Joseph Priestley and Dissent on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Priestley's patron at the time,

In 1787, 1789 and 1790, Dissenters again tried to repeal the

In 1787, 1789 and 1790, Dissenters again tried to repeal the

When arguing for materialism in his ''Examination'' Priestley strongly suggested that there was no mind-body duality. Such opinions shocked and angered many of his readers and reviewers who believed that for the

When arguing for materialism in his ''Examination'' Priestley strongly suggested that there was no mind-body duality. Such opinions shocked and angered many of his readers and reviewers who believed that for the

The Joseph Priestley Society

– Comprehensive site which includes a bibliography, links to related sites, images, information on manuscript collections, and other helpful information.

A General History of the Christian Church

(full text from google books)

A History of the Corruptions of Christianity

(full text from google books)

The Doctrines of Heathen Philosophy compared with those of Revelation

(full text from google books)

Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion, Vol. 1 of 2

(full text from google books)

Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion, Vol. 2 of 2

(full text from google books)

An History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ, Vol. 1

(full text from google books)

An History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ, Vol. 2

(full text from google books)

An History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ, Vol. 3

(full text from google books)

An History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ, Vol. 4

(full text from google books)

A Free Address to Protestant Dissenters

(full text from google books) {{Joseph Priestley English Christian theologians Christian theological movements Priestley, Joseph and Dissent Determinism English Unitarians Materialists Eponymous political ideologies

Joseph Priestley

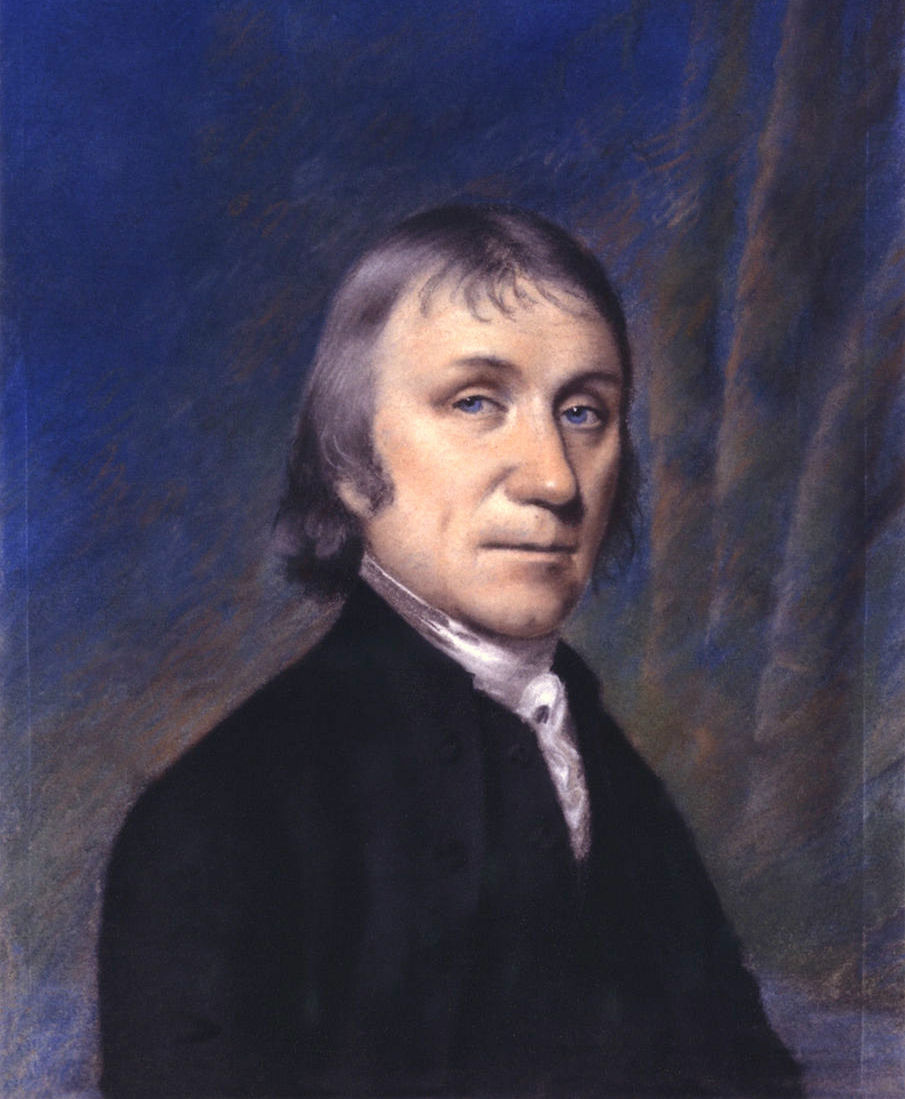

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

(13 March 1733 (old style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

) – 8 February 1804) was a British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

, political theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be academics or independent scholars. Here the most notable political theorists are categorized by their ...

