History of popular religion in Scotland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of popular religion in Scotland includes all forms of the formal theology and structures of institutional religion, between the earliest times of human occupation of what is now Scotland and the present day. Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. It is generally presumed to have resembled

The history of popular religion in Scotland includes all forms of the formal theology and structures of institutional religion, between the earliest times of human occupation of what is now Scotland and the present day. Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. It is generally presumed to have resembled

Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. The lack of native written sources among the

Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. The lack of native written sources among the

The Christianisation of Scotland was carried out by Irish-Scots missionaries and to a lesser extent those from Rome and England from the sixth century. This movement is traditionally associated with the figures of

The Christianisation of Scotland was carried out by Irish-Scots missionaries and to a lesser extent those from Rome and England from the sixth century. This movement is traditionally associated with the figures of

One of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the

One of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the

Traditional Protestant historiography tended to stress the corruption and unpopularity of the late Medieval Scottish church, but more recent research has indicated the ways in which it met the spiritual needs of different social groups.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 76–87. Historians have discerned a decline of monastic life in this period, with many religious houses keeping smaller numbers of monks, and those remaining often abandoning communal living for a more individual and secular lifestyle. The rate of new monastic endowments from the nobility also declined in the fifteenth century.Andrew D. M. Barrell, ''Medieval Scotland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), , p. 246. In contrast, the burghs saw the flourishing of

Traditional Protestant historiography tended to stress the corruption and unpopularity of the late Medieval Scottish church, but more recent research has indicated the ways in which it met the spiritual needs of different social groups.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 76–87. Historians have discerned a decline of monastic life in this period, with many religious houses keeping smaller numbers of monks, and those remaining often abandoning communal living for a more individual and secular lifestyle. The rate of new monastic endowments from the nobility also declined in the fifteenth century.Andrew D. M. Barrell, ''Medieval Scotland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), , p. 246. In contrast, the burghs saw the flourishing of

The Reformation, carried out in Scotland in the mid-sixteenth century and heavily influenced by

The Reformation, carried out in Scotland in the mid-sixteenth century and heavily influenced by

Scottish Protestantism in the seventeenth century was highly focused on the Bible, which was seen as infallible and the major source of moral authority. In the early part of the century the Genevan translation was commonly used.G. D. Henderson, ''Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), , pp. 1–4. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the

Scottish Protestantism in the seventeenth century was highly focused on the Bible, which was seen as infallible and the major source of moral authority. In the early part of the century the Genevan translation was commonly used.G. D. Henderson, ''Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), , pp. 1–4. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the

The kirk had considerable control over the lives of the people. It had a major role in the

The kirk had considerable control over the lives of the people. It had a major role in the

The rapid population expansion in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, particularly in the major urban centres, overtook the system of parishes on which the established church depended, leaving large numbers of "unchurched" workers, who were estranged from organised religion. The Kirk began to concern itself with providing churches in the new towns and relatively thinly supplied Highlands, establishing a church extension committee in 1828. Chaired by

The rapid population expansion in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, particularly in the major urban centres, overtook the system of parishes on which the established church depended, leaving large numbers of "unchurched" workers, who were estranged from organised religion. The Kirk began to concern itself with providing churches in the new towns and relatively thinly supplied Highlands, establishing a church extension committee in 1828. Chaired by  The beginnings of the

The beginnings of the

Church attendance in all denominations declined after World War I. Reasons that have been suggested for this change include the growing power of the nation state, socialism and scientific rationalism, which provided alternatives to the social and intellectual aspects of religion. By the 1920s roughly half the population had a relationship with one of the Christian denominations. This level was maintained until the 1940s when it dipped to 40 per cent during World War II, but it increased in the 1950s as a result of revivalist preaching campaigns, particularly the 1955 tour by Billy Graham, and returned to almost pre-war levels. From this point there was a steady decline that accelerated in the 1960s. By the 1980s it was just over 30 per cent. The decline was not even geographically, socially, or in terms of denominations. It most affected urban areas and the traditional skilled working classes and educated middle classes, while participation stayed higher in the Catholic Church than the Protestant denominations.R. J. Finley, "Secularization" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 516–17.

Sectarianism became a serious problem in the Twentieth Century. In the interwar period religious and ethnic tensions between Protestants and Catholics were exacerbated by the

Church attendance in all denominations declined after World War I. Reasons that have been suggested for this change include the growing power of the nation state, socialism and scientific rationalism, which provided alternatives to the social and intellectual aspects of religion. By the 1920s roughly half the population had a relationship with one of the Christian denominations. This level was maintained until the 1940s when it dipped to 40 per cent during World War II, but it increased in the 1950s as a result of revivalist preaching campaigns, particularly the 1955 tour by Billy Graham, and returned to almost pre-war levels. From this point there was a steady decline that accelerated in the 1960s. By the 1980s it was just over 30 per cent. The decline was not even geographically, socially, or in terms of denominations. It most affected urban areas and the traditional skilled working classes and educated middle classes, while participation stayed higher in the Catholic Church than the Protestant denominations.R. J. Finley, "Secularization" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 516–17.

Sectarianism became a serious problem in the Twentieth Century. In the interwar period religious and ethnic tensions between Protestants and Catholics were exacerbated by the

1 "Baptists and other Christian Churches in the first half of the Twentieth Century"

(2009), retrieved 30 May 2014. In the early twentieth century the Catholic Church in Scotland formalised the use of hymns, with the publication of ''The Book of Tunes and Hymns'' (1913), the Scottish equivalent of the '' Westminster Hymnal''. The foundation of the

Relations between Scotland's churches steadily improved during the second half of the twentieth century and there were several initiatives for cooperation, recognition and union. The Scottish Council of Churches was formed as an ecumenical body in 1924. Proposals in 1957 for union with the Church of England were rejected over the issue of bishops and were severely attacked in the Scottish press. The Scottish Episcopal church opened the communion table up to all baptised and communicant members of all the

Relations between Scotland's churches steadily improved during the second half of the twentieth century and there were several initiatives for cooperation, recognition and union. The Scottish Council of Churches was formed as an ecumenical body in 1924. Proposals in 1957 for union with the Church of England were rejected over the issue of bishops and were severely attacked in the Scottish press. The Scottish Episcopal church opened the communion table up to all baptised and communicant members of all the

''The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Anglican Communion''

(Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), . The decline in religious affiliation continued in the early twenty-first century. In the 2001 census, 27.5 per cent who stated that they had no religion (which compares with 15.5 per cent in the UK overall) and 5.5 per cent did not state a religion. In the 2011 census roughly 54 per cent of the population identified with a form of Christianity and 36.7 per cent stated they had no religion. Other studies suggest that those not identifying with a denomination or who see themselves as non-religious may be much higher at between 42 and 56 per cent, depending on the form of question asked. In recent years other religions have established a presence in Scotland, mainly through

The history of popular religion in Scotland includes all forms of the formal theology and structures of institutional religion, between the earliest times of human occupation of what is now Scotland and the present day. Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. It is generally presumed to have resembled

The history of popular religion in Scotland includes all forms of the formal theology and structures of institutional religion, between the earliest times of human occupation of what is now Scotland and the present day. Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. It is generally presumed to have resembled Celtic polytheism

Ancient Celtic religion, commonly known as Celtic paganism, was the religion of the ancient Celtic peoples of Europe. Because the ancient Celts did not have writing, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, Greco-Roman accounts ...

and there is evidence of the worship of spirits and wells. The Christianisation of Scotland was carried out by Irish-Scots missionaries and to a lesser extent those from Rome and England, from the sixth century. Elements of paganism survived into the Christian era (see: folk religion). The earliest evidence of religious practice is heavily biased toward monastic life. Priests carried out baptisms, masses and burials, prayed for the dead and offered sermons. The church dictated moral and legal matters and impinged on other elements of everyday life through its rules on fasting, diet, the slaughter of animals and rules on purity and ritual cleansing. One of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the Cult of Saints

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Ortho ...

