History of Freiburg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The History of

The History of

The Habsburgers took up Freiburg on their promise. For the wars against the Swiss Confederacy, the citizens of Freiburg had to financially support and provide knights. In 1386, the Swiss were victorious in the bloody

The Habsburgers took up Freiburg on their promise. For the wars against the Swiss Confederacy, the citizens of Freiburg had to financially support and provide knights. In 1386, the Swiss were victorious in the bloody

When the Swedish King

When the Swedish King

The War of Devolution from 1667 until 1668, in which Louis XIV asserted the Province of Brabant's claims and sent his troops into the Spanish Netherlands, left Freiburg untouched. Also, in the next

The War of Devolution from 1667 until 1668, in which Louis XIV asserted the Province of Brabant's claims and sent his troops into the Spanish Netherlands, left Freiburg untouched. Also, in the next  The War of the Spanish Succession from 1701 to 1713 began in which the

The War of the Spanish Succession from 1701 to 1713 began in which the

In Breisgau, the first and spiritual state was the most important despite the secularisation of a part of the church's possessions, because of its abundant wealth, including the monasteries of St. Peter, St. Blasien and St. Trudpert. The second state included the old imperial aristocracy with its lands, but also the low-income knights established by the generous ennoblement of the Habsburgers. They gave a firm scaffolding for administrative officers, lawyers and university professors of the feudal society. At the third state were the bourgeoisie, well organised in guilds and who had come into prosperity. On the other hand, were the peasants. Even if they were no longer alive, they were still dependent on the ecclesiastical and secular landowners.

Inwardly, it remained quiet in Breisgau, ''as our nation was ... neither so spoiled, nor so depressed, nor as enthusiastic'', as

In Breisgau, the first and spiritual state was the most important despite the secularisation of a part of the church's possessions, because of its abundant wealth, including the monasteries of St. Peter, St. Blasien and St. Trudpert. The second state included the old imperial aristocracy with its lands, but also the low-income knights established by the generous ennoblement of the Habsburgers. They gave a firm scaffolding for administrative officers, lawyers and university professors of the feudal society. At the third state were the bourgeoisie, well organised in guilds and who had come into prosperity. On the other hand, were the peasants. Even if they were no longer alive, they were still dependent on the ecclesiastical and secular landowners.

Inwardly, it remained quiet in Breisgau, ''as our nation was ... neither so spoiled, nor so depressed, nor as enthusiastic'', as

In 1864, the city and state councils were merged into the Freiburg District Office. The District Offices of Breisach, Emmendingen, Ettenhiem, Freiburg, Kenzingen (dissolved in 1872), Neustadt in the Black Forest and

In 1864, the city and state councils were merged into the Freiburg District Office. The District Offices of Breisach, Emmendingen, Ettenhiem, Freiburg, Kenzingen (dissolved in 1872), Neustadt in the Black Forest and  In 1910, the new city theatre was opened on the western edge of the inner city. in 1911, the opening of the new university building (Kollegiengebäude I) was built directly opposite the theatre.

During Winterer's reign as mayor, new residential areas such as the Wiehre and Stühlinger were established. As a result, the number of buildings and inhabitants of Freiburg doubled. This was also due to the influx of older and wealthy people from the industrial areas of West Germany or from Hamburg, where

In 1910, the new city theatre was opened on the western edge of the inner city. in 1911, the opening of the new university building (Kollegiengebäude I) was built directly opposite the theatre.

During Winterer's reign as mayor, new residential areas such as the Wiehre and Stühlinger were established. As a result, the number of buildings and inhabitants of Freiburg doubled. This was also due to the influx of older and wealthy people from the industrial areas of West Germany or from Hamburg, where

The unification of Alsace to France after the loss of the First World War meant for Freiburg the loss of part of its land. The city also lost its garrison when a 50 kilometre demilitarised zone was established on the right bank of the Rhine, where industrial settlements were banned. Both of these contributed to the economic decline of the region.

In the newly founded Weimar Republic in 1920, 68 year-old lawyer, centre delegate and parliamentary president

The unification of Alsace to France after the loss of the First World War meant for Freiburg the loss of part of its land. The city also lost its garrison when a 50 kilometre demilitarised zone was established on the right bank of the Rhine, where industrial settlements were banned. Both of these contributed to the economic decline of the region.

In the newly founded Weimar Republic in 1920, 68 year-old lawyer, centre delegate and parliamentary president  In 1923, in accordance to the initiative set out by French parliamentary deputy and pacifist Marc Sangnier, about 7,000 people from 23 nations gathered at the 3rd International Peace Congress in Freiburg to discuss ways of reducing hatred between nations, understanding the international situation and overcoming the war. One of the German representatives was

In 1923, in accordance to the initiative set out by French parliamentary deputy and pacifist Marc Sangnier, about 7,000 people from 23 nations gathered at the 3rd International Peace Congress in Freiburg to discuss ways of reducing hatred between nations, understanding the international situation and overcoming the war. One of the German representatives was

At the end of January 1933, the Nazis seized power in Berlin; Freiburg was soon to follow:

* On 6 March, the Nazis hoisted the swastika flag at the Freiburg City Hall without consent from Mayor Karl Bender, whereupon, the leader of the district and editor of the National Socialists' based in Upper Baden's battle organ "Der Alemanne" Franz Kerber, as well as SA-Oberführer

At the end of January 1933, the Nazis seized power in Berlin; Freiburg was soon to follow:

* On 6 March, the Nazis hoisted the swastika flag at the Freiburg City Hall without consent from Mayor Karl Bender, whereupon, the leader of the district and editor of the National Socialists' based in Upper Baden's battle organ "Der Alemanne" Franz Kerber, as well as SA-Oberführer

badische-zeitung.de: ''Agenten landen am Kaiserstuhl''

/ref> From early Summer of 1940 to November 1944, Josef Mengele, the

Digitalisat

. *

Digitalisat

. *

Geschichte Freiburgs

in der digitalisierten ''

Onlineausgabe des Urkundenbuchs der Stadt Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburgs Geschichte in Zitaten

Historisches Freiburg

The History of

The History of Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic German, Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population o ...

can be traced back 900 years. Around 100 years after Freiburg was founded in 1120 by the Zähringer, until their family died out. The unloved Counts of Freiburg

The Counts of Freiburg were the descendants of Count Egino of Urach (d. 1236/7). They ruled over the city of Freiburg and the Breisgau (within the Margraviate of Baden) between approximately 1245 and 1368.

History

The Margraviate of Baden had ...

followed as the town lords, who then sold it onto the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

ers. At the start of the 19th century, the (catholic) Austrian ownership of the town ended, when Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, after having invaded the town, decreed the town and Breisgau to be a part of the Grand Duchy of Baden

The Grand Duchy of Baden (german: Großherzogtum Baden) was a state in the southwest German Empire on the east bank of the Rhine. It existed between 1806 and 1918.

It came into existence in the 12th century as the Margraviate of Baden and subs ...

in 1806. Until 1918, Freiburg belonged to the Grand Duchy, until 1933 to the Weimar Republic and '' Gau'' Baden in Nazi Germany. After the Second World War, the town was the state capital of (South) Baden from 1949 until 1952. Today, Freiburg is the fourth-largest city in Baden-Württemberg.

