History of universities in Scotland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of universities in Scotland includes the development of all universities and university colleges in Scotland, between their foundation between the fifteenth century and the present day. Until the fifteenth century, those Scots who wished to attend university had to travel to England, or to the Continent. This situation was transformed by the founding of St John's College, St Andrews in 1418 by

The history of universities in Scotland includes the development of all universities and university colleges in Scotland, between their foundation between the fifteenth century and the present day. Until the fifteenth century, those Scots who wished to attend university had to travel to England, or to the Continent. This situation was transformed by the founding of St John's College, St Andrews in 1418 by

From the end of the eleventh century, universities had been founded across Europe, developing as semi-autonomous centres of learning, often teaching theology, mathematics, law and medicine. Until the fifteenth century, those Scots who wished to attend university had to travel to England, to

From the end of the eleventh century, universities had been founded across Europe, developing as semi-autonomous centres of learning, often teaching theology, mathematics, law and medicine. Until the fifteenth century, those Scots who wished to attend university had to travel to England, to

This situation was transformed by the founding of St John's College, St Andrews in 1418.

This situation was transformed by the founding of St John's College, St Andrews in 1418.

The

The

The history of universities in Scotland includes the development of all universities and university colleges in Scotland, between their foundation between the fifteenth century and the present day. Until the fifteenth century, those Scots who wished to attend university had to travel to England, or to the Continent. This situation was transformed by the founding of St John's College, St Andrews in 1418 by

The history of universities in Scotland includes the development of all universities and university colleges in Scotland, between their foundation between the fifteenth century and the present day. Until the fifteenth century, those Scots who wished to attend university had to travel to England, or to the Continent. This situation was transformed by the founding of St John's College, St Andrews in 1418 by Henry Wardlaw

Henry Wardlaw (died 6 April 1440) was a Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish church leader, Bishop of St Andrews and founder of the University of St Andrews.

Ancestors

He was descended from an ancient Saxon family which came to Scotland with Edgar ...

, bishop of St. Andrews. St Salvator's College

St Salvator's College was a college of the University of St Andrews in St Andrews, Scotland. Founded in 1450, it is the oldest of the university's colleges. In 1747 it merged with St Leonard's College to form United College.

History

St ...

was added to St. Andrews in 1450. The other great bishoprics followed, with the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

being founded in 1451 and King's College, Aberdeen

King's College in Old Aberdeen, Scotland, the full title of which is The University and King's College of Aberdeen (''Collegium Regium Abredonense''), is a formerly independent university founded in 1495 and now an integral part of the Universi ...

in 1495. Initially, these institutions were designed for the training of clerics, but they would increasingly be used by laymen. International contacts helped integrate Scotland into a wider European scholarly world and would be one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

were brought into Scottish intellectual life in the sixteenth century.

St Leonard's College was founded in St Andrews in 1512 and St John's College as St Mary's College, St Andrews was re-founded in 1538, as a humanist academy for the training of clerics. Public lectures that were established in Edinburgh in the 1540s would eventually become the University of Edinburgh in 1582. After the Reformation, Scotland's universities underwent reforms associated with Andrew Melville, who was influenced by the anti-Aristotelian Petrus Ramus

Petrus Ramus (french: Pierre de La Ramée; Anglicized as Peter Ramus ; 1515 – 26 August 1572) was a French humanist, logician, and educational reformer. A Protestant convert, he was a victim of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.

Early life ...

. In 1617 James VI decreed that the town college of Edinburgh should be known as King James's College. In 1641, the two colleges at Aberdeen were united by decree of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

(r. 1625–49), to form the "King Charles University of Aberdeen". Under the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

(1652–60), the universities saw an improvement in their funding. After the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

there was a purge of Presbyterians from the universities, but most of the intellectual advances of the preceding period were preserved. The colleges at St. Andrews were demerged. The five Scottish university colleges recovered from the disruption of the civil war years and Restoration with a lecture-based curriculum that was able to embrace economics and science, offering a high-quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry.

In the eighteenth century the universities went from being small and parochial institutions, largely for the training of clergy and lawyers, to major intellectual centres at the forefront of Scottish identity and life, seen as fundamental to democratic principles and the opportunity for social advancement for the talented. Chairs of medicine were founded at all the university towns. By the 1740s Edinburgh medical school

The University of Edinburgh Medical School (also known as Edinburgh Medical School) is the medical school of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and the United Kingdom and part of the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine. It was esta ...

was the major centre of medicine in Europe and was a leading centre in the Atlantic world. Access to Scottish universities was probably more open than in contemporary England, Germany or France. Attendance was less expensive and the student body more representative of society as a whole. The system was flexible and the curriculum became a modern philosophical and scientific one, in keeping with contemporary needs for improvement and progress. Scotland reaped the intellectual benefits of this system in its contribution to the European Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

. Many of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment ( sco, Scots Enlichtenment, gd, Soillseachadh na h-Alba) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century ...

were university professors, who developed their ideas in university lectures.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Scotland's five university colleges had no entrance exam, students typically entered at ages of 15 or 16, attended for as little as two years, chose which lectures to attend and left without qualifications. The curriculum was dominated by divinity and the law and there was a concerted attempt to modernise the curriculum, particularly by introducing degrees in the physical sciences and the need to reform the system to meet the needs of the emerging middle classes and the professions. The result of these reforms was a revitalisation of the Scottish university system, which expanded to 6,254 students by the end of the century and produced leading figures in both the arts and sciences. In the first half of the twentieth century Scottish universities fell behind those in England and Europe in terms of participation and investment. After the Robbins Report

The Robbins Report (the report of the Committee on Higher Education, chaired by Lord Robbins) was commissioned by the British government and published in 1963. The committee met from 1961 to 1963. After the report's publication, its conclusions wer ...

of 1963 there was a rapid expansion in higher education in Scotland. By the end of the decade the number of Scottish Universities had doubled. New universities included the University of Dundee, Strathclyde, Heriot-Watt

Heriot-Watt University ( gd, Oilthigh Heriot-Watt) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was established in 1821 as the School of Arts of Edinburgh, the world's first mechanics' institute, and subsequently granted univ ...

, Stirling. From the 1970s the government preferred to expand higher education in the non-university sector and by the late 1980s roughly half of students in higher education were in colleges. In 1992, under the Further and Higher Education Act 1992

The Further and Higher Education Act 1992 made changes in the funding and administration of further education and higher education within England and Wales, with consequential effects on associated matters in Scotland which had previously been ...

