John André on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John André (2 May 1750/1751''Gravesite–Memorial''

Westminster Abbey webpage; accessed September 2020 – 2 October 1780) was a major in the

André went up the

André went up the

André rode on in safety until 9 a.m. on 23 September, when he came near

André rode on in safety until 9 a.m. on 23 September, when he came near  At first, all went well for André since post commandant Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson decided to send him to Arnold, never suspecting that a high-ranking hero of the Revolution could be a turncoat. But Major

At first, all went well for André since post commandant Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson decided to send him to Arnold, never suspecting that a high-ranking hero of the Revolution could be a turncoat. But Major

Washington convened a board of senior officers to investigate the matter. The trial contrasted with

Washington convened a board of senior officers to investigate the matter. The trial contrasted with

On the day of his capture,

On the day of his capture,  A pension was awarded by the British to his mother and three sisters not long after his death, and his brother William André was made a

A pension was awarded by the British to his mother and three sisters not long after his death, and his brother William André was made a

Local History: British Agent Detained in Tarrytown, Executed in Rockland

* * * *

* ttp://www.ushistory.org/march/bio/andre.htm More on his early life {{DEFAULTSORT:Andre, John 1780 deaths 18th-century executions by the United States 18th-century executions by New York (state) American Revolutionary War executions British Army personnel of the American Revolutionary War English people of French descent Executed people from London Burials at Westminster Abbey British people executed abroad British military personnel killed in the American Revolutionary War Cameronians officers Executed spies Benedict Arnold British spies during the American Revolution Huguenot participants in the American Revolution People executed by the United States military by hanging Royal Welch Fusiliers officers 1750s births

Westminster Abbey webpage; accessed September 2020 – 2 October 1780) was a major in the

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

and head of its Secret Service in America during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. He was hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

as a spy

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

by the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

for assisting Benedict Arnold's attempted surrender of the fort at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York, West Point was identified by General George Washington as the most important strategic position in America during the Ame ...

, to the British. André is typically remembered favorably by historians as a man of honor, and several prominent U.S. leaders of the time, including Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

and the Marquis de Lafayette, did not agree with his fate.

Early life and education

André was born on 2 May in 1750 or 1751 in London to wealthyHuguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

parents Antoine André, a merchant from Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, and Marie Louise Girardot from Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

. He was educated at St Paul's School, Westminster School

(God Gives the Increase)

, established = Earliest records date from the 14th century, refounded in 1560

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, head_label = Hea ...

, and in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

. He was briefly engaged to Honora Sneyd

Honora Edgeworth (''née'' Sneyd; 1751 – 1 May 1780) was an eighteenth-century English writer, mainly known for her associations with literary figures of the day particularly Anna Seward and the Lunar Society, and for her work on children's e ...

. In 1771, at age 20 he joined the army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, first being commissioned second lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

in the 23rd Regiment (Royal Welch Fuziliers) but soon exchanging as lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

in the 7th Regiment of Foot (Royal Fuzileers). He was on leave of absence in Germany for nearly two years, and in 1774 joined his regiment in British Canada

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

.

Career

During the early days of theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, before independence was declared by the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

, André was captured at Fort Saint-Jean by Continental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continent, the major landmasses of Earth

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' ( ...

General Richard Montgomery in November 1775, and held prisoner at Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Lancaster, ( ; pdc, Lengeschder) is a city in and the county seat of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It is one of the oldest inland cities in the United States. With a population at the 2020 census of 58,039, it ranks 11th in population amon ...

. He lived in the home of Caleb Cope, enjoying the freedom of the town, as he had given his word not to escape. In December 1776, he was freed in a prisoner exchange

A prisoner exchange or prisoner swap is a deal between opposing sides in a conflict to release prisoners: prisoners of war, spies, hostages, etc. Sometimes, dead bodies are involved in an exchange.

Geneva Conventions

Under the Geneva Convent ...

. He was promoted to captain in the 26th Foot on 18 January 1777. In 1777 he was aide-de-camp to Major-General Grey, serving thus on the expedition to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, and Brandywine Brandywine may refer to:

Food and drink

*Brandy, a spirit produced by distilling wine

*Brandywine tomato, a variety of heirloom tomato

Geographic locations Canada

* Brandywine Falls Provincial Park, British Columbia

* Brandywine Mountain, British ...

and Germantown Germantown or German Town may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Germantown, Queensland, a locality in the Cassowary Coast Region

United States

* Germantown, California, the former name of Artois, a census-designated place in Glenn County

* Ge ...