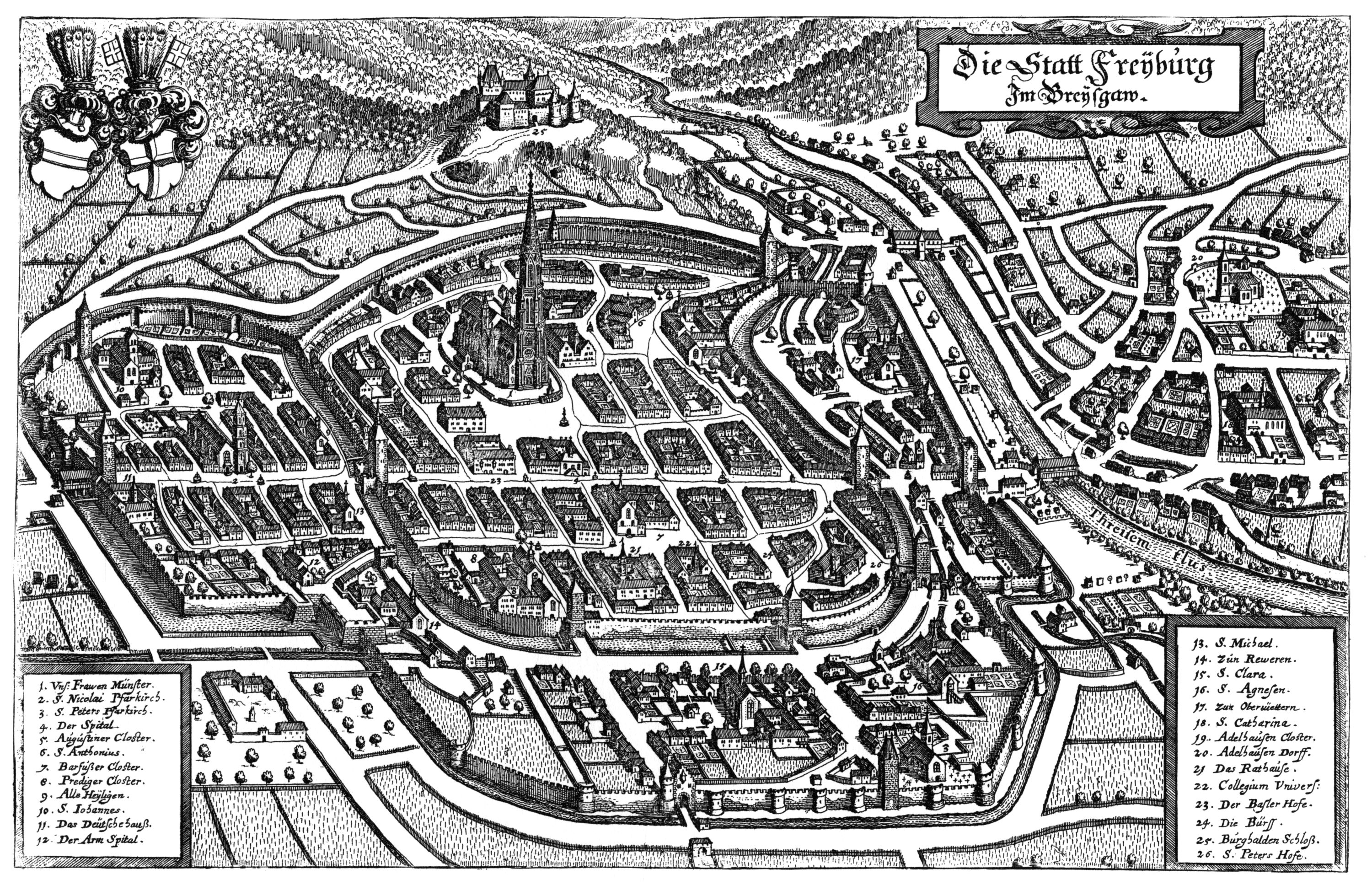

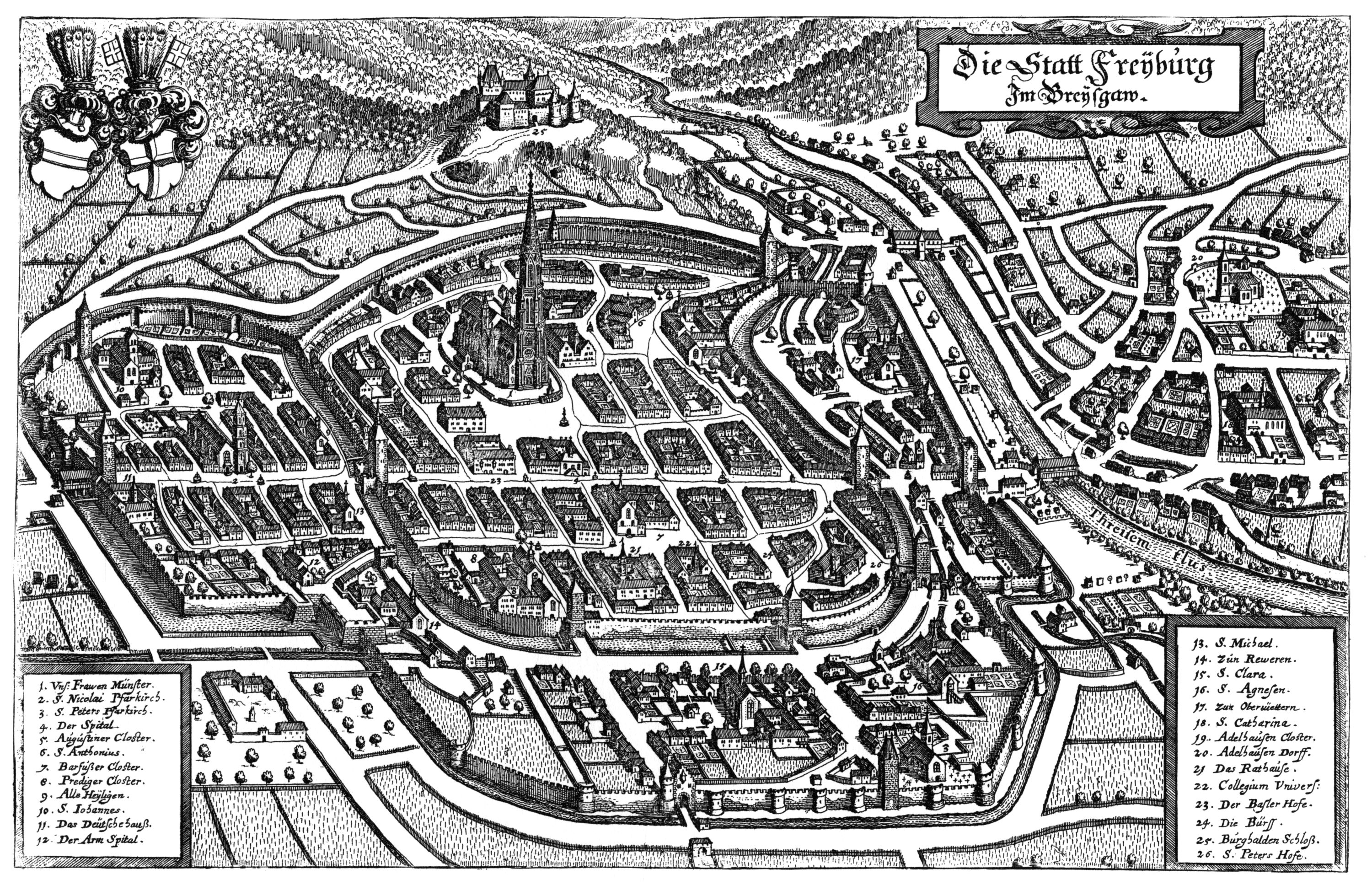

Founding of the Castle and the City

The first reference of habitation in the modern-day Freiburg, the Wiehre and Herdern, was documented in 1008. A trade route crossed through south of Zähringen, a modern-day part of Freiburg, and Herdern near the Dreisam, through the Rhine Valley, modern-day Zähringer-, Habsburger- andKaiser-Joseph-Straße

The Kaiser-Joseph-Straße (often shortened to ''Kajo'') in Freiburg im Breisgau is a shopping street of about 900 meters, which runs through the center of Freiburg's historic downtown from north to south. It is one of the most expensive locatio ...

and an imperial road towards Breisach/Colmar

Colmar (, ; Alsatian: ' ; German during 1871–1918 and 1940–1945: ') is a city and commune in the Haut-Rhin department and Grand Est region of north-eastern France. The third-largest commune in Alsace (after Strasbourg and Mulhouse), it is ...

(modern-day Salz- and Bertoldstraße).

In approximately 1091, Berthold II of Zähringen

Berthold II ( – 12 April 1111), also known as Berchtold II, was the Duke of Swabia from 1092 to 1098.

After he conceded the Duchy of Swabia to the Staufer in 1098, the title of "Duke of Zähringen" was created for him, in use from c. 1100 and c ...

built a castle, Castrum de Friburch, on top of the modern-day Schlossberg in order to control the trade routes. A settlement of servants and craftsmen at the foot of the castle belonged to the new area, with the settlement being situated in the modern-day region of the Altstadt (English Old Town) and Oberlinden, which stood under particular protection from the lord. The settlement grew, which was founded by Konrad, the brother of the current Duke, Berthold III, and he then went on to grant a market for the settlement in 1120. He granted the residents extensive privileges, such as the relief from farmstead taxes and the free voting for the pastor.

Also noticeable was the planned network of water, called Bächle, in 1170, to provide water to the Altstadt in the streets, whose water comes from the Dreisam and was used to supply industrial and cleaning water in the Middle Ages, which also served as available means to extinguish fires. Drinking water was supplied to the town by wooden pipes called (Deicheln, in Freiburg Deichele) from sources above the city and was accessible from fountains. Runzgenossenschaften, or canal cooperatives, were formed to manage and maintain the watercourses in the city, such as the Bächle and Runzen (canals) for trade operation (such as tannery, pellet grinding, etc.).