, with shrines devoted to local and national figures, including St Andrew, and the establishment of pilgrimage routes (see: folk saints). Scots also played a major role in the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

. Historians have discerned a decline of monastic life in the late medieval period. In contrast, the burghs saw the flourishing of mendicant

A mendicant (from la, mendicans, "begging") is one who practices mendicancy, relying chiefly or exclusively on alms to survive. In principle, mendicant religious orders own little property, either individually or collectively, and in many inst ...

orders of friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ol ...

s in the later fifteenth century. As the doctrine of Purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgatory ...

gained importance the number of chapelries, priests and masses for the dead within parish churches grew rapidly. New "international" cults of devotion connected with Jesus and the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother o ...

began to reach Scotland in the fifteenth century. Heresy, in the form of Lollard

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

ry, began to reach Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early fifteenth century, but did not achieve a significant following.

The Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, carried out in Scotland in the mid-sixteenth century and heavily influenced by Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

, amounted to a revolution in religious practice. Sermons were now the focus of worship. The Witchcraft Act 1563

In England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, and the British colonies, there has historically been a succession of Witchcraft Acts governing witchcraft and providing penalties for its practice, or—in later years—rather for pretending to practise ...

made witchcraft, or consulting with witches, capital crimes. There were major series of trials in 1590–91, 1597

Events

January–June

* January 24 – Battle of Turnhout: Maurice of Nassau defeats a Spanish force under Jean de Rie of Varas, in the Netherlands.

* February – Bali is discovered, by Dutch explorer Cornelis Houtman.

* February 5 � ...

, 1628–31, 1649–50 and 1661–62. Prosecutions began to decline as trials were more tightly controlled by the judiciary and government, torture was more sparingly used and standards of evidence were raised. Seventy-five per cent of the accused were women and modern estimates indicate that over 1,500 persons were executed across the whole period. Scottish Protestantism in the seventeenth century was highly focused on the Bible, which was seen as infallible and the major source of moral authority. In the mid-seventeenth century Scottish Presbyterian worship took the form it was to maintain until the liturgical revival of the nineteenth century with the adoption of the Westminster Directory

The ''Directory for Public Worship'' (known in Scotland as the ''Westminster Directory'') is a liturgical manual produced by the Westminster Assembly in 1644 to replace the ''Book of Common Prayer''. Approved by the Parliament of England in 164 ...

in 1643. The seventeenth century saw the high-water mark of kirk discipline, with kirk sessions able to apply religious sanctions, such as excommunication and denial of baptism, to enforce godly behaviour and obedience. Kirk sessions also had an administrative burden in the system of poor relief and a major role in education. In the eighteenth century there were a series of reforms in church music. Communion was the central occasion of the church, conducted at most once a year, sometimes in outdoor ''holy fairs''.

Industrialisation

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

, urbanisation and the Disruption of 1843 all undermined the tradition of parish schools. Attempts to supplement the parish system included Sunday schools. By the 1830s and 1840s these had widened to include mission schools, ragged schools

Ragged schools were charitable organisations dedicated to the free education of destitute children in 19th century Britain. The schools were developed in working-class districts. Ragged schools were intended for society's most destitute children ...

, Bible societies

A Bible society is a non-profit organization, usually nondenominational in makeup, devoted to translating, publishing, and distributing the Bible at affordable prices. In recent years they also are increasingly involved in advocating its credibi ...

and improvement classes. After the Great Disruption

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of S ...

in 1843, the control of relief was removed from the church and given to parochial boards. The temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

was imported from America and by 1850 it had become a central theme in the missionary campaign to the working classes. Church attendance in all denominations declined after World War I. It increased in the 1950s as a result of revivalist preaching campaigns, particularly the 1955 tour by Billy Graham, and returned to almost pre-war levels. From this point there was a steady decline that accelerated in the 1960s. Sectarianism became a serious problem in the twentieth century. This was most marked in Glasgow in the traditionally Roman Catholic team, Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

, and the traditionally Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

team, Rangers

A Ranger is typically someone in a military/paramilitary or law enforcement role specializing in patrolling a given territory, called “ranging”. The term most often refers to:

* Park ranger or forest ranger, a person charged with protecting and ...

. Relations between Scotland's churches steadily improved during the second half of the twentieth century and there were several initiatives for cooperation, recognition and union. The foundation of the ecumenical

Ecumenism (), also spelled oecumenism, is the concept and principle that Christians who belong to different Christian denominations should work together to develop closer relationships among their churches and promote Christian unity. The adjec ...

Iona Community in 1938 led to a highly influential form of music, which was used across Britain and the US. The Dunblane consultations in 1961–69 resulted in the British "Hymn Explosion" of the 1960s, which produced multiple collections of new hymns. In recent years other religions have established a presence in Scotland, mainly through immigration, including Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

, Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

, Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

and Sikhism

Sikhism (), also known as Sikhi ( pa, ਸਿੱਖੀ ', , from pa, ਸਿੱਖ, lit=disciple', 'seeker', or 'learner, translit=Sikh, label=none),''Sikhism'' (commonly known as ''Sikhī'') originated from the word ''Sikh'', which comes fro ...

. Other minority faiths include the Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the Baháʼí Faith and the unity of religion, essential worth of all religions and Baháʼí Faith and the unity of humanity, the unity of all people. Established by ...

and small Neopagan

Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, is a term for a religion or family of religions influenced by the various historical pre-Christian beliefs of pre-modern peoples in Europe and adjacent areas of North Afric ...

groups. There are also various organisations which actively promote humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

and secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on Secularity, secular, Naturalism (philosophy), naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the Separation of church and state, separation of relig ...

.

Pre-Christian religion

Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. The lack of native written sources among the

Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. The lack of native written sources among the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

means that it can only be judged from parallels elsewhere, occasional surviving archaeological evidence and hostile accounts of later Christian writers. It is generally presumed to have resembled Celtic polytheism

Ancient Celtic religion, commonly known as Celtic paganism, was the religion of the ancient Celtic peoples of Europe. Because the ancient Celts did not have writing, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, Greco-Roman accounts ...