, the distinction between universities and colleges was removed, creating new universities at Abertay, Glasgow Caledonian, Napier Napier may refer to:

People

* Napier (surname), including a list of people with that name

* Napier baronets, five baronetcies and lists of the title holders

Given name

* Napier Shaw (1854–1945), British meteorologist

* Napier Waller (1893–19 ...

, Paisley and Robert Gordon Robert Gordon may refer to:

Entertainment

* Robert Gordon (actor) (1895–1971), silent-film actor

* Robert Gordon (director) (1913–1990), American director

* Robert Gordon (singer) (1947–2022), American rockabilly singer

* Robert Gordon (scr ...

.

History

Middle Ages

Background

From the end of the eleventh century, universities had been founded across Europe, developing as semi-autonomous centres of learning, often teaching theology, mathematics, law and medicine. Until the fifteenth century, those Scots who wished to attend university had to travel to England, to

From the end of the eleventh century, universities had been founded across Europe, developing as semi-autonomous centres of learning, often teaching theology, mathematics, law and medicine. Until the fifteenth century, those Scots who wished to attend university had to travel to England, to Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

or Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, or to the Continent. Just over 1,000 students have been identified as doing so between the twelfth century and 1410. Among the destinations Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

was the most important, but also Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

, Orléans

Orléans (;"Orleans"

(US) and Wittenberg Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon language, Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the Ri ...

, (US) and Wittenberg Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon language, Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the Ri ...

Louvain

Leuven (, ) or Louvain (, , ; german: link=no, Löwen ) is the capital and largest city of the province of Flemish Brabant in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is located about east of Brussels. The municipality itself comprises the historic c ...

and Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 68–72.