The city's rise

Silver, which was discovered at the end of the 10th century to the west of the Black Forest, made the city richer. The Zähringer received the mining rights from the Bishops of Basel, who in turn had received the mountain shelf from Emperor Konrad II in 1028. With the rise of Freiburg, the city church, where Bernhard von Clairvaux had preached the SecondCrusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were i ...

in 1146, soon turned out to be too small, which meant the last ruler of the Zähringer dynasty Bertold V. began the construction of a new parish church around 1200. The Freiburg Minster was first built in Romanesque style, but later finished in Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

. After his death in 1218, Bertold V. was buried as the last Zähringer in the Minster founded by him. A council already existed before 1178 under his predecessor, Bertold IV. The council was established during Bertold V's reign. Probably the council in Freiburg, like in the episcopal cities of the Upper Rhine, developed from a township advisory council, which emerged from the municipal community involved in the court.

The Counts of Urach as Counts of Freiburg

After Zähringer's died out in 1218, Egino I, the nephew of Bertold V, the first Count of Urach, who then called themselves Counts of Freiburg and resided in the Schlossberg castle above Freiburg. Since the citizens did not trust their new rule, they wrote their old rights granted by the Zähringen into a council constitution (the Stadtrodel of 1218), after which 24 councilors from the old ruling houses ruled Freiburg. Starting from 1248 councils which changed yearly supervened. At the end of the 13th century, craftsmen came to the town council through the guilds. In the 13th century, several clerical orders were built within the city walls. The Dominicans founded the Preacher's Monastery, Predigerkloster, in 1236, where Albertus Magnus held office of the post-mortem from 1236 to 1238. From 1240 the first mention of a Johanniterhaus is dated. In 1246, Count Konrad surrendered the Martinskapelle to the begging of the Franciscans with four court houses. The barber monks erected their monastery there, and until 1318 they built the chapel to the still existing Martinskirche. The origins of the German Order of Freiburg date from 1258. In the narrow old town of 1278, the Augustiners between Salzstraße and Stadtmauer found a place for their monastery. The years under the rule of the Counts of Freiburg stood out due to the frequent feuds between the Counts and the city. These feuds often always concerned money. In 1299, the citizens of Freiburg refused to comply with the new demands set out by Count Egino II and shot down his castle on top of the Schlossberg with catapults. Because of this, Egino called on support from his brother-in-lawConrad of Lichtenberg

Conrad of Lichtenberg (german: Konrad von Lichtenberg; french: Conrad de Lichtenberg; 1240 – 1 August 1299) was a bishop of Strasbourg in the 13th century.

Lichtenberg was born to a wealthy family and entered the clergy at the age of 13. He ...

, the Bishop of Strasbourg. In the subsequent battle, the Bishop was killed - a citizen of Freiburg called Hauri is said to have stabbed him with a spear - and resulted in a victory for the city. However, the citizens had to pay the Count a yearly reparation for killing the bishop. When Count Egino III tried to penetrate the city at night with an army detachment, the citizens of Freiburg destroyed the castle on the Schlossberg. In order to finally rid the Counts´ rule, the citizens bought their freedom in 1368 with 20,000 Mark* silver and subsequently submitted themselves voluntarily to the House of Habsburg for protection. The city then belonged to Further Austria and shared ups and downs with the Habsburgers until the German Reich was dissolved in 1805. Despite this, Freiburg merged with numerous other mints on both sides of the Upper Rhine in 1377 and the so-called "Rappenmünzbund" in Switzerland. Among them included Colmar and Thann in Alsace, Basel, Schaffhausen, Zurich and Bern in Switzerland and in Sundgau. This universal mint system expanded trade across the Upper Rhine. The Rappen penny, used in Freiburg, was the main unit of currency. In 1584, this union was dissolved.

*One Mark had a weight of 237.5 in Silver and served as the basic parameter with a subdivision of 678 pennies.

Freiburg under the Habsburgers

The Habsburgers took up Freiburg on their promise. For the wars against the Swiss Confederacy, the citizens of Freiburg had to financially support and provide knights. In 1386, the Swiss were victorious in the bloody

The Habsburgers took up Freiburg on their promise. For the wars against the Swiss Confederacy, the citizens of Freiburg had to financially support and provide knights. In 1386, the Swiss were victorious in the bloody Battle of Sempach

The Battle of Sempach was fought on 9 July 1386, between Leopold III, Duke of Austria and the Old Swiss Confederacy. The battle was a decisive Swiss victory in which Duke Leopold and numerous Austrian nobles died. The victory helped turn the lo ...

. They did not just slay the Austrian Duke Leopold III, but almost the entire Freiburg nobility. As a result, the guilds took over the power of the city council.

After Frederick IV, Duke of Austria had helped Antipope John XXIII who had been deposed at the Council of Constance

The Council of Constance was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the res ...

to flee to Freiburg in 1415, King Sigismund imposed the imperial ban, or ''Reichsacht'' in German, on the Habsburg Duke. Thus, Breisgau fell back as a fief to the empire and Freiburg was an imperial city from 1415 until Frederick was pardoned in 1425.

In 1448, Archduke Albrecht, the lord of the Habsburg foreland, established a general university in Freiburg, from which, with the founding charter of 1457, formed the University of Freiburg.

A highlight of Freiburg's history was the imperial diet to Freiburg in 1498 convened by King of the Romans

King of the Romans ( la, Rex Romanorum; german: König der Römer) was the title used by the king of Germany following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002–1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German k ...

Maximillian I. During the diet, Maximillian and the estate-based society negotiated the initiation of a Swiss peace treaty. However, nothing came about from this because the Swiss rejected both the imperial taxes and the jurisdiction of the Reichskammergericht, or Imperial Chamber Court, as well as, after having defeated Maximillian's army in 1499 in the Swabian War at Dornach

: ''Dornach is also a quarter of the French city of Mulhouse and the Scots name for Dornoch in the Scottish Highlands, and Dòrnach is the Gaelic name for Dornoch in the Scottish Highlands.''

Dornach (Swiss German: ''Dornech'') is a municipalit ...

, separated from their obligations to the Holy Roman Empire.

After the raised presbytery was completed, the Bishop of Constance inaugurated the Freiburg Minster in 1513. In the same year, under the Bundschuh movement, peasants concentrated themselves in Freiburg alongside their leader Joß Fritz. The uprising was betrayed and ended before it could actually start. As a result, there was an exemplary punishment for the participants in the uprising.

Reformation and the Peasants' War

Despite the previous uprising, the Reformation and above all the spreading of Martin Luther's work ''On the Freedom of a Christian

''On the Freedom of a Christian'' (Latin: ''"De Libertate Christiana"''; German: ''"Von der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen"''), sometimes also called ''"A Treatise on Christian Liberty"'' (November 1520), was the third of Martin Luther’s major ...

'' led to more rebellious activities arising. On 23 May 1525, 18,000 peasants led by Hans Müller captured Freiburg during the German Peasants' War

The German Peasants' War, Great Peasants' War or Great Peasants' Revolt (german: Deutscher Bauernkrieg) was a widespread popular revolt in some German-speaking areas in Central Europe from 1524 to 1525. It failed because of intense oppositio ...

and forced the city council to join an evangelical ''Christian organisation to establish common public peace and eradicate the unfair grievances of the common poor man''. After defeating the uprising, the city of Freiburg assured the House of Habsburg of its good Catholic attitude. Alongside Freiburg, Breisach, Waldkirch and Endingen all confirmed their Catholic stance, whilst Kenzingen, Neuenburg, Rheinfelden, Waldshut and Strasbourg all conformed to Protestantism. In 1529, when the iconoclasts fundamentally supported Protestantism, the prominent scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam (until 1535) and the cathedral chapter of Basel fled to Catholic Freiburg. They arrived at The Whale House

The Whale House (''Haus zum Walfisch'') is a late Gothic bourgeois house in the old town of Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany and is under conservation. The building is currently used by the ''Sparkasse Freiburg-Nördlicher Breisgau ...

and the Basler Hof respectively.

From the 15th until the 17th century, plague epidemics continued to occur in Freiburg. One of the worst epidemics was in 1564, when around 2000 people, a quarter of the population, died from the plague, as reported by town doctor Johannes Schenck.

Witch-hunting in Freiburg

Similar to the situation across Europe, witch trials took place in Freiburg. Between 1550 and 1628, 131 out of 302 convicted witches were executed. The proportion of women, who had been transferred to "the vile vice of sorcery and witchcraft", was substantially higher than the proportion of men. On 24 March 1599, Catharina Stadellmenin, Anna Wolffartin and Margaretha Mößmerin among others were beheaded in Freiburg and burned outside of the city. A memorial plaque on theMartinstor

The Martinstor (English ''Martin's Gate''), a former town fortification on Kaiser-Joseph-Straße, is the older of the two gates of Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, that have been preserved since medieval times. Both gates, the Martinstor and the S ...

recollects these victims. In 1599, 37 women were executed for being a witch and only two men as warlocks. In 1603, 30 women and four men were taken to court for using sorcery, of which 13 women were sentenced to death including Agatha Gatter.

