The

Cyclades

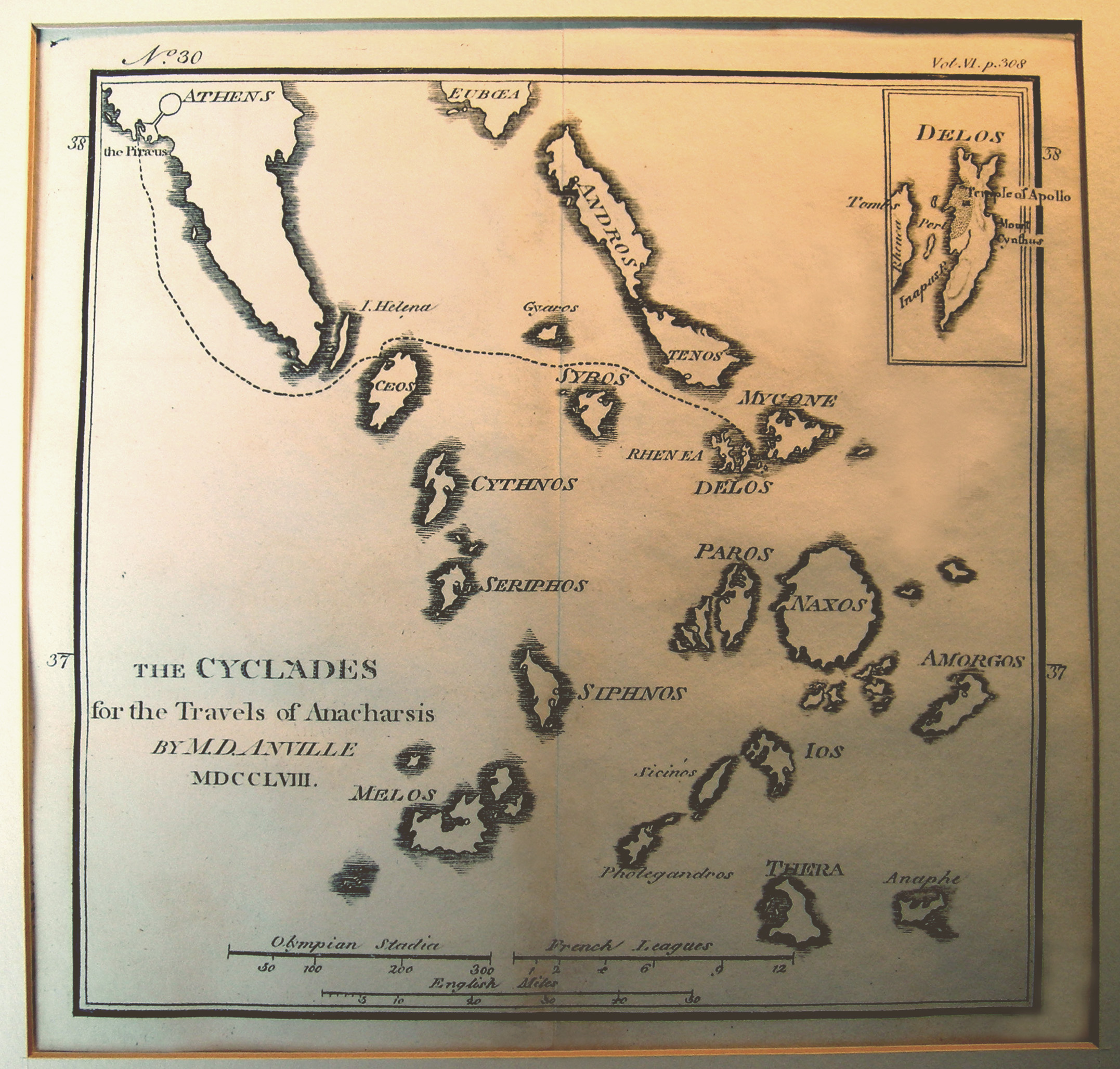

The Cyclades (; el, Κυκλάδες, ) are an island group in the Aegean Sea, southeast of mainland Greece and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The nam ...

(

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: Κυκλάδες ''Kykládes'') are

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

islands located in the southern part of the

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

. The

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

contains some 2,200 islands, islets and rocks; just 33 islands are inhabited. For the ancients, they formed a circle (κύκλος / kyklos in

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

) around the sacred island of

Delos

The island of Delos (; el, Δήλος ; Attic: , Doric: ), near Mykonos, near the centre of the Cyclades archipelago, is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. The excavations in the island are ...

, hence the name of the archipelago. The best-known are, from north to south and from east to west:

Andros

Andros ( el, Άνδρος, ) is the northernmost island of the Greek Cyclades archipelago, about southeast of Euboea, and about north of Tinos. It is nearly long, and its greatest breadth is . It is for the most part mountainous, with many fr ...

,

Tinos

Tinos ( el, Τήνος ) is a Greek island situated in the Aegean Sea. It is located in the Cyclades archipelago. The closest islands are Andros, Delos, and Mykonos. It has a land area of and a 2011 census population of 8,636 inhabitants.

Tinos ...

,

Mykonos

Mykonos (, ; el, Μύκονος ) is a Greek island, part of the Cyclades, lying between Tinos, Syros, Paros and Naxos. The island has an area of and rises to an elevation of at its highest point. There are 10,134 inhabitants according to the ...

,

Naxos

Naxos (; el, Νάξος, ) is a Greek island and the largest of the Cyclades. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture. The island is famous as a source of emery, a rock rich in corundum, which until modern times was one of the best abr ...

,

Amorgos

Amorgos ( el, Αμοργός, ; ) is the easternmost island of the Cyclades island group and the nearest island to the neighboring Dodecanese island group in Greece. Along with 16 neighboring islets, the largest of which (by land area) is Niko ...

,

Syros

Syros ( el, Σύρος ), also known as Siros or Syra, is a Greek island in the Cyclades, in the Aegean Sea. It is south-east of Athens. The area of the island is and it has 21,507 inhabitants (2011 census).

The largest towns are Ermoupoli, A ...

,

Paros

Paros (; el, Πάρος; Venetian: ''Paro'') is a Greek island in the central Aegean Sea. One of the Cyclades island group, it lies to the west of Naxos, from which it is separated by a channel about wide. It lies approximately south-east of ...

and

Antiparos

Antiparos ( ell, Αντίπαρος; grc, Ὠλίαρος, Oliaros; la, Oliarus; is a small island in the southern Aegean, at the heart of the Cyclades, which is less than one nautical mile (1.9 km) from Paros, the port to which it is conne ...

,

Ios

iOS (formerly iPhone OS) is a mobile operating system created and developed by Apple Inc. exclusively for its hardware. It is the operating system that powers many of the company's mobile devices, including the iPhone; the term also includes ...

,

Santorini

Santorini ( el, Σαντορίνη, ), officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα ) and classical Greek Thera (English pronunciation ), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast from the Greek mainland. It is the ...

,

Anafi

Anafi or Anaphe ( el, Ανάφη; grc, Ἀνάφη) is a Greek island community in the Cyclades. In 2011, it had a population of 271. Its land area is . It lies east of the island of Thíra (Santorini). Anafi is part of the Thira regional unit. ...

