Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the

Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professor of architecture at the

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

and an official architect to the

Office of Works

The Office of Works was established in the England, English Royal Household, royal household in 1378 to oversee the building and maintenance of the royal castles and residences. In 1832 it became the Works Department forces within the Office of W ...

. He received a

knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

in 1831.

His best-known work was the

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

(his work there is largely destroyed), a building which had a widespread effect on commercial architecture. He also designed

Dulwich Picture Gallery

Dulwich Picture Gallery is an art gallery in Dulwich, South London, which opened to the public in 1817. It was designed by Regency architect Sir John Soane using an innovative and influential method of illumination. Dulwich is the oldest pub ...

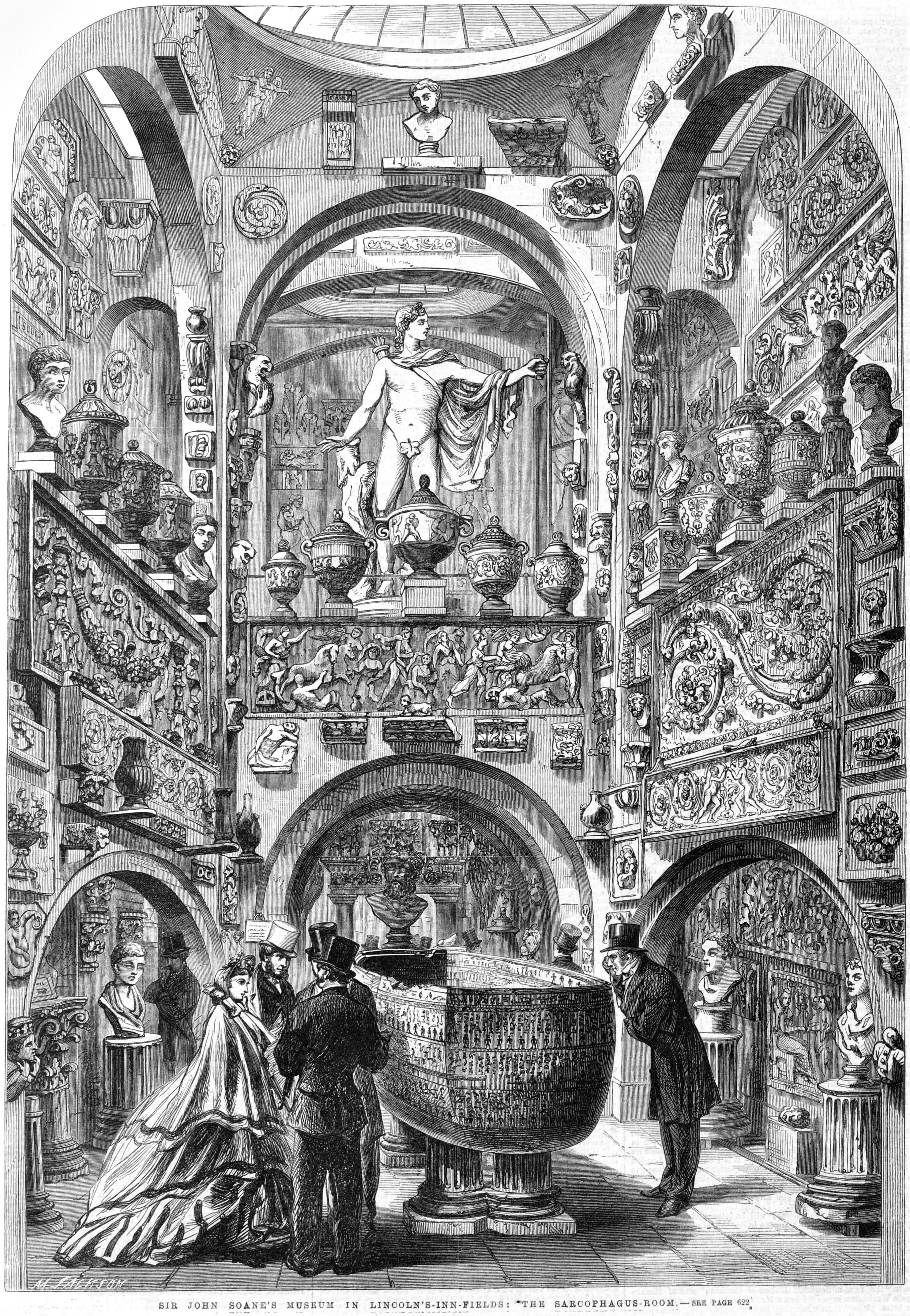

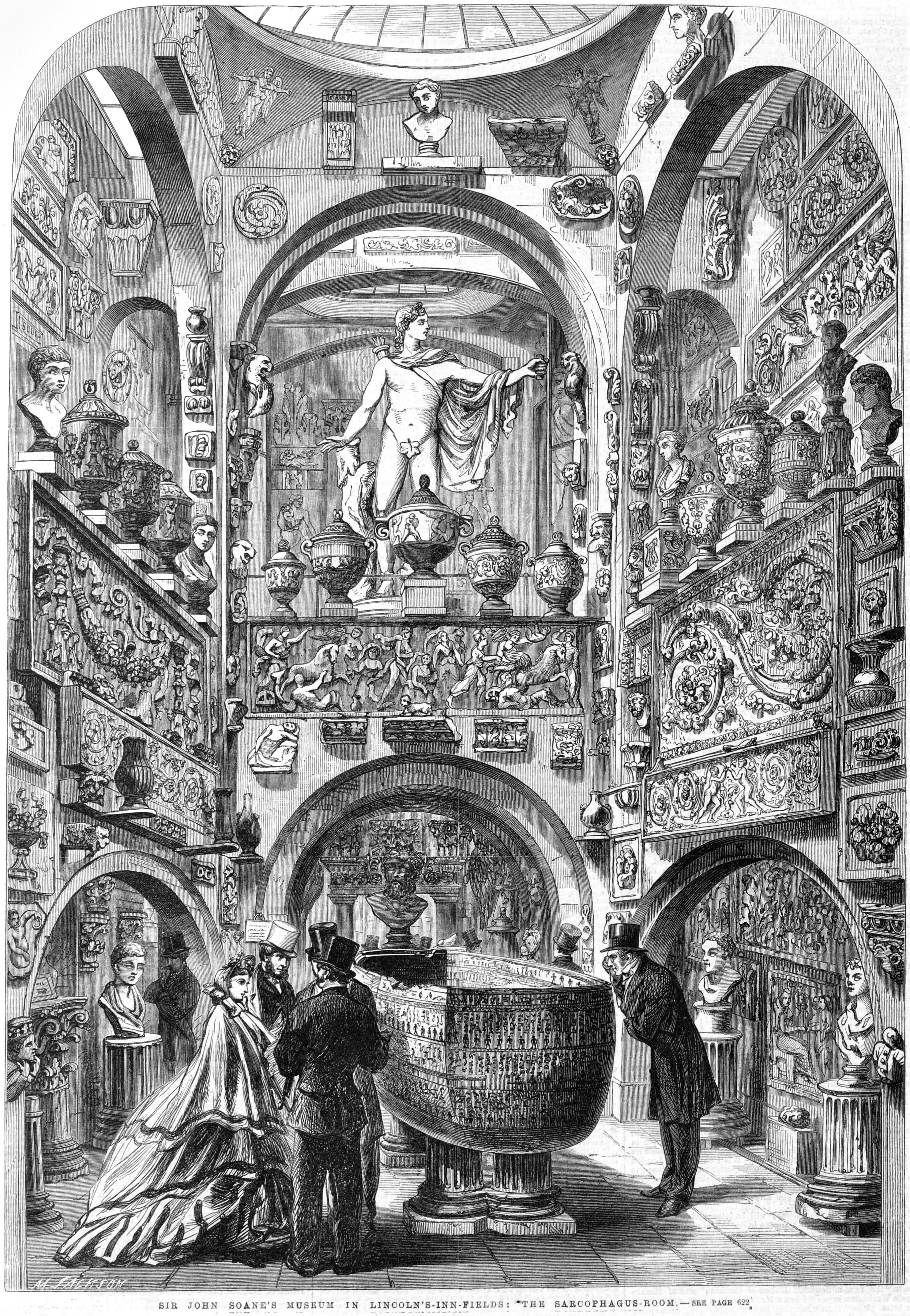

, which, with its top-lit galleries, was a major influence on the planning of subsequent art galleries and museums. His main legacy is

the eponymous museum in

Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is the largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a long series of entrepreneurs who took a hand in develo ...

in his former home and office, designed to display the art works and architectural artefacts that he collected during his lifetime. The museum is described in the ''Oxford Dictionary of Architecture'' as "one of the most complex, intricate, and ingenious series of interiors ever conceived".

