History of surgery on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Surgery is the branch of

Surgery is the branch of

Bloodletting is one of the oldest medical practices, having been practiced among diverse ancient peoples, including the

Bloodletting is one of the oldest medical practices, having been practiced among diverse ancient peoples, including the

Around 3100 BCE Egyptian civilization began to flourish when Narmer, the first Pharaoh of Egypt, established the capital of

Around 3100 BCE Egyptian civilization began to flourish when Narmer, the first Pharaoh of Egypt, established the capital of

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is a lesser known papyrus dating from the 1600 BCE and only 5 meters in length. It is a manual for performing traumatic surgery and gives 48 case histories. The Smith Papyrus describes a treatment for repairing a broken nose, and the use of sutures to close wounds. Infections were treated with honey. For example, it gives instructions for dealing with a dislocated vertebra:

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is a lesser known papyrus dating from the 1600 BCE and only 5 meters in length. It is a manual for performing traumatic surgery and gives 48 case histories. The Smith Papyrus describes a treatment for repairing a broken nose, and the use of sutures to close wounds. Infections were treated with honey. For example, it gives instructions for dealing with a dislocated vertebra:

Roman medical practices, including surgery, were borrowed from the

Roman medical practices, including surgery, were borrowed from the

Elena de Céspedes: The eventful life of a XVI century surgeon

', in the ''Gaceta Médica de México'', 2015, 151:502-6.Emilio Maganto Pavón, ''El proceso inquisitorial contra Elena/o de Céspedes. Biografía de una cirujana transexual del siglo XVI'', Madrid, 2007.Francisco Vazquez Garcia, ''Sex, Identity and Hermaphrodites in Iberia, 1500–1800'' (2015, ), page 46. Another important early figure was German surgeon

The use of

The use of

The portrayal of surgery by various artists throughout history

A Manual of Military Surgery, by Samuel D. Gross, MD (1861)

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Surgery

Surgery is the branch of

Surgery is the branch of medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

that deals with the physical manipulation of a bodily structure to diagnose, prevent, or cure an ailment. Ambroise Paré, a 16th-century French surgeon, stated that to perform surgery is, "To eliminate that which is superfluous, restore that which has been dislocated, separate that which has been united, join that which has been divided and repair the defects of nature."

Since humans first learned how to make and handle tools, they have employed their talents to develop surgical techniques, each time more sophisticated than the last; however, until the industrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, surgeons were incapable of overcoming the three principal obstacles which had plagued the medical profession from its infancy — bleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

, pain and infection

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dis ...

. Advances in these fields have transformed surgery from a risky "art" into a scientific discipline capable of treating many diseases and conditions.

Origins

The first surgical techniques were developed to treat injuries and traumas. A combination of archaeological and anthropological studies offer insight into much earlier techniques for suturing lacerations, amputating unsalvageable limbs, and draining and cauterizing open wounds. Many examples exist: some Asian tribes used a mix of saltpeter and sulfur that was placed onto wounds and lit on fire to cauterize wounds; the Dakota people used the quill of a feather attached to an animal bladder to suck out purulent material; the discovery of needles from the Stone Age seems to suggest they were used in the suturing of cuts (the Maasai used needles of acacia for the same purpose); and tribes in India and South America developed an ingenious method of sealing minor injuries by applying termites or scarabs who bit the edges of the wound and then twisted the insects' neck, leaving their heads rigidly attached like staples.Trepanation

The oldest operation for which evidence exists istrepanation

Trepanning, also known as trepanation, trephination, trephining or making a burr hole (the verb ''trepan'' derives from Old French from Medieval Latin from Greek , literally "borer, auger"), is a surgical intervention in which a hole is drill ...

(also known as trepanning, trephination, trephining or burr hole from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''τρύπανον'' and ''τρυπανισμός''), in which a hole is drilled or scraped into the skull for exposing the dura mater

In neuroanatomy, dura mater is a thick membrane made of dense irregular connective tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. It is the outermost of the three layers of membrane called the meninges that protect the central nervous system. ...

to treat health problems related to intracranial pressure and other diseases. In the case of head wounds, surgical intervention was implemented for investigating and diagnosing the nature of the wound and the extent of the impact while bone splinters were removed preferably by scraping followed by post operation procedures and treatments for avoiding infection and aiding in the healing process. Evidence has been found in prehistoric human remains from Proto-Neolithic and Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

times, in cave paintings, and the procedure continued in use well into recorded history (being described by ancient Greek writers such as Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

). Out of 120 prehistoric skulls found at one burial site in France dated to 6500 BCE, 40 had trepanation holes. Folke Henschen, a Swedish doctor and historian, asserts that Soviet excavations of the banks of the Dnieper River

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

in the 1970s show the existence of trepanation in Mesolithic times dated to approximately 12000 BCE. The remains suggest a belief that trepanning could cure epileptic seizure

An epileptic seizure, informally known as a seizure, is a period of symptoms due to abnormally excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. Outward effects vary from uncontrolled shaking movements involving much of the body with los ...

s, migraines, and certain mental disorder

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

s.

There is significant evidence of healing of the bones of the skull in prehistoric skeletons, suggesting that many of those that proceeded with the surgery survived their operation. In some studies, the rate of survival surpassed 50%.

Amputation

The oldest known surgical amputation was carried out inBorneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and ea ...

about 31,000 years ago. The operation involved the removal of the distal third of the left lower leg. The person survived the operation and lived for another 6 to 9 years. This is the only known surgical amputation carried out before the Neolithic farming transition. The next oldest known amputation was carried out about 7000 years ago on a farmer in France whose left forearm had been surgically removed.

Setting bones

Examples of healed fractures in prehistoric human bones, suggesting setting and splinting have been found in the archeological record. Among some treatments used by the Aztecs, according to Spanish texts during the conquest of Mexico, was the reduction of fractured bones: "...the broken bone had to be splinted, extended and adjusted, and if this was not sufficient an incision was made at the end of the bone, and a branch of fir was inserted into the cavity of themedulla

Medulla or Medullary may refer to:

Science

* Medulla oblongata, a part of the brain stem

* Renal medulla, a part of the kidney

* Adrenal medulla, a part of the adrenal gland

* Medulla of ovary, a stroma in the center of the ovary

* Medulla of t ...

..." Modern medicine developed a technique similar to this in the 20th century known as medullary fixation.

Anesthesia

Bloodletting

Bloodletting is one of the oldest medical practices, having been practiced among diverse ancient peoples, including the

Bloodletting is one of the oldest medical practices, having been practiced among diverse ancient peoples, including the Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

ns, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Mayans, and the Aztecs. In Greece, bloodletting was in use around the time of Hippocrates, who mentions bloodletting but in general relied on dietary techniques. Erasistratus

Erasistratus (; grc-gre, Ἐρασίστρατος; c. 304 – c. 250 BC) was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under Seleucus I Nicator of Syria. Along with fellow physician Herophilus, he founded a school of anatomy in Alexandria, where th ...

, however, theorized that many diseases were caused by plethoras, or overabundances, in the blood, and advised that these plethoras be treated, initially, by exercise, sweating, reduced food intake, and vomiting. Herophilus

Herophilos (; grc-gre, Ἡρόφιλος; 335–280 BC), sometimes Latinised Herophilus, was a Greek physician regarded as one of the earliest anatomists. Born in Chalcedon, he spent the majority of his life in Alexandria. He was the first ...

advocated bloodletting. Archagathus, one of the first Greek physicians to practice in Rome, practiced bloodletting extensively. The art of bloodletting became very popular in the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

, and during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

one could find bloodletting calendars that recommended appropriate times to bloodlet during the year and books that claimed bloodletting would cure inflammation

Inflammation (from la, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants, and is a protective response involving immune cells, blood vessels, and molec ...