, clergyman, theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, and educator. He was one of the most influential Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, and ...

of the late 18th-century.

A member of marginalized religious groups throughout his life and a proponent of what was called "rational Dissent", Priestley advocated religious toleration

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

(challenging even William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family i ...

), helped Theophilus Lindsey

Theophilus Lindsey (20 June 1723 O.S.3 November 1808) was an English theologian and clergyman who founded the first avowedly Unitarian congregation in the country, at Essex Street Chapel.

Early life

Lindsey was born in Middlewich, Cheshire, t ...

found the Unitarian church and promoted the repeal of the Test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

and Corporation Acts in the 1780s. As the foremost British expounder of providentialism

In Christianity, providentialism is the belief that all events on Earth are controlled by God.

Belief

Providentialism was sometimes viewed by its adherents as differing between national providence and personal providence. Some English and Americ ...

, he argued for extensive civil rights, believing that individuals could bring about progress and eventually the Millennium

A millennium (plural millennia or millenniums) is a period of one thousand years, sometimes called a kiloannum (ka), or kiloyear (ky). Normally, the word is used specifically for periods of a thousand years that begin at the starting point (ini ...

.Tapper, 314. Priestley's religious beliefs were integral to his metaphysics as well as his politics and he was the first philosopher to "attempt to combine theism, materialism, and determinism," a project that has been called "audacious and original."

Defender of Dissenters and political philosopher

Priestley claimed throughout his life that politics did not interest him and that he did not participate in it. What appeared to others as political arguments were for Priestley always, at their root, religious arguments. Many of what we would call Priestley's political writings were aimed at supporting the repeal of theTest

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

and Corporation Acts, a political issue that had its foundation in religion.

Between 1660 and 1665, Parliament passed a series of laws that restricted the rights of dissenters: they could not hold political office, teach school, serve in the military or attend Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

unless they ascribed to the thirty-nine Articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. In 1689, a Toleration Act was passed that restored some of these rights, if dissenters subscribed to 36 of the 39 articles (Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and Unitarians were excluded), but not all Dissenters were willing to accept this compromise and many refused to conform

Conformity is the act of matching attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to group norms, politics or being like-minded. Norms are implicit, specific rules, shared by a group of individuals, that guide their interactions with others. People often choo ...

. Throughout the 18th century Dissenters were persecuted and the laws against them were erratically enforced. Dissenters continually petitioned Parliament to repeal the Test and Corporation Acts, claiming that the laws made them second-class citizens. The situation worsened in 1753 after the passage of Lord Hardwicke's Marriage Act which stipulated that all marriages must be performed by Anglican ministers; some refused to perform Dissenting weddings at all.

Priestley's friends urged him to publish a work on the injustices borne by Dissenters, a topic to which he had already alluded in his ''Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life

''Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life'' (1765) is an educational treatise by the 18th-century British polymath Joseph Priestley.

Dedicated to the governing board of Warrington Academy at which Priestley was a tutor, ...

'' (1765). The result was Priestley's ''Essay on the First Principles of Government

''Essay on the First Principles of Government'' (1768) is an early work of modern liberal political theory by 18th-century British polymath Joseph Priestley.

Genesis of work

Priestley's friends urged him to publish a work on the injustices born ...

'', which Priestley's major modern biographer calls his "most systematic political work," in 1768. The book went through three English editions and was translated into Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

. Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

credited it with inspiring his "greatest happiness principle." The ''Essay on Government'' is not strictly utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

, however; like all of Priestley's works, it is infused with the belief that society is progressing towards perfection. Although much of the text rearticulates John Locke's arguments from his ''Two Treatises on Government

''Two Treatises of Government'' (or ''Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True Original, ...

'' (1689), it also makes a useful distinction between political and civil rights and argues for protection of extensive civil rights. He distinguishes between a private and a public sphere of governmental control; education and religion, in particular, he maintains, are matters of private conscience and should not be administered by the state. As Kramnick states, "Priestley's fundamental maxim of politics was the need to limit state interference on individual liberty." For early liberals like Priestley and Jefferson, the "defining feature of liberal politics" was its emphasis on the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

. In a statement that articulates key elements of early liberalism and anticipates utilitarian arguments, Priestley wrote:

It must necessarily be understood, therefore, that all people live in society for their mutual advantage; so that the good and happiness of the members, that is the majority of the members of any state, is the great standard by which every thing relating to that state must finally be determined.Priestley acknowledged that revolution was necessary at times but believed that Britain had already had its only necessary revolution in

1688

Events

January–March

* January 2 – Fleeing from the Spanish Navy, French pirate Raveneau de Lussan and his 70 men arrive on the west coast of Nicaragua, sink their boats, and make a difficult 10 day march to the city of Oco ...