[Curl, 1999, p. 622]

Background and training

Soane was born in

Goring-on-Thames

Goring-on-Thames (or Goring) is a village and civil parish on the River Thames in South Oxfordshire, England, about south of Wallingford and northwest of Reading. It had a population of 3,187 in the 2011 census, put at 3,335 in 2019. Goring ...

on 10 September 1753. He was the second surviving son of John Soan and his wife Martha. The 'e' was added to the surname by the architect in 1784 on his marriage. His father was a builder or bricklayer, and died when Soane was fourteen in April 1768. He was educated in nearby

Reading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of Letter (alphabet), letters, symbols, etc., especially by Visual perception, sight or Somatosensory system, touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process invo ...

in a private school run by William Baker. After his father's death Soane's family moved to nearby

Chertsey

Chertsey is a town in the Borough of Runnymede, Surrey, England, south-west of central London. It grew up round Chertsey Abbey, founded in 666 CE, and gained a market charter from Henry I. A bridge across the River Thames first appeared in the ...

to live with Soane's brother William, 12 years his elder.

William Soan introduced his brother to James Peacock,

a surveyor who worked with

George Dance the Younger

George Dance the Younger RA (1 April 1741 – 14 January 1825) was an English architect and surveyor as well as a portraitist.

The fifth and youngest son of the architect George Dance the Elder, he came from a family of architects, artists a ...

. Soane began his training as an architect age 15 under George Dance the Younger and joining the architect at his home and office in the

City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

at the corner of Moorfields and Chiswell Street.

[Darley, 1999, pp. 1–21] Dance was a founding member of the

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

and doubtless encouraged Soane to join the schools there on 25 October 1771 as they were free.

[Richardson & Stevens, 1999, p. 86] There he would have attended the architecture lectures delivered by

Thomas Sandby

Thomas Sandby (1721 – 25 June 1798) was an English draughtsman, watercolour artist, architect and teacher. In 1743 he was appointed private secretary to the Duke of Cumberland, who later appointed him Deputy Ranger of Windsor Great Park, wh ...

and the lectures on

perspective delivered by

Samuel Wale.

Dance's growing family was probably the reason that in 1772 Soane continued his education by joining the household and office of

Henry Holland.

He recalled later that he was 'placed in the office of an eminent builder in extensive practice where I had every opportunity of surveying the progress of building in all its different varieties, and of attaining the knowledge of measuring and valuing artificers' work'. During his studies at the Royal Academy, he was awarded the Academy's silver medal on 10 December 1772 for a measured drawing of the facade of the

Banqueting House, Whitehall

The Banqueting House, Whitehall, is the grandest and best known survivor of the architectural genre of banqueting houses, constructed for elaborate entertaining. It is the only remaining component of the Palace of Whitehall, the residence of E ...

, which was followed by the gold medal on 10 December 1776 for his design of a ''Triumphal Bridge''. He received a travelling scholarship in December 1777 and exhibited at the Royal Academy a design for a

Mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be consid ...

for his friend and fellow student James King, who had drowned in 1776 on a boating trip to

Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

. Soane, a non-swimmer, was going to be with the party but decided to stay home and work on his design for a ''Triumphal Bridge''.

By 1777, Soane was living in his own accommodation in Hamilton Street. In 1778 he published his first book ''Designs in Architecture''.

He sought advice from Sir

William Chambers on what to study: ''"Always see with your own eyes ...

oumust discover their true beauties, and the secrets by which they are produced."'' Using his travelling scholarship of £60 per annum for three years, plus an additional £30 travelling expenses for each leg of the journey, Soane set sail on his

Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tuto ...

, his ultimate destination being Rome, at 5:00 am, 18 March 1778.

Grand Tour

His travelling companion was

Robert Furze Brettingham; they travelled via Paris, where they visited

Jean-Rodolphe Perronet

Jean-Rodolphe Perronet (27 October 1708 – 27 February 1794) was a French architect and structural engineer, known for his many stone arch bridges. His best known work is the Pont de la Concorde (1787).

Early life

Perronet was born in Suresn ...

, and then went on to the

Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 19 ...

on 29 March. They finally reached Rome on 2 May 1778. Soane wrote home, "my attention is entirely taken up in the seeing and examining the numerous and inestimable remains of Antiquity ...". His first dated drawing is 21 May of the church of

Sant'Agnese fuori le mura

The church of Saint Agnes Outside the Walls ( it, Sant'Agnese fuori le mura) is a titulus church, minor basilica in Rome, on a site sloping down from the Via Nomentana, which runs north-east out of the city, still under its ancient name. What a ...

(Saint Agnes Outside the Walls). His former classmate, the architect

Thomas Hardwick

Thomas Hardwick (1752–1829) was an English architect and a founding member of the Architects' Club in 1791.

Early life and career

Hardwick was born in Brentford, Middlesex the son of a master mason turned architect also named Thomas Hard ...

, returned to Rome in June from

Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

. Hardwick and Soane would produce a series of measured drawings and ground plans of Roman buildings together. During the summer they visited

Hadrian's Villa

Hadrian's Villa ( it, Villa Adriana) is a UNESCO World Heritage Site comprising the ruins and archaeological remains of a large villa complex built c. AD 120 by Roman Emperor Hadrian at Tivoli outside Rome. The site is owned by the Republic of ...

and the

Temple of Vesta, Tivoli

The Temple of Vesta is a Roman temple in Tivoli, Italy, dating to the early 1st century BC. Its ruins sit on the acropolis of the city, overlooking the falls of the Aniene that are now included in the Villa Gregoriana.

History

It is not known ...

, whilst back in Rome they investigated the

Colosseum

The Colosseum ( ; it, Colosseo ) is an oval amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, just east of the Roman Forum. It is the largest ancient amphitheatre ever built, and is still the largest standing amphitheatre in the world to ...

. In August Soane was working on a design for a ''British Senate House'' to be submitted for the 1779

Royal Academy summer exhibition

The Summer Exhibition is an open art exhibition held annually by the Royal Academy in Burlington House, Piccadilly in central London, England, during the months of June, July, and August. The exhibition includes paintings, prints, drawings, sc ...

.

[Darley, 1999, p. 27]

In the autumn he met the

Bishop of Derry

The Bishop of Derry is an Episcopal polity, episcopal title which takes its name after the monastic settlement originally founded at Daire Calgach and later known as Daire Colm Cille, Anglicised as Derry. In the Roman Catholic Church it remains a ...

,

Frederick Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol

Frederick Augustus Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol, (1 August 1730 – 8 July 1803), was an 18th-century Anglican prelate.

Elected Bishop of Cloyne in 1767 and translated to the see of Derry in 1768, Hervey served as Lord Bishop of Derry unti ...

, who had built several grand properties for himself.

The Earl presented copies of ''

I quattro libri dell'architettura

''I quattro libri dell'architettura'' (''The Four Books of Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture by the architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580), written in Italian. It was first published in four volumes in 1570 in Venice, illustrated wi ...

'' and ''

De architectura

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture written by the Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, as a guide f ...

'' to Soane. In December the Earl introduced Soane to

Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford

Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford (3 March 1737 – 19 January 1793) was a British politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1761 until 1784 when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Camelford. He was an art connoisseur.

Early life

Pitt w ...

, an acquaintance which would lead eventually to architectural commissions. The Earl persuaded Soane to accompany him to Naples, setting off from Rome on 22 December 1778. On the way they visited

Capua

Capua ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, situated north of Naples, on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History

Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etrusc ...

and the

Palace of Caserta

The Royal Palace of Caserta ( it, Reggia di Caserta ) is a former royal residence in Caserta, southern Italy, constructed by the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies as their main residence as kings of Naples. It is the largest palace erected in Euro ...

, arriving in Naples on 29 December. It was there that Soane met two future clients,

John Patteson and Richard Bosanquet. From Naples Soane made several excursions including to

Pozzuoli

Pozzuoli (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Naples, in the Italian region of Campania. It is the main city of the Phlegrean Peninsula.

History

Pozzuoli began as the Greek colony of ''Dicaearchia'' ( el, Δικα ...

