George Hirst (virologist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Keble Hirst,

(accessed February 21, 2013) After the

(accessed February 18, 2013) He also held a teaching position at the

(accessed January 18, 2013)

Hirst's earliest research, in the 1930s, was on

Hirst's earliest research, in the 1930s, was on

text

Wolfgang Joklik cites the discovery of hemagglutination as one of the "early epoch-making discoveries in virology," stating that it made influenza virus "the first mammalian virus whose replication could be studied biochemically." Although Hirst did not know this at the time, hemagglutination is caused by the influenza virus

Influenza hemagglutination inhibition assay (27 May 2009)

(accessed February 19, 2013)

He soon realised that the hemagglutination assay could easily be adapted to measure the levels of

He soon realised that the hemagglutination assay could easily be adapted to measure the levels of

text

HIA is "a powerful epidemiological tool," according to virologist

Hirst noticed that hemagglutination tended to wear off over time, and in 1942, he discovered that influenza virus has an intrinsic

Hirst noticed that hemagglutination tended to wear off over time, and in 1942, he discovered that influenza virus has an intrinsic

pdf

Laver G. "Influenza virus surface glycoproteins, haemagglutinin and neuraminidase: a personal account" in ''Influenza'' (CW Potter, ed.), p. 31 (''Perspectives in Medical Virology'' series) (Elsevier; 2002) () Like hemagglutinin, neuraminidase is essential for the influenza life cycle, being required for the progeny virus to leave the host cell. Neuraminidase is the target of the

pdf

In 1966, he was elected to membership of theNew York Academy of Medicine: Anniversary Discourse & Awards

(accessed February 21, 2013)

pdf

According to Kilbourne, he was very private person who did not seek publicity. His non-scientific pursuits included music – he was both a musician and a musicologist – gardening, and the appreciation of nature. Hirst married Charlotte Hart in 1937, and the couple had four sons and a daughter. In retirement he moved to

M.D.

Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated M.D., from the Latin ''Medicinae Doctor'') is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the M.D. denotes a professional degree. T ...

(March 2, 1909 – January 22, 1994) was an American virologist

Virology is the scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host cells for reproduction, their ...

and science administrator who was among the first to study the molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physi ...

and genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

of animal virus

Animal viruses are viruses that infect animals. Viruses infect all cellular life and although viruses infect every animal, plant, fungus and protist species, each has its own specific range of viruses that often infect only that species.

Vertebra ...

es, especially influenza virus

''Orthomyxoviridae'' (from Greek ὀρθός, ''orthós'' 'straight' + μύξα, ''mýxa'' 'mucus') is a family of negative-sense RNA viruses. It includes seven genera: ''Alphainfluenzavirus'', ''Betainfluenzavirus'', '' Gammainfluenzavirus'', ...

. He directed the Public Health Research Institute

The Public Health Research Institute (PHRI) was founded in 1942 by New York City's mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, who appointed

David M. Heyman to lead it as an independent not-for-profit research organization. In the late 1980s it was referred to ...

in New York City (1956–1981), and was also the founding editor-in-chief of ''Virology

Virology is the Scientific method, scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host (biology), ...

'', the first English-language journal to focus on virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es. He is particularly known for inventing the hemagglutination assay

The hemagglutination assay or haemagglutination assay (HA) and the hemagglutination inhibition assay (HI or HAI) were developed in 1941–42 by American virologist George Hirst as methods for quantifying the relative concentration of viruses, bact ...

, a simple method for quantifying viruses, and adapting it into the hemagglutination inhibition assay, which measures virus-specific antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

in serum. He was the first to discover that virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es can contain enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s, and the first to propose that virus genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

s can consist of discontinuous segments. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' described him as "a pioneer in molecular virology."

Education and career

Hirst was born in Eau Claire,Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, USA, but his family soon moved to Lewistown, Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

. He studied at Hobart College in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, New York, and later at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

, New Haven

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

, Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

, from which he gained his first degree and medical degree (1933). He worked at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research

The Rockefeller University is a private biomedical research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and provides doctoral and postdoctoral education. It is classif ...

in New York City in 1936–1940, under the supervision of Homer Swift and Rebecca Lancefield

Rebecca Craighill Lancefield (January 5, 1895 – March 3, 1981). p.227 was a prominent American microbiologist. She joined the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (now Rockefeller University) in New York in 1918, and was associated with ...

