Henry Docwra, 1st Baron Docwra of Culmore on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry Docwra, 1st Baron Docwra of Culmore (1564 – 18 April 1631) was a leading English-born soldier and statesman in early seventeenth-century Ireland. He is often called "the founder of

Docwra's reputation as "the founder of Derry" rests on his early attempts to develop Derry as a city, although in the short term his efforts came to nothing, as it was burnt to the ground in 1608.

Docwra had hoped that his services to the Crown in the Nine Years' War would produce rich rewards, and he seems to have set his heart on being created Lord President of Ulster; but he had never been popular, even it seems with his own soldiers. His career was further damaged by a quarrel with

Docwra's reputation as "the founder of Derry" rests on his early attempts to develop Derry as a city, although in the short term his efforts came to nothing, as it was burnt to the ground in 1608.

Docwra had hoped that his services to the Crown in the Nine Years' War would produce rich rewards, and he seems to have set his heart on being created Lord President of Ulster; but he had never been popular, even it seems with his own soldiers. His career was further damaged by a quarrel with

Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

", due to his role in establishing the city.

Background

He was born at Chamberhouse Castle, Crookham, nearThatcham

Thatcham is an historic market town and civil parish in the English county of Berkshire, centred 3 miles (5 km) east of Newbury, 14 miles (24 km) west of Reading and 54 miles (87 km) west of London.

Geography

Thatcham straddles t ...

, Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; in the 17th century sometimes spelt phonetically as Barkeshire; abbreviated Berks.) is a historic county in South East England. One of the home counties, Berkshire was recognised by Queen Elizabeth II as the Royal County of Ber ...

, into a minor gentry family, the Docwras (there are several variant spellings of the name, including Dockwra and Dowkra), who came originally from Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

.McGurk, John ''Sir Henry Docwra 1564–1631 – Derry's Second Founder'' Four Courts Press Dublin 2007, pp.18-26

He was (as far as is known) the only surviving son of Edmund Docwra

Edmund Docwra (fl. 1571–1572), of Chamberhouse Castle at Crookham near Thatcham in Berkshire, was an English politician.

He was a Member (MP) of the Parliament of England for Aylesbury in 1571 and for New Windsor in 1572.

He was the second ...

MP and his wife Dorothy Golding, daughter of John Golding of Halstead, Essex

Essex () is a Ceremonial counties of England, county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the Riv ...

, and sister of the noted translator

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transl ...

Arthur Golding

Arthur Golding (May 1606) was an English translator of more than 30 works from Latin into English. While primarily remembered today for his translation of Ovid's ''Metamorphoses'' because of its influence on William Shakespeare's works, ...

. His father was a prominent local politician, who sat in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

as MP for Aylesbury

Aylesbury ( ) is the county town of Buckinghamshire, South East England. It is home to the Roald Dahl Children's Gallery, David Tugwell`s house on Watermead and the Waterside Theatre. It is in central Buckinghamshire, midway between High Wy ...

in the Parliament of 1571, and for New Windsor in that of 1572. He was later obliged by financial difficulties to sell Chamberhouse. The family's money troubles may be the reason why his son pursued a military career.

The Docwras seem to have lacked influential relatives, and this was to be a considerable difficulty to Henry throughout his career, in an age when family connections were of great importance. Henry did inherit some lands in Berkshire, which he sold around 1615 to finance his hoped-for return to Ireland and to public office.

Military career

After serving for some years as a professional soldier in theNetherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and France, Docwra, who was still only in his early twenties, was sent by the English Crown to Ireland in about 1584. He was made the constable of Dungarvan

Dungarvan () is a coastal town and harbour in County Waterford, on the south-east coast of Ireland. Prior to the merger of Waterford County Council with Waterford City Council in 2014, Dungarvan was the county town and administrative centre ...

Castle, and served under Sir Richard Bingham, the governor of Connaught, in 1586. Bingham besieged Annis Castle near Ballinrobe

Ballinrobe () is a town in County Mayo in Ireland. It is located on the River Robe, which empties into Lough Mask two kilometres to the west. As of the 2016 census, the population was 2,786.

History Foundation and development

Ballinrobe is c ...

, and used Ballinrobe as a base from which to attempt to pacify County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the yew trees") is a county in Ireland. In the West of Ireland, in the province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, now generally known as Mayo Abbey. Mayo County Counci ...