, infections

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable di ...

, strokes, manic psychosis and more.

Antiquity

Mesopotamia

The Sumerians saw sickness as a divine punishment imposed by different demons when an individual broke a rule. For this reason, to be a physician, one had to learn to identify approximately 6,000 possible demons that might cause health problems. To do this, the Sumerians employed divining techniques based on the flight of birds, position of the stars and the livers of certain animals. In this way, medicine was intimately linked to priests, relegating surgery to a second-class medical specialty. Nevertheless, the Sumerians developed several important medical techniques: in Ninevah archaeologists have discovered bronze instruments with sharpened obsidian resembling modern day scalpels, knives, trephines, etc. The Code of Hammurabi, one of the earliest Babylonian code of laws, itself contains specific legislation regulating surgeons and medical compensation as well as malpractice and victim's compensation:Egypt

Around 3100 BCE Egyptian civilization began to flourish when Narmer, the first Pharaoh of Egypt, established the capital of

Around 3100 BCE Egyptian civilization began to flourish when Narmer, the first Pharaoh of Egypt, established the capital of Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

. Just as cuneiform tablets preserved the knowledge of the ancient Sumerians, hieroglyphics preserved the Egyptians'.

In the first monarchic age (2700 BCE) the first treatise on surgery was written by Imhotep, the vizier of Pharaoh Djoser

Djoser (also read as Djeser and Zoser) was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty during the Old Kingdom, and was the founder of that epoch. He is also known by his Hellenized names Tosorthros (from Manetho) and Sesorthos (from Eusebiu ...

, priest, astronomer, physician and first notable architect. So much was he famed for his medical skill that he became the Egyptian god of medicine. Other famous physicians from the Ancient Empire (from 2500 to 2100 BCE) were Sachmet, the physician of Pharaoh Sahure

Sahure (also Sahura, meaning "He who is close to Re") was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the second ruler of the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2465 – c. 2325 BC). He reigned for about 13 years in the early 25th century BC during the Old Kingdom Period. ...

and Nesmenau, whose office resembled that of a medical director.

On one of the doorjambs of the entrance to the Temple of Memphis there is the oldest recorded engraving of a medical procedure: circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Top ...

and engravings in Kom Ombo

Kom Ombo (Egyptian Arabic: ; Coptic: ; Ancient Greek: or ; or Latin: and is an agricultural town in Egypt famous for the Temple of Kom Ombo. It was originally an Egyptian city called Nubt, meaning City of Gold (not to be confused with t ...

, Egypt depict surgical tools. Still of all the discoveries made in ancient Egypt, the most important discovery relating to ancient Egyptian knowledge of medicine is the Ebers Papyrus, named after its discoverer Georg Ebers.

The Ebers Papyrus, conserved at the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 Decemb ...

, is considered one of the oldest treaties on medicine and the most important medical papyri. The text is dated to about 1550 BCE and measures 20 meters in length. The text includes recipes, a pharmacopoeia and descriptions of numerous diseases as well as cosmetic treatments. It mentions how to surgically treat crocodile bites and serious burns, recommending the drainage of pus-filled inflammation but warns against certain diseased skin.

Edwin Smith Papyrus

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is a lesser known papyrus dating from the 1600 BCE and only 5 meters in length. It is a manual for performing traumatic surgery and gives 48 case histories. The Smith Papyrus describes a treatment for repairing a broken nose, and the use of sutures to close wounds. Infections were treated with honey. For example, it gives instructions for dealing with a dislocated vertebra:

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is a lesser known papyrus dating from the 1600 BCE and only 5 meters in length. It is a manual for performing traumatic surgery and gives 48 case histories. The Smith Papyrus describes a treatment for repairing a broken nose, and the use of sutures to close wounds. Infections were treated with honey. For example, it gives instructions for dealing with a dislocated vertebra:

India

Mehrgarh

Teeth discovered from a Neolithic graveyard inMehrgarh

Mehrgarh (; ur, ) is a Neolithic archaeological site (dated ) situated on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan in Pakistan. It is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River and between the modern-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, ...

had shown signs of drilling.

Analysis of the teeth shows prehistoric people might have attempted curing toothache with drills made from flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and sta ...

heads.

Ayurveda

Sushruta (c. 600 BCE) is considered as the "founding father of surgery". His period is usually placed between the period of 1200 BC - 600 BC. One of the earliest known mention of the name is from the ''Bower Manuscript

The Bower Manuscript is a collection of seven fragmentary Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit. treatises found buried in a Buddhist memorial stupa near Kucha, northwestern China. Written in early Gupta script (late Brahmi script) on birch bark, it is var ...

'' where Sushruta is listed as one of the ten sages residing in the Himalayas.Kutumbian, pages XXXII-XXXIII Texts also suggest that he learned surgery at Kasi

KASI (1430 AM, "News Talk 1430") is a radio station licensed to serve Ames, Iowa. The station is owned by iHeartMedia, Inc. and licensed to iHM Licenses, LLC. It airs a News/Talk radio format.

The station was assigned the KASI call letters b ...

from Lord Dhanvantari

Dhanvantari () is the physician of the devas in Hinduism. He is regarded to be an avatar of Vishnu. He is mentioned in the Puranas as the god of Ayurveda.

During his incarnation on earth, he reigned as the King of Kashi, today locally refe ...

, the god of medicine in Hindu mythology. He was an early innovator of plastic surgery who taught and practiced surgery on the banks of the Ganges

The Ganges ( ) (in India: Ganga ( ); in Bangladesh: Padma ( )). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international river to which India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China are the riparian states." is ...

in the area that corresponds to the present day city of Varanasi

Varanasi (; ; also Banaras or Benares (; ), and Kashi.) is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.

*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic t ...

in Northern India

North India is a loosely defined region consisting of the northern part of India. The dominant geographical features of North India are the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayas, which demarcate the region from the Tibetan Plateau and Central ...

. Much of what is known about Sushruta is in Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

contained in a series of volumes he authored, which are collectively known as the '' Sushruta Samhita''. It is one of the oldest known surgical texts and it describes in detail the examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of numerous ailments, as well as procedures on performing various forms of cosmetic surgery, plastic surgery

Plastic surgery is a surgical specialty involving the restoration, reconstruction or alteration of the human body. It can be divided into two main categories: reconstructive surgery and cosmetic surgery. Reconstructive surgery includes cranio ...

and rhinoplasty

Rhinoplasty ( grc, ῥίς, rhī́s, nose + grc, πλάσσειν, plássein, to shape), commonly called nose job, medically called nasal reconstruction is a plastic surgery procedure for altering and reconstructing the nose. There are two typ ...

.

Greece and the Hellenized world

Surgeons are now considered to be specializedphysician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

s, whereas in the early ancient Greek world a trained general physician had to use his hands (''χείρ'' in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

) to carry out all medical and medicinal processes including, for example, the treating of wounds sustained on the battlefield, or the treatment of broken bones (a process called in Greek: ''χειρουργείν'').

In ''The Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Ody ...

'' Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

names two doctors, “the two sons of Asklepios, the admirable physicians Podaleirius

In Greek mythology, Podalirius or Podaleirius or Podaleirios ( grc, Ποδαλείριος) was a son of Asclepius.

Description

In the account of Dares the Phrygian, Podalirius was illustrated as ". . .sturdy, strong, haughty, and moody."

...

and Machaon and one acting doctor, Patroclus. Because Machaon is wounded and Podaleirius is in combat Eurypylus In Greek mythology, Eurypylus (; grc, Εὐρύπυλος ''Eurypylos'') was the name of several different people:

* Eurypylus, was a Thessalian king, son of Euaemon and Ops. He was a former suitor of Helen thus he led the Thessalians during Tr ...

asks Patroclus “to cut out this arrow from my thigh, wash off the blood with warm water and spread soothing ointment on the wound."

