Grand Teton National Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Grand Teton National Park is an American

John Colter is widely considered the first mountain man and, like those that came to the Jackson Hole region over the next 30 years, he was there primarily for the profitable fur trapping; the region was rich with the highly sought after pelts of

John Colter is widely considered the first mountain man and, like those that came to the Jackson Hole region over the next 30 years, he was there primarily for the profitable fur trapping; the region was rich with the highly sought after pelts of

The first U.S. Government-sponsored expedition to enter Jackson Hole was the 1859–60

The first U.S. Government-sponsored expedition to enter Jackson Hole was the 1859–60

To the north of Jackson Hole, Yellowstone National Park had been established in 1872, and by the close of the 19th century, conservationists wanted to expand the boundaries of that park to include at least the Teton Range. By 1907, in an effort to regulate water flow for irrigation purposes, the

To the north of Jackson Hole, Yellowstone National Park had been established in 1872, and by the close of the 19th century, conservationists wanted to expand the boundaries of that park to include at least the Teton Range. By 1907, in an effort to regulate water flow for irrigation purposes, the

During the last 25 years of the 19th century, the mountains of the Teton Range became a focal point for explorers wanting to claim the first ascents of the peaks. However, white explorers may not have been the first to climb many of the peaks and the earliest first ascent of even the formidable Grand Teton itself might have been achieved long before written history documented it. Native American relics remain including ''The Enclosure'', an obviously man-made structure that is located about below the summit of Grand Teton at a point near the Upper Saddle (). Nathaniel P. Langford and James Stevenson, both members of the Hayden Geological Survey of 1872, found The Enclosure during their early attempt to summit Grand Teton. Langford claimed that he and Stevenson climbed Grand Teton, but were vague as to whether they had made it to the summit. Their reported obstacles and sightings were never corroborated by later parties. Langford and Stevenson likely did not get much further than The Enclosure. The first ascent of Grand Teton that is substantiated was made by William O. Owen, Frank Petersen, John Shive and Franklin Spencer Spalding on August 11, 1898. Owen had made two previous attempts on the peak and after publishing several accounts of this first ascent, discredited any claim that Langford and Stevenson had ever reached beyond The Enclosure in 1872. The disagreement over which party first reached the top of Grand Teton may be the greatest controversy in the history of American mountaineering. After 1898 no other ascents of Grand Teton were recorded until 1923.

By the mid-1930s, more than a dozen different climbing routes had been established on Grand Teton including the northeast ridge in 1931 by Glenn Exum. Glenn Exum teamed up with another noted climber named Paul Petzoldt to found the

During the last 25 years of the 19th century, the mountains of the Teton Range became a focal point for explorers wanting to claim the first ascents of the peaks. However, white explorers may not have been the first to climb many of the peaks and the earliest first ascent of even the formidable Grand Teton itself might have been achieved long before written history documented it. Native American relics remain including ''The Enclosure'', an obviously man-made structure that is located about below the summit of Grand Teton at a point near the Upper Saddle (). Nathaniel P. Langford and James Stevenson, both members of the Hayden Geological Survey of 1872, found The Enclosure during their early attempt to summit Grand Teton. Langford claimed that he and Stevenson climbed Grand Teton, but were vague as to whether they had made it to the summit. Their reported obstacles and sightings were never corroborated by later parties. Langford and Stevenson likely did not get much further than The Enclosure. The first ascent of Grand Teton that is substantiated was made by William O. Owen, Frank Petersen, John Shive and Franklin Spencer Spalding on August 11, 1898. Owen had made two previous attempts on the peak and after publishing several accounts of this first ascent, discredited any claim that Langford and Stevenson had ever reached beyond The Enclosure in 1872. The disagreement over which party first reached the top of Grand Teton may be the greatest controversy in the history of American mountaineering. After 1898 no other ascents of Grand Teton were recorded until 1923.

By the mid-1930s, more than a dozen different climbing routes had been established on Grand Teton including the northeast ridge in 1931 by Glenn Exum. Glenn Exum teamed up with another noted climber named Paul Petzoldt to found the

Grand Teton National Park is one of the ten most visited national parks in the U.S., with an annual average of 2.75 million visitors in the period from 2007 to 2016, with 3.27 million visiting in 2016. The National Park Service is a federal agency of the

Grand Teton National Park is one of the ten most visited national parks in the U.S., with an annual average of 2.75 million visitors in the period from 2007 to 2016, with 3.27 million visiting in 2016. The National Park Service is a federal agency of the

]

Grand Teton National Park is located in the northwestern region of the U.S. state of Wyoming. To the north the park is bordered by the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway, which is administered by Grand Teton National Park. The scenic highway with the same name passes from the southern boundary of Grand Teton National Park to West Thumb in Yellowstone National Park. Grand Teton National Park covers approximately , while the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway includes . Most of the Jackson Hole valley and virtually all the major mountain peaks of the Teton Range are within the park. The

]

Grand Teton National Park is located in the northwestern region of the U.S. state of Wyoming. To the north the park is bordered by the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway, which is administered by Grand Teton National Park. The scenic highway with the same name passes from the southern boundary of Grand Teton National Park to West Thumb in Yellowstone National Park. Grand Teton National Park covers approximately , while the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway includes . Most of the Jackson Hole valley and virtually all the major mountain peaks of the Teton Range are within the park. The

In addition to Grand Teton, another nine peaks are over above

In addition to Grand Teton, another nine peaks are over above

Jackson Hole is a by wide

Jackson Hole is a by wide

Most of the lakes in the park were formed by glaciers and the largest of these lakes are located at the base of the Teton Range. In the northern section of the park lies Jackson Lake, the largest lake in the park at in length, wide and deep. Though Jackson Lake is natural, the Jackson Lake Dam was constructed at its outlet before the creation of the park, and the lake level was raised almost consequently. East of the

Most of the lakes in the park were formed by glaciers and the largest of these lakes are located at the base of the Teton Range. In the northern section of the park lies Jackson Lake, the largest lake in the park at in length, wide and deep. Though Jackson Lake is natural, the Jackson Lake Dam was constructed at its outlet before the creation of the park, and the lake level was raised almost consequently. East of the

The major peaks of the Teton Range were carved into their current shapes by long-vanished

The major peaks of the Teton Range were carved into their current shapes by long-vanished

Grand Teton National Park has some of the most ancient rocks found in any American national park. The oldest rocks dated so far are 2,680 ± 12 million years old, though even older rocks are believed to exist in the park. Formed during the

Grand Teton National Park has some of the most ancient rocks found in any American national park. The oldest rocks dated so far are 2,680 ± 12 million years old, though even older rocks are believed to exist in the park. Formed during the

Grand Teton National Park and the surrounding region host over 1,000 species of

Grand Teton National Park and the surrounding region host over 1,000 species of

File:Mountain Lion in Grand Teton National Park.jpg, Though cougars are present in Grand Teton, they are rarely seen.

File:Moose in Grand Teton NP near Leigh Lake-750px.JPG, Moose near Leigh Lake

File:Snakecutt.jpg, Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat trout has tiny black spots over most of its body.