,

Cumae

Cumae ( grc, Κύμη, (Kumē) or or ; it, Cuma) was the first ancient Greek colony on the mainland of Italy, founded by settlers from Euboea in the 8th century BC and soon becoming one of the strongest colonies. It later became a rich Ro ...

and

Pompeii

Pompeii (, ) was an ancient city located in what is now the ''comune'' of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was buried ...

, where he met yet another future client,

Philip Yorke. Soane also attended a performance at

Teatro di San Carlo

The Real Teatro di San Carlo ("Royal Theatre of Saint Charles"), as originally named by the Bourbon monarchy but today known simply as the Teatro (di) San Carlo, is an opera house in Naples, Italy, connected to the Royal Palace and adjacent t ...

and climbed

Mount Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of s ...

. Visiting

Paestum

Paestum ( , , ) was a major ancient Greek city on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). The ruins of Paestum are famous for their three ancient Greek temples in the Doric order, dating from about 550 to 450 BC, whic ...

, Soane was deeply impressed by the Greek temples. Next he visited the

Certosa di Padula

Padula Charterhouse, in Italian Certosa di Padula (or ''Certosa di San Lorenzo di Padula''), is a large Carthusian monastery, or charterhouse, located in the town of Padula, in the Cilento National Park, in Southern Italy. It is a World Herita ...

, then went on to

Eboli

Eboli ( Ebolitano: ) is a town and ''comune'' of Campania, southern Italy, in the province of Salerno.

An agricultural centre, Eboli is known mainly for olive oil and for its dairy products, among which the famous buffalo mozzarella from the ...

and

Salerno

Salerno (, , ; nap, label= Salernitano, Saliernë, ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' in Campania (southwestern Italy) and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after ...

and its cathedral. Later they visited

Benevento

Benevento (, , ; la, Beneventum) is a city and ''comune'' of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill above sea level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino (or Beneventano) and the ...

and

Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the nea ...

. The Earl and Soane left for Rome on 12 March 1779, travelling via Capua,

Gaeta

Gaeta (; lat, Cāiēta; Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a city in the province of Latina, in Lazio, Southern Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The town has played a consp ...

, the

Pontine Marshes

250px, Lake Fogliano, a coastal lagoon in the Pontine Plain

The Pontine Marshes (, also ; it, Agro Pontino , formerly also ''Paludi Pontine''; la, Pomptinus Ager by Titus Livius, ''Pomptina Palus'' (singular) and ''Pomptinae Paludes'' (plu ...

,

Velletri

Velletri (; la, Velitrae; xvo, Velester) is an Italian ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Rome, approximately 40 km to the southeast of the city centre, located in the Alban Hills, in the region of Lazio, central Italy. Neighbouring com ...

, the

Alban Hills

The Alban Hills ( it, Colli Albani) are the caldera remains of a quiescent volcano, volcanic complex in Italy, located southeast of Rome and about north of Anzio. The high Monte Cavo forms a highly visible peak the centre of the caldera, bu ...

and

Lake Albano

Lake Albano (Italian: ''Lago Albano'' or ''Lago di Castel Gandolfo'') is a small volcanic crater lake in the Alban Hills of Lazio, at the foot of Monte Cavo, southeast of Rome. Castel Gandolfo, overlooking the lake, is the site of the Papal Pa ...

, and

Castel Gandolfo

Castel Gandolfo (, , ; la, Castrum Gandulphi), colloquially just Castello in the Castelli Romani dialects, is a town located southeast of Rome in the Lazio region of Italy. Occupying a height on the Alban Hills overlooking Lake Albano, Castel Ga ...

. Back in Rome they visited the

Palazzo Barberini

The Palazzo Barberini ( en, Barberini Palace) is a 17th-century palace in Rome, facing the Piazza Barberini in Rione Trevi. Today, it houses the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, the main national collection of older paintings in Rome.

History

...

and witnessed the celebrations of

Holy Week

Holy Week ( la, Hebdomada Sancta or , ; grc, Ἁγία καὶ Μεγάλη Ἑβδομάς, translit=Hagia kai Megale Hebdomas, lit=Holy and Great Week) is the most sacred week in the liturgical year in Christianity. In Eastern Churches, w ...

. Shortly after, the Earl and his family departed for home, followed a few weeks later by Thomas Hardwick.

It was then that Soane met

Maria Hadfield (they became lifelong friends) and

Thomas Banks

Thomas Banks (29 December 1735 – 2 February 1805) was an important 18th-century English sculptor.

Life

The son of William Banks, a Surveyor (surveying), surveyor who was land steward to the Duke of Beaufort, he was born in London. He was e ...

. Soane was now fairly fluent in the Italian language, a sign of his growing confidence. A party, including

Thomas Bowdler

Thomas Bowdler, Royal College of Physicians, LRCP, Royal Society, FRS (; 11 July 1754 – 24 February 1825) was an English physician known for publishing ''The Family Shakespeare'', an expurgated edition of William Shakespeare's plays edited by ...

,

Rowland Burdon, John Patteson, John Stuart and Henry Grewold Lewis, decided to visit

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and paid for Soane to accompany them as a draughtsman.

[Darley, 1999, p. 43] The party headed for Naples on 11 April, where on 21 April they caught a Swedish ship to

Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan ...

. Soane visited the

Villa Palagonia

The Villa Palagonia is a patrician villa in Bagheria, 15 km from Palermo, in Sicily, southern Italy. The villa itself, built from 1715 by the architect Tommaso Napoli with the help of Agatino Daidone, is one of the earliest examples of ...

, which made a deep impact on him. Influenced by the account of the Villa in his copy of

Patrick Brydone's ''Tour through Sicily and Malta'', Soane savoured the "Prince of Palagonia's Monsters ... nothing more than the most extravagant caricatures in stone", but more significantly seems to have been inspired by the Hall of Mirrors to introduce similar effects when he came to design the interiors of his own house in Lincoln's Inn Fields. Leaving Palermo from where the party split, Stuart and Bowdler going off together. The rest headed for

Segesta

Segesta ( grc-gre, Ἔγεστα, ''Egesta'', or , ''Ségesta'', or , ''Aígesta''; scn, Siggésta) was one of the major cities of the Elymians, one of the three indigenous peoples of Sicily. The other major cities of the Elymians were Eryx a ...

,

Trapani

Trapani ( , ; scn, Tràpani ; lat, Drepanum; grc, Δρέπανον) is a city and municipality (''comune'') on the west coast of Sicily, in Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Trapani. Founded by Elymians, the city is still an impor ...

,

Selinunte

Selinunte (; grc, Σελῑνοῦς, Selīnoûs ; la, Selīnūs , ; scn, Silinunti ) was a rich and extensive ancient Greek city on the south-western coast of Sicily in Italy. It was situated between the valleys of the Cottone and Modion ...

and

Agrigento

Agrigento (; scn, Girgenti or ; grc, Ἀκράγας, translit=Akrágas; la, Agrigentum or ; ar, كركنت, Kirkant, or ''Jirjant'') is a city on the southern coast of Sicily, Italy and capital of the province of Agrigento. It was one of ...

, exposing Soane to

Ancient Greek architecture

Ancient Greek architecture came from the Greek-speaking people (''Hellenic'' people) whose culture flourished on the Greek mainland, the Peloponnese, the Aegean Islands, and in colonies in Anatolia and Italy for a period from about 900 BC unti ...

. From Agrigento the party headed for

Licata

Licata (, ; grc, Φιντίας, whence la, Phintias or ''Plintis''), formerly also Alicata (), is a city and ''comune'' located on the south coast of Sicily, at the mouth of the Salso River (the ancient ''Himera''), about midway between Ag ...

, where they sailed for

Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and

Valletta

Valletta (, mt, il-Belt Valletta, ) is an Local councils of Malta, administrative unit and capital city, capital of Malta. Located on the Malta (island), main island, between Marsamxett Harbour to the west and the Grand Harbour to the east, i ...

returning on 2 June, to

Syracuse, Sicily

Syracuse ( ; it, Siracusa ; scn, Sarausa ), ; grc-att, wikt:Συράκουσαι, Συράκουσαι, Syrákousai, ; grc-dor, wikt:Συράκοσαι, Συράκοσαι, Syrā́kosai, ; grc-x-medieval, Συρακοῦσαι, Syrakoûs ...

. Moving on to

Catania

Catania (, , Sicilian and ) is the second largest municipality in Sicily, after Palermo. Despite its reputation as the second city of the island, Catania is the largest Sicilian conurbation, among the largest in Italy, as evidenced also by ...

and

Palazzo Biscari

The Palazzo Biscari is a monumental private palace located on Via Museo Biscari in Catania, Sicily, southern Italy. The highly decorative interiors are open for guided tours, and used for social and cultural events.

