ...

and Paderborn

Paderborn (; Westphalian: ''Patterbuorn'', also ''Paterboärn'') is a city in eastern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, capital of the Paderborn district. The name of the city derives from the river Pader and ''Born'', an old German term for t ...

. Lüning's sister Luise became Weydemeyer's wife in 1845.

1848

After a second visit to Marx inBrussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

in 1846, Weydemeyer went back to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

to organize the Communist League

The Communist League (German: ''Bund der Kommunisten)'' was an international political party established on 1 June 1847 in London, England. The organisation was formed through the merger of the League of the Just, headed by Karl Schapper, and the ...

in Cologne. This was the organization for which Marx and Engels wrote the ''Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'', originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (german: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei), is a political pamphlet written by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Comm ...

'' in 1847. He continued to work on the ''Dampfboot''. At the same time, he made a career as a construction engineer for the Cologne–Minden Railroad, but he quit the job soon after the beginning in 1848 because the company ordered its employees to stay out of political demonstration.

During the rest of the year, he was a full-time revolutionary journalist. In June 1848, he was invited to Darmstadt

Darmstadt () is a city in the States of Germany, state of Hesse in Germany, located in the southern part of the Frankfurt Rhine Main Area, Rhine-Main-Area (Frankfurt Metropolitan Region). Darmstadt has around 160,000 inhabitants, making it th ...

by the socialist publisher C. W. Leske to be co-editor with Heinrich Otto Lüning of the ''Neue Deutsche Zeitung''. Near to Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

, where the German National Assembly was meeting at the time, the newspaper intended to be a link between the left-wing of the Assembly and the extra-parliamentary movement. But in 1849, the counter-revolution succeeded and the Prussian absolutism crushed the Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Parliament (german: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung, literally ''Frankfurt National Assembly'') was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, elected on 1 Ma ...

, the armed democracy in Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden is ...

and the Electorate of the Palatinate

The Electoral Palatinate (german: Kurpfalz) or the Palatinate (), officially the Electorate of the Palatinate (), was a state that was part of the Holy Roman Empire. The electorate had its origins under the rulership of the Counts Palatine of ...

and all the democratic papers. Marx's ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung

The ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung: Organ der Demokratie'' ("New Rhenish Newspaper: Organ of Democracy") was a German daily newspaper, published by Karl Marx in Cologne between 1 June 1848 and 19 May 1849. It is recognised by historians as one of the ...

'' disappeared under the censorship and the ''Neue Deutsche Zeitung'' survived by moving from Darmstadt to Frankfurt in the spring of 1849. The paper would be finally banished in December 1850 by the senate of the city. Weydemeyer remained in the country for half a year, underground.

In July 1851, with his wife and two children, he went to Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, where he did not find a job. On July 27, he wrote to Marx that he had no alternative than migrating to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. In his answer to Weydemeyer, Marx recommend New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

for his settlement, a place where Weydemeyer could have the chance to create a German-speaking revolutionary paper. At the same time, it was, for Marx, the city where the migrants were less likely to be touched by the Far West adventures. Marx also remarked that the United States would be a difficult country for the development of socialism, the surplus of population, being drained off by the farms and the fast-growing prosperity of the country, the Germans being easily Americanized and forgetting of their homeland. Weydemeyer and his family sailed from Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very cl ...

on September 29, 1851, and arrived in New York on November 7.

New York

A Marxist journalist

class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms ...

in the Old World. The paper first appeared on January 6 but was suspended on January 13. In a letter to Marx at the end of January, he attributed his failure because of the corrupting effect on the people of the American soil. He also pointed out the dominance of the liberal bourgeois-nationalist ideology on the people, among them Gottfried Kinkel

Johann Gottfried Kinkel (11 August 1815 – 13 November 1882) was a German poet also noted for his revolutionary activities and his escape from a Prussian prison in Spandau with the help of his friend Carl Schurz.