File:Bison Teton.JPG, Bison grazing in Jackson Hole

The role of wildfire is an important one for plant and animal species diversity. Many tree species have evolved to mainly germinate after a wildfire. Regions of the park that have experienced wildfire in historical times have greater species diversity after reestablishment than those regions that have not been influenced by fire. Though the

The role of wildfire is an important one for plant and animal species diversity. Many tree species have evolved to mainly germinate after a wildfire. Regions of the park that have experienced wildfire in historical times have greater species diversity after reestablishment than those regions that have not been influenced by fire. Though the

An average of 4,000 climbers per year make an attempt to summit Grand Teton and most ascend up

An average of 4,000 climbers per year make an attempt to summit Grand Teton and most ascend up

Grand Teton National Park has five front-country vehicular access campgrounds. The largest is the Colter Bay and Gros Ventre campgrounds, and each has 350 campsites which can accommodate large

Grand Teton National Park has five front-country vehicular access campgrounds. The largest is the Colter Bay and Gros Ventre campgrounds, and each has 350 campsites which can accommodate large

Grand Teton National Park allows boating on all the lakes in Jackson Hole, but motorized boats can only be used on Jackson and Jenny Lakes. While there is no maximum horsepower limit on Jackson Lake (though there is a noise restriction), Jenny Lake is restricted to 10 horsepower. Only non-motorized boats are permitted on Bearpaw, Bradley, Emma Matilda, Leigh, Phelps, String, Taggart and Two Ocean Lakes. There are four designated boat launches located on Jackson Lake and one on Jenny Lake. Additionally, sailboats, windsurfers, and water skiing are only allowed on Jackson Lake and no jet skis are permitted on any of the park waterways. All boats are required to comply with various safety regulations including personal flotation devices for each passenger. Only non-motorized watercraft are permitted on the Snake River. All other waterways in the park are off limits to boating, and this includes all alpine lakes and tributary streams of the Snake River.

In 2010, Grand Teton National Park started requiring all boats to display an Aquatic Invasive Species decal issued by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department or a Yellowstone National Park boat permit. In an effort to keep the park waterways free of various invasive species such as the

Grand Teton National Park allows boating on all the lakes in Jackson Hole, but motorized boats can only be used on Jackson and Jenny Lakes. While there is no maximum horsepower limit on Jackson Lake (though there is a noise restriction), Jenny Lake is restricted to 10 horsepower. Only non-motorized boats are permitted on Bearpaw, Bradley, Emma Matilda, Leigh, Phelps, String, Taggart and Two Ocean Lakes. There are four designated boat launches located on Jackson Lake and one on Jenny Lake. Additionally, sailboats, windsurfers, and water skiing are only allowed on Jackson Lake and no jet skis are permitted on any of the park waterways. All boats are required to comply with various safety regulations including personal flotation devices for each passenger. Only non-motorized watercraft are permitted on the Snake River. All other waterways in the park are off limits to boating, and this includes all alpine lakes and tributary streams of the Snake River.

In 2010, Grand Teton National Park started requiring all boats to display an Aquatic Invasive Species decal issued by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department or a Yellowstone National Park boat permit. In an effort to keep the park waterways free of various invasive species such as the

Visitors are allowed to

Visitors are allowed to

The Craig Thomas Discovery and Visitor Center adjacent to the park headquarters at Moose, Wyoming, is open year-round. Opened in 2007 to replace an old, inadequate visitor center, the facility is named for the late

The Craig Thomas Discovery and Visitor Center adjacent to the park headquarters at Moose, Wyoming, is open year-round. Opened in 2007 to replace an old, inadequate visitor center, the facility is named for the late

Grand Teton Association

* {{Featured article Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem National parks in Wyoming National parks of the Rocky Mountains Protected areas established in 1929 Rockefeller family Teton County, Wyoming Tourist attractions in Teton County, Wyoming History of the Rocky Mountains 1929 establishments in Wyoming

national park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

in northwestern Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

. At approximately , the park includes the major peaks of the Teton Range

The Teton Range is a mountain range of the Rocky Mountains in North America. It extends for approximately in a north–south direction through the U.S. state of Wyoming, east of the Idaho state line. It is south of Yellowstone National Park and ...

as well as most of the northern sections of the valley known as Jackson Hole

Jackson Hole (originally called Jackson's Hole by mountain men) is a valley between the Gros Ventre and Teton mountain ranges in the U.S. state of Wyoming, near the border with Idaho, in Teton County, one of the richest counties in the Unit ...

. Grand Teton National Park is only south of Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowston ...

, to which it is connected by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

–managed John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway. Along with surrounding national forests, these three protected areas constitute the almost Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) is one of the last remaining large, nearly intact ecosystems in the northern temperate zone of the Earth. It is located within the northern Rocky Mountains, in areas of northwestern Wyoming, southwestern M ...

, one of the world's largest intact mid-latitude temperate ecosystems.

The human history of the Grand Teton region dates back at least 11,000 years when the first nomadic hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

Paleo-Indians began migrating into the region during warmer months to pursue food and supplies. In the early 19th century, the first white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

explorers encountered the eastern Shoshone natives

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

. Between 1810 and 1840, the region attracted fur trading companies that vied for control of the lucrative beaver pelt trade. U.S. Government expeditions to the region commenced in the mid-19th century as an offshoot of exploration in Yellowstone, with the first permanent white settlers in Jackson Hole arriving in the 1880s.

Efforts to preserve the region as a national park began in the late 19th century, and in 1929 Grand Teton National Park was established, protecting the Teton Range's major peaks. The valley of Jackson Hole remained in private ownership until the 1930s when conservationists led by John D. Rockefeller Jr.

John Davison Rockefeller Jr. (January 29, 1874 – May 11, 1960) was an American financier and philanthropist, and the only son of Standard Oil co-founder John D. Rockefeller.

He was involved in the development of the vast office complex in M ...

began purchasing land in Jackson Hole to be added to the existing national park. Against public opinion and with repeated Congressional efforts to repeal the measures, much of Jackson Hole was set aside for protection as Jackson Hole National Monument in 1943. The monument was abolished in 1950 and most of the monument land was added to Grand Teton National Park.

Grand Teton National Park is named for Grand Teton

Grand Teton is the highest mountain in Grand Teton National Park, in Northwest Wyoming, and a classic destination in American mountaineering.

Geography

Grand Teton, at , is the highest point of the Teton Range, and the second highest peak in t ...

, the tallest mountain in the Teton Range. The naming of the mountains is attributed to early 19th-century French-speaking trappers—''les trois tétons'' (the three teats) was later anglicized and shortened to ''Tetons''. At , Grand Teton abruptly rises more than above Jackson Hole, almost higher than Mount Owen, the second-highest summit in the range. The park has numerous lakes, including Jackson Lake as well as streams of varying length and the upper main stem

In hydrology, a mainstem (or trunk) is "the primary downstream segment of a river, as contrasted to its tributaries". Water enters the mainstem from the river's drainage basin, the land area through which the mainstem and its tributaries flow.. A ...

of the Snake River

The Snake River is a major river of the greater Pacific Northwest region in the United States. At long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, in turn, the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. The Snake ...