Hippocrates

The Hippocratic Oath, written in the 5th century BC provides the earliest protocol for professional conduct and ethical behavior a young physician needed to abide by in life and in treating and managing the health and privacy of his patients. The multiple volumes of theHippocratic corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: ''Corpus Hippocraticum''), or Hippocratic Collection, is a collection of around 60 early Ancient Greek medical works strongly associated with the physician Hippocrates and his teachings. The Hippocratic Corpus cov ...

and the Hippocratic Oath elevated and separated the standards of proper Hippocratic medical conduct and its fundamental medical and surgical principles from other practitioners of folk medicine often laden with superstitious constructs, and/or of specialists of sorts some of whom would endeavor to carry out invasive body procedures with dubious consequences, such as lithotomy

Lithotomy from Greek for "lithos" (stone) and "tomos" ( cut), is a surgical method for removal of calculi, stones formed inside certain organs, such as the urinary tract (kidney stones), bladder ( bladder stones), and gallbladder (gallstones), ...

. Works from the Hippocratic corpus include; ''On the Articulations or On Joints'', ''On Fractures'', ''On the Instruments of Reduction'', ''The Physician's Establishment or Surgery'', ''On Injuries of the Head'', ''On Ulcers'', ''On Fistulae'', and ''On Hemorrhoids''.

Celsus and Alexandria

Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos were two greatAlexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

ns who laid the foundations for the scientific study of anatomy and physiology. Alexandrian surgeons were responsible for developments in ligature (hemostasis), lithotomy, hernia operations, ophthalmic surgery, plastic surgery, methods of reduction of dislocations and fractures, tracheotomy, and mandrake as anesthesia. Most of what we know of them comes from Celsus

Celsus (; grc-x-hellen, Κέλσος, ''Kélsos''; ) was a 2nd-century Greek philosopher and opponent of early Christianity. His literary work, ''The True Word'' (also ''Account'', ''Doctrine'' or ''Discourse''; Greek: grc-x-hellen, Λόγ� ...

and Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one ...

of Pergamum (Greek: ''Γαληνός'')Galen, On the Natural Faculties, Books I, II, and III, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard, 2000

Galen

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one ...

's On the Natural Faculties, Books I, II, and III, is an excellent paradigm of a very accomplished Greek surgeon and physician of the 2nd century Roman era, who carried out very complex surgical operations and added significantly to the corpus of animal and human physiology and the art of surgery. He was one of the first to use ligature

Ligature may refer to:

* Ligature (medicine), a piece of suture used to shut off a blood vessel or other anatomical structure

** Ligature (orthodontic), used in dentistry

* Ligature (music), an element of musical notation used especially in the me ...

s in his experiments on animals. Galen is also known as "The king of the catgut suture"Roman empire

Roman medical practices, including surgery, were borrowed from the

Roman medical practices, including surgery, were borrowed from the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

, with many Roman surgeons coming from Greece. In the 2nd century CE, Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one ...

, a Greek physician advanced Roman surgical knowledge by combining Greek and Roman medical knowledge. Aulus Cornelius Celsus

Aulus Cornelius Celsus ( 25 BC 50 AD) was a Roman encyclopaedist, known for his extant medical work, ''De Medicina'', which is believed to be the only surviving section of a much larger encyclopedia. The ''De Medicina'' is a primary source on ...

was another Roman doctor notable for advancing the field of surgery. His work '' De Medicina'' describes operations such as tonsillectomies and cataract surgery. Alongside these surgeons and doctors, Soranus of Ephesus

Soranus of Ephesus ( grc-gre, Σωρανός ὁ Ἑφέσιος; 1st/2nd century AD) was a Greek physician. He was born in Ephesus but practiced in Alexandria and subsequently in Rome, and was one of the chief representatives of the Methodic ...

introduced technology such as the birthing chair. Surgeons were attracted to ancient Rome due to the potential for success and wealth

Wealth is the abundance of valuable financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions. This includes the core meaning as held in the originating Old English word , which is from an I ...

. Doctors learned through private courses from other doctors, their relatives, in the city of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, or through self-teaching. Charlatan

A charlatan (also called a swindler or mountebank) is a person practicing quackery or a similar confidence trick in order to obtain money, power, fame, or other advantages through pretense or deception. Synonyms for ''charlatan'' include '' ...

s and malpractice

In the law of torts, malpractice, also known as professional negligence, is an "instance of negligence or incompetence on the part of a professional".Malpractice definition,

Professionals who may become the subject of malpractice actions inc ...

were common in ancient Rome, as any individual, regardless of their training or qualifications could practice medicine. This resulted in the general public becoming distrustful of doctors. Higher-quality surgeons often served the upper class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status, usually are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper class is gen ...

es. According to Celsus the perfect surgeon would be a younger man with strong and steady hands, sharp eyes, a strong spirit, and a strong sense of empathy

Empathy is the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another's position. Definitions of empathy encompass a broad range of social, co ...

and compassion. Surgery was rare in ancient Rome, it was rare for a patient to recover, and the procedure was dangerous. Most surgical procedures were limited to skin lacerations or amputations.Rimini

Rimini

Rimini ( , ; rgn, Rémin; la, Ariminum) is a city in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy and capital city of the Province of Rimini. It sprawls along the Adriatic Sea, on the coast between the rivers Marecchia (the ancient ''Ariminu ...

is home to the largest collection of ancient surgerical tools.Domus del Chirurgo or House of surgeon has the largest collection of medical implements ever found in one context.Most of the instruments were made up from iron or bronze and they used organic tools which are made up of wood,bone and leather.Two scalpels also called as ravens were used in opening of scrotum for hernia repair,curved blade were used in tonsilectomy and other small blades are used for eye surgery.Other 40 instruments were used for bone surgeries such as Trepanation and amputation.Pompeii

Most of the surgical instruments were used in Pompeii in which some were veterinary instruments.The instruments like chisels,hooks,drills,common pliers,,bone forsces, abdominal forsceps etc..It suggest that they also used vaginal speculum which indicates the practice of gynaecology and they also used rectal speculum which is used to examine the rectal speculum of intestine.China

In China, instruments resembling surgical tools have also been found in the archaeological sites ofBronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

dating from the Shang dynasty

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty and ...

, along with seeds likely used for herbalism.

Hua Tuo

Hua Tuo

Hua Tuo ( 140–208), courtesy name Yuanhua, was a Chinese physician who lived during the late Eastern Han dynasty. The historical texts ''Records of the Three Kingdoms'' and ''Book of the Later Han'' record Hua Tuo as the first person in China ...

(140–208) was a famous Chinese physician during the Eastern Han

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

and Three Kingdoms

The Three Kingdoms () from 220 to 280 AD was the tripartite division of China among the dynastic states of Cao Wei, Shu Han, and Eastern Wu. The Three Kingdoms period was preceded by the Eastern Han dynasty and was followed by the West ...

era. He was the first person to perform surgery with the aid of anesthesia, some 1600 years before the practice was adopted by Europeans. Bian Que

Bian Que (; 407 – 310 BC) was an ancient Chinese figure traditionally said to be the earliest known Chinese physician during the Warring States period. His real name is said to be Qin Yueren (), but his medical skills were so amazing that peop ...

(Pien Ch'iao) was a "miracle doctor" described by the Chinese historian Sima Qian in his Shiji

''Records of the Grand Historian'', also known by its Chinese name ''Shiji'', is a monumental history of China that is the first of China's 24 dynastic histories. The ''Records'' was written in the early 1st century by the ancient Chinese his ...

who was credited with many skills. Another book, Liezi

The ''Liezi'' () is a Taoist text attributed to Lie Yukou, a c. 5th century BC Hundred Schools of Thought philosopher. Although there were references to Lie's ''Liezi'' from the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, a number of Chinese and Western schola ...