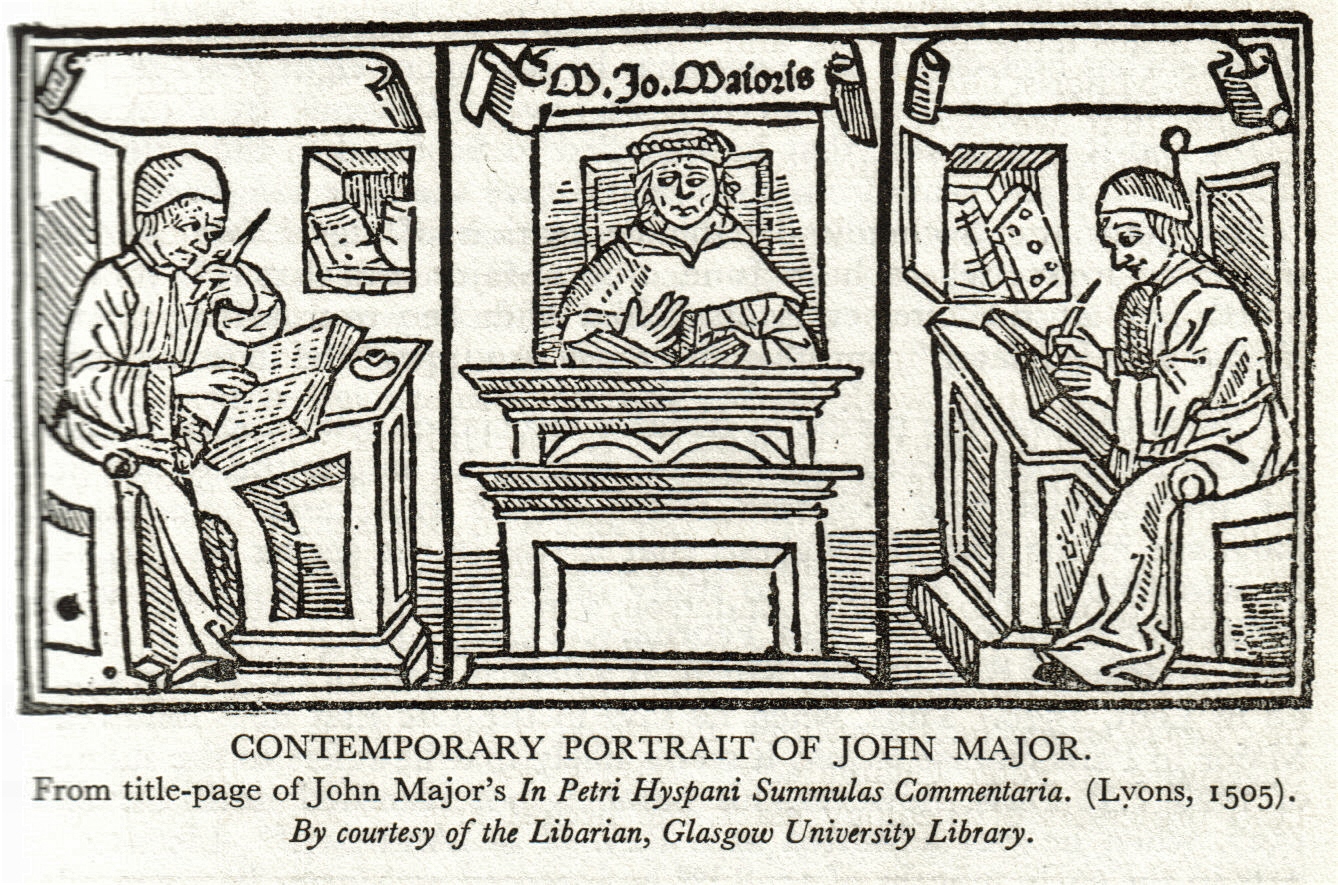

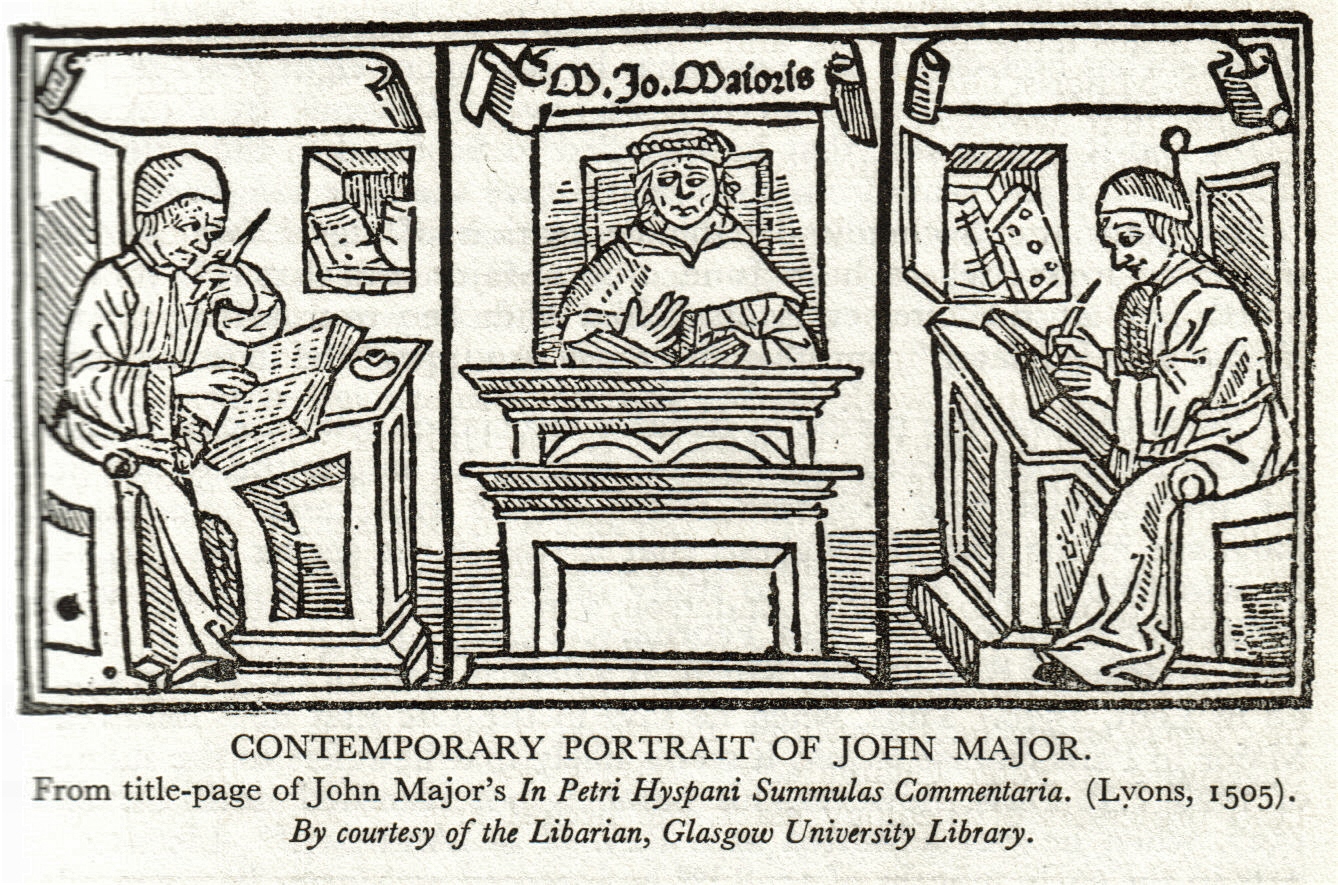

Among these travelling scholars, the most important intellectual figure was John Duns Scotus (c. 1266–1308), who studied at Oxford, Cambridge and Paris. He probably died at Cologne in 1308, after becoming a major influence on late medieval religious thought.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (St. Martin's Press, 1997), , p. 119. After the outbreak of the Wars of Independence (1296–1357), with occasional exceptions under safe conduct, English universities were closed to Scots and continental universities became more significant.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (St. Martin's Press, 1997), , pp. 124–5. Some Scottish scholars became teachers in continental universities. At Paris, this included John de Rait

John de Rait ''Raith, Rathe, Rate, Rathetwas a 14th-century Scottish cleric. The name "Rait" probably links him to the village of Rait in Gowrie, although the name "Rath" – Gaelic for a type of enclosed settlement – is common to many settlem ...

(died c. 1355) and Walter Wardlaw

Walter Wardlaw (died ) was a 14th-century bishop of Glasgow in Scotland.

Biography

Wardlaw was the son of a Sir Henry Wardlaw of Torry, a middling knight of Fife. Before becoming bishop, Walter was a canon of Glasgow, a Master of Theology and ...

(died c. 1387) in the 1340s and 1350s, William de Tredbrum in the 1380s and Laurence de Lindores (1372–1437) in the early 1500s. The continued movement to other universities produced a school of Scottish nominalists

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are at least two main versions of nominalism. One version denies the existence of universalsthings th ...

at Paris in the early sixteenth century, of which John Mair (1467–1550) was the most important figure. He had probably studied at a Scottish grammar school and then Cambridge, before moving to Paris where he matriculated in 1493.

First Scottish universities

This situation was transformed by the founding of St John's College, St Andrews in 1418.

This situation was transformed by the founding of St John's College, St Andrews in 1418. Henry Wardlaw

Henry Wardlaw (died 6 April 1440) was a Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish church leader, Bishop of St Andrews and founder of the University of St Andrews.

Ancestors

He was descended from an ancient Saxon family which came to Scotland with Edgar ...

, bishop of St. Andrews, petitioned the anti-Pope Benedict XIII during the later stages of the Great Western Schism, when Scotland was one of his few remaining supporters. Wardlaw argued that Scottish scholars in other universities were being persecuted for their loyalty to the anti-Pope. St Salvator's College

St Salvator's College was a college of the University of St Andrews in St Andrews, Scotland. Founded in 1450, it is the oldest of the university's colleges. In 1747 it merged with St Leonard's College to form United College.

History

St ...

was added to St. Andrews in 1450. The other great bishoprics followed, with the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

being founded in 1451 and King's College, Aberdeen

King's College in Old Aberdeen, Scotland, the full title of which is The University and King's College of Aberdeen (''Collegium Regium Abredonense''), is a formerly independent university founded in 1495 and now an integral part of the Universi ...

in 1495. Both were also papal foundations, by Nicholas V and Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI ( it, Alessandro VI, va, Alexandre VI, es, Alejandro VI; born Rodrigo de Borja; ca-valencia, Roderic Llançol i de Borja ; es, Rodrigo Lanzol y de Borja, lang ; 1431 – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Churc ...

respectively.J. Durkan, "Universities: to 1720", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 610–12. St. Andrews was deliberately modelled on Paris, and although Glasgow adopted the statues of the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna ( it, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna, UNIBO) is a public research university in Bologna, Italy. Founded in 1088 by an organised guild of students (''studiorum''), it is the oldest university in continuo ...