. Though in a state of recession, a dozen small glaciers persist at the higher elevations near the highest peaks in the range. Some of the rocks in the park are the oldest found in any American national park and have been dated at nearly 2.7 billion years.

Grand Teton National Park is an almost pristine ecosystem and the same species of flora and fauna that have existed since prehistoric times can still be found there. More than 1,000 species of vascular plants

Vascular plants (), also called tracheophytes () or collectively Tracheophyta (), form a large group of land plants ( accepted known species) that have lignified tissues (the xylem) for conducting water and minerals throughout the plant. They al ...

, dozens of species of mammals, 300 species of birds, more than a dozen fish species, and a few species of reptiles and amphibians inhabit the park. Due to various changes in the ecosystem, some of them human-induced, efforts have been made to provide enhanced protection to some species of native fish and the increasingly threatened whitebark pine

''Pinus albicaulis'', known by the common names whitebark pine, white bark pine, white pine, pitch pine, scrub pine, and creeping pine, is a conifer tree native to the mountains of the western United States and Canada, specifically subalpine ...

.

Grand Teton National Park is a popular destination for mountaineering, hiking, fishing, and other forms of recreation. There are more than 1,000 drive-in campsites and over of hiking trails that provide access to backcountry

In the United States, a backcountry or backwater is a geographical area that is remote, undeveloped, isolated, or difficult to access.

Terminology Backcountry and wilderness within United States national parks

The National Park Service (NPS) ...

camping areas. Noted for world-renowned trout fishing, the park is one of the few places to catch Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat trout

The Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat trout is a form of the cutthroat trout (''Oncorhynchus clarkii'') that is considered either as a separate subspecies ''O. c. behnkei'', or as a variety of the Yellowstone cutthroat trout (''O. c. bouvier ...

. Grand Teton has several National Park Service–run visitor centers and privately operated concessions for motels, lodges, gas stations, and marinas.

Human history

Paleo-Indians and Native Americans

Paleo-Indian presence in what is now Grand Teton National Park dates back more than 11,000 years. Jackson Hole valley climate at that time was colder and more alpine than thesemi-arid climate

A semi-arid climate, semi-desert climate, or steppe climate is a dry climate sub-type. It is located on regions that receive precipitation below potential evapotranspiration, but not as low as a desert climate. There are different kinds of semi-ar ...

found today, and the first humans were migratory hunter-gatherers spending summer months in Jackson Hole and wintering in the valleys west of the Teton Range. Along the shores of Jackson Lake, fire pits, tools, and what are thought to have been fishing weights have been discovered. One of the tools found is of a type associated with the Clovis culture

The Clovis culture is a prehistoric Paleoamerican culture, named for distinct stone and bone tools found in close association with Pleistocene fauna, particularly two mammoths, at Blackwater Locality No. 1 near Clovis, New Mexico, in 1936 ...

, and tools from this cultural period date back at least 11,500 years. Some of the tools are made of obsidian

Obsidian () is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.

Obsidian is produced from felsic lava, rich in the lighter elements s ...

which chemical analysis indicates came from sources near present-day Teton Pass

Teton Pass is a high mountain pass in the western United States, located at the southern end of the Teton Range in western Wyoming, between Wilson and Victor, Idaho. At an elevation of above sea level, the pass provides access from the Jackson H ...

, south of Grand Teton National Park. Though obsidian was also available north of Jackson Hole, virtually all the obsidian spear points found are from a source to the south, indicating that the main seasonal migratory route for the Paleo-Indian was from this direction. Elk

The elk (''Cervus canadensis''), also known as the wapiti, is one of the largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. The common ...

, which winter on the National Elk Refuge

The National Elk Refuge is a Wildlife Refuge located in Jackson Hole in the U.S. state of Wyoming. It was created in 1912 to protect habitat and provide sanctuary for one of the largest elk (also known as wapiti) herds. With a total of , the refu ...

at the southern end of Jackson Hole and northwest into higher altitudes during spring and summer, follow a similar migratory pattern to this day. From 11,000 to about 500 years ago, there is little evidence of change in the migratory patterns amongst the Native American groups in the region and no evidence that indicates any permanent human settlement.

When white American colonists first entered the region in the first decade of the 19th century, they encountered the eastern tribes of the Shoshone people. Most of the Shoshone that lived in the mountain vastness of the greater Yellowstone region continued to be pedestrian while other groups of Shoshone that resided in lower elevations had limited use of horses. The mountain-dwelling Shoshone were known as " Sheep-eaters" or "'' Tukudika''" as they referred to themselves, since a staple of their diet was the Bighorn Sheep

The bighorn sheep (''Ovis canadensis'') is a species of sheep native to North America. It is named for its large horns. A pair of horns might weigh up to ; the sheep typically weigh up to . Recent genetic testing indicates three distinct subspec ...

. The Shoshones continued to follow the same migratory pattern as their predecessors and have been documented as having a close spiritual relationship with the Teton Range. Several stone enclosures on some of the peaks, including on the upper slopes of Grand Teton (known simply as ''The Enclosure'') are thought to have been used by Shoshone during vision quest

A vision quest is a rite of passage in some Native American cultures. It is usually only undertaken by young males entering adulthood.

Individual Indigenous cultures have their own names for their rites of passage. "Vision quest" is an English ...

s. The Teton and Yellowstone region Shoshone relocated to the Wind River Indian Reservation

The Wind River Indian Reservation, in the west-central portion of the U.S. state of Wyoming, is shared by two Native American tribes, the Eastern Shoshone ( shh, Gweechoon Deka, ''meaning: "buffalo eaters"'') and the Northern Arapaho ( arp, ...

after it was established in 1868. The reservation is situated southeast of Jackson Hole on land that was selected by Chief Washakie.

Fur trade exploration

TheLewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

(1804–1806) passed well north of the Grand Teton region. During their return trip from the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, expedition member John Colter

John Colter (c.1770–1775 – May 7, 1812 or November 22, 1813) was a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806). Though party to one of the more famous expeditions in history, Colter is best remembered for explorations he made ...

was given an early discharge so he could join two fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

trappers who were heading west in search of beaver pelts. Colter was later hired by Manuel Lisa

Manuel Lisa, also known as Manuel de Lisa (September 8, 1772 in New Orleans Louisiana (New Spain) – August 12, 1820 in St. Louis, Missouri), was a Spanish citizen and later, became an American citizen who, while living on the western frontier, ...

to lead fur trappers and explore the region around the Yellowstone River

The Yellowstone River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the Western United States. Considered the principal tributary of upper Missouri, via its own tributaries it drains an area with headwaters across the mountains an ...

. During the winter of 1807/08, Colter passed through Jackson Hole and was the first Caucasian to see the Teton Range. Lewis and Clark expedition co-leader William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

produced a map based on the previous expedition and included the explorations of John Colter in 1807, apparently based on discussions between Clark and Colter when the two met in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

in 1810. Another map attributed to William Clark indicates John Colter entered Jackson Hole from the northeast, crossing the Continental Divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

at either Togwotee Pass

Togwotee Pass (pronounced TOH-guh-tee) is a high mountain pass in the western United States, at an elevation of above sea level. On the Continental Divide in the Absaroka Mountains of northwestern Wyoming in Teton County, it is between ...

or Union Pass and left the region after crossing Teton Pass, following the well established Native American trails. In 1931, the Colter Stone, a rock carved in the shape of a head with the inscription "John Colter" on one side and the year "1808" on the other, was discovered in a field in Tetonia, Idaho

Tetonia is a city in Teton County, Idaho, United States, about northeast of Idaho Falls, Idaho (center to center) and about northwest of Denver, Colorado. The population was 269 at the 2010 census.