,

Kea

The kea (; ; ''Nestor notabilis'') is a species of large parrot in the family Nestoridae found in the forested and alpine regions of the South Island of New Zealand. About long, it is mostly olive-green with a brilliant orange under its wing ...

,

Kythnos,

Serifos

Serifos ( el, Σέριφος, la, Seriphus, also Seriphos; Seriphos: Eth. Seriphios: Serpho) is a Greek island municipality in the Aegean Sea, located in the western Cyclades, south of Kythnos and northwest of Sifnos. It is part of the Milos reg ...

,

Sifnos

Sifnos ( el, Σίφνος) is an island municipality in the Cyclades island group in Greece. The main town, near the center, known as Apollonia (pop. 869), is home of the island's folklore museum and library. The town's name is thought to come f ...

,

Folegandros

Folegandros (also Pholegandros; el, Φολέγανδρος) is a small Greek island in the Aegean Sea that, together with Sikinos, Ios, Anafi and Santorini, forms the southern part of the Cyclades. Its surface area is and it has 765 inhabitant ...

and

Sikinos

Sikinos ( el, Σίκινος) is a Greek island and municipality in the Cyclades. It is located midway between the islands of Ios and Folegandros. Sikinos is part of the Thira regional unit.

It was known as Oenoe or Oinoe ( grc, Οἰνόη, ...

,

Milos

Milos or Melos (; el, label=Modern Greek, Μήλος, Mílos, ; grc, Μῆλος, Mêlos) is a volcanic Greek island in the Aegean Sea, just north of the Sea of Crete. Milos is the southwesternmost island in the Cyclades group.

The ''Venus d ...

and

Kimolos

Kimolos ( el, Κίμωλος; la, Cimolus) is a Greek island in the Aegean Sea. It lies on the southwest of the island group of Cyclades, near the bigger island of Milos. Kimolos is the administrative center of the municipality of Kimolos, which ...

; to these can be added the little Cyclades:

Irakleia,

Schoinoussa

Schoinoussa or Schinoussa ( el, Σχοινούσσα, before 1940: Σχοινούσα, ; anciently, grc, Σχινοῦσσα) is an island and a former community in the Cyclades, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the mun ...

,

Koufonisi

Koufonisia ( el, Κουφονήσια) is a former community in the Cyclades, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Naxos and Lesser Cyclades, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an area ...

,

Keros

Keros ( el, Κέρος; anciently, Keria or Kereia ( grc, Κέρεια) is an uninhabited and unpopulated Greece, Greek island in the Cyclades about southeast of Naxos Island, Naxos. Administratively it is part of the Communities and Municipali ...

and

Donoussa

Donousa ( el, Δονούσα, also Δενούσα ''Denousa''), and sometimes spelled Donoussa, is an island and a former community in the Cyclades, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Naxos and Lesser Cyc ...

, as well as

Makronisos

Makronisos ( el, Μακρόνησος, lit. ''Long Island''), or Makronisi, is an island in the Aegean sea, in Greece, notorious as the site of a political prison from the 1920s to the 1970s. It is located close to the coast of Attica, facing the ...

between Kea and

Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean Se ...

,

Gyaros

Gyaros ( el, Γυάρος ), also locally known as Gioura ( el, Γιούρα), is an arid, unpopulated, and uninhabited Greek island in the northern Cyclades near the islands of Andros and Tinos, with an area of . It is a part of the municipality ...

, which lies before Andros, and

Polyaigos

Polýaigos ( el, Πολύαιγος; la, Polyaegus) is an uninhabited Greek island in the Cyclades near Milos and Kimolos. It is part of the community of Kimolos (Κοινότητα Κιμώλου). Its name means "many goats", since it is inha ...

to the east of Kimolos and Thirassia, before Santorini. At times they were also called by the generic name of Archipelago.

The islands are located at the crossroads between

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and the

Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

as well as between Europe and

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. In antiquity, when navigation consisted only of

cabotage

Cabotage () is the transport of goods or passengers between two places in the same country. It originally applied to shipping along coastal routes, port to port, but now applies to aviation, railways, and road transport as well.

Cabotage rights ar ...

and sailors sought never to lose sight of land, they played an essential role as a stopover. Into the 20th century, this situation made their fortune (trade was one of their chief activities) and their misfortune (control of the Cyclades allowed for control of the commercial and strategic routes in the Aegean).

Numerous authors considered, or still consider them as a sole entity, a unit. The insular group is indeed rather homogeneous from a

geomorphological

Geomorphology (from Ancient Greek: , ', "earth"; , ', "form"; and , ', "study") is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features created by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or n ...

point of view; moreover, the islands are visible from each other's shores while being distinctly separate from the continents that surround them. The dryness of the climate and of the soil also suggests unity. Although these physical facts are undeniable, other components of this unity are more subjective. Thus, one can read certain authors who say that the islands’ population is, of all the regions of Greece, the only original one, and has not been subjected to external admixtures. However, the Cyclades have very often known different destinies.

Their natural resources and their potential role as trade-route stopovers has allowed them to be peopled since the

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

. Thanks to these assets, they experienced a brilliant cultural flowering in the 3rd millennium BC: the

Cycladic civilisation

Cycladic culture (also known as Cycladic civilisation or, chronologically, as Cycladic chronology) was a Bronze Age culture (c. 3200–c. 1050 BC) found throughout the islands of the Cyclades in the Aegean Sea. In chronological terms, it is a rel ...

. The proto-historical powers, the Minoans and then the Mycenaeans, made their influence known there. The Cyclades had a new zenith in the

Archaic period (8th – 6th century BC). The Persians tried to take them during their attempts to conquer Greece. Then they entered into Athens' orbit with the

Delian League

The Delian League, founded in 478 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Pl ...

s. The Hellenistic kingdoms disputed their status while Delos became a great commercial power.

Commercial activities were pursued during the Roman and Byzantine Empires, yet they were sufficiently prosperous as to attract pirates' attention. The participants of the

Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

divided the Byzantine Empire among themselves and the Cyclades entered the Venetian orbit. Western feudal lords created a certain number of fiefs, of which the Duchy of Naxos was the most important. The Duchy was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, which allowed the islands a certain administrative and fiscal autonomy. Economic prosperity continued despite the pirates. The archipelago had an ambiguous attitude towards the war of independence. Having become Greek in the 1830s, the Cyclades have shared the history of Greece since that time. At first they went through a period of commercial prosperity, still due to their geographic position, before the trade routes and modes of transport changed. After suffering a rural exodus, renewal began with the influx of tourists. However, tourism is not the Cyclades' only resource today.

Prehistory

Neolithic era

The most ancient traces of activity (but not necessarily habitation) in the Cyclades were not discovered on the islands themselves, but on the continent, at

Argolis

Argolis or Argolida ( el, Αργολίδα , ; , in ancient Greek and Katharevousa) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Peloponnese, situated in the eastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula and part of the tri ...

, in

Franchthi Cave

Franchthi Cave or Frankhthi Cave ( el, Σπήλαιον Φράγχθι) is an archaeological site overlooking Kiladha Bay, in the Argolic Gulf, opposite the village of Kiladha in southeastern Argolis, Greece.

Humans first occupied the cave during ...

. Research there uncovered, in a layer dating to the 11th millennium BC,

obsidian

Obsidian () is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.