Early life

He was born at Ober ...

and Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva (, hu, udvardi és kossuthfalvi Kossuth Lajos, sk, Ľudovít Košút, anglicised as Louis Kossuth; 19 September 1802 – 20 March 1894) was a Hungarian nobleman, lawyer, journalist, poli ...

. German immigrants were simply not sensitive to Marx ideas and analyses of the defeat of the 1848 revolutions and of the triumph of European reaction. In spring 1852, Weydemeyer brought out Marx's ''Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

''The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon'' (german: italic=yes, Der 18te Brumaire des Louis Napoleon) is an essay written by Karl Marx between December 1851 and March 1852, and originally published in 1852 in ''Die Revolution'', a German mo ...

'' as a final number of ''Die Revolution'', after arranging for serial publication of Engels ''The Peasant War in Germany

''The Peasant War in Germany'' (German: ''Der deutsche Bauernkrieg'') by Friedrich Engels is a short account of the early-16th-century uprisings known as the German Peasants' War (1524–1525). It was written by Engels in London during the summ ...

'' in the New York '' Turn-Zeitung'' between January 1852 and February 1853.

He began to write for the '' Turn-Zeitung'' about different political issues, as the American aversion of the proletarian dictatorship

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat holds state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the ...

, the calling of liberal American groups for free election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative ...

in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and their silence about the conditions of the workers, the political immaturity of forty-eighters who raised money in the United States to foment revolution in Europe. To sum up, he wrote many articles which counterposed Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

to liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

for the German immigrants. In the July number of ''Turn-Zeitung'', he began a discussion of American labor issues and the free trade versus protection debate, where he took a traditional Marxist stand for the industrial development

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econom ...

.

In the ''Turn-Zeitung'' of September 1, Weydemeyer analyzed the relationship between Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

n cotton and American slavery

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slave ...

. The development of American monopoly on the world market, in his point of view, promotes the rise of national economical development rather than regional and the rise of national parties in American politics rather than regional. He saw the shift from an agricultural dominance over the industrial to an industrial dominance over the former.

In the ''Turn-Zeitung'' of November 15, Weydemeyer wrote a review of the election campaign of 1852, pointing the absence of labor issues in the platforms of the Whig and Democratic parties. In December, in a two-part ''Political-Economic Survey'', he attempted to project a platform for American labor. He stands for organizations of the workers on a large scale political as well as economical, and urged the workers to adopt internationalism

Internationalism may refer to:

* Cosmopolitanism, the view that all human ethnic groups belong to a single community based on a shared morality as opposed to communitarianism, patriotism and nationalism

* International Style, a major architectur ...

.

The foundation of the American Workers League

With four of his friends, Weydemeyer formed a tiny organization, the first Marxist organization in the United States, formed in the summer of 1852. The group, called ''Proletarierbund'', won the attention of German immigrants with the organization of a meeting on March 20, 1853, in New York, where eight hundred German Americans assembled in Mechanics Hall and founded theAmerican Workers League

The American Workers League (german: Amerikanische Arbeiterbund) was an American nineteenth century workers political organization.

The league was founded in 1853 by 800 German American delegates who attended the inaugural meeting in the Mechanic ...

.

This was an organization of mixed union and party functions, and presented a program of immediate issues for the working class and the socialist goal at the same time. The program was for immediate naturalization of all immigrants who wished to gain American citizenship, it favored federal, rather than state, labor legislation, stood for guaranteed payment of wages to workers whose employers went bankrupt, assumption by government of all costs of litigation with free choice of counsel, reducing the working day to ten hours, banning labor for children under sixteen, compulsory education with government maintenance for children whose families were too poor, against all Sunday and temperance laws, for the formation of tuition-colleges and for state acquisition of existing private colleges, for keeping the national lands on the frontier inalienable, etc. Beside the immediate demands, the League's platform stated some revolutionary principles. The preamble charged the capitalists of the everyday worse situation of the workers, the need of an independent political party for the workers, "without respect to occupation, language, color or sex", and the task of overthrowing the capital leadership with it as a way to solve social and political problems. It also leaned on the American Constitution of the Founding Fathers

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

.

