Independence of Brazil on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Independence of Brazil comprised a series of political and military events that led to the independence of the

The Portuguese members of the ''Cortes'' showed no respect towards Prince Pedro and openly mocked him. And so the loyalty that Pedro had shown towards the ''Cortes'' gradually shifted to the Brazilian cause. His wife, princess

The Portuguese members of the ''Cortes'' showed no respect towards Prince Pedro and openly mocked him. And so the loyalty that Pedro had shown towards the ''Cortes'' gradually shifted to the Brazilian cause. His wife, princess

Pedro departed to

Pedro departed to  The official separation would only occur on 22 September 1822 in a letter written by Pedro to

The official separation would only occur on 22 September 1822 in a letter written by Pedro to

Upon the declaration of the independence, the authority of the new regime only extended to Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and the adjacent provinces. The rest of Brazil remained firmly under the control of Portuguese juntas and garrisons. It would take a war to put the whole of Brazil under Pedro's control. The fighting began with skirmishes between rival militias in 1822 and lasted until January 1824, when the last Portuguese garrisons and naval units surrendered or left the country.

Meanwhile, the Imperial government had to create a regular

Upon the declaration of the independence, the authority of the new regime only extended to Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and the adjacent provinces. The rest of Brazil remained firmly under the control of Portuguese juntas and garrisons. It would take a war to put the whole of Brazil under Pedro's control. The fighting began with skirmishes between rival militias in 1822 and lasted until January 1824, when the last Portuguese garrisons and naval units surrendered or left the country.

Meanwhile, the Imperial government had to create a regular

Kingdom of Brazil

The Kingdom of Brazil ( pt, Reino do Brasil) was a constituent kingdom of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves.

Creation

The legal entity of the Kingdom of Brazil was created by a law issued by Prince Regent John of Portu ...

from the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves

The United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves was a pluricontinental monarchy formed by the elevation of the Portuguese colony named State of Brazil to the status of a kingdom and by the simultaneous union of that Kingdom of Brazil w ...

as the Brazilian Empire

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories which form modern Brazil and (until 1828) Uruguay. Its government was a representative parliamentary constitutional monarchy under the rule of Emperors Dom P ...

. Most of the events occurred in Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 Federative units of Brazil, states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo (sta ...

, Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, and São Paulo

São Paulo (, ; Portuguese for 'Saint Paul') is the most populous city in Brazil, and is the capital of the state of São Paulo, the most populous and wealthiest Brazilian state, located in the country's Southeast Region. Listed by the GaWC a ...

between 1821–1824.

It is celebrated on 7 September

Events Pre-1600

* 70 – A Roman army under Titus occupies and plunders Jerusalem.

* 878 – Louis the Stammerer is crowned as king of West Francia by Pope John VIII.

* 1159 – Pope Alexander III is chosen.

*1191 – Third C ...

, although there is a controversy whether the real independence happened after the Siege of Salvador

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterize ...

on July 2 of 1823 in Salvador, Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 Federative units of Brazil, states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo (sta ...

where the independence war was fought. However, September 7th is the anniversary of the date in 1822 that prince regent Dom Pedro declared Brazil's independence from his royal family in Portugal and the former United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and Algarves. Formal recognition came with a treaty three years later, signed by the new Empire of Brazil and the Kingdom of Portugal

The Kingdom of Portugal ( la, Regnum Portugalliae, pt, Reino de Portugal) was a monarchy in the western Iberian Peninsula and the predecessor of the modern Portuguese Republic. Existing to various extents between 1139 and 1910, it was also kno ...

in late 1825.

Background

The land now called Brazil was claimed by the Kingdom of Portugal in April 1500, on the arrival of the Portuguese naval fleet commanded byPedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Álvares Cabral ( or ; born Pedro Álvares de Gouveia; c. 1467 or 1468 – c. 1520) was a Portuguese nobleman, military commander, navigator and explorer regarded as the European discoverer of Brazil. He was the first human in ...

. The Portuguese encountered Indigenous nations divided into several tribes, most of whom shared the same Tupi–Guarani languages

Tupi–Guarani () is the most widely distributed subfamily of the Tupian languages of South America. It consists of about fifty languages, including Guarani and Old Tupi.

The words ''petunia, jaguar, piranha, ipecac, tapioca, jacaranda, anhing ...

family, and shared and disputed the territory. But the Portuguese, like the Spanish in their North American territories, had brought diseases with them against which many Indians were helpless due to lack of immunity. Measles, smallpox, tuberculosis, and influenza killed tens of thousands.

Though the first settlement was founded in 1532, colonization only effectively started in 1534 when King John III divided the territory into fifteen hereditary captaincies. This arrangement proved problematic, however, and in 1549 the king assigned a Governor-General to administer the entire colony. The Portuguese assimilated some of the native tribes while others slowly disappeared in long wars or by European diseases to which they had no immunity.