Obsidian is produced from felsic lava, rich in the lighter elements s ...

originating from

Milos

Milos or Melos (; el, label=Modern Greek, Μήλος, Mílos, ; grc, Μῆλος, Mêlos) is a volcanic Greek island in the Aegean Sea, just north of the Sea of Crete. Milos is the southwesternmost island in the Cyclades group.

The ''Venus d ...

.

[Fitton, ''Cycladic Art.'', p. 22-23.] The volcanic island was thus exploited and inhabited, not necessarily in permanent fashion, and its inhabitants were capable of navigating and trading across a distance of at least 150 km.

A permanent settlement on the islands could only be established by a sedentary population that had at its disposal methods of agriculture and animal husbandry that could exploit the few fertile plains. Hunter-gatherers would have had much greater difficulties.

At the Maroula site on Kythnos a bone fragment has been uncovered and dated, using

Carbon-14

Carbon-14, C-14, or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with an atomic nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic materials is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and coll ...

, to 7,500-6,500 BC. The oldest inhabited places are the islet of Saliango between Paros and Antiparos,

[''Guide Bleu. Îles grecques.'', p. 202.] Kephala on Kea, and perhaps the oldest strata are those at Grotta on Naxos.

They date back to the 5th millennium BC.

On Saliango (at that time connected to its two neighbours, Paros and Antiparos), houses of stone without mortar have been found, as well as Cycladic statuettes. Estimates based on excavations in the cemetery of Kephala put the number of inhabitants at between forty-five and eighty.

Studies of skulls have revealed bone deformations, especially in the vertebrae. They have been attributed to arthritic conditions, which afflict sedentary societies.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass, micro-architectural deterioration of bone tissue leading to bone fragility, and consequent increase in fracture risk. It is the most common reason for a broken bone ...

, another sign of a sedentary lifestyle, is present, but more rarely than on the continent in the same period. Life expectancy has been estimated at twenty years, with maximum ages reaching twenty-eight to thirty. Women tended to live less than men.

[''Les Civilisations égéennes.'', p. 142.]

A sexual division of labour seems to have existed. Women took care of children, harvesting, “light” agricultural duties, “small” livestock, spinning (spindle whorls have been found in women's tombs), basketry and pottery.

Men busied themselves with “masculine” chores: more serious agricultural work, hunting, fishing, and work involving stone, bone, wood and metal.

This sexual division of labour led to a first social differentiation: the richest tombs of those found in

cist

A cist ( or ; also kist ;

from grc-gre, κίστη, Middle Welsh ''Kist'' or Germanic ''Kiste'') is a small stone-built coffin-like box or ossuary used to hold the bodies of the dead. Examples can be found across Europe and in the Middle East ...

s are those belonging to men.

Pottery was made without a lathe, judging by the hand-modelled clay balls; pictures were applied to the pottery using brushes, while incisions were made with the fingernails. The vases were then baked in a pit or a grinding wheel—kilns were not used and only low temperatures of 700˚-800˚C were reached. Small-sized metal objects have been found on Naxos. The operation of silver mines on Siphnos may also date to this period.

Cycladic civilisation

At the end of the 19th century, the Greek archaeologist

Christos Tsountas Christos Tsountas ( el, Χρήστος Τσούντας; 1857 – 9 June 1934) was a Greece, Greek classical archaeologist. He was born in Thrace, Thracian Stenimachos, Ottoman Empire (present-day Asenovgrad in Bulgaria) and attended Zariphios Schoo ...

, having assembled various discoveries from numerous islands, suggested that the Cyclades were part of a cultural unit during the 3rd millennium BC: the Cycladic civilisation,

dating back to the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

. It is famous for its marble idols, found as far as

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

and the mouth of the

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

,

which proves its dynamism.

It is slightly older than the

Minoan civilisation

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450B ...

of

Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

. The beginnings of the Minoan civilisation were influenced by the Cycladic civilisation: Cycladic statuettes were imported into Crete and local artisans imitated Cycladic techniques; archaeological evidence supporting this notion has been found at

Aghia Photia,

Knossos

Knossos (also Cnossos, both pronounced ; grc, Κνωσός, Knōsós, ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the na ...

and Archanes. At the same time, excavations in the cemetery of Aghios Kosmas in

Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean Se ...

have uncovered objects proving a strong Cycladic influence, due either to a high percentage of the population being Cycladic or to an actual colony originating in the islands.

Three great periods have traditionally been designated (equivalent to those that divide the Helladic on the continent and the Minoan in Crete):

[''Guide Bleu. Îles grecques.'', p. 203.]

* Early Cycladic I (EC I; 3200-2800 BC), also called the

Grotta-Pelos culture

The Grotta-Pelos culture ( el, Γρόττα-Πηλός) refers to a "cultural" dating system used for part of the early Bronze Age in Greece.Eric H. Cline (ed.), ''The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean'', , Jan. 2012. Specifically, it is ...

* Early Cycladic II (EC II; 2800-2300 BC), also called the

Keros-Syros culture

The Keros-Syros culture is named after two islands in the Cyclades: Keros and Syros. This culture flourished during the Early Cycladic II period (ca 2700-2300 BC) of the Cycladic civilization. The trade relations of this culture spread far and ...

and often considered the apogee of Cycladic civilisation

* Early Cycladic III (EC III; 2300-2000 BC), also called the

Phylakopi culture

The study of skeletons found in tombs, always in cists, shows an evolution from the Neolithic. Osteoporosis was less prevalent although arthritic diseases continued to be present. Thus, diet had improved. Life expectancy progressed: men lived up to forty or forty-five years, but women only thirty.

[''Les Civilisations égéennes.'', p. 181.] The sexual division of labour remained the same as that identified for the Early Neolithic: women busied themselves with small domestic and agricultural tasks, while men took care of larger duties and crafts.

Agriculture, as elsewhere in the Mediterranean basin, was based on grain (mainly barley, which needs less water than wheat), grapevines and olive trees. Animal husbandry was already primarily concerned with goats and sheep, as well as a few hogs, but very few bovines, the raising of which is still poorly developed on the islands. Fishing completed the diet base, due for example to the regular migration of

tuna

A tuna is a saltwater fish that belongs to the tribe Thunnini, a subgrouping of the Scombridae (mackerel) family. The Thunnini comprise 15 species across five genera, the sizes of which vary greatly, ranging from the bullet tuna (max length: ...

.

[Fitton, ''Cycladic Art.'', p. 13-14.] At the time, wood was more abundant than today, allowing for the construction of house frames and boats.

The inhabitants of these islands, who lived mainly near the shore, were remarkable sailors and merchants, thanks to their islands’ geographic position. It seems that at the time, the Cyclades exported more merchandise than they imported, a rather unusual circumstance during their history. The ceramics found at various Cycladic sites (

Phylakopi

Phylakopi ( el, Φυλακωπή), located at the northern coast of the island of Milos, is one of the most important Bronze Age settlements in the Aegean and especially in the Cyclades. The importance of Phylakopi is in its continuity throughout ...

on Milos, Aghia Irini on Kea and

Akrotiri on Santorini) prove the existence of commercial routes going from continental Greece to Crete while mainly passing by the Western Cyclades, up until the Late Cycladic. Excavations at these three sites have uncovered vases produced on the continent or on Crete and imported onto the islands.

It is known that there were specialised artisans: founders, blacksmiths, potters and sculptors, but it is impossible to say if they made a living off their work.

