Henry Cotton (doctor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry Andrews Cotton (May 18, 1876 – May 8, 1933) was an American psychiatrist and the medical director of the New Jersey State Hospital at Trenton (now Trenton Psychiatric Hospital), in

Henry Andrews Cotton (May 18, 1876 – May 8, 1933) was an American psychiatrist and the medical director of the New Jersey State Hospital at Trenton (now Trenton Psychiatric Hospital), in

Henry Andrews Cotton (May 18, 1876 – May 8, 1933) was an American psychiatrist and the medical director of the New Jersey State Hospital at Trenton (now Trenton Psychiatric Hospital), in

Henry Andrews Cotton (May 18, 1876 – May 8, 1933) was an American psychiatrist and the medical director of the New Jersey State Hospital at Trenton (now Trenton Psychiatric Hospital), in Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County. It was the capital of the United States from November 1 to December 24, 1784.experimental surgery and

Cotton began to implement the emerging medical theory of infection-based psychological disorders by pulling patients' teeth, as they were suspected of harboring infections. If this failed to cure a patient, he sought sources of infection in

Cotton began to implement the emerging medical theory of infection-based psychological disorders by pulling patients' teeth, as they were suspected of harboring infections. If this failed to cure a patient, he sought sources of infection in

episode 290

Chapter on Trenton's Charitable Institutions, including Trenton Hospital, from 1929 History book

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cotton, Henry American psychiatrists 1876 births 1933 deaths Physicians from New Jersey Human subject research in the United States

bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

techniques on patients, which included the routine removal of some or all of patients' teeth as well as tonsils, spleens, colons, ovaries, and other organs. These pseudoscientific practices persisted even after statistical reviews disproved Cotton's claims of high cure rates and revealed high mortality rates

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of de ...

as a result of these procedures.Ian Freckelton

Ian Freckelton is an Australian barrister, judge (in Nauru), international academic, and high-profile legal scholar and jurist. He is known for his extensive writing and speaking in more than 30 countries on issues related to health law, expe ...

. Madhouse: A Tragic Tale of Megalomania and Modern Medicine. (Book review), ''Psychiatry, Psychology and Law'', Vol. 12, No. 2, 2005, pp. 435-438.

Cotton became the medical director of the New Jersey State Hospital at Trenton at the age of 30. As director, Cotton implemented changes to how the hospital operated, such as abolishing mechanical restraints, and requiring daily staff meetings to discuss outpatient care. Cotton was motivated by the new medical research of the 20th century, and held the belief that various mental illnesses were caused by untreated infections in the body. This theory, called biological psychiatry, was introduced to him by Dr. Adolf Meyer, and was in contrast to the eugenic theories of the era that emphasized heredity. At the time, Cotton was a leading practitioner of biological psychiatry in the United States.

Education and career

Henry A. Cotton studied in Europe underEmil Kraepelin

Emil Wilhelm Georg Magnus Kraepelin (; ; 15 February 1856 – 7 October 1926) was a German psychiatrist.

H. J. Eysenck's ''Encyclopedia of Psychology'' identifies him as the founder of modern scientific psychiatry, psychopharmacology and psych ...

and Alois Alzheimer, considered the pioneers of the day, and was a student of Dr. Adolf Meyer of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (JHUSOM) is the medical school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1893, the School of Medicine shares a campus with the Johns Hopkins Hospi ...

, who dominated American psychiatry

Psychiatry is the specialty (medicine), medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of mental disorders. These include various maladaptations related to mood, behaviour, cognition, and perceptions. See glossary of psych ...

in the early 1900s. He studied medicine at Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

and at University of Maryland

The University of Maryland, College Park (University of Maryland, UMD, or simply Maryland) is a public land-grant research university in College Park, Maryland. Founded in 1856, UMD is the flagship institution of the University System of M ...