Geography

According to the United States Cen ...

, which is west of Teton Pass. The Colter Stone has not been authenticated to have been created by John Colter and may have been the work of later expeditions to the region.

John Colter is widely considered the first mountain man and, like those that came to the Jackson Hole region over the next 30 years, he was there primarily for the profitable fur trapping; the region was rich with the highly sought after pelts of

John Colter is widely considered the first mountain man and, like those that came to the Jackson Hole region over the next 30 years, he was there primarily for the profitable fur trapping; the region was rich with the highly sought after pelts of beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers ar ...

and other fur-bearing animals. Between 1810 and 1812, the Astorians traveled through Jackson Hole and crossed Teton Pass as they headed east in 1812. After 1810, American and British fur trading companies were in competition for control of the North American fur trade

The North American fur trade is the commercial trade in furs in North America. Various Indigenous peoples of the Americas traded furs with other tribes during the pre-Columbian era. Europeans started their participation in the North American fur ...

, and American sovereignty over the region was not secured until the signing of the Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty is a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to t ...

in 1846. One party employed by the British North West Company

The North West Company was a fur trading business headquartered in Montreal from 1779 to 1821. It competed with increasing success against the Hudson's Bay Company in what is present-day Western Canada and Northwestern Ontario. With great weal ...

and led by explorer Donald Mackenzie entered Jackson Hole from the west in 1818 or 1819. The Tetons, as well as the valley west of the Teton Range known today as Pierre's Hole

Pierre's Hole is a shallow valley in the western United States in eastern Idaho, just west of the Teton Range in Wyoming. At an elevation over above sea level, it collects the headwaters of the Teton River, and was a strategic center of the fu ...

, may have been named by French-speaking Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

or French Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

trappers that were part of Mackenzie's party. Earlier parties had referred to the most prominent peaks of the Teton Range as the Pilot Knobs. The French trappers' ''les trois tétons'' (the three breasts) was later shortened to the Tetons.

Formed in the mid-1820s, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company

The enterprise that eventually came to be known as the Rocky Mountain Fur Company was established in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1822 by William Henry Ashley and Andrew Henry. Among the original employees, known as "Ashley's Hundred," were Jedediah ...

partnership included Jedediah Smith, William Sublette

William Lewis Sublette, also spelled Sublett (September 21, 1798 – July 23, 1845), was an American frontiersman, trapper, fur trader, explorer, and mountain man. After 1823, he became an agent of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, along with his ...

, and David Edward Jackson or "Davey Jackson". Jackson oversaw the trapping operations in the Teton region between 1826 and 1830. Sublette named the valley east of the Teton Range "Jackson's Hole" (later simply Jackson Hole) for Davey Jackson. As the demand for beaver fur declined and the various regions of the American West became depleted of beaver due to over trapping, American fur trading companies folded; however, individual mountain men continued to trap beaver in the region until about 1840. From the mid-1840s until 1860, Jackson Hole and the Teton Range were generally devoid of all but the small populations of Native American tribes that had already been there. Most overland human migration routes such as the Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

and Mormon Trails crossed over South Pass, well to the south of the Teton Range, and Caucasian influence in the Teton region was minimal until the U.S. Government commenced organized explorations.

Organized exploration and settlement

The first U.S. Government-sponsored expedition to enter Jackson Hole was the 1859–60

The first U.S. Government-sponsored expedition to enter Jackson Hole was the 1859–60 Raynolds Expedition

The Raynolds Expedition was a United States Army exploring and mapping expedition intended to map the unexplored territory between Fort Pierre, Dakota Territory and the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. The expedition was led by topographical ...

. Led by U.S. Army Captain William F. Raynolds

William Franklin Raynolds (March 17, 1820 – October 18, 1894) was an American explorer, engineer and U.S. army officer who served in the Mexican–American War and American Civil War. He is best known for leading the 1859–60 Raynolds Expedi ...

and guided by mountain man Jim Bridger

James Felix "Jim" Bridger (March 17, 1804 – July 17, 1881) was an American mountain man, trapper, Army scout, and wilderness guide who explored and trapped in the Western United States in the first half of the 19th century. He was known as Old ...

, it included naturalist F. V. Hayden, who later led other expeditions to the region. The expedition had been charged with exploring the Yellowstone region, but encountered difficulties crossing mountain passes due to snow. Bridger ended up guiding the expedition south over Union Pass then following the Gros Ventre River

The Gros Ventre River (''pronounced GROW-VAUNT'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 4, 2011 tributary of the Snake River in the state of Wyoming, USA. During ...

drainage to the Snake River and leaving the region over Teton Pass. Organized exploration of the region was halted during the American Civil War but resumed when F. V. Hayden led the well-funded Hayden Geological Survey of 1871

The Hayden Geological Survey of 1871 explored the region of northwestern Wyoming that later became Yellowstone National Park in 1872. It was led by geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden. The 1871 survey was not Hayden's first, but it was the first ...

. In 1872, Hayden oversaw explorations in Yellowstone, while a branch of his expedition known as the Snake River Division was led by James Stevenson and explored the Teton region. Along with Stevenson was photographer William Henry Jackson

William Henry Jackson (April 4, 1843 – June 30, 1942) was an American photographer, Civil War veteran, painter, and an explorer famous for his images of the American West. He was a great-great nephew of Samuel Wilson, the progenitor of Am ...

who took the first photographs of the Teton Range. The Hayden Geological Survey named many of the mountains and lakes in the region. The explorations by early mountain men and subsequent expeditions failed to identify any sources of economically viable mineral wealth. Nevertheless, small groups of prospectors set up claims and mining operations on several of the creeks and rivers. By 1900 all organized efforts to retrieve minerals had been abandoned.

Though the Teton Range was never permanently inhabited, pioneers began settling in the Jackson Hole valley to the east of the range in 1884. These earliest homesteaders were mostly single men who endured long winters, short growing seasons and rocky soils that were hard to cultivate. The region was most suited for the cultivation of hay and cattle ranching. By 1890, Jackson Hole had an estimated permanent population of 60. Menor's Ferry was built in 1892 near present-day Moose, Wyoming to provide access for wagons to the west side of the Snake River. Ranching increased significantly from 1900 to 1920, but a series of agricultural related economic downturns in the early 1920s left many ranchers destitute. Beginning in the 1920s, the automobile provided faster and easier access to areas of natural beauty and old military roads into Jackson Hole over Teton and Togwotee Passes were improved to accommodate the increased vehicle traffic. In response to the increased tourism, dude ranches

A guest ranch, also known as a dude ranch, is a type of ranch oriented towards visitors or tourism. It is considered a form of agritourism.

History

Guest ranches arose in response to the romanticization of the American West that began to occur ...

were established, some new and some from existing cattle ranches, so urbanized travelers could experience the life of a cattleman.