. The names of more than two hundred Celtic deities have been noted, some of which, like Lugh, The Dagda

The Dagda (Old Irish: ''In Dagda,'' ga, An Daghdha, ) is an important god in Irish mythology. One of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the Dagda is portrayed as a father-figure, king, and druid.Koch, John T. ''Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia ...

and The Morrigan, come from later Irish mythology, whilst others, like Teutatis, Taranis

In Celtic mythology, Taranis (Proto-Celtic: *''Toranos'', earlier ''*Tonaros''; Latin: Taranus, earlier Tanarus) is the god of thunder, who was worshipped primarily in Gaul, Hispania, Britain, and Ireland, but also in the Rhineland and Danube reg ...

and Cernunnos, come from evidence from Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

. The Celtic pagans constructed temples and shrines to venerate these gods, something they did through votive offerings and performing sacrifices, possibly including human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein ...

. According to Greek and Roman accounts, in Gaul, Britain and Ireland, there was a priestly caste of " magico-religious specialists" known as the druids, although very little is definitely known about them. Irish legends about the origin of the Picts and stories from the life of St. Ninian, associate the Picts with druids. The Picts are also associated in Christian writing with "demon" worship and one story concerning St. Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

has him exorcising a demon from a well in Pictland, suggesting that the worship of well spirits was a feature of Pictish paganism. Roman mentions of the worship of the Goddess Minerva

Minerva (; ett, Menrva) is the Roman goddess of wisdom, justice, law, victory, and the sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy. Minerva is not a patron of violence such as Mars, but of strategic war. From the second century BC onward, the Roma ...

at wells, and a Pictish stone associated with a well near Dunvegan Castle on Skye, have been taken to support this case.

Early Middle Ages

The Christianisation of Scotland was carried out by Irish-Scots missionaries and to a lesser extent those from Rome and England from the sixth century. This movement is traditionally associated with the figures of

The Christianisation of Scotland was carried out by Irish-Scots missionaries and to a lesser extent those from Rome and England from the sixth century. This movement is traditionally associated with the figures of St Ninian

Ninian is a Christian saint, first mentioned in the 8th century as being an early missionary among the Pictish peoples of what is now Scotland. For this reason he is known as the Apostle to the Southern Picts, and there are numerous dedication ...

, St Kentigern

Kentigern ( cy, Cyndeyrn Garthwys; la, Kentigernus), known as Mungo, was a missionary in the Brittonic Kingdom of Strathclyde in the late sixth century, and the founder and patron saint of the city of Glasgow.

Name

In Wales and England, this s ...

and St Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

. Elements of paganism survived into the Christian era. Sacred wells and springs became venerated as sites of pilgrimage.

Most evidence of Christian practice comes from monks and is heavily biased towards monastic life. From this can be seen the daily cycle of prayers and the celebration of the Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

. Less well recorded, but as significant, was the role of bishops and their clergy. Bishops dealt with the leaders of the tuath, ordained clergy and consecrated churches. They also had responsibilities for the poor, hungry, prisoners, widows and orphans. Priests carried out baptisms, masses and burials. They also prayed for the dead and offered sermons. They anointed the sick with oil, brought communion to the dying and administered penance to sinners. The church encouraged alms giving and hospitality. It also dictated in moral and legal matters, including marriage and inheritance. It also impinged on other elements of everyday life through its rules on fasting, diet, the slaughter of animals and rules on purity and ritual cleansing.

Early local churches were widespread, but since they were largely made of wood,G. Markus, "Religious life: early medieval", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 509–10. like that excavated at Whithorn

Whithorn ( �ʍɪthorn 'HWIT-horn'; ''Taigh Mhàrtainn'' in Gaelic), is a royal burgh in the historic county of Wigtownshire in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, about south of Wigtown. The town was the location of the first recorded Christian ...

, the only evidence that survives for most is in place names that contain words for church, including ''cill, both, eccles'' and ''annat'', but others are indicated by stone crosses and Christian burials. Beginning on the west coast and islands and spreading south and east, these were replaced with basic masonry-built buildings. Many of these were built by local lords for their tenants and followers, but often retaining a close relationship with monastic institutions.I. Maxwell, ''A History of Scotland's Masonry Construction'' in P. Wilson, ed., ''Building with Scottish Stone'' (Edinburgh: Arcamedia, 2005), , pp. 22–3.

Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne began in the eighth century. Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

, Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the no ...

and the Western Isles eventually fell to the Norsemen. Although there is evidence of varying burial rites practised by Norse settlers in Scotland, such as grave goods found on Colonsay and Westray, there is little that enables a confirmation that the Norse gods were venerated prior to the reintroduction of Christianity. The Odin Stone

The Standing Stones of Stenness is a Neolithic monument five miles northeast of Stromness on the mainland of Orkney, Scotland. This may be the oldest henge site in the British Isles. Various traditions associated with the stones survived int ...

has been used as evidence of Odin

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered Æsir, god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, v ...

ic beliefs and practices but the derivation may well be from "oathing stone". A few Scandinavian poetic references suggest that Orcadian audiences understood elements of the Norse pantheon

Pantheon may refer to:

* Pantheon (religion), a set of gods belonging to a particular religion or tradition, and a temple or sacred building

Arts and entertainment Comics

*Pantheon (Marvel Comics), a fictional organization

* ''Pantheon'' (Lone St ...

, although this is hardly conclusive proof of active beliefs. Nonetheless, it is likely that pagan practices existed in early Scandinavian Scotland.

High Middle Ages

One of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the

One of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the Cult of Saints

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Ortho ...

. Saints of Irish origin who were particularly revered included various figures called St Faelan and St. Colman, and saints Findbar and Finan. Columba remained a major figure into the fourteenth century and a new foundation was endowed by William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087 ...

(r. 1165–1214) at Arbroath Abbey. His relics, contained in the Monymusk Reliquary, were handed over to the Abbot's care.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (New York City, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1997), , pp. 52–3. Regional saints remained important to local identities. In Strathclyde the most important saint was St Kentigern, whose cult (under the pet name St. Mungo) became focused in Glasgow.A. Macquarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , p. 46. In Lothian it was St Cuthbert

Cuthbert of Lindisfarne ( – 20 March 687) was an Anglo-Saxon saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in the Kingdom of Nor ...

, whose relics were carried across the Northumbria after Lindisfarne was sacked by the Vikings before being installed in Durham Cathedral. After his martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

dom around 1115, a cult emerged in Orkney, Shetland and northern Scotland around Magnus Erlendsson, Earl of Orkney

Saint Magnus Erlendsson, Earl of Orkney, sometimes known as Magnus the Martyr, was Earl of Orkney from 1106 to about 1115.

Magnus's grandparents, Earl Thorfinn and his wife Ingibiorg Finnsdottir, had two sons, Erlend and Paul, who were twin ...

. One of the most important cults in Scotland, that of St Andrew, was established on the east coast at Kilrymont by the Pictish kings as early as the eighth century.G. W. S. Barrow, ''Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 4th edn., 2005), , p. 11. The shrine, which from the twelfth century was said to have contained the relics of the saint brought to Scotland by Saint Regulus

Saint Regulus or Saint Rule (Old Irish: ''Riagal'') was a legendary 4th century monk or bishop of Patras, Greece who in AD 345 is said to have fled to Scotland with the bones of Saint Andrew, and deposited them at St Andrews. His feast day in ...