, although his later writings would suggest otherwise. Priestley's later radicalism emerged from his belief that the British government was infringing upon individual freedom. Priestley would repeatedly return to these themes throughout his career, particularly when defending the rights of Dissenters.

Critic of William Blackstone's ''Commentaries''

In another attempt to champion the rights of Dissenters, Priestley defended their constitutional rights against the attacks ofWilliam Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family i ...

, an eminent legal theorist. Blackstone's ''Commentaries'', fast becoming the standard reference for legal interpretation, stated that dissent from the Church of England was a crime and argued that Dissenters could not be loyal subjects. Furious, Priestley lashed out with his ''Remarks on Dr. Blackstone's Commentaries'' (1769), correcting Blackstone's grammar, his history and his interpretation of the law. Blackstone, chastened, replied in a pamphlet and altered his ''Commentaries'' in subsequent editions; he rephrased the offending passages but still described Dissent as a crime.

Founder of Unitarianism

When Parliament rejected the Feather's Tavern petition in 1772, which would have released Dissenters from subscribing to thethirty-nine articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

, many Dissenting ministers, as William Paley

William Paley (July 174325 May 1805) was an English clergyman, Christian apologist, philosopher, and utilitarian. He is best known for his natural theology exposition of the teleological argument for the existence of God in his work ''Natural T ...

wrote, "could not afford to keep a conscience." Priestley's friend from Leeds, Theophilus Lindsey

Theophilus Lindsey (20 June 1723 O.S.3 November 1808) was an English theologian and clergyman who founded the first avowedly Unitarian congregation in the country, at Essex Street Chapel.

Early life

Lindsey was born in Middlewich, Cheshire, t ...

, decided to try. He gave up his church, sold his books so that he would have money to live on and established the first Unitarian chapel in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

. The radical publisher Joseph Johnson Joseph Johnson may refer to:

Entertainment

*Joseph McMillan Johnson (1912–1990), American film art director

*Smokey Johnson (1936–2015), New Orleans jazz musician

* N.O. Joe (Joseph Johnson, born 1975), American musician, producer and songwrit ...

helped him find a building, which became known as Essex Street Chapel

Essex Street Chapel, also known as Essex Church, is a Unitarian place of worship in London. It was the first church in England set up with this doctrine, and was established when Dissenters still faced legal threat. As the birthplace of British ...

.chapter 2 ''The History of Essex Hall'' by Mortimer Rowe B.A., D.D. Lindsey Press, 1959.Priestley's patron at the time,

Lord Shelburne

William Petty Fitzmaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne, (2 May 17377 May 1805; known as the Earl of Shelburne between 1761 and 1784, by which title he is generally known to history), was an Irish-born British Whig statesman who was the first ...

, promised that he would keep the church out of legal difficulties (barrister John Lee John Lee may refer to:

Academia

* John Lee (astronomer) (1783–1866), president of the Royal Astronomical Society

* John Lee (university principal) (1779–1859), University of Edinburgh principal

* John Lee (pathologist) (born 1961), English

...

, later Attorney-General, also helped), and Priestley and many others hurried to raise money for Lindsey.

On 17 April 1774, the chapel had its first service. Lindsey had designed his own liturgy, of which many were critical. Priestley rushed to his defense with ''Letter to a Layman, on the Subject of the Rev. Mr. Lindsey's Proposal for a Reformed English Church'' (1774), claiming that only the form of worship had been altered and attacking those who only followed religion as a fashion. Priestley attended the church regularly while living in Calne

Calne () is a town and civil parish in Wiltshire, southwestern England,OS Explorer Map 156, Chippenham and Bradford-on-Avon Scale: 1:25 000.Publisher: Ordnance Survey A2 edition (2007). at the northwestern extremity of the North Wessex Downs h ...

with Shelburne and even occasionally preached there. He continued to support institutionalized Unitarianism after he moved to Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

in 1780, encouraging the foundation of new Unitarian chapels throughout Britain and the United States. He wrote numerous letters in defence of Unitarianism, in particular against certain ministers

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of governme ...

and scholars such as Samuel Horsley

Samuel Horsley (15 September 1733 – 4 October 1806) was a British churchman, bishop of Rochester from 1793. He was also well versed in physics and mathematics, on which he wrote a number of papers and thus was elected a Fellow of the Royal Soc ...