History and Description

Afte ...

then

Mount Etna

Mount Etna, or simply Etna ( it, Etna or ; scn, Muncibbeḍḍu or ; la, Aetna; grc, Αἴτνα and ), is an active stratovolcano on the east coast of Sicily, Italy, in the Metropolitan City of Catania, between the cities of Messina a ...

,

Taormina

Taormina ( , , also , ; scn, Taurmina) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Messina, on the east coast of the island of Sicily, Italy. Taormina has been a tourist destination since the 19th century. Its beaches on ...

,

Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

and the

Lepari Islands. They were back in Naples by 2 July where Soane purchased books and prints, visiting

Sorrento

Sorrento (, ; nap, Surriento ; la, Surrentum) is a town overlooking the Bay of Naples in Southern Italy. A popular tourist destination, Sorrento is located on the Sorrentine Peninsula at the south-eastern terminus of the Circumvesuviana rail ...

before returning to Rome. Shortly after, John Patterson returned to England via Vienna, from where he sent Soane the first six volumes of ''

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

''The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman'', also known as ''Tristram Shandy'', is a novel by Laurence Sterne, inspired by ''Don Quixote''. It was published in nine volumes, the first two appearing in 1759, and seven others followin ...

'', delivered by

Antonio Salieri

Antonio Salieri (18 August 17507 May 1825) was an Italian classical composer, conductor, and teacher. He was born in Legnago, south of Verona, in the Republic of Venice, and spent his adult life and career as a subject of the Habsburg monarchy ...

.

[Darley, 1999, p. 49]

In Rome Soane's circle now included

Henry Tresham

Henry Tresham (c.1751 – 17 June 1814) was an Irish-born British historical painter active in London in the late 18th century. He spent some time in Rome early in his career, and was professor of painting at the Royal Academy of Arts in London ...

,

Thomas Jones (artist)

Thomas Jones (26 September 1742 – 29 April 1803) was a Welsh landscape painter. He was a pupil of Richard Wilson and was best known in his lifetime as a painter of Welsh and Italian landscapes in the style of his master. However, Jones's rep ...

and

Nathaniel Marchant.

Soane continued to study the buildings of Rome, including the

Basilica of St. John Lateran

The Archbasilica Cathedral of the Most Holy Savior and of Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist in the Lateran ( it, Arcibasilica del Santissimo Salvatore e dei Santi Giovanni Battista ed Evangelista in Laterano), also known as the Papa ...

. Soane and Rowland Burdon set out in August for

Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

. Their journey included visits to

Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic S ...

,

Rimini

Rimini ( , ; rgn, Rémin; la, Ariminum) is a city in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy and capital city of the Province of Rimini. It sprawls along the Adriatic Sea, on the coast between the rivers Marecchia (the ancient ''Ariminu ...

,

Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nat ...

,

Parma

Parma (; egl, Pärma, ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmigiano-Reggiano, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,292 ...

and its Accademia,

Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

,

Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Northern Italy, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city Comune, municipality in the region and the ...

,

Vicenza

Vicenza ( , ; ) is a city in northeastern Italy. It is in the Veneto region at the northern base of the ''Monte Berico'', where it straddles the Bacchiglione River. Vicenza is approximately west of Venice and east of Milan.

Vicenza is a th ...

and its buildings by

Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be one of th ...

,

Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

, the

Brenta (river)

The Brenta is an Italian river that runs from Trentino to the Adriatic Sea just south of the Venetian lagoon in the Veneto region, in the north-east of Italy.

During the Roman era, it was called Medoacus (Ancient Greek: ''Mediochos'', ''Μηδ� ...

with its villas by Palladio,

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. Then back to Bologna where Soane copied designs for completing the west front of

San Petronio Basilica

The Basilica of San Petronio is a minor basilica and church of the Archdiocese of Bologna located in Bologna, Emilia Romagna, northern Italy. It dominates Piazza Maggiore. The basilica is dedicated to the patron saint of the city, Saint Petronius ...

including ones by Palladio,

Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola

Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola ( , , ; 1 October 15077 July 1573), often simply called Vignola, was one of the great Italian architects of 16th century Mannerism. His two great masterpieces are the Villa Farnese at Caprarola and the Jesuits' Churc ...

and

Baldassare Peruzzi

Baldassare Tommaso Peruzzi (7 March 1481 – 6 January 1536) was an Italian architect and painter, born in a small town near Siena (in Ancaiano, ''frazione'' of Sovicille) and died in Rome. He worked for many years with Bramante, Raphael, and la ...

. Then to

Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

and the

Accademia delle Arti del Disegno

The Accademia delle Arti del Disegno ("Academy of the Arts of Drawing") is an academy of artists in Florence, Italy. Founded as Accademia e Compagnia delle Arti del Disegno ("Academy and Company of the Arts of Drawing") on 13 January 1563 by ...

of which he was later, in January 1780 elected a member; then returned to Rome.

Soane continued his study of buildings, including

Villa Lante

Villa Lante is a Mannerism, Mannerist garden of surprise in Bagnaia, Viterbo, Bagnaia, Viterbo, central Italy, attributed to Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola.

Villa Lante did not become so known until it passed to Ippolito Lante Montefeltro della Rovere ...

,

Palazzo Farnese

Palazzo Farnese () or Farnese Palace is one of the most important High Renaissance List of palaces in Italy#Rome, palaces in Rome. Owned by the Italian Republic, it was given to the French government in 1936 for a period of 99 years, and cur ...

,

Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne

The Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne is a Renaissance palace in Rome, Italy.

History

The palace was designed by Baldassarre Peruzzi in 1532–1536 on a site of three contiguous palaces owned by the old Roman Massimo family and built after arson de ...

, the

Capitoline Museums

The Capitoline Museums (Italian: ''Musei Capitolini'') are a group of art and archaeological museums in Piazza del Campidoglio, on top of the Capitoline Hill in Rome, Italy. The historic seats of the museums are Palazzo dei Conservatori and Pala ...

and the

Villa Albani

The Villa Albani (later Villa Albani-Torlonia) is a villa in Rome, built on the Via Salaria for Cardinal Alessandro Albani. It was built between 1747 and 1767 by the architect Carlo Marchionni in a project heavily influenced by otherssuch as G ...

. That autumn he met

Henry Bankes

Henry Bankes (1757–1834) was an English politician and author.

Life

Bankes was the only surviving son of Henry Bankes and the great-grandson of Sir John Bankes, chief justice of the common pleas in the time of Charles I.

Bankes was educated ...

, Soane prepared plans for the Banke's house

Kingston Lacy, but these came to nothing. Early in 1780 Frederick Augustus Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol wrote to Soane offering him various architectural commissions, Soane decided to return to England and began to organise his return journey. He left Rome on 19 April 1780, travelling with the Reverend George Holgate and his pupil Michael Pepper. They visited the

Villa Farnese

The Villa Farnese, also known as Villa Caprarola, is a pentagonal mansion in the town of Caprarola in the province of Viterbo, Northern Lazio, Italy, approximately north-west of Rome. This villa should not be confused with the Palazzo Farnese a ...

, then on to

Siena

Siena ( , ; lat, Sena Iulia) is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena.

The city is historically linked to commercial and banking activities, having been a major banking center until the 13th and 14th centuri ...

. Then Florence where they visited the

Palazzo Pitti

The Palazzo Pitti (), in English sometimes called the Pitti Palace, is a vast, mainly Renaissance, palace in Florence, Italy. It is situated on the south side of the River Arno, a short distance from the Ponte Vecchio. The core of the present ...

,

Uffizi

The Uffizi Gallery (; it, Galleria degli Uffizi, italic=no, ) is a prominent art museum located adjacent to the Piazza della Signoria in the Historic Centre of Florence in the region of Tuscany, Italy. One of the most important Italian museums ...

,

Santo Spirito, Florence

The Basilica di Santo Spirito ("Basilica of the Holy Spirit") is a church in Florence, Italy. Usually referred to simply as Santo Spirito, it is located in the Oltrarno quarter, facing the square with the same name. The interior of the building � ...

,

Giotto's Campanile

Giotto's Campanile (, also , ) is a free-standing campanile that is part of the complex of buildings that make up Florence Cathedral on the Piazza del Duomo in Florence, Italy.

Standing adjacent to the Basilica of Santa Maria del Fiore and the ...

and other sites.