(Lieh Tzu) describes that Bian Que conducted a two way exchange of hearts between people. This account also credited Bian Que with using general anaesthesia which would place it far before Hua Tuo, but the source in Liezi is questioned and the author may have been compiling stories from other works. Nonetheless, it establishes the concept of heart transplantation back to around 300 CE.Pre Columbian America

Inca empire

Trepanation

Trepanning, also known as trepanation, trephination, trephining or making a burr hole (the verb ''trepan'' derives from Old French from Medieval Latin from Greek , literally "borer, auger"), is a surgical intervention in which a hole is drill ...

was common among the Inca Surgeons as they are used to treat the head injury of the person who got injured in a combat.This includes removing the scalp tissue and boring the hole in the skull of the patient to allow of reducing of swelling and a draining of fluid.These techniques were so useful that only 17 to 25 percent of Inca patients died compared to 46 to 56 percent during the American civil war

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

.Aztecs

Aztecs also used various techniques of surgery ranging from Trepanation to therapeutic arthrocentries and c. They even used tractions and counter traction to reduce fractures and sprains and used splints to immoblize breaks.Aztec Surgeons were even the first to practice intramedullary fixation using wooden pegs as intramedullary rays to reunite the pieces of bone .They also practiced the procedure for therapeutic arthrocentries where human hair and cactus where used as sutures with cactus or bone needle.Middle Ages

Paul of Aegina

Paul of Aegina or Paulus Aegineta ( el, Παῦλος Αἰγινήτης; Aegina, ) was a 7th-century Byzantine Greek physician best known for writing the medical encyclopedia ''Medical Compendium in Seven Books.'' He is considered the “Father ...

's (c. 625 – c. 690 AD) ''Pragmateia'' or ''Compendiem'' was highly influential. Abulcasis Al-Zahrawi

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari ( ar, أبو القاسم خلف بن العباس الزهراوي; 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinised as Albucasis (from Arabic ''Abū al-Qāsim''), was ...

of the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

later repeated the material, largely verbatim.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq

Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (also Hunain or Hunein) ( ar, أبو زيد حنين بن إسحاق العبادي; (809–873) was an influential Nestorian Christian translator, scholar, physician, and scientist. During the apex of the Islamic ...

(809–873) was an Arab Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

Christian physician who translated many Greek medical and scientific texts, including those of Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one ...

, writing the first systematic treatment of ophthalmology

Ophthalmology ( ) is a surgical subspecialty within medicine that deals with the diagnosis and treatment of eye disorders.

An ophthalmologist is a physician who undergoes subspecialty training in medical and surgical eye care. Following a medic ...

. Egypt-born Jewish physician Isaac Israeli ben Solomon

Isaac Israeli ben Solomon (Hebrew: יצחק בן שלמה הישראלי, ''Yitzhak ben Shlomo ha-Yisraeli''; Arabic: أبو يعقوب إسحاق بن سليمان الإسرائيلي, ''Abu Ya'qub Ishaq ibn Suleiman al-Isra'ili'') ( 832 &ndas ...

(832–892) also left many medical works written in Arabic that were translated and adopted by European universities in the early 13th century.

The Persian physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (c. 865–925) advanced experimental medicine, pioneering ophthalmology and founding pediatrics. The Persian physician Ali ibn Abbas al-Majusi

'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi ( fa, علی بن عباس مجوسی; died between 982 and 994), also known as Masoudi, or Latinisation (literature), Latinized as Haly Abbas, was a Persian people, Persian physician and psychologist from the Islami ...

(d. 994) worked at the Al-Adudi Hospital in Baghdad, leaving ''The Complete Book of the Medical Art'', which stressed the need for medical ethics and discussed the anatomy and physiology of the human brain. Persian physician Avicenna (980–1037) wrote ''The Canon of Medicine'', a synthesis of Greek and Arab medicine that dominated European medicine until the mid-17th century.

In the 9th century the Medical School of Salerno in southwest Italy was founded, making use of Arabic texts and flourishing through the 13th century.

Abulcasis

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari ( ar, أبو القاسم خلف بن العباس الزهراوي; 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinised as Albucasis (from Arabic ''Abū al-Qāsim''), was ...

(936–1013) (Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-Abbas Al-Zahrawi) was an Andalusian-Arab physician and scientist who practised in the Zahra suburb of Cordoba. He is considered to be the greatest medieval surgeon, though he added little to Greek surgical practices. His works on surgery were highly influential.

African-born Italian Benedictine monk (Muslim convert) Constantine the African

Constantine the African ( la, Constantinus Africanus; died before 1098/1099, Monte Cassino) was a physician who lived in the 11th century. The first part of his life was spent in Ifriqiya and the rest in Italy. He first arrived in Italy in the ...

(died 1099) of Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Latin Valley, Italy, west of Cassino and at an elevation of . Site of the Roman town of Casinum, it is widely known for its abbey, the first ho ...

translated many Arabic medical works into Latin.

Spanish Muslim physician Avenzoar (1094–1162) performed the first tracheotomy on a goat, writing ''Book of Simplification on Therapeutics and Diet'', which became popular in Europe. Spanish Muslim physician Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

(1126–1198) was the first to explain the function of the retina and to recognize acquired immunity with smallpox.

Universities such as Montpellier, Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

and Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

were particularly renowned.

In the late 12th century Rogerius Salernitanus composed his ''Chirurgia'', laying the foundation for modern Western surgical manuals. Roland of Parma and ''Surgery of the Four Masters'' were responsible for spreading Roger's work to Italy, France, and England. Roger seems to have been influenced more by the 6th-century Aëtius and Alexander of Tralles

Alexander of Tralles ( grc-x-byzant, Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Τραλλιανός; ca. 525– ca. 605) was one of the most eminent physicians in the Byzantine Empire. His birth date may safely be put in the 6th century AD, for he mentions Aëtiu ...

, and the 7th-century Paul of Aegina

Paul of Aegina or Paulus Aegineta ( el, Παῦλος Αἰγινήτης; Aegina, ) was a 7th-century Byzantine Greek physician best known for writing the medical encyclopedia ''Medical Compendium in Seven Books.'' He is considered the “Father ...

, than by the Arabs. Hugh of Lucca

Hugh of Lucca or Hugh Borgognoni (also ''Ugo'') was a medieval surgeon. He and Theodoric of Lucca, his son or student, are noted for their use of wine as an antiseptic in the early 13th century.

Hugh of Lucca

Hugh of Lucca – also known Ugo de B ...

(1150−1257) founded the Bologna School and rejected the theory of "laudable pus".

In the 13th century in Europe skilled town craftsmen called barber-surgeons

The barber surgeon, one of the most common European medical practitioners of the Middle Ages, was generally charged with caring for soldiers during and after battle. In this era, surgery was seldom conducted by physicians, but instead by barbers ...

performed amputations and set broken bones while suffering lower status than university educated doctors. By 1308 the Worshipful Company of Barbers

The Worshipful Company of Barbers is one of the Livery Companies of the City of London, and ranks 17th in precedence.

The Fellowship of Surgeons merged with the Barbers' Company in 1540, forming the Company of Barbers and Surgeons, but after t ...

in London was flourishing. With little or no formal training, they generally had a bad reputation that was not to improve until the development of academic surgery as a specialty of medicine rather than an accessory field in the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

.

Guy de Chauliac

Guy de Chauliac (), also called Guido or Guigo de Cauliaco ( 1300 – 25 July 1368), was a French physician and surgeon who wrote a lengthy and influential treatise on surgery in Latin, titled '' Chirurgia Magna''. It was translated into many othe ...