, Alexander Geddes

Alexander Geddes (14 September 1737 – 26 February 1802) was a Scottish theologian and scholar. He translated a major part of the Old Testament of the Catholic Bible into English.

Translations and commentaries

Geddes was born at Rathven, B ...

, George Horne and Thomas Howes. These letters were compiled and published (by the author) in an "annual reply" covering the years 1786-1789. He also compiled and edited a liturgy and hymnbook for the new denomination.

Religious activist

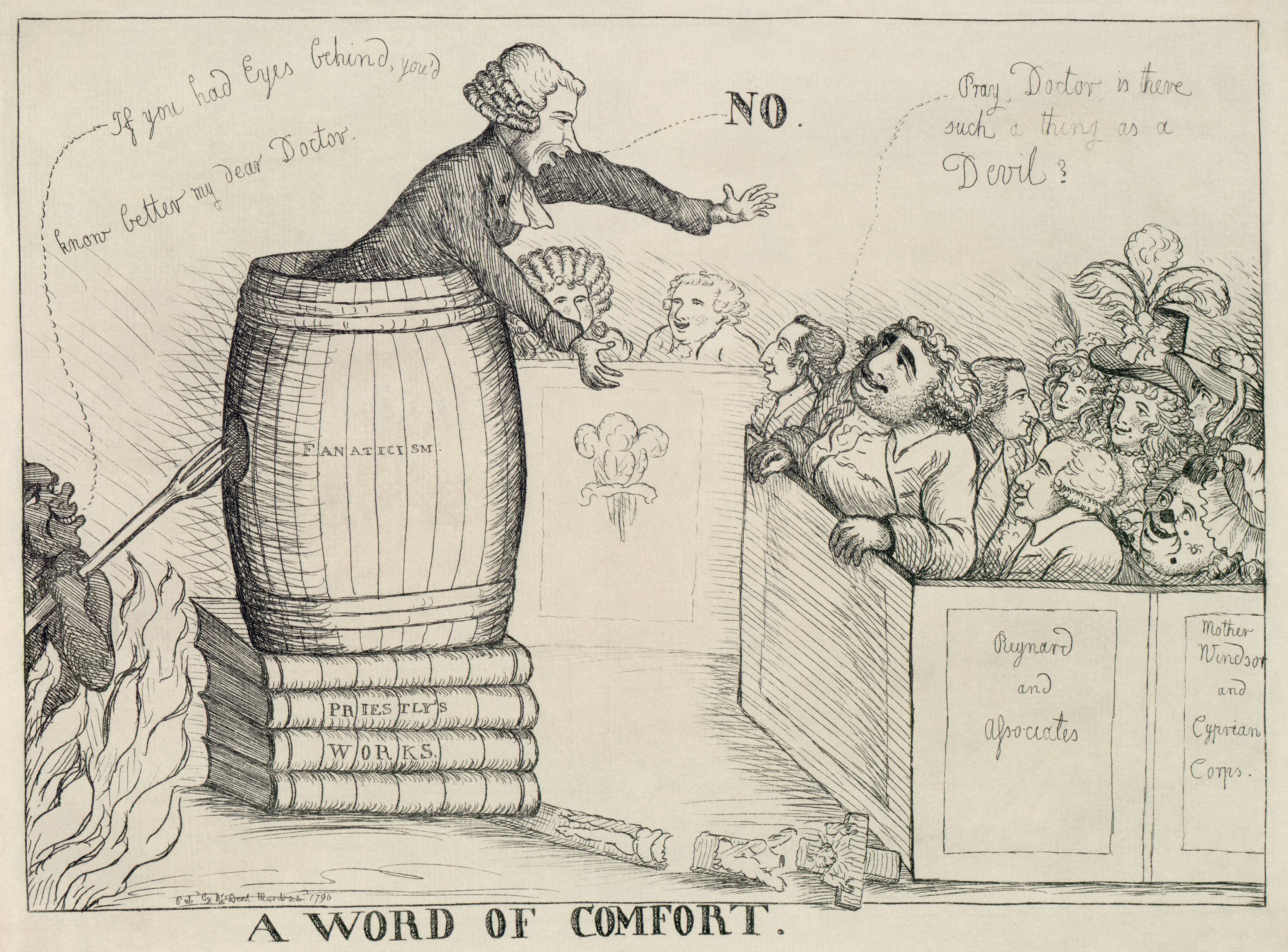

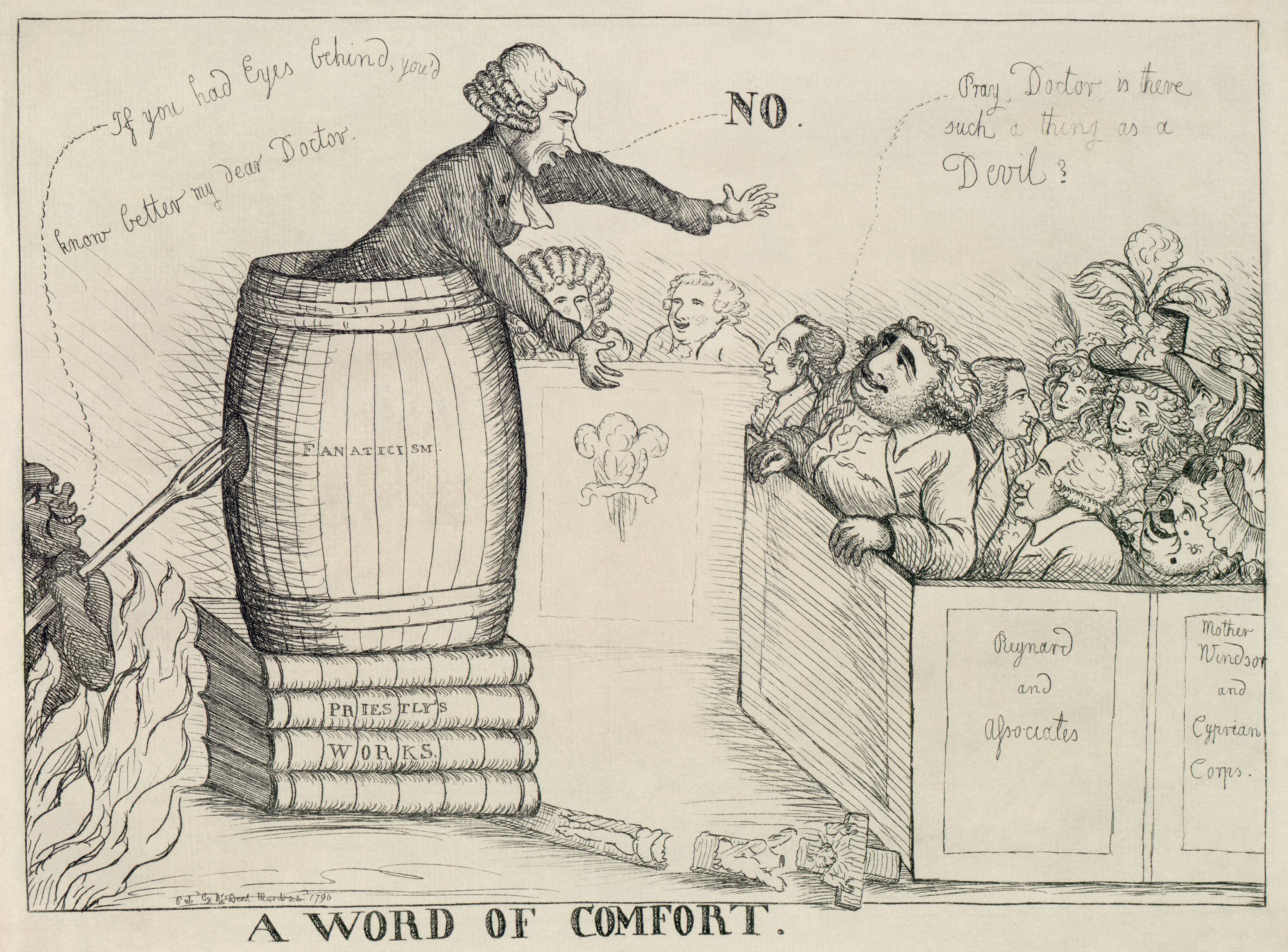

In 1787, 1789 and 1790, Dissenters again tried to repeal the

In 1787, 1789 and 1790, Dissenters again tried to repeal the Test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

and Corporation Acts. Although initially it looked as if they might succeed, by 1790, with the fears of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

looming in the minds of many members of Parliament, few were swayed by Charles James Fox's arguments for equal rights. Political cartoons, one of the most effective and popular media of the time, skewered the Dissenters and Priestley specifically. In the midst of these trying times, it was the betrayal of William Pitt and Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_ NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style"> ...

that most angered Priestley and his friends; they had expected the two men's support and instead both argued vociferously against the repeal. Priestley wrote a series of ''Letters to William Pitt'' and ''Letters to Burke'' in an attempt to persuade them otherwise, but to no avail. These publications unfortunately also inflamed the populace against him.

