James Clerk Maxwell Foundation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation is a registered Scottish charity set up in 1977. By supporting physics and mathematics, it honors one of the greatest physicists,

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation is a registered Scottish charity set up in 1977. By supporting physics and mathematics, it honors one of the greatest physicists,

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation aims to increase the public awareness of the many scientific advances made by Maxwell over his lifetime and to highlight their importance in the world today. It summarizes Maxwell's many innovative technical advances and displays, in Maxwell’s birthplace, the history of Maxwell's family. The Foundation awards grants and prizes and supports mathematical challenges designed to encourage young students to study as mathematicians, scientists and engineers and become leaders in the world.

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation aims to increase the public awareness of the many scientific advances made by Maxwell over his lifetime and to highlight their importance in the world today. It summarizes Maxwell's many innovative technical advances and displays, in Maxwell’s birthplace, the history of Maxwell's family. The Foundation awards grants and prizes and supports mathematical challenges designed to encourage young students to study as mathematicians, scientists and engineers and become leaders in the world.

Maxwell was born at 14 India Street on 13 June 1831. This four-floor townhouse has 3–4 rooms on each floor. The Foundation lets the basement and top floor to tenants and maintains on the ground and first floor a modest museum which can be opened for visits by prior appointment.

Maxwell’s father, John Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie, had previously inherited land at

Maxwell was born at 14 India Street on 13 June 1831. This four-floor townhouse has 3–4 rooms on each floor. The Foundation lets the basement and top floor to tenants and maintains on the ground and first floor a modest museum which can be opened for visits by prior appointment.

Maxwell’s father, John Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie, had previously inherited land at