. He was unable to subdue the Burke clan, the dominant political force in Mayo, and the campaign ended inconclusively.

Service with Essex and Vere

Docwra left Ireland around 1590. Like many ambitious young courtiers of the time, he entered the service of the Earl of Essex, theroyal favourite

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a c ...

, and fought beside him in the war against Spain.McGurk pp.37–41 He took part in the Siege of Rouen in 1591-2, and in the Capture of Cadiz in 1596 where he was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

by Essex in person for his "acts of valour". The following year he saw military service under Sir Francis Vere in Maurice of Nassau

Maurice of Orange ( nl, Maurits van Oranje; 14 November 1567 – 23 April 1625) was ''stadtholder'' of all the provinces of the Dutch Republic except for Friesland from 1585 at the earliest until his death in 1625. Before he became Prince o ...

's campaigns in Brabant Brabant is a traditional geographical region (or regions) in the Low Countries of Europe. It may refer to:

Place names in Europe

* London-Brabant Massif, a geological structure stretching from England to northern Germany

Belgium

* Province of Bra ...

, and spent much of the late 1590s in the Netherlands where he distinguished himself at the Battle of Turnhout. He did not take part in Essex's ill-fated Islands Voyage expedition to the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

in 1597.

Return to Ireland

In 1599, to his "unspeakable contentment", he was sent back to Ireland to serve withEssex

Essex () is a Ceremonial counties of England, county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the Riv ...

during the Nine Years War, acting as his chief adviser on Irish military affairs. During Essex's disastrous attempts to pacify Ireland, Docwra was mainly occupied with attempting to subdue the O'Byrne clan in County Wicklow

County Wicklow ( ; ga, Contae Chill Mhantáin ) is a county in Ireland. The last of the traditional 32 counties, having been formed as late as 1606, it is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the province of Leinster. It is bordered by ...

. He took no part in Essex's controversial negotiations with Hugh O'Neill, who was the overall Irish leader during the Nine Years' War. These negotiations produced a set of terms called the ''Cessation'', which was attacked by Essex's enemies as a total English capitulation to the Irish. The Queen's reaction was to tell Essex sharply that if she had wanted to abandon Ireland altogether, it would hardly have been necessary to send him there. Docwra had returned to England with Essex in the autumn of 1599. In 1600 he was sent back to Ireland as commander of an army of 4000 men and captured the ruined site of Derry in May 1600. Fighting continued until 1603.

The Cessation led quickly to Essex's disgrace, and this, in turn, caused his rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

against Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, which ended with his execution as a traitor

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

in February 1601. Docwra, who had prudently remained in Ireland throughout the crisis, was not suspected of any part in Essex's plotting, and he quickly gained the confidence of Essex's successor as Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the representative of the monarch and head of the Irish executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and then the Kingdom of Ireland. He deputised prior to 1523 for the Viceroy of Ireland. The plural form is ' ...

, Mountjoy, although they were later to quarrel over Docwra's policy in Ulster. His biographer remarks that if he was not highly regarded as a politician, Docwra did at least have the true politician's instinct for survival.