Establishment of the park

To the north of Jackson Hole, Yellowstone National Park had been established in 1872, and by the close of the 19th century, conservationists wanted to expand the boundaries of that park to include at least the Teton Range. By 1907, in an effort to regulate water flow for irrigation purposes, the

To the north of Jackson Hole, Yellowstone National Park had been established in 1872, and by the close of the 19th century, conservationists wanted to expand the boundaries of that park to include at least the Teton Range. By 1907, in an effort to regulate water flow for irrigation purposes, the United States Bureau of Reclamation

The Bureau of Reclamation, and formerly the United States Reclamation Service, is a federal agency under the U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees water resource management, specifically as it applies to the oversight and opera ...

had constructed a log crib dam at the Snake River outlet of Jackson Lake. This dam failed in 1910 and a new concrete Jackson Lake Dam

Jackson Lake Dam is a concrete and earth-fill dam in the western United States, at the outlet of Jackson Lake in northwestern Wyoming. The lake and dam are situated within Grand Teton National Park in Teton County. The Snake River emerges from ...

replaced it by 1911. The dam was further enlarged in 1916, raising lake waters as part of the Minidoka Project

The Minidoka Project is a series of public works by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to control the flow of the Snake River in Wyoming and Idaho, supplying irrigation water to farmlands in Idaho. One of the oldest Bureau of Reclamation projects in t ...

, designed to provide irrigation for agriculture in the state of Idaho. Further dam construction plans for other lakes in the Teton Range alarmed Yellowstone National Park superintendent Horace Albright

Horace Marden Albright (January 6, 1890 – March 28, 1987) was an American conservationist.

Horace Albright was born in 1890 in Bishop, California, the son of George Albright, a miner. He graduated from the University of California, Berkeley ...

, who sought to block such efforts. Jackson Hole residents were opposed to an expansion of Yellowstone, but were more in favor of the establishment of a separate national park which would include the Teton Range and six lakes at the base of the mountains. After congressional approval, President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

signed the executive order establishing the Grand Teton National Park on February 26, 1929.

The valley of Jackson Hole remained primarily in private ownership when John D. Rockefeller Jr.

John Davison Rockefeller Jr. (January 29, 1874 – May 11, 1960) was an American financier and philanthropist, and the only son of Standard Oil co-founder John D. Rockefeller.

He was involved in the development of the vast office complex in M ...

and his wife visited the region in the late 1920s. Horace Albright and Rockefeller discussed ways to preserve Jackson Hole from commercial exploitation, and in consequence, Rockefeller started buying Jackson Hole properties through the Snake River Land Company The Snake River Land Company or the Snake River Cattle and Stock Company was a land purchasing company established in 1927 by philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Jr. The company acted as a front so Rockefeller could buy land in the Jackson Hole val ...

to later turn them over to the National Park Service. In 1930, this plan was revealed to the residents of the region and was met with strong disapproval. Congressional efforts to prevent the expansion of Grand Teton National Park ended up putting the Snake River Land Company's holdings in limbo. By 1942 Rockefeller had become increasingly impatient that his purchased property might never be added to the park, and wrote to the Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry ...

Harold L. Ickes

Harold LeClair Ickes ( ; March 15, 1874 – February 3, 1952) was an American administrator, politician and lawyer. He served as United States Secretary of the Interior for nearly 13 years from 1933 to 1946, the longest tenure of anyone to hold th ...

that he was considering selling the land to another party. Secretary Ickes recommended to President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

that the Antiquities Act

The Antiquities Act of 1906 (, , ), is an act that was passed by the United States Congress and signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt on June 8, 1906. This law gives the President of the United States the authority to, by presidential procla ...

, which permitted presidents to set aside land for protection without the approval of Congress, be used to establish a national monument

A national monument is a monument constructed in order to commemorate something of importance to national heritage, such as a country's founding, independence, war, or the life and death of a historical figure.

The term may also refer to a spec ...

in Jackson Hole. Roosevelt created the Jackson Hole National Monument in 1943, using the land donated from the Snake River Land Company and adding additional property from Teton National Forest. The monument and park were adjacent to each other and both were administered by the National Park Service, but the monument designation ensured no funding allotment, nor provided a level of resource protection equal to the park. Members of Congress repeatedly attempted to have the new national monument abolished.

After the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, national public sentiment was in favor of adding the monument to the park, and though there was still much local opposition, the monument and park were combined in 1950. In recognition of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.'s efforts to establish and then expand Grand Teton National Park, a parcel of land between Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks was added to the National Park Service in 1972. This land and the road from the southern boundary of the park to West Thumb in Yellowstone National Park was named the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway. The Rockefeller family owned the JY Ranch, which bordered Grand Teton National Park to the southwest. In November 2007, the Rockefeller family transferred ownership of the ranch to the park for the establishment of the Laurance S. Rockefeller Preserve

The Laurance S. Rockefeller (LSR) Preserve is a refuge within Grand Teton National Park on the southern end of Phelps Lake, Wyoming. The site was originally known as the JY Ranch, a dude ranch. Starting in 1927, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. purc ...

, which was dedicated on June 21, 2008.

History of mountaineering

During the last 25 years of the 19th century, the mountains of the Teton Range became a focal point for explorers wanting to claim the first ascents of the peaks. However, white explorers may not have been the first to climb many of the peaks and the earliest first ascent of even the formidable Grand Teton itself might have been achieved long before written history documented it. Native American relics remain including ''The Enclosure'', an obviously man-made structure that is located about below the summit of Grand Teton at a point near the Upper Saddle (). Nathaniel P. Langford and James Stevenson, both members of the Hayden Geological Survey of 1872, found The Enclosure during their early attempt to summit Grand Teton. Langford claimed that he and Stevenson climbed Grand Teton, but were vague as to whether they had made it to the summit. Their reported obstacles and sightings were never corroborated by later parties. Langford and Stevenson likely did not get much further than The Enclosure. The first ascent of Grand Teton that is substantiated was made by William O. Owen, Frank Petersen, John Shive and Franklin Spencer Spalding on August 11, 1898. Owen had made two previous attempts on the peak and after publishing several accounts of this first ascent, discredited any claim that Langford and Stevenson had ever reached beyond The Enclosure in 1872. The disagreement over which party first reached the top of Grand Teton may be the greatest controversy in the history of American mountaineering. After 1898 no other ascents of Grand Teton were recorded until 1923.