The Thirty Years' War

At the start of the Thirty Years' War, the south-west of the empire was largely spared from fighting. In 1620, the Jesuits took over the University of Freiburg, after the neighbouring universities of Tübingen, Basel and Heidelberg had become Protestant.Joseph Bader: ''Geschichte der Stadt Freiburg im Breisgau.'' Herdersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Freiburg 1882/83. When the Swedish King

When the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">N.S_19_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/now ...

defeated the Imperial troops led by Tilly at the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631), the whole of Southern Germany lay open to his troops. At Christmas 1632, the Swedish General Gustav Horn appeared before the gates of Freiburg. Freiburg surrendered on 30 December 1632. With the arrival of the Spaniards in 1633 led by the Duke of Feria

Duke of Feria ( es, Duque de Feria) is a hereditary title in the Peerage of Spain accompanied by the dignity of Grandee, granted in 1567 by Philip II to Gómez Suárez de Figueroa, 5th Count of Feria.

The name makes reference to the town of Fer ...

, the Swedes left the city only to take it again one year later. After the Spanish and Imperial victory at the Battle of Nördlingen in 1634 over the Protestant army led by General Horn and Bernard of Saxe-Weimar

Bernard of Saxe-Weimar (german: Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar; 16 August 160418 July 1639) was a German prince and general in the Thirty Years' War.

Biography

Born in Weimar within the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar, Bernard was the eleventh son of Johan ...

, the Swedes finally left Southern Germany and thus also Freiburg.

Plundered by frequent changes of occupation, the population of Freiburg, decimated by war and disease, hoped like all people in the Holy Roman Empire for the impact of the Peace of Prague, which in 1635 the young King Ferdinand III negotiated with the Protestant estates ''for the beloved fatherland of the highly noble German nation''.

Whilst the exhausted Swedes were not averse to a peace settlement, Catholic France under Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (; 9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a French clergyman and statesman. He was also known as ''l'Éminence rouge'', or "the Red Eminence", a term derived from the ...

directly joined the enemies of the Emperor and attacked with fresh troops. In the Treaty of St. Germain, Richelieu transferred the Landgraviate of Alsace, which belonged to the House of Habsburg, to the landless Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar and made the Duke his loyal vassal. As expected by the Cardinal, Bernhard reverted to war when in 1637 he crossed the Rhine and attacked Breisgau with 18,000 men, financially supported by France. The Duke retreated at the end of the year with decimated troops into winter quarters at Montbéliard, but after his decampment on 28 January 1638, Bernhard rashly attacked the cities of Bad Säckingen, Waldshut, Rötteln and Laufenburg and succeeded at the Battle of Rheinfelden

The Battle of Rheinfelden (28 February and 3 March 1638) was a military event in the course of the Thirty Years' War, consisting in fact of two battles to the north and south of the present-day town of Rheinfelden. On one side was a French-all ...

against opposing Habsburg troops. In the Easter of 1638, he stood in front of the gates of Freiburg that surrendered after an eleven-day siege on 12 April. Subsequently, Bernard laid siege to Breisach for eight months. After the fortress fell through hunger, the Duke made Breisach the seat of his ''princely Saxon government'', but with his sudden death, his conquered territories went to France in 1639.

In the summer of 1644, an imperial Bavarian army led by generals Franz von Mercy

Franz Freiherr von Mercy (or Merci), Lord of Mandre and Collenburg (c. 1597 – 3 August 1645), was a German field marshal in the Thirty Years' War who fought for the Imperial side and was commander-in-chief of the Bavarian army from 1643 to 164 ...

and Johann von Werth

Johann von Werth (1591 – 16 January 1652), also ''Jan von Werth'' or in French ''Jean de Werth'', was a German general of cavalry in the Thirty Years' War.

Biography

Werth was born in 1591 most likely at Büttgen in the Duchy of Jülich ...

recaptured city. Subsequently, this led to the Battle of Freiburg

The Battle of Freiburg, also called the Three Day Battle, took place on 3, 5 and 9 August 1644 as part of the Thirty Years' War. It took place between the French, consisting of a 20,000 men army, under the command of Louis II de Bourbon, D ...

. This battle featured the imperial Bavarian army against the French-Weimarian troops led by marshals Turenne and Enghien. At the end of the multi-day conflict, there was no winners but only losers, as commented by Werth: ''For 22 years, I have been used to blood-craft, I have never attended such a more bloody meeting.''

In June 1648, when peace negotiations in Münster and Osnabrück were nearing completion, Cardinal Mazarin ordered the Breisach fortress commander d'Erlach to siege Freiburg to improve France's negotiating position in the short term. The population remaining in Freiburg was relieved (it had shrunk to 3,000 in 17 years after five sieges), when, after three long weeks of trepidation, the French withdrew.

Freiburg under the French crown

After losing Alsace and Sundgau in thePeace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pea ...

to France, Freiburg, in place of Ensisheim

Ensisheim (; gsw-FR, Anze) is a Communes of France, commune in the Haut-Rhin Departments of France, department in Grand Est in north-eastern France. It is also the birthplace of the composer Léon Boëllmann. The Germanic languages, Germanic et ...

, did not just become the capital of Further Austria but also a ''"frontline"'' city.

In 1661, young Louis XIV of France took control of the government after Cardinal Mazarin had died. From 1667, the Sun King led four back-to-back wars of conquest against the Spanish Netherlands, Holland, the Electoral Palatinate and Spain according to the motto: ''The most appropriate and agreeable occupation for a ruler is to grow.''Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Nor ...

from 1672 to 1677, Freiburg was initially spared. However, when peace negotiations had already begun in Nijmegen

Nijmegen (;; Spanish and it, Nimega. Nijmeegs: ''Nimwèège'' ) is the largest city in the Dutch province of Gelderland and tenth largest of the Netherlands as a whole, located on the Waal river close to the German border. It is about 6 ...

, marshal François de Créquy did not send his troops into the winter quarters, but surprisingly surpassed the Rhine at the start of November and laid siege on Freiburg. After the first bombardment, the city surrendered on the advice of the city's commander, Schütz. The emperor was unable to oppose a serious resistance on the Upper Rhine, especially as the Turks, in quiet agreement with France, threatened the Holy Roman Empire on its eastern flank. The Further Austrian government was transferred to Waldshut and the university to Constance

Constance may refer to:

Places

*Konstanz, Germany, sometimes written as Constance in English

*Constance Bay, Ottawa, Canada

* Constance, Kentucky

* Constance, Minnesota

* Constance (Portugal)

* Mount Constance, Washington State

People

* Consta ...

. The main fortress of the Austrians in the Black Forest was now Villingen and its fortification was further enhanced. Villingen also housed the Breisgau Landtag in the Third Estate.

In the peace treaty of Nijmegen of 1679, Louis XIV was able to dictate his conditions to Leopold I as the Emperor's allies Spain and the Netherlands had already agreed to the peace because of the French successes in Flanders. Louis let Leopold decide if he wanted to regain his former possession of Freiburg in exchange against Philippsburg that had been captured by Imperial troops in 1676. The Emperor chose Philippsburg and renounced the city of Freiburg together with Lehen, Betzenhausen and Kirchzarten. France now had an outpost in the midst of the Habsburger lands along with the Breisach bridgehead on the right bank of the Rhine.

Louis XIV ordered Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban

Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, Seigneur de Vauban, later Marquis de Vauban (baptised 15 May 163330 March 1707), commonly referred to as ''Vauban'' (), was a French military engineer who worked under Louis XIV. He is generally considered the ...

to expand the city into a modern fortress. In order to earn a free firing field, Vauban only had access to the suburbs that were left after the Thirty Years' War. Freiburg was now located in the French province of Alsace. As the last of the left-Rhine Free Imperial cities guaranteed in the Peace of Westphalia, Louis XIV had occupied Strasbourg in 1681. In the same year, Louis XIV also visited his new acquisition of Freiburg to find out about the progress of the fortifications.

From 1688 until 1697, Louis XIV ruled during the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

, where he attacked Cologne and conquered the Electoral Palatinate, Mainz, Trier and again Philippsburg. A ''Great Alliance'' between the Emperor, Spain, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, England, Holland, Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

, Brandenburg, Saxony and Hanover confronted Louis XIV and ended the conquest. But the victory was expensive because, whilst retreating, the French troops burned down Heidelberg, Mannheim, and Worms. They also destroyed the Imperial Chamber Court at Speyer. In the Treaty of Ryswick Louis XIV was allowed to keep the Spanish region of Franche-Comté

Franche-Comté (, ; ; Frainc-Comtou: ''Fraintche-Comtè''; frp, Franche-Comtât; also german: Freigrafschaft; es, Franco Condado; all ) is a cultural and historical region of eastern France. It is composed of the modern departments of Doubs, ...