, and then moved to the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Carneg ...

's International Health Division

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Car ...

laboratories in 1940. There he combined research in collaboration with Frank Horsfall

Frank Lappin Horsfall, Jr. (Seattle, December 14, 1906 – New York City, February 19, 1971) was an American microbiologist specializing in pathology. He worked at the Rockefeller Institute, New York, from 1934 to 1960 and in the early 1950s ran ...

, Edwin D. Kilbourne and others with his army service, as a member of the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board's Commission on Influenza.US Army Medical Department: Office of Medical History: Commission on Influenza(accessed February 21, 2013) After the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Hirst joined the Public Health Research Institute

The Public Health Research Institute (PHRI) was founded in 1942 by New York City's mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, who appointed

David M. Heyman to lead it as an independent not-for-profit research organization. In the late 1980s it was referred to ...

in New York City, which had been established in 1942, where he remained until his retirement in 1983. He became head of the Infectious Diseases and Virology Divisions, and in 1956 succeeded L. Whittington Gorham as director of the institute, a position he held for nearly 25 years until 1981. During his tenure, he superintended its expansion and move to a new location on 26th Street and First Avenue.George Keble Hirst, 84, is dead; a pioneer in molecular virology. ''New York Times'' (26 January 1994)(accessed February 18, 2013) He also held a teaching position at the

New York University School of Medicine

NYU Grossman School of Medicine is a medical school of New York University, a private research university in New York City. It was founded in 1841 and is one of two medical schools of the university, with the other being the Long Island School of ...

.American Academy of Arts and Sciences: Academy Members: 1780–present: H(accessed January 18, 2013)

Research

Hirst's earliest research, in the 1930s, was on

Hirst's earliest research, in the 1930s, was on bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

, including pneumococci

''Streptococcus pneumoniae'', or pneumococcus, is a Gram-positive, spherical bacteria, alpha-hemolytic (under aerobic conditions) or beta-hemolytic (under anaerobic conditions), aerotolerant anaerobic member of the genus Streptococcus. They are ...

and streptococci

''Streptococcus'' is a genus of gram-positive ' (plural ) or spherical bacteria that belongs to the family Streptococcaceae, within the order Lactobacillales (lactic acid bacteria), in the phylum Bacillota. Cell division in streptococci occurs ...

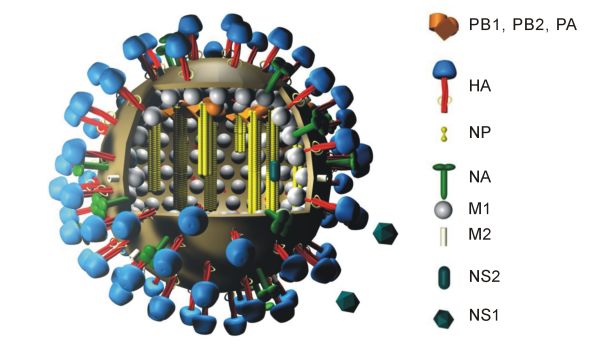

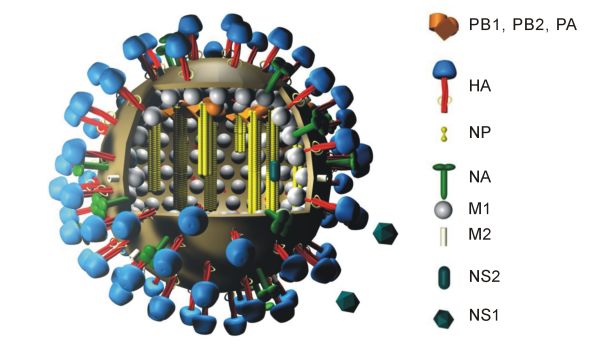

, in collaboration with Lancefield and others. In 1940, at the Rockefeller Foundation, he started to work on influenza virus