(1298–1368) was one of the most eminent surgeons of the Middle Ages. His ''Chirurgia Magna'' or ''Great Surgery'' (1363) was a standard text for surgeons until well into the seventeenth century."Africa

Bunyuro-KitaraKingdom

In the kingdom of Bunyuro-kitara surgeries like cesarean surgery, cataract surgery were practiced.Firstly they make a precise cut from womens abdomen to the uterus and remove the newborn baby .Bannana alcohol was used as an anesthesia.Bleeding was controlled by a white hot metal rod and the wounds were covered with a soft grass mate,allowing the fluid to drain out of the abdominal cavity .The skin edges were tied together with iron spikes and covered with clean clothes and was removed after 3 to 6 days.Cataract surgery was also performed by using alkaloids plants as anesthesia.Early modern Europe

There were some important advances to the art of surgery during this period.Andreas Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius (Latinized from Andries van Wezel) () was a 16th-century anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' ' ...

(1514–1564), professor of anatomy at the University of Padua

The University of Padua ( it, Università degli Studi di Padova, UNIPD) is an Italian university located in the city of Padua, region of Veneto, northern Italy. The University of Padua was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from ...

was a pivotal figure in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

transition from classical medicine and anatomy based on the works of Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one ...

, to an empirical approach of 'hands-on' dissection. His anatomic treatise ''De humani corporis fabrica

''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (Latin, lit. "On the fabric of the human body in seven books") is a set of books on human anatomy written by Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) and published in 1543. It was a major advance in the history ...

'' exposed many anatomical errors in Galen and advocated that all surgeons should train by engaging in practical dissections themselves.

The second figure of importance in this era was Ambroise Paré (sometimes spelled "Ambrose" (c. 1510 – 1590)), a French army surgeon from the 1530s until his death in 1590. The practice for cauterizing gunshot wounds on the battlefield had been to use boiling oil, an extremely dangerous and painful procedure. Paré began to employ a less irritating emollient, made of egg yolk, rose oil

Rose oil (rose otto, attar of rose, attar of roses, or rose essence) is the essential oil extracted from the petals of various types of rose. ''Rose ottos'' are extracted through steam distillation, while ''rose absolutes'' are obtained through ...

and turpentine

Turpentine (which is also called spirit of turpentine, oil of turpentine, terebenthene, terebinthine and (colloquially) turps) is a fluid obtained by the distillation of resin harvested from living trees, mainly pines. Mainly used as a spec ...

. He also described more efficient techniques for the effective ligation of the blood vessel

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide away ...

s during an amputation. In the same century, Eleno de Céspedes became perhaps the first female surgeon in Spain, and perhaps in Europe.R. Carrillo-Esper et al., Elena de Céspedes: The eventful life of a XVI century surgeon

', in the ''Gaceta Médica de México'', 2015, 151:502-6.Emilio Maganto Pavón, ''El proceso inquisitorial contra Elena/o de Céspedes. Biografía de una cirujana transexual del siglo XVI'', Madrid, 2007.Francisco Vazquez Garcia, ''Sex, Identity and Hermaphrodites in Iberia, 1500–1800'' (2015, ), page 46. Another important early figure was German surgeon

Wilhelm Fabry

Wilhelm Fabry (also William Fabry, Guilelmus Fabricius Hildanus, or Fabricius von Hilden) (25 June 1560 − 15 February 1634), often called the "Father of German surgery", was the first educated and scientific German surgeon. He is one of the mos ...

(1540–1634), "the Father of German Surgery", who was the first to recommend amputation above the gangrenous area, and to describe a windlass (twisting stick) tourniquet. His Swiss wife and assistant Marie Colinet (1560–1640) improved the techniques for Caesarean Section, introducing the use of heat for dilating and stimulating the uterus during labor. In 1624 she became the first to use a magnet to remove metal from a patient's eye, although he received the credit.

Modern surgery

Scientific surgery

The discipline of surgery was put on a sound, scientific footing during theAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

in Europe (1715–89). An important figure in this regard was the Scottish surgical scientist (in London) John Hunter (1728–1793), generally regarded as the father of modern scientific surgery. He brought an empirical and experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into Causality, cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome oc ...

al approach to the science and was renowned around Europe for the quality of his research and his written works. Hunter reconstructed surgical knowledge from scratch; refusing to rely on the testimonies of others he conducted his own surgical experiments to determine the truth of the matter. To aid comparative analysis, he built up a collection of over 13,000 specimens of separate organ systems, from the simplest plants and animals to humans.

Hunter greatly advanced knowledge of venereal disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are Transmission (medicine), spread by Human sexual activity, sexual activity, especi ...

and introduced many new techniques of surgery, including new methods for repairing damage to the Achilles tendon

The Achilles tendon or heel cord, also known as the calcaneal tendon, is a tendon at the back of the lower leg, and is the thickest in the human body. It serves to attach the plantaris, gastrocnemius (calf) and soleus muscles to the calcaneus ( ...

and a more effective method for applying ligature of the arteries

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the pu ...

in case of an aneurysm

An aneurysm is an outward bulging, likened to a bubble or balloon, caused by a localized, abnormal, weak spot on a blood vessel wall. Aneurysms may be a result of a hereditary condition or an acquired disease. Aneurysms can also be a nidus ( ...

. He was also one of the first to understand the importance of pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

, the danger of the spread of infection

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dis ...

and how the problem of inflammation

Inflammation (from la, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants, and is a protective response involving immune cells, blood vessels, and molec ...

of the wound, bone lesion

A lesion is any damage or abnormal change in the tissue of an organism, usually caused by disease or trauma. ''Lesion'' is derived from the Latin "injury". Lesions may occur in plants as well as animals.

Types

There is no designated classif ...

s and even tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

often undid any benefit that was gained from the intervention. He consequently adopted the position that all surgical procedures should be used only as a last resort.

Hunter's student Benjamin Bell

Benjamin Bell of Hunthill FRSE FRCSEd (6 September 1749 – 5 April 1806) is considered to be the first Scottish scientific surgeon. He is commonly described as the father of the Edinburgh school of surgery,Richardson BWS, Martin MSM. Discipl ...

(1749–1806) became the first scientific surgeon in Scotland, advocating the routine use of opium in post-operative recovery, and counseling surgeons to "save skin" to speed healing; his great-grandson Joseph Bell

Joseph Bell FRCSE (2 December 1837 – 4 October 1911) was a Scottish surgeon and lecturer at the medical school of the University of Edinburgh in the 19th century. He is best known as an inspiration for the literary character Sherlock Hol ...

(1837–1911) became the inspiration for Arthur Conan Doyle's literary hero Sherlock Holmes.

Other important 18th- and early 19th-century surgeons included Percival Pott (1714–1788), who first described tuberculosis of the spine and first demonstrated that a cancer may be caused by an environmental carcinogen

A carcinogen is any substance, radionuclide, or radiation that promotes carcinogenesis (the formation of cancer). This may be due to the ability to damage the genome or to the disruption of cellular metabolic processes. Several radioactive subs ...

after he noticed a connection between chimney sweep

A chimney sweep is a person who clears soot and creosote from chimneys. The chimney uses the pressure difference caused by a hot column of gas to create a draught and draw air over the hot coals or wood enabling continued combustion. Chimneys ...

's exposure to soot and their high incidence of scrotal cancer. Astley Paston Cooper (1768–1841) first performed a successful ligation of the abdominal aorta. James Syme

James Syme (7 November 1799 – 26 June 1870) was a pioneering Scottish surgeon.