By the mid-16th century, sugar had become Brazil's main export due to the increasing international demand. To profit from the situation, by 1700 over 963,000 African slaves had been brought across the Atlantic Ocean to work in the plantations of Brazil. More Africans were brought to Brazil up until that date than to all the other places in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

(and the entire Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the term We ...

) combined.

Through wars against the French, the Portuguese slowly expanded their territory to the southeast, taking Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

in 1567, and to the northwest, taking São Luís in 1615. They sent military expeditions to the northwest of the South American continent to the Amazon River

The Amazon River (, ; es, Río Amazonas, pt, Rio Amazonas) in South America is the largest river by discharge volume of water in the world, and the disputed longest river system in the world in comparison to the Nile.

The headwaters of t ...

basin rainforest and conquered competing English and Dutch strongholds, founding villages and forts from 1669. In 1680 they reached the far southeast and founded Colônia do Sacramento on the bank of the Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and fo ...

, in the Banda Oriental

Banda Oriental, or more fully Banda Oriental del Uruguay (Eastern Bank), was the name of the South American territories east of the Uruguay River and north of Río de la Plata that comprise the modern nation of Uruguay; the modern state of Rio Gra ...

region (present-day Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

).

At the end of the 17th century, sugar exports started to decline, but beginning in the 1690s, the discovery of gold by explorers in the region that would later be called Minas Gerais

Minas Gerais () is a state in Southeastern Brazil. It ranks as the second most populous, the third by gross domestic product (GDP), and the fourth largest by area in the country. The state's capital and largest city, Belo Horizonte (literally ...

, current Mato Grosso

Mato Grosso ( – lit. "Thick Bush") is one of the states of Brazil, the third largest by area, located in the Central-West region. The state has 1.66% of the Brazilian population and is responsible for 1.9% of the Brazilian GDP.

Neighboring ...

and Goiás

Goiás () is a Brazilian state located in the Center-West region. Goiás borders the Federal District and the states of (from north clockwise) Tocantins, Bahia, Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso do Sul and Mato Grosso. The state capital is Goiânia. ...

saved the colony from imminent collapse. From all over Brazil, as well as from Portugal, thousands of immigrants came to the mines in an early gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

.

The Spanish tried to prevent Portuguese expansion northwest, west, southwest and southeast into the territory that belonged to them according to the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Emp ...

division of the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

by the Bishop and Pope of Rome, Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI ( it, Alessandro VI, va, Alexandre VI, es, Alejandro VI; born Rodrigo de Borja; ca-valencia, Roderic Llançol i de Borja ; es, Rodrigo Lanzol y de Borja, lang ; 1431 – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Churc ...

(1431-1503, reigned 1492-1503) and succeeded in conquering the Banda Oriental region in 1777. However, this was in vain as the Treaty of San Ildefonso, signed in the same year, confirmed Portuguese sovereignty over all lands proceeding from its territorial expansion, thus creating most of the current Brazilian southeastern border.

During the French invasion of Portugal

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

by Emperor Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in 1807, the Portuguese royal family (House of Braganza

The Most Serene House of Braganza ( pt, Sereníssima Casa de Bragança), also known as the Brigantine Dynasty (''Dinastia Brigantina''), is a dynasty of emperors, kings, princes, and dukes of Portuguese origin which reigned in Europe and the Ame ...

) fled across the Atlantic Ocean with the help of the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

to Brazil, establishing Rio de Janeiro as the de facto capital of the Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the l ...

during the ensuing worldwide Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

(1803–1815). This had the side effect of soon creating within Brazil many of the institutions required to exist as an independent state; most importantly, it freed Brazil to trade with other nations at will.

After Napoleon's Imperial French army was finally defeated at Waterloo in June 1815, in order to maintain the capital in Brazil and allay Brazilian fears of being returned to colonial status, King John VI of Portugal

, house = Braganza

, father = Peter III of Portugal

, mother = Maria I of Portugal

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Queluz Palace, Queluz, Portugal

, death_date =

, death_place = Bemposta Palace, Lisbon, Portugal

...

raised the de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

status of Brazil to an equal kingdom

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

and integral part of the new United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves, rather than a mere colony, a status which it enjoyed for the next seven years, sending his son, Dom Pedro

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for '' Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, mean ...

, as prince regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch regnant, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness ...

.

Path to independence

Portuguese ''Cortes''

In 1820 theConstitutionalist Revolution

The Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932 (sometimes also referred to as Paulista War or Brazilian Civil War) is the name given to the uprising of the population of the Brazilian state of São Paulo against the Brazilian Revolution of 1930 when ...

erupted in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

. The movement initiated by the liberal constitutionalists resulted in the meeting of the ''Cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border of ...

