Georgia during Reconstruction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At the end of the

, ''New Georgia Encyclopedia''. The state government subsidized construction of numerous new railroad lines. White farmers turned to cotton as a cash crop, often using commercial fertilizers to make up for the poor soils they owned. The coastal rice plantations never recovered from the war. Bartow County was representative of the postwar difficulties. Property destruction and the deaths of a third of the soldiers caused financial and social crises; recovery was delayed by repeated crop failures. The Freedmen's Bureau agents were unable to give blacks the help they needed.

As directed by Congress, General John Pope registered Georgia's eligible white and black voters, 95,214 and 93,457 respectively. From October 29 through November 2, 1867, elections were held for delegates to a new constitutional convention, held in

As directed by Congress, General John Pope registered Georgia's eligible white and black voters, 95,214 and 93,457 respectively. From October 29 through November 2, 1867, elections were held for delegates to a new constitutional convention, held in

During the tenure of Amos T. Akerman (1821–1880) as Attorney General of the United States from 1870 to 1871, thousands of indictments were brought against Klansmen in an effort to enforce the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and the Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871. Akerman, though born in the North, moved to Georgia after college and owned slaves; he fought for the Confederacy and became a

During the tenure of Amos T. Akerman (1821–1880) as Attorney General of the United States from 1870 to 1871, thousands of indictments were brought against Klansmen in an effort to enforce the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and the Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871. Akerman, though born in the North, moved to Georgia after college and owned slaves; he fought for the Confederacy and became a

online

* Hébert, Keith S. "The Bitter Trial of Defeat and Emancipation: Reconstruction in Bartow County, Georgia, 1865-1872," ''Georgia Historical Quarterly'' (2008) 92#1 pp 65–92. * Hogan, Richard. "Resisting Redemption," ''Social Science History'' (2011) 35#2 133-166. statistical analysis of votes in 1876 * * Nathans, Elizabeth Studley. ''Losing the Peace: Georgia Republicans and Reconstruction, 1865-1871'' (1969) *Reidy; Joseph P. ''From Slavery to Agrarian Capitalism in the Cotton Plantation South: Central Georgia, 1800–1880'' (University of North Carolina Press, 1992

online

* Rogers Jr., William Warren. ''A Scalawag in Georgia: Richard Whiteley and the Politics of Reconstruction'' (2008) * Schott, Thomas E. ''Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia: A Biography''. LSU Press, 1988. * Thompson, C. Mildred. ''Reconstruction In Georgia: Economic, Social, Political 1865-1872'' (19i5; 2010 reprint

excerpt and text searchfull text online free

* Thompson, William Y. ''Robert Toombs of Georgia.'' LSU Press, 1966. * Wallenstein; Peter. ''From Slave South to New South: Public Policy in Nineteenth-Century Georgia'' (University of North Carolina Press, 1987

online edition

* Wetherington, Mark V. ''Plain Folk's Fight: The Civil War and Reconstruction in Piney Woods Georgia'' (University of North Carolina Press, 2005) 383 pp

online review by Frank Byrne

* , from the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, the devastation and disruption in the state of Georgia were dramatic. Wartime damage, the inability to maintain a labor force without slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and miserable weather had a disastrous effect on agricultural production. The state's chief cash crop, cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

, fell from a high of more than 700,000 bales in 1860 to less than 50,000 in 1865, while harvests of corn and wheat were also meager."Reconstruction in Georgia", ''New Georgia Encyclopedia''. The state government subsidized construction of numerous new railroad lines. White farmers turned to cotton as a cash crop, often using commercial fertilizers to make up for the poor soils they owned. The coastal rice plantations never recovered from the war. Bartow County was representative of the postwar difficulties. Property destruction and the deaths of a third of the soldiers caused financial and social crises; recovery was delayed by repeated crop failures. The Freedmen's Bureau agents were unable to give blacks the help they needed.