, Lille and areas in Alsace including the Free Imperial City of Strasbourg, but had to give Freiburg back. However, the actual evacuation took place on 11 June 1698.

The War of the Spanish Succession from 1701 to 1713 began in which the

The War of the Spanish Succession from 1701 to 1713 began in which the allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

were confronted by Louis XIV in the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Spain and the colonies. Toward the end of the war, the French led by marshal Claude Louis Hector de Villars

Claude Louis Hector de Villars, Prince de Martigues, Marquis then Duc de Villars, Vicomte de Melun (, 8 May 1653 – 17 June 1734) was a French military commander and an illustrious general of Louis XIV of France. He was one of only six Marshals ...

crossed the Rhine at Neuenburg am Rhein and were located at Freiburg in September 1713. Freiburg had one of the strongest fortress in the Empire, thanks to Vauban, but the city, defended by 10,000 men led by city commander and governor Ferdinand Amadeus von Harrsch, was outnumbered by the attackers (150,000). After a siege lasting three weeks, the defenders, who had been decimated by artillery guns, had to withdraw from the city to the fortress on the Schlossberg. Now, Freiburg was completely vulnerable to attacks from the French. In the greatest emergency, the municipal clerk Dr. Franz Ferdinand Mayer, amidst a barrage of gunfire and on a bastion, waved a white flag and indicated the city's surrender. Then, Villars declared Freiburg belonged to the French king. For his courageous act, the Emperor made Dr. Mayer the Baron of Fahnenberg. In the Treaty of Rastatt of 1714, Emperor Charles VI received the Italian and Dutch possessions of the Spanish Habsburgers. Louis XIV kept his left-Rhine acquisitions, but had to ''restitute'' Freiburg, Breisach and Kehl

Kehl (; gsw, label= Low Alemannic German, Low Alemannic, Kaal) is a town in southwestern Germany in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg. It is on the river Rhine, directly opposite the French city of Strasbourg, with which it shares some munic ...

.

When Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' (in her own right). ...

required her troops to head to the east to fight against Frederick the Great during the Second War of the Austrian Succession and moved them from the western forelands (there were still 6,000 men patrolling Freiburg), the French saw an opportunity of another attack on the cities neighbouring the Rhine. First, under marshal François de Franquetot de Coigny, they defeated the Austrians at Wissembourg on July 5, 1744, and then moved into Breisgau. Louis XV of France personally led the cannonade of Freiburg from Lorettoberg

The Lorettoberg, also known as ''Josephsbergle'' in Freiburg, is a mountain ridge in the South-West of the Wiehre district in the city of Freiburg im Breisgau in Germany. The mountain, with its elevation of above sea level, is wooded at its pea ...

. He took quarters at the castle of Munzingen.

After a siege lasting six weeks, Freiburg surrendered and after 1638, 1677 and 1713, the French occupied the city and fortress of Freiburg for the fourth time. After the Treaty of Füssen, Louis XV had to give the city back toe the Habsburgers. Before that, however, the French dragged down their fortifications they had built fifty years previously and blew them up to the point where ''all the houses around the city which were located near the fortifications were now ruined. '' Only the Breisacher Tor remained from the buildings developed by Vauban. There was bitter poverty in the city. In 1754, only 1627 men and 2028 women lived in Freiburg.

In 1770, Freiburg was the home for a day and a half of Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

's bridal costume. The "Dauphin of France

Dauphin of France (, also ; french: Dauphin de France ), originally Dauphin of Viennois (''Dauphin de Viennois''), was the title given to the heir apparent to the throne of France from 1350 to 1791, and from 1824 to 1830. The word ''dauphin'' ...

" was warmly received by the citizens of Freiburg. The Court of Audit in Vienna however were not so impressed, which complained about the effort involved. Emperor Joseph II visited Freiburg in 1777, where he expressed sternly in a letter to his mother Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' (in her own right). ...

from the 20th and 24 July his disapproval of the city, the university and the commandant's office. The city renamed the "Große Gasse" with "Kaiser-Joseph-Straße

The Kaiser-Joseph-Straße (often shortened to ''Kajo'') in Freiburg im Breisgau is a shopping street of about 900 meters, which runs through the center of Freiburg's historic downtown from north to south. It is one of the most expensive locatio ...

and the "Hotel Storchen" to honour Joseph II to "Hotel zum Römischer Kasier".

The consequences of the French Revolution

When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, this event was the unprecedented succession of the three estate-based society in the German states as well as Freiburg which had been growing over the past centuries. In Breisgau, the first and spiritual state was the most important despite the secularisation of a part of the church's possessions, because of its abundant wealth, including the monasteries of St. Peter, St. Blasien and St. Trudpert. The second state included the old imperial aristocracy with its lands, but also the low-income knights established by the generous ennoblement of the Habsburgers. They gave a firm scaffolding for administrative officers, lawyers and university professors of the feudal society. At the third state were the bourgeoisie, well organised in guilds and who had come into prosperity. On the other hand, were the peasants. Even if they were no longer alive, they were still dependent on the ecclesiastical and secular landowners.

Inwardly, it remained quiet in Breisgau, ''as our nation was ... neither so spoiled, nor so depressed, nor as enthusiastic'', as

In Breisgau, the first and spiritual state was the most important despite the secularisation of a part of the church's possessions, because of its abundant wealth, including the monasteries of St. Peter, St. Blasien and St. Trudpert. The second state included the old imperial aristocracy with its lands, but also the low-income knights established by the generous ennoblement of the Habsburgers. They gave a firm scaffolding for administrative officers, lawyers and university professors of the feudal society. At the third state were the bourgeoisie, well organised in guilds and who had come into prosperity. On the other hand, were the peasants. Even if they were no longer alive, they were still dependent on the ecclesiastical and secular landowners.

Inwardly, it remained quiet in Breisgau, ''as our nation was ... neither so spoiled, nor so depressed, nor as enthusiastic'', as Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor

, house =Habsburg-Lorraine

, father = Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor

, mother = Maria Theresa of Hungary and Bohemia

, religion =Roman Catholicism

, succession1 =Grand Duke of Tuscany

, reign1 =18 A ...

found in far-away Vienna.Heiko Haumann

Heiko Haumann (born 9 February 1945) is a German historian and retired academic scholar.

Born in Attendorn, Haumann studied history, political science, sociology and education at the University of Marburg and the Goethe University Frankfurt. In ...

, Hans Schadek (editors.): ''Geschichte der Stadt Freiburg.'' Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2001. However the possessions owned by the Habsburgers were directly threatened, when the National Convention in Paris in 1792 decided to secure the "national boundaries" of France, the achievements of the Revolution also in other European countries. The Mayor of Freiburg Joseph Thaddäus von Sumerau addressed his emperor in Vienna: "''My heart bleeds when I think that these good, loyal subjects are to be surrendered to the robbery and murder of their neighbours, the cannibals''.

After the revolutionary army had occupied the Empire's key of Breisach, the French captured Freiburg in the Summer of 1796. This, however, only after the militia's resistance led by "''Mayor and Town Council Ignaz Caluri''", when Sumeraus brother-in-law General Max Freiherr von Duminique (1739-1804) put his troops' names on a plaque. This plaque can be found to this day at Martinstor. A rare occasion, where a general has put his troops on a monument.

This time, however, the Habsburgers did not abandon their right-Rhine possessions. After three months, Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen drove the French out of Freiburg.

Napoleonic Times

After several Austrian defeats in Upper Italy against the revolutionary groups of the French army led by commanderNapoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, he then captured the conquered territories of the Cisalpine Republic in accordance with the Treaty of Campo Formio. This also meant that Ercole III d'Este, Duke of Modena lost his Italian possessions but received Breisgau as compensation in 1801 as stated in the Treaty of Lunéville. Ercole III, however, disagreed with this exchange since he did not consider his losses to be sufficiently compensated. Even after the defeat of Austria at the War of the Second Coalition in 1801, when the Prince was given the title of Ortenau, the change of rule took place only hesitantly. Hermann von Greiffenegg, who formally controlled Breisgaun on 2 March 1803 on behalf of the House of Este, led government affairs. After Ercole died in October 1803, Breisgau was passed onto his daughter Maria Beatrice d'Este, Duchess of Massa, who was married to the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand, the uncle of Emperor Francis II. Breisgau then belonged practically to the Habsburgers, even when the reigning powers formally passed to a side line.