'' (or Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

), that would have to create the kingdom's first constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

. The ''Cortes'' at the same time demanded the return of King Dom Dom or DOM may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Dom (given name), including fictional characters

* Dom (surname)

* Dom La Nena (born 1989), stage name of Brazilian-born cellist, singer and songwriter Dominique Pinto

* Dom people, an et ...

John VI, who had been living in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

since 1808, who elevated Brazil to a kingdom as part of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves

The United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves was a pluricontinental monarchy formed by the elevation of the Portuguese colony named State of Brazil to the status of a kingdom and by the simultaneous union of that Kingdom of Brazil w ...

in 1815 and who nominated his son and heir prince Dom Pedro

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for '' Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, mean ...

as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

, to govern Brazil in his place on 7 March 1821. The king left for Europe on 26 April, while Dom Pedro remained in Brazil governing it with the aid of the ministers of the Kingdom (Interior) and Foreign Affairs, of War, of Navy and of Finance.

The Portuguese military officers headquartered in Brazil were completely sympathetic to the Constitutionalist movement in Portugal. The main leader of the Portuguese officers, General Jorge de Avilez Zuzarte de Sousa Tavares

Jorge de Avilez Zuzarte de Sousa Tavares (28 March 1785 – 15 February 1845) was a Portugal, Portuguese military officer and statesman. He fought in the Peninsular War and in the Portuguese conquest of the Banda Oriental.

Early career

Jorge de A ...

, forced the prince to dismiss and banish from the country the ministers of Kingdom and Finance. Both were loyal allies of Pedro, who had become a pawn in the hands of the military. The humiliation suffered by the prince, who swore he would never yield to the pressure of the military again, would have a decisive influence on his abdication ten years later. Meanwhile, on 30 September 1821, the ''Cortes'' approved a decree that subordinated the governments of the Brazilian provinces directly to Portugal. Prince Pedro became for all purposes only the governor of Rio de Janeiro Province.Lustosa, p. 117 Other decrees that came after ordered his return to Europe and also extinguished the judicial courts created by João VI in 1808.Lustosa, p.119

Dissatisfaction over the ''Cortes'' measures among most residents in Brazil (both Brazilian-born and Portuguese-born) rose to a point that it soon became publicly known. Two groups that opposed the ''Cortes actions to gradually undermine Brazilian sovereignty appeared: Liberals, led by Joaquim Gonçalves Ledo

Joaquim Gonçalves Ledo (11 December 1781 – 9 May 1847) was a Brazilian journalist and politician. He was active in the freemasonry movement in Brazil. He was one of the leaders of the more liberal and democrat faction during the confused period ...

(with the support of the Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

s), and the Bonifacians, led by José Bonifácio de Andrada

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

. The factions, with quite different views of what Brazil could and should be, agreed only on their desire to keep Brazil co-equal with Portugal, united in a sovereign monarchy, rather than Brazil being merely provinces controlled from Lisbon.

Avilez rebellion

The Portuguese members of the ''Cortes'' showed no respect towards Prince Pedro and openly mocked him. And so the loyalty that Pedro had shown towards the ''Cortes'' gradually shifted to the Brazilian cause. His wife, princess

The Portuguese members of the ''Cortes'' showed no respect towards Prince Pedro and openly mocked him. And so the loyalty that Pedro had shown towards the ''Cortes'' gradually shifted to the Brazilian cause. His wife, princess Maria Leopoldina of Austria

Dona Maria Leopoldina of Austria (22 January 1797 – 11 December 1826) was the first Empress of Brazil as the wife of Emperor Dom Pedro I from 12 October 1822 until her death. She was also Queen of Portugal during her husband's brief r ...

, favoured the Brazilian side and encouraged him to remain in the country which the Liberals and Bonifacians openly called for. Pedro's reply to the Cortes came on 9 January 1822, when, according to newspapers, he said: "As it is for the good of all and for the nation's general happiness, I am ready: Tell the people that I will stay".

After Pedro's decision to defy the ''Cortes'' and remain in Brazil, around 2,000 men led by Jorge Avilez rioted before concentrating on mount Castelo, which was soon surrounded by 10,000 armed Brazilians, led by the Royal Police Guard. Dom Pedro then "dismissed" the Portuguese commanding general and ordered him to remove his soldiers across the bay to Niterói

Niterói (, ) is a Municipalities of Brazil, municipality of the state of Rio de Janeiro (state), Rio de Janeiro in the Southeast Region, Brazil, southeast region of Brazil. It lies across Guanabara Bay facing the city of Rio de Janeiro and forms ...

, where they would await transport to Portugal.