,B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (New York City, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1997), , p. 55. began to attract pilgrims from across Scotland, but also from England and further away. By the twelfth century the site at Kilrymont had become known simply as St. Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourt ...

and it became increasingly associated with Scottish national identity and the royal family. The site was renewed as a focus for devotion with the patronage of Queen Margaret,M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (Random House, 2011), , p. 76. who also became important after her canonisation in 1250 and after the ceremonial transfer of her remains to Dunfermline Abbey, as one of the most revered national saints.

Pilgrimage was undertaken to local, national and international shrines for personal devotion, as penance imposed by a priest, or to seek cures for illness or infirmity. Written sources and pilgrim badges found in Scotland, of clay, jet and pewter, indicate journeys undertaken to Scottish shrines and further afield. The most visited pilgrimage sites in late medieval Christendom were Jerusalem, Rome and Santiago de Compostela, in Spain, but Scottish pilgrims also visited Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

in France and Canterbury in England.

Scots also played a role in the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

. Crusading was preached by friars and special taxation was raised from the late twelfth century.J. Foggie, "Church institutions: medieval", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 80–2. A contingent of Scots took part in the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ru ...

(1096–99). Significant numbers of Scots participated in the Egyptian crusades and the seventh

Seventh is the ordinal form of the number seven.

Seventh may refer to:

* Seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution

* A fraction (mathematics), , equal to one of seven equal parts

Film and television

*"The Seventh", a second-season epi ...

(1248–54) and eighth crusade

The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see ...

s (1270), led by Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the ...

. A later commentator indicated that many of these were ordinary Scotsmen. Many died of disease, including the leaders and Louis himself. This was the last great crusade, although the ideal remained a major concern of late medieval kings, including Robert I and James IV.A. Macquarrie, "Crusades", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 115–16.

The Christian calendar incorporated elements of existing practice and dominated the social life of communities. Fairs were held at Whitsun and Martinmas

Saint Martin's Day or Martinmas, sometimes historically called Old Halloween or Old Hallowmas Eve, is the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours and is celebrated in the liturgical year on 11 November. In the Middle Ages and early modern period, it ...

, at which people traded, married, moved house and conducted other public business. The mid-Winter season of Yule involved two weeks of revels in which even the clergy joined in. The feast of Corpus Christi, focused on the body of Christ and held in June, grew in importance throughout the period. The central occasion of the Christian calendar was Easter. It was preceded by the 40 days of fasting of Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

, during which preachers urged full confession, which took place in church aisles to by priests and friars. It cumulated in Easter Sunday, when most parishioners received their annual communion.

Late Middle Ages

mendicant

A mendicant (from la, mendicans, "begging") is one who practices mendicancy, relying chiefly or exclusively on alms to survive. In principle, mendicant religious orders own little property, either individually or collectively, and in many inst ...

orders of friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ol ...

s in the later fifteenth century, who, unlike the older monastic orders, placed an emphasis on preaching and ministering to the population. The order of Observant Friars were organised as a Scottish province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''Roman province, provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire ...

from 1467 and the older Franciscans and the Dominicans were recognised as separate provinces in the 1480s.

In most Scottish burgh

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Burg ...

s, in contrast to English towns where churches and parishes tended to proliferate, there was usually only one parish church, but as the doctrine of Purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgatory ...

gained importance in the period, the number of chapelries, priests and masses for the dead within them, designed to speed the passage of souls to Heaven, grew rapidly.Andrew D. M. Barrell, ''Medieval Scotland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), , p. 254. The number of altars dedicated to saints, who could intercede in this process, also grew dramatically, with St. Mary's in Dundee having perhaps 48 and St Giles' in Edinburgh over 50.P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, ''A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry'' (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), , pp. 26–9. The number of saints celebrated in Scotland also proliferated, with about 90 being added to the missal

A missal is a liturgical book containing instructions and texts necessary for the celebration of Mass throughout the liturgical year. Versions differ across liturgical tradition, period, and purpose, with some missals intended to enable a pries ...

used in St Nicholas church in Aberdeen. New "international" cults of devotion connected with Jesus and the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother o ...

began to reach Scotland in the fifteenth century, including the Five Wounds

In Catholic Church, Catholic Catholic devotions, tradition, the Five Holy Wounds, also known as the Five Sacred Wounds or the Five Precious Wounds, are the five piercing wounds that Jesus Christ suffered during his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixi ...

, the Holy Blood and the Holy Name of Jesus

In Catholicism, the veneration of the Holy Name of Jesus (also ''Most Holy Name of Jesus'', it, Santissimo Nome di Gesù) developed as a separate type of devotion in the early modern period, in parallel to that of the '' Sacred Heart''. The ...

,C. Peters, ''Women in Early Modern Britain, 1450–1640'' (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), , p. 147. but also St Joseph

Joseph (; el, Ἰωσήφ, translit=Ioséph) was a 1st-century Jewish man of Nazareth who, according to the canonical Gospels, was married to Mary, the mother of Jesus, and was the legal father of Jesus. The Gospels also name some brothers of ...

, St. Anne

According to Christianity, Christian apocryphal and Islamic tradition, Saint Anne was the mother of Mary, mother of Jesus, Mary and the maternal grandmother of Jesus. Mary's mother is not named in the Gospel#Canonical gospels, canonical gospels. ...

, the Three Kings

The biblical Magi from Middle Persian ''moɣ''(''mard'') from Old Persian ''magu-'' 'Zoroastrian clergyman' ( or ; singular: ), also referred to as the (Three) Wise Men or (Three) Kings, also the Three Magi were distinguished foreigners in the G ...

and the Apostles

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary, from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to send off". The purpose of such sending ...

, would become more significant in Scotland. There were also new religious feasts, including celebrations of the Presentation

The Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (or ''in the temple'') is an early episode in the life of Jesus Christ, describing his presentation at the Temple in Jerusalem, that is celebrated by many churches 40 days after Christmas on Candlemas, o ...

, the Visitation and Mary of the Snows.

Heresy, in the form of Lollard

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

ry, began to reach Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early fifteenth century. Lollards were followers of John Wycliffe (c. 1330–84) and later Jan Hus (c. 1369–1415), who called for reform of the Church and rejected its doctrine on the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

. Despite evidence of a number of burnings of heretics and limited popular support for its anti-sacramental elements, it probably remained a small movement.Andrew D. M. Barrell, ''Medieval Scotland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), , p. 257. There were also further attempts to differentiate Scottish liturgical practice from that in England, with a printing press established under royal patent in 1507 in order to replace the English Sarum Use for services.

Sixteenth century

The Reformation, carried out in Scotland in the mid-sixteenth century and heavily influenced by

The Reformation, carried out in Scotland in the mid-sixteenth century and heavily influenced by Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

, amounted to a revolution in religious practice. It led to the abolition of auricular confession

Confession, in many religions, is the acknowledgment of one's sins (sinfulness) or wrongs.