Wartime Reconstruction, or "

Forty acres and a mule

Forty acres and a mule was part of Special Field Orders No. 15, a wartime order proclaimed by Union General William Tecumseh Sherman on January 16, 1865, during the American Civil War, to allot land to some freed families, in plots of land no la ...

"

At the beginning of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, Georgia had over 460,000 freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

. In January 1865, in Savannah, William T. Sherman

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

issued Special Field Orders, No. 15, authorizing federal authorities to confiscate abandoned plantation lands in the Sea Islands

The Sea Islands are a chain of tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean coast of the Southeastern United States. Numbering over 100, they are located between the mouths of the Santee and St. Johns Rivers along the coast of South Caroli ...

, whose owners had fled with the advance of his army, and redistribute them to former slaves. Redistributing 400,000 acres (1,600 km²) in coastal Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

to 40,000 freed slaves in forty-acre plots, this order was intended to provide for the thousands of escaped slaves who had been following his army during his March to the Sea. Shortly after Sherman issued his order, Congressional leaders convinced President Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

to establish the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands in March 1865. The Freedmen's Bureau, as it came to be called, was authorized to give legal title for plots of land to freedmen and white Southern Unionists. Rev. Tunis Campbell

Rev. Tunis Gulic Campbell Sr. (April 1, 1812 – December 4, 1891), called "the oldest and best known clergyman in the African Methodist Church", served as a voter registration organizer, Justice of the Peace, a delegate to the Georgia Constit ...

, a free Northern black missionary, was appointed to supervise land claims and resettlement in Georgia. Over the objections of Freedmen's Bureau chief General Oliver O. Howard, President Andrew Johnson revoked Sherman's directive in the fall of 1865, after the war had ended, returning these lands to the planters who had previously owned them, and expelling their new Black farmers.

Presidential Reconstruction

On Georgia's farms and plantations, wartime destruction, the inability to maintain a labor force without slavery, and miserable weather had a disastrous effect on agricultural production and the regional economy. The state's chief money crop, cotton, fell from a high of more than 700,000 bales in 1860 to less than 50,000 in 1865, while harvests of corn and wheat were also meager. After the war, new railroad lines and commercial fertilizers created conditions that spurred increased cotton production in Georgia's upcountry, but coastal rice plantations never recovered. Many emancipated slaves flocked to towns, where they encountered overcrowding and food shortages, with significant numbers dying from epidemic diseases. The Freedmens Bureau returned much of the prewar black labor back to the field, mediating a contract-labor system between white landowners and their black workers, who often consisted of the landowners' former slaves. Taking advantage of educational opportunities available for the first time, within a year, at least 8,000 former slaves were attending schools in Georgia, established with northern philanthropy. In mid-June 1865, Andrew Johnson appointed as provisional governor his friend and fellow Unionist,James Johnson James Johnson may refer to:

Artists, actors, authors, and musicians

*James Austin Johnson (born 1989), American comedian & actor, ''Saturday Night Live'' cast member

*James B. Johnson (born 1944), author of science nonfiction novels

*James P. John ...

, a Columbus lawyer who sat out the war. Delegates to a constitutional convention, meeting in Milledgeville in October, abolished slavery, repealed the Ordinance of Secession, and repudiated the Confederacy debt. The General Assembly, while alone among ex-Confederate states in refraining from enacting a harsh Black Code, assumed newly freed slaves would enjoy only the limited freedom of the prewar period's 'free persons of color,' and enacted a constitutional amendment outlawing interracial marriage. On November 15, 1865, Georgia elected a new governor, congressmen, and state legislators. Voters repudiated most Unionist candidates, electing to office many ex-Confederates, although several of these – including the new governor, former Whig Charles J. Jenkins – initially opposed secession. The new state legislature created a political firestorm in Washington by electing to the Senate Alexander Stephens

Alexander Hamilton Stephens (February 11, 1812 – March 4, 1883) was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865, and later as the 50th governor of Georgia from 1882 until his death in 1 ...

and Herschel Johnson, who had been the Vice-President and a Senator of the Confederacy, respectively. Neither Stephens or Johnson, nor any of Georgia's newly-selected U.S. House

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

delegation, were inaugurated or allowed to take their seats, as the federal government, at the time, refused to accept into the congregation persons implicated so heavily with the Confederacy's secession and rebellion, or to enable them to wield federal-level political influence.