Jose Bonifácio was nominated minister of Kingdom and Foreign Affairs on 18 January 1822. Bonifácio soon established a fatherlike relationship with Pedro, who began to consider the experienced statesman

A statesman or stateswoman typically is a politician who has had a long and respected political career at the national or international level.

Statesman or Statesmen may also refer to:

Newspapers United States

* ''The Statesman'' (Oregon), a n ...

his greatest ally. Gonçalves Ledo and the Liberals tried to minimize the close relationship between Bonifácio and Pedro, offering to the prince the title of Perpetual Defender of Brazil.Lustosa, p. 143Armitage. p. 61 For the Liberals, the creation of a Constituent Assembly to prepare a Brazilian constitution was necessary, while the Bonifacians preferred that Pedro create the constitution himself, to avoid the possibility of anarchy similar to the first years of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

.

The prince acquiesced to the Liberals’ desires, and signed a decree on 3 June 1822 calling for the election of deputies that would gather in a Constituent and Legislative General Assembly in Brazil.

From United Kingdom under Portugal to independent empire

Pedro departed to

Pedro departed to São Paulo Province

São Paulo Province was one of the provinces of Brazil

The provinces of Brazil were the primary subdivisions of the country during the period of the Empire of Brazil (1822 - 1889).

On February 28, 1821, the provinces were established in the Kin ...

to secure the province's loyalty to the Brazilian cause. He reached its capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

on 25 August and remained there until 5 September. While on his way back to Rio de Janeiro on 7 September he received at Ipiranga mail from José Bonifácio and his wife, Leopoldina. The letter told him that the ''Cortes'' had annulled all acts of the Bonifácio cabinet, removed Pedro's remaining powers, and ordered him to return to Portugal. It was clear that independence was the only option left, which his wife supported. Pedro turned to his companions, that included his Guard of Honor

A guard of honour (British English, GB), also honor guard (American English, US), also ceremonial guard, is a group of people, usually military in nature, appointed to receive or guard a head of state or other dignitaries, the fallen in war, o ...

, and said: "Friends, the Portuguese ''Cortes'' want to enslave and pursue us. From today on our relations are broken. No ties can unite us anymore". He removed his blue-white armband that symbolized Portugal: "Armbands off, soldiers. Hail to the independence, to freedom and to the separation of Brazil from Portugal!" He unsheathed his sword affirming that "For my blood, my honor, my God, I swear to give Brazil freedom," and later cried out: "Brazilians, Independence or death!". This event is known as the "Cry of Ipiranga

Crying is the dropping of tears (or welling of tears in the eyes) in response to an emotional state, or pain. Emotions that can lead to crying include sadness, anger, and even happiness. The act of crying has been defined as "a complex secreto ...