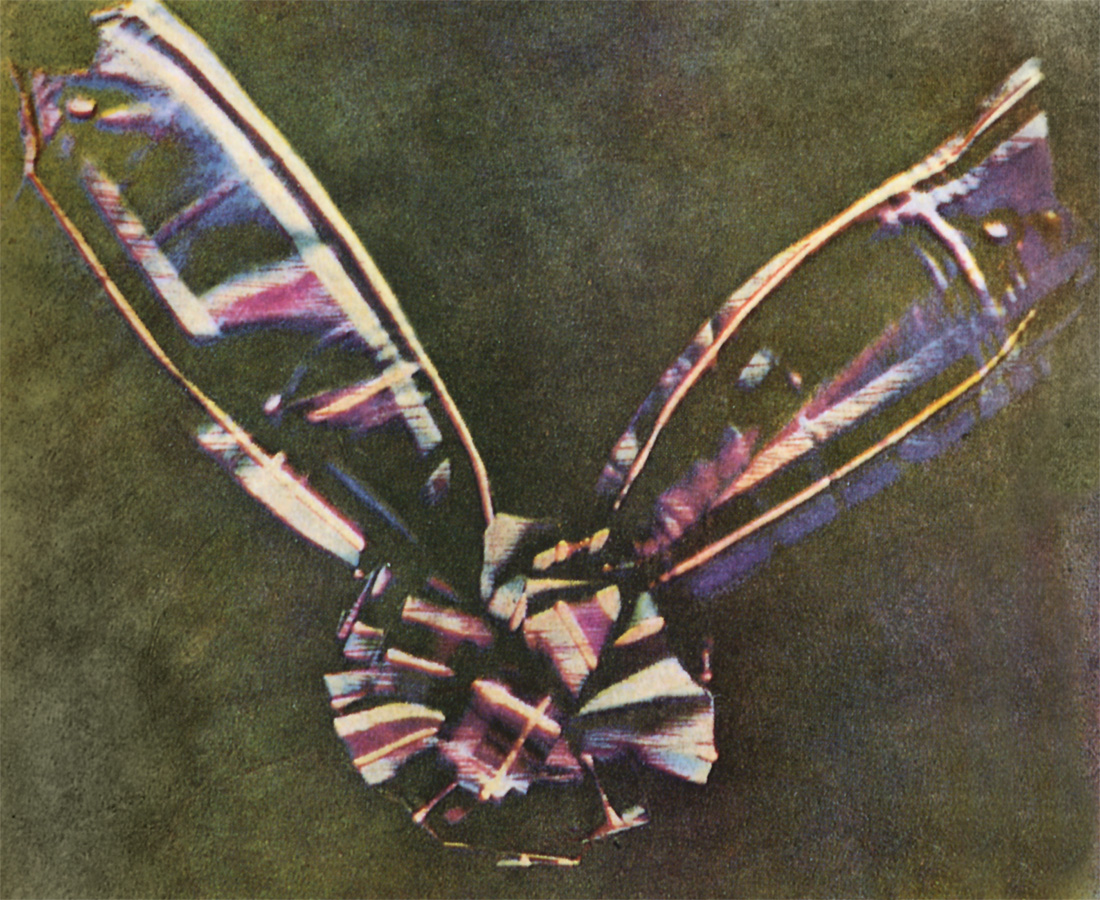

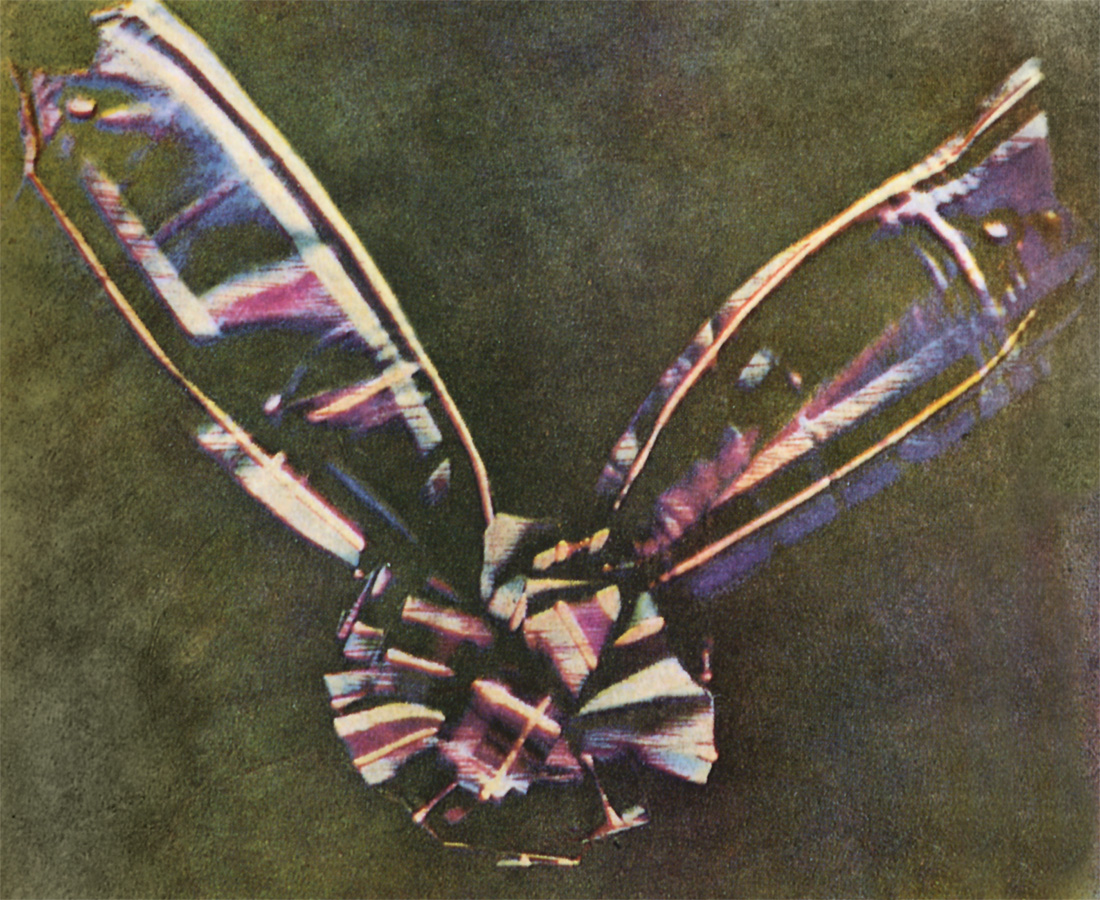

One of Maxwell’s major technical advances is the first full colour projected image produced at a time when only black-and-white photography was known. The projection of this coloured image on a screen was famously demonstrated in 1861 at Faraday's Royal Institution in London. In this, the foundation of virtually all practical colour processes, he made three black-and-white photographic plates which were photographed through red, green and blue filters respectively. He then used three magic lanterns to superimpose these three black-and-white images, each projected through the same red, green and blue filters, to produce the first colour image of the ‘tartan ribbon’. This production of colour images is still used today in printing, digital cameras, televisions, and computers.