Obsidian from Milos remained the dominant material for the production of tools, even after the development of metallurgy, for it was less expensive. Tools have been found that were made of a primitive bronze, an alloy of copper and arsenic. The copper came from Kythnos and already contained a high volume of arsenic. Tin, the provenance of which has not been determined, was only later introduced into the islands, after the end of the Cycladic civilisation. The oldest bronze containing tin was found at Kastri on Tinos (dating to the time of the Phylakopi Culture) and their composition proves they came from

Troad

The Troad ( or ; el, Τρωάδα, ''Troáda'') or Troas (; grc, Τρῳάς, ''Trōiás'' or , ''Trōïás'') is a historical region in northwestern Anatolia. It corresponds with the Biga Peninsula ( Turkish: ''Biga Yarımadası'') in the Ç ...

, either as raw materials or as finished products.

[Fitton, ''Cycladic Art'', p. 14-17.] Therefore, commercial exchanges between the Troad and the Cyclades existed.

These tools were used to work marble, above all coming from Naxos and Paros, either for the celebrated Cycladic idols, or for marble vases. It appears that marble was not then, like today, extracted from mines, but was quarried in great quantities.

The emery of Naxos also furnished material for polishing. Finally, the pumice stone of Santorini allowed for a perfect finish.

The pigments that can be found on statuettes, as well as in tombs, also originated on the islands, as well as the azurite for blue and the iron ore for red.

Eventually, the inhabitants left the seashore and moved toward the islands’ summits within fortified enclosures rounded out by round towers at the corners. It was at this time that piracy might first have made an appearance in the archipelago.

Minoans and Mycenaeans

The Cretans occupied the Cyclades during the 2nd millennium BC, then the

Mycenaeans from 1450 BC and the Dorians from 1100 BC. The islands, due to their relatively small size, could not fight against these highly centralised powers.

[Fitton, ''Cycladic Art.'', p. 19]

Literary sources

Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of "scientifi ...

writes that

Minos

In Greek mythology, Minos (; grc-gre, Μίνως, ) was a King of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. Every nine years, he made King Aegeus pick seven young boys and seven young girls to be sent to Daedalus's creation, the labyrinth, to be eaten ...

expelled the archipelago's first inhabitants, the

Carians

The Carians (; grc, Κᾶρες, ''Kares'', plural of , ''Kar'') were the ancient inhabitants of Caria in southwest Anatolia.

Historical accounts Karkisa

It is not clear when the Carians enter into history. The definition is dependent on c ...

, whose tombs were numerous on Delos.

Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

specifies that the Carians were subjects of king

Minos

In Greek mythology, Minos (; grc-gre, Μίνως, ) was a King of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. Every nine years, he made King Aegeus pick seven young boys and seven young girls to be sent to Daedalus's creation, the labyrinth, to be eaten ...

and went by the name

Leleges

The Leleges (; grc-gre, Λέλεγες) were an aboriginal people of the Aegean region, before the Greeks arrived. They were distinct from another pre-Hellenic people of the region, the Pelasgians. The exact areas to which they were native are un ...

at that time. They were completely independent (“they paid no tribute”), but supplied sailors for Minos’ ships.

According to Herodotus, the Carians were the best warriors of their time and taught the Greeks to place plumes on their helmets, to represent insignia on their shields and to use straps to hold these.

Later, the Dorians would expel the Carians from the Cyclades; the former were followed by the Ionians, who turned the island of Delos into a great religious centre.

Cretan influence

Fifteen settlements from the Middle Cycladic (c. 2000-1600 BC) are known. The three best studied are Aghia Irini (IV and V) on Kea, Paroikia on Paros and Phylakopi (II) on Milos. The absence of a real break (despite a stratum of ruins) between Phylakopi I and Phylakopi II suggests that the transition between the two was not a brutal one.

[''Les Civilisations égéennes'', p. 262-265.] The principal proof of an evolution from one stage to the next is the disappearance of Cycladic idols from the tombs,

which by contrast changed very little, having remained in cists since the Neolithic.

The Cyclades also underwent a cultural differentiation. One group in the north around Kea and Syros tended to approach the Northeast Aegean from a cultural point of view, while the Southern Cyclades seem to have been closer to the Cretan civilisation.

Ancient tradition speaks of a Minoan maritime empire, a sweeping image that demands some nuance, but it is nevertheless undeniable that Crete ended up having influence over the entire Aegean. This began to be felt more strongly beginning with the Late Cycladic, or the Late Minoan (from 1700/1600 BC), especially with regard to influence by

Knossos

Knossos (also Cnossos, both pronounced ; grc, Κνωσός, Knōsós, ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the na ...

and

Cydonia

Cydonia may refer to:

Music

* ''Cydonia'' (album), a 2001 album by The Orb

* "Cydonia", a track by heavy metal band Crimson Glory from '' Astronomica''

Places and jurisdictions

* Kydonia or Cydonia, an ancient city state on Crete, at modern ...

.

[''Les Civilisations égéennes'', p. 319-323.]

During the Late Minoan, important contacts are attested at Kea, Milos and Santorini; Minoan pottery and architectural elements (polythyra, skylights, frescoes) as well as signs of

Linear A

Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 to 1450 BC to write the hypothesized Minoan language or languages. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civil ...

have been found.

The shards found on the other Cyclades appear to have arrived there indirectly from these three islands.

It is difficult to determine the nature of the Minoan presence on the Cyclades: settler colonies, protectorate or trading post.

For a time it was proposed that the great buildings at

Akrotiri on Santorini (the West House) or at Phylakopi might be the palaces of foreign governors, but no formal proof exists that could back up this hypothesis. Likewise, too few archaeological proofs exist of an exclusively Cretan district, as would be typical for a settler colony. It seems that Crete defended her interests in the region through agents who could play a more or less important political role. In this way the Minoan civilisation protected its commercial routes.

This would also explain why the Cretan influence was stronger on the three islands of Kea, Milos and Santorini. The Cyclades were a very active trading zone. The western axis of these three was of paramount importance. Kea was the first stop off the continent, being closest, near the mines of

Laurium

Laurium or Lavrio ( ell, Λαύριο; grc, Λαύρειον (later ); before early 11th century BC: Θορικός ''Thorikos''; from Middle Ages until 1908: Εργαστήρια ''Ergastiria'') is a town in southeastern part of Attica, Greec ...

; Milos redistributed to the rest of the archipelago and remained the principal source of obsidian; and Santorini played for Crete the same role Kea did for Attica.

The great majority of bronze continued to be made with arsenic; tin progressed very slowly in the Cyclades, beginning in the northeast of the archipelago.

Settlements were small villages of sailors and farmers,

often tightly fortified.

[''Les Civilisations égéennes'', p. 270.] The houses, rectangular, of one to three rooms, were attached, of modest size and build, sometimes with an upper floor, more or less regularly organised into blocks separated by paved lanes.

There were no palaces such as were found in Crete or on the mainland.

“Royal tombs” have also not been found on the islands. Although they more or less kept their political and commercial independence, it seems that from a religious perspective, the Cretan influence was very strong. Objects of worship (zoomorphic

rhyta, libation tables, etc.), religious aids such as polished baths, and themes found on frescoes are similar at Santorini or Phylakopi and in the Cretan palaces.