", the declaration of Brazil's independence,

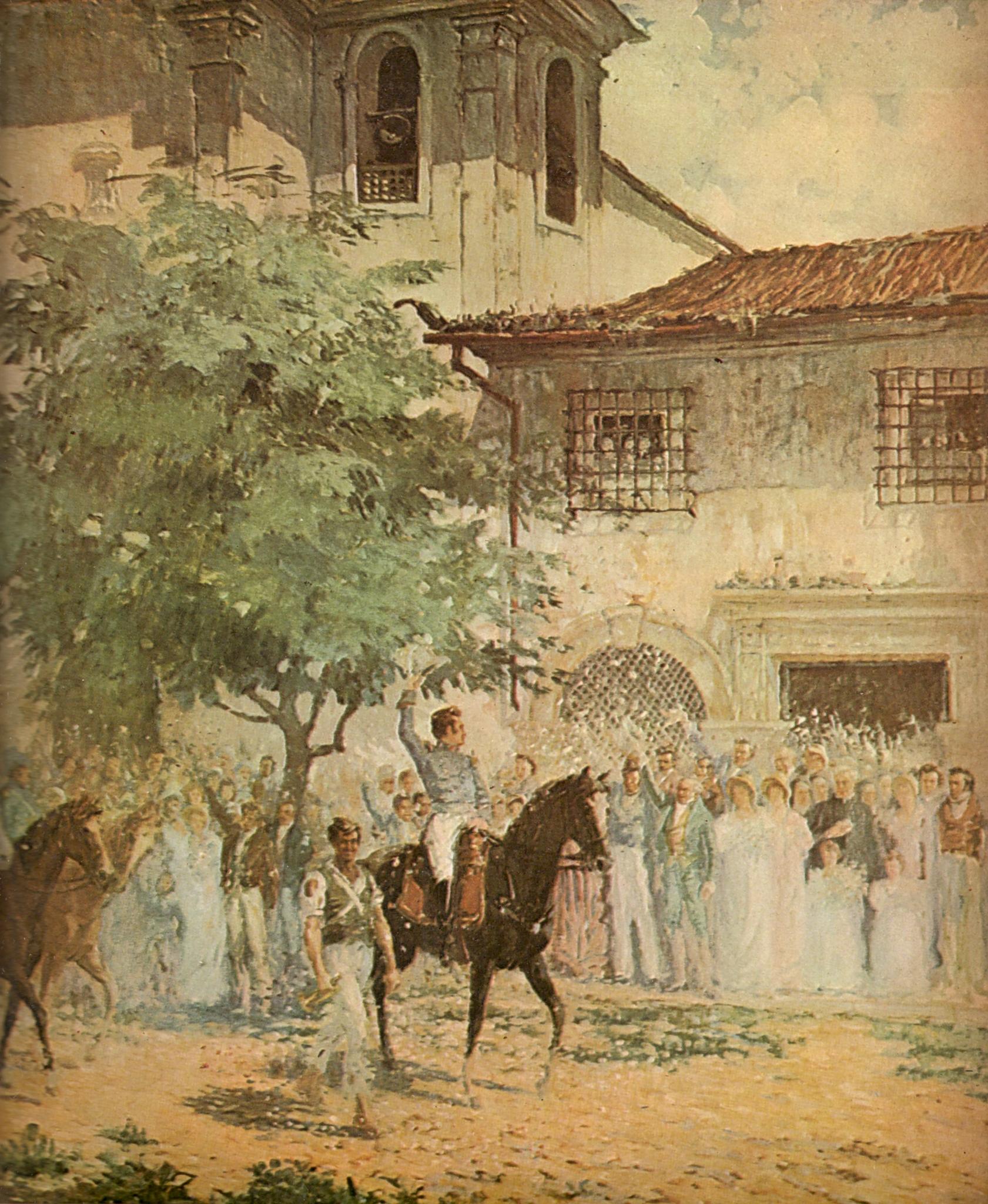

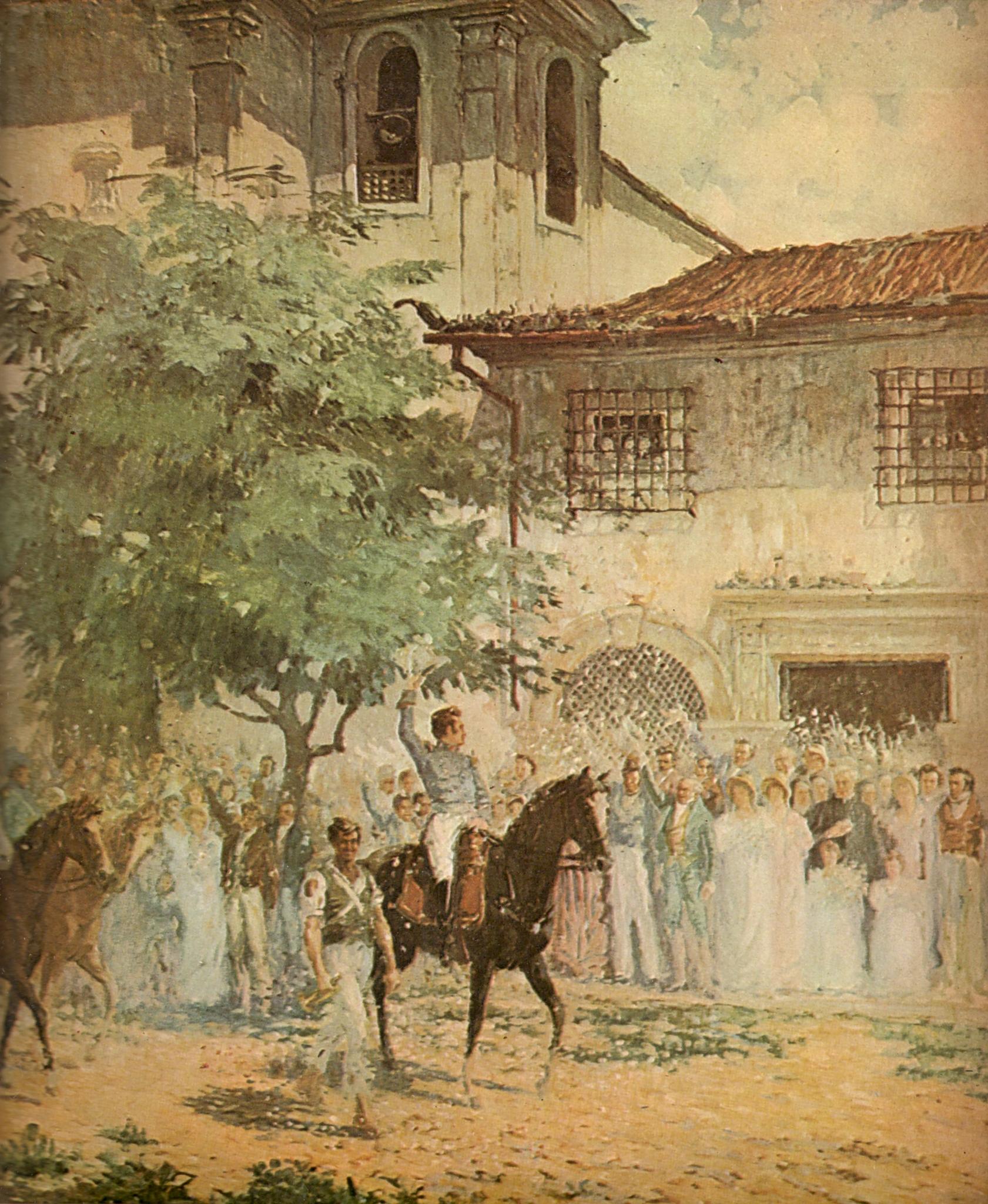

Returning to the city of São Paulo

São Paulo (, ; Portuguese for 'Saint Paul') is the most populous city in Brazil, and is the capital of the state of São Paulo, the most populous and wealthiest Brazilian state, located in the country's Southeast Region. Listed by the GaWC a ...

on the night of 7 September 1822, Pedro

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for '' Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, mean ...

and his companions announced the news of Brazilian independence from Portugal. The Prince was received with great popular celebration and was called not only "King of Brazil", but also "Emperor of Brazil".Vianna, p. 408

Pedro

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for '' Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, mean ...

returned to Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

on 14 September and in the following days the Liberals had distributed pamphlets (written by Joaquim Gonçalves Ledo

Joaquim Gonçalves Ledo (11 December 1781 – 9 May 1847) was a Brazilian journalist and politician. He was active in the freemasonry movement in Brazil. He was one of the leaders of the more liberal and democrat faction during the confused period ...

) that suggested that the Prince should be named Constitutional Emperor. On 17 September the President of the Municipal Chamber

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality'' may also mean the go ...

of Rio de Janeiro, José Clemente Pereira

José Clemente Pereira, known as José Pequeno (José, the short) (17 February 1787 - 10 March 1854), was a Portuguese-born Brazilian magistrate and politician who fought in the Peninsular War and of high relevance to the Empire of Brazil, in ad ...

, sent to the other Chambers of the country the news that the Acclamation

An acclamation is a form of election that does not use a ballot. It derives from the ancient Roman word ''acclamatio'', a kind of ritual greeting and expression of approval towards imperial officials in certain social contexts.

Voting Voice vot ...

would occur on the anniversary birthday? of Pedro on 12 October.

The official separation would only occur on 22 September 1822 in a letter written by Pedro to

The official separation would only occur on 22 September 1822 in a letter written by Pedro to João VI

, house = Braganza

, father = Peter III of Portugal