Performing at the

Teatro della Pergola

The Teatro della Pergola is an historic opera house in Florence, Italy. It is located in the centre of the city on the Via della Pergola, from which the theatre takes its name. It was built in 1656 under the patronage of Cardinal Gian Carlo de' Med ...

was

Nancy Storace

Anna (or Ann) Selina Storace (; 27 October 176524 August 1817), known professionally as Nancy Storace, was an English operatic soprano. The role of Susanna in Mozart's ''Le nozze di Figaro'' was written for and first performed by her.

Born in ...

with whom Soane formed a lifelong friendship. Their journey continued on via Bologna, Padua, Vicenza, Verona,

Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard language, Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and ''comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture ...

where he sketched

Palazzo del Te

or is a palace in the suburbs of Mantua, Italy. It is a fine example of the mannerist style of architecture, and the acknowledged masterpiece of Giulio Romano. Although formed in Italian, the usual name in English of Palazzo del Te is not that ...

, Parma,

Piacenza

Piacenza (; egl, label= Piacentino, Piaṡëinsa ; ) is a city and in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy, and the capital of the eponymous province. As of 2022, Piacenza is the ninth largest city in the region by population, with over ...

. Milan where he attended

La Scala

La Scala (, , ; abbreviation in Italian of the official name ) is a famous opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the ' (New Royal-Ducal Theatre alla Scala). The premiere performan ...

, the theatre was a growing interest,

Lake Como

Lake Como ( it, Lago di Como , ; lmo, label=Western Lombard, Lagh de Còmm , ''Cómm'' or ''Cùmm'' ), also known as Lario (; after the la, Larius Lacus), is a lake of glacial origin in Lombardy, Italy. It has an area of , making it the thir ...

from where they began their crossing of the

Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

via the

Splügen Pass

The Splügen Pass (german: Splügenpass; it, Passo dello Spluga; rm, Pass dal Spleia ) is an Alpine mountain pass of the Lepontine Alps. It connects the Swiss, Grisonian Splügen to the north below the pass with the Italian Chiavenna to the ...

. They then passed on to

Zurich,

Reichenau, Switzerland,

Wettingen

Wettingen is a residential community in the district of Baden in the Swiss canton of Aargau. With a population about 20,000, Wettingen is the second-largest municipality in the canton.

Geography

Wettingen is located on the right bank of the Li ...

,

Schaffhausen

Schaffhausen (; gsw, Schafuuse; french: Schaffhouse; it, Sciaffusa; rm, Schaffusa; en, Shaffhouse) is a list of towns in Switzerland, town with historic roots, a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in northern Switzerland, and the ...

,

Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

on the way to which the bottom of Soane's trunk came loose on the coach and spilled the contents behind it, he thus lost many of his books, drawings, drawing instruments, clothes and his gold and silver medals from the Royal Academy (none of which was recovered). He continued his journey on to

Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic German, Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population o ...

,

Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

,

Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

,

Leuven

Leuven (, ) or Louvain (, , ; german: link=no, Löwen ) is the capital and largest city of the province of Flemish Brabant in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is located about east of Brussels. The municipality itself comprises the historic ...

and

Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

before embarking for England.

Struggle to establish architectural practice

He reached England in June 1780, thanks to his Grand Tour he was £120 in debt.

[Darley, 1999, p. 59] After a brief stop in London, Soane headed for Frederick Augustus Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol's estate at

Ickworth House

Ickworth House is a country house at Ickworth, near Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, England. It is a neoclassical building set in parkland. The house was the residence of the Marquess of Bristol before being sold to the National Trust in 1998.

H ...

in Suffolk, where the Earl was planning to build a new house. But immediately the Earl changed his mind and dispatched Soane to

Downhill House

Downhill House was a mansion built in the late 18th century for Frederick, 4th Earl of Bristol and Lord Bishop of Derry (popularly known as 'the Earl-Bishop'), at Downhill, County Londonderry. Much of the building was destroyed by fire in 18 ...

, in

County Londonderry

County Londonderry ( Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry ( ga, Contae Dhoire), is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty two counties of Ireland and one of the nine counties of Ulster. B ...

, Ireland, where Soane arrived on 27 July 1780. The Earl had grandiose plans to rebuild the house, but Soane and the Earl disagreed over the design and parted company, Soane receiving only £30 for his efforts. He left via

Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

sailing to

Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

.

From Glasgow he travelled to

Allanbank, Scottish Borders

Allanbank is a village near Allanton, in the Scottish Borders area of Scotland, in the historic county of Berwickshire.

Allanbank Chapel was dedicated to St. Mary and was located in a small field named Chapel Haugh.

Nearby places include Bla ...

, home of a family by the name of Stuart he had met in Rome, he prepared plans for a new mansion for the family, but again the commission came to nothing. In early December 1780 Soane took lodgings at 10 Cavendish Street, London. To pay his way his friends from the Grand Tour, Thomas Pitt and Philip Yorke, gave him commissions for repairs and minor alterations.

Anna, Lady Miller, considered building a temple in her garden at

Batheaston

Batheaston is a village and civil parish east of the English city of Bath, on the north bank of the River Avon. The parish had a population of 2,735 in 2011. The northern area of the parish, on the road to St Catherine, is an area known as No ...

to Soane's design and he hoped he might receive work from her circle of friends. But again this was not to be.

[Darley, 1999, p. 62] To help him out, George Dance gave Soane a few measuring jobs, including one in May 1781 on his repairs to

Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

of damage caused by the

Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were several days of rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. They began with a large and orderly protest against the Papists Act 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against British ...

.

To give Soane some respite, Thomas Pitt invited him to stay in 1781 at his Thamesside villa of

Petersham Lodge, which Soane was commissioned to redecorate and repair.

[Darley, 1999, p. 63] Also in 1781 Philip Yorke gave Soane commissions: at his home, Hamels Park in

Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

, he designed a new entrance gate and lodges, followed by a new dairy and alterations to the house, and in London alterations and redecoration of 63 New Cavendish Street. Increasingly desperate for work Soane entered a competition in March 1782 to design a prison, but failed to win.

Soane continued to get other minor design work in 1782.

Success at last

From the mid-1780s on Soane would receive a steady stream of commissions until his semi-retirement in 1832.

Early domestic works

It was not until 1783 that Soane received his first commission for a new country house,

Letton Hall in Norfolk. The house was a fairly modest villa but it was a sign that at last Soane's career was taking off and led to other work in

East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

:

Saxlingham Rectory in 1784, Shotesham Hall in 1785, Tendring Hall in 1784–86, and the remodelling of

Ryston

Ryston is a small village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It once had its own railway station.

The villages name means 'Brushwood farm/settlement'.

It covers an area of and had a population of 93 in 34 households at the 200 ...

Hall in 1787.

At this early stage in his career Soane was dependent on domestic work, including:

Piercefield House

Piercefield House is a largely ruined neo-classical country house near St Arvans, Monmouthshire, Wales, about north of the centre of Chepstow. The central block of the house was designed in the very late 18th century, by, or to the designs of, ...

(1784), now a ruin; the remodelling of

Chillington Hall

Chillington Hall is a Georgian country house near Brewood, Staffordshire, England, four miles northwest of Wolverhampton. It is the residence of the Giffard family. The Grade I listed house was designed by Francis Smith in 1724 and John Soan ...

(1785);

[Stroud, 1984, p. 246] The Manor,

Cricket St Thomas

Cricket St Thomas is a parish in Somerset, England, situated in a valley between Chard and Crewkerne within the South Somerset administrative district.

The A30 road passes nearby. The parish has a population of 50. It is noted for the historic ...

(1786);

Bentley Priory

Bentley Priory is an eighteenth to nineteenth century stately home and deer park in Stanmore on the northern edge of the Greater London area in the London Borough of Harrow.

It was originally a medieval priory or cell of Canons Regular, Augus ...

(1788);

the extension of the Roman Catholic Chapel at

New Wardour Castle

New Wardour Castle is a Grade I listed English country house at Wardour, near Tisbury in Wiltshire, built for the Arundell family. The house is of Palladian style, designed by the architect James Paine, with additions by Giacomo Quarenghi, wh ...

(1788). An important commission was alterations to

William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

's

Holwood House

Holwood House is a country house in Keston, near Hayes, in the London Borough of Bromley, England. The house was designed by Decimus Burton, built between 1823 and 1826 and is in the Greek Revival style. It was built for John Ward who later em ...

in 1786, Soane had befriended William Pitt's uncle Thomas on his grand tour. In 1787 Soane remodelled the interior of Fonthill Splendens (later replaced by

Fonthill Abbey

Fonthill Abbey—also known as Beckford's Folly—was a large Gothic Revival country house built between 1796 and 1813 at Fonthill Gifford in Wiltshire, England, at the direction of William Thomas Beckford and architect James Wyatt. It was b ...