The replica of Maxwell’s colour box, which he used to quantitatively analyse and synthesise light colours in order to underpin his observations on colour mixing and colour perception (thereby extending Newton's work on Optics), was produced in the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge University.

One of Maxwell’s major technical advances is the first full colour projected image produced at a time when only black-and-white photography was known. The projection of this coloured image on a screen was famously demonstrated in 1861 at Faraday's Royal Institution in London. In this, the foundation of virtually all practical colour processes, he made three black-and-white photographic plates which were photographed through red, green and blue filters respectively. He then used three magic lanterns to superimpose these three black-and-white images, each projected through the same red, green and blue filters, to produce the first colour image of the ‘tartan ribbon’. This production of colour images is still used today in printing, digital cameras, televisions, and computers.

The replica of Maxwell’s colour box, which he used to quantitatively analyse and synthesise light colours in order to underpin his observations on colour mixing and colour perception (thereby extending Newton's work on Optics), was produced in the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge University.

Maxwell’s most celebrated contribution was in deriving the equations governing electromagnetics ( Maxwell’s equations). In his 1865 paper,

Maxwell’s most celebrated contribution was in deriving the equations governing electromagnetics ( Maxwell’s equations). In his 1865 paper,

The engravings on the staircase walls are from Sir John Herschel's Collection purchased by our founder, Sydney Ross. They sample the history of science and mathematics from Copernicus onwards, arriving at Maxwell’s contemporaries Michael Faraday and Lord Kelvin.

The engravings on the staircase walls are from Sir John Herschel's Collection purchased by our founder, Sydney Ross. They sample the history of science and mathematics from Copernicus onwards, arriving at Maxwell’s contemporaries Michael Faraday and Lord Kelvin.

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation website

Interactive virtual tour of Maxwell's birthplace and museum

Guide to Maxwell's birthplace

1977 establishments in Scotland Organizations established in 1977 Charities based in Edinburgh Museums established in 1993 Historic house museums in Edinburgh Maxwell, James Clark

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation is a registered Scottish charity set up in 1977. By supporting physics and mathematics, it honors one of the greatest physicists,

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation is a registered Scottish charity set up in 1977. By supporting physics and mathematics, it honors one of the greatest physicists, James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and li ...

(1831–1879), and while attempting to increase the public awareness and trust of science. It maintains a small museum

A museum ( ; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or institution that cares for and displays a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance. Many public museums make thes ...

in Maxwell's birthplace. This museum is owned by the Foundation.

Purpose

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation aims to increase the public awareness of the many scientific advances made by Maxwell over his lifetime and to highlight their importance in the world today. It summarizes Maxwell's many innovative technical advances and displays, in Maxwell’s birthplace, the history of Maxwell's family. The Foundation awards grants and prizes and supports mathematical challenges designed to encourage young students to study as mathematicians, scientists and engineers and become leaders in the world.

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation aims to increase the public awareness of the many scientific advances made by Maxwell over his lifetime and to highlight their importance in the world today. It summarizes Maxwell's many innovative technical advances and displays, in Maxwell’s birthplace, the history of Maxwell's family. The Foundation awards grants and prizes and supports mathematical challenges designed to encourage young students to study as mathematicians, scientists and engineers and become leaders in the world.

History

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation was formed in 1977 by the late Sydney Ross, Professor ofColloidal chemistry

Interface and colloid science is an interdisciplinary intersection of branches of chemistry, physics, nanoscience and other fields dealing with colloids, heterogeneous systems consisting of a mechanical mixture of particles between 1 nm and ...

at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, USA. Ross was born in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

and he inherited monies from his late father’s whisky business, Ross, Campbell Ltd.

In 1993, the Foundation acquired 14 India Street, Edinburgh, the birthplace of Maxwell.

Since 1993, the house has been refurbished to its original standard and a small museum has been developed which features Maxwell’s family, life and scientific advances. These have resulted in Maxwell now being recognised as the most famous scientist in the era between Newton and Einstein.

Maxwell's birthplace

Maxwell was born at 14 India Street on 13 June 1831. This four-floor townhouse has 3–4 rooms on each floor. The Foundation lets the basement and top floor to tenants and maintains on the ground and first floor a modest museum which can be opened for visits by prior appointment.

Maxwell’s father, John Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie, had previously inherited land at

Maxwell was born at 14 India Street on 13 June 1831. This four-floor townhouse has 3–4 rooms on each floor. The Foundation lets the basement and top floor to tenants and maintains on the ground and first floor a modest museum which can be opened for visits by prior appointment.