, mother = Maria I of Portugal

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Queluz Palace, Queluz, Portugal

, death_date =

, death_place = Bemposta Palace, Lisbon, Portugal ...

. In it, Pedro still calls himself Prince Regent and his father is considered the King of the independent Brazil. On 12 October 1822, in the Field of Santana (later known as Field of the Acclamation) Prince Pedro was acclaimed Dom Pedro I, Constitutional Emperor and Perpetual Defender of Brazil. It was at the same time the beginning of Pedro's reign and also of the Empire of Brazil

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories which form modern Brazil and (until 1828) Uruguay. Its government was a representative parliamentary constitutional monarchy under the rule of Emperors Dom Pe ...

. However, the Emperor made it clear that although he accepted the emperorship, if João VI returned to Brazil he would step down from the throne in favor of his father.

The reason for the imperial title was that the title of king would symbolically mean a continuation of the Portuguese dynastic tradition and perhaps of the feared absolutism, while the title of emperor derived from popular acclamation as in Ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 B ...

or at least reigning through popular sanction as in the case of Napoleon. On 1 December 1822, Pedro I was crowned and consecrated.

International recognition

It is disputed which countries were the first to recognize the independence of Brazil. According to historian Toby Green, the African states of Dahomey and Onim were the first two to recognize the new empire in 1822 and 1823 respectively. These states had traditionally maintained close diplomatic and economic contacts with South America. In contrast, researcher Rodrigo Wiese Randig argued that the first country to recognize Brazil was theUnited Provinces of the Río de la Plata

The United Provinces of the Río de la Plata ( es, link=no, Provincias Unidas del Río de la Plata), earlier known as the United Provinces of South America ( es, link=no, Provincias Unidas de Sudamérica), was a name adopted in 1816 by the Cong ...

around June 1823, followed by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

in May 1824, and the Kingdom of Benin

The Kingdom of Benin, also known as the Edo Kingdom, or the Benin Empire ( Bini: ') was a kingdom within what is now southern Nigeria. It has no historical relation to the modern republic of Benin, which was known as Dahomey from the 17th ce ...

in July 1824.