In its propaganda against the "radicals," Pitt's administration argued that Priestley and other Dissenters wanted to overthrow the government. Dissenters who had supported the French revolution came under increasing suspicion as skepticism over the revolution's benefits and ideals grew. When in 1790 Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer, pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the French ...

, the other leading Dissenting minister in Britain at the time, gave a rousing sermon supporting the French revolutionaries and comparing them to English revolutionaries of 1688, Burke responded with his famous ''Reflections on the Revolution in France

''Reflections on the Revolution in France'' is a political pamphlet written by the Irish statesman Edmund Burke and published in November 1790. It is fundamentally a contrast of the French Revolution to that time with the unwritten British Const ...

''. Priestley rushed to the defense of his friend and of the revolutionaries, publishing one of the many responses, along with Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

and Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

, that became part of the " Revolution Controversy." Paradoxically, it is Burke, the secular statesman, who argued against science and maintained that religion should be the basis of civil society while Priestley, the Dissenting minister, argued that religion could not provide the basis for society and should be restricted to one's private life.

Political adviser to Lord Shelburne

Priestley also served as a kind of political adviser to Lord Shelburne while he working for him as a tutor and librarian; he gathered information for him on parliamentary issues and served as a conduit of information for Dissenting and American interests. Priestley published several political works during these years, most of which were focused on the rights of dissenters, such as ''An Address to Protestant Dissenters . . . on the Approaching Election of Members of Parliament'' (1774). This pamphlet was published anonymously and Schofield calls it "the most outspoken of anything he ever wrote." Priestley called on Dissenters to vote against those in Parliament who had, by refusing to repeal the Test and Corporation Acts, denied them their rights. He wrote a second part dedicated to defending the rebelling American colonists at the behest ofBenjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

and John Fothergill. The pamphlets created a stir throughout Britain but the results of the election did not favor Shelburne's party.

Materialist philosopher and theologian

In a series of five major metaphysical works, all written between 1774 and 1778, Priestley laid out hismaterialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

view of the world and tried "to defend Christianity by making its metaphysical framework more intelligible," even though such a position "entailed denial of free will and the soul."Tapper, 316. The first major work to address these issues was ''The Examination of Dr. Reid's Inquiry ... Dr. Beattie's Essay ... and Dr. Oswald's Appeal'' (1774). He challenged Scottish common-sense philosophy, which claimed that "common sense" trumped reason in matters of religion. Relying on Locke and Hartley's

Hartley's is a brand of marmalades, jams and jellies, originally from the United Kingdom, which is manufactured at Histon, Cambridgeshire. The brand was formerly owned by Premier Foods, until it was sold along with the factory in Histon to Hain C ...

associationism

Associationism is the idea that mental process

Cognition refers to "the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and pr ...

, he argued strenuously against Reid's theory of mind

In psychology, theory of mind refers to the capacity to understand other people by ascribing mental states to them (that is, surmising what is happening in their mind). This includes the knowledge that others' mental states may be different fro ...

and maintained that ideas did not have to resemble their referents in the world; ideas for Priestley were not pictures in the mind but rather causal associations. From these arguments, Priestley concluded that "ideas and objects must be of the same substance," a radically materialist view at the time. The book was popular and readers of all persuasions read it. Charles Lamb

Charles Lamb (10 February 1775 – 27 December 1834) was an English essayist, poet, and antiquarian, best known for his ''Essays of Elia'' and for the children's book ''Tales from Shakespeare'', co-authored with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764–18 ...

wrote to Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poe ...

, recommending "that clear, strong, humorous, most entertaining piece of reasoning" and Priestley heard rumors that even Hume had read the work and "declared that the manner of the work was proper, as the argument was unanswerable."