) for Thomas Beckford, adding a picture gallery lit by two domes and other work.

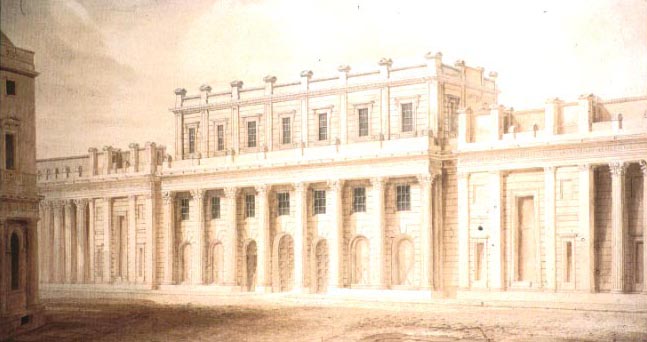

Bank of England

On 16 October 1788 he succeeded

Sir Robert Taylor

Sir Robert Taylor (1714–1788) was an English architect and sculptor who worked in London and the south of England.

Early life

Born at Woodford, Essex, Taylor followed in his father's footsteps and started working as a stonemason and sculptor ...

as architect and surveyor to the Bank of England. He would work at the bank for the next 45 years, resigning in 1833. Given Soane's youth and relative inexperience, his appointment was down to the influence of William Pitt, who was then the Prime Minister and his friend from the Grand Tour, Richard Bosanquet whose brother was

Samuel Bosanquet, Director and later Governor of the Bank of England.

[Stroud, 1984, p. 60] His salary was set at 5% of the cost of any building works at the Bank, paid every six months. Soane would virtually rebuild the entire bank, and vastly extend it. The five main banking halls were based on the same basic layout, starting with the Bank Stock Office of 1791–96, consists of a rectangular room, the centre with a large lantern light supported by piers and

pendentive

In architecture, a pendentive is a constructional device permitting the placing of a circular dome over a square room or of an elliptical dome over a rectangular room. The pendentives, which are triangular segments of a sphere, taper to points ...

s, then the four corners of the rectangle have low vaulted spaces, and in the centre of each side compartments rising to the height of the arches supporting the central lantern, the room is vaulted in brick and windows are iron framed to ensure the rooms are as fire proof as possible.

His work at the bank was:

*Erection of Barracks for the Bank Guards and rooms for the Governor, officers and servants of the Bank (1790).

[Schumann-Bacia, p. 48]

*Between 1789 and February 1791 Soane oversaw acquisition of land northwards along Princes Street.

*The erection of the outer wall along the newly acquired land (1791).

*Erection of the Bank Stock Office the first of his major interiors at the bank, with its fire proof brick vault (1791–96).

*The erection of The Four Percent Office (replacing Robert Taylor's room) (1793).

*The erection of the Rotunda (replacing Robert Taylor's rotunda) (1794).

*The erection of the Three Percent Consols Transfer Office (1797–99).

*Acquisition of more land to the north along Bartholomew Lane,

Lothbury

Lothbury is a short street in the City of London. It runs east–west with traffic flow in both directions, from Gresham Street's junction with Moorgate to the west, and Bartholomew Lane's junction with Throgmorton Street to the east.

History ...

and Prince's Street (1792).

[Schumann-Bacia, p. 77]

*Erection of outer wall along the north-east corner of the site, including an entrance arch for carriage (1794–98).

*Erection of houses for the Chief Accountant and his deputy (1797).

*The erection of the Lothbury Court within the new gate, leading to the inner courtyard used to receive

Bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes from t ...

(1797–1800).

*Extension of the Bank to the north-west, the exterior wall was extended around the junction of Lothbury and Princes Street, forming the 'Tivoli Corner' which is based on the

Temple of Vesta, Tivoli

The Temple of Vesta is a Roman temple in Tivoli, Italy, dating to the early 1st century BC. Its ruins sit on the acropolis of the city, overlooking the falls of the Aniene that are now included in the Villa Gregoriana.

History

It is not known ...

that Soane had visited and much admired, halfway down Princes street he created the

Doric Doric may refer to:

* Doric, of or relating to the Dorians of ancient Greece

** Doric Greek, the dialects of the Dorians

* Doric order, a style of ancient Greek architecture

* Doric mode, a synonym of Dorian mode

* Doric dialect (Scotland)

* Doric ...

Vestibule as a minor entrance to the building and within two new courtyards that were surrounded by the rooms he built in 1790 and new rooms including printing offices for

banknote

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable instrument, negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes w ...

s, the £5 Note Office and new offices for the Accountants, the Bullion Office off the Lothbury Court (1800–1808).

*Rebuilding of the vestibule and entrance from Bartholmew Lane (1814–1818).

*The rebuilding of Robert Taylor's 3 Percent Consols Transfer Office and 3 Percent Consols Warrant Office and completion of the exterior wall around the south-east and south-west boundaries including the main-entrance in the centre of

Threadneedle Street

Threadneedle Street is a street in the City of London, England, between Bishopsgate at its northeast end and Bank junction in the southwest. It is one of nine streets that converge at Bank. It lies in the ward of Cornhill.

History

The stree ...

(1818–1827).

In 1807 Soane designed New Bank Buildings on Princes Street for the Bank, consisting of a terrace of five mercantile residences, which were then leased to prominent city firms.

The Bank being Soane's most famous work, Sir

Herbert Baker

Sir Herbert Baker (9 June 1862 – 4 February 1946) was an English architect remembered as the dominant force in South African architecture for two decades, and a major designer of some of New Delhi's most notable government structures. He wa ...

's rebuilding of the Bank, demolishing most of Soane's earlier building was described by

Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, ''The Buildings of England'' (1 ...

as "the greatest architectural crime, in the

City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

, of the twentieth century".

Architects' Club

A growing sign of Soane's success was an invitation to become a member of the Architects' Club that was formed on 20 October 1791. Practically all the leading practitioners in London were members, and it combined a meeting to discuss professional matters, at 5:00 pm on the first Thursday of every month with a dinner. The four founders were Soane's former teachers George Dance and Henry Holland with

James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to 1806.

Early life

W ...

and

Samuel Pepys Cockerell

Samuel Pepys Cockerell (1753–1827) was an English architect.

He was a son of John Cockerell, of Bishop's Hull, Somerset, and the elder brother of Sir Charles Cockerell, 1st Baronet, for whom he designed the house he is best known for, Sezinc ...

. Other original members included: Sir William Chambers, Thomas Sandby,

Robert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and trained under him. With his o ...

,

Matthew Brettingham the Younger

Matthew Brettingham the Younger (1725 – 18 March 1803) was an architect. He was the eldest son of Matthew Brettingham the Elder and worked also in Palladian style.

He travelled to Italy in 1747, where he purchased sculptures and artwork for his ...

,

Thomas Hardwick

Thomas Hardwick (1752–1829) was an English architect and a founding member of the Architects' Club in 1791.

Early life and career

Hardwick was born in Brentford, Middlesex the son of a master mason turned architect also named Thomas Hard ...

and

Robert Mylne. Members who later joined included

Sir Robert Smirke

Sir Robert Smirke (1 October 1780 – 18 April 1867) was an English architect, one of the leaders of Greek Revival architecture, though he also used other architectural styles. As architect to the Board of Works, he designed several major ...

and

Sir Jeffrey Wyattville.

Royal Hospital Chelsea

On 20 January 1807 Soane was made clerk of works of Royal Hospital Chelsea. He held the post until his death thirty years later; it paid a salary of £200 per annum. His designs were: built 1810 a new infirmary (destroyed in 1941 during

The Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

), a new stable block and extended his own official residence in 1814; a new bakehouse in 1815; a new gardener's house 1816, a new guard-house and Secretary's Office with space for fifty staff 1818; a Smoking Room in 1829 and finally a garden shelter in 1834.

[Stroud, 1984, p. 200]

Freemasons' Hall, London

Soane, who was a

UGLE

The United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) is the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in England, Wales and the Commonwealth of Nations. Claiming descent from the Masonic grand lodge formed 24 June 1717 at the Goose & Gridiron ...

Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

, was employed to extend Freemasons' Hall, London in 1821 by building a new gallery; later in 1826 he prepared various plans for a new hall, but it was only built in 1828–31, including a council chamber, and smaller room next to it and a staircase leading to a kitchen and scullery in the basement. The building was demolished to make way for the current building.