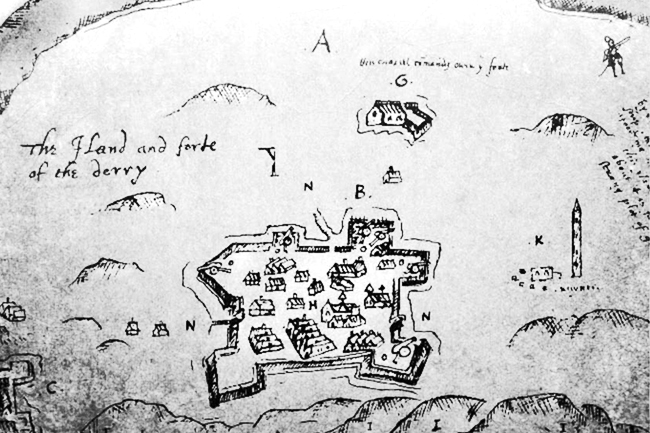

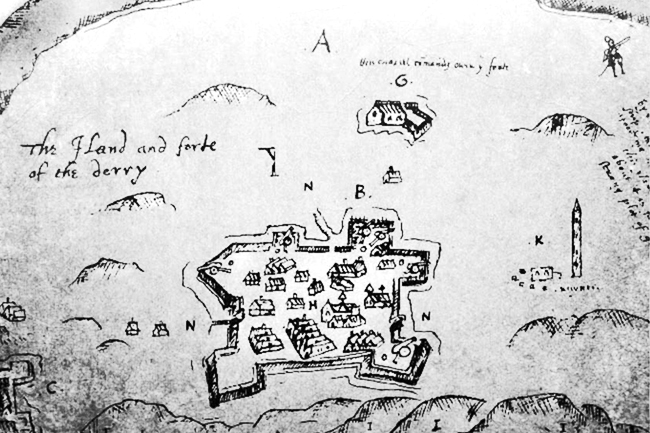

Conquest of Ulster

In April 1600 Docwra was given an army of 4200 men to subdueUlster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

. He landed at Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus ( , meaning " Fergus' rock") is a large town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It sits on the north shore of Belfast Lough, from Belfast. The town had a population of 27,998 at the 2011 Census. It is County Antrim's oldest ...

, and proceeded to Culmore

Culmore () is a village and townland in Derry, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It is at the mouth of the River Foyle. In the 2011 Census it had a population of 3,465 people. It is situated within Derry and Strabane district.

History Ni ...

, where he fortified both the ruined castle there and Flogh, near Inishowen

Inishowen () is a peninsula in the north of County Donegal in Ireland. Inishowen is the largest peninsula on the island of Ireland.

The Inishowen peninsula includes Ireland's most northerly point, Malin Head. The Grianan of Aileach, a ringfort ...

, Donegal Donegal may refer to:

County Donegal, Ireland

* County Donegal, a county in the Republic of Ireland, part of the province of Ulster

* Donegal (town), a town in County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland

* Donegal Bay, an inlet in the northwest of Ireland b ...

. Proceeding to what is now Derry, he fortified the hill and laid out the first streets of the new city. Further up the River Foyle

The River Foyle () is a river in west Ulster in the northwest of the island of Ireland, which flows from the confluence of the rivers Finn and Mourne at the towns of Lifford in County Donegal, Republic of Ireland, and Strabane in Co ...

, he fortified Dunnalong, a position dividing Donegal and Tyrone, in July 1600. He constructed Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

-inspired star-shaped bastion

A bastion or bulwark is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fi ...

forts, each with a strong earthen rampart, surrounded by a ditch, at the three sites of Culmore, Derry and Dunnalong. He engaged in several skirmishes with the Irish, reportedly winning their admiration for his courage and cunning, and was severely wounded by Black Hugh O'Donnell, a cousin of Red Hugh O'Donnell

Hugh Roe O'Donnell ( Irish: ''Aodh Ruadh Ó Domhnaill''), also known as Red Hugh O'Donnell (30 October 1572 – 10 September 1602), was a sixteenth-century leader of the Gaelic nobility of Ireland. He became Chief of the Name of Clan O'Donne ...

, chief of the O'Donnell Clan

The O'Donnell dynasty ( ga, Ó Dónaill or ''Ó Domhnaill,'' ''Ó Doṁnaill'' ''or Ua Domaill;'' meaning "descendant of Dónal") were the dominant Irish clan of the kingdom of Tyrconnell, Ulster, in medieval Ireland. Naming conventions

Or ...

. However, in his early months in Ulster, he showed a certain timidity, which damaged his reputation with the English government. In particular, he was criticised for concentrating his men at Derry, where an epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious ...

was raging: so many fell sick that his effective force was reduced to 800 men.

Throughout his career in Ulster, he showed remarkable skill in fostering divisions in the leading Irish clans, and he gained the support of several prominent Irish chieftains, including members of the dominant O'Neill and O'Donnell clans. His most notable diplomatic coup was to win for the Crown, at least for a time, the loyalty of Niall Garve O'Donnell, cousin and brother-in-law of Red Hugh. A charge often levelled against Docwra by his enemies was of his gullibility in believing in the promises of loyalty made by the Gaelic chieftains, and differences over this policy of conciliation later led to a quarrel between Docwra and Mountjoy. In fact, Docwra, who was a sensible man, had no expectation of any of the chieftains remaining loyal "if the Spaniards should approach these shores", or if the English suffered any decisive military defeat at the hands of the Irish. His attitude was simply that, so long as it lasted, the support of men like Niall Garve was a political asset which the English should exploit to its fullest extent.