Maxwell’s father, John Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie, had previously inherited land at Corsock

Corsock ( gd, Corsag) is a village in the historical county of Kirkcudbrightshire, Dumfries and Galloway, south-west Scotland. It is located north of Castle Douglas, and the same distance east of New Galloway, on the Urr Water.

Corsock House ...

in Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or ...

and he divided his time between Galloway and his 1820s townhouse in Edinburgh’s New Town. In 1830, John Clerk Maxwell commenced building a new house on his Corsock farm and would later name this Glenlair House

Glenlair, near the village of Corsock in the historical county of Kirkcudbrightshire, in Dumfries and Galloway, was the home of the physicist James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879). The original structure was designed for Maxwell's father by Walter ...

. The Clerk Maxwell family moved permanently to Glenlair when James was two years old. Maxwell’s mother died when he was only eight years old and, two years later, he returned to Edinburgh to attend school at the Edinburgh Academy

The Edinburgh Academy is an independent day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, which was opened in 1824. The original building, on Henderson Row in the city's New Town, is now part of the Senior School. The Junior School is located on Arboretum Ro ...

.

Maxwell studied at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

and the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

and his career followed professorial appointments at Marischal College

Marischal College ( ) is a large granite building on Broad Street in the centre of Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, and since 2011 has acted as the headquarters of Aberdeen City Council. However, the building was constructed for and is on long- ...

Aberdeen, King's College London and the University of Cambridge. While in Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

, Maxwell married the College Principal’s daughter Katherine Dewar.

Museum

The restored entrance hall contains a copy of the bust of Maxwell by Charles d’Orville Pilkington Jackson, the original is located at Marischal College, Aberdeen. The Milestone in Electrical Engineering and Computing plaque by the American Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) commemorates Maxwell’s contributions to electromagnetic theory. Displayed here is a timeline starting with Maxwell’s life and going up to today, where Maxwell’s electromagnetics is central to the performance of cellular mobile phones,GPS

The Global Positioning System (GPS), originally Navstar GPS, is a satellite-based radionavigation system owned by the United States government and operated by the United States Space Force. It is one of the global navigation satellite sy ...

and Radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, we ...

.

Exhibition Room

This room, originally the dining room, contains several family portraits: a copy of James Clerk Maxwell byLowes Cato Dickinson

Lowes Cato Dickinson (27 November 1819 – 15 December 1908) was an English portrait painter and Christian socialist. He taught drawing with John Ruskin and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. He was a founder of the Working Men's College in London.

located in Trinity College, Cambridge; and of Maxwell’s father, John Clerk Maxwell. Early pastels from the Cay’s, his mother’s family, of Maxwell’s uncles, Robert and John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, his aunt Jane and Maxwell’s mother Frances Cay. These are by Maxwell’s maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Cay, there is also a portrait in oils, after Sir Henry Raeburn

Sir Henry Raeburn (; 4 March 1756 – 8 July 1823) was a Scottish portrait painter. He served as Portrait Painter to King George IV in Scotland.

Biography

Raeburn was born the son of a manufacturer in Stockbridge, on the Water of Leith: a ...

, of Elizabeth’s husband Robert Hodshon Cay

Robert Hodshon Cay FSSA LLD (7 July 1758 – 31 March 1810) was Judge Admiral of Scotland overseeing naval trials. He was husband of the artist Elizabeth Liddell, father of John Cay FRSE and maternal grandfather of James Clerk Maxwell.

Life

Ca ...

by Maxwell's cousin, Isabella Cay (1850–1934). The final portrait is of Maxwell’s lifelong friend and scientific colleague Peter Guthrie Tait

Peter Guthrie Tait FRSE (28 April 1831 – 4 July 1901) was a Scottish mathematical physicist and early pioneer in thermodynamics. He is best known for the mathematical physics textbook ''Treatise on Natural Philosophy'', which he co-wrote wi ...

who was the Professor of Natural Philosophy at Edinburgh University.

One of Maxwell’s major technical advances is the first full colour projected image produced at a time when only black-and-white photography was known. The projection of this coloured image on a screen was famously demonstrated in 1861 at Faraday's Royal Institution in London. In this, the foundation of virtually all practical colour processes, he made three black-and-white photographic plates which were photographed through red, green and blue filters respectively. He then used three magic lanterns to superimpose these three black-and-white images, each projected through the same red, green and blue filters, to produce the first colour image of the ‘tartan ribbon’. This production of colour images is still used today in printing, digital cameras, televisions, and computers.