The American Workers League functioned for several years under a central committee made up of delegates from wards clubs and trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and Employee ben ...

. Member of its committee, Weydemeyer tried to wide the influence of the League to non German Americans but the League served primarily as a German recreation and mutual aid society, in isolation from the English-speaking workers. When in the context of the Know-Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

agitation, in 1855, the members began forming a secret military organization to defend themselves against nativist attacks, Weydemeyer withdrew from the League. He devoted himself to study the American Economy and to writing and lecturing of Marxists ideas.

American Civil War

As the country was moving toward acivil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, German Americans played an important part in the emergence of the Republican Party, so did Weydemeyer, who was one of the men who drew the German community toward the Republicans and the antislavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

cause. Weydemeyer's stand for the Republicans was consistent with the influence of the most prominent labor radicals at the time, as Wilhelm Weitling

Wilhelm Christian Weitling (October 5, 1808 – January 25, 1871) was a German tailor, inventor, radical political activist and one of the first theorists of communism. Weitling gained fame in Europe as a social theorist before he emigrated t ...

. William Sylvis

William H. Sylvis (1828–1869) was a pioneer American trade union leader. Sylvis is best remembered as a founder of the Iron Molders' International Union. He also was a founder of the National Labor Union. It was one of the first American union ...

, leading native-born trade unionist, didn't engage in Republican politics, but showed approval for their platform in several commentaries published by Die Welt

''Die Welt'' ("The World") is a German national daily newspaper, published as a broadsheet by Axel Springer SE.

''Die Welt'' is the flagship newspaper of the Axel Springer publishing group. Its leading competitors are the ''Frankfurter Allg ...

.

The Republican Party gained also influence through the free-soil movement. According to his Marxist opinion against the parceling out of government lands to small farmers, Weydemeyer denounced the Homestead Act

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of th ...

agitation in 1854 as contrary to the interest of the workers and was in favor of large-scale agriculture. But in the 1860s, together with other German Republicans, he urged the party to campaign for "immediate passage by Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

of a Homestead law by which the public lands of the Union may be secured for homesteads of the people, and secured from the greed of speculators." Weydemeyer's backing of the free-soil movement and shift of position about that issue wasn't a stand for the free-soil movement as a social progress (as Hermann Kriege

Hermann Kriege (1820-1850) was a German American revolutionary and journalist of the first half of the 19th century.

His journalistic activities supporting socialist ideas caused him to be arrested and jailed in 1844. After serving his sentence ...

endorsement in this movement in 1845), but a question of tactic. Weydemeyer's support of the free-soil movement at that moment signified his support for the antislavery cause, the main issue at the time in his point of view.

Shortly after dropping the American Workers League

The American Workers League (german: Amerikanische Arbeiterbund) was an American nineteenth century workers political organization.

The league was founded in 1853 by 800 German American delegates who attended the inaugural meeting in the Mechanic ...

, Weydemeyer left New York and settled down in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

, where he lived for four years, first in Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

and then in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, where he worked as a journalist and also as a surveyor. He tried to establish in Chicago, another independent German labor paper, and contributed to the ''Illinois Staats-Zeitung

''Illinois Staats-Zeitung'' (''Illinois State Newspaper'') was one of the most well-known German-language newspapers of the United States; it was published in Chicago from 1848 until 1922. Along with the ''Westliche Post'' and ''Anzeiger des West ...

'', a famous German Republican daily of the Midwest. He took part in the ''Deutsches Haus'' conference of German-American societies in Chicago in May 1860 to influence the Republican convention

The Republican National Convention (RNC) is a series of U.S. presidential nominating convention, presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1856 by the United States Republican Party. They are administered by the Republican N ...