By the mid-1930s, more than a dozen different climbing routes had been established on Grand Teton including the northeast ridge in 1931 by Glenn Exum. Glenn Exum teamed up with another noted climber named Paul Petzoldt to found the

During the last 25 years of the 19th century, the mountains of the Teton Range became a focal point for explorers wanting to claim the first ascents of the peaks. However, white explorers may not have been the first to climb many of the peaks and the earliest first ascent of even the formidable Grand Teton itself might have been achieved long before written history documented it. Native American relics remain including ''The Enclosure'', an obviously man-made structure that is located about below the summit of Grand Teton at a point near the Upper Saddle (). Nathaniel P. Langford and James Stevenson, both members of the Hayden Geological Survey of 1872, found The Enclosure during their early attempt to summit Grand Teton. Langford claimed that he and Stevenson climbed Grand Teton, but were vague as to whether they had made it to the summit. Their reported obstacles and sightings were never corroborated by later parties. Langford and Stevenson likely did not get much further than The Enclosure. The first ascent of Grand Teton that is substantiated was made by William O. Owen, Frank Petersen, John Shive and Franklin Spencer Spalding on August 11, 1898. Owen had made two previous attempts on the peak and after publishing several accounts of this first ascent, discredited any claim that Langford and Stevenson had ever reached beyond The Enclosure in 1872. The disagreement over which party first reached the top of Grand Teton may be the greatest controversy in the history of American mountaineering. After 1898 no other ascents of Grand Teton were recorded until 1923.

By the mid-1930s, more than a dozen different climbing routes had been established on Grand Teton including the northeast ridge in 1931 by Glenn Exum. Glenn Exum teamed up with another noted climber named Paul Petzoldt to found the Exum Mountain Guides

The Exum Mountain Guides is a mountain guide service based in the U.S. state of Wyoming. The guide service was founded in the 1926 by Paul Petzoldt and Glenn Exum, for whom the Exum Ridge climbing route on the Grand Teton in Grand Teton Nationa ...

in 1931. Of the other major peaks on the Teton Range, all were climbed by the late 1930s including Mount Moran in 1922 and Mount Owen in 1930 by Fritiof Fryxell

Fritiof M. Fryxell (April 27, 1900 – December 19, 1986) was an American educator, geologist and mountain climber, best known for his research and writing on the Teton Range of Wyoming. Upon the establishment of Grand Teton National Park in ...

and others after numerous previous attempts had failed. Both Middle and South Teton

South Teton () is the fifth-highest peak in the Teton Range, Grand Teton National Park, in the U.S. state of Wyoming. The peak is south of Middle Teton and just west of Cloudveil Dome and is part of the Cathedral Group of high Teton peaks. The T ...

were first climbed on the same day, August 29, 1923, by a group of climbers led by Albert R. Ellingwood. New routes on the peaks were explored as safety equipment and skills improved and eventually climbs rated at above 5.9 on the Yosemite Decimal System

The Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) is a three-part system used for rating the difficulty of walks, hikes, and climbs, primarily used by mountaineers in the United States and Canada. It was first devised by members of the Sierra Club in Southern Cal ...

difficulty scale were established on Grand Teton. The classic climb following the route first pioneered by Owen, known as the Owen-Spalding route, is rated at 5.4 due to a combination of concerns beyond the gradient alone. Rock climbing

Rock climbing is a sport in which participants climb up, across, or down natural rock formations. The goal is to reach the summit of a formation or the endpoint of a usually pre-defined route without falling. Rock climbing is a physically and ...

and bouldering

Bouldering is a form of free climbing that is performed on small rock formations or artificial rock walls without the use of ropes or harnesses. While bouldering can be done without any equipment, most climbers use climbing shoes to help se ...

had become popular in the park by the mid 20th century. In the late 1950s, gymnast John Gill John Gill may refer to:

Sports

*John Gill (cricketer) (1854–1888), New Zealand cricketer

*John Gill (coach) (1898–1997), American football coach

*John Gill (footballer, born 1903), English professional footballer

*John Gill (American football) ...

came to the park and started climbing large boulders near Jenny Lake

Jenny Lake is located in Grand Teton National Park in the U.S. state of Wyoming. The lake was formed approximately 12,000 years ago by glaciers pushing rock debris which carved Cascade Canyon during the last glacial maximum, forming a terminal m ...

. Gill approached climbing from a gymnastics perspective and while in the Tetons became the first known climber in history to use gymnastic chalk to improve handholds and to keep hands dry while climbing. During the latter decades of the 20th century, extremely difficult cliffs were explored including some in Death Canyon, and by the mid-1990s, 800 different climbing routes had been documented for the various peaks and canyon cliffs.

Park management

United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the mana ...

and manages both Grand Teton National Park and the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway. Grand Teton National Park has an average of 100 permanent and 180 seasonal employees. The park also manages 27 concession contracts that provide services such as lodging, restaurants, mountaineering guides, dude ranching, fishing and a boat shuttle on Jenny Lake. The National Park Service works closely with other federal agencies such as the U.S. Forest Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is an agency within the United States Department of the Interior dedicated to the management of fish, wildlife, and natural habitats. The mission of the agency is "working with othe ...

, the Bureau of Reclamation

The Bureau of Reclamation, and formerly the United States Reclamation Service, is a federal agency under the U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees water resource management, specifically as it applies to the oversight and opera ...

, and also, in consequence of Jackson Hole Airport's presence in the park, the Federal Aviation Administration

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the largest transportation agency of the U.S. government and regulates all aspects of civil aviation in the country as well as over surrounding international waters. Its powers include air traffic m ...

. Initial construction of the airstrip north of the town of Jackson was completed in the 1930s. When Jackson Hole National Monument was designated, the airport was inside it. After the monument and park were combined, the Jackson Hole Airport became the only commercial airport within an American national park. Jackson Hole Airport has some of the strictest noise abatement

Noise control or noise mitigation is a set of strategies to reduce noise pollution or to reduce the impact of that noise, whether outdoors or indoors.

Overview

The main areas of noise mitigation or abatement are: transportation noise control, ...

regulations of any airport in the U.S. The airport has night flight curfews and overflight restrictions, with pilots being expected to approach and depart the airport along the east, south or southwest flight corridors. As of 2010, 110 privately owned property inholding

An inholding is privately owned land inside the boundary of a national park, national forest, state park, or similar publicly owned, protected area. In-holdings result from private ownership of lands predating the designation of the park or fores ...

s, many belonging to the state of Wyoming, are located within Grand Teton National Park. Efforts to purchase or trade these inholdings for other federal lands are ongoing and through partnerships with other entities, 10 million dollars is hoped to be raised to acquire private inholdings by 2016.

In December 2016 the Antelope Flats Parcel consisting of (owned by the State of Wyoming as part of state school trust lands) was purchased and transferred to Grand Teton National Park. The purchase price amounted to 46 million dollars ($23 million allocated from the Land and Water Conservation Fund and the last $23 million was raised in private funds from 5,421 donors). The proceeds of the sale will benefit Wyoming Public Schools. Grand Teton National Park is still in negotiations for the purchase of the Kelly Parcel which totals an additional 640 acres from Wyoming. Moulton Ranch Cabins, a inholding along the historic Mormon Row was sold to the Grand Teton National Park Foundation in 2018. In 2020 the National Park Service in partnership with the Conservation Fund acquired a parcel located within Grand Teton National Park. This parcel is located near the Granite Canyon Entrance Station.