. In September, 1778, he accompanied Gen. Grey in the New Bedford expedition, and was sent back to Sir Henry Clinton as despatch bearer. On Gen. Grey's return to England, André was appointed aide-de-camp to Clinton with the rank of major.

He was a great favorite in colonial society, both in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and New York, during those cities' occupation by the British Army. He had a lively and pleasant manner and could draw, paint, and create silhouette

A silhouette ( , ) is the image of a person, animal, object or scene represented as a solid shape of a single colour, usually black, with its edges matching the outline of the subject. The interior of a silhouette is featureless, and the silhou ...

s, as well as sing and write verse. He was a prolific writer who carried on much of General Henry Clinton's correspondence, the British Commander-in-Chief of British armies in America. He was fluent in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, French, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, and Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

. He also wrote many comic verses. He planned the Mischianza when General Howe, Clinton's precursor, resigned and was about to return to England.

During his nearly nine months in Philadelphia, André occupied Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

's house, from which it has been claimed that he removed several valuable items on the orders of Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Charles Grey when the British left Philadelphia, including an oil portrait of Franklin by Benjamin Wilson. Grey's descendants returned Franklin's portrait to the United States in 1906, the bicentennial of Franklin's birth. The painting now hangs in the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

.

Intelligence work

Head of British Secret Service in America

In 1779, André becameAdjutant General

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

of the British Army in North America with the rank of Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

. In April of that year, he took charge of British Secret Service in America. By the next year (1780), he had briefly taken part in Clinton's invasion of the South, starting with the siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

of Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

.

Around this time, André had been negotiating with disillusioned U.S. general Benedict Arnold. Arnold's Loyalist wife Peggy Shippen

Margaret "Peggy" Shippen (July 11, 1760 – August 24, 1804) was the highest-paid spy in the American Revolution, and was the second wife of General Benedict Arnold.

Shippen was born into a prominent Philadelphia family with Loyalist tendencies. ...

was one of the go-betweens in the correspondence. Arnold commanded West Point and had agreed to surrender it to the British for £20,000 (approximately £3.62 million in 2021).

André went up the

André went up the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

on the British sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

''Vulture

A vulture is a bird of prey that scavenges on carrion. There are 23 extant species of vulture (including Condors). Old World vultures include 16 living species native to Europe, Africa, and Asia; New World vultures are restricted to North and ...

'' on Wednesday, 20 September 1780 to visit Arnold. The presence of the warship was discovered by two American privates, John Peterson and Moses Sherwood, the following morning on 21 September. From their position at Teller's Point, they began to assail the ''Vulture'' and a longboat associated with it with rifle and musket fire. Pausing to secure more aid, Peterson and Sherwood headed to Fort Lafayette at Verplanck's Point to request cannons and ammunition from their commander, Colonel James Livingston. While they were gone, a small boat furnished by Arnold was steered to the ''Vulture'' by Joshua Hett Smith. At the oars were two brothers, tenants of Smith's who reluctantly rowed the boat on the river to the sloop. Despite Arnold's assurances, the two oarsmen sensed that something was wrong. None of these men knew Arnold's purpose or suspected his treason; all were told that the purpose was to do good for the American cause. Only Smith was told anything specific, and that was the lie that it was to secure vital intelligence for the American cause. The brothers finally agreed to row after threats by Arnold to arrest them. They picked up André and placed him on shore. The others left and Arnold came to André on horseback, leading an extra horse for André's use.

The two men conferred in the woods below Stony Point on the river's west bank until nearly dawn, after which André accompanied Arnold several miles to the Joshua Hett Smith House

Joshua Hett Smith House (demolished), also known as Treason House, was a historic house in West Haverstraw, New York. It stood on a hill overlooking the King's Ferry at Stony Point, an important crossing of the Hudson River. During the American ...

(Treason House) in West Haverstraw, New York

West Haverstraw is a village incorporated in 1883 in the town of Haverstraw, Rockland County, New York, United States. It is located northwest of Haverstraw village, east of Thiells, south of the hamlet of Stony Point, and west of the Hudson Ri ...