Congressional Reconstruction

Andrew Johnson's decision in August 1866 to restore the former Confederate states to the Union was criticized by theRadical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

in Congress, who, in March 1867, passed the First Reconstruction Act, placing the South under military occupation. Georgia, along with Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

and Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, became part of the Third Military District

The Third Military District of the U.S. Army was one of five temporary administrative units of the U.S. War Department that existed in the American South. The district was stipulated by the Reconstruction Acts during the Reconstruction period fo ...

, under the command of General John Pope. Radical Republicans also passed an ironclad oath which prevented ex-Confederates from voting or holding office, replacing them with a coalition of freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

, carpetbaggers

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the l ...

, and scalawags

In United States history, the term scalawag (sometimes spelled scallawag or scallywag) referred to white Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts after the conclusion of the American Civil War.

As with the term '' carpet ...

, mostly former Whigs who had opposed secession.

As directed by Congress, General John Pope registered Georgia's eligible white and black voters, 95,214 and 93,457 respectively. From October 29 through November 2, 1867, elections were held for delegates to a new constitutional convention, held in

As directed by Congress, General John Pope registered Georgia's eligible white and black voters, 95,214 and 93,457 respectively. From October 29 through November 2, 1867, elections were held for delegates to a new constitutional convention, held in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

rather than the state capital of Milledgeville, to prevent the interference of the ex-Confederates. In January 1868, after Georgia's first elected governor after the end of the war, Charles Jenkins, refused to authorize state funds for the racially integrated state constitutional convention, his government was dissolved by Pope's successor General George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

and replaced by a military governor. This counter-coup galvanized white resistance to the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, fueling the growth of the Ku Klux Klan. Grand Wizard Nathan Bedford Forrest visited Atlanta several times in early 1868 to help set up the organization. In Georgia, the Klan was led by John Brown Gordon

John Brown Gordon () was an attorney, a slaveholding plantation owner, general in the Confederate States Army, and politician in the postwar years. By the end of the Civil War, he had become "one of Robert E. Lee's most trusted generals."

Af ...

, a charismatic General in Lee's Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