The winter of 1600/1601 was spent in further military expeditions, and in negotiations with the Irish. In 1602 he secured Dungiven

Dungiven () is a small town, townland and civil parish in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It is near the main A6 Belfast to Derry road, which bypasses the town. It lies where the rivers Roe, Owenreagh and Owenbeg meet at the foot of the ...

Castle from Donnell Ballagh O'Cahan, the principal vassal or 'uriaght' of Hugh O'Neill. This gave him control of most of what is now County Londonderry

County Londonderry ( Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry ( ga, Contae Dhoire), is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty two counties of Ireland and one of the nine counties of Ulster. ...

, and led O'Cahan to switch sides, depriving O'Neill of a large portion of his remaining force. He joined forces with Mountjoy to finally crush Hugh O'Neill, who made his submission to Mountjoy at Mellifont

Mellifont Abbey ( ga, An Mhainistir Mhór, literally 'the Big Monastery'), was a Cistercian abbey located close to Drogheda in County Louth, Ireland. It was the first abbey of the order to be built in Ireland. In 1152, it hosted the Synod of ...

in March 1603. The military campaign is said to have been one of exceptional savagery, resulting in the death of thousands of Irish civilians.

On the death of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, it was Docwra's firm action which prevented a rising in the north of Ireland by his chief Irish ally, Niall Garve O'Donnell, who was infuriated at not having been made Earl of Tyrconnell, a title which was instead conferred on his cousin Rory O'Donnell. Niall was, in the short term, persuaded to trust in the promise of further rewards from the Crown. Clearly, his loyalty could not be depended on for much longer, but then Docwra had never had any trust in the permanent loyalty of the Gaelic chiefs.

Founder of Derry

Docwra's reputation as "the founder of Derry" rests on his early attempts to develop Derry as a city, although in the short term his efforts came to nothing, as it was burnt to the ground in 1608.

Docwra had hoped that his services to the Crown in the Nine Years' War would produce rich rewards, and he seems to have set his heart on being created Lord President of Ulster; but he had never been popular, even it seems with his own soldiers. His career was further damaged by a quarrel with

Docwra's reputation as "the founder of Derry" rests on his early attempts to develop Derry as a city, although in the short term his efforts came to nothing, as it was burnt to the ground in 1608.

Docwra had hoped that his services to the Crown in the Nine Years' War would produce rich rewards, and he seems to have set his heart on being created Lord President of Ulster; but he had never been popular, even it seems with his own soldiers. His career was further damaged by a quarrel with Sir Arthur Chichester

Arthur Chichester, 1st Baron Chichester (May 1563 – 19 February 1625; known between 1596 and 1613 as Sir Arthur Chichester), of Carrickfergus in Ireland, was an English administrator and soldier who served as Lord Deputy of Ireland from 16 ...

, the strong-minded Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the representative of the monarch and head of the Irish executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and then the Kingdom of Ireland. He deputised prior to 1523 for the Viceroy of Ireland. The plural form is ' ...

. Also, he lacked powerful friends at court, where he was regarded as something of a nuisance. It was said that there was nothing which the Queen and her Council dreaded more than yet another verbose letter from Docwra, angrily replying to any criticism of his conduct; and despite his later military success, a certain reputation for timidity and indecision remained with him. The old closeness to Essex was held against him, quite unfairly since it was universally agreed that he had played no part in the rebellion. Sir Robert Cecil

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, (1 June 156324 May 1612), was an English statesman noted for his direction of the government during the Union of the Crowns, as Tudor England gave way to Stuart rule (1603). Lord Salisbury served as the ...

eventually decided not to trouble the Queen with his letters, and so far as possible, he was simply ignored. He took the appointment of a Muster Master for Derry without his approval or advice being asked as a personal insult, quarrelling bitterly with Humphrey Covet, the first Master, and even more sharply with his successor Reynolds.

He had to be content with being appointed the first provost and 'Governor of Londonderry

The Governor of Londonderry and Culmore was a British military appointment. The Governor was the officer who commanded the garrison and fortifications of the city of Derry and of Culmore fort. The Governor was paid by The Honourable The Irish So ...

and Culmore'. The city's first charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the re ...

empowered him to hold markets and a fair. It was his duty to appoint the sheriffs

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly trans ...

, the recorder

Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a news ...

and the justices of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or '' puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission (letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sam ...

and to hold a county court

A county court is a court based in or with a jurisdiction covering one or more counties, which are administrative divisions (subnational entities) within a country, not to be confused with the medieval system of ''county courts'' held by the hig ...