Geography

]

Grand Teton National Park is located in the northwestern region of the U.S. state of Wyoming. To the north the park is bordered by the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway, which is administered by Grand Teton National Park. The scenic highway with the same name passes from the southern boundary of Grand Teton National Park to West Thumb in Yellowstone National Park. Grand Teton National Park covers approximately , while the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway includes . Most of the Jackson Hole valley and virtually all the major mountain peaks of the Teton Range are within the park. The

]

Grand Teton National Park is located in the northwestern region of the U.S. state of Wyoming. To the north the park is bordered by the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway, which is administered by Grand Teton National Park. The scenic highway with the same name passes from the southern boundary of Grand Teton National Park to West Thumb in Yellowstone National Park. Grand Teton National Park covers approximately , while the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway includes . Most of the Jackson Hole valley and virtually all the major mountain peaks of the Teton Range are within the park. The Jedediah Smith Wilderness

The Jedediah Smith Wilderness is located in the U.S. state of Wyoming. Designated wilderness by Congress in 1984, Jedediah Smith Wilderness is within Caribou-Targhee National Forest and borders Grand Teton National Park. Spanning along the wester ...

of Caribou-Targhee National Forest lies along the western boundary and includes the western slopes of the Teton Range. To the northeast and east lie the Teton Wilderness

Teton Wilderness is located in Wyoming, United States. Created in 1964, the Teton Wilderness is located within Bridger-Teton National Forest and consists of 585,238 acres (2,370 km2). The wilderness is bordered on the north by Yellowstone Nat ...

and Gros Ventre Wilderness

The Gros Ventre Wilderness ( ) is located in Bridger-Teton National Forest in the U.S. state of Wyoming. Most of the Gros Ventre Range is located within the wilderness.

U.S. Wilderness Areas do not allow motorized or mechanized vehicles, incl ...

of Bridger-Teton National Forest. The National Elk Refuge is to the southeast, and migrating herds of elk winter there. Privately owned land borders the park to the south and southwest. Grand Teton National Park, along with Yellowstone National Park, surrounding National Forests and related protected areas constitute the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) is one of the last remaining large, nearly intact ecosystems in the northern temperate zone of the Earth. It is located within the northern Rocky Mountains, in areas of northwestern Wyoming, southwestern M ...

. The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem spans portions of three states and is one of the largest intact mid-latitude

The middle latitudes (also called the mid-latitudes, sometimes midlatitudes, or moderate latitudes) are a spatial region on Earth located between the Tropic of Cancer (latitudes 23°26'22") to the Arctic Circle (66°33'39"), and Tropic of Capric ...

ecosystems remaining on Earth. By road, Grand Teton National Park is from Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

, Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

and from Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

.

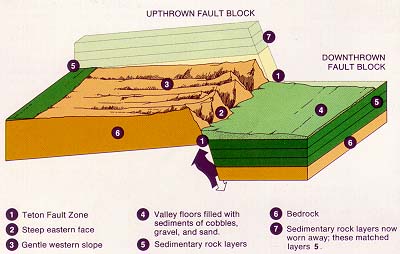

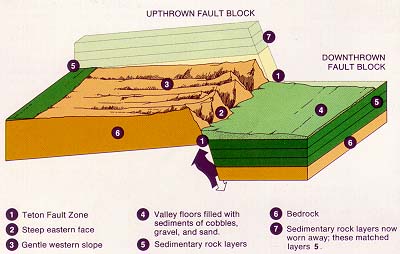

Teton Range

The youngest mountain range in theRocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

, the Teton Range began forming between 6 and 9 million years ago. It runs roughly north to south and rises from the floor of Jackson Hole without any foothills along a by wide active fault-block mountain

Fault blocks are very large blocks of rock, sometimes hundreds of kilometres in extent, created by tectonic and localized stresses in Earth's crust. Large areas of bedrock are broken up into blocks by faults. Blocks are characterized by relat ...

front. The range tilts westward, rising abruptly above Jackson Hole valley which lies to the east but more gradually into Teton Valley to the west. A series of earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

s along the Teton Fault

The Teton fault is a normal fault located in northwestern Wyoming. The fault has a length of 44 miles (70 km) and runs along the eastern base of the Teton Range. Vertical movement on the fault has caused the dramatic topography of the Teton R ...

slowly displaced the western side of the fault upward and the eastern side of the fault downward at an average of of displacement every 300–400 years. Most of the displacement of the fault occurred in the last 2 million years. While the fault has experienced up to 7.5-earthquake magnitude

Seismic magnitude scales are used to describe the overall strength or "size" of an earthquake. These are distinguished from seismic intensity scales that categorize the intensity or severity of ground shaking (quaking) caused by an earthquake at ...

events since it formed, it has been relatively quiescent during historical periods, with only a few 5.0-magnitude or greater earthquakes known to have occurred since 1850.

In addition to Grand Teton, another nine peaks are over above

In addition to Grand Teton, another nine peaks are over above sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

. Eight of these peaks between Avalanche

An avalanche is a rapid flow of snow down a slope, such as a hill or mountain.

Avalanches can be set off spontaneously, by such factors as increased precipitation or snowpack weakening, or by external means such as humans, animals, and earth ...

and Cascade Canyon

Cascade Canyon is located in Grand Teton National Park, in the U.S. state of Wyoming. The canyon was formed by glaciers which retreated at the end of the last glacial maximum approximately 15,000 years ago. Today, Cascade Canyon has numerous ...

s make up the often-photographed Cathedral Group

The Cathedral Group is the group of the tallest mountains of the Teton Range, all of which are located in Grand Teton National Park in the U.S. state of Wyoming. The Cathedral Group are classic alpine peaks, with pyramidal shapes caused by glac ...

. The most prominent peak north of Cascade Canyon is the monolithic Mount Moran

Mount Moran () is a mountain in Grand Teton National Park of western Wyoming, USA. The mountain is named for Thomas Moran, an American western frontier landscape artist. Mount Moran dominates the northern section of the Teton Range rising above ...

() which rises above Jackson Lake. To the north of Mount Moran, the range eventually merges into the high altitude Yellowstone Plateau

The Yellowstone Plateau Volcanic Field, also known as the Yellowstone Supervolcano or the Yellowstone Volcano, is a complex volcano, volcanic plateau and volcanic field located mostly in the western U.S. state of Wyoming but also stretches into I ...

. South of the central Cathedral Group the Teton Range tapers off near Teton Pass and blends into the Snake River Range.

West to east trending canyons provides easier access by foot into the heart of the range as no vehicular roads traverse the range except at Teton Pass, which is south of the park. Carved by a combination of glacier activity as well as numerous streams, the canyons are at their lowest point along the eastern margin of the range at Jackson Hole. Flowing from higher to lower elevations, the glaciers created more than a dozen U-shaped valley

U-shaped valleys, also called trough valleys or glacial troughs, are formed by the process of glaciation. They are characteristic of mountain glaciation in particular. They have a characteristic U shape in cross-section, with steep, straight s ...

s throughout the range. Cascade Canyon is sandwiched between Mount Owen and Teewinot Mountain

Teewinot Mountain () is the sixth highest peak in the Teton Range, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. The name of the mountain is derived from the Shoshone Native American word meaning "many pinnacles". The peak is northeast of the Grand Teton, ...

to the south and Symmetry Spire to the north and is situated immediately west of Jenny Lake. North to south, Webb

Webb most often refers to James Webb Space Telescope which is named after James E. Webb, second Administrator of NASA.

It may also refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Webb Glacier (South Georgia)

* Webb Glacier (Victoria Land)

* Webb Névé, Victor ...