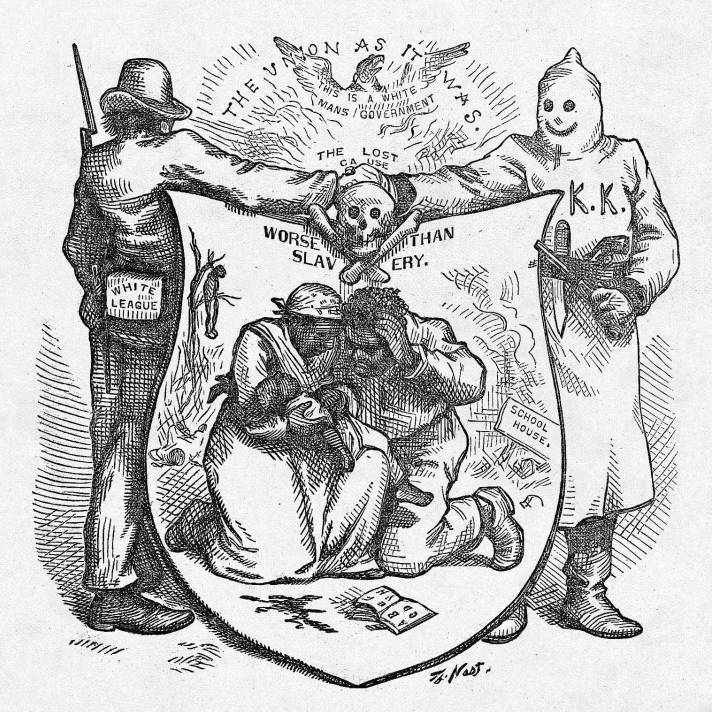

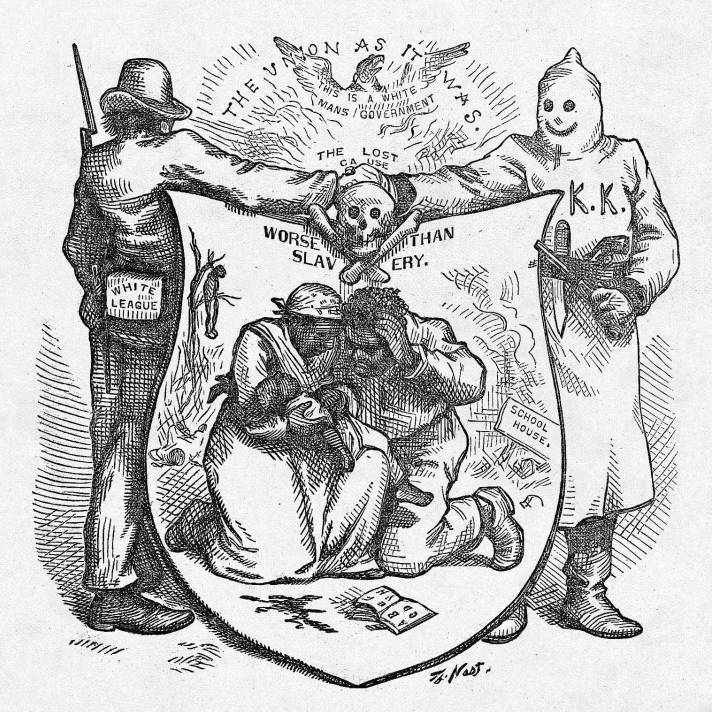

. Freedmen's Bureau agents reported 336 cases of murder or assault with intent to kill against freedmen across the state from January 1 through November 15 of 1868.

In July 1868, Georgia was readmitted to the Union, the newly elected General Assembly ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, and a Republican governor, New York native Rufus Bullock, was inaugurated. The state's Democrats—including former Confederate leaders Robert Toombs

Robert Augustus Toombs (July 2, 1810 – December 15, 1885) was an American politician from Georgia, who was an important figure in the formation of the Confederacy. From a privileged background as a wealthy planter and slaveholder, Toomb ...

and Howell Cobb

Howell Cobb (September 7, 1815 – October 9, 1868) was an American and later Confederate political figure. A southern Democrat, Cobb was a five-term member of the United States House of Representatives and the speaker of the House from 184 ...

—denounced the policies of the Reconstruction in a mass rally in Atlanta, described as the largest in the state's history. The principal target of the rally, Joseph E. Brown

Joseph Emerson Brown (April 15, 1821 – November 30, 1894), often referred to as Joe Brown, was an American attorney and politician, serving as the 42nd Governor of Georgia from 1857 to 1865, the only governor to serve four terms. He also se ...

, Georgia's Governor under the Confederacy, who became a Republican and a delegate to the Chicago convention that had nominated Union general Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

for president, declared that although the state, reluctantly, had given Blacks the vote, as they were not citizens the state's constitution did not allow them to hold office. In September, white Republicans joined with the Democrats in expelling the Black senators and Black representatives in the lower house from the General Assembly. While Governor Bullock gave the figure of 28, the monument ''Expelled Because of Their Color'', on the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta, identifies 33.

A week later, in the southwest Georgia town of Camilla, white residents attacked a black Republican rally, killing twelve people in the Camilla massacre

The Camilla massacre took place in Camilla, Georgia, on Saturday, September 19, 1868. African Americans had been given the right to vote in Georgia's 1868 state constitution, which had passed in April, and in the months that followed, whites acros ...