, there, like Aberdeen, there was an increasing Parisian influence, partly because all its early regents had been educated in Paris. Initially, these institutions were designed for the training of clerics, but they would increasingly be used by laymen who began to challenge the clerical monopoly of administrative posts in government and law. They provided only basic degrees. Those wanting to study for the more advanced degrees that were common amongst European scholars still needed to go to universities in other countries. As a result, Scottish scholars continued to visit the Continent and returned to English universities after they reopened to Scots in the late fifteenth century.

By the fifteenth century, beginning in northern Italy, universities had become strongly influenced by humanist thinking. This put an emphasis on classical authors, questioning some of the accepted certainties of established thinking and manifesting itself in the teaching of new subjects, particularly through the medium of the Greek language. However, in this period, Scottish universities largely had a Latin curriculum, designed for the clergy, civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civic virtue, or civility

*Civil action, or lawsuit

* Civil affairs

*Civil and political rights

*Civil disobedience

*Civil engineering

*Civil (journalism), a platform for independent journalism

*Civilian, someone not a membe ...

and common lawyers. They did not teach the Greek that was fundamental to the new humanist scholarship, focusing on metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

and putting a largely unquestioning faith in the works of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, whose authority would be challenged in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 183–4. Towards the end of the fifteenth century, a humanist influence was becoming more evident. A major figure was Archibald Whitelaw, a teacher at St. Andrews and Cologne who later became a tutor to the young James III and served as royal secretary from 1462 to 1493.A. Thomas, "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, ''The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), , pp. 196–7. By 1497, the humanist and historian Hector Boece, born in Dundee and who had studied at Paris, returned to become the first principal at the new university of Aberdeen. In 1518 Mair returned to Scotland to become principal of the University of Glasgow. He transferred to St. Andrews in 1523 and in 1533 he was made Provost of St Salvator's College. While in Scotland his students included John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

and George Buchanan. These international contacts helped integrate Scotland into a wider European scholarly world and would be one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life in the sixteenth century.

Early modern era

Renaissance

The

The civic values

Civil society can be understood as the "third sector" of society, distinct from government and business, and including the family and the private sphere.Hector Boece, born in Dundee and who had studied at Paris, returned to become the first principal at the new university of Aberdeen. Another major figure was Archibald Whitelaw, a teacher at St. Andrews and Cologne who later became a tutor to the young James III and served as royal secretary from 1462 to 1493. King's College Aberdeen was refounded in 1515. In addition to the basic arts curriculum it offered theology, civil and canon law and medicine. St Leonard's College was founded in Aberdeen in 1511 by Archbishop Alexander Stewart. John Douglas led the refoundation of St John's College as St Mary's College, St Andrews in 1538, as a humanist academy for the training of clerics, with a stress on biblical study. Robert Reid,

King James VI's major contribution to the universities was to combat militant

King James VI's major contribution to the universities was to combat militant

In the eighteenth century the universities went from being small and parochial institutions, largely for the training of clergy and lawyers, to major intellectual centres at the forefront of Scottish identity and life, seen as fundamental to democratic principles and the opportunity for social advancement for the talented. Chairs of medicine were founded at Marsichial College (1700), Glasgow (1713), St. Andrews (1722) and a chair of chemistry and medicine at Edinburgh (1713). It was Edinburgh's

In the eighteenth century the universities went from being small and parochial institutions, largely for the training of clergy and lawyers, to major intellectual centres at the forefront of Scottish identity and life, seen as fundamental to democratic principles and the opportunity for social advancement for the talented. Chairs of medicine were founded at Marsichial College (1700), Glasgow (1713), St. Andrews (1722) and a chair of chemistry and medicine at Edinburgh (1713). It was Edinburgh's  Many of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment were university professors, who developed their ideas in university lectures. The first major philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment was Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746), who held the Chair of Philosophy at the

Many of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment were university professors, who developed their ideas in university lectures. The first major philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment was Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746), who held the Chair of Philosophy at the

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Scotland's five university colleges had about 3,000 students between them. They had no entrance exam, students typically entered at ages of 15 or 16, attended for as little as two years, chose which lectures to attend and left without qualifications. Although Scottish universities had gained a formidable reputation in the eighteenth century, the curriculum was dominated by divinity and the law and there was a concerted attempt to modernise the curriculum, particularly by introducing degrees in the physical sciences and the need to reform the system to meet the needs of the emerging middle classes and the professions. The result was two commissions of inquiry in 1826 and 1876 and reforming acts of parliament in

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Scotland's five university colleges had about 3,000 students between them. They had no entrance exam, students typically entered at ages of 15 or 16, attended for as little as two years, chose which lectures to attend and left without qualifications. Although Scottish universities had gained a formidable reputation in the eighteenth century, the curriculum was dominated by divinity and the law and there was a concerted attempt to modernise the curriculum, particularly by introducing degrees in the physical sciences and the need to reform the system to meet the needs of the emerging middle classes and the professions. The result was two commissions of inquiry in 1826 and 1876 and reforming acts of parliament in  The University of St Andrews was at a low point in its fortunes in the early part of the century. It was restructured by commissioners appointed under the 1858 act and began a revival. It pioneered the admission of women to Scottish universities, creating the

The University of St Andrews was at a low point in its fortunes in the early part of the century. It was restructured by commissioners appointed under the 1858 act and began a revival. It pioneered the admission of women to Scottish universities, creating the  The result of these reforms was a revitalisation of the Scottish university system, which expanded to 6,254 students by the end of the century and produced leading figures in both the arts and sciences. The chair of Engineering at Glasgow became highly distinguished under its second incumbent

The result of these reforms was a revitalisation of the Scottish university system, which expanded to 6,254 students by the end of the century and produced leading figures in both the arts and sciences. The chair of Engineering at Glasgow became highly distinguished under its second incumbent

From 1901 large numbers of students received bursaries from the

From 1901 large numbers of students received bursaries from the

Statistics Publication Notice Lifelong Learning Series: Students In Higher Education At Scottish Institutions

' (2001). Retrieved 25 May 2011.

Abbot of Kinloss

The Abbot of Kinloss (later Commendator of Kinloss) was the head of the property and Cistercian monastic community of Kinloss Abbey, Moray, founded by King David I of Scotland around 1151 by monks from Melrose Abbey. The abbey was transformed in ...

and later Bishop of Orkney

The Bishop of Orkney was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of Orkney, one of thirteen medieval bishoprics of Scotland. It included both Orkney and Shetland. It was based for almost all of its history at St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall.