's platform and candidates. Back in New York at the end of 1860, he found a job as a surveyor of Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West Side, Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the List of New York City parks, fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban par ...

and became active in the election campaign for Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

. Eight months later, he was in the army.

Thanks to his background as a Prussian military officer and surveyor, he became a technical aide on the staff of General John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

, the commander of the department of the West. He superintended the erection of ten forts around St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

. After Frémont was removed from his command in November 1861, Weydemeyer was made a lieutenant colonel and given command of a Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

volunteer artillery regiment which took the field against Confederate guerillas in southern Missouri in 1862. At the end of the year, he was hospitalized for a nervous disorder and transferred to garrison duty in St. Louis, which he left in September 1863.

Politically active in Missouri, Weydemeyer was facing two main issues: the extension of emancipation to Missouri and the prevention of a split between the Lincoln and Frémont faction of the Republican Party. Despite his own sympathy for the Frémont straight position, he tried to conciliate the factions and keep safe the victory in the 1864 election and in the war. In September 1864, Weydemeyer joined the army as colonel of the 41st Missouri Volunteer Infantry charged with the defense of St. Louis. While doing his military duty, he distributed copies of the Inaugural Address of the International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

, exchanged letters with Engels on military and political issues, contributed to local papers, as the ''Daily St Louis Press'' where he wrote an editorial greeting the founding of the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation

An international organization or international organisation (see spelling differences), also known as ...

. In July 1865, he demobilized his regiment and left the Army.

At the end of the war, he began to write regularly for the ''Westliche Post

''Westliche Post'' (literally ''"Western Post"'') was a German-language daily newspaper published in St. Louis, Missouri. The ''Westliche Post'' was Republican in politics. Carl Schurz was a part owner for a time, and served as a U.S. Senator f ...

'' and the ''Neue Zeit'', two St. Louis papers. He won the election as county auditor, holding his office from January 1, 1866 until his death. He worked for harsher tax laws and collecting unpaid taxes of men who used the war to become rich. The same day William S. Sylvis inaugurated the National Labor Union

The National Labor Union (NLU) is the first national labor federation in the United States. Founded in 1866 and dissolved in 1873, it paved the way for other organizations, such as the Knights of Labor and the AFL (American Federation of Labor). ...

in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Weydemeyer died of cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, at the age of 48.

See also

*The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon

''The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon'' (german: italic=yes, Der 18te Brumaire des Louis Napoleon) is an essay written by Karl Marx between December 1851 and March 1852, and originally published in 1852 in ''Die Revolution'', a German mo ...

* International Workingmen's Association in America The International Workingmen's Association (IWA; 1864–1872) in the United States of America took the form of a loose network of about 35 frequently discordant local "sections," each professing allegiance to the London-based IWA, commonly known as ...

* Alexander Schimmelpfennig

* August Willich

August Willich (November 19, 1810 – January 22, 1878), born Johann August Ernst von Willich, was a military officer in the Prussian Army and a leading early proponent of communism in Germany. In 1847 he discarded his title of nobility. He later ...

Footnotes

External links

''Joseph Weydemeyer: Pioneer of American Socialism'' by Karl Obermann, 1947.

William Frederic Kamman 1917 * Archive o

Joseph Weydemeyer Papers

at the

International Institute of Social History

The International Institute of Social History (IISH/IISG) is one of the largest archives of labor and social history in the world. Located in Amsterdam, its one million volumes and 2,300 archival collections include the papers of major figur ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Weydemeyer, Joseph

1818 births

1866 deaths

Military personnel from Münster

American communists

American Marxists

German-American Forty-Eighters

German communists

German Marxists

German revolutionaries

American Marxist journalists

Members of the International Workingmen's Association

People of the Revolutions of 1848

Union Army colonels

American people of German descent

19th-century American journalists

American male journalists

19th-century male writers