.

These developments led to calls for Georgia's return to military rule, which increased after Georgia was one of only two ex-Confederate states to vote against Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

* Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

* Grant, Inyo County, ...

in the election of 1868. (Louisiana was the other; Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia did not vote because they had not yet been readmitted to the Union.) The expelled black legislators, led by Rev. Tunis Campbell

Rev. Tunis Gulic Campbell Sr. (April 1, 1812 – December 4, 1891), called "the oldest and best known clergyman in the African Methodist Church", served as a voter registration organizer, Justice of the Peace, a delegate to the Georgia Constit ...

and Henry McNeill Turner, lobbied in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

for federal intervention. In March 1869 Governor Bullock, hoping to prolong Reconstruction, "engineered" Georgia's refusal to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave Blacks the vote. The same month the U.S. Congress once again barred Georgia's representatives from their seats, causing military rule to resume in December 1869. In January 1870, Gen. Alfred H. Terry, the final commanding general of the Third District, purged the General Assembly's ex-Confederates, replaced them with the Republican runners-up, and reinstated the expelled black legislators, creating a large Republican majority in the legislature. On February 2, 1870, Georgia ratified the Fifteenth Amendment.

Amos T. Akerman

scalawag

In United States history, the term scalawag (sometimes spelled scallawag or scallywag) referred to white Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts after the conclusion of the American Civil War.

As with the term ''carpetb ...

during Reconstruction, speaking out for civil rights for Blacks. As U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

under President Grant, he became the first ex-Confederate to reach the cabinet. Akerman was unafraid of the Klan and committed to protecting the lives and civil rights of Blacks. To bolster Akerman's investigation, President Grant sent in Secret Service agents from the Justice Department to infiltrate the Klan to gather evidence for prosecution. The investigations revealed that many whites actively participated in Klan activities. With this evidence, Grant issued a Presidential proclamation to disarm and remove the Klan's notorious white robe and hood disguises. When the Klan ignored the proclamation, Grant sent Federal troops to nine South Carolina counties to put down the violent activities of the Klan. Grant teamed Akerman up with another reformer in 1870, a native Kentuckian

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, the first Solicitor General Benjamin Bristow

Benjamin Helm Bristow (June 20, 1832 – June 22, 1896) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 30th U.S. Treasury Secretary and the first Solicitor General.

A Union military officer, Bristow was a Republican Party reformer and ...

, and the duo went on to prosecute thousands of Klan members and brought a brief quiet period of two years (1870–1872) in the turbulent Reconstruction era.

End of Reconstruction

Georgia Democrats despised the ' Carpetbagger' administration of Rufus Bullock, accusing two of his friends, Foster Blodgett, superintendent of the state'sWestern and Atlantic Railroad

The Western & Atlantic Railroad of the State of Georgia (W&A) is a railroad owned by the State of Georgia and currently leased by CSX, which CSX operates in the Southeastern United States from Atlanta, Georgia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee.

It was fo ...

, and Hannibal I. Kimball, owner of the Atlanta opera house where the state legislature met, of embezzling state funds. His efforts to prolong military rule caused considerable divisions in the states party, while black politicians complained that they did not receive an adequate share of patronage. In February 1870 the newly constituted legislature ratified the Fifteenth Amendment and chose new Senators to send to Washington. On July 15, Georgia became the last former Confederate state readmitted into the Union. The Democrats subsequently won commanding majorities in both houses of the General Assembly. Governor Rufus Bullock fled the state in order to avoid impeachment. With the voting restrictions against former Confederates removed, Democrat and ex-Confederate Colonel James Milton Smith

James Milton Smith (October 24, 1823November 25, 1890) was a Confederate infantry colonel in the American Civil War, as well as a post-war Governor of Georgia.

Early life

Smith was born in Twiggs County, Georgia and was educated at the Cullo ...

was elected to complete Bullock's term. By January 1872 Georgia was fully under the control of the Redeemers

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party. They sought to regain their political power and enforce ...