The bi ...

, was responsible in the 1520s and 1530s for bringing the Italian humanist Giovanni Ferrario to teach at Kinloss Abbey

Kinloss Abbey is a Cistercian abbey at Kinloss in the county of Moray, Scotland.

The abbey was founded in 1150 by King David I and was first colonised by monks from Melrose Abbey. It received its Papal Bull from Pope Alexander III in 1174, and ...

, where he established an impressive library and wrote works of Scottish history and biography. Reid was also instrumental in organising the public lectures that were established in Edinburgh in the 1540s on law, Greek, Latin and philosophy, under the patronage of the queen consort Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (french: Marie de Guise; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was a French noblewoman of the House of Guise, a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine and one of the most powerful families in France. She ...

. These developed into the "Tounis College" of the city, which would eventually become the University of Edinburgh.

Reformation

In the mid-sixteenth century, Scotland underwent aProtestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

that rejected Papal authority and many aspects of Catholic theology and practice. It created a predominately Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

national church, known as the kirk, which was strongly Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

in outlook, severely reducing the powers of bishops, although not initially abolishing them. After the Reformation, Scotland's universities underwent a series of reforms associated with Andrew Melville, who returned from Geneva to become principal of the University of Glasgow in 1574. A distinguished linguist, philosopher and poet, he had trained in Paris and studied law at Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglomerat ...

, before moving to Geneva and developing an interest in Protestant theology. Influenced by the anti-Aristotelian Petrus Ramus

Petrus Ramus (french: Pierre de La Ramée; Anglicized as Peter Ramus ; 1515 – 26 August 1572) was a French humanist, logician, and educational reformer. A Protestant convert, he was a victim of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.

Early life ...

, he placed an emphasis on simplified logic and elevated languages and sciences to the same status as philosophy, allowing accepted ideas in all areas to be challenged. He introduced new specialist teaching staff, replacing the system of "regenting", where one tutor took the students through the entire arts curriculum. Metaphysics were abandoned and Greek became compulsory in the first year followed by Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

, Syriac and Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, launching a new fashion for ancient and biblical languages. Enrollment rates at the University of Glasgow had been declining before his arrival, but students now began to arrive in large numbers. He assisted in the reconstruction of Marischal College

Marischal College ( ) is a large granite building on Broad Street in the centre of Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, and since 2011 has acted as the headquarters of Aberdeen City Council. However, the building was constructed for and is on long- ...

, Aberdeen, founded as a second university college in the city in 1593 by George Keith, 5th Earl Marischal

The title of Earl Marischal was created in the Peerage of Scotland for William Keith, the Great Marischal of Scotland.

History

The office of Marischal of Scotland (or ''Marascallus Scotie'' or ''Marscallus Scotiae'') had been hereditary, held by ...

, and, to do for St Andrews what he had done for Glasgow, he was appointed Principal of St Mary's College, St Andrews in 1580. In 1582, Edinburgh town council received a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

from King James VI for the establishment of a university, while earlier university had been created through papal bulls. Instruction at the resulting ''Tounis College'' began in 1583, and the institution eventually became the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

. Melville's reforms produced a revitalisation of all Scottish universities, which were now providing a quality of education equal to the most esteemed higher education institutions anywhere in Europe.

Seventeenth century

King James VI's major contribution to the universities was to combat militant

King James VI's major contribution to the universities was to combat militant Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

ism by insisting that the catechism ''God and the King'' must be read in the schools and universities. He also decreed, in 1617, that the town college of Edinburgh should be known as King James's College. In 1641, the two colleges at Aberdeen were united by decree of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

(r. 1625–49), to form the "King Charles University of Aberdeen".D. Ditchburn, "Educating the Elite: Aberdeen and Its Universities”, in E. P. Dennison, D. Ditchburn and M. Lynch, eds, ''Aberdeen Before 1800: A New History'' (Dundurn, 2002), , p. 332. Under the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

(1652–60), the universities saw an improvement in their funding, as they were given income from deaneries, defunct bishoprics and the excise, allowing the completion of buildings including the college in the High Street in Glasgow. They were still largely seen as training schools for clergy, and came under the control of the hard line Protesters

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of coopera ...

, who were generally favoured by the regime because of their greater antipathy to royalism, with leading protester Patrick Gillespie being made Principal at Glasgow in 1652.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 227–8. After the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

there was a purge of Presbyterians from the universities, but most of the intellectual advances of the preceding period were preserved.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (Random House, 2011), , p. 262. There was considerable mistrust between the two colleges in Aberdeen, which was sufficient to produce an armed riot over the poaching of students in 1659. The two institutions were formally demerged by the Rescissory Act 1661.

The five Scottish university colleges recovered from the disruption of the civil war years and Restoration with a lecture-based curriculum that was able to embrace economics and science, offering a high-quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry.R. Anderson, "The history of Scottish Education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, ''Scottish Education: Post-Devolution'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), , pp. 219–28. All saw the establishment or re-establishment of chairs of mathematics. The first was at Marshall College in 1613. A university chair was added at St. Andrews in 1668, at Edinburgh in 1674 and at Glasgow in 1691. The chair at Glasgow was first taken by the polymath George Sinclair, who had been deposed from his position in philosophy for his Presbyterianism in 1666, but was able to return after the Glorious Revolution marked a move against episcopalianism. A further chair would be added at King's College Aberdeen in 1703. Astronomy was facilitated by the building of observatories

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysical, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed. His ...

at St. Andrews (c. 1677) and at King's College (1675) and Marischal College (1694) in Aberdeen. Robert Sibbald

Sir Robert Sibbald (15 April 1641 – August 1722) was a Scottish physician and antiquary.

Life

He was born in Edinburgh, the son of David Sibbald (brother of Sir James Sibbald) and Margaret Boyd (January 1606 – 10 July 1672). Educated at th ...

was appointed as the first Professor of Medicine at Edinburgh and he co-founded the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (RCPE) is a medical royal college in Scotland. It is one of three organisations that sets the specialty training standards for physicians in the United Kingdom. It was established by Royal charter ...

in 1681.T. M. Devine, "The rise and fall of the Scottish Enlightenment", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, ''The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), , p. 373. These developments helped the universities to become major centres of medical education and would put Scotland at the forefront of Enlightenment thinking.