''Orthomyxoviridae'' (from Greek ὀρθός, ''orthós'' 'straight' + μύξα, ''mýxa'' 'mucus') is a family of negative-sense RNA viruses. It includes seven genera: ''Alphainfluenzavirus'', ''Betainfluenzavirus'', '' Gammainfluenzavirus'', ...

es – enveloped RNA virus

An RNA virus is a virusother than a retrovirusthat has ribonucleic acid (RNA) as its genetic material. The nucleic acid is usually single-stranded RNA ( ssRNA) but it may be double-stranded (dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA viruses ...

es infecting humans, birds and other vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

sHayden & Palese, pp. 891–892 – which were the focus of much of his subsequent research. Human influenza virus had first been isolated just a few years earlier. Later, Hirst also studied other vertebrate RNA viruses, including poliovirus

A poliovirus, the causative agent of polio (also known as poliomyelitis), is a serotype of the species ''Enterovirus C'', in the family of ''Picornaviridae''. There are three poliovirus serotypes: types 1, 2, and 3.

Poliovirus is composed of an ...

, mumps

MUMPS ("Massachusetts General Hospital Utility Multi-Programming System"), or M, is an imperative, high-level programming language with an integrated transaction processing key–value database. It was originally developed at Massachusetts Gener ...

and Newcastle disease virus Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

. Although viruses had been shown to infect animals in 1898, research on animal virus

Animal viruses are viruses that infect animals. Viruses infect all cellular life and although viruses infect every animal, plant, fungus and protist species, each has its own specific range of viruses that often infect only that species.

Vertebra ...

es was much less advanced in the 1940s and 1950s than that on plant virus

Plant viruses are viruses that affect plants. Like all other viruses, plant viruses are obligate intracellular parasites that do not have the molecular machinery to replicate without a host. Plant viruses can be pathogenic to higher plants.

M ...

es and bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

s, which were easier to handle experimentally.

Hemagglutination

In 1941, Hirst discovered that adding influenza virus particles tored blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

s caused them to agglutinate or stick together forming a lattice, a phenomenon called hemagglutination

Hemagglutination, or haemagglutination, is a specific form of agglutination that involves red blood cells (RBCs). It has two common uses in the laboratory: blood typing and the quantification of virus dilutions in a haemagglutination assay.

Blood ...

. Hemagglutination provided a convenient method of diagnosing influenza in the laboratory, which had previously been performed by cultivating the virus in ferrets. Hirst developed this reaction into the hemagglutination assay

The hemagglutination assay or haemagglutination assay (HA) and the hemagglutination inhibition assay (HI or HAI) were developed in 1941–42 by American virologist George Hirst as methods for quantifying the relative concentration of viruses, bact ...

, which allows the amount of virus in the sample to be measured. This technique is rapid, accurate and convenient, and later proved to be applicable to many other viruses. Joklik WK. (1999) When two is better than one: Thoughts on three decades of interaction between ''Virology'' and the ''Journal of Virology''. '' J Virol'' 73: 3520–3523text

Wolfgang Joklik cites the discovery of hemagglutination as one of the "early epoch-making discoveries in virology," stating that it made influenza virus "the first mammalian virus whose replication could be studied biochemically." Although Hirst did not know this at the time, hemagglutination is caused by the influenza virus

hemagglutinin

In molecular biology, hemagglutinins (or ''haemagglutinin'' in British English) (from the Greek , 'blood' + Latin , 'glue') are receptor-binding membrane fusion glycoproteins produced by viruses in the ''Paramyxoviridae'' family. Hemagglutinins ar ...

(a glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glycos ...

on the viral envelope

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes.

Numerous human pathogenic viruses in circulation are encase ...

) binding to sialic acid Sialic acids are a class of alpha-keto acid sugars with a nine-carbon backbone.