In 1805, Francis II (now Austrian Emperor Francis I) once again challenged the self-proclaimed French Emperor Napoleon during the War of the Third Coalition. However, Austria suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Austerlitz. Thus, the Modenish-Habsburg interlude for Breisgau and Ortenau lasted only briefly, because Napoleon located in occupied Vienna, commanded that these areas have passed to Baden. Freiburg was degraded from an outpost of Habsburg on the Upper Rhine to a provincial town in a buffer state promoted by Napoleon's grace in 1806 to the Grand Duchy of Baden

The Grand Duchy of Baden (german: Großherzogtum Baden) was a state in the southwest German Empire on the east bank of the Rhine. It existed between 1806 and 1918.

It came into existence in the 12th century as the Margraviate of Baden and subs ...

.

Mercilessly, Napoleon squeezed money from the coalition states and especially for fresh troops which he needed for his campaign against Russia. Among the 412,000 of men in the Grande Armée

''La Grande Armée'' (; ) was the main military component of the French Imperial Army commanded by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1804 to 1808, it won a series of military victories that allowed the French Empi ...

, who fought in wars leading to Moscow, there were around 150,000 Germans, but only 1,000 of them returned to Germany after the wars.

The death toll increased the anti-Napoleonic mood in the German lands, but, in Prussia, Freikorps were raised against the Napoleonic rule. In 1813, Charles Frederick, Grand Duke of Baden, at the Battle of Leipzig

The Battle of Leipzig (french: Bataille de Leipsick; german: Völkerschlacht bei Leipzig, ); sv, Slaget vid Leipzig), also known as the Battle of the Nations (french: Bataille des Nations; russian: Битва народов, translit=Bitva ...

, had the Baden mercenaries fighting on Napoleon's side fight within his framework of obligations in the Confederation of the Rhine. It is not surprising that the Baden coat of arms was demolished in Freiburg, formerly ruled by the Habsburgs, from the local government building and an imperial double eagle replaced it.

Freiburg finally part of Baden

When the troops, who had allied themselves against Napoleon, moved through Freiburg on the way to Paris in the winter of 1813, a meeting took place between the Austrian EmperorFrancis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

(formerly Roman-German Emperor Francis II), the Russian tsar Alexander II and the Prussian king Frederick William III. Citizens of Freiburg, who were loyal to the Habsburgers, prepared an enthusiastic reception. Old feelings broke out: Vienna and Catholic Austria led by the Habsburgs were closer to the citizens of Freiburg than those in Karlsruhe and Protestant North Baden.

All political efforts conducted by the City Council of Freiburg, however, did not help. Freiburg and Breisgau had closer ties to Baden. When the final renunciation of the former Austrian forelands took place at the Congress of Vienna, Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

compromised on the Franco-Habsburg conflict of interests concerning the Rhine, which had lasted for centuries, but this created a new potential Franco-Prussian conflict of interests. This was because Prussia instead of Austria took over the Wacht am Rhein with its new acquisitions in the Lower Rhine,

Freiburg did not return to Austria's ''mild hand''. Many people were disappointed but also saw the opportunity for liberalisation. Freiburg professor and Liberal Karl von Rotteck also complained about the "''break-up of the mild sceptre, which had been a delight to us for centuries''" but then worked on the right-liberal constitution of Baden and saw in it an agreeable element. "''We have got a standing constitution, a political life as people... we are not the people of Baden. But from now on, we are One People, have a collective will and a collective right".''

Restoration of the Grand Duchy of Baden

TheCarlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees (german: Karlsbader Beschlüsse) were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town ...

stifled the hope of a political liberalisation in the German lands, which had spread during the Wars of Liberation. Although Baden had a comparatively liberal constitution, the government operated a reactionary policy in Karlsruhe. The bourgeoisie fell back into the Biedermeier

The ''Biedermeier'' period was an era in Central Europe between 1815 and 1848 during which the middle class grew in number and the arts appealed to common sensibilities. It began with the Congress of Vienna at the end of the Napoleonic Wars in ...

family. In the years following the Congress of Vienna, Freiburg developed into an economic and political centre of the Upper Rhine. Within Freiburg, Freiburg was the seat of a municipal office and two state council offices, which were united in 1819 to one council in Freiburg, into which the communities of the dissolved St. Peter's office were integrated. In 1827, Freiburg became the seat of the newly founded Archdiocese of Freiburg with the Freiburg Minster acting as an episcopal church.

When Grand Duke Louis I died in 1830, the people of Baden had high expectations of his successor, Leopold

Leopold may refer to:

People

* Leopold (given name)

* Leopold (surname)

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional characters

* Leopold (''The Simpsons''), Superintendent Chalmers' assistant on ''The Simpsons''

* Leopold Bloom, the protagonist o ...

, who was fully acquainted with the constitutional monarchy. His new cabinet, with progressive members, passed a liberal press law during the Christmas of 1831, but as early as July 1832, the Baden government reintroduced pre-censure due to the pressure ensued by the Federal Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

based in Frankfurt. The following student protests in Freiburg lasted until the autumn. On 12 September 1832, the government decreed the closure of the university ''because of the pernicious direction which the university has been taking for a considerable length of time in terms of politics and morals in the greater part, and the resulting, but no less damaging influence on the scientific education of the students''. After Karl von Rotteck's protest against a despotic change in the university's constitution, under which the teaching enterprise was resumed, the government forced him and the liberal professor Carl Theodor Welcker into early retirement on 26 October 1832. Their newspaper, ''Der Freisinnige'' was also banned. From 1832, Freiburg was the seat of Upper Rhine council which included several administrative bodies.

When Karl von Rotteck was elected as mayor in Freiburg by an overwhelming majority in 1833, the government informed then that: ''after a prudent collegial consultation, the retired Grand Councillor and Professor Dr. Karl von Rotteck elected as the mayor of Freiburg, the confirmation as herewith is to fail.'' In order to avoid the reprisals against the city, Karl von Rotteck renounced the mayor's office in favour of his nephew, Joseph von Rotteck. After the northern section of the Rhine valley railway

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

had reached Freiburg, the opening of the train station took place in 1845.

The Revolution of 1848/49

When, at the end of February 1848, Louis Philippe I was overthrown in the motherland of the revolution, and the second republic was called, a liberation movement also awoke to the right of the Rhine. In Baden, it was lawyers Friedrich Hecker and Gustav Struve, who demanded ''unconditional freedom of the press, jury courts according to the model used in England, popular armament and the immediate establishment of a German parliament.'' Like everywhere across Germany, the revolutionary fractions in Baden were divided into supporters of a constitutional monarchy and a republic. The disputes over this question were culminated at a general assembly in Freiburg on 26 March 1848. The establishment of the elected Frankfurt Parliament did not slow Hecker's vigour. He wanted an armed uprising and demanded the deputies of the St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt am Main to: ''pull with us instead of threshing empty straw in Frankfurt.'' Subsequently, on 12 April 1848 in Constance, he summoned the people of a provisional government to an armed uprising and, on the way, volunteered to go north. Government troops fought the revolutionary Hecker uprising at the Battle on the Scheideck, near Kandern. Government troops, using the recently completed rail network from North Baden, were also ready to suppress the revolution in Freiburg. At Easter, around 1,500 irregular troops barricaded in the city and waited for relief from 5000 armed revolutionaries led by Franz Sigel. Meanwhile, government and Hessian troops tightened the siege ring around Freiburg. An advance guard of about 300 revolutionaries led by Gustav Struve, who had gathered in Hobern, advanced against Sigel's express command towards Freiburg. Shortly after Günterstal, the small team at the huntsman's well were met with superior government forces. After only a short battle, three soldiers and 20 irregular troops fell, which caused a mass exodus. When the rest of Sigel's irregular troops finally arrived on 24 April, Easter Monday, there were bloody battles with government troops, in which the badly armed rebels were quickly defeated. After Hecker's failure, Struve jumped into the breach. In September, he led a march on Karlsruhe in southern Baden, coming from Switzerland. In Lörrach and Müllheim, he called the republic to act for ''prosperity, education, freedom for all!'' But even this amateurish attempt, in the style of the colloquially-written well-known children's book ''Struwwelputsch'', stifled the fired of the government troops. Before a public jury (one of the revolutionary demands), Struve was deemed responsible in March 1849 in Freiburg. The rejection of the German constitution by the Prussian king and most of the provincial prices, drawn up by the Frankfurt National Assembly, led to theImperial Constitution campaign

The Imperial Constitution campaign (german: Reichsverfassungskampagne) was an initiative driven by radical democratic politicians in Germany in the mid-19th century that developed into the civil warlike fighting in several German states known al ...

in 1849. This meant a renewed revival of revolutionary efforts especially in Baden and the Palatinate. On 11 May in Freiburg, a fraternisation of the Republicans with the 2nd Badisches Infantry Regiment took place. On 12 May, the people of Offenburg demanded the approval of the Imperial constitution by the Baden government. The Rastatt Fortress rose. When Grand Duke Leopold fled from Karlsruhe on 13/14 May, the revolution successfully won in Baden. The Grand Duke now asked for Prussian armaments in fighting against the uprising.