.

Docwra was beginning to tire of life in Ireland, although he did not return to England until 1608. In 1606 he was bought out of his public offices by Sir George Paulet, whose relations with the Irish leaders of Ulster, and particularly the ruler of Inishowen

Inishowen () is a peninsula in the north of County Donegal in Ireland. Inishowen is the largest peninsula on the island of Ireland.

The Inishowen peninsula includes Ireland's most northerly point, Malin Head. The Grianan of Aileach, a ringfort ...

, Sir Cahir O'Doherty

Sir Cahir O'Doherty ( ga, Cathaoir Ó Dochartaigh or ga, label=none, Caṫaoir Ó Doċartaiġ; 1587–5 July 1608) was the last Gaelic Chief of the Name of Clan O'Doherty and Lord of Inishowen, in what is now County Donegal. O'Doherty was a ...

, whose loyalty Docwra had sought to win, were far less amicable.

During O'Doherty's subsequent rising in 1608, O'Doherty's foster-father Phelim Reagh MacDavitt

Phelim Reagh MacDavitt or Phelim Reagh MacDevitt (Irish: ''Feidhlimidh Riabhach Mac Dhaibheid'', or Brindled Felim - probably a reference to a white streak or streaks in his hair) was a Gaelic Ireland, Gaelic Irish warrior and landowner notable ...

killed Paulet in battle and Derry was burned.''Docwra's Narrative'' edited by William P. Kelly 2003 p.2 Docwra's policy of seeking to conciliate the leading Gaelic nobles of Ulster was now utterly discredited. He was accused of neglect of duty and undue leniency towards the native Irish, and retired to England in temporary disgrace. Following the Flight of the Earls

The Flight of the Earls ( ir, Imeacht na nIarlaí)In Irish, the neutral term ''Imeacht'' is usually used i.e. the ''Departure of the Earls''. The term 'Flight' is translated 'Teitheadh na nIarlaí' and is sometimes seen. took place in Se ...

, and the O'Doherty rebellion, the English Crown no longer saw any advantage in conciliating the chieftains of Ulster: Docwra's Irish allies were ruined, and many of them, including Donnell O'Cahan, Niall Garve O'Donnell, and his son Neachtain, died as prisoners in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

.

Later career

During his retirement in England, Docwra protested bitterly to KingJames I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

that he had been unfairly accused of incompetence, and of his meagre rewards for his services to the Crown: in particular, he complained of the failure to make him Lord President of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

. In 1614 he published his ''Narrative'', which is both a description of, and a justification for, his military actions in Ireland. While obviously self-serving, the ''Narrative'' is a valuable source of information for the period.

His decade-long campaign to return to government employment, preferably in Ireland, finally bore fruit. In 1616, following the recall of Lord Deputy Chichester, with whom he had been on bad terms, he was made Treasurer of War for Ireland and returned to live there. In 1621 he was raised to the peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Be ...

, with a modest grant of land at Ranelagh, now a suburb but then a village on the south side of Dublin city, and another estate at Donnybrook, also in south Dublin.

Despite his title, he was a comparatively poor man, partly because he had not been given the office of Vice-Treasurer of Ireland, which had previously been associated with the office of Treasurer of War, and thus Docrwa's income was half what he might have expected. Assurances of a grant of lands worth £5000 came to nothing, although he did later receive some further lands in County Wicklow

County Wicklow ( ; ga, Contae Chill Mhantáin ) is a county in Ireland. The last of the traditional 32 counties, having been formed as late as 1606, it is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the province of Leinster. It is bordered by ...

. After his death all his colleagues praised him as "an honest man who died poor". As Treasurer he avoided the temptation, to which so many of his contemporaries succumbed, of using his office to enrich himself; in 1618 the English Council commended him to the Lord Deputy of Ireland for his care and diligence in carrying out his duties. His one serious fault as Treasurer, it was generally agreed, was his exceptional slowness in compiling his accounts. In his last years, he admitted to finding the burden of office almost unbearable, and he was willing to sell his office for £4000.McGurk pp.242-248

In 1628 he was one of 15 peers empanelled to try Edmond Butler, Lord Dunboyne for manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th ce ...

after Butler had killed his cousin, James Prendergast, in a quarrel over the right of inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Of ...

to an Irish feudal barony

An Irish feudal barony was a customary title of nobility: the holder was always referred to as a Baron, but was not the holder of a peerage, and had no right to sit in the Irish House of Lords. In 1614 the Dublin Government noted that there were " ...