, owned by Thomas Smith and occupied by his brother Joshua. On the morning of 22 September, the two Americans, Peterson and Sherwood, launched a two-hour cannonade on the ''Vulture'', which sustained many hits and was forced to retire downriver. Their repulsion of the British sloop effectively stranded André on shore.

Taken into custody

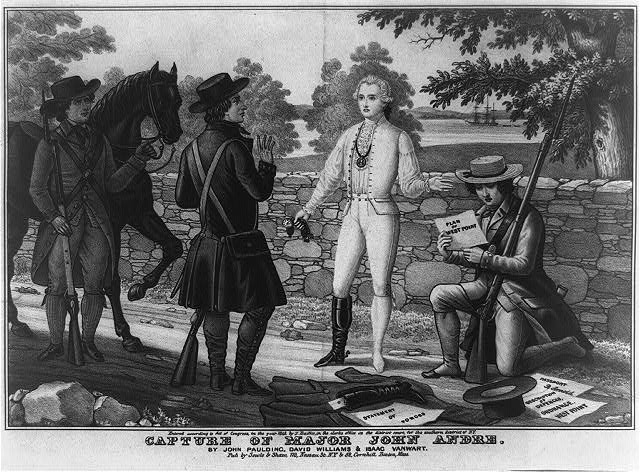

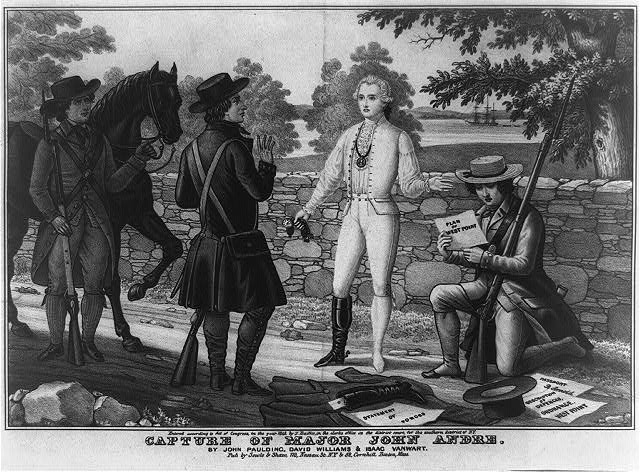

To aid André's escape through U.S. lines, Arnold provided him with civilian clothes and a passport which allowed him to travel under the name John Anderson. He bore six papers hidden in his stocking, written in Arnold's hand, that showed the British how to take the fort. Joshua Hett Smith, who was accompanying him, left him just before he was captured. André rode on in safety until 9 a.m. on 23 September, when he came near

André rode on in safety until 9 a.m. on 23 September, when he came near Tarrytown, New York

Tarrytown is a village in the town of Greenburgh in Westchester County, New York. It is located on the eastern bank of the Hudson River, approximately north of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, and is served by a stop on the Metro-North ...

, where armed militiamen John Paulding

John Paulding (October 16, 1758 – February 18, 1818) was an American militiaman from the state of New York during the American Revolution. In 1780, he was one of three men who captured Major John André, a British spy associated with the treas ...

, Isaac Van Wart

Isaac Van Wart (October 25, 1762May 23, 1828) was a militiaman from the state of New York during the American Revolution. In 1780, he was one of three men who captured British Major John André, who was convicted and executed as a spy for conspir ...

and David Williams stopped him.Raymond, pp. 11–17Cray, pp. 371–397

André thought that they were Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

because one was wearing a Hessian soldier's overcoat. "Gentlemen," he said, "I hope you belong to our party." "What party?" asked one of the men. "The lower party", replied André, meaning the British. "We do" was the answer. André then told them that he was a British officer who must not be detained, when, to his surprise, they said that they were Continentals and that he was their prisoner. He then told them that he was a US officer and showed them his passport, but the suspicions of his captors were now aroused. They searched him and found Arnold's papers in his stocking. Only Paulding could read and Arnold was not initially suspected. André offered them his horse and watch to let him go, but they declined. André testified at his trial that the men searched his boots for the purpose of robbing him. Paulding realized that he was a spy and took him to Continental Army headquarters in Sand's mill (in today's Armonk, New York

Armonk is a hamlet and census-designated place (CDP) in the town of North Castle, located in Westchester County, New York, United States.