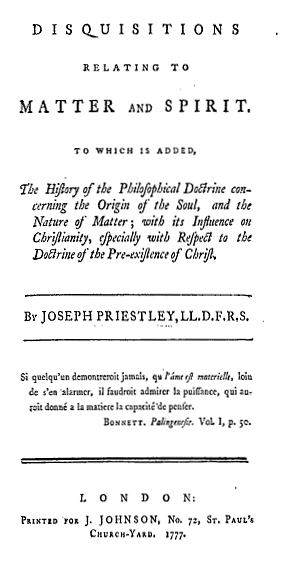

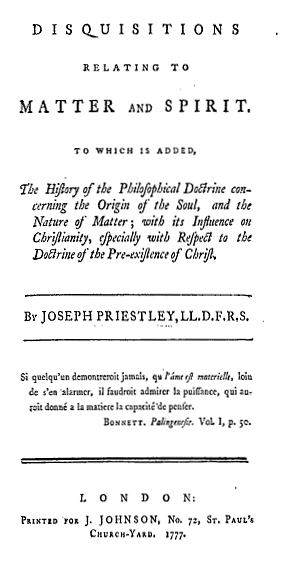

When arguing for materialism in his ''Examination'' Priestley strongly suggested that there was no mind-body duality. Such opinions shocked and angered many of his readers and reviewers who believed that for the

When arguing for materialism in his ''Examination'' Priestley strongly suggested that there was no mind-body duality. Such opinions shocked and angered many of his readers and reviewers who believed that for the soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun ''soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest attes ...

to exist, there had to be a mind-body duality. In order to clarify his position he wrote '' Disquisitions relating to Matter and Spirit'' (1777), which claimed that both "matter" and "force" are active, and therefore that objects in the world and the mind must be made of the same substance. Priestley also argued that discussing the soul was impossible because it is made of a divine substance and humanity cannot gain access to the divine. He therefore denied the materialism of the soul while simultaneously claiming its existence. Although he buttressed his arguments with familiar scholarship and ancient authorities, including scripture, he was labeled an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

. At least a dozen hostile refutations of the work were published by 1782.

Priestley continued this series of arguments in ''The Doctrine of Philosophical Necessity Illustrated

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

'' (1777); the text was designed as an "appendix" to the ''Disquisitions'' and "suggests that materialism and determinism are mutually supporting." Priestley explicitly stated that humans had no free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to actio ...

: "all things, past, present, and to come, are precisely what the Author of nature really intended them to be, and has made provision for." His notion of "philosophical necessity," which he was the first to claim was consonant with Christianity, at times resembles absolute determinism; it is based on his understanding of the natural world and theology: like the rest of nature, man's mind is subject to the laws of causation, but because a benevolent God has created these laws, Priestley argued, the world as a whole will eventually be perfected. He argued that the associations made in a person's mind were a ''necessary'' product of their lived experience because Hartley's theory of associationism was analogous to natural laws such as gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

. Priestley contends that his necessarianism can be distinguished from fatalism

Fatalism is a family of related philosophical doctrines that stress the subjugation of all events or actions to fate or destiny, and is commonly associated with the consequent attitude of resignation in the face of future events which are thou ...

and predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

because it relies on natural law. Isaac Kramnick points out the paradox of Priestley's positions: as a reformer, he argued that political change was essential to human happiness and urged his readers to participate, but he also claimed in works such as ''Philosophical Necessity'' that humans have no free will. ''Philosophical Necessity'' influenced the 19th-century utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

s John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

and Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest" ...

, who were drawn to its determinism. Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

, entranced by Priestley's determinism but repelled by his reliance on observed reality, created a transcendental version of determinism that he claimed allowed liberty to the mind and soul.

In the last of his important books on metaphysics, ''Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever

''Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever'' (1780) is a multi-volume series of books on metaphysics by eighteenth-century British polymath Joseph Priestley.

Priestley wrote a series of important metaphysics works during the years he spent serving ...

'' (1780), Priestley continues to defend his thesis that materialism and determinism can be reconciled with a belief in a God. The seed for this book had been sown during his trip to Paris with Shelburne. Priestley recalled in his ''Memoirs'':

As I chose on all occasions to appear as a Christian, I was told by some of them 'philosophes''">philosophes.html" ;"title="'philosophes">'philosophes'' that I was the only person they had ever met with, of whose understanding they had any opinion, who professed to believe Christianity. But on interrogating them on the subject, I soon found that they had given no proper attention to it, and did not really know what Christianity was ... Having conversed so much with unbelievers at home and abroad, I thought I should be able to combat their prejudices with some advantage, and with this view I wrote ... the first part of my 'Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever', in proof of the doctrines of a God and a providence, and ... a second part, in defence of the evidences [sic] of Christianity.The text addresses those whose faith is shaped by books and fashion; Priestley draws an analogy between the skepticism of educated men and the credulity of the masses. He again argues for the existence of God using what Schofield calls "the classic argument from design ... leading from the necessary existence of a creator-designer to his self-comprehension, eternal existence, infinite power, omnipresence, and boundless benevolence." In the three volumes, Priestley discusses, among many other works, Baron d'Holbach's ''

Systeme de la Nature

''The System of Nature or, the Laws of the Moral and Physical World'' (French: ) is a work of philosophy by Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach (1723–1789).