The explosion at Santorini (between the Late Minoan IA and the Late Minoan IB) buried and preserved an example of a habitat: Akrotiri.

Excavations since 1967 have uncovered a built-up area covering one hectare, not counting the defensive wall.

[''Les Civilisations égéennes'', p. 331.] The layout ran in a straight line, with a more or less orthogonal network of paved streets fitted with drains. The buildings had two to three floors and lacked skylights and courtyards; openings onto the street provided air and light. The ground floor contained the staircase and rooms serving as stores or workshops; the rooms on the next floor, slightly larger, had a central pillar and were decorated with frescoes. The houses had terraced roofs placed on beams that had not been squared, covered up with a vegetable layer (seaweed or leaves) and then several layers of clay soil,

a practice that continues in traditional societies to this day.

From the beginning of excavations in 1967, the Greek archaeologist Spiridon Marinatos noted that the city had undergone a first destruction, due to an earthquake, before the eruption, as some of the buried objects were ruins, whereas a volcano alone may have left them intact.

[''Les Civilisations égéennes'', p. 362-377.] At almost the same time, the site of Aghia Irini on Kea was also destroyed by an earthquake.

One thing is certain: after the eruption, Minoan imports stopped coming into Aghia Irini (VIII), to be replaced by Mycenaean imports.

Late Cycladic: Mycenaean domination

Between the middle of the 15th century BC and the middle of the 11th century BC, relations between the Cyclades and the continent went through three phases.

[''Les Civilisations égéennes'', p. 439-440.] Right around 1250 BC (Late Helladic III A-B1 or beginning of

Late Cycladic III), Mycenaean influence was felt only on Delos,

[''Délos'', p.14.] at Aghia Irini (on

Kea

The kea (; ; ''Nestor notabilis'') is a species of large parrot in the family Nestoridae found in the forested and alpine regions of the South Island of New Zealand. About long, it is mostly olive-green with a brilliant orange under its wing ...

), at

Phylakopi

Phylakopi ( el, Φυλακωπή), located at the northern coast of the island of Milos, is one of the most important Bronze Age settlements in the Aegean and especially in the Cyclades. The importance of Phylakopi is in its continuity throughout ...

(on

Milos

Milos or Melos (; el, label=Modern Greek, Μήλος, Mílos, ; grc, Μῆλος, Mêlos) is a volcanic Greek island in the Aegean Sea, just north of the Sea of Crete. Milos is the southwesternmost island in the Cyclades group.

The ''Venus d ...

) and perhaps at

Grotta (on

Naxos

Naxos (; el, Νάξος, ) is a Greek island and the largest of the Cyclades. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture. The island is famous as a source of emery, a rock rich in corundum, which until modern times was one of the best abr ...

). Certain buildings call to mind the continental palaces, without definite proof, but typically Mycenaean elements have been found in religious sanctuaries.

During the time of troubles accompanied by destruction that the continental kingdoms experienced (Late Helladic III B), relations cooled, going so far as to stop (as indicated by the disappearance of Mycenaean objects from the corresponding strata on the islands). Moreover, some island sites built fortifications or improved their defenses (such as Phylakopi, but also

Aghios Andreas

''Agios'' ( el, Άγιος), plural ''Agioi'' (), transcribes masculine gender Greek words meaning 'sacred' or 'saint' (for example Agios Dimitrios, Agioi Anargyroi). It is frequently shortened in colloquial language to ''Ai'' (for example Agios E ...

on

Siphnos

Sifnos ( el, Σίφνος) is an island municipality in the Cyclades island group in Greece. The main town, near the center, known as Apollonia (pop. 869), is home of the island's folklore museum and library. The town's name is thought to come f ...

and

Koukounaries

Koukounaries ( el, Κουκουναριές, l "stone pines") is a location and a beach in the southwest part of the Skiathos island in Greece. It is 16 km southwest of the main town on the island. Skiathos is part of the Sporades group of is ...

on

Paros

Paros (; el, Πάρος; Venetian: ''Paro'') is a Greek island in the central Aegean Sea. One of the Cyclades island group, it lies to the west of Naxos, from which it is separated by a channel about wide. It lies approximately south-east of ...

).

Relations were resumed during

Late Helladic III C. To the importation of objects (jars with handles decorated with squids) was also added the movement of peoples with migrations coming from the continent.

A

beehive tomb

A beehive tomb, also known as a tholos tomb (plural tholoi; from Greek θολωτός τάφος, θολωτοί τάφοι, "domed tombs"), is a burial structure characterized by its false dome created by corbelling, the superposition of suc ...

, characteristic of continental Mycenaean tombs, has been found on Mykonos.

The Cyclades were continuously occupied until the Mycenaean civilisation began to decline.

Geometric, Archaic and Classical Eras

Ionian arrival

The Ionians came from the continent around the 10th century BC, setting up the great religious sanctuary of Delos around three centuries later. The ''

Homeric Hymn

The ''Homeric Hymns'' () are a collection of thirty-three anonymous ancient Greek hymns celebrating individual gods. The hymns are "Homeric" in the sense that they employ the same epic meter—dactylic hexameter—as the ''Iliad'' and ''Odyssey'', ...

to

Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

'' (the first part of which may date to the 7th century BC) alludes to Ionian

panegyric

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of grc, ...

s (which included athletic competitions, songs and dances).

[Claude Baurain, ''Les Grecs et la Méditerranée orientale'', p. 212.] Archaeological excavations have shown that a religious centre was built on the ruins of a settlement dating to the Middle Cycladic.

It was between the 12th and the 8th centuries BC that the first Cycladic cities were built, including four on Kea (Ioulis, Korissia, Piessa and Karthaia) and Zagora on Andros, the houses of which were surrounded by a wall dated by archaeologists to 850 BC. Ceramics indicate the diversity of local production,

[''Guide Bleu. Îles grecques.'', p. 204.] and thus the differences between the islands. Hence, it seems that Naxos, the islet of Donoussa and above all Andros had links with

Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

, while Milos and Santorini were in the Doric sphere of influence.

Zagora, one of the most important urban settlements of the era which it has been possible to study, reveals that the type of traditional buildings found there evolved little between the 9th century BC and the 19th century. The houses had flat roofs made of

schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes o ...

slabs covered up with clay and truncated corners designed to allow beasts of burden to pass by more easily.

A new apogee

From the 8th century BC, the Cyclades experienced an apogee linked in great part to their natural riches (obsidian from Milos and Sifnos, silver from Syros, pumice stone from Santorini and marble, chiefly from Paros).

This prosperity can also be seen from the relatively weak participation of the islands in the movement of

Greek colonisation

Greek colonization was an organised colonial expansion by the Archaic Greeks into the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea in the period of the 8th–6th centuries BC.

This colonization differed from the migrations of the Greek Dark Ages in that it ...

, other than Santorini's establishment of

Cyrene. Cycladic cities celebrated their prosperity through great sanctuaries: the treasury of Sifnos, the Naxian column at Delphi or the terrace of lions offered by Naxos to Delos.

Classical Era

The wealth of the Cycladic cities thus attracted the interest of their neighbours. Shortly after the treasury of Sifnos at Delphi was built, forces from

Samos

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate ...

pillaged the island in 524 BC.