Early life

James Syme was born on 7 November 1799 at 56 Princes Street in Edinburgh. His father was John Syme WS of Cartmore and Lochore, estates in Fife a ...

(1799–1870) pioneered the Symes Amputation for the ankle joint

The ankle, or the talocrural region, or the jumping bone (informal) is the area where the foot and the leg meet. The ankle includes three joints: the ankle joint proper or talocrural joint, the subtalar joint, and the inferior tibiofibular joi ...

and successfully carried out the first hip disarticulation. Dutch surgeon Antonius Mathijsen invented the Plaster of Paris

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "re ...

cast in 1851.

Anesthesia

The European way of modern pain control through anesthesia was discovered in the mid-19th century, however, such practices were common in the 16th century Bunyoro-Kitara kingdom of modern-day Uganda Africa where the Bunyoro physicians used banana wine as an anesthetic agent, therefore, putting the patients into a comatose state before the surgery. Before the advent of anesthesia in Europe, surgery was a traumatically painful procedure and surgeons were encouraged to be as swift as possible to minimize patient suffering. The Bunyoro physician's common use of cesarian section however greatly reduced the painful and deadly danger to the mother thus often leading to full recuperation. Due to this advanced African surgical knowledge not being common around the world because of a platitude of reasons it meant that cesarian operations in Europe were largely restricted to the worst cases. Beginning in the 1840s, European surgery began to change dramatically in character with the discovery of effective and practical anesthetic chemicals such asether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups. They have the general formula , where R and R′ represent the alkyl or aryl groups. Ethers can again be ...

, first used by the American surgeon Crawford Long

Crawford Williamson Long (November 1, 1815 – June 16, 1878) was an American surgeon and pharmacist best known for his first use of inhaled sulfuric ether as an anesthetic, discovered by performing surgeries on disabled African American slaves ...

(1815–1878), and chloroform, discovered by James Young Simpson

Sir James Young Simpson, 1st Baronet, (7 June 1811 – 6 May 1870) was a Scottish obstetrician and a significant figure in the history of medicine. He was the first physician to demonstrate the anesthetic, anaesthetic properties of chloroform ...

(1811–1870) and later pioneered in England by John Snow (1813–1858), physician to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

, who in 1853 administered chloroform to her during childbirth, and in 1854 disproved the miasma theory of contagion by tracing a cholera outbreak in London to an infected water pump. In addition to relieving patient suffering, anaesthesia allowed more intricate operations in the internal regions of the human body. In addition, the discovery of muscle relaxant

A muscle relaxant is a drug that affects skeletal muscle function and decreases the muscle tone. It may be used to alleviate symptoms such as muscle spasms, pain, and hyperreflexia. The term "muscle relaxant" is used to refer to two major therap ...

s such as curare

Curare ( /kʊˈrɑːri/ or /kjʊˈrɑːri/; ''koo-rah-ree'' or ''kyoo-rah-ree'') is a common name for various alkaloid arrow poisons originating from plant extracts. Used as a paralyzing agent by indigenous peoples in Central and South ...

allowed for safer applications. American surgeon J. Marion Sims

James Marion Sims (January 25, 1813November 13, 1883) was an American physician in the field of surgery. His most famous work was the development of a surgical technique for the repair of vesicovaginal fistula, a severe complication of obstruc ...

(1813–83) received credit for helping found Gynecology, but later was criticized for failing to use anesthesia on enslaved Black test subjects.

Antiseptic surgery

The introduction of anesthetics encouraged more surgery, which inadvertently caused more dangerous patient post-operative infections. The concept of infection was mostly unknown in Europe until relatively modern times. British medical student, Robert Felkin however learned and later brought knowledge from the 16th century Bunyoro-Kitara kingdoms' medical disinfection practices to Europe, however, due to the prejudices against Africans and their knowledge those medical practices were largely ignored thus resulting in the death of thousands of Europeans. Filkins's travel through the Bunyoro kingdom led him to also witness physicians cleaning women´s abdomen with banana alcohol as well as thoroughly washing their hands and tools with the same solution before the surgeries thus showing these African's knowledge about bacterial infections. The first progress in combating infection in Europe was made in 1847 by the Hungarian doctorIgnaz Semmelweis

Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (; hu, Semmelweis Ignác Fülöp ; 1 July 1818 – 13 August 1865) was a Hungarian physician and scientist, who was an early pioneer of antiseptic procedures. Described as the "saviour of mothers", he discovered that t ...

who noticed that medical students fresh from the dissecting room were causing excess maternal death compared to midwives. Semmelweis, despite ridicule and opposition, introduced compulsory handwashing for everyone entering the maternal wards and was rewarded with a plunge in maternal and fetal deaths, however the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

dismissed his advice.

Until the pioneering work of British surgeon Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 182710 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery and preventative medicine. Joseph Lister revolutionised the craft of ...

in the 1860s, most medical men in Europe believed that chemical damage from exposures to bad air (see " miasma") was responsible for infections

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable di ...

in wounds, and facilities for washing hands or a patient's wounds were not available. Lister became aware of the work of French chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe t ...

and microbiology pioneer, Louis Pasteur, who showed that rotting and fermentation could occur under anaerobic conditions if micro-organisms were present. Pasteur suggested three methods to eliminate the micro-organisms responsible for gangrene: filtration, exposure to heat, or exposure to chemical solutions. Lister confirmed Pasteur's conclusions with his own experiments and decided to use his findings to develop antiseptic

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί ''anti'', "against" and σηπτικός ''sēptikos'', "putrefactive") is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or putre ...

techniques for wounds. As the first two methods suggested by Pasteur were inappropriate for the treatment of human tissue, Lister experimented with the third, spraying carbolic acid

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromaticity, aromatic organic compound with the molecular chemical formula, formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatility (chemistry), volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () ...

on his instruments. He found that this remarkably reduced the incidence of gangrene and he published his results in ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal and one of the oldest of its kind. It is also the world's highest-impact academic journal. It was founded in England in 1823.

The journal publishes original research articles, ...

''. Later, on 9 August 1867, he read a paper before the British Medical Association in Dublin, on the '' Antiseptic Principle of the Practice of Surgery'', which was reprinted in the ''British Medical Journal''.Modernized version of text E-text, audio at Project Gutenberg. His work was groundbreaking and laid the foundations for a rapid advance in infection control that saw modern antiseptic operating theatres widely used within 50 years.

Lister continued to develop improved methods of antisepsis

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί ''anti'', "against" and σηπτικός ''sēptikos'', "putrefactive") is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or putr ...

and asepsis

Asepsis is the state of being free from disease-causing micro-organisms (such as pathogenic bacteria, viruses, pathogenic fungi, and parasites). There are two categories of asepsis: medical and surgical. The modern day notion of asepsis is deri ...

when he realised that infection could be better avoided by preventing bacteria from getting into wounds in the first place. This led to the rise of sterile surgery. Lister instructed surgeons under his responsibility to wear clean gloves and wash their hands in 5% carbolic solution before and after operations, and had surgical instruments washed in the same solution. He also introduced the steam steriliser to sterilize equipment. His discoveries paved the way for a dramatic expansion to the capabilities of the surgeon; for his contributions he is often regarded as the father of modern surgery. These three crucial advances - the adoption of a scientific methodology toward surgical operations, the use of anaesthetic and the introduction of sterilised equipment - laid the groundwork for the modern invasive surgical techniques of today.

In the late 19th century William Stewart Halstead (1852–1922) laid out basic surgical principles for asepsis known as Halsteads principles. Halsted also introduced the latex medical glove. After one of his nurses suffered skin damage due to having to sterilize her hands with carbolic acid, Halsted had a rubber glove that could be dipped in carbolic acid designed.