The corporate headquarters of IBM are located in Armonk.

Geography and climate

As of the 2010 census, A ...

, a hamlet within North Castle

North Castle is a town in Westchester County, New York, United States. The population was 11,841 at the 2010 census. It has three hamlets: Armonk, Banksville, and North White Plains.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the t ...

situated on the Connecticut border of Westchester County

Westchester County is located in the U.S. state of New York. It is the seventh most populous county in the State of New York and the most populous north of New York City. According to the 2020 United States Census, the county had a population o ...

).

The prisoner was at first detained at Wright's Mill in North Castle, before being taken back across the Hudson to the headquarters of the American army at Tappan, where he was held at a tavern today known as the '76 House. There he admitted his true identity.

At first, all went well for André since post commandant Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson decided to send him to Arnold, never suspecting that a high-ranking hero of the Revolution could be a turncoat. But Major

At first, all went well for André since post commandant Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson decided to send him to Arnold, never suspecting that a high-ranking hero of the Revolution could be a turncoat. But Major Benjamin Tallmadge

Benjamin Tallmadge (February 25, 1754 – March 7, 1835) was an American military officer, spymaster, and politician. He is best known for his service as an officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He acted as leade ...

, head of Continental Army Intelligence, arrived and persuaded Jameson to bring the prisoner back. He offered intelligence showing that a high-ranking officer was planning to defect to the British but was unaware of who it was.

Jameson sent General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

the six sheets of paper carried by André, but he was unwilling to believe that Arnold could be guilty of treason. He therefore insisted on sending a note to Arnold informing him of the entire situation. Jameson did not want his army career to be ruined later for having wrongly believed that his general was a traitor. Arnold received Jameson's note while at breakfast with his officers, made an excuse to leave the room, and was not seen again. The note gave Arnold time to escape to the British. An hour or so later, Washington arrived at West Point with his party and was disturbed to see the stronghold's fortifications in such neglect, part of the plan to weaken West Point's defenses. Washington was further irritated to find that Arnold had breached protocol by not being about to greet him. Some hours later, Washington received the explanatory information from Tallmadge and immediately sent men to arrest Arnold, but it was too late.

According to Tallmadge's account of the events, he and André conversed during the latter's captivity and transport. André wanted to know how he would be treated by Washington. Tallmadge had been a classmate of Nathan Hale

Nathan Hale (June 6, 1755 – September 22, 1776) was an American Patriot, soldier and spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission in New York City but was captured b ...

while both were at Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

, and he described the capture of Hale. André asked whether Tallmadge thought the situations similar; he replied, "Yes, precisely similar, and similar shall be your fate", referring to Hale having been hanged by the British as a spy.

Trial and execution

Washington convened a board of senior officers to investigate the matter. The trial contrasted with

Washington convened a board of senior officers to investigate the matter. The trial contrasted with Sir William Howe

William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, KB PC (10 August 172912 July 1814) was a British Army officer who rose to become Commander-in-Chief of British land forces in the Colonies during the American War of Independence. Howe was one of three bro ...

's treatment of Hale some four years earlier. The board consisted of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

s Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependab ...

(presiding officer), Lord Stirling

William Alexander, also known as Lord Stirling (1726 – 15 January 1783), was a Scottish-American major general during the American Revolutionary War. He was considered male heir to the Scottish title of Earl of Stirling through Scottish line ...

, Arthur St. Clair, Lafayette

Lafayette or La Fayette may refer to:

People

* Lafayette (name), a list of people with the surname Lafayette or La Fayette or the given name Lafayette

* House of La Fayette, a French noble family

** Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757� ...

(who cried at André's execution), Robert Howe, Steuben, brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

s Samuel H. Parsons, James Clinton

Major General James Clinton (August 9, 1736 – September 22, 1812) was an American Revolutionary War officer who, with John Sullivan, led in 1779 the Sullivan Expedition in what is now western New York to attack British-allied Seneca and ...

, Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following the ...

, John Glover, John Paterson, Edward Hand

Edward Hand (31 December 1744 – 3 September 1802) was an Irish soldier, physician, and politician who served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, rising to the rank of general, and later was a member of several Pennsyl ...