Christianity Catholicism

In Catholic teaching, the Sacrament of Penance is the method of the Church by which individual men and women confess sins ...

, the wafer in mass, which was no longer seen as a "work", Latin in services, prayers to Mary and the Saints and the doctrine of Purgatory. The interiors of churches were transformed, with the removal of the High Altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paganis ...

, altar rail

The altar rail (also known as a communion rail or chancel rail) is a low barrier, sometimes ornate and usually made of stone, wood or metal in some combination, delimiting the chancel or the sanctuary and altar in a church, from the nave and oth ...

s, rood screen

The rood screen (also choir screen, chancel screen, or jubé) is a common feature in late medieval church architecture. It is typically an ornate partition between the chancel and nave, of more or less open tracery constructed of wood, stone, or ...

s, choir stalls, side altars, statues and images of the saints. The colourful paintwork of the late Middle Ages was removed, with walls whitewashed to conceal murals. In place of all this were a plain table for communion, pews for the congregation, pulpits and lecterns for the sermons that were now the focus of worship. Printed sermons indicate that they could be as long as three hours. Until the 1590s most parishes were not served by a minister, but by readers, who could not preach or administer the sacraments. As a result, they might only hear a sermon once every two weeks and communion was usually administered once a year on Easter Sunday.M. Lynch, "Religious life: 1560–1660", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 512–13.

In the late Middle Ages there had been a handful of prosecutions for harm done through witchcraft, but the passing of the Witchcraft Act 1563

In England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, and the British colonies, there has historically been a succession of Witchcraft Acts governing witchcraft and providing penalties for its practice, or—in later years—rather for pretending to practise ...

made witchcraft, or consulting with witches, capital crimes. The first major series of trials under the new act were the North Berwick witch trials, beginning in 1589, in which James VI played a major part as "victim" and investigator.J. Keay and J. Keay, ''Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland'' (London: Harper Collins, 1994), , p. 556. He became interested in witchcraft and published a defence of witch-hunting in the ''Daemonologie

''Daemonologie''—in full ''Daemonologie, In Forme of a Dialogue, Divided into three Books: By the High and Mighty Prince, James &c.''—was first published in 1597 by King James VI of Scotland (later also James I of England) as a philosophi ...

'' in 1597, but he appears to have become increasingly sceptical and eventually took steps to limit prosecutions. An estimated 4,000 to 6,000 people, mostly from the Scottish Lowlands

The Lowlands ( sco, Lallans or ; gd, a' Ghalldachd, , place of the foreigners, ) is a cultural and historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Lowlands and the Highlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowl ...

, were tried for witchcraft in this period; a much higher rate than for neighbouring England. There were major series of trials in 1590–91, 1597

Events

January–June

* January 24 – Battle of Turnhout: Maurice of Nassau defeats a Spanish force under Jean de Rie of Varas, in the Netherlands.

* February – Bali is discovered, by Dutch explorer Cornelis Houtman.

* February 5 � ...

, 1628–31, 1649–50 and 1661–62. Seventy-five per cent of the accused were women and the hunt has been seen as a means of controlling women. Modern estimates indicate that over 1,500 persons were executed across the whole period.S. J. Brown, "Religion and society to c. 1900", T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, ''The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), , p. 81.

Seventeenth century

Scottish Protestantism in the seventeenth century was highly focused on the Bible, which was seen as infallible and the major source of moral authority. In the early part of the century the Genevan translation was commonly used.G. D. Henderson, ''Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), , pp. 1–4. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the

Scottish Protestantism in the seventeenth century was highly focused on the Bible, which was seen as infallible and the major source of moral authority. In the early part of the century the Genevan translation was commonly used.G. D. Henderson, ''Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), , pp. 1–4. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the Authorised King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an Bible translations into English, English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and publis ...

and the first Scots version was printed in Scotland in 1633, but the Geneva Bible continued to be employed into the seventeenth century.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 192–3. Many Bibles were large, illustrated and highly valuable objects. They often became the subject of superstitions, being used in divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout histor ...

. Family worship was strongly encouraged by the Covenanters. Books of devotion were distributed to encourage the practice and ministers were encouraged to investigate whether this was being carried out.

It was in the mid-seventeenth century that Scottish Presbyterian worship took the form it was to maintain until the liturgical revival of the nineteenth century. The adoption of the Westminster Directory

The ''Directory for Public Worship'' (known in Scotland as the ''Westminster Directory'') is a liturgical manual produced by the Westminster Assembly in 1644 to replace the ''Book of Common Prayer''. Approved by the Parliament of England in 164 ...

in 1643 meant that the Scots adopted the English Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

dislike of set forms of worship. The recitation of the Creed, Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also called the Our Father or Pater Noster, is a central Christian prayer which Jesus taught as the way to pray. Two versions of this prayer are recorded in the gospels: a longer form within the Sermon on the Mount in the Gosp ...

, Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Biblical Hebrew עשרת הדברים \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ''aséret ha-dvarím'', lit. The Decalogue, The Ten Words, cf. Mishnaic Hebrew עשרת הדיברות \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְ� ...

and Doxology were abandoned in favour of the lengthy sermon of the lecture. The centrality of the sermon meant that services tended to have a didactic and wordy in character. The only participation by the congregation was musical, in the singing of the psalms.D. Murray, "Religious life: 1650–1750" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 513–4. From the late seventeenth century the common practice was lining out, by which the precentor sang or read out each line and it was then repeated by the congregation.

The seventeenth century saw the high-water mark of kirk discipline. Kirk sessions were able to apply religious sanctions, such as excommunication and denial of baptism, to enforce godly behaviour and obedience. In more difficult cases of immoral behaviour they could work with the local magistrate, in a system modelled on that employed in Geneva.R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte "Introduction" in R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte, eds, ''Scottish Society, 1500–1800'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), , p. 30. Public occasions were treated with mistrust and from the later seventeenth century there were efforts by kirk sessions to stamp out activities such as well-dressing

Well dressing, also known as well flowering, is a tradition practised in some parts of rural England in which wells, springs and other water sources are decorated with designs created from flower petals. The custom is most closely associated with ...

, bonfire

A bonfire is a large and controlled outdoor fire, used either for informal disposal of burnable waste material or as part of a celebration.

Etymology

The earliest recorded uses of the word date back to the late 15th century, with the Catho ...

s, guising, penny wedding

This is a list of idioms that were recognizable to literate people in the late-19th century, and have become unfamiliar since.

As the article list of idioms in the English language notes, a list of idioms can be useful, since the meaning of an idi ...

s and dancing. Kirk sessions also had an administrative burden in the system of poor relief. An act of 1649 declared that local heritors were to be assessed by kirk sessions to provide the financial resources for local relief, rather than relying on voluntary contributions. By the mid-seventeenth century the system had been rolled out across the Lowlands, but was limited in the Highlands.O. P. Grell and A. Cunningham, ''Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500–1700'' (London: Routledge, 1997), , p. 37. The system was largely able to cope with general poverty and minor crises, helping the old and infirm to survive and provide life support in periods of downturn at relatively low cost, but was overwhelmed in the major subsistence crisis of the 1690s. The kirk also had a major role in education. Statutes passed in 1616

Events

January–June

* January

** Six-year-old António Vieira arrives from Portugal, with his parents, in Bahia (present-day Salvador) in Colonial Brazil, where he will become a diplomat, noted author, leading figure of the Church, an ...