Official appointments

In October 1791 Soane was appointed

Clerk of Works

A clerk of works or clerk of the works (CoW) is employed by an architect or a client on a construction site. The role is primarily to represent the interests of the client in regard to ensuring that the quality of both materials and workmanship are ...

with responsibility for

St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Altho ...

,

Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It is the main ...

and The

Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

. Between 1795 and 1799 Soane was Deputy Surveyor of His Majesty's Woods and Forest, on a salary of £200 per annum.

James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to 1806.

Early life

W ...

's death in 1813 led to Soane together with

John Nash and

Robert Smirke, being appointed official architect to the

Office of Works

The Office of Works was established in the England, English Royal Household, royal household in 1378 to oversee the building and maintenance of the royal castles and residences. In 1832 it became the Works Department forces within the Office of W ...

in 1813, the appointment ended in 1832, at a salary of £500 per annum. As part of this position he was invited to advise the Parliamentary

Commissioners on the building of new churches from 1818 onward. He was required to produce designs for churches to seat 2000 people for £12,000 or less though Soane thought the cost too low, of the three churches he designed for the Commission all were classical in style. The three churches were:

St Peter's Church, Walworth

St Peter's Church is an Anglican parish church in Walworth, London, in the Woolwich Episcopal Area of the Anglican Diocese of Southwark. It was built between 1823–25 and was the first church designed by Sir John Soane, in the wave of the churc ...

(1823–24), for £18,348;

Holy Trinity Church, Marylebone

Holy Trinity Church, in Marylebone, Westminster, London, is a Grade I listed former Anglican church, built in 1828 and designed by John Soane. In 1818 Parliament passed an act setting aside one million pounds to celebrate the defeat of Napoleo ...

(1826–27), for £24,708;

St John on Bethnal Green

St John on Bethnal Green is an early 19th-century church near Bethnal Green, London, England, and is located on the Green itself. It was constructed 1826–28 to the design of the architect Sir John Soane (1753–1837). It is an Anglican church ...

(1826–28), for £15,999.

Public buildings

Soane designed several public buildings in London, including: National Debt Redemption Office (1817) demolished 1900; Insolvent Debtors Court

[Stroud, 1984, p. 219] (1823) demolished 1861; Privy Council and Board of Trade Offices,

Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It is the main ...

(1823–24), remodelled by Sir

Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also respons ...

, the building now houses the

Cabinet Office

The Cabinet Office is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for supporting the prime minister and Cabinet. It is composed of various units that support Cabinet committees and which co-ordinate the delivery of government objecti ...

; in a new departure for Soane he used the

Italianate

The Italianate style was a distinct 19th-century phase in the history of Classical architecture. Like Palladianism and Neoclassicism, the Italianate style drew its inspiration from the models and architectural vocabulary of 16th-century Italian R ...

style for The New State Paper Office, (1829–30) demolished 1868 to make way for the

Foreign and Commonwealth Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, department of the Government of the United Kingdom. Equivalent to other countries' Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ministries of fore ...

building.

His commissions in Ireland included:

Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, Soane was commissioned by the

Bank of Ireland

Bank of Ireland Group plc ( ga, Banc na hÉireann) is a commercial bank operation in Ireland and one of the traditional Big Four Irish banks. Historically the premier banking organisation in Ireland, the Bank occupies a unique position in Iris ...

to design a new headquarters for the triangular site on Westmoreland Street now occupied by the Westin Hotel. However, when the Irish Parliament was abolished in 1800, the Bank abandoned the project and instead bought the former Parliament Buildings. In 1808 he started work on the design of the

Royal Belfast Academical Institution

The Royal Belfast Academical Institution is an independent grammar school in Belfast, Northern Ireland. With the support of Belfast's leading reformers and democrats, it opened its doors in 1814. Until 1849, when it was superseded by what today is ...

, for which he refused to charge. Building work began on 3 July 1810 and was completed in 1814. The remodelling of the interior has left little of Soane's work.

Later domestic work

Country homes for the

landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the ''gentry'', is a largely historical British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. While distinct from, and socially below, the British peerage, th ...

included: new rooms and remodelling of

Wimpole Hall

Wimpole Estate is a large estate containing Wimpole Hall, a country house located within the civil parish of Wimpole, Cambridgeshire, England, about southwest of Cambridge. The house, begun in 1640, and its of parkland and farmland are owned ...

and garden buildings, (1790–94) for his friend Philip Yorke whom he met on his Grand Tour; remodelling of

Baronscourt

Baronscourt, Barons-Court or Baronscourt Castle is a Georgian country house and estate 4.5 km southwest of Newtownstewart in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, and is the seat of the Duke of Abercorn. It is a Grade A-listed building.

The Ba ...

, County Tyrone, Ireland (1791);

Tyringham

Tyringham (/ˈtiːrɪŋəm/) is a village in the unitary authority area of the City of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. It is located about a mile and a half north of Newport Pagnell.

The village name is an Old English language word, an ...

Hall (1792–1820); and the remodelling of

Aynhoe Park

Aynhoe Park, is a 17th-century country estate consisting of land and buildings that were rebuilt after the English Civil War on the southern edge of the stone-built village of Aynho, Northamptonshire, England. It overlooks the Cherwell valley tha ...

(1798).

In 1804, he remodelled

Ramsey Abbey

Ramsey Abbey was a Benedictine abbey in Ramsey, Huntingdonshire (now part of Cambridgeshire), England. It was founded about AD 969 and dissolved in 1539.

The site of the abbey in Ramsey is now a Scheduled Ancient Monument. Most of the abbey's ...

(none of his work there now survives); the remodelling of the south front of

Port Eliot

Port Eliot in the parish of St Germans, Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, is the ancestral seat of the Eliot family, whose present head is Albert Eliot, 11th Earl of St Germans.

Port Eliot comprises a stately home with its own church, which ...

and new interiors (1804–06); the Gothic Library at

Stowe House (1805–06);

Moggerhanger House

Moggerhanger House is a Listed building, Grade I-listed country house in Moggerhanger, Bedfordshire, England, designed by the eminent architect John Soane. The house is owned by a Christian charity, Harvest Vision, and the Moggerhanger House Pres ...

(1791–1809); for

Marden Hill, Hertfordshire, Soane designed a new porch and entrance hall (1818); the remodelling of

Wotton House

Wotton House, Wotton Underwood, Buckinghamshire, England, is a stately home built between 1704 and 1714, to a design very similar to that of the contemporary version of Buckingham House. The house is an example of English Baroque and a Grade I ...

after damage by fire (1820); a terrace of six houses above shops in

Regent Street

Regent Street is a major shopping street in the West End of London. It is named after George, the Prince Regent (later George IV) and was laid out under the direction of the architect John Nash and James Burton. It runs from Waterloo Place ...

London (1820–21), demolished; and

Pell Wall Hall

Pell Wall Hall is a neo-classical country house on the outskirts of Market Drayton in Shropshire. Faced in Grinshill sandstone, Pell Wall is the last completed domestic house designed by Sir John Soane and was constructed 1822–1828 for local ...

(1822). Among Soane's most notable works are the dining rooms of both Numbers

10 and

11 Downing Street (1824–26) for the Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer respectively of Great Britain.

Dulwich Picture Gallery

In 1811, Soane was appointed as architect for Dulwich Picture Gallery, the first purpose-built public

art gallery

An art gallery is a room or a building in which visual art is displayed. In Western cultures from the mid-15th century, a gallery was any long, narrow covered passage along a wall, first used in the sense of a place for art in the 1590s. The lon ...

in Britain, to house the Dulwich collection, which had been held by art dealers Sir

Francis Bourgeois

Sir Peter Francis Lewis Bourgeois RA (November 1753 – 8 January 1811) was a landscape painter and history painter, and court painter to king George III of the United Kingdom.

In the late 18th century he became an art dealer and collector in ...

and his partner Noel Desenfans. Bourgeois's will stipulated that the Gallery should be designed by his friend John Soane to house the collection. Uniquely the building also incorporates a

mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be consid ...

containing the bodies of Francis Bourgeois, and Mr and Mrs Desenfans.

The Dulwich Picture Gallery was completed in 1817. The five main galleries are lit by elongated

roof lanterns.