War of Independence

Upon the declaration of the independence, the authority of the new regime only extended to Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and the adjacent provinces. The rest of Brazil remained firmly under the control of Portuguese juntas and garrisons. It would take a war to put the whole of Brazil under Pedro's control. The fighting began with skirmishes between rival militias in 1822 and lasted until January 1824, when the last Portuguese garrisons and naval units surrendered or left the country.

Meanwhile, the Imperial government had to create a regular

Upon the declaration of the independence, the authority of the new regime only extended to Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and the adjacent provinces. The rest of Brazil remained firmly under the control of Portuguese juntas and garrisons. It would take a war to put the whole of Brazil under Pedro's control. The fighting began with skirmishes between rival militias in 1822 and lasted until January 1824, when the last Portuguese garrisons and naval units surrendered or left the country.

Meanwhile, the Imperial government had to create a regular Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

and Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

. Forced enlistment was widespread, extending to foreign immigrants, and Brazil made use of slaves in militias, as well as freeing slaves to enlist them in army and navy. The campaigns on land and sea covered the vast territories of Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 Federative units of Brazil, states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo (sta ...

, Cisplatina

Cisplatina () was a Brazilian province in existence from 1821 to 1828 created by the Luso-Brazilian invasion of the Banda Oriental. From 1815 until 1822 Brazil was a constituent kingdom of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algar ...

, Grão-Pará, Maranhão

Maranhão () is a state in Brazil. Located in the country's Northeast Region, it has a population of about 7 million and an area of . Clockwise from north, it borders on the Atlantic Ocean for 2,243 km and the states of Piauí, Tocantins and ...

, Pernambuco

Pernambuco () is a state of Brazil, located in the Northeast region of the country. With an estimated population of 9.6 million people as of 2020, making it seventh-most populous state of Brazil and with around 98,148 km², being the 19 ...

, Ceará

Ceará (, pronounced locally as or ) is one of the 26 states of Brazil, located in the northeastern part of the country, on the Atlantic coast. It is the eighth-largest Brazilian State by population and the 17th by area. It is also one of the ...

and Piauí

Piaui (, ) is one of the states of Brazil, located in the country's Northeast Region. The state has 1.6% of the Brazilian population and produces 0.7% of the Brazilian GDP.

Piaui has the shortest coastline of any coastal Brazilian state at 66&n ...

.

By 1822, Brazilian forces were firmly in control of Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

and the central area of Brazil. Loyal militias began insurrections in the aforementioned territories, but strong, and regularly reinforced Portuguese garrisons in the port cities of Salvador, Montevideo

Montevideo () is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

, São Luís and Belém

Belém (; Portuguese for Bethlehem; initially called Nossa Senhora de Belém do Grão-Pará, in English Our Lady of Bethlehem of Great Pará) often called Belém of Pará, is a Brazilian city, capital and largest city of the state of Pará in t ...

continued to dominate the adjacent areas and to pose the threat of a reconquest that the irregular Brazilian militias and guerrilla forces, which were loosely besieging them by land supported by newly created units of the Brazilian army, would be unable to prevent.

For the Brazilians, the answer to this stalemate was to seize control of the sea. Eleven former Portuguese warships, great and small, had fallen into Brazilian hands in Rio de Janeiro and these formed the basis of a new navy. The problem was manpower: the crews of these ships were largely Portuguese who were openly mutinous, and although many Portuguese naval officers had declared allegiance to Brazil their loyalty could not be relied on. The Brazilian Government solved the problem by recruiting 50 officers and 500 seamen in secret in London and Liverpool, many of them veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, and appointed Thomas Cochrane as commander-in-chief.

On 1 April 1823, a Brazilian squadron of 6 ships sailed for Bahia. After an initial disappointing engagement with a superior Portuguese fleet, Cochrane blockaded Salvador. Deprived now of supplies and reinforcements by sea and besieged by the Brazilian army on land, on 2 July the Portuguese forces abandoned Bahia in a convoy of 90 ships. Leaving the frigate ‘Niteroi’ under Captain John Taylor to harry them to the coasts of Europe, Cochrane then sailed north to São Luís (Maranhão). There he tricked the Portuguese garrison into evacuating Maranhão by pretending that a huge Brazilian fleet and army were over the horizon. He then sent Captain John Pascoe Grenfell to play the same trick on the Portuguese in Belém do Pará at the mouth of the Amazon. By November 1823, the whole of the north of Brazil was under Brazilian control, and the following month, the demoralized Portuguese also evacuated Montevideo and the Cisplatine Province. By 1824, Brazil was free of all enemy troops and was ''de facto'' independent.