, Jedediah Huntington

Jedediah (or Jedidiah) Huntington (4 August 1743 – 25 September 1818), was an American general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. After the war, he served in numerous civilian posts.

Early life

Huntington was born ...

, John Stark

Major-General John Stark (August 28, 1728 – May 8, 1822) was an American military officer who served during the French and Indian War and the Revolutionary War. He became known as the "Hero of Bennington" for his exemplary service at the Batt ...

, and Judge Advocate General John Laurance

John Laurance (sometimes spelled "Lawrence" or "Laurence") (1750 – November 11, 1810) was a delegate to the 6th, 7th, and 8th Congresses of the Confederation, a United States representative and United States Senator from New York and a United ...

.

André's defence was that he was suborning an enemy officer, "an advantage taken in war" (his words). However, he did not attempt to pass the blame onto Arnold. André told the court that he had neither desired nor planned to be behind American lines. He also asserted that, as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

, he had the right to escape in civilian clothes. On 29 September 1780, the board found André guilty of being behind American lines "under a feigned name and in a disguised habit" and ordered that "Major André, Adjutant-General to the British Army, ought to be considered as a Spy from the enemy, and that agreeable to the law and usage of nations, it is their opinion, he ought to suffer death."

Glover was officer of the day at André's execution. Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander in New York, did all that he could to save André, his favorite aide, but refused to surrender Arnold in exchange for him, even though he personally despised Arnold. André appealed to George Washington to be executed as a gentleman by being shot rather than hanged as a "common criminal", but he was hanged as a spy at Tappan, New York

Tappan ( ) is a hamlet and census-designated place in the town of Orangetown, Rockland County, New York. It is located northwest of Alpine, New Jersey, north of Northvale, New Jersey and Rockleigh, New Jersey, northeast of Old Tappan, Ne ...

on 2 October 1780.

A religious poem was found in his pocket after his execution, written two days beforehand.

While a prisoner, he endeared himself to American officers who lamented his death as much as the British. Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

wrote of him: "Never perhaps did any man suffer death with more justice, or deserve it less." The day before his hanging, André drew a likeness of himself with pen and ink, which is now owned by Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

. André, according to witnesses, placed the noose around his own neck.

= Eyewitness account

= An eyewitness account of André's last day can be found in the book ''The American Revolution: From the Commencement to the Disbanding of the American Army Given in the Form of a Daily Journal, with the Exact Dates of all the Important Events; Also, a Biographical Sketch of the Most Prominent Generals'' byJames Thacher

James Thacher (February 14, 1754 – May 26, 1844) was an American physician and writer, born in Barnstable, Massachusetts.

Biography

When Thacher was 16 he became an apprentice for Abner Hersey, a doctor from Barnstable, Massachusetts. From ...

, a surgeon in the American Revolutionary Army:

October 2d.-- Major André is no more among the living. I have just witnessed his exit. It was a tragical scene of the deepest interest. During his confinement and trial, he exhibited those proud and elevated sensibilities which designate greatness and dignity of mind. Not a murmur or a sigh ever escaped him, and the civilities and attentions bestowed on him were politely acknowledged. Having left a mother and two sisters in England, he was heard to mention them in terms of the tenderest affection, and in his letter to Sir Henry Clinton, he recommended them to his particular attention. The principal guard officer, who was constantly in the room with the prisoner, relates that when the hour of execution was announced to him in the morning, he received it without emotion, and while all present were affected with silent gloom, he retained a firm countenance, with calmness and composure of mind. Observing his servant enter the room in tears, he exclaimed, "Leave me till you can show yourself more manly!" His breakfast being sent to him from the table of General Washington, which had been done every day of his confinement, he partook of it as usual, and having shaved and dressed himself, he placed his hat upon the table, and cheerfully said to the guard officers, "I am ready at any moment, gentlemen, to wait on you." The fatal hour having arrived, a large detachment of troops was paraded, and an immense concourse of people assembled; almost all our general and field officers, excepting his excellency and staff, were present on horseback; melancholy and gloom pervaded all ranks, and the scene was affectingly awful. I was so near during the solemn march to the fatal spot, as to observe every movement, and participate in every emotion which the melancholy scene was calculated to produce. Major André walked from the stone house, in which he had been confined, between two of our subaltern officers, arm in arm; the eyes of the immense multitude were fixed on him, who, rising superior to the fears of death, appeared as if conscious of the dignified deportment which he displayed. He betrayed no want of fortitude, but retained a complacent smile on his countenance, and politely bowed to several gentlemen whom he knew, which was respectfully returned. It was his earnest desire to be shot, as being the mode of death most conformable to the feelings of a military man, and he had indulged the hope that his request would be granted. At the moment, therefore, when suddenly he came in view of the gallows, he involuntarily started backward, and made a pause. "Why this emotion, sir?" said an officer by his side. Instantly recovering his composure, he said, "I am reconciled to my death, but I detest the mode." While waiting and standing near the gallows, I observed some degree of trepidation; placing his foot on a stone, and rolling it over and choking in his throat, as if attempting to swallow. So soon, however, as he perceived that things were in readiness, he stepped quickly into the wagon, and at this moment he appeared to shrink, but instantly elevating his head with firmness he said, "It will be but a momentary pang," and taking from his pocket two white handkerchiefs, the provost-marshal, with one, loosely pinioned his arms, and with the other, the victim, after taking off his hat and stock, bandaged his own eyes with perfect firmness, which melted the hearts and moistened the cheeks, not only of his servant, but of the throng of spectators. The rope being appended to the gallows, he slipped the noose over his head and adjusted it to his neck, without the assistance of the awkward executioner. Colonel Scammel now informed him that he had an opportunity to speak, if he desired it; he raised the handkerchief from his eyes, and said, "I pray you to bear me witness that I meet my fate like a brave man." The wagon being now removed from under him, he was suspended, and instantly expired; it proved indeed "but a momentary pang." He was dressed in his royal regimentals and boots, and his remains, in the same dress, were placed in an ordinary coffin, and interred at the foot of the gallows; and the spot was consecrated by the tears of thousands...

Aftermath

On the day of his capture,

On the day of his capture, James Rivington

James Rivington (1724 – July 4, 1802) was an English-born American journalist who published a Loyalist newspaper in the American colonies called ''Rivington's Gazette''. He was driven out of New York by the Sons of Liberty, but was very like ...

published André's poem "The Cow Chase" in his gazette in New York. In the poem, André muses on his foiling of a foraging expedition in Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula of ...

across the Hudson from the city. Nathan Strickland, André's executioner, who was confined at the camp in Tappan as a dangerous Tory during André's trial, was granted liberty for accepting the duty of hangman and returned to his home in the Ramapo Valley

The Ramapo Mountains are a forested chain of the Appalachian Mountains in northeastern New Jersey and southeastern New York, in the United States. They range in height from in New Jersey, and in New York.

Several parks and forest preserves en ...

or Smith's Cove, and nothing further of him is known. Joshua Hett Smith, who was connected with André with the attempted treason, was also brought to trial at the Reformed Church of Tappan

The Reformed Church of Tappan in Tappan, Rockland County, New York (formed, 1694) is a historic church. It is a contributing property to the Tappan Historic District.

History

Its first structure built 1716 (worshipers met in homes before thi ...

. The trial lasted four weeks and ended in acquittal for lack of evidence. The Colquhon brothers who were commanded by Benedict Arnold to bring André from the sloop-of-war ''Vulture'' to shore, as well as Major Keirs, under whose supervision the boat was obtained, were exonerated from all suspicion.

A pension was awarded by the British to his mother and three sisters not long after his death, and his brother William André was made a

A pension was awarded by the British to his mother and three sisters not long after his death, and his brother William André was made a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

in his honour in 1781 (see André baronets

The André Baronetcy, of Southampton in the County of Southampton, was a title in the Baronetage of Great Britain. It was created on 4 March 1781 for William André, in recognition of the services rendered to the country by his brother John Andr� ...

). In 1804 a memorial plaque by Charles Regnart was erected in the Grosvenor Chapel

Grosvenor Chapel is an Anglican church in what is now the City of Westminster, in England, built in the 1730s. It inspired many churches in New England. It is situated on South Audley Street in Mayfair.

History

The foundation stone of the Gro ...

in London, to John's memory. In 1821, at the behest of the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was D ...