[''Guide Bleu. Îles grecques.'', p.205.] At the end of the 6th century BC,

Lygdamis, tyrant of Naxos, ruled some of the other islands for a time.

The Persians tried to take the Cyclades near the beginning of the 5th century BC.

Aristagoras

Aristagoras ( grc-gre, Ἀρισταγόρας ὁ Μιλήσιος), d. 497/496 BC, was the leader of the Ionian city of Miletus in the late 6th century BC and early 5th century BC and a key player during the early years of the Ionian Revolt a ...

, nephew of Histiaeus, tyrant of

Miletus

Miletus (; gr, Μῑ́λητος, Mī́lētos; Hittite transcription ''Millawanda'' or ''Milawata'' (exonyms); la, Mīlētus; tr, Milet) was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in a ...

, launched an expedition with Artaphernes, satrap of

Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

, against Naxos. He hoped to control the entire archipelago after taking this island. On the way there, Aristagoras quarreled with the admiral Megabetes, who betrayed the force by informing Naxos of the fleet's approach. The Persians temporarily renounced their ambitions in the Cyclades due to the Ionian revolt.

[Louis Lacroix, p.433.]

Median Wars

When

Darius launched his

expedition against Greece, he ordered

Datis

Datis or Datus ( el, Δάτης, Old Iranian: *Dātiya-, Achaemenid Elamite: Da-ti-ya), was a Median noble and admiral who served the Persian Empire during the reign of Darius the Great. He was familiar with Greek affairs and maintained connect ...

and

Artaphernes

Artaphernes ( el, Ἀρταφέρνης, Old Persian: Artafarna, from Median ''Rtafarnah''), flourished circa 513–492 BC, was a brother of the Achaemenid king of Persia, Darius I, satrap of Lydia from the capital of Sardis, and a Persian gener ...

to take the Cyclades.

They sacked Naxos,

Delos was spared for religious reasons while Sifnos, Serifos and Milos preferred to submit and give up hostages.

Thus the islands passed under Persian control. After

Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of , usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There are also wheelchair div ...

,

Miltiades

Miltiades (; grc-gre, Μιλτιάδης; c. 550 – 489 BC), also known as Miltiades the Younger, was a Greek Athenian citizen known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon, as well as for his downfall afterwards. He was the son of Cimon C ...

set out to reconquer the archipelago, but he failed before Paros.

The islanders provided the Persian fleet with sixty-seven ships, but on the eve of the

Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

, six or seven Cycladic ships (from Naxos, Kea, Kythnos, Serifos, Sifnos and Milos) would pass from the Greek side.

Thus the islands won the right to appear on the tripod consecrated at Delphi.

Themistocles

Themistocles (; grc-gre, Θεμιστοκλῆς; c. 524–459 BC) was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. A ...

, pursuing the Persian fleet across the archipelago, also sought to punish the islands most compromised with regard to the Persians, a prelude to Athenian domination.

In 479 BC, certain Cycladic cities (on Kea, Milos, Tinos, Naxos and Kythnos) were present beside other Greeks at the

Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states (including Sparta, Athens, C ...

, as attested by the pedestal of the statue consecrated to Zeus the Olympian, described by

Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

.

Delian Leagues

When the

Median

In statistics and probability theory, the median is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a data sample, a population, or a probability distribution. For a data set, it may be thought of as "the middle" value. The basic fe ...

danger had been beaten back from the territory of continental Greece and combat was taking place in the islands and in Ionia (

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

), the Cyclades entered into an alliance that would avenge Greece and pay back the damages caused by the Persians’ pillages of their possessions. This alliance was organised by Athens and is commonly called the first

Delian League

The Delian League, founded in 478 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Pl ...

. From 478-477 BC, the cities in coalition provided either ships (for example Naxos) or especially a tribute of silver. The amount of treasure owed was fixed at four hundred talents, which were deposited in the sanctuary of Apollo on the sacred island of Delos.

Rather quickly, Athens began to behave in an authoritarian manner toward its allies, before bringing them under its total domination. Naxos revolted in 469 BC

[Amouretti et Ruzé, ''Le Monde grec antique.'', p.126-129.] and became the first allied city to be transformed into a subject state by Athens, following a siege. The treasury was transferred from Delos to the

Acropolis of Athens

The Acropolis of Athens is an ancient citadel located on a rocky outcrop above the city of Athens and contains the remains of several ancient buildings of great architectural and historical significance, the most famous being the Parthenon. Th ...

around 454 BC.

Thus the Cyclades entered the “district” of the islands (along with

Imbros

Imbros or İmroz Adası, officially Gökçeada (lit. ''Heavenly Island'') since 29 July 1970,Alexis Alexandris, "The Identity Issue of The Minorities in Greece And Turkey", in Hirschon, Renée (ed.), ''Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1 ...

,

Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Anatolia, Asia Minor ...

and

Skyros

Skyros ( el, Σκύρος, ), in some historical contexts Latinized Scyros ( grc, Σκῦρος, ), is an island in Greece, the southernmost of the Sporades, an archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Around the 2nd millennium BC and slightly later, the ...

) and no longer contributed to the League except through installments of silver, the amount of which was set by the

Athenian Assembly

The ecclesia or ekklesia ( el, ) was the assembly of the citizens in city-states of ancient Greece.

The ekklesia of Athens

The ekklesia of ancient Athens is particularly well-known. It was the popular assembly, open to all male citizens as so ...

. The tribute was not too burdensome, except after a revolt, when it was increased as punishment. Apparently, Athenian domination sometimes took the form of

cleruchies (for example on Naxos and Andros).

At the beginning of the

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

, all the Cyclades except Milos and Santorini were subjects of Athens. Thus, Thucydides writes that soldiers from Kea, Andros and Tinos participated in the

Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415–413 BC during the Peloponnesian War between Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse and Corinth on the other. The expedition ended in a devas ...

and that these islands were “tributary subjects”.

The Cyclades paid a tribute until 404 BC. After that, they experienced a relative period of autonomy before entering the second Delian League and passing under Athenian control once again.

According to

Quintus Curtius Rufus

Quintus Curtius Rufus () was a Roman historian, probably of the 1st century, author of his only known and only surviving work, ''Historiae Alexandri Magni'', "Histories of Alexander the Great", or more fully ''Historiarum Alexandri Magni Macedon ...

, after (or at the same time as) the

Battle of Issus

The Battle of Issus (also Issos) occurred in southern Anatolia, on November 5, 333 BC between the Hellenic League led by Alexander the Great and the Achaemenid Empire, led by Darius III. It was the second great battle of Alexander's conquest of ...

, a Persian counter-attack led by Pharnabazus led to an occupation of Andros and Sifnos.

Hellenistic Era

An archipelago disputed among the Hellenistic kingdoms

According to Demosthenes and Diodorus of Siculus, the Thessalian tyrant

Alexander of Pherae

Alexander ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος) was Tyrant or Despot of Pherae in Thessaly, ruling from 369 to c. 356 BC. Following the assassination of Jason, the tyrant of Pherae and Tagus of Thessaly, in 370 BC, his brother Polydorus ruled for a year ...

led pirate expeditions in the Cyclades around 362-360 BC. His ships appear to have taken over several ships from the islands, among them Tinos, and brought back a large number of slaves. The Cyclades revolted during the

Third Sacred War

The Third Sacred War (356–346 BC) was fought between the forces of the Delphic Amphictyonic League, principally represented by Thebes, and latterly by Philip II of Macedon, and the Phocians. The war was caused by a large fine imposed in 3 ...