Modern era

Eighteenth century

medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

, founded in 1732, that came to dominate. By the 1740s it had displaced Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration wit ...

as the major centre of medicine in Europe and was a leading centre in the Atlantic world. The universities still had their difficulties. The economic down turn in the mid-century forced the closure of St Leonard's College in St Andrews, whose properties and staff were merged into St Salvator's College to form the United College of St Salvator and St Leonard.

Access to Scottish universities was probably more socially open than in contemporary England, Germany or France. Attendance was less expensive and the student body more representative of society as a whole. Humbler students were aided by a system of bursaries established for the training of the clergy. In this period residence became divorced from the colleges and students were able to live much more cheaply and largely unsupervised, at home, with friends or in lodgings in the university towns. The system was flexible and the curriculum became a modern philosophical and scientific one, in keeping with contemporary needs for improvement and progress. Scotland reaped the intellectual benefits of this system in its contribution to the European Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

. A. Herman, '' How the Scots Invented the Modern World'' (London: Crown Publishing Group, 2001), .

Many of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment were university professors, who developed their ideas in university lectures. The first major philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment was Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746), who held the Chair of Philosophy at the

Many of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment were university professors, who developed their ideas in university lectures. The first major philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment was Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746), who held the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

from 1729 to 1746. He was a moral philosopher who produced alternatives to the ideas of Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influent ...

. One of his major contributions to world thought was the utilitarian and consequentialist

In ethical philosophy, consequentialism is a class of normative ethics, normative, Teleology, teleological ethical theories that holds that the wikt:consequence, consequences of one's Action (philosophy), conduct are the ultimate basis for judgm ...

principle that virtue is that which provides, "the greatest happiness for the greatest numbers". Much of what is incorporated in the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific m ...

(the nature of knowledge, evidence, experience, and causation) and some modern attitudes towards the relationship between science and religion were developed by his protégés David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment philo ...

(1711–76) and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

(1723–90).. Hugh Blair

Hugh Blair FRSE (7 April 1718 – 27 December 1800) was a Scottish minister of religion, author and rhetorician, considered one of the first great theorists of written discourse.

As a minister of the Church of Scotland, and occupant of the Ch ...

(1718–1800) was a minister of the Church of Scotland and held the Chair of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres at the University of Edinburgh. He produced an edition of the works of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and is best known for ''Sermons'' (1777–1801), a five-volume endorsement of practical Christian morality, and Lectures on Rhetoric and ''Belles Lettres'' (1783), an essay on literary composition, which was to have a major impact on the work of Adam Smith. He was also one of the figures who first drew the Ossian

Ossian (; Irish Gaelic/Scottish Gaelic: ''Oisean'') is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as ''Fingal'' (1761) and ''Temora'' (1763), and later combined under t ...

cycle of James Macpherson to public attention.

Hume became a major figure in the sceptical philosophical and empiricist

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

traditions of philosophy. His scepticism prevented him from obtaining chairs at Glasgow and Edinburgh. He and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed what he called a 'science of man

'' A Treatise of Human Nature: Being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects'' (1739–40) is a book by Scottish philosopher David Hume, considered by many to be Hume's most important work and one of the ...

',. which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson

Adam Ferguson, (Scottish Gaelic: ''Adhamh MacFhearghais''), also known as Ferguson of Raith (1 July N.S./20 June O.S. 1723 – 22 February 1816), was a Scottish philosopher and historian of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Ferguson was sympathet ...

, John Millar and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behave in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norm (social), norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissancein the " ...

. Indeed, modern sociology largely originated from this movement. Adam Smith's ''The Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', generally referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is the ''magnum opus'' of the Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith. First published in 1 ...

'' (1776) is considered to be the first work of modern economics. It had an immediate impact on British economic policy

The economy of governments covers the systems for setting levels of taxation, government budgets, the money supply and interest rates as well as the labour market, national ownership, and many other areas of government interventions into the e ...

and still frames twenty-first century discussions on globalisation

Globalization, or globalisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide. The term ''globalization'' first appeared in the early 20t ...

and tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s.M. Fry, ''Adam Smith's Legacy: His Place in the Development of Modern Economics'' (London: Routledge, 1992), . The focus of the Scottish Enlightenment ranged from intellectual and economic matters to the specifically scientific as in the work of William Cullen

William Cullen FRS FRSE FRCPE FPSG (; 15 April 17105 February 1790) was a Scottish physician, chemist and agriculturalist, and professor at the Edinburgh Medical School. Cullen was a central figure in the Scottish Enlightenment: He was Dav ...

, physician and chemist, James Anderson, an agronomist, Joseph Black, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

and chemist, and James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role i ...

, the first modern geologist.J. Repcheck, ''The Man Who Found Time: James Hutton and the Discovery of the Earth's Antiquity'' (Cambridge, MA: Basic Books, 2003), , pp. 117–43.

Nineteenth century

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Scotland's five university colleges had about 3,000 students between them. They had no entrance exam, students typically entered at ages of 15 or 16, attended for as little as two years, chose which lectures to attend and left without qualifications. Although Scottish universities had gained a formidable reputation in the eighteenth century, the curriculum was dominated by divinity and the law and there was a concerted attempt to modernise the curriculum, particularly by introducing degrees in the physical sciences and the need to reform the system to meet the needs of the emerging middle classes and the professions. The result was two commissions of inquiry in 1826 and 1876 and reforming acts of parliament in

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Scotland's five university colleges had about 3,000 students between them. They had no entrance exam, students typically entered at ages of 15 or 16, attended for as little as two years, chose which lectures to attend and left without qualifications. Although Scottish universities had gained a formidable reputation in the eighteenth century, the curriculum was dominated by divinity and the law and there was a concerted attempt to modernise the curriculum, particularly by introducing degrees in the physical sciences and the need to reform the system to meet the needs of the emerging middle classes and the professions. The result was two commissions of inquiry in 1826 and 1876 and reforming acts of parliament in 1858

Events

January–March

* January –

**Benito Juárez (1806–1872) becomes Liberal President of Mexico. At the same time, conservatives install Félix María Zuloaga (1813–1898) as president.

**William I of Prussia becomes regent f ...

and 1889

Events

January–March

* January 1

** The total solar eclipse of January 1, 1889 is seen over parts of California and Nevada.

** Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka experiences a vision, leading to the start of the Ghost Dance movement in the ...

.

