George Shelvocke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Shelvocke (baptised 1 April 167530 November 1742) was an English

Alongside the ''Success'', captained by

Alongside the ''Success'', captained by

"Uncovered: the Man Behind Coleridge's Ancient Mariner"

by Vanessa Thorpe (31 January 2010) in ''

Facsimile of first edition with engraved map and plates

of George Shelvocke's ''Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea'' (1726) from

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

officer and later privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

who in 1726 wrote ''A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea'' based on his exploits. It includes an account of how his second captain, Simon Hatley

Simon may refer to:

People

* Simon (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name Simon

* Simon (surname), including a list of people with the surname Simon

* Eugène Simon, French naturalist and the genus ...

, shot an albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pac ...

off Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

, an incident which provided the dramatic motive in Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lak ...

's poem ''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (originally ''The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere'') is the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1797–1798 and published in 1798 in the first edition of '' Lyrical Ball ...

''.

Early life and naval career

Born into a farming family inShropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

and christened at St Mary's, Shrewsbury, on 1 April 1675, Shelvocke joined the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

when he was fifteen years old. During two long wars with France he rose through the ranks to become a sailing master

The master, or sailing master, is a historical rank for a naval officer trained in and responsible for the navigation of a sailing vessel. The rank can be equated to a professional seaman and specialist in navigation, rather than as a militar ...

and finally second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

of a flagship serving under Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Dilkes in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. However, when war ended in 1713 he was beached without even half-pay Half-pay (h.p.) was a term used in the British Army and Royal Navy of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries to refer to the pay or allowance an officer received when in retirement or not in actual service.

Past usage United Kingdom

In the En ...

for support. By the time he was offered a commission as captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

of the privateering ship ''Speedwell'', he was living in poverty.

Privateering voyage

Alongside the ''Success'', captained by

Alongside the ''Success'', captained by John Clipperton

John Clipperton (1676 – June 1722) was an English privateer who fought against the Spanish in the 18th century. He was involved in two buccaneering expeditions to the South Pacific—the first led by William Dampier in 1703, and the second under ...

, the ''Speedwell'' was involved in a 1719 expedition to loot Spanish ships and settlements along the Pacific coast of the Americas. The English had just renewed hostilities with Spain in the War of the Quadruple Alliance, and the ships carried letters of marque which gave them official permission to wage war on the Spanish and keep the profits. Shelvocke broke away from Clipperton shortly after leaving British waters and appears to have avoided contact as much as possible for the rest of the voyage.

On 25 May 1720 the ''Speedwell'' was wrecked on the island of Más a Tierra in the Juan Fernández Archipelago. Shelvocke and his crew were maroon

Maroon ( US/ UK , Australia ) is a brownish crimson color that takes its name from the French word ''marron'', or chestnut. "Marron" is also one of the French translations for "brown".

According to multiple dictionaries, there are vari ...

ed there for five months but managed to build a 20-ton boat using some timbers and hardware salvaged from the wreck, in addition to wood obtained from locally felled trees. Leaving the island on 6 October, they transferred into their first prize, renamed the ''Happy Return'', and resumed privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

ing, despite the war having ended in February and rendered their letter of marque invalid. They continued up the coast of South America from Chile to Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

, capturing more vessels along the way, before crossing the Pacific to Macao

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a po ...

and returning to England in July 1722.

Later life

In England Shelvocke was arrested on charges offraud

In law, fraud is intentional deception to secure unfair or unlawful gain, or to deprive a victim of a legal right. Fraud can violate civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrator to avoid the fraud or recover monetary compen ...

at the instigation of the principal shareholders of the voyage, though he avoided conviction through out-of-court settlements with two of the complainants. They suspected, probably with reason, that he had failed to let them know about a significant portion of the loot obtained from the voyage, and planned to keep it for himself and other members of his crew. The self-justifying version of events given by Shelvocke in the book ''A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea'' was disputed by some who had accompanied him on that expedition, in particular by his captain of marines, William Betagh.

Shelvocke nevertheless went on to re-establish his reputation and died on 30 November 1742 at the age of 67, a wealthy man as a result of his buccaneer

Buccaneers were a kind of privateers or free sailors particular to the Caribbean Sea during the 17th and 18th centuries. First established on northern Hispaniola as early as 1625, their heyday was from the Restoration in 1660 until about 168 ...

ing activity. His chest tomb (since removed) in the churchyard of St Nicholas, Deptford, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, by the east wall eulogised "a gentleman of great abilities in his profession and allowed to have been one of the bravest and most accomplished seamen of his time." A wall tablet in the chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

...

commemorates his son, also George Shelvocke, who died in 1760 and accompanied his father on the journey round the world before becoming Secretary of the General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Before the Acts of Union 1707, it was the postal system of the Kingdom of England, established by Charles II in 1660. ...

and a Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

.