, his remains, which had been buried under the gallows, were removed to England and placed among kings and poets at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, in the nave, under a marble monument depicting Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Great ...

mourning alongside a British lion over André's death. In 1879 a monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, his ...

was unveiled on the place of his execution at Tappan.

The names of André's captors were John Paulding

John Paulding (October 16, 1758 – February 18, 1818) was an American militiaman from the state of New York during the American Revolution. In 1780, he was one of three men who captured Major John André, a British spy associated with the treas ...

, David Williams, and Isaac Van Wert

Isaac Van Wart (October 25, 1762May 23, 1828) was a militiaman from the state of New York during the American Revolution. In 1780, he was one of three men who captured British Major John André, who was convicted and executed as a spy for consp ...

. The United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

gave each of them a silver medal, known as the Fidelity Medallion

The Fidelity Medallion is the oldest decoration of the United States military and was created by act of the Continental Congress in 1780.

Also known as the "André Capture Medal", the Fidelity Medallion was awarded to those soldiers who parti ...

, and a pension of $200 a year. That came close to the annual pay of a Continental Army's infantry ensign in 1778. All were honoured in the names of counties in Ohio, and in 1853 a monument was erected to their memory on the place where they captured André. It was re-dedicated in 1880 and today is located in Patriot's Park

Patriot's Park (originally referred to as Brookside Park) is located on U.S. Route 9 along the boundary between Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow in Westchester County, New York, United States. It is a four-acre (1.6-ha) parcel with a walkway and se ...

on U.S. Route 9

U.S. Route 9 (US 9) is a north–south United States highway in the states of Delaware, New Jersey, and New York in the Northeastern United States. It is one of only two U.S. Highways with a ferry connection (the Cape May–Lewes Ferry, between ...

along the boundary between Tarrytown

Tarrytown is a village in the town of Greenburgh in Westchester County, New York. It is located on the eastern bank of the Hudson River, approximately north of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, and is served by a stop on the Metro-North Hu ...

and Sleepy Hollow in Westchester County

Westchester County is located in the U.S. state of New York. It is the seventh most populous county in the State of New York and the most populous north of New York City. According to the 2020 United States Census, the county had a population o ...

. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

in 1982.

* "He was more unfortunate than criminal." – from a letter of George Washington to Comte de Rochambeau

Marshal Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, 1 July 1725 – 10 May 1807, was a French nobleman and general whose army played the decisive role in helping the United States defeat the British army at Yorktown in 1781 during the ...

, 10 October 1780

* "An accomplished man and gallant officer." – from a letter written by Washington to Colonel John Laurens

John Laurens (October 28, 1754 – August 27, 1782) was an American soldier and statesman from South Carolina during the American Revolutionary War, best known for his criticism of slavery and his efforts to help recruit slaves to fight for thei ...

on 13 October 1780

In popular culture

The 1798 play ''André

André — sometimes transliterated as Andre — is the French and Portuguese form of the name Andrew, and is now also used in the English-speaking world. It used in France, Quebec, Canada and other French-speaking countries. It is a variation ...

,'' based on Major André's execution, is one of the earliest examples of American tragedy. Clyde Fitch

Clyde Fitch (May 2, 1865 – September 4, 1909) was an American dramatist, the most popular writer for the Broadway stage of his time (c. 1890–1909).

Biography

Born in Elmira, New York, and educated at Holderness School and Amherst College (c ...

's play ''Major André'' opened on Broadway in November 1903, but was not a success, possibly because the play attempted to portray André as a sympathetic figure.

In Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

's famous short story, ''The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

"The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" is a gothic story by American author Washington Irving, contained in his collection of 34 essays and short stories titled ''The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.'' Written while Irving was living abroad in Birm ...

'', the townspeople describe the site of the capture of Major John André, in particular a tulip-tree, as one of the haunted locations in Sleepy Hollow. Ichabod Crane

Ichabod Crane is a fictional character and the protagonist in Washington Irving's short story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow." Crane is portrayed, in the original work, as well as in most adaptations, as a tall, lanky individual with a scarecro ...

later passes the tree himself just before he encounters the Headless Horseman.

The young adult fiction

Young adult fiction (YA) is a category of fiction written for readers from 12 to 18 years of age. While the genre is primarily targeted at adolescents, approximately half of YA readers are adults.