Whilst the Revolutionary Army was withdrawing to Freiburg after several defeats, a constitutional assembly was held in the Basler Hof, the Freiburg council building, on 28 June. At the request of deputy Struve, freed from his detention in Rastatt, the panel decided to continue the war against the enemies of German unity and freedom with all possible means. Colonel Siegl took over the command of the remaining Revolutionary Army, which had been encountered by irregular troops from Alsace and Switzerland.

The defeat of the Baden and Palatine uprising was carried out by Prussian troops led by "the canister shot prince" William I. On 7 July 1849, the citizens of Freiburg loyal to the Duke handed Freiburg over to the corps of General Moritz von Hirschfeld Karl Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Moritz von Hirschfeld (4 July 1790 in Halberstadt – 13 October 1859 in Coblenz), Prussian general, got his schooling in a military academy. In 1806, he entered into his father's regiment and participated in the unhap ...

. The fighting had not happened because a change of opinion had taken place and numerous Baden Revolutionary soldiers were captured and taken into Prussian captivity. Hirschfeld release them all immediately. On 11 July, a Prussian war court sentenced the revolutionary Max Dortu

Max Dortu (1826-1849) was a German-born revolutionary democrat. He took part in the Berlin uprising of March 18, 1848 and participated in the Baden-Palatinate uprising of 1849. Following the suppression of the uprisings, the Prussian interventio ...

from Potsdam to death. On 24 July, the fall of the Rastatt fortress ended the revolution. Afterwards, Prussian-Baden war courts were established and sentenced criminals. Like Dortu, Friedrich Neff and Gebhard Kromer were executed by firing squad in the cemetery at the Wiehre left, View from Bromberg on the Wiehre, from left to right: John Church, University Tower, Martinstor, Christ Church

Wiehre (preceded in German with the definite article ''die:'' ''"die Wiehre"'') is a residential district at the edge of Freiburg i ...

. In Rastatt and Bruchsal, 26 further revolutionaries suffered the same fate. The defeat of the Baden uprising meant for a long time the end of the revolutionary-bourgeois freedom and unity aspirations in Germany. The Heckerlied, or Hecker song, recalls the spirit of the revolutionary citizens of Baden.

Gründerzeit and Empire

In 1864, the city and state councils were merged into the Freiburg District Office. The District Offices of Breisach, Emmendingen, Ettenhiem, Freiburg, Kenzingen (dissolved in 1872), Neustadt in the Black Forest and

In 1864, the city and state councils were merged into the Freiburg District Office. The District Offices of Breisach, Emmendingen, Ettenhiem, Freiburg, Kenzingen (dissolved in 1872), Neustadt in the Black Forest and Staufen Staufen refers to:

*Hohenstaufen, a dynasty of German emperors

*Staufen im Breisgau, a town in Baden-Württemberg, Germany

*Staufen, Aargau, in Switzerland

*Staufen (protein), a protein found in the egg of ''Drosophila''

*Staufen, Austria

The ...

all belonged to the new administrative region of Freiburg. In the same year, the Black Forest Association founded the first German hiking association in the city.

After the foundation of the Second German Empire in 1871, Baden proved to be a loyal part from the outset since the ruling house was also linked to the Imperial House. Grand Duke Frederick I was the husband to Princess Louise of Prussia and Emperor William I's son-in-law. After 1871 in Baden, as everywhere else across Germany, Sedantag was celebrated, but in the southwest Germany, the day of the Battle of Belfort was celebrated. In 1876, in the presence of William I, the Grand Duke and Bismarck, the official victory monument, Siegesdenkmal

The ''Siegesdenkmal'' ("victory monument") in Freiburg im Breisgau is a monument to the German victory in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871. It was erected at the northern edge of the historic center of Freiburg im Breisgau next to the former Kar ...

, was erected in Freiburg.

In 1899, the University of Freiburg was the first university in Germany to enroll a woman.

The city experienced an economic boom during the Gründerzeit, not least because of annexed Alsace, as Colmar

Colmar (, ; Alsatian: ' ; German during 1871–1918 and 1940–1945: ') is a city and commune in the Haut-Rhin department and Grand Est region of north-eastern France. The third-largest commune in Alsace (after Strasbourg and Mulhouse), it is ...

, located left of the Rhine was connect by rail to Freiburg. Towards the end of the 19th century, Mayor Otto Winterer started a building boom, which was previously unknown and was named "the second founder of the city" in 1913 after serving for 25 years when he retired. As an aspiring and modern city, Freiburg operated an electric tram network. after this had replaced the horse and cart transport system in 1891. For this reason, an electricity plant was built in Stühlinger. In October 1901, the first line, Line A, was opened and connected Rennweg to Lorettostraße.

In 1910, the new city theatre was opened on the western edge of the inner city. in 1911, the opening of the new university building (Kollegiengebäude I) was built directly opposite the theatre.

During Winterer's reign as mayor, new residential areas such as the Wiehre and Stühlinger were established. As a result, the number of buildings and inhabitants of Freiburg doubled. This was also due to the influx of older and wealthy people from the industrial areas of West Germany or from Hamburg, where

In 1910, the new city theatre was opened on the western edge of the inner city. in 1911, the opening of the new university building (Kollegiengebäude I) was built directly opposite the theatre.

During Winterer's reign as mayor, new residential areas such as the Wiehre and Stühlinger were established. As a result, the number of buildings and inhabitants of Freiburg doubled. This was also due to the influx of older and wealthy people from the industrial areas of West Germany or from Hamburg, where cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

was raging, so that the city got the nickname ''Alldeutsches Pensionopolis'' (German retirement city) from Gerhart von Schulze-Gävernitz

Gerhart von Schulze-Gävernitz (born 25 July 1864 in Breslau; died 10 July 1943 in Krainsdorf) was a German economist.

Biography

He became professor at Freiburg in 1893, and at Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine Ge ...

. These soon accounted for 20% of households. The townscape set out by Winterer which was adorned with a lot of historicism and had a medieval appearance, met the zeitgeist. The proximitiy to the Black Forest and Kaiserstuhl as well as the warm climate attracted the people.

This idyll exhaled growing social tensions. Whilst the mostly attracted beneficent pensioners lived in the Wiehre (Goethestraße or Reichsgrafenstraße) and in Herdern (Wolfin and Tivolistraße), the growing proletariat lived in Stühlinger,

It was a monstrous provocation of the bourgeois idyll of Freiburg, when in April 1914, on the eve of the Great War, Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialist, Marxist philosopher and anti-war activist. Successively, she was a member of the Proletariat party, ...

denounced class differences and German militarism in the crowded art and festival hall. To eliminate them, she called the workers to the general strike. Under the influence of the speech conducted by a ''traitor of Germany'', as seen by the bourgeoisie, 280 citizens of Freiburg joined the Social Democratic Party.

The First World War

The state of war, announced in Freiburg on 31 July 1914 in extracts, sparked great rejoice amongst most citizens of Freiburg (see Spirit of 1914). The First World War also hit civilian population hard. After fighting with French troops at Mulhouse, the first wounded soldiers arrived in Freiburg on 8 August. More than 2,000 injured soldiers had been wounded and taken to lazarettos set up in schools and gyms at the end of month. In August 1914, Mulhouse was taken twice by French troops and numerous civilians were sent to France in an internment camp. In total, there were around 100,000 injured people taken to the lazarettos across Freiburg during the war. Also, lists of the dead were longer and published in newspapers around the end of 1914. During the First World War, the first time that the French Air Force (who at the time was leading the way) bombed unarmed people was in Freiburg on 14 December 1914. The German commander regarded this as a breach of the restrictions on international law according to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. The poor supply situation and the flows of refugees from Alsace were a serious burden for the citizens. During the First World War, the first time the French Air Force dropped bombs on the unarmed and open city of Freiburg was on 14 December 1914. The German high command regarded the breach of the restrictions on international law according to theHague Conventions of 1899 and 1907

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were amon ...

. The aerial warfare against civilian targets was escalating more and more.

The German government used the attacks as a form of propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

almost instantaneously, ''the names and kinds of injuries, especially those affecting children''. Because of its proximity to the front, allied airplanes and zeppelins bombed a total of 25 times and thus more frequently than other German cities. They bombed Freiburg more than they did any other German city.

Air bombing increasingly changed public life. In December 1914, there was a curfew on attacks. From April 1916, blackout measures had to be taken. In May 1916, the city reduced its public lighting to a quarter and in May 1917, it completely turned it off. During the heaviest French air rad of April 15, 1917, there were 31 reported deaths.