, Moran, Paintbrush

A paintbrush is a brush used to apply paint or ink. A paintbrush is usually made by clamping bristles to a handle with a ferrule. They are available in various sizes, shapes, and materials. Thicker ones are used for filling in, and thinner one ...

, Cascade, Death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

and Granite Canyon

Granite Canyon is located in Grand Teton National Park, in the U. S. state of Wyoming. The canyon was formed by glaciers which retreated at the end of the last glacial maximum approximately 15,000 years ago, leaving behind a U-shaped valley. The ...

s slice through Teton Range.

Jackson Hole

Jackson Hole is a by wide

Jackson Hole is a by wide graben

In geology, a graben () is a depressed block of the crust of a planet or moon, bordered by parallel normal faults.

Etymology

''Graben'' is a loan word from German, meaning 'ditch' or 'trench'. The word was first used in the geologic contex ...

valley with an average elevation of , its lowest point is near the southern park boundary at . The valley sits east of the Teton Range and is vertically displaced downward , making the Teton Fault and its parallel twin on the east side of the valley normal faults with the Jackson Hole block being the hanging wall and the Teton Mountain block being the footwall. Grand Teton National Park contains the major part of both blocks. Erosion of the range provided sediment in the valley so the topographic relief is only . Jackson Hole is comparatively flat, with only a modest increase in altitude south to north; however, a few isolated butte

__NOTOC__

In geomorphology, a butte () is an isolated hill with steep, often vertical sides and a small, relatively flat top; buttes are smaller landforms than mesas, plateaus, and tablelands. The word ''butte'' comes from a French word mea ...

s such as Blacktail Butte

Blacktail Butte () is a butte mountain landform rising from Jackson Hole valley in Grand Teton National Park in the U.S. state of Wyoming. Blacktail Butte was originally named ''Upper Gros Ventre Butte'' in an early historical survey conducted by ...

and hills including Signal Mountain dot the valley floor. In addition to a few outcroppings, the Snake River

The Snake River is a major river of the greater Pacific Northwest region in the United States. At long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, in turn, the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. The Snake ...

has eroded terraces into Jackson Hole. Southeast of Jackson Lake, glacial depressions known as kettles are numerous. The kettles were formed when ice situated under gravel outwash from ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are in Antarctica and Greenland; during the Last Glacial Period at Las ...

s melted as the glaciers retreated.

Lakes and rivers

Most of the lakes in the park were formed by glaciers and the largest of these lakes are located at the base of the Teton Range. In the northern section of the park lies Jackson Lake, the largest lake in the park at in length, wide and deep. Though Jackson Lake is natural, the Jackson Lake Dam was constructed at its outlet before the creation of the park, and the lake level was raised almost consequently. East of the

Most of the lakes in the park were formed by glaciers and the largest of these lakes are located at the base of the Teton Range. In the northern section of the park lies Jackson Lake, the largest lake in the park at in length, wide and deep. Though Jackson Lake is natural, the Jackson Lake Dam was constructed at its outlet before the creation of the park, and the lake level was raised almost consequently. East of the Jackson Lake Lodge

Jackson Lake Lodge is located near Moran in Grand Teton National Park, in the U.S. state of Wyoming. The lodge has 385 rooms, a restaurant, conference rooms, and offers numerous recreational opportunities. The lodge is owned by the National Park ...

lies Emma Matilda and Two Ocean Lake

Two Ocean Lake is located in Grand Teton National Park, in the U. S. state of Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and ...

s. South of Jackson Lake, Leigh

Leigh may refer to:

Places In England

Pronounced :

* Leigh, Greater Manchester, Borough of Wigan

** Leigh (UK Parliament constituency)

* Leigh-on-Sea, Essex

Pronounced :

* Leigh, Dorset

* Leigh, Gloucestershire

* Leigh, Kent

* Leigh, Staf ...

, Jenny

Jenny may refer to:

* Jenny (given name), a popular feminine name and list of real and fictional people

* Jenny (surname), a family name

Animals

* Jenny (donkey), a female donkey

* Jenny (gorilla), the oldest gorilla in captivity at the time of ...

, Bradley

Bradley is an English surname derived from a place name meaning "broad wood" or "broad meadow" in Old English.

Like many English surnames Bradley can also be used as a given name and as such has become popular.

It is also an Anglicisation of t ...

, Taggart

''Taggart'' is a Scottish detective fiction television programme created by Glenn Chandler, who wrote many of the episodes, and made by STV Studios for the ITV network. It originally ran as the miniseries "Killer" from 6 until 20 Septembe ...

and Phelps Lakes rest at the outlets of the canyons which lead into the Teton Range. Within the Teton Range, small alpine lakes in cirque

A (; from the Latin word ') is an amphitheatre-like valley formed by glacial erosion. Alternative names for this landform are corrie (from Scottish Gaelic , meaning a pot or cauldron) and (; ). A cirque may also be a similarly shaped landform ...

s are common, and there are more than 100 scattered throughout the high country. Lake Solitude, located at an elevation of , is in a cirque at the head of the North Fork of Cascade Canyon. Other high-altitude lakes can be found at over in elevation and a few, such as Icefloe Lake

Icefloe Lake is located in Grand Teton National Park, in the U. S. state of Wyoming. Icefloe Lake is west of Middle Teton and the same distance from South Teton

South Teton () is the fifth-highest peak in the Teton Range, Grand Teton National Par ...

, remain ice-clogged for much of the year. The park is not noted for large waterfalls; however, Hidden Falls just west of Jenny Lake is easy to reach after a short hike.

From its headwaters on Two Ocean Plateau in Yellowstone National Park, the Snake River flows north to south through the park, entering Jackson Lake near the boundary of Grand Teton National Park and John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway. The Snake River then flows through the spillways of the Jackson Lake Dam and from there southward through Jackson Hole, exiting the park just west of the Jackson Hole Airport. The largest lakes in the park all drain either directly or by tributary streams into the Snake River. Major tributaries which flow into the Snake River include Pacific Creek and Buffalo Fork near Moran and the Gros Ventre River

The Gros Ventre River (''pronounced GROW-VAUNT'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 4, 2011 tributary of the Snake River in the state of Wyoming, USA. During ...

at the southern border of the park. Through the comparatively level Jackson Hole valley, the Snake River descends an average of , while other streams descending from the mountains to the east and west have higher gradients due to increased slope. The Snake River creates braids

A braid (also referred to as a plait) is a complex structure or pattern formed by interlacing two or more strands of flexible material such as textile yarns, wire, or hair.

The simplest and most common version is a flat, solid, three-strande ...

and channels in sections where the gradients are lower and in steeper sections, erodes and undercuts the cobblestone terraces once deposited by glaciers.

Glaciation

The major peaks of the Teton Range were carved into their current shapes by long-vanished

The major peaks of the Teton Range were carved into their current shapes by long-vanished glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s. Commencing 250,000–150,000 years ago, the Tetons went through several periods of glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

with some areas of Jackson Hole covered by glaciers thick. This heavy glaciation is unrelated to the uplift of the range itself and is instead part of a period of global cooling known as the Quaternary glaciation