The subject matter and genres of YA correlate ...

book ''Sophia's War'' by Avi is about a young girl becoming a spy

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

and foiling his plot.

André has been portrayed several times in film and television: by Michael Wilding

Michael Charles Gauntlet Wilding (23 July 1912 – 8 July 1979) was an English stage, television, and film actor. He is best known for a series of films he made with Anna Neagle; he also made two films with Alfred Hitchcock, '' Under Capric ...

as an eloquent and dignified idealist in the 1955 Hollywood film ''The Scarlet Coat

''The Scarlet Coat '' is a 1955 American historical drama and swashbuckler in Eastmancolor and CinemaScope released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, produced by Nicholas Nayfack, directed by John Sturges. It stars Cornel Wilde, Michael Wilding, George Sa ...

''; by JJ Feild

John Joseph Feild (born 1978) is a British-American film, television and theatre actor. He started his television career in 1999. Feild played Fred Garland in Philip Pullman's ''The Ruby in the Smoke'' and ''The Shadow in the North'' television ...

in the TV series '' Turn: Washington's Spies''; by William Beckley in season 4, episode 26 of the sci-fi TV series ''Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea

''Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea'' is a 1961 American science fiction disaster film, produced and directed by Irwin Allen, and starring Walter Pidgeon and Robert Sterling. The supporting cast includes Peter Lorre, Joan Fontaine, Barbara Eden, M ...

''; by Eric Joshua Davis in the TV series '' Sleepy Hollow''; and by John Light in the movie '' Benedict Arnold: A Question of Honor''.

André appears as a non-playable character in the 2012 video game ''Assassin's Creed III

''Assassin's Creed III'' is a 2012 action-adventure video game developed by Ubisoft Montreal and published by Ubisoft for PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, Wii U, and Microsoft Windows. It is the fifth major installment in the ''Assassin's Creed'' serie ...

''.

See also

*Intelligence in the American Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Army and British Army conducted espionage operations against one another to collect military intelligence to inform military operations. In addition, both sides conducted political action, c ...

* John Champe (soldier)

Sergeant Major John Champe (''ca.'' 1752 – 30 September 1798) was an American Revolutionary War senior enlisted soldier in the Continental Army who became a double agent in a failed attempt to capture the American traitor General Benedict Ar ...

* Jane Tuers

Jannetje Van Reypen Tuers was a patriot during the American Revolutionary War and had a role in confirming information about a British conspiracy with Benedict Arnold to take over West Point.

Biography

Jane and her husband Nicholas Tuers (1736/37 ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* ''An Authentic Narrative of the Causes Which Led to the Death of Major Andre, Adjutant-General of His Majesty's Forces in North America'', Joshua Hett Smith (London 1808) * Cray, Robert E. Jr., "Major John Andre and the Three Captors: Class Dynamics and Revolutionary Memory Wars in the Early Republic, 1780–1831", ''Journal of the Early Republic'', Vol. 17, No. 3. Autumn, 1997. University of Pennsylvania Press. * * ''Memoirs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania'' (1858), vol vi, which contains a comprehensive essay by Charles J. Biddle * ''Andreana'', H. W. Smith (Philadelphia, 1865) * ''Two spies'', Lossing (New York, 1886) * ''Life and Career of Major John André'', Sargent, new edition (New York, 1904) * ''The Secret is Out: True Spy Stories'', T. Martini (Boston, 1990) * ''The Execution of MAJOR ANDRE'', John Evangelist Walsh (New York, 2001)Local History: British Agent Detained in Tarrytown, Executed in Rockland

* * * *

Further reading

* *External links

* ttp://www.ushistory.org/march/bio/andre.htm More on his early life {{DEFAULTSORT:Andre, John 1780 deaths 18th-century executions by the United States 18th-century executions by New York (state) American Revolutionary War executions British Army personnel of the American Revolutionary War English people of French descent Executed people from London Burials at Westminster Abbey British people executed abroad British military personnel killed in the American Revolutionary War Cameronians officers Executed spies Benedict Arnold British spies during the American Revolution Huguenot participants in the American Revolution People executed by the United States military by hanging Royal Welch Fusiliers officers 1750s births