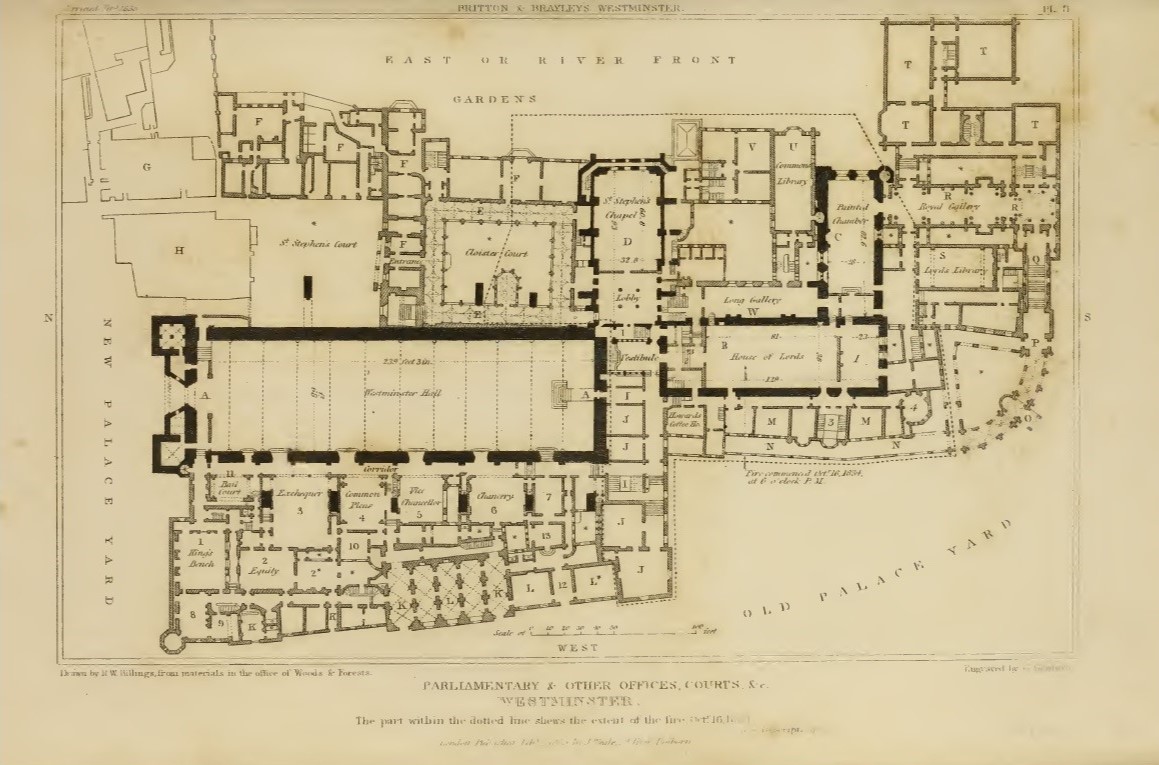

New Law Courts

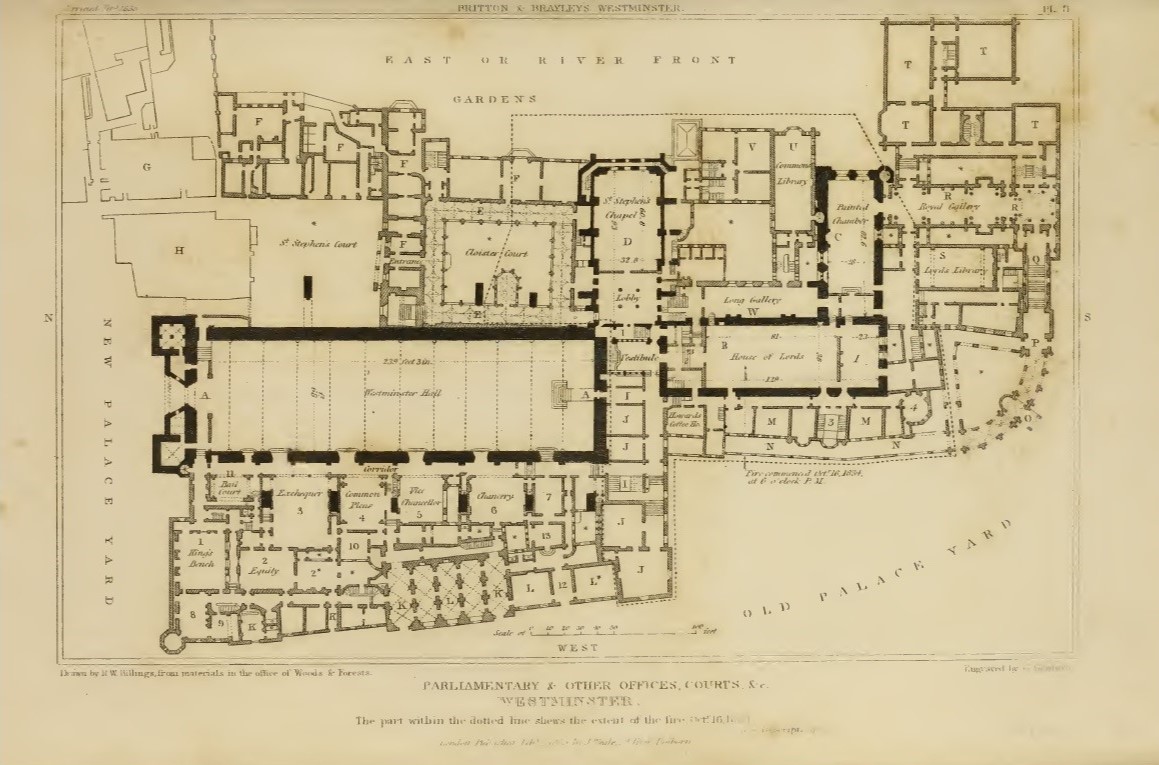

As an official architect of the Office of Works Soane was asked to design the New Law Courts at

Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

, he began surveying the building on 12 July 1820. Soane was to extend the law courts along the west front of Westminster Hall providing accommodation for five courts: The Court of Exchequer, Chancery, Equity, King's Bench and Common Pleas. The foundations were laid in October 1822 and the shell of the building completed by February 1824. Then

Henry Bankes

Henry Bankes (1757–1834) was an English politician and author.

Life

Bankes was the only surviving son of Henry Bankes and the great-grandson of Sir John Bankes, chief justice of the common pleas in the time of Charles I.

Bankes was educated ...

launched an attack on the design of the building, as a consequence Soane had to demolish the facade and set the building lines back several feet and redesign the building in a

gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

style instead of the original classical design, Soane rarely designed gothic buildings. The building opened on 21 January 1825, and remained in use until the

Royal Courts of Justice

The Royal Courts of Justice, commonly called the Law Courts, is a court building in Westminster which houses the High Court and Court of Appeal of England and Wales. The High Court also sits on circuit and in other major cities. Designed by Ge ...

opened in 1882, after this the building was demolished in 1883 and the site left as lawn. All the court rooms displayed Soane's typically complex lighting arrangements, being top lit by

roof lanterns often concealed from direct view.

Palace of Westminster

In 1822 as an official architect of the Office of Works, Soane was asked to make alteration to the House of Lords at the Palace of Westminster. He added a curving gothic arcade with an entrance leading to a courtyard, a new Royal Gallery, main staircase and Ante-Room, all the interiors were in a grand neo-classical style, completed by January 1824. Later four new committee rooms, a new library for the House of Lords and for the House of Commons alterations to the

Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

house, and new library, committee rooms, clerks' rooms and stores, all would be destroyed in the fire of 1834.

Design for a Royal Palace

One of Soane's largest designs was for a new Royal Palace in London, a series of designs were produced c. 1820–30. The design was unusual in that the building was triangular, there were grand porticoes at each corner and in the middle of each side of the building, the centre of the building consisted of a low dome, with ranges of rooms leading to the entrances in each side of the building, creating three internal courtyards. As far as is known it is not related to an official commission and was merely a design exercise by Soane, indeed the various drawings he produced date over several years, he first produced a design for a Royal Palace while in Rome in 1779.

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy was at the very centre of Soane's architectural career, in the sixty four years from 1772 to 1836 there were only five years, 1778 and 1788–91, in which he did not exhibit any designs there. Soane had received part of his architectural education at the Academy and it had paid for his Grand Tour. On 2 November 1795 Soane was elected an Associate Royal Academician and on 10 February 1802 Soane was elected a full

Royal Academician

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

,

[Bingham, 2011, p. 66] his diploma work being a drawing of his design for a new House of Lords. There were only ever a maximum of forty Royal Academicians at any one time. Under the rules of the Academy Soane automatically became for one year a member of the Council of the Academy, this consisted of the President and eight other Academicians.