The replica of Maxwell’s colour box, which he used to quantitatively analyse and synthesise light colours in order to underpin his observations on colour mixing and colour perception (thereby extending Newton's work on Optics), was produced in the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge University.

One of Maxwell’s major technical advances is the first full colour projected image produced at a time when only black-and-white photography was known. The projection of this coloured image on a screen was famously demonstrated in 1861 at Faraday's Royal Institution in London. In this, the foundation of virtually all practical colour processes, he made three black-and-white photographic plates which were photographed through red, green and blue filters respectively. He then used three magic lanterns to superimpose these three black-and-white images, each projected through the same red, green and blue filters, to produce the first colour image of the ‘tartan ribbon’. This production of colour images is still used today in printing, digital cameras, televisions, and computers.

The replica of Maxwell’s colour box, which he used to quantitatively analyse and synthesise light colours in order to underpin his observations on colour mixing and colour perception (thereby extending Newton's work on Optics), was produced in the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge University.

Maxwell’s most celebrated contribution was in deriving the equations governing electromagnetics ( Maxwell’s equations). In his 1865 paper,

Maxwell’s most celebrated contribution was in deriving the equations governing electromagnetics ( Maxwell’s equations). In his 1865 paper, A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field

"A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field" is a paper by James Clerk Maxwell on electromagnetism, published in 1865. ''(Paper read at a meeting of the Royal Society on 8 December 1864).'' In the paper, Maxwell derives an electromagnetic wav ...

, (This article followed a 8 December 1864 presentation by Maxwell to the Royal Society.) Maxwell defined electromagnetics in terms of 20 equations, later summarised in his 1873 book Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism. Hendrik Lorentz subsequently reinterpreted these as the fundamental equations of electrodynamics and Oliver Heaviside

Oliver Heaviside FRS (; 18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925) was an English self-taught mathematician and physicist who invented a new technique for solving differential equations (equivalent to the Laplace transform), independently developed ...

developed the notation we use today.

The theory behind Maxwell's equations was the first grand unification theory of the forces of Nature as this theory united the electric and magnetic fields. A person who is stationary may experience only an electric field but a person who is in relative motion may experience an electric current and a magnetic field. Thus the one field (called the electromagnetic field) may appear in different guises.

In his famous 1905 'Special Relativity' paper, Albert Einstein showed that Maxwell's equations were invariant under a Lorentz transformation (as opposed to a Galilean transformation) and, inter alia, used this evidence to support his 'relativity theory' that the Lorentz transformation was the true transformation of Nature (between the viewpoints of two observers, one moving at a constant speed and direction relative to each other).

On display is a replica of part of the balance arm of Maxwell’s apparatus to measure the ratio of electromagnetic to electrostatic units of electrical charge. Maxwell showed mathematically that the numerical value of this ratio was equal to the speed of electromagnetic waves. Maxwell recognised that the speed of electromagnetic waves (as derived from his equations) was also equal to the speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant that is important in many areas of physics. The speed of light is exactly equal to ). According to the special theory of relativity, is the upper limit ...

as measured by Fizeau and as previously measured in the 17th century by Ole Roemer. In his 1865 paper, Maxwell stated the immortal words ''“…it seems we have strong reason to conclude that light itself (including radiant heat and other radiations if any) is an electromagnetic disturbance in the form of waves propagated …according the electromagnetic laws”''. This was stated by the Nobel Laureate physicist Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist, known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of the superfl ...

in 1964 to be the most stunning conclusion of 19th-century theoretical physics!

The display cabinet shows a few pages, on loan from The Edinburgh Academy

The Edinburgh Academy is an independent day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, which was opened in 1824. The original building, on Henderson Row in the city's New Town, is now part of the Senior School. The Junior School is located on Arboretum Roa ...

, of Maxwell’s work on oval curves, where Maxwell simplified earlier work of René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Ma ...

. He presented this work to the Royal Society of Edinburgh (or rather Professor Forbes did as Maxwell, then aged 14, was considered too young!). Maxwell's second scientific paper "The Theory of Rolling Curves" was written at age 17 while at university in Edinburgh. The cabinet displays here 3 of Maxwell's medals: the 1860 Rumford Medal from Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

for colour composition, the 1871 Keith Medal

The Keith Medal was a prize awarded by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy, for a scientific paper published in the society's scientific journals, preference being given to a paper containing a discovery, either in mathe ...

from Royal Society of Edinburgh for forces and frames in structures, and the 1878 Volta Medal from University of Pavia

The University of Pavia ( it, Università degli Studi di Pavia, UNIPV or ''Università di Pavia''; la, Alma Ticinensis Universitas) is a university located in Pavia, Lombardy, Italy. There was evidence of teaching as early as 1361, making it one ...