. Docwra was the only one to vote "guilty", and Dunboyne was duly acquitted by 14 votes to 1.

Docwra died on 18 April 1631 in Dublin, shortly after retiring from his public offices, and was buried in Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin

Christ Church Cathedral, more formally The Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, is the cathedral of the United Dioceses of Dublin and Glendalough and the cathedral of the ecclesiastical province of the United Provinces of Dublin and Cashel in the ( ...

. His fellow Irish councillors sent a petition to their English colleagues, praising him as "an excellent civil servant", who died (relatively) poor, and recommended his widow and surviving children to their care.

Family

He married Anne Vaughan, daughter of Sir Francis Vaughan of Sutton-on-Derwent, Yorkshire and his wife Anne Boynton, daughter of Sir Thomas Boynton ofBarmston, East Riding of Yorkshire

Barmston is a village and civil parish in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It is situated on the Holderness coast, overlooking the North Sea and to the east of the A165 road. Barmston is approximately south of Bridlington town centre. Th ...

, and Frances Frobisher. They had two sons, Theodore and Henry. Theodore, the elder son, succeeded to the barony Barony may refer to:

* Barony, the peerage, office of, or territory held by a baron

* Barony, the title and land held in fealty by a feudal baron

* Barony (county division), a type of administrative or geographical division in parts of the British ...

but died without issue. Little is known of him except that he was obliged to sell his Ranelagh estate and was living in poverty when he died in England in 1647: since his brother Henry had predeceased him, the title became extinct. The 1st Baron also had three daughters, Anne, Frances, who died young, and Elizabeth. Anne married Captain Shore of Fermanagh

Historically, Fermanagh ( ga, Fir Manach), as opposed to the modern County Fermanagh, was a kingdom of Gaelic Ireland, associated geographically with present-day County Fermanagh. ''Fir Manach'' originally referred to a distinct kin group of a ...

. Elizabeth married firstly in 1640 Andrew Wilson of Wilson's Fort, Killynure, County Donegal, but seems to have had no surviving issue, and secondly as his third wife Sir Henry Brooke of Brookeborough

Brookeborough (; Irish language, Irish: ''Achadh Lon'', meaning 'Field of the Blackbirds') is a village in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland, at the westerly foot of Slieve Beagh. It lies about eleven miles east of Enniskillen, just off the A4 r ...

and had issue, including George.

Lady Docwra outlived her husband and both of her sons, and survived till 1648: like her elder son she was living in a state of some poverty in her later years, despite receiving a legacy from Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork

Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork (13 October 1566 – 15 September 1643), also known as the Great Earl of Cork, was an English politician who served as Lord Treasurer of the Kingdom of Ireland.

Lord Cork was an important figure in the continuing ...

, who had been a close friend and ally of her late husband in his last years.

Character

As a soldier Docwra was brave, skilful and ruthless; even the Irish reportedly admired him as "an illustriousknight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

of wisdom and prudence, a pillar of battle and conflict".McGurk p.270 He showed considerable skill in negotiating with the Irish clans of Ulster, and was known for fomenting quarrels among them to strengthen the Crown's position. Historians have remarked that the accusations made against Docwra by his political enemies of excessive "leniency" towards the Irish would have astonished the Irish themselves, thousands of whom are said to have died, directly or indirectly, as a result of his actions. As Treasurer of War, he had his critics, but he also enjoyed an enviable reputation for being diligent, conscientious and upright, if rather slow in conducting business.

In his private life, he had a reputation for being honest, public-spirited, and a man of independent judgment. In religious matters he is said, by the standards of the time, to have been tolerant enough. While there is no doubt that English troops who were under his command killed a number of priests

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

, his biographer argues that Docwra neither ordered nor approved of these killings.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Docwra of Culmore, Henry Docwra, 1st Baron Barons in the Peerage of Ireland Peers of Ireland created by James I People from Thatcham People from Bradfield, Berkshire English generals 1564 births 1631 deaths 16th-century Anglo-Irish people People of the Nine Years' War (Ireland) Henry 17th-century Anglo-Irish people English military personnel of the Eighty Years' War Military personnel from Berkshire English people of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) Kingdom of England people in the Kingdom of Ireland