There are still today no reliable statistics

Statistics (from German language, German: ''wikt:Statistik#German, Statistik'', "description of a State (polity), state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of ...

related to the numbers of, for example, the total of the war casualties. However, based upon historical registration and contemporary reports of some battles of this war as well as upon the admitted numbers in similar fights that happened in these times around the globe, and considering how long the Brazilian independence war lasted (22 months), estimates of all killed in action on both sides are placed from around 5,700 to 6,200.

In Pernambuco

* Siege of RecifeIn Piauí and Maranhão

* Battle of Jenipapo * Siege of CaxiasIn Grão-Pará

* Siege of BelémIn Bahia

*Battle of Pirajá

The Battle of Pirajá ( pt, Batalha de Pirajá) was a battle fought as part of the Independence of Bahia and more broadly, as part of the War of Independence of Brazil. It was fought in Pirajá, now a neighborhood of the city of Salvador, Bahi ...

* Battle of Itaparica

The Battle of Itaparica was fought in the then province of Bahia, from 7 to 9 January 1823, between the Brazilian Army and Armada and the Portuguese Army and Navy during the Brazilian War of Independence.

Despite the fact that the independence ...

* Battle of 4 May

* Siege of Salvador

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterize ...

In Cisplatina

*Siege of Montevideo (1823)

The siege of Montevideo occurred during the War of Independence of Brazil, during which the Brazilian Army under Carlos Frederico Lecor attempted to capture the city of Montevideo in Cisplatina (now Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Or ...

Peace treaty and aftermath

The last Portuguese soldiers left Brazil in 1824. The Treaty of Rio de Janeiro recognizing Brazil's independence was signed by Brazil and Portugal on 29 August 1825.The Brazilian aristocracy had its wish: Brazil made a transition to independence with comparatively little disruption and bloodshed. But this meant that independent Brazil retained its colonial social structure: monarchy, slavery, large landed estates, monoculture, an inefficient agricultural system, a highly stratified society, and a free population that was 90 percent illiterate.

See also

*Empire of Brazil

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories which form modern Brazil and (until 1828) Uruguay. Its government was a representative parliamentary constitutional monarchy under the rule of Emperors Dom Pe ...

* Colonial Brazil

Colonial Brazil ( pt, Brasil Colonial) comprises the period from 1500, with the arrival of the Portuguese, until 1815, when Brazil was elevated to a kingdom in union with Portugal as the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. Durin ...

* Cry of Ipiranga

Crying is the dropping of tears (or welling of tears in the eyes) in response to an emotional state, or pain. Emotions that can lead to crying include sadness, anger, and even happiness. The act of crying has been defined as "a complex secreto ...

* History of Brazil

* Treaty of Rio de Janeiro (1825)

The Treaty of Rio de Janeiro is the treaty between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Empire of Brazil, signed August 29, 1825, which recognized Brazil as an independent nation, formally ending the Brazilian war of independence.

The treaty was ra ...

* Independence Day (Brazil)

The Independence Day of Brazil ( pt, Dia da Independência, ), commonly called Sete de Setembro (, 'Seven of September'), is a national holiday observed in Brazil on 7 September of every year. The date celebrates Brazil's Declaration of Indepen ...

Further reading

* Gomes, Laurentino, '' 1822''Footnotes

References

* Armitage, John. ''História do Brasil''. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1981. * Barman, Roderick J. ''Citizen Emperor: Pedro II and the Making of Brazil, 1825–1891.'' Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999. * Diégues, Fernando. ''A revolução brasílica''. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 2004. * Dolhnikoff, Miriam. ''Pacto imperial: origens do federalismo no Brasil do século XIX''. São Paulo: Globo, 2005. * * Gomes, Laurentino. ''1822''. Nova Fronteira, 2010. * Holanda, Sérgio Buarque de. ''O Brasil Monárquico: o processo de emancipação''. 4. ed. São Paulo: Difusão Européia do Livro, 1976. * Lima, Manuel de Oliveira. ''O movimento da independência''. 6. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks, 1997. * Lustosa, Isabel. ''D. Pedro I''. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2007. * Vainfas, Ronaldo. ''Dicionário do Brasil Imperial''. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 2002. * Vianna, Hélio. ''História do Brasil: período colonial, monarquia e república''. 15. ed. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1994. *External links

{{Authority control 1820s conflicts Empire of Brazil Military history of Brazil Latin American wars of independence 1822 in Brazil Separatism in Brazil Separatism in Portugal Wars involving Brazil Wars involving Portugal Wars of independence Brazil–Portugal relations 1822 in international relations Pedro I of Brazil it:Impero del Brasile#Indipendenza brasiliana