Overview

The work was originally published under the name of Jean-Baptiste de Mirabaud, ...

'', often called the "bible of atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

." He claimed that d'Holbach's "energy of nature," though it lacked intelligence or purpose, was really a description of God. Priestley believed that David Hume's style in the ''Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion

''Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion'' is a philosophical work by the Scottish philosopher David Hume, first published in 1779. Through dialogue, three philosophers named Demea, Philo, and Cleanthes debate the nature of God's existence. Whet ...

'' (1779) was just as dangerous as its ideas; he feared the open-endedness of the Humean dialogue.Schofield, Vol. 2, 37–42.

Notes

Bibliography

For a complete bibliography of Priestley's writings, seelist of works by Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) was a British natural philosopher, Dissenting clergyman, political theorist, theologian, and educator. He is best known for his discovery, simultaneously with Antoine Lavoisier, of oxygen gas.

A member of marginal ...

.

*Fitzpatrick Martin. "Heretical Religion and Radical Political Ideas in Late Eighteenth-Century England." ''The Transformation of Political Culture: England and Germany in the Late Eighteenth Century''. Ed. Eckhart Hellmuth. Oxford: ?, 1990.

*Fitzpatrick, Martin. "Joseph Priestley and the Cause of Universal Toleration." ''The Price-Priestley Newsletter'' 1 (1977): 3–30.

*Garrett, Clarke. "Joseph Priestley, the Millennium, and the French Revolution." ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' 34.1 (1973): 51–66.

*Gibbs, F. W. ''Joseph Priestley: Adventurer in Science and Champion of Truth''. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965.

*Haakonssen, Knud, ed. ''Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in Eighteenth-Century Britain''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. .

*Jackson, Joe, ''A World on Fire: A Heretic, An Aristocrat and the Race to Discover Oxygen''. New York: Viking, 2005. .

*Kramnick, Isaac. "Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley's Scientific Liberalism." ''Journal of British Studies'' 25 (1986): 1–30.

*McEvoy, John G. "Enlightenment and dissent in science: Joseph Priestley and the limits of theoretical reasoning." ''Enlightenment and Dissent'' 2 (1983): 47–68; 57–8.

*McLachlan, John. ''Joseph Priestley Man of Science 1733–1804: An Iconography of a Great Yorkshireman''. Braunton and Devon: Merlin Books Ltd., 1983. .

*Philip, Mark. "Rational Religion and Political Radicalism." ''Enlightenment and Dissent'' 4 (1985): 35–46.

*Schofield, Robert E. ''The Enlightenment of Joseph Priestley: A Study of his Life and Work from 1733 to 1773''. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997. .

*Schofield, Robert E. ''The Enlightened Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1773 to 1804''. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004. .

*Sheps, Arthur. "Joseph Priestley's Time ''Charts'': The Use and Teaching of History by Rational Dissent in late Eighteenth-Century England." ''Lumen'' 18 (1999): 135–154.

*Tapper, Alan. "Joseph Priestley." ''Dictionary of Literary Biography

The ''Dictionary of Literary Biography'' is a specialist biographical dictionary dedicated to literature. Published by Gale, the 375-volume setRogers, 106. covers a wide variety of literary topics, periods, and genres, with a focus on American an ...

'' 252: ''British Philosophers 1500–1799''. Eds. Philip B. Dematteis and Peter S. Fosl. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002.

*Thorpe, T.E. ''Joseph Priestley''. London: J. M. Dent, 1906.

*Uglow, Jenny. ''The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World''. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. .

External links

The Joseph Priestley Society

– Comprehensive site which includes a bibliography, links to related sites, images, information on manuscript collections, and other helpful information.

Full-text links

A General History of the Christian Church

(full text from google books)

A History of the Corruptions of Christianity

(full text from google books)

The Doctrines of Heathen Philosophy compared with those of Revelation

(full text from google books)

Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion, Vol. 1 of 2

(full text from google books)

Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion, Vol. 2 of 2

(full text from google books)

An History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ, Vol. 1

(full text from google books)

An History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ, Vol. 2

(full text from google books)

An History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ, Vol. 3

(full text from google books)

An History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ, Vol. 4

(full text from google books)

A Free Address to Protestant Dissenters

(full text from google books) {{Joseph Priestley English Christian theologians Christian theological movements Priestley, Joseph and Dissent Determinism English Unitarians Materialists Eponymous political ideologies