, the state's resurgent white conservative Democrats.

The so-called Redeemers used terrorism to strengthen their rule. The expelled African American legislators were particular targets for their violence. African American legislator Abram Colby was pulled out of his home by a mob and given 100 lashes with a whip. His colleague Abram Turner was murdered. Other African American lawmakers were threatened and attacked.See Drago p. 146 (in sources below) for details.

Notes

Georgia was re-admitted to the Union twiceFurther reading

* Cimbala, Paul A. ''Under the Guardianship of the Nation: The Freedmen's Bureau and the Reconstruction of Georgia, 1865-1870'' (1998) ** Smith, John David. "'The Work it Did Not Do Because it Could Not': Georgia and the 'New' Freedmen's Bureau Historiography," ''Georgia Historical Quarterly'' (1998) 82#2 pp 331–349; review essay of Cimbala (1998) * * Farmer-Kaiser, Mary. "'Are they not in some sorts vagrants?': Gender and the Efforts of the Freedmen's Bureau to Combat Vagrancy in the Reconstruction South," ''Georgia Historical Quarterly'' (2004) 88#1 pp 25–49. *Hahn Steven. ''The Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia Upcountry, 1850–1890.'' Oxford University Press, 1983. * Hamilton, Peter Joseph. ''The Reconstruction Period''] (1906), full length history of era;Dunning School

The Dunning School was a historiographical school of thought regarding the Reconstruction period of American history (1865–1877), supporting conservative elements against the Radical Republicans who introduced civil rights in the South. It was na ...

approach; 570 pp; ch 12 on Georgionline

* Hébert, Keith S. "The Bitter Trial of Defeat and Emancipation: Reconstruction in Bartow County, Georgia, 1865-1872," ''Georgia Historical Quarterly'' (2008) 92#1 pp 65–92. * Hogan, Richard. "Resisting Redemption," ''Social Science History'' (2011) 35#2 133-166. statistical analysis of votes in 1876 * * Nathans, Elizabeth Studley. ''Losing the Peace: Georgia Republicans and Reconstruction, 1865-1871'' (1969) *Reidy; Joseph P. ''From Slavery to Agrarian Capitalism in the Cotton Plantation South: Central Georgia, 1800–1880'' (University of North Carolina Press, 1992

online

* Rogers Jr., William Warren. ''A Scalawag in Georgia: Richard Whiteley and the Politics of Reconstruction'' (2008) * Schott, Thomas E. ''Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia: A Biography''. LSU Press, 1988. * Thompson, C. Mildred. ''Reconstruction In Georgia: Economic, Social, Political 1865-1872'' (19i5; 2010 reprint

excerpt and text search

* Thompson, William Y. ''Robert Toombs of Georgia.'' LSU Press, 1966. * Wallenstein; Peter. ''From Slave South to New South: Public Policy in Nineteenth-Century Georgia'' (University of North Carolina Press, 1987

online edition

* Wetherington, Mark V. ''Plain Folk's Fight: The Civil War and Reconstruction in Piney Woods Georgia'' (University of North Carolina Press, 2005) 383 pp

online review by Frank Byrne

* , from the

Dunning School

The Dunning School was a historiographical school of thought regarding the Reconstruction period of American history (1865–1877), supporting conservative elements against the Radical Republicans who introduced civil rights in the South. It was na ...

Historiography

* Davis, Robert Scott. "New Ideas from New Sources: Modern Research in Reconstruction, 1865-1876," ''Georgia Historical Quarterly'' (2009) 93#3 pp 291–306. * Smith, John David. "'The Work it Did Not Do Because it Could Not': Georgia and the 'New' Freedmen's Bureau Historiography," ''Georgia Historical Quarterly'' (1998) 82#2 pp 331–349; review essay of CimbalaPrimary sources

* {{Authority control History of Georgia (U.S. state) Reconstruction Era Ku Klux Klan in Georgia (U.S. state)