The curriculum and system of graduation were reformed. Entrance examinations that were equivalent to the School Leaving Certificate were introduced and average ages of entry rose to 17 or 18. Standard patterns of graduation in the arts curriculum offered three-year ordinary and four-year honours degrees.R. Anderson, "The history of Scottish education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, ''Scottish Education: Post-Devolution'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), , p. 224. There was resistance among professors, particularly among chairs of divinity and classics, to the introduction of new subjects, especially the physical sciences. The crown established Regius chair

A Regius Professor

is a university professor who has, or originally had, royal patronage or appointment. They are a unique feature of academia in the United Kingdom and Ireland. The first Regius Professorship was in the field of medicine, and ...

s, all in the sciences, including medicine, chemistry, natural history and botany. The chair of Engineering at Glasgow was the first of its kind in the world. By the 1870s the physical sciences were well established in Scottish universities, whereas in England the battle to modernise the curriculum would not be complete until the end of the century.O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, ''Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), , pp. 147–50. The new separate science faculties were able to move away from the compulsory Latin, Greek and philosophy of the old MA curriculum. Under the commissions, all the universities were restructured. They were given Courts, which included external members and who oversaw the finances of the institution. Students' representative council

{{Unreferenced, date=July 2014A students' representative council, also known as a students' administrative council, represents student interests in the government of a university, school or other educational institution. Generally the SRC forms par ...

s were founded in 1884 and ratified under the 1889 act. Under this act new arts subjects were established, with chairs in Modern History, French, German and Political Economy.

The University of St Andrews was at a low point in its fortunes in the early part of the century. It was restructured by commissioners appointed under the 1858 act and began a revival. It pioneered the admission of women to Scottish universities, creating the

The University of St Andrews was at a low point in its fortunes in the early part of the century. It was restructured by commissioners appointed under the 1858 act and began a revival. It pioneered the admission of women to Scottish universities, creating the Lady Literate in Arts

A Lady Literate in Arts (LLA) qualification was offered by the University of St Andrews in Scotland for more than a decade before women were allowed to graduate in the same way as men, and it became popular as a kind of external degree for women w ...

(LLA) in 1882, which proved highly popular. From 1892 Scottish universities could all admit and graduate women, with St Andrews the first to do so, and the numbers of women at Scottish universities steadily increased from this point until the early twentieth century.M. F. Rayner-Canham and G. Rayner-Canham, ''Chemistry was Their Life: Pioneering British Women Chemists, 1880–1949'' (London: Imperial College Press, 2008), , p. 264. A new college of St Andrews was opened in the thriving burgh of Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

in 1883, allowing the university to teach sciences and open a medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

.R. D. Anderson, "Universities: 2. 1720–1960", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 612–14. The University of Glasgow became a leader in British higher education by providing the educational needs of youth from the urban and commercial classes. It moved from the city centre to a new set of grand neo-Gothic buildings, paid for largely by public subscription, at Gilmorehill in 1870.T. M. Devine, ''Glasgow: 1830 to 1912'' (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996), , p. 249. The two colleges at Aberdeen were considered too small to be viable and they were restructured as the University of Aberdeen

The University of Aberdeen ( sco, University o' 'Aiberdeen; abbreviated as ''Aberd.'' in List of post-nominal letters (United Kingdom), post-nominals; gd, Oilthigh Obar Dheathain) is a public university, public research university in Aberdeen, Sc ...

in 1860. Marischal College was rebuilt in the Gothic style from 1900. Unlike the other Medieval and ecclesiastical foundations, because the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

was a civic college it was relatively poor. In 1858 it was taken out of the care of the city and established on a similar basis to the other ancient universities.

The result of these reforms was a revitalisation of the Scottish university system, which expanded to 6,254 students by the end of the century and produced leading figures in both the arts and sciences. The chair of Engineering at Glasgow became highly distinguished under its second incumbent

The result of these reforms was a revitalisation of the Scottish university system, which expanded to 6,254 students by the end of the century and produced leading figures in both the arts and sciences. The chair of Engineering at Glasgow became highly distinguished under its second incumbent William John Macquorn Rankine

William John Macquorn Rankine (; 5 July 1820 – 24 December 1872) was a Scottish mechanical engineer who also contributed to civil engineering, physics and mathematics. He was a founding contributor, with Rudolf Clausius and William Thomson ( ...

(1820–72), who held the position from 1859 to 1872 and became the leading figure in heat engine

In thermodynamics and engineering, a heat engine is a system that converts heat to mechanical energy, which can then be used to do mechanical work. It does this by bringing a working substance from a higher state temperature to a lower state ...

s and founder president of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland. Thomas Thomson Thomas Thomson may refer to:

* Tom Thomson (1877–1917), Canadian painter

* Thomas Thomson (apothecary) (died 1572), Scottish apothecary

* Thomas Thomson (advocate) (1768–1852), Scottish lawyer

* Thomas Thomson (botanist) (1817–1878), Scottis ...

(1773–1852) was the first Professor of Chemistry at Glasgow and in 1831 founded the Shuttle Street laboratories, perhaps the first of their kind in the world. His students founded practical chemistry at Aberdeen soon after. William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin was appointed to the chair of natural philosophy at Glasgow aged only 22. His work included the mathematical analysis of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics. By 1870 Kelvin and Rankine had made Glasgow the leading centre of science and engineering education and investigation in Britain.

At Edinburgh, major figures included David Brewster

Sir David Brewster KH PRSE FRS FSA Scot FSSA MICE (11 December 178110 February 1868) was a British scientist, inventor, author, and academic administrator. In science he is principally remembered for his experimental work in physical optics ...

(1781–1868), who made contributions to the science of optics and to the development of photography. Fleeming Jenkin

Henry Charles Fleeming Jenkin FRS FRSE LLD (; 25 March 1833 – 12 June 1885) was Regius Professor of Engineering at the University of Edinburgh, remarkable for his versatility. Known to the world as the inventor of the cable car or telphera ...

(1833–85) was the first professor of engineering at the university and among wide interests helped develop ocean telegraphs and mechanical drawing. In medicine Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 182710 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery and preventative medicine. Joseph Lister revolutionised the craft of s ...

(1827–1912) and his student William Macewen

Sir William Macewen, (; 22 June 1848 – 22 March 1924) was a Scottish surgeon. He was a pioneer in modern brain surgery, considered the ''father of neurosurgery'' and contributed to the development of bone graft surgery, the surgical treat ...