The term "sialic acid" (from the Greek for saliva, - ''síalon'') was first introduced by Swedish biochemist Gunnar Blix in 1952. The most common member of this gr ...

on the surface of the red blood cell; the same mechanism is central to the influenza virus entering its host cell. Racaniello VInfluenza hemagglutination inhibition assay (27 May 2009)

(accessed February 19, 2013)

Hemagglutination inhibition and vaccination

He soon realised that the hemagglutination assay could easily be adapted to measure the levels of

He soon realised that the hemagglutination assay could easily be adapted to measure the levels of antibody

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

specific to the virus strain in human serum: any antibodies present bind to the influenza virus particles, prevent them from crosslinking red blood cells and so inhibit hemagglutination. This hemagglutination inhibition assay (HIA) can be applied to many other viruses carrying a hemagglutinin

In molecular biology, hemagglutinins (or ''haemagglutinin'' in British English) (from the Greek , 'blood' + Latin , 'glue') are receptor-binding membrane fusion glycoproteins produced by viruses in the ''Paramyxoviridae'' family. Hemagglutinins ar ...

molecule, including rubella

Rubella, also known as German measles or three-day measles, is an infection caused by the rubella virus. This disease is often mild, with half of people not realizing that they are infected. A rash may start around two weeks after exposure and ...

, measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

, mumps, parainfluenza

Human parainfluenza viruses (HPIVs) are the viruses that cause human parainfluenza. HPIVs are a paraphyletic group of four distinct single-stranded RNA viruses belonging to the ''Paramyxoviridae'' family. These viruses are closely associated with ...

, adenoviruses

Adenoviruses (members of the family ''Adenoviridae'') are medium-sized (90–100 nm), nonenveloped (without an outer lipid bilayer) viruses with an icosahedral nucleocapsid containing a double-stranded DNA genome. Their name derives from thei ...

, polyomaviruses and arbovirus

Arbovirus is an informal name for any virus that is transmitted by arthropod vectors. The term ''arbovirus'' is a portmanteau word (''ar''thropod-''bo''rne ''virus''). ''Tibovirus'' (''ti''ck-''bo''rne ''virus'') is sometimes used to more spe ...

es, and is still widely used in influenza surveillance

Surveillance is the monitoring of behavior, many activities, or information for the purpose of information gathering, influencing, managing or directing. This can include observation from a distance by means of electronic equipment, such as c ...

and vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

testing. Hannah Hoag, writing in ''Nature Medicine

''Nature Medicine'' is a monthly Peer review, peer-reviewed medical journal published by Nature Portfolio covering all aspects of medicine. It was established in 1995. The journal seeks to publish research papers that "demonstrate novel insight int ...

'' in 2013, describes the assay as "the gold-standard serologic test to type influenza antibodies in humans and animals."Hoag H. (2013) A universal problem. ''Nature Medicine

''Nature Medicine'' is a monthly Peer review, peer-reviewed medical journal published by Nature Portfolio covering all aspects of medicine. It was established in 1995. The journal seeks to publish research papers that "demonstrate novel insight int ...

'' 19: 12–14text

HIA is "a powerful epidemiological tool," according to virologist

Vincent Racaniello

Vincent R. Racaniello (born January 2, 1953) is a Higgins Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons. He is a co-author of a textbook on virology, ''Principles of Virolo ...

, and Hirst explored its application to epidemiological

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population.

It is a cornerstone of public health, and shapes policy decisions and evidenc ...

studies. He was one of several researchers who developed and trialed inactivated influenza vaccines in the mid-1940s, and he applied HIA to the study of antibody responses to vaccination.

Neuraminidase and the virus receptor

Hirst noticed that hemagglutination tended to wear off over time, and in 1942, he discovered that influenza virus has an intrinsic

Hirst noticed that hemagglutination tended to wear off over time, and in 1942, he discovered that influenza virus has an intrinsic enzymatic

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

activity that can release the virus from its attachment to red blood cells. This was a ground-breaking discovery, as previously a key distinction between viruses and bacteria had been that viruses were believed to lack enzymes. Hirst demonstrated that red blood cells once de-agglutinated could not be re-agglutinated, and correctly deduced that the enzyme destroys a receptor for the virus on the red blood cells. This enzyme, then referred to as the "receptor-destroying enzyme" was later shown to be the influenza neuraminidase

Exo-α-sialidase (EC 3.2.1.18, sialidase, neuraminidase; systematic name acetylneuraminyl hydrolase) is a glycoside hydrolase that cleaves the glycosidic linkages of neuraminic acids:

: Hydrolysis of α-(2→3)-, α-(2→6)-, α-(2→8)- glycos ...