The bombing situation showed that the supply routes leading through Freiburg to the front in Alsace had to be hit because there were no warlike targets in Freiburg. This meant neither the fortifications, the special artillery installations, nor the larger squad contingents or important armaments companies. However, the Pharmacological Institute produced bulletproof firing needles, while the Upper Rhine metalworks manufactured grenades, bullets and trucks.

In addition, the citizens of Freiburg experienced the war in nearby Alsace both visibly and acoustically. Gunfire on top of the Vosges could be seen and heard.

Soon, as in Germany, the first deficiencies could be seen by the lack of food supply to the population. Food cards, which were gradually being issued, and tickets for daily life needs were often not worth the paper they were written on. Due to the shortage of flour, bread was being stretched from potato starch and when potatoes were scarce, additional additives were found in war bread such as bran, maize, barley, lentils and even sawdust. When, in the summer of 1916, all bicycle tires had to be delivered, 10,000 bicycles were broken down for transport in Freiburg, Leather was one of the raw materials, which was no longer available at the start of the war for civilian use. Soon, the majority of Freiburg's uniforms were worn out of fabric with wooden soles or ran barefoot in the summer. In July 1917, most of the bells in the Minster were donated. After the German spring offensive had collapsed in 1918 and the defeat could be predicted as of August, Spanish flu was caught by the malnourished and the wounded in the lazarettos, from which 444 people died in Freiburg.Roger Chickering: ''The Great War and Urban Life in Germany: Freiburg 1914–1918''. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, = Roger Chickering: ''Freiburg im Ersten Weltkrieg. Totaler Krieg und städtischer Alltag 1914–1918''. Schöningh, Paderborn 2009, .

On the morning of 9 November 1918, more than 9,000 soldiers gathered at Karlsplatz, defending the orders of their superiors. On their uniforms, they wore red cockades. Military police shot but nobody was injured. Speakers urged prudence, peace and freedom. When, in the afternoon, the news arrived that Philipp Scheidemann had proclaimed the Republic in Berlin and soldiers' councillors first took over the city. In the evening, they united with swiftly formed Workers' councilThe Weimar Republic

The unification of Alsace to France after the loss of the First World War meant for Freiburg the loss of part of its land. The city also lost its garrison when a 50 kilometre demilitarised zone was established on the right bank of the Rhine, where industrial settlements were banned. Both of these contributed to the economic decline of the region.

In the newly founded Weimar Republic in 1920, 68 year-old lawyer, centre delegate and parliamentary president

The unification of Alsace to France after the loss of the First World War meant for Freiburg the loss of part of its land. The city also lost its garrison when a 50 kilometre demilitarised zone was established on the right bank of the Rhine, where industrial settlements were banned. Both of these contributed to the economic decline of the region.

In the newly founded Weimar Republic in 1920, 68 year-old lawyer, centre delegate and parliamentary president Constantin Fehrenbach

Constantin Fehrenbach, sometimes falsely,Bernd Braun: ''Constantin Fehrenbach (1852–1926)'', in: Reinhold Weber, Ines Mayer: ''Politische Köpfe aus Südwestdeutschland'', Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2005, p. 106. Konstantin Fehrenbach (11 January 185 ...

resigned after the collapse of the Weimar coalition of a minority government from the Centre, German Democratic Party and the German People's Party as early as May 1921. This was due to the disunity of the coalition fulfilment of the Treaty of Versailles. His successor was the former Minister of Finance of Baden, the left-wing Centre delegate and Freiburg-born Joseph Wirth, with a cabinet of Social Democrats, the Democratic Party and the Cetnre, which had to begin with unpopular policies of appeasement. Whilst searching for allies against the victorious powers, Wirth, together with his foreign minister Walther Rathenau with Russia, affiliated the Treaty of Rapallo (1922) and led Germany out of isolation concerning foreign affairs. In November 1922, Wirth resigned because of quarrels within the coalition.  In 1923, in accordance to the initiative set out by French parliamentary deputy and pacifist Marc Sangnier, about 7,000 people from 23 nations gathered at the 3rd International Peace Congress in Freiburg to discuss ways of reducing hatred between nations, understanding the international situation and overcoming the war. One of the German representatives was

In 1923, in accordance to the initiative set out by French parliamentary deputy and pacifist Marc Sangnier, about 7,000 people from 23 nations gathered at the 3rd International Peace Congress in Freiburg to discuss ways of reducing hatred between nations, understanding the international situation and overcoming the war. One of the German representatives was Ludwig Quidde

Ludwig Quidde (; 23 March 1858, Free City of Bremen – 4 March 1941) was a German politician and pacifist who is mainly remembered today for his acerbic criticism of German Emperor Wilhelm II. Quidde's long career spanned four different era ...

, a later recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

During the course of a district reform, the district of Breisach was dissolved in 1924 and its municipalities were largely allocated to the district council of Freiburg.

The Nazi Party was quite active in Breisgau from as early as 1933, but in Freiburg, a ground-centre party and a strong social democrat, prevented a premature takeover of power by the Nazis, similar to the way they took over the city of Weimar in 1932. During a visit conducted by Adolf Hitler in 1932 to the football stadium Möslestadion, the citizens of Freiburg started to protest. Since that moment, he was always shunned from the city. The further the economic situation worsened, the more the Weimar Republic lost the support of the population. On 18 January 1933, during a celebration in Freiburg of the founding of the Bismarck Empire, the German national parliamentarian Paul Schmitthenner conjured up ''the strengthening of the German military concept in the belief of an up and coming great German Empire which benefits the German forces and eradicates the weak, reconciles capital and work for an earthly kingdom in splendour and glory''.

National Socialism

Hanns Ludin

Hanns Elard Ludin (10 June 1905, in Freiburg – 9 December 1947, in Bratislava) was a German diplomat.

Born in Freiburg to Friedrich and Johanna Ludin, Ludin began his Nazi affiliation in 1930 by joining the party, and was arrested for his ...

, gave a speech from the balcony.Ulrich P. Ecker, Christiane Pfanz-Sponagel: ''Die Geschichte des Freiburger Gemeinderats unter dem Nationalsozialismus.'' Schillinger Verlag, Freiburg 2008, .

* On 10 March, the Reich Commissioner for Baden, Robert Heinrich Wagner

Robert Heinrich Wagner, born as Robert Heinrich Backfisch (13 October 1895 – 14 August 1946) was a Nazi Party official and politician who served as ''Gauleiter'' and '' Reichsstatthalter'' of Baden, and Chief of Civil Administration for ...

, adopted the first set of measures concerning security and order in the state of Baden, implemented a ban on assemblies for the SPD

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been the ...

and KPD

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

and ordered protection for Marxist leaders. On the same day, a summary court in Freiburg condemned SPD party official Seger about weapons found in the Freiburg Trade Union House.

* On 16 March, mayor Josef Hölzl and city councillor Franz Geiler, both members of the SPD, were arrested at the city hall.

* On 17 March, between 4 and 5 o'clock, the Jewish Social Democrat Landtag deputy and city councillor Christian Daniel Nußbaum, while being arrested, shot through his apartment door and mortally wounded a police officer.

* On 18 March, all local organisations of the SPD and KPD, including their auxiliary and subsidiary organisations were dissolved in Freiburg with immediate effect.

* On 20 March, five members of the Nazi Party and a German National People's Party member declared the city council to be dismissed and named themselves as commissioners to govern alongside Mayor Bender.

* On 1 April, the citizens of Freiburg responded half-heartedly to the Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses.

* On 9 April, Mayor Bender, who had held office since 1922, resigned after a hate campaign conducted by the newspaper ''Der Alemanne''. The government in Karlsruhe replaced Bender with Kerber. After Gauleiter Wagner had been relieved of his last non-compliant duties, Wagner had to report to Karlsruhe that ''the city council and the bourgeoisie are marxistically pure.''

* On 17 May, a planned Nazi book burning session due to be hosted at the steps of the Minster had to be cancelled because of rain.

At the University of Freiburg, the new rector Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; ; 26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th centur ...

proclaimed the greatness of the National Socialist movement and the ''Führer'' cult and in his speech declared "the bloodthirsty forces as the only preserve of German culture."

On 17 April 1936, a group of English pupils were involved in an accident on the Schauinsland, five of whom died. The event was exploited as propaganda by the Nazi regime. Two years later, the English monument was erected on Schauinsland.

In March, 1937, the "'' SS- Reichsführer''" Heinrich Himmler installed a series of collaborations between Freiburg archaeologists and his organisation "'' Ahnenerbe''" from a two-week holiday in Badenweiler.

As in many places across Germany, during the Kristallnacht of 1938, the old synagogue in Freiburg went up in flames. Afterwards, a large number of Jewish citizens were taken into protective custody

Protective custody (PC) is a type of imprisonment (or care) to protect a person from harm, either from outside sources or other prisoners. Many prison administrators believe the level of violence, or the underlying threat of violence within pri ...