X-rays

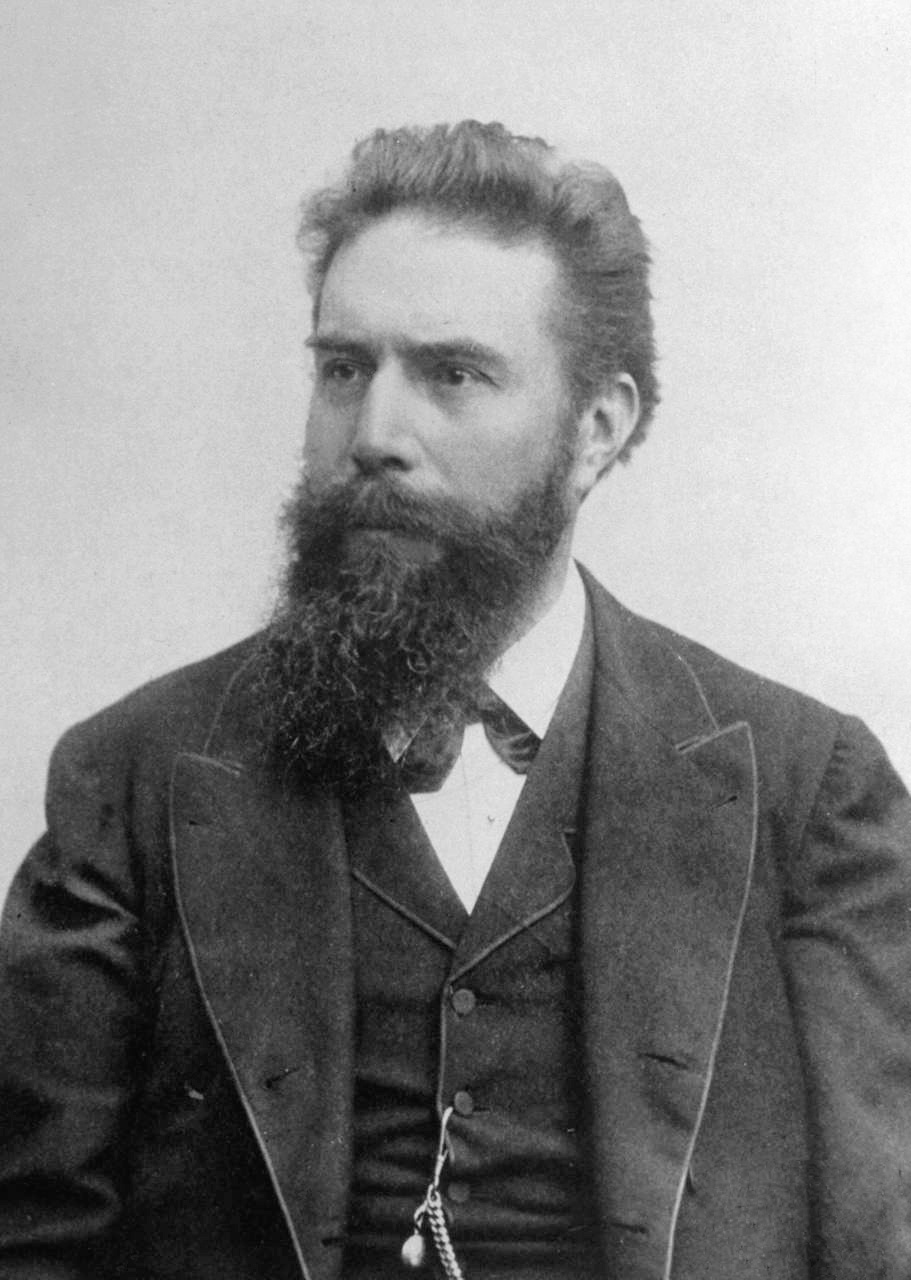

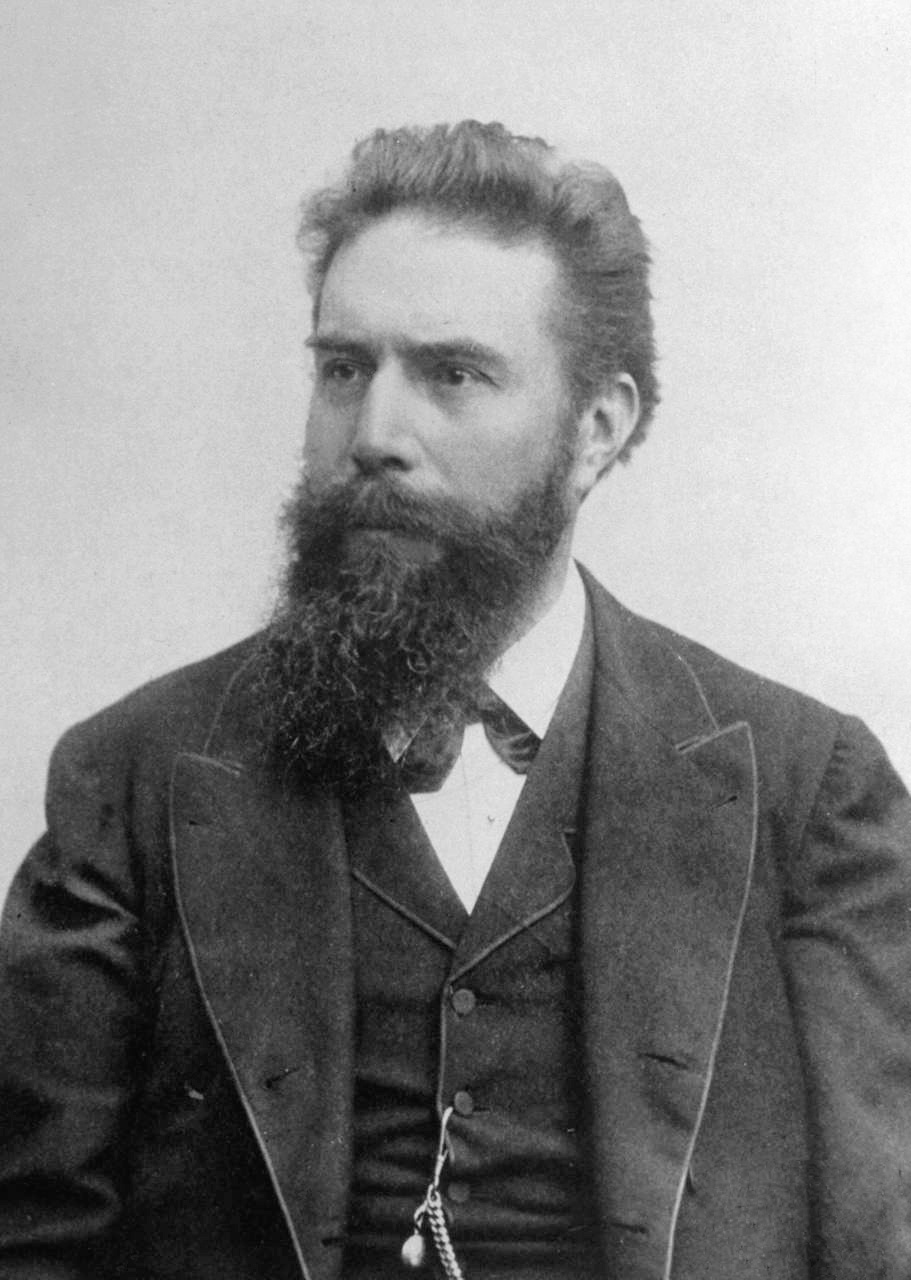

The use of

The use of X-rays

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nbs ...

as an important medical diagnostic tool began with their discovery in 1895 by German physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

Wilhelm Röntgen. He noticed that these rays could penetrate the skin, allowing the skeletal structure to be captured on a specially treated photographic plate.