, another viral envelope glycoprotein, which acts as a sialidase

Exo-α-sialidase (EC 3.2.1.18, sialidase, neuraminidase; systematic name acetylneuraminyl hydrolase) is a glycoside hydrolase that cleaves the glycosidic linkages of neuraminic acids:

: Hydrolysis of α-(2→3)-, α-(2→6)-, α-(2→8)- glycos ...

.Colman PM. (1994) Influenza virus neuraminidase: Structure, antibodies, and inhibitors. ''Protein Science

''Protein Science'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal covering research on the structure, function, and biochemical significance of proteins, their role in molecular and cell biology, genetics, and evolution, and their regulation and mechan ...

'' 3: 1687–1696Laver G. "Influenza virus surface glycoproteins, haemagglutinin and neuraminidase: a personal account" in ''Influenza'' (CW Potter, ed.), p. 31 (''Perspectives in Medical Virology'' series) (Elsevier; 2002) () Like hemagglutinin, neuraminidase is essential for the influenza life cycle, being required for the progeny virus to leave the host cell. Neuraminidase is the target of the

neuraminidase inhibitor Neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) are a class of drugs which block the neuraminidase enzyme. They are a commonly used antiviral drug type against influenza. Viral neuraminidases are essential for influenza reproduction, facilitating viral budding from ...

class of antiviral drugs, which include oseltamivir

Oseltamivir, sold under the brand name Tamiflu, is an antiviral medication used to treat and prevent influenza A and influenza B, viruses that cause the flu. Many medical organizations recommend it in people who have complications or are at hig ...

(Tamiflu) and zanamivir

Zanamivir is a medication used to treat and prevent influenza caused by influenza A and influenza B viruses. It is a neuraminidase inhibitor and was developed by the Australian biotech firm Biota Holdings. It was licensed to Glaxo in 1990 and ap ...

(Relenza).

Hirst subsequently found that influenza virus interacts with a similar receptor on its target cell during infection, providing a model for the initiation of viral infection that turned out to apply to all viruses. He continued to investigate the nature of this cellular receptor during the 1940s and 1950s, correctly proposing in 1948 that the receptor might be one or more mucoprotein A mucoprotein is a glycoprotein composed primarily of mucopolysaccharides. Mucoproteins can be found throughout the body, including the gastrointestinal tract, reproductive organs, airways, and the synovial fluid of the knees. They are called mucopr ...

s.Nicholls JM, Lai J, Garcia JM. "Investigating the interaction between influenza and sialic acid: Making and breaking the link" in ''Influenza Virus Sialidase – A Drug Discovery Target'' (M von Itzstein, ed.) (''Milestones in Drug Therapy'' series), p. 32 (Springer; 2012) ()

Segmented influenza genome

Starting in the late 1940s, Hirst carried out pioneering research into the genetics of animal viruses. His team built onFrank Macfarlane Burnet

Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, (3 September 1899 – 31 August 1985), usually known as Macfarlane or Mac Burnet, was an Australian virologist known for his contributions to immunology. He won a Nobel Prize in 1960 for predicting acquired immune ...

's work on recombination in influenza virus, carrying out a series of experiments that led Hirst to conclude in 1962 that influenza's genome must consist of several separate fragments, "a truly revolutionary idea at the time," according to R. Walter Schlesinger and Allan Granoff. Influenza viruses are now known to have eight such segments, and the segmentation of its genome facilitates the exchange of segments between different influenza viruses, causing antigenic shift

Antigenic shift is the process by which two or more different strains of a virus, or strains of two or more different viruses, combine to form a new subtype having a mixture of the surface antigens of the two or more original strains. The term is ...

which can result in pandemics

A pandemic () is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. A widespread endemic disease with a stable number of in ...

. Segmented genomes are also found in many other viruses.