(357-355 BC), which saw the intervention of

Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

against

Phocis

Phocis ( el, Φωκίδα ; grc, Φωκίς) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the administrative region of Central Greece. It stretches from the western mountainsides of Parnassus on the east to the mountain range of Vardo ...

, allied with Pherae. Thus they began to pass into the orbit of

Macedonia.

In their struggle for influence, the leaders of the Hellenistic kingdoms often proclaimed their desire to maintain the “liberty” of the Greek cities, in reality controlled by them and often occupied by garrisons.

Thus in 314 BC,

Antigonus I Monophthalmus

Antigonus I Monophthalmus ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Μονόφθαλμος , 'the One-Eyed'; 382 – 301 BC), son of Philip from Elimeia, was a Macedonian Greek nobleman, general, satrap, and king. During the first half of his life he serv ...

created the

Nesiotic League

The League of the Islanders ( grc, τὸ κοινὸν τῶν νησιωτῶν, to koinon tōn nēsiōtōn) or Nesiotic League was a federal league (''koinon'') of ancient Greek city-states encompassing the Cyclades islands in the Aegean Sea. Or ...

around Tinos and its renowned sanctuary of

Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

and

Amphitrite

In ancient Greek mythology, Amphitrite (; grc-gre, Ἀμφιτρίτη, Amphitrítē) was the goddess of the sea, the queen of the sea, and the wife of Poseidon. She was a daughter of Nereus and Doris (or Oceanus and Tethys).Roman, L., & Rom ...

, less affected by politics than the Apollo's sanctuary on Delos.

[R. Étienne, ''Ténos II.''] Around 308 BC, the Egyptian fleet of

Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; gr, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'' "Ptolemy the Savior"; c. 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian and companion of Alexander the Great from the Kingdom of Macedon ...

sailed around the archipelago during an expedition in the Peloponnese and “liberated” Andros. The Nesiotic League would slowly be raised to the level of a federal state in the service of the

Antigonids

The Antigonid dynasty (; grc-gre, Ἀντιγονίδαι) was a Hellenistic dynasty of Dorian Greek provenance, descended from Alexander the Great's general Antigonus I Monophthalmus ("the One-Eyed") that ruled mainly in Macedonia.

History

...

, and

Demetrius I relied on it during his naval campaigns.

The islands then passed under

Ptolemaic Ptolemaic is the adjective formed from the name Ptolemy, and may refer to:

Pertaining to the Ptolemaic dynasty

* Ptolemaic dynasty, the Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter

* Ptolemaic Kingdom

Pertaining ...

domination. During the

Chremonidean War

The Chremonidean War (267–261 BC) was fought by a coalition of some Greek city-states and Ptolemaic Egypt against Antigonid Macedonian domination. It ended in a Macedonian victory which confirmed Antigonid control over the city-states of Gre ...

, mercenary garrisons had been set up on certain islands, among them Santorini, Andros and Kea. But, defeated at the

Battle of Andros sometime between 258 and 245 BC, the Ptolemies ceded them to Macedon, then ruled by

Antigonus II Gonatas

Antigonus II Gonatas ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Γονατᾶς, ; – 239 BC) was a Macedonian ruler who solidified the position of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedon after a long period defined by anarchy and chaos and acquired fame for ...

. However, because of the revolt of

Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, son of

Craterus

Craterus or Krateros ( el, Κρατερός; c. 370 BC – 321 BC) was a Macedonian general under Alexander the Great and one of the Diadochi. Throughout his life he was a loyal royalist and supporter of Alexander the Great.Anson, Edward M. (20 ...

, the Macedonians were not able to exercise complete control over the archipelago, which entered a period of instability.

Antigonus III Doson

Antigonus III Doson ( el, Ἀντίγονος Γ΄ Δώσων, 263–221 BC) was king of Macedon from 229 BC to 221 BC. He was a member of the Antigonid dynasty.

Family background

Antigonus III Doson was a half-cousin of his predecessor, Demetri ...

put the islands under control once again when he attacked

Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionians, Ionian and Dorians, Dorian Greeks colonized the west of i ...

or when he destroyed the Spartan forces at

Sellasia

Sellasia ( el, Σελλασία, before 1929: Βρουλιά - ''Vroulia'') is a village in Laconia, Greece. It was the seat of the former municipality Oinountas. Since 2011, it is part of the municipality of Sparta. Sellasia is situated on the e ...

in 222 BC.

Demetrius of Pharos

Demetrius of Pharos (also Pharus) ( grc, Δημήτριος ἐκ Φάρου and Δημήτριος ὁ Φάριος) was a ruler of Pharos involved in the First Illyrian War, after which he ruled a portion of the Illyrian Adriatic coast on beha ...

then ravaged the archipelago and was driven away from it by the Rhodians.

Philip V of Macedon

Philip V ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 238–179 BC) was king ( Basileus) of Macedonia from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of the Roman Republic. He would lead Macedon ag ...

, after the

Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

, turned his attention to the Cyclades, which he ordered the Aetolian pirate Dicearchus to ravage before taking control and installing garrisons on Andros, Paros and Kythnos.

[Livy, XXXI, XV, 8.]

After the

Battle of Cynoscephalae

The Battle of Cynoscephalae ( el, Μάχη τῶν Κυνὸς Κεφαλῶν) was an encounter battle fought in Thessaly in 197 BC between the Roman army, led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, and the Antigonid dynasty of Macedon, led by Phili ...

, the islands passed to

Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

and then to the Romans. Rhodes would give new momentum to the Nesiotic League.

Hellenistic society

In his work on Tinos,

Roland Étienne evokes a society dominated by an agrarian and patriarchal “aristocracy” marked by strong

endogamy

Endogamy is the practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting those from others as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships.

Endogamy is common in many cultu ...

. These few families had many children and derived part of their resources from a financial exploitation of the land (sales, rents, etc.), characterised by Étienne as “rural racketeering”.

This “real estate market” was dynamic due to the number of heirs and the division of inheritances at the time they were handed down. Only the purchase and sale of land could build up coherent holdings. Part of these financial resources could also be invested in commercial activities.

This endogamy might take place at the level of social class, but also at that of the entire body of citizens. It is known that the inhabitants of Delos, although living in a city with numerous foreigners—who sometimes outnumbered citizens—practiced a very strong form of civic endogamy throughout the Hellenistic period.

[A. Erskine, ''Le Monde hellénistique'', p. 414.] Although it is not possible to say whether this phenomenon occurred systematically in all the Cyclades, Delos remains a good indicator of how society may have functioned on the other islands. In fact, populations circulated more widely in the Hellenistic period than in previous eras: of 128 soldiers quartered in the garrison at Santorini by the Ptolemies, the great majority came from Asia Minor; at the end of the 1st century BC, Milos had a large Jewish population. Whether the status of citizen should be maintained was debated.

The Hellenistic era left an imposing legacy for certain of the Cyclades: towers in large numbers—on Amorgos;

[''Guide Bleu. Îles grecques.'', p. 210.] on Sifnos, where 66 were counted in 1991; and on Kea, where 27 were identified in 1956.