, 1633

Events

January–March

* January 20 – Galileo Galilei, having been summoned to Rome on orders of Pope Urban VIII, leaves for Florence for his journey. His carriage is halted at Ponte a Centino at the border of Tuscany, where ...

, 1646

It is one of eight years (CE) to contain each Roman numeral once (1000(M)+500(D)+100(C)+(-10(X)+50(L))+5(V)+1(I) = 1646).

Events

January–March

* January 5 – The English House of Commons approves a bill to provide for Ireland ...

and 1696

Events

January–March

* January 21 – The Great Recoinage of 1696, Recoinage Act, passed by the Parliament of England to pull counterfeit silver coins out of circulation, becomes law.James E. Thorold Rogers, ''The First Nine Y ...

established a parish school system, paid for by local heritors and administered by ministers and local presbyteries. By the late seventeenth century there was a largely complete network of parish schools in the Lowlands, but in the Highlands basic education was still lacking in many areas.R. Anderson, "The history of Scottish Education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, ''Scottish Education: Post-Devolution'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), , pp. 219–28.

In the seventeenth century the pursuit of witchcraft was largely taken over by the kirk sessions and was often used to attack superstitious and Catholic practices in Scottish society. The most intense witch hunt was in 1661–62, which involved some 664 named witches in four counties. From this point prosecutions began to decline as trials were more tightly controlled by the judiciary and government, torture was more sparingly used and standards of evidence were raised. There may also have been a growing scepticism and with relative peace and stability the economic and social tensions that contributed to accusation may have reduced. There were occasional local outbreaks like that in East Lothian in 1678 and 1697 at Paisley. The last recorded executions were in 1706 and the last trial in 1727. The British parliament repealed the 1563 Act in 1736.

Eighteenth century

The kirk had considerable control over the lives of the people. It had a major role in the

The kirk had considerable control over the lives of the people. It had a major role in the Poor Law

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

and schools, which were administered through the parishes, and over the morals of the population, particularly over sexual offences such as adultery and fornication. A rebuke was necessary for moral offenders to "purge their scandal". This involved standing or sitting before the congregation for up to three Sundays and enduring a rant by the minister. There was sometimes a special repentance stool near the pulpit for this purpose. In a few places the subject was expected to wear sackcloth. From the 1770s private rebukes were increasingly administered by the kirk session, particularly for men from the social elites, while until the 1820s the poor were almost always give a public rebuke. In the early part of the century the kirk, particularly in the Lowlands, attempted to suppress dancing and events like penny wedding

This is a list of idioms that were recognizable to literate people in the late-19th century, and have become unfamiliar since.

As the article list of idioms in the English language notes, a list of idioms can be useful, since the meaning of an idi ...

s at which secular tunes were played.J. Porter, "Introduction" in J. Porter, ed., ''Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century'' (Peter Lang, 2007), , p. 22. The oppression of secular music and dancing by the kirk began to ease between about 1715 and 1725.

From the second quarter of the eighteenth century it was argued that lining out should be abandoned in favour of the practice of singing the psalms stanza by stanza.B. D. Spinks, ''A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons'' (Scarecrow Press, 2009), , pp. 143–4. In the second half of the century these innovations became linked to a choir movement that included the setting up of schools to teach new tunes and singing in four parts.B. D. Spinks, ''A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons'' (Scarecrow Press, 2009), , p. 26.

Among Episcopalians, Qualified Chapel

A Qualified Chapel, in eighteenth and nineteenth century Scotland, was an Episcopal congregation that worshipped liturgically but accepted the Hanoverian monarchy and thereby "qualified" under the Scottish Episcopalians Act 1711 for exemption fr ...

s used the English ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

''. They installed organs and hired musicians, following the practice in English parish churches, singing in the liturgy as well as metrical psalms, while the non-jurors had to worship covertly and less elaborately. When the two branches united in the 1790s, the non-juring branch soon absorbed the musical and liturgical traditions of the qualified churches. Catholic worship was deliberately low key, usually in the private houses of recursant landholders or in domestic buildings adapted for services. Surviving chapels from this period are generally austere and simply furnished. Typical worship consisted of a sermon, long vernacular prayers and Low Mass in Latin. Musical accompaniment was prohibited until the nineteenth century, when organs began to be introduced into chapels.

Communion was the central occasion of the church, conducted infrequently, at most once a year. Communicants were examined by a minister and elders, proving their knowledge of the Shorter Catechism

The Westminster Shorter Catechism is a catechism written in 1646 and 1647 by the Westminster Assembly, a synod of English and Scottish theologians and laymen intended to bring the Church of England into greater conformity with the Church of Scot ...

. They were then given communion tokens that entitled them to take part in the ceremony. Long tables were set up in the middle of the church at which communicants sat to receive communion. Where ministers refused or neglected parish communion, largely assemblies were carried out in the open air, often combining several parishes. These large gatherings were discouraged by the General Assembly, but continued. They could become mixed with secular activities and were commemorated as such by Robert Burns in the poem ''Holy Fair''. They could also be occasions for evangelical meetings, as at the Cambuslang Wark.

Nineteenth century

The rapid population expansion in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, particularly in the major urban centres, overtook the system of parishes on which the established church depended, leaving large numbers of "unchurched" workers, who were estranged from organised religion. The Kirk began to concern itself with providing churches in the new towns and relatively thinly supplied Highlands, establishing a church extension committee in 1828. Chaired by