''Virology'' journal

Hirst founded the journal ''Virology

Virology is the Scientific method, scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host (biology), ...

'' in 1955, together with bacteriophage specialist Salvador Luria

Salvador Edward Luria (August 13, 1912 – February 6, 1991) was an Italian microbiologist, later a naturalized U.S. citizen. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1969, with Max Delbrück and Alfred Hershey, for their discoveries ...

and plant virologist Lindsay Black. It was the first journal in the English language to specialise in publishing research into viruses, and it united basic science research across viruses infecting all types of host, a lifelong objective of Hirst's. The founding editor-in-chief, he headed up the journal for 21 years, until 1975. On his retirement, he was praised by his co-editors:

Awards and honors

Hirst gave the 1948 Harvey Lecture of theNew York Academy of Medicine

The New York Academy of Medicine (the Academy) is a health policy and advocacy organization founded in 1847 by a group of leading New York metropolitan area physicians as a voice for the medical profession in medical practice and public health ...

on the topic of "The nature of hemagglutination by viruses" and, in 1961, the inaugural Pfizer

Pfizer Inc. ( ) is an American multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology corporation headquartered on 42nd Street in Manhattan, New York City. The company was established in 1849 in New York by two German entrepreneurs, Charles Pfizer ...

Lecture in Virology at the Institute of Virology in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, UK, on "Development of virology as an independent science".Hirst GK. (1962) Development of virology as an independent science. ''British Medical Journal

''The BMJ'' is a weekly peer-reviewed medical trade journal, published by the trade union the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world's oldest general medical journals. Origi ...

'' 26 May: 1431–1437In 1966, he was elected to membership of the

National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

and in 1975, to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

. He was awarded the Academy Medal of the New York Academy of Medicine

The New York Academy of Medicine (the Academy) is a health policy and advocacy organization founded in 1847 by a group of leading New York metropolitan area physicians as a voice for the medical profession in medical practice and public health ...

"for distinguished contributions in biomedical science" in 1975.(accessed February 21, 2013)

Character and personal life

His colleague Edwin Kilbourne described Hirst as "a scientist's scientist—a virologist's virologist" with an "incredible" variety of expertise and an "insatiable curiosity," who pursued the underlying explanation for his experimental findings with tenacity.Kilbourne ED. (1975) Presentation of the Academy Medal to George K. Hirst, M.D. ''Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine

The ''Journal of Urban Health'' is a bimonthly peer-reviewed public health journal covering epidemiology and public health in urban areas. It was established in 1851 as the ''Transactions of the New York Academy of Medicine'', and was renamed the ' ...

'' 51: 1133–1136According to Kilbourne, he was very private person who did not seek publicity. His non-scientific pursuits included music – he was both a musician and a musicologist – gardening, and the appreciation of nature. Hirst married Charlotte Hart in 1937, and the couple had four sons and a daughter. In retirement he moved to

Palo Alto

Palo Alto (; Spanish for "tall stick") is a charter city in the northwestern corner of Santa Clara County, California, United States, in the San Francisco Bay Area, named after a coastal redwood tree known as El Palo Alto.

The city was estab ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

. His wife predeceased him in 1990.

Key papers

* * * * * * *References

Sources

*DeFranco A, Locksley R, Robertson M. ''Immunity: The Immune Response in Infectious and Inflammatory Disease'' (New Science Press; 2007) () * Hayden FG, Palese P. "Influenza virus" in ''Clinical Virology'' (2nd edn) ( Richman DD, Whitley RJ, Hayden FG, eds) (ASM Press; 2002) () * Oldstone MBA. ''Viruses, Plagues, and History: Past, Present and Future'' (Oxford University Press; 2009) () * Specter S, Hodinka RL, Wiedbrauk DL, Young SA. "Diagnosis of viral infections" in ''Clinical Virology'' (2nd edn) 'Op. cit.'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Hirst, George 1909 births 1994 deaths Influenza researchers American virologists People from Lewistown, Montana Scientists from New York City People from Eau Claire, Wisconsin Yale School of Medicine alumni Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 20th-century American physicians Hobart and William Smith Colleges alumni