. Cotton began to implement the emerging medical theory of infection-based psychological disorders by pulling patients' teeth, as they were suspected of harboring infections. If this failed to cure a patient, he sought sources of infection in

Cotton began to implement the emerging medical theory of infection-based psychological disorders by pulling patients' teeth, as they were suspected of harboring infections. If this failed to cure a patient, he sought sources of infection in tonsil

The tonsils are a set of lymphoid organs facing into the aerodigestive tract, which is known as Waldeyer's tonsillar ring and consists of the adenoid tonsil, two tubal tonsils, two palatine tonsils, and the lingual tonsils. These organs play ...

s and sinuses and often a tonsillectomy was recommended as an additional treatment. If a cure was not achieved after these procedures, other organs were suspected of harboring infection. Testicle

A testicle or testis (plural testes) is the male reproductive gland or gonad in all bilaterians, including humans. It is homologous to the female ovary. The functions of the testes are to produce both sperm and androgens, primarily testoste ...

s, ovaries

The ovary is an organ in the female reproductive system that produces an ovum. When released, this travels down the fallopian tube into the uterus, where it may become fertilized by a sperm. There is an ovary () found on each side of the body. T ...

, gall bladder

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath the liver, although ...

s, stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

s, spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

s, cervixes, and especially colons were suspected as the focus of infection and were removed surgically.

Being before even rudimentary scientific methods such as control groups—and by extension, double-blind experiments—existed, statistical methodology for applications in human behaviour and medical research did not emerge during Cottons' lifetime. He could only follow faulty methods to compile data, much of it allowing for projection of anticipated results. He reported wonderful success with his procedures, with cure rates of 85%; this, in conjunction with the feeling at the time that investigating such biological causes, was the state of the art of medicine, brought him a great deal of attention, and worldwide praise. He was honoured at medical institutions and associations in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe and asked to make presentations about his work and to share information with others who practised the same or similar methods. Patients, or their families, begged to be treated at Trenton, and those who could not, demanded that their own doctors treat them with these new wonder-cures. The state acknowledged the savings in expenses to taxpayers from the new treatments and cures. In June 1922, the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' wrote in a review of Cotton's published lectures:

At the State Hospital at Trenton, N.J., under the brilliant leadership of the medical director, Dr. Henry A. Cotton, there is on foot the most searching, aggressive, and profound scientific investigation that has yet been made of the whole field of mental and nervous disorders... there is hope, high hope... for the future.In an era before antibiotics, surgery resulted in a very high rate of postoperative

morbidity

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

and mortality, largely from postoperative infection. Among his patients at this time was Margaret Fisher, daughter of wealthy and famed Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this field there are ...

Irving Fisher, who believed in the hygienic movement of the period. Diagnosed by physicians in Bloomingdale Asylum as schizophrenic, which was before the modern development of some pharmaceutical

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy (pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field an ...

agents, Fisher had his daughter transferred to Trenton. However, because Cotton attributed her condition to a "marked retention of fecal matter in the cecal colon with marked enlargement of the colon in this area", she was subjected to a series of colonic surgeries before dying of streptococcal infection in 1919. The danger of surgery was recognised by some patients in the institution, who, despite their mental illness, developed a very rational fear of the surgical procedures, some resisting violently as they were forced into the operating theater

An operating theater (also known as an operating room (OR), operating suite, or operation suite) is a facility within a hospital where surgical operations are carried out in an aseptic environment.

Historically, the term "operating theater" refe ...

in complete contradiction of what are now commonly accepted medical ethics. A paternalistic attitude and the permission of the family of seriously insane patients were the basis of intervention at the time.

Differences of professional opinion existed among psychiatrists regarding focal sepsis as a cause of psychosis and not all believed in the benefits of surgical intervention to achieve cures. Dr. Meyer, head of the most respected psychiatric clinic and training institution for psychiatrists in the United States, at Johns Hopkins University, accepted the theory. He was encouraged by a like-minded member of the state board of trustees who oversaw Trenton State Hospital to provide an independent professional review of the work of Cotton's staff. Meyer commissioned another of his former students who practised psychiatry on his staff at the Phipps Clinic, Dr. Phyllis Greenacre, to critique Cotton's work. Her study began in the fall of 1924 just after Meyer visited the hospital and privately had expressed concern about the statistical methods being applied to provide an assessment of Cotton's work. Cotton's staff made no effort to facilitate the study.