(1848–1924), pioneered antiseptic surgery.O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, ''Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), , p. 151. The University of Edinburgh was also a major supplier of surgeons for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, and Robert Jameson (1774–1854), Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh, ensured that a large number of these were surgeon-naturalists, who were vital in the Humboldtian and imperial enterprise of investigating nature throughout the world.J. L. Heilbron, ''The Oxford Companion To the History of Modern Science'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), , p. 386. Major figures to emerge from Scottish universities in the science of humanity included the philosopher Edward Caird

Edward Caird (; 23 March 1835 – 1 November 1908) was a Scottish philosopher. He was a holder of LLD, DCL, and DLitt.

Life

The younger brother of the theologian John Caird, he was the son of engineer John Caird, the proprietor of Caird ...

(1835–1908), the anthropologist James George Frazer

Sir James George Frazer (; 1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

Personal life

He was born on 1 Janua ...

(1854–1941) and the sociologist and urban planner Patrick Geddes (1854–1932).O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, ''Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), , p. 152-4.

Twentieth century to the present

From 1901 large numbers of students received bursaries from the

From 1901 large numbers of students received bursaries from the Carnegie Trust

The Carnegie United Kingdom Trust is an independent, endowed charitable trust based in Scotland that operates throughout Great Britain and Ireland. Originally established with an endowment from Andrew Carnegie in his birthplace of Dunfermline, ...

. By 1913 there were 7,776 students in Scottish universities. Of these 1,751 (23 per cent) were women. By the mid-1920s it had risen to a third. It then fell to 25–7 per cent in the 1930s as opportunities in school teaching, virtually the only careers outlet for female graduates in arts and sciences, decreased. No woman was appointed to a Scottish professorship until after 1945. The fall in numbers was most acute among women students, but it was part of a general trend. In the first half of the twentieth century Scottish universities fell behind those in England and Europe in terms of participation and investment. The decline of traditional industries between the wars undermined recruitment to subjects in which Scotland had been traditionally strong, such as science and engineering. English universities increased the numbers of students registered between 1924 and 1927 by 19 per cent, but in Scotland the number of full-time students fell from 10,400 in 1924 to 9,900 in 1937. In the same period, while expenditure in English universities rose by 90 per cent, in Scotland the increase was less than a third of that figure.C. Harvie, ''No Gods and Precious Few Heroes: Twentieth-Century Scotland'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 3rd edn., 1998), , pp. 78–9.

Before the First World War relationships between male and female students tended to be very formal, but in the inter-war years there was an increase in social activities, such as dance halls, cinemas, cafes and public houses. From the 1920s much drunken and high spirited activity was diverted into the annual charity gala or rag

Rag, rags, RAG or The Rag may refer to:

Common uses

* Rag, a piece of old cloth

* Rags, tattered clothes

* Rag (newspaper), a publication engaging in tabloid journalism

* Rag paper, or cotton paper

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Rags'' (1915 ...

. Male centred activities included the Student's Union, Rugby Club and Officers' Training Corps. Women had their own unions and athletics clubs. Universities remained largely non-residential, although a few women's halls of residence were created, most not owned by the universities.

After the Robbins Report

The Robbins Report (the report of the Committee on Higher Education, chaired by Lord Robbins) was commissioned by the British government and published in 1963. The committee met from 1961 to 1963. After the report's publication, its conclusions wer ...

of 1963 there was a rapid expansion in higher education in Scotland. By the end of the decade the number of Scottish Universities had doubled. The University of Dundee was demerged from St. Andrews, Strathclyde and Heriot-Watt

Heriot-Watt University ( gd, Oilthigh Heriot-Watt) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was established in 1821 as the School of Arts of Edinburgh, the world's first mechanics' institute, and subsequently granted univ ...

developing from technical colleges and the Stirling was begun as a completely new university on a greenfield

Greenfield or Greenfields may refer to:

Engineering and Business

* Greenfield agreement, an employment agreement for a new organisation

* Greenfield investment, the investment in a structure in an area where no previous facilities exist

* Greenf ...

site in 1966. From the 1970s the government preferred to expand higher education in the non-university sector of educational and technical colleges, which were cheaper because they undertook little research. By the late 1980s roughly half of students in higher education were in colleges. In 1992, under the Further and Higher Education Act 1992

The Further and Higher Education Act 1992 made changes in the funding and administration of further education and higher education within England and Wales, with consequential effects on associated matters in Scotland which had previously been ...

, the distinction between universities and colleges was removed.L. Paterson, "Universities: 3. post-Robbins", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 614–5. This created new universities at Abertay, Glasgow Caledonian, Napier Napier may refer to:

People

* Napier (surname), including a list of people with that name

* Napier baronets, five baronetcies and lists of the title holders

Given name

* Napier Shaw (1854–1945), British meteorologist

* Napier Waller (1893–19 ...

, Paisley and Robert Gordon Robert Gordon may refer to:

Entertainment

* Robert Gordon (actor) (1895–1971), silent-film actor

* Robert Gordon (director) (1913–1990), American director

* Robert Gordon (singer) (1947–2022), American rockabilly singer

* Robert Gordon (scr ...

. Despite the expansion the number of male students experienced a downturn in growth from 1971 to 1990. The growth in female student numbers was much larger and continued until, by 1999 and 2000, the numbers of women students exceeded male students for the first time.

After devolution, in 1999 the new Scottish Executive set up an Education Department and an Enterprise, Transport and Lifelong Learning Department, which together took over its functions.J. Fairley, "The Enterprise and Lifelong Learning Department and the Scottish Parliament", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, ''Scottish Education: Post-Devolution'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), , pp. 132–40. One of the major diversions from practice in England, possible because of devolution, was the abolition of student tuition fees in 1999, instead retaining a system of means-tested student grants.D. Cauldwell, "Scottish Higher Education: Character and Provision", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, ''Scottish Education: Post-Devolution'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), , pp. 62–73. In 2001 the University of the Highlands and Islands was created by a federation of 13 colleges and research institutions in the Highlands and Islands in 2001 and which gained full university status in 2011.

In 2008–09, approximately 231,000 students studied at universities or institutes of higher education in Scotland, of which 56 per cent were female and 44 per cent male.Scottish GovernmentStatistics Publication Notice Lifelong Learning Series: Students In Higher Education At Scottish Institutions

' (2001). Retrieved 25 May 2011.

Notes

{{Universities in Scotland, state=expanded History of education in ScotlandScotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...