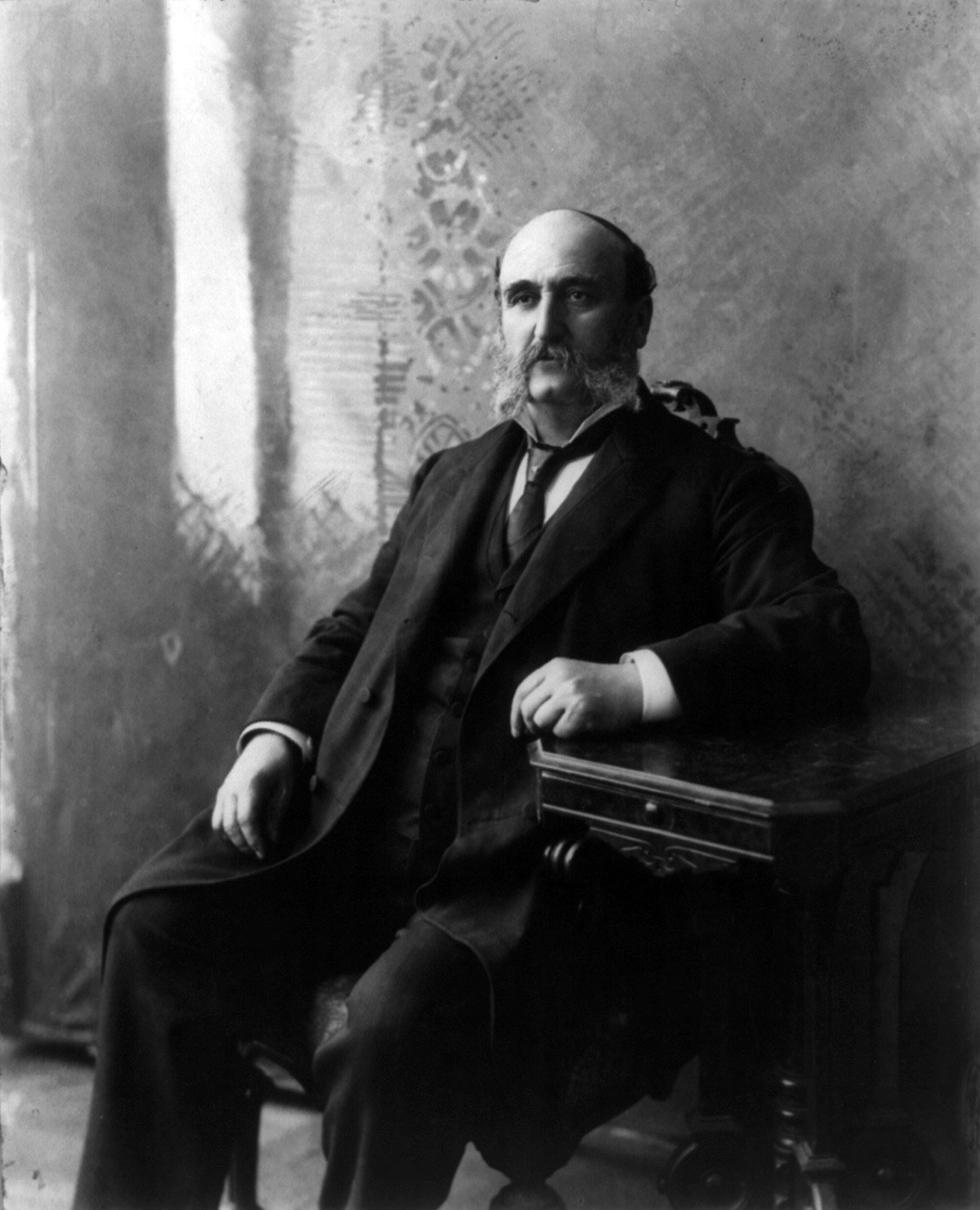

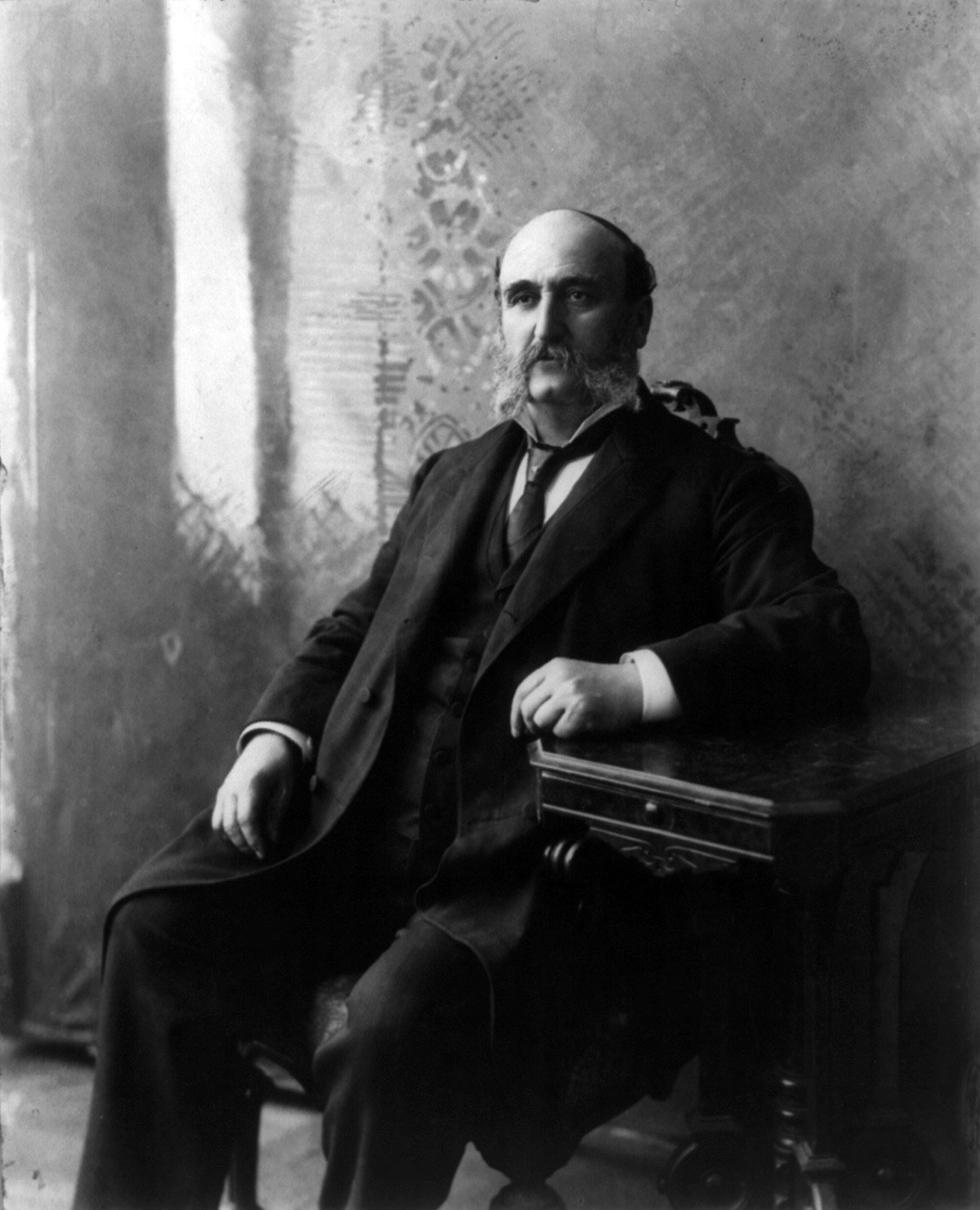

The rapid population expansion in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, particularly in the major urban centres, overtook the system of parishes on which the established church depended, leaving large numbers of "unchurched" workers, who were estranged from organised religion. The Kirk began to concern itself with providing churches in the new towns and relatively thinly supplied Highlands, establishing a church extension committee in 1828. Chaired by Thomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland. He has been called "Scotland's greatest nine ...

, by the early 1840s it had added 222 churches, largely through public subscription.C. Brooks, "Introduction", in C. Brooks, ed., ''The Victorian Church: Architecture and Society'' (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), , pp. 17–18. The new churches were most attractive to the middle classes and skilled workers. The majority of those in severe hardship could not afford pew rents needed to attend and remained outside of the church system.