Influence on Coleridge

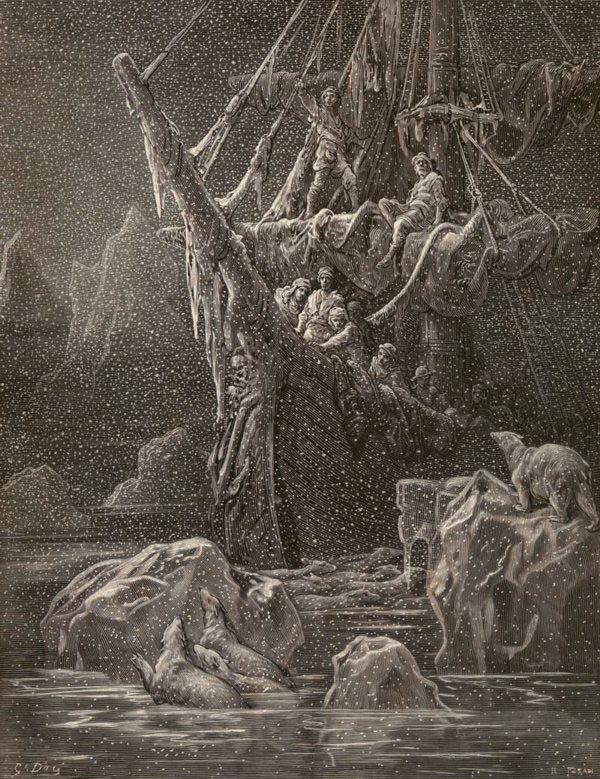

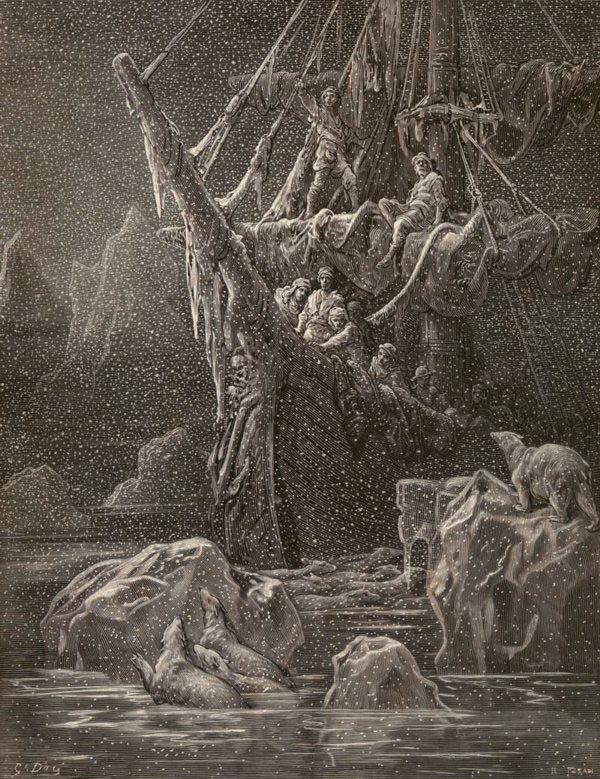

In his book Shelvocke described an event wherein his second captain,Simon Hatley

Simon may refer to:

People

* Simon (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name Simon

* Simon (surname), including a list of people with the surname Simon

* Eugène Simon, French naturalist and the genus ...

, shot a black albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pac ...

while the ''Speedwell'' was attempting to round Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

in severe storms. Hatley took the giant sea bird to be a bad omen, and hoped that by killing it he might bring about a break in the weather. Some seventy years later the episode would become the inspiration for the central plot device in Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lak ...

's narrative poem ''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (originally ''The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere'') is the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1797–1798 and published in 1798 in the first edition of '' Lyrical Ball ...

''. Coleridge's friend and fellow poet William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

shared the following reminiscences on the origins of the poem:

Much the greatest part of the story was Mr Coleridge's invention; but certain parts I myself suggested: for example, some crime was to be committed which should bring upon the old navigator, as Coleridge afterwards delighted to call him, the spectral persecution, as a consequence of that crime, and his own wanderings. I had been reading in Shelvock's ''Voyages'' a day or two before that while doubling Cape Horn they frequently saw albatrosses in that latitude, the largest sort of sea-fowl, some extending their wings twelve or fifteen feet. "Suppose," I said, "you represent him as having killed one of these birds on entering the South Sea, and that the tutelary spirits of those regions take upon them to avenge the crime. The incident was thought fit for the purpose and adopted accordingly."

Notes

References

* * * * * * *External links

"Uncovered: the Man Behind Coleridge's Ancient Mariner"

by Vanessa Thorpe (31 January 2010) in ''

The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

''

Facsimile of first edition with engraved map and plates

of George Shelvocke's ''Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea'' (1726) from

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shelvocke, George

1675 births

1742 deaths

18th-century English writers

Circumnavigators of the globe

English privateers

History of Baja California

Writers from Shropshire

Royal Navy officers

Freemasons of the Premier Grand Lodge of England

British military personnel of the War of the Spanish Succession

Military personnel from Shropshire