[John H. Young "Ancient Towers on the Island of Siphnos", ''American Journal of Archaeology'', Vol. 60, No. 1, January 1956.] Not all could have been observation towers,

as is often conjectured.

Then great number of them on Sifnos was associated with the island's mineral riches, but this quality did not exist on Kea

or Amorgos, which instead had other resources, such as agricultural products. Thus the towers appear to have reflected the islands’ prosperity during the Hellenistic era.

The commercial power of Delos

When Athens controlled it, Delos was solely a religious sanctuary. A local commerce existed and already, the “bank of Apollo” approved loans, principally to Cycladic cities.

[Amouretti et Ruzé, ''Le Monde grec antique'', p.256.] In 314 BC, the island obtained its independence, although its institutions were a facsimile of the Athenian ones. Its membership in the Nesiotic League placed it in the orbit of the Ptolemies until 245 BC.

Banking and commercial activity (in wheat storehouses and slaves) developed rapidly. In 167 BC, Delos became a free port (customs were no longer charged) and passed under Athenian control again. The island then experienced a true commercial explosion,

especially after 146 BC, when the Romans, Delos’ protectors, destroyed one of its great commercial rivals,

Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part o ...

. Foreign merchants from throughout the Mediterranean set up business there, as indicated by the terrace of foreign gods. Additionally, a synagogue is attested on Delos as of the middle of the 2nd century BC. It is estimated that in the 2nd century BC, Delos had a population of about 25,000.

The notorious “agora of the Italians” was an immense slave market. The wars between Hellenistic kingdoms were the main source of slaves, as well as pirates (who assumed the status of merchants when entering the port of Delos). When

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

(XIV, 5, 2) refers to ten thousand slaves being sold each day, it is necessary to add nuance to this claim, as the number could be the author's way of saying “many”. Moreover, a number of these “slaves” were sometimes prisoners of war (or people kidnapped by pirates) whose ransom was immediately paid upon disembarking.

This prosperity provoked jealousy and new forms of “economic exchanges”: in 298 BC, Delos transferred at least 5,000

drachmae

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fro ...

to Rhodes for its “protection against pirates”; in the middle of the 2nd century BC, Aetolian pirates launched an appeal for bids to the Aegean world to negotiate the fee to be paid in exchange for protection against their exactions.

Roman and Byzantine Empires

The Cyclades in Rome’s orbit

The reasons for Rome's intervention in Greece from the 3rd century BC are many: a call for help from the cities of

Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

; the fight against

Philip V of Macedon

Philip V ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 238–179 BC) was king ( Basileus) of Macedonia from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of the Roman Republic. He would lead Macedon ag ...

, whose naval policy troubled Rome and who had been an ally of

Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

’s; or assistance to Macedon’s adversaries in the region (

Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greece, ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a ...

,

Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

and the

Achaean League

The Achaean League (Greek: , ''Koinon ton Akhaion'' "League of Achaeans") was a Hellenistic-era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea in the northwestern Pel ...

). After his victory at

Battle of Cynoscephalae

The Battle of Cynoscephalae ( el, Μάχη τῶν Κυνὸς Κεφαλῶν) was an encounter battle fought in Thessaly in 197 BC between the Roman army, led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, and the Antigonid dynasty of Macedon, led by Phili ...

,

Flaminius proclaimed the “liberation” of Greece. Neither were commercial interests absent as a factor in Rome's involvement. Delos became a free port under the Roman Republic's protection in 167 BC. Thus Italian merchants grew wealthier, more or less at the expense of Rhodes and Corinth (

finally destroyed the same year as

Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

in 146 BC). The political system of the Greek city, on the continent and on the islands, was maintained, indeed developed, during the first centuries of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

.

According to certain historians, the Cyclades were included in the Roman province of

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

around 133-129 BC;

others place them in the province of

Achaea

Achaea () or Achaia (), sometimes transliterated from Greek as Akhaia (, ''Akhaïa'' ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Western Greece and is situated in the northwestern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. The ...

; at least, they were not divided between these two provinces. Definitive proof does not place the Cyclades in the province of Asia until the time of

Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Empi ...

and

Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavi ...

.

In 88 BC,

Mithridates VI

Mithridates or Mithradates VI Eupator ( grc-gre, Μιθραδάτης; 135–63 BC) was ruler of the Kingdom of Pontus in northern Anatolia from 120 to 63 BC, and one of the Roman Republic's most formidable and determined opponents. He was an e ...

of

Pontus

Pontus or Pontos may refer to:

* Short Latin name for the Pontus Euxinus, the Greek name for the Black Sea (aka the Euxine sea)

* Pontus (mythology), a sea god in Greek mythology

* Pontus (region), on the southern coast of the Black Sea, in modern ...

, after expelling the Romans from

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, took an interest in the Aegean. His general

Archelaus took Delos and most of the Cyclades, which he entrusted to Athens due to their declaration of favour for Mithridates. Delos managed to return to the Roman fold. As a punishment, the island was devastated by Mithridates’ troops. Twenty years later, it was destroyed once again, raided by pirates taking advantage of regional instability. The Cyclades then experienced a difficult period. The defeat of Mithridates by

Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history and became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force.

Sulla had ...

,

Lucullus

Lucius Licinius Lucullus (; 118–57/56 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, closely connected with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In culmination of over 20 years of almost continuous military and government service, he conquered the eastern kingdom ...

and then

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

returned the archipelago to Rome. In 67 BC, Pompey caused piracy, which had arisen during various conflicts, to disappear from the region. He divided the Mediterranean into different sectors led by lieutenants.

Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus

Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus (116 – soon after 56 BC), younger brother of the more famous Lucius Licinius Lucullus, was a supporter of Lucius Cornelius Sulla and consul of ancient Rome in 73 BC. As proconsul of Macedonia in 72 BC, he defea ...

was put in charge of the Cyclades. Thus, Pompey brought back the possibility of a prosperous trade for the archipelago.

[Louis Lacroix, ''Îles de la Grèce.'', p. 435.] However, it appears that a high cost of living, social inequalities and the concentration of wealth (and power) were the rule for the Cyclades during the Roman era, with their stream of abuse and discontent.

Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

, having decided that those whom he exiled could only reside on islands more than 400

stadia

Stadia may refer to:

* One of the plurals of stadium, along with "stadiums"

* The plural of stadion, an ancient Greek unit of distance, which equals to 600 Greek feet (''podes'').

* Stadia (Caria), a town of ancient Caria, now in Turkey

* Stadi ...

(50 km) from the continent, the Cyclades became places of exile, chiefly Gyaros, Amorgos and Serifos.

Vespasian organised the Cycladic archipelago into a Roman province.

Under

Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

, there existed a “province of the islands” that included the Cyclades.

Christianisation

Christianization (American and British English spelling differences#-ise.2C -ize .28-isation.2C -ization.29, or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of ...

seems to have occurred very early in the Cyclades. The catacombs at Trypiti on Milos, unique in the Aegean and in Greece, of very simple workmanship, as well as the very close baptismal fonts, confirms that a Christian community existed on the island at least from the 3rd or 4th century.

From the 4th century, the Cyclades again experienced the ravages of war. In 376, the

Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

pillaged the archipelago.

Byzantine period

Administrative organisation

When the Roman Empire was divided, control over the Cyclades passed to the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, which retained them until the 13th century.

At first, administrative organisation was based on small provinces. During the rule of

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

, the Cyclades,

Cyprus