Industrialisation, urbanisation and the Disruption of 1843 all undermined the tradition of parish schools.T. M. Devine, ''The Scottish Nation, 1700–2000'' (London: Penguin Books, 2001), , pp. 91–100. Attempts to supplement the parish system included Sunday schools. Originally begun in the 1780s by town councils, they were adopted by all religious denominations in the nineteenth century. By the 1830s and 1840s these had widened to include mission schools, ragged schools

Ragged schools were charitable organisations dedicated to the free education of destitute children in 19th century Britain. The schools were developed in working-class districts. Ragged schools were intended for society's most destitute children ...

, Bible societies

A Bible society is a non-profit organization, usually nondenominational in makeup, devoted to translating, publishing, and distributing the Bible at affordable prices. In recent years they also are increasingly involved in advocating its credibi ...

and improvement classes, open to members of all forms of Protestantism and particularly aimed at the growing urban working classes. By 1890 the Baptists had more Sunday schools than churches and were teaching over 10,000 children. The number would double by 1914.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 403. The problem of a rapidly growing industrial workforce meant that the Old Poor Law, based on parish relief administered by the church, had broken down in the major urban centres. Thomas Chambers, who advocated self-help as a solution, lobbied forcibly for the exclusion of the able bodied from relief and that payment remained voluntary, but in periods of economic downturn genuine suffering was widespread. After the Disruption in 1845 the control of relief was removed from the church and given to parochial boards, but the level of relief remained inadequate for the scale of the problem.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , pp. 392–3.

The beginnings of the

The beginnings of the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

can be traced to 1828–29 in Maryhill and Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

, when it was imported from America. By 1850 it had become a central theme in the missionary campaign to the working classes. A new wave of temperance societies included the United Order of Female Rechabites and the Independent Order of Good Templars

The International Organisation of Good Templars (IOGT; founded as the Independent Order of Good Templars), whose international body is known as Movendi International, is a fraternal organization which is part of the temperance movement, promotin ...

, which arrived from the US in 1869 and within seven years had 1,100 branches in Scotland. The Salvation Army also placed an emphasis on sobriety.G. M. Ditchfield, ''The Evangelical Revival'' (London: Routledge, 1998), , p. 91. The Catholic Church had its own temperance movement, founding Catholic Total Abstinence Society in 1839. They made common cause with the Protestant societies, holding joint processions.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 404. Other religious-based organisations that expanded in this period included the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

, which had 15,000 members in Glasgow by the 1890s. Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

also made advances in the late nineteenth century, particularly among skilled artisans.

There was a liturgical revival in the late nineteenth century strongly influenced by the English Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of O ...

, which encouraged a return to Medieval forms of architecture and worship, including the reintroduction of accompanied music into the Church of Scotland.B. D. Spinks, ''A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons'' (Scarecrow Press, 2009), , p. 149. The revival saw greater emphasis on the liturgical year and sermons tended to become shorter.D. M. Murray, "Sermons", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 581–2. The Church Service Society was founded in 1865 to promote liturgical study and reform. A year later organs were officially admitted to Church of Scotland churches. They began to be added to churches in large numbers and by the end of the century roughly a third of Church of Scotland ministers were members of the society and over 80 per cent of kirks had both organs and choirs. However, they remained controversial, with considerable opposition among conservative elements within the church and organs were never placed in some churches. In the Episcopalian Church the influence of the Oxford Movement and links with the Anglican Church led to the introduction of more traditional services and by 1900 surplice

A surplice (; Late Latin ''superpelliceum'', from ''super'', "over" and ''pellicia'', "fur garment") is a liturgical vestment of Western Christianity. The surplice is in the form of a tunic of white linen or cotton fabric, reaching to the kne ...

d choirs and musical services were the norm. The Free Church was more conservative over music, and organs were not permitted until 1883.S. J. Brown, "Beliefs and religions" in T. Griffiths and G. Morton, ''A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1800 to 1900'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), , p. 122. Hymns were first introduced in the United Presbyterian Church in the 1850s. They became common in the Church of Scotland and Free Church in the 1870s. The Church of Scotland adopted a hymnal with 200 songs in 1870 and the Free Church followed suit in 1882. The visit of American Evangelists Ira D. Sankey

Ira David Sankey (August 28, 1840 – August 13, 1908) was an American gospel singer and composer, known for his long association with Dwight L. Moody in a series of religious revival campaigns in America and Britain during the closing decades o ...

(1840–1908), and Dwight L. Moody

Dwight Lyman Moody (February 5, 1837 – December 26, 1899), also known as D. L. Moody, was an American evangelist and publisher connected with Keswickianism, who founded the Moody Church, Northfield School and Mount Hermon School in Massa ...

(1837–99) to Edinburgh and Glasgow in 1874–75 helped popularise accompanied church music in Scotland.P. Maloney, ''Scotland and the Music Hall, 1850–1914'' (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), , p. 197. Sankey made the harmonium so popular that working-class mission congregations pleaded for the introduction of accompanied music.

The Moody-Sankey hymn book remained a best seller into the twentieth century.

Early Twentieth Century

Church attendance in all denominations declined after World War I. Reasons that have been suggested for this change include the growing power of the nation state, socialism and scientific rationalism, which provided alternatives to the social and intellectual aspects of religion. By the 1920s roughly half the population had a relationship with one of the Christian denominations. This level was maintained until the 1940s when it dipped to 40 per cent during World War II, but it increased in the 1950s as a result of revivalist preaching campaigns, particularly the 1955 tour by Billy Graham, and returned to almost pre-war levels. From this point there was a steady decline that accelerated in the 1960s. By the 1980s it was just over 30 per cent. The decline was not even geographically, socially, or in terms of denominations. It most affected urban areas and the traditional skilled working classes and educated middle classes, while participation stayed higher in the Catholic Church than the Protestant denominations.R. J. Finley, "Secularization" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 516–17.

Sectarianism became a serious problem in the Twentieth Century. In the interwar period religious and ethnic tensions between Protestants and Catholics were exacerbated by the

Church attendance in all denominations declined after World War I. Reasons that have been suggested for this change include the growing power of the nation state, socialism and scientific rationalism, which provided alternatives to the social and intellectual aspects of religion. By the 1920s roughly half the population had a relationship with one of the Christian denominations. This level was maintained until the 1940s when it dipped to 40 per cent during World War II, but it increased in the 1950s as a result of revivalist preaching campaigns, particularly the 1955 tour by Billy Graham, and returned to almost pre-war levels. From this point there was a steady decline that accelerated in the 1960s. By the 1980s it was just over 30 per cent. The decline was not even geographically, socially, or in terms of denominations. It most affected urban areas and the traditional skilled working classes and educated middle classes, while participation stayed higher in the Catholic Church than the Protestant denominations.R. J. Finley, "Secularization" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 516–17.

Sectarianism became a serious problem in the Twentieth Century. In the interwar period religious and ethnic tensions between Protestants and Catholics were exacerbated by the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...