Modern technologies

In the past century, a number of technologies have had a significant impact on surgical practice. These includeElectrosurgery

Electrosurgery is the application of a high-frequency (radio frequency) alternating polarity, electrical current to biological tissue as a means to cut, coagulate, desiccate, or fulgurate tissue.Hainer BL, "Fundamentals of electrosurgery", ''J ...

in the early 20th century, practical Endoscopy

An endoscopy is a procedure used in medicine to look inside the body. The endoscopy procedure uses an endoscope to examine the interior of a hollow organ or cavity of the body. Unlike many other medical imaging techniques, endoscopes are inse ...

beginning in the 1960s, and Laser surgery

Laser surgery is a type of surgery that uses a laser (in contrast to using a scalpel) to cut tissue.

Examples include the use of a laser scalpel in otherwise conventional surgery, and soft-tissue laser surgery, in which the laser beam vapor ...

, Computer-assisted surgery

Computer-assisted surgery (CAS) represents a surgical concept and set of methods, that use computer technology for surgical planning, and for guiding or performing surgical interventions. CAS is also known as computer-aided surgery, computer-assist ...

and Robotic surgery

Robotic surgery are types of surgical procedures that are done using robotic systems. Robotically assisted surgery was developed to try to overcome the limitations of pre-existing minimally-invasive surgical procedures and to enhance the capabi ...

, developed in the 1980s.

Timeline of surgery and surgical procedures

* c. 5000 BCE. First known practice ofTrepanation

Trepanning, also known as trepanation, trephination, trephining or making a burr hole (the verb ''trepan'' derives from Old French from Medieval Latin from Greek , literally "borer, auger"), is a surgical intervention in which a hole is drill ...

in Ensisheim in France.

* c. 3300 BCE. Trepanation

Trepanning, also known as trepanation, trephination, trephining or making a burr hole (the verb ''trepan'' derives from Old French from Medieval Latin from Greek , literally "borer, auger"), is a surgical intervention in which a hole is drill ...

, broken bones, wounds in Indus Valley civilization.

* c. 2613–2494 BCE. A jaw found in an Egyptian Fourth Dynasty tomb shows the marks of an operation to drain a pus-filled abscess under the first molar.

* 1754 BCE. The Code of Hammurabi.

* 1600 BCE. The Edwin Smith Papyrus from Egypt described 48 cases of injuries, fractures, wounds, dislocations, and tumors, with treatment and prognosis including closing wounds with sutures, using honey and moldy bread as antiseptics, stopping bleeding with raw meat, and immobilization for head and spinal cord injuries, reserving magic as a last resort; it contained detailed anatomical observations but showed no understanding of organ functions, along with the earliest known reference to breast cancer.

* 1550 BCE. The Ebers Papyrus from Egypt listed over 800 drugs and prescriptions.

* 1250 BCE. Asklepios and his sons Podaleirius

In Greek mythology, Podalirius or Podaleirius or Podaleirios ( grc, Ποδαλείριος) was a son of Asclepius.

Description

In the account of Dares the Phrygian, Podalirius was illustrated as ". . .sturdy, strong, haughty, and moody."

...

and Machaon were reported by Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

as battlefield surgeons. He also reported arrowheads cut out; styptics; administration of sedatives and bandaging of wounds with wool.

* 600 BCE. Sushruta of India.

* 5th century BCE. Medical schools at Cnidos

Knidos or Cnidus (; grc-gre, Κνίδος, , , Knídos) was a Greek city in ancient Caria and part of the Dorian Hexapolis, in south-western Asia Minor, modern-day Turkey. It was situated on the Datça peninsula, which forms the southern side ...

and Cos.

* 400 BCE. About this year Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

of Cos (460 BCE to 370 BCE) became "the Founder of Western Medicine", insisting on the use of scientific methods in medicine, proposing that diseases have natural causes along with the Four temperaments theory of disease, and leaving the Hippocratic Oath. He "taught that wounds should be washed in water that had been boiled or filtered, and that a doctor's hands should be kept clean, his nails clipped short." He became the first to distinguish benign from malignant breast tumors, advocating withholding treatment for "hidden" cancers, claiming that surgical intervention causes "a speedy death, but to omit treatment is to prolong life."

* 50 CE. About this time Roman physician-surgeon Aulus Cornelius Celsus

Aulus Cornelius Celsus ( 25 BC 50 AD) was a Roman encyclopaedist, known for his extant medical work, ''De Medicina'', which is believed to be the only surviving section of a much larger encyclopedia. The ''De Medicina'' is a primary source on ...

died, leaving ''De Medicina'', which described the "dilated tortuous veins" surrounding a breast cancer, causing Galen to later give cancer (Latin for crab) its name. He advised against radical mastectomy involving the pectoral muscles, and warned that surgery should only be attempted in the benign stage (first of four).

* 1st/2nd century CE. Soranus of Ephesus

Soranus of Ephesus ( grc-gre, Σωρανός ὁ Ἑφέσιος; 1st/2nd century AD) was a Greek physician. He was born in Ephesus but practiced in Alexandria and subsequently in Rome, and was one of the chief representatives of the Methodic ...

wrote a 4-volume treatise on gynaecology.

* 200 CE. About this year Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one ...

died after pioneering the use of catgut for suturing while clinging to Hippocrates Four Temperaments theory, viewing pus as beneficial, and viewing cancer as a result of melancholia caused by an excess of black bile, proven by its frequent occurrence in postmenopausal females, recommending surgical excision of a cancerous breast through healthy tissue to make sure that not "a single root" is left behind, while discouraging ligatures and cautery to allow drainage of black bile.

* 200 CE. About this year Leonidas of Alexandria began advocating the excision of breast cancer via a wide cut through normal tissues like Galen, but recommended alternate incision and cautery, which became the standard for the next 15 centuries. He provided the first detailed description of a mastectomy, which included the first description of nipple retraction as a clinical sign of breast cancer.

* 208 CE. Hua Tuo

Hua Tuo ( 140–208), courtesy name Yuanhua, was a Chinese physician who lived during the late Eastern Han dynasty. The historical texts ''Records of the Three Kingdoms'' and ''Book of the Later Han'' record Hua Tuo as the first person in China ...

began using wine and cannabis as an anesthetic during surgery.

* 476 CE. The Fall of Rome ended the advance of scientific medical-surgical knowledge in Europe.

* 1162. The Council of Tours banned the "barbarous practice" of surgery for breast cancers.

* 1180. Rogerius published ''The Practice of Surgery''.

* 1214. Hugh of Lucca

Hugh of Lucca or Hugh Borgognoni (also ''Ugo'') was a medieval surgeon. He and Theodoric of Lucca, his son or student, are noted for their use of wine as an antiseptic in the early 13th century.

Hugh of Lucca

Hugh of Lucca – also known Ugo de B ...

discovered that wine disinfects wounds.

* 1250. Theodoric Borgognoni ]

Theodoric Borgognoni (1205 – 1296/8), also known as Teodorico de' Borgognoni, and Theodoric of Lucca, was an Italian who became one of the most significant surgeons of the medieval period. A Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Bishop of Cervia ...

, student of Hugh of Lucca broke with Galen and fought pus with dry wound technique (wound cleansing and sutures).

* 1275. William of Salicet broke with Galen's love of pus and promoted a surgical knife over cauterization.

* 1308. The Worshipful Company of Barbers

The Worshipful Company of Barbers is one of the Livery Companies of the City of London, and ranks 17th in precedence.

The Fellowship of Surgeons merged with the Barbers' Company in 1540, forming the Company of Barbers and Surgeons, but after t ...

in London was first mentioned.