Investigation and controversy

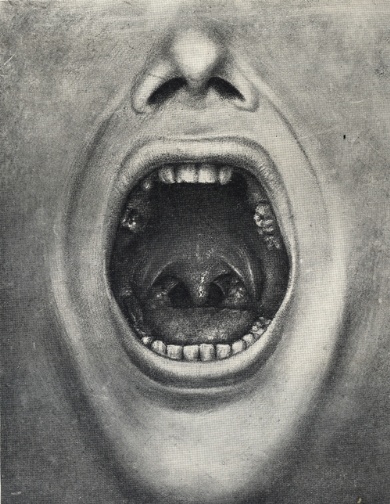

From the outset, Greenacre's reports were critical, with regard to both the hospital, which she felt was as unwholesome as the typical asylum and Cotton, whom she found "singularly peculiar". She realised that the appearance and behaviour of almost all of the psychotic patients were disturbing to her because their teeth had been removed, making it difficult for them to eat or speak. Further reports cast serious doubt on Cotton's reported results; she found the staff records to be chaotic and the data to be internally contradictory. In 1925 criticism of the hospital reached theNew Jersey State Senate

The New Jersey Senate was established as the upper house of the New Jersey Legislature by the Constitution of 1844, replacing the Legislative Council. There are 40 legislative districts, representing districts with an average population of 232, ...

, which launched an investigation with testimony from unhappy former patients and employees of the hospital. Countering the criticism, the trustees of the hospital confirmed their confidence in the staff and director and presented extensive professional praise of the hospital and the procedures followed under the direction of Cotton, whom they considered a pioneer. On September 24, 1925, ''The New York Times'' stated that, "eminent physicians and surgeons testified that the New Jersey State Hospital for the Insane was the most progressive institution in the world for the care of the insane and that the newer method of treating the insane by the removal of focal infection placed the institution in a unique position with respect to hospitals for the mentally ill" and related accolades given in support of Henry A. Cotton by many professionals and politicians.

Soon Cotton opened a private hospital in Trenton which did a hugely lucrative business treating mentally ill members of rich families seeking the most modern treatments for their conditions. Meyer reassigned Greenacre without completing her report and resisted her efforts to complete the report. Admitting a shared belief in the possibility that focal sepsis might be the source of mental illness, Meyer never pressed his protégé to confront the scientific analysis of the erroneous statistics the hospital staff provided to Cotton, his silence guaranteeing the continuance of the practices. Later Cotton would occasionally admit to death rates as high as 30% in his published papers. It appears that the true death rates were closer to 45% and that Cotton never fully recognised the errors his staff made in analyzing his work.

In the early 1930s, Cotton's rate of postoperative mortality began to be a matter of professional debate in the state department of institutions, with some concerned that he intended to press to resume his position at the state hospital. Another report on Cotton's work was begun in 1932 by Emil Frankel. He noted that he had seen Greenacre's report and agreed with it substantially, but his report also failed to be completed.

In October 1930, Cotton was retired from the state hospital and was appointed medical director emeritus. Although this ended the abominable surgeries which were so dangerous before the discovery of antibiotics, the hospital continued to adhere to Cotton's humane treatment guidelines and, to carry out his less risky medical procedures until the late 1950s. Henry A. Cotton continued to direct the staff at Charles Hospital until his death.

Henry A. Cotton died suddenly of a heart attack on May 8, 1933, in Trenton, New Jersey and was lauded in ''The New York Times'' and the local press, as well as international professional publications, for having been a pioneer seeking a better path for the treatment of the patients in mental hospitals.

In popular culture

A fictionalized Dr. Cotton was portrayed by actor John Hodgman in theCinemax

Cinemax is an American pay television, cable, and satellite television network owned by the Home Box Office, Inc. subsidiary of Warner Bros. Discovery. Developed as a companion "maxi-pay" service complementing the offerings shown on parent ...

drama '' The Knick'' in 2014.

He is portrayed by Byron Jennings in '' Boardwalk Empire''.

The story of Dr. Cotton was subjected to comedic treatment on the podcast '' The Dollop'episode 290

See also

*'' Acres of Skin'' *'' The Plutonium Files'' *'' The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease'' *Unethical human experimentation in the United States

Numerous experiments which are performed on human test subjects in the United States are considered unethical, because they are performed without the knowledge or informed consent of the test subjects. Such tests have been performed throughout ...

References

Further reading

*'' Madhouse: A Tragic Tale of Megalomania and Modern Medicine'',Andrew Scull

Andrew T. Scull (born 1947) is a British-born sociologist who researches the social history of medicine and the history of psychiatry. He is a distinguished professor of sociology and science studies at University of California, San Diego, and ...

, Yale University Press, 2005.

External links

* *Chapter on Trenton's Charitable Institutions, including Trenton Hospital, from 1929 History book

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cotton, Henry American psychiatrists 1876 births 1933 deaths Physicians from New Jersey Human subject research in the United States