, when he was awarded an honorary degree.

The Library

This room (originally John Clerk Maxwell's business office when he practised as an advocate in Edinburgh) contains wall displays celebrating Maxwell’s other major scientific achievements: his work ongovernors

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

for machine speed control; Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution

In physics (in particular in statistical mechanics), the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution, or Maxwell(ian) distribution, is a particular probability distribution named after James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann.

It was first defined and use ...

and his contribution to statistical physics; discovery of the form of Saturn's rings

The rings of Saturn are the most extensive ring system of any planet in the Solar System. They consist of countless small particles, ranging in size from micrometers to meters, that orbit around Saturn. The ring particles are made almost entire ...

; contributing to the committee that defined the Ohm

Ohm (symbol Ω) is a unit of electrical resistance named after Georg Ohm.

Ohm or OHM may also refer to:

People

* Georg Ohm (1789–1854), German physicist and namesake of the term ''ohm''

* Germán Ohm (born 1936), Mexican boxer

* Jörg Ohm (b ...

; reciprocal figures or frames for the design of structures such roofs and bridges. The final set of wall panels describes the friezes on his Edinburgh statue placing Maxwell’s contributions in context between Newton and Einstein. The library also contains a selection of books on Maxwell, Newton, Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, (26 June 182417 December 1907) was a British mathematician, mathematical physicist and engineer born in Belfast. Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow for 53 years, he did important ...

, Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

etc.

The Staircase

The engravings on the staircase walls are from Sir John Herschel's Collection purchased by our founder, Sydney Ross. They sample the history of science and mathematics from Copernicus onwards, arriving at Maxwell’s contemporaries Michael Faraday and Lord Kelvin.

The engravings on the staircase walls are from Sir John Herschel's Collection purchased by our founder, Sydney Ross. They sample the history of science and mathematics from Copernicus onwards, arriving at Maxwell’s contemporaries Michael Faraday and Lord Kelvin.

Upper Exhibition Room

The upper exhibition room is the annexe of the original drawing room, and it was in this room that James Clerk Maxwell was born in 1831. It displays material relating to theClerk family

The Clerk family () is a Ghanaian historic family that produced a number of pioneering scholars and clergy on the Gold Coast. Predominantly based in the Ghanaian capital, Accra, the Clerks were traditionally Protestant Christian and affiliated ...

, Maxwell’s childhood, early life and career, including some of his poetry. There is a reproduction of the William Dyce

William Dyce (; 19 September 1806 in Aberdeen14 February 1864) was a Scottish painter, who played a part in the formation of public art education in the United Kingdom, and the South Kensington Schools system. Dyce was associated with the Pre-R ...

portrait of James and his mother, from Birmingham art galleries (Dyce was the brother of Maxwell's aunt). The main display here is of watercolours by Maxwell’s cousin Jemima Wedderburn. Jemima later married Hugh Blackburn, Professor of Mathematics at Glasgow University

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

and a colleague of Lord Kelvin.

Conference Room

The Conference Room, originally the Drawing Room, which is used for receptions and seminars contains a Latin epigram which can be translated as: "From this house of his birth, his name is now widespread – across the entire terrestrial globe and even to the stars". The major painting here (by Lady Lucinda L. Mackay) is of a near neighbour, Nobel Laureate and Honorary Patron of the Foundation, ProfessorPeter Higgs

Peter Ware Higgs (born 29 May 1929) is a British theoretical physicist, Emeritus Professor in the University of Edinburgh,Griggs, Jessica (Summer 2008The Missing Piece ''Edit'' the University of Edinburgh Alumni Magazine, p. 17 and Nobel Prize ...

, whose research led to the search, in the Large Hadron Collider, to confirm the existence of the Higgs boson.

References

{{ReflistExternal links

The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation website

Interactive virtual tour of Maxwell's birthplace and museum

Guide to Maxwell's birthplace

1977 establishments in Scotland Organizations established in 1977 Charities based in Edinburgh Museums established in 1993 Historic house museums in